Abstract

People with intellectual disability have unmet health needs and experience health inequalities. There is limited literature regarding cancer care for children, adolescents, and young adults (AYA) with intellectual disability despite rising cancer incidence rates in this population. This systematic review aimed to identify the psycho-social and information support needs of AYA cancer care consumers with intellectual disability to generate recommendations for future research and cancer care service delivery enhancement. We searched eight databases yielding 798 articles. Following abstract and full-text review, we identified 12 articles meeting our inclusion criteria. Our three themes related to communication and accessible information; supports and system navigation, cancer service provider training, and reasonable adjustments. There was a lack of user-friendly, accessible information about cancer and screening programs available. Both paid and family carers are critical in accessing cancer supports, services, and screening programs for AYA with intellectual disability. Ongoing training should be provided to healthcare professionals regarding the importance of care screening for AYAs with intellectual disability. This review recommends that AYA with intellectual disability and their family carers be involved in developing tailored cancer services. This should focus on enabling inclusive screening programs, accessible consent, and challenging the enduring paternalism of support services via training and appropriate communication tools.

1. Introduction

Adolescents and young adults (AYA) who have been diagnosed with cancer have been recognised as a distinct population since the early 1990s [1] and it is estimated that globally there are over 1,000,000 new diagnoses each year [2]. While no global estimates exist, many more AYAs will have a sibling or parent diagnosed with cancer. Identified impacts for AYAs diagnosed with cancer include complex medical, psychosocial, emotional, and fertility concerns, with detrimental effects on quality of life, education, as well as physical and social development [3,4,5,6]. These impacts can extend for years post treatment during the survivorship phase [2,3,5,7,8]. While AYA siblings of cancer patients do not experience the physical aspects of cancer diagnosis and treatment, they can experience similar disruptions to their family routines alongside worries about their sibling, which can lead to increased distress and emotional and behavioural problems [7,8]. For many AYAs whose parents are diagnosed with cancer, the experience can be disruptive and detrimental with reports of very high levels of psychological distress and associated unmet needs [9]. As a group, AYAs impacted by cancer experience have considerable information and support needs [9,10]. Information needs include wanting to understand what is happening with treatment in age-appropriate language and feeling listened to, while support needs include knowing how to manage changes in relationships with friends and family, disruption to normal home and education routines, and feelings of isolation [8,9,10,11,12]. These considerable disruptions can lead to increased mental health concerns often evidenced by higher levels of psychological distress and reduced well-being.

While the support needs of marginalised sub-groups of cancer patients have been identified as needing particular attention if equitable treatment, support, and care is to be provided to all cancer patients [13,14], the limited research to date involving disadvantaged AYAs impacted by cancer has focused on gender, poverty [15], residential locality, race, and insurance status [15,16]. To date, it appears there has been little to no attention paid to the experience of young people with intellectual disability who also have either a personal or familial cancer experience, and in particular no attention has been given to their information or psychosocial support needs.

It is estimated that globally approximately 1% of the population have an intellectual disability and that this is higher amongst children and adolescents [17]. Intellectual disability is characterised by impairments in intellectual functioning (typically an IQ of below 70) and adaptive functioning, including skills required for independent daily living, with onset during the developmental period [18]. While intellectual disability is the preferred term in Australia, Ireland, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, the term ‘learning disability’ is commonly used in the United Kingdom [19]. As per Cluley [19], intellectual disability is the preferred term internationally and is used in this paper.

A recent review of admissions to Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network in 2017 for children aged 0–18 years found that 13.9% of admissions greater than 23 h involved a child or AYA with intellectual disability [20]. In addition, 8% of cancer-related admissions in the sample were for children with intellectual disability [21,22,23,24]. It is well-established that people with intellectual disability face barriers when accessing health care, including limited organisation knowledge about intellectual disability, inhibitive staff perceptions, and problems with communication [25]. A recent systematic review exploring the psychosocial experiences of people with intellectual disability and chronic illness found there are difficulties in communicating with care teams and understanding the illness, leading to feelings of uncertainty, confusion, and distress [23]. AYA who have intellectual disability and experience cancer in their lives, either through their own or a family member’s diagnosis, are likely to have specific support and information needs. It is vital that these needs are recognised to ensure appropriate supports are available.

2. Purpose and Question

2.1. Study Purpose

The aims of this review were to systematically identify and appraise the existing evidence of the psycho-social and information support needs of AYA with intellectual disability who access cancer services, as a patient, sibling and/or other family member of someone diagnosed with cancer. Specifically, our objectives were:

1. Identify the current evidence regarding information and psychosocial support needs of adolescents and young people aged 15–25 with intellectual disability.

