Abstract

Background and Objectives: Childhood obesity and being overweight are influenced by the family environment, diet, sleep, and mental health, with parents playing a key role in shaping behaviors through routines and practices. Healthy parental habits can encourage positive outcomes, while poor routines and stress often lead to unhealthy weight gain. This study analyzed the impact of parental behaviors on children’s lifestyles and habits, as well as the trend and intensity of the effect of these behaviors on different age groups. Methods: A systematic review of 1504 articles from Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and APA PsycNet (as of 22 July 2024) included studies on parents and children aged 4–18 years, focusing on physical activity, sleep, screen time, nutrition, and mental health. Twenty-six studies were analyzed, including 19 cross-sectional and 7 longitudinal studies. The outcomes included physical activity, sedentary behaviors, eating and sleeping habits, mental health, and BMI. Bias was assessed using JBI tools according to the GRADE framework and Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment. Results: The studies involved 89,545 youths and 13,856 parents. The key findings revealed associations between parental physical activity, sleep, dietary habits, mental health, screen time, and their children’s BMIs. Parenting styles significantly influence children’s behaviors. This review highlights the crucial influence of parenting styles and behaviors on children’s physical activity, diet, sleep, and mental health, emphasizing the link between family dynamics and childhood obesity. The findings stress the importance of targeting parental habits in interventions focused on healthy routines and stress management. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine causality, while research involving diverse populations is essential to enhance the applicability of these findings.

1. Introduction

The rising issue of being overweight and obese among youths has become a significant area of research aimed at developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. Addressing the increasing prevalence of these conditions is complex, as it requires more than simply promoting dietary changes and encouraging daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. By the late 20th century, researchers began to examine systemic family dynamics related to childhood and adolescent obesity, emphasizing parenting styles and family interactions [1]. Various factors, including the family environment, lifestyle choices, dietary habits, sleep patterns, and mental health, significantly impact the increasing rates of obese and overweight youths [2,3,4]. Family systems theory posits that families function within complex networks where many interactions co-occur [5]. These interactions are reciprocal, meaning that they mutually influence each other and shape the dynamics within a family. Family dynamics and parental feeding styles are essential in shaping children’s development. Parents play a crucial role by creating the food environment and influencing key aspects of their children’s diet, sleep, and physical activity. This shows a strong correlation between the body mass index (BMI) of parents and that of their children [6,7], with parental dietary habits being particularly influential [6,8]. Research indicates that maternal obesity or being overweight is strongly associated with a higher likelihood of being overweight or obese in childhood, as well as the continuation of excess weight [9]. Specifically, children of overweight or obese parents face a 12% increased risk of becoming obese themselves. Other researchers suggest that the likelihood of a child being overweight or obese increases by 1.62 times when one parent is overweight or obese. If both parents are overweight or obese, then this probability increases three times [10].

Additionally, socioeconomic status (SES), which can be measured through parental education levels, indicates that parents with higher levels of education are more likely to make informed health-related choices. They tend to adopt healthier lifestyles and be positive role models for their children [11]. Parents with lower education levels frequently reside in low-income neighborhoods, which tend to have environments that contribute to obesity [12]. Additionally, family dynamics play a significant role in childhood obesity. Siblings can encourage each other to participate in more physical activities and outdoor play [11]. In contrast, children without siblings may be more inclined to engage in sedentary behaviors, like watching TV [13].

Evidence suggests that the eating behaviors of young people are closely linked to their parents’ dietary practices [8,14,15]. Parental emotional eating is often associated with the emotional malnourishment of their children [14]. Costa and Oliveira [16] concluded that less healthy eating habits are correlated with youth behavioral issues and parental stress. This relationship may influence how parents perceive feeding challenges, impacting the overall quality of their children’s diets. According to family systems theory [5], an authoritative feeding style is expected to promote healthier dietary habits and enhance a child’s ability to self-regulate their eating behaviors. In contrast, an authoritarian feeding style will likely result in more rigid feeding practices and a diminished ability to recognize and respond to hunger and fullness cues [5,11,17]. Therefore, parental feeding styles can significantly affect the dietary quality of youths [11,14,15]. A more permissive feeding style, often stemming from parental stress, anxiety, and depression [18], tends to result in fewer feeding challenges for children and is associated with higher body mass index (BMI) levels.

In addition, controlling and persuasive feeding practices are associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. These practices not only increase the risk of being overweight and obesity but may also promote emotional eating patterns, leading to excessive or insufficient food intake [11,18,19,20]. Specifically, sleeping for less than 7 h increases the risk of being overweight and obesity [20]. Kanellopoulou and Notara [19] further reinforced this idea by highlighting a negative association between average sleep duration and the likelihood of being overweight or obese.

Healthy lifestyles among parents can help reduce childhood obesity. When parents embrace healthier habits, the risk of being overweight for youths is lower [6,21]. In this context, physical activity plays a crucial mediating role, as the level of physical activity parents engage in significantly influences how much physical activity their children undertake [14,22]. There is a positive correlation between parents’ physical activity and their mental health, as well as a similar positive relationship between the physical activity levels of youths and their mental health. Additionally, the quality of family relationships is vital for mental health, as it is closely linked to the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders [23,24]. Additionally, family conflicts are strongly associated with an increase in mental health issues, underscoring the critical impact of family cohesion on psychological well-being [24].

Given these connections, this review aims to consolidate scientific evidence regarding the nature of associations between parents and their children. Specifically, it seeks to explore whether there are notable differences in the intensity and trends of these associations over time. Furthermore, this review analyzes how parental habits and behaviors influence their children’s lives, including lifestyle choices, eating habits, screen time, sleep patterns, mental health, and body mass index (BMI). Finally, an important goal is to assess whether the evidence gathered in recent decades remains consistent and relevant in understanding these dynamics today.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This review was prepared while following the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA ScR) (Supplementary Table S1). The protocol for this review is registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) at the following link: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/NRK7T.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

This review adhered to the population, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) framework [25] to identify the essential concepts of the studies related to the research question in advance and to streamline the search process.

