Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Perioperative antibiotics do not significantly reduce postoperative complications after hypospadias repair.

- No clear benefit was observed for preoperative, postoperative, or combined antibiotic regimens.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Routine antibiotic use in hypospadias surgery may be unnecessary.

- A selective, risk-based antibiotic strategy supports antimicrobial stewardship without compromising outcomes.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: The role, timing, and duration of antibiotic therapy in hypospadias repair remain controversial, with substantial variability in clinical practice and a lack of evidence-based guidelines. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate whether preoperative, postoperative, or combined perioperative antibiotic regimens influence postoperative outcomes after hypospadias repair. Methods: A systematic literature search of PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines to identify studies published between 2000 and 2025 that reported on perioperative antibiotic administration in pediatric patients undergoing hypospadias surgery. Three comparisons were assessed: (i) postoperative antibiotics versus no antibiotics, (ii) preoperative antibiotics versus no antibiotics, and (iii) combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics versus no antibiotics. Outcomes included infectious complications, wound dehiscence, urethrocutaneous fistula, meatal or urethral stenosis, and other postoperative complications. Random-effects meta-analyses were performed, with pooled odds ratios reported together with 95% confidence intervals. Results: Ten studies comprising a total of 9493 patients were included. Perioperative antibiotic use was not associated with a significant reduction in infectious complications (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.63–1.44; p = 0.81), urethrocutaneous fistula (OR 1.89, 95% CI 0.87–4.12; p = 0.10), or wound dehiscence (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.98–2.35; p = 0.06) compared with no antibiotic use. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis alone did not result in a reduction in infectious complications or wound dehiscence. Combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy did not demonstrate a clear benefit over no antibiotics in terms of infectious complications, although available data were very limited. Conclusions: Routine perioperative antibiotic therapy does not significantly reduce postoperative complications after hypospadias repair. These findings support a selective, risk-based approach to antibiotic use rather than routine administration in hypospadias surgery. Further well-designed prospective studies are needed to establish evidence-based perioperative antibiotic protocols in pediatric hypospadias surgery.

1. Introduction

Hypospadias is one of the most common congenital anomalies of the male genitalia, and surgical repair represents the definitive treatment to restore urethral function and achieve satisfactory cosmetic outcomes [1,2,3]. Although advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care have improved outcomes over time, postoperative complications—including infectious complications, wound dehiscence, urethrocutaneous fistula (UCF), and meatal or urethral stenosis—remain a significant clinical concern [4,5]. Their incidence varies widely across published series and is influenced by multiple factors, including hypospadias severity, surgical technique, tissue handling, urinary diversion, and perioperative management [6,7,8,9,10]. Perioperative antibiotic therapy is commonly employed in hypospadias surgery with the aim of reducing postoperative infections and improving surgical outcomes. However, despite its widespread use, substantial variability exists in clinical practice regarding the indication, timing, and duration of antibiotic administration [11,12]. Strategies range from single-dose preoperative prophylaxis to prolonged postoperative antibiotic therapy, or even to the complete omission of antibiotics in selected cases. This heterogeneity reflects the lack of clear, procedure-specific, evidence-based recommendations [13,14]. Given the widespread but variable use of perioperative antibiotics in hypospadias repair, the absence of clear evidence-based guidelines, and the heterogeneous and sometimes conflicting results reported in the literature, a systematic evaluation of the available evidence is warranted. In this context, a comprehensive synthesis of the existing evidence is needed to clarify whether routine perioperative antibiotic therapy is justified in hypospadias surgery or whether a more selective and individualized approach should be preferred.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate whether antibiotic administration—preoperative, postoperative, or combined pre- and postoperative—influences postoperative outcomes after hypospadias surgery, compared with alternative or no antibiotic regimens.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD420251266161) and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A full study protocol was written and uploaded to PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251266161 and accessed on 15 December 2025).

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive electronic literature search was conducted across the PubMed, Scopus, MEDLINE, Embase and Web of Science databases to identify studies reporting on perioperative antibiotic administration in pediatric patients undergoing hypospadias surgery. The final database search was conducted on 30 September 2025. The search strategy adopted the following keywords consistent with MeSH terms: (antibiotic prophylaxis OR anti-bacterial agents OR antibiotics) AND (hypospadias OR urethral repair OR urethroplasty OR postoperative complications OR urethrocutaneous fistula OR wound infection OR wound dehiscence) AND (humans OR children OR pediatrics). The search covered a 25-year period (from 1 January 2000 to 31 March 2025) to ensure a comprehensive identification of all relevant studies on perioperative antibiotic use in hypospadias repair. The reference lists of relevant studies were manually reviewed to identify additional eligible studies, and duplicate records were excluded. The full electronic search strategies for all databases are provided in the Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Study Selection

Study selection was conducted independently by three reviewers (MSC, VM, and ME). After removal of duplicate records, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (MSC and VM), followed by full-text assessment. A third reviewer (ME) verified the consistency of study selection. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or, when necessary, by consultation with a senior author (CE). Inter-rater reliability during the abstract screening phase was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, which demonstrated substantial agreement (κ = 0.79). The full texts of potentially eligible studies were subsequently assessed in detail according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study eligibility was defined following the PICOS framework:

- -

- Population: Pediatric patients (age ≤ 18 years) diagnosed with hypospadias undergoing surgical repair.

- -

- Intervention: Preoperative antibiotic therapy, postoperative antibiotic therapy, or combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy.

- -

- Comparison/Control: No antibiotic therapy or alternative perioperative antibiotic regimens.

- -

- Outcome(s): Infectious complications [bacteriuria, urinary tract infection (UTI), wound infection (WI), surgical site infection (SSI)], wound dehiscence, UCF, meatal/urethral stenosis, and other postoperative complications.

- -

- Study design: Comparative clinical studies including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective cohort studies, and retrospective studies. Only English-language publications were considered eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria were studies with unavailable full texts, studies focused on adult patients (>18 years) undergoing hypospadias repair or patients undergoing urethral reconstruction for conditions other than hypospadias, studies exclusively including patients with complex disorders of sex development or associated major urogenital anomalies requiring staged or non-standard reconstruction and studies with incomplete outcome data or not available in English. We also excluded case reports, small case series, reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and non–peer-reviewed articles.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a predefined standardized spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, version 15.4). Extracted variables included author and publication details, study design, and patient characteristics (sample size, age, hypospadias severity, surgical technique, and type and duration of urinary diversion), as well as antibiotic regimens (no antibiotics, preoperative antibiotics alone, postoperative antibiotics alone, or combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics), and reported postoperative outcomes. For continuous variables, median values with interquartile ranges were extracted when available. Data extraction was independently performed by three reviewers (MSC, VM, and ME) using the standardized form to ensure consistency. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus, with arbitration by a senior author (CE) when required. Inter-rater reliability for the data extraction process was assessed and demonstrated a high level of agreement (κ = 0.81).

2.4. Study Endpoints

The primary endpoints comprised variables related to antibiotic regimens, including the type, modality and duration of administration. Secondary endpoints included postoperative complications following hypospadias repair, namely infectious complications, UCF, wound dehiscence, meatal or urethral stenosis, and other postoperative complications as defined by the individual studies. Infectious complications were defined as a composite outcome including bacteriuria, UTI, WI, and SSI, according to the study-specific definitions.

The present systematic review was designed to address the following key research questions: (1) Does perioperative antibiotic therapy reduce postoperative complications compared with no antibiotic use? (2) Is there a difference in outcomes between preoperative antibiotics alone and combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics? (3) Does combined pre and postoperative antibiotic therapy provide additional benefit compared with postoperative antibiotics alone?

