Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The Greek ASQ-14 demonstrated acceptable reliability. Greek adolescents with high perceived socio-economic status had significantly greater scores in external stress factors and significantly lower scores in internal ones.

- Female adolescents had significantly greater scores in ASQ.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The Greek ASQ-14 responds to the necessity of more viable, concise, and user-friendly stress-assessing instruments for Greek adolescents.

Abstract

Background: Stress has devastating consequences for adolescents’ physical and mental health. Therefore, having the tools to accurately measure it is of critical importance. This paper seeks to evaluate the psychometric characteristics of the Greek version of the 14-item Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ-14), which measures adolescents’ daily experience of common stressors. Methods: The study questionnaire was administered to 176 male and female 15- to 18-year-old students, coming from several regions of Greece. The psychometric characteristics of the Greek ASQ-14 were investigated by confirmatory factor analysis(CFA) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) procedure was applied for measuring sample adequacy. Principal axis factoring (PAF) was chosen as the extraction method and Varimax rotation was used. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Scale intercorrelations were evaluated via Pearson’s r correlation coefficient. The discriminant construct validity was evaluated by analyzing the differences in the ASQ-14 scales between girls and boys, using Student’s t-tests. Results: Two factors emerged: External Pressures and Constraints and Internal Stress and Uncertainty explained 18.5% and 14.5% of the variance, respectively. The Greek ASQ-14 demonstrated acceptable reliability. Concerning discriminant validity, participants with high perceived socioeconomic status had significantly greater scores in “External Pressures & Constraints” and significantly lower scores in “Internal Stress & Uncertainty, while girls had significantly greater scores in both scales and greater total scores than boys. Conclusions: The Greek ASQ-14 emerges as a psychometrically sound tool for screening stress among Greek adolescents.

1. Introduction

1.1. Stress in Adolescence

Adolescents are subject to stress when they interpret a situation as demanding, distressing, or threatening and believe they lack the resources to cope effectively. Stress can be defined as “…the condition that results when person or environment transactions lead the individual to perceive a discrepancy between the demands of a situation and the resources of the person’s biological, psychological and social systems” [1] (p. 128). It arises when homeostasis is, or is perceived to be, under threat [2].

Adolescence is widely recognized as a particularly stressful life stage and is characterized by remarkable plasticity and significant changes in virtually every aspect of an individual’s life; psychological and physiological transformations include brain and body maturation, heightened sensitivity to social and peer relationships, a growing need for independence, and emotional intensity [3]. Major relationship stressors such as the perception of poor support from family, peers, and teachers [4], and other stress factors such as body image anxiety [5], concerns about the future [6], academic stress [7], and socioeconomic adversity [8] contribute to elevated stress levels among adolescents [9] and frequently lead to psychological distress and ineffective coping mechanisms [8]. However, it is not the stressors in themselves that are harmful, but rather the lack of resources that would allow one to cope with them successfully [10].

Stressful life events have been found to predict children’s and adolescents’ mental health problems [11]. Stress has a substantial impact on adolescents’ physical and psychosocial health, shaping stress reactivity [12] and contributing to various psychological dysfunctions like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, which are frequently observed during this phase of development [13]. Furthermore, exposure to stressful life situations during adolescence has been associated with increased perceived stress, which affects both short- and long-term wellbeing [14].

1.2. Assessment of Stress in Adolescence

Given these concerns, accurately measuring adolescent stress is essential for the planning of primary health care and educational services, and demands valid and reliable instruments [10]. Generally, there are three approaches in stress assessment. Firstly, there is the biological or physiological one that uses neuroendocrine biomarkers—such as glucocorticoids and catecholamines—and immunological markers like cytokines, CRP, and IGF-1 [15].

Secondly there is the environmental approach that uses tools which assess stressful life events [15]. Concerning adolescent populations, such measures include:

- (a)

- The Adolescent Perceived Events Scale (APES) [14]: This tool examines positive and negative stressful events experienced during the past six months and has been validated exclusively for use among English- and Spanish-speaking adolescents [16].

- (b)

- The Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ) [17]: Originally developed to assess stress-inducing situations in Australian adolescents, the ASQ has been translated and validated in multiple languages, including Spanish, Dutch, Norwegian, Turkish, and Hungarian [16]. Its long version was also validated in a study in 1240 adolescents from Germany, Hungary, Spain, Greece, and Denmark [18]. Greek versions of the long form, with 58 items [19], and of the 27-item short form [20] of the tool are available.

