Abstract

Background: Children today are growing up in a digital environment where screen-based technology is a central part of everyday life. While screens can offer educational and recreational benefits, there is growing concern about their influence on different areas of child development. Objective: This review explored how screen time affects developmental outcomes in children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years, focusing on physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains. Methods: A structured search was carried out across databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and PsycINFO to identify relevant studies published between 2014 and 2024. Studies were included if they examined the relationship between screen time and at least one area of child development, involved participants within the target age group, and were peer-reviewed and published in English. The review followed PRISMA guidelines, and articles were independently screened and evaluated for quality by two reviewers. Results: A total of 46 studies met the inclusion criteria. Overall, the evidence points to a link between higher levels of screen use and negative outcomes such as reduced physical activity, poorer sleep, attention difficulties, and challenges in emotional and social functioning. However, some studies indicated that limited or educational screen use, especially with parental involvement, may have neutral or even positive effects in certain contexts. Conclusions: Screen time can have both positive and negative effects on child development, depending on factors like duration, type of content, and the context in which screens are used. Managing screen use through age-appropriate guidelines and adult supervision may help reduce risks and promote healthier development. More longitudinal research is needed to establish clearer recommendations for screen use in childhood.

1. Introduction

Screen time has become a necessary component of daily living in the current digital age, especially for kids [1,2]. Since cell phones, tablets, laptops, and televisions are so common, kids are exposed to digital media at a young age [3]. Even though screen time has educational and entertainment value, worries about how technology affects kids’ development are becoming more and more prevalent. Concerns over the impact of excessive screen time on cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development are growing among experts and parents [2,3,4]. According to research, screen time can have both positive and negative effects, depending on the child’s age, the type of content viewed, and the length of exposure. Overuse of screens has been connected to issues like lack of physical exercise, attention problems, language delays, and impaired social skills [2,4]. However, some forms of screen time in the classroom can help students acquire abilities like digital literacy and problem-solving [4].

Current evidence on the effect of mobile phone radiation (radiofrequency electromagnetic fields, RF-EMF) and congenital problems is limited and inconclusive [5,6,7]. Unlike ionizing radiation (X-rays, gamma rays), RF-EMF is non-ionizing and does not have enough energy to directly damage DNA. Large cohort studies (e.g., Danish National Birth Cohort, MoBa study in Norway) have not shown strong associations between maternal mobile phone use and major congenital malformations [8,9,10,11]. Some studies suggested possible links to behavioral problems or subtle neurodevelopmental effects in children, but results are not consistent [8,9].

The purpose of this narrative review was to examine the body of evidence on the effects of screen usage on children’s development. It highlighted how screen time affects children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development and provided advice on how to appropriately manage screen time to support kids’ general well-being. This analysis looked at the complex relationship between screen time and child development in an effort to guide future studies and help parents, guardians, and legislators make wise choices regarding their kids’ screen time.

2. Materials and Methods

This review summarized studies examining how children’s screen usage affects their cognitive, emotional, social, and physical development. A range of study designs and data sources were examined in order to provide a comprehensive grasp of this subject.

2.1. Study Inclusion Criteria

The selection of studies was based on their emphasis on the association between screen time exposure and developmental outcomes, such as behavior, emotional control, physical health, and cognitive capacities, in children ages 0–18. To cover various research viewpoints, the review incorporated randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies.

2.2. Data Collection

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO and other databases were the sources of the examined papers. Most of the studies included were papers from medical and psychological societies, reports from health organizations, and peer-reviewed journals. The review included studies from the last 10 years.

2.3. Research Methodology

A variety of research designs were used:

- Quantitative research: These studies primarily used surveys and questionnaires to assess screen time exposure (length, kind of material, and devices used) to examine developmental outcomes like academic achievement, cognitive abilities, and behavioral changes.

- Qualitative research: To learn more about how parents, guardians, and educators perceive the effects of screen usage on kids, researchers interviewed these participants. Family dynamics and the emotional impacts of screen time were also examined through focus groups.

- Mixed-methods research: Some researchers blended quantitative and qualitative approaches, merging statistical analysis with in-depth interviews and observations to offer a more holistic perspective.

2.4. Measured Outcomes

The research evaluated a number of developmental outcomes, such as the following:

- Cognitive development: memory, language acquisition, and academic success.

- Emotional and social development: Social skills, emotional control, behavioral adaptations, and the growth of empathy.

- Physical health metrics: Body mass index (BMI), activity level, sleep quality, and the development of motor skills.

- Mental health: Problems such as anxiety, depression, and the psychological effects of excessive screen usage.

