Abstract

This study implemented a bidirectional artificial neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) to solve the problem of system resilience in synchronized and islanded grid mode/operation (during normal operation and in the event of a catastrophic disaster, respectively). Included in this setup are photovoltaics, wind turbines, batteries, and smart load management. Solar panels, wind turbines, and battery-charging supercapacitors are just a few of the sustainable energy sources ANFIS coordinates. The first step in the process was the development of a mode-specific control algorithm to address the system’s current behavior. Relative ANFIS will take over to greatly boost resilience during times of crisis, power savings, and routine operations. A bidirectional converter connects the battery in order to keep the DC link stable and allow energy displacement due to changes in generation and consumption. When combined with the ANFIS algorithm, PV can be used to meet precise power needs. This means it can safeguard the battery from extreme conditions such as overcharging or discharging. The wind system is optimized for an island environment and will perform as designed. The efficiency of the system and the life of the batteries both improve. Improvements to the inverter’s functionality can be attributed to the use of synchronous reference frame transformation for control. Based on the available solar power, wind power, and system state of charge (SOC), the anticipated fuzzy rule-based ANFIS will take over. Furthermore, the synchronized grid was compared to ANFIS. The study uses MATLAB/Simulink to demonstrate the robustness of the system under test.

Keywords:

microgrid; bidirectional ANFIS; adaptive neural network; resilience; fuzzy; energy storage 1. Introduction

Nowadays, because of the fundamental importance of systems such as energy networks, telecommunications and transportation networks, and banking and financial exchange networks [1], microgrid management has long been regarded as a crucial factor in the design of such infrastructures.

To make sure a system can keep running even if some hardware fails, redundancy is implemented [2]. Medium-voltage power distribution feeders are typically supplied by two parallel transformers, with their capacities calibrated so that each transformer can provide the loads of the feeders [3]. Clients do not have to deal with load shedding in the event of an outage or maintenance. Large power systems with lots of equipment are more likely to experience a partial outage. On top of that, the system’s operational condition is dynamic and always changing [4].

This means failures and N-1 outages must be accounted for in regular contingency analysis studies [5]. Even if something unexpected and unfavorable happens, the need will still be met to a certain level. Protecting an infrastructure system, such as the electricity grid, against low-impact and high-probability incidents [6] has long been seen as crucial to guaranteeing the system’s long-term stability.

1.1. Background

Natural disasters have increased during the past few decades due to climate change and global warming [7]. People all around the world are used to extreme weather, including long, hot summers, cold, icy winters, sudden and devastating floods, severe and destructive storms, and catastrophic hurricanes. Some of these occurrences are more probable than others in a given area. According to the available data, their prevalence is undoubtedly rising [8].

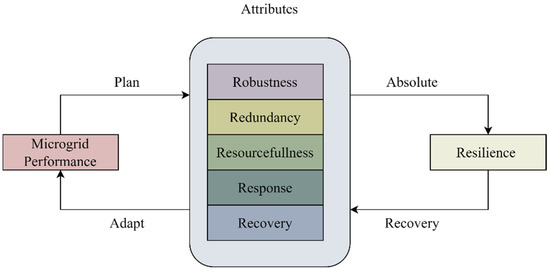

There has been a lot of focus in recent years on figuring out how to use novel energy storage technologies and how to maximize energy efficiency in smart microgrids that serve many load types. Cost cutting, improved electricity reliability, and less environmental effect were just a few of the goals of this study’s research. In a smart microgrid [9], a centralized control unit maintains and analyzes a low-voltage distribution network that incorporates electrical and thermal loads, energy storage sources, and distributed generation sources. Figure 1 shows the resilience in microgrids with respect to the performance of the microgrid.

Figure 1.

Resilience in microgrids.

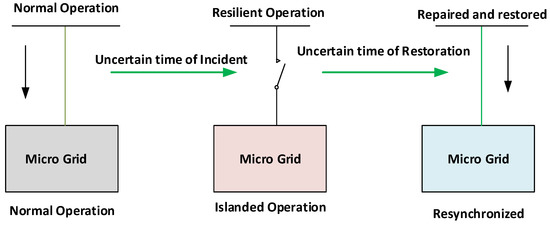

A microgrid can either be tied to the main power system or operated independently. In grid-connected mode, the microgrid can function independently of the upstream grid, simulating an island-style setup [10]. In the island mode of microgrids, disengagement from the distribution network occurs either voluntarily or involuntarily owing to a failure of the distribution network [11]. Increased frequency of natural disasters such as severe weather, earthquakes, and floods, among others, has reduced the effectiveness of power distribution networks and smart microgrids. As a result of these disasters, electrical grids were injured and extensively destroyed, and in certain countries, major brownouts and blackouts occurred.

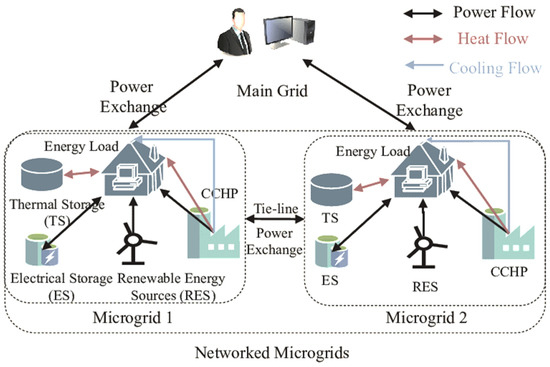

1.2. Networked Microgrids

Microgrids using DERs such as distributed generation (DG) and distributed storage (DS) are shown interconnected in Figure 2. Downstream of a distribution substation, networked microgrids are managed by MGCCs. Individual microgrids are linked together by tie-lines as well. Actual and reactive power demand, cooling and heat demand, thermal storage (TS), electrical storage (ES), and trigeneration or combined cooling, heat, and power (CCHP) units are the specific components of a microgrid. The DERs all have their own controllers (LC). For microgrid networks to function reliably and steadily, MGCCs and LCs must be able to communicate with one another.

Figure 2.

Networked microgrids.

1.3. Microgrid Central Controller Constraints

Due to the significant damage that severe storms cause to power grids, resilience has become an increasingly important topic of discussion. Even though there is a wealth of literature on the topics of hardening and restoration [4,5,6,7,8,9], proactive scheduling and emergency response [10] are still largely unexplored. In order to provide proactive operation and emergency reaction during extreme occurrences, it is necessary to consider the challenge of maintaining constant situational awareness. To ensure the distribution system’s robustness prior to extreme events, the system operator must also deal with numerous uncertainties, including:

- weather uncertainty

- the reactions of various microgrid central controllers (MGCCS)

- resilience issues related to critical buses and influential lines

- generation and load uncertainties.