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Quality assessment was performed independently by three reviewers (MSC, VM and ME), with any discrepancies resolved through discussion. Interobserver agreement was high across all assessed domains.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.4. For dichotomous outcomes, effect estimates were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), while mean differences were reported for continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of categorical variables, and a p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Reporting bias was evaluated through visual inspection of funnel plots and, when at least three comparative studies were available, formally assessed using Egger’s regression asymmetry test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of small-study effects. Ethical approval was not required, as this study was a systematic review based exclusively on previously published data.

2.7. Management of Heterogeneity

Given the expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity among the included studies—related to differences in study design, hypospadias severity, surgical techniques, antibiotic regimens, and outcome definitions—specific strategies were adopted to manage heterogeneity in the quantitative synthesis. A random-effects model was applied for all meta-analyses to account for between-study variability. The degree of statistical heterogeneity across the included studies was formally assessed using the χ2 test and quantified with the I2 statistic, with values > 50% considered indicative of substantial heterogeneity. To further explore potential sources of heterogeneity, predefined subgroup analyses were conducted according to the timing of antibiotic administration, including: (1) postoperative antibiotics alone versus no antibiotics, (2) preoperative antibiotics alone versus no antibiotics, and (3) combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics versus no antibiotics. These subgroup analyses were selected a priori based on clinically relevant differences in antibiotic strategies and were performed when at least two comparative studies were available for pooling. In addition, outcomes were analyzed separately to avoid inappropriate pooling of clinically heterogeneous endpoints. When the number of studies was insufficient to support formal subgroup or sensitivity analyses, results were interpreted descriptively and with appropriate caution.

2.8. Certainty of Evidence Assessment

A formal certainty-of-evidence assessment (e.g., GRADE approach) was not performed. Given the substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity across the included studies, the predominance of observational study designs, and the limited number of studies available for several comparisons, a formal grading of evidence certainty was considered unlikely to provide meaningful or reliable estimates. Results were interpreted by integrating effect sizes, CIs, consistency across analyses, and the risk of bias of the included studies.

3. Results

3.1. Study and Patient Characteristics

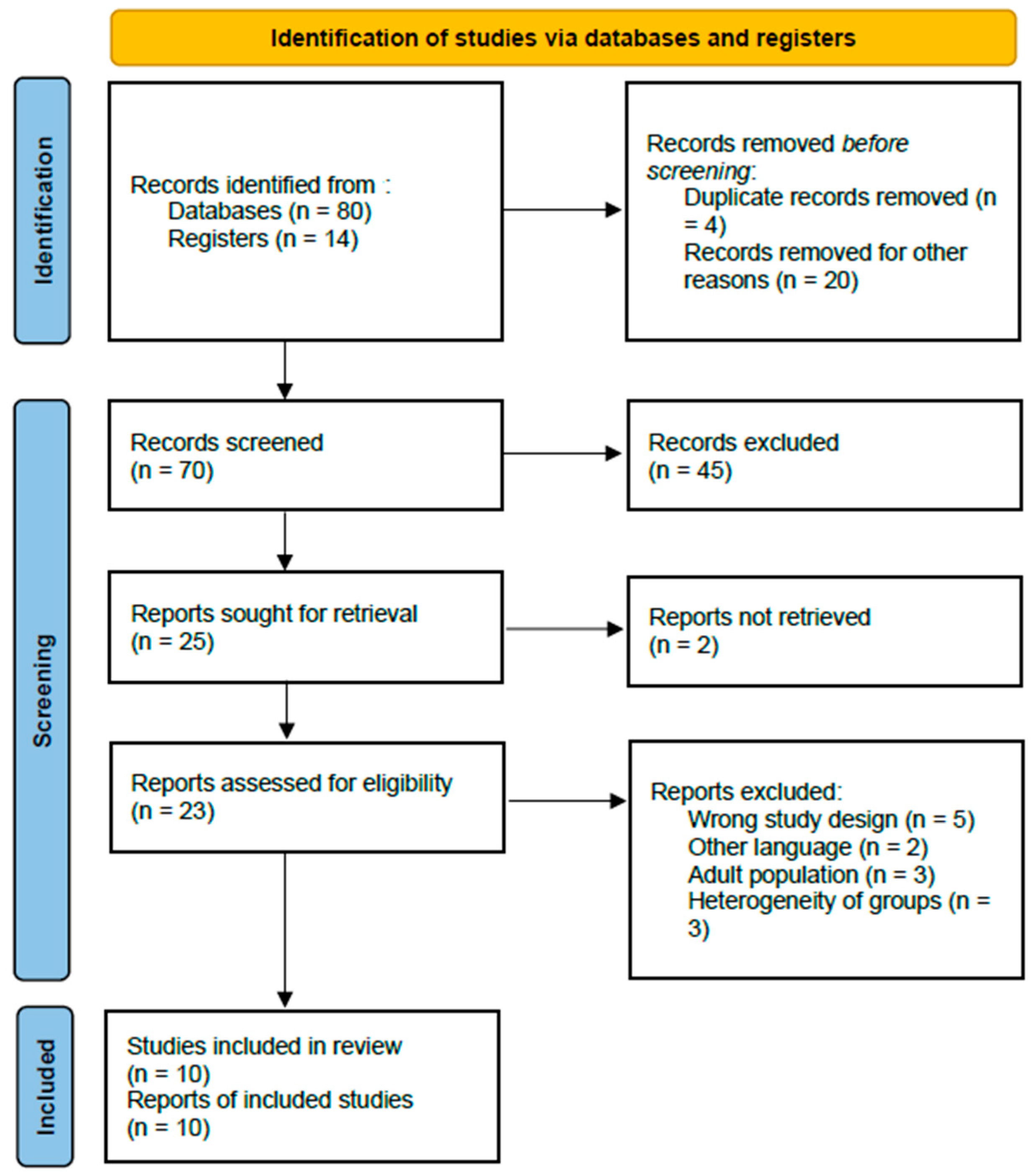

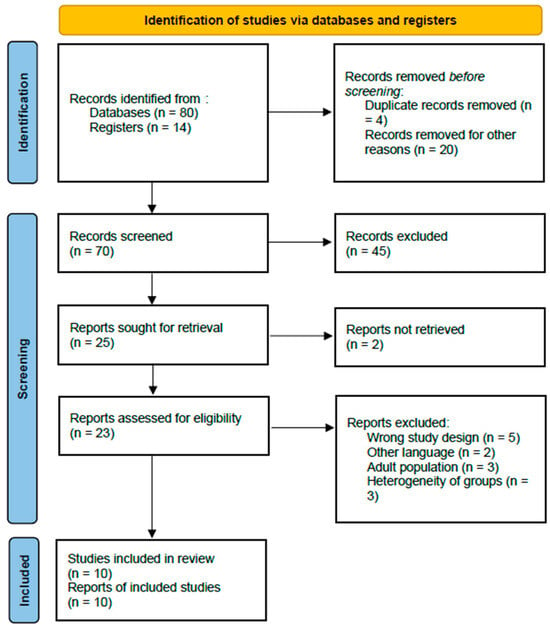

In total, 94 records were identified through the initial database search. After removal of duplicate records (n = 4) and clearly irrelevant studies (n = 20), 70 abstracts were screened. Of these, 47 records were excluded because they consisted of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, narrative reviews, books, or conference abstracts. The remaining 23 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and an additional 13 were excluded for not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 10 studies were deemed eligible and included in the systematic review [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

A detailed PRISMA flow chart illustrating the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of selection of publications for inclusion in the systematic review.

The review included two prospective cohort studies, three retrospective comparative studies, one prospective randomized clinical trial (RCT), one prospective randomized controlled study, one randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study, one retrospective cross-sectional study, and one retrospective cohort study.

Overall, 9493 male patients undergoing hypospadias surgery were included in the selected studies. The median age at the time of surgery was 12.57 months (range 6–168). The distribution of patients according to hypospadias severity, surgical technique, type and duration of postoperative urinary diversion, and antibiotic regimen is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of study features and patient demographics.

