ICalled-DIY Device for Hands-On and Low-Cost Adapted Emergency Call Learning: A Simulation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Knowledge Analysis

3.2. Demographic Variables of the Groups

3.3. Emergency Call Variables in Simulation in Total Sample

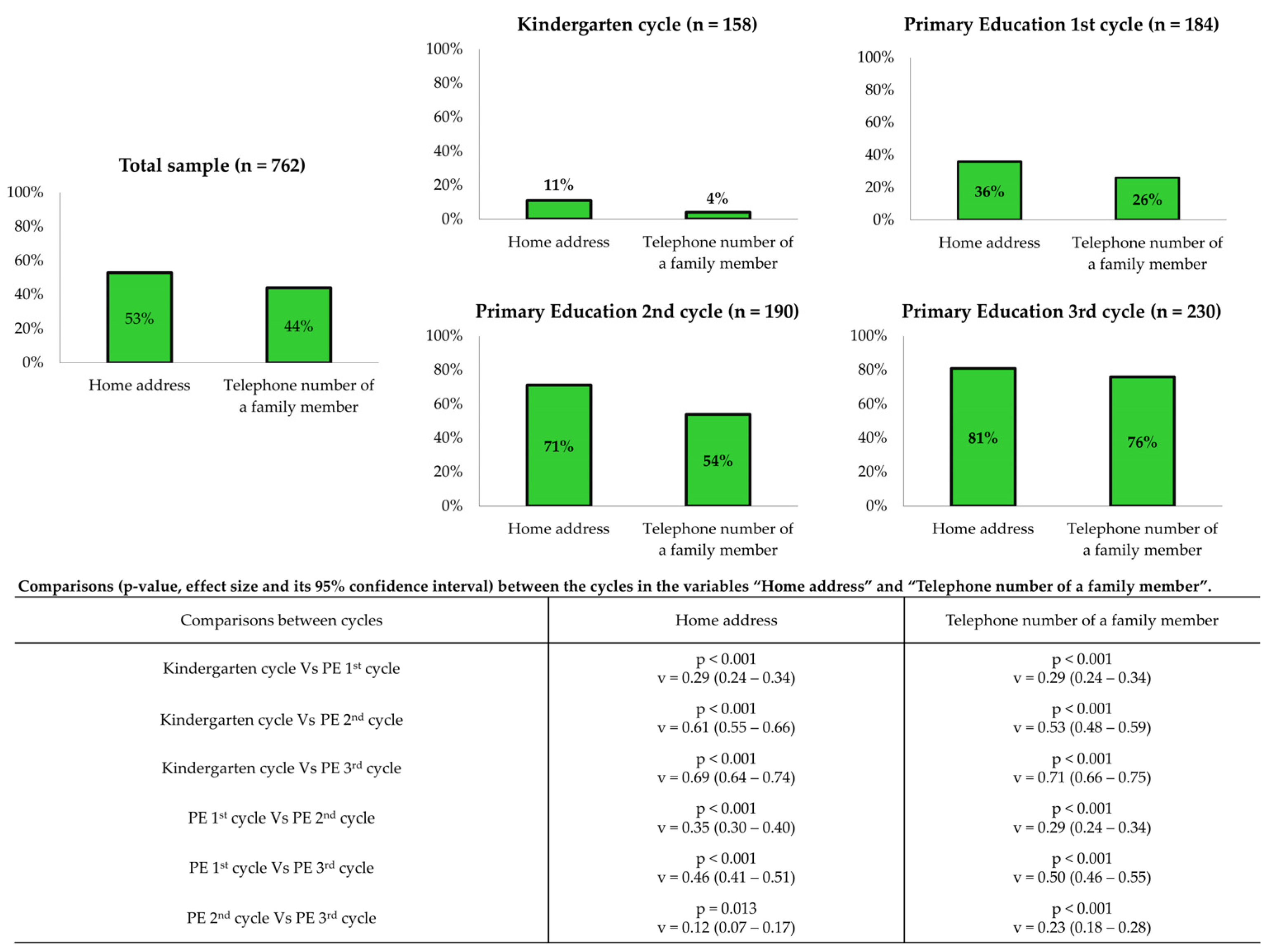