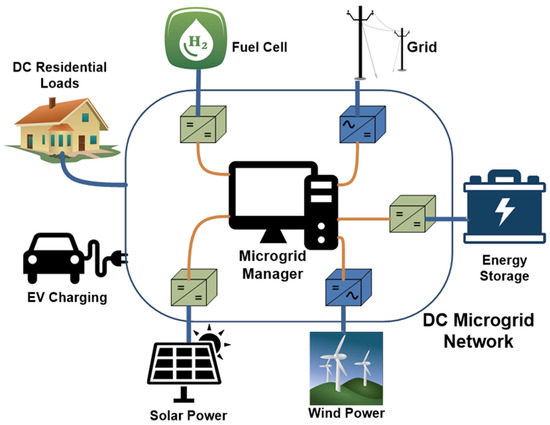

To get around these problems, our work here focuses heavily on proactive scheduling. Given these considerations, the distribution system’s proactive robust scheduling challenge has been getting a lot of attention of late. With the advent of networked microgrids to strengthen distribution system reliability, proactive scheduling of MGCCs is more important than ever before. An energy storage (ES) device-based proactive operation method for microgrids is proposed in [11] to improve the grid’s reliability in the face of unforeseen events. In addition, [12] develops a reliable routing and scheduling system for efficiently distributing the mobile ES units. When evaluating a power grid’s resilience, the ability to keep critical loads running is essential, especially in the face of a catastrophic incident. Therefore, in order to provide resilience management, [13] suggests related constraints on transient stability, such as limits on frequency deviation and limits on bus voltage magnitude and phase angles. Figure 3 shows hierarchal control strategies in microgrids.

Figure 3.

Hierarchal control strategies in microgrids.

Smart microgrids have no interruptible and sensitive loads; thus, system planners and strategy makers have had to come up with new approaches to improve reliability and resilience. To this end, resilience must be factored into analyses of dependability, stability, and security [12].

The ideas of resilience and reliability are contrasted and analyzed in Table 1. A robust system can function normally in the face of extreme, but improbable, stressors. Resilience in a network is shown when it recovers from disturbances and continues to supply loads reliably [13]. Networks that are resilient are able to anticipate and recover from failures, handle and tolerate failures, respond quickly to disturbances, cut back on the causes of failure, and either quickly return to normal or adapt to a new state in a stable manner [14].

Table 1.

Comparison between resilience and reliability.

However, intensive modeling and optimization are necessary for energy storage to make economic sense. Adopting a precise and realistic ESS model improves the smart microgrid’s resilience, allowing it to better meet its economic and security goals. This paper uses an analytical and economic approach to argue that using batteries as energy storage for a prototype microgrid leads to a considerable increase in resilience and cost savings. Most importantly, this research:

- (a)

- Employs a two-way analysis technique using ANFIS.

- (b)

- Initially, PV (power management by ANFIS), wind (power management by fuzzy), and battery energy management system (power management by supercapacitor) general backgrounds of resilience in power systems are modeled, which include resilience enhancement efforts by various regions.

- (c)

- In the second stage, the methods employed by microgrids to increase their resilience in the face of major outage occurrences including rainy weather, load shedding, and extreme weather events are examined.

- (d)

- The model we have developed does not support Crisp value and instead works on a wide range of elements at once. In this case, we have assigned a weight to each element based on how much we think it belongs in the set.

- (e)

- Outage management and advanced operating methods are examples of this type of strategy, and they are used to lessen the blow of any significant interruptions.

2. Related Work

Having access to reliable electrical power to fulfill growing demand is a basic need in today’s society. Because of this, a sophisticated power system is intended to supply electricity at a specific quality and continuity, but it is nevertheless susceptible to vandalism, natural disasters, and harsh weather events. More frequent extreme weather events increase the likelihood of a black sky scenario, in which the power grid collapses. Therefore, the importance of studying power system resilience has never been higher. This research [2] takes a multifaceted look at the topic of power system resilience.

Given the increasing severity and frequency of natural catastrophes, researchers in the energy sector are examining strategies to strengthen the system’s resilience to such events. Microgrids are currently being researched for possible applications to increase the reliability of electricity networks by utilizing local resources including renewable energy sources, electric vehicles (EV), and energy storage systems. However, the price of the investment could go up if more storage systems are added for redundancy. This study [8] suggests integrating preexisting EVs into microgrids to increase their resilience to blackouts. In the event of a blackout, grid-connected microgrids can rely on mobile EVs to provide backup power, as proposed by the aforementioned algorithm. To find EVs to supply energy to island microgrids, one must go through a three-stage process. Both standalone and interconnected microgrids feed information about demand and supply to a centralized energy management system (CEMS). Second, CEMS determines which connected microgrids within the system will provide power to the isolated microgrid. Depending on the locations of the selected microgrids, electric vehicles (EVs) will be used to power the islanded microgrid. The proposed strategy improves resilience in simulations without the necessity of a power link between microgrids.

Critical infrastructure, especially electrical energy networks, is vulnerable to natural disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes as well as deliberate acts of sabotage. Hardening and operational actions can increase resilience to extreme occurrences. Long-term hardening includes making preparations for the reinforcement of power system infrastructures in advance of an incident. Short-term operational measures, such as network reconfiguration and generation scheduling during and after disasters, are adopted with the construction of several microgrids to strengthen the power system’s flexibility in the face of extreme occurrences. As a result of this study, a comprehensive strategy for strengthening the distribution system’s ability to withstand disruptions was created [5]. The framework is built on two models, called defender–attacker–defender, which aim to reduce the amount of load shedding that occurs in the system during intense events. As a first step in improving the system’s robustness, some preliminary hardening techniques are investigated. The second level takes into account the worst-case scenarios, while the third level actually implements the configuration changes required to minimize load shedding. There are merits and flaws to both designs. The optimal reinforcement strategy and worst-case attack scenario are established at level 2, while optimal power distribution in islanding mode is attained at level 3. The proposed models are computationally compliant because they employ a trilevel mixed integer optimization problem and a column constraint-generating approach. The IEEE 33-bus and 69-bus systems were used in [5] to test the models’ versatility and utility.

Microgrids require a method of resilient power management, and Dehghanpour et al. [15] provide one based on the market (MGs). Keeping in mind both local and global constraints, such as microsource voltage levels, distributed optimization is utilized to determine the optimal allocation of system resources among several MGs. The proposed method uses probabilistic reasoning to evaluate the unpredictability of the decision model in advance of extreme events and to increase system resilience in the event of unit failure. The Nash bargaining solution (NBS) is used to resolve the multiobjective optimization problem that is power management (NBS). By increasing the power reserve and adjusting the operating point to maintain voltage and power limits across all of the MGs, as seen in the simulations, the proposed method can increase the system’s resilience and prepare it for extreme events and unit failure.

Microgrids have a different time frame and implementation environment than lower-level control frameworks, and this study [16] investigates how these discrepancies in the EMS affect the microgrid. The average effects of renewables and loads, for instance, and the possibility of time shifting, and magnitude variation are only a few examples. Since reliability in islanding mode is so important, we employ a resilient microgrid as a case study. By contrasting the actual and predicted ideal battery state of charge, our experiments demonstrate that nonideal effects occur naturally in microgrid systems. The resilience of microgrids against blackouts might be harmed by unscheduled load shedding. It is possible to speed up the battery’s deterioration by deep cycling it briefly. Microgrids can benefit from a more robust power-sharing mechanism.

Due to their capacity to isolate and protect renewables, microgrids are being evaluated as a solution to deal with large power disruptions. Three methods are used in this study [10] to explain how microgrids affect the reliability of the electrical grid. An introduction to power system resilience is provided, along with some concrete ways to strengthen it (such as disaster modeling, resilience analysis, and power system resilience enhancement). Microgrids, microgrid networks, microgrid dynamics, and the resilience of different energy networks all receive attention in Stage 2. Finally, the resilience of microgrids during power outages is studied. Significant outages can be reduced with the help of preemptive planning, outage management, feasible islanding, and enhanced operational procedures. The frequency of an occurrence and the amount of time it takes for the aftermath to clear allow for categorization. All the many kinds of microgrids, the methods they use to ensure their resilience, and their distinct parts are discussed. Existing research gaps are identified, and suggestions are made to further develop methods of operating microgrids with a focus on resilience.

