Abstract

With the widespread adoption of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles, energy storage, and consumer electronics, accurate capacity estimation has become critical for battery management systems (BMS). To address the limitations of existing methods—which emphasize time-domain features, and struggle to capture periodic degradation and high-frequency disturbances in the frequency domain, and whose deep networks often under-represent long-term degradation trends due to gradient issues—this paper proposes a frequency-domain enhanced Transformer for lithium-ion battery capacity estimation. Specifically, for each cycle we apply FFT to voltage, current, and temperature signals to extract frequency-domain features and fuse them with time-domain statistics; a residual connection is introduced within the Transformer encoder to stabilize optimization and preserve long-term degradation trends, enabling high-precision capacity estimation. Evaluated on three batches of the MIT public fast-charging dataset, the method achieves Avg RMSE 0.0013, Avg MAE 0.0006, and Avg R2 0.9977 on the test set; compared with the Transformer baseline, RMSE decreases by 60.6%, MAE decreases by 73.9%, and R2 increases by 0.83%. The contribution lies in jointly embedding explicit time-frequency feature fusion and residual connections into a Transformer backbone to obtain accurate estimates with stable generalization. In terms of societal benefit, more reliable capacity/health estimates can support better BMS decision-making, improve the safety and lifetime of electric vehicles and energy-storage systems, and reduce lifecycle costs.

1. Introduction

With the widespread adoption of electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and portable electronic devices, lithium-ion batteries have become the core energy storage component, whose performance and lifespan directly affect system safety and cost-efficiency [1,2,3]. Battery capacity, as a key indicator for assessing the state of health (SOH), plays a critical role in enabling efficient battery management, prolonging service life, and preventing potential failures [4,5]. Therefore, developing high-precision and robust capacity estimation methods has become a central focus of battery management system (BMS) research [6,7].

Currently, battery capacity estimation methods can be broadly categorized into model-based approaches and data-driven approaches. The former typically rely on equivalent circuit models (ECM) or electrochemical models, combined with filtering algorithms such as the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), or Unscented Particle Filter (UPF), to perform capacity estimation [8,9]. For instance, Xie et al. [10] proposed an EKF-based algorithm utilizing a second-order RC ECM for state of charge (SOC) estimation in lithium-ion batteries, demonstrating its effectiveness under complex operating conditions. Additionally, Ma et al. [11] proposed an adaptive EKF method that integrates VFFRLS parameter identification and innovation-based covariance correction, achieving SOC estimation errors as low as 0.15% under high noise and uncertainty. Guo et al. [12] developed an improved Thevenin model coupled with a UKF algorithm for SOC estimation, which improved the characterization of system nonlinear dynamics and exhibited higher estimation accuracy and stability. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [13] proposed a UPF-based RUL prediction framework for multisensor systems. Though not battery-specific, their method effectively handles nonlinear dynamics and uncertainty, offering insights for SOC estimation under complex conditions. However, such approaches demand the precise identification of internal battery parameters during modeling, requiring stringent model fidelity and parameter stability—making them less adaptable to the complex and variable operating conditions of real-world battery applications.

In contrast, data-driven methods—especially deep learning models such as neural networks—can automatically learn degradation patterns from large volumes of historical data. These methods offer strong nonlinear modeling capabilities and adaptability, and have shown promising potential for battery capacity estimation [14,15]. For example, Tian et al. [16] proposed a capacity estimation approach based on multiple small voltage segments and backpropagation neural networks (BP-NN). By extracting health indicators from voltage curves and integrating multiple neural models, the method achieved high estimation accuracy even under incomplete charge cycles. Moreover, Wang et al. [17] developed a physics-informed neural network (PINN) model for capacity estimation by incorporating physical degradation mechanisms, which significantly enhanced generalization performance and cross-battery adaptability, yielding excellent results across various battery types and charge/discharge conditions. Additionally, Lyu et al. [18] proposed an early-cycle RUL prediction method using Lebesgue-sampling and parallel-state-fusion LSTM, achieving ~3.6% and 6.7% average errors on the MIT and Tongji datasets, respectively. Beyond the battery domain, deep learning methods have also seen widespread use in other industrial sectors, such as medical equipment, aircraft systems, and flight control applications, demonstrating their versatility in modeling complex dynamics and enabling predictive maintenance across domains [19,20,21].