- (c)

- The Perceived Stressors Global Scale for Adolescents (PSGS-A) [21]: This more recent tool evaluates six categories of stressful events—social pressure, academic stressors, family concerns, social exhibition, daily hassles, and critical incidents. Currently, it has only been validated in a Mexican adolescent population [21].

Thirdly there is the psychological stress assessment approach that uses self-report psychometric tools which measure perceived stress [15]. Regarding adolescents, such instruments include:

- (a)

- The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [22]: This instrument measures how individuals, both adults and adolescents, perceive stress over the preceding four weeks. According to Cohen’s Laboratory for the Study of Stress, Immunity, and Disease, the PSS is suitable for population samples of at least a junior high school education [16]. It has been translated into 25 languages, including Greek, and validated for use in Greek adolescents [23,24,25].

- (b)

- The Stress Appraisal Measure for Adolescents (SAMA), a 14-item questionnaire that measures primary and secondary cognitive appraisal of stress in youth of 14–18 years old, by the use of a 5-point Likert scale [26].

- (c)

- The Impact of Event Scale for adolescents (IES) [27], which is a self-report instrument that assesses current subjective distress and identifies post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

1.3. The Purpose of the Present Study

To date, the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire, both the long-form and 27-item ones, remain the only validated environmental approach stress assessment tools that allow Greek adolescents disclose the stressors they face and the level of strain resulting from them [19]. This gap highlights the need for more reliable, brief, and accessible instruments to assess stress in Greek adolescents. Both the ASQ original form and its shortened 27-item form have been used in Greek populations, mostly concerning validation studies, e.g., [18,19,20]. However, despite the fact that the ASQ has been translated into many languages (e.g., Norwegian, Dutch, Hungarian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Greek) and used worldwide, results regarding its psychometric properties are mixed [20]; empirical studies conducted in Australia [17], Greece [19], New Zealand [28], and Spain [29], have provided support for the adequacy of the factor structure in the long version of the instrument. Conversely, other investigations have raised substantial concerns regarding its structural validity and internal consistency [30], as well as factor loadings [31]. Nevertheless, the predominant body of research characterizes the ASQ as a psychometrically robust and culturally adaptable instrument for assessing stress [20]. Moreover, the availability of abbreviated forms further enhances its utility, while the length of the original long ASQ version remains a practical concern for researchers, especially when it comes to its use in projects that include multiple instruments [32] and in screening stressors in large samples [33]. Concerning the shortened version with 27 items, it does not cover all ten scales of the original ASQ, since the “Stress of emerging adult responsibility” subscale’s items are omitted [33]. Therefore, there would be plenty of benefits to using the ASQ short form of 14 items for the assessment of adolescents’ stressors [33]: it facilitates screening and analyses of stress with other variables, enables the quick carrying out of assessments, increases the likelihood of completion, and provides comprehensive data. The present study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Greek version of the ASQ-14, for use among adolescents aged 15 to 18 years. We hypothesized that the Greek version of the ASQ-14 would have sound psychometric properties. The validation study will offer researchers a Greek version of a short environmental-approach adolescent stress-assessment instrument, well-suited for both research and clinical settings, owing to its brevity and efficiency of administration. Furthermore, the study findings will enhance Greek research concerning the identification, understanding, and prevention of stressors and stress load among adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

The empirical study of the instrument’s psychometric properties using descriptive and exploratory methods took place between April and May 2023. It was conducted by the School of Pedagogical and Technological Education (ASPETE—A.Σ.ΠAΙ.Τ.Ε.)—which is a Greek university that trains secondary school educators—in collaboration with the University of West Attica and the UNESCO Chair on Adolescent Health Care. The study received approval from the Ethics and Conduct Committee of ASPETE (Protocol no: 23-4/4/23).

Eligibility for inclusion required participants to be 15- to 18-year-old students of any of the three grade levels of Greek Lyceums (upper secondary schools). Additionally, students needed to have proficiency in reading, writing, and understanding Greek.

Participants were recruited with the use of an online invitation to the parents of Lyceum students, issued by the study organizers, namely ASPETE, the University of West Attica, and the UNESCO Chair on Adolescent Health Care. The invitation was sent to all Parents’ Associations, and also to parents throughout Greece, via the Hellenic Federation of the Teachers of Tutoring Centers (OΕΦΕ). This invitation presented the purpose of the study, detailed the measures taken to ensure participant anonymity, and included a link to the study questionnaire for parents who consented to their child’s voluntary participation. Students were informed about the study organizers, scope, and time completion (approx. 15 min) on the opening page of the questionnaire. They were able to complete it at home, at their own time of convenience. Upon completion they could download stress-management instructions and techniques for teenagers. A total of 176 high school students from different regions of Greece was considered enough to form the study sample, according to the commonly used “ten participants per item” rule.

