This discussion synthesizes the comparative findings from all evaluated models, focusing on learning dynamics, generalization patterns, and the interpretability of model performance across internal and external splits.

4.1. Key Observations and Takeaways

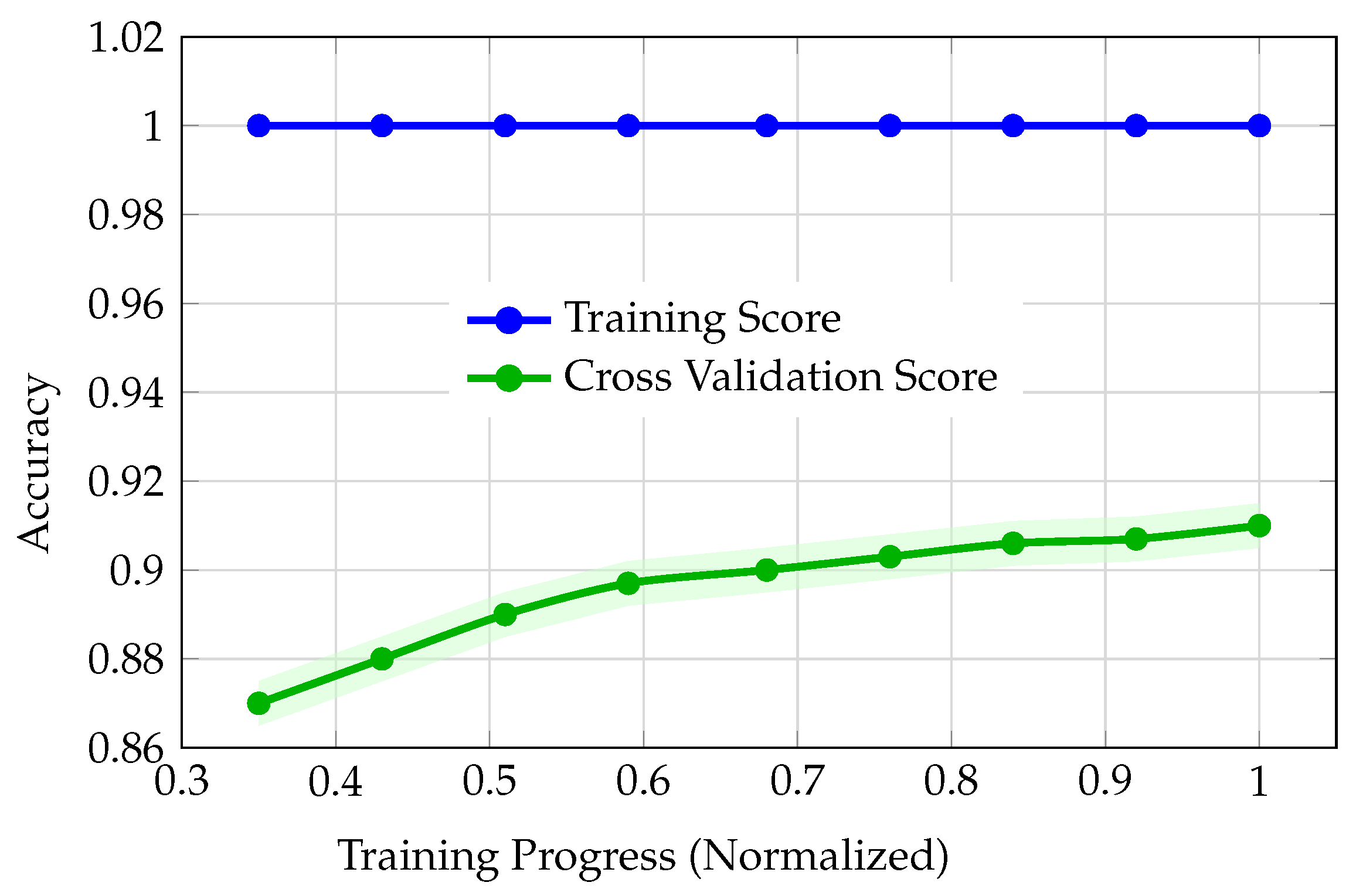

The comparative analysis of model performance across LightGBM (via PyCaret), regular CNN, augmented CNN, and DNN reveals distinct patterns in learning dynamics and generalization behavior. Although LightGBM achieved a strong cross-validation score (best CV accuracy: 91.0%), its learning curves (

Figure 3) exposed problematic training dynamics. The training accuracy remained at 100% throughout, while cross-validation accuracy improved only marginally from 87.0% to 91.0%, with a persistent and widening gap between training and validation. This divergence, coupled with early stagnation of the validation curve, is indicative of overfitting or possible data leakage. Such behavior undermines confidence in the model’s ability to generalize, justifying the decision not to advance PyCaret models to external validation. The regular (unaugmented) CNN also exhibited severe overfitting (

Figure 5). Training accuracy rapidly saturated at 100%, while validation accuracy plateaued at 79%, resulting in a substantial 21-point gap. The validation curve also displayed instability, with fluctuations and a notable dip around epoch 8, further signaling poor generalization and memorization of the training set rather than learning robust features.