Entering 2025, a series of cutting-edge studies on battery capacity estimation have emerged. Wu et al. [22] proposed a framework that integrates deep learning-based estimation with clustering analysis, which not only improves the accuracy of state estimation but also enables the automatic grouping of batteries according to their electrochemical characteristics, thereby supporting differentiated management strategies. Zhou et al. [23] constructed a deep learning model for SOH estimation based on the multi-level fusion features of discharge curves, which more precisely captures nonlinear degradation trajectories and significantly enhances estimation accuracy. To address the strong heterogeneity and limited data of retired batteries, Tao et al. [24] introduced a deep generative transfer learning framework, achieving immediate remaining capacity estimation of heterogeneous second-life batteries with only a small portion of field data and substantially reducing prediction errors. Zhao et al. [25] combined interpretable deep learning with parameter optimization, improving the RUL prediction of lithium-ion batteries while enhancing the interpretability of model decisions. Zhang et al. [26] proposed an adaptable capacity estimation method based on a constructed open-circuit voltage (OCV) curve, which maintains high robustness and adaptability even in engineering scenarios lacking complete test data. Rout et al. [27] demonstrated that advanced data-driven techniques can reduce SOH estimation errors to the order of 10−4 with R2 exceeding 0.998, further confirming the outstanding capabilities of deep learning in capacity prediction. Overall, these latest studies not only expand the applicability of capacity estimation under partial data, complex operating conditions, and diverse battery scenarios, but also provide strong comparisons and complementary insights for the time-frequency fusion and residual-structure-based approach proposed in this paper.

Despite the progress of data-driven approaches, several challenges remain. Most notably, existing models typically rely solely on a time-domain modeling of battery data, overlooking the potential value of frequency-domain information, which impairs their ability to capture periodic variations and high-frequency disturbances in degradation processes. Furthermore, deep neural networks are prone to gradient vanishing or exploding issues during training, hindering the learning of long-term dependencies and ultimately compromising the accuracy and stability of capacity estimation [1,28].

To address these issues, this paper proposes a frequency-domain enhanced Transformer model for battery capacity estimation. The method first applies Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to extract frequency-domain features from the raw feature sequences and fuses them with time-domain features, thereby improving the model’s ability to perceive periodic and high-frequency components. Furthermore, an external residual structure is introduced to nonlinearly integrate the encoder’s input and output, preserving original trend information and enhancing nonlinear fitting capacity, and thus effectively mitigating gradient degradation issues in deep networks. With these improvements, the proposed model achieves high estimation accuracy and stability with relatively low computational complexity, offering reliable decision support for battery health management systems.

2. Methodology

To accurately model and predict the degradation trajectory of battery capacity, this paper proposes a frequency domain-enhanced Transformer-based capacity estimation method. The overall methodological flow is illustrated in Figure 1. This approach leverages statistical features extracted from charge-discharge cycles, augmented by frequency-domain analysis to strengthen the model’s ability to recognize periodic degradation patterns. It constructs a hybrid time-frequency feature representation and employs a modified Transformer encoder to model the battery’s health evolution across its full life cycle.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proposed method.

Specifically, the method begins by extracting a range of statistical features—such as maximum, minimum, mean, and standard deviation—from the raw cycle data to reduce dimensionality while preserving key aging characteristics. Then, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is applied to extract both real and imaginary frequency-domain components, which are fused with the time-domain features to achieve unified multiscale degradation modeling. Finally, a Transformer encoder integrating multi-head attention and feed-forward networks is constructed, with an external residual structure introduced to improve training stability and nonlinear approximation capacity. Compared with traditional sequence modeling methods, the proposed approach not only incorporates frequency-domain priors at the input level but also features a Transformer-based deep encoding strategy tailored to battery degradation forecasting—providing strong modeling power and engineering scalability.

The following subsections provide a detailed explanation of each key component of the proposed framework.

2.1. Data Preprocessing

The raw charge-discharge data typically exhibit high dimensionality and considerable noise, which, if directly modeled, would increase computational complexity and compromise robustness. Thus, the data preprocessing module extracts key statistical features from each cycle to compress information and reduce dimensionality.

