Abstract

Milk is widely consumed due to its high nutritional value and ease of digestion. However, because it is highly perishable, it requires specific technologies to ensure its microbiological safety and preserve its characteristics. Thermal methods such as pasteurization and UHT are common, but the growing demand for more natural foods is driving interest in less invasive alternatives. This study reviews emerging technologies in milk processing, such as freeze-drying, ultrasound, supercritical carbon dioxide, ohmic heating, pulsed electric fields, high pressure, ozonation, cold plasma, and pulsed light. These methods show potential for eliminating microorganisms with reduced nutritional loss and environmental impact. Despite advances, challenges remain for their large-scale application, especially in process standardization and economic viability. This analysis contributes to expanding knowledge about these technologies, offering pathways for innovation, sustainability, and greater alignment with today’s consumer demands.

1. Introduction

Milk is consumed daily by billions of people worldwide and is recognized as a complete food. Milk provides essential macro- and micronutrients for the growth and development of the human body. Its protein is considered to have high biological value, as it presents all essential amino acids and exhibits high digestibility. Milk contains an average of 3.6% protein, with 80% being casein and 20% being whey protein. There are four casein fractions, α-s1, α-s2, β, and κ, that self-assemble into supramolecular structures called casein micelles (CM). In addition to proteins, milk contains about 4.6% lactose, 0.7% mineral salts, 3.6% fat, and 87.5% water [1]. Due to its high water content, the milk must be kept at low temperatures from the rural property to the beneficiary industry [1,2].

Milk has been an essential part of the human diet for thousands of years, valued for its nutritional richness and versatility. In the pre-industrial era, milk preservation and treatment were primarily based on traditional and empirical practices such as boiling. These methods, while effective to some extent in preventing spoilage and improving digestibility, lacked consistency and control. Interestingly, some of these age-old techniques share conceptual similarities with modern processes that aim to ensure microbial safety and enhance shelf life without compromising nutritional value. However, today’s technologies offer a level of precision, efficiency, and scalability that was previously unimaginable. Because milk is a perishable product, it requires technologies to extend its shelf life, ensuring its nutritional quality and food safety for consumers [3].

Most available reviews tend to focus on either conventional thermal processes or emerging non-thermal technologies, rarely integrating both under a unified framework. Moreover, as consumer demand shifts toward minimally processed and more “natural” dairy products, there is a growing need to reassess and compare these technologies through a contemporary lens. Therefore, technologies would enable the dairy industry to obtain high-quality dairy products. Emerging technologies are not usually used by industry. They are suggested for use in food processing/preservation because they do not cause undesirable changes in food and can be used instead of or in conjunction with conventional methods [4,5]. Conventional methods, on the other hand, are those well-established, consolidated, and usually employed by the industry. Like conventional methods, such as pasteurization and ultra-high temperature (UHT), emerging technologies will only be effective if the milk has adequate sanitary conditions. In the dairy industry, technological processes are diverse in their applications and functionalities, including the subtraction, addition, and separation of components, which add commercial value to milk and its dairy products, and eliminate microorganisms. In this case, the thermal processes are the most widely used in industry [6].

The growing demand for high-quality products highlights the need for new processing/preservation technologies that ensure microbiological safety, extend shelf life, minimize biochemical changes, and preserve the nutritional and sensory quality of the milk. It is also important to know the technologies and processes that enable us to achieve the desired results. The importance of a review approach to emerging technologies in dairy product processing lies in the uniqueness of this theme, as previous studies have treated these topics in isolation [7]. In addition, applying these emerging technologies remains a challenge for industries, as most have not yet been applied industrially in dairy products. Therefore, the objective of this review is to discuss the principles, mechanisms, and practical applications of these emerging technologies—thermal and non-thermal—used in dairy processing, highlighting their potential benefits, limitations, and perspectives for industrial implementation.

2. Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies in Milk Processing

Emerging technologies are those used as consolidated processes but are not yet widely adopted by the industry, as well as those that are completely innovative. These emerging technologies aim to comply with legislation, ensure food safety and product validity, reduce nutritional losses, develop functional and sensory properties, improve the acceptance of certain products, or minimize the generation of effluents while considering their environmental impact. In addition to these technologies, various thermal and non-thermal methods are employed in milk processing. The main focus of the present manuscript was to review the following technologies: freeze-drying, supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2), ultrasound, ohmic heating, pulsed electric field, high pressure, ozonation, cold plasma, and pulsed light.

2.1. Freeze-Drying

Freeze-drying, also known as lyophilization, involves removing water previously frozen but present in the food using sublimation with a vacuum, thereby transforming the water in the food from a solid to a gaseous state without passing through the liquid state. In freeze-drying, low pressure is used to favor the vaporization point of water at lower temperatures. This technology utilizes parameters to ensure that the food remains below the triple point of water. Thus, there is no melting, as the water remains in its solid state. This process consists of three steps: freezing the food, sublimation (primary drying), and desorption (secondary drying). This technology yields a porous product that is easily dissolved in water, retaining its original characteristics without changes in size, texture, flavor, aroma, or nutrients, including vitamins and proteins. For freeze-drying in milk and dairy products, they must first be frozen quickly at temperatures below −50 °C to form small ice crystals, which prevents cell rupture that can be caused by slow freezing, resulting in larger, irregular crystals. Notably, the size of the ice crystals is important in freeze-drying because the removal of water from the food depends on its resistance to heat transfer. The sublimation stage is carried out in a chamber with a vacuum application to remove previously frozen water. The frozen free water passes into the gaseous state, forming pores inside the food, by reducing the pressure applied to the chamber to keep the temperature above the critical temperature, while applying a slow drying process. The steam from the water withdrawal is removed by condensation on the refrigeration coils. At this stage, approximately 90% of the moisture is removed. In secondary drying or desorption, around 10% of the water linked to the food is removed, resulting in a final moisture content of 2%. In freeze-drying, the mass transfer rate is controlled by factors such as the water pressure gradient, the pressure in the drying chamber, and the drying temperature, which should be as low as possible. The temperature of the ice should be high enough to prevent melting [8,9]. Although freezing milk at temperatures between −50 and −80 °C offers excellent milk preservation, it is currently not used in industrial-scale operations due to high costs, energy demands, and infrastructure requirements. Standard industrial practice still maintains a temperature of −20 °C, striking a balance between quality and practicality [10].

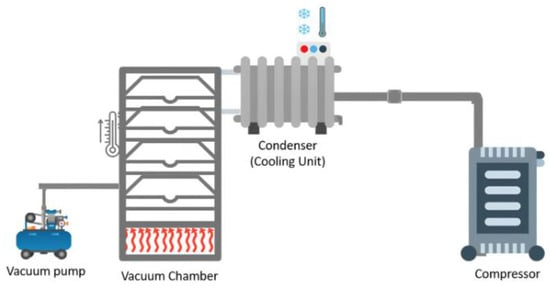

The freeze-drier features a vacuum chamber with trays, vacuum pumps, and a refrigeration unit, and can be operated in a batch, semi-continuous, or continuous process (Figure 1). Its efficiency is determined by the ratio of the sublimation temperature to the refrigeration temperature in the condenser. The advantages of this process for the product are increased shelf life, increased product quality, increased added value, easy rehydration, preservation of sensory product characteristics, lower weight and volume, reduced transport and storage costs, reduced oxidation, maintenance of the structure, good porosity, maintenance of nutritional value after rehydration, decrease in enzyme action, and decrease in protein denaturation. However, the main disadvantages of freeze-drying are the high equipment and energy costs, the need for specialized packaging, and the associated high maintenance costs. Notably, the packaging used must protect the freeze-dried product from mechanical damage and moisture, such as using packaging with films that have barriers. Like any dehydration process, freeze-drying is not used to reduce the microbial load; therefore, the raw material must undergo some heat treatment to ensure its safety [9].

Figure 1.

Scheme of the steps involved in the freeze-drying process.

One of the advantages credited to the use of freeze-drying technology in the dairy industry is the ability to use freezing temperatures for milk and dairy products. This technology is efficient for these dairy products because it can maintain their physicochemical and sensory characteristics, as well as viable lactic acid bacteria. Freeze-dried dairy products are ready for consumption, requiring only water for rehydration, are easy to transport, and do not need refrigeration. This process can be applied to thermosensitive products, such as milk and its derivatives, which can be dehydrated through freeze-drying [8].

Chandramohan [11] verified that the milk lost 50% of its mass during the first 2.5 h of the freeze-drying process. A period of 12 h is necessary to reach its solid powdered state. Harizi et al. [12] evaluated the effects of freeze-drying on the antioxidant activities of camel milk and cow milk fractions. They observed that their freeze-dried fractions showed higher ferric-reducing antioxidant power for camel and cow milk. Thus, the comparison between traditional dehydration and the freeze-drying process is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the conventional drying method using a conventional process (spray drying) and freeze-drying.