3.4. Emergency Call Variables in Simulation Between Academic Cycles

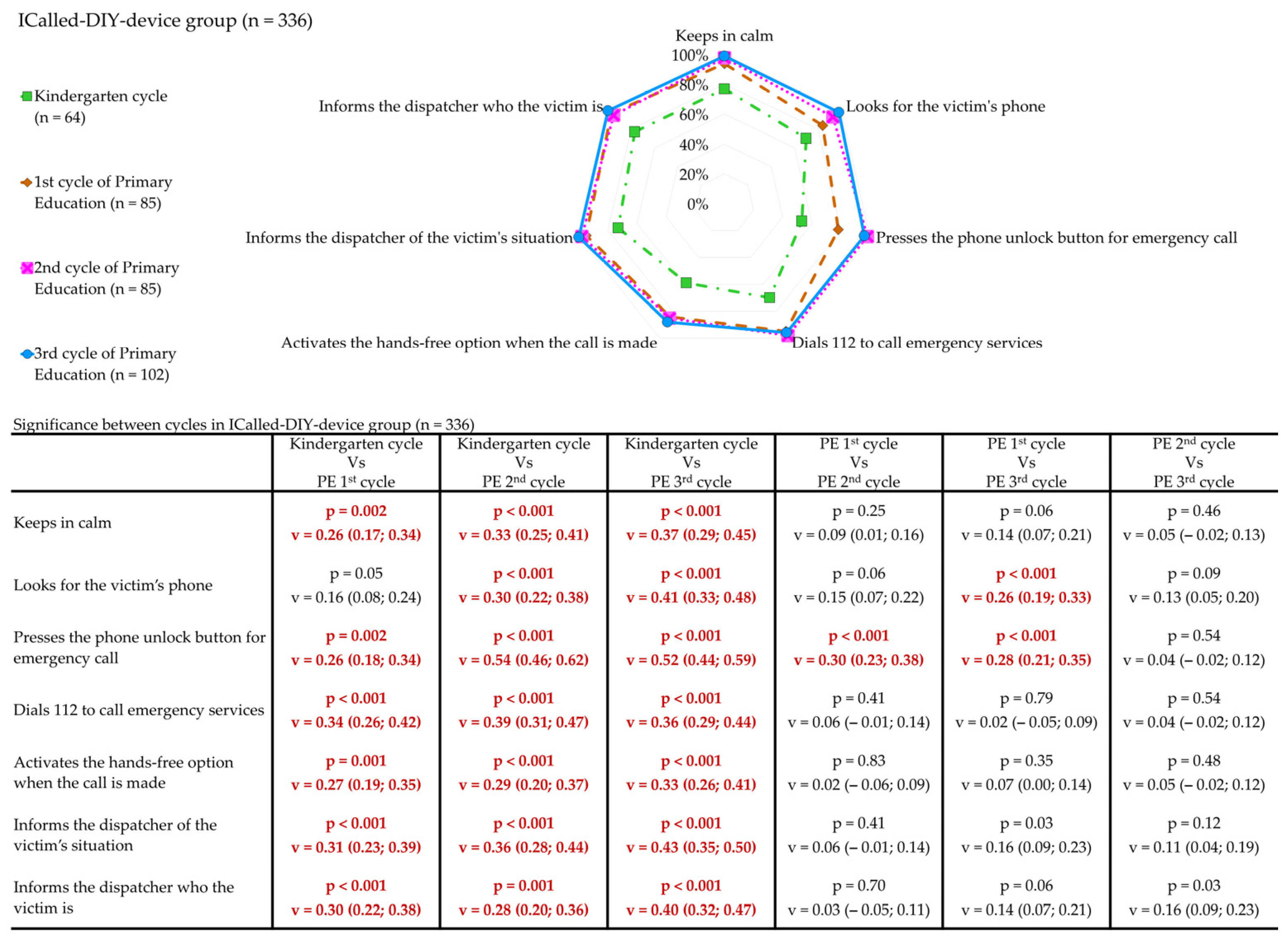

3.5. Emergency Call Variables in Simulacion Between Academic Cycles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OHCA | Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest |

| BLS | Basic Life Support |

| ERC | European Resuscitation Council |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| DIY | Do-it-yourself |

| KG-C | Kindergarten cycle |

| 1st-C | Primary education first cycle |

| 2nd-C | Primary education second cycle |

| 3rd-C | Primary education third cycle |

| C-G | Control group |

| QCPR | Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| ICall-G | ICalled-DIY Device group |

| IBM | International Business Machine Corporation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| NY | New York |

| ES | Effect Size |

| KG | Kindergarten |

Appendix A

| Kindergarten Cycle (n = 158) | ICalled-DIY Device Group (n = 64) | Control Group (n = 94) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Sex | p = 0.10 | |||||

| Male | 31 | (48%) | 58 | (62%) | ||

| Female | 33 | (52%) | 36 | (38%) | ||

| Previous training in BLS | 4 | (6%) | 1 | (1%) | p = 0.07 | |

| Keeps calm | 49 | (77%) | 82 | (87%) | p = 0.08 | |

| Looks for the victim’s phone | 45 | (70%) | 66 | (70%) | p = 0.99 | |

| Presses the phone unlock button for emergency call | 34 | (53%) | 50 | (53%) | p = 0.99 | |

| Dials 112 to call emergency services | 45 | (70%) | 67 | (71%) | p = 0.90 | |

| Activates the hands-free option when the call is made | 38 | (59%) | 35 | (37%) | p = 0.006 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of the victim’s situation | 47 | (73%) | 63 | (67%) | p = 0.39 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of who the victim is | 49 | (77%) | 49 | (52%) | p = 0.002 | |

| Primary Education First Cycle (n = 184) | ICalled-DIY Device Group (n = 85) | Control Group (n = 99) | p Value | |||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Sex | p = 0.86 | |||||

| Male | 50 | (59%) | 57 | (58%) | ||

| Female | 35 | (41%) | 42 | (42%) | ||

| Previous training in BLS | 28 | (33%) | 29 | (29%) | p = 0.59 | |

| Keeps calm | 80 | (94%) | 86 | (87%) | p = 0.10 | |

| Looks for the victim’s phone | 71 | (84%) | 81 | (82%) | p = 0.76 | |

| Presses the phone unlock button for emergency call | 66 | (78%) | 78 | (79%) | p = 0.85 | |

| Dials 112 to call emergency services | 81 | (95%) | 92 | (93%) | p = 0.50 | |

| Activates the hands-free option when the call is made | 71 | (84%) | 52 | (53%) | p < 0.001 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of the victim’s situation | 81 | (95%) | 93 | (94%) | p = 0.69 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of who the victim is | 82 | (97%) | 86 | (87%) | p = 0.021 | |

| Primary Education Second Cycle (n = 190) | ICalled-DIY Device Group (n = 85) | Control Group (n = 105) | p Value | |||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Sex | p = 0.45 | |||||

| Male | 39 | (46%) | 54 | (51%) | ||

| Female | 46 | (54%) | 51 | (49%) | ||

| Previous training in BLS | 33 | (39%) | 28 | (27%) | p = 0.07 | |

| Keeps calm | 83 | (98%) | 102 | (97%) | p = 0.83 | |

| Looks for the victim’s phone | 79 | (93%) | 98 | (93%) | p = 0.92 | |

| Presses the phone unlock button for emergency call | 83 | (98%) | 98 | (93%) | p = 0.16 | |