3.2. Methods Quality Assessment

Overall, the methodological quality of the included studies ranged from moderate to good. Most studies demonstrated adequate selection of study groups, clearly defined cohorts of pediatric patients undergoing hypospadias repair, and well-described antibiotic strategies. Comparability between groups was acceptable in most studies; however, adjustment for potential confounders—such as hypospadias severity, operative technique, and type or duration of urinary diversion—was inconsistently reported, particularly in retrospective studies. Outcome assessment was generally well defined, with most studies reporting clinically relevant postoperative endpoints, including infectious complications, UCF, wound dehiscence, and meatal or urethral stenosis. Follow-up duration was sufficient to capture early and intermediate postoperative complications in most series, although long-term outcomes were not uniformly addressed. Randomized and prospective studies achieved higher NOS scores than retrospective studies, primarily due to better comparability and more standardized outcome assessment. A detailed overview of the NOS scoring for each included study is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation of study quality according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

3.3. Antibiotic Strategies

Antibiotic strategies varied widely across the included studies with respect to timing, type, and duration of administration (Table 1). When used, preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis mostly consisted of a single intravenous dose administered at anesthesia induction, typically first- or second-generation cephalosporins (e.g., cefazolin or cefonicid), or clindamycin in patients with penicillin allergy. In several studies, preoperative prophylaxis was uniformly administered to all patients undergoing hypospadias repair, regardless of hypospadias severity or surgical technique.

Postoperative antibiotic therapy was equally heterogeneous. The most frequently prescribed agents included trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), trimethoprim (TMP) alone, cephalexin, amoxicillin or amoxicillin–clavulanate, nitrofurantoin, and, less commonly, fluoroquinolones or clindamycin. Postoperative antibiotics were generally administered orally and were often continued for the entire duration of urethral stenting or catheterization, with reported durations ranging from 1 postoperative day to 10 days or until stent removal.

Several studies [15,16,17,20,21,22] compared combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic regimens with either preoperative prophylaxis alone or postoperative therapy alone. In contrast, other studies [18,19,20,22,23,24] specifically evaluated postoperative antibiotic therapy versus no antibiotic use, particularly in distal or midshaft hypospadias repairs.

3.4. Postoperative Outcomes

Infectious complications were reported in 162/9493 (1.7%) patients and included bacteriuria (60/9493, 0.6%), complicated UTI (86/9493, 0.9%), WI and/or SSI (12/9493, 0.1%), cellulitis or infected inclusion cyst (4/9493, 0.04%). Urethroplasty specific complications were reported in 316/9493 (3.3%) patients, including UCF (78/9493, 0.8%), wound dehiscence (209/9493, 2.2%) and meatal or urethral stenosis (29/9493, 0.3%). Other postoperative complications occurred in 14/9493 (0.1%) subjects. The category of “other postoperative complications” was heterogeneous and inconsistently defined across studies. Reported events included urethral diverticulum, meatal regression, and adverse drug reaction (ADR), each occurring at very low frequencies. These outcomes were not uniformly reported and were often grouped differently across studies, limiting direct comparability.

When perioperative antibiotic use was compared with no antibiotic use, no significant differences were observed for infectious complications (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.63–1.44; p = 0.81), UCF (OR 1.89, 95% CI 0.87–4.12; p = 0.10), wound dehiscence (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.98–2.35; p = 0.06), or meatal/urethral stenosis (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.34–2.34; p = 0.82). A statistically significant reduction was observed only for other postoperative complications (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.11–1.00; p = 0.04).

Compared with preoperative antibiotics alone, combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy did not reduce infectious complications (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.71–1.89; p = 0.57) and was associated with higher risks of UCF (OR 7.08, 95% CI 4.16–12.07; p < 0.05), meatal/urethral stenosis (OR 6.05, 95% CI 2.45–14.92; p < 0.05), and other complications (OR 26.78, 95% CI 2.99–239.81; p < 0.05), while wound dehiscence was significantly reduced (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.17–0.66; p = 0.001).

When combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics were compared with postoperative antibiotics alone, a significant reduction in UCF (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.23–0.82; p = 0.008) and other complications (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.06–1.02; p = 0.04) was observed, whereas no significant differences were found for infectious complications, wound dehiscence, or meatal/urethral stenosis. Although statistical significance was observed for “other postoperative complications” in selected analyses, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The very low number of events, heterogeneity in outcome definitions, and marginal CIs substantially limit the robustness and clinical relevance of this result. Accordingly, this outcome should be considered exploratory rather than indicative of a meaningful protective effect of perioperative antibiotic therapy.

All postoperative outcomes reported in each study are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Surgical outcomes between perioperative antibiotics vs. no antibiotics.

Across the included studies, substantial clinical heterogeneity was observed with respect to hypospadias severity (distal, midshaft, or proximal), surgical techniques, duration and type of urinary diversion, and antibiotic regimens in terms of agent, timing, and duration.

This non-random allocation of antibiotic strategies introduces a significant risk of confounding by indication, which likely influenced some of the observed associations. In particular, the paradoxical findings showing higher rates of UCF and meatal/urethral stenosis in patients receiving combined antibiotic therapy should be interpreted considering the clinical context and do not imply a causal adverse effect of antibiotics. Rather, combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic regimens were more frequently administered to patients undergoing more complex hypospadias repairs or considered at higher baseline risk of complications, including proximal hypospadias, redo surgery, longer urethral reconstruction, or prolonged urinary diversion.

Although some subgroup comparisons showed statistically significant differences, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Several of these analyses were based on a limited number of studies, low event rates, and wide CIs, which may reduce their clinical reliability. Comparisons involving combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy versus other regimens are susceptible to selection bias and confounding by indication, as more intensive antibiotic strategies were often preferentially adopted in patients perceived to be at higher surgical risk. Therefore, these subgroup results should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than definitive evidence of a causal effect.