The freeze-drying process also maintains the integrity of milk fat globules, though some changes in phospholipid composition and cholesterol content may occur [13]. While freeze-drying can cause a moderate reduction in vitamin C and total antioxidant capacity, key enzymes like catalase and lysozyme remain largely stable [14]. Protein denaturation is minimal, and the retention of bioactive proteins is comparable to spray drying, especially after multiple pasteurization steps [15,16]. Besides that, freeze-drying is highly effective for preserving lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and probiotics, maintaining their viability and metabolic activity over extended storage periods [17]. The use of cryoprotectants (e.g., skim milk, sucrose, gelatin) further enhances survival rates and functional restoration upon rehydration. The process is also suitable for stabilizing starter cultures for dairy and plant-based alternatives, with minimal impact on flavor compound production [18]. Therefore, freeze-drying is a crucial technology in the dairy industry, offering superior preservation of dairy products’ physical, chemical, and structural properties compared to other drying methods. While it is more expensive than alternatives like spray drying, it is preferred for applications requiring high-quality and stable products, such as dairy bacteria and heat-sensitive ingredients. The method’s ability to maintain nutrient content and product integrity makes it valuable in producing high-quality dairy powders.

2.2. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

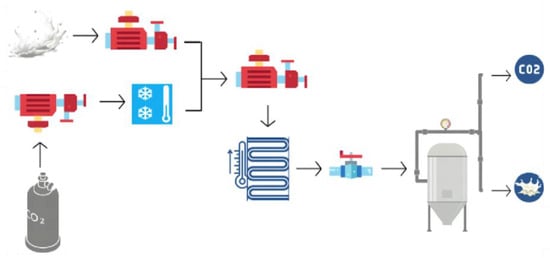

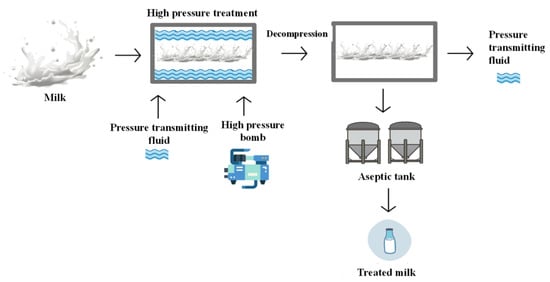

Supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2) is a technology that can be applied to food to reduce the microbial load without high temperatures, and it is a potential treatment to replace conventional treatments that use high temperatures [19]. This treatment inactivates vegetative cells, yeasts, molds, viruses, spores, and enzymes. Treatment with supercritical carbon dioxide offers several advantages, including being non-flammable, non-toxic, and inert; operating at low temperatures; not requiring ventilation; and not generating waste. It is worth noting that this treatment is specifically designed for liquid foods, as CO2 diffusion is low in solids. The stages of treatment with supercritical carbon dioxide are described in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Description of a semi-continuous system with supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2).

The mechanisms of action of treatment with supercritical carbon dioxide primarily consist of decreasing pH, leading to cell rupture due to increased internal pressure. This results in changes to the cell membrane, extraction of the lipid part, and enzymatic inactivation. Microorganism cells can be destroyed by CO2 expansion, but the moisture content in vegetative cells influences their inactivation. Cells with higher humidity increase CO2 solubility and penetration. In this treatment, slightly high pressures, temperatures between 30 and 50 °C, and a short time (approximately 5 min) are used in continuous or semi-continuous systems, with this system favoring greater interaction with the food, proving to be more effective, thus resulting in minimal losses of both nutritional and sensory quality. Equipment for this type of treatment is priced lower than other technologies. However, Paul et al. [20] reported that dairy plants are energy-intensive due to the combined loads of milk pasteurization (heating), chilling (cooling), and the demand for various supplementary equipment, making the cogeneration cycle a suitable option.

Investigating processes with supercritical fluids is necessary to evaluate the potential negative effects on the nutritional quality of the products. According to Casal et al. [21], in a study analyzing the Maillard reaction under the effect of treatment with supercritical carbon dioxide at different pH values, with pressure at 30 MPa and 50 °C for up to 5 h, using three powdered samples, casein-macro peptide (CMP) plus lactose at pH 11, β-lactoglobulin plus lactose at pH 6.5 and 7.5–9.5, both samples had control without supercritical CO2 treatment. A decrease in pH due to CO2 was observed in this study, resulting in a decrease in non-protonated reactive amino groups and, consequently, a reduction in the lactosylation rate, particularly at more alkaline pH levels. These results indicate that the treatment did not favor the Maillard reaction.

The main experimental parameters are pressure, temperature, CO2 concentration, treatment time, and, in some cases, co-solvent addition. Typical pressures range from 10 to 48 MPa (100–480 bar), with common values for milk and milk powder treatments at 100–300 bar. Temperatures are usually set between 30 °C and 80 °C, with many studies focusing on 35–75 °C to balance microbial inactivation and product quality [22,23]. CO2 is applied at concentrations such as 66–132 g/kg of milk or as a percentage of the dry feed (e.g., 2.25% by weight), while flow rates for expanded CO2 can be around 6 L/min in extraction setups [24]. Treatment durations vary from 10 to 80 min depending on the process (e.g., extraction, pasteurization, or protein modification) [22].

Dey Paul et al. [25] evaluated the optimization of process parameters for supercritical fluid extraction of cholesterol from whole milk powder using ethanol as a cosolvent. Despite being highly nutritious, the consumption of milk is hindered because of its high cholesterol content, which is responsible for numerous cardiac diseases. This study was conducted to optimize the process parameters of supercritical fluid extraction, specifically extraction temperature, pressure, and ethanol volume. According to recent studies, two-stage supercritical fluid extraction process using ethanol as a cosolvent to effectively extract phospholipids from whey protein phospholipid concentrate, resulting in a phospholipid-rich lipid fraction with enhanced water-holding and emulsifying properties. However, supercritical carbon dioxide is more efficiently utilized in the fruit and vegetable processing industries during the extraction process [26].

Supercritical carbon dioxide technology is promising for the dairy industry. It can effectively reduce the microbial load, fractionate milk fats, enhance the purity of prebiotic ingredients, extract cholesterol, and process dairy beverages while preserving or improving the quality and nutritional value of dairy products. This non-thermal method offers an alternative to traditional thermal processing, aligning with the industry’s goals of improving product safety, shelf life, and consumer health.

2.3. Ultrasound

The ultrasound method is still little applied in the food industry, but it is an alternative to thermal treatments through chemical and physical phenomena. For the ultrasound to be effective, it must be combined with moderate heat treatment, which destroys bacteria, enzymes, and spores [27]. The combination of methods can be ultrasound and pressure (manosonication, MS), ultrasound and heat (thermosonication, TS), and ultrasound with pressure and heat (manothermosonication, MTS). Of these methods, MTS inactivates the vast majority of enzymes and resistant microorganisms [28]. This observation suggests that ultrasound should be used in conjunction with pressure, heat, or both to destroy microorganisms effectively. These procedures combined make heating gentle, do not cause thermal damage as conventional processes do, and reduce the energy used. However, the application of ultrasound may not be efficient in microbial inactivation, requiring it to occur for a longer period and at a higher intensity, which may generate undesirable changes in the food. The sterilization rate of food can be accelerated, reducing the duration and intensity of heat treatment and damage to food, with the advantages of reduced flavor loss, greater homogeneity, and energy savings. According to Chemat et al. [29], the most effective method is the MTS combination, as it is capable of inactivating vegetative cells, spores, and enzymes. Therefore, this is followed by TS, which inactivates vegetative cells and spores, and finally, ultrasound, which inactivates only the vegetative cells.

The effect of reducing the microbial load of food depends on the frequency and intensity of the waves and the composition of the food being processed. The ultrasound method is based on applying ultrasound waves at a certain pressure. These waves reach the surface of the food, producing a force that can be perpendicular to a compression wave that moves through the food or parallel with a shear wave. This method should not present rapid changes in pressure to avoid the creation and collapse of bubbles, known as acoustic cavitation, which releases localized energy and produces hydroxide radicals that form cross-links with proteins. Enzyme inactivation can be explained by the change in structure along with heating.