2.2. Measures

The study questionnaire required demographic data, such as sex, age, region, etc.; socioeconomic data, such as parents’ profession, parental level of studies, perceived family socioeconomic status, etc.; and school data, such as attending general or special education, general or vocational Lyceum, grade, etc., as well as data regarding students’ daily habits such as routines, type of diet, having breakfast, etc. It also included the Greek version of the long form of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (58 items), which was already validated and found to have sound psychometric abilities for use in Greek adolescents [19].

The long version of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ) comprises 58 items that investigate adolescents’ daily experience of common stressors, categorized in situations across 10 key domains: (i) family environment, (ii) school performance, (iii) school attendance, (iv) romantic relationships, (v) pressure by peers, (vi) interaction with teachers, (vii) uncertainty for the future, (viii) conflicts in the school or leisure environment, (ix) financial strain, and (x) emerging adult responsibility. The ASQ allows adolescents to report the extent to which any such recent stressor has been a psychological pressure for them, by responses recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Not at all stressful) to 5 (Very stressful), with higher scores indicating greater levels of stress [17]. In the present study, a short form of the scale—namely the ASQ-14 [33]—was selected for validation, in order to assess its psychometric properties. The ASQ-14 was created by Blanca and colleagues and consists of 14 items deriving from all ten scales of the original ASQ [33]. No translation was necessary since the ASQ-14 items were all included in the Greek version of the ASQ-58 [19].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were presented as mean values (SD), whereas qualitative variables were summarized as absolute and relative frequencies.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood procedure was conducted in order to test the unidimensional structure of ASQ-14. The fit of the CFA model was assessed by the use of the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Squared Error), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [34]. The guidelines for interpreting the fit of a model based on these indicators are several [35,36,37]. Regarding the CFI and TLI indices, values that are close to or greater than 0.90 are considered to express a good fit to the data. RMSEA values of less than 0.05 reflect a good fit, and values as high as 0.08 indicate a reasonable one. SRMR values of less than 0.08 show a good fit.

Since the questionnaire’s original structure was not found satisfactory, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in order to evaluate the tool’s construct validity, disclose possible underlying structures, and reduce the number of variables. A Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) procedure for measuring sample adequacy was also applied. The cut-off point for factor loadings was 0.40, and for Eigenvalues 1.00. Principal axis factoring (PAF) was chosen as the extraction method. Oblimin rotation was applied initially, but since the correlation between the latent variables was found to be low (i.e., under 0.30), Varimax rotation was used. The internal consistency reliability was examined by means of Cronbach’s alpha analysis. Scales of reliability equal to or greater than 0.70 were considered acceptable. The structure that emerged from the exploratory factor analysis was checked further via confirmatory factor analysis.

Scale intercorrelations were evaluated via Pearson’s r correlation coefficient. The discriminant construct validity was evaluated by analyzing the differences in ASQ-14 scales between girls and boys, and between low and high perceived family SES, using Student’s t-tests.

All the reported p values were two-tailed, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Data analyses were performed by the use of SPSS statistical software (version 27.0) and STATA (version 15).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

The sample consisted of 176 Greek students, with a mean age of 17.1 years (SD = 0.8 years). Their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample’s characteristics.

The majority of the sample were girls (74.4%), and attended the third grade (57.4%) of general Lyceum (upper high school) education (94.8%). Also, 90.6% had siblings, and 86.2% were living with both of their parents. Most of the students characterized their family socioeconomic status as middle (75.6%) and systematically followed a daily program (routine) in everyday life (88.6%).

3.2. ASQ-14 Items

The 14 items of the ASQ-14 are described analytically in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of ASQ-14 items.

For half of our sample students, concerns about their future appeared to be a major stress factor during the past year. Also, 37.5% of the students found the lack of understanding by their parents very stressful. Furthermore, 48.9% of the students did not find not having enough time for their boy/girlfriend stressful, while 44.9% did not find it stressful to have disagreements between them and their teachers.

