Exploring Progesterone Deficiency in First-Trimester Miscarriage and the Impact of Hormone Therapy on Foetal Development: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

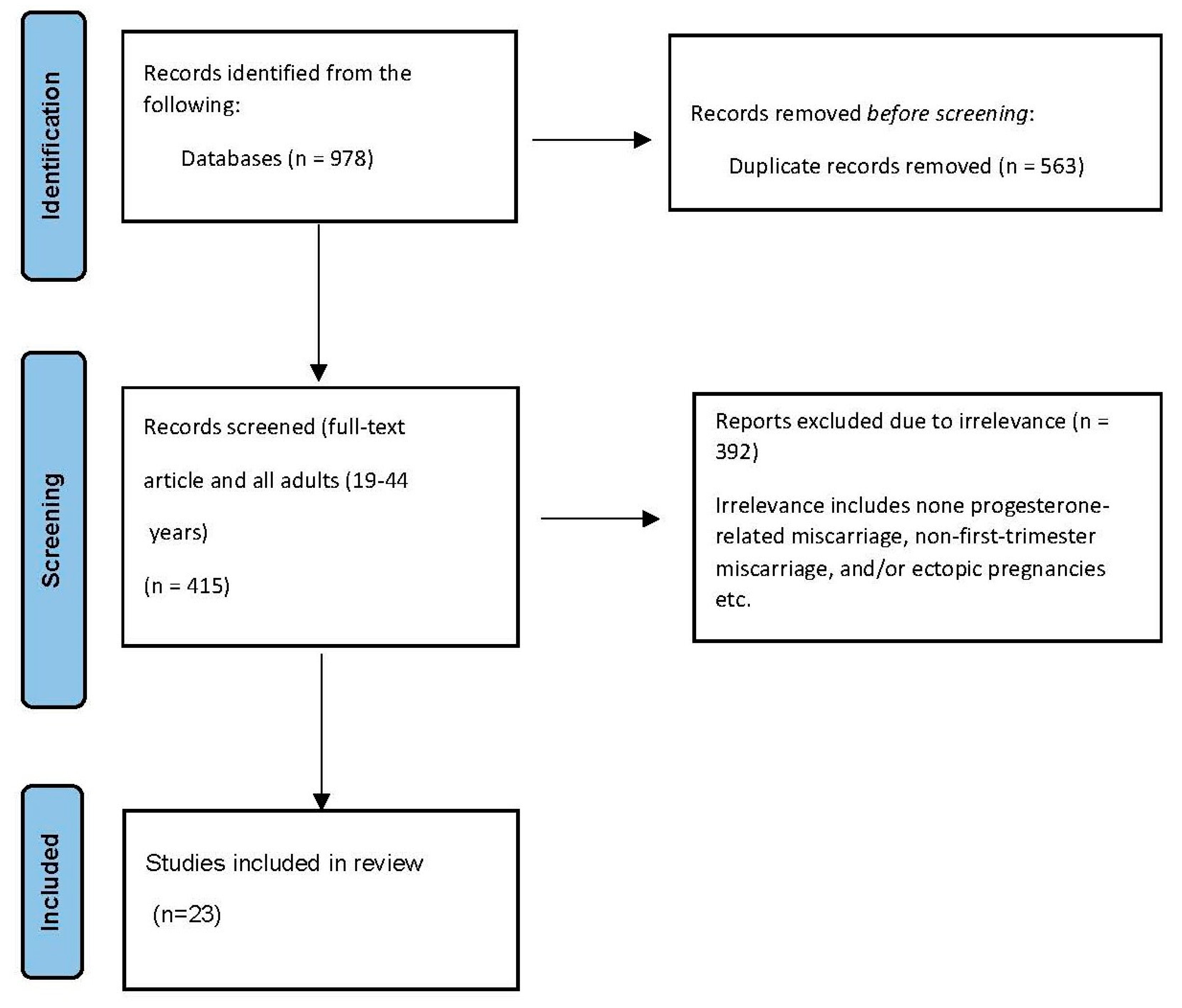

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Article Characteristics

3.2. The Association between Progesterone Level and Pregnancy Loss

3.3. Progesterone Level as a Predictor of Miscarriage

3.4. Progesterone Combined with Oestrogen or β-HCG or PIBF as Predictors of Miscarriage

3.5. Progestogen Therapy’s Effectiveness

3.6. The Impact of Progestogen Therapy on Foetal Development

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haas, D.M.; Hathaway, T.J.; Ramsey, P.S. Progestogen for preventing miscarriage in women with recurrent miscarriage of unclear etiology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD003511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Si, C.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; Luo, S.; Deng, G.; Gao, J. Microbiome Characteristics in Early Threatened Miscarriage Study (MCETMS): A study protocol for a prospective cohort investigation in China. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.W.; Allen, J.C., Jr.; Malhotra, R.; Chong, H.C.; Tan, N.S.; Ostbye, T.; Lek, S.M.; Lie, D.; Tan, T.C. How can we better predict the risk of spontaneous miscarriage among women experiencing threatened miscarriage? Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2015, 31, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why We Need to Talk about Losing a Baby. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/why-we-need-to-talk-about-losing-a-baby#:~:text=Many%20women%20who%20lose%20a,vary%20tremendously%20around%20the%20globe (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Quenby, S.; Gallos, I.D.; Dhillon-Smith, R.K.; Podesek, M.; Stephenson, M.D.; Fisher, J.; Brosens, J.J.; Brewin, J.; Ramhorst, R.; Lucas, E.S.; et al. Miscarriage matters: The epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet 2021, 397, 1658–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nynas, J.; Narang, P.; Kolikonda, M.K.; Lippmann, S. Depression and Anxiety Following Early Pregnancy Loss: Recommendations for Primary Care Providers. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015, 17, 26225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, D. Pregnancy loss: Consequences for mental health. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 1032212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.W.; Allen, J.C., Jr.; Lek, S.M.; Chia, M.L.; Tan, N.S.; Tan, T.C. Serum progesterone distribution in normal pregnancies compared to pregnancies complicated by threatened miscarriage from 5 to 13 weeks gestation: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Magon, N. Hormones in pregnancy. Niger. Med. J. 2012, 53, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Dante, G.; Vaccaro, V.; Facchinetti, F. Use of progestagens during early pregnancy. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn 2013, 5, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.T.; Lee, I.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Kuo, P.L. Association of progesterone receptor polymorphism with idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss in Taiwanese Han population. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2011, 28, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shah, D.; Nagarajan, N. Luteal insufficiency in first trimester. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Shin, J.H.; Hur, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Ku, S.Y.; Suh, C.S. Predictive value of serum progesterone level on beta-hCG check day in women with previous repeated miscarriages after in vitro fertilization. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181229. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.M.; Lai, P.F.; Imami, N.; Johnson, M.R. Progesterone-Related Immune Modulation of Pregnancy and Labor. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, H.; Li, B.; Liu, M.; Liu, D.; Deng, M.; Wang, Y.; Xia, X.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, D. Effects of human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone on interleukin-18 expression in human decidual tissues. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2017, 33, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetendorf, M.; DeMayo, F.J. The progesterone receptor regulates implantation, decidualization, and glandular development via a complex paracrine signaling network. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 357, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, M.; Rezaei, A.; Alipour, R.; Sereshki, N.; Motamedi, N.; Naseri, M. Progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF) influences the expression of membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs) on peripheral CD4(+) T lymphocyte cells in normal fertile females. Hormones 2021, 20, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekeres-Bartho, J. Progesterone induced blocking factor in health and disease. Explor. Immunol. 2021, 1, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, V.K.; Agrawal, S.; Saxena, P.; Laul, P. Predictive Value of Single Serum Progesterone Level for Viability in Threatened Miscarriage. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 2019, 69, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaegen, J.; Gallos, I.D.; van Mello, N.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.; Takwoingi, Y.; Harb, H.; Deeks, J.J.; Mol, B.W.; Coomarasamy, A. Accuracy of single progesterone test to predict early pregnancy outcome in women with pain or bleeding: Meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2012, 345, e6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.; Parker, D. Guidance for the Conduct of JBI Scoping Reviews; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI; 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, H.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Heise, T.L.; Stratil, J.M.; Lhachimi, S.K.; Hemkens, L.G.; Gartlehner, G.; Armijo-Olivo, S.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B. Searching two or more databases decreased the risk of missing relevant studies: A metaresearch study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 149, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Coomarasamy, A.; Harb, H.M.; Devall, A.J.; Cheed, V.; Roberts, T.E.; Goranitis, I.; Ogwulu, C.B.; Williams, H.M.; Gallos, I.D.; Eapen, A.; et al. Progesterone to prevent miscarriage in women with early pregnancy bleeding: The PRISM RCT. Health Technol. Assess. 2020, 24, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Sun, R.; Du, J.; Wu, X.; Ma, L.; Wang, M.; Lv, Q. Prediction of miscarriage in first trimester by serum estradiol, progesterone and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin within 9 weeks of gestation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devall, A.J.; Papadopoulou, A.; Podesek, M.; Haas, D.M.; Price, M.J.; Coomarasamy, A.; Gallos, I.D. Progestogens for preventing miscarriage: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 4, CD013792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Yan, D.; Zeng, W.; Yang, X.; Wei, Q. Predictive power progesterone combined with beta human chorionic gonadotropin measurements in the outcome of threatened miscarriage. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanita, O.; Hanisah, A.H. Potential use of single measurement of serum progesterone in detecting early pregnancy failure. Malays. J. Pathol. 