The equipment that performs this process is a piezoelectric transducer, transmitting the ultrasound through a piece submerged in milk, with a frequency of approximately 20 kHz. High-power or low-frequency ultrasonic waves are applied to destroy bacteria since they can break cells and denature enzymes. When these high-density waves are applied in conjunction with thermal treatments at moderate temperatures, the sterilization process is completed in shorter times; consequently, processing becomes less intense, thereby reducing the damage caused to the food, such as loss of flavor and sample homogeneity. This method remains more economically viable compared to conventional methods and can be considered a more sustainable approach, aligning with current market trends. Ultrasound can be used to modify the metabolism of bacterial cells by applying low-density ultrasound. Some advantages of this process are higher yield, quality, and productivity, shorter times, and cost reduction [30].

In the ultrasound process, cavitation occurs, characterized by the increase and implosion of vapor and gas cavities in a liquid caused by pressure changes. In compression, the pressure is positive, and in expansion, it is negative, thus producing a vacuum and generating cavities. Cavitation is responsible for the death of bacteria present in food due to the formation of gas bubbles that, upon expansion, have a greater surface area as a result of gas diffusion. When the energy is insufficient to retain it, an implosion occurs; temperature and pressure increase, affecting bacterial cells. In this process, temperatures of 5500 °C and pressure of 50 MPa can be reached [30].

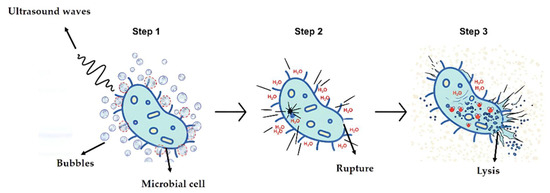

High-intensity ultrasonic waves have the power to break cells and denature enzymes; low-intensity ones are capable of modifying cell metabolism. Intracellular cavitation and mechanical shocks disrupt cellular structural and functional components until cell lysis occurs (Figure 3). The use of the ultrasound method has several fundamentals, such as disintegration, protein and enzyme extraction, lipid and protein extraction, microbial and enzymatic inactivation, ultrasonic dispersion and deagglomeration, synergy with other processes involving pressure and heat, the sonication of bottles and cans to leak detection, the release of phenolic compounds and anthocyanins, and chemical and biochemical effects. In the use of this method in the production of milk and derivatives, it is necessary to study some factors that influence the process, such as the amplitude of ultrasound waves, exposure or contact time, the volume of processed foods, composition, and treatment temperature, so that it becomes effective and ensure the safety of the product to the microbial load [30].

Figure 3.

Representation of the effect of ultrasound on the microbial cell in milk.

Step 1 = Effect of ultrasound on the cell. Ultrasound waves generate cavitation bubbles around the cell. These bubbles expand and contract rapidly. 2 = Cell membrane rupture. The collapse of cavitation bubbles creates microcurrents and shear forces that put pressure on the cell wall and membrane. This pressure causes the membrane to rupture, allowing water from the external environment to enter the cell. 3 = Cell lysis. Upon the entry of water, the cell swells and its internal structure become destabilized, ultimately leading to its destruction or disintegration, also known as lysis. This process results in the release of cellular content into the external environment.

Kilic-Akyilmaz et al. [31] applied high-intensity ultrasound (HIUS) and compared it with conventional heat treatment to extend the shelf-life of a fermented milk beverage. Beverage samples were subjected to HIUS (24 kHz, 400 W) at different power levels (25–100%) and temperatures (20–60 °C) or conventional heat treatment (60–70 °C), each for 10 min. The beverages’ acidity, whey separation, rheological, microbiological, and sensory properties were measured. HIUS at 20 °C was insufficient for inactivating lactic acid bacteria and molds/yeasts; moreover, it lowered consistency and increased whey separation. HIUS at 60 °C resulted in similar microbial inactivation, consistency, and whey separation levels to those obtained by heat treatment at 60 °C. Heat treatment at 70 °C yielded the highest microbial inactivation and the most stable sUltrasound waves generatetructure in the beverage. HIUS treatment was found to reduce particle size but caused a foreign odor and taste in the beverage, as determined by sensory analysis [31].

The effect of ultrasound (US) on fat milk globule (MFG) size and some quality properties of set-type probiotic yogurt produced with skim milk powder (SMP) or caseinate and whey protein concentrate (CWPC) was compared with conventional homogenization by Akdeniz and Akalin [32]. In this study, the US reduced MFG size to 46.5% compared to conventional homogenization. The best homogenization efficiency with the smallest MFG size was obtained using 400 W US for 15 min.

The US is a non-thermal technology that can be applied in the milk decontamination process, promoting the inactivation of pathogenic and spoilage bacteria with potential sporicidal effects. Furthermore, using the US combined with heat showed synergistic effects on reducing milk microbial load, which is hopeful for industrial applications. Studies are verifying the efficacy of ultrasound in reducing the count of microorganisms, including Listeria monocytogenes, strains of Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis [33].

Ultrasound is applied in conjunction with various techniques to enhance its efficiency, such as freezing, cutting, tempering, bleaching, and extraction. Additionally, in the context of milk and its derivatives, it can also be used in combination with pasteurization and ultra-high Temperature (UHT) treatment. However, Bernardo et al. [33] reported that the influence of bacterial morphological aspects, physical knowledge about the US, and the enhancement of pathogens’ virulence under stress conditions remains to be elucidated. Additionally, optimizing the milk decontamination process is promising, and the physicochemical properties of milk should be considered. Therefore, several studies should be conducted to understand the US in milk decontamination.

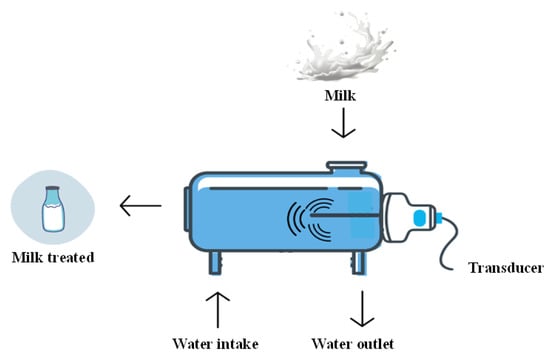

Ultrasonic pretreatment significantly accelerated the degradation of the four pesticides during yogurt fermentation. In addition, such ultrasound pretreatment increased the efficiency of yogurt making and improved the quality of yogurt in terms of water holding capacity, firmness, antioxidant activity, and flavor. These findings provide a basis for applying ultrasound to remove pesticide residues and quality improvement [34]. Ultrasound consists of three methods: direct application to the product, coupling with the device, and submersion in an ultrasonic bath. The most used industrially is the continuous ultrasound probe, which is ideal for large quantities and has a continuous flow process (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Continuous ultrasound probe process description.

Ultrasonication can significantly enhance the quality of milk by improving its texture, stability, shelf life, and safety, but the effects depend on the treatment conditions. Ultrasonication improves the water-holding capacity, gel hardness, cohesiveness, and microstructure of both acid- and rennet-induced milk gels, resulting in firmer, more stable products with reduced syneresis. These effects are observed across cow, goat, buffalo, and skim milk, and are especially pronounced at higher energy densities or power levels. Ultrasonication reduces the size of fat globules and casein micelles, increases surface hydrophobicity, and promotes protein cross-linking, resulting in a denser and more uniform protein network, which improves emulsion stability. It also retains more milk fat globule membrane proteins compared to shear homogenization, which can benefit nutritional and functional properties. Additionally, ultrasonication generally preserves or enhances the bioactive properties, antioxidant activity, and sensory attributes (taste, color, and viscosity) better than heat treatments. However, excessive intensity or duration may cause some protein or lipid oxidation and off-flavors [32,33].

Ultrasound technology offers numerous benefits for the dairy industry, including improved processing efficiency, enhanced microbial safety, and better product quality. However, its widespread industrial adoption requires overcoming certain challenges, such as precise control of process parameters and consistent microbial inactivation. Continued research and technological advancements are essential to fully realizing the potential of ultrasound in dairy processing.

2.4. Ohmic Heating

Ohmic heating is also known as Joule, electroconduction, or ohmic electrical heating [35]. Known and already used at the beginning of the 20th century, ohmic heating is still considered a technology that involves heating generated by the resistance of food to the passage of an alternating electric current, with problems related to the electrode being responsible for its limited industrial use over the past several years. Corrosion problems previously detected in electrodes are now easily solved using gold, platinum, and stainless-steel materials. Additionally, the electrodes in the ohmic treatment must be spaced at a suitable distance to achieve an efficient electric field between them. The incrustations may lead to a reduction in the electric field’s homogeneity. One way to mitigate this problem is to utilize a turbulent regime to induce convection, which generates heat through fluid movement, thereby preventing overheating on the electrode surface. In industries such as milk processing, this failure makes the equipment cleaning process difficult, causes quality loss, reduces heat transfer, and may even provide a place for microbial growth or biofilm formation, resulting in setbacks in processing [36].