3.3. Factor Analyses

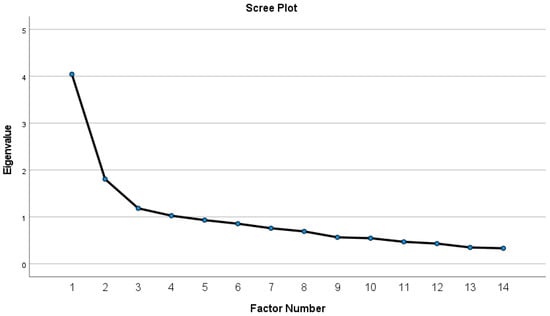

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in order to check the unidimensional structure proposed by the literature. This structure was found unsatisfactory, since all indices were out of the acceptable ranges (CFI = 0.67; TLI = 0.61; RMSEA = 0.120; SRMR = 0.100). Thus, exploratory factor analysis was applied, with Varimax rotation, after evaluating the data and finding it appropriate to perform such an analysis (KMO = 0.78; χ2 = 610.92; p < 0.001 for Bartlett’s test). The scree plot suggested three scales (Figure 1). However, the third factor consisted of only two items, so this factor was discarded, following the guidelines of Raubenheimer [38], and the analysis was rerun by limiting the factors to two. The results are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Scree plot.

Table 3.

Exploratory factor analysis results (item loadings, eigenvalues, percentages of variance explained).

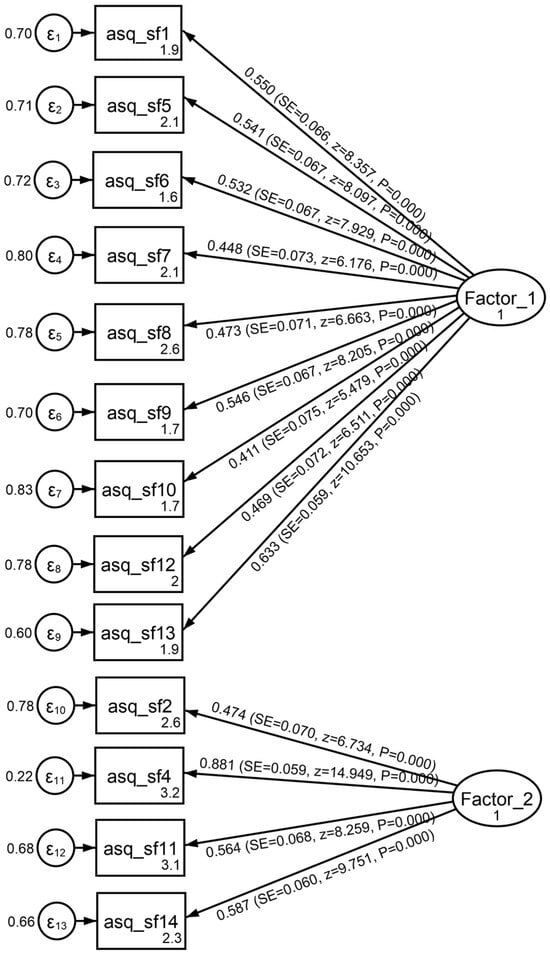

Two factors emerged explaining 33.0% of the total variance. More analytically, the first factor (labeled: External Pressures and Constraints) included nine items (1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) and explained 18.5% of the variance. The second factor (labeled: Internal Stress and Uncertainty) included four items (2, 4, 11, 14) and explained 14.5% of the variance. Item 3 had a loading lower than 0.40 in both factors; thus, it was not grouped in any of the factors. For the rest of the items, their communalities were at least 0.40, and factor loadings ranged from 0.40 to 0.84, supporting the stability of the extracted factor structure. The structure found in the exploratory analysis was also checked via confirmatory factor analysis, and it was found to be within an acceptable range (CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.84; RMSEA = 0.078; SRMR = 0.079). The path diagram is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Path diagram for ASQ-14.

3.4. Internal Consistency and Intercorrelations

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and item-total correlation coefficients for each factor are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and item-total correlation coefficients.

All item-total correlation coefficients were over 0.30, and all reliability indices were at least 0.70. The removal of any of the items within each factor did not significantly change the factor’s reliability index; thus, no item needed to be removed. The overall reliability index was 0.80, indicating acceptable reliability.

Descriptive measures and intercorrelations of the ASQ-14 scales are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Descriptive measures and intercorrelations of ASQ-14 scales.

