Abstract

Education 4.0 and digital learning have led to a technology-driven transformation in educational methodologies and the roles of teachers, primarily at Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). From an educational standpoint, the extant literature on Education 4.0 highlights its technological features and benefits; however, there is a lack of studies that assess its impact on students’ learning outcomes. Seemingly, Education 4.0 features are taken for granted, as if the technology in itself were enough to guarantee students’ learning, self-efficacy, and engagement. Seeking to address this lack, this study describes the implications of tailoring Education 4.0 tenets and digital learning in an engineering curriculum. Four case studies conducted in the last four years with 119 students are presented, in which technologies such as digital twins, a Modular Production System (MPS), low-cost robotics, 3D printing, generative AI, machine learning, and mobile learning were integrated. With these case studies, an educational methodology with active learning, hands-on activities, and continuous teacher support was designed and deployed to foster cognitive and affective learning outcomes. A mixed-methods study was conducted, utilizing students’ grades, surveys, and semi-structured interviews to assess the approach’s impact. The outcomes suggest that including Education 4.0 tenets and digital learning can enhance discipline-based skills, creativity, self-efficacy, collaboration, and self-directed learning. These results were obtained not only via the technological features but also through the incorporation of reflective teaching that provided several educational resources and oriented the methodology for students’ learning and engagement. The results of this study can help complement the concept of Education 4.0, helping to find a student-centered approach and conceiving a balance between technology, teaching practices, and cognitive and affective learning outcomes.

1. Introduction

Education 4.0 represents a shift in education methods, including emerging technologies, digital learning, and active learning (AL) methodologies such as Project-Based Learning (PjBL), Challenge-Based Learning (CBL), gamification, and other emergent pedagogies to prepare students to cope with the issues and challenges of the 21st century, many of them related to problem-solving, ethics, collaboration, and decision-making [1,2]. Specifically, digital learning means that students and teachers draw on the advantages of diverse technologies, such as blogs, wikis, generative AI, physical and virtual labs, Augmented Reality (AR), or gamification platforms to develop discipline-based and soft skills [1,3]. The incorporation of digital tools aims to complement traditional teaching methods, which are more oriented toward practical operation and knowledge acquisition typically through lectures, and teamwork [4], removing the constraints of time and space that traditional teaching could incur [4]. The current literature reports that, with Education 4.0 and digital learning, students can develop interactive learning experiences, have unrestricted access to learning materials, enhance their learning interests, and access the latest cutting-edge Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), often referred to as digital ecosystems [2,4].

Additionally, Education 4.0 emerged alongside the Industry 4.0 concept, with its requirements in the job market for students to possess technical skills in pillar technologies such as big data, the Internet of Things (IoT), cybersecurity, cloud computing, additive manufacturing, and 3D printing, among others [5]. These technologies are used in industries, smart factories, which allow fully integrated and collaborative manufacturing systems that respond in real time to meet the changing demands and conditions [6], energy systems, e.g., solar and wind, agrivoltaics, Cyber–Physical Systems (CPSs), and the education sector [7]. Apart from the technical skills mentioned, according to the Future of Jobs Report 2025 [8], surveyed employers consider skills such as analytical thinking, flexibility, creative thinking, technological literacy, AI, and big data management crucial for the workforce.

For HEIs, Education 4.0 has meant a challenge, mainly framed in Digital Transformation (DT) and technical infrastructure. Quy et al. [9] define DT as integrating digital technologies into all sectors of an organization, leveraging technologies to change how it operates fundamentally and its business model. Among the benefits of HEIs are the prediction, planning, and control of the organization structure and human resources, improving the capacity and quality of training to create a good workforce, and changing traditional management to an information technology-based one [9,10]. Firstly, this requires investment in both new technologies and training teachers, faculty, and administrative staff in digital skills and digital literacy. Secondly, the transition toward Education 4.0 implies the modernization of curricula, teaching methods, and teachers’ roles. This is an issue because many HEIs have promoted a complete change in traditional teaching methods in a short time, even to online platforms and generative AI (GenAI), to embrace digital technologies, in some cases without enough reflection on what this means for education and what outcomes are being generated. Thirdly, regarding teachers’ roles, in Education 4.0, the literature describes the roles of a mentor, a coach, a collaborator, or a reference [1,11]. But seemingly, what is missing in those roles is the teacher as a designer of instructional methodologies that help students learn and engage in activities across the curriculum. In some cases, HEIs have opted to delegate instructional design to specific departments and not to teachers when the successful deployment of Education 4.0 depends, to a large extent, on them and not only on the technologies incorporated.

Aside from this, certain criticism arises when the educational outcomes of Education 4.0 are analyzed, e.g., in engineering, which is the scope of the present study. Currently, there is a lack of evidence-based studies synthesizing the outcomes of Education 4.0 from learning domains such as cognitive, affective, or behavioral domains among students in engineering, with some exceptions (see studies [12,13,14,15]). It seems that the advantages of Education 4.0 for learning and its enhancement are taken for granted, employing the words of Kirkwood & Price [16] concerning Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL), which is closely related to the features of Education 4.0. As concluded in the study of these authors [16], many interventions in the scope of TEL are technology-led, lacking an explicit educational rationale, and now it seems that the situation is the same with Education 4.0.

Accordingly, guided by the prior context, this study investigates the impact of incorporating Education 4.0 and digital learning in an engineering curriculum. Four case studies conducted over the last four years are described; they involved technologies such as mobile devices, low-cost robotics, 3D printing, digital twins, machine learning, GenAI, and 3D printing. Nonetheless, across these studies, several educational methodologies, such as PjBL, CBL, and mobile learning, were tailored using a common educational framework known as the Integrated Course Design Model (ICDM) [17] to create meaningful learning experiences. Afterward, the educational outcomes classified by learning domain, cognitive and affective, are analyzed through a mixed-research approach. The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze the outcomes and implications of introducing Education 4.0 into a curriculum and to observe how students’ interactions with the mentioned technologies can achieve learning enhancement and promote digital learning. Two research questions (RQs) are proposed and discussed in the study:

- RQ1. To what extent did the methodology with Education 4.0 principles develop cognitive learning outcomes among the students?

- RQ2. To what extent did the methodology with Education 4.0 principles promote affective learning outcomes among the students?

With the study results, we complement prior studies in Education 4.0 in the engineering scope, which, as mentioned, are scarce. The article is divided as follows. Section 2 presents the background and related works. Section 3 describes the method adopted from educational and research standpoints. Section 4 exposes and synthesizes the results of this multiple-case study. Section 5 addresses the discussion, which shows crucial aspects to tailoring Education 4.0 principles and technologies in the methodology, and finally, Section 6 describes the conclusions, limitations, and implications of this study.

2. Background

2.1. Related Works

Several works have been identified as prior studies in the areas of Industry 4.0, Challenge-Based Learning, the development of skills in a second language among engineering students, decision-making, and entrepreneurship. Also, some of them are reviews of skills and tech trends in Education 4.0.

Pérez-Rodriguez et al. [13] described a framework that employs CBL, PjBL, and TEL to support industrial engineering education and sustainable development for industrial solutions. The study involved several case studies with control and experimental groups to evaluate the professional competencies, comparing skills before and after the intervention in creativity and innovation, communication, collaborative work, and critical thinking. Through the intervention, the specific and transversal competencies of students increased.

Miranda et al. [1] explained the Education 4.0 core of skills and proposed, based on this analysis, three case studies employing these skills. The authors asserted that Education 4.0 seeks to personalize knowledge generation, but at the same time, there is a need for a framework to guide the design and implementation of innovative solutions in engineering programs. In addition, the study called for the incorporation of new learning methods involving pedagogical approaches such as CBL or PjBL. In this line, Coelho et al. [12] explored the incorporation of Industry 4.0 using a CBL approach and the agile Scrum methodology in civil engineering. In the methodology, six crucial pillars were identified: the adoption of the CBL methodology, the selection and acquisition of Industry 4.0 technologies, the adaptation of infrastructure to create physical laboratories, the development of virtual laboratories, the modification of curricula, aligned with Industry 4.0 requirements, and the training of teaching staff. The lessons learned in the study highlight the importance of educators’ time and preparation to count on suitable CBL evaluation rubrics and educators’ training to shift roles from lecturers to tutors. Similarly, Gutiérrez-Martinez et al. [18] analyzed the implementation of CBL in industrial engineering to adapt to the needs of Education and Industry 4.0. The study proposed a User Experience (UX) case study for industrial engineering by analyzing customers’ feelings and interactions with home automation (domotics). Students’ performance was analyzed through a rubric, which assessed the following abilities: designing and conducting experiments, analyzing and interpreting their data, identifying, formulating and solving engineering problems, and using the techniques, skills, and modern engineering tools necessary for engineering practice.

Coşkun et al. [15] proposed a generic framework to tailor engineering education to meet Industry 4.0 requirements. The framework incorporates Kolb’s experiential learning theory along with a curriculum, a laboratory with computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM), and a student club to enable students to learn Industry 4.0 concepts. The preliminary results showed that it was feasible to apply such a framework and the adopted underlying theory of Kolb to adapt engineering education to Industry 4.0.

Boltsi et al. [19] explored how digital tools and technologies such as smart sensors, AI, IoT, and 5G are shaping Education 4.0, especially for STEM fields at the university level. In addition, the study categorized open software and hardware components and highlighted trends in digital technologies applied to support smart learning environments, combining physical, remote, and virtual laboratories.

Ramirez-Mendoza et al. [20] introduced a novel curriculum for engineering education 4.0 that emphasized digital technologies that enhance industrial processes, making them more connected, reliable, and predictable. Also, the teaching–learning model involves a combination of active learning techniques, such as PjBL and Problem-Based Learning (PBL), within a real learning environment.

Concerning reviews on Education 4.0, Perez and Montoya [21] conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to analyze which Education 4.0 components are included in 21st-century skill frameworks, identifying the teaching/learning methods and key stakeholders impacted. The study found a lack of these frameworks for teachers and schools, with most oriented toward students, focusing on character, meta-learning, and linking active learning strategies to develop competencies. Similarly, Souza and Debs [22] discussed digital technologies and innovative methodologies to enhance educational quality, framed as Education 4.0. The authors analyzed 528 documents to identify themes within Education 4.0 and convergent technologies such as AI, IoT, and virtual labs, as well as active learning approaches. This study situated the teacher’s role as a tutor, providing individualized guidance and feedback. Bizami et al. [23] explored how blended learning can be made more immersive by linking three Education 4.0 pedagogies, namely heutagogy, peeragogy, and cybergogy, with tech tools like Facebook, LMS, and blogs. In this review, 59 studies were selected to analyze the relationship between pedagogical principles with the mentioned pedagogies and technological capabilities for immersive blended learning. Finally, the study [24] described the technologies enabling Industry 4.0, analyzed the required human competencies, and examined the Industry 4.0 courses and practices offered at leading engineering and technology universities. The study concluded that universities must update curricula and develop new programs to equip the future workforce with the necessary skills, balancing content, competencies, and technology in relevant educational programs.