3.5. Meta-Analyses

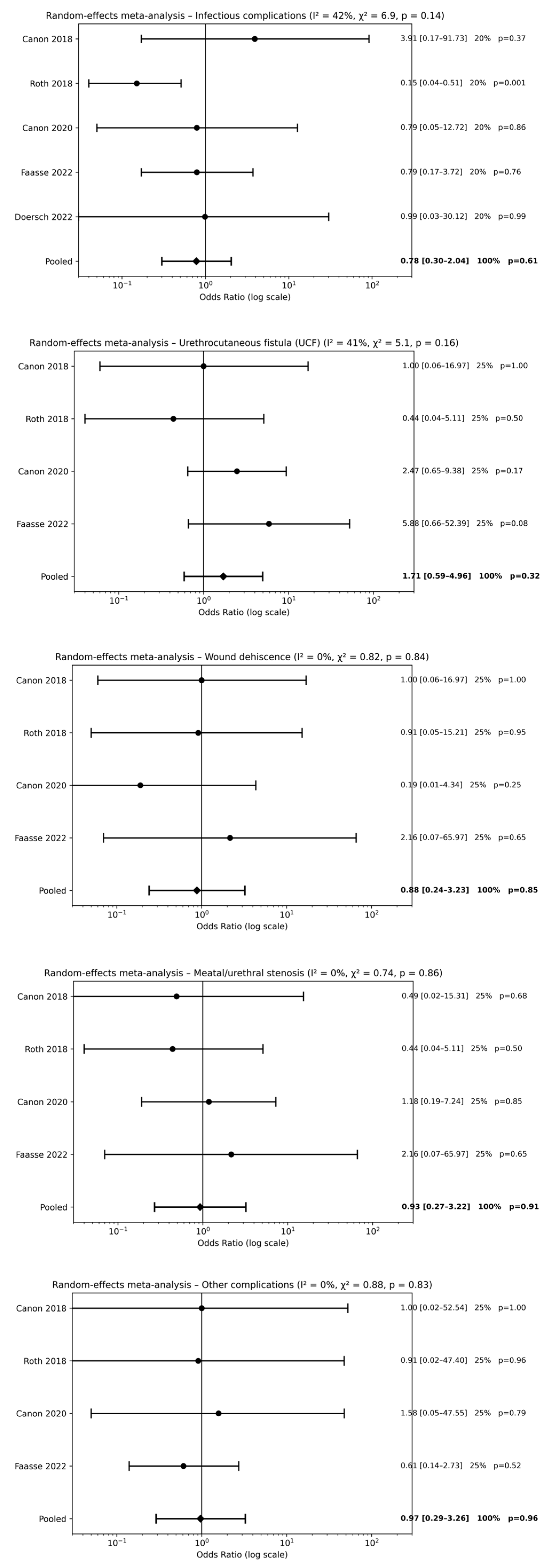

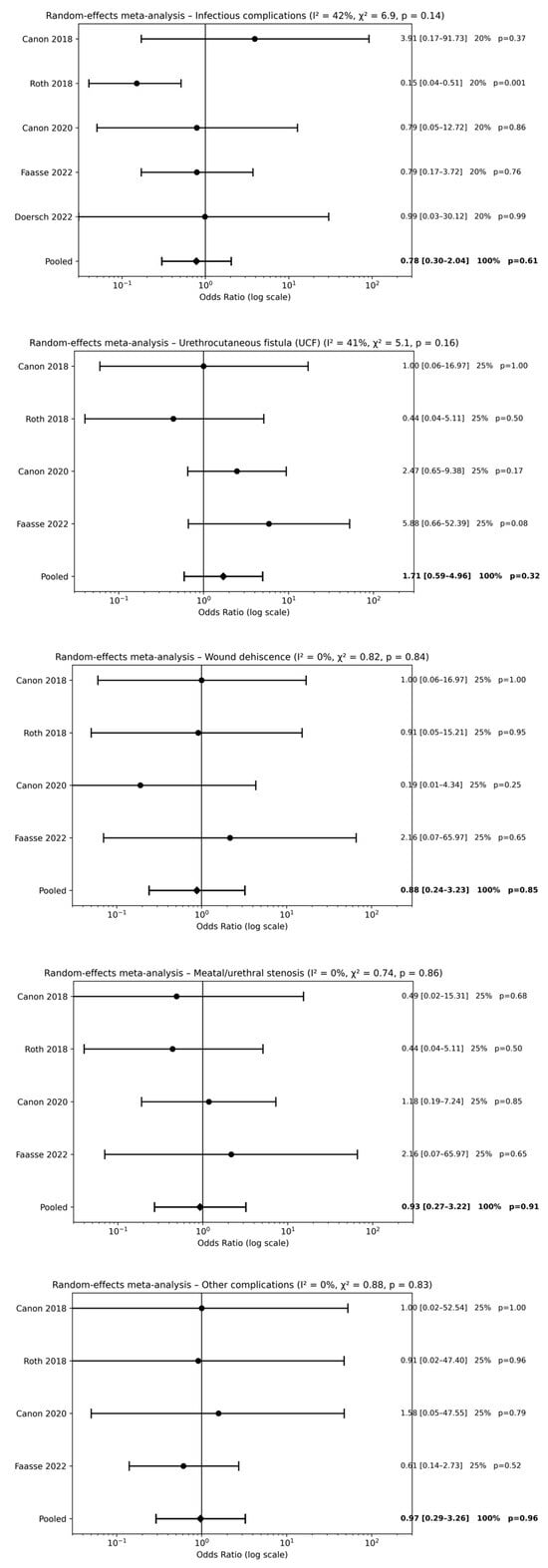

3.5.1. Postoperative Antibiotics Alone vs. No Antibiotics

Five studies [18,19,20,22,23] evaluated postoperative antibiotic therapy alone compared with no antibiotic use following hypospadias repair. Meta-analysis did not demonstrate a significant reduction in postoperative complications associated with postoperative antibiotic use. No statistically significant differences were observed for infectious complications [pooled OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.30–2.04; p = 0.61], UCF [pooled OR 1.71, 95% CI 0.59–4.96; p = 0.32], wound dehiscence [pooled OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.24–3.23; p = 0.85], meatal/urethral stenosis [pooled OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.27–3.22; p = 0.91], or other postoperative complications [pooled OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.29–3.26; p = 0.96] (Figure 2). Overall, effect estimates were consistently close to unity across all outcomes, indicating that postoperative antibiotic therapy alone does not provide a clinically meaningful benefit.

Figure 2.

Forest plots comparison between postoperative antibiotics alone vs. no antibiotics on surgical outcomes [18,19,20,22,23].