2. Thematic analysis and narrative synthesis of the information and psychosocial support needs of AYA cancer care consumers with intellectual disability.

3. Generate recommendations for future research and cancer care service delivery enhancement.

2.2. Study Question

What are the psycho-social and information support needs of AYA cancer care consumers with intellectual disability, as a patient, sibling, and/or other family member?

3. Methods

The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO, which is an international registry for systematic reviews (CRD42021224101) [26]. We conducted a systematic search and narrative synthesis according to Green et al. [27].

3.1. Search Strategy

To ensure a search strategy that was both sensitive and specific, a comprehensive search methodology to identify both published and grey (e.g., policy reports, national/international guideline documents, etc.) literature was developed and executed through routine scientific database searches and grey literature retrieval. Key search terms were agreed by the team in consultation with a librarian (Supplementary File S1). The search period was from the 1st of January to 30th of March 2021. We systematically searched the following academic databases: Medline; Embase; Emcare; PsycINFO; CINAHL; Web of Science; Scopus; and the Cochrane library. Two grey literature repositories were also searched: Open Grey, Open Doar and eight identified websites (refer to Supplementary File S2). Seven additional journals were also identified for hand searching (refer to Supplementary File S3).

3.2. Search and Selection Process

Identified studies were screened for eligibility using Covidence (www.covidence.org, accessed on 1 February 2021). All studies had their title and abstracts screened, and potentially relevant studies had their full text reviewed to determine eligibility. Meeting fortnightly, disagreements were resolved by discussion between at least three authors (É.N.S., F.M.D., L.M.).

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies had to meet the following criteria to be included:

3.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Types of Studies

- Published from 1 January 2000 [28] until 31 January 2021.

- English language.

- Studies involving AYAs aged 15–25 years with intellectual disability diagnosed in individuals less than 18 years who demonstrate permanent impairments to learning, thinking and reasoning, and social functioning [18].

- Current or past cancer care consumer, including as a patient, as a sibling, or other family member of someone accessing cancer care services in any cancer care setting and in any country.

- Parent/carers, siblings or health professionals acted as proxies for AYA with intellectual disability.

3.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies that do not report specific data related to AYAs aged 15–25 years of age.

- Studies involving AYA without intellectual disability only.

- Studies of AYA with chronic and/or complex conditions but do not have intellectual disability. For example, dyslexia, hearing loss/speech delay, reading difficulty, physical disability, Autism/Autistic Spectrum Disorder without intellectual disability [29], and mental health disorder.

- Prevalence studies.

3.3.3. Outcomes

Data regarding information and/or psychosocial needs; defined as the emotional and well-being needs beyond physiological needs, of AYA cancer services and supports for consumers with intellectual disability.

3.4. Data Extraction

A narrative synthesis of extracted data was conducted because of the substantial methodological heterogeneity between studies to identify patterns within the literature [30,31]. The findings of included publications were reviewed using the narrative synthesis approach, based on the study objectives, to elicit key themes outlined in the papers [31]. Three team members (É.N.S., F.M.D., L.M.) extracted the following information for each study: authors, publication year, country, study design, cancer type, intellectual disability, sample size and psychological interventions. Thematic analysis was undertaken on the papers and initial coding was developed following inductive analysis [32]. Via weekly meetings, data extraction and analysis were completed by É.N.S., F.M.D., and L.M. and reviewed and agreed upon by all authors.

3.5. Quality Appraisal

The quality of the included studies was assessed to determine the robustness of the results and how much weight should be given to each study when interpreting patterns in the literature overall. One author (ÉNS) used the 13-item Quality Assessment Tool for Diverse Studies (QuADS) as the appraisal tool. QuADS was selected as a validated instrument that is best suited to appraising a heterogenous group of studies or mixed and/or multi-methods studies within systematic reviews [33]. Study quality was not an inclusion/exclusion criterion for inclusion in the review but is presented in the published summary table.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

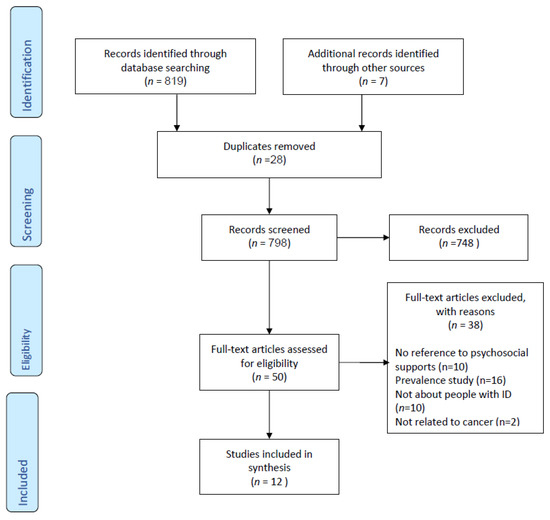

A total of 826 studies were identified from the literature, including seven journal articles obtained from handsearching. After duplicates were removed (n = 28), 798 studies were screened for inclusion. A total of 748 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening and 38 were excluded after full text evaluation. A total of 12 studies were included in this review. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flowchart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart.