2.5. Data Analysis Techniques

The data was analyzed using a variety of statistical methods, e.g., descriptive statistics to compile the study populations’ characteristics and screen time exposure. Regression analysis was used to ascertain how screen time and developmental outcomes are related.

2.6. Criteria for Study Selection

Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to explore the impact of screen time on children’s development. The inclusion criteria targeted the following types of studies:

- Involving children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years;

- Examining the relationship between screen use (e.g., screen time, digital media exposure) and developmental outcomes (physical, social, emotional, or cognitive);

- Published in peer-reviewed journals within the last 10 years (1 January 2015–31 December 2024);

- Written in English.

Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and PsycINFO. Boolean operators were used to construct the search strategy. The search string used was as follows:

(“screen time” OR “screen use” OR “digital media” OR “media exposure” OR “electronic media”)

AND (“child*” OR “adolescent*” OR “infant*” OR “toddler*” OR “teen*” OR “youth”)

AND (“development” OR “cognitive development” OR “social development” OR “emotional development” OR “physical development”)

AND (“impact” OR “effect*” OR “association*” OR “relationship*”)

Filters were applied to limit the results to English-language articles published in the past 10 years in peer-reviewed journals. The study selection process involved screening titles and abstracts, followed by full-text review. Duplicates and irrelevant studies were removed.

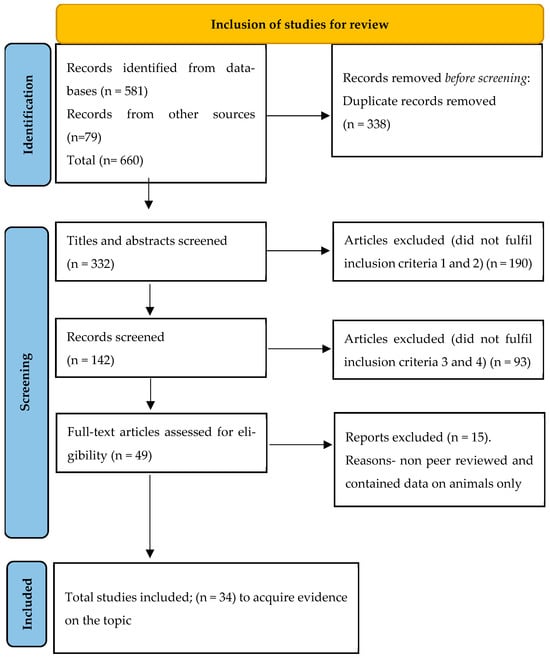

A PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study inclusions.

3. Results and Discussion

A total of thirty-four studies were included in Table 1, exploring the impact of screen time on development of children.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and key findings.

3.1. Understanding Screen Time

3.1.1. Definition of Screen Time

“Screen time” refers to the amount of time individuals spend using devices with screens—such as smartphones, tablets, computers, televisions, and gaming consoles. Activities range from passive consumption (e.g., watching television, browsing social media) to interactive engagement (e.g., educational games, coding, or creative digital projects) [1].

Types of screens include the following:

- Smartphones and tablets: Portable devices used for communication, entertainment, and productivity.

- Computers and laptops: Common tools for work, education, and digital entertainment.

- Televisions: Initially used for broadcasting news and entertainment, now widely used for streaming digital content.

- Gaming consoles: Devices primarily designed for video gaming, offering both recreational and social experiences.

3.1.2. Guidelines and Recommendations for Screen Time Usage by Age Group

To support parents and caregivers, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other experts offer guidance tailored to children’s developmental stages (Table 2) [2,3].

Table 2.

AAP guidelines for screen time usage.

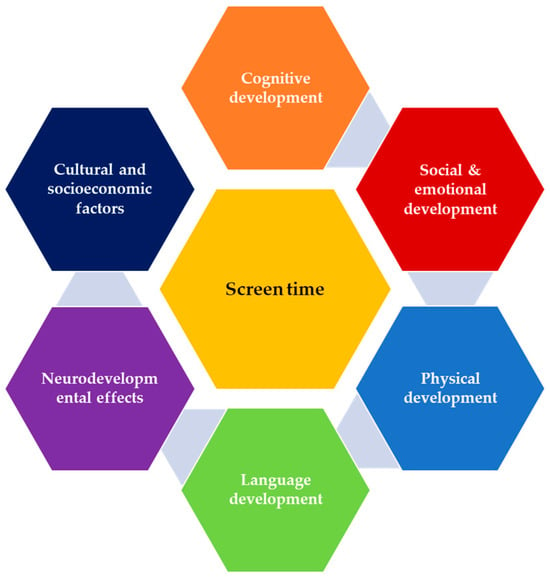

Figure 2 represents the multidimensional impact of screen time on child development, highlighting several interconnected domains.

Figure 2.

Multidimensional impact of screen time on child development.