2012, 34, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, C.W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, V.R.; Allen, J.C.; Tan, N.S.; Ostbye, T.; Tan, T.C. Gestational age-specific normative values and determinants of serum progesterone through the first trimester of pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lek, S.M.; Ku, C.W.; Allen, J.C., Jr.; Malhotra, R.; Tan, N.S.; Ostbye, T.; Tan, T.C. Validation of serum progesterone <35nmol/L as a predictor of miscarriage among women with threatened miscarriage. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.C.; Ku, C.W.; Kwek, L.K.; Lee, K.W.; Zhang, X.; Allen, J.C., Jr.; Zhang, V.R.; Tan, N.S. Novel approach using serum progesterone as a triage to guide management of patients with threatened miscarriage: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgal, M.; Aydin, E.; Ozyuncu, O. Effect of micronized progesterone on fetal-placental volume in first-trimester threatened abortion. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2017, 45, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahabi, H.A.; Fayed, A.A.; Esmaeil, S.A.; Bahkali, K.H. Progestogen for treating threatened miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD005943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, P.G.; Schreiber, C.A.; Sammel, M.D. Gestational hormone trajectories and early pregnancy failure: A reassessment. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zou, M.; Cheng, G.; Yuan, Z. Efficacy of progesterone on threatened miscarriage: An updated meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLindon, L.A.; James, G.; Beckmann, M.M.; Bertolone, J.; Mahomed, K.; Vane, M.; Baker, T.; Gleed, M.; Grey, S.; Tettamanzi, L.; et al. Progesterone for women with threatened miscarriage (STOP trial): A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, S.; Lin, X.; He, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, P. Pregnancy-related complications and perinatal outcomes following progesterone supplementation before 20 weeks of pregnancy in spontaneously achieved singleton pregnancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedel, C.; Larsen, H.; Holmskov, A.; Andreasen, K.R.; Uldbjerg, N.; Ramb, J.; Bodker, B.; Skibsted, L.; Sperling, L.; Krebs, L.; et al. Long-term effects of prenatal progesterone exposure: Neurophysiological development and hospital admissions in twins up to 8 years of age. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Lu, J.; He, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, N.; Yuan, M.; Xiao, W.; Qiu, L.; Hu, C.; Xia, H.; et al. Progesterone use in early pregnancy: A prospective birth cohort study in China. Lancet 2015, 386, S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, N.E.; Leeuw, M.; Van’t Hooft, J.; Limpens, J.; Roseboom, T.J.; Oudijk, M.A.; Pajkrt, E.; Finken, M.; Painter, R.C. The long-term effect of prenatal progesterone treatment on child development, behaviour and health: A systematic review. BJOG 2021, 128, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, W.C. Did the NICE guideline for progesterone treatment of threatened miscarriage get it right? Reprod. Fertil. 2022, 3, C4–C6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, and Country of Investigation | Study Title | Aim/Purpose | Population& Sample Size | Study Type | Results | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coomarasamy et al., 2020. UK. [26] | Progesterone to prevent miscarriage in women with early pregnancy bleeding: the PRISM RCT. | To assess the effects of vaginal micronised progesterone in women with vaginal bleeding in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. | 4153 participants. | A multicentre RCT | The live birth rate was 75% in the progesterone group and 72% in the placebo group. | Progesterone therapy given in the first trimester of pregnancy did not result in a significantly higher rate of live births among women with TM. |

