Abstract

Green fintech merges sustainable finance with data-intensive innovation, but national translations of EU rules can create regulatory risk. This study examines how such risk manifests in Central Europe and which policy tools mitigate it. We develop a three-dimension framework—regulatory clarity and scope, supervisory consistency, and innovation facilitation—and apply a comparative qualitative design to Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia, and Poland. Using a common EU baseline, we compile coded national snapshots from primary legal texts, supervisory documents, and recent scholarship. Results show material cross-country variation in labelling practice, soft-law use, and testing infrastructure: Hungary combines central-bank green programmes with an innovation hub/sandbox; Slovakia aligns with ESMA and runs hub/sandbox, though the green-fintech pipeline is nascent; Czechia applies a principles-based safe harbour and lacks a national sandbox; and Poland relies on a virtual sandbox and binding interpretations with limited soft law. These choices shape approval timelines, retail penetration, and cross-border portability of green-labelled products. We conclude with a policy toolkit: labelling convergence or explicit safe harbours, a cross-border sandbox federation, ESRS/ESAP-ready proportionate disclosures, consolidation of recurring interpretations into soft law, investment in suptech for green-claims analytics, and inclusion metrics in sandbox selection.

1. Introduction

Green fintech sits at the intersection of two policy and market agendas: the digital transformation of finance and the transition to a low-carbon economy. While sustainable finance provides the objectives and instruments—green bonds, green credit and sustainability-linked finance—fintech supplies the enabling technologies—AI, blockchain, IoT and smart contracts—that can lower costs, expand access, and improve transparency (Liu and You 2023; Ogunruku et al. 2024). Yet this convergence also introduces new vectors of regulatory risk: rules written for traditional products must now govern data-intensive, cross-border services whose environmental claims depend on heterogeneous taxonomies, evolving disclosures, and digital operational resilience (Babar and Wu 2025; Broby and Yang 2025).

Conceptually, definitional ambiguity remains a first-order challenge. The literature distinguishes green finance from green fintech, but their boundaries blur in practice, raising greenwashing concerns where environmental benefits are asserted without verifiable evidence (Broby and Yang 2025). Consumer perception studies suggest that public awareness of fintech’s environmental impact is still limited, indicating a communication and evidence gap that policy must address (Piotrowska 2025). Technologically, blockchain can secure provenance and impact reporting for sustainable assets, AI can integrate diverse datasets for climate-risk analytics, and IoT can verify performance for sustainability-linked instruments, but these same tools create cybersecurity, privacy and energy-use trade-offs regulators must weigh (Ogunruku et al. 2024; Javaheri et al. 2023). From a supervisory standpoint, innovation often outpaces capacity, producing regulatory lag that manifests as uncertainty in approvals, labelling, and cross-border portability (Yan et al. 2022).

Against this backdrop, the European Union has advanced a single-market architecture for sustainable finance (Taxonomy, SFDR, CSRD) while also legislating digital finance (e.g., DORA, MiCA, the AI Act). The combined effect is powerful but complex: national implementations diverge, and market conduct rules, prudential expectations, and disclosure duties interact in ways that can amplify or mitigate regulatory risk for green fintech. This is particularly salient in Central Europe, where small and mid-sized markets share the EU baseline but differ in supervisory posture and innovation infrastructure. Comparative evidence on how these differences shape green fintech remains scarce, leaving a gap this paper addresses (OECD 2023; Zhou et al. 2024; Inderst and Opp 2025).

This study makes three contributions. First, it conceptualises regulatory risk in green fintech along three interrelated dimensions: regulatory clarity and scope, supervisory consistency, and innovation facilitation. Second, it constructs country snapshots for Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia and Poland, systematically mapping legal frameworks, supervisory tools, market activity, and planned reforms. Third, it offers a comparative assessment that explains cross-country differences in innovation-phase risk and derives a policy toolkit for risk-sensitive, innovation-friendly regulation, covering labelling convergence, sandbox federation, machine-readable disclosures, consolidated guidance, and supervisory suptech. Methodologically, the paper adopts a comparative qualitative design based on primary legal texts and supervisory documents, institutional reports, and recent peer-reviewed scholarship, ensuring triangulation across sources (Kálmán 2025; Gumbo 2025; OECD 2023).

The key findings, elaborated in the country sections and the comparative analysis, are threefold. First, innovation-phase risk is lowest where supervised testing channels exist (sandbox/hub) and where supervisors articulate expectations on labelling and product governance; absent these, firms face longer approval cycles and heavier reliance on case-by-case interpretations. Second, cross-border portability of green-labelled products hinges on how strictly or flexibly supervisors implement EU-level guidance (e.g., ESMA fund names) and whether recognition mechanisms are in place. Third, data readiness—ESRS/ESAP alignment and proportionate SME reporting—conditions the scalability of analytics-driven services (AI/IoT) that underpin many green fintech models. These insights inform the policy recommendations presented in the Conclusions, which aim to reduce legal uncertainty, strengthen consumer protection, and accelerate sustainable innovation without compromising prudential objectives (Broby and Yang 2025; Babar and Wu 2025; OECD 2023).

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on definitions, technologies, regulatory risk, instruments and international experience. Section 3 sets out the methodology and analytical framework. Section 4 presents the country snapshots and a comparative analysis of regulatory risk across the four jurisdictions. Section 5 concludes with policy recommendations and avenues for future research.

This paper addresses three questions: (RQ1) How do EU-level and national frameworks interact to shape regulatory risk in green fintech across small and mid-sized Central European markets? (RQ2) Which dimensions of regulatory risk—regulatory clarity and scope, supervisory consistency, or innovation facilitation—are most salient across the four cases? (RQ3) What policy levers best reduce innovation-phase risk while preserving market integrity and cross-border portability? The contribution is threefold: (i) a structured three-dimension framework for regulatory risk in green fintech, (ii) the first systematic, document-based comparison of Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia and Poland, and (iii) a policy toolkit tailored to experimentation pathways, product labelling and data readiness.

2. Literature Review

The rapid convergence of sustainable finance principles with financial technology (fintech) has given rise to the emerging domain of green fintech, a field that sits at the intersection of environmental objectives, technological innovation, and financial market development (Keserű 2023). The literature on this subject spans diverse themes, from conceptual definitions and technological enablers to the regulatory frameworks and market mechanisms that shape its evolution. Existing studies provide valuable insights into how green fintech can mobilise capital for environmentally beneficial projects, enhance transparency, and improve market efficiency. At the same time, they highlight significant regulatory, operational, and technological risks—particularly in cross-border contexts—stemming from inconsistent definitions, fragmented oversight, and varying market maturity levels. This review synthesises recent academic and policy contributions, organising them into thematic subsections that cover conceptual foundations, technological innovations, regulatory challenges, financial instruments, international experiences, and gaps for future research.

2.1. Conceptual and Definitional Foundations

Green finance is broadly defined as the allocation of financial resources toward activities and projects that promote environmental sustainability, such as renewable energy, green buildings, and pollution control initiatives (Muganyi et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2024). It includes a variety of instruments—green bonds, green loans, and ESG-oriented investment funds—designed to direct both public and private capital toward low-carbon economic activities (Sreenu 2024; Babar and Wu 2025).

In contrast, green fintech refers to the application of digital financial technologies in the service of green finance goals. It merges the efficiency, accessibility, and scalability of fintech with the environmental objectives of sustainable finance, thereby enhancing transparency and potentially reducing costs (Broby and Yang 2025). However, the definitional boundaries of green fintech remain blurred, leading to both interpretive uncertainty and risks of greenwashing, the misrepresentation of financial products as environmentally beneficial without verifiable evidence (Broby and Yang 2025).

To address these risks, Broby and Yang (2025) propose a six-step “litmus test” framework, requiring that a financial product or service not only leverage technological innovation but also demonstrate measurable environmental outcomes and clear regulatory alignment. Such definitional clarity is essential to ensure credibility in markets increasingly sensitive to ESG claims.

Piotrowska (2025) provides rare cross-national consumer survey data (UK, Germany, Poland, Ukraine), revealing generally low awareness of fintech’s environmental impact, indicating a perceptual gap in sustainable fintech evolution.