Related to load, renewable generation, market price signals, and time of occurrence, this study [17] analyzes microgrid islanding and survival. The maximum allowable parameter deviation is dynamically calculated based on past data. Preparation times are calculated using fragility curves, which take into account both the expected occurrence time and the constraints imposed by the microgrid’s components. To lessen the necessity for load shedding, renewable energy and other resources will be expanded as part of an emergency demand response strategy. Resilience index measures how much this approach improves microgrid performance. Normal mode uses adaptive robust optimization to evaluate event occurrence time and uncertainty level. In emergency mode, we run 1000 Monte Carlo simulations to assess the impact of unknowable parameters on operational costs, load reduction levels, and the variability of the resilience index.

Critical loads on the distribution network must be restored using microgrids and distributed generation whenever practicable. One article [9] proposes a two-phase approach to restoring critical loads using distributed generation, microgrids, and demand response programs in the wake of a major disaster. First, the outputs of the demand response and the critical load restoration status when a disaster has occurred. First, electrical islands are identified using a novel model built on top of the extended Benders decomposition technique. Second, in order to make the most of the restored essential loads, we must take into account demand response programs and operational restrictions. Testing systems with 33 buses and 69 buses validate the suggested method.

Extreme weather is more likely to cause damage in rural and remote places than in populated urban centers. Besides disrupting electricity, natural catastrophes can also affect water and the ability to cook food. A growing number of people believe that our food supply, water supply, and energy consumption are all interconnected. In order to provide essential services such as cooking, water, and power to rural regions, it has been suggested that they adopt smart integrated renewable energy systems (SIRES). The crucial and noncritical requirements of a rural community are underlined. The proposed method is evaluated in both wind and hydropower subsystems, which are vulnerable to natural calamities. SIRES has been shown to increase overall resilience [12] when compared to microgrids.

If you want to make your distribution network more resistant to high-probability, low-impact events such as a component failure, natural disaster, or cybercrime, then a microgrid is a great option. A microgrid’s ability to withstand, adapt to, and recover from disruptions is influenced by the nature and magnitude of the events to which it is subjected. The location and risk profile of microgrids should be taken into account. To evaluate the microgrids’ robustness, we aim to represent the complex interplay of multiple elements. The authors of [3] argue that a microgrid’s site-specific absorption, recovery, and adaptation capacities may be measured. A person’s level of proficiency in this area can be gauged by their level of situational consciousness. The use of an interdisciplinary approach to analysis is demonstrated by a case study.

For resilience and island mode capabilities, microgrid (MG) investment planning often takes static security constraints into account. Cascade disconnection of DERs inside the MG due to unplanned islanding can lead to demand loss of varying degrees. Taking into account both high- and low-probability events, the authors of [18] introduce a stochastic resilient investment planning model. Like the LIHF, the unexpected islanding of the MG following a catastrophic event is fraught with doubt, as is the DER’s ability to generate power in response to constantly shifting demands. The suggested investing method incorporates islanding limits to mitigate both types of uncertainty. As it stands, present approaches cannot directly optimize a nonlinear dynamic frequency response model due to constraints imposed by the transient response. The optimum strategy for investing can be determined by following the three steps outlined in this study. The effectiveness of the proposed approach is evaluated using the CIGRE 18-node distribution network.

The utility of the future, according to specialists in the field, would collaborate with self-sufficient neighborhoods to set up microgrids. The long-term viability and dependability of the area’s power source will be enhanced. This urban tale is short on details. Since microgrids are still novel in regulatory and commercial contexts, there is no universal solution. This article [6] discusses four different microgrid projects that have been implemented in North America. These examples are taken from the Microgrid Project Tracker by Navigant Research and feature some of the most advanced microgrids ever built. Using in-depth interviews and project-to-project comparisons, we can learn valuable information that can be used for Community Resilience Microgrids. Important stakeholder responsibilities will be graphically depicted as the microgrid project proceeds, allowing anybody interested to understand their place in the larger microgrid development ecosystem. When complete, the document will provide stakeholders with a guide to the generic practical difficulties that will arise throughout the project’s life cycle, from inception to funding, construction, and operations.

More power–electronic (PE)-integrated distributed energy resources are being used in today’s modern power systems (DERs). Overload capabilities and frequency response patterns of DERs such as solar and wind differ from those of conventional power plants. In light of the increasing prevalence of renewable energy sources in the world’s power grids, this article explores strategies for managing and regulating PE-interfaced DERs in the event of a power outage or voltage drop. To regulate DER units, reduce their susceptibility to transients and disturbances, accelerate the response and recovery of predetermined metrics and parameters, and keep their operations in a satisfactory state, the authors of [11] use sophisticated model predictive control (MPC). After being tested on an IEEE 34-bus test feeder, it was found that the proposed method successfully mitigated system transients and enhanced grid edge and overall voltage resilience.

Microgrid energy management models (MEMs) are compared to ROP methods in [19]. The SR measures toughness, and the results show that ROP makes a noticeable difference in this area. When the likelihood of inverter failure increases, the developed ROP strategy becomes superior to the traditional MEM approach.

The definition of a “smart grid” was presented first in [7]. When resilience is compared to self-healing, it becomes clear that resilience encompasses both self-healing and other services. Nanotechnology and the merging of energy and gas networks are just two of the issues covered in the “other” section. The author concludes by stressing the importance of taking DC microgrids into account while designing their program.

Smarter technology, equipment, and controls are being integrated into the electric power grid to make it a more efficient and reliable system. Robust control and operation are necessary due to the complexity of a smart grid. Resilience in the power grid refers to its capability to withstand and quickly recover from catastrophic events that occur with relatively low frequency but have a large impact. There is cause for concern regarding the safety of bidirectional data and power exchanges in a smart grid. The high unpredictability and volatility of renewable energy sources such as solar PV and wind power present new challenges. Power outages and interruptions that are not scheduled pose a risk to systems that operate in real time. Strong electrical infrastructure is increasingly vital after natural disasters such as hurricanes, cyclones, and wildfires. The key to addressing these challenges is resilience in the smart grid. One study [4] investigates the use of AI to improve the reliability of smart grids. Multiregional and multimachine power systems are under the scope of automated generation control (AGC). It is possible to use AI to forecast solar irradiance, PV power generation, and the frequency of the power grid. State-of-the-art persistence models are surpassed by AI short-term prediction models. Prediction models built with AI help power grid operators make informed decisions. Improved multiarea tie-line bias control was achieved by the use of projected PV power and bus frequency. For large power grids, researchers have created a decentralized, parallel SCOPF algorithm. Real-time digital simulators, hardware/software phasor measuring devices, and a real-time weather station were used to test and compare the different approaches.

Cost-effective demand response and electricity supply for homes are two of the many benefits that distributed energy resources (DER) bring to the table. Customers have the option of using either renewable or conventional power plants. Through the use of MILP, we can ascertain when and at what power level each dispatchable unit should operate in order to stay within reasonable parameters. The percentage of electricity generated from solar and wind has increased in recent years. Despite their low cost and widespread availability, these products’ myriad features could prove challenging to coordinate. In [20], three different cases of energy management are analyzed. The first and second cases, respectively, include markets with fixed and variable pricing. The third scenario involves using nonrenewable resources to make up for power shortages in order to reduce the unpredictability of RES. The proposed solution lowers operating costs in a 24 h test in a residential area.

