Abstract

Biomass gasification, a thermochemical conversion process that turns organic feedstocks like wood, agricultural residues, and solid waste into a combustible gas known as synthesis gas (syngas), is the focus of this study. In this study, Aspen Plus® as a process simulation platform to optimize key operational parameters for the gasification of sugarcane bagasse was employed. The results are promising, with an equivalence ratio (ER) of 0.25 and a carbon conversion efficiency (XC) of 62.44% achieved, indicating the potential for the produced syngas to be compatible with injection into natural gas distribution networks. The lower heating value (LHV) of the syngas was determined to be 3.93 MJ·kg−1, with an overall gasification efficiency of 49.85%. The simulation results showed strong agreement with experimental data, validating the modeling approach as a reliable predictive tool for biomass gasification systems and reducing unnecessary resource consumption. This validation instills trust and confidence in the reliability of our findings.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, as developed countries have undergone industrialization, energy demand has increased significantly, leading to higher greenhouse gas emissions primarily due to the combustion of fossil fuels [1]. It is widely recognized that the use of fossil fuels is the primary contributor to Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and global warming. There is an urgent need to achieve carbon neutrality by mid-century, prompting substantial efforts to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy sources [2]. As of 2021, renewable energy accounted for only 28.5% of the total energy supply, with bioenergy comprising 8.23% of the renewable energy mix [3].

Biomass is considered a promising alternative to fossil fuels due to its abundance, renewability, and low carbon emissions [4]. It offers distinct advantages over other renewable energy sources, including lower dependence on specific geographic locations and climatic conditions, as well as ease of transport and storage [5]. By 2030, biomass is expected to replace approximately 30% of petroleum use in the United States and play a key role in the European Union’s target of achieving 27% sustainable energy [6].

The conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into molecular hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrocarbons (CnHm) compounds is of critical importance [7]. Lignocellulosic biomass can be transformed into chemicals and biofuels via thermochemical or biochemical pathways, with the thermochemical route standing out as a desirable option [8]. By 2030, biomass is expected to replace approximately 30% of petroleum consumption in the United States and play a critical role in the European Union’s goal of achieving 27% sustainable energy [6]. The conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into H2, CO, and CnHm compounds is of fundamental importance [7]. Biomass is composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, starch, proteins, and other organic and inorganic components [9]. The high oxygen content in these materials contributes to the presence of oxygenated organic compounds and water in the produced gas, which significantly affects its properties and potential applications in downstream processes [2]. Sugarcane bagasse (SCB) is a type of lignocellulosic biomass that presents a promising solution to mitigate the energy crisis. Brazil is the world’s leading producer of SCB, generating 31.16 × 103 metric tons in 2020, followed by India and China [10].

Lignocellulosic biomass can be transformed into chemicals and biofuels through thermochemical or biochemical processes, with the thermochemical pathway representing a particularly attractive alternative [8]. The most common thermochemical processes for converting lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels include pyrolysis, gasification, combustion, and liquefaction [11]. Among these, gasification—a thermochemical conversion process—has shown promising results by efficiently converting carbonaceous feedstocks into combustible gases [12]. This process employs gasifying agents such as oxygen-enriched air and steam to produce high-quality synthesis gas [13].

The literature identifies multiple applications for synthesis gas, including methanol production systems, synthetic natural gas generation, industrial heat applications, and power generation, among others [14]. Gasification involves the conversion of biomass into a combustible gas (syngas) through partial oxidation at temperatures approaching 900 °C [15]. This gas can be utilized for energy generation or the production of high-value-added chemicals [16]. However, this approach faces several challenges, such as syngas dilution, unwanted CO2 production, and tar formation [17]. In terms of Aspen Plus® V12 applications for biomass gasification, Sakheta et al. [18] developed a hybrid approach by combining Aspen Plus® simulations with machine learning algorithms to improve the prediction of gasification outputs. Their study highlighted that conventional equilibrium-based Aspen Plus® models may lead to inaccuracies, but the integration of experimental data through six machine learning algorithms significantly enhanced prediction accuracy and provided more reliable insights into process feasibility. This work underlines the importance of combining process simulation with data-driven methods to strengthen the commercialization potential of sugarcane residue gasification. For instance, simulations using a steam–oxygen-blown bubbling fluidized bed via a Gibbs equilibrium model revealed how gasification temperature, steam-to-biomass ratio, pressure, and moisture content significantly influence syngas composition and efficiency indicators, proving the process’s feasibility for clean energy production [19]. Further optimization work demonstrated that integrating bagasse gasification with heat recovery in a sugar mill context can nearly double the electrical output (up to ~1.16 kWh per kg of bagasse at 10% moisture) compared to direct combustion (~0.57 kWh·kg−1) [20]. Collectively, these investigations affirm that Aspen Plus® models—spanning thermodynamic equilibrium methods, diverse reactor configurations, and process integration—offer valuable insights into improving syngas yield, quality, and overall energy efficiency in bagasse gasification.