This review included studies published in English, encompassing qualitative, quantitative, longitudinal, and cross-sectional research which did not involve interventions. It specifically examined the relationships between parental characteristics and behaviors—such as lifestyle, sleep habits, physical activity, and mental health—and those of their children. The analysis focused on families with children and adolescents aged 4–18, exploring the association between parental behaviors and children’s lifestyle outcomes. The review considered interventions related to parental eating patterns, physical activity levels, sleep habits, and parenting styles. Comparisons assessed variations in the children’s physical activity, body mass indexes (BMIs), sleep quality and duration, screen time, dietary habits, and mental health. Only peer-reviewed studies with longitudinal designs were included, while non-randomized experimental studies and the gray literature were excluded. The outcomes highlighted the significant impact of family dynamics on children’s well-being.

2.3. Literature Search and Study Selection

A comprehensive review was conducted on 22 July 2024 across four research databases—Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and APA PsycNet—using common keywords and the Boolean operators AND and OR based on the following search equation: [“Adolescent*” OR “Teenager*” OR “teen” OR “family”] AND [“Adiposity” OR “Normal weight” OR “overweight” OR “obesity” OR “BMI”] AND [“lifestyle*” OR “physical activity” OR “sedentary lifestyle” OR “sleep habit*” OR “nutritional habit*” OR “family environment*”] AND [“mental health” OR “anxiety” OR “stress” OR “depress*” OR “well-being” OR “body satisfaction”]. Table 1 outlines the search strategy used for each database. Original research studies on children, adolescents, and families were included. No restriction was placed on the publication year, although the synthesis was limited to studies in English. The articles were imported into EndNote X9.3.3 software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), where the gray literature was excluded, and duplicates were automatically and manually removed.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles written in English; (2) nuclear, co-parenting, and single-parent families; (3) children aged between 4 and 18 years; (4) analysis of the habits and lifestyles of both parents and children; and (5) analysis of the sleep habits, physical activity, and mental health of both parents and children.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) children residing in social institutions; (2) children younger than 4 years or older than 18 years; (3) families with chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes or hypertension); (4) families with psychological or mental illnesses; (5) surgical interventions; and (6) studies implementing exercise training, diet plans, or intervention programs. Interventional studies were excluded because their focus is on evaluating intervention effectiveness, while this review aims to examine natural risk factors and associations without manipulating variables. This approach emphasizes real-world relationships between factors rather than testing interventions.

2.5. Data Extraction

Two authors (C.M. and D.B.) conducted the extraction of original bibliographic articles. The two authors conducted the search and selection independently using the following criteria: the characteristics of the target population, age of the target population, type of study, and outcome. When necessary, a third and fourth author (A.M.R. and H.F.) assisted in including or excluding articles.

2.6. Data Items, Synthesis, and Charting

Once the final selection of articles was performed, data from eligible articles were extracted and organized in a Microsoft Excel file. The data categories included author(s), year of publication, article title, type of study (e.g., cross-sectional, cohort, or longitudinal), objectives and purpose, population characteristics (sample size and average age), BMI, physical activity measures, sleep measures, screen time measures, mental health, family characteristics, nutritional habits, and primary study results. In this process, the articles were grouped according to the variables under study. For this scoping analysis, the findings for each research question were presented based on the articles which provided evidence of a positive, negative, or no association between the habits of young people and their families’ habits.

2.7. Risk of Bias and Study Quality Assessment

The quality of the included cross-sectional and cohort studies was assessed using critical appraisal tools from Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [26], which comply with the recommendations of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, to analyze the quality of primary research and the risk of bias. These tools consist of an 8 item checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies and a 10 item checklist for qualitative studies. Each checklist offers four response options for every question: “yes = 1”, “no = 0”, “unclear = 0”, and “not applicable = not scored”. These responses guide the assessment of the methodological quality of the studies. For the 8 item checklist and 10 item checklist, a percentage of 0–33% indicates low quality, a rate of 34–66% indicates moderate quality, and a rate of 67% or more indicates high quality [27,28].

The quality of the included longitudinal and cohort studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form [29,30]. The scale uses a scoring system based on three main domains: selection, which evaluates how participants were recruited and whether the initial cohort was representative of the target population; comparability, which assesses the study’s ability to control for confounding factors, ensuring that the cohorts were comparable regarding the most relevant variables; and outcome, which examines the quality and consistency in the assessment of outcomes as well as the adequacy of the follow-up period. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [29,30] would be converted to AHRQ quality standards, classifying studies as good, fair, or poor. Good quality requires 3–4 stars for selection, 1–2 for comparability, and 2–3 for outcome or exposure. Fair quality needs 2 stars for selection, 1–2 for comparability, and 2–3 for outcome or exposure. Studies scoring 0–1 in selection, 0 in comparability, or 0–1 in outcome or exposure were rated as poor quality. This ensured standardized study evaluation.

Among all of the above-mentioned tools, the NOS is the most used tool currently, and it can also be modified based on a special subject [31].

3. Results

3.1. Selection and Description of Studies

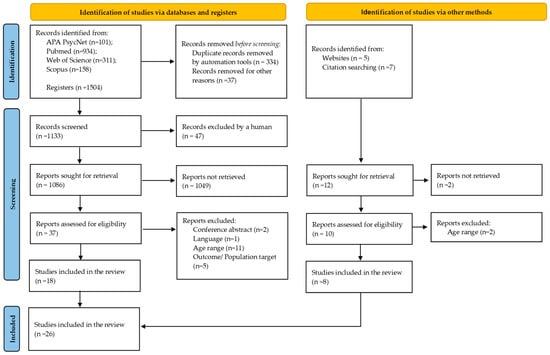

The literature search was conducted across the Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and APA PsycNet databases, producing 1504 articles. An additional seven articles were sourced from other research databases. Following the PRISMA guidelines, the search and selection process was conducted independently by C.M. and D.B. Duplicate articles were removed using EndNote X9.3.3 software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), reducing the total number of articles to 1093. After the titles and abstracts were reviewed, 1049 articles were excluded. Thirty-seven articles were assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 18 met the eligibility criteria. Additionally, eight studies were identified via other methods [32,33,34,35,36,37].