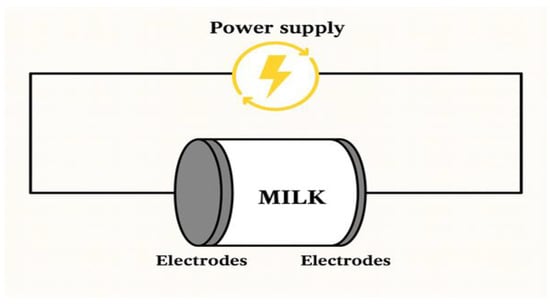

Ohmic heating is often credited with characteristics similar to the microwave process. However, these technologies differ, with one key difference being the direct contact of the food with the electrode in the ohmic treatment. Due to the search by the food industry for aseptic processing, research with interest in ohmic heating has been carried out mainly for foods that contain a substantial part [35]. In ohmic heating, the applied electric current passes through the electrodes and the milk or its derivative; as a result, movements form that agitate the molecules, generating heat and converting electrical energy into thermal energy. In milk processing, this heating method generates internal and uniform heat throughout the product, eliminating temperature gradients. Its application is preferably in liquid foods, liquids with a certain viscosity, and liquids with up to 60% of solids immersed (particulate foods). For totally solid foods, sensory changes may occur. Figure 5 shows the schematic representation of ohmic heating in milk. This technology enables efficient microbial destruction by allowing for the quick and uniform distribution of temperature within the product. It can also be an alternative to conventional High-Temperature Short Time (HTST) pasteurization and UHT treatment processes [37]. However, as it is a process that generates a temperature increase in milk, ohmic heating can result in protein coagulation and the emergence of the Maillard reaction.

Figure 5.

Representation of the ohmic heating process.

The thermal conductivities used in milk are described in Table 2. The electrical conductivity of the food to be processed by ohmic heating can be calculated if the food is composed of a liquid part and a solid part, as well as the difference between the conductivity of the product and the medium. In food or microbial cells, ohmic heating generates electroporation, which involves the formation of multiple pores that facilitate the entry of water, thereby increasing the cell’s size until it ruptures [35].

Table 2.

Representation of fluid milk’s electrical conductivity values (S/m) at different temperatures.

The equipment used in ohmic heating can be batch or continuous; both have the same constituents: electrodes, a retention tube, and an alternating electrical energy source for the electrodes. This process acts as an electrical circuit, in which the milk enters the process through a pump, coming into contact with the electrodes, forming an ohmic column, generating heat by converting electrical energy, reaching the temperature necessary to remain in the retention tube, for the minimum time necessary to achieve microbiological safety. Afterwards, cooling is carried out until reaching the ideal temperature for packaging. Some important parameters in ohmic heating include electrical conductivity, voltage, temperature, frequency, and flow properties [35].

The equipment used in ohmic heating is classified into the following four types, where the difference is in the position of the electrodes: (a) the parallel plate equipment, also called transverse configuration, has better heating, minimum shear force, and is suitable for products with low conductivity; (b) the one with parallel rods, which has the lowest cost and low heating rate; (c) the collinear, which is ideal for products with high conductivity because it has a larger space between the electrodes. However, it needs high voltages during the application, presenting a smaller and uniform electrical current; and (d) the staggered rod, which is also low cost but has a higher heating rate than parallel rods [35]. Temperature is a crucial parameter because it affects the mobility of ions in the fluid, and it must be controlled in conjunction with time, binomial time, and temperature to ensure microbiological criteria, especially in “cold spots” [38]. Figure 6 illustrates a schematic of an ohmic heating plant’s operation.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the ohmic heating mechanism and heat transfer steps during dairy processing.

There are three classifications of electrical conductivity for dairy products, as defined in Table 3. In this way, these characteristics must be considered in relation to the purpose and objectives of the application, as well as the use of this new technology being aligned with an economic study, which verifies the feasibility of changing the process [39].

Kim and Kang [40] investigated the effect of fat milk content (0, 3, 7, and 10%, m/m) on the heating rate and electrical conductivity during both conventional and ohmic treatments to compare them. In conventional processes, heating occurs through conduction and convection effects, and is not affected by the fat content. Fat has low conductivity in ohmic heating, which affects heating when electric currents bypass the fat globule, causing it to heat slowly. If there is any pathogenic microorganism, it may not be eliminated by the action of heat. The fat content interfered with the heating rate in the milk samples heated using ohmic treatment. The samples with a lower fat percentage had a higher heating rate due to their greater electrical conductivity. Fat also had an insulating effect, favoring the survival of pathogens such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes. Thus, milk and dairy products with a high content of lipids can cause “cold spots”, which are parts of the food where heating occurs more slowly, affecting the safety of the food and, therefore, a risk factor [34].

As illustrated in Figure 6, ohmic heating involves the direct passage of electric current through the food matrix placed between two electrodes. The applied alternating voltage generates an electric field, inducing ion movement and internal energy dissipation by the Joule effect. In milk, the presence of dissolved salts and charged components facilitates efficient heat generation, leading to uniform temperature rise throughout the medium. Unlike conventional surface heating, this mechanism ensures rapid and homogeneous heating, reducing nutrient degradation and improving process control.

Table 3.

Parameters of ohmic heating used in milk and its derivatives.

Table 3.

Parameters of ohmic heating used in milk and its derivatives.

| Intensity | Conductivity | Dairy Products |

|---|---|---|

| Good | >0.05 S/m | Yogurts and dairy desserts |

| Low | >0.005 S/m e < 0.05 S/m | Powder milk |

| Very low | <0.005 S/m | Ice cream, milk fat, and high-fat derivatives |

S/m = Siemens por metro. Source: Paganini et al. [41], Sun et al. [37], and Cappato et al. [38].

As shown in Table 3, ohmic heating parameters vary considerably depending on the composition and structure of dairy products. High-intensity electric fields (>0.05 S/m) are suitable for yogurts and dairy desserts, which present higher ionic content and uniform consistency, enabling efficient Joule heating [37,41]. Intermediate conductivity values (0.005–0.05 S/m) are commonly reported for concentrated or powdered milk systems, where solid concentration and viscosity influence electrical behavior. Conversely, products with higher fat content, such as ice cream or butter, exhibit low electrical conductivity (<0.005 S/m), reducing the heating efficiency and often requiring process adjustments [37,38]. These findings emphasize that the optimization of ohmic heating conditions must consider both the physicochemical properties of the dairy matrix and the desired thermal profile.

Bhat et al. [42] demonstrated that ohmic heating has the potential to induce structural and conformational changes in proteins, which can affect the behavior of milk proteins during gastrointestinal digestion. This study examines the impact of this technology on the protein colloidal behavior and the coagulation/aggregation of milk proteins, which play a crucial role in the digestion of milk proteins at elevated milk temperatures. The scientific literature has documented the performance of ohmic heating, highlighting its effectiveness in destroying microorganisms, inactivating enzymes, and preventing damage to milk components, which leads to the consequent microbiological and physicochemical stability of the processed milk during storage. However, the combination of an alternative technology with mild thermal treatment, such as ohmic heating, currently represents the sole realistic approach to producing fresh-like/high-quality pasteurized milk [43].

Ohmic heating presents several advantages for the dairy industry, including better preservation of nutritional and sensory qualities, effective microbial inactivation, and enhanced probiotic activity. It also offers energy efficiency and faster processing times. However, challenges such as fouling on electrode surfaces need to be managed. Overall, ohmic heating is a promising technology for improving the quality and safety of dairy products.

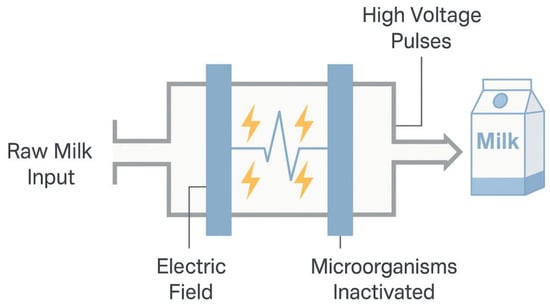

2.5. Pulsed Electric Field (PEF)

The pulsed electric field (PEF) treatment consists of applying very short electric pulses (microseconds or milliseconds) with high electric field intensities (18–80 kV/cm), resulting in milder temperatures. This process can also destroy microorganisms through electroporation, as well as ohmic heating. However, ohmic heating will result in a rise in food temperature. The efficiency of the pulsed electric field depends on the intensity used, treatment time, food temperature, and the type of microorganism to be eliminated. It is worth noting that studies have demonstrated a reduction in changes to food composition compared to conventional methods [41].