The mean score in External Pressures and Constraints was 24.44 (SD = 7.38), in Internal Stress and Uncertainty it was 14.19 (SD = 3.74), and the mean total score was 42.13 (SD = 10.09). Significant and positive correlations were found among the two ASQ-SF subscales (r = 0.38; p < 0.001), as well as between all subscales and the total score (r = 0.67, p < 0.001 for Internal Stress and Uncertainty; r = 0.92, p < 0.001 for External Pressures and Constraints).

3.5. Discriminant Validity

In terms of discriminant validity, the ASQ-14 scales were compared between participants with high and low perceived family socioeconomic status (Table 6) and between girls and boys (Table 7).

Table 6.

ASQ-14 scales by perceived family socioeconomic status.

Table 7.

ASQ-14 scales by gender.

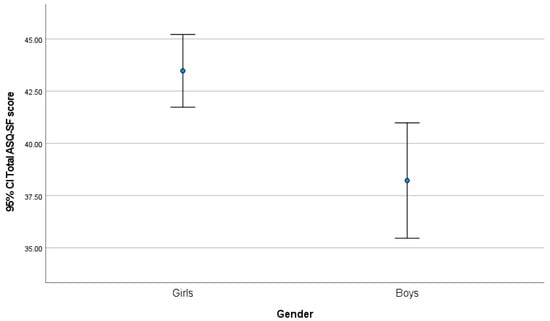

Girls had significantly greater scores on both scales, compared to boys. Also, girls had significantly greater total scores than boys (p = 0.002; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Total ASQ-14 score by sex.

4. Discussion

The presented study is the first validation study of the Greek version of ASQ-14 in a middle adolescent population. The findings indicate that the Greek ASQ-14 provides a brief and dependable measure for future research on Greek adolescents. The original one-factor structure of the scale was not found satisfactory by CFA, so exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with Varimax rotation was used. Our study results show that the structure of the Greek ASQ-14 scale comprises two factors, labeled (a) External Pressures and Constraints and (b) Internal Stress and Uncertainty. The categorization of stressors into external and internal has been used, in general, in the literature concerning adolescent—e.g., [39]— and adult—e.g., [40,41]—stress. The 14-item ASQ has not been used in other validation studies; thus, its one-factor structure has not been confirmed by other researchers. However, there are cases where the factor structure of other ASQ versions has been moderate—e.g., [18]—or not confirmed—e.g., [20,32]. The study’s highest factor loadings in our study appeared in the items a) having difficulty with some subjects and b) having concerns about the future. This finding contradicts that of the authors of the original ASQ-14, who found the highest factor loadings corresponded to the items “lack of understanding by your parents” and “arguments at home” [33]. It also contradicts the findings of Darviri and colleagues’ [19] study concerning the ASQ-58 Greek validation, where the item “lack of freedom” appeared to have the highest factor loading. Nevertheless, having difficulty with subjects can indeed cause a lot of stress to most Greek middle adolescents, since university entrance seems to be not only their own main concern, but their family’s as well [42]; in Greece, the lead-up to the Panhellenic exams is characterized by intense academic pressure and emotional fatigue [42,43]. As for the high factor loading of the item “having concerns about the future”, studies also emphasize that uncertainty about future careers, education, and societal pressures adds to stress, with many adolescents feeling anxious about whether they will be able to handle upcoming responsibilities [6,44]. Another reason for the shift in teen stressors during times of abundance from “lack of understanding”, “arguments at home”, and “lack of freedom” to “having difficulty in school subjects” and “having concerns about the future” during post-Greek financial crisis and also post-COVID-19 crisis times, is that it might also reflect a shift in pressures, according to our opinion. As MacDonald and colleagues [45] state concerning the post-COVID-19 youth, “amidst very rapidly changing political and economic circumstances, continuing precarity for young people seems to be one certainty” [45] (p. 723).

Regarding score reliability, the total scale demonstrated an internal consistency coefficient of 0.80, reflecting adequate reliability, a finding in line with that of the authors of the original ASQ-14 [33], that of De Vriendt and colleagues concerning the original version [18], and that of Ertanir and colleagues regarding the 27-item version [20]. However, this value is lower than the coefficient of 0.95 found by Lima et al. [29] in the ASQ long version, probably due to the smaller number of items, as Blanca and her colleagues explain [33]. All item-total correlation coefficients were over 0.30, which are therefore adequate, as also found by the authors of the original ASQ-14 [25].