Consequently, 25 studies were included in this review.

Of the 19 excluded articles, 11 included an inappropriate age range, 5 presented decontextualized outcomes, 2 were conference abstracts, and 1 was a Mendelian randomization study [38]. Nineteen of the included studies were cross-sectional, and six were longitudinal, with participants aged between 4 and 18 years. One of the included cross-sectional studies was a qualitative study [39]. The publication years ranged from 2004 to 2024. Among the included articles, only 2008, 2010, 2014, 2018, and 2019 had a single article each. No articles from 2016 or 2021 were included. Two articles from 2004, 2015, 2022, and 2024, three from 2017, five from 2023, and five from 2020 were analyzed. Figure 1 shows the selection process of the included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies.

Among the 25 articles, 13 assessed physical activity and sedentary behavior [6,33,35,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], 4 evaluated sleep habits and quality [32,34,48,49], and 5 measured screen time [32,40,41,43,50]. Mental health was examined in 13 articles [37,42,43,44,45,46,47,51,52,53,54,55,56], whereas the family environment was analyzed in all articles except one [6]. Fifteen studies addressed dietary habits [6,14,35,37,41,43,44,46,47,50,51,52,53,54,56].

The BMI was calculated through weight measurement using calibrated electronic scales and self-reported data, and height measurements were obtained using a stadiometer and self-reported data. Physical activity and sedentary behavior data were collected using self-reporting questionnaires [6,35,36,37,39,40,41,43,44,45,46,47] and accelerometers [33,42]. Sleep habits and quality of sleep, screen time, mental health, family environment and characteristics, and nutritional and eating habits were measured using questionnaires.

The Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) critical appraisal tools [26] were applied, and the results showed moderate-to-high quality, ranging from 62.5% to 87.5%. Regarding the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form (NOS) [29,30], two articles were of “fair” quality, and five were of “good” quality [46,47,50,51]. The results of Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) critical appraisal tools and the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form (NOS) are in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Quality analysis of cross-sectional studies.

Table 3.

Quality analysis of qualitative research.

Table 4.

Quality analysis of longitudinal and cohort studies.

3.2. Main Findings

Table 5 demonstrates an association between parental lifestyles and the unhealthy behaviors adopted by their children. Socioeconomic factors are linked to obesity, with evidence indicating that low-income families are more likely to have obese children [36,43,51,55,56]. Youth mental health is closely related to obesity. Research has shown that the risk of obesity is four times higher among youths who exhibit anxiety traits [51] and depressive symptoms [47,53,55]. Additionally, parental mental health significantly impacts their children’s well-being, habits, and weight [44,45,47,52,53]. Studies have indicated that better mental health in mothers and fathers is associated with a lower likelihood of their children being overweight or obese [43,45,47,56].

Table 5.

Results.

Stress is a critical factor in mental health. When parental stress levels are high, they can negatively affect children’s physical activity and overall well-being [42,45], despite parents recognizing the importance of physical activity in family life [39]. Only a small percentage of youths are aware of and meet the recommended daily physical activity levels [35], with boys being more likely to meet these guidelines [35,40]. However, boys also exhibit lower levels of physical activity and more television viewing, particularly among those who are overweight compared with their healthy-weight peers [54]. Parental habits, behaviors, and lifestyles can influence those of their children [46,47]. Therefore, increased physical activity among mothers and fathers and participation in family physical activities can help foster active and consistent exercise habits in youths [33,35,36,39,40,41,42,45,47,50]. This, in turn, can address sedentary behaviors, especially excessive screen time, which heightens the risk of obesity [33,41,42]. Such sedentary behaviors can increase junk food consumption and contribute to unhealthy lifestyles [41]. Improving the quality of the family meal environment may also enhance overall physical fitness and reduce daily soft drink consumption [46]. Furthermore, dietary and sleep habits are crucial factors related to obesity. Families with unstable and unhealthy dietary patterns [14,37,41,44,52] tend to negatively affect their children’s well-being and sleeping habits [32,34,48,49], which can subsequently impact mental health and increase the risk of being overweight or obese.

4. Discussion

This review synthesized findings from 22 studies examining the relationships between lifestyle factors, sleep patterns, dietary habits, mental health, and parenting styles in parents and youths of ages 4–18. The total sample included 59,360 youths and 13,428 parents.

Only two studies [37,48] received a moderate quality rating; therefore, their results did not significantly impact the overall findings. However, these studies were less robust and had a higher risk of bias. Their inclusion and analysis were carried out carefully, considering factors such as weighting of evidence, subgroup analysis, and overall confidence in evidence to acknowledge their potential impact on the results.

The analysis revealed significant correlations between the lifestyles, habits, and behaviors of parents and their children, notably affecting their overall well-being and body mass index (BMI) scores. Key aspects of the family environment, such as socioeconomic status (SES), dietary practices, and parenting styles, emerged as crucial factors influencing the development of unhealthy behaviors. These factors include eating habits, sleep patterns, screen time, and physical activity.

4.1. Family Environment, Characteristics, and BMI

Socioeconomic status significantly influences the BMIs of youths [35,46,47,50,51]. However, research has shown that various family-related factors contribute to youth BMIs [57,58,59]. Additionally, the family climate and environment can impact academic performance and general success or failure in school [57].

For example, permissive parenting styles or indulgent parenting styles, whether from the mother or father [58,60], are commonly linked to higher BMI values. This happens because permissive or indulgent parenting allows youths the freedom to adopt unhealthy behaviors, particularly regarding their eating habits. These parenting approaches may lead to the easier acceptance of processed and convenient food options to avoid conflicts or difficulties around mealtimes [59,60].

Similarly, a lack of parental presence or supervision can lead to increased consumption of convenient yet unhealthy foods without parental control, often with little awareness of the benefits or harms of such dietary choices. A dysfunctional family environment may cause psychological changes in youths and contribute to disordered eating behaviors, like loss of control and overeating, stemming from a lack of emotional expression from parents [52,58]. Fostering a supportive family environment can lead to significant improvements despite these challenges. Authoritative parenting, shared meals, open communication, and consistent guidance encourage healthier habits, enhance emotional well-being, and strengthen family bonds, ultimately promoting positive long-term outcomes.