| Dials 112 to call emergency services | 83 | (98%) | 103 | (98%) | p = 0.83 | |

| Activates the hands-free option when the call is made | 72 | (85%) | 64 | (61%) | p < 0.001 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of the victim’s situation | 83 | (98%) | 105 | (100%) | p = 0.11 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of who the victim is | 81 | (95%) | 101 | (96%) | p = 0.76 | |

| Primary Education Third Cycle (n = 230) | ICalled-DIY Device Group (n = 102) | Control Group (n = 128) | p Value | |||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Sex | p = 0.50 | |||||

| Male | 48 | (47%) | 66 | (52%) | ||

| Female | 54 | (53%) | 62 | (48%) | ||

| Previous training in BLS | 38 | (37%) | 49 | (38%) | p = 0.87 | |

| Keeps calm | 101 | (99%) | 126 | (98%) | p = 0.70 | |

| Looks for the victim’s phone | 100 | (98%) | 114 | (89%) | p = 0.008 | |

| Presses the phone unlock button for emergency call | 98 | (96%) | 127 | (99%) | p = 0.11 | |

| Dials 112 to call emergency services | 98 | (96%) | 126 | (98%) | p = 0.27 | |

| Activates the hands-free option when the call is made | 90 | (88%) | 78 | (61%) | p < 0.001 | |

| Informs the dispatcher of the victim’s situation | 102 | (100%) | 128 | (100%) | - | |

| Informs the dispatcher of who the victim is | 102 | (100%) | 128 | (100%) | - | |

References

- Schroeder, D.C.; Semeraro, F.; Greif, R.; Bray, J.; Morley, P.; Parr, M.; Nakagawa, N.K.; Iwami, T.; Finke, S.-R.; Hansen, C.M.; et al. KIDS SAVE LIVES: Basic Life Support Education for Schoolchildren: A narrative review and scientific Statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation 2023, 147, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greif, R.; Lockey, A.; Breckwoldt, J.; Carmona, F.; Conaghan, P.; Kuzovlev, A.; Pflanzl-Knizacek, L.; Sari, F.; Shammet, S.; Scapigliati, A.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Education for resuscitation. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-Agra, M.; Rodríguez-Núñez, A.; Rey, E.; Abelairas-Gómez, C.; Besada-Saavedra, I.; Antón-Ogando, A.P.; López-García, S.; Martín-Conty, J.L.; Barcala-Furelos, R. What biomechanical factors are more important in compression depth for children lifesavers? A randomized crossover study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 37, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, I.; Whitfield, R.; Colquhoun, M.; Chamberlain, D.; Vetter, N.; Newcombe, R. At what age can schoolchildren provide effective chest compressions? An observational study from the Heartstart UK schools training programme. BMJ 2007, 334, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Buck, E.; Van Remoortel, H.; Dieltjens, T.; Verstraeten, H.; Clarysse, M.; Moens, O.; Vandekerckhove, P. Evidence-based educational pathway for the integration of first aid training in school curricula. Resuscitation 2015, 94, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfai, B.; Pek, E.; Pandur, A.; Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J. ‘The year of first aid’: Effectiveness of a 3-day first aid programme for 7–14-year-old primary school children. Emerg. Med. J. 2017, 34, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bánfai, B.; Pandur, A.; Schiszler, B.; Pék, E.; Radnai, B.; Bánfai-Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J. Little lifesavers: Can we start first aid education in kindergarten? —A longitudinal cohort study. Health Educ. J. 2018, 77, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazas-López, D.; De Pablo-Márquez, B.; Cunillera-Puértolas, O.; Almeda-Ortega, J. Formación RCParvulari: Una metodología de formación en soporte vital básico aplicado al alumnado de 5 años de educación infantil: Efectividad en un ensayo clínico aleatorizado por conglomerados. An. De Pediatría 2022, 98, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, A.; Bánfai-Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J.; Ferkai, L.A.; Deutsch, K.; Musch, J.; Bánfai, B. Teaching cards as low-cost and brief materials for teaching basic life support to 6–10-year-old primary school children—A quasi-experimental combination design study. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Agra, M.; Varela-Casal, C.; Castillo-Pereiro, N.; Casillas-Cabana, M.; Román-Mata, S.S.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Rodríguez-Núñez, A. Podemos enseñar la «cadena de supervivencia» jugando? Validación de la herramienta «Rescube». An. De Pediatría 2020, 94, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto-Pino, L.; Isasi, S.M.; Agra, M.O.; Van Duijn, T.; Rico-Díaz, J.; Núñez, A.R.; Furelos, R.B. Assessing the quality of chest compressions with a DIY low-cost manikin (LoCoMan) versus a standard manikin: A quasi-experimental study in primary education. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 3337–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcala-Furelos, R.; Peixoto-Pino, L.; Zanfaño-Ongil, J.; Martínez-Isasi, S. Challenges in school teaching of first aid: Analysis of educational legislation (lomloe) and curricular orientation. Span. J. Public Health 2025, 98, e202402013. [Google Scholar]

