Abstract

Aim: This systematic review compared erbium lasers (Er:YAG/Er,Cr:YSGG) with conventional rotary instruments (dental turbine/high-speed handpiece) for caries removal and cavity preparation in pediatric dentistry, focusing on patient-centered outcomes and short-term restorative performance. Methods: Following PRISMA guidance, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for studies published between January 2010 and November 2025. Eligible studies were in vivo/human investigations in children with carious primary teeth comparing erbium laser versus rotary instrumentation. Results: Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. Across the included trials, erbium laser treatment was consistently associated with reduced intraoperative pain and improved comfort, often accompanied by lower anxiety indicators and higher child acceptance compared with rotary preparation. Several studies also reported a reduced need for local anesthesia in the laser group. In contrast, operative time was generally longer with erbium lasers than with turbines. When restorations were evaluated, clinical performance and short-term success (up to 12 months) were comparable between laser- and bur-prepared cavities, with no consistent disadvantages observed for laser preparation. Conclusions: Overall, erbium lasers appear to be a clinically effective and child-friendly alternative to conventional turbines, offering superior patient comfort while maintaining comparable short-term restorative outcomes, albeit at the cost of longer procedure duration.

1. Introduction

In contemporary clinical practice, the management of dental caries in juvenile patients represents a significant challenge [1,2,3]. Successful treatment requires not only effective removal of carious tissue but also careful consideration of the emotional and behavioral responses of young children during dental procedures [4,5,6]. For decades, conventional high-speed rotary instruments, commonly referred to as dental turbines, have been regarded as the gold standard for cavity preparation because of their efficiency and rapid cutting ability [5,7]. Nevertheless, their use is frequently associated with discomfort, vibration, noise, and potential thermal irritation, factors that may increase anxiety and reduce cooperation in pediatric patients during treatment [4,8].

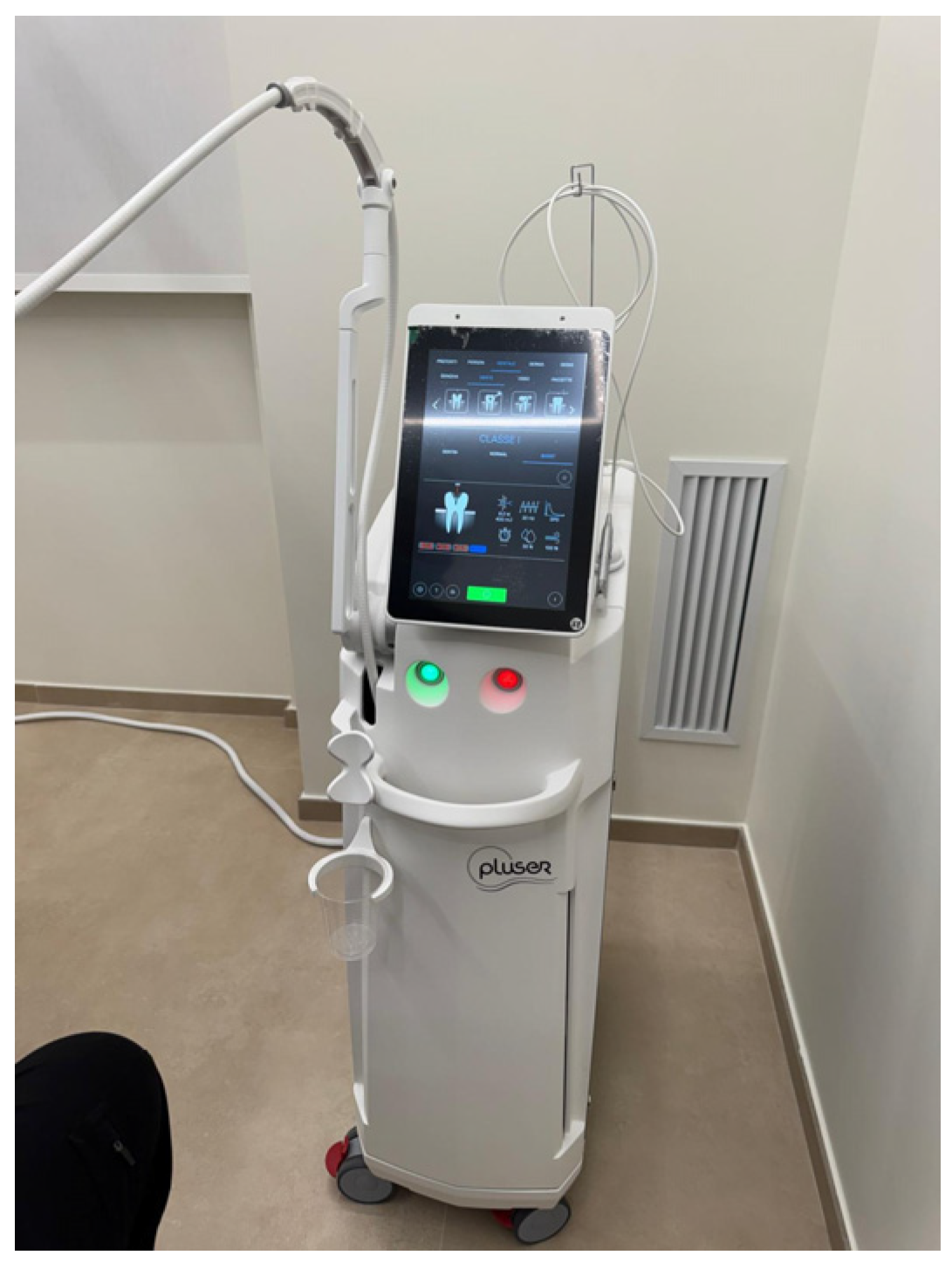

In response to these limitations, technological advances have promoted the development of alternative approaches aimed at enhancing minimally invasive dentistry and improving children’s acceptance of dental procedures [9,10,11]. Among these, the erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) laser has emerged as a promising option, as it allows selective removal of carious tissue while minimizing thermal damage and improving patient comfort (Figure 1) [12,13].

Figure 1.

Modern Er:YAG dental laser system for advanced clinical procedures.