2.2. Education 4.0, Digital Learning, and Study Motivation

As described above, the concept of Education 4.0 has been mainly driven by the skills and competencies demanded in the Industry 4.0 sector. It is difficult to establish a specific definition for Education 4.0 in the current literature since this is treated as an umbrella term with technical and educational implications. Most of the definitions situate Education 4.0 into the core skills and competencies that students should develop in the Fourth Industrial Revolution [25]. For instance, digitization and the connectivity of Cyber Physical Systems (CPSs) through technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), IoT, AI, or robotics are recurrent in diverse studies [22,24]. Additionally, Education 4.0 promotes self-learning and the development of communication skills, technological proficiency in the technologies described above, collaborative learning, innovation, and creativity, among other skills. Moreover, students can use innovative technologies, fostering both discipline-based and transversal skills (soft skills) [1,22]. Also, the instructor’s role evolves, encompassing that of a tutor who provides individualized guidance and feedback to students [22]. Usually, descriptors such as flexibility, autonomy, personalized learning, just-in-time tutoring, or adaptability are used to define Education 4.0 [1,15,22]. Regarding active learning methodologies involved with it, the current literature highlights blended learning, gamification, flipped classrooms, CBL, and PjBL [1,12,13,20]. In the case of blended learning, features such as online and face-to-face interactivity (hybrid learning) through e-learning platforms, active learning, deep learning design, and a holistic view of technology to support learning are indicated as crucial, in combination with Education 4.0, to guarantee lifelong learning [25,26].

In complement, a catalyst for Education 4.0 adoption has been Digital Transformation (DT). The importance of DT lies in the inclusion of technology advancements such as collaborative applications, emerging technologies, and cloud-based technologies to renew business models, for example, in HEIs [10], involving not only students but also faculty and administrative staff. Nonetheless, DT opens new responsibilities and roles for instructors and learners when autonomy, teamwork, and the development of digital literacy skills are encouraged [10,27]. Data collected and analyzed from the International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) 2023 [28] identified several digital literacy skills, gathered in four nuclei, namely the following: understanding computer use; gathering information, which allows one to access, evaluate, and manage information; producing information, such that students can transform and create information; and digital communication that allows students to share information and use it responsibly and safety. Complementary to digital literacy, Computational Thinking (CT) appears as a competence for which real-world problems are recognized, employing an appropriate computational formulation [21,28]. The latter studies can provide context and a starting point concerning which digital literacy skills should be fostered in students. Such skills’ development requires digital learning, which is a type of learning that occurs when students use digital tools and active learning methodologies are fostered, i.e., through the Education 4.0 tenets [2,10].

Although these prior concepts encompass what is understood as Education 4.0, a criticism has emerged because of the lack of identifying research directions, suitable teaching–learning methodologies, and the current challenges thereof [21,22]. Indeed, as has been indicated, most of the Education 4.0 features are taken for granted, as if the technologies per se were a guarantee of learning and knowledge construction, with few studies reporting outcomes from learning domains, such as cognitive, affective, or behavioral domains. In this regard, only a few studies have considered or reported affective learning outcomes that arose after the tailoring of Education 4.0 principles (see studies [21,23]). While studies reporting Education 4.0 features and possibilities for learning are needed to establish a perspective about its implications, this study complements such other studies, adding evidence directly from classrooms in engineering education and including cognitive and affective learning outcomes. So, apart from observing students’ interactions with technology and promoting them, it is necessary to understand how technologies and educational approaches in Education 4.0 impact students’ learning outcomes based on evidence, which is the primary focus of this study.

3. Method

3.1. Multiple-Case-Study Research Design

For the study, a multiple-case-study design was applied due to its robustness in providing an analysis of several case studies [29]. In this type of research, some cases are compared or contrasted, combining quantitative and qualitative methods to describe, explore, or explain an issue, phenomenon, or problem [29,30]. Then, four case studies were selected in the scope of electronics engineering and technology, and through them, an analysis explored how the applied methodology using Education 4.0 principles and technologies impacted the domains of learning, namely cognitive (academic performance, knowledge, and discipline-based skills development) and affective (motivation, engagement, and self-efficacy) domains. Additionally, we drew cross-case conclusions derived from this analysis. In each case study, a combination of mixed methods, including both quantitative and qualitative approaches, was employed to analyze the collected data, which will be discussed in the following subsections. To guarantee the replication of the study across the cases, which means that similar conditions or procedures were followed in the selected case studies [29], firstly, we employed the same educational framework known as the Integrated Course Design Model (ICDM) [17], tailoring active learning methodologies such as PBL and CBL and Education 4.0 principles, and secondly, we analyzed the same learning outcomes (cognitive and affective) with the following criteria:

- 1.

- The academic performance was measured through students’ grades in each selected case study. A student’s grade per term was composed of an exam (50%), a laboratory (35%), and a workshop (15%). For the final term in each semester, the exam was replaced with a final project or challenge. The workshops and the final project/challenge were evaluated using a rubric, described below.

- 2.

- Knowledge and discipline-based skills were identified through the observation of the artifacts and projects created by the students, surveys with closed and open-ended questions administered to students with some minor changes, and semi-structured interviews across the selected case studies.

- 3.

- Affective learning outcomes were analyzed using surveys with closed and open-ended questions that were administered to students with some minor changes and semi-structured interviews across the selected case studies.

3.2. Case Study Overview

In particular, each case study was deployed in the curriculum of a Technology in Electronics academic program at a Colombian University that lasted three years (six semesters) and focused on labor skills and competencies in the electronics field. In these technological programs, students typically learn through hands-on activities, rather than only theoretical ones. Each case study was incorporated into a course in the curriculum mentioned. Table 1 shows the name of each selected case study, the course where this was applied, the main topics in the courses, and the main areas within the scope of Industry 4.0 and ICT. The selected case studies integrate ICT and Industry 4.0 through CPS, 3D printing, robotics, Computer-Aided Design (CAD), automation, and other technologies to foster discipline-based, soft skills, self-efficacy, and engagement among students. It is important to note that the courses in which the intervention took place were divided into three terms, each lasting approximately 5 to 6 weeks, and the total duration of these terms is 16 weeks. The Education 4.0 principles and technologies were incorporated from the Second Term (ST) to contrast the performance of the students vs. the First Term (FT), where Education 4.0 was not tailored.

Table 1.

Case study overview. VHDL: Very High Speed Integrated Circuits Hardware Description Language; CPSs: Cyber–Physical Systems.

3.3. Case Studies Description

3.3.1. Case Study A: Mobile Learning to Foster Discipline-Based Skills in Introduction to Electronics

As indicated in Table 1, this case study was analyzed through an Introduction to Electronics course. This course is offered to first-semester students and encompasses topics and concepts related to electrical circuits, such as voltage, current, and Ohm’s law, among others. Additionally, students learn signal conditioning for analog sensors (temperature, humidity, etc.), simulation, and programming with hardware interaction, which is known as Physical Computing (PhyC). Through a combination of hardware and software, students can construct and experiment with tangible systems (artifacts) that sense and interact with the real world; that is the essence of PhyC [31].

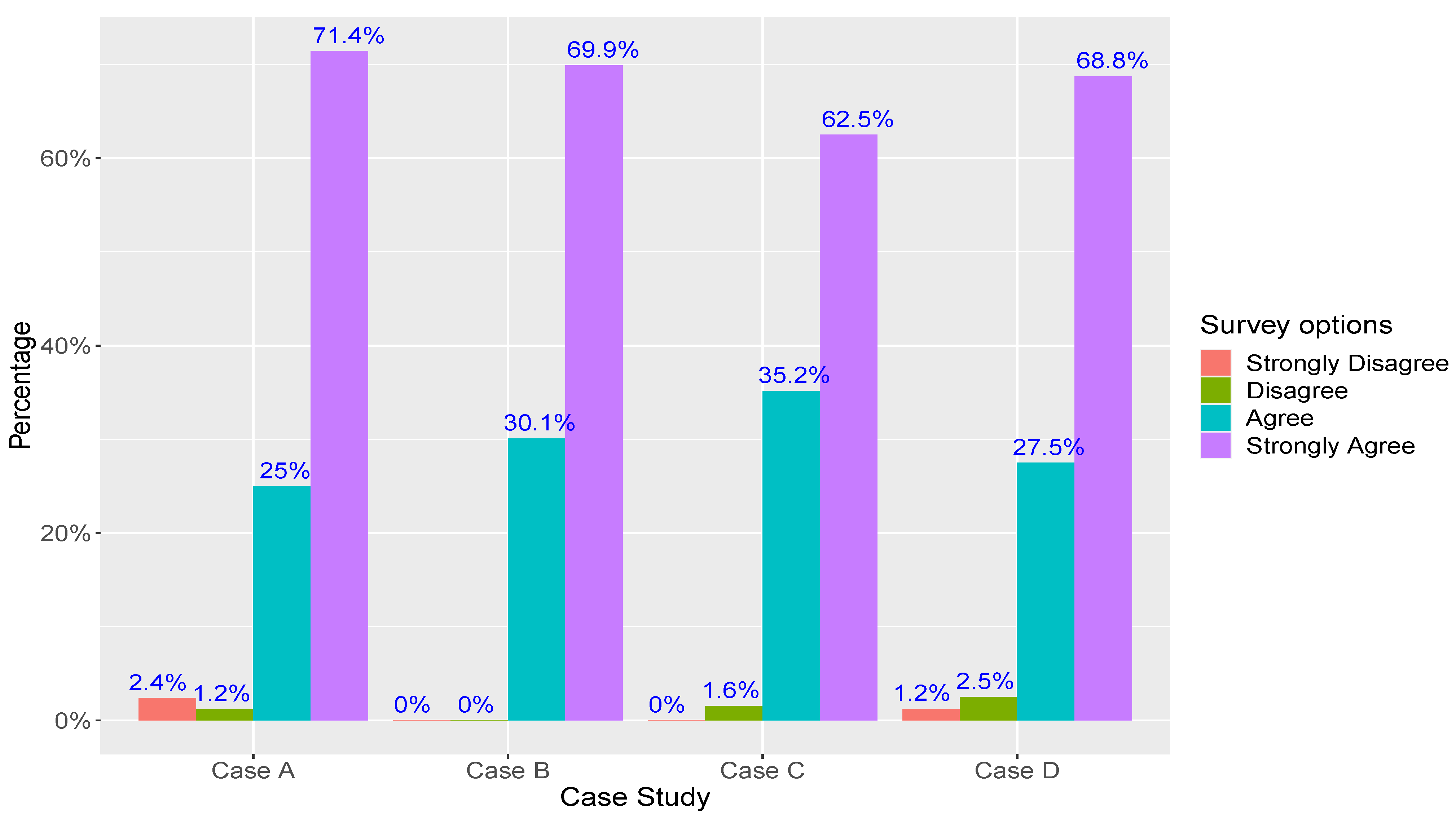

For this purpose, a mobile Android app known as EmDroid (Embedded Programming for Android was provided to students. EmDroid is a proprietary educational app developed at the university where the case studies were deployed, and it is based on the prior works [32,33,34]. The app enables students to program an Arduino-compatible development board using the Bluetooth protocol through graphical blocks, as depicted in Figure 1. Using the blocks, students can construct algorithms and interact with elements interfaced with the development board, such as a Liquid Crystal Display (LCD), IoT devices, sensors, or robots. Additionally, one purpose of the app was to provide different types of engagement to learn electronics, programming, and PhyC for students in an introductory course. Specifically, the app was combined with the topics mentioned in Table 1 to develop discipline-based skills and the practical handling of instruments, such as a multimeter, a protoboard, and a power supply. Also, students employed the app in a final project that they had to deliver at the end of the semester. This case study was deployed in two Introduction to Electronics courses during 2022–2023.