The Aspen Plus® simulator has been extensively employed to model biomass gasification under various operating conditions. Lan et al. [21] used Aspen Plus® to simulate biomass gasification integrated with a gas turbine model, evaluating key turbine parameters for power generation. Gu et al. [22] investigated the impact of gasifying agents on energy efficiency during biomass gasification. They also analyzed the influence of equivalence ratio (ER) and gasification temperature on syngas composition, aiming to identify the optimal process parameters for producing high-quality syngas.

Although previous studies have made important contributions by optimizing operating conditions, integrating bagasse gasification with heat recovery, or even coupling Aspen Plus® with machine learning algorithms to improve predictive accuracy, they have not directly addressed the practical determination of air flow requirements for sugarcane bagasse gasification. Most of the existing literature emphasizes syngas composition, efficiency indicators, or process integration, but the fundamental issue of quantifying the optimal air input—critical for achieving stable operation and reliable performance—remains underexplored. The novelty of the present study lies in bridging this gap by developing an Aspen Plus® model that not only simulates the gasification process but also systematically evaluates the required air flow along with key performance indicators such as the equivalence ratio (ER), carbon conversion (XC), and cold gas efficiency (η). This contribution advances the current state of knowledge by providing a process-oriented framework with direct applicability to industrial-scale sugarcane bagasse gasification systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock and Its Characterization

The main physicochemical characteristics of the raw biomass employed in this study were reported in a previous work by Rodríguez Machín et al. [23], where the proximate and ultimate analyses of sugarcane bagasse were thoroughly discussed. Therefore, the characterization of the feedstock was not repeated here, but the results obtained in Rodríguez Machín’s work were used as a reference baseline to ensure consistency and reproducibility of the experimental conditions.

2.2. Description of the Method Used

The simulation process for biomass gasification was modeled using a comprehensive quasi-equilibrium approach. This approach enables the quantification of deviations from thermodynamic equilibrium and provides a broader perspective, as it is not constrained by the resistances that affect gasification kinetics [24]. The model includes the following stages, ensuring a thorough understanding of the process:

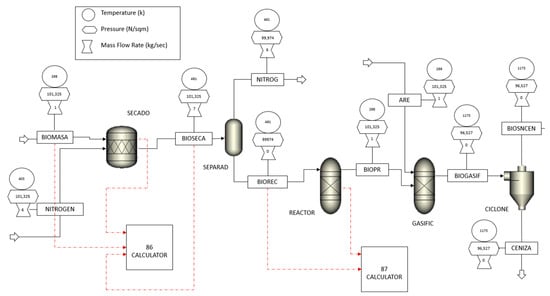

2.2.1. Biomass Drying

Two Aspen blocks were used to simulate the drying process: a stoichiometric reactor, SECADO, and a flash separator, SEPARAD, as shown in Figure 1. The biomass enters under atmospheric conditions (25 °C and 1 atm) with a moisture content of 25% (wet base mass). Drying is performed with a nitrogen stream at 130 °C and 1 atm pressure. The moisture content is reduced to 10%. Although drying is not considered a chemical reaction, this approach allows for the conversion of a fraction of the non-conventional component into water. Aspen Plus®, a widely used process simulation software, calculates the heat required to vaporize this water [15]. A FORTRAN block is used to solve the mass balance in the process. The conversion is calculated by comparing the mass of water entering the system with the mass of water exiting, as shown in Equations (1) and (2).

where H2Oout refers to the final mass (or percentage) of water remaining in the biomass after the drying process, H2Oin refers to the initial mass (or percentage) of water entering the drying system with the biomass, and CONV represents the conversion factor, which quantifies the proportion of water removed during drying. It is calculated by comparing the amount of water initially present to the amount remaining, normalized to the dry basis.

H2Oout = 10

Figure 1.

General flow diagram of sugarcane bagasse gasification modeled in Aspen Plus®.

2.2.2. Syngas Production

The biomass gasification process is carried out in the performance and Gibbs reactors (REACTOR and GASIFIC), as shown in Figure 1. This reaction is near equilibrium at temperatures close to 900 °C [21].

For the modeling, the following assumptions are established [25]:

- The gasifier is in a steady state;

- Operational parameters do not change over time;

- There is no pressure drop in the gasifier;

- Ash in the biomass is inert and not involved in the gasification process;

- The temperature of the biomass particles is uniform;

- All reactions are fast and reach equilibrium;

- The volatile products after biomass devolatilization include H2, O2, CO, CO2, CH4, and H2O.