3.2. Cognitive Development

The increasing integration of digital devices into children’s routines raises important questions about their effect on cognitive development, defined as the set of mental processes that enable learning, reasoning, problem-solving, and understanding. Though digital media presents risks, it can also offer developmental benefits if used appropriately [4,44,45].

3.2.1. Positive Aspects of Screen Time on Cognitive Development

Not all screen time is detrimental. When used mindfully, certain digital tools can promote creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. Educational programs such as “Sesame Street” have been shown to support early math and literacy skills [46]. Interactive apps that focus on storytelling, puzzles, or coding can enhance memory, cognitive flexibility, and attention span. Studies demonstrate that high-quality media exposure can have measurable cognitive benefits. For instance, children exposed to educational programming often exhibit stronger language development and better problem-solving skills than those who consume non-educational media [47].

3.2.2. Negative Effects of Screen Time on Cognitive Development

Conversely, excessive or low-quality screen time may have adverse effects. Fast-paced or overstimulating content—like action-filled video games or rapid-fire cartoons—has been associated with reduced attention span and difficulty focusing on sustained tasks [19]. A particularly concerning area is language development. Children under two who engage in more passive media use tend to have delayed language acquisition, possibly due to less interaction with caregivers [48]. Excessive screen use has also been linked to deficits in executive function—including planning, self-regulation, and delayed gratification [49]. Activities that reward instant responses, such as games or scrolling feeds, may impair children’s ability to engage in thoughtful, goal-directed behavior.

3.2.3. Content and Context of Screen Time

The quality and context of screen use are just as important as quantity. Interactive and educational content promotes engagement and learning, while passive viewing can be detrimental [50]. According to the AAP, limiting screen time to one hour per day for children aged 2–5, and ensuring consistent limits for older children, can help maintain developmental balance [2]. Parental involvement remains essential. When caregivers participate by co-viewing, discussing content, or playing educational games, screen time becomes a more socially and cognitively enriching experience. In contrast, solitary screen use is associated with delays in language acquisition and social skill development [51].

3.3. Social and Emotional Development

Social and emotional development refers to a child’s ability to understand and manage emotions, establish healthy relationships, and navigate social environments. This foundation is essential not only for emotional well-being but also for long-term success in school, relationships, and life. Table 3 summarizes the effect of screen time on social and emotional development in children [12,13,14,28,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60].

Table 3.

Effect of screen time on social and emotional development.

3.4. Physical Development

Physical development is a foundational component of overall child health. It encompasses growth, motor skill acquisition, and the formation of long-term health behaviors. With the increasing dominance of screen time in children’s routines, there are growing concerns about its potential effects on physical well-being. A major concern with excessive screen time is its tendency to replace physical activity. As screen use increases, time spent engaging in movement, which is crucial for muscle development, bone health, and energy expenditure, tends to decline. This reduced activity contributes to slower metabolism, loss of muscle mass, and an increased risk of childhood obesity [61]. Screen time is also associated with increased caloric intake. Mindless snacking while watching TV or gaming can lead to overeating, particularly of unhealthy foods, which further contributes to weight gain [62]. Prolonged sitting and reduced movement additionally contribute to metabolic dysregulation, raising risks for conditions such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [63].

3.4.1. Effects on Sleep Patterns and Quality

The blue light emitted by screens can suppress melatonin production, a hormone essential for regulating sleep cycles. This disruption can delay sleep onset and lower sleep quality, especially when devices are used close to bedtime [64]. Irregular sleep patterns affect cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and immune function. Children who do not get enough quality sleep may struggle with attention, memory, and mood, and may be at increased risk of developing chronic health issues [65].

3.4.2. Visual Health

Screen overuse is also associated with computer vision syndrome, a condition characterized by eye strain, dry eyes, headaches, and blurred vision after prolonged screen exposure [66]. Moreover, increased screen time—especially up close—is a documented risk factor for myopia (nearsightedness), which is becoming more prevalent in children globally [67].

3.5. Language Development

Language development is critical for communication, literacy, and social connection. It includes the ability to comprehend, use vocabulary, and form grammatical structures. With screens now occupying a significant place in children’s daily lives, it is essential to evaluate how screen time influences language learning.

3.5.1. Role of Screen Time in Language Acquisition and Communication Skills

Passive screen time (e.g., TV viewing) offers minimal interactive engagement. Children receive information without opportunities for conversational exchange, which limits essential turn-taking and back-and-forth dialogue that supports language development [68]. Passive viewing can reduce attention span and the ability to engage in language-rich environments [25]. In contrast, interactive screen time (e.g., educational apps) can encourage language learning when designed with development in mind. These platforms can foster vocabulary growth, comprehension, and phonological awareness through responsive and engaging exercises [69].