Figure 1.

EmDroid App. 1. Graphical blocks. 2. Working area to construct the algorithms. 3. Button to see C language code of the graphical blocks. 4. Main menu (program, save, graph, and connect with Bluetooth). 5. Tab with the equivalent C language for the blocks.

3.3.2. Case Study B: Robotics and Low-Cost 3D Printing in Digital Electronics

In this case study, robotics employing a line-follower robot was incorporated as a catalyst for motivation and learning in a Digital Electronics course that aimed to introduce students to both combinational and sequential digital systems, which would allow them to understand more complex architectures that can be used at the level of data processing and communication protocols. Accordingly, topics such as combinational and sequential systems, logic gates, Boolean algebra, introduction to VHDL, Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), latches, and flip flops were covered. Students in diverse careers, i.e., Electronics Technology, Systems Engineering, and Computer Technology, were enrolled in this course.

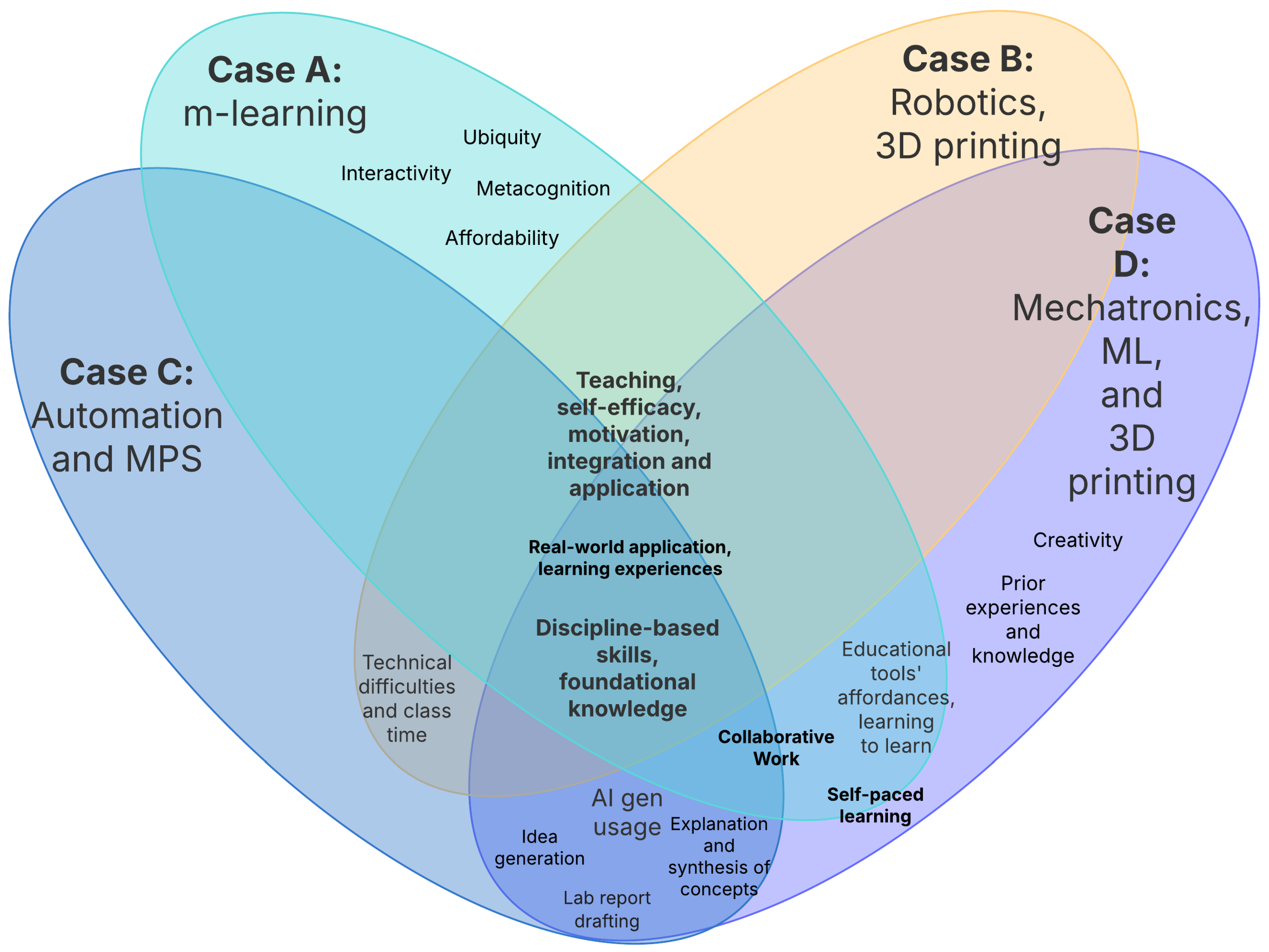

Several studies have reported the benefits of integrating robotics for students, such as increased motivation and a reduction in the gender gap in programming courses [35,36]. In addition, we included robotics because, in prior digital electronics courses, some students struggled with learning concepts and engagement. Concerning the line-follower robot, some of its parts were built using 3D printing and utilized an infrared sensor module, a DC motor controller, two DC motors, and a battery (power bank) with a total cost of 30 USD. Several robots were provided to the students in the course. With the low-cost robot and the FPGA development board Digilent Basys 2 [37] (see Figure 2), students learned and experimented with the topics and concepts throughout the course. This case study was deployed in two digital electronics courses during 2023 and 2025. Figure 2 illustrates the overall appearance of the line-follower robot.

Figure 2.

Overall appearance of the line-follower robot. (Left): 3D CAD design. (Right): final design in 3D printing utilized by students.

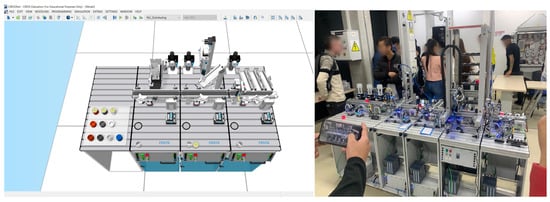

3.3.3. Case Study C: Digital Twins and Modular Production System (MPS) in Automation

This case study was implemented in an Automation course of the fifth semester, whose aim was for students to understand and analyze logic circuits in industrial automation, using PLCs as control units for basic automation processes, and understand the development of algorithms in the Ladder and AWL languages. For that, a FESTO Modular Production System (MPS) 400 [38,39] was used in conjunction with FESTO CIROS software v7.1 [40], which recreates a digital twin for the MPS components and stations. A digital twin is a mirror image that matches the operation of the physical process in real time [41]. Figure 3 depicts the MPS and CIROS software utilized by students.

Figure 3.

(Left): FESTO CIROS Software v7.1. (Right): FESTO MPS 400 with different stations.

One of the main features of the MPS is the high modularity that allows the combination of stations, modules, and accessories to create a production line tailored to specific learning objectives and scenarios. By linking the stations together, it will be possible to create an ideal learning environment for training in mechatronics and factory automation. The stations in the MPS can distribute, classify, pick and place, package, or transport products. Thus, students can interact directly with the MPS and emulate its behavior through CIROS software to perform changes in the algorithms in the Ladder and AWL languages, analyze the behavior of a production line, or test different automation routines. This case study was deployed in 2024.

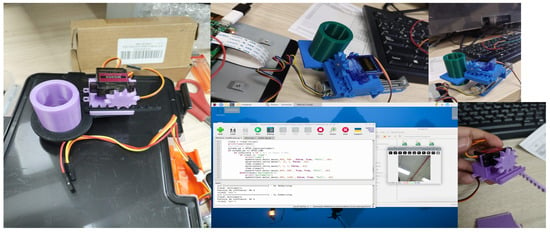

3.3.4. Case Study D: Low-Cost 3D Printing and Machine Learning in Mechatronics

This case study was deployed in a mechatronics course of the sixth semester, in which students learned about the integration of mechanical and electronic systems that usually utilize motors like DC, steppers, and servos. Typically, this course has been taught using laboratories and traditional lectures. Then, in this case study, an improvement to the curricular activities was proposed through hands-on activities involving 3D printing and basic machine learning (ML) principles to engage students more with the concepts of the course. Students modeled several mechanisms, such as gears, racks and pinions, and couplings for stepper and servo motors, first in the free and online software TinkerCAD, and afterward, these mechanisms were built using 3D printing.

With the previous procedure, students learned CAD and modeling for the mentioned mechanisms, but they also put into practice their designs, testing and controlling them by employing the Single-Board Computer (SBC) Raspberry Pi [42]. An SBC is a small computer whose main components, for example, the processor and memory, are integrated into a single system on a chip, allowing the students to interact with hardware elements such as sensors or actuators in applications that encompass computing, robotics, or machine learning [43]. In this way, students implemented control routines for stepper and servo motors, as well as algorithms for object detection in Python v3.13. As a final course challenge, they designed and implemented an automatic electromechanical classification system that, depending on the object detected, puts the object in a specific position. The challenge included well-known computer vision packages such as OpenCV, TensorFlow, and TeachableMachine [44,45]. This last package simplifies the training of machine learning models through a custom dataset (object images). In the challenge, two objects were detected and positioned. Figure 4 shows several designs made by the students and the implementation of the machine learning program in the challenge. This case study was deployed in 2025.

Figure 4.

Mechanic designs in 3D printing and machine learning program for object detection in Python v3.13 created by students.

3.4. Participants

As described, the case studies were deployed at a Colombian university in the curriculum of a Technology in Electronics program, which belongs to the engineering faculty at this university. One hundred and nineteen students participated in the case studies, and Table 2 describes their characteristics.

Table 2.

Students’ characteristics in the methodology with age (mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) in years).