In contrast, the augmented CNN demonstrated healthier learning dynamics. Both training and validation accuracies started at realistic baselines (47%) and converged smoothly, with the validation curve closely tracking the training curve and ending at 84.5% (validation) versus 86% (training). This small, expected gap, where training accuracy remains slightly higher than validation accuracy, reflects robust generalization and effective regularization. Overall, the augmented CNN’s learning curves were markedly better than both LightGBM and the regular CNN. The DNN’s learning curves (

Figure 4) also showed smooth, parallel convergence of training and validation accuracy, with no abrupt divergence. Accuracy improved steadily from 37% to 80% (training) and from 29% to 75% (validation) over the training size.

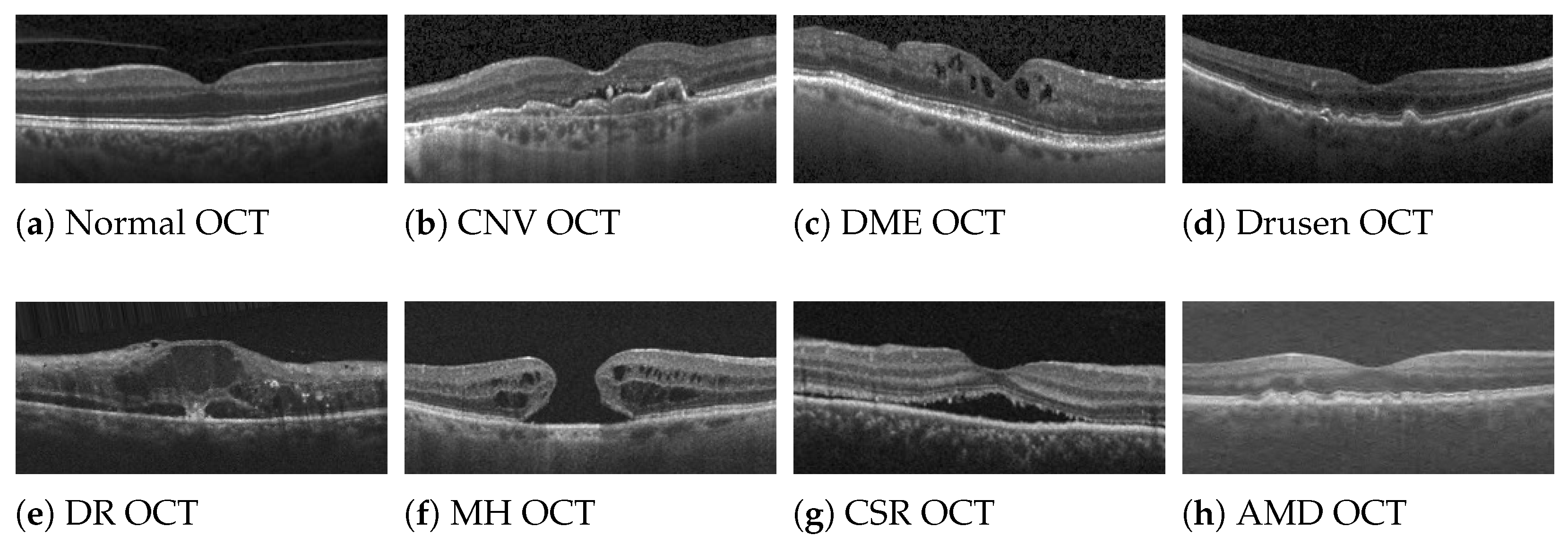

Confusion matrices (

Figure 6) revealed that most errors were concentrated among classes 2, 4, and 6, with notable off-diagonal confusion, especially for class 4, which had substantial misclassification into classes 2, 6, and 8. This pattern may reflect clinical or feature overlap among these categories.

When examining performance across splits (

Figure 7), the DNN was the only model to exhibit the expected monotonic decrease in most performance metrics from training to validation to test to external. The only exception was precision, which increased on the external set; likely reflecting a more conservative prediction strategy in response to distributional shift, where the model made fewer positive predictions but with higher accuracy. In contrast, the augmented CNN showed non-monotonic improvement, with external set metrics (e.g., accuracy up to 90.5%, precision up to 92%) exceeding those on the test and even training sets. This is highly unusual and suggests either a mismatch in data splits, potential leakage, or that the external set was inadvertently easier for the model.