3.5.2. Comparison Between Passive and Interactive Screen Time

Passive media lacks meaningful interactivity and often fails to support sustained language learning. By contrast, well-designed interactive tools offer engaging, child-directed content that supports verbal expression and cognitive processing. When combined with parental engagement, such platforms can enhance language acquisition and literacy skills [70].

3.5.3. Potential Delays in Language Development Due to Excessive Screen Exposure

A significant consequence of screen overuse is the decline in caregiver–child interaction. Real-time conversation with adults supports the development of syntax, semantics, and social language. Without it, children may lack the scaffolding needed for proper language development [71]. Screen time also limits exposure to diverse language inputs—the rich, complex, and contextually meaningful conversations found in daily interactions. This can result in restricted vocabulary growth and impaired pragmatic language use [72].

Furthermore, children may experience delayed social communication development. Skills such as interpreting body language, managing conversation flow, and understanding tone are best learned in live social settings. Screen time, especially when excessive, may hinder these essential abilities [73]. Excessive use can also impact a child’s attention span, making it harder for them to stay engaged in conversations, storytelling, or group learning, all of which are vital for language development [15].

3.6. Neurodevelopmental Effects

With technology becoming more and more ingrained in daily life, research on the effects of screen time on brain development particularly with regard to neuroplasticity and gray matter, has grown significantly. Table 4 summarizes the effect of screen time on neurodevelopment in children [16,17,23,27,42,43].

Table 4.

The effect of screen time on neurodevelopment.

Numerous studies have examined how screen usage affects kids’ attention and cognitive development, as well as any possible connections to attention problems including attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and cognitive impairments. Several important conclusions have been drawn from the evidence thus far, even if more research is required to prove clear cause-and-effect relationships:

- Increased risk of ADHD Symptoms:

- Attention and focus: Children’s attention spans have been linked to extended screen time, especially when it comes to fast-paced, interactive media (such as social media or video games). Children may find it more difficult to concentrate on less engaging activities (such as homework or chats) as a result [16].

- Hyperactivity: Excessive screen time, especially when it comprises high-energy content, may be a contributing factor to hyperactive behavior, according to several studies. Although the relationship is complicated and not entirely understood, this is consistent with symptoms of ADHD. While some studies contend that excessive screen time may worsen pre-existing symptoms of ADHD, others imply that children with ADHD may be more drawn to screen-based activities [27].

- Cognitive delays and developmental concerns:

- Delayed language development: Language development delays may occur in young children who spend a lot of time on screens. Activities like reading and in-person interactions that are essential for language learning are frequently replaced by screen usage. Verbal communication, vocabulary development, and other cognitive abilities may be impacted by these delays [16].

- Impact on executive function: Overuse of screens, particularly during early childhood, has been associated with a decline in the development of executive skills like memory, self-control, and problem-solving. Given the importance of executive processes to both academic achievement and general cognitive development, this is especially worrisome [23,42].

3.7. Parental Mediation and Screen Time Management

3.7.1. The Role of Parents in Moderating Screen Time Usage

In the current digital era, where screens are a necessary component of everyday life, parents need to actively monitor and establish limits to make sure that technology use stays constructive and in moderation. Table 5 enumerates parental strategies in moderating screen time usage in children [26,74,75].

Table 5.

Parental strategies in moderating screen time usage.

3.7.2. Mediation Strategies

Techniques that seek to improve or direct kids’ media experiences in a constructive manner are known as positive mediation. Promoting media use and interaction in a healthy way is the main goal. In order to avoid any potential negative impacts, negative mediation techniques usually try to limit or restrict children’s media exposure. These tactics put more of an emphasis on exposure limitation and control. Table 6 enumerates parental mediation strategies in moderating screen time usage in children [18,29,30,31,76].

Table 6.

Mediation strategies.

Impact of Parental Screen Time Habits on Children

Given that kids frequently imitate their parents’ behavior, the effects of parental screen time habits on kids are a crucial subject. The quantity and caliber of screen time parents spend with their kids can have a variety of effects on their development.

1. Modeling behavior—Children may learn to spend too much time on screens if their parents do, which could result in them using screens excessively as well [77]. They may develop a dependence on screens if their parents use computers, cell phones, or tablets frequently and subtly teach them that these gadgets are the preferred means of communication or amusement [20].

2. Effects on parent–child interaction—Parents who spend too much time on screens may engage with their kids less in person. Time spent on electronics, particularly social media or work-related activities, has been shown to disrupt genuine, interesting talks between parents and kids [21]. Insufficient in-person engagement can impede emotional attachment, diminishing chances for kids to cultivate empathy, communication abilities, and emotional control. For social and emotional development, children benefit greatly from interaction with their parents [32].