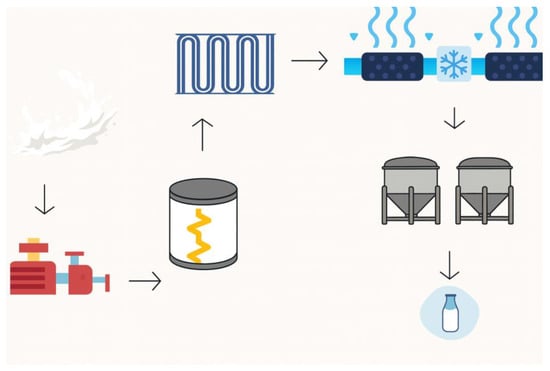

The pulsed electric field is a technology that was used for the first time in the 1960s by Doevenspeck, who was known at that time as non-thermal “pasteurization” since it has the same objective as conventional heat treatments, but without heating, avoiding losses of original characteristics of the raw material, and is not efficient against bacterial spores. The pulsed electric field treatment system consists of a treatment chamber and a filling system (Figure 7). This treatment offers several advantages, including enhanced retention of sensory and nutritional characteristics, improved protein functionality, and extended food shelf life. In the case of this technology, pulsed electric fields of short duration are applied to minimize the Joule effect. Thus, electrical and non-thermal effects are used [41].

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the steps of the pulsed electric field (PEF) process.

The ideal raw material for PEF processing is liquid foods, as they possess characteristics such as easy pumping, allowing for a continuous flow, and being less prone to dielectric breakdown—a phenomenon related to the electrical conductivity of the food. Solid or particulate foods are more susceptible to this phenomenon [44].

The effect on microorganisms is destabilizing the lipid bilayer and membrane proteins. The electric field promotes electroporation and electrofusion effects in cells, causing membrane permeabilization by forming pores. This behavior occurs when the critical potential value of the electric field is exceeded, which is when values of field intensity and treatment time are exceeded. As the intensity of the applied electrical pulse is aimed at inhibiting microorganisms, if the intensity of the pulse is high, that is, above the critical potential of the electric field, the greater the microbial destruction. The lethality of the treatment against microorganisms must be determined based on the species and strain, morphology, concentration, and growth phase. A pulsed electric field has been proven effective for food production, as it prevents the loss of thermolabile micronutrients, generates safe products, and retains physicochemical and sensory properties similar to those of unprocessed food [44,45]. In addition to its effect on microbial elimination, this technology also inactivates enzymes. The inactivation of enzymes occurs through a change in their structure due to the action of an electric field, generating a change in the structural conformation of the enzyme, which is, in effect, its denaturation. PEF can also be used in conjunction with other methods, such as pasteurization, high hydrostatic pressure, antimicrobial agents, and pH reduction, to help preserve food.

The operating mechanism of the pulsed electric field is composed of an electric pulse generator system, having a high-voltage source and another high-voltage generator, capacitors to store the charge, discharge alternators to release the charge to the electrode, inductors to modify the waveform of the electric fields, electric resistances, oscilloscope to measure the intensity of the electric pulses, system for controlling the flow of the product and a treatment chamber. The chamber where the food will be treated has two electrodes. The types of continuous equipment are the most suitable, as they have a continuous flow, and parallel plates are the most suitable for this purpose. Some key characteristics of the food must be considered, including electrical conductivity, density, specific heat, and viscosity. A refrigeration system is in place to prevent excessive heating of the product, which can reach temperatures of up to 30 °C and 40 °C, thereby increasing the lethal effect on microorganisms without any changes occurring. Still, this cooling system will lose all the heat produced [45].

In the pulsed electric field, the product receives several successive electric pulses, ensuring that the electric potential in the electrodes returns to zero in each interval, thereby preventing electrochemical reactions from occurring. The characteristics of this process can be divided into four related groups: the generation of pulses, the processing chamber, the type of system employed, and the inactivation activity of microorganisms and enzymes, both of which influence the processing efficiency. In enzymatic inactivation, the factors are the parameters of the process itself, enzyme structure, temperature, and suspension medium. During the process, dielectric breakdown should be avoided to prevent the electric field from exceeding the dielectric strength of the food. The electrical pulse can be exponential, square, bipolar, or oscillating in nature. In the exponential pulse, the electric field reaches a maximum value, and then its value drops exponentially. In the square pulse, the electric field reaches a maximum value and maintains it for a certain time, then drops sharply. Bipolar and oscillating circuits can produce these forms [45]. Bipolar pulses show greater lethality due to a rapid electric field reversal, causing stress to microbial cells, while square-shaped pulses are more lethal than exponential ones.

Table 4 and Table 5 present the processing conditions for different types of milk using a pulsed electric field to reduce certain types of microorganisms and inactivate specific enzymes, respectively. Table 4 illustrates the impact of pulsed electric field conditions on microorganisms in a specific dairy product. Table 5 addresses the influence of parameters on the enzymes present in milk. The presence of the microorganisms listed in Table 4 in milk and dairy products is primarily due to the nutrient-rich environment of milk and multiple contamination routes from animals, the environment, and processing equipment. Effective hygiene, pasteurization, and monitoring are essential to minimize their presence and ensure dairy safety. The primary action of enzymes in milk and dairy products varies. Protease, lipase, alkaline phosphatase, and peroxidase are involved in protein hydrolysis [46], fat hydrolysis, phosphate metabolism, and oxidative stress response [47]. With these positive results for the different types of milk, the application of pulsed electric fields in the dairy industry is likely to be promising in the future. It may be an alternative to conventional pasteurization, offering advantages such as the maintenance of sensory characteristics and nutritional value [43].

Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) technology is a promising non-thermal method for milk processing in the dairy industry. It effectively inactivates microorganisms and enzymes, preserves milk’s nutritional and sensory qualities, extends shelf-life, and is energy-efficient. However, further research and optimization are necessary to fully realize its potential for industrial applications fully.

Milk treatment using PEF has limitations related to the uniformity of electric field distribution, flow characteristics, and temperature control. Lack of homogeneity in the treatment chamber can lead to uneven processing, compromising efficiency and jeopardizing product quality. Furthermore, electrode corrosion and electrochemical reactions can introduce contaminants, affecting milk quality, especially at high temperatures or with prolonged use. Furthermore, high capital investments and integration challenges for large-scale, reliable, and affordable PEF systems further hinder widespread industrial adoption [48,49].

Table 4.

Processing conditions of different kinds of milk using a pulsed electric field, aiming at microbial reduction.

Table 4.

Processing conditions of different kinds of milk using a pulsed electric field, aiming at microbial reduction.

| Microorganism | Dairy Product | Log Reduction | Process Conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of the Field (kV/cm) | Temperature (°C) | Pulses Number | Pulses Duration (s) | |||

| Escherichia coli | Milk | 3.0 | 28.6 | ~43 | 23 | 100 |

| Skimmed milk | 3.5 | 5.0 Square | <30 | 48 | 2 | |

| Listeria innocua | Raw skimmed milk | 2.6 | 50 with 3.5 Hz Exponential | 15–28 | 100 | 2 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Pasteurized whole milk | 3.0–4.0 | 30 with 1700 Hz Bipolar | 10–50 | 400 | 1.5 |

| Whole milk | 2.5 | 30 | 25 | 400 | - | |

| Whole milk | 4.0 | 30 | 50 | 400 | - | |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Raw skimmed milk | 2.7 | 50 with 4 Hz exponencial | 15–28 | 30 | 2 |

| Salmonella dublin | Skimmed milk | 3.0 | 15–40 | 10–50 | - | 12–127 |

| Skimmed milk | 1.0 | 25 | 30 | 100 | - | |

| Skimmed milk | 2.0 | 25 | 50 | 100 | - | |

| Milk | 3.0 | 36.7 | 63 | 40 | 100 | |

Source: Adapted from Bendicho et al. [50].

Table 5.

Processing conditions of different kinds of milk using a pulsed electric field, aiming at enzymatic inactivation.

Table 5.

Processing conditions of different kinds of milk using a pulsed electric field, aiming at enzymatic inactivation.

| Enzyme | Dairy Product | Decreased Enzymatic Activity (%) | Process Conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Intensity (kV/cm) | Pulses Number | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase | Skimmed milk | 65 | 18.8–22 | 70 |

| Milk with 2.5% fat | 59 | |||

| Whole milk | 59 | |||

| Milk with 1.5% fat | <10 | 21.5 | 20 | |

| Milk with 3.5% fat | <10 | |||

| Raw milk | 65 | 18–22 | 70 | |

| Milk with 2% fat | 65 | 18–22 | 70 | |

| Peroxidase | Milk | 30 | 21.5 | 20 |

| Raw milk | >3 | 13–19 | 200 | |

| Lipase | Milk | 60 | 21.5 | 20 |

| Protease from Pseudomonas fluorescens | Skimmed milk | 60 | 14–15 | 98 |

Source: Adapted from Bendicho et al. [50].