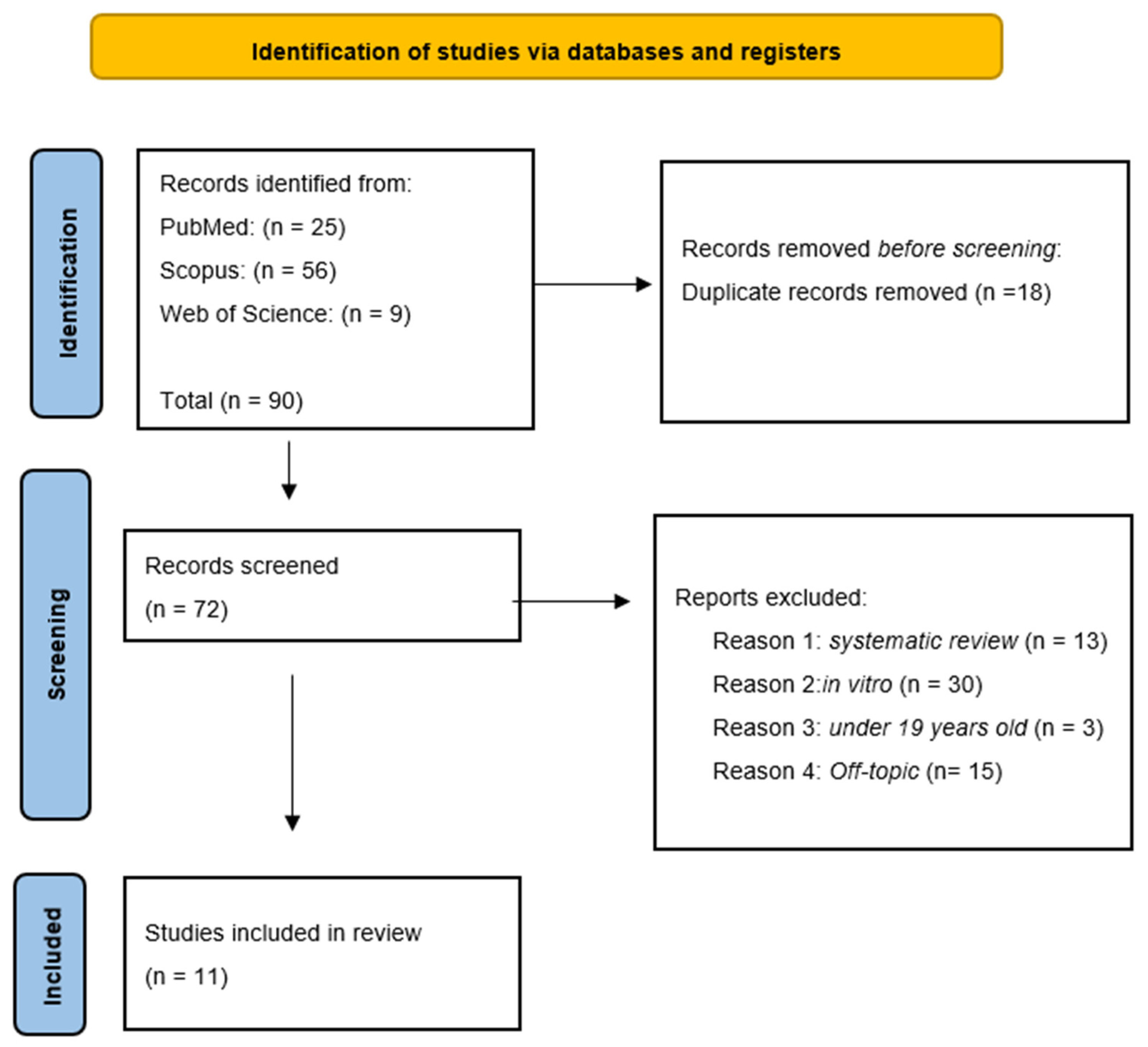

The Er:YAG laser operates at a wavelength of 2940 nm, which coincides with a strong absorption peak of both hydroxyapatite and water, the principal components of enamel and dentin [14,15,16]. This characteristic enables a photothermal ablation mechanism based on micro-explosive events that permit precise and selective removal of demineralized dentin while limiting collateral effects [17,18,19]. The ablation process is primarily driven by rapid vaporization of water within dental hard tissues (Figure 2) [1,2,3,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Figure 2.

The screen displays specific clinical settings including power (8.0 W), frequency (20 Hz), and various treatment categories like Class I-V cavities and composite removal.

Because laser energy is absorbed superficially, tissue cutting occurs with minimal thermal diffusion, thereby reducing the risk of pulpal overheating and often decreasing the need for local anesthesia [2,33,34,35]. Furthermore, the absence of high-frequency noise and mechanical vibration contributes to enhanced patient comfort, and several studies have reported that children show greater tolerance toward laser-assisted procedures compared with conventional rotary instrumentation [20]. These advantages align closely with the clinical objectives of pediatric dentistry and the principles of minimally invasive treatment, particularly in early childhood care [32,36,37,38].

Conversely, the dental turbine remains widely used because of its long-standing clinical familiarity, ease of handling, and high operational speed [39,40]. By mechanically abrading dental tissues through high-speed rotating burs, turbines often generate discomfort, as well as characteristic noise and vibration, which may be poorly tolerated by young patients [23,40]. Although turbines are highly effective in rapidly excavating carious lesions, their lack of selectivity between infected and affected dentin may result in unnecessary removal of sound tooth structure [39,40]. In addition, rotary instrumentation produces a smear layer that can interfere with adhesive bonding and restoration longevity, and frictional heat generation necessitates continuous water cooling [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Despite these disadvantages, dental turbines remain the most accessible and cost-effective instruments in both private and public pediatric dentistry settings [27,41,49,50,51,52].

For these reasons, the comparison between Er:YAG lasers and conventional dental turbines is particularly relevant in pediatric dentistry, where minimal invasiveness, treatment acceptance, and behavioral management are essential considerations [10,53,54]. An increasing number of randomized controlled trials and comparative studies have evaluated the effectiveness of Er:YAG lasers in primary dentition, reporting favorable outcomes in terms of patient acceptance, cavity preparation quality, and restoration integrity [52,55,56,57]. Compared with children treated using rotary burs, those treated with Er:YAG lasers often exhibit reduced anxiety, improved cooperation, and lower levels of perceived pain [51,55,58,59,60]. Moreover, laser-prepared cavities demonstrate advantageous micromorphological characteristics, such as increased surface roughness and the absence of a smear layer, which may enhance adhesive performance [16,17,18,19,52,54].

Despite these reported benefits, the clinical superiority of laser technology over conventional turbines remains a topic of debate [38,61,62]. Although Er:YAG lasers can achieve restoration durability comparable to that obtained with burs and superior patient-reported outcomes, evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicates that laser-assisted procedures often require longer operative times and involve higher acquisition and maintenance costs [36,37,48,58,63]. Additionally, effective laser use demands specific training and careful adjustment of operating parameters [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. As a consequence, considerable variability exists in the adoption of laser technology across different pediatric dental settings [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85].

Therefore, the present systematic review aims to evaluate whether caries removal using erbium-based lasers (Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG) leads to improved clinical and patient-centered outcomes in pediatric dentistry when compared with conventional rotary instruments (high-speed dental turbines). Specifically, this review focuses on intraoperative pain, the need for local anesthesia, anxiety levels, child behavior and cooperation, procedure duration, and the short- to medium-term clinical performance of restorations in primary teeth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The current systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and International Prospective Register of Systematic Review Registry procedures (full ID:1274463) (see Supplementary Materials) [86].

