Long-Term Prognosis and Impact Factors of Metoprolol Treatment in Children with Vasovagal Syncope

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Head-Up Tilt Test

2.3. Analysis of Heart Rate Variability Indicators

2.4. Treatment Regimen and the Protocol of Follow-Up