From a regulatory risk perspective, the absence of harmonised global standards for classifying “green” activities exacerbates legal uncertainty, particularly for fintech-enabled products that operate across borders (Babar and Wu 2025). While the EU has introduced instruments such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy to improve consistency, national-level interpretations and enforcement approaches still vary, creating potential compliance complexity for cross-border offerings (Babar and Wu 2025; Muganyi et al. 2021).

2.2. Technological Foundations and Innovation Potential

Green fintech leverages a range of emerging and established digital technologies to improve the efficiency, transparency, and impact of sustainable finance (Ogunruku et al. 2024; Liu and You 2023).

Blockchain technology provides immutable transaction records that can be used to verify the allocation and use of funds in green projects, enabling innovations such as tokenised green bonds and transparent carbon credit markets (Ogunruku et al. 2024; Babar and Wu 2025). By reducing opportunities for fraud and improving auditability, blockchain supports investor confidence in ESG-labelled assets.

Artificial intelligence (AI) enables advanced ESG data analytics, automates credit risk assessment for green lending, and facilitates real-time monitoring of environmental performance metrics (Liu and You 2023; Ogunruku et al. 2024). AI-driven models can integrate diverse datasets, including satellite imagery and IoT sensor feeds, to assess the environmental performance of financed projects. Fenwick et al. (2024) argue that the sustainable integration of artificial intelligence requires dynamic regulatory frameworks, often complemented by sandbox mechanisms.

Internet of Things (IoT) devices play a crucial role in collecting high-frequency environmental data, ensuring accurate reporting on energy usage, emissions, and supply chain sustainability (Ogunruku et al. 2024). This is particularly relevant for performance-linked financial products where loan terms or bond coupons depend on verified sustainability outcomes.

Smart contracts, deployed on blockchain platforms, can automate the disbursement of funds, trigger payments, or adjust terms based on predefined environmental performance indicators (Ogunruku et al. 2024; Babar and Wu 2025). These mechanisms reduce administrative costs and increase trust between counterparties.

While these technologies present significant opportunities, they also introduce new regulatory and operational risks. Data quality and standardisation challenges can undermine the credibility of ESG reporting (Broby and Yang 2025). Cybersecurity threats, privacy concerns, and the energy footprint of some blockchain protocols also raise questions about the net environmental benefit of certain green fintech applications (Ogunruku et al. 2024). Javaheri et al. (2023) provide a systematic review of cybersecurity threats in the fintech ecosystem, noting that green fintech solutions are equally exposed to financial and data security attacks, which carry both regulatory and reputational risks. While cybersecurity risks primarily concern the protection of financial data and transaction integrity, sustainability-oriented technological risks, such as the carbon footprint of AI, extend the risk management challenge to environmental dimensions, requiring an integrated approach to both digital security and ecological responsibility. Tkachenko (2024) highlights that the carbon footprint of AI and other high-computational technologies should be integrated into financial institutions’ risk management frameworks to avoid undermining sustainability objectives.

From a regulatory standpoint, the rapid pace of technological development can outstrip the capacity of supervisory authorities, especially in smaller jurisdictions with limited expertise in digital finance oversight (Babar and Wu 2025). This creates a regulatory lag, where innovative solutions may face uncertainty or delays in gaining market approval.

Regulatory sandboxes can themselves shape perceived regulatory risk: comparative evidence from the UK shows that sandbox entry reduces information asymmetries and regulatory uncertainty, improving financing outcomes for early-stage FinTechs (Cornelli et al. 2024). At the same time, critical political-economy accounts caution that sandboxes may enable ‘risk-washing’—symbolically taming risks while diffusing them across markets and social strata. (Brown and Piroska 2022).

2.3. Regulatory Environment and Dimensions of Regulatory Risk

Regulatory risk in green fintech arises when legal, supervisory, or policy frameworks fail to provide clear, consistent, and predictable rules for the development and deployment of environmentally oriented financial technologies (Babar and Wu 2025; Broby and Yang 2025). In the context of sustainable finance, such risks are amplified by the need to align technological innovation with evolving environmental taxonomies and disclosure requirements (Muganyi et al. 2021).

One major source of regulatory risk is the fragmentation of national rules. Even within the European Union, where the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and EU Taxonomy provide overarching guidelines, member states interpret and implement these frameworks differently (Busch 2023). This results in inconsistencies in how “green” is defined, monitored, and enforced, particularly affecting cross-border fintech-enabled products (Babar and Wu 2025).

A second challenge is the regulatory capacity gap. The speed of fintech innovation—spanning blockchain platforms, AI-based ESG scoring, and tokenised green securities—often exceeds the ability of supervisory bodies to assess risks and ensure compliance in real time (Babar and Wu 2025). This “regulatory lag” can delay product approvals, create compliance uncertainty, and dissuade investment in new green fintech solutions (Yan et al. 2022).

A third dimension is the uncertainty in green classification. Without harmonised, verifiable standards for assessing environmental benefits, there is a heightened risk of greenwashing, undermining both consumer trust and investor confidence (Broby and Yang 2025). This is particularly relevant for fintech platforms offering retail access to green bonds, carbon credit markets, or ESG-linked savings products, where consumer protection regulations intersect with sustainable finance policies.

Regulatory innovation tools such as regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs have emerged as mechanisms to mitigate these risks (OECD 2023). According to Kálmán (2025), well-designed sandbox systems—such as those in the United Kingdom, Singapore, and Hungary—not only accelerate the market entry of innovative solutions but also significantly reduce regulatory uncertainty. Similarly, Gumbo (2025) emphasises that sandboxes serve as a frontier for financial innovation, fostering active collaboration between regulators and fintech firms. Composite indicators that integrate green finance, fintech development, and inclusive finance can support more socially equitable and innovation-friendly regulatory frameworks (Novák et al. 2025). By allowing live-market testing under supervisory oversight, sandboxes enable fintech firms to refine their products while regulators gain early exposure to emerging business models (Muganyi et al. 2021). However, the effectiveness of such tools varies significantly by jurisdiction, with some Central European countries offering fully operational sandboxes and others relying on ad hoc consultation points.

2.4. Financial Instruments and Market Mechanisms

Green fintech operates within a financial ecosystem that is increasingly shaped by innovative sustainable finance instruments. Among these, green bonds and green credit are particularly significant due to their scalability and potential for integration with digital technologies. Large-sample evidence shows that some environmental funds increased inflows after sustainability pledges without reducing portfolio carbon footprints, underscoring the need for robust naming and disclosure rules (Abouarab et al. 2025). Relatedly, funds can display strategic voting on E&S proposals that mimics commitment while avoiding pivotal support, a pattern consistent with ‘greenwashing via governance’ (Michaely et al. 2024). ESMA’s fund-naming Guidelines respond to these risks by introducing quantitative thresholds and a safe-harbour for compliant managers (ESMA 2024a, 2024b, 2025).

Green bonds are fixed-income instruments earmarked for projects with measurable environmental benefits, such as renewable energy installations, energy efficiency upgrades, and sustainable transport infrastructure (ICMA 2021; Sreenu 2024). Their popularity has grown substantially in both developed and emerging markets, driven by investor demand for ESG-aligned assets and by government incentives (Babar and Wu 2025). The incorporation of fintech solutions—such as blockchain-based issuance and tokenization—can enhance transparency, streamline settlement, and lower transaction costs (Ogunruku et al. 2024; Broby and Yang 2025). At the issuer level, green bond announcements are associated with positive market reactions, particularly for first-time issuers and third-party-certified bonds (Flammer 2021). Tokenised green bonds, piloted in jurisdictions like Hong Kong and Singapore, have demonstrated the potential for fractional ownership and broader retail participation without compromising regulatory oversight (Broby and Yang 2025). Fintech adoption can reinforce corporate environmental governance by aligning green finance flows with ESG performance over the corporate life-cycle (Hu et al. 2025). Taken together, these findings illustrate that green fintech initiatives operate across diverse contexts—from corporate-level ESG integration in developed markets to large-scale renewable energy financing in emerging economies—highlighting the need for regulatory models that can adapt to different market structures and developmental stages.