2.2. Search Process

A search of the following databases was conducted in September 2025: PubMed, Web of Science (WOS), and Scopus were examined from 1 January 2010 to 30 November 2025 in order to search articles of the last 15 years (Table 1). The search strategy was created by combining terms relevant to the study’s purpose. The search strategy was designed by integrating terms aligned with the study’s objectives. In the advanced search queries applied across the databases (with the complete search terms provided in Appendix A), the keywords were combined using Boolean operators to capture concepts relevant to the study’s aims (Table 1): (“Er:YAG” OR “Er,Cr:YSGG” OR “erbium laser”) AND (“dental caries” OR caries OR “cavity preparation” OR “caries removal”) AND (rotary OR “air rotor” OR turbine OR “high speed handpiece”).

Table 1.

Indicators for database searches.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The reviewers worked in groups to assess all relevant studies that were evaluated. Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

- Open-access articles;

- Studies written in English;

- Studies conducted in vivo or on humans;

- Case–control studies, cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs);

- Studies published in the last 15 years.

Eligible investigations comprised randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case–control studies involving pediatric patients with carious primary teeth, in which caries removal or cavity preparation performed using erbium-based lasers (Er:YAG or Er,Cr:YSGG) was directly compared with conventional rotary instruments (high-speed dental turbine). Only studies published within the predefined time frame were considered.

Exclusion criteria comprised review articles, case reports or case series, letters or editorials, in vitro and animal studies, investigations conducted in adult populations, and studies not directly comparing erbium laser techniques with rotary instrumentation in pediatric dentistry.

2.4. PICO Question

The PICO format is a framework used in qualitative research to structure clinical research questions. The PICO addressed the question: “In children with dental caries requiring restorative treatment, does caries removal using an erbium laser, compared with conventional rotary instruments (high-speed handpiece), reduce intraoperative pain and the need for local anaesthesia, improve child behaviour/cooperation, and provide comparable operative time and clinical outcomes of the restoration?”.

The PICO question is developed as follows:

- I.

- Population (P): Children with carious primary teeth.

- II.

- Intervention (I): Caries removal using an erbium laser (e.g., Er:YAG or Er,Cr:YSGG).

- III.

- Comparison (C): Conventional caries removal with rotary instruments/high-speed handpiece (turbine).

- IV.

- Outcome (O): Intraoperative pain, need for local anaesthesia, child behaviour/cooperation during treatment, and operative time (and, secondarily, clinical quality of the restoration).

2.5. Data Processing

Four independent reviewers (L.C., D.C., P.D.S, and P.N.) assessed the included studies’ quality using selection criteria, methods of outcome evaluation, and data analysis. This enhanced ‘risk of bias’ tool additionally provides quality standards for selection, performance, detection, reporting, and other biases. All differences were settled through conversation or collaboration with other researchers (G.D., A.P., A.D.I. and A.M.I.). The reviewers screened the records according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The 1.202 selected articles were downloaded into “Zotero 6.0.36” for organization and analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Selection and Characteristics of the Study

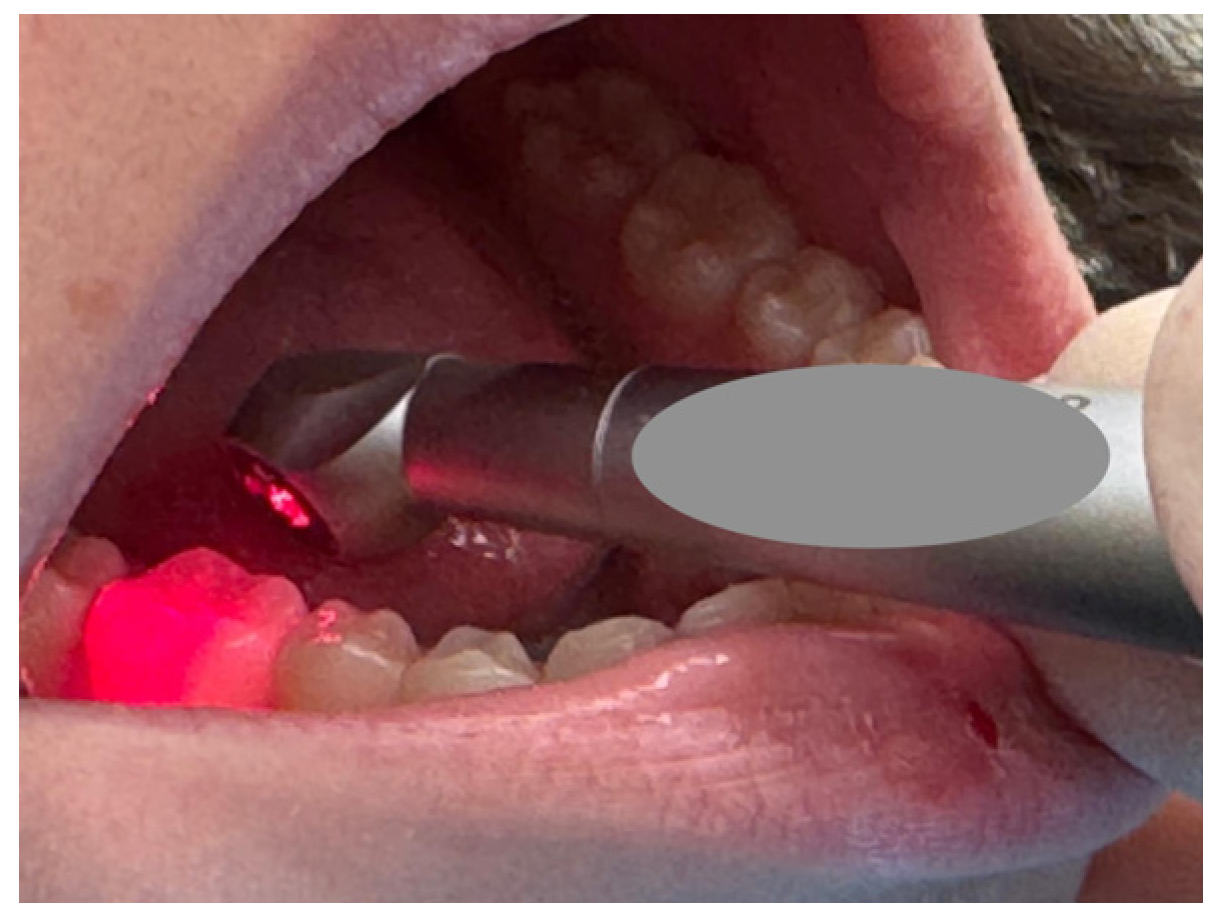

This PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram (Figure 3) illustrates a rigorous and systematic selection process to ensure that only relevant studies were included in the final review. In total, 90 records were identified through database searching: PubMed (n = 25), Scopus (n = 56) and Web of Science (n = 9). After the removal of 18 duplicate records, 72 records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 61 were excluded for the following reasons: systematic reviews (n = 13), in vitro studies (n = 30), studies conducted in adult populations (n = 3), and off-topic articles not related to erbium laser caries removal in paediatric patients (n = 15). Finally, 11 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative review. The selection process and summary of included records are illustrated in Figure 3, while the characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Table 2.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flowchart.