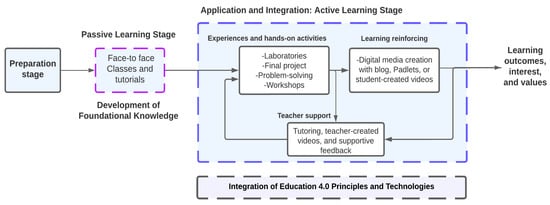

3.5. Educational Methodology

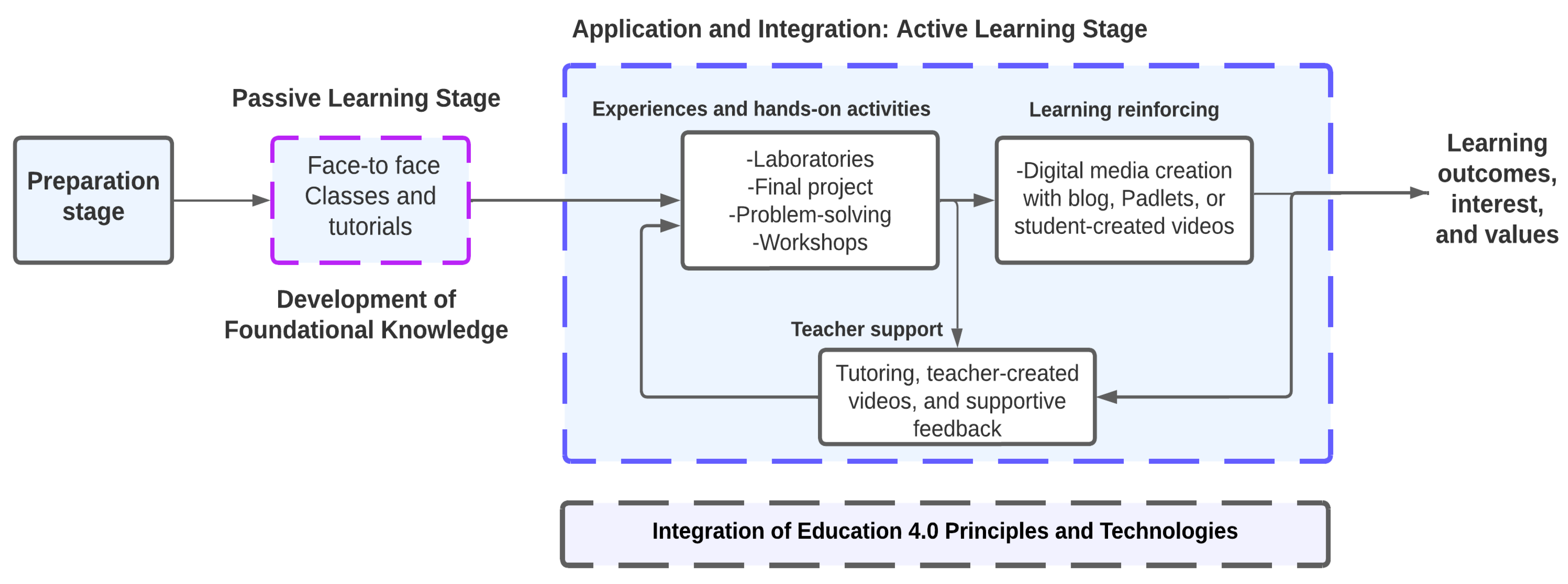

At the educational level, this study tailored the Integrated Course Design Model (ICDM) [17] that describes an approach to creating meaningful learning experiences. This model articulates three components: learning goals, teaching and learning activities, and assessment and feedback. These components must be integrated to generate significant and situated learning among students, starting from identifying how assessment would be incorporated in the courses and what learning activities are needed in this sequence. Apart from these components, ICDM provides a taxonomy to construct significant learning framed into the components of Foundational Knowledge, Application, Integration, Human Dimension, Caring, and Learning how to Learn [17]. For instance, through ICDM, students should understand and remember ideas, develop creative and critical thinking, integrate ideas in real-world projects, develop interest and feelings, and ultimately be self-directing learners [17]. Aligned with these components in this study, Figure 5 indicates the educational framework proposed.

Figure 5.

Educational framework proposed for the study aligned with ICDM.

The framework in Figure 5 is divided into passive and active learning stages. In the passive learning stage, students take their classes, understanding and remembering information about the courses, aligned with the main course objectives reported in Table 1. Afterward, to apply and integrate the foundational knowledge, students move towards an active learning stage, where they interact through hands-on activities in laboratories, a final project or challenge proposed in each course, and workshops. In these learning spaces and activities, students developed discipline-based and problem-based skills and soft skills, such as collaboration, engagement, and communication. In addition, in several courses, students were asked to construct digital media through resources such as blogs, student-created videos, and Padlets. Concerning student-created videos in assignments, laboratory reports, and even exams, students had to explain how they created a specific design with the tools and technologies in the course, i.e., a circuit, a program, a 3D model, an automation sequence, etc. The duration of these videos did not exceed 5 min. In other courses, for instance, students posted the responses to diverse activities using Padlets. A Padlet is an online and real-time collaborative visual tool that allows students and teachers to share various types of digital media, including text, images, links, videos, and documents [46]. Prior activities reinforced students’ learning in the courses (cases).

Another element depicted in Figure 5 is teacher support. This study advocates for the idea that technology in itself is not enough to orient students in learning, engagement, and the development of interests and values, which is critical for Education 4.0 and its evolution, Education 5.0. Tutoring, supportive feedback, and constructive feedback are crucial to fostering learning outcomes, and these activities are performed by teachers. Additionally, the teacher in the courses developed a set of videos for specific course topics with steps and procedures when topics were difficult to understand. For example, in Case Study D, the installation and understanding of the different libraries for machine learning was an issue, e.g., TensorFlow or OpenCV. Therefore, the course teacher created a YouTube video to address this through practical steps, testing, and debugging.

At last, this study included some Education 4.0 principles and facets in the educational framework, according to the study performed by Rienties et al. [47]. These elements comprised learning at any time, e.g., by including mobile learning (see Case Study A), PBL, hands-on activities, and different forms of assignment by means of artifact construction and the use of digital media, among others. Specifically, Case Studies A–C included PBL, and Case Study D included CBL, as active learning methodologies. All of these aspects were assessed for the development of learning outcomes (cognitive and affective), engagement, and values throughout the reported case studies. Finally, some activities in Case Studies B, C, and D were supported by incorporating GenAI to explore topics and concepts in the courses during the starting stages of development in the projects/challenge, and in the classes. For that, several prompts were provided to students with components that enhance GenAI responses, such as the role, the context, the scope, limitations, and the format output, following the prompting guidelines proposed by Eager and Brunton [48]. Some implications of incorporating GenAI into the courses will be discussed.

3.6. Research Methodology

As described above, this research is a multiple-case study [29] with a combination of mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) that investigated the impacts and implications of Education 4.0 on students’ learning outcomes. It is noteworthy that, at a quantitative level, a quasi-experiment was not possible because of the number of students in the intervention courses, which did not make it feasible to maintain a control group and an experimental group at the same time. Instead, several information resources were analyzed to respond to each research question (RQ) proposed. The way to analyze different sources of information is known as triangulation, and it allows for an enhancement of the credibility and objectivity of the study by comparing and analyzing those sources [49].

Firstly, for RQ1, the students’ academic grades over the terms in the cases were employed. The normal distribution of these grades was tested through the Shapiro–Wilk test, indicating, for most grades, a non-normal distribution (). Therefore, to contrast the students’ performance, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized. The grades in each term correspond to the main course objective (see Table 1) and the development of skills expected in the courses. Similarly, several assignments, the final projects, and the challenge were evaluated with the employment of a proficiency-based rubric divided into the following categories: Development of Foundational Knowledge; Application of Concepts and Experimentation; Design; Testing and Debugging; Communication; and Collaboration. Proficiency-based rubrics documented student performance in terms of proficiency levels on a standard and served for grading students [50]. The rubric included the levels of beginning, developing, accomplished, and exemplary. The complete rubric with its criteria is available in the supplementary section at the end of this document. Then, the academic grade of a student was computed using an exam per term, laboratories, and the indicated evaluation rubric for the assignments or the final projects/challenge.

Secondly, to complement RQ1 and answer RQ2, two surveys (learning outcomes and GenAI) were developed and administered in the case studies at the end of each semester. The first survey (learning outcomes) was divided into the following categories: Experimentation and Debugging; Development of Foundational Knowledge, and Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Collaboration. Each closed-ended question in the surveys employed a four-point Likert scale in the range of (1) strongly disagree to (2) disagree, (3) agree, and (4) strongly agree. Table 3 shows the survey’s category description and question example.

Table 3.

Category, description and question example for the survey (learning outcomes).

The survey’s categories are a combination of our own construction and other references, i.e., the engineering self-efficacy measurement [51], and the situational motivation scale (SIMS) [52]. Self-efficacy refers to personal beliefs about possessing the capabilities to cope with determined situations and obtain the desired results in these situations [53]. Self-efficacy can be a determinant for attitudes and beliefs among engineering students concerning their academic performance, motivation, engagement, and experienced anxiety [54].

For each category in this survey, because of the number of participants and responses, McDonald’s omega coefficient () was used instead of the traditional Cronbach’s alpha () to test the internal consistency of the instrument (survey). Table 4 shows the results for the () coefficient in each category and case study. McDonald’s omega coefficient () is a well-known statistical alternative to Cronbach’s alpha () based on factorial loads and is more suitable when the number of options of the survey is fewer than that of the traditional five-point Likert scale, or when the number of respondents is low [55]. As (), a value equal to or over 0.7 demonstrates good reliability of the instrument in its categories. The percentage of respondents was 84%, 87.5%, 72.72%, and 66.66% for each case study, respectively.

Table 4.

McDonald’s () coefficient in each category and Case Study A–D (–).

Unfortunately, due to the number of responses (n = 10) in Case Study D, it was not possible to calculate (). Nonetheless, information retrieved from this survey will be analyzed amid the outcomes. For each survey’s category, we synthesized its results, employing the mean (M) for the students’ responses to each option on the closed-ended questions in each case study. For instance, in Case Study A, the category of Experimentation and Debugging included four questions. Then, the mean (M) for these questions was computed to obtain an overall value for the students’ responses in the category.

The second survey (GenAI) was administered to students in some case studies (B, C, and D), and it sought to identify the students’ perceptions regarding GenAI for learning purposes. The survey comprised eleven closed-ended questions on a Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: agree, and 4: strongly agree), six multiple-choice questions, eleven yes–no questions, and two open-ended questions. The survey was divided into the categories of Exploration (identify the tools, uses, ethical issues, type of information generated via AI, and experiences of students with GenAI) and Learning and Motivation (identify whether GenAI has an influence on learning and motivation among students). These categories achieved a Cronbach’s alpha () of 0.772 and 0.776, respectively. The quantitative analysis of the students’ grades and surveys was performed using the software IBM SPSS v.27. We did not employ any special script in this software for the analysis. It should be noted that all answers provided by students were anonymous. All survey questions and their respective answers by percentage can be consulted in the Supplementary Materials.