| Deng et al., 2022. China. [27] | Prediction of miscarriage in first trimester by serum estradiol, progesterone and β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) within 9 weeks of gestation. | To predict a miscarriage outcome within 12 weeks of gestational age by evaluating values of serum oestradiol, progesterone and β-HCG. | 165 participants. | Retrospective study. | Progesterone levels at 7–9 weeks had an AUC of 0.766 (95% CI 0. 672–0.861), p = 0.000). | Low serum levels of oestradiol and progesterone or oestradiol alone at 7–9 weeks and β-HCG or combined progesterone and oestradiol at 5–6 weeks of gestation can be used better to predict first-trimester-miscarriage. |

| Devall et al., 2021. Australia, Germany, Hong Kong, the UK, and Singapore. [28] | Progestogens for preventing miscarriage: a network meta-analysis. | To estimate the relative effectiveness and safety profiles of the different progestogen treatments. | 7 randomised trials (involving 5682 women). | A network meta-analysis. | Vaginal micronised progesterone may make little or no difference to the live birth rate when compared with a placebo in women with TM. | Progestogen may have a slight or no difference in threatened or recurrent miscarriage. However, vaginal micronised progesterone may increase the live birth rate. |

| Duan et al., 2010. China. [29] | Predictive power of progesterone combined with β-HCG measurements in the outcome of threatened miscarriage. | To investigate the predictive power of progesterone in combination with β-HCG measurements in the outcome of TM. | 175 participants. | Retrospective study. | The mean serum levels of progesterone and β-HCG in patients with inevitable miscarriages were significantly lower than those in normal intrauterine pregnancies and ongoing pregnancies. | Progesterone combined with β-CG measurements may be useful for predicting the outcome of TM. |

| Haas et al., 2019. India, Jordan, the UK, and the USA. [1] | Progestogen for preventing miscarriage in women with recurrent miscarriage of unclear etiology. | To assess the efficacy and safety of progestogen as a preventative therapy against recurrent miscarriage. | Twelve trials (1856 participants). | A meta-analysis. | There may be a reduction in the number of miscarriages in women who are given progestogen supplementation compared to a placebo/controls. | For women with unexplained recurrent miscarriages, supplementation with progestogen therapy may reduce the rate of miscarriage in subsequent pregnancies. |

| Hanita and Hanisah, 2012. Malaysia. [30] | Potential use of single measurement of serum progesterone in detecting early pregnancy failure. | To determine the role of progesterone as a marker of early pregnancy failure. | 95 participants. | A cross sectional study. | Progesterone levels were significantly lower in threatened abortion patients with outcomes of nonviable pregnancy compared with pregnancies that progressed on to the viability period. | Serum progesterone can be used as a marker for early pregnancy failure. |