4.2. Study Characteristics

The 12 included studies were published between 2007–2020 [22,34] and their characteristics are presented in Table 1. Nine studies were from the United Kingdom [21,22,23,24,34,35,36,37,38] two studies from Canada [39,40] and one from Australia [41]. Three studies combined a literature review with expert opinion and reflections and/or contributions from relevant stakeholders [38,40,41]. Two studies were systematic reviews, one published in 2020 [34] and the second in 2007 [22]. A study from Canada reviewed health administrative databases and registries to review cancer screening utilisation by women with intellectual disability (n = 17,777) focused on cervical and breast cancers compared with a 20% sample from a database of women with an intellectual disability (n = 1,440,962) [39]. Two surveys were undertaken. One study captured oncology nurses’ views of caring for people with intellectual disability [23]. The second was a survey of care staff on how they engaged in cancer prevention and health promotion activities with people with intellectual disability [21]. There was one evaluation from 2007 of a cancer information pack for people with an intellectual disability to support enhanced communication and understanding [36]. Three studies were qualitative. One undertook interviews with six people with an intellectual disability and twelve from their support network to capture their experiences of cancer [24]. The second qualitative paper involved four people with intellectual disabilities affected by cancer to inform the development of a research agenda [35]. The third paper used an ethnographic approach involving 13 interviews with family and paid carers supported by focused observations on women with intellectual disabilities attending breast awareness and breast screening programs [37]. Out of the 12 studies extracted, nine papers either did not provide age breakdown of participants or those involved were over the age of 25. This was an initial exclusion criterion but following discussions it was agreed to retain the nine studies due to their relevance. Three papers included and identified adolescents or young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 with an intellectual disability, along with older participants [22,35,39]. Two of the identified papers mentioned children impacted by familial cancer [31,37]. This was in the context of proposed future research [37] and a study with participants who were bereaved due to familial cancer [31]. Due to the low number of papers, the scope was broadened to include screening papers, and it is important to note that these studies did not focus on people diagnosed with cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of reviewed studies.

Following thematic analysis, three themes were agreed upon linked to the psycho-social and information support needs of AYA with intellectual disability:

- Communication and Accessible Information

- Supports and System Navigation

- Cancer Service Provider Training and Reasonable Adjustments

4.3. Communication and Accessible Information

The lack of accessible communication for AYAs with intellectual disability about cancer, either their own or about a family members diagnosis, was a major finding in all of papers extracted. There was a lack of user friendly, accessible information about cancer and screening in particular [21,34]. A recent systematic review published in 2020 focused on capturing the attitudes and opinions of people with learning disabilities, family carers, and paid care workers towards national cancer screening programmes [34]. A total of eleven papers met their study criteria and were all related to cervical and breast screening. The review found the need to shift communication and information sharing to women accessing screening programs to become more person-centred. In particular, letters sent to women inviting them to attend screening programs were not accessible, and the review recommended the need for modifications to the invitations process to include visual and alternative communications aids or electronic recordings [34]. This point was also made in a 2015 study capturing the views and experiences of paid- and family-carers when supporting women with intellectual disabilities through breast screening [37]. The study found that how carers approached and explained the screening following the arrival of an invitation letter had a direct impact on the woman’s final decision about participating in the procedure [37]. A paper evaluating a communication tool developed for people with intellectual disabilities found that it enabled users to communicate and exercise choice by developing their own understanding [36].

4.4. Supports and System Navigation

The role of both paid and family carers was addressed as key gatekeepers and enablers in accessing cancer supports, services and screening programs for AYA with intellectual disability [23,24,34,35]. A study from Canada that reviewed the literature and included the expert insights of the authors stressed the need of women with intellectual disability and their caregivers for more support and guidance during reproductive health care to enable their involvement [40,41,42]. A second study from Canada compared the attendance rates of cervical and breast cancer screening of women from the general population with women with intellectual and developmental disabilities [39]. The study found the proportion of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities who are not screened for cervical cancer was nearly twice that in the women without a disability and 1.5 times that for mammography [39].