Green credit refers to loans provided for projects that meet defined environmental criteria, with eligibility requirements typically more stringent than those for conventional loans (Liu and You 2023). In China, fintech applications such as AI-powered environmental risk scoring and big-data credit profiling have improved pre-loan investigation, reduced default rates, and facilitated the efficient allocation of funds to environmentally beneficial projects (Liu and You 2023; Muganyi et al. 2021). The ability to integrate IoT data streams into loan monitoring systems also allows for dynamic adjustment of loan terms based on real-time environmental performance (Ogunruku et al. 2024).

However, both instruments face challenges that intersect with regulatory risk. For green bonds, inconsistent reporting standards across jurisdictions can lead to uncertainty for investors and complicate cross-border issuance. For green credit, the lack of standardised environmental performance benchmarks can undermine comparability and transparency (Broby and Yang 2025). Moreover, in smaller markets, the limited capacity of regulators to verify environmental claims can result in reliance on third-party verifiers, which introduces additional oversight complexities (OECD 2023).

Fintech has the potential to mitigate these issues by providing digital verification tools, automated reporting systems, and blockchain-based audit trails. Yet, without harmonised regulatory frameworks, these innovations may remain underutilised or fragmented across markets (Babar and Wu 2025).

2.5. International Experiences and Lessons

International case studies provide valuable insights into how regulatory environments, market maturity, and technological adoption shape the evolution of green fintech.

China has emerged as a leader in integrating digital finance with green credit systems. State-led initiatives have encouraged banks to deploy AI-based credit scoring models and blockchain-enabled asset registries to track the environmental impact of loans (Liu and You 2023; Muganyi et al. 2021). Empirical evidence indicates that such integration not only improves credit allocation efficiency but also contributes to measurable reductions in industrial emissions (Muganyi et al. 2021). China’s experience underscores the role of coordinated policy frameworks in scaling green fintech innovations.

India has leveraged the synergy between fintech platforms and green bond markets to finance renewable energy and other sustainable infrastructure projects (Sreenu 2024). Digital platforms facilitate retail participation in bond markets, while blockchain-based issuance has improved transparency and reduced settlement times. The Indian case demonstrates that, even in emerging markets with capacity constraints, targeted regulatory support and technological innovation can expand investor access to green finance.

G7 and E7 countries reveal a more complex relationship between green fintech and sustainability outcomes. According to Zhou et al. (2024), fintech adoption in these economies correlates with improvements in environmental quality indicators. However, it also introduces systemic vulnerabilities, including cyber risks, market volatility, and the potential for regulatory arbitrage, especially in cross-border contexts. These risks are compounded when regulatory oversight is uneven across jurisdictions, as firms may choose to operate in markets with the least stringent environmental or technological standards (Babar and Wu 2025).

For Central Europe, these international experiences highlight two key lessons. First, technological adoption without harmonised regulations can exacerbate regulatory risk, leading to fragmented markets and inconsistent enforcement. Second, innovation-supportive tools such as regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs, when paired with robust environmental performance verification, can help bridge the gap between rapid fintech development and the slower pace of regulatory adaptation (OECD 2023). These lessons are particularly relevant in a region where EU-level rules coexist with diverse national interpretations, creating both opportunities and barriers for green fintech deployment.

2.6. Gaps in the Literature and Future Research Directions

Although the body of literature on green fintech has expanded in recent years, significant gaps remain in understanding how regulatory risk manifests and can be mitigated in different economic and institutional contexts.

First, there is limited comparative research on regulatory risks in green fintech within the European Union, particularly among small and mid-sized economies. Most existing studies focus either on global trends (Babar and Wu 2025; Zhou et al. 2024) or on large individual markets such as China (Liu and You 2023; Muganyi et al. 2021). This leaves a gap in the evidence base for regions like Central Europe, where market size, regulatory capacity, and EU-level obligations interact in unique ways.

Second, empirical studies on the interplay between technological risks and supervisory responses are scarce. While works such as Ogunruku et al. (2024) discuss the operational and environmental implications of emerging technologies, there is limited data on how regulators adapt supervisory practices to accommodate innovations like blockchain tokenisation, AI-driven credit scoring, and IoT-based environmental monitoring in the context of sustainable finance.

Third, there is a lack of standardised metrics for evaluating the effectiveness and interoperability of regulatory sandboxes in sustainable finance. OECD (2023) highlights the potential of sandboxes to reduce compliance uncertainty, but systematic evaluations comparing their impact on green fintech development across jurisdictions are rare.

Finally, cross-border regulatory coordination in green fintech remains underexplored. While Babar and Wu (2025) advocate for harmonised global standards, there is little empirical work assessing how divergent national implementations of EU rules—such as the SFDR and EU Taxonomy—affect the scaling of green fintech solutions across member states.

Addressing these gaps will require a combination of quantitative and qualitative research, including cross-country comparative analyses, regulatory case studies, and empirical evaluations of innovation facilitation mechanisms. This study aims to contribute to that agenda by examining regulatory risk in green fintech across four Central European jurisdictions, identifying both legal gaps and best practices for developing risk-sensitive, innovation-friendly regulatory models.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a document-based comparative approach to examine regulatory risk in green fintech across four Central European countries: Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia, and Poland. The four cases were selected because they share a common EU baseline yet display heterogeneous supervisory postures (e.g., safe-harbour vs. formal ESMA alignment), variation in innovation facilitators (presence/absence of sandbox/hub), and comparable market size. This combination allows meaningful cross-country comparison within a controlled institutional environment. Hungary and Poland, for example, have developed relatively active central agency (central bank or supervisory authority)-led initiatives and dedicated sandbox schemes, while Slovakia and Czechia are at earlier stages of formalising targeted green fintech policies. This combination of shared structural conditions and differentiated national trajectories offers a valuable basis for comparative analysis, enabling the identification of both common regional challenges and country-specific best practices.

The study does not involve empirical data collection, measurement, or statistical analysis. Instead, it relies on qualitative synthesis of publicly available sources, including regulatory texts, supervisory communications, policy strategies, official guidelines, and selected peer-reviewed literature. These materials were identified through targeted searches of official websites of national authorities (e.g., central banks, financial supervisory agencies, ministries), EU institutions (e.g., ESMA, EBA, European Commission), and reputable academic databases. The comparative approach is necessary to capture the legal, institutional, and policy nuances that cannot be fully conveyed by quantitative indicators. The overarching aim is to identify both similarities and divergences in national regulatory strategies, to analyse how these frameworks shape the manifestation of regulatory risk, and to distil lessons for innovation-friendly, risk-sensitive policy design.

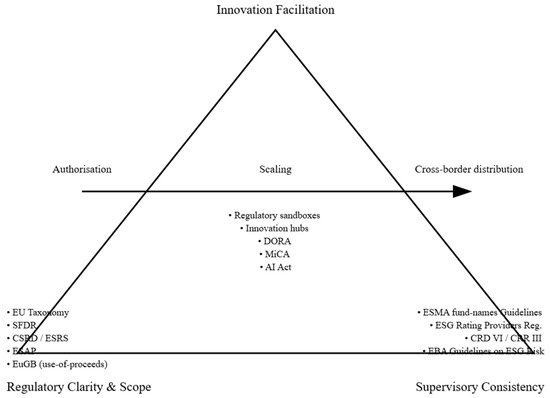

The analytical framework is structured around three interrelated dimensions of regulatory risk:

- Regulatory clarity and scope, referring to the degree to which laws and regulations explicitly address green fintech products, services, and operational models;

- Supervisory consistency, reflecting the level of coordination among national regulators and their alignment with EU-level directives;

- Innovation facilitation, which captures the presence and effectiveness of mechanisms such as regulatory sandboxes, targeted green finance incentives, and innovation hubs.