4.2. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior

Recent research on the relationship between parents’ body mass indexes (BMI) and their children’s BMIs indicated that children with overweight or obese parents are significantly more likely to be overweight or obese themselves [6,7,61,62,63,64,65]. There is also a strong correlation between parents’ physical activity levels and those of their children [22,33,35,39,45,47], as parents often serve as role models. Studies have shown that when parents engage in less physical activity or lack awareness of its benefits, their children tend to mirror these behaviors, leading to reduced physical activity and increased BMIs [66,67].

The importance of physical activity for youth well-being is underscored by recent findings reiterating earlier research [35]. However, most young people fail to meet the recommended physical activity guidelines [68,69]. For instance, a study investigating the link between sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption and levels of moderate and vigorous physical activity among youths—especially those who are overweight or obese—found that higher SSB intake, along with inadequate physical activity, increased the risk of being overweight or obese [70,71]. Research has shown a direct link between low physical activity levels and an increased risk of obesity. SES also affects physical activity habits, as communities with higher SESs often provide better resources and infrastructure which promote healthy behaviors. These areas generally have more amenities and facilities encouraging active lifestyles [72,73].

Additionally, regular physical activity delivers numerous health benefits, including lower levels of specific hormones which can affect food intake and contribute to more effective weight management [74]. Employing family-based approaches can promote healthier lifestyles, as parental habits significantly impact children’s body mass indexes (BMIs) and activity levels. Encouraging parents to engage in regular physical activity and adopt healthier dietary choices can create a supportive environment for positive change. Collaborative programs in schools and communities can focus on family-centered routines, reducing the risk of obesity while improving the overall well-being of youths.

4.3. Nutritional Habits and Eating Habits

The findings indicate a significant correlation between parents’ eating habits, children’s nutritional statuses [37], and their eating behaviors. This relationship is influenced by factors such as nutritional literacy and the pressure parents exert on their children to eat, which have been shown to impact youths’ eating behaviors [44]. Research corroborating these findings [18,49,59,75] highlights that certain parenting styles probably contribute to increased consumption of unhealthy foods, which is associated with higher BMIs among youths [59].

Moreover, parents’ perceptions of their children’s weight may be crucial in shaping their feeding practices, significantly influencing their children’s body image and the stigma associated with weight [15]. Recent studies further underscored the connection between parents’ mental health and the dietary quality of their children [18]. These studies revealed that poorer mental health among parents often leads to more controlling and coercive feeding strategies, which can adversely affect youths’ nutritional well-being. Such feeding practices may disrupt youths’ ability to self-regulate their food intake, potentially increasing the risk of obesity in later stages of life [76].

4.4. Mental Health

Parents’ mental health plays a significant role in their children’s well-being, particularly concerning physical activity levels. Research has demonstrated a negative correlation between parental stress and youth’s engagement in physical activities. Conversely, effective family communication has been shown to influence physical activity levels [45].

Recent studies have further emphasized the connection between parents’ mental health and youth’s tendencies toward emotional eating [18,75]. Specifically, youth whose parents experience poorer mental health may exhibit higher levels of emotional eating, indicating a link between the emotional states of parents and their children’s eating behaviors.

Additionally, youths’ perceptions of body weight and experiences of food restriction significantly impact their mental health. Such perceptions can foster body stigma, leading to detrimental changes in dietary habits [15]. Furthermore, a higher body mass index (BMI) has been correlated with mild depressive symptoms as well as slight alterations in anxiety levels and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among youths [38]. Notably, this research suggests that a mother’s BMI may also have a direct influence on her child’s depressive symptoms, underscoring the interconnectedness of familial health dynamics [38]. Another factor which significantly influences mental health is screen time, particularly the time spent on online gaming. While there are some benefits to electronic gaming, such as fostering creativity and improving cognitive functioning [77], the long-term negative impacts on mental health if gaming is overemphasized [68] and on family relationships as a means of escaping real-life situations are evident [78]. Therefore, understanding the dual nature of gaming’s impact on mental health is crucial to promoting healthier engagement practices. Promoting open family communication and mental health support for parents can reduce stress and positively impact children’s behaviors, including physical activity and emotional eating. Encouraging body positivity and family-based healthy habits can further improve mental and physical health outcomes, fostering a supportive environment for overall well-being.

4.5. Screen Time

Screen time remains a frequent topic of discussion among families, considering both benefits and disadvantages. Parents tend to implement strategies and behaviors to reduce screen time more than promote physical activity levels [79], recognizing the adverse effects that screens can have [80,81]. The significant consequences of excessive screen time include impacts on youths’ healthy development [82], overall well-being [83,84], relationships with their parents [80,81,85], and social-emotional growth [86,87,88].

While some studies have highlighted the positive aspects of screens [77], particularly in educational contexts such as reading [89], excessive screen use has detrimental effects on cognitive development, negatively influencing academic performance [89,90]. Language development is notably impacted, especially among younger children, as this limits their interactions with peers, adults, and parents [85,88].

Studies have shown that children aged 8–17 spend an average of 1.5–2 h playing video games daily [91]. In this context, active parental monitoring, including setting rules and limits on screen time [80,81] and engaging in open discussions about game content, is essential for fostering healthy gaming behaviors and mitigating potential risks [92]. A lack of supervision may lead to problematic gaming habits, where adolescents turn to video games to cope with negative emotions such as stress or frustration [92,93].

The visual content consumed can trigger behavioral changes, potentially contributing to ADHD [94]. Furthermore, screen time has been linked to obesity, anxiety, depression [55], and sleep disturbances [87,95]. Socioeconomic status is a variable which influences screen time exposure and duration. Studies have indicated that children from families with high socioeconomic statuses (SESs) spend significantly less time with screens compared with those from middle- and low-SES groups [73].