The role of family caregivers and paid staff was noted as crucial in providing information on cervical and breast cancer screening, in supporting the person during the procedure and reporting any potential symptoms of cancer to health professionals. Developing interventions on information and training to support caregivers and staff in this role was recommended [39]. One paper from the UK argued that the role of family carers as gatekeepers was a taboo topic [35]. For people with intellectual disability, an underlying cause of negative experiences was that they were frequently bypassed when information was being provided [35]. This resulted in the family carer having control over the level of information to share with the person [35]. There was also evidence of paternalistic attitudes outlined in the paper with gatekeepers reporting that they felt discussing experiences of cancer would be too upsetting [35]. The bypassing of people with intellectual disability within cancer consultations and being excluded from conversations about their care and treatment related decisions was noted in another UK study [24]. Caregivers (family and paid) were being relied upon by healthcare staff to facilitate communication and understanding and supplement health care professional knowledge. The paper outlined the need to enable increased empowerment and involvement of people with intellectual disability [24].

A recent systematic review from 2020 outlined that some family carers tried their best to balance their decision about supporting cancer screening and the likelihood of distress against the benefit to the person with intellectual disability [34]. If the family carer and/or paid care workers had an unfavourable opinion towards cancer screening programs this was likely to impact on the person with intellectual disability resulting in them feeling anxious and reluctant to partake [34]. The review recommends the need for proactive, person-centred cancer screening invitations, which do not focus on health literacy and family or paid care workers, but rather empower the person with intellectual disability to make an informed decision on whether to attend a screening program [34].

A review from 2017 focused on the literature on psychosocial support needs in the complex care of children with both life-limiting conditions and intellectual disability [41]. As so few papers were identified in their review, the authors, who worked as clinicians in a tertiary children’s hospital in Brisbane, Australia, presented their expert group recommendations. They report that research is needed in the areas of symptom management and care coordination, communication and decision making, psychosocial and bereavement support, and education/training for a child with a life-limiting condition and intellectual disability. Children’s understanding of death and dying of their close families, particularly for children with intellectual disability, was another suggested focus of further research [41]. One paper from 2010 reported specifically on the process of developing an advisory forum’ of people with intellectual disability affected by cancer [35]. The paper involved conversations with four people with an intellectual disability, one who had experienced cancer and three who were the child and/or close relative of a person who had died from cancer. The paper stressed the need to challenge the enduring paternalism of services and opening of a dialogue about how best to support people with intellectual disability to engage in their cancer care [35].

4.5. Cancer Service Provider Training and Reasonable Adjustments

Ensuring ongoing training of healthcare staff was a central finding in the literature focused on a number of key areas [21,34,38,40]. One such area noted from research in cancer screening is that training should be provided to healthcare professionals on the importance of health screening for people with intellectual disability and on how to support their patients in understanding and consenting to a cancer screening procedure [23]. A 2015 paper from the UK explored the perceptions of oncology nurses regarding the provision of cancer care for patients with intellectual disability [23]. Interviews with the nurses found a perception that looking after a cancer patient with intellectual disability would be more time consuming and complex. However, the research also found that previous experiences and increased training of caring for people with intellectual disability worked as an influencing factor against negative perceptions [23]. The authors recommend that training and information must be provided to professionals on the importance of health screening for people with intellectual disability, and this should support their understanding of and consent to cancer screening programs [21]. Training for social care staff in order to raise knowledge and awareness was highlighted in a survey with 40 carers [21]. A systematic review stressed that training needs should be focused on professional practice barriers including the need for enabling multidisciplinary working to support people with intellectual disability [34].

Screening programs in particular should implement reasonable adjustments to reduce anxiety and improve the experience [23,38] of people with intellectual disability. Any adjustments developed should involve the input of AYA with intellectual disability and their families [23,38]. An Australian paper incorporated the expert opinion of clinicians working in a children’s acute hospital on the challenges of providing paediatric palliative care to children with intellectual disability [41]. Throughout the paper, the clinicians stressed the importance of family-centred approaches, noting the need for time to enable shared decision making focused on growing trust and relationships between children, families, and healthcare professionals [41]. A scoping study focused on evidence and gaps in breast cancer support for women with intellectual disability included a consultation with relevant stakeholders in the UK city of Sheffield [38]. The work highlighted a dearth of research and practice guidelines to support women with intellectual disability who are diagnosed with cancer. Two other studies that noted this gap were literature reviews. One undertaken in 2007 focused on the evidence around the need of people with intellectual disabilities for palliative care [22]. The review found an almost total absence of insights from people with intellectual disability themselves to develop guidelines.

5. Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review to identify and synthesise the evidence on psychosocial support and information needs for adolescents and young adult cancer consumers who have intellectual disability. Twelve papers met the inclusion criteria, of which two papers included family members of cancer patients who have intellectual disability. Our review found a large cohort of the academic literature focused on prevalence studies which were excluded. One of the difficulties with identifying papers that included AYAs was that very few papers provided detailed demographic information that is typically found, such as the age of the participants. There was also limited information reported on the severity of intellectual disability and the appropriateness of resources or services for those with severe or profound intellectual disability.

Women’s health and cancer screening programs specifically, was the focus of the twelve papers, and we note the gap around men’s cancer screening programs. While important for positive cancer outcomes, screening programs are targeted at the general population, and therefore the inclusion of these papers meant including papers that were not focused on people impacted by a cancer diagnosis. Most of the papers were qualitative, with small sample sizes included. The papers highlight that for people with intellectual disability including AYAs with intellectual disability, how information is received impacts on their screening experience. There is an urgent need to develop accessible information about screening programs using appropriate methods, such as easily read information and videos. Making available information and training on the importance of screening is also a clear learning from this systematic review targeting both family and paid carers. There is also a significant gap in the literature on the role of primary and community care towards disease identification, providing the space for understanding and accessible education for AYA with an intellectual disability [42,43].

A significant finding from this systematic review was the lack of evidence on what were major support needs of cancer care consumers with intellectual disability [22,24,38,41]. Adolescence and young adulthood represent an age when people start to become responsible for their own health decisions, and for females in particular this is when cancer screening is initiated. For AYA with intellectual disability, the transition from child to adult care services can be particularly challenging and overwhelming [44]. A negative experience at this age has the potential to have a negative influence on screening throughout life, with the reverse also being true. We found no literature that specifically examined the emotional, social, or psychological experiences of AYA with intellectual disability impacted directly by a cancer diagnosis, nor on the experiences of AYA with intellectual disability who have a family member, such as a sibling or a parent, diagnosed with cancer. For AYA without an intellectual disability who are impacted by parental cancer, effective communication within the family and with parents especially is their greatest unmet need and a predictor for positive outcomes [45]. It is anticipated that AYA with intellectual disability who rely on family members for caring and support may experience considerable distress and disruption if someone in their family is diagnosed with cancer, and the family care givers may be unable to continue to provide the same level of support.

People with intellectual disability face inequities when accessing health and social care services [46]. It remains encouraging to note that the recent academic literature has started to question the lack of focus on the experience of cancer care and survivorship of people with intellectual disability [47,48,49,50]. However, more focused attention is needed. A recent scoping review focused on the context of cancer care in the United States recommends the urgent need for improving caregiver support, collaboration among health care providers, and ethical approaches to information disclosure for people with intellectual disability as well as the establishment of pathways of care [50]. Healthcare staff concerns around having the time and resources to deliver care required for people with intellectual disability were prominent in the included studies. The literature regarding healthcare experiences for children and adults with intellectual disability reported poor experiences. In a 2014 systematic review of poor hospital experiences for adults with intellectual disability, healthcare staff identified limited knowledge and a lack of information and training in caring for people with intellectual disability [51]. For hospitalised children and young people with intellectual disability, healthcare staff assumptions and lack of knowledge about the child with intellectual disability results in an overreliance on parents and carers to meet their child’s care needs [52,53]. Additionally, AYAs with intellectual disability who have a family member diagnosed with cancer are likely to be excluded from conversations with HCPs completely.

It is clear in the literature that adolescent and young adult oncology is now a well-established sub-specialty, distinguishable from paediatric and adult oncology in terms of incidence [52,53]. Their specific psychosocial characteristics and health service needs has been outlined in the academic literature [54,55,56]. Advances have occurred in embedding standards of care, screening for psychosocial risk and supporting the involvement of AYA in their care decisions [55,56,57]. Additionally, in some health systems, specialised services have been developed for AYA with cancer [3,58,59,60]. However, this systematic review notes that AYA with intellectual disability experience exclusions in accessing patient centred and inclusive health services whether they are the patient or a family member of the patient. This further marginalises this group and contributes to the health inequities experienced by children and AYA with intellectual disability [18]. Our review noted very little information was available on their perspectives. While there is a need for hospital-based staff to receive training and support in improving care for AYAs with intellectual disability, there is also a role for the community sector. In some instances, provision of appropriate communication tools and support in using them could be provided by community organisations who have the appropriate expertise. There is also the possibility for national community organisations to provide additional support to these vulnerable young people and their families, and to facilitate peer support.

