Genetic Engineering of Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Enhance BMP-2 Secretion via Signal Peptide Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Isolation and Culture of MSCs

2.3. Plasmid Transfections

2.4. Analysis of the GFP Positive Signal

2.4.1. GFP Qualitative Analysis Using Fluorescence Microscopy

2.4.2. GFP Quantitative Analysis Using Flow Cytometry

2.5. BMP-2 Gene Expression

2.6. Isolation and BMP-2 Protein Quantification of Secretome from Engineered MSCs

2.7. Characterization Post-Transfection

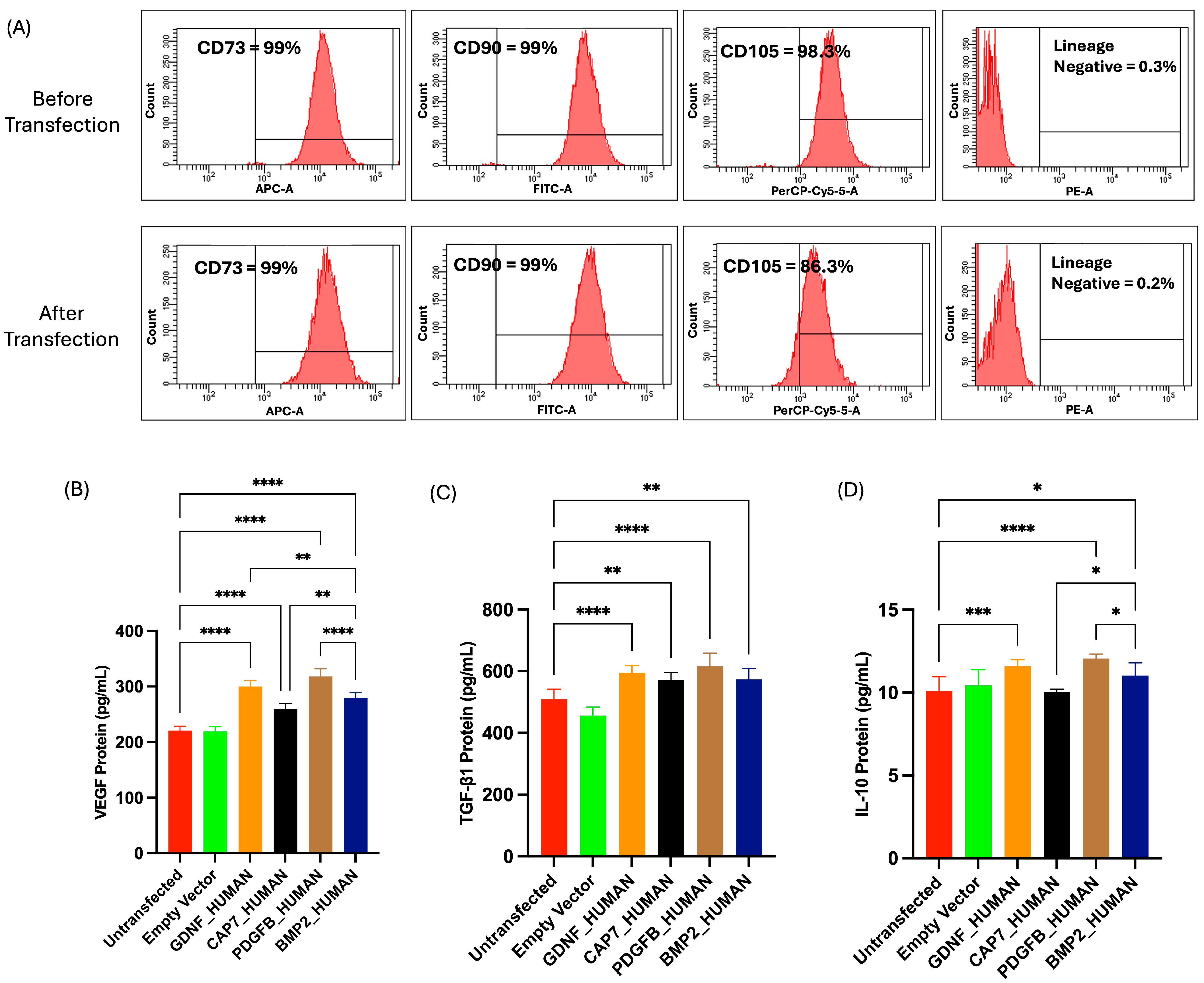

2.7.1. Phenotypic Profile of UC-MSCs Post-Transfection

2.7.2. Secretome Profile of UC-MSC Post-Transfection

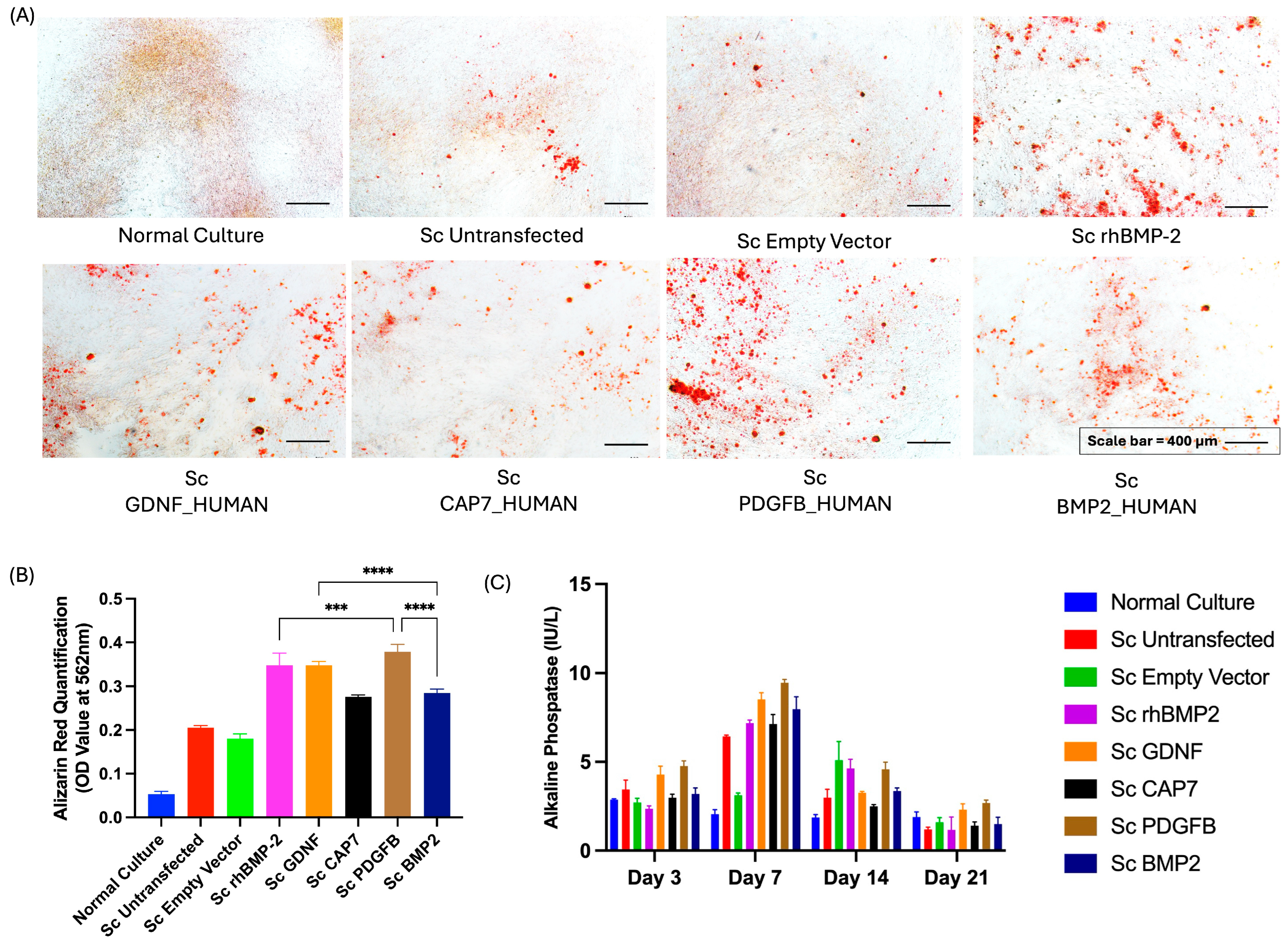

2.8. Osteogenic Differentiation

2.9. Alizarin Red Staining

2.10. ALP Activity

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of UC-MSC Transfection Efficiency Using Different Transfection Reagents