3.8. Cultural and Socioeconomic Factors

Children’s screen time and how it is viewed, controlled, and incorporated into daily life are greatly influenced by cultural attitudes toward technology. The degree to which technology is used and how it is perceived in relation to education, entertainment, and socialization are influenced by these views, which differ among nations, communities, and family environments [22,33]. These cultural elements may have the following effects on kids’ screen time:

- Perceptions of technology’s role in development

- o

- Positive attitudes: Screen time may be more acceptable in societies that view technology as a necessary educational tool. Increased screen time for activities like learning apps, online learning, and virtual classrooms may be permitted or even encouraged by parents and educators. This is frequently observed in settings that place a high value on the potential of technology to improve education.

- o

- Negative attitudes: In cultures where there is skepticism about the effects of screen time on child development, particularly its impact on attention span, physical health, and social skills, there may be more restrictions. For instance, some societies place a high value on outdoor play, face-to-face interactions, or hands-on learning, leading to limited use of screens [22].

- Technological accessibility and affordability

- o

- Wealthier countries: In more affluent societies where access to personal devices (smartphones, tablets, computers) is widespread, screen time may be higher, with children using technology for entertainment, socializing, and schoolwork. Technology may be integrated into daily life as a necessity, with cultural expectations that children will be adept at using these devices from a young age [33].

- o

- Developing regions: In lower-income or developing areas, the use of technology may be less common or more restricted. Cultural norms in these areas may prioritize physical activities, community-based education, or traditional play, which can result in less screen time for children. However, access to technology may be increasing, and in some cases, the influence of global trends may shift attitudes.

Global Perspectives on Screen Time and Child Development

According to recommendations from the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) and the AAP, children under the age of two should not use screens at all, while older children should only use screens for one to two hours per day [22,33]. These recommendations stress that screen time should not get in the way of sleep, exercise, or in-person relationships. Sweden and the UK are two European nations that have adopted progressive approaches to screen time management, with differing degrees of emphasis on children’s digital well-being. Public health programs that emphasize balanced screen usage have also been used in the UK to address this issue [34]. In order to encourage healthier lives, the National Health Service (NHS) advises parents to establish limits and limit their young children’s screen usage [24]. Children are exposed to screens at younger ages in nations like South Korea and Japan, where technology is ingrained in daily life. Nonetheless, South Korea has taken the lead in combating digital addiction by introducing initiatives to assist kids in cutting back on screen time and encouraging better online practices [78]. To curb excessive use, the government of the nation has implemented programs like “Digital Detox” and other measures. China has also put laws into place to safeguard the health of children, especially with regard to video games. Children’s online gaming was restricted by the Chinese government in 2021 to three hours per week [79]. On the other hand, attitudes toward screen time are more varied in nations like India, where excessive screen time is more common in cities, particularly as cell phones get cheaper. On the other hand, screen time is generally lower in rural areas. There is a growing awareness of the need for rules as a result of parents’ increased concerns about screen usage, especially in middle-class urban households.

3.9. Potential Benefits of Screen Time

3.9.1. Educational Content and Digital Literacy

When utilized for instructional reasons, screen time can be very advantageous. Access to a wide range of educational resources, including those related to science, math, and languages, is made possible by digital platforms and applications. By encouraging students to participate in interactive learning, these resources can make learning more approachable and enjoyable. Instructional videos, e-books, and educational games may accommodate a variety of learning preferences and make difficult subjects fun for students to understand [35,80].

3.9.2. Development of Technological Skills and Preparedness for Future Careers

Early screen time exposure aids in the development of vital abilities that are essential in today’s workforce. Children and teenagers can learn digital communication, problem-solving techniques, and coding. Well-planned screen time can foster the growth of creativity, critical thinking, and teamwork, particularly when utilizing interactive programs and collaborative platforms [36]. Additionally, since technology has a significant impact on many businesses nowadays, it is becoming more and more crucial for students preparing for future employment to comprehend digital tools, software, and online platforms. Understanding technologies such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality is crucial for future job preparation because they are revolutionizing many industries [37,44,81]. People can also produce and express themselves artistically through a variety of digital platforms, including graphic design tools, video editing software, and music creation apps. Whether creating video games, podcasts, or digital art, these endeavors encourage creativity and can provide a creative outlet [81].