5.1. Study Limitations

There were limitations to this review. Only three papers provided a specific age breakdown of participants that fit the adolescent and young adult criteria of 15–25 years and none focused on AYAs only. Articles were restricted to only those in the English language. However, the search terms for this review were purposely broad. There was a lack of continuity across studies in type of data, measures, and study design within the extraction. There was also inconsistent reporting on the ages or cancer diagnosis of participants with intellectual disability, in the papers, something that future papers should provide as a minimum. No evidence was available on the experiences of an AYA with severe and profound intellectual disability. However, a few papers reported on the severity of intellectual disability. Additional data and breakdowns on age would allow for additional analysis across studies. It is possible that relevant articles may have been missed. This risk was minimized by seeking the input of a research librarian to design the search string. We are confident that together with hand searching we have identified all relevant studies. Despite limitations, this systematic review provides valuable insights into the psychosocial needs of AYA with an intellectual disability impacted by cancer.

5.2. Implications for Practice

There is an urgent need to shift focus away from incidence studies of levels of cancer in people with intellectual disability. There is a clear case to support the need for professional training in supporting AYA with intellectual disability and developing appropriate information resources. Further research needs to enable the involvement of AYA with intellectual disability in shaping research priorities and describing the impact of cancer on them [26,60]. Consideration is also needed to better understand how to support AYAs with severe and profound intellectual disability, how to support AYA with intellectual disability who are siblings or children of cancer patients, including during end-of-life care, death and bereavement, how to support families and caregivers to provide support to these AYAs, and the role of primary and community care. Service providers and researchers need to collect information about intellectual disability and consider how the voices of those with intellectual disability can be heard. Following this, support services can be further tailored to meet their unique needs.

6. Conclusions

The needs of AYA with intellectual disability who are also impacted by cancer are not well understood. Research to date has focused on prevalence, with limited research also examining screening, information, and caregiver needs. To provide the necessary support to this group of young people, research is urgently needed that involves them, to understand their support and psychosocial needs.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children8121118/s1, Supplementary File S1: Key Search Terms; Supplementary File S2: Search Strategy Summary; Supplementary File S3: Databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization methodology and validation—All Authors. Writing—original draft preparation, É.N.S., F.Mc.D. and L.M.; Writing—review and editing—All Authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Martha Gerges for her contributions at the screening state of this systematic review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AYA | Adolescents and young adults |