2.6. High-Pressure

The high-pressure process was first reported by Bert Hite in the 19th century when it was applied to milk. This process is considered a technology capable of destroying deteriorating and pathogenic microorganisms without the need for heating. It can be applied in addition to or as a replacement for heat treatments, maintaining virtually all of the sensory and nutritional characteristics. This process uses pressures between 100 and 800 MPa in liquid and solid foods with more than 40% free water, using temperatures lower than conventional, such as negative or ambient temperatures. The high-pressure process is also known as high hydrostatic pressure (HHP), high isostatic pressure, or ultra-high pressure. To install a high-pressure process, one must consider the cost of the currently widely available and varied equipment, automation, installation, labor, product, packaging, and the entire process. Several countries employ the high-pressure process in product development, such as Canada, the United States, Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Norway, Finland, Poland, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, India, Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and Brazil. It is a technology that is increasingly widespread and available to industry, with the development of products considered to have more improved and innovative characteristics [3].

Studies have successfully demonstrated the inactivation of enzymes in foods at room temperature over a period longer than 15 min. However, the high-pressure process can be combined with other technologies, such as CO2 treatment, to inactivate pathogenic microorganisms, including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Another combination is with natural antimicrobials, such as nisin, which, when combined with high-pressure processing, can inhibit Salmonella bacteria. It was verified that high pressure and negative temperatures could inactivate Listeria monocytogenes and E. coli in fish and fruit juice. Thus, studies have verified that this process is effective against pathogenic bacteria, yeasts, molds, and other deteriorating organisms. Despite being a lethal process for microorganisms, the breaking of covalent bonds does not occur, not affecting the macro- and micronutrients present in the food. The parameters evaluated in studies that used high pressures were pressure, temperature, and time. When applied in conjunction with other technologies, the composition of the food, the salt content, and the presence of ions were also evaluated [51].

Pressure-assisted thermal processing, also known as sterilization, is a high-pressure process. In this type of processing, a moderate temperature of 60 to 90 °C is used, combined with a high pressure of 600 MPa to 800 MPa, for 5 min to inactivate spores and preserve low-acid foods. This process aims to apply temperatures lower than conventional sterilization temperatures (121 °C), not to alter the food, but to guarantee microbial inactivation while maintaining the original product’s characteristics, with a shorter process time and milder temperatures. The high-pressure and high-pressure-assisted thermal processes can be performed with the packaged product. However, to prevent damage from pressure, the product must have sufficient moisture, and the pressure must be uniform across its surface. In the high-pressure process, pressure transmission is achieved using a fluid in the system; however, this method cannot be applied to foods with a porous structure. Foods subjected to this process use flexible packaging or plastic containers, which must be submerged in a liquid, allowing pressure to be uniformly distributed throughout the food. Using this technology, an increase in temperature is also observed due to the adiabatic heating of certain compounds present in the food, such as water. Thus, before being subjected to the container discharge process, the package must be filled with the pressure-transmitting fluid and water, then sealed and pressurized using a high-pressure pump. In the case of liquid and non-packaged foods, semi-continuous equipment is used, while the process is discontinuous/batch for liquids in packaging. In the discontinuous process, the direct compression generated in the pressure tank by the compression liquid (water) occurs over a set period, typically a few minutes. Processing parameters will be defined according to the composition and properties of the food, such as pH, water activity, and the type of microorganism that may be present [51].

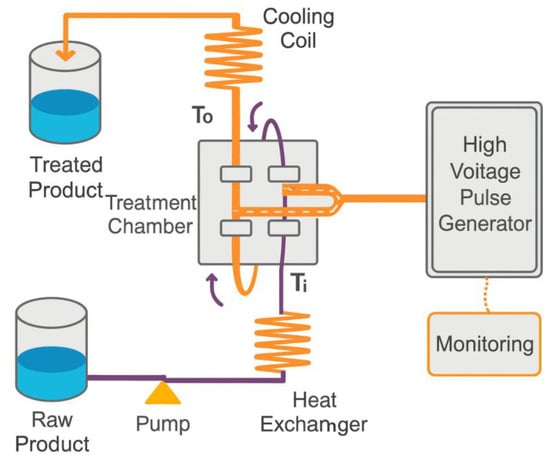

The effect of the high-pressure process on microorganisms results from changes in the non-covalent binding of proteins, which could damage cell multiplication and integrity, leading to cell death. In this process, 3 to 5 min and a pressure of 600 MPa are generally used to influence microorganisms, with the food receiving 5 to 6 cycles per hour, generating compression, retention, decompression, loading, and unloading. Slightly higher cycle rates may be possible using fully automated loading and unloading systems. The packages are subjected to high pressure, and after the minimum time necessary for the product at the target pressure, the container is decompressed by releasing the pressure-transmitting fluid, which is then removed from the container and stored [52] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Representation of the high-pressure processing.

The high-pressure process generally offers advantages, including the reduction of vegetative cells and spores, as well as the preservation of food color and flavor. It is considered uniform processing with low energy consumption and is carried out with packaged food. A disadvantage of the high-pressure process is the high cost of the equipment, which is not fully continuous. In the dairy industry, it is common practice to reduce the microbial load of fluid milk and improve the quality and yield of derivatives, such as cheese and yogurt [53]. The quality of high-pressure foods is very similar to that of fresh products, and their quality over time is influenced by later distribution and storage temperatures, as well as by the barrier properties of the packaging rather than the process itself.

Alpas and Bozoglu [51] combined the use of high pressure (345 MPa) with a temperature of 50 °C for the inactivation of pressure-resistant pathogenic microorganisms in pasteurized milk, including Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella (S. enteritidis and S. typhi). After the high-pressure process, only Staphylococcus aureus survived, with a reduction of 5.5 log CFU/mL of milk. In comparison, all other microorganisms were inactivated, with a reduction greater than 8 log CFU/mL of milk. The milk was stored for 24 and 48 h at 37 °C, and in selective media, the growth of S. aureus was observed, while L. monocytogenes was only observed at 37 °C for 48 h [51].

Pinho [54] evaluated the high-pressure homogenization process for the processing of skimmed milk and the inactivation of Pseudomonas fluorescens, Listeria innocua, and Lactobacillus helveticus, applying pressures ranging from 100 to 300 MPa. Milk samples were inoculated with the microorganisms to achieve a concentration of between 6 and 7 log CFU per mL of milk. This study yielded results indicating the complete inactivation of the inoculated microorganisms at pressures of 200 MPa for Pseudomonas fluorescens, 250 MPa for Listeria innocua, and 260 MPa for Lactobacillus helveticus. In this study, the inactivation of Bacillus stearothermophilus spores was also evaluated, where 5 logs of spores were inoculated per mL of milk at a pressure of 300 MPa. After performing this stage, no reduction in spore counts was observed, even at the maximum pressure of 300 MPa used. This process was also successfully applied to milk, but the most extensively evaluated derivatives, particularly those from the high-pressure process, were used for yogurt, cheese, and cream. However, changes in the properties of these dairy products were verified. In milk, the high pressure used in the homogenization process reduces the size of fat globules, in addition to inactivating microorganisms and enzymes [51]. Muñoz et al. [55] evaluated the effect of high hydrostatic pressure processing on the rennet coagulation kinetics and physicochemical properties of sheep milk rennet-induced gels. They concluded that 300 MPa is the optimum treatment pressure for milk intended for cheesemaking by enzymatic coagulation. This pressure produced milk with optimal coagulation kinetics and water-holding properties, resulting in the least loss of fat and protein to the whey.

Wu et al. [56] combined high pressure with moderate heat (50 °C) pre-incubation to explore an alternative processing method for reducing the levels of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in milk. Single-factor experiments showed that high-pressure intensity was negatively correlated with the levels of 5-HMF and AGEs, while positively correlated with microbial inactivation. This study also observed that a 50 °C pre-incubation for 20 min, followed by 600 MPa for 15 min, was the optimal processing condition.

High-pressure processing is a valuable technology in the dairy industry, offering numerous benefits, including effective microbial inactivation, improved sensory and functional properties, extended shelf life, and support for clean label production. These advantages make high-pressure processing a promising alternative to traditional thermal treatments, meeting consumer demands for high-quality, safe, and innovative nutritious dairy products.