Thirdly, a qualitative analysis was performed to contrast the prior results based on semi-structured interviews and open-ended questions in the surveys. The semi-structured interviews had a duration of between 5 and 10 min, and they were administered to some students (informants) at the end of the semester, and afterward, these were transcribed. Data from these sources (open-ended questions and transcriptions) were uploaded to the software MAXQDA v.24 [56] to perform the qualitative analysis, employing thematic analysis [57]. This technique allows for an interpretation of the manifest content of communications by conducting a rigorous analysis and considering aspects such as the completeness, homogeneity, relevance, and exclusiveness of the information [57]. Through this technique, the common themes in the interviews and open-ended questions were identified, enhancing the results provided via the previous statistical techniques. A content-driven approach was adopted to perform this analysis, allowing the themes to emerge from students’ comments, but considering some initial categories, such as those described in the survey in Table 4 and for GenAI pros, cons, usages, help-seeking preferences, and concerns from students. Both researchers extracted unit analysis (sentences) and, afterward, discussed and analyzed the emergent themes and codes from these units, which were composed of 492 sentences from the sources mentioned, obtaining initial inter-coder agreement (ICA) ( = 0.75). Both researchers discussed and analyzed the controversial codes for inclusion or exclusion. The emergent codes were gathered in a codebook that is available in the Supplementary Materials with the respective commentary examples. Table 5 describes these codes with their frequency, description, and themes. With the analysis of this information, RQ1 and RQ2 are answered and complemented. The results and discussion will be presented according to the proposed RQs.

Table 5.

Codebook constructed in the qualitative analysis for the emergent codes and themes. f: frequency.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1. To What Extent Did the Methodology with Education 4.0 Principles Develop Cognitive Learning Outcomes Among the Students?

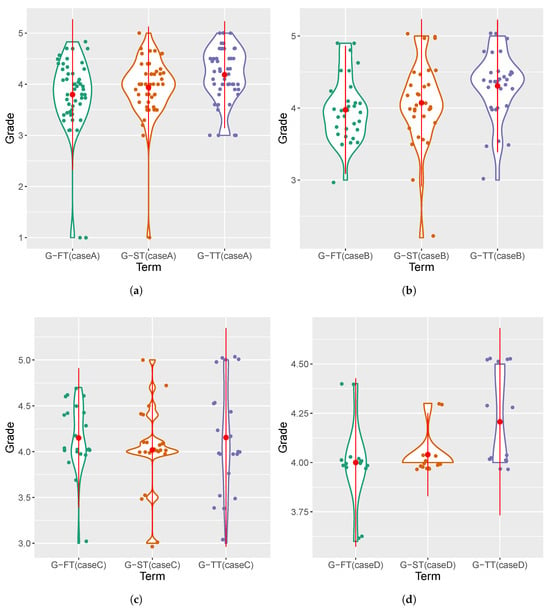

4.1.1. Academic Performance

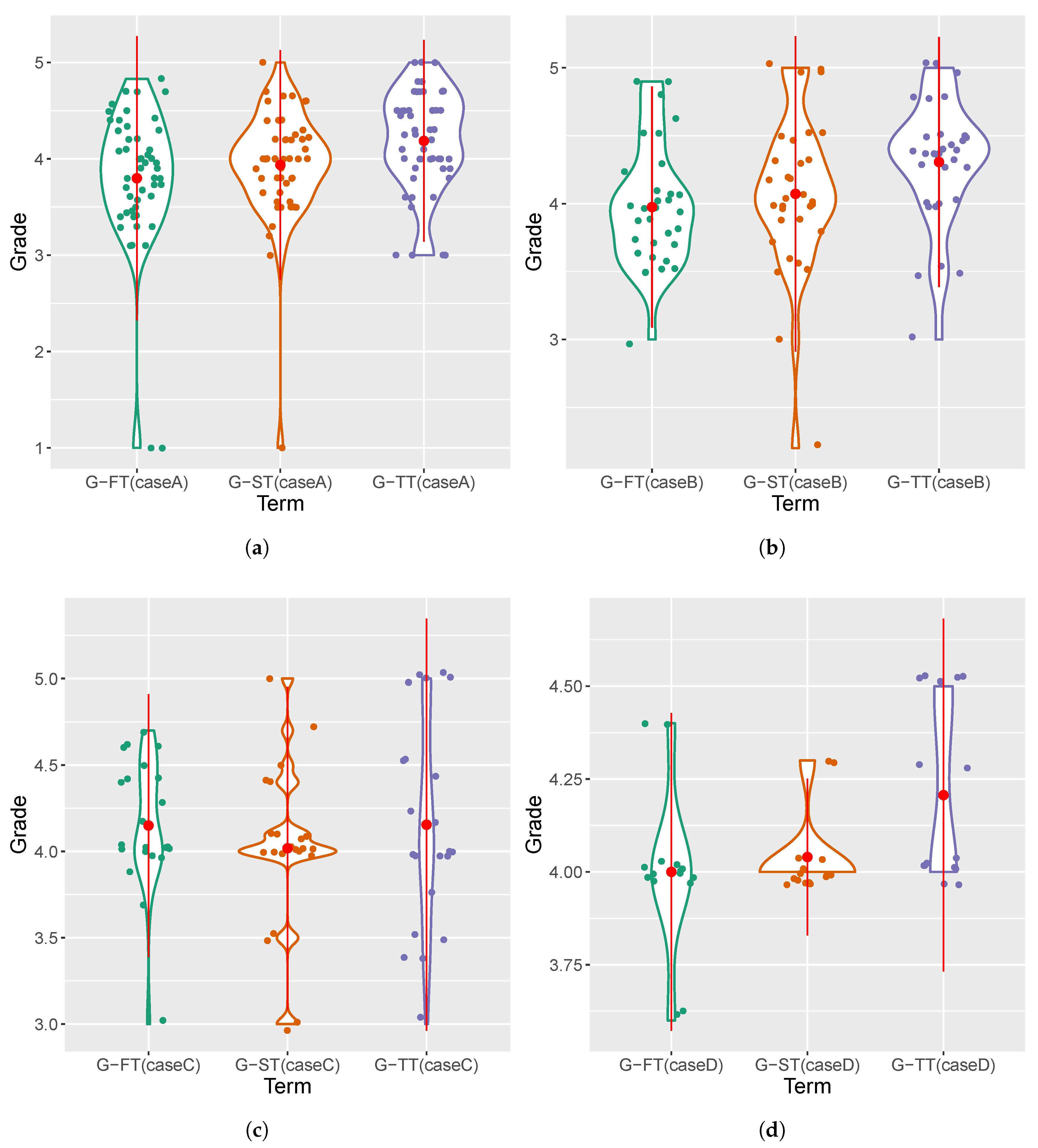

Figure 6 depicts the progress of the students’ grades in the case studies through violin plots to observe their distribution. Additionally, Table 6 describes the results for the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and their effect size (r), comparing the First Term (FT) and Third Term (TT) in each case. For most cases, , which indicates a large effect size. As indicated above, FT did not adopt any Education 4.0 principle or methodology, while ST and TT did. The progression of students’ grades shows an improvement in the academic performance between FT (without intervention) and TT (post-intervention) with Education 4.0 and the methodology (see Table 6 and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Progression of students’ grades according to each case study (a–d), respectively. FT (First Term), ST (Second Term), and TT (Third Term). Red point highlighted (mean) for each term. Grades in the range of 0–5.

Table 6.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test with effect size (r) in each case study. FT: First Term; ST: Second Term; TT: Third Term. M: mean. Grades in the range of 0–5.

However, the results for Case Study C (Digital Twins and Modular Production System (MPS)) show other behavior. In this course, there was no statistically significant change between FT and TT. Students in the course reported technical issues with the tools employed (CIROS software and TIA Portal) because they experienced multiple crashes with simulations and connections when they created their automation programs through the Ladder language and ran them in the digital twin. Nonetheless, there was an improvement in the mean between ST and TT, the latter with more grades over the maximum (5.0) (see Figure 6c). The previous behavior in all academic grades suggests that students learned and developed the discipline-based skills established in each case study with Education 4.0 and according to the main course objectives indicated in Table 1. Finally, in all case studies, the students who dropped out totaled 12 (10.08%).

As described above, these academic grades were obtained by the students through diverse tasks, which include assignments, labs, exams, and the final project or challenge. These activities were evaluated with different instruments to guarantee robustness in the assessment. Although a quasi-experiment was unfeasible because of the number of students in the courses, this increase in the academic grades responds to how students evolved in the course with the methodology, and the same pattern was observed in all case studies analyzed with different students, which evinces the impact of the methodology beyond that of a natural progression expected in the cases. Even in Case C, students experienced some issues in the academic grades, as reported, which demonstrates that the methodology influenced students’ academic performance. Nevertheless, the data in Table 6 suggest a statistically significant increase in academic grades between the FT and the TT (p < 0.05) in most cases.

4.1.2. Development of Foundational Knowledge

The Development of Foundational Knowledge (DFK) means that students acquire and properly understand the concepts and topics covered in the case studies. DFK can enhance prior knowledge acquired in other courses or through their experience, and this knowledge can be used in problem-solving or more complex activities, i.e., in a project. Sheppard et al. [58] characterized engineering work and highlighted engineering as specialized knowledge enclosed in a specific Book of Knowledge (BoK), which continually expands, evolves, and allows one to comprehend practical problems by tailoring theoretical constructs. Also, this knowledge makes engineering grow as a profession [58]. The importance of DFK in the development of engineers and technologists lies in these latter aspects.

Some question examples in the category included the following: Did the methodology developed in the course allow me to understand the concepts in the area of (…)? Did the methodology used in the course help me resolve my doubts about the concepts covered? Did the methodology strengthen my mathematical knowledge in handling equations, scientific notation, problem solving, etc.? Through 3D modeling with TinkerCAD, did you apply the concepts of pinion design, pinion-rack, and motor control (servo and stepper)? Did working on the project allow me to research concepts and tools beyond those normally covered in class?