| QuADS | Quality Assessment Tool for Diverse Studies |

References

- Zeltzer, L. Cancer in adolescents and young adults psychosocial aspects. Long-term survivors. Cancer 1993, 71, 3463–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyer, A.; Ferrari, A.; Whelan, J.; Barr, R.D. Global assessment of cancer incidence and survival in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, L.; Walker, R.; Henney, R.; Cashion, C.E.; Bradford, N.K. Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Barriers in Access to Psychosocial Support. J. Adolesc. Young-Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeveld, N.E.; Ubbink, M.C.; Last, B.F.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Voûte, P.A.; De Haan, R.J. Educational achievement, employment and living situation in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer in the Netherlands. Psycho-Oncology 2002, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, N.K.; Henney, R.; Walker, R.; Walpole, E.; Kennedy, G.; Nicholls, W.; Pinkerton, R. Queensland Youth Cancer Service: A Partner-ship Model to Facilitate Access to Quality Care for Young People Diagnosed with Cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.L.; Hudson, M.M. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, F.E.J.; Patterson, P.; White, K.J.; Butow, P.; Bell, M.L. Predictors of unmet needs and psychological distress in adolescent and young adult siblings of people diagnosed with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.A.; Lehmann, V.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Carpenter, A.L.; Marsland, A.L.; Alderfer, M.A. Psychosocial functioning and risk factors among siblings of children with cancer: An updated systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; McDonald, F.; White, K.; Walczak, A.; Butow, P. Levels of unmet needs and distress amongst adolescents and young adults (AYAs) impacted by familial cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patterson, P.; D’Agostino, N.M.; McDonald, F.E.; Church, T.D.; Costa, D.S.; Rae, C.S.; Siegel, S.E.; Hu, J.; Bibby, H.; Stark, D.P.; et al. Screening for distress and needs: Findings from a multinational validation of the Adolescent and Young Adult Psycho-Oncology Screening Tool with newly diagnosed patients. Psycho-Oncology 2021, 30, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, T. The psychosocial impact of parental cancer on children and adolescents: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2007, 16, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelman, C.L. The Adolescent and Young Adult with Cancer: State of the Art-Psychosocial Aspects. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 15, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer Kelly, E.; McGee, J.; Obeng-Gyasi, S.; Herbert, C.; Azap, R.; Abbas, A.; Pawlik, T.M. Marginalized Patient Identities and the Patient-Physician Relationship in the Cancer Care Context: A Systematic Scoping Review. Support Care Cancer. 1 July 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06382-8 (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Ashley, L.; Lawrie, I. Tackling inequalities in cancer care and outcomes: Psychosocial mechanisms and targets for change. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, C.C.; Lupo, P.J.; Roth, M.E.; Winick, N.J.; Pruitt, S.L. Disparities in Cancer Survival Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Population-Based Study of 88 000 Patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darlington, W.S.; Green, A.L. The role of geographic distance from a cancer center in survival and stage of AYA cancer diagno-ses. Cancer 2021, 127, 3508–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulik, P.K.; Mascarenhas, M.N.; Mathers, C.D.; Dua, T.; Saxena, S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: A meta-analysis of popula-tion-based studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.M.; Hatton, C.; Baines, S.; Emerson, E. Systematic Reviews of the Health or Health care of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review to Identify Gaps in the Evidence Base. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 28, 455–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- From “Learning Disability to Intellectual Disability”—Perceptions of the Increasing Use of the Term “Intellectual Disability” in Learning Disability Policy, Research and Practice-Cluley-2018-British Journal of Learning Disabilities-Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bld.12209 (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Mimmo, L.; Harrison, R.; Travaglia, J.; Hu, N.; Woolfenden, S. Inequities in quality and safety outcomes for hospitalized children with intellectual disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, L.M.; Taggart, L.; Cousins, W. Cancer prevention and health promotion for people with intellectual disabilities: An ex-ploratory study of staff knowledge. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffrey-Wijne, I.; Hogg, J.; Curfs, L. End-of-Life and Palliative Care for People with Intellectual Disabilities Who have Cancer or Other Life-Limiting Illness: A Review of the Literature and Available Resources. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2007, 20, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S.; Hulbert-Williams, N.; Hulbert-Williams, L.; Bramwell, R. Psychosocial experiences of chronic illness in individuals with an intellectual disability: A systematic review of the literature. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 19, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flynn, S.; Hulbert-Williams, N.J.; Hulbert-Williams, L.; Bramwell, R. “You don’t know what’s wrong with you”: An exploration of cancer-related experiences in people with an intellectual disability. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Hassiotis, A.; Strydom, A.; King, M. Self-stigma in people with intellectual disabilities and courtesy stigma in family carers: A systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 2122–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimmo, L.; Harrison, R.; Mears, S. Systematic Review of the Psychosocial Support Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults Cancer Care Consumers with Intellectual Disability. PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021224101. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=224101 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2001. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Matson, J.L.; Shoemaker, M. Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snilstveit, B.; Oliver, S.; Vojtkova, M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Rogers, A.; Williams, G. Rationale and Standards for the Systematic Review of Qualitative Literature in Health Ser-vices Research. Qual. Health Res. 1998, 8, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Shé, É.; O’Donnell, D.; Donnelly, S.; Davies, C.; Fattori, F.; Kroll, T. “What Bothers Me Most Is the Disparity between the Choic-es that People Have or Don’t Have”: A Qualitative Study on the Health Systems Responsiveness to Implementing the As-sisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.; Jones, B.; Gardener, P.; Lawton, R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): An appraisal tool for methodo-logical and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrnes, K.; Hamilton, S.; McGeechan, G.J.; O’Malley, C.; Mankelow, J.; Giles, E.L. Attitudes and perceptions of people with a learn-ing disability, family carers, and paid care workers towards cancer screening programmes in the United Kingdom: A quali-tative systematic review and meta-aggregation. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbat, L.; McCann, L. Adults with intellectual disabilities affected by cancer: Critical challenges for the involvement agenda. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2010, 19, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, T.; Wilkinson, T.; Crudgington, S. Supporting people with intellectual disability in the cancer journey: The ‘Living with cancer’ communication pack. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2007, 11, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, D.; Kilbride, L.; Horsburgh, D.; Kennedy, C. Paid- and family-carers’ views on supporting women with intellectual disability through breast screening. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 24, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; McClimens, A.; MeKeonnen, S.; Wyld, L. Breast Cancer Information and Support Needs for Women with Intellectual Disabilities: A Scoping Study—Psycho-Oncology. Psycho-Oncology 2014. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/pon.3500 (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Cobigo, V.; Ouellette-Kuntz, H.; Balogh, R.; Leung, F.; Lin, E.; Lunsky, Y. Are cervical and breast cancer screening programmes equitable? The case of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2013, 57, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abells, D.; Kirkham, Y.A.; Ornstein, M.P. Review of gynecologic and reproductive care for women with developmental disabil-ities. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 28, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, J.K.; Herbert, A.R.; Heussler, H.S. Paediatric palliative care and intellectual disability—A unique context. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S.; Hulbert-Williams, L.; Bramwell, R.; Stevens-Gill, D.; Hulbert-Williams, N. Caring for cancer patients with an intellec-tual disability: Attitudes and care perceptions of UK oncology nurses. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.; Patterson, P.; Thomas, D. Trials and tribulations: Improving outcomes for adolescents and young adults with rare and low survival cancers. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209. Available online: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/209/8/trials-and-tribulations-improving-outcomes-adolescents-and-young-adults-rare-and (accessed on 20 September 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weise, J.C.; Srasuebkul, P.; Trollor, J.N. Potentially preventable hospitalisations of people with intellectual disability in New South Wales. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 215, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, M.-A.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M.; Lynch, L.; Mannan, H.; Byrne, E. A narrative synthesis scoping review of life course domains within health service utilisation frameworks. HRB Open Res. 2019, 2. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7140772/ (accessed on 6 May 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailie, J.; Laycock, A.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.S. Increasing health assessments for people living with an intellectual disability: Lessons from experience of Indigenous-specific health assessments. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 215. Available online: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/215/1/increasing-health-assessments-people-living-intellectual-disability-lessons (accessed on 5 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.; O’Mahony, M.; Hegarty, J.; Farrell, D.; Taggart, L.; Kelly, L.; Sahm, L.; Corrigan, M.; Caples, M.; Martin, A.M.; et al. Defining breast cancer awareness and identifying bar-riers to breast cancer awareness for women with an intellectual disability: A review of the literature. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 1744629521999548. [Google Scholar]