4.6. Quality and Sleep Habits

The duration and quality of sleep are influenced by several factors, especially screen time [80,95]. Parents’ habits and behaviors also play a key role in determining sleep quality, as they establish routines which impact youths’ overall well-being. One consequence of poor sleep habits is obesity, with research indicating that a 2 h delay in bedtime at the age of 11 predicted a 0.6 cm increase in waist circumference after a 2.5 year follow-up period [96]. Additionally, inconsistent sleep patterns can cause hormonal imbalances which affect appetite and energy levels, increasing the risk of obesity [97,98].

Furthermore, irregular sleep can lead to low energy, poor concentration, and mood swings. In youths aged 4–12 years, the most common sleep issues are falling asleep and staying asleep [99], with anxiety and disrupted routines being the main contributors. The family environment might significantly influence sleep quality [100,101,102,103], particularly the relationship between parents and children [104,105]. Spending time with family can help reduce anxiety and improve one’s well-being, leading to better sleep quality. This relationship depends on family dynamics, especially parental relationships, and factors such as the child’s gender, alcohol consumption, and parental education levels. The likelihood of a youth getting adequate sleep increases with the parents’ level of education [103].

The analysis highlights the positive impact of a supportive family environment on young people’s BMIs, emphasizing the importance of healthy parental behaviors and mental well-being. Socioeconomic status is a factor which also influences family lifestyles and is associated with the prevalence of obesity and being overweight [106], with increases being observed particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts [72]. The environment in which children grow up can significantly impact their dietary choices and levels of physical activity.

Improving parenting styles, promoting physical activity, managing screen time, and ensuring adequate sleep can significantly enhance youths’ well-being and reduce obesity risks. Parental mental health fosters emotional eating habits and encourages physical activity. By prioritizing family support and healthy habits, we can create an environment which promotes positive outcomes for children and adolescents.

4.7. Study Strengths and Limitations

This review has several strengths, like the well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and focusing on specific age groups (4–18 years) and family types while excluding studies with confounding variables, ensuring the review’s relevance. It includes a diverse population, covering various family compositions and parental behaviors and providing a holistic view of the family environment’s impact on children. Including qualitative and quantitative non-interventional studies, it captures a broad spectrum of observational data, offering insights into naturalistic family dynamics. A systematic approach for data extraction, multiple reviewers to minimize bias, and thorough assessments of study quality and risk of bias enhance this review’s robustness.

Overall, this study provides a comprehensive and methodologically sound review of the association between parental behaviors and many child outcomes, highlighting significant associations and potential areas for intervention. However, limitations such as language restrictions, the predominance of cross-sectional studies, limited consideration of cultural factors, and biases should be considered. Including studies with self-reported data may raise concerns about the exact accuracy of some findings; however, these data collection tools are commonly employed in studies investigating multiple variables with large sample sizes. Future research could benefit from a broader range of studies and culturally diverse contexts as well as longitudinal and interventional models to strengthen causal inferences.

5. Conclusions

An active lifestyle is crucial for the well-being of children and adolescents. Excessive screen time and inconsistent sleep routines can harm both physical and mental health, fostering unhealthy habits. Balanced parenting plays a key role in shaping eating behaviors and self-regulation, reducing the risk of obesity and related issues, such as eating disorders.

This review highlights the connection between parental behaviors and children’s BMIs, eating habits, physical activity, and sleep patterns. However, several aspects remain underexplored, such as the long-term effects of parental influence as children grow into adolescence and how cultural, socioeconomic, and environmental factors affect these behaviors. Although the evidence did not definitively show whether the intensity of these associations changes with age, it did emphasize the significant role parental behaviors play in shaping the lifestyles of young people, in line with previous data.

Practical strategies involving both parents and children are essential to fill these gaps. Future interventions should focus on educating parents on managing screen time, promoting physical activity, and fostering healthy eating habits at home. Additionally, offering mental health support to parents can reduce stress and improve family dynamics and children’s behaviors. Schools and community programs should work together to develop family-focused initiatives which reinforce these positive habits, helping to reduce the risk of obesity and improve youth well-being.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children12020203/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Reference [107] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