3.10. Interventions and Recommendations

In order to mitigate the detrimental consequences of excessive screen time, a number of interventions and suggestions have been developed as research into these impacts continues. Parental guidance, active involvement, and mediation are some of the best strategies for controlling screen time. The AAP suggests that parents clearly limit their children’s screen use to no more than an hour per day for those between the ages of two and five [38]. Since getting enough sleep is crucial for healthy brain development, cutting back on screen time before bed can enhance the quality of sleep, which supports cognitive processes like memory and emotional control. According to WHO guidelines, children under the age of two should not use screens at all, and those between the ages of two and four should not spend more than an hour a day on them [82]. Encouraging alternative activities like social engagement, outdoor play, and physical activity balances out the sedentary behavior that is frequently linked to excessive screen usage. Establishing areas of the house where screens are not allowed can be a successful intervention [39,40]. Not all screen time is bad, particularly if kids are interacting with instructional materials that encourage active learning. Interactive games and age-appropriate programming have been shown to enhance cognitive abilities like memory, problem-solving, and language development. Prioritizing interactive media above passive content is crucial. Particularly helpful for cognitive growth are apps and games that promote critical thinking, problem solving, or teamwork [41,83]. Additionally, communities and schools may make a significant contribution by putting in place educational initiatives that emphasize the value of consuming media in moderation. Together, families, schools, and medical professionals may establish a nurturing atmosphere that promotes responsible media use [38,82].

Study Limitations

The studies that were reviewed had certain limitations. The consistency of results was impacted by variations in study design, sample size, and outcome measurement instruments. Additionally, a number of studies failed to take into consideration potential confounders that could affect the results, such as parental influence, socioeconomic position, and pre-existing medical issues.