The analytical framework is allowing for direct comparability across jurisdictions. This enables a structured benchmarking process, where national approaches are evaluated relative to each other and in relation to overarching EU policy instruments such as the SFDR and the EU Taxonomy. The comparison highlights both common challenges—such as gaps in integrating green fintech explicitly into financial regulation—and examples of best practice that could be adapted across borders.

While this approach ensures methodological consistency and comparative validity, it is subject to certain limitations. The analysis is confined to formal regulatory and supervisory arrangements and does not cover informal governance or market-driven self-regulatory mechanisms. Furthermore, the study reflects the state of regulation and policy as of September 2025, the rapidly evolving nature of fintech technologies and sustainability frameworks means that subsequent developments may reshape the risk environment beyond the temporal scope of this research.

National legal texts, supervisory notices and policy documents were coded inductively into a structured codebook aligned with the three analytical dimensions (clarity and scope; supervisory consistency; innovation facilitation). Each data point (e.g., statutory change, soft-law issuance, sandbox use-case) was recorded with source, date and scope tags; two-step triangulation was applied across (i) primary legal/supervisory sources, (ii) institutional reports (EU/OECD/EBA), and (iii) peer-reviewed literature. Ambiguities were resolved by privileging primary sources. The cut-off date for all evidence is September 2025.

To enhance comparability across jurisdictions, each national snapshot follows an identical template (regulatory framework; innovation facilitation; market activity; planned developments; risk synthesis) and is benchmarked against the EU baseline. Where interpretation depended on supervisory practice (e.g., ESG product naming; sandbox eligibility), we report the most authoritative written position (notice, decree, guideline) and flag divergences versus peers. Limitations include the focus on formal frameworks (excluding informal market self-regulation) and potential evolution after the cut-off date.

4. National Snapshots and Regulatory Risk Assessments

4.1. EU Regulatory Baseline

This subsection summarises the common EU framework; country chapters focus only on deviations and implementation specifics.

The EU framework relevant to green fintech comprises three interacting layers. First, classification and disclosure: the EU Taxonomy defines environmentally sustainable activities, the SFDR governs entity and product-level sustainability disclosures, and the CSRD/ESRS mandates corporate-reporting standards with ESAP-ready data formats. These instruments determine the data environment on which fintech models rely, from ESG analytics to impact verification. Second, prudential and governance: CRD VI/CRR III and the EBA Guidelines on ESG risk management embed sustainability into strategy, risk appetite, internal controls and SREP, converging supervisory expectations across banks and investment firms on the 2026/2027 timeline. Third, market conduct and enabling digital finance: ESMA’s guideline on fund names addresses greenwashing risks in product labelling; the EU Regulation on ESG Rating Providers increases transparency in third-party assessments; the European Green Bond Regulation standardises sovereign/corporate green-bond use-of-proceeds; DORA (operational resilience), MiCA (crypto-assets/tokenisation) and the AI Act (high-risk AI) set guardrails for data-intensive, cross-border services typical of green fintech.

Implication for our design: national chapters report only (i) how these instruments are transposed or applied, (ii) any supervisory choices (e.g., ESMA fund-name uptake), and (iii) innovation-facilitation infrastructure (hub/sandbox) that shapes innovation-phase regulatory risk. For navigability, we provide per-country summary tables; see Table 1 (Hungary), Table 2 (Slovakia), Table 3 (Czechia) and Table 4 (Poland).

Table 1.

Hungary—Summary Table (Regulatory Risk Snapshot).

Table 2.

Slovakia—Summary Table (Regulatory Risk Snapshot).

Table 3.

Czechia—Summary Table (Regulatory Risk Snapshot).

Table 4.

Poland—Summary Table (Regulatory Risk Snapshot).

4.2. Hungary

The Hungarian National Bank (MNB) has positioned itself as an innovation-friendly, green-policy actor since launching its Green Program in 2019 to integrate climate and environmental risks into supervision, stimulate green finance, share knowledge and reduce its own footprint. The MNB is also a member of the NGFS, signalling alignment with central-bank peers on climate-related risk management (MNB 2019). A compact overview of statutory references, facilitators and risk levels is provided in Table 1.

Hungary operates both an Innovation Hub and a Regulatory Sandbox, giving market participants a structured channel for “ask-the-regulator” consultations and live-client testing under supervisory oversight. These facilities have been publicly available since 2018 and are listed by EU authorities among national innovation facilitators, providing predictable entry points for novel business models (MNB Innovation Hub; MNB Sandbox; EIOPA innovation-facilitator overview). In comparative perspective, this places Hungary alongside Slovakia (innovation hub and sandbox) and Poland (virtual sandbox and interpretative tools), and in contrast with Czechia, where a national sandbox is not yet in place.

Since 2021 the MNB has complemented prudential and supervisory actions with targeted green monetary policy tools, notably the Green Home Programme (GHP) and the Green Mortgage Bond Purchase Programme (GMBPP). The GHP provided low-interest central-bank refinancing to spur a domestic green housing-loan market and mainstream environmental criteria in housing finance; by its termination in September 2022 it had enabled ~8600 households to purchase or build energy-efficient homes (MNB Green Home Programme). In parallel, the GMBPP (launched 2 August 2021) created the market micro-infrastructure for green mortgage bonds through primary/secondary-market purchases under published conditions; the programme was subsequently suspended as part of the post-inflation monetary recalibration, but its market-building effects persisted (MNB notices and programme page). The MNB also issued impact-reporting recommendations for green mortgage bonds in 2025 and operates a Green Housing Preferential Capital Requirement Programme to tilt bank balance-sheets toward energy-efficient housing and renovations. Both reducing transition risk and improving households’ energy affordability (MNB 2023, 2025a).

This central-bank toolkit interacted with other public finance channels. For example, the EIB’s first green loan to Hungary (December 2021) supported energy-efficiency retrofits in homes and small-scale renewables, dovetailing with the national housing-efficiency agenda and creating complementary demand for green retail finance products (EIB 2021).

Following these policy signals, domestic banks issued green bonds under ICMA-aligned frameworks (e.g., mortgage banks) and developed green retail products such as green mortgages, energy-efficiency loans and carbon-footprint calculators for retail and SME clients. On the sovereign side, the Government Debt Management Agency (ÁKK) operates a Hungary Green Bond Framework (updated July 2023) with an external review, enabling repeated green issuances and reopenings for eligible uses (ÁKK 2023). Taken together, these instruments have broadened funding for energy-efficient housing, renovation and green infrastructure while anchoring disclosure and allocation practices in recognised standards (ICMA/Government framework; MNB Green Finance Reports).

On the supervisory side, the MNB’s Supervisory Green Programme explicitly treats climate and environmental risks as financial risks to be identified and managed across the system, with the Green Finance Report serving as an annual transparency tool for supervisors and industry (MNB 2023). In regional comparison, Hungary’s stance is more proactive than the neutral, risk-based posture of the Czech National Bank (which currently applies a “safe harbour” approach to ESMA fund-name guidelines) and is broadly comparable to Slovakia’s guidance-driven approach (which has explicitly adopted ESMA fund-name guidance for pension funds), while Poland’s supervisor has preferred interpretative tools and a virtual sandbox with relatively limited soft-law use to date.

Looking forward, the Hungarian regime will be shaped by the staged application of the EBA Guidelines on ESG risk management and the implementation of CRD VI/CRR III, mirroring timelines already visible in Czechia; market-building discussions have referenced potential 2025 green financing programmes for households and companies, conditional on macro conditions (EBA GLs/CRD-CRR as reflected regionally; NBH/Reuters forward guidance). Such macro-contingent design underscores a core regulatory-risk channel: policy effectiveness depends on inflation and rate-path uncertainty, which can alter parameter settings and the uptake of green retail products.