- Olasveengen, T.M.; Semeraro, F.; Ristagno, G.; Castren, M.; Handley, A.; Kuzovlev, A.; Monsieurs, K.G.; Raffay, V.; Smyth, M.; Soar, J.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Basic Life Support. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, J.F.; Davis, S.; Phan, J.; Jegathesan, T.; Campbell, D.M.; Chau, R.; Walsh, C.M. Children’s ability to call 911 in an Emergency: A simulation study. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020010520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Wahl, H.A.; Svendsen, M.V. Primary school children are able to perform basic life-saving first aid measures. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammirati, C.; Gagnayre, R.; Amsallem, C.; Némitz, B.; Gignon, M. Are schoolteachers able to teach first aid to children younger than 6 years? A comparative study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luria, J.W.; Smith, G.A.; Chapman, J.I. An evaluation of a safety education program for kindergarten and elementary school children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Myklebust, A.G.; Østringen, K. Effects of first aid training in the kindergarten–a pilot study. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2011, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, M.; Toner, P.; Connolly, D.; McCluskey, D.R. The ‘ABC for life’ programme-Teaching basic life support in schools. Resuscitation 2006, 72, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, K.; Bixby, E.; Orzel, M.N.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Willett, K. An evaluation of the effectiveness of the Injury Minimization Programme for Schools (IMPS). Inj. Prev. 2000, 6, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Academic Cycle/Year | Total (n = 762) | ICall-G (n = 426) | C-G (n = 336) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten cycle (KG-C) | n = 158 | n = 64 | n = 94 | |

| 3–4 years (4th grade-KG) | n = 33 | n = 12 | n = 21 | |

| 4–5 years (5th grade-KG) | n = 48 | n = 19 | n = 29 | |

| 5–6 years (6th grade-KG) | n = 77 | n = 33 | n = 44 | |

| Primary education first cycle (1st-C) | n = 184 | n = 85 | n = 99 | |

| 6–7 years (1st grade PE) | n = 78 | n = 38 | n = 40 | |

| 7–8 years (2nd grade PE) | n = 106 | n = 47 | n = 59 | |

| Primary education second cycle (2nd-C) | n = 190 | n = 85 | n = 105 | |

| 8–9 years (3rd grade PE) | n = 96 | n = 53 | n = 43 | |

| 9–10 years (4th grade PE) | n = 94 | n = 32 | n = 62 | |

| Primary education third cycle (3rd-C) | n = 230 | n = 102 | n = 128 | |

| 10–11 years (5th grade PE) | n = 96 | n = 41 | n = 55 | |

| 11–12 years (6th grade PE) | n = 134 | n = 61 | n = 73 | |

| Study Phase | Duration (mins) | Content | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Theoretical introduction | 5 | Recognition of an emergency situation, steps to take (checking for consciousness, breathing) and calling emergency services. | Lecture by the nurse, with support from the teacher. Students encouraged to ask questions. |