The ANFIS is used to control a double-fed induction generator in [21]. (DFIG). Wind energy is a part of the grid connection strategy. In this application, DFIG powers wind turbines to generate alternating currents for the grid. Simulink and MATLAB can be used to model induction generator installations in the system. Using a rotor frame of reference and a vector control system that can adapt to changing conditions. In order to control the active power and voltage of wind energy, a convertible rotor ANFIS is used. The effectiveness of the ANFIS controller is examined, even under the most trying conditions. The ANFIS control unit improves power quality and system stability, as shown by simulations.

There has been a rise in the popularity of AC, DC, and hybrid-MG smart microgrids (DRE). Population control strategies and institutional frameworks are the focus of this field’s research [22]. There has not been much focus on undertaking a comprehensive and coordinated literature review of hierarchical control strategies for various microgrid configurations. With this method, the control hierarchy of the MG system is broken down into its primary, secondary, and tertiary components. The article discusses the advantages and disadvantages of each method of MG analysis. The essay also takes a look at the benefits and drawbacks of conventional methods of control. The future of MG control is simulated and analyzed based on the existing literature.

Microgrids rely heavily on distributed generation (DG) to integrate power sustainably. Inverters link DG units to the grid so that renewable energy can be used. Integrate more reliable means of control into the interface of currently functioning inverters. Microgrids are more efficient, reliable, and resilient when controlled by a controller. This research [23] examines different types of control that can be used in either a completely autonomous microgrid or one that is connected to a larger power grid. Furthermore, the distinctions between the various control methods and distribution system control are elaborated upon. Different types of control structures are examined and compared, including those that are centralized, decentralized, and distributed. In particular, it highlights controller characteristics and self-healing control. For further microgrid study and development, this review article will be a useful starting point.

Because of the proliferation of distributed generation facilities at the distribution level, the use of microgrids has become increasingly important. Microgrids may be tied to the main power grid or operate independently (connecting to the utility grid). Microgrids have both positive and negative effects on the distribution system’s security. The most crucial distinction between island and grid modes is the magnitude of the short circuits they experience. The authors of [24,25,26] built an overcurrent relay that can switch between several operating modes for microgrids. Recognizing the operational mode of a microgrid is made faster and more accurate by using an adaptive technique. The ideal parameters of the relay are activated according to the microgrid mode. Current and voltage are used by the relay for all of its internal operations. Since there are not any special communication systems required, the relay can be utilized with any network. A microgrid is used to try out the method. The benefits of the intelligent relay over the conventional overcurrent relay have been demonstrated numerically.

To alleviate financial burdens, human casualties, and equipment placement issues, distribution networks should strengthen their use of microgrids. The allocation of resources in networks results in damage to ecosystems, economies, and lives. This stage of system design is complicated by voltage and frequency fluctuations brought on by major load shifts or distribution network breakdowns. The entire distribution system can be wiped out if something catastrophic happens. An ideal approach is required to address these difficulties. Current research [25] is centered on developing and deploying a multifunctional phasor measurement device to enhance parallel state estimation in distribution networks. The phasor unit is used to calculate the duration of both internal and external disturbances. Due to the aforementioned difficulties, a neural fuzzy technique will be used in this investigation, and system training will be necessary to install and position likely flaws. The distribution of loads in the network is the primary concern while setting up a phasor measurement device. These benefits are reflected in MATLAB/Simulink simulations.

Microgrids are being used in this project to enhance the reliability of power distribution systems that are interconnected. Repairing secondary distribution voltage disparities and current harmonics, UPQCs are a staple of modern power grids. A global solution for power management is presented, and it makes use of an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system in conjunction with separate compensating devices at common connections (ANFIS). Power quality in conventional systems may benefit from UPQC because of its ability to increase power utilization and system efficiency. Energy loss in renewable energy microgrids is nearly nonexistent. The proposed method has been shown to enhance power quality using case studies, a prototype, and MATLAB/Simulink simulations [26]. In order to normalize voltage across connections, the proposed control method lowered peak voltage anomalies. When compared to PI, which reduces current harmonics by 14.74%, UPQC-use P’s of ANFIS results in a 21.13% reduction in harmonic distortion [27,28,29,30].

In order to increase the reliability and efficiency of power networks, microgrids are increasingly being used. Problems with MG technology are commonplace because of the unpredictability of RERs. If you want a stable system, you need an MG with a powerful PMS. In order to regulate an AC MG consisting of a DG, a DFIG, and a solar PV panel, this research suggests a PMS. The goal of the proposed method [31] is to equalize MG power, cut down on DG’s fossil fuel consumption, maintain stable voltage, and monitor each RER’s maximum power point (MPP). The ANFIS is taught via particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms (GA) to achieve its objectives and maintain an appropriate level of production relative to consumption. By simulating an AC MG equipped with a PMS in MATLAB/Simulink, we may analyze the system’s behavior in a variety of environments. The efficiency of the method was demonstrated by simulations with both symmetrical and asymmetrical electrical failures.

3. Proposed Methodology

- In this setup, ANFIS performs analyses in both directions. At first, the modeling attempts to understand how PV, wind, and battery energy systems operate in various locations to improve power system resilience (all managed by ANFIS, fuzzy, and supercapacitor, respectively).

- Microgrids’ ability to withstand major outages caused by things such as rain, load shedding, and extreme weather is the focus of the study’s second section. Our model will consider several factors simultaneously rather than relying on a single, clear value.

- All of the collection’s components are members, but some are more so than others.

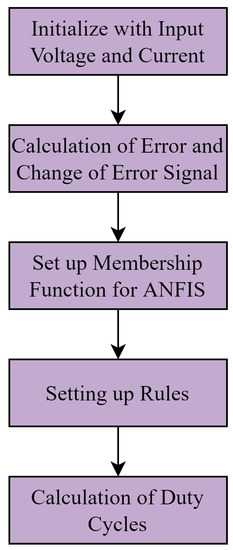

- Outage management and cutting-edge operating techniques are two such methods used to lessen the blow of major disruptions. Figure 4 shows the flow diagram of the proposed study.

Figure 4. Proposed flow of study.

Figure 4. Proposed flow of study.

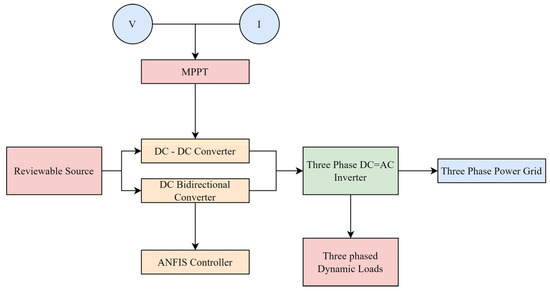

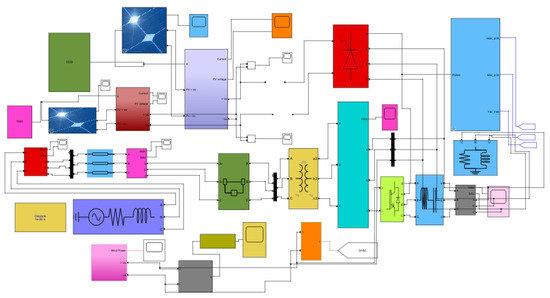

To address the issue of system resilience in both synchronized and islanded grid mode/operation in the event of a catastrophic event and under normal conditions, a bidirectional ANFIS (FLC) was developed. The system consists of the sun, the wind, the battery, and the load. The solar, wind, and supercapacitors of the battery system are controlled by ANFIS. It all started with developing a mode-based control algorithm to account for the present configuration of the system. Relative ANFIS will improve the robustness of emergency, energy-saving, and normal modes. The DC connection is held constant and energy can be shifted between sources and sinks thanks to a bidirectional converter. The ANFIS algorithm calculates how much power may be drawn from PV to meet the demands of the system at any given time. Overcharging or completely depleting a battery is avoided. The islands’ wind system is fully functional. Battery and system efficiency are both boosted. Inverter efficiency is raised through the use of a synchronous reference frame transformation. Using data from the sun, the wind, and the state of charge, the fuzzy rule-based ANFIS will take over. There is a comparison between the synchronized grid and ANFIS. This MATLAB/Simulink analysis will demonstrate the robustness of the system under both typical and extreme conditions. Renewable energy and membership features are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Renewable energy sources and the membership functions.