3.2. Evaluation of Transfection Efficiency, Cell Viability, and BMP-2 Secretion in UC-MSCs Transfected with Different Signal Peptide Constructs

3.3. Phenotypic Profile and Secretome Profile of UC-MSCs Post-Transfection

3.4. Effect of the Secretome Derived from Transfected UC-MSCs on the Osteogenic Differentiation of Non-Transfected UC-jMSCs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| APC | Allophycocyanin |

| BMP-2 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 |

| CAP7 | Chemotactic Antibacterial Glycoprotein 7 |

| CHO | Chinese Hamster Ovary |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FITC | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

| FSC-A | Forward Scatter Area |

| GDNF | Glial-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Human |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| HEK293 | Human Embryonic Kidney 293 |

| HLA-DR | Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR isotype |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| LB | Luria–Bertani |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| PDGFB | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Subunit B |

| PE | Phycoerythrin |

| PEI | Polyethyleneimine |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| rhBMP-2 | Recombinant Human BMP-2 |

| RUNX2 | Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2 |

| Sc | Secretome |

| SP | Signal Peptide |

| SPFFV | Spleen Focus Forming Virus |

| SSC-A | Side Scatter Area |

| SRP | Signal Recognition Particle |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor-beta 1 |

| UC-MSCs | Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Candi, E.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. The secretion profile of mesenchymal stem cells and potential applications in treating human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, A.; García-Sánchez, D.; Dotta, M.; Rodríguez-Rey, J.C.; Pérez-Campo, F.M. Mesenchymal stem cells secretome: The cornerstone of cell-free regenerative medicine. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1529–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, K.; Kumar, P.; Choonara, Y.E. The paradigm of stem cell secretome in tissue repair and regeneration: Present and future perspectives. Wound Repair Regen. 2025, 33, e13251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Mu, W. BMP-2 promotes fracture healing by facilitating osteoblast differentiation and bone defect osteogenesis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 6751–6759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Che, Z.; Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Huang, L. Application of BMP in Bone Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 810880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, E.; Potier, E.; Vaudin, P.; Oudina, K.; Bensidhoum, M.; Logeart-Avramoglou, D.; Mir, L.M.; Petite, H. Sustained and promoter dependent bone morphogenetic protein expression by rat mesenchymal stem cells after BMP-2 transgene electrotransfer. Eur. Cell Mater. 2012, 24, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysdahl, H.; Baatrup, A.; Foldager, C.B.; Bünger, C. Preconditioning Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells with a Low Concentration of BMP2 Stimulates Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation In Vitro. BioRes. Open Access 2014, 3, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilogo, I.H.; Fiolin, J.; Canintika, A.F.; Pawitan, J.A.; Luviah, E. The Effect of Secretome, Xenogenic Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2, Hydroxyapatite Granule and Mechanical Fixation in Critical-Size Defects of Rat Models. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2022, 10, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halloran, D.; Durbano, H.W.; Nohe, A. Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 in Development and Bone Homeostasis. J. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, S.L.; Wu, X.; Maceren, J.P.; Mao, Y.; Kohn, J. In Vitro Evaluation of Recombinant Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Bioactivity for Regenerative Medicine. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2019, 25, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawitan, J.A.; Bui, T.A.; Mubarok, W.; Antarianto, R.D.; Nurhayati, R.W.; Dilogo, I.H.; Oceandy, D. Enhancement of the Therapeutic Capacity of Mesenchymal Stem Cells by Genetic Modification: A Systematic Review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 587776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, P.; Mistry, R.K.; Brown, A.J.; James, D.C. Protein-Specific Signal Peptides for Mammalian Vector Engineering. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 2339–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, S.; Patrucco, L.; Persichetti, F.; Gustincich, S.; Cotella, D. Engineering Translation in Mammalian Cell Factories to Increase Protein Yield: The Unexpected Use of Long Non-Coding SINEUP RNAs. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler-Gane, G.; Kidd, S.; Sridharan, S.; Vaughan, T.J.; Wilkinson, T.C.; Tigue, N.J. Overcoming the Refractory Expression of Secreted Recombinant Proteins in Mammalian Cells through Modification of the Signal Peptide and Adjacent Amino Acids. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.W.; Wang, F.; Lopez, G.A.; Singamsetty, S.; Wood, J.; Dickson, P.I.; Chou, T.F. Evaluation of artificial signal peptides for secretion of two lysosomal enzymes in CHO cells. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 2309–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owji, H.; Nezafat, N.; Negahdaripour, M.; Hajiebrahimi, A.; Ghasemi, Y. A comprehensive review of signal peptides: Structure, roles, and applications. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 97, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, S.M.; Deineko, E.V. Increasing the Efficiency of the Accumulation of Recombinant Proteins in Plant Cells: The Role of Transport Signal Peptides. Plants 2022, 11, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Stutz, R.; Schorr, S.; Lang, S.; Pfeffer, S.; Freeze, H.H.; Förster, F.; Helms, V.; Dudek, J.; Zimmermann, R. Proteomics reveals signal peptide features determining the client specificity in human TRAP-dependent ER protein import. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, X.; Mariappan, M. Signal sequences encode information for protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202203070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamyshev, A.L.; Tikhonova, E.B.; Karamysheva, Z.N. Translational Control of Secretory Proteins in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawitan, J.A.; Kispa, T.; Mediana, D.; Goei, N.; Fasha, I.; Liem, I.K.; Wulandari, D. Simple production method of umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cell using xeno-free materials for translational research. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 652–656. [Google Scholar]