In regulatory clarity and scope, Hungary benefits from the EU framework and supplements it with programme-level guidance (e.g., green mortgage-bond impact-reporting recommendations), which reduces definitional uncertainty for issuers and investors relative to purely principle-based regimes (MNB 2025a, 2025b). In supervisory consistency, the integration of green monetary, prudential and supervisory tools (GHP/GMBPP and preferential capital regime and supervisory green programme) creates coherent signalling across policy silos, arguably stronger than in Czechia (neutral stance; selective ESMA adoption) and at least as structured as Slovakia (formal guidance) or Poland (virtual sandbox and interpretative rulings). In innovation facilitation, the Innovation Hub and Sandbox combination provides a lower-risk path for market entry and scaling of Green FinTech propositions than in jurisdictions lacking live-testing frameworks, this parallels Slovakia’s architecture but remains a differentiator vis-à-vis Czechia (no sandbox) (Innovation Hub/Sandbox; regional templates).

For a consolidated view of Hungary’s clarity, consistency and innovation assessments, see Table 1.

4.3. Slovakia

The National Bank of Slovakia (NBS) exercises integrated financial-market supervision and operationalises the relevant European instruments via national acts and guidance, creating a consolidated baseline for ESG-related obligations while leaving coordination gaps where disclosure, prudential and market-conduct layers interact. Directly applicable regulations—such as the EU Taxonomy, the European Green Bond Regulation and the Regulation on ESG Rating Providers—coexist with transposed measures, notably the CSRD, which has been implemented into Act No. 431/2002 Coll. on Accounting. In line with the institutional division of competences, the NBS supervises only those CSRD-reporting entities that are either listed or fall within the set of supervised financial institutions, other companies subject to CSRD requirements lie outside its supervisory perimeter (NBS 2024–2025, 2025). This EU-first legal architecture, coupled with concentrated supervisory powers at the NBS, provides a common baseline for ESG-related obligations, but also leaves coordination gaps where multiple acts interact and evolve in parallel (e.g., disclosure, prudential and market-conduct layers). A summary of Slovakia’s implementation profile, ESMA alignment and innovation tools is reported in Table 2.

The NBS has operated an Innovation Hub since April 2019 and established a Regulatory Sandbox in 2022. The two tools are differentiated by purpose and duration: the hub offers short, one-off consultations on concrete regulatory questions, whereas the sandbox enables iterative consultations and live-market testing under supervisory oversight, typically over a longer horizon and with closer engagement. In 2024 the hub recorded a 63% year-on-year rise in enquiries—an uptick the NBS links to preparations for the EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regime—while 2025 marked a milestone in the sandbox with the completion of the Crowdberry Investment Platform use case under the EU Crowdfunding Regulation. Notably, despite interest from a range of market participants, no explicitly Green FinTech project has yet advanced through the hub or the sandbox. From a regulatory-risk perspective, this combination of available but underutilised facilitators suggests that experimentation pathways exist in principle, yet pipeline formation in the ESG/green segment remains nascent.

On the supervisory-policy side, the NBS explicitly aligns with ESMA’s Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG or sustainability-related terms (ESMA 2024a, 2024b) and has adopted a Methodological Guideline tailored to the naming of pension and supplementary pension funds. The guideline sets the conditions under which ESG-related terms may be used so as to avoid misleading impressions of strategy or impact. This stance contrasts with the Czech National Bank’s neutral “safe-harbour” approach to the ESMA fund-name guidance and supports a clearer market signal for retail ESG products in Slovakia, particularly in pensions (cf. Czechia).

Market activity reflects a conservative but evolving ESG landscape. To date, three issuers have placed bonds under ICMA-aligned green frameworks—Slovenská sporiteľňa, Tatra banka and Gevorkyan—each supported by second-party opinions (Green0meter, ISS ESG, Sustainalytics, Morningstar). Banks also market products labelled as green loans. Beyond fixed income, several Slovak corporates have voluntarily obtained ESG ratings—most commonly from EcoVadis and, in some cases, Sustainalytics—despite the absence of a legal requirement, indicating a signalling strategy toward business partners and clients. In alternative finance, seven crowdfunding platforms are registered domestically, though none focus exclusively on green projects; one platform partially communicates opportunities in sustainable agriculture and the food industry. Funds operating in the capital market that use ESG-related terms are expected to comply with the ESMA naming guideline and the NBS methodological note, reinforcing minimum expectations on product labelling and investor communication.

The NBS’s overall regulatory attitude toward sustainability is supportive and information-oriented. In addition to publishing consolidated information on applicable sustainability legislation and FAQs for market participants, the NBS has issued consumer-facing materials covering ESG aspects of investments, loans, insurance and pensions. Institutionally, the central bank frames its own operations in line with environmental responsibility and EU recommendations, signalling a whole-of-institution approach even as the market itself remains relatively small. This combination of guidance, transparency and consumer education aims to reduce search and compliance costs for supervised entities while maintaining a risk-based prudential stance.

In terms of forward trajectory, the supervisory role of the NBS will evolve with the effective dates and national implementation steps of EU measures, including the EBA’s Guidelines on ESG risk management and the ESRS-based reporting regime under the CSRD. The country is also preparing for the introduction of the EU ETS 2 for buildings and road transport, expected to become fully operational from 2027, which will indirectly influence green-loan demand and transition-risk metrics used by financial institutions. At present, however, there are no announced NBS-initiated regulatory projects specifically targeting the financial-market sustainability agenda beyond these EU-driven changes, which means the near-term risk environment will be shaped primarily by European law and its domestic operationalisation.

Several structural challenges stand out in the Slovak context. Practitioners face difficulties navigating a rapidly changing, imperfectly interconnected body of EU and national rules, weakening legal certainty and potentially dampening voluntary ESG disclosures by firms not (yet) in scope. This, in turn, can create friction for supervised institutions that must rely on counterparties’ disclosures to fulfil their own obligations under instruments such as the SFDR. The limited penetration of explicitly green retail products and the absence of a dedicated green-crowdfunding channel further underscore supply-side constraints in the domestic market. These observations echo regional patterns but are more pronounced in smaller markets with fewer specialised intermediaries and rating providers on the ground.

A brief comparative reading helps situate Slovakia’s risk profile. Relative to Czechia, the presence of a functioning sandbox and explicit uptake of ESMA fund-name guidance reduces innovation-phase and labelling uncertainty; by contrast, Czechia’s neutral supervisory stance and the absence of a national sandbox tend to push experimentation into informal channels or cross-border pilots (cf. Czechia). Compared with Poland, where supervisory soft-law tools and a virtual sandbox exist but Green FinTech is largely shaped by broader fintech and ESG reforms, Slovakia’s clear alignment on ESG product naming offers a more predictable retail labelling environment, though both jurisdictions still face gaps in dedicated Green FinTech pipelines (cf. Poland).

Taken together, Slovakia’s regulatory-risk profile can be summarised along the three analytical dimensions used in this study. Regulatory clarity and scope are largely EU-driven, with helpful national guidance on ESG fund naming; nonetheless, the multiplicity and dynamism of applicable acts generate interpretation costs for firms outside the NBS’s prudential remit. Supervisory consistency benefits from the NBS’s integrated model and public guidance, but the absence of broader, sector-wide soft-law on green product governance leaves room for further convergence with prudential expectations. Innovation facilitation is formally strong—both the hub and sandbox operate—but the lack of Green FinTech cases to date indicates an execution gap: the tools exist, yet project origination and testing in the green vertical remain emergent, limiting the de-risking benefits that sandboxes can deliver for sustainability-focused fintech pilots.

The qualitative risk assessment (clarity/consistency/innovation) is synthesised in Table 2.

4.4. Czechia

Czechia’s regulatory setting for green finance and fintech is shaped primarily by EU law, complemented by a restructuring of domestic governance: in mid-2022 the government mandated the Ministry of Finance (MoF) to lead on sustainability finance, and a Sustainability Policy Department was launched on 1 January 2024. The MoF also established a Platform for Sustainability Financing (July 2023) to coordinate public–private dialogue through dedicated working groups, signalling an institutional move to centralise strategy, law-making and EU-methodology workstreams under the Green Deal agenda. These measures provide a forum for policy alignment, although they do not by themselves create a live testing environment for green fintech propositions. Key statutes, supervisory stance and market activity are summarised in Table 3.