In the first step, we will define some rules as shown in Figure 3. The rule base will be:

- If solar is 0–30% (NL) AND wind is 0–30% then emergency mode (NL)

- If solar is 0–30% (NL) AND wind is 30–60% (M) then emergency mode (NL)

- If solar is 0–30% (NL) AND wind is 60–100% (PL) then energy conservation mode (M)

- If solar is 30–60% AND wind is 0–30% (NL) then emergency mode (NL)

- If solar is 30–60% AND wind is 30–60% then energy conservation mode (M)

- If solar is 30–60% AND wind is 60–100% (PL) then normal mode (PL)

- If solar is 60–100% AND wind is 0–30% (NL) then energy conservation mode (M)

- If solar is 60–100% AND wind is 30–60% then normal mode (PL)

- If solar is 60–100% AND wind is 60–100% (PL) then normal mode (PL)

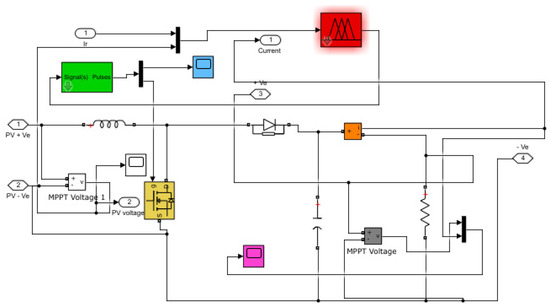

3.1. MPPT and ANFIS Control Scheme

Fuzzy logic controllers (FLC) based on an adaptive neural network, or adaptive neuro fuzzy interface systems, are used in MPPTs (ANFIS). Because it does not require a precise mathematical model, ANFIS can handle a variety of inputs. There are three phases to the ANFIS: fuzzification, rule-based table lookup, and defuzzification. In the process of fuzzification, the membership functions are employed to convert quantitative inputs into linguistic variables. Most frequently, the MPPT ANFIS will take in the error (E) or the change in the error (E) as an input. The ANFIS input process begins with calculating the error (E) and the change in error (CE). FLC outputs typically display variations in duty ratio (represented here by a shift in duty cycle (D)). As can be seen in Figure 5, the ANFIS control method is implemented. These equations represent a model of the subsystem of the ANFIS controller [25]:

where E(k), CE(k), I, V, I(k), and V(k) denote error generation, error change, current change, voltage change, source current, and source voltage.

Figure 5.

Setting up ANFIS with MPPT control schemes.

3.2. Inverter ANFIS Control Scheme

To transform direct current (DC) power into standard AC power, inverters are utilized in renewable energy systems. The fundamental purpose of an inverter is to safely and reliably transmit electricity generated by solar panels to the electrical grid. As for the inverter, it is controlled via the ANFIS mechanism.

By dividing the d-q current value produced by the Park transformation by the expected value, e, the error was determined (k). When an error occurs, the FLC is notified. FLC regulates the current in a device. The d- and q-axis currents were independently controlled using two FLC devices in this experiment.

A phase-locked loop (PLL) is implemented at this node initially to track the grid frequency. Signals are generated by a pulse width modulation (PWM) block and sent to the inverter as control voltage from the inverter controller [12]. The FLC consists of the steps of fuzzifying, learning a set of rules, inferring, and defuzzifying. The FLC produces a magnitude of change in the amplitude of the reference signal as an output (k). It takes as inputs both the error rate of change (e) and the error rate of change from the previous iteration (e (k 1)). The process begins with a fuzzification step, which translates the numbers into linguistic values.

Use the FLC’s ANFIS to develop membership functions and regulations for FLC members. The ANFIS improves upon traditional fuzzy derivation by using the insights of neural systems theory. Neural systems are the best learning computers currently available. No amount of input may result in a fuzzy system becoming smarter or more flexible. ANFIS is utilized because it enables fuzzy systems to learn from the data they are representing (by adjusting membership function parameters), and so a model of ANFIS was built with the inputs and outputs of the proposed FLC as training and validation data, respectively. Figure 6 shows an ANFIS inverter control scheme, Figure 7 shows the schematic diagram of the ANFIS inverter control scheme, and Figure 8 shows an ANFIS MATLAB diagram.

Figure 6.

ANFIS inverter control scheme.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of ANFIS inverter control scheme.

Figure 8.

ANFIS MATLAB diagram.

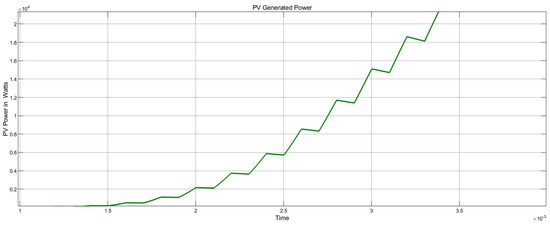

Most of the environmental issues of recent years may be traced back to the increase in human-made energy sources such as factories, vehicles, and fossil fuels, which release more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The fundamental goal of this research is to find effective ways to combine various clean energy sources to generate power. Multiple renewable energy sources, such as photovoltaic (PV), wind, and fuel cells, are compared and contrasted across a range of climatic conditions, and the feasibility of using a diesel generator in the event of grid failure is also explored. As a result of this study’s findings, a MATLAB-based simulation has been created to evaluate the efficacy of the ANFIS-based MPPT controller designed (shown in Figure 8) to maximize output from a wide range of renewable energy sources. The purpose of this study is to optimize the energy management of a resilient microgrid system, which uses a range of renewable energy sources to generate electricity and is connected to the grid via a battery. This system is controlled by an ANFIS.

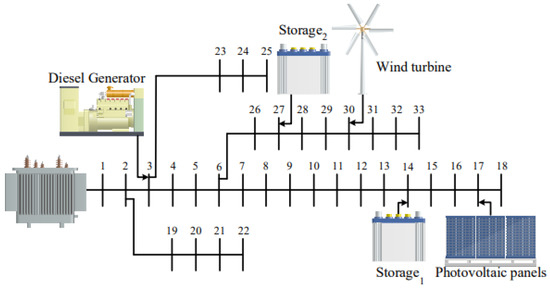

4. Simulation Results

This research will model the proposed resilience mechanism using the IEEE 33-bus standard network and the ANFIS controller. To improve the existing AC power flow condition, two renewable distributed generators are wired into the grid at key buses. The model’s reliability has been increased thanks to the addition of two energy storage devices. In addition, a modest diesel generator is used to provide resilient and reliable operation, making it possible for the microgrid to serve as many loads as possible in the post-fault scenario. Diesel generator, solar unit, and wind power unit DER capabilities are 1400, 2000, and 1500 kW, respectively. Both ESSs have maximum capacities of 5500 and 4000 kW and utilize sodium–sulfur (NAS) batteries.