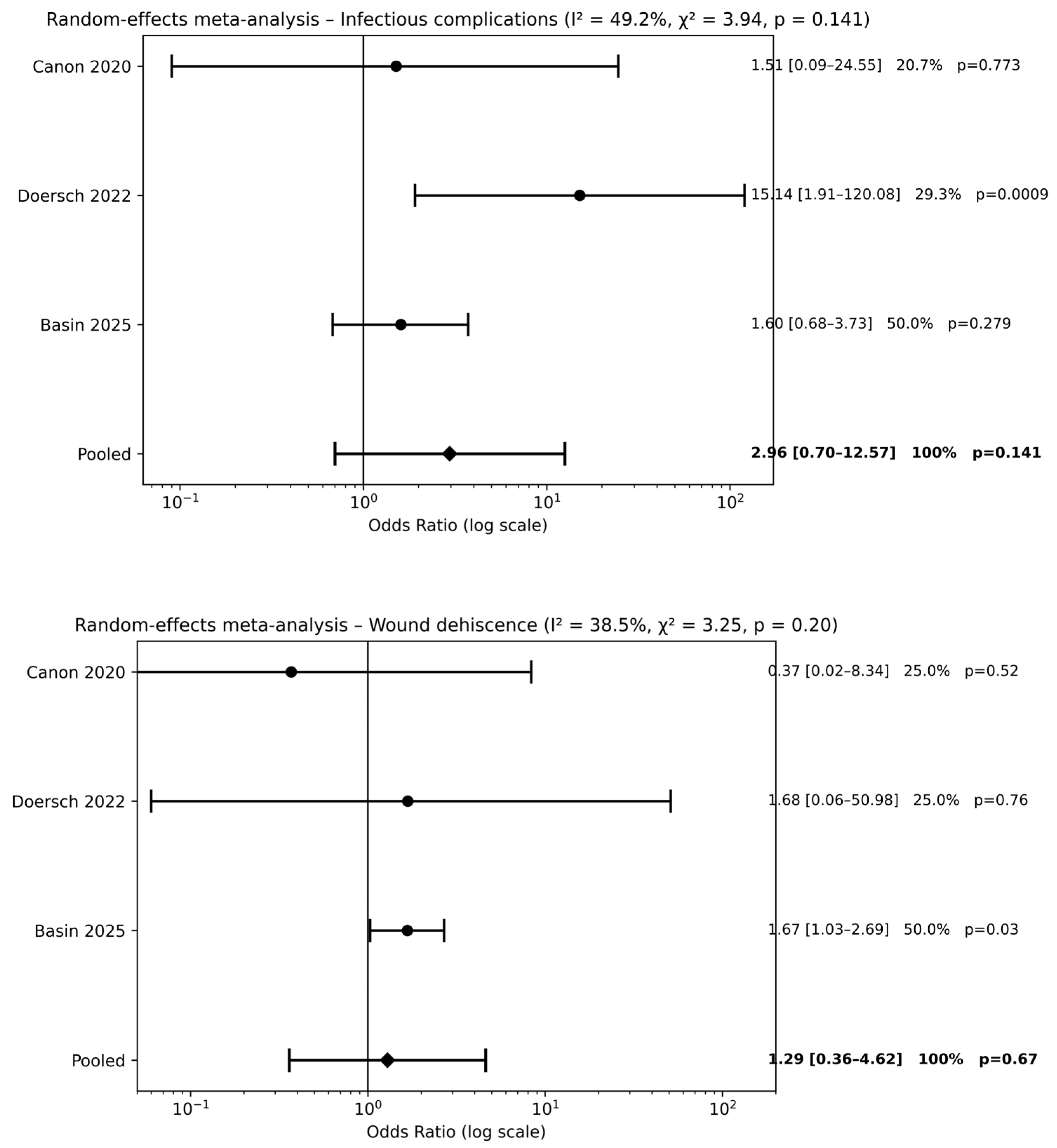

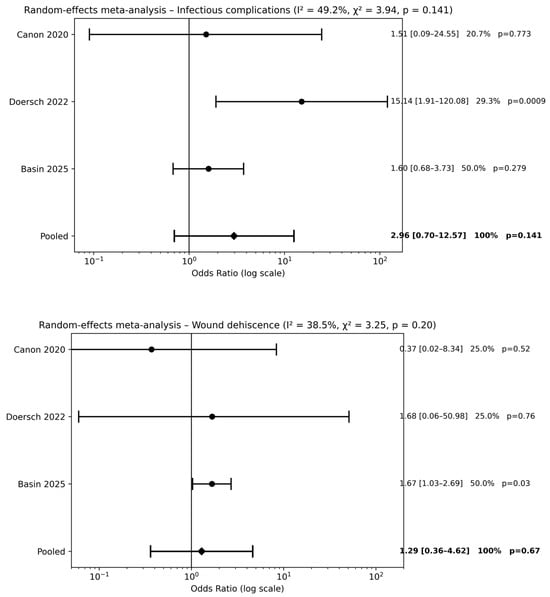

3.5.2. Preoperative Antibiotics Alone vs. No Antibiotics

Three studies [20,22,24] evaluated preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis alone compared with no antibiotic use. Meta-analysis did not demonstrate a significant reduction in postoperative complications for infectious complications [pooled OR 2.96, 95% CI 0.70–12.57; p = 0.14] or wound dehiscence [pooled OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.36–4.62; p = 0.67] (Figure 3). Across outcomes, pooled effect estimates were close to unity, and CIs consistently crossed the line of no effect, indicating the absence of a measurable protective effect of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis alone compared with no antibiotics.

Figure 3.

Forest plots comparison between preoperative antibiotics alone vs. no antibiotics on surgical outcomes (references [20,22,24]).

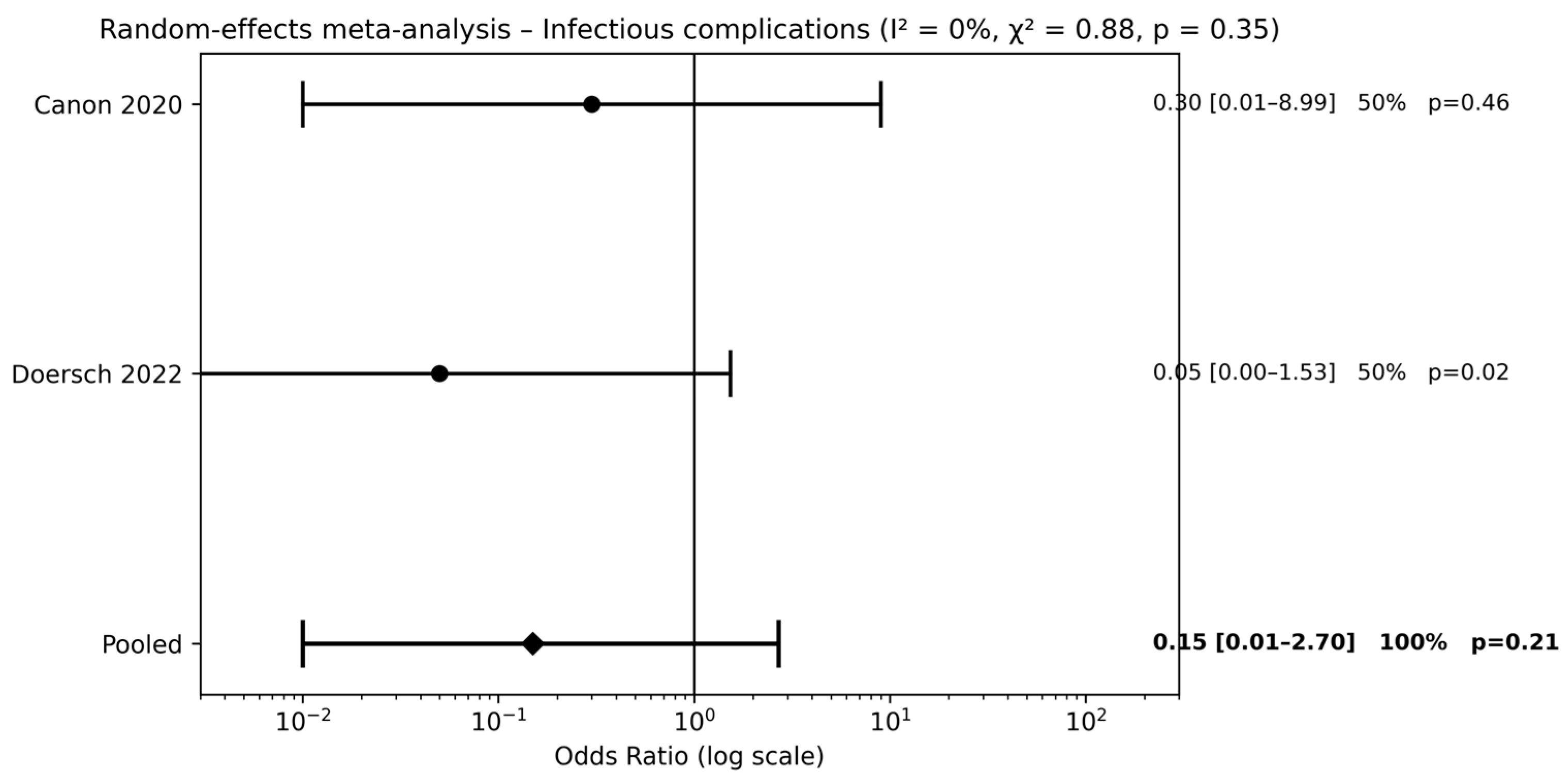

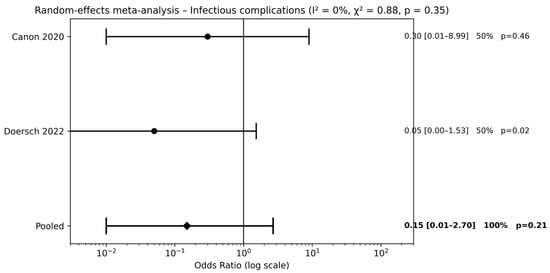

3.5.3. Combined Pre- and Postoperative Antibiotics vs. No Antibiotics

Two studies [20,22] compared combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy with no antibiotic use. Meta-analysis did not demonstrate a significant reduction in infectious complications (pooled OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.01–2.70; p = 0.21) (Figure 4). The wide CIs indicate substantial uncertainty around the estimated effect size.

Figure 4.

Forest plots comparison between combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics vs. no antibiotics on surgical outcomes (references [20,22]).

3.6. Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed for outcomes with at least three comparative studies available. Visual inspection of funnel plots did not reveal significant asymmetry for any postoperative outcome when comparing postoperative antibiotics alone with no antibiotics (Supplementary Figure S1). Egger’s regression test did not demonstrate evidence of small-study effects for infectious complications (p = 0.12), UCF (p = 0.60), wound dehiscence (p = 0.67), meatal/urethral stenosis (p = 0.98), or other postoperative complications (p = 0.27).

For the comparison between preoperative antibiotics alone and no antibiotics, funnel plot inspection did not suggest relevant asymmetry for infectious complications or wound dehiscence (Supplementary Figure S2). Egger’s regression test was not significant for infectious complications (p = 0.98) or wound dehiscence (p = 0.23).