At the level of financial-market oversight, the Czech National Bank (CNB) maintains a consolidated list of laws and has issued decrees to operationalise EU requirements in national law (e.g., Decree No. 184/2022 Coll. and No. 185/2022 Coll. for collective investment funds under SFDR and the EU Taxonomy; Decree No. 227/2022 Coll. to integrate sustainability factors in investment-services governance under Directive (EU) 2021/1269). The CNB’s Supervisory Notice No. 1/2025 reports investigations into asset-manager compliance with SFDR disclosure obligations across pre-contractual documents, periodic reports and websites, evidence that SFDR duties are being enforced for entities active on the Czech capital market. At the same time, the primary supervisory statute (Act No. 6/1993 Coll. on the CNB) does not explicitly recognise sustainability or climate change as potential sources of financial instability, and sustainability concepts are also absent from several core sectoral acts (Securities, Insurance Contracts, Capital Market Undertakings). The CNB has not yet fully established comprehensive criteria for Taxonomy compliance, leaving parts of the definitional architecture to EU-level interpretation and market practice.

A distinctive feature of the Czech stance is its approach to ESMA’s Guidelines on fund names using ESG/sustainability-related terms. The CNB has announced it will not apply the guidelines’ numerical thresholds in its supervisory practice due to the lack of a sufficient legal basis in Czech law. Instead, it applies a reasonableness test and offers a “safe harbour” for funds that voluntarily comply, those names will not be considered misleading. For cross-border distribution, the CNB advises that managers may still need to meet other authorities’ binding thresholds elsewhere in the EEA (ČNB 2024, 2025). This measured, principles-based posture contrasts with Slovakia, where the NBS has formally aligned with the ESMA guideline and issued a methodological note for pension funds, and it differs from Poland, where the supervisor relies more on interpretative tools rather than prescriptive soft law in the ESG-labelling space.

Corporate-reporting obligations are expanding. While roughly 25 companies have historically reported under the NFRD transposition, CSRD will extend mandatory sustainability reporting (Zhang et al. 2023) to approximately 1300 companies in Czechia, with the first wave covering public-interest entities (e.g., banks, insurers, issuers) reporting on 2024 for publication in 2025. Act No. 316/2025 Coll. has implemented CSRD primarily via amendments to the Accounting Act and the Auditors Act, and a CNB decree detailing ESAP data formats is expected in 2026. In prudential regulation, Act No. 280/2025 Coll. transposes CRD VI and reflects CRR III, with most provisions effective 11 January 2026, including explicit expectations for integrating ESG risks into strategy, governance, risk appetite and forward-looking plans, as well as updated governance and diversity requirements for management bodies. In parallel, the CNB has notified that it will apply the EBA Guidelines on ESG risk management (EBA/GL/2025/01) from 11 January 2026 (or 2027 for small/less complex institutions), subject to CRD VI transposition. Finally, the new EU Regulation 2024/3005 on ESG rating providers—published in December 2024—will become applicable 18 months after entry into force, adding transparency requirements to a market that many Czech firms currently access on a voluntary basis. Together these measures tighten the disclosure and prudential perimeter relevant to green-finance products and their enablers.

Market activity shows both momentum and constraints. On the financing side, 14 sustainable bond issues were recorded recently (12 green, one sustainability, one sustainability-linked), with the largest transaction a sustainability-linked issue by ČEZ to fund energy-efficiency and renewable capacity projects; typical issuers include real estate, energy and transport companies, and the investor base is dominated by institutional players (pension funds, insurers, banks). At the same time, green mortgages remain below 1% of the overall mortgage market—about EUR 50 million per year—indicating limited penetration of retail green credit to date. On the information side, the 2024 national ESG rating exercise covering 100+ domestic companies suggests ongoing standardisation in non-financial reporting, with banks over-represented among leaders due to their earlier NFRD obligations and the integration of ESG factors in credit processes. These patterns imply that while capital-market instruments and large issuers are active, retail-level products and smaller issuers may face higher fixed costs of compliance and thinner distribution channels.

The broader structure of the Czech financial market also shapes the opportunity set for green fintech. High household deposit shares (~67% of banking-sector funding) and a conservative asset-allocation culture can dampen demand for innovative offerings, while onboarding rules (in-person or Czech digital-identity verification) raise frictions for foreign entrants. Local attempts to build neobank models have struggled to scale domestically, with foreign digital banks (e.g., Revolut Bank) accumulating market share via remote acquisition. These frictions are not unique in the region but are more salient in Czechia’s market structure, potentially slowing the uptake of green fintech retail products that rely on rapid digital distribution and granular data.

Planned regulatory developments are incremental but material. In addition to the CSRD/ESAP and CRD VI/CRR III tracks, a new CNB decree on annual reports (with ESAP data specs) is foreseen for 2026, and the staged application of EBA’s ESG-risk guidelines is set. The MoF-led platform architecture and the Sustainability Policy Department can enhance public–private coordination around these changes, yet in the absence of a national regulatory sandbox, early-stage live-client testing of green-fintech propositions will likely continue to rely on informal dialogues or cross-border setups, raising time-to-market and compliance-uncertainty risks relative to jurisdictions offering supervised experimentation channels (cf. Slovakia/Poland).

From a regulatory-risk perspective, three dimensions stand out. Regulatory clarity and scope benefit from extensive EU alignment and targeted CNB decrees, but the lack of explicit statutory recognition of sustainability/climate as financial-stability factors—and the incomplete articulation of Taxonomy compliance criteria—leave parts of the legal map to be inferred from EU law and supervisory notices. Supervisory consistency is steady but cautious: SFDR enforcement is active; ESMA fund-name thresholds are not hard-wired, replaced by a reasonableness approach and a voluntary safe harbour; EBA guidelines will be adopted on the EU timeline. Innovation facilitation is the weakest link in comparative terms: unlike Slovakia (hub + sandbox) and Poland (virtual sandbox and interpretative rulings), Czechia offers coordination platforms but no supervised live-testing environment, implying higher innovation-phase regulatory risk (greater uncertainty on approvals, product-labelling, and cross-border portability). These features align with the country’s generally neutral, risk-based supervisory posture and help explain why market development has concentrated in larger issuers and institutional channels rather than retail green-fintech offerings.

For the dimension-by-dimension risk assessment, please refer to Table 3.

4.5. Poland

Poland’s debate on green fintech begins with definitional ambiguity: neither domestic legislation nor EU instruments provide a single, operational definition, and the term is used heterogeneously across strategies, reports and scholarship. For the purposes of this paper, we follow the Green Digital Finance Alliance (GDFA) approach—i.e., technology-enabled financial innovations that intentionally support the SDGs or reduce sustainability risks—recognising categories from green digital payments and investment to ESG data/analytics and green regtech. This definitional choice aligns with how Polish sources themselves frame the field and helps distinguish institutional fintech adoption (e.g., by banks) from innovative non-bank providers whose environmental intent is explicit (GDFA taxonomy cited in the national snapshot). The definitional gap matters because Poland’s financial system is bank-oriented with a high level of digital adoption—383 fintechs operated in 2025, the majority profitable and concentrated in payments and financial software—so clarity over what counts as “green fintech” conditions both market signalling and supervisory practice. Poland’s interpretative tools, virtual sandbox and ESMA alignment are consolidated in Table 4.

At the normative level, Poland’s green-finance and digital-finance rules are largely EU-driven and decoupled in their legal construction (sustainable finance vs. digitisation), which creates coordination costs exactly where green fintech sits at the intersection. The Polish Constitution recognises environmental protection as a state objective grounded in sustainable development (Art. 5), offering a broad mandate for policy and legislation, yet no dedicated national act addresses green fintech as such. Implementation proceeds through a patchwork of EU-law transpositions and domestic amendments: for example, an the Act of 25 June 2025 amending certain acts in connection with ensuring the operational digital resilience of the financial sector and the issuance of European green bonds, while the Accounting Act was amended to implement CSRD, the Bonds Act to accommodate green bond practices, and the Public Offering Act in an ESG context; the framework statute for supervision (Act of 21 July 2006 on Financial Market Supervision, UNRF) structures the institutional setting. In practice, the legal burden arises from the cumulative application of EU instruments (Taxonomy, SFDR, CSRD, MiCA, DORA, the AI Act), whose concurrent roll-outs alter both firm processes and supervisory methods and thus constitute a primary channel of regulatory risk for green fintech propositions that rely on data, digital operations and sustainability disclosures simultaneously.