Table 2.

Analysis of the studies included in the Discussion section from 2010 to 2025.

3.2. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias of Included Articles

The methodological quality of the included manuscripts was assessed by a reviewer (L.C.) using risk-of-bias tools tailored to study design. Specifically, the Cochrane RoB 2 (Risk of Bias 2) tool was applied to the randomized trials (Table 3): Belcheva (2014), Valério (2016), Korkut (2018), Johar (2019), Alia (2020), Abdrabuh (2023a), Abdrabuh (2023b), Xu (2024), and Milc (2025). RoB 2 evaluates five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process, (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (3) bias due to missing outcome data, (4) bias in measurement of the outcome, and (5) bias in selection of the reported result, and assigns an overall risk-of-bias judgement categorized as “Low risk of bias,” “Some concerns,” or “High risk of bias.”

Table 3.

Tabular summary of the RoB 2 assessment for 9 studies, evaluated across 5 domains.

In contrast, for the non-randomized/quasi-experimental studies, Bohari (2012) and El-Dehna (2021), the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) tool was used (Table 4). ROBINS-I assesses seven domains: (1) bias due to confounding, (2) bias in selection of participants into the study, (3) bias in classification of interventions, (4) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (5) bias due to missing data, (6) bias in measurement of outcomes, and (7) bias in selection of the reported result, followed by an overall risk-of-bias judgement categorized as “Low,” “Moderate,” “Serious,” “Critical,” or “No information.”

Table 4.

Tabular summary of the ROBINS-I assessment for 2 studies, evaluated across 7 domains.

Overall, the RoB 2 assessment (Table 3) indicated that the randomized trials mostly fell within the “some concerns” range, largely driven by issues commonly affecting pediatric dental trials with subjective outcomes (e.g., incomplete reporting of key randomization details and/or limited blinding of outcome assessment for pain/anxiety measures). In a smaller subset of studies, the overall judgement increased to “high risk of bias,” typically when at least one domain was rated high risk, most frequently related to outcome measurement and/or missing outcome data. For the two non-randomized studies assessed with ROBINS-I (Table 4), Bohari (2012) was judged to have an overall moderate risk of bias, mainly reflecting expected confounding and limited information on some methodological safeguards, whereas El-Dehna (2021) showed an overall serious risk of bias, primarily driven by confounding (non-random allocation features inherent to the split-mouth procedure) and potential deviations from intended interventions. Using two complementary instruments allowed a consistent appraisal of internal validity across heterogeneous designs, ensuring that each study was evaluated with the tool most appropriate to its methodological structure.

4. Discussion

Minimally invasive approaches for caries removal have gained increasing attention in pediatric dentistry, driven by the need to reduce pain, anxiety, and behavioral management challenges while maintaining effective clinical outcomes. Among these approaches, erbium-based lasers (Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG) have been proposed as alternatives to conventional rotary instruments because they can ablate hard dental tissues with minimal vibration, noise, and thermal damage. The studies included in this discussion collectively examine whether these theoretical advantages translate into tangible clinical and behavioral benefits for children undergoing caries removal.

4.1. Effectiveness of Caries Removal and Cavity Quality

Across the included studies, erbium lasers demonstrated comparable effectiveness to conventional rotary instruments in removing carious tissue. Bohari et al. and Valério et al. showed that Er:YAG laser excavation achieved reductions in DIAGNOdent values similar to those obtained with air rotor burs, indicating thorough removal of infected dentin. Similarly, Johar et al. confirmed complete caries removal with both Er,Cr:YSGG laser and conventional handpieces using caries-detection dyes [21,46,53].

Beyond effectiveness, several authors highlighted differences in cavity morphology. Valério et al. reported that laser-prepared cavities were more conservative, with less removal of sound tooth structure, aligning with the principles of minimally invasive dentistry [46]. Importantly, studies focusing on restoration outcomes, such as Abdrabuh et al. (2023) and El-Dehna et al., demonstrated that cavity preparation with lasers did not compromise restoration quality [41,54]. Using modified USPHS or Ryge criteria, both laser- and bur-prepared cavities showed high Alpha scores for marginal adaptation, anatomical form, and secondary caries, even after follow-up periods of up to 12 months. These findings were further corroborated by Xu et al., who reported similar restoration success rates and no increased risk of tooth fractures with laser use [44].

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the included studies employed highly heterogeneous laser parameters, including variations in energy output, pulse frequency, and water/air spray settings. This heterogeneity may have influenced both cutting efficiency and biological response, potentially contributing to variability in reported outcomes across studies. The absence of standardized laser protocols limits direct comparability and makes it difficult to determine whether observed differences are attributable to the laser technique itself or to specific parameter configurations.

4.2. Operative Time and Clinical Efficiency

A consistent finding across nearly all studies was the longer operative time associated with laser-based caries removal. Bohari et al., Valério et al., Johar et al., and Milc et al. all reported significantly longer treatment durations when using erbium lasers compared with rotary instruments [21,46,53,62]. In particular, Milc et al. quantified this difference, noting that laser preparation required approximately 2.5 times longer than turbine-based techniques [62].

Despite this limitation, most authors emphasized that the increased operative time did not negatively affect clinical feasibility. Bohari et al. noted that laser treatment was still faster than chemomechanical methods, while Xu et al. argued that the slower cutting efficiency was offset by improved patient cooperation and reduced need for anesthesia [44,53]. However, it is plausible that differences in laser settings—such as lower energy or frequency chosen to maximize comfort—may partly explain the prolonged operative times observed in some trials. Collectively, these findings suggest that while operative time remains a practical drawback, it may be clinically acceptable in pediatric settings where behavioral management is a priority.

4.3. Pain Perception and Need for Local Anesthesia

Pain reduction emerged as one of the most consistently reported advantages of erbium laser use. Studies employing validated pain scales—including Wong–Baker FACES, VAS, FLACC, and universal pain assessment tools—uniformly demonstrated lower pain scores with laser treatment. Belcheva et al., Korkut et al., and Milc et al. reported striking differences, with a substantial proportion of children experiencing little to no pain during laser procedures [62,79,87]. Notably, Milc et al. observed complete elimination of pain (VAS = 0) in the laser group.

Several studies also reported a reduced need for local anesthesia. Xu et al. and Abdrabuh et al. (2023) found that significantly fewer children requested anesthesia during laser treatment compared with conventional drilling. Although El-Dehna et al. and Alia et al. did not always find statistically significant differences in pain scores, both studies still described a clear clinical trend favoring laser-assisted procedures; these findings underscore the potential of erbium lasers to enhance patient comfort and reduce pharmacological intervention in pediatric dentistry.