- Mazfufah, N.F.; Nurhayati, R.W.; Dilogo, I.H.H.; Mubarok, W. Signal peptides for optimization of recombinant protein secretion: An innovation to produce bone morphogenetic protein-2 in mesenchymal stem cells. Bali Med. J. 2024, 13, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, C.; Mendes, R.D.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Boura, J.S.; Aires-Barros, M.R.; da Silva, C.L.; Cabral, J.M. Nonviral gene delivery to mesenchymal stem cells using cationic liposomes for gene and cell therapy. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 735349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Z.X.; Yeap, S.K.; Ho, W.Y. Transfection types, methods and strategies: A technical review. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunert, R.; Vorauer-Uhl, K. Strategies for efficient transfection of CHO-cells with plasmid DNA. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 801, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, T.G.; Pellenz, F.M.; Laureano, A.; da Rocha Silla, L.M.; Giugliani, R.; Baldo, G.; Matte, U. A simple protocol for transfecting human mesenchymal stem cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 40, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; He, Y.; Xiong, W.; Jing, S.; Duan, X.; Huang, Z.; Nahal, G.S.; Peng, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y.; et al. MSC based gene delivery methods and strategies improve the therapeutic efficacy of neurological diseases. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 23, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, S.; Li, C. Comparison of different kinds of nonviral vectors for gene delivery to human periodontal ligament stem cells. J. Dent. Sci. 2015, 10, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozisek, T.; Samuelson, L.; Hamann, A.; Pannier, A.K. Systematic comparison of nonviral gene delivery strategies for efficient co-expression of two transgenes in human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Biol. Eng. 2023, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Cho, H.B.; Takimoto, K. Effective gene delivery into adipose-derived stem cells: Transfection of cells in suspension with the use of a nuclear localization signal peptide-conjugated polyethylenimine. Cytotherapy 2015, 17, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, A.D.; Gialeli, C.; Bouris, P.; Giannopoulou, E.; Skandalis, S.S.; Aletras, A.J.; Iozzo, R.V.; Karamanos, N.K. Cell-matrix interactions: Focus on proteoglycan-proteinase interplay and pharmacological targeting in cancer. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 5023–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, W.Y.; Hovey, O.; Gobin, J.M.; Muradia, G.; Mehic, J.; Westwood, C.; Lavoie, J.R. Efficient Nonviral Transfection of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Shown Using Placental Growth Factor Overexpression. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1310904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, A.; Krott, N.; Breibach, I.; Blindt, R.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Efficient transfection method for primary cells. Tissue Eng. 2002, 8, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Xue, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, X.; Li, X. An improved method for increasing the efficiency of gene transfection and transduction. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 10, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, P.; Mobarakeh, V.I.; Kamalzare, S.; SajadianFard, F.; Vahabpour, R.; Zabihollahi, R. Comparison of transfection efficiency of polymer-based and lipid-based transfection reagents. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2018, 119, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Larcher, L.M.; Ma, L.; Veedu, R.N. Systematic Screening of Commonly Used Commercial Transfection Reagents towards Efficient Transfection of Single-Stranded Oligonucleotides. Molecules 2018, 23, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, D.; Caracciolo, G. Looking Back, Moving Forward: Lipid Nanoparticles as a Promising Frontier in Gene Delivery. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, S.; Arya, G.; Chandra, R.; Ahmed, B.; Nimesh, S. Effect of size on biological properties of nanoparticles employed in gene delivery. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, C.; Etcheverrigaray, M.; Kratje, R.; Oggero, M. A highly efficient modified human serum albumin signal peptide to secrete proteins in cells derived from different mammalian species. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 132, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, L.; Zehe, C.; Bode, J. Optimized signal peptides for the development of high expressing CHO cell lines. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Oh, B.M.; Kim, J.T.; Lim, J.; Park, S.Y.; Hwang, Y.S.; Baek, K.E.; Kim, B.Y.; Choi, I.; Lee, H.G. Efficient Interleukin-21 Production by Optimization of Codon and Signal Peptide in Chinese Hamster Ovarian Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M.J.; Wilkinson, C.; Hiles, I.; Smith, K.J. Improved secretion of recombinant human IL-25 in HEK293 cells using a signal peptide-pro-peptide domain derived from Trypsin-1. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilogo, I.H.; Pawitan, J.A.; Tobing, J.F.L.; Fiolin, J.; Luviah, E. Amount of bone morphogenetic protein-2, epidermal growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor in adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell–derived secretome: An in vitro study. J. Stem Cells 2017, 12, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S.; Wei, H.; Elling, C.; He, B.; Stice, S. Overexpression of BMP-2 in mesenchymal stem cells with amplifying virus-like particles. Int. J. Regen. Med. 2018, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi Tabar, M.; Hesaraki, M.; Esfandiari, F.; Sahraneshin Samani, F.; Vakilian, H.; Baharvand, H. Evaluating Electroporation and Lipofectamine Approaches for Transient and Stable Transgene Expressions in Human Fibroblasts and Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell J. 2015, 17, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszer-Kierzkowska, A.; Vydra, N.; Wysocka-Wycisk, A.; Kronekova, Z.; Jarząb, M.; Lisowska, K.M.; Krawczyk, Z. Liposome-based DNA carriers may induce cellular stress response and change gene expression pattern in transfected cells. BMC Mol. Biol. 2011, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavado-García, J.; Pérez-Rubio, P.; Cervera, L.; Gòdia, F. The cell density effect in animal cell-based bioprocessing: Questions, insights and perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 60, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Kawazoe, N.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G. Influence of Cell Spreading Area on the Osteogenic Commitment and Phenotype Maintenance of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, L.H.; Vu, N.B.; Pham, P.V. The subpopulation of CD105 negative mesenchymal stem cells show strong immunomodulation capacity compared to CD105 positive mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2019, 6, 3131–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Carrillo-Gálvez, A.B.; García-Pérez, A.; Cobo, M.; Martín, F. CD105 (endoglin)-negative murine mesenchymal stromal cells define a new multipotent subpopulation with distinct differentiation and immunomodulatory capacities. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Olsen, B.R. Osteoblast-derived VEGF regulates osteoblast differentiation and bone formation during bone repair. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wu, X.; Lei, W.; Pang, L.; Wan, C.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, L.; Nagy, T.R.; Peng, X.; Hu, J.; et al. TGF-beta1-induced migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells couples bone resorption with formation. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallés, G.; Bensiamar, F.; Maestro-Paramio, L.; García-Rey, E.; Vilaboa, N.; Saldaña, L. Influence of inflammatory conditions provided by macrophages on osteogenic ability of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.P. The roles and regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β and BMP signaling in bone and cartilage development, homeostasis and disease. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langenfeld, E.M.; Langenfeld, J. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates angiogenesis in developing tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2004, 2, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, J.; Figueiredo, A.; Tseng, Y.H.; Carvalho, E.; Leal, E.C. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 7 Improves Wound Healing in Diabetes by Decreasing Inflammation and Promoting M2 Macrophage Polarization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, J.; Li, D.; Hao, L.; Li, Y.; Yi, D.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Chen, D.; Lu, W.W.; Pan, H.; et al. Engineering stem cells to produce exosomes with enhanced bone regeneration effects: An alternative strategy for gene therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenbach, F.; Handschel, J. Effects of dexamethasone, ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate on the osteogenic differentiation of stem cells in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigas, N.; Ureña, C.; Rodríguez-Carballo, E.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-regulated interactions between Osterix and Runx2 are critical for the transcriptional osteogenic program. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 27105–27117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, W.N.; Ali, A.M.; Subramani, T.; Mohamed Alitheen, N.B.; Hamid, M.; Samsudin, A.R.; Yeap, S.K. Rapid growth and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from human bone marrow. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 9, 2202–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.C.; Larrouture, Q.C.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Beer-Stoltz, D.; Liu, L.; Tuan, R.S.; Robinson, L.J.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Nelson, D.J. Osteoblast Differentiation and Bone Matrix Formation In Vivo and In Vitro. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2017, 23, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murshed, M. Mechanism of Bone Mineralization. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a031229, Erratum in Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a040667. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a040667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Signal Peptide | Amino Acid Sequence | Length | Origin Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDNF_HUMAN | MKLWDVVAVCLVLLHTASA | 19 | Homo sapiens |