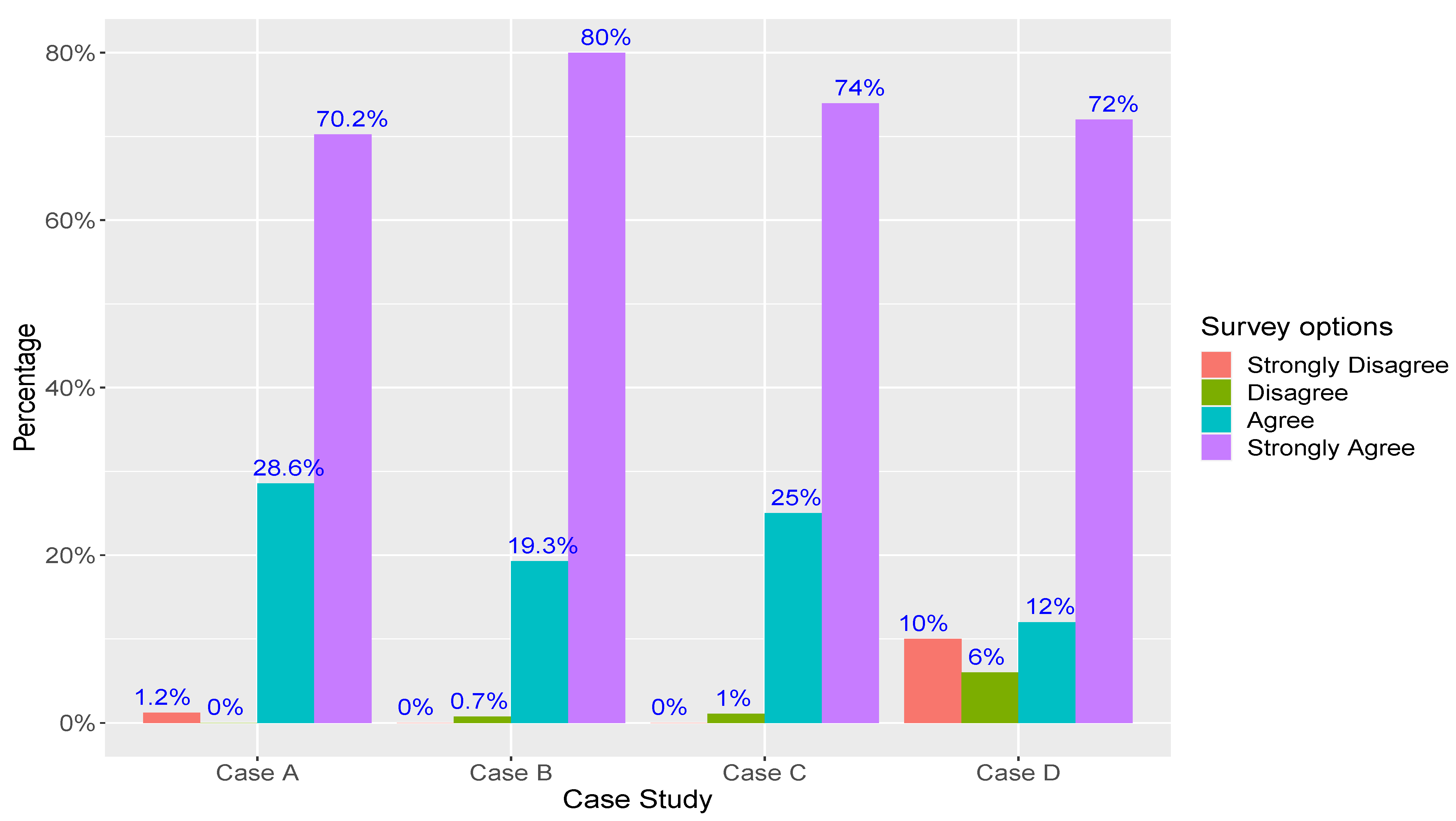

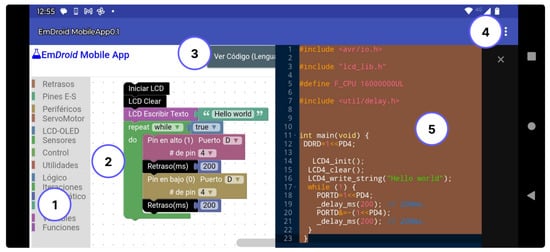

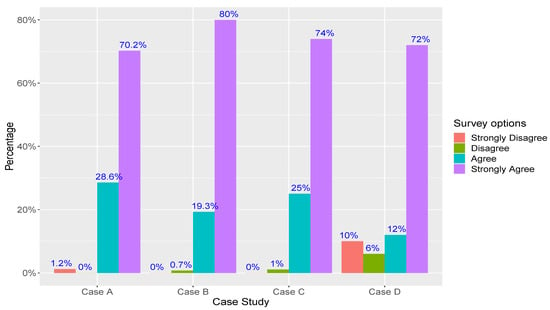

These surveys’ questions were designed to identify whether students developed foundational knowledge, which includes electric, automation, mechatronic, and digital systems concepts. Figure 7 depicts the survey’s responses distribution regarding DFK in all case studies; most of the students agreed or strongly agreed regarding DFK through the methodology, encompassing Education 4.0 tenets. The best result was obtained in Case Study B (Digital Electronics), with 80% of students strongly agreeing. Finally, students who disagreed or strongly disagreed totaled less than (n = 3) per case study.

Figure 7.

Comparison of students’ survey responses in the category Development of Foundational Knowledge.

At a qualitative level, students shared some comments that indicate DFK as follows. (S: student; C (A, B, C, D): case study):

-(): "I learned how to build circuits, program using blocks, check for errors, and analyze missing electrical components.” (): "In TinkerCAD, there is no template for the pinion gear, so you have to create it step by step. The teacher taught us how to calculate each tooth, the degrees of inclination, and the pitch diameters. (…)". (): "I learned more about cylinders and valves, how such a simple component as air can achieve so many things in automation, and deepened my knowledge of Ladder programming.”

Regarding prior knowledge developed in classes that can shape the way to understand new concepts, some students reported the following:

-(): “(…) If you have a foundation (base), you can’t rely on anything more intuitive. What you learn in class will always be an important and fundamental basis for creating simpler or more elaborate shapes when designing in 3D.” (): “There was one subject in which we saw something, but only very briefly. This past semester, we had the opportunity to learn more in depth how the pieces could be made, and we gained theoretical knowledge.”

These comments suggest that students highlighted the importance of developing foundational knowledge and constructed it with the help of the educational resources provided. The verbs and words in bold, like learn, create, analyze, or check, provide a guide to understanding DFK among students. These words acted as cues to recognize DFK.

4.1.3. Experimentation and Debugging

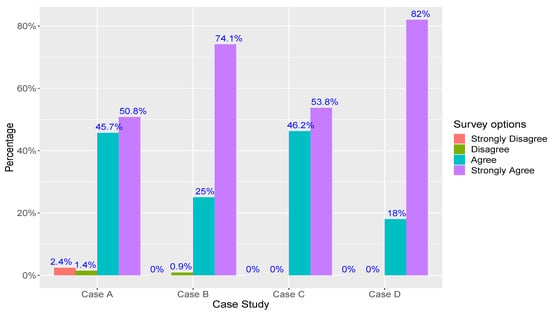

One of the crucial points in Education 4.0 is to provide students with significant learning experiences. Therefore, learning-by-doing, hands-on activities, and debugging practices were prioritized in the methodology, and students analyzed the causes for their errors in design and implementation to understand their implications. In particular, failures and errors performed by students in the activities throughout the case studies were seen as possibilities to improve their learning processes. Similarly to DFK, between 96.5% and 100% of students agreed and strongly agreed with questions surrounding how the methodology allowed them to achieve the application and integration of learned topics and concepts. Students who disagreed or strongly disagreed were below (n = 5), and in some case studies (C, D), no students disagreed. Figure 8 shows the distribution of the survey’s responses in this category. Some questions that students asked included the following: Can I identify errors in hardware and software and fix them so that an algorithm has the functionality I want? Can I identify errors in hardware and software and fix them so that an algorithm has the functionality I want? Through different iterations (trial and error), was I able to improve the design of the mechanical parts for the final project? With the final project, can you integrate and apply the knowledge you have learned in the course?

Figure 8.

Comparison of students’ survey responses in the category Experimentation and Debugging.

Concerning how the methodology influenced Experimentation and Debugging, some students asserted the following:

-(): “It’s a very good methodology because the assignments they give you make you put into practice absolutely everything they explain in class.” (): “The methodology was clear and educational, allowing for easy learning and application of the concepts.” (): “I think it’s very good because there’s no better way to learn than by putting what you’re doing into practice.” (): “The methodology was very useful, as it combines theory, practice, and teamwork, making the class more dynamic and enjoyable. You understand the subject a little better.”

Experimentation and Debugging helped promote creativity, specifically in Case Studies A and D with the integration of 3D printing and m-learning. Additionally, students reported that the way to put into practice the concepts in real-world applications is a relevant feature. Some students commented the following:

-(): “3D printing offers the possibility of creating many things, and the only limits are our imagination and our ability to do so. 3D printing is incredible for so many things. It’s interesting to see how capable we are of creating objects and how far our imagination can take us.” (): “I really liked the platform, and it motivated me, in the sense that you can do so many things with it. When you start learning more basic things, you realize that the only limit is your imagination.” (): “You retain much more information when you do the activities this way because, if you stick to the simulation, to the theory, in the end you won’t be able to apply it in real-world applications.”

Regarding these comments, it is essential to note that Education 4.0 involves a central technology-driven component. As Herschbach [59] pointed out, students must interact with technology through activity, such as experimenting and debugging. This activity helps students perceive, understand, and assign meaning, making explicit to the student how knowledge is generated. For this reason, experimentation and debugging constitute a way in which students can extend the usage of foundational knowledge, and they can make sense (meaning) of it. Additionally, integration that gathers theory and practice through problem-solving is another crucial element in engineering work, apart from being specialized knowledge [58]. Thus, similar to DFK, the words and phrases in bold, such as learning-by-doing, practice, apply, imagination, or real-world, indicate that students put into practice the concepts learned through hands-on activities and experimentation with real-world problems, generating sense and utility concerning the foundational knowledge developed in the case studies.

4.1.4. Learning to Learn, Self-Directed Learning, and Metacognition

Some of the segments coded in the semi-structured interviews and open-ended questions reveal some self-directed learning and metacognition facets (see the codebook in Table 5); students were aware of their learning process, exploring the affordances of the technologies that were tailored and experimenting in other spaces that differed from classrooms or laboratories, e.g., in homes. For instance, some students stated the following:

-(): “The more you interact with the platform and do exercises, the easier it will be to remember and acquire the knowledge to use the platform.” (): “I didn’t just take the time during class, but I also continued practicing at home, and that helped me not find the topics in class so difficult”.

Moreover, some students’ comments indicate how knowledge and discipline-based skills were developed, and technology affordances fostered more self-directed learning:

-(): “This type of application not only allows you to consolidate your knowledge, but also to explore the different tools available in the application on your own.” (): “I thought the course methodology was very good because, by integrating the classes that are taken into account in a week, it also integrates our ability to learn on our own”. (): “I think everything we saw will be useful for future projects. I feel that many of us got ideas that we can use in the long term”.