4. Conclusions

Children’s development is impacted by screen time in a variety of ways, both positively and negatively. The hazards linked with excessive screen time can be reduced by implementing treatments like parental mediation, screen exposure limits, non-screen activities, and the promotion of high-quality educational content. Clear policy guidelines and public health measures are also necessary to help families effectively manage screen use. Children will be able to navigate the digital age in a way that promotes healthy cognitive, emotional, and social development with the support of ongoing research, cooperation, and education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.K., R.D., B.K.M.G., Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S. and R.N.M.A.K.F.; methodology, Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S. and R.N.M.A.K.F.; software, S.S.K. and Q.S.G.; validation, Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S. and R.N.M.A.K.F.; formal analysis, Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S., R.N.M.A.K.F. and S.S.K.; investigation, R.D. and B.K.M.G.; resources, Q.S.G. and R.D.; data curation, Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S., R.N.M.A.K.F. and S.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S., R.N.M.A.K.F. and S.S.K.; writing—review and editing, Q.S.G., R.D. and B.K.M.G.; visualization, Q.S.G. and S.S.K.; supervision, Q.S.G., A.A.E.-B., T.A.A.S. and R.N.M.A.K.F.; project administration, Q.S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. Screen Time and Children. 2020. Available online: https://share.google/81yZbE4tnToPgBnmQ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Healthy Digital Habits. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/campaigns-and-toolkits/healthy-digital-habits/?srsltid=AfmBOorU0D6GWA25lXQWkwXjz64BzQXQUqc5IUDGjW6AsY-0SD8EJ1jn (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- McArthur, B.A.; Tough, S.; Madigan, S. Screen time and developmental and behavioral outcomes for preschool children. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Magson, N.R.; Johnco, C.J.; Oar, E.L.; Rapee, R.M. Parental Control of the Time Preadolescents Spend on Social Media: Links with Preadolescents’ Social Media Appearance Comparisons and Mental Health. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divan, H.A.; Kheifets, L.; Obel, C.; Olsen, J. Prenatal and Postnatal Exposure to Cell Phone Use and Behavioral Problems in Children. Epidemiology 2008, 19, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, R.; Kar, S.S.; Bahutair, S.N.M.; Kuruba, M.G.B.; Shafi, S.; Zaidi, H.; Garg, H.C.; Almas, Y.M.; Kidwai, A.; Zalat, R.A.F.; et al. The Fetal Effect of Maternal Caffeine Consumption During Pregnancy—A Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, A.; Abuhijleh, S.A.; Fatah, A.; Mohsin, M.M.; Kar, S.S.; Dube, R.; George, B.T.; Kuruba, M.G.B. Infantile Neuroaxonal Dystrophy: Case Report and Review of Literature. Medicina 2024, 60, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudan, M.; Kheifets, L.; Arah, O.A.; Olsen, J. Cell phone exposures and hearing loss in children in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2013, 27, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, E.; Haugen, M.; Schjølberg, S.; Magnus, P.; Brunborg, G.; Vrijheid, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Alexander, J. Maternal Cell Phone Use in Early Pregnancy and Child’s Language, Communication and Motor Skills at 3 and 5 Years: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahyouni, J.K.; Odeh, L.B.M.; Mulla, F.; Junaid, S.; Kar, S.S.; Al Boot Almarri, N.M.J. Infantile Sandhoff disease with ventricular septal defect: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 16, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehhi, N.T.; Alnuaimi, A.Y.; Sahib, T.K.; Bazar, K.A.O.; Kar, S.S.; Dube, R. Pattern and profile of different thyroid dysfunctions in Down Syndrome. J. Adv. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2025, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 2015, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J.; Prinstein, M.J. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Rogers, A.A.; Zurcher, J.D.; Stockdale, L.; Booth, M. Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, D.A.; Ramirez, J.S.B.; Ferguson, S.M.; Ravinder, S. How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: A review of results from observations inhumans and experiments in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9851–9858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.S.; Dudley, J.; Horowitz-Kraus, T.; DeWitt, T.; Holland, S.K. Associations between screen-based media use and brain white matter integrity in preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e193869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz-Kraus, T.; Hutton, J.S. Brain connectivity in children is increased by the time they spend reading books and decreased by the length of exposure to screen-based media. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2018, 107, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, G.S.; Li, D.D.; Liau, A.K.; Khoo, A. Moderating effects of the family environment for parental mediation and pathological Internet use in youths. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillard, A.S.; Drell, M.B.; Richey, E.M.; Boguszewski, K.; Smith, E.D. Further examination of the immediate impact of television on children’s executive function. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Lee, Y.H. The moderating effects of Internet parenting styles on the relationship between Internet parenting behavior, Internet expectancy, and Internet addiction tendency. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2017, 26, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, K.M.; Coyne, S.M.; Rasmussen, E.E.; Hawkins, A.J.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Erickson, S.E.; Memmott-Elison, M.K. Does parental mediation of media influence child outcomes? A meta-analysis on media time, aggression, substance use, and sexual behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr. Child Health 2019, 24, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Media and young minds. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. How Much Screen Time Should Children Have? Available online: https://share.google/dJbpR62EoewbfGFqz (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Bedford, R.; Urabain, I.R.S.; Cheung, C.H.M.; Karmiloff-Smith, A.; Smith, T.J. Toddlers’ Fine Motor Milestone Achievement Is Associated with Early Touchscreen Scrolling. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.R.; Subrahmanyam, K.; Cognitive Impacts of Digital Media Workgroup. Digital Screen Media and Cognitive Development. Pediatrics 2017, 140 (Suppl. S2), S57–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Browne, D.; Racine, N.; Mori, C.; Tough, S. Association Between Screen Time and Children’s Performance on a Developmental Screening Test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Twenge, J.M.; Spitzberg, B.H.; Campbell, W.K. Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 1892–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P.; Squeglia, L.M.; Bagot, K.; Jacobus, J.; Kuplicki, R.; Breslin, F.J.; Bodurka, J.; Morris, A.S.; Thompson, W.K.; Bartsch, H.; et al. Screen media activity and brain structure in youth: Evidence for diverse structural correlation networks from the ABCD study. Neuroimage 2019, 185, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crone, E.A.; Konijn, E.A. Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.; Rees, P.; Hale, L.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Paradkar, M.S. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.H.M.; Bedford, R.; de Urabain, I.R.S.; Karmiloff-Smith, A.; Smith, T.J. Daily touchscreen use in infants and toddlers is associated with reduced sleep and delayed sleep onset. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Krizan, Z.; Hisler, G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med. 2017, 39, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernon, L.; Modecki, K.L.; Barber, B.L. Mobile phones in the bedroom: Trajectories of sleep habits and subsequent adolescent psychosocial development. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, K.; Pecor, K.; Malkowski, M.; Kang, L.; Machado, S.; Lulla, R.; Heisey, D.; Ming, X. Effects of instant messaging on school performance in adolescents. J. Child Neurol. 