C.M., H.M.F. and A.M.M.-R. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the manuscript, as well as to the analysis and interpretation of the results and data. All authors participated in drafting the manuscript and revised it critically. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Sport Sciences and Physical Education of the University of Coimbra (Study Registration Reference: CE/FCDEF-UC/00092024, 15 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ventura, A.K.; Birch, L.L. Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.L.; Orton, A.L.; Tindall, S.W.; Christensen, J.T.; Enosakhare, O.; Russell, K.A.; Robins, A.-M.; Larriviere-McCarl, A.; Sandres, J.; Cox, B.; et al. Barriers to Healthy Family Dinners and Preventing Child Obesity: Focus Group Discussions with Parents of 5-to-8-Year-Old Children. Children 2023, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasile, C.M.; Padovani, P.; Rujinski, S.D.; Nicolosu, D.; Toma, C.; Turcu, A.A.; Cioboata, R. The Increase in Childhood Obesity and Its Association with Hypertension during Pandemics. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umekar, S.; Joshi, A. Obesity and Preventive Intervention Among Children: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e54520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, S. Families and Family Therapy; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Webber-Ritchey, K.J.; Habtezgi, D.; Wu, X.; Samek, A. Examining the Association Between Parental Factors and Childhood Obesity. J. Community Health Nurs. 2023, 40, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Ledoux, T.A.; Johnston, C.A.; Ayala, G.X.; O’Connor, D.P. Association of parental body mass index (BMI) with child’s health behaviors and child’s BMI depend on child’s age. BMC Obes. 2019, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Bu, T.; Dong, X. Are parental dietary patterns associated with children’s overweight and obesity in China? BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demment, M.M.; Haas, J.D.; Olson, C.M. Changes in family income status and the development of overweight and obesity from 2 to 15 years: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajian, P.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Risvas, G.; Karasouli, K.; Bountziouka, V.; Voutzourakis, N.; Zampelas, A. Socio-economic and demographic determinants of childhood obesity prevalence in Greece: The GRECO (Greek Childhood Obesity) study. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notara, V.; Sakellari, E. Family-Related Characteristics and Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Obes. 2022, 2022, 6728502. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, B.; Baur, L.A.; Burlutsky, G.; Robaei, D.; Mitchell, P. Socio-economic, familial and perinatal factors associated with obesity in Sydney schoolchildren. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2012, 48, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Gabr, S.A.; Iqbal, Z.A. Television watching, diet and body mass index of school children in Saudi Arabia. Pediatr. Int. 2016, 58, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, C.; Hatton, R.; Li, Q.; Xv, J.; Li, J.; Tian, J.; Yuan, S.; Hou, M. Associations of parental feeding practices with children’s eating behaviors and food preferences: A Chinese cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, J.M.; Vander Weg, M.W. Investigating the relationship between parental weight stigma and feeding practices. Appetite 2020, 149, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Oliveira, A. Parental Feeding Practices and Children’s Eating Behaviours: An Overview of Their Complex Relationship. Healthcare 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.M. A review of familial correlates of child and adolescent obesity: What has the 21st century taught us so far? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2009, 21, 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampige, R.; Kuno, C.B.; Frankel, L.A. Mental health matters: Parent mental health and children’s emotional eating. Appetite 2023, 180, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulou, A.; Notara, V.; Magriplis, E.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Rojas-Gil, A.P.; Kornilaki, E.N.; Lagiou, A.; Yannakoulia, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Sleeping patterns and childhood obesity: An epidemiological study in 1728 children in Greece. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litsfeldt, S.; Ward, T.M.; Hagell, P.; Garmy, P. Association Between Sleep Duration, Obesity, and School Failure Among Adolescents. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020, 36, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Lv, R.; Zhao, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Jia, P.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; et al. Parental adherence to healthy lifestyles in relation to the risk of obesity in offspring: A prospective cohort study in China. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.; Bunting, L.; McCartan, C.; Grant, A.; McBride, O.; Mulholland, C.; Nolan, E.; Schubotz, D.; Cameron, J.; Shevlin, M. Parental physical activity, parental mental health, children’s physical activity, and children’s mental health. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1405783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, A.L.; Appel, H.B.; Lee, J.; Fincham, F. Family Factors Related to Three Major Mental Health Issues Among Asian-Americans Nationwide. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 49, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marth, S.; Cook, N.; Bain, P.; Lindert, J. Family factors contribute to mental health conditions—A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32 (Suppl. S3), ckac129.454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.L.C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Niño de Guzmán, E.; Martínez García, L.; González, A.; Heijmans, M.; Huaringa, J.; Immonen, K.; Ninov, L.; Orrego-Villagrán, C.; Pérez-Bracchiglione, J.; Salas-Gama, K.; et al. The perspectives of patients and their caregivers on self-management interventions for chronic conditions: A protocol for a mixed-methods overview [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Research 2021, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Z.C.; Hussain, R.; Balan, S.; Saini, B.; Muneswarao, J.; Ong, S.C.; Babar, Z.-U.-D. Perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of asthma patients towards the use of short-acting β2-agonists: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.S.B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ma, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, Z.-H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Sasayama, D.; Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, T.; Kuraishi, Y.; Washizuka, S. Association between Children’s Difficulties, Parent-Child Sleep, Parental Control, and Children’s Screen Time: A Cross-Sectional Study in Japan. Pediatr. Rep. 2023, 15, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S.I.; Küpers, L.K.; Kors, L.; Sijtsma, A.; Sauer, P.J.J.; Renders, C.M.; Corpeleijn, E. Parental physical activity is associated with objectively measured physical activity in young children in a sex-specific manner: The GECKO Drenthe cohort. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehri, A.; Taheri, P.; Khazaie, H.; Jalali, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Mohammadi, R. The relationship between parents’ sleep quality and sleep hygiene and preschool children’ sleep habits. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dozier, S.G.H.; Schroeder, K.; Lee, J.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Kubik, M.Y. The Association between Parents and Children Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines. J. Pediatr. Nurs.-Nurs. Care Child. Fam. 2020, 52, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehne, S.; Pollatos, O.; Warschburger, P.; Zimprich, D. The Association Between Longitudinal Changes in Body Mass Index and Longitudinal Changes in Hours of Screen Time, and Hours of Physical Activity in German Children. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2024, 10, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tommasi, M.; Toro, F.; Salvia, A.; Saggino, A. Connections between Children’s Eating Habits, Mental Health, and Parental Stress. J. Obes. 2022, 2022, 6728502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.M.; Sanderson, E.; Morris, T.; Ayorech, Z.; Tesli, M.; Ask, H.