Within this framework, the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) has been assigned tasks to support financial-market innovation (UNRF Art. 4.1.3a) and can issue individual legal interpretations upon request where the question concerns products or services aimed at developing innovation (UNRF Art. 11b). Poland also operates the Innovation Hub and a Virtual Sandbox, which—together with Art. 11b opinions—offer ex ante navigational aids for novel models. Nonetheless, the snapshot emphasises that, to date, the KNF’s stance has been relatively passive and soft-law instruments (recommendations/guidelines) have not been used to set out green-finance expectations, leaving firms to rely on EU-level texts and case-by-case interpretations (KNF 2025a, 2025b). ESG risk is generally treated cross-cuttingly (i.e., as a driver of established risk types) and is picked up in the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), with plans to enhance ESG examinations; an internal Simplification Team (27 February 2025) has also proposed burden-reduction options focused on ESG reporting complexity (e.g., elements of CSRD/ESRS or CSDDD scope). A Working Group for Financial Innovation Development (FinTech) within the UKNF has developed barrier-removal proposals (including the very idea of binding interpretations later implemented via Art. 11b). The sector has complemented this with self-regulation, notably the Polish Bank Association’s “Good Practices for Using the Taxonomy to Qualify Real Estate as Environmentally Sustainable” (ZBP and PZFD 2024), to improve consistency in mortgage-related green classifications. From a regulatory-risk perspective, these tools mitigate entry uncertainty but do not substitute for substantive guidance on green product governance and labelling.

Market activity spans both capital-market and retail banking channels. On the bond side, Polish banks have issued green bonds under ICMA-conform frameworks (e.g., PKO Bank Polski S.A., Bank Ochrony Środowiska S.A.), while on the retail side green mortgages and eco-loans gained traction: e.g., PKO Bank Polski S.A. offers margin reductions tied to energy performance certificates (“Własny Kąt” programme); Santander Bank Polska S.A. provides eco-credit for energy-infrastructure modernisation; co-operative banks (SGB) distribute anti-smog loans aligned with the national “Clean Air” programme. Banks have also deployed carbon-footprint calculators for retail and business clients (e.g., Santander Bank Polska S.A., BNP Paribas Bank Polska S.A., Credit Agricole Bank Polska S.A., ING Bank Śląski S.A.), with ING Bank Śląski S.A. additionally offering institutional emission and energy-efficiency calculators for buildings. On the innovation side, Alior Bank’s iLab has been internationally recognised, while PKO Bank Polski’s “Green Impact 7” channels capital and mentoring to climate-focused startups (e.g., Green Money, GreenReporting). In the insurance space, KUKE provides guarantees that de-risk financing for climate-mitigation innovators. Gaps remain: there is no investment-crowdfunding platform dedicated exclusively to green projects (some generalist platforms host an “ecology” category), and digital-only banks (neobanks) operating in Poland show limited green-product depth; a notable exception is N26′s Green Account, marketed with a claim to offset 100% of users’ footprints. These patterns suggest strong institutional activity and retail pilots, but a thinner pipeline of born-green fintechs at scale.

Compared with Czechia and Slovakia, Poland’s labelling and soft-law environment is distinctive. The CNB in Czechia applies a principles-based “reasonableness/safe harbour” approach and has not adopted ESMA’s numerical fund-name thresholds, whereas the NBS in Slovakia has formally aligned with ESMA’s guideline and issued a methodological note for pensions; Poland’s supervisor, by contrast, has not issued soft-law on ESG product naming, relying instead on general EU obligations and the interpretative route. For cross-border distribution and for retail communications, this implies greater predictability in Slovakia, managerial discretion (with safe harbours) in Czechia, and interpretative dependence in Poland—three different pathways that translate into different profiles of regulatory labelling risk for green-fintech products in the region.

The near-term trajectory is shaped by EU implementation cycles. Polish market participants—and the KNF—are simultaneously absorbing the operational requirements of MiCA, DORA, and the AI Act, as well as CSRD/ESRS and forthcoming EBA ESG-risk guidelines, all of which touch the data, disclosure and ICT-risk pillars that green fintech models rely on. The KNF’s indication that ESG examinations will be strengthened under SREP is directionally consistent with peers, but without broader soft-law on, e.g., green product governance or expectations for sustainability analytics, compliance uncertainty will continue to be resolved via the Innovation Hub, Virtual Sandbox, and Art. 11b opinions rather than general guidance (with associated resource demands for both firms and the supervisor).

These features produce a regulatory-risk profile that can be read along the three dimensions used in this study. Regulatory clarity and scope are anchored in EU law and recent national amendments (including the 2025 act on digital-resilience and European green bonds), but the absence of a codified green-fintech category and of sector-wide soft-law on green product governance preserves interpretation risk for data-heavy, sustainability-labelled fintech offerings. Supervisory consistency benefits from the KNF’s integrated legal basis (UNRF), the SREP channel for ESG, and the availability of binding interpretations (Art. 11b), yet the limited proactivity in setting expectations means practice evolves case-by-case. Innovation facilitation is formally present—it depends on project origination in the green vertical and on the KNF’s willingness to translate iterative insights into general guidance. In comparative terms, Poland sits between Slovakia and Czechia: more tools than Czechia (no sandbox) and closer to Slovakia’s experimentation architecture, but less explicit than Slovakia on ESG labelling and less proactive than Hungary on combining prudential, monetary and supervisory green programmes (cf. country snapshots).

The resulting qualitative risk profile is shown in Table 4.

4.6. Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Risk in Central Europe

Across the four Central European jurisdictions, the legal baseline for green finance and fintech is set by EU law (notably the Taxonomy, SFDR and CSRD), yet national implementations and supervisory practices vary in ways that translate into distinct regulatory-risk profiles (Table 5). Slovakia and Czechia have explicitly embedded EU instruments into domestic frameworks (e.g., CSRD transposition and sectoral decrees), while Poland relies on a patchwork of EU-driven amendments without a dedicated “green fintech” act, and Hungary pairs the EU baseline with an innovation-facilitation stance identified in our methodological discussion. The side-by-side evidence across Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 indicates that facilitator-rich settings (sandbox/hub) correlate with lower innovation-phase risk, whereas principles-based regimes without supervised testing exhibit higher uncertainty in approval pathways and cross-border portability. These differences shape the legal clarity available to market participants seeking to launch or scale sustainability-labelled, data-intensive fintech solutions across borders.

Table 5.

Snapshot Box.

In Czechia, the Ministry of Finance has centralised sustainability–finance policy, and the CNB has issued decrees aligning fund rules with SFDR/Taxonomy; crucially, CSRD coverage expands to ~1300 companies, with implementing legislation already adopted, which tightens disclosure expectations that green-fintech models depend on for ESG data-flows (Accounting/Auditors Acts, ESAP-related steps planned). Slovakia has transposed CSRD into the Accounting Act and applies the EU sustainable-finance acquis within an integrated supervisory architecture at the NBS, though not all CSRD-reporting companies fall under its prudential perimeter. Poland embeds sustainability and digitisation via multiple, separately constructed regimes (e.g., a 2025 act addressing operational resilience and European green bonds; CSRD into the Accounting Act; ESG-related tweaks to the Bonds and Public Offering Acts), but no dedicated national act addresses “green fintech” as such—leaving firms to navigate cumulative EU requirements at the intersection of disclosure, ICT-risk and prudential rules. Hungary shares the EU baseline and is positioned in our design as a jurisdiction with relatively active central-bank-led initiatives, offering a clearer pathway for innovators than purely principle-based regimes without live testing provisions.