Let the raw measured sequence of the -th charge-discharge cycle be denoted as , where represents the number of time sampling points in the cycle. To effectively characterize the cycle, the following statistical features are extracted: maximum, minimum, mean, median, and standard deviation. The specific formulas are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Feature calculation formulas.

For example, given a voltage curve from a single cycle, one can compute the above features as follows: . Similarly, the same can be performed for current and temperature signals. All such features are then concatenated to form the feature vector for the -th cycle:

where denotes the total number of extracted features.

Each original high-dimensional cycle curve is thus compressed into a low-dimensional vector that preserves critical state information. These features capture extrema and average behaviors during the cycle, making them effective descriptors of aging (e.g., decreasing capacity, increasing internal resistance).

After computing feature vectors for each cycle, normalization (standardization) is performed. For each feature dimension , its mean and standard deviation are computed from the training set and used to scale the data:

This brings features of varying units into a comparable numerical range, enhancing training stability and convergence.

Compared to directly using raw time-series data, this statistical feature-based preprocessing significantly reduces dimensionality and noise interference while maintaining representational power—facilitating the more efficient learning of degradation patterns. The resulting feature sequences serve as input for the subsequent prediction model.

2.2. Frequency-Domain Enhanced Feature Fusion Mechanism

During the gradual degradation of battery performance across charge-discharge cycles, periodic oscillations or complex noise patterns may be superimposed. Relying solely on time-domain features is insufficient to fully capture such information. Therefore, this paper introduces a frequency-domain enhanced feature-fusion mechanism based on the feature sequence: frequency-domain information is extracted via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and fused with the original time-domain features to improve the model’s ability to identify periodic degradation modes.

To be specific, consider a temporal feature vector sequence ; we extend its dimensionality to form a 2D tensor , enabling the concatenation of frequency-domain features along the channel dimension. Applying FFT along the C-dimension yields a complex spectrum representation , where

The complex representation is decomposed into real and imaginary parts, i.e., . The low-frequency components in the frequency domain characterize the long-term trends of the original features (e.g., gradual capacity decline), while high-frequency components correspond to short-term periodic fluctuations or measurement noise.

The original time-domain feature is concatenated with the real part vector and imaginary part vector , forming the following enhanced feature representation:

where denotes the concatenation operation.

Subsequently, a fully connected layer (with weight ) is used to perform a linear projection:

where is the activation function and is the bias term. The resulting is used as input to the subsequent Transformer encoder.

This mechanism significantly enhances the model’s capacity to capture periodic changes, compensating for the inability of purely time-domain inputs to express complex frequency information, and thus improving model sensitivity to both nonlinear degradation trends and periodic perturbations.

2.3. Transformer Encoder with Residual Connection

This paper adopts a Transformer-based sequence modeling approach to extract global dependency relationships within the feature sequence. The Transformer encoder is composed of multiple stacked layers, each consisting of a Multi-Head Self-Attention mechanism and a Feed-Forward Network, with residual connections and layer normalization strategies employed [29].

For the input sequence , attention is calculated in each layer as follows:

where represent the query, key, and value obtained by the linear transformation of the input, and is the scaling factor.

Multiple attention heads are computed in parallel and concatenated for linear projection, producing output , followed by residual connection and normalization:

Dropout is a regularization strategy that randomly deactivates neurons during training to improve generalization. LayerNorm normalizes across the feature dimension for each sample to maintain distribution stability and accelerate model convergence.

Then, the output enters the feed-forward network:

where are fully connected layer weights, are biases, and is the activation function, e.g., ReLU or GELU.

Another residual connection is applied:

To further improve representational power and training stability, this paper introduces an external residual connection. The output of the Transformer encoder is nonlinearly fused with the initial input as follows:

This external structure not only retains the original trend information but also enhances nonlinear fitting capability, effectively mitigating gradient vanishing issues in deep networks.

Finally, the model output passes through a fully connected layer to yield the predicted capacity:

where , denote the output layer’s weight and bias.