In the comparison between combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics and no antibiotics, formal assessment of publication bias was limited by the small number of studies included. Funnel plot inspection for infectious complications did not show obvious asymmetry (Supplementary Figure S3); however, Egger’s regression test was not applicable due to the inclusion of fewer than three studies. Overall, although no clear evidence of publication bias was identified, the limited number of studies for some outcomes warrants cautious interpretation of these findings.

No formal assessment of certainty of evidence was conducted for individual outcomes. The overall confidence in the findings was therefore based on the consistency of pooled estimates, width of CIs, risk of bias, and the degree of clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies.

4. Discussion

The rationale for antibiotic use in hypospadias surgery has traditionally been extrapolated from general principles of SSI prevention and from adult urology practice [25,26,27,28]. However, hypospadias surgery presents several unique characteristics, including a pediatric patient population, delicate tissue planes, frequent use of urethral stents or catheters, and potential wound contamination with urine or stool in non-continent patients. Importantly, many of the most relevant postoperative complications following hypospadias repair—such as UCF and meatal stenosis—are multifactorial in origin and may be more closely related to surgical technique, tissue ischemia, and wound healing than to infection alone [5,6,7,29,30,31,32,33]. Consequently, the true clinical benefit of perioperative antibiotic therapy in this setting remains uncertain.

Over the past two decades, several studies have explored the relationship between perioperative antibiotic use and postoperative outcomes after hypospadias repair. Nevertheless, the available literature is characterized by marked heterogeneity in study design, patient populations, hypospadias severity, surgical techniques, antibiotic regimens, and outcome definitions [12,13,14]. As a result, published findings are inconsistent and sometimes conflicting, with some studies suggesting a reduction in selected complications, while others report no significant benefit or even potential adverse associations [34,35,36]. This substantial variability in antibiotic protocols underscores the lack of standardized perioperative antibiotic guidelines in hypospadias surgery and highlights the need for evidence-based recommendations. At the same time, increasing concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic-related adverse effects emphasize the importance of avoiding unnecessary antibiotic exposure, particularly in pediatric patients [36,37,38,39,40,41].

In this context, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to clarify the role of perioperative antibiotic therapy in hypospadias repair by addressing three clinically relevant questions: whether perioperative antibiotics reduce postoperative complications compared with no antibiotics; whether combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy provides additional benefit over preoperative antibiotics alone; and whether combined therapy offers advantages over postoperative antibiotics alone.

The most clinically relevant finding of this review is that perioperative antibiotic use does not result in a significant reduction in the most common postoperative complications following hypospadias repair. Across pooled analyses, no significant differences were observed for infectious complications, UCF, wound dehiscence, or meatal/urethral stenosis when perioperative antibiotics were compared with no antibiotic use. The only statistically significant finding was a reduction in other postoperative complications, an infrequently reported and heterogeneous outcome, which substantially limits its clinical interpretability.

These findings challenge the widespread assumption that routine antibiotic administration is necessary to prevent complications after hypospadias repair. Importantly, the overall incidence of infectious complications across the included studies was low (1.7%), suggesting that hypospadias surgery—particularly distal and midshaft repairs—may not carry a sufficiently high infection risk to justify routine antibiotic use. From a pathophysiological perspective, many key complications following hypospadias repair are not primarily driven by infection. UCF, meatal stenosis, and wound dehiscence are influenced by tissue quality, surgical technique, local ischemia, suture tension, and urinary diversion, rather than bacterial contamination alone [42,43,44,45]. Therefore, the lack of a protective effect of antibiotics observed in this meta-analysis appears biologically plausible. When focusing specifically on preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, the meta-analysis demonstrated no significant benefit over no antibiotic use for infectious complications or wound dehiscence. Although preoperative antibiotics are often extrapolated from general surgical prophylaxis principles, their utility in hypospadias surgery remains questionable. Moreover, pooled estimates for preoperative prophylaxis were characterized by wide CIs, reflecting limited sample sizes and heterogeneity among studies. This uncertainty further supports the notion that routine preoperative prophylaxis may not be universally required, particularly in uncomplicated distal repairs performed under standardized sterile conditions.

Similarly, the comparison between combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic therapy and no antibiotics failed to demonstrate a significant reduction in infectious complications. The limited number of available studies and wide CIs precluded definitive conclusions. Interestingly, when combined therapy was compared with preoperative or postoperative antibiotics alone, conflicting results emerged. Combined therapy was associated with a reduction in wound dehiscence in one comparison and with lower UCF rates in another, but also with higher risks of selected adverse outcomes, including fistula and stenosis, when compared with preoperative antibiotics alone.

The findings of this meta-analysis are consistent with previous systematic reviews focusing on postoperative antibiotics in distal hypospadias repair, which similarly reported no clear benefit of prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis [12,13,14]. However, the present study expands upon prior work by including a broader range of antibiotic strategies, surgical techniques, and hypospadias degrees, as well as by evaluating preoperative and combined regimens. Taken together, the available evidence suggests that routine perioperative antibiotic therapy should not be considered mandatory for all patients undergoing hypospadias repair. Instead, a selective and individualized approach appears justified, reserving antibiotic use for patients with specific risk factors such as proximal hypospadias, redo surgery, prolonged urinary diversion, or documented preoperative infection. This strategy may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure, minimize ADR, and contribute to antimicrobial stewardship efforts.

Interpretation of these findings must account for the substantial clinical heterogeneity among the included studies. Hypospadias severity, surgical technique, use and duration of urinary diversion, and antibiotic protocols varied widely, reflecting real-world practice but also introducing important sources of bias. Although a random-effects model was appropriately applied, residual confounding cannot be fully excluded, particularly given the predominance of retrospective study designs. Statistically significant findings emerging from selected subgroup analyses should therefore not be overinterpreted. In the setting of limited sample sizes, low event rates, and wide CIs, such findings may be clinically misleading if considered in isolation. The observed associations, particularly those involving combined antibiotic regimens, are strongly influenced by confounding by indication and underlying case complexity. Confounding by indication is particularly relevant in this context. In several studies, combined pre- and postoperative antibiotic regimens were preferentially administered to patients with more complex clinical profiles, including proximal hypospadias, longer urethral reconstructions, redo surgery, or prolonged catheterization. These patients inherently carry a higher baseline risk of UCF, stenosis, and other complications. Consequently, the observed higher rates of UCF and meatal/urethral stenosis in patients receiving combined antibiotic therapy should not be interpreted as evidence of a causal adverse effect of antibiotics. Rather, these associations reflect underlying case complexity and surgical risk.

Caution is also warranted when interpreting the findings related to “other postoperative complications,” which represented a heterogeneous composite outcome with inconsistent definitions across studies. Although statistical significance was observed in some analyses, this result was driven by very low event rates, wide and marginal CIs, and outcomes of limited clinical relevance. These factors substantially weaken the reliability of this finding and preclude any meaningful inference regarding the effectiveness of perioperative antibiotic therapy based on this outcome alone.

The predominance of distal and midshaft hypospadias repairs in the included studies likely contributed to the very low overall incidence of infectious complications observed in this meta-analysis. This low baseline risk reduces the likelihood of detecting a measurable protective effect of antibiotics and limits the generalizability of the findings to proximal or redo hypospadias repairs, where operative complexity and baseline complication risk are substantially higher. In these higher-risk subgroups, a selective antibiotic strategy may be appropriate and warrants further investigation in future prospective studies.