For the scale’s discriminant validity, we used perceived family SES, as well as gender, since both those factors’ associations with adolescents’ perceived stress have been well established (e.g., all). Our study results showed that adolescents who felt that their families were of high socioeconomic status had significantly greater scores in “External Pressures and Constraints” and significantly lower scores in “Internal Stress and Uncertainty”. Other researchers have found that subjective socioeconomic status significantly impacts adolescent stress [46] and mental health [47]. Analytically, it has been found that socioeconomic status impacts the brain [48,49], and more specifically, the volume of the hippocampus [50] and amygdala [51]. Concerning Greece, families—especially those of high status—put a high amount of pressure on adolescents during their last years of secondary education, urging them to work as hard as they can to enter university [42]. This fact can explain our finding concerning the high scores of Greek adolescents who feel that their families are of high socioeconomic status in “External Pressures and Constraints”. On the other hand, the same children scored lower in “Internal Stress and Uncertainty”, probably because the perceived high socioeconomic status makes them feel safer regarding concerns about their future, as has been shown not only for Greek adolescents [52], but for adolescents coming from other countries too [53,54]. The study also showed significant differences between boys and girls, with girls scoring higher in both domains and having greater total scores compared to boys. This finding could be impacted by the fact that the majority of the study sample consisted of females; however, it is consistent with the findings of the original ASQ-14 [25], as well as with those of previous researchers [17,18,28,55]. More specifically, research has consistently highlighted notable gender differences in the sources and impacts of stress among adolescents. Female adolescents frequently report higher levels of stress in contexts involving family and peer interactions, where girls tend to perceive negative interpersonal events as more stressful [56]. Furthermore, studies have found that girls often experience greater academic stress than boys [57]. Factors such as increased school workload, emotional factors, and societal expectations have been identified as underlying contributors to this difference [58].

5. Study Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

This study has several limitations. Given the relatively limited sample size and the predominance of female participants, the findings cannot be generalized to the entire adolescent population. However, as the study invitation was sent to parents of adolescents across Greece, the sample included students from all regions of the country. The majority were from Attica and Central Macedonia, home to the capital and co-capital cities. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Attica alone accounts for 37.7% of Lyceum students in Greece (www.statistics.gr (accessed on 10 June 2025), https://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/8fa5c436-3169-54c0-3ad1-1474a9caef0e (accessed on 10 June 2025)), a figure close to the one reflected in our sample. Additionally, the study encompassed students from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Concerning the study’s small sample size, although it meets the conventional “ten participants per item” guideline, we acknowledge that this rule is only a general heuristic. The adequacy of the sample size for factor analysis also depends on characteristics such as item communalities, factor loadings, and the number of factors extracted. While our data showed acceptable communalities and factor loadings, future studies with larger and more diverse samples are warranted to confirm the stability and generalizability of the factor structure. Another limitation is that test–retest reliability was not evaluated, and the study relied solely on self-reported measures with a negative valence. Additionally, the study did not evaluate the stability of the ASQ-14 over time, and the use of a cross-sectional design does not make it possible to infer the direction of causality between the variables. Despite these limitations, the Greek version of the ASQ-14 demonstrated satisfactory validity and reliability, supporting its use in both research and health care settings. Future research should extend the validation of the ASQ-14 to younger adolescents through prospective study designs. Furthermore, incorporating qualitative data on adolescents’ experiences and narratives of stress, as well as examining the relationship between stress and neuroendocrine biomarkers, would provide valuable insights.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that the ASQ-14 serves as a useful rapid psychometric instrument for health professionals in evaluating stress and identifying minor causes of stress during adolescence. As stated by the instrument’s authors, the ASQ-14 could be employed in large adolescent samples to identify those who suffer high levels of stress and are therefore considered at risk and to be targets for detailed assessment [25]. Additionally, the findings underscore the intricate relationship between stressful life situations and adolescent stress levels, reinforcing the importance of effective coping mechanisms and robust social support systems. Facilitating access to counseling services and introducing school-based, ecological interventions may help reduce the adverse effects of stressors on adolescent mental health [59].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., G.P.C. and K.K.; conduction of the study, N.K., G.P.C., A.K. and K.K.; methodology, C.P.; software, C.P.; validation, C.P. and A.K.; formal analysis, C.P.; investigation, N.K. and K.K.; resources, G.P.C.; data curation, C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K. and C.P.; writing—review and editing, K.K., A.K. and G.P.C.; supervision, G.P.C.; project administration, G.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Pedagogical and Technological Education (ASPETE) (Aπ. 2/23-4/4/23, 4 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