| CAP7_HUMAN | MTRLTVLALLAGLLASSRA | 19 | Homo sapiens |

| PDGFB_HUMAN | MNRCWALFLSLCCYLRLVSA | 20 | Homo sapiens |

| BMP2_HUMAN | MVAGTRCLLALLLPQVLLGGAAG | 23 | Homo sapiens |

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| BMP-2 (NM_001200.4) | F: GAGAAGGAGGAGGCAAAGAAA R: GAAGCTCTGCTGAGGTGATAAA |

| GAPDH (NM_001256799.3) | F: CAATGACCCCTTCATTGACC R: TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mazfufah, N.F.; Dilogo, I.H.; Nurhayati, R.W.; Oceandy, D.; Widyaningtyas, S.T.; Pratama, M.D.; Jang, G. Genetic Engineering of Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Enhance BMP-2 Secretion via Signal Peptide Optimization. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010076

Mazfufah NF, Dilogo IH, Nurhayati RW, Oceandy D, Widyaningtyas ST, Pratama MD, Jang G. Genetic Engineering of Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Enhance BMP-2 Secretion via Signal Peptide Optimization. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazfufah, Nuzli Fahdia, Ismail Hadisoebroto Dilogo, Retno Wahyu Nurhayati, Delvac Oceandy, Silvia Tri Widyaningtyas, Maulana Dias Pratama, and Goo Jang. 2026. "Genetic Engineering of Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Enhance BMP-2 Secretion via Signal Peptide Optimization" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010076

APA StyleMazfufah, N. F., Dilogo, I. H., Nurhayati, R. W., Oceandy, D., Widyaningtyas, S. T., Pratama, M. D., & Jang, G. (2026). Genetic Engineering of Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Enhance BMP-2 Secretion via Signal Peptide Optimization. Biomedicines, 14(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010076