Biomass Equation (3) and ash (Ash) Equation (4) are the unconventional components.

Biomass is decomposed into elements according to the Fortran code, for carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen as per Equations (5)–(8), respectively.

2.2.3. Equivalence Ratio (ER)

When dry biomass is represented as CaHbOcNdSe from the ultimate analysis, the stoichiometric oxygen requirement per kmol of fuel is expressed as:

The stoichiometric air mass flow rate is then obtained as:

where = 31.999 kg·kmol−1 and ≈ 0.232, corresponding to the mass fraction of oxygen in air. This methodology, based on the elemental composition (CaHbOcNdSe) obtained from ultimate analysis, is widely reported in the literature [26].

Once the stoichiometric air requirement is determined, the actual air flow rate for gasification can be expressed as:

The equivalence ratio (ER) [22] plays a fundamental role in biomass gasification, having a direct effect on the composition of the produced gas. It is defined as the ratio of the amount of air supplied to the gasifier to the stoichiometric amount of air [27]. The equivalence ratio indicates how fuel-rich or fuel-lean the gasification process is. Values of ER below 1 indicate a sub-stoichiometric (oxygen-deficient) environment typical in gasification, whereas values close to or above 1 would correspond to combustion rather than gasification. Reported optimal values for air-blown biomass gasification are typically within ER ≈ 0.2–0.3 [28,29]. Conversely, if the actual air flow is known, the equivalence ratio (ER) can be calculated as:

where ṁ_air_real: Actual mass flow rate of air supplied to the gasifier (kg/s). This represents the real amount of air introduced during the gasification process. ṁ_air_st: Stoichiometric mass flow rate of air required for complete combustion of the biomass (kg/s). It represents the theoretical amount of air needed to oxidize all the biomass.

2.2.4. Carbon Conversion

In Equation (13), the carbon conversion efficiency (XC) quantifies the effectiveness of the gasification process in converting the carbon content of the biomass into carbon present in the produced syngas [30].

where XC: Carbon conversion efficiency (dimensionless or %). It represents the fraction of carbon in the biomass that is successfully converted into gaseous products. C_syngas: Amount of carbon found in the syngas (usually expressed in mass or molar units, e.g., kg or mol of C). This includes the carbon contained in gaseous species such as CO, CO2, CH4, and other hydrocarbons. C_biomass: Total amount of carbon initially present in the biomass feedstock (kg or mol of C). It represents the theoretical maximum amount of carbon that can be converted.

A higher value of XC indicates a more efficient gasification process in terms of carbon utilization, with values approaching 1 (or 100%) reflecting near-complete conversion of biomass carbon into syngas carbon.

2.2.5. Utilization of Syngas

The presented simulation proposes, under combustion conditions, the utilization of syngas in an energy production system through a steam turbine.

3. Results

3.1. Biomass Characterization

Biomass is defined as a non-conventional solid and is characterized by standard practices for proximate analysis of coal and elemental analysis. The results of these tests for the characterization of sugarcane bagasse are summarized in Table 1. Similar results for the proximate and elemental analysis of sugarcane bagasse were reported by Kombe et al. [31]. The sugarcane bagasse analyzed in this study exhibits a volatile matter (VM) content of 18.3%, a fixed carbon (FC) content of 79.8%, and ash content of 1.9%. These characteristics are consistent with the fibrous and lignocellulosic nature of sugarcane bagasse, which is widely reported in the literature as a promising biomass for thermochemical conversion processes such as gasification and pyrolysis [32]. The high fixed carbon content suggests a significant potential for char production. In contrast, the relatively low ash content is advantageous as it minimizes operational issues related to slagging and fouling during thermal conversion [33]. The ultimate analysis shows that the carbon (C) content is 44.1%, hydrogen (H) is 6.0%, nitrogen (N) is 0.2%, and oxygen (O) is 47.8%, with negligible chlorine and sulfur content. The high oxygen content is characteristic of lignocellulosic residues and reflects the presence of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin structures [34]. Moreover, the low nitrogen content indicates a reduced potential for nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions, which is reassuring for its environmental impact and favorable for cleaner energy production [35]. The proximate and ultimate analysis results presented in Table 1 are reported on a dry basis. This approach was adopted to eliminate the influence of moisture content, which can vary significantly depending on storage and handling conditions, and to enable a more accurate comparison with results reported in the literature. As highlighted by Basu [36], reporting biomass characterization on a dry basis is a standard practice in gasification and pyrolysis studies, since it ensures consistency and reproducibility of data used in process modeling and simulation. In this analysis, the catalytic effect of potassium was not considered due to its minimal presence in the biomass feedstock. Studies have shown that potassium can act as a catalyst in biomass gasification, enhancing the conversion efficiency and influencing the formation of tar and soot [37]. However, the concentration of potassium in our biomass sample was negligible, rendering its catalytic impact insignificant and justifying its exclusion from the model. Additionally, the absence of specific kinetic data for potassium-catalyzed reactions in our dataset further supports this decision [38].