2.7. Ozonation

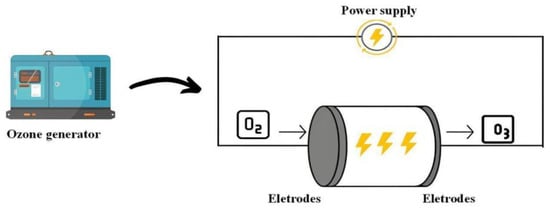

Ozonation utilizes ozone, a triatomic form of oxygen (O3), which exhibits antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and bacteriophages. Ozone can be used in gaseous or liquid form, the production of which results from the use of 185 nm ultraviolet light, involving an application of high voltage to oxygen (O2), causing the oxygen molecules to break down and reorganize to form the O3 (Figure 9). In food, the most used form of ozone is liquid, where these products are immersed in this ozonized water, needing to verify the efficiency of the ozone concentration (mg/L) and contact time (minutes). As it is an unstable compound, it must be ensured that it does not react with the product’s equipment and packaging, requiring that all materials used be highly resistant to ozone. The most suitable materials are stainless steel, Teflon®, glass, polyvinyl chloride, and polyethylene. However, ozone has the advantage of not leaving chemical residues in the food and degrading it into O2. Disadvantages would be a possible change in color, odor, and oxidation of food compounds [57,58].

Figure 9.

Representation of the ozone generation process.

In microorganisms, the use of ozone is due to its antimicrobial action. Lipid oxidation reactions cause this action due to the formation of free radicals in water, where the unsaturated lipids of the cell walls of microorganisms lead to cellular leakage. Some bacteria that can be destroyed are E. coli O157:H7, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes. This process can be combined with other methods for better efficiency [50].

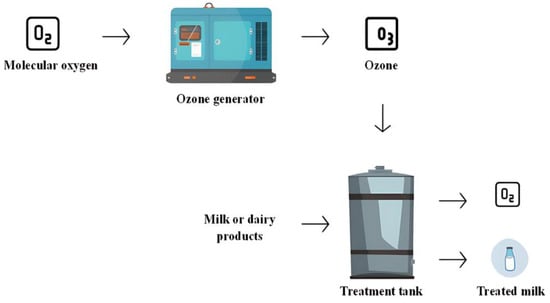

In raw milk, Santos [57] evaluated the use of ozone in reducing mesophilic aerobic microorganisms and the occurrence of physicochemical changes after treatment (Figure 10). This study employed different ozone concentrations and process times. In the end, 1 log CFU per mL of milk was reduced using 15 min of the ozonation process with 15 mg of ozone per liter of water, or 30 min of the process with an ozone concentration between 5 and 10 mg per liter of water. In this study, a change in the color of raw milk was observed, returning after 2 or 3 h. Alterations in the initial composition of raw milk were also observed, with reduced fat, defatted dry extract, lactose, density, and protein, when 18 mg of ozone per liter of water and a time of 10 min were used.

Figure 10.

Representation of the ozonation process of milk and derivatives.

Couto [59] evaluated the efficiency of ozone in milk, verifying a reduction in the count of Staphylococcus aureus colonies. In four samples of milk, S. aureus was inoculated. Two samples of skimmed milk were treated with 34.7 and 44.8 mg of ozone per liter of water, and two samples of whole milk were also treated with 34.7 and 44.8 mg of ozone per liter of water. The times used were 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min, and bacterial counts were taken before and after ozonation of the samples. The results showed that skimmed milk had the greatest reduction in S. aureus, while whole milk, with a higher fat content, had the lowest reduction in microbial counts. It was also found that for skim milk, reductions in the count began after 10 min of treatment, with the effect more pronounced after 20 min. Munhõs [60] studied the efficiency of ozone in microorganisms of the genus Pseudomonas inoculated in five samples of whole UHT milk and five samples of skimmed milk in a concentration of 28 mg of ozone per L of water for 5, 10, and 15 min, and possible chemical changes after ozonation. The groups were divided into control, contaminated control, and ozonated contaminated control. After 10 min of treatment, a 4-log reduction in CFU per mL of milk was observed in samples of whole and skim milk. After 15 min, the reduction was even more significant for skimmed milk than for whole milk, and the fat content can also explain this difference. There were no changes in the pH and acidity index of UHT milk. In both studies, the efficiency of destroying the microorganism was dependent on the treatment time with ozone; that is, the longer the exposure time, the greater the efficiency. They also found that the milk fat content interfered with the efficiency of the ozone treatment, but no changes in pH were observed. The study was conducted using various milk samples, but the best results in reducing the microorganism count were obtained from samples with low fat content [2].

Recently, Liu et al. [61] evaluated the removal of antibiotics from milk via ozonation in a vortex reactor and observed that antimicrobial-susceptibility testing results demonstrate no toxicity in milk samples after ozonation. Perna et al. [62] studied the effect of ozone treatment exposure time on the oxidative stability of cream milk. They noted that this preliminary investigation showed the reactivity of ozone with organic matter (lipids) contained in milk cream and, consequently, the effects on the color of the sample’s surface. These authors concluded that excessive exposure to ozone treatments caused lipid oxidation by forming metabolites that negatively affect health safety. Table 6 shows some optimal parameters used during the ozonation of milk.

Table 6.

Optimal condition parameters are used for ozone milk.

Ozonation is a promising technique for the dairy industry, offering significant antimicrobial benefits without compromising milk quality. It removes antibiotics and other pollutants from milk and dairy effluents, improving food safety and environmental protection. The process is adaptable to various conditions and can be optimized for different applications within the dairy sector.

As shown in Table 6, the optimal ozone treatment parameters depend on the physicochemical characteristics of each dairy product. In general, ozone concentrations between 25 and 45 mg L−1 applied for 10 to 25 min have been effective in microbial inactivation across milk types, without significant alterations in sensory or nutritional properties. However, the treatment efficiency is influenced by fat content, initial microbial load, and temperature. Studies suggest that whole milk requires higher ozone doses due to its greater organic matter, while skimmed and UHT milk respond well to moderate concentrations, maintaining desirable quality attributes.

2.8. Cold Plasma

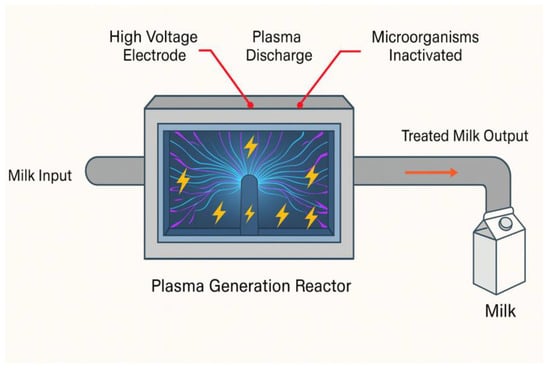

The use of cold plasma dates back to the 18th century, with Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. Cold plasma is a non-thermal technology that inactivates microorganisms through energized reactive gases; it is known as the fourth state of matter, consisting of an electrically energized gas. It can be divided into thermal and cold plasma, but only cold plasma will be discussed here [63].

The plasma is produced by passing a molecular or inert gas through a high-voltage electric field at low temperatures, either at atmospheric pressure or under reduced pressure. This condition creates an electric field that increases the kinetic energy of the free electrons present in the gas, causing them to collide with atoms and undergo ionization, releasing electrons. In the plasma, there are neutral molecules, electrons, and positive and negative ions, which present an equilibrium with a total neutral charge. In the formation of the electric current, the disposition of the electrodes is important for the efficiency of the plasma jet. Thus, energized particles and ultraviolet light can inactivate microorganisms by disrupting the cell membrane. The cost must be evaluated; equipment must be found at a lower cost, capable of processing continuously and at high speed, and operating with different gases to use this technology. Plasma sources that generate plasma jets with effective antimicrobial effects are classified by excitation frequency and electrode configuration. Each type of treatment must be suitable for the product, and models are currently available on the market only for specific applications [64].

Figure 11 shows the schematic representation of a cold plasma system. The gases studied for the plasma are oxygen (O2), a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen (N2/O2), helium (He), argon (Ar), a mixture of argon and oxygen (Ar/O2), and a mixture of helium with oxygen (He/O2). Cold plasma treatment does not require high temperatures, making it suitable for heat-sensitive foods like milk. During plasma application, various agents can act, including ozone, hydroxyl radicals, reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, ultraviolet radiation energy, radiation in the visible and infrared spectral ranges, charged particles, alternating electric fields, and physical and chemical corrosion processes. These actions enhance the antimicrobial effect by combining several actions against microorganisms, where few will resist all these agents [64]. In microorganisms, the effect is caused by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, as well as an oxidation reaction in the double bonds of the lipid bilayer within the microbial cell. The effect of cold plasma is due to the bombardment of these agents, which are absorbed by the microorganism and transformed into volatile compounds, causing damage to the cell. The inhibitory effect on enzymes occurs through the oxidation reaction of peptides, which alters the conformation of proteins and reduces enzymatic activity. In milk and its derivatives, the efficiency of using cold plasma depends on the type of microorganism, the input power, the exposure time, the composition of the gas used to generate the plasma, and the composition of the food. According to the studies, there are no significant alterations in physicochemical characteristics. Color differences are reported by analysis but not visually detectable, and greater acidity is observed through the reactions of reactive species generated by plasma [63].