| Kim et al., 2017. South Korea. [13] | Predictive value of serum progesterone level on β-HCG check day in women with previous repeated miscarriages after in vitro fertilization. | To assess the predictive value of the progesterone level on the β-HCG check day for ongoing pregnancy maintenance in in vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycles in women with previous unexplained repeated miscarriages. | 148 participants. | Prospective observational study. | The overall ongoing pregnancy rate was 60.8%. The cut-off values of β-HCG levels higher than 126.5 mIU/mL and of progesterone levels higher than 25.2 ng/mL could be the predictive factors for ongoing pregnancy maintenance. The miscarriage rates were 19.5% (15/77) in the women with β-HCG > 126.5 mIU/mL and 13.0% (10/77) in those with >25.2 ng/mL. | The progesterone level at 14 days after oocyte retrieval can be a good predictive marker for ongoing pregnancy maintenance in women with repeated IVF failure with miscarriage, together with the β-HCG level. The combined cut-off value of progesterone > 25.2 ng/mL and β-HCG > 126.5 mIU/mL may suggest a good prognosis. |

| Ku et al., 2015. Singapore. [3] | How can we better predict the risk of spontaneous miscarriage among women experiencing threatened miscarriage? | To establish progesterone and PIBF levels as predictors of subsequent completed miscarriage among women presenting with TM between 6 and 10 weeks of gestation. | 119 participants. | Prospective cohort study. | Low progesterone and PIBF levels are similarly predictive of subsequent completed miscarriage. Higher levels of progesterone and PIBF are linked to a lower risk of miscarriage, while low serum progesterone and PIBF levels predict spontaneous miscarriage among TM women between weeks 6 and 10. | Low progesterone and PIBF levels are predictive of subsequent completed miscarriage. Low serum progesterone and PIBF levels predict spontaneous miscarriage among women with TM between weeks 6 and 10. |

| Ku et al., 2018. Singapore. [8] | Serum progesterone distribution in normal pregnancies compared to pregnancies complicated by threatened miscarriage from 5 to 13 weeks gestation: a prospective cohort study. | To determine the distribution of maternal serum progesterone in normal pregnancies compared to those complicated by TM from 5 to 13 weeks’ gestation. | 929 participants. | Prospective cohort study. | Median progesterone levels were lower in the TM cohort. In the subgroup analysis, the median serum progesterone concentration in women with ongoing pregnancy showed a linearly elevating trend from 5 to 13 weeks’ gestation. There was a non-significant elevation in serum progesterone from 5 to 13 weeks’ gestation in women who eventually had a spontaneous miscarriage. | Progesterone has a role in supporting early pregnancy, with lower serum progesterone being associated with TM and a subsequent complete miscarriage at 16 weeks’ gestation. |

| Ku et al., 2021. Singapore. [31] | Gestational age-specific normative values and determinants of serum progesterone through the first trimester of pregnancy. | To determine the gestational age-specific normative values of serum progesterone on a weekly basis, and its associated maternal and foetal factors, during the first trimester of a low-risk pregnancy. | 590 participants. | A cross-sectional study. | There was an elevated level of serum progesterone during the first trimester and a transient decrease between gestational weeks 6 to 8. In women who had miscarried by 16 weeks, serum progesterone levels were significantly lower compared to women with viable pregnancies at 16 weeks for a mean difference of 24.2nmol/L. | Maternal age, BMI, parity, gestational age, and outcome of pregnancy at 16 weeks’ gestation may be linked to serum progesterone level. |

| Lek et al., 2017. Singapore. [32] | Validation of serum progesterone < 35 nmol/L as a predictor of miscarriage among women with threatened miscarriage. | To evaluate the validity of serum progesterone < 35 nmol/L with the outcome of spontaneous miscarriage by 16 weeks. | 360 participants. | A prospective cohort study. | The study showed that the serum progesterone cut-off value of <35 nmol/L (11 ng/mL) is a useful predictor of miscarriage prior to week 16 of pregnancy. | As the serum progesterone cut-off value of <35 nmol/L (11 ng/mL) is a useful predictor of miscarriage prior to week 16 of pregnancy, patients can be quickly stratified as being at low or high risk of spontaneous miscarriage. |