While such unexpectedly elevated external performance might initially appear favorable, it fundamentally contradicts the expected generalization hierarchy wherein models should demonstrate monotonically decreasing performance as data becomes increasingly unfamiliar. External validation datasets, by definition, originate from different sources with distinct acquisition protocols, patient populations, and imaging characteristics, thereby representing the most challenging evaluation scenario. When a model’s external performance paradoxically exceeds its internal validation or test performance, this anomaly typically indicates that the external dataset inadvertently simplified the classification task; whether through fortuitous class distributions that align with the model’s learned biases, systematically clearer image quality that facilitates feature extraction, exclusion of diagnostically ambiguous cases that challenged internal validation, or statistical artifacts arising from small sample sizes. Such performance improvements cannot be interpreted as evidence of superior generalization capability; rather, they signal that the external validation failed to provide a genuinely independent or representative assessment of real-world clinical performance. Consequently, models exhibiting non-monotonic performance patterns must be regarded with heightened skepticism regardless of their numerical metrics, as these results likely reflect evaluation artifacts or dataset peculiarities rather than reliable diagnostic competence that would translate to diverse clinical deployment scenarios.

The regular CNN, meanwhile, showed a dramatic drop from 100% training accuracy to 79% (validation), 78% (test), and as low as 73% (external), further confirming its overfitting and lack of generalization.

Building on these observations, the DNN’s performance metrics generally decreased gradually from training to validation to test to external sets, as expected for a well-generalizing model. Specifically, accuracy dropped from 82% (train) to 81.5% (validation), 81% (test), and 76% (external). F1-score followed a similar trend: 82% (train), 81.5% (validation), 81% (test), and 80.5% (external). Recall also decreased monotonically across splits. However, precision notably increased on the external set, rising from 84% on train to 86% on external. This counterintuitive trend suggests that the model became more conservative in its positive predictions when faced with new data. Such an increase in precision, especially when recall drops, often indicates that the model is making fewer positive predictions overall, but those it does make are more likely to be correct. This behavior is commonly observed when there is a distributional shift between training and external data, prompting the model to raise its internal threshold for positive classification. As a result, the model reduces false positives (increasing precision) at the expense of missing more true positives (lower recall), reflecting a typical trade-off in response to increased uncertainty or changes in data distribution.

To synthesize these findings,

Table 3 summarizes how each model satisfied two key criteria: (1) exhibiting healthy learning curves, and (2) demonstrating a monotonic decrease in performance metrics across data splits. As shown, both LightGBM (via PyCaret) and the regular CNN failed to meet either criterion, reflecting their poor generalization and overfitting tendencies. The augmented CNN achieved healthy learning curves but did not maintain a monotonic decrease in performance metrics, primarily due to its unexpected improvement on both the test and external sets. Notably, only the DNN satisfied both criteria, highlighting its robust learning dynamics and consistent generalization behavior across all evaluation splits.

The DNN’s external validation accuracy of 76%, while representing a decline from internal performance metrics, warrants careful interpretation within the broader context of clinical ML development. First, the presence of external validation itself distinguishes this work from the majority of published OCT classification studies, which typically report only internal test set performance without independent dataset assessment. Second, the monotonic performance decrease from training (82%) through validation (81.5%), test (81%), to external validation (76%) represents a fundamental indicator of model reliability and methodological integrity. This gradual, consistent decline demonstrates that the model has learned generalizable patterns rather than memorizing dataset-specific artifacts. In contrast, models exhibiting inflated internal accuracies (approaching 95–100%) without external validation evidence, or those showing non-monotonic performance patterns, may achieve superficially impressive metrics while masking serious generalization failures that would only become apparent upon clinical deployment. The 76% external accuracy, though modest, provides an honest, conservative estimate of real-world performance expectations. Such transparency is essential for responsible clinical translation, as overestimating model capabilities based on inflated internal metrics poses direct risks to patient safety. This work prioritizes methodological rigor and honest performance reporting over the pursuit of artificially elevated accuracy figures. The established baseline of 76% external accuracy, achieved through demonstrably healthy training dynamics and rigorous multi-tier validation, provides a reliable foundation for future model refinements. Incremental improvements built upon this methodologically sound framework will yield clinically trustworthy systems, whereas models reporting higher accuracies without equivalent validation rigor cannot be safely translated to patient care regardless of their numerical performance claims.