Systemic perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis represents only one component of a broader infection prevention strategy in hypospadias surgery. Emerging evidence suggests that additional antimicrobial measures may also contribute to reducing infectious complications after hypospadias repair. A recent large 10-year single-center cohort study including 550 pediatric patients reported a significantly lower incidence of SSIs and postoperative UCF when triclosan-coated polydioxanone sutures were used compared with uncoated sutures [46]. Triclosan-coated materials have been shown to inhibit bacterial colonization and biofilm formation at the surgical site, providing a localized antimicrobial effect that may complement systemic antibiotic prophylaxis [47,48,49,50,51]. Although these findings are encouraging, the available evidence is largely observational and derives from single-center experiences. Well-designed prospective multicenter studies are therefore needed to clarify the role of such adjunctive strategies and to determine whether their routine use should be recommended in hypospadias surgery.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the included studies were heterogeneous in terms of design, patient populations, hypospadias severity, surgical techniques, antibiotic regimens, and outcome definitions, which may have influenced pooled estimates. Second, many studies were retrospective and lacked adequate adjustment for confounding variables, increasing the risk of selection bias and confounding by indication. Third, the number of studies available for certain comparisons—particularly combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics versus no antibiotics—was small, limiting statistical power and precluding robust assessment of publication bias. Fourth, most studies focused on short- to intermediate-term outcomes, and long-term complications were not consistently reported. Finally, antibiotic-related adverse effects and microbiological outcomes were inconsistently documented, preventing a comprehensive assessment of the risk–benefit balance of antibiotic use.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that routine perioperative antibiotic therapy does not significantly reduce postoperative complications following hypospadias repair. No clear benefit was observed for preoperative antibiotics, postoperative antibiotics, or combined regimens when compared with no antibiotic use across the most clinically relevant outcomes. These findings support a more selective and individualized approach to antibiotic administration in hypospadias surgery rather than routine use. Antibiotic therapy should be considered on a case-by-case basis, considering patient- and procedure-specific risk factors such as hypospadias severity, redo surgery, prolonged urinary diversion, or the presence of preoperative infection. Well-designed prospective randomized studies with standardized surgical and antibiotic protocols are needed to establish robust evidence-based guidelines for perioperative antibiotic management in pediatric hypospadias repair and to identify patient subgroups that may benefit from targeted antibiotic strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children13020194/s1, Figure S1: Funnel plots assessing publication bias for postoperative antibiotics alone versus no antibiotics, stratified by postoperative outcomes: (A) infectious complications, (B) urethrocutaneous fistula, (C) wound dehiscence, (D) meatal/urethral stenosis, and (E) other complications.; Figure S2: Funnel plots assessing publication bias for preoperative antibiotics alone versus no antibiotics, stratified by postoperative outcomes: (A) infectious complications and (B) wound dehiscence.; Figure S3: Funnel plot assessing publication bias for combined pre- and postoperative antibiotics versus no antibiotics, stratified by only (A) infectious complications.; Table S1: Full electronic search strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E. and M.S.C.; Methodology, M.E., M.C., M.S.C. and C.E.; Software, M.P., G.E. and V.M.; Validation, M.E., M.A. and M.C.; Formal analysis, M.E. and M.S.C.; Investigation, V.M. and M.S.C.; Resources, M.P., G.E. and M.A.; Data curation, V.M., M.S.C. and G.E.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.E.; Writing—review and editing, M.E., M.C. and C.E.; Visualization, M.E. and M.P.; Supervision, M.C. and C.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data extracted from the included studies and used for all analyses in this systematic review are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No analytic code was generated, as all analyses were performed using standard meta-analytic procedures implemented in Review Manager (RevMan) software (Version 5.4).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Giovanni Esposito was employed by the company CEINGE Advanced Biotechnologies. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADR | Adverse drug reaction |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| IRB | Institute Review Board |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SSI | Surgical site infection |

| TMP | Trimethoprim |

| TMP-SMX | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| UCF | Urethrocutaneous fistula |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| WI | Wound infection |