Table 1.

Proximate and ultimate analysis of sugarcane bagasse (dry basis) [23,39].

3.2. Gasification Conditions

3.2.1. Required Air Flow

The process temperature, a key influencer, directly shapes the heating value of the syngas and, consequently, the overall gasification efficiency [40]. For an input of 1.2 kg·s−1 of biomass (BIOMASA stream in Aspen Plus®), the introduction of an air flow of 1.473 kg·s−1 into the gasification reactor (GASIFIC in Aspen Plus®) is a crucial step. A flow of 1 kg·s−1 comes from the performance reactor (REACTOR). This results in syngas with the following molar fractions: H2 = 0.1838, N2 = 0.3948, H2O = 0.1598, CO = 0.1546, CO2 = 0.1068, CH4 = 0.0000038, as reported in the BIOGASIF stream results from Aspen Plus®.

3.2.2. Equivalence Ratio (ER)

The ER, as detailed in Table 2, is a key parameter. The value determined in this study for the ER (0.25) falls within the typical range of values for biomass gasification processes, as reported by Rudra et al. [41]. This consistency underscores the reliability of our findings.

Table 2.

Equivalence Ratio (ER).

3.2.3. Carbon Conversion

The carbon conversion efficiency (XC) is shown in Table 3. The carbon conversion efficiency value obtained in the process was 62.44%, a value close to the 66.81% reported by Tremel A. et al. [42]. This value can be improved to 73.9% if an integrated system is considered. Under these conditions, the produced syngas not only meets but exceeds quality requirements for injection into a natural gas network, providing a practical application for the research findings.

Table 3.

Carbon conversion efficiency (XC).

Increasing the gasification temperature improves the gasification rate, which in turn increases the carbon conversion efficiency [30]. On the other hand, a lower moisture content in the biomass also increases the carbon conversion efficiency [43].

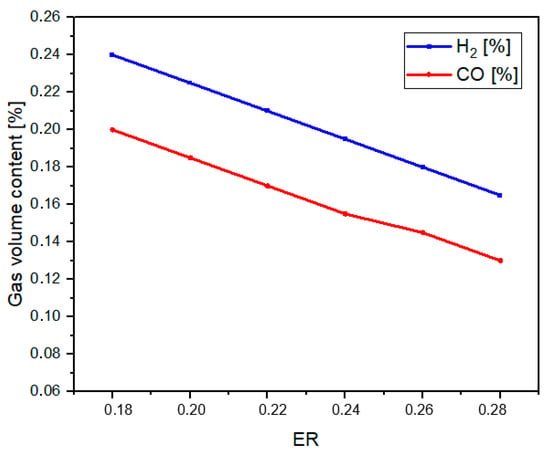

3.2.4. Effect of the Equivalence Factor

Figure 2 demonstrates the crucial role of the ER in determining the composition of H2 and CO in the Syngas. The initial increase in the amount of carbon monoxide and hydrogen in Syngas is a direct result of higher biomass conversion. However, after a specific limit, the syngas production decreases due to the complete combustion of the feed [44]. As the ER increases, more oxidation reactions occur, leading to a decrease in H2, CO, and methane (CH4) content, and an increase in CO2 content due to an increase in gasifier feed [22]. In this study, the main components of syngas produced from sugarcane bagasse gasification were identified as CO, H2, CH4, CO2, C2H4, C3H6, and N2. These findings are consistent with previous reports in the literature, which indicate that syngas typically contains H2, CO, CO2, CH4, and minor higher hydrocarbons (C2+ hydrocarbons) [45]. The oxygen content in the syngas was observed to be very low (~0.2%), which is characteristic of partial biomass gasification where the gasifying agent (e.g., air or steam) limits complete carbon oxidation and favors CO and H2 production [46].

Figure 2.

Effect of ER on H2 and CO.

3.2.5. Gasifier Efficiency

Table 4 showcases the gasification efficiency results, a pivotal aspect of our study. These results, based on cold gas and calorific value for both biomass and syngas, are of paramount importance. The upper calorific value, a crucial parameter, was found to be 17.47 MJ·kg−1, a figure in line with the literature [39].

Table 4.

Gasification Efficiency.

The high oxygen content present in the biomass (47.8%) causes the presence of oxygenated organic compounds and water in the syngas produced, and this also makes its calorific value low (LHVsyngas = 3.93 MJ·kg−1) [31]. For this reason, the gasification efficiency is only 49.85%, a value that we found to be lower than that reported by Arteaga-Pérez et al. [24], which was 58%. This comparison with existing literature provides a valuable context for our findings.