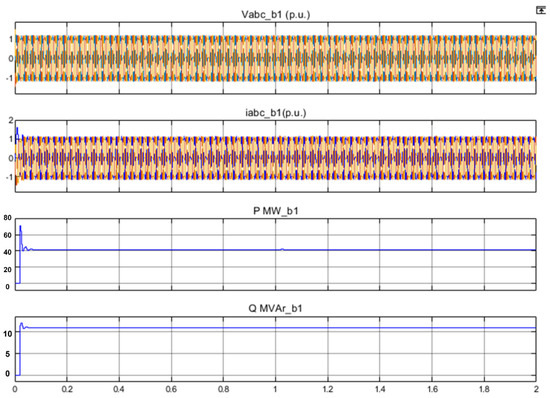

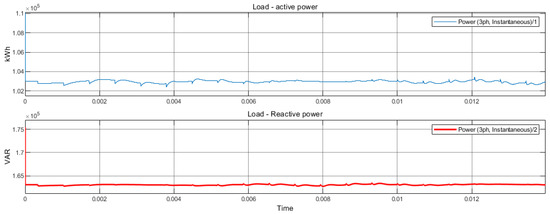

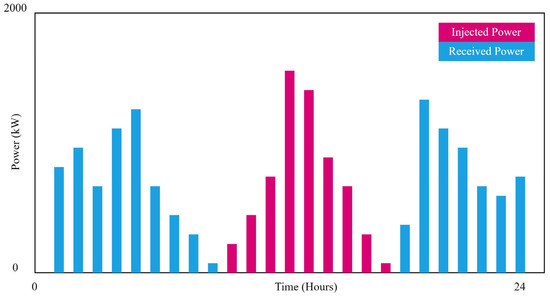

Load profile projections, renewable generation forecasts, a diesel generator dispatchable schedule, and ESSs curves are all displayed in Figure 9. The active and reactive power are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Microgrid setup with distributed energy resources (DERs) present: a case study.

Figure 10.

Active and reactive power.

As was previously mentioned, there is a predetermined share of demand, known as sensitive loads, that get priority during times of resilience since they rely on constant power. Next, the resilience index of the case study microgrid with an NAS battery is estimated, factoring in critical conditions based on the occurrence of storms and severe weather, with the help of the ENS index and normal/faulty operation indicators in two cases of operation of isolated and grid-connected modes.

Assuming the proposed strategy achieves energy parity and fits within the network’s current limits, the aim is to minimize the following function [25]:

Following the previous equations, the objective function FESS stands for the ESS in the resilient state, ProbESS for the likely ESS operation cost in the resilient condition, and costESS for the full ESS operation cost in both normal and critical conditions. It is convenient to write the amount of energy stored in the ith capacitor at time t, and likewise the energy content of the charging and discharging rates, Pch and Pdch, of the storage device and the required minimum number of energy storage systems (NESS) for a certain microgrid.

When calculating resilience, it is important to account for operational uncertainties, such as existing limits on normal and preincidence (PT) states, as well as mistakes in extreme weather forecasting, improper battery charging and discharging, inaccurate real-time and day-ahead market prices, and so on. The ability of a microgrid to recover from disruptions caused by catastrophic events (PR) such as the sudden shutdown of power generation units, the formation of unwanted islands, the occurrence of unsynchronized events, etc., must be estimated both during and after the occurrence of such events [25,26].

For a microgrid to operate reliably when equipped with ESS, its degree of reliance on the upstream distribution network is expressed by an index related to normal operation and defective operation. The indicator’s value should ideally be low, as this bodes well for microgrid reliability [25,26].

Therefore, whenever the generation from the smart grid exceeds the needs of the upstream distribution network, ESSs are used to store the excess energy. When demand is high, this energy is sent back into the grid. If the microgrid’s generation capacity is low, it must buy power from the upstream network to make up the difference, as the amount of energy stored in the ESS is proportional to the amount of excess generation. Incorporating the Energy Not Supplied (ENS) index, widely recognized as a crucial part of the stress-based resilience assessment framework, into the model is a natural consequence.

For this reason, ensuring the resilient operation of ESS-equipped smart microgrids necessitates factors such as the restoration time based on types of storage devices, the capability of smart microgrids to operate in an isolated and islanding state, and appropriate controlling paradigms for ESS response prior to, during, and after faults.

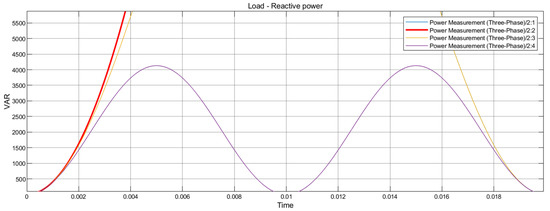

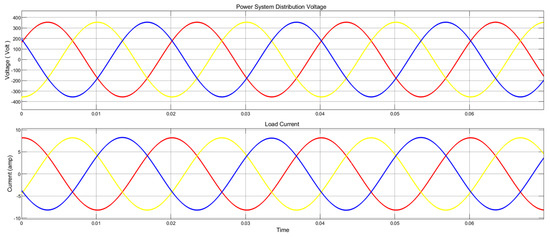

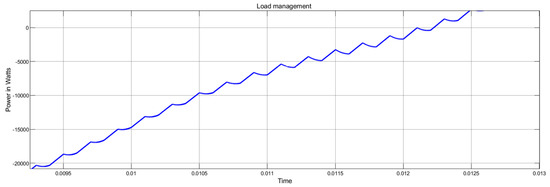

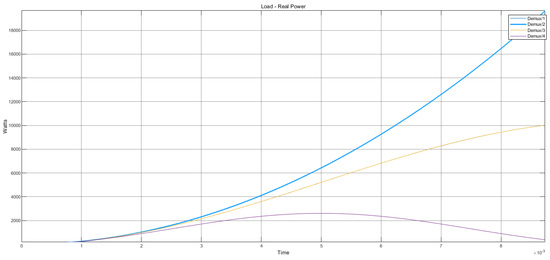

Instability and power imbalances can occur when a system’s load is increased. In order to prevent voltage swings and resolve power quality issues, controllers must first achieve a power balance between demand and supply. The controllers’ voltage response time improves by 0.25 s as the load doubles from 100 kW to 500 kW. While fuzzy PI can restore stability to a system, fuzzy PID can do it more quickly and to a greater extent. Accordingly, the voltage profiles of a bus with varying loads can be optimized. As seen in Figure 11, ANFIS will pick the power system for you automatically. Figure 12 depicts the distribution of reactive power throughout the load. Figure 13 depicts the current and load distribution for all three phases as recommended by the ANFIS controller. Moreover, the load management profile is shown in Figure 14. The wind-stabilized reactive and active power are shown in Figure 15. Also, the input actual real power of the load is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 11.

Automatic ANFIS power system selection.

Figure 12.

Distribution load reactive power.

Figure 13.

ANFIS controller three-phase voltage and current.

Figure 14.

Management of load.

Figure 15.

Wind-stabilized reactive and active power.

Figure 16.

Input actual Watts of power.