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Andreassen, O.A.; Magnus, P.; Helgeland, Ø.; et al. Body mass index and childhood symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A within-family Mendelian randomization study. eLife 2022, 11, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.L.; Jago, R.; Brockman, R.; Cartwright, K.; Page, A.S.; Fox, K.R. Physically active families—De-bunking the myth? A qualitative study of family participation in physical activity. Child. Care Health Dev. 2010, 36, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadogan, S.L.; Keane, E.; Kearney, P.M. The effects of individual, family and environmental factors on physical activity levels in children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, R.; Milani Marin, L.E.; Russo, V.; Zavarrone, E.; Ferrara, E.; Balzaretti, C.; Valerio, A.; Pasanisi, F.; Nisoli, E.; Carruba, M.O. Family lifestyle and childhood obesity in an urban city of Northern Italy. Eat. Weight Disord. 2015, 20, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.P.; Ra, C.; O’Connor, S.G.; Belcher, B.R.; Leventhal, A.; Margolin, G.; Dunton, G.F. Associations Between Maternal Mental Health and Well-being and Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2017, 38, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, B.A.; Weinstein, K.; Mojica, C.M.; Davis, M.M. Parental Mental Health Associated with Child Overweight and Obesity, Examined Within Rural and Urban Settings, Stratified by Income. J. Rural Health 2020, 36, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, K.; Huang, L.; Shi, W.; Tang, C.; Xu, T.; Zhu, S.; Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Individual, family and social-related factors of eating behavior among Chinese children with overweight or obesity from the perspective of family system. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1305770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.A.; Kyoung Lee, T.; Leite, R.O.; Noriega Esquives, B.; Prado, G.; Messiah, S.E.; St George, S.M. The Effects of Parental Stress on Physical Activity Among Overweight and Obese Hispanic Adolescents: Moderating Role of Family Communication and Gender. J. Phys. Act. Health 2019, 16, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbec, M.J.; Pagani, L.S. Associations Between Early Family Meal Environment Quality and Later Well-Being in School-Age Children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2018, 39, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Ding, M.; Strohmaier, S.; Schernhammer, E.; Sun, Q.; Chavarro, J.E.; Tiemeier, H. Maternal adherence to healthy lifestyle and risk of depressive symptoms in the offspring: Mediation by offspring lifestyle. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 6068–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.L.; Chaves, P.; Papoila, A.L.; Loureiro, H.C. The family role in children’s sleep disturbances: Results from a cross-sectional study in a Portuguese Urban pediatric population. Sleep Sci. 2015, 8, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.Y.; Tung, Y.C.; Huang, C.M.; Gordon, C.J.; Machan, E.; Lee, C.C. Sleep disturbance associations between parents and children with overweight and obesity. Res. Nurs. Health 2024, 47, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Story, M.; van den Berg, P. Accurate parental classification of overweight adolescents’ weight status: Does it matter? Pediatrics 2008, 121, e1495–e1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.; Victora, C.; Barros, F. Social, familial, and behavioral risk factors for obesity in adolescents. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2004, 16, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, A.R.; Lacruz, T.; Solano, S.; Blanco, M.; Moreno, A.; Rojo, M.; Beltrán, L.; Graell, M. Identifying Loss of Control Eating within Childhood Obesity: The Importance of Family Environment and Child Psychological Distress. Children 2020, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, T.C.; Liang, H.L.; Plomin, R.; Sham, P.; Sterne, A.; Williamson, R.; Purcell, S. Parental familial vulnerability, family environment, and their interactions as predictors of depressive symptoms in adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, M.; Lindberg, N.; Komulainen, E.; Puukko-Viertomies, L.R.; Aalberg, V.; Marttunen, M. Psychological well-being in adolescents with excess weight. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2015, 69, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benny, C.; Patte, K.A.; Veugelers, P.J.; Senthilselvan, A.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Pabayo, R. A Longitudinal Study of Income Inequality and Mental Health Among Canadian Secondary School Students: Results from the Cannabis, Obesity, Mental Health, Physical Activity, Alcohol, Smoking, and Sedentary Behavior Study (2016–2019). J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Hu, R.; Feng, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, L. The relationship between family diet consumption, family environment, parent anxiety and nutrition status children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1228626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratta, L.; Delvecchio, E.; Capurso, M.; Mazzeschi, C. Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Overweight and Obesity: An Explorative Study Focused on School Functioning and Well-being. Contin. Educ. 2023, 4, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, P.; Delker, E.; Blanco, E.; Burrows, R.; Lozoff, B.; Gahagan, S. Home and Family Environment Related to Development of Obesity: A 21-Year Longitudinal Study. Child. Obes. 2019, 15, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanezi, N.M.; Maximino, P.; Machado, R.H.V.; Ferrari, G.; Fisberg, M. Association between parental feeding styles, body mass index, and consumption of fruits, vegetables and processed foods with mothers’ perceptions of feeding difficulties in children. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, L.A.; O’Connor, T.M.; Chen, T.A.; Nicklas, T.; Power, T.G.; Hughes, S.O. Parents’ perceptions of preschool children’s ability to regulate eating. Feeding style differences. Appetite 2014, 76, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Gupta, B.; Bigoniya, P. Association of childhood obesity with obese parents and other familial factors: A systematic review. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dhana, K.; Zong, G.; Yuan, C.; Schernhammer, E.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, F.B.; Chavarro, J.E.; Field, A.E.; Sun, Q. Lifestyle of women before pregnancy and the risk of offspring obesity during childhood through early adulthood. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gete, D.G.; Waller, M.; Mishra, G.D. Pre-Pregnancy Diet Quality Is Associated with Lowering the Risk of Offspring Obesity and Underweight: Finding from a Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberali, R.; Kupek, E.; Assis, M.A.A. Dietary Patterns and Childhood Obesity Risk: A Systematic Review. Child. Obes. 2020, 16, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Lv, R.; Zhao, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, P.; Li, Z.; Jia, P.; Zhang, H.; et al. Associations between parental adherence to healthy lifestyles and risk of obesity in offspring: A prospective cohort study in China. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11 (Suppl. S1), S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, T.L.; Møller, L.B.; Brønd, J.C.; Jepsen, R.; Grøntved, A. Association between parent and child physical activity: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christofaro, D.G.D.; Tebar, W.R.; Silva, C.C.M.d.; Saraiva, B.T.C.; Santos, A.B.; Antunes, E.P.; Leite, E.G.F.; Leoci, I.C.; Beretta, V.S.; Ferrari, G.; et al. Association of parent-child health parameters and lifestyle habits—The “epi-family health” longitudinal study protocol. Arch. Public Health 2024, 82, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Thornton, J.; et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiang, S.-T.; Dong, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, Z.; Li, L. Association between Physical Activity and Age among Children with Overweight and Obesity: Evidence from the 2016–2017 National Survey of Children’s Health. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 9259742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Huang, F.; Zhang, X.; Xue, H.; Ni, X.; Yang, J.; Zou, Z.; Du, W. Association of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption and Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity with Childhood and Adolescent Overweight/Obesity: Findings from a Surveillance Project in Jiangsu Province of China. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzi, K.; Moschonis, G.; Choupi, E.; Manios, Y. Late night overeating is associated with smaller breakfast, breakfast skipping and obesity in children. The Healthy Growth Study. Nutrition 2016, 33, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z.A.; Hamid, Z.A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; Adams, R.J.; Aekplakorn, W.; Afsana, K.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, B.B.; Li, L.; Cui, Y.F.; Shi, W.X. Effects of outdoor activity time, screen time, and family socioeconomic status on physical health of preschool children. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1434936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Miguel, P.; Tapia Serrano, M.; García-Hermoso, A. Skipping breakfast and excess weight among young people: The moderator role of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 3195–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarro, S.; Lahdenperä, M.; Vahtera, J.; Pentti, J.; Lagström, H. Parental feeding practices and child eating behavior in different socioeconomic neighborhoods and their association with childhood weight. The STEPS study. Health Place 2022, 74, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haycraft, E. Mental health symptoms are related to mothers’ use of controlling and responsive child feeding practices: A replication and extension study. Appetite 2020, 147, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.A.; King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. Family factors in adolescent problematic Internet gaming: A systematic review. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.M.; Uchida, P.M.; Aguiar, F.O.; Kadri, G.; Santos, R.I.M.; Barbosa, S.P. Escaping through virtual gaming—What is the association with emotional, social, and mental health? A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1257685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, J.W.; Berry, T.R.; Carson, V.; Rhodes, R.E.; Lithopoulos, A.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Examining differences in parents’ perceptions of children’s physical activity versus screen time guidelines and behaviours. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2021, 57, 1448–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arundell, L.; Gould, L.; Ridgers, N.D.; Ayala, A.M.C.; Downing, K.L.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Veitch, J. “Everything kind of revolves around technology”: A qualitative exploration of families’ screen use experiences, and intervention suggestions. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, K.; Scholten, H.; Granic, I.; Lougheed, J.; Hollenstein, T. Insights about Screen-Use Conflict from Discussions between Mothers and Pre-Adolescents: A Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Darlington, G.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J. Mothers’ and fathers’ media parenting practices associated with young children’s screen-time: A cross-sectional study. BMC Obes. 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myruski, S.; Gulyayeva, O.; Birk, S.; Pérez-Edgar, K.; Buss, K.A.; Dennis-Tiwary, T.A. Digital disruption? Maternal mobile device use is related to infant social-emotional functioning. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21, e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Radesky, J.S. Technoference: Parent Distraction with Technology and Associations with Child Behavior Problems. Child. Dev. 2018, 89, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustonen, R.; Torppa, R.; Stolt, S. Screen Time of Preschool-Aged Children and Their Mothers, and Children’s Language Development. Children 2022, 9, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez, D.; Delfino, G.; Vargas-Salfate, S.; Liu, J.H.; Gil De Zúñiga, H.; Khan, S.; Garaigordobil, M. A longitudinal study of the effects of internet use on subjective well-being. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 676–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, T.K.; Rumbold, A.R.; Kedzior, S.G.E.; Moore, V.M. Psychological impacts of “screen time” and “green time” for children and adolescents: A systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinot, P.; Bernard, J.Y.; Peyre, H.; De Agostini, M.; Forhan, A.; Charles, M.-A.; Plancoulaine, S.; Heude, B. Exposure to screens and children’s language development in the EDEN mother–child cohort. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Riesch, S.; Tien, J.; Lipman, T.; Pinto-Martin, J.; O’Sullivan, A. Screen Media Overuse and Associated Physical, Cognitive, and Emotional/Behavioral Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: An Integrative Review. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2022, 36, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suggate, S.P.; Martzog, P. Children’s sensorimotor development in relation to screen-media usage: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 74, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanko, D. The Health Effects of Video Games in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Rev. 2023, 44, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodari, E.; Consiglio, A.; Cannata, M.; La Rosa, V.L. Influence of parental mediation and social skills on adolescents’ use of online video games for escapism: A cross-sectional study. J. Res. Adolesc. 2024, 34, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgülü, Z.; Özer, A. Conditional role of parental controlling mediation on the relationship between escape, daily game time, and gaming disorder. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 3821–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutil, C.; Podinic, I.; Sadler, C.M.; da Costa, B.G.; Janssen, I.; Ross-White, A.; Saunders, T.J.; Tomasone, J.R.; Chaput, J.P. Sleep timing and health indicators in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2022, 42, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viljakainen, H.; Engberg, E.; Dahlström, E.; Lommi, S.; Lahti, J. Delayed bedtime on non-school days associates with higher weight and waist circumference in children: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses with Mendelian randomisation. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e13876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Association between Sleep Duration and Body Mass Index among South Korean Adolescents. Korean J. Health Promot. 2015, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Bixler, E.O.; Berg, A.; Imamura Kawasawa, Y.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Yanosky, J.; Liao, D. Habitual sleep variability, not sleep duration, is associated with caloric intake in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearick-Silva, L.E.; Richter, S.A.; Viola, T.W.; Nunes, M.L. Sleep quality among parents and their children during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. (Rio. J.) 2022, 98, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeer, K.K.; Tarrence, J.; Browning, C.R.; Calder, C.A.; Ford, J.L.; Boettner, B. Family contexts and sleep during adolescence. SSM—Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Rodrigues, D.; Gama, A.; Nogueira, H.; Mascarenhas, L.P.; Padez, C. Sleep duration, risk of obesity, and parental perceptions of residential neighborhood environments in 6–9 years-old children. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2022, 34, e23668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Webb, T.L.; Martyn-St James, M.; Rowse, G.; Weich, S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 60, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.; Kim, N. Correspondence between Parents’ and Adolescents’ Sleep Duration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, J.; Lecarie, E.K.; Park, H.; Doane, L.D. Daily Family Connection and Objective Sleep in Latinx Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Familism Values and Family Communication. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo-Wissar, D.M.; Owusu, J.T.; Nyhuis, C.; Jackson, C.L.; Urbanek, J.K.; Spira, A.P. Parent–child relationship quality and sleep among adolescents: Modification by race/ethnicity. Sleep Health 2020, 6, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, A.; Olivares-Arancibia, J.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H.; López-Gil, J. Socioeconomic Status and Rate of Poverty in Overweight and Obesity among Spanish Children and Adolescents. Children 2024, 11, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).