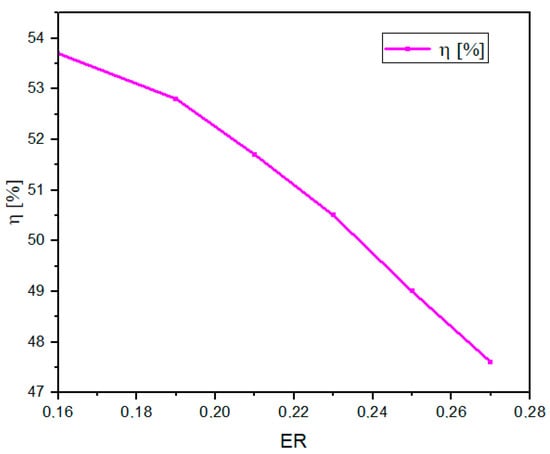

3.2.6. Efficiency vs. Equivalence Factor

As the ER increases, the LHV in the produced gas decreases (Figure 3). Therefore, the efficiency of the system decreases, since the higher the ER, the lower the H2 and CO content (as seen in Section 3.2.4.), which are the components that directly influence the LHV [47].

Figure 3.

Effect of ER on η.

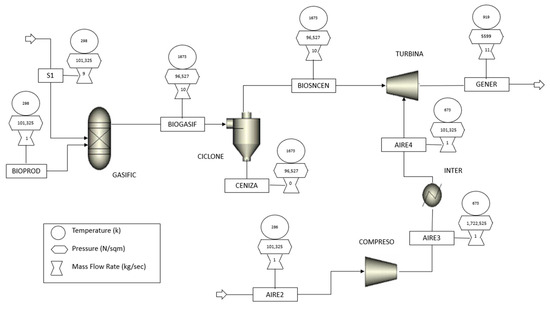

3.3. Combustion and Energy Recovery

As mentioned above, the synthesis gas utilization options are not just alternatives, but crucial components of our energy landscape. These options, such as methanol production systems, synthetic natural gas (SNG) production, heat production for industrial uses, and electric power generation, among others, play a significant role. Figure 4 presents a system for electricity generation through a turbine, based on the scheme proposed by Lan et al. [21]. This system, which does not include the cleaning system for the synthesis gas, nor the interconnection of the air to the reactor inlet stream, is a testament to the importance and potential of these options.

Figure 4.

Sugarcane bagasse combustion flow diagram in Aspen Plus®.

Table 5 presents the simulation conditions for the energy recovery subprocess, specifically for sugar cane bagasse combustion. The values reported were not selected arbitrarily but were derived from a combination of simulation outputs and literature-based design standards, ensuring both consistency and reliability in the model. Key parameters such as the turbine’s output power (16.70 MW), biomass flow rate (1.20 kg·s−1), and combustion/air ratios were obtained directly from the Aspen Plus® GENER stream report. These values underpin the energy yield of 13.91 MJ·kg−1 biomass and reflect the combustion behavior of sugarcane bagasse in the simulation environment. Operational parameters for the turbine and compressor—such as the combustion temperature (1400 °C), pressure ratios (17 for both compressor and turbine), turbine inlet/outlet temperatures, exhaust temperatures, and isentropic efficiencies (0.90 for turbine, 0.89 for compressor)—were chosen based on typical ranges reported for gas turbine systems under similar operating conditions. A study by Prabowo et al. [48] demonstrated that turbine efficiency varies with pressure ratio and turbine inlet temperatures comparable to ours (e.g., ≈1400 °C), illustrating the sensitivity of performance to these parameters. Another study on integrated biomass systems reports isentropic efficiencies ranging from 80 to 90% for compressors and turbines, reinforcing the validity of the values used in our simulation [49].

Table 5.

Conditions for the effective use of syngas.

The turbine’s output power is 16.70 MW (GENER stream report of Aspen Plus®), with an initial flow rate of 1.20 kg·s−1, resulting in an energy yield of 13.91 MJ·kg−1 biomass. The simulation results for the turbine, which closely match those obtained by Lan et al. for an M701F turbine, underscore the reliability of our simulation method [21]. This validation should instill confidence in the audience. However, when compared with the work of Gómez-Barea [50] discrepancies can be observed in the CO and H2 concentrations. These differences arise primarily from the type of gasifying agent (air versus steam), the equivalence ratio applied, and the reactor configuration, all of which strongly influence gas composition [51]. Likewise, Prabowo et al. [48] reported higher CH4 contents in their Aspen Plus® simulations of biomass gasification, which can be attributed to the different feedstocks considered and variations in devolatilization kinetics. In our case, sugarcane bagasse was used as feedstock, whose higher oxygen content compared to woody biomass leads to different product gas distributions.