2016, 31, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøntved, A.; Singhammer, J.; Froberg, K.; Møller, N.C.; Pan, A.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Kristensen, P.L. A prospective study of screen time in adolescence and depression symptoms in young adulthood. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maras, D.; Flament, M.F.; Murray, M.; Buchholz, A.; Henderson, K.A.; Obeid, N.; Goldfield, G.S. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev. Med. 2015, 73, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Yao, S. Dose-response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N.; Campbell, W.K. Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 2018, 18, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, J.; Sanders, W.; Forehand, R. Youth screen time and behavioral health problems: The role of sleep duration and disturbances. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016, 37, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J.S.; Christakis, D.A. Increased screen time: Implications for early childhood development and behavior. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 63, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; McArthur, B.A.; Anhorn, C.; Eirich, R.; Christakis, D.A. Associations between screen use and child language skills: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, V.J.; Foehr, U.G.; Roberts, D.F. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-Year-Olds; Henry, J. Kaiser Family Foundation: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.kff.org/other/event/generation-m2-media-in-the-lives-of-8-to-18-year-olds/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Greenfield, P.M. Mind and Media: The Effects of Television, Video Games, and Computers; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Zosh, J.M.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Gray, J.H.; Robb, M.B.; Kaufman, J. Putting education in “educational” apps: Lessons from the science of learning. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linebarger, D.L.; Piotrowski, J.T. TV as storyteller: How exposure to television narratives impacts at-risk preschoolers’ story knowledge and narrative skills. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 27, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, F.J.; Christakis, D.A. Children’s television viewing and cognitive outcomes: A longitudinal analysis of national data. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, A.I.; Alade, F.; Sharp, M.L.; Rasmussen, E.E.; Christy, K. The relation between television exposure and executive function among preschoolers. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, L.M.; Stevens, R. The New Coviewing: Designing for Learning Through Joint Media Engagement; The Joan Ganz Cooney Center: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/publication/the-new-coviewing/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Vandewater, E.A.; Bickham, D.S.; Lee, J.H. Time well spent? Relating television use to children’s free-time activities. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e181–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhls, Y.T.; Michikyan, M.; Morris, J.; Garcia, D.; Small, G.W.; Zgourou, E.; Greenfield, P.M. Five days at outdoor education camp without screens improves preteen skills with nonverbal emotion cues. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrath, S.; O’Brien, E.H.; Hsing, C. Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: A meta-analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Resolution on Violent Video Games. 2015. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2015/08/violent-video-games (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- APA Stress in America. Stress in America™ 2017: Technology and Social Media. Available online: https://share.google/ERWf4yYOiUmcTCYzg (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Christakis, D.A. The effects of infant media usage: What do we know and what should we learn? Acta Paediatr. 2009, 98, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domoff, S.E.; Harrison, K.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Gentile, D.A.; Lumeng, J.C.; Miller, A.L. Development and Validation of the Problematic Media Use Measure: A Parent Report Measure of Screen Media “Addiction” in Children. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2019, 8, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odgers, C.L.; Jensen, M.R. Annual Research Review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age: Facts, fears, and future directions. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, K.; Reich, S.M.; Waechter, N.; Espinoza, G. Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Benefits of Physical Activity and Health. 2024. Available online: https://share.google/pdGsBrk6lSm8ymyY9 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Pearson, N.; Biddle, S.J. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Kho, M.E.; Saunders, T.J.; Larouche, R.; Colley, R.C.; Goldfield, G.; Gorber, S.C. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.M.; Aeschbach, D.; Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.A. Insufficient Sleep in Adolescents and Young Adults: An Update on Causes and Consequences. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e921–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, B.A.; Fricke, T.R.; Wilson, D.A.; Jong, M.; Naidoo, K.S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Wong, T.Y.; Naduvilath, T.; Resnikoff, S. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, F.J.; Christakis, D.A.; Meltzoff, A.N. Associations between media viewing and language development in children under age 2 years. J. Pediatr. 2007, 151, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linebarger, D.L.; Walker, D. Infants’ and toddlers’ television viewing and language outcomes. Am. Behav. Sci. 2005, 48, 624–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, S.B.; Dwyer, J. Developing vocabulary and conceptual knowledge for low-income preschoolers: A design experiment. J. Lit. Res. 2011, 43, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisleder, A.; Fernald, A. Talking to children matters: Early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewater, E.A.; Rideout, V.J.; Wartella, E.A.; Huang, X.; Lee, J.H.; Shim, M.S. Digital childhood: Electronic media and technology use among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e1006–e1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseberry, S.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M. Skype me! Socially contingent interactions help toddlers learn language. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, D.A. Interactive media use at younger than the age of 2 years: Time to rethink the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline? JAMA Pediatr. 2011, 165, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.S.; Saelens, B.E.; Christakis, D.A. Active play opportunities at child care. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e1425–e1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Piotrowski, J.T. Plugged in: How Media Attract and Affect Youth; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.S. Parental mediation theory for the digital age. Commun. Theory 2011, 21, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Sim, T.; Liau, A.K.F.; Gentile, D.A.; Khoo, A. Parental influences on pathological symptoms of video-gaming among children and adolescents: A prospective study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 24, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BBC News. China cuts children’s online gaming to one hour. BBC News, 30 August 2021. Available online: https://share.google/5uFjNuwIk3LjBul0E (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Greenfield, P.M. Technology and informal education: What is taught, what is learned. Science 2009, 323, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Dill, K.E. Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550536 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Raghavan, R.; Almas, Y.M.; Sheikh, M.; Alramah, A.K.; Kar, S.S.; Dube, R.; Goud, B.K.M. Effect of obesity on the Health and Quality of life in Late Adolescents. Rev. Educ. 2024, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).