For instance, in Case A (m-learning), students had the opportunity to interact with the app and the development board directly from their homes (ubiquitous learning), which helped to strengthen their educational process. This fact is crucial when students are full-time workers, as the participants in this study were. Nonetheless, metacognitive traits were unexpected since the methodology sought to develop only cognitive and affective learning outcomes because of time constraints in the courses. Accordingly, creating significant learning experiences can fulfill metacognition traits because students were not only concerned about their grades; they were concerned about their learning paths.

4.1.5. Generative AI Usages and Preferences

Generative AI (GenAI) was employed in case studies (B, C, D) in 2024–2025. This usage was included in RQ1 since students employed GenAI as an assistant in diverse tasks, such as the explanation of concepts and topics, synthesizing information, generating ideas and debate, and problem-solving, among others. No restriction to a specific GenAI tool was indicated to students. The following information illustrates several preferences and usages when students employ GenAI. Specifically, N = 47 students answered the questions regarding GenAI usages and preferences in the case studies indicated above.

Firstly, students combined GenAI for several purposes, as follows: 89.4% indicated that they used GenAI for the explanation of concepts and topics, 57.4% for synthesizing information, 40.4% for generating ideas in problem-solving tasks, 36.2% for assisting in course assignments, 25.5% for designing analog circuits, 14.9% for guiding in the implementation of electronic systems, and 6.4% for generating ideas in debate activities.

Secondly, ChatGPT was the most employed GenAI Tool, with 85.11% of students using it, followed by Google Gemini (55.32%) and specialized AI chatbots (42.55%), which were designed and provided to assist students in the case studies through specific instructions, considering the roles, contexts, and format output in the prompts, following the guidelines proposed by Eager & Brunton [48].

Thirdly, regarding help-seeking preferences, students preferred a traditional approach, consulting the teacher directly to resolve their doubts (64.64%), followed by Gen AI (16.7%), the Internet (14.6%), and peers (4.20%). Nonetheless, students indicated that this approach depends on how open the teacher is about acknowledging and solving their doubts; otherwise, students searched other sources, such as GenAI or the Internet.

Fourthly, students expressed in the survey’s comments with frequency (f) that one of the main concerns when using GenAI is the over-reliance (f = 15) that GenAI could bring into the learning process. Several students described the following: S2. “If you have no knowledge of the subject, AIs create a dependency to use them, with the risk of plagiarism, besides the fact that on many occasions the information provided by the AI is not completely truthful”, S38. “A negative aspect is becoming dependent and procrastinating by using AIs too much, waiting for it to do a job for you from scratch, and not even being interested in learning from it or how it was solved”. Similarly, some students described how the overuse of and over-reliance on GenAI can diminish critical thinking (f = 4). Some comments were as follows: S42. “AI could influence lack of critical thinking, diminished social skills, and dehumanization of the learning experience”, S44. “One risk of AI is that they use it only to do class assignments, without even sitting down to understand what it is doing”.

Finally, students indicated as positive aspects of GenAI the possibility of idea generation, personalized learning, doubt clarification with instant feedback, reinforcement learning, and quick access to information, with a predominance of this last (f = 20). In that regard, students reported the following: S15. “AI reduces time by helping to better manage information, and it allows for better organization of concepts”, S4. “It reduces my time, and I can be more productive in my career”, S41. “Versatility, speed of information, which reduces research time”. In the case of Personalized Learning (f = 9), the students’ comments were: S37. “AI-based resources are available 24 h a day, allowing students to learn on their own schedule. And besides that, it takes some of the workload off the teachers as they don’t just have to attend to us, they have to do more things for us”. Another student commented as follows: S38. “AIs help you to better understand new concepts or concepts explained in class, which is a great help when something is not quite clear”.

4.2. RQ2. To What Extent Did the Methodology with Education 4.0 Principles Promote Affective Learning Outcomes Among the Students?

To start the discussion of this RQ, firstly, it is worth mentioning that promoting and developing affective learning outcomes is a distinctive aspect of this study. It had been observed in the reviews and works in the background section that the priority of Education 4.0 interventions is cognitive learning outcomes and technology [19,22,24], and only a few studies have remarked on affective learning outcomes implications [4,21,23].

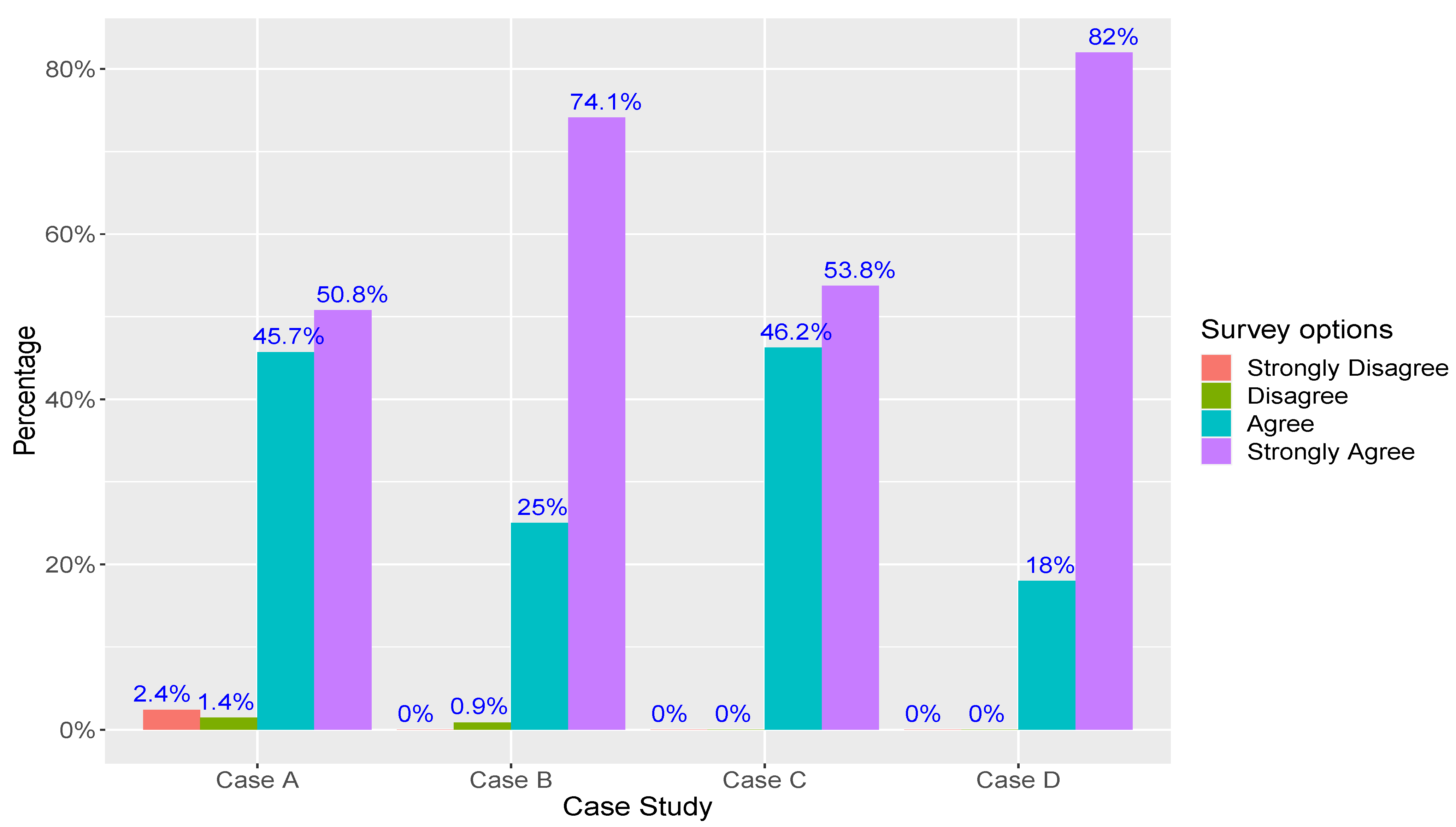

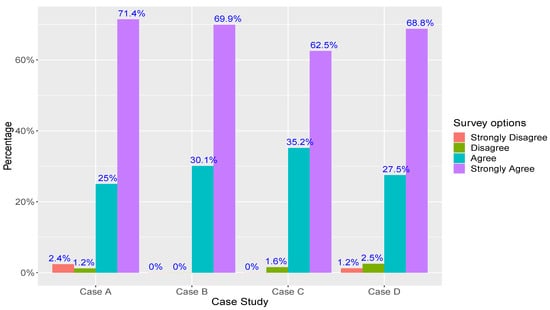

At a quantitative level, Figure 9 shows the results of the survey administered to students for the categories of Self-Efficacy, Motivation, and Teamwork. Some questions asked of students included the following: Comparing my skills at the beginning of the course and at the end of the course, do I think they improved with the course methodology? Do I consider my performance in the subject to have been good? Do I believe that the skills I developed during the course helped me solve problems in the field of electronics? Did the course methodology help me reduce my nervousness when handing in a quiz, midterm, lab, etc.?

Figure 9.

Comparison of students’ survey responses in the categories of Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Collaboration.

In Figure 9, between 96.3% and 100% of students agreed or strongly agreed with questions concerning the development or improvement of self-efficacy, motivation, and collaboration. For example, with the question Comparing my skills at the beginning of the course and at the end of the course, do I think they improved with the course methodology?, 100% of students agreed or strongly agreed. Likewise, the same distribution was associated with the questions about whether the course methodology helped reduce nervousness and anxiety when students performed midterms, labs, etc., and whether students considered their performance good in the courses, improving their skills.

The quantitative and qualitative outcomes suggest the development and improvement of self-efficacy in the case studies. For instance, students considered their academic performance good during the case studies, and by interacting with hands-on activities, the students gained confidence in experimentation. This confidence has a close relationship with the debugging practices mentioned in RQ1. The concept of self-efficacy or perceived self-efficacy was coined by Bandura [53], who described it as the belief in one’s capability to act in order to achieve a specific goal. Self-efficacy has several sources, such as enactive mastery experiences, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and physiological and affective states [53]. Concerning enactive mastery experiences, people reinforce their perceptions by overcoming situations that are normally generated in everyday life. According to the interpretation of success or failure, the person could achieve better or worse performance in the activities. Hence, the methodology of this study sought to help students make and identify their errors, and through this process, students experienced reflection and critical thinking. Technologies such as 3D printing or the mobile app allowed students to construct diverse prototypes and test and debug them for learning purposes. Some students indicated the following in this regard:

-(): “There was little space for error, so it did help me feel more confident about doing the assemblies.” (): “I think the platform helped me improve my assembly and programming skills. I made mistakes at first, but once I linked the software configuration in the application to the hardware, it was easier to spot the errors”.