Therefore, the discrepancies observed are not due to methodological limitations but to the inherent variability of biomass feedstocks and the diversity of gasification conditions applied in different studies.

4. Future Work

To strengthen and extend the scope of this research, the following future directions are proposed:

- ✓

- Experimental Validation: At this stage, the study was limited to process simulation, and therefore experimental validation was beyond its scope. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of conducting dedicated experiments to complement the simulations, and future work will focus on designing laboratory-scale tests to generate experimental data for direct validation.

- ✓

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Apply advanced optimization techniques—such as genetic algorithms or NSGA-II—to simultaneously optimize economic, environmental, and performance indicators of the gasification system.

- ✓

- Co-Gasification Studies: Investigate the co-gasification of sugarcane bagasse with other agricultural or forestry residues to improve syngas quality and diversify biomass feedstock availability.

- ✓

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Integrate life cycle assessment methodologies to evaluate the overall environmental impact of the gasification process, from feedstock cultivation to syngas utilization.

- ✓

- Integration with Carbon Capture Technologies: Explore the coupling of gasification with carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems, enabling a potential net-zero or even negative carbon footprint for biomass-to-energy conversion.

- ✓

- Work on Solid Residues: Future studies will extend the current research by evaluating the solid residues generated during biomass gasification, such as biochar. This evaluation was focused on quantifying the yields of these residues and analyzing their potential applications, including soil amendment and pollutant adsorption. Incorporating such analyses will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the overall efficiency and sustainability of the gasification process.

- ✓

- Targeted Syngas Applications: Simulate specific downstream uses of syngas, including methanol synthesis, ammonia production, and combined heat and power (CHP) generation, under different operational scenarios and energy demand profiles.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that the simulation of sugarcane bagasse gasification using Aspen Plus® is an effective and reliable approach for optimizing key operational parameters in thermochemical conversion systems. The use of a Gibbs reactor allowed the simplification of complex gasification reactions by predicting equilibrium compositions based on the minimization of Gibbs free energy, thus approximating real thermodynamic behavior without the need for extensive experimental data.

The obtained equivalence ratio (ER) of 0.25 and carbon conversion efficiency (XC) of 62.44% demonstrate the potential of the model to support the design and evaluation of biomass gasification processes. Moreover, the syngas produced exhibited a lower heating value (LHV) of 3.93 MJ·kg−1 and a cold gas efficiency of 49.85%, confirming its suitability for integration into energy production systems or natural gas grids, particularly when paired with gas cleaning stages.

The close agreement between simulated results and data reported in the literature validates the accuracy and predictive capacity of the model, reinforcing its relevance as a tool for decision-making in biomass valorization strategies. This research contributes meaningfully to the development of sustainable energy systems by demonstrating how process simulation can reduce design time, experimental costs, and resource consumption, while accelerating the deployment of renewable energy technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.-S. and D.V.-V.; methodology, D.V.-V.; software, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; validation, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; formal analysis, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; investigation, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; resources, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; data curation, D.V.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; writing—review and editing, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; visualization, D.V.-V.; supervision, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; project administration, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V.; funding acquisition, C.A.-S., S.R.-G., L.T.-S. and D.V.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

To the Escuela Politécnica Nacional EPN-Ecuador, with its research lines: Sustainable Manufacturing in Manufacturing Processes and Mitigation of Vibrations, and Energy Efficiency in Automotive and Aeronautical Transportation Systems, for the support provided in the development of this work. Special thanks to the “Escuela de Hábitat, Infraestructura y Creatividad” and the “Dirección de Investigación” of “Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Sede Ambato” for their support in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ER | Equivalence ratio |

| CONV | Conversion factor |

| FC | Fixed carbon |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| MC | moisture content |