All feeders are equipped with switching mechanisms to isolate the defective zone in the event of a malfunction on the microgrid distribution network or on the upstream side of the microgrid. The results of the simulations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

State of resilience indices.

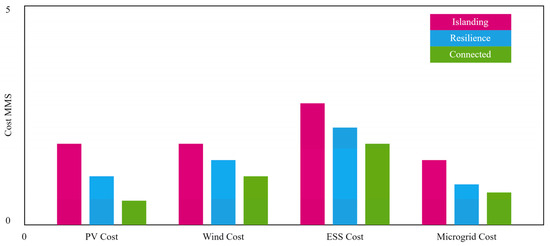

Figure 17 shows the size determination state of the microgrid in its resilience condition during the case study.

Figure 17.

Size determination state of the microgrid in its resilience condition during the case study.

In Figure 18, we see the ANFIS-based economic analysis of the smart microgrid operating in both grid-connected and islanding modes (when in a resilience state).

Figure 18.

Economic analysis of the smart microgrid.

The smart microgrids economic analysis of grid-connected and islanding modes of operation are represented graphically below (in resilience condition).

Charging and Discharging at Different State of Charges (SOC)

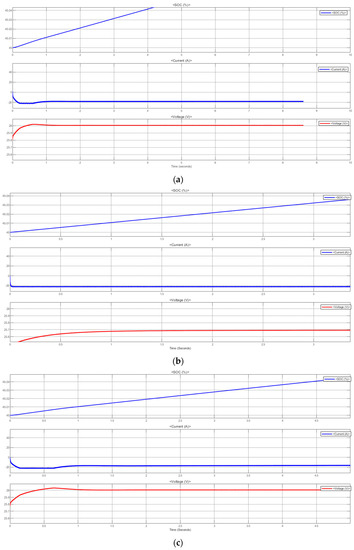

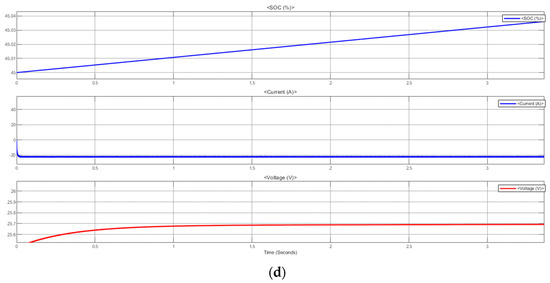

To optimize the timing of large-scale renewable energy installations including solar panels, wind turbines, hybrid generators, and batteries, we present an ANFIS model of the BESS in this research. Based on an evaluation of the unpredictability and uncertainty of wind output, suggestions are made about the limitations of BESS accounting for the influence of power on system dispatching, and the cost of auxiliary services of systems that are eased by BESS is quantified. With the goal of optimizing the benefits of a wind-storage union system, an ideal capacity model is built by considering the expenses of purchasing a BESS, the savings from wind curtailment, and the compensation for auxiliary services. Also, the ideal model takes into account the effect of the irregular charge/discharge process on the BESS cycle life by including a loss of the cycle life analogous to that experienced during the irregular charge/discharge process. In conclusion, results from a representative system suggest that compensation for ancillary services can encourage wind farms to set up BESS in profitable ways. Auxiliary service compensation, on-grid pricing of wind power, the investment cost of BESS, the cycle life of BESS, and wind uncertainty reserve level of BESS are just few of the variables that are tested in a series of sensitivity analyses to assess their relative effects on the optimal capacity. Charging and discharging at various charge states are seen in Figure 19 (initial SOC is 45%).

Figure 19.

Charging and discharging at different state of charge (SOC). (a) Solar/PV (x axis = BESS, y axis = time in seconds), (b) solar–wind hybrid (x axis = BESS, y axis = time in seconds), (c) wind (x axis = BESS, y axis = time in hours) and (d) battery (x axis = BESS, y axis = time in hours).

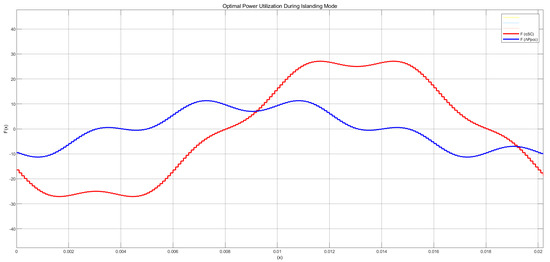

We determined that the error (e) could be calculated by dividing the d-q current value output by the input to the Park transformation (k). When an error occurs and the error state changes, the FLC is informed. The current is controlled by an FLC. In this research, two FLCs were employed to control the d- and q-axis currents separately. At this point, a PLL is set up to monitor the frequency of the power grid. Transmission of the control voltage from the inverter controller to the inverter is facilitated by signals generated by a pulse width modulation (PWM) block. Fuzzification, rule-based inference, and defuzzification make up the FLC. The output of the FLC is a change in the amplitude of the reference signal by a factor of du. It takes in both the most recent error and the one before it as inputs. To start, the numbers are fuzzified into linguistic values. Use the FLC’s ANFIS to create membership options and guidelines for the FLC’s constituents. Utilizing knowledge from neural systems theory, the ANFIS enhances the capabilities of conventional fuzzy derivation. No other machine can learn as quickly and effectively as a neural network. Fuzzy systems cannot acquire knowledge and improve without human intervention. For this reason, the ANFIS is set up: it allows fuzzy systems to better understand the data they are expected to model. Figure 20 depicts optimal power utilization during islanding. Charging and discharging can be calculated as follows:

where is the residential discharge, and is the charging state. T is the time, P, R are the active and reactive powers, n is the charging coefficient and S is the state of charging.

Figure 20.

Optimal exploitation of power in islanding mode.