| 2. Instructor demonstration | 5 | Practical demonstration of emergency recognition and how to call 112. | Nurse models the call using a real phone (C-G) or ICalled-DIY device (ICall-G). Show how to place phone on hands-free option. |

| 3. Student simulation and feedback | 10 | Students practice calling emergency services in pairs, using either a real phone (C-G) or the ICalled-DIY device (ICall-G). | Participants act out a scenario with a real phone and a training manikin (C-G) or with an ICalled-DIY device and their soft toy (ICall-G). In this scenario, they had to (1) unlock the phone screen; (2) dial 112 on the dialling screen; and (3) activate the speaker mode on the call control screen (only possible in the ICall-G). During the scenario, they received immediate instructor feedback with emphasis on (a) clarity in stating the emergency; (b) providing the correct location; (c) following instructions without hanging up. |

| ICalled-DIY Device Group (n = 336) | Control Group (n = 426) | p Value | Effect Size (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | ||||||

| Sex | p = 0.16 | v = 0.05 (0.02; 0.09) | |||||

| Male | 168 | (50%) | 235 | (55%) | |||

| Female | 168 | (50%) | 191 | (45%) | |||

| Previous training in BLS | 103 | (31%) | 107 | (25%) | p = 0.09 | v = 0.06 (0.03; 0.10) | |

| Keeps calm | 313 | (93%) | 396 | (93%) | p = 0.92 | v = 0.04 (0.00; 0.08) | |

| Looks for the victim’s phone | 295 | (88%) | 359 | (84%) | p = 0.17 | v = 0.05 (0.01; 0.09) | |

| Presses the phone unlock button for emergency call | 281 | (84%) | 353 | (83%) | p = 0.78 | v = 0.01 (−0.03; 0.05) | |

| Dials 112 to call emergency services | 307 | (91%) | 388 | (91%) | p = 0.89 | v = 0.01 (−0.03; 0.04) | |

| Activates the hands-free option when the call is made | 271 | (81%) | 229 | (54%) | p < 0.001 | v = 0.28 (0.25; 0.32) | |

| Informs the dispatcher of the victim’s situation | 313 | (93%) | 389 | (91%) | p = 0.35 | v = 0.03 (0.00; 0.07) | |

| Informs the dispatcher of who the victim is | 314 | (94%) | 364 | (85%) | p < 0.001 | v = 0.13 (0.09; 0.16) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Alonso, L.; Vázquez-Álvarez, S.; Martínez-Isasi, S.; Fernández-Méndez, M.; Rey-Fernández, L.; García-Martínez, M.; Seijas-Vijande, A.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Otero-Agra, M. ICalled-DIY Device for Hands-On and Low-Cost Adapted Emergency Call Learning: A Simulation Study. Children 2025, 12, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030282

Castro-Alonso L, Vázquez-Álvarez S, Martínez-Isasi S, Fernández-Méndez M, Rey-Fernández L, García-Martínez M, Seijas-Vijande A, Barcala-Furelos R, Otero-Agra M. ICalled-DIY Device for Hands-On and Low-Cost Adapted Emergency Call Learning: A Simulation Study. Children. 2025; 12(3):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030282

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Alonso, Luis, Sheila Vázquez-Álvarez, Santiago Martínez-Isasi, María Fernández-Méndez, Luz Rey-Fernández, María García-Martínez, Adriana Seijas-Vijande, Roberto Barcala-Furelos, and Martín Otero-Agra. 2025. "ICalled-DIY Device for Hands-On and Low-Cost Adapted Emergency Call Learning: A Simulation Study" Children 12, no. 3: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030282

APA StyleCastro-Alonso, L., Vázquez-Álvarez, S., Martínez-Isasi, S., Fernández-Méndez, M., Rey-Fernández, L., García-Martínez, M., Seijas-Vijande, A., Barcala-Furelos, R., & Otero-Agra, M. (2025). ICalled-DIY Device for Hands-On and Low-Cost Adapted Emergency Call Learning: A Simulation Study. Children, 12(3), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030282