Figure 11.

Representation of the basic configuration for plasma generation.

Gurol et al. [65] evaluated the antimicrobial effect of cold plasma in whole, semi-skimmed, and skimmed UHT milk inoculated with E. coli ATCC25622 containing 7.78 log CFU per mL of milk. The parameters used were 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 20 min, with a 9 kV supply. After 3 min of treatment, a reduction of 3.63 logs was observed in all samples, with no interference from the product’s fat content. In contrast, between 15 and 20 min, the reduction was greater than 4 logs. Regarding the color, there were no changes in the UHT milk samples compared to raw milk, with a noticeable difference after 20 min. The pH also changed, having no connection with the antimicrobial effect. According to the results obtained in this study, cold plasma treatment proved to be an efficient method for microbial reduction [57].

Coutinho et al. [63] studied the effect of cold plasma treatment on a dairy beverage with chocolate, using different times (5, 10, and 15 min) and flow rates (10, 20, and 30 mL per minute), with a power of 50 kV, in a total of nine trials. Among the physicochemical characteristics analyzed, the pH in the treatments with cold plasma increased, which can be explained by the non-occurrence of the reaction of lactose, as in thermal processes, forming acidic compounds, being a positive point because, in these products, the consumer does not require an acidic product [63].

Cold plasma technology can be applied to deactivate microorganisms, ensuring the safety of dairy products. In addition to being environmentally friendly, it does not generate waste, exhibits a high antimicrobial effect, accurately generates adequate plasmas, is compatible with various types of packaging, operates without heat, and has a minimal impact on the product being processed. Regarding the disadvantages of the process, accelerated lipid oxidation occurs in products with a high lipid content, negatively affecting the sensory properties, and it cannot be applied to products with irregular surfaces. More studies are needed to verify these parameters and determine how to circumvent them, as well as to analyze the retention of nutritional value and stability. Its application in food is not yet being explored, requiring a database with data on its large-scale viability to ensure a safe product. Still, it is a quoted alternative to replace thermal pasteurization [63].

According to Coutinho et al. [63], regulating this technology would not be simple due to the complexity of food composition and variety, requiring numerous studies to ensure final quality and food safety. Validation of comparable products for a given technology can expedite this process. One way to apply these non-thermal processes would be in combination with other thermal or even non-thermal processes, an approach known as “barrier technology”, based on the microbiology of food, so that efficiency against microorganisms can be increased without causing nutritional changes and sensory changes, by reducing the severity of traditional treatments [66].

Ali [67] observed that cold plasma affected milk fat globule membranes through thermal treatment, causing the globules to aggregate and increasing particle size. In this study, cold plasma permitted protein-lipid interaction. However, in this study, the effectiveness of cold plasma was most likely not similar to that of thermal treatment, specifically in terms of pathogenic count; however, this cannot be denied. Nikmaram and Keener [68] evaluated the degradation of aflatoxin M1 in skim and whole milk using high-voltage atmospheric cold plasma, as well as the quality assessment. These authors observed that cold plasma is a promising technology for efficiently degrading aflatoxin M1 in skim and whole milk, achieving a reduction of more than 87% after only 3 min of treatment and 4 h post-treatment. These same authors also verified that reactive oxygen species, including ozone, the OH radical, and singlet oxygen, constitute the most important antimicrobial species generated by cold plasma using MA65 gas. Overall, the quality parameters of skim and whole milk were minimally affected by the prescribed treatment conditions; however, longer treatment time and increasing post-treatment storage times may further exacerbate chemical changes. Nguyen et al. [69] researched the control of aflatoxin M1 in skim milk by high-voltage atmospheric cold plasma. In this case, the authors verified that 5 min of cold plasma treatment reduced the toxicity of aflatoxin M1 by 83.9%. Therefore, both authors affirmed that cold plasma is a promising method to reduce aflatoxin M1 in milk.

Sharma et al. [70] investigated the atmospheric cold plasma-induced changes in milk proteins, and their results highlighted the capacity of N2–O2 plasma treatment to denature whey proteins. The results obtained by these authors also highlighted the changes in the dominant chemical interactions in proteins caused by cold plasma, which contribute significantly to the functionality of milk-like gelation. This study demonstrates that the potential of cold plasma lies in creating dairy products with unique textures and physicochemical properties.

Wang et al. [71] stated that dielectric barrier discharge cold plasma processing could be an alternative to conventional pasteurization in ewe milk. The results showed that cold plasma processing caused the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in milk to increase remarkably but almost completely diminished the abundance of Bacteroidetes. In this study, the contents of aldehydes and alcohols in cold plasma-treated milk were significantly higher than those in other samples. Acids contributed mostly to the flavor of pasteurized ewe milk.

Sriraksha et al. [72] highlighted that cold plasma technology is considered a novel, potential non-thermal technique for food disinfection. These authors confirmed that plasma could effectively reduce the pathogenic microbes in milk, and they also reported that cold plasma showed minimal or no effect on the physicochemical and sensory properties of the foods owing to its low-temperature operation. Finally, based on the current review, it can be suggested that cold plasma is an effective disinfectant technology for inactivating pathogenic microorganisms, and its non-thermal and environmentally friendly nature is an added advantage over traditional processing technologies.

Dash et al. [73] discussed the application of cold plasma for raw milk with different combinations of processing parameters. These authors defined the parameters shown in Table 7 as optimal for the milk process.

Table 7.

Optimized condition parameters used in cold plasma for raw milk.

Cold plasma technology presents a promising non-thermal alternative for microbial inactivation in the dairy industry, thereby preserving the nutritional and sensory qualities of dairy products. While it shows potential in enhancing the functional properties of dairy proteins and maintaining the quality of whey beverages, concerns regarding lipid oxidation must be addressed. Further research is needed to optimize treatment parameters and mitigate the oxidative effects, ensuring the industrial viability of cold plasma in milk for dairy processing.

2.9. Pulsed Light

Pulsed light treatment is a non-thermal technology used to inactivate microorganisms in milk. This treatment is gaining attention as an alternative to traditional thermal pasteurization due to its potential to preserve milk’s nutritional and sensory qualities while ensuring microbial safety. Miller et al. [74] used the pulsed light treatment with effectiveness in inactivation of Escherichia coli in cow milk, with higher reductions observed in milk with lower total solids content. These authors stated that the milk’s fat content and total solids influence the effectiveness of pulsed light treatment. In this study [74], higher fat content and solids can reduce the efficacy of microbial inactivation due to light absorption and scattering.

On the other hand, pulsed UV light can achieve significant inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus in milk, with reductions varying based on treatment conditions, such as distance from the light source and treatment time [75]. In goat milk, pulsed light treatment resulted in a 6-log reduction of E. coli without significant changes in physical or compositional parameters, although some aromatic changes were observed [76]. The combined effects of pulsed light treatment were verified [77]. Innocente et al. [77] observed that pulsed light treatment can cause both photochemical and photothermal effects, contributing to microbial inactivation. For instance, high fluence pulsed light treatment resulted in a 3.2 log reduction in total microbial count and significant inactivation of alkaline phosphatase in raw milk [77].

Elmnasser et al. [78] highlighted that pulsed light can induce conformational changes in milk proteins, such as β-lactoglobulin, but does not significantly alter amino acid composition or cause lipid oxidation, indicating minimal impact on nutritional quality. Orłowska et al. [79] cited that continuous and pulsed UV light treatments have been shown to maintain milk quality parameters, such as pH and vitamin C content, with minimal deterioration compared to traditional UV lamps. These authors cited UV fluence levels of 5 mJ/cm2 and 10 mJ/cm2 to measure the effects on milk quality. In Figure 12, the operating diagram of a pulse light treatment for milk is accessible.

Figure 12.

Representation of the basic configuration for pulsed light treatment.

It is noteworthy that pulsed light treatment is a promising non-thermal method for enhancing the microbial safety of milk while preserving its quality. Its effectiveness can vary based on milk composition and treatment conditions. Combining pulsed light with other treatments, such as thermal processes, can enhance its efficacy and improve the quality of milk products, including yogurt. Overall, pulsed light treatment offers a viable alternative to traditional pasteurization methods, with potential applications in the dairy industry for producing safer and higher-quality milk products.