At the present, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author because of ongoing analyses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Hellenic Federation of the Teachers of Tutoring Centers (OEFE) http://www.oefe.gr (accessed on 10 June 2025), for their significant help in the implementation of the study. It was the OEFE that sent the study invitation to students’ parents in all Greek regions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASQ | Adolescent Stress Questionnaire |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Confirmatory Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Squared Error |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| PAF | Principal Axis Factoring |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

References

- Caltabiano, M.; Byrne, D.G.; Sarafino, E.P. Health Psychology: Biopsychosocial Interactions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Jones, R.M.; Levita, L.; Libby, V.; Pattwell, S.S.; Ruberry, E.J.; Soliman, F.; Somerville, L.H. The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Dev. Psychobiol. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010, 52, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffge-Krenke, I. Coping with relationship stressors: A decade review. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasoula, E.; Gregoriou, S.; Chalikias, J.; Lazarou, D.; Danopoulou, I.; Katsambas, A.; Rigopoulos, D. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece: Results of a population survey. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2012, 87, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Regueiro, F.; Núñez-Regueiro, S. Identifying salient stressors of adolescence: A systematic review and content analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 2533–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Hetrick, S.E.; Parker, A.G. The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.E.; McMahon, S.D.; Carter, J.S.; Carleton, R.A.; Adam, E.K.; Chen, E. The influence of stressors on the development of psychopathology. In Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S.P.; Reipas, K.; Zelek, B. Stresses, strengths and resilience in adolescents: A qualitative study. J. Prim. Prev. 2019, 40, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Byrne, D.G.; Mazanov, J.; Espnes, G.A. Adolescent stress: Evaluation of the factor structure of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ-N). Scand. J. Psychol. 2010, 51, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, F.; Meyrose, A.K.; Otto, C.; Lampert, T.; Klasen, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R.D. Adolescence: A central event in shaping stress reactivity. Dev. Psychobiol. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010, 52, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiland, L.; Romeo, R.D. Stress and the developing adolescent brain. Neuroscience 2013, 249, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Davis, G.E.; Forsythe, C.J.; Wagner, B.M. Assessment of major and daily stressful events during adolescence: The Adolescent Perceived Events Scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1987, 55, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokka, I.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C.; Bacopoulou, F. Measuring adolescent chronic stress: A review of established biomarkers and psychometric instruments. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023, 96, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, M.S.; Thege, B.K.; Balog, P.; Stauder, A.; Salavecz, G.; Rózsa, S.; Purebl, G.; Ádám, S. Measures of stress in epidemiological research. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, D.G.; Davenport, S.C.; Mazanov, J. Profiles of adolescent stress: The development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). J. Adolesc. 2007, 30, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vriendt, T.; Clays, E.; Moreno, L.A.; Bergman, P.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G.; Nagy, E.; Dietrich, S.; Manios, Y.; De Henauw, S.; HELENA Study Group. Reliability and validity of the adolescent stress questionnaire in a sample of European adolescents-the HELENA study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darviri, C.; Legaki, P.E.; Chatzioannidou, P.; Gnardellis, C.; Kraniotou, C.; Tigani, X.; Alexopoulos, E.C. Adolescent Stress Questionnaire: Reliability and validity of the Greek version and its description in a sample of high school (lyceum) students. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertanir, B.; Rietz, C.; Graf, U.; Kassis, W. A cross-national validation of the shortened version of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ-S) among adolescents from Switzerland, Germany, and Greece. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelata-Eguiarte, B.E.; Gutiérrez-Arenas, V.; Ruvalcaba-Romero, N.A. Construction, validity and reliability of a global scale of perceived stressful events for adolescents. Psychologia. Av. La Discip. 2020, 14, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Lionis, C.; Varvogli, L.; Gnardellis, C.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C. Perceived stress scale: Reliability and validity study in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3287–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Panagiotakos, D.; Zafeiropoulou, A.; Vryonis, M.; Skoularigis, I.; Tryposkiadis, F.; Papageorgiou, C. Validation of a Greek version of PSS-14; a global measure of perceived stress. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmousi, N.; Kounenou, K.; Pezirkianidis, C.; Kalamatianos, A.; Chrousos, G.P. Validation of Perceived Stress Scale-10 Among Greek Middle Adolescents: Associations Between Stressful Life Events and Perceived Stress. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, A.A.; Roesch, S.C.; Jurica, B.J.; Vaughn, A.A. Developing and validating a stress appraisal measure for minority adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2005, 28, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.; Wilner, N.; Alvarez, W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom. Med. 1979, 41, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotardi, V.A.; Watson, P.W. A sample validation of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ) in New Zealand. Stress Health 2018, 35, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.F.; Alarcón, R.; Escobar, M.; Fernández-Baena, F.J.; Muñoz, A.M.; Blanca, M.J. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ-S). Psychol. Assess. 2017, 29, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Espnes, G.A. Evaluation of the Norwegian version of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ-N): Factorial validity across samples. Scand. J. Psychol. 2011, 52, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, M.T.; Percy, A.; Byrne, D.G. Support for the multidimensional adolescent stress questionnaire in a sample of adolescents in the United Kingdom. Stress Health 2016, 32, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andretta, J.R.; McKay, M.T.; Byrne, D.G. Psychometric properties of the adolescent stress questionnaire-short form scores and association with self-efficacy. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca-Mena, M.J.; Escobar-Espejo, M.; Lima-Ramos, J.F.; Byrne, D.; Alarcón-Postigo, R. Psychometric properties of a short form of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ-14). Psicothema 2020, 32, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R. Basic Principles of Structural Equation Modeling; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenspoon, P.J.; Saklofske, D.H. Connfirmatory factor analysis of the multidimensional Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, J. An Item Selection Procedure to Maximise Scale Reliability and Validity. S. Afr. J. Ind. Psychology. 2004, 30, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watode, B.; Kishore, J. Stress management in adolescents. Health Popul. Perspect. Issues 2011, 34, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Alsentali, A.M.; Anshel, M.H. Relationship between internal and external acute stressors and coping style. J. Sport Behav. 2015, 38, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Soffer-Dudek, N.; Shahar, G. Evidence from two longitudinal studies concerning internal distress, external stress, and dissociative trajectories. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 2014, 34, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka, E.; Bacopoulou, F.; Manousou, K.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C. Educational stress among Greek adolescents: Associations between individual, study and school-related factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulou, I.; Efstathiou, V.; Korkoliakou, P.; Triantafyllou, G.; Smyrnis, N.; Douzenis, A. Mental health of adolescents amidst preparation for university entrance exams during the second pandemic-related lockdown in Greece. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2022, 8, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J.; Žukauskienė, R.; Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R.; King, H.; Murphy, E.; Gill, W. The COVID-19 pandemic and youth in recent, historical perspective: More pressure, more precarity. J. Youth Stud. 2024, 27, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursache, A.; Noble, K.G.; Blair, C. Socioeconomic status, subjective social status, and perceived stress: Associations with stress physiology and executive functioning. Behav. Med. 2015, 41, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, E.C.; McGrath, J.J. Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, E.A.; Tindle, R.; Pawlak, S.; Bedewy, D.; Moustafa, A.A. The impact of poverty and socioeconomic status on brain, behaviour, and development: A unified framework. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 35, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, K.G.; Houston, S.M.; Kan, E.; Sowell, E.R. Neural correlates of socioeconomic status in the developing human brain. Dev. Sci. 2012, 15, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Race, ethnicity, family socioeconomic status, and children’s hippocampus volume. Res. Health Sci. 2020, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Boyce, S.; Bazargan, M. Subjective socioeconomic status and children’s amygdala volume: Minorities’ diminish returns. NeuroSci 2020, 1, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioakimidis, M.; Papakonstantinou, G. Socioeconomic status and its effects on higher education opportunity: The case of Greece. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2017, 7, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, J. Concern or confidence? Adolescents’ identity capital and future worry in different school contexts. J. Adolesc. 2016, 46, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, T. Understanding Adolescent Future Expectations: Socioeconomic Status and the Mediating Role of Just World Beliefs. Master’s Thesis, Youth Development and Social change, Ymke de Bruijn, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Moljord, I.E.; Espnes, G.A.; Byrne, D.G. The association between stress and emotional states in adolescents. The role of gender and self-esteem. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Rudolph, K.D. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emo-tional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, C.; Han, L. Gender difference in anxiety and related factors among adolescents. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1410086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, I.; Paniagua, C.; Jiménez-Iglesias, A. Gender differences in adolescent school stress: A mixed-method study. J. Res. Adolesc. 2025, 35, e13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiss, R.; Dolinger, S.B.; Merritt, M.; Reiche, E.; Martin, K.; Yanes, J.A.; Thomas, C.; Pangelinan, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based stress, anxiety, and depression prevention programs for adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1668–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).