- Samtani, G.; Bassford, T.L.; Williamson, H.J.; Armin, J.S. Are Researchers Addressing Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Among People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in the U.S.? A Scoping Review. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 59, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacono, T.; Bigby, C.; Unsworth, C.; Douglas, J.; Fitzpatrick, P. A systematic review of hospital experiences of people with intel-lectual disability. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mimmo, L.; Woolfenden, S.; Travaglia, J.; Harrison, R. Partnerships for safe care: A meta-narrative of the experience for the par-ent of a child with Intellectual Disability in hospital. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimmo, L.; Harrison, R.; Hinchcliff, R. Patient safety vulnerabilities for children with intellectual disability in hospital: A sys-tematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Paediatr. Open. 2018, 2, e000201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; McDonald, F.E.; Zebrack, B.; Medlow, S. Emerging Issues Among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 31, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom-Daly, U.M.; Wakefield, C.E.; Patterson, P.; Cohn, R.J.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Wiener, L.; Fardell, J.E. End-of-Life Communication Needs for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Recommendations for Research and Practice. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrack, B.; Bleyer, A.; Albritton, K.; Medearis, S.; Tang, J. Assessing the health care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer 2006, 107, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Millar, B.; Desille, N.; McDonald, F. The Unmet Needs of Emerging Adults with a Cancer Diagnosis: A Qualitative Study. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, E32–E40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Kazak, A.E.; Noll, R.B.; Patenaude, A.F.; Kupst, M.J. Standards for the Psychosocial Care of Children with Cancer and Their Families: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, S419–S424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deatrick, J.A.; Kazak, A.E.; Madden, R.E.; McDonnell, G.A.; Okonak, K.; Scialla, M.A.; Barakat, L.P. Using qualitative and participatory meth-ods to refine implementation strategies: Universal family psychosocial screening in pediatric cancer. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2021, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardell, J.E.; Patterson, P.; Wakefield, C.E.; Signorelli, C.; Cohn, R.; Anazodo, A.; Zebrack, B.; Sansom-Daly, U. A Narrative Review of Models of Care for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Barriers and Recommendations. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Models of Care for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Programs-Osborn-2019-Pediatric Blood & Cancer-Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pbc.27991 (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Shé, É.N.; Gordan, A.; Hughes, B.; Hope, T.; McNally, T.; Whelan, R.; Staunton, M.; Grayson, M.; Hazell, L.; Wilson, I.; et al. “Could you give us an idea on what we are all doing here?” The Patient Voice in Cancer Research (PVCR) starting the journey of involvement in Ireland. Res. Involv. Engag. 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).