It is important to emphasize, however, that pain perception is inherently subjective, particularly in pediatric populations. Most studies relied on self-reported scales or observer-based assessments, which may be influenced by age, cognitive development, previous dental experiences, and contextual factors. This subjectivity represents a relevant limitation and may introduce variability or bias in the estimation of true analgesic differences between laser and rotary techniques.

4.4. Anxiety, Behavioral Response, and Patient Acceptance

Anxiety reduction and improved behavior represent another key advantage of laser-assisted caries removal. Studies assessing anxiety through physiological measures, such as pulse rate, and behavioral scales consistently favored laser use. Alia et al. demonstrated that rotary instruments significantly increased pulse rate, whereas laser treatment caused only minimal changes [88]. Similarly, Abdrabuh et al. (2023) reported lower anxiety scores and better cooperation with laser preparation using Venham’s Dental Anxiety Scale [32].

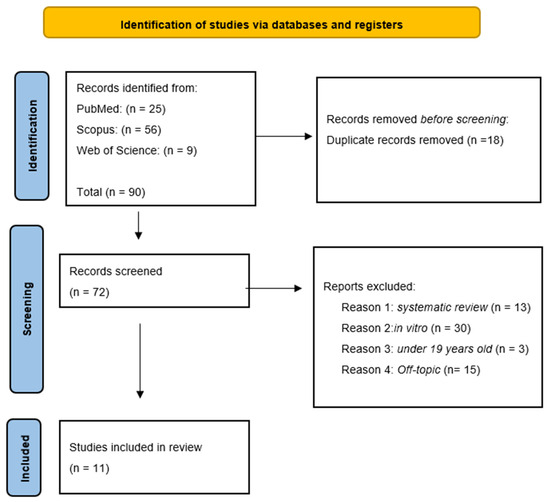

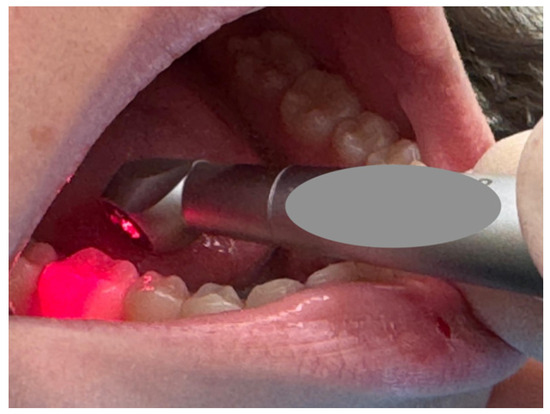

Behavioral improvements were often attributed to the absence of vibration, pressure, and high-pitched noise. Bohari et al., Korkut et al., and Xu et al. all emphasized that these factors contributed to improved child cooperation and a more positive dental experience. Importantly, preference data further supported these observations: Alia et al. reported that 57% of children preferred the laser for future treatments, even when pain differences were minimal [44,53,79,88]. This suggests that acceptance is influenced not only by pain, but also by the overall sensory experience of the procedure (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A close-up view of a dental procedure, showing a dental instrument emitting a red light being applied to a molar inside a patient’s mouth.

Nonetheless, anxiety-related outcomes share similar methodological limitations to pain measures, as they are often based on subjective or semi-objective scales. Emotional state, environmental context, and operator–child interaction may all affect these assessments, warranting cautious interpretation of the magnitude of anxiety reduction attributed to laser use.

4.5. Economic Considerations and Clinical Feasibility

Beyond clinical and behavioral outcomes, the adoption of erbium laser technology must also be considered in light of economic sustainability and feasibility, particularly within public healthcare systems. Although higher acquisition and maintenance costs, longer operative times, and the need for specific training are frequently mentioned as disadvantages, these aspects were only marginally addressed in the included studies. In high-volume pediatric settings, such as public dental services, these factors may limit widespread implementation. However, potential indirect benefits—such as improved cooperation, reduced need for local anesthesia, and fewer interrupted treatments—may partially counterbalance these costs. Dedicated cost-effectiveness analyses are therefore required to clarify whether the improved patient-centered outcomes associated with laser use translate into long-term practical advantages in routine clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to determine whether erbium-based lasers (Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG) offer advantages over conventional rotary instruments for caries removal and cavity preparation in pediatric dentistry, with a focus on patient-centered outcomes and short-term restorative performance. The findings of the included studies consistently support the objectives outlined in the Introduction.

Erbium lasers demonstrated superior performance in reducing intraoperative pain, decreasing the need for local anesthesia, and improving child comfort, cooperation, and anxiety management—directly addressing the clinical and behavioral challenges central to pediatric dental care. Although operative time was generally longer with laser use, this drawback did not compromise restoration quality or short-term success, meeting the objective of evaluating both clinical efficiency and restorative outcomes. Moreover, restorations placed in laser-prepared cavities showed comparable integrity to those prepared with traditional rotary instruments over short-term follow-up.

Overall, the evidence indicates that erbium lasers represent a clinically effective and child-friendly alternative to conventional rotary tools, aligning with the goals stated in the Introduction to enhance minimally invasive, behavior-oriented dental care for pediatric patients. Future research with standardized protocols, larger samples, and extended follow-up will be essential to clarify long-term outcomes and further refine clinical decision-making.

6. Future Limitations (Integrated with Study Limitations)

Despite the promising clinical and patient-centered benefits reported for erbium lasers, several limitations of the present review must be acknowledged. First, the included studies exhibited substantial methodological heterogeneity, particularly in study design (parallel vs. split-mouth), laser type (Er:YAG vs. Er,Cr:YSGG), device settings, operative protocols, restorative materials, and outcome measures. This variability limits direct comparability among trials, also preventing a quantitative meta-analysis. Additionally, many studies enrolled relatively small samples and provided only short follow-up periods—often up to 6–12 months—reducing the ability to assess long-term restoration performance and treatment stability.

Blinding of operators and participants was inherently unfeasible, introducing potential performance and detection bias, especially for subjective outcomes such as pain, anxiety, and child cooperation. In several studies, incomplete reporting of randomization procedures, allocation concealment, and pre-specified outcomes contributed to uncertainties during risk-of-bias assessment. Furthermore, heterogeneity in evaluation methods and outcome measures made standardization challenging.