In these comments, students indicated that, at the beginning of the process, catching errors was a difficult issue, but as the courses advanced and with learning and interaction, the errors were identified and solved easily. Thus, students were more confident about their skills in the case studies, which, as mentioned above, is a feature of self-efficacy. A student reported the following:

-(): "(…) it motivated us quite a bit. I believe that you understand more through practice and not just through theoretical explanations. You pay more attention to the explanation by interacting, connecting, etc. This motivated us to attend classes more and put more effort into making the circuits".

Another aspect of self-efficacy is that it has an influence on cognitive, affective, and motivational processes [53]. Relatedly, several students pointed out feelings like happiness or enjoyment about the process that served as a catalyst for curiosity and interest in the courses:

-(): "Apart from that, it was really good to do those practices, understand more, program more, and feel the joy of seeing the mechanism move and start detecting images". (): "So, I did find it quite interesting, and if it were possible to work with other things, the Raspberry Pi with other detection or movement elements". (): "Yes, I found the tools very interesting. I didn’t know about OpenCV and Raspberry Pi, and the Teachable Machine image recognition tool was cool". (): "The methodology was very good. I learned a lot, and the subject matter was very enjoyable".

Self-efficacy can be a trigger for curiosity and creativity because people who are confident in their own capabilities can generate effective novelty [60]. This type of self-efficacy is known as creative self-efficacy (CSE) [60], and it should receive attention since STEM fields, such as engineering, are seen by students as difficult and offer fewer possibilities for being creative [60,61]. Another type of self-efficacy that can explain some negative issues with Case C is technological self-efficacy, which is students’ perception of their capabilities in using technology for learning purposes [62]. As Figure 9 depicts, the students who strongly agreed in Case C totaled 62.5%, which is the lowest value of the four cases. The issues that students dealt with when using the digital twin influenced the affective learning outcomes, especially engagement, because students could not deliver all tasks on time in the course, and the anxiety levels were high for some students due to these issues. Therefore, the usability and affordability of technologies should be revisited to avoid some of the mentioned issues.

In the case of verbal persuasion as a source of self-efficacy, teacher support could contribute to reinforcing it in the courses. The factor of Teaching will be discussed in the next section, along with other factors that influenced the results presented. Finally, students considered the methodology to have allowed collaboration and teamwork, and these results illustrate that affective learning outcomes were developed with Education 4.0 principles and the methodology deployed in the case studies.

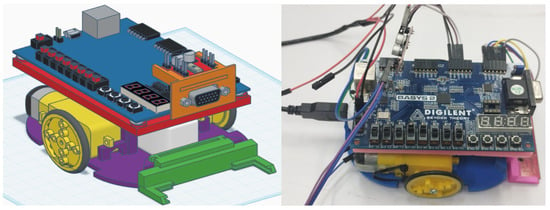

5. Discussion

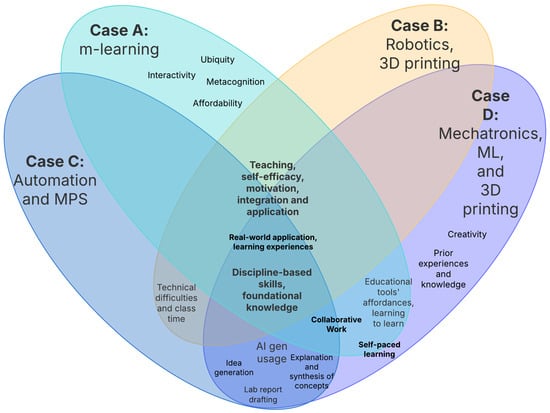

Several factors were identified as crucial in the deployment of Education 4.0 and digital learning in the case studies, and they complement the related works described above. Figure 10 shows the intersection and factors per case study. At its center, several factors identified or developed in the case studies are essential, including teaching, self-efficacy, motivation, and the integration and application of foundational knowledge to develop discipline-based skills. Similarly, in the intersection between case studies, there were shared factors, for instance, in Cases A and D, educational tools’ affordances, learning to learn, or collaborative work. The discussion of the main factors in Figure 10 follows.

Figure 10.

Main factors for Education 4.0 and digital learning identified in the case studies.

In all case studies, discipline-based skills and foundational knowledge, as well as motivation, self-efficacy, integration, and the application of concepts, were encouraged, the latter by means of real-world applications and experiences in the cases. Continuous experimentation and the application of concepts through hands-on activities and active learning methodologies benefited learning, as was mentioned several times by students. Specifically, it was tailored to the cases, debugging pedagogy [63] in combination with productive failure (PF) [64]. Both approaches seek to observe failure as an opportunity for learning and not only as an error that must be assessed negatively. From a constructivist standpoint, PF allows for the improvement of the zone of proximal development (ZPD), which is the gap between what a student can do without assistance (self-directed) and with assistance and support from the teacher [65]. While most of the teaching activities rely on scaffolding, reducing the likelihood of errors, PF allows students to fail with the aim of strengthening problem-solving and analytical skills. These approaches fostered both affective and cognitive learning outcomes, as described through diverse hands-on and AL activities created in the cases analyzed.

Another crucial factor is teaching, which was mentioned repeatedly by students across the case studies. Students recognized the form of teaching (didactic) and the way to provide different educational resources via the teacher, which included teacher-created videos, Padlets, and activities assisted via GenAI. This proves that not only are the technologies included in Education 4.0 and digital learning in themselves guarantees of learning, but also, teachers’ accompaniment and support are key to orienting their proper usage and guiding the educational process. As indicated above, many studies on Education 4.0 rely on the technologies employed, exacerbating their technical features, and not on the pedagogical aspects of these technologies. Our sociocultural approach in this study was to observe technologies as artifacts that can be transformed into learning instruments through proper activity and appropriation by students. In this case, as Sutherland et al. [66] pointed out, the instrument was an artifact that a particular user (student) could employ for different tasks over a sustained period of time. The usages, meanings, and experiences that students construct with those instruments rely on the activities and practices through which students interact, which are orchestrated via the teacher’s planning.

Aside from this, some technologies’ features and affordances foster the development of cognitive and affective learning outcomes more than others. As Figure 10 shows, Case A (m-learning) fostered some metacognitive facets due to the ubiquity and affordability of the app mentioned, which are features often referred to as m-learning in the literature [67,68,69]. Nonetheless, we explored other scopes of m-learning for direct experimentation and not only for content delivery, which typically has been the main purpose of m-learning. This could be considered a novel aspect in the methodology. In Case D, creativity was promoted via 3D printing and CAD (TinkerCAD) because students freely created their designs for the problems that were proposed. Some studies have stated that the usage of these tools can enable students to explore creative ways to solve unexpected situations and can also serve as drivers for self-directed learning [70,71]. Additionally, 3D printing is viewed as a 21st-century digital learning skill [70].

For GenAI, students employ these tools mainly for idea generation, lab report drafting, and the explanation and synthesis of concepts. But whereas students explore these usages, they stated the problems of over-reliance, a lack of critical thinking, and an increase in procrastination behaviors to deliver assignments in courses that come up after GenAI utilization. The main part of the usages mentioned above falls into request tasks and not, e.g., the case of assigning the roles of teacher or evaluator to GenAI, which could assess a student’s knowledge in a particular course, or in the case of assisting in the design of a project, etc. Other ways of incorporating GenAI, apart from only requests, should be explored, especially to strengthen critical thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving skills. Prior findings are aligned with other studies in engineering education and AI [72,73,74].

Students in Cases A and D reported that collaborative work was fostered in the methodology. Nevertheless, in other cases, for instance, Case A, this was not explored since students could experiment directly from their homes. This suggests that certain technologies could promote or hinder collaborative learning in classrooms, even when this is encouraged by the teacher. So, in Case C, the digital twin integration and the technical issues derived from this employment could have hindered the link between collaboration, learning, and motivation; conversely, in Case D, the usage of 3D printing fostered collaboration, cognitive, and affective learning outcomes. Particularly, in Case C, the affordability and performance of the technologies used (digital twin) had an influence on academic performance and affective learning outcomes, which is consistent with prior studies on technology usability [75], and technological self-efficacy [62]. In Case D, the creation of physical artifacts through 3D printing allowed students to put forward their creativity and skills developed in the course, which is consistent with prior studies on robotics and physical computing as catalysts for learning and engagement [34,76].

Finally, our contribution through the analysis of the case studies indicates several factors that should be revisited when researchers or educators develop methodologies for Education 4.0, as explored above. We recommend that, at the same level that cognitive learning outcomes are fostered, affective learning outcomes should also be developed. Without this balance and a critical view of teaching and technology, Education 4.0 methodologies could be meaningless.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications for Practice

This study investigated the cognitive and affective learning outcomes of integrating Education 4.0 tenets and digital learning in four engineering case studies deployed over four years. In the study, several cutting-edge technologies were incorporated, such as 3D printing, MPS, robotics, 3D printing, and machine learning, emphasizing their educational benefits and the teacher’s role in guiding their proper usage to foster discipline and soft-based skills. Also, the study was performed to analyze the implications of Education 4.0 based on the evidence because, in the extant literature, there is a lack of studies synthesizing its educational outcomes from a reflective standpoint, beyond only promoting the technological advantages of Education 4.0 and digital learning.

The evidence in this study suggests that the tenets of Education 4.0 can encourage participation and engagement among students due not only to the technologies included but also the curricular design that integrates them and promotes teacher support, learning resources, continuous experimentation, and concept application and integration. In this sense, this study complements prior studies on Education 4.0 and digital learning, adding the possibility of fostering cognitive and affective factors, such as self-efficacy, motivation, collaboration, and meaningful learning experiences. A limitation is that this study cannot suggest generalizations because the case studies responded to a particular context with some socio-economic constraints. For example, HEIs with a better technical infrastructure can incorporate other types of technologies in curricula and observe the effects on learning outcomes. Also, universities whose student populations are not full-time working students can obtain other results. Nonetheless, our interest focused on identifying and analyzing specific or shared factors in the case studies that arose after Education 4.0 and digital learning were included. Likewise, in the analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, we did not exclude a certain subjectivity load according to our experience and beliefs as educators. Nonetheless, we employed some rigorous techniques to limit this issue as much as possible. We did not notice any trait of the Hawthorne effect since students participated openly in each case study, and they were evaluated with different instruments to guarantee robustness. In addition, the same teacher evaluated the courses to avoid biases in the method used to assess students’ learning outcomes. Regarding students’ reported grades, we observed an increasing pattern in the courses with the AL methodologies, even though we do not discard the possibility that students gained familiarity with the assessment process, but this does not detract from the results presented.

Finally, the results described above can serve in part to improve the conception of Education 4.0 and even Education 5.0, helping to find a student-centered approach and achieve a balance between technology, teaching practices, and learning outcomes. This can be crucial, i.e., considering the human-centric model tailored to Education 5.0 and the current evolution of Education 4.0, as well as teachers’ role as not only facilitators or tutors in the learning process but also designers of meaningful learning experiences.

Supplementary Materials