5. Conclusions

As part of this study, a bidirectional ANFIS was built in order to examine the issue of system resilience in the context of synchronized and islanded grid mode/operation. This issue must be addressed both in the case of a catastrophic catastrophe and under conditions that are considered normal. The architecture of the system consists of the load, the battery, the load, and the components that are powered by solar and wind energy. ANFIS is in charge of the management of the solar, wind, and supercapacitor generators that make up the battery system. To begin, a control algorithm for the current state of the system has been constructed, with the mode that was picked serving as the basis for the algorithm. In the event of a crisis, the neighborhood ANFIS will assume control to safeguard the well-being of the community’s inhabitants, cut down on power usage, and keep operations running as usual. A bidirectional converter is used to connect the battery in order to maintain the DC connection at a constant level and to permit energy displacement caused by load and production. This is done in order to keep the DC connection at the predetermined level. The ANFIS algorithm makes it possible to extract the maximum amount of power possible from PV by taking into consideration the requirements imposed by the load that is currently being carried. The battery is shielded from the most extreme states of charge and discharge as a result of this design feature. When the wind system is confined, it performs according to how it was supposed to. Because of this, not only the effectiveness of the system but also the longevity of the batteries is improved. The overall performance of the inverter has been improved as a result of the synchronous reference frame translation for control. The amount of electricity generated by solar panels, the amount of power generated by wind turbines, and the current charge state will all have an impact on how the fuzzy rule-based ANFIS is implemented (SOC). A two-way analysis method using ANFIS is utilized in the construction of this model. To begin, the general backgrounds of PV (Power management by ANFIS), wind (Power management by Fuzzy), and battery energy management system (Power management by Super capacitor) resilience in power systems are modelled. This modelling includes the resilience enhancement efforts made by various regions. The second stage consists of analyzing the strategies that microgrids use to strengthen their resilience in the face of major outage occurrences such as rainy weather, load shedding, and extreme weather events. The model that we have designed does not support the Crisp value but rather operates on a broad variety of elements all at the same time. In this instance, we are giving a certain amount of importance to each component based on how strongly we feel that it should be included in the set. Some examples of this type of technique include outage management and advanced operating procedures; both of these are utilized to soften the effect of any severe interruptions that may occur. According to the findings, in the future there will be an increase in both the resilience indexes and the expenses. The analysis of the results shows that large-scale cascading outages and blackouts can be prevented through the resilient scheduling of various types of generation sources in a microgrid. These types of generation sources include small-scale nondispatchable uncertain renewable sources, nonrenewable conventional sources, and optimal charging and discharging of energy storage facilities. This scheduling method has the potential to improve things in terms of reliability by reducing the length of time that there is a gap in the delivery of electricity. In the event that there is a disruption or blackout, power from several different distributed sources is positioned to be able to handle the peak demand. Even if there is a difficulty with the electricity coming into the microgrid from upstream, the power that is created within the system is sufficient to meet all of the requirements. Even if there is a problem with the internal distribution network of the microgrid, islanding zones can continue to operate most loads on the remaining feeders, which keeps the power balance and voltage stability of the microgrid intact. Future distribution sources and the size of ESS devices have been meticulously planned out in order to guarantee that the reliability and resilience indices will be met.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; methodology, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; software, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., E.E.; validation, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; formal analysis, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; investigation, M.Z.A., M.A. and E.E.; resources, M.Z.A., M.A. and S.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; visualization, M.Z.A., M.A., S.I., A.u.R., H.K., K.M.A. and M.S.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, H.K., K.M.A., M.S. and E.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data sources employed for analysis are presented in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hossain, N.U.I.; Nagahi, M.; Jaradat, R.; Shah, C.; Buchanan, R.; Hamilton, M. Modeling and assessing cyber resilience of smart grid using Bayesian network-based approach: A system of systems problem. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2020, 7, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Mokhlis, H.; Lllias, H.A.; Mansor, N.N.; Shareef, H. State-of-the-art review on power system resilience and assessment techniques. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 6107–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kwasnik, T.; Anderson, K. Microgrid resilience: A holistic and context-aware resilience metric. Energy Syst. 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardene, I. Artificial Intelligence for Resilience in Smart Grid Operations. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Xin, A.; Jan, M.U.; Rehman, H.; Salman, S.; Rizvi, S.A.A. Improvement in the efficiency of inverter involved in microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Beijing, China, 20–22 October 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Baghbanzadeh, D.; Salehi, J.; Gazijahani, F.S.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Resilience improvement of multi-microgrid distribution networks using distributed generation. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 27, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahl, J.; Bebrin, M.; Paris, E.; Jones, D. Beyond the Buzzwords: Making the Specific Case for Community Resilience Microgrids. In Proceedings of the ACEEE Summer Study Energy Efficiency in Buildings, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 21–26 August 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski, J.S. Microgrids and resilience. Rynek Energii 2016, 2, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Xin, A.; Jan, M.U.; Abdelbaky, M.A.; Rehman, H.U.; Salman, S.; Rizvi, S.A.A.; Aurangzeb, M. Aggregation of EVs for primary frequency control of an industrial microgrid by implementing grid regulation & charger controller. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 141977–141989. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.Y.; Hussain, A.; Baek, J.W.; Kim, H.M. Optimal operation of networked microgrids for enhancing resilience using mobile electric vehicles. Energies 2021, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahnamouei, A.S.; Lotfifard, S. Enhancing Resilience of Distribution Networks by Coordinating Microgrids and Demand Response Programs in Service Restoration. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 16, 3048–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Bui, V.H.; Kim, H.M. Microgrids as a resilience resource and strategies used by microgrids for enhancing resilience. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dehghanian, P.; Alhazmi, M.; Nazemi, M. Advanced control solutions for enhanced resilience of modern power-electronic-interfaced distribution systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2019, 7, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, Z.; Ramakumar, R. Using SIRES to Enhance Resilience in Remote & Rural Communities. J. Energy Power Technol. 2021, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, L.; González, J.W.; Gutierrez, L.B.; Llanes-Santiago, O. A review on control and fault-tolerant control systems of AC/DC microgrids. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Habib, S.; Khan, N.H.; Ali, M.; Aurangzeb, M.; Ahmed, E.M. Electric Vehicles Aggregation for Frequency Control of Microgrid under Various Operation Conditions Using an Optimal Coordinated Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagarev, T. DIGILIENCE—A Platform for Digital Transformation, Cyber Security and Resilience. Inf. Secur. An. Int. J. 2019, 43, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour, K.; Nehrir, H. A Market-Based Resilient Power Management Technique for Distribution Systems with Multiple Microgrids Using a Multi-Agent System Approach. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2018, 46, 1744–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.K.; Hussain, A.; Howey, D.A.; Kim, H.-M. Limitations in Energy Management Systems: A Case Study for Resilient Interconnected Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 5675–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Rousis, A.O.; Konstantelos, I.; Strbac, G.; Jeon, J.; Kim, H.M. Impact of Uncertainties on Resilient Operation of Microgrids: A Data-Driven Approach. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 4924–14937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakiganda, A.M.; Dehghan, S.; Markovic, U.; Hug, G.; Aristidou, P. A Stochastic-Robust Approach for Resilient Microgrid Investment Planning Under Static and Transient Islanding Security Constraints. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1774–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Silva-Rodriguez, J. Resilient Operational Planning for Microgrids Against Extreme Events. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.07887. [Google Scholar]

- Moradmand, A.; Dorostian, M.; Shafai, B. Energy scheduling for residential distributed energy resources with uncertainties using model-based predictive control. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 132, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, R.; Soesanti, I. DFIG control scheme of wind power using ANFIS method in electrical power grid system. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2016, 11, 5256–5262. [Google Scholar]

- Aurangzeb, M.; Ai, X.; Hanan, M.; Jan, M.U.; Rehman, H.U.; Iqbal, S. Single Algorithm Mpso Depend Solar and Wind Mppt Control and Integrated with Fuzzy Controller for Grid Integration. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 3rd Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Changsha, China, 8–10 November 2019; pp. 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Habib, S.; Ali, M.; Shafiq, A.; Ahmed, E.M.; Khurshaid, T.; Kamel, S. The Impact of V2G Charging/Discharging Strategy on the Microgrid Environment Considering Stochastic Methods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithara, P.V.; Anand, R. Comparative analysis of different control strategies in Microgrid. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughi, M.; Hojjat, M.; Abardeh, M.H. An intelligent adaptive overcurrent protection system for an automated microgrid in islanded and grid-connected operation modes. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2020, 11, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashroum, Z.; Chaharabi, A.D.; Palmero, L.; Yasukawa, K. Establishment and Placement of a Multi-Purpose Phasor Measurement Unit to Improve Parallel State Estimation in Distribution Networks. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2021, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renduchintala, U.K.; Pang, C.; Tatikonda, K.M.; Yang, L. ANFIS-fuzzy logic based UPQC in interconnected microgrid distribution systems: Modeling, simulation and implementation. J. Eng. 2021, 2020, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekry, H.M.; Eldesouky, A.A.; Kassem, A.M.; Abdelaziz, A.Y. Power management strategy based on adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system for AC microgrid. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 192087–192100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).