Beyond the limitations of the current evidence base, future research should aim to overcome these issues by conducting well-designed, adequately powered randomized controlled trials with standardized laser parameters, harmonized outcome measures, and longer follow-up periods. Additional investigations should also explore cost-effectiveness, operator learning curves, and practical implementation challenges, which remain understudied yet critical for integrating laser technology into routine pediatric dental practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children13020258/s1, PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N., A.M.I., L.C., D.C., P.D.S., F.I., A.P.; G.M., A.D.I. and G.D.; methodology G.D., A.M.I., P.N., A.P., F.I., L.C. and D.C.; software, A.P., F.I., P.D.S., D.C., L.C., P.N., A.M.I.; validation, G.D., D.C., A.P., P.D.S., A.M.I., F.I., and L.C.; formal analysis, L.C., P.D.S., A.M.I., G.D., and D.C.; resources, D.C., P.D.S., A.P., A.M.I., F.I., G.M., A.D.I. and L.C.; data curation, L.C., D.C., A.P., A.M.I., P.N., F.I. and G.D.; writing original draft preparation A.P., P.N., P.D.S., A.M.I., and F.I.; writing review and editing, G.D., P.N., P.D.S., L.C., A.M.I., F.I. and D.C.; visualization, D.C., P.N., P.D.S., A.M.I., F.I. and L.C.; supervision, G.D., D.C., P.D.S., L.C., P.N., A.M.I., F.I., G.M., A.D.I. and A.P.; project administration, P.D.S., P.N., D.C., A.M.I., F.I. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADA | American Dental Association |

| DIAGNOdent | Laser fluorescence device for caries detection |

| Er,Cr:YSGG | Erbium, Chromium-doped Yttrium Scandium Gallium Garnet |

| Er:YAG | Erbium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet |

| FLACC | Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| ROBINS-I | Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions |

| RoB 2 | Risk of Bias 2 tool |

| USPHS | United States Public Health Service criteria |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| WBFPRS | Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale |

| WOS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. PubMed Query String

(“Er:YAG”[All Fields] OR “Er,Cr:YSGG”[All Fields] OR “erbium laser”[All Fields]) AND (“dental caries”[MeSH Terms] OR “dental caries”[All Fields] OR caries[All Fields] OR “cavity preparation”[All Fields] OR “caries removal”[All Fields]) AND (“rotary”[All Fields] OR “air rotor”[All Fields] OR turbine[All Fields] OR “high speed handpiece”[All Fields]).

Appendix A.2. Scopus Query String

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Er:YAG” OR “Er,Cr:YSGG” OR “erbium laser”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“dental caries” OR caries OR “cavity preparation” OR “caries removal”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (rotary OR “air rotor” OR turbine OR “high speed handpiece”).

Appendix A.3. Web of Science Query String

ALL=(“Er:YAG” OR “Er,Cr:YSGG” OR “erbium laser”) AND ALL=(“dental caries” OR caries OR “cavity preparation” OR “caries removal”) AND ALL=(“rotary” OR “air rotor” OR turbine OR “high speed handpiece”).