The CNB adopts a principles-based approach to the ESMA guideline on ESG-themed fund names: it does not hard-wire numerical thresholds due to the absence of a sufficient legal basis, but provides a “safe harbour” for voluntary compliance and continues SFDR supervision through targeted investigations—an approach that preserves discretion but introduces cross-border labelling frictions when other EEA supervisors apply binding thresholds. By contrast, the NBS in Slovakia formally aligns with the ESMA guideline and has issued a Methodological Guideline for pension fund naming, providing a clearer retail-labelling signal under integrated supervision. In Poland, the KNF can issue binding individual interpretations (UNRF Art. 11b) and operates innovation-facilitation tools, yet it has not deployed broader soft-law on green product governance or naming; ESG risk is treated cross-cuttingly and is being strengthened within SREP, which supports prudential consistency but leaves market conduct questions to case-by-case resolution. In our framework, Hungary is situated as more proactive on innovation-support under central-bank leadership than Czechia’s neutral stance, and at least as structured as Slovakia’s guidance-based model—differences that affect approval timelines and the predictability of supervisory expectations for green-fintech pilots.

Slovakia combines an Innovation Hub (2019) with a Regulatory Sandbox (2022); enquiry volumes rose with MiCA preparations, and the sandbox has completed a crowdfunding case, though no explicitly “green fintech” project has yet run through either channel—suggesting an execution gap between available tools and ESG-oriented pipeline formation. Poland offers an Innovation Hub and a Virtual Sandbox, complemented by Art. 11b interpretative opinions; taken together, these reduce entry uncertainty but stop short of sector-wide guidance for green product governance. Czechia, in turn, does not operate a national sandbox; policy coordination has improved (MoF platform, Sustainability Policy Department), yet supervised live-testing remains absent—raising innovation-phase regulatory risk relative to peers with testing channels. Within our design, Hungary is grouped with jurisdictions operating a functioning sandbox and central-bank innovation facilitation, implying lower experimentation risk than in “consultation-only” systems.

Recent Czech issuance data report 14 sustainable bond issues (12 green; one sustainability; one sustainability-linked, with ČEZ prominent), while green mortgages remain below 1% of the mortgage market (~EUR 50 million annually)—a sign of higher fixed costs and limited retail uptake despite institutional momentum. Slovakia records three green-bond issuers (two banks and one corporate) under ICMA-aligned frameworks with second-party opinions; several entities voluntarily obtain ESG ratings (EcoVadis; Sustainalytics) in the absence of legal compulsion. Poland shows a bank-led product suite—ICMA-aligned bank green bonds; green mortgages with EPC-linked pricing; eco-loans; carbon-footprint calculators for retail/SME; bank-run innovation labs and climate-startup programmes—yet lacks a dedicated green-crowdfunding platform and exhibits limited green-product depth among digital-only banks (with N26 Green Account an outlier). Against this backdrop, the presence of supervised testing and proactive supervisory signalling (ascribed to Hungary in our framework) correlates with smoother pathways for early product roll-out than in markets relying on principle-based or interpretative approaches alone.

Czechia’s CSRD/ESAP implementation expands disclosure obligations and feeds supervisory use-cases (e.g., greenwashing assessments), while CRD VI/CRR III and the EBA ESG-risk Guidelines become effective from 11 January 2026 (or 2027 for small/less complex institutions)—together hardening prudential expectations around ESG risk management. Slovakia anticipates EU ETS 2 roll-out for buildings and road transport by 2027 and continues aligning with EU sustainability legislation, but reports no NBS-initiated national projects beyond these tracks. Poland is concurrently absorbing MiCA, DORA, the AI Act, and CSRD/ESRS, with KNF signalling stronger ESG examinations via SREP, while maintaining a reliance on Virtual Sandbox and Art. 11b for case-specific clarity. Taken together, these timelines indicate converging prudential baselines across the region, with divergence persisting in market-conduct labelling (ESMA guideline uptake) and innovation-testing infrastructure.

Viewed through our three-dimension lens, Slovakia represents a “sandbox-and-guidance” model (lower labelling uncertainty; tools in place but green pipeline still nascent), Czechia a “platform-plus-principles-based” model (robust EU alignment and institutional coordination; higher innovation-phase risk without a sandbox; safe-harbour labelling), Poland an “interpretation-led” model (formal facilitators and binding opinions; fewer soft-law expectations; bank-centric green products), while Hungary fits a “sandbox-plus-central-bank” model that tends to lower experimentation risk and strengthen signalling relative to neighbours without supervised testing environments. For cross-border green fintech propositions, these differences imply non-trivial compliance–portability costs: a product label or testing pathway acceptable in Slovakia (ESMA-aligned naming; sandbox) may require renegotiated treatment in Czechia (reasonableness/safe harbour) or individual interpretations in Poland, whereas Hungary’s facilitation posture can compress time-to-market but still relies on EU-driven disclosure and ICT-risk regimes shared with its peers.

5. Conclusions

Building on the three-dimension framework (Figure 1) and the country evidence (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4), we draw three sets of conclusions regarding regulatory risk in green fintech across Central Europe. This paper has shown that regulatory risk in green fintech across Central Europe is driven less by the absence of EU-level rules than by national variation in (i) how clearly those rules are translated to market practice, (ii) how consistently supervisors signal expectations, and (iii) whether credible, supervised experimentation channels exist to bring sustainable, data-intensive financial innovations to market. Hungary and Slovakia illustrate “facilitator-rich” settings (sandbox/hub) with more predictable pathways for pilots, while Czechia’s principles-based stance without a sandbox and Poland’s interpretation-led model create greater reliance on case-by-case navigation. These differences raise compliance–portability costs for cross-border green fintech and slow time-to-market relative to jurisdictions offering supervised testing and clear product-labelling expectations.

Figure 1.

Three dimensions of regulatory risk across the green-fintech product lifecycle and key EU instruments.

Policy recommendations follow directly from these findings:

Converge on ESG product labelling. Authorities should either adopt ESMA’s fund-name guideline (including thresholds) or codify a safe-harbour “comply-or-explain” approach with explicit criteria and supervisory FAQs. This reduces greenwashing risk and improves retail comparability (Broby and Yang 2025; OECD 2023). Where discretion is retained (as in Czechia), publish cross-border recognition notes so managers understand portability limits ex ante (Gumbo 2025).

Build a regional “sandbox federation”. A V4 Green FinTech Testing Network—a memorandum among supervisors to mutually recognise eligibility, share test results, and allow remote participation/virtual sandboxes—would compress approval frictions and enable simultaneous multi-market learning (Kálmán 2025; OECD 2023). Start with common use-cases (green mortgages, tokenised green bonds, climate-risk analytics) and a unified ex ante test plan template.

Make disclosures machine-readable and proportionate. Align national guidance with ESRS/ESAP-ready formats and offer an SME-proportionate green data pack (baseline indicators + EPC hooks), lowering data-collection costs for fintechs that rely on counterparties’ sustainability information (Babar and Wu 2025; Liu and You 2023). Pilot IoT-assisted performance reporting (e.g., energy-efficiency loans) with audit trails to deter greenwashing (Ogunruku et al. 2024).

Translate recurring interpretations into general guidance. Where supervisors rely on binding individual opinions (e.g., Poland), periodically consolidate them into soft-law circulars on green product governance, model risk in ESG analytics, and customer communications. This preserves flexibility while cutting duplication for firms (Yan et al. 2022).

Strengthen supervisory capacity with suptech/regtech. Invest in green-claims analytics, taxonomy-mapping tools, and SREP workflows for ESG risk—synchronised with the EBA’s 2025/2026 timelines—so expectations are transparent and enforceable. Pair this with targeted training on data assurance for tokenised instruments and climate-risk models (Zhou et al. 2024).

Adopt “no-regrets” product standards in retail markets. Standardise EPC-linked pricing and disclosures for green mortgages; publish impact-reporting templates for green (covered) bonds drawing on ICMA practice; and define minimal verification steps for retail “green” claims (ICMA 2021; Sreenu 2024).

Bake inclusion into green fintech. Use inclusive green finance metrics when prioritising sandbox cohorts and funding windows, ensuring that low-income households and SMEs can access energy-efficiency finance—consistent with evidence that fintech can reduce information asymmetries while raising equity concerns if design is narrow (Novák et al. 2025; Muganyi et al. 2021).