| Tan et al., 2020. Singapore. [33] | Novel approach using serum progesterone as a triage to guide management of patients with threatened miscarriage: a prospective cohort study. | To assess the safety and efficacy of a clinical protocol using a certain serum progesterone level to prognosticate and guide the management of patients with TM. | 1087 participants. | A prospective cohort study. | The miscarriage rate was 9.6% among 77.9% of participants with serum progesterone ≥ 35 nmol/L who were not treated with oral dydrogesterone. The miscarriage rate was 70.8% among women with serum progesterone < 35 nmol/L who were treated with dydrogesterone. | Patients with high serum progesterone levels can be reassured and counselled without medical treatment, while patients with low serum progesterone levels are at high risk of miscarriage even with treatment. |

| Turgal et al., 2016. Turkey. [34] | Effect of micronized progesterone on foetal-placental volume in first trimester threatened abortion. | To compare the effect of oral micronised progesterone on first-trimester foetal and placental volumes. | 60 participants. | Randomised controlled trial. | After treatment, the placental volume difference was significantly higher in the oral micronised progesterone group (336%, 67–1077) than in the control group (141%, 29–900) (p = 0.007). | Hormonal support with oral micronised progesterone is associated with an elevated placental volume in first-trimester threatened abortion when compared to the control group. |

| Wahabi et al., 2018. Germany, Italy, Iran, Malaysia, Turkey, and Jordan. [35] | Progestogen for treating threatened miscarriages. | To determine the safety and efficacy of progestogens in the treatment of TM. | Seven trials (involving 696 participants). | Meta-analysis. | Treatment with oral progestogens decreases the miscarriage rate. Treatment with vaginal progesterone has little or no effect. | Progestogens may be effective in the treatment of TM. However, they may have little or no effect on the rate of preterm birth. |

| Wang et al., 2017. China. [15] | Effects of HCG, estradiol, and progesterone on IL-18 expression in human decidual tissues. | To evaluate the effects of oestradiol, HCG, and progesterone on IL-18 expression in human decidual tissues. | 28 participants. | Prospective cohort study. | Oestradiol, HCG, and progesterone can reduce IL-18 secretion in the cultured endometrial stromal cells in patients with spontaneous abortion to the levels observed following normal pregnancy. | Progesterone can significantly decrease IL-18 expression and elevate the growth of CD56+ CD16− uNK cells. Therefore, it is suggested that these activities may underlie the mechanism by which progesterone enhances pregnancy outcomes. |

| Whittaker et al., 2018. The UK. [36] | Gestational hormone trajectories and early pregnancy failure: a reassessment. | To re-evaluate whether, in early pregnancy, gestational hormone trajectories can determine future miscarriage in asymptomatic pregnancies. | 210 participants. | Prospective cohort study. | Progesterone and oestradiol displayed negative mean slopes in pregnancies destined for failure; in this group, both human placental lactogen (hPL) and HCG revealed mean positive trajectories that imitated normal pregnancies. | Oestradiol, progesterone, and HCG trajectories, from 50 days of gestation, have good potential for revealing pathophysiology and for identifying which asymptomatic pregnancies are destined for subsequent failure. |

| Yan et al., 2021. Taiwan. [37] | Efficacy of progesterone on threatened miscarriage: an updated meta-analysis of randomized trials. | To investigate the correlation between progesterone and improving pregnancy outcomes among those with TM. | 4907 participants. | Meta-analysis. | Compared to the placebo, progesterone supplementation was associated with a decrease in the rate of miscarriage [RR = 0.70 95% Cl (0.52, 0.94)]. | Progesterone supplementation did not significantly enhance the incidence of preterm and live birth. |

| Su et al., 2011. Taiwan. [11] | Association of progesterone receptor polymorphism with idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss in the Taiwanese Han population. | To investigate the association between polymorphisms of the progesterone receptor gene and idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss. | 300 participants. | Prospective cohort study. | The allele and genotype frequencies of the functional SNP [PROGINS (rs1042838)] were both significantly higher in patients with idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss than in the control subjects (both p = 0.006). In addition, the C-C haplotype, which consists of rs590688C>G and rs11224592T>C, is associated with a decreased risk of recurrent pregnancy loss (p = 0.004). | The PROGINS polymorphism confers susceptibility to idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss in Taiwanese Han women. |