References

- Wood, D.; Wilcox, D. Hypospadias: Lessons learned. An overview of incidence, epidemiology, surgery, research, complications, and outcomes. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2023, 35, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Kojima, Y. Current concepts in hypospadias surgery. Int. J. Urol. 2008, 15, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaseh, S.A.; Halaseh, S.; Ashour, M. Hypospadias: A Comprehensive Review Including Its Embryology, Etiology and Surgical Techniques. Cureus 2022, 14, e27544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, W.A.; Jelani, U.; Fazeel, H.; Khan, S.; Junaid, M.; Islam, N.U.; Ishaq, M.; Khan, W. Complications of Tubularized Incised Plate Urethroplasty and Spongioplasty Repair in Hypospadias. Cureus 2025, 17, e94834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Wang, L.; Peng, Z.; Mao, Y.; Zhao, P.; Wang, C.; Zhou, G.; Luo, Z.; Tan, H. Analysis of risk factors for postoperative complications in hypospadias and construction and validation of a nomogram predictive model. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0339188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escolino, M.; Di Mento, C.; Carraturo, F.; Chiodi, A.; Del Conte, F.; Esposito, G.; Coppola, V.; Caracò, M.S.; Cesaro, B.; Pirone, M.L.; et al. Anatomical and intraoperative predictors of surgical complications after distal hypospadias repair with foreskin reconstruction: A prospective study. World J. Urol. 2025, 44, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguier-Lipszyc, E.; Beberashvili, I.; Shumaker, A.; Stav, K.; Neheman, A. Appraisal of Clinical and Anthropometric Variables as Risk Factors for Urethroplasty Complication in Primary Hypospadias. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2025, 61, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Escolino, M.; Caracò, M.S.; Mazzone, V.; Di Mento, C.; Carraturo, F.; Perricone, F.; Esposito, G.; Porcaro, M.; Esposito, C. The Impact of Postoperative Urinary Diversion on Surgical Outcomes of Hypospadias Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Pediatric Literature. Medicina 2025, 61, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scougall, K.; Bryce, J.; Baronio, F.; Boal, R.L.; Castera, J.R.; Castro, S.; Cheetham, T.; Costa, E.C.; Darendeliler, F.; Davies, J.H.; et al. Predictors of surgical complications in boys with hypospadias: Data from an international registry. World J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 6, e000599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escolino, M.; Florio, L.; Esposito, G.; Esposito, C. The Role of Postoperative Dressing in Hypospadias Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Pediatric Literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 33, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Carretero, S.; Grande Moreillo, C.; Vicente Sánchez, N.; Margarit Mallol, J. Postoperative care in hypospadias. Common practices and evidence available. Cir. Pediatr. 2024, 37, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, E.M.; Patel, H.V.; Koch, G.E.; Sterling, J. Antibiotic Prophylaxis After Urethroplasty: A Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek, Ł.; Rydzińska, M.; Vetterlein, M.W.; Dobruch, J.; Skrzypczyk, M.A. Trauma and Reconstructive Urology Working Party of the European Association of Urology Young Academic Urologists. A Systematic Review on Postoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis after Pediatric and Adult Male Urethral Reconstruction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, M.E.; Kim, J.K.; Rivera, K.C.; Ming, J.M.; Flores, F.; Farhat, W.A. The use of postoperative prophylactic antibiotics in stented distal hypospadias repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2019, 15, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, D.B.; Livne, P.M. Is prophylactic antimicrobial treatment necessary after hypospadias repair? J. Urol. 2004, 171, 2621–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaroglou, N.; Wehbi, E.; Alotay, A.; Bagli, D.J.; Koyle, M.A.; Lorenzo, A.J.; Farhat, W.A. Is there a role for prophylactic antibiotics after stented hypospadias repair? J. Urol. 2013, 190, 1535–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiai, S.; Nordenskjöld, A.; Fossum, M. Advantages of Reduced Prophylaxis after Tubularized Incised Plate Repair of Hypospadias. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, E.B.; Kryger, J.V.; Durkee, C.T.; Lingongo, M.A.; Swedler, R.M.; Groth, T.W. Antibiotic Prophylaxis with Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole versus No Treatment after Mid-to-Distal Hypospadias Repair: A Prospective, Randomized Study. Adv. Urol. 2018, 2018, 7031906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Canon, S.; Marquette, M.K.; Crane, A.; Patel, A.; Zamilpa, I.; Bai, S. Prophylactic Antibiotics After Stented, Distal Hypospadias Repair: Randomized Pilot Study. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2018, 5, 2333794X18770074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canon, S.J.; Smith, J.C.; Sullivan, E.; Patel, A.; Zamilpa, I. Comparative analysis of perioperative prophylactic antibiotics in prevention of surgical site infections in stented, distal hypospadias repair. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2021, 17, 256.e1–256.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchanda, V.; Sengar, M.; Kumar, P. To Compare Short-term Surgical Outcome among Patients given Continuous Postoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis and those given no Postoperative Antibiotics after Urethroplasty for Hypospadias: A Pilot Study. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 28, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doersch, K.M.; Logvinenko, T.; Nelson, C.P.; Yetistirici, O.; Venna, A.M.; Masoom, S.N.; Diamond, D.A. Is parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis associated with fewer infectious complications in stented, distal hypospadias repair? J. Pediatr. Urol. 2022, 18, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faasse, M.A.; Farhat, W.A.; Rosoklija, I.; Shannon, R.; Odeh, R.I.; Yoshiba, G.M.; Zu’bi, F.; Balmert, L.C.; Liu, D.B.; Alyami, F.A.; et al. Randomized trial of prophylactic antibiotics vs. placebo after midshaft-to-distal hypospadias repair: The PROPHY Study. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2022, 18, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basin, M.F.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Ackerman, N.; Mason, M.D.; Tracey, A.J.; Souid, A.; Villanueva, J.A. Utility of Preoperative Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Hypospadias Repair: Results from National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Pediatric Registry. J. Urol. 2025, 214, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lightner, D.J.; Wymer, K.; Sanchez, J.; Kavoussi, L. Best practice statement on urologic procedures and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J. Urol. 2020, 203, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabe, M. Antibiotic prophylaxis in urological surgery, a European viewpoint. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.S., Jr.; Bennett, C.J.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Hollenbeck, B.K.; Pearle, M.S.; Schaeffer, A.J.; Urologic Surgery Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Best Practice Policy Panel. Best practice policy statement on urologic surgery antimicrobial prophylaxis. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Wildenfels, P.; Gonzales, E.T., Jr. Surgical antibiotic practices among pediatric urologists in the United States. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2011, 7, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, G.; Bracka, A.; Palminteri, E.; Marrocco, G. Hypospadias surgery: When, what and by whom? BJU Int. 2004, 94, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, P.L.; Lucaccioni, L.; Poluzzi, F.; Bianchini, A.; Biondini, D.; Iughetti, L.; Predieri, B. Hypospadias: Clinical approach, surgical technique and long-term outcome. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.; Haghpanah, A.; Dehghani, A.; Haghpanah, S.; Ghahartars, M.; Rahmanian, M. Comparison of post-urethroplasty complication rates in pediatric cases with hypospadias using Vicryl or polydioxanone sutures. Asian J. Urol. 2022, 9, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, N.; Tiwari, C.; Mohanty, D.; Baruah, T.D.; Mohanty, M.; Sinha, C.K. Post-urethroplasty complications in hypospadias repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing polydioxanone and polyglactin sutures. World J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 7, e000659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Ali Alaraby, S.O.; Abdeljaleel, I.A.; Hamza, A.A.; Elawad Elhassan, A.E. A comparative study of polydioxanone (PDS) and polyglactin (Vicryl) in hypospadias repair. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2021, 18, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Huang, C.H.; Chou, Y.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Wu, W.J. Outcome of hypospadias reoperation based on preoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2005, 21, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillargeon, E.; Duan, K.; Brzezinski, A.; Jednak, R.; El-Sherbiny, M. The role of preoperative prophylactic antibiotics in hypospadias repair. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014, 8, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Matsuda, A.; Nishino, T.; Uehara, K.; Hagiwara, N.; Sakurazawa, N.; Kawano, Y.; Matsushita, A.; Shimizu, T.; Minamimura, K.; et al. Impact of extended prophylactic antibiotic administration on surgical site infections: A multicenter real-world data study. Surg. Today 2025, 55, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, O.O.; Andriescu, M.; Moga, A.; Caragata, R.; Balanescu, L.; Balanescu, R. Antibiotic Resistance Trends in Recurrent Paediatric Urinary Tract Infections: A Five-Year Single-Centre Experience. Children 2025, 12, 1567. [Google Scholar]

- El Zein, Z.; Boutros, C.F.; El Masri, M.; El Tawil, E.; Sraj, M.; Salameh, Y.; Ghadban, S.; Salameh, R.; El Baasiri, S.; Haddara, A.; et al. The challenge of multidrug resistance in hospitalized pediatric patients with urinary tract infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1570405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Jian, Z.; Wang, M.; Yuan, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Jin, X.; Li, H.; He, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis generally safe and effective in surgical and nonsurgical scenarios? Evidence from an umbrella review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beland, L.E.; Reifsnyder, J.E.; Palmer, L.S. The diversity of hypospadias management in North America: A survey of pediatric urologists. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 2775–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, E.; Mohan, C.; Michael, J.; Ross, S. Inclusion of surgical antibiotic regimens in pediatric urology publications: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2020, 16, 595.e1–595.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.; El-Ghoneimi, A.; Pierucci, U.M.; Lachkar, A.A.; Bidault-Jourdainne, V.; Paye, A.; Peycelon, M. Urethrocutaneous fistula recurrence after hypospadias repair: Risk factors and recurrence rates in a 20-year single-center experience. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2025, 21, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Toorn, F.; Schroeder, R.; de Gier, R.; Quaedackers, J.; Callewaert, P.; Steffens, M.; van der Horst, E.; Schotman, M.; Roobol, M.; Beckers, G.; et al. Prognostic surgical factors related to short term urethroplasty complications after Tubularized Incised urethral Plate Urethroplasty in distal- and mid-type hypospadias in the Dutch Hypospadias Study. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2025, 21, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Yang, B.; Tang, Y.; Mao, Y. Analysis of factors associated with postoperative complications after primary hypospadias repair: A retrospective study. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2022, 11, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T. PREDICT-H Protocol: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study on Preoperative Anatomical Determinants and Postoperative Complications in Primary Hypospadias Repair. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorelić, Z.; Stričević, L.; Elezović Baloević, S.; Todorić, J.; Budimir, D. Safety and Effectiveness of Triclosan-Coated Polydioxanone (PDS Plus) versus Uncoated Polydioxanone (PDS II) Sutures for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection after Hypospadias Repair in Children: A 10-Year Single Center Experience with 550 Hypospadias. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, M.K.; Knebel, P.; Kieser, M.; Schüler, P.; Schiergens, T.S.; Atanassov, V.; Neudecker, J.; Stein, E.; Thielemann, H.; Kunz, R.; et al. Effectiveness of triclosan-coated PDS Plus versus uncoated PDS II sutures for prevention of surgical site infection after abdominal wall closure: The randomised controlled PROUD trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T. Antibiotic sutures against surgical site infections. Lancet 2014, 384, 1424–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, M.; Van Egmond, S.; Petersen, S.M.; Muysoms, F.; Henriksen, N.; Deerenberg, E. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing surgical site infection in abdominal surgery between triclosan-coated and uncoated sutures. Hernia 2024, 28, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Huang, G.; Mao, W.; Li, A. The role of triclosan-coated suture in preventing surgical infection: A meta-analysis. Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 2023, 34, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puca, V.; Traini, T.; Guarnieri, S.; Carradori, S.; Sisto, F.; Macchione, N.; Muraro, R.; Mincione, G.; Grande, R. The Antibiofilm Effect of a Medical Device Containing TIAB on Microorganisms Associated with Surgical Site Infection. Molecules 2019, 24, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.