| VM | Volatile matter |

| XC | Carbon conversion efficiency |

References

- Meinshausen, M.; Lewis, J.; McGlade, C.; Gütschow, J.; Nicholls, Z.; Burdon, R.; Cozzi, L.; Hackmann, B. Realization of Paris Agreement pledges may limit warming just below 2 °C. Nature 2022, 604, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Vásconez, D.; Orejuela-Escobar, L.; Valarezo-Garcés, A.; Guerrero, V.H.; Tipanluisa-Sarchi, L.; Alejandro-Martín, S. Biomass Valorization through Catalytic Pyrolysis Using Metal-Impregnated Natural Zeolites: From Waste to Resources. Polymers 2024, 16, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhao, W.; Xiong, Q.; Li, B. Microwave-assisted chemical looping gasification of sugarcane bagasse biomass using Fe3O4 as oxygen carrier for H2/CO-rich syngas production. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. China’s goal of achieving carbon neutrality before 2060: Experts explain how. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwac115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orejuela-Escobar, L.; Venegas-Vásconez, D.; Méndez, M.Á. Opportunities of artificial intelligence in valorisation of biodiversity, biomass and bioresidues—Towards advanced bio-economy, circular engineering, and sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Energy Environ. Res. 2024, 13, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafnomilis, I.; Hoefnagels, R.; Pratama, Y.W.; Schott, D.L.; Lodewijks, G.; Junginger, M. Review of solid and liquid biofuel demand and supply in Northwest Europe towards 2030—A comparison of national and regional projections. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Du, J.; Chen, J. Oxygen-enriched air gasification of biomass materials for high-quality syngas production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 199, 111628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Bing, L.; Xi, F.; Wang, F.; Dong, J.; Wang, S.; Lin, G.; Yin, Y.; et al. Benefit analysis of multi-approach biomass energy utilization toward carbon neutrality. Innovation 2023, 4, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Vásconez, D.; Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Aguayo, M.G.; Romero-Carrillo, R.; Guerrero, V.H.; Tipanluisa-Sarchi, L.; Alejandro-Martín, S. Analytical Pyrolysis of Pinus radiata and Eucalyptus globulus: Effects of Microwave Pretreatment on Pyrolytic Vapours Composition. Polymers 2023, 15, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Anu; Kumar Tiwari, S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, D.; Kumar, S.; Manisha; Malik, V.; Singh, B. Sugarcane bagasse: An important lignocellulosic substrate for production of enzymes and biofuels. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 6111–6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Moghaddam, E.M.; Liu, W.; He, C.; Konttinen, J. Biomass chemical looping gasification for high-quality syngas: A critical review and technological outlooks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 268, 116020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamsidhiphongsa, N.; Limleamthong, P.; Prasertcharoensuk, P.; Arpornwichanop, A. A review on computational fluid dynamics modeling of fixed-bed biomass gasifiers: Recent advances and design analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 130, 654–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, H.; Sadio Sidibe, S.D.; Richardson, Y. Advancing small-scale biomass gasification (10–200 kW) for energy access: Syngas purification, system modeling and the role of artificial intelligence-A review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, M.; Santamaria, L.; Lopez, G.; Alvarez, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Bi, X.; Olazar, M. A comprehensive review of primary strategies for tar removal in biomass gasification. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Gómez-Cápiro, O.; Karelovic, A.; Jiménez, R. A modelling approach to the techno-economics of Biomass-to-SNG/Methanol systems: Standalone vs Integrated topologies. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 286, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Gamero, M.; Argudo-Santamaria, J.; Valverde, J.L.; Sánchez, P.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Three integrated process simulation using aspen plus®: Pine gasification, syngas cleaning and methanol synthesis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tao, J.; Yan, B.; Jiao, L.; Chen, G.; Hu, J. Review of microwave-based treatments of biomass gasification tar. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakheta, A.; Raj, T.; Nayak, R.; O’Hara, I.; Ramirez, J. Improved prediction of biomass gasification models through machine learning. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 191, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, I.L.; Miranda, N.T.; Maciel Filho, R.; Wolf Maciel, M.R. Sugarcane bagasse gasification: Thermodynamic modeling and analysis of operating effects in a steam-oxygen-blown fluidized bed using aspen plustm. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 65, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umang, K.; Pratham, A. Efficiency Improvement in Sugar Mills through Bagasse Gasification. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 88, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Chen, G.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, B. Biomass gasification-gas turbine combustion for power generation system model based on ASPEN PLUS. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Tang, Y.; Yao, J.; Chen, F. Study on biomass gasification under various operating conditions. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Machín, L.; Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Pérez-Bermúdez, R.A.; Casas-Ledón, Y.; Prins, W.; Ronsse, F. Effect of citric acid leaching on the demineralization and thermal degradation behavior of sugarcane trash and bagasse. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 108, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Casas-Ledón, Y.; Prins, W.; Radovic, L. Thermodynamic predictions of performance of a bagasse integrated gasification combined cycle under quasi-equilibrium conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 258, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, F.; Özveren, U. A deep learning approach for prediction of syngas lower heating value from CFB gasifier in Aspen plus®. Energy 2020, 209, 118457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, M.A.; Adesina, O.A.; Odejobi, O.J.; Sonibare, J.A. Theoretical Air Requirement and Combustion Flue Gases Analysis for Indigenous Biomass Combustion. J. Niger. Soc. Phys. Sci. 2022, 4, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdiwansyah; Gani, A.; Zaki, M.; Mamat, R.; Nizar, M.; Rosdi, S.M.; Yana, S.; Sarjono, R.E. Analysis of technological developments and potential of biomass gasification as a viable industrial process: A review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, M.; Raheem, A.; Wang, F.; Wei, J.; Xu, D.; Song, X.; Bao, W.; Huang, A.; Zhang, S.; et al. Syngas Production from Biomass Gasification: Influences of Feedstock Properties, Reactor Type, and Reaction Parameters. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31620–31631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.S.M.; Ghani, W.A.W.A.K.; Tan, H.B.; Ng, D.K.S. Prediction and optimisation of syngas production from air gasification of Napier grass via stoichiometric equilibrium model. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 10, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra Paul, T.; Nath, H.; Chauhan, V.; Sahoo, A. Gasification studies of high ash Indian coals using Aspen plus simulation. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 6149–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombe, E.Y.; Lang’at, N.; Njogu, P.; Malessa, R.; Weber, C.-T.; Njoka, F.; Krause, U. Numerical investigation of sugarcane bagasse gasification using Aspen Plus and response surface methodology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, R.; Rezaei, M.; Samadi, S.H. Sugarcane bagasse gasification in a downdraft fixed-bed gasifier: Optimization of operation conditions. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyatno, S.; Ghazidin, H.; Prismantoko, A.; Karuana, F.; Kuswa, F.M.; Dwiratna, B.; Prabowo, P.; Darmawan, A.; Syafri, E.; Sari, A.P.; et al. Evaluation of combustion characteristics and ash-related issues during co-firing of acacia and mahogany wood biomass fuels with coal. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 196, 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocha, C.K.R.; Chia, W.Y.; Silvanir; Kurniawan, T.A.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W. Thermochemical conversion of different biomass feedstocks into hydrogen for power plant electricity generation. Fuel 2023, 340, 127472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Szabó, M.; Ceci, P.; Avino, P. Biomass Energy and Biofuels: Perspective, Potentials, and Challenges in the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification, Pyrolysis and Torrefaction: Practical Design and Theory, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-12-396488-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsson, P.; Cantatore, V.; Seemann, M.; Tam, P.L.; Panas, I. Role of potassium in the enhancement of the catalytic activity of calcium oxide towards tar reduction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 229, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Oller, A.; Furusjö, E.; Umeki, K. On the role of potassium as a tar and soot inhibitor in biomass gasification. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Machín, L.; Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Pala, M.; Herregods-Van De Pontseele, K.; Pérez-Bermúdez, R.A.; Feys, J.; Prins, W.; Ronsse, F. Influence of citric acid leaching on the yield and quality of pyrolytic bio-oils from sugarcane residues. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 137, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.; Kempka, T. Synthesis Gas Composition Prediction for Underground Coal Gasification Using a Thermochemical Equilibrium Modeling Approach. Energies 2020, 13, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttin, K.W.; Yu, H.; Yang, M.; Ding, L.; Chen, X.; Yu, G.; Wang, F. Experimental and numerical modeling of carbonized biomass gasification: A critical review. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremel, A.; Gaderer, M.; Spliethoff, H. Small-scale production of synthetic natural gas by allothermal biomass gasification: Small-scale production of SNG. Int. J. Energy Res. 2013, 37, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.; Kwong, P.; Ahmad, E.; Nigam, K.D.P. Clean syngas from small commercial biomass gasifiers; a review of gasifier development, recent advances and performance evaluation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 21087–21111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, N.; Ashraf, A.; Naveed, S.; Malik, A. Simulation of hybrid biomass gasification using Aspen plus: A comparative performance analysis for food, municipal solid and poultry waste. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3962–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segurado, R.; Pereira, S.; Correia, D.; Costa, M. Techno-economic analysis of a trigeneration system based on biomass gasification. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A. CO2 capture and separation technologies for end-of-pipe applications—A review. Energy 2010, 35, 2610–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.; Monteiro, E.; Tabet, F.; Rouboa, A. Numerical investigation of optimum operating conditions for syngas and hydrogen production from biomass gasification using Aspen Plus. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, B.; Aziz, M.; Umeki, K.; Susanto, H.; Yan, M.; Yoshikawa, K. CO2-recycling biomass gasification system for highly efficient and carbon-negative power generation. Appl. Energy 2015, 158, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, H. Thermodynamics Analysis of a Novel Compressed Air Energy Storage System Combined with Solid Oxide Fuel Cell–Micro Gas Turbine and Using Low-Grade Waste Heat as Heat Source. Energies 2023, 16, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Barea, A.; Leckner, B. Modeling of biomass gasification in fluidized bed. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 444–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Model of co-gasification of coal and biomass in jetting fluidized bed by Aspen Plus: Contributive ratio. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 128091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).