| Mclindon et al., 2023. Australia. [38] | Progesterone for women with threatened miscarriage (STOP trial): a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. | To determine the treatment effect of vaginal progesterone in women with TM. | 556 participants. | A placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial. | The live birth rates were 82.4% and 84.2% in the intervention group and placebo group, respectively. Among women with at least one previous miscarriage, the live birth rates were 80.6% and 84.4%. Also, no significant effect was seen from progesterone in women with two or more previous miscarriages. The preterm birth rates were 12.9% and 9.3%, respectively. | No evidence to support the treatment effect of vaginal progesterone in women with TM. |

| Wu et al., 2021. China. [39] | Pregnancy-related complications and perinatal outcomes following progesterone supplementation before 20 weeks of pregnancy in spontaneously achieved singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. | To assess the effects of progesterone supplementation before 20 weeks of pregnancy on pregnancy-related complications and perinatal outcomes in later gestational weeks. | Nine trials (involving 6439 participants). | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials. | The pooled odds ratio (OR) of low birth weight following oral dydrogesterone was 0.57 (95% CI 0.34–0.95, moderate quality of evidence). | The use of oral dydrogesterone in those with history of recurrent miscarriage, before 20 weeks of pregnancy, may decrease the risk of low birth weight in later gestational weeks. |

| Vedel et al., 2016. Denmark. [40] | Long-term effects of prenatal progesterone exposure: neurophysiological development and hospital admissions in twins up to 8 years of age. | To perform a neurophysiological follow-up in children exposed prenatally to progesterone at 48 or 60 months of age. | 989 participants. | Placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial. | There was no difference in the number of admissions to hospital or rates of diagnoses between the groups. However, the ORs for a diagnosis concerning the heart were 1.66 (95% CI, 0.81–3.37), favouring the placebo. | Second- and third-trimester exposure of the foetus to progesterone may not cause long-term harmful effects. |

| Shen et al., 2015. China. [41] | Progesterone use in early pregnancy: a prospective birth cohort study in China. | To determine the effects of progesterone use in early pregnancy on birth and maternal outcomes. | 6617 participants. | A prospective cohort study. | Women who used progesterone had significantly higher risks of caesarean section and post-partum depression. Progesterone use had no effect on preterm-birth prevention, foetal growth, or gestational diabetes. | Progesterone use in early pregnancy has no benefit or harm for specific pregnancy outcomes. |

| Simons et al., 2021. The Netherlands. [42] | The long-term effect of prenatal progesterone treatment on child development, behaviour and health: a systematic review. | To determine long-term effects in children after prenatal progesterone treatment. | 388 papers, (involving 4222 participants). | Systematic review. | There was no difference in neurodevelopment as assessed by the Bayley-III Cognitive Composite score between those exposed to progesterone versus placebo. Other outcomes showed no differences. | There was no evidence of benefit or harm in offspring prenatally exposed to progesterone treatment for the prevention of preterm birth. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bataa, M.; Abdelmessih, E.; Hanna, F. Exploring Progesterone Deficiency in First-Trimester Miscarriage and the Impact of Hormone Therapy on Foetal Development: A Scoping Review. Children 2024, 11, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040422

Bataa M, Abdelmessih E, Hanna F. Exploring Progesterone Deficiency in First-Trimester Miscarriage and the Impact of Hormone Therapy on Foetal Development: A Scoping Review. Children. 2024; 11(4):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040422

Chicago/Turabian StyleBataa, Munkhtuya, Erini Abdelmessih, and Fahad Hanna. 2024. "Exploring Progesterone Deficiency in First-Trimester Miscarriage and the Impact of Hormone Therapy on Foetal Development: A Scoping Review" Children 11, no. 4: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040422

APA StyleBataa, M., Abdelmessih, E., & Hanna, F. (2024). Exploring Progesterone Deficiency in First-Trimester Miscarriage and the Impact of Hormone Therapy on Foetal Development: A Scoping Review. Children, 11(4), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040422