References

- Dederich, D.N.; Bushick, R.D. Lasers in Dentistry: Separating Science from Hype. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 204–212; quiz 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appukuttan, D.P. Strategies to Manage Patients with Dental Anxiety and Dental Phobia: Literature Review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2016, 8, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, D.J. Lasers in Dentistry. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2005, 26, 429–435; quiz 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhegova, G.G.; Rashkova, M.R. Er-YAG laser and dental caries treatment of permanent teeth in childhood. J. IMAB 2014, 21, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinknecht, R.A.; Klepac, R.K.; Alexander, L.D. Origins and Characteristics of Fear of Dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1973, 86, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boj, J.R.; Poirier, C.; Hernandez, M.; Espasa, E.; Espanya, A. Review: Laser Soft Tissue Treatments for Paediatric Dental Patients. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2011, 12, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilotpol, K.; Sunil Kumar, Y.; Manisha, U.; Jyoti, S.; Swarga Jyoti, D.; Manjula, D. Lasers in Paediatric Dentistry, a Boon or a Bane: A Systemic Review. Open Access J. Dent. Sci. 2019, 4, 000217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, W.H.; Martorano, F.; Cotton, E.K. Management of Life-Threatening Asthma with Intravenous Isoproterenol Infusions. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1976, 130, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami, F.; Ebrahimi, H.; Aghazadeh, A.; Sooratgar, A.; Chiniforush, N. Evaluation of the Effect of the Photobiomodulation Therapy on the Pain Related to Dental Injections: A Preliminary Clinical Trial. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 59, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosskull Hjertton, P.; Bågesund, M. Er:YAG Laser or High-Speed Bur for Cavity Preparation in Adolescents. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2013, 71, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, A.R.; Baseren, M.; Gorucu, J. Clinical Comparison of Bur- and Laser-Prepared Minimally Invasive Occlusal Resin Composite Restorations: Two-Year Follow-Up. Oper. Dent. 2010, 35, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.J.P.; Matthews, S.; Pitts, N.B.; Longbottom, C.; Nugent, Z.J. A Clinical Evaluation of an Erbium:YAG Laser for Dental Cavity Preparation. Br. Dent. J. 2000, 188, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarano, A.; Lorusso, F.; Inchingolo, F.; Postiglione, F.; Petrini, M. The Effects of Erbium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser (Er: YAG) Irradiation on Sandblasted and Acid-Etched (SLA) Titanium, an In Vitro Study. Materials 2020, 13, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Hossain, M.; Suzuki, N.; Kinoshita, J.-I.; Nakamura, Y.; Matsumoto, K. Removal of Carious Dentin by Er:YAG Laser Irradiation with and without CarisolvTM. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 2001, 19, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhairy, F.; Naseem, M.; Bin-Shuwaish, M.; Vohra, F. Efficacy of Er Cr: YSGG Laser Therapy at Different Frequency and Power Levels on Bond Integrity of Composite to Bleached Enamel. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 22, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, R.L.; Monghini, E.M.; Pecora, J.D.; Palma-Dibb, R.G.; Borsatto, M.C. Shear Bond Strength to Enamel of Primary Teeth Irradiated with Varying Er:YAG Laser Energies and SEM Examination of the Surface Morphology: An in Vitro Study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2005, 23, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibst, R.; Keller, U. Experimental Studies of the Application of the Er:YAG Laser on Dental Hard Substances: I. Measurement of the Ablation Rate. Lasers Surg. Med. 1989, 9, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.T.; Deutsch, T.F. Er:YAG Laser Ablation of Tissue: Measurement of Ablation Rates. Lasers Surg. Med. 1989, 9, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Tu, S.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, H. Effect of Nanosecond- and Microsecond-Pulse Er,Cr:YSGG Laser Ablation on Dentin Shear Bond Strength of Universal Adhesives. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3285–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, J.; Moriya, K.; Jayawardena, J.A.; Wijeyeweera, R.L. Clinical Application of Er:YAG Laser for Cavity Preparation in Children. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 2003, 21, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, S.; Goswami, M.; Kumar, G.; Dhillon, J.K. Caries Removal by Er,Cr:YSGG Laser and Air-Rotor Handpiece Comparison in Primary Teeth Treatment: An in Vivo Study. Laser Ther. 2019, 28, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvisalo, J.; Saris, N.E. Action of Propranolol on Mitochondrial Functions--Effects on Energized Ion Fluxes in the Presence of Valinomycin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975, 24, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, B.; Asgari, A. Restorative Dentistry for Children Using a Hard Tissue Laser. Alpha Omegan 2008, 101, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacboson, B.; Berger, J.; Kravitz, R.; Ko, J. Laser Pediatric Class II Composites Utilizing No Anesthesia. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2005, 28, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Izumi, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Watanabe, K. Short-Term Histomorphological Effects of Er:YAG Laser Irradiation to Rat Coronal Dentin-Pulp Complex. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2004, 97, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatovich, V.F. Enhancement of the Antigenic Activity and Virulence of the Vaccine Strain E of Rickettsia Prow Azeki by Passages in Cell Culture. Acta Virol. 1975, 19, 481–485. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman, J.; Lavorel, J. Identification of the 120 Mus Phase in the Decay of Delayed Fluorescence in Spinach Chloroplasts and Subchloroplast Particles as the Intrinsic Back Reaction. The Dependence of the Level of This Phase on the Thylakoids Internal pH. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 408, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob Deeb, J.; Reddy, N.; Kitten, T.; Carrico, C.K.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Viability of Bacteria Associated with Root Caries after Nd:YAG Laser Application in Combination with Variousantimicrobial Agents: An in Vitro Study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2023, 60, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankle, R.T. Nutrition Education in the Medical School Curriculum: A Proposal for Action: A Curriculum Design. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1976, 29, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaini, C.; Riceputi, D.; Lupi-Pegurier, L.; Rocca, J.P. Patient Responses to Er:YAG Laser When Used for Conservative Dentistry. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohr, H.; Breull, W. Effect of Etafenone on Total and Regional Myocardial Blood Flow. Arzneimittelforschung 1975, 25, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Felemban, O.M.; El Meligy, O.A.; Abdrabuh, R.E.; Farsi, N.M. Evaluation of the Erbium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser and the Conventional Method on Pain Perception and Anxiety Level in Children during Caries Removal: A Randomized Split-Mouth Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2023, 16, S39–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumazaki, M.; Toyoda, K. Removal of Hard Dental Tissue (Cavity Preparation) with the Er: YAG Laser. J. Jpn. Soc. Laser Dent. 1995, 6, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cademartori, M.G.; Da Rosa, D.P.; Oliveira, L.J.C.; Corrêa, M.B.; Goettems, M.L. Validity of the Brazilian Version of the Venham’s Behavior Rating Scale. Int. J. Paed Dent. 2017, 27, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijur, P.E.; Silver, W.; Gallagher, E.J. Reliability of the Visual Analog Scale for Measurement of Acute Pain. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2001, 8, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Casamassima, L.; Nardelli, P.; Ciccarese, D.; De Sena, P.; Inchingolo, F.; Palermo, A.; Severino, M.; Maspero, C.M.N.; et al. Effectiveness of Dental Restorative Materials in the Atraumatic Treatment of Carious Primary Teeth in Pediatric Dentistry: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Ma, Z.; Lv, B.; Xie, M. Er:YAG Laser Application in Caries Removal and Cavity Preparation in Children: A Meta-Analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, L.C. Laser Physics and a Review of Laser Applications in Dentistry for Children. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2011, 12, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebich, T.; Lack, L.; Hansen, K.; Zajamšek, B.; Lovato, N.; Catcheside, P.; Micic, G. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Wind Turbine Noise Effects on Sleep Using Validated Objective and Subjective Sleep Assessments. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanboga, I.; Eren, F.; Altınok, B.; Peker, S.; Ertugral, F. The Effect of Low Level Laser Therapy on Pain during Dental Tooth-Cavity Preparation in Children. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2011, 12, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dehna, A.; Alyaski, M.; Mostafa, M. Clinical Evaluation of Laser Versus Conventional Cavity Preparation Methods in Primary Teeth Restorations. Al-Azhar Dent. J. Girls 2021, 8, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, C.; Pagano, S.; Bozza, S.; Ciurnella, E.; Lomurno, G.; Capobianco, B.; Coniglio, M.; Cianetti, S.; Marinucci, L. Use of the Er:YAG Laser in Conservative Dentistry: Evaluation of the Microbial Population in Carious Lesions. Materials 2021, 14, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Morolla, R.; Riccaldo, L.; Guglielmo, M.; Palumbo, I.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G. Pre-Formed Crowns and Pediatric Dentistry: A Systematic Review of Different Techniques of Restorations. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2025, 49, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Ren, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, M. Clinical Application of Er:YAG Laser and Traditional Dental Turbine in Caries Removal in Children. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warth, J.; Desforges, J.F. Determinants of Intracellular pH in the Erythrocyte. Br. J. Haematol. 1975, 29, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valério, R.A.; Borsatto, M.C.; Serra, M.C.; Polizeli, S.A.F.; Nemezio, M.A.; Galo, R.; Aires, C.P.; Dos Santos, A.C.; Corona, S.A.M. Caries Removal in Deciduous Teeth Using an Er:YAG Laser: A Randomized Split-Mouth Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2016, 20, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.J.; Hick, P.E. Inhibition of Aldehyde Reductase by Acidic Metabolites of the Biogenic Amines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975, 24, 1731–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Li, L.; Yuan, H.; Tao, S.; Cheng, Y.; He, L.; Li, J. Erbium Laser Technology vs Traditional Drilling for Caries Removal: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2017, 17, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwass, D.R.; Leichter, J.W.; Purton, D.G.; Swain, M.V. Evaluating the Efficiency of Caries Removal Using an Er:YAG Laser Driven by Fluorescence Feedback Control. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, F.; Braun, A.; Lotz, G.; Kneist, S.; Jepsen, S.; Eberhard, J. Evaluation of Selective Caries Removal in Deciduous Teeth by a Fluorescence Feedback-Controlled Er:YAG Laser in Vivo. Clin. Oral Investig. 2008, 12, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommisch, H.; Peus, K.; Kneist, S.; Krause, F.; Braun, A.; Hedderich, J.; Jepsen, S.; Eberhard, J. Fluorescence-controlled Er:YAG Laser for Caries Removal in Permanent Teeth: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 116, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraba, A.; Perhavec, T.; Chieffi, N.; Ferrari, M.; Anić, I.; Miletić, I. Ablative Potential of Four Different Pulses of Er:YAG Lasers and Low-Speed Hand Piece. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2012, 30, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohari, M.R.; Chunawalla, Y.K.; Ahmed, B.M.N. Clinical Evaluation of Caries Removal in Primary Teeth Using Conventional, Chemomechanical and Laser Technique: An in Vivo Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2012, 13, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdrabuh, R.; El Meligy, O.; Farsi, N.; Bakry, A.S.; Felemban, O.M. Restoration Integrity in Primary Teeth Prepared Using Erbium/Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet Laser: A Randomized Split-Mouth Clinical Study. Children 2023, 10, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.; Coelho, A.; Lima, R.; Amaro, I.; Paula, A.; Marto, C.M.; Sousa, J.; Spagnuolo, G.; Marques Ferreira, M.; Carrilho, E. Efficacy and Patient’s Acceptance of Alternative Methods for Caries Removal—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patano, A.; Malcangi, G.; De Santis, M.; Morolla, R.; Settanni, V.; Piras, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G.; et al. Conservative Treatment of Dental Non-Carious Cervical Lesions: A Scoping Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patano, A.; Malcangi, G.; Sardano, R.; Mastrodonato, A.; Garofoli, G.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Di Venere, D.; Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G.; et al. White Spots: Prevention in Orthodontics-Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, J.E.; Ramsay, C.R.; Ricketts, D.; Banerjee, A.; Deery, C.; Lamont, T.; Boyers, D.; Marshman, Z.; Goulao, B.; Banister, K.; et al. Selective Caries Removal in Permanent Teeth (SCRiPT) for the Treatment of Deep Carious Lesions: A Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial in Primary Care. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnie, K.A.; Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; Uman, L.S.; Parker, J.A. Psychological Interventions for Needle-Related Procedural Pain and Distress in Children and Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2020, CD005179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Ronsivalle, V.; Fiorillo, L.; Arcuri, C. Different Uses of Conscious Sedation for Managing Dental Anxiety During Third-Molar Extraction: Clinical Evidence and State of the Art. J. Craniofac Surg. 2024, 35, 2524–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montedori, A.; Abraha, I.; Orso, M.; D’Errico, P.G.; Pagano, S.; Lombardo, G. Lasers for Caries Removal in Deciduous and Permanent Teeth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD010229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milc, A.; Kotuła, J.; Kiryk, J.; Popecki, P.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Kotuła, K.; Dominiak, M.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Treatment of Deciduous Teeth in Children Using the Er:YAG Laser Compared to the Traditional Method: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa-Faria, P.; Viana, K.A.; Raggio, D.P.; Hosey, M.T.; Costa, L.R. Recommended Procedures for the Management of Early Childhood Caries Lesions—A Scoping Review by the Children Experiencing Dental Anxiety: Collaboration on Research and Education (CEDACORE). BMC Oral. Health 2020, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMeester, T.R.; Johnson, L.F. Evaluation of the Nissen Antireflux Procedure by Esophageal Manometry and Twenty-Four Hour pH Monitoring. Am. J. Surg. 1975, 129, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curylofo-Zotti, F.A.; Oliveira, V.D.C.; Marchesin, A.R.; Borges, H.S.; Tedesco, A.C.; Corona, S.A.M. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Green Tea–Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles on Caries-Related Microorganisms and Dentin after Er:YAG Laser Caries Removal. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.W.; Pietranico, R.; Mukerji, A. Studies of Oxygen Binding Energy to Hemoglobin Molecule. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1975, 66, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armfield, J.; Heaton, L. Management of Fear and Anxiety in the Dental Clinic: A Review. Aust. Dent. J. 2013, 58, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.R.; Slotkin, T.A. Maturation of the Adrenal Medulla--IV. Effects of Morphine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975, 24, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigdor, H.; Abt, E.; Ashrafi, S.; Walsh, J.T. The Effect of Lasers on Dental Hard Tissues. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1993, 124, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmann, U.N.; DiDonato, S.; Herschkowitz, N.N. Effect of Chloroquine on Cultured Fibroblasts: Release of Lysosomal Hydrolases and Inhibition of Their Uptake. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1975, 66, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Liu, L.; Nie, X.; Zhang, L.; Deng, M.; Chen, Y. Effect of Pulse Nd:YAG Laser on Bond Strength and Microleakage of Resin to Human Dentine. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2010, 28, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van As, G. Erbium Lasers in Dentistry. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 48, 1017–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, J.M. The Effect of Adrenaline and of Alpha- and Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents on ATP Concentration and on Incorporation of 32Pi into ATP in Rat Fat Cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975, 24, 1659–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Share, J.B. Review of Drug Treatment for Down’s Syndrome Persons. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 1976, 80, 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Nazemisalman, B.; Farsadeghi, M.; Sokhansanj, M. Types of Lasers and Their Applications in Pediatric Dentistry. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 6, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marniemi, J.; Parkki, M.G. Radiochemical Assay of Glutathione S-Epoxide Transferase and Its Enhancement by Phenobarbital in Rat Liver in Vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975, 24, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukomska-Szymanska, M.; Radwanski, M.; Kharouf, N.; Mancino, D.; Tassery, H.; Caporossi, C.; Inchingolo, F.; De Almeida Neves, A.; Chou, Y.; Sauro, S. Evaluation of Physical–Chemical Properties of Contemporary CAD/CAM Materials with Chromatic Transition “Multicolor”. Materials 2023, 16, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, R.J. Identification of Adenylate Cyclase-Coupled Beta-Adrenergic Receptors with Radiolabeled Beta-Adrenergic Antagonists. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975, 24, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, E.; Gezgin, O.; Özer, H.; Şener, Y. Evaluation of Er:YAG Lasers on Pain Perception in Pediatric Patients during Caries Removal: A Split-Mouth Study. Acta Odontol. Turc. 2018, 35, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korelitz, B.I.; Sommers, S.C. Responses to Drug Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. Evaluation by Rectal Biopsy and Histopathological Changes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1975, 64, 365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, T.; Ishii, K.; Yoshikawa, K.; Yasuo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Awazu, K. In Vitro Study on Selective Removal of Bovine Demineralized Dentin Using Nanosecond Pulsed Laser at Wavelengths around 5.8 Μm for Realizing Less Invasive Treatment of Dental Caries. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadley, J.; Young, D.A.; Eversole, L.R.; Gornbein, J.A. A laser-powered hydrokinetic system. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 131, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Matys, J. The Effect of Er:YAG Lasers on the Reduction of Aerosol Formation for Dental Workers. Materials 2021, 14, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, I.C.; Parker, P.E.; Weidner, W.J.; Dabney, J.M.; Scott, J.B.; Haddy, F.J. Coronary Vascular and Myocardial Responses to Carotid Body Stimulation in the Dog. Am. J. Physiol. 1975, 229, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorofeyeva, L.V. Obtaining of Measles Virus Haemagglutinin from Strain L-16 Grown in Primary Cell Cultures. Acta Virol. 1975, 19, 497. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcheva, A.; Shindova, M. Pain perception of pediatric patients during cavity preparation with Er:YAG laser and conventional rotary instruments. J. IMAB 2014, 20, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jabeen, S.; Suresh, S.; Alia, S. Comparison of Pain and Anxiety Level Induced by Laser vs Rotary Cavity Preparation: An In Vivo Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 13, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.