The model output is used for capacity estimation and compared with failure thresholds (e.g., 80% of the initial capacity) to support health status classification and maintenance decision-making, thereby forming a complete prediction loop. In summary, the proposed frequency-enhanced Transformer method achieves end-to-end modeling from input data to capacity state.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Description and Experimental Setup

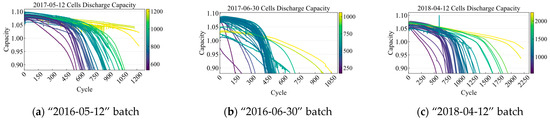

We used the public MIT fast-charging battery degradation dataset. The cells are commercial A123 APR18650M1A (LFP/graphite, 18650 form factor) with a nominal capacity of 1.1 Ah and nominal voltage of 3.3 V. Cycling was performed on a 48-channel Arbin LBT potentiostat inside a forced-convection chamber at 30 °C. Each cycle provides time-series signals of voltage, current, and temperature. We included three batches—12 May 2017 (~46 cells), 30 June 2017 (~48 cells), and 12 April 2018 (~46 cells)—for a total of ~140 cells used for training, validation, and testing.

Cells were charged under one- or two-step constant-current fast-charging policies and then discharged; the second charging step terminated at ~80% SOC, and constant-voltage cutoffs (when applicable) were C/50. Internal resistance was measured near 80% SOC using ±3.6 C current pulses of 30 ms (33 ms for the 12 April 2018 batch). Surface temperature was monitored with a Type-T thermocouple affixed by epoxy and Kapton tape. Known data notes (e.g., occasional computer restarts, thermocouple swaps, a few noisy or early-terminated channels) were corrected in the released MATLAB (R2024b) structs. The corresponding capacity trajectories are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Discharge capacity curves of the battery dataset.

To ensure the generalizability and objectivity of model evaluation, the dataset was split as follows: 30% of the battery samples (42 cells) were randomly selected as the test set to evaluate prediction performance on unseen data; 30% (30 cells) of the remaining samples served as a validation set for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping; the remaining 68 cells constituted the training set for parameter learning.

The model was implemented using the PyTorch (v2.4.0) deep learning framework. During training, the batch size was set to 64, and the Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) optimizer was used. The loss function was the Mean Squared Error (MSE), which is appropriate for regression tasks. The learning rate was set to 0.001. In addition, we applied early stopping based on the validation loss with a patience of 10 epochs: if no improvement was observed for 10 consecutive epochs, training stopped and the best-performing checkpoint (lowest validation loss) was restored for testing and reporting.

3.2. Evaluation Metric

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance in battery capacity prediction, the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) was adopted as the primary evaluation metric. RMSE is a widely used metric in regression analysis, effectively reflecting the deviation between predicted and true values.

To comprehensively assess battery-capacity prediction, we report three standard regression metrics: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (R2). For a test set of samples with predictions and ground-truth values ,

A lower RMSE/MAE indicates better accuracy (MAE is less sensitive to outliers), while larger R2 indicates a better fit (R2 = 1 is perfect).

3.3. Comparative Study: Results and Analysis

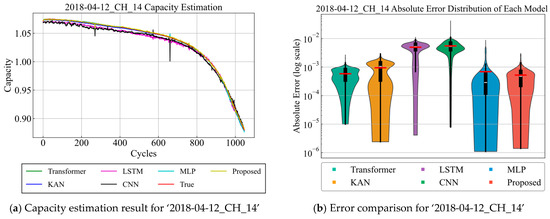

To validate the proposed model’s effectiveness in battery capacity prediction, several representative deep learning models were selected for comparison, including Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) [30], Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [31], Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [32], Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) [33], and the standard Transformer model [34]. The prediction results for several representative test batteries are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Visualization comparison of battery capacity estimation results. Each violin depicts the full absolute error distribution; the inner box marks the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles), the white horizontal line indicates the median, and the red bar denotes the mean. The y-axis uses a base-10 logarithmic scale to accommodate a wide dynamic range and avoid the plot being dominated by a few extreme outliers. At this scale, lower positions correspond to smaller errors (better accuracy), and narrower violins indicate lower variability (greater stability).

From the visualizations in Figure 3, the capacity curves (left panels) indicate that the proposed model achieves the closest overlap with the ground-truth trajectories across multiple representative cells, with only minimal deviations observed at the early stage and around the knee region. In contrast, MLP and CNN show larger deviations before and after the knee, while LSTM and KAN tend to exhibit local oscillations or drift over time. More importantly, the log-scale violin plots (right panels) provide consistent evidence at the error-distribution level: in most cases, the proposed model demonstrates lower white median lines and lower red mean bars, together with tighter black IQR boxes and shorter upper tails, indicating lower median/mean errors, smaller dispersion, and fewer high-error outliers. Transformer is also competitive, achieving comparable or slightly lower medians/means on a few cells, though its IQR is typically slightly wider. By contrast, MLP and CNN show higher medians/means with wider IQRs, while LSTM and KAN display longer upper tails, suggesting a greater tendency to generate high-error points.

Table 2 presents the test-set averages of the three metrics—RMSE, MAE, and R2—for all models (averaged over all test samples). The best result for each metric is highlighted in bold.

Table 2.

Metric averages on the test set in comparative experiments. Best values are bolded.

Table 2 reports the metric-wise test-set averages. The proposed method ranks first in all three metrics. Relative to the runner-up, it reduces RMSE from 0.0030 to 0.0013 (−56.7%), reduces MAE from 0.0015 to 0.0006 (−60.0%), and increases R2 from 0.9909 to 0.9977 (absolute +0.0068), equivalent to a 74.7% reduction in unexplained variance (1−R2).

These advantages are not coincidental but directly stem from the model design. On the one hand, the FFT-driven time-frequency features combined with time-domain statistics enhance sensitivity to periodic and oscillatory degradation signatures while suppressing high-frequency noise, which manifests in the log-scale violin plots as an overall “downward and tighter” error distribution (lower median/mean, narrower IQR, and shorter tails). On the other hand, the external residual connection stabilizes deep optimization and preserves long-term degradation trends, thereby reducing systematic bias around the knee region. In contrast, MLP and CNN rely mainly on local time-domain patterns, limiting their ability to capture long-range dependencies and suppress noise, which results in wider IQRs; LSTM and KAN are more prone to oscillation or drift under long-sequence and noisy conditions, reflected by heavier upper tails. Overall, both the curve overlays (left) and the error-distribution shapes (right) consistently support the superiority of the proposed model; in individual cells, Transformer can serve as a close secondary baseline. This trend is further corroborated by the metric-wise comparisons in Table 2 and the ablation study in Section 3.4.

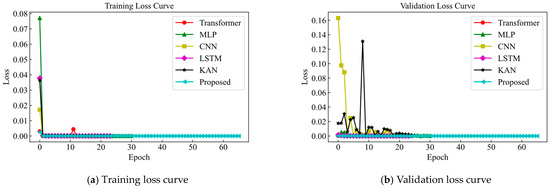

We additionally present, for each model, the training and validation loss curves recorded during training, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Training and validation curves.

From Figure 4, under the early-stopping criterion (validation loss; patience = 10), all models reach a stable minimum and halt before overfitting. The training and validation curves descend in tandem and then plateau without divergence, indicating no obvious underfitting either. Among them, proposed attains the lowest and most stable validation loss.

3.4. Ablation Study: Results and Analysis

An ablation study systematically removes or replaces specific components of a model to isolate and quantify their individual contributions under controlled conditions. Practically, we compare the full model against variants in which key modules are deactivated (e.g., without frequency-domain features’ structure, without the residual connection, or without both).

The four variants are defined as follows:

Model-1: with FFT-based spectral features and residual connection.

Model-2: without the frequency-domain features module; residual connection retained.

Model-3: without the residual connection; frequency-domain features module retained.

Model-4 (Baseline): without both frequency-domain features module and residual connection.

Ablation results are summarized in the Table 3; the best values are highlighted in bold.

Table 3.

Metric averages on the test set in ablation experiments. Best values are bolded.

The ablation shows that both components are useful and complementary. Removing the spectral (frequency-domain) features (model-2) harms performance more than removing the residual connection (model-3), indicating that the spectral module is the primary contributor. Enabling both (model-1) yields clear synergy: RMSE drops by ~28% vs. frequency-domain features module-only and by ~43% vs. residual-only, with R2 further improved. For context, relative to the Transformer, the full model cuts RMSE by 60.6% and increases R2 by 0.0082.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses two core challenges in battery capacity estimation. First, mainstream approaches predominantly rely on time-domain sequence modeling, neglecting the latent value of frequency-domain information, which limits their ability to effectively characterize periodic disturbances and multi-scale variations during degradation. Second, although deep neural networks possess strong nonlinear modeling capabilities, they often suffer from gradient vanishing when learning long-term dependencies and exhibit limited capacity to represent original degradation trends—ultimately impairing both stability and accuracy.

To overcome these limitations, we propose a frequency-domain enhanced Transformer model. At the input layer, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is applied to extract frequency-domain features, which are fused with statistical time-domain features to improve the model’s ability to recognize periodic characteristics and high-frequency disturbances. Additionally, a residual connection is designed to introduce cross-layer connections outside the core Transformer encoder. Through nonlinear mappings, this mechanism preserves trend information from the original input and enhances nonlinear representation capacity, thereby alleviating gradient degradation issues in deep architectures.

Experiments on the publicly available MIT battery dataset validate the effectiveness of the proposed method. Compared to representative neural network models—including MLP, CNN, LSTM, and KAN—as well as the baseline Transformer, the proposed model achieves superior predictive accuracy and stability across various test samples. Specifically, on the test set the proposed model attains Avg RMSE 0.0013 versus 0.0033 for Transformer, a 60.6% reduction. Its Avg MAE is 0.0006 versus 0.0023, a 73.9% reduction. The Avg R2 is 0.9977 versus 0.9895 for Transformer, a 0.83% relative increase. Moreover, visualized results confirm that the proposed approach demonstrates better fitting smoothness, greater accuracy in capturing capacity trends, and more consistent predictions during the degradation stage. These results highlight the complementary advantages of the frequency-domain enhancement mechanism and the residual connection in improving the performance of battery capacity estimation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X. and D.Y.; methodology, W.X.; software, W.X.; validation, W.X.; formal analysis, W.X.; investigation, W.X.; resources, W.X. and D.Y.; data curation, W.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, D.Y.; visualization, W.X.; supervision, D.Y.; project administration, D.Y.; funding acquisition, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was partially supported by the Key support projects of the Regional Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U24A203192).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are from a publicly available dataset.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Miao, Q. Adaptive Diagnosis and Prognosis for Lithium-Ion Batteries via Lebesgue Time Model with Multiple Hidden State Variables. Appl. Energy 2025, 392, 125986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Q. An Interpretable State of Health Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Multi-Category and Multi-Stage Features. Energy 2023, 283, 129067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Q. An Adaptive and Interpretable SOH Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based-on Relaxation Voltage Cross-Scale Features and Multi-LSTM-RFR2. Energy 2024, 304, 132167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mo, Z.; Wang, J.; Miao, Q. Nonlinear-Drifted Fractional Brownian Motion with Multiple Hidden State Variables for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2020, 69, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Q. RUL Prediction of Lithium-Ion Battery in Early-Cycle Stage Based on Similar Sample Fusion under Lebesgue Sampling Framework. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3511511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Gong, Y.; Shang, Y. Data-Driven Available Capacity Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Fragmented Charge Capacity. Commun. Eng. 2025, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Bhushan Gopaluni, R.; Cao, Y.; Heere, M.; Mühlbauer, M.J.; Mereacre, L.; Dai, H.; Liu, X.; et al. Data-Driven Capacity Estimation of Commercial Lithium-Ion Batteries from Voltage Relaxation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.; Blyth, M.; Hales, A. Advancing State Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries with Hysteresis through Systematic Extended Kalman Filter Tuning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Miao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. An Improved Unscented Particle Filter Approach for Lithium-Ion Battery Remaining Useful Life Prediction. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 81, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wei, X.; Bo, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, P.; Hao, W.; Yuan, M. State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Battery Based on Extended Kalman Filter Algorithm. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1180881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Gao, K.; Mu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Du, R. An Adaptive Tracking-Extended Kalman Filter for SOC Estimation of Batteries with Model Uncertainty and Sensor Error. Energies 2022, 15, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, S.; Zhu, R. An Unscented Kalman Filtering Method for Estimation of State-of-Charge of Lithium-Ion Battery. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 998002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, E.; Zhang, B.; Miao, Q. RUL Prediction and Uncertainty Management for Multisensor System Using an Integrated Data-Level Fusion and UPF Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 4692–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Han, T. Data-Driven Lithium-Ion Batteries Capacity Estimation Based on Deep Transfer Learning Using Partial Segment of Charging/Discharging Data. Energy 2023, 271, 127033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Niu, G.; Zhang, B.; Miao, Q. Cost-Effective Lebesgue Sampling Long Short-Term Memory Networks for Lithium-Ion Batteries Diagnosis and Prognosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 1958–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Dong, Q.; Tian, J.; Li, X. Capacity Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Multiple Small Voltage Sections and BP Neural Networks. Energies 2023, 16, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhai, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Di, Y.; Chen, X. Physics-Informed Neural Network for Lithium-Ion Battery Degradation Stable Modeling and Prognosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Q. Parallel State Fusion LSTM-Based Early-Cycle Stage Lithium-Ion Battery RUL Prediction under Lebesgue Sampling Framework. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 236, 109315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Miao, Q.; Huang, J. Prognosis for Filament Degradation of X-Ray Tubes Based on IoMT Time Series Data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 8084–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Q. A Novel Altitude Measurement Channel Reconstruction Method Based on Symbolic Regression and Information Fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3502212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Q. Enhancing Aircraft Reliability with Information Redundancy: A Sensor-Modal Fusion Approach Leveraging Deep Learning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 261, 111068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, D.; He, W.; Yang, D.; Wu, Z.; Geng, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Hu, L.; et al. Efficient Estimating and Clustering Lithium-Ion Batteries with a Deep-Learning Approach. Commun. Eng. 2025, 4, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rong, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Yi, F.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, C. Deep Learning Estimation of State of Health for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Multi-Level Fusion Features of Discharge Curves. J. Power Sources 2025, 653, 237781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Guo, R.; Lee, J.; Moura, S.; Casals, L.C.; Jiang, S.; Shi, J.; Harris, S.; Zhang, T.; Chung, C.Y.; et al. Immediate Remaining Capacity Estimation of Heterogeneous Second-Life Lithium-Ion Batteries via Deep Generative Transfer Learning. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 7413–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Lithium-Ion Battery Remaining Useful Life Prediction Based on Interpretable Deep Learning and Network Parameter Optimization. Appl. Energy 2025, 379, 124713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Su, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Fan, X. An Adaptable Capacity Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on a Constructed Open Circuit Voltage Curve. Batteries 2025, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.; Samal, S.K.; Gelmecha, D.J.; Mishra, S. Estimation of State of Health for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Advanced Data-Driven Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fallah, S.; Kharbach, J.; Vanagas, J.; Vilkelytė, Ž.; Tolvaišienė, S.; Gudžius, S.; Kalvaitis, A.; Lehmam, O.; Masrour, R.; Hammouch, Z.; et al. Advanced State of Charge Estimation Using Deep Neural Network, Gated Recurrent Unit, and Long Short-Term Memory Models for Lithium-Ion Batteries under Aging and Temperature Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nielsen, I.E.; Tripathi, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Ramachandran, R.P.; Rasool, G. Transformers in Time-Series Analysis: A Tutorial. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 42, 7433–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, A.; Jaramillo-Morán, M.A.; Sandubete, J.E. Back to Basics: The Power of the Multilayer Perceptron in Financial Time Series Forecasting. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Chen, S.; Alkali, B. Lithium-Ion Battery Capacity Estimation Based on Incremental Capacity Analysis and Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Energies 2024, 17, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Y. LSTM-Based Estimation of Lithium-Ion Battery SOH Using Data Characteristics and Spatio-Temporal Attention. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Xia, C.; Liu, Y. Li-Ion Battery Capacity and State-of-Health Prediction through Novel Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs). Int. J. Eng. Work. 2025, 12, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, G.H.H.; Alam, M.W.; Avinash, G.; Kumar, R.R.; Ray, M.; Barman, S.; Singh, K.N.; Naik, B.S.; Alam, N.M.; Pal, P.; et al. Transformer-Based Deep Learning Architecture for Time Series Forecasting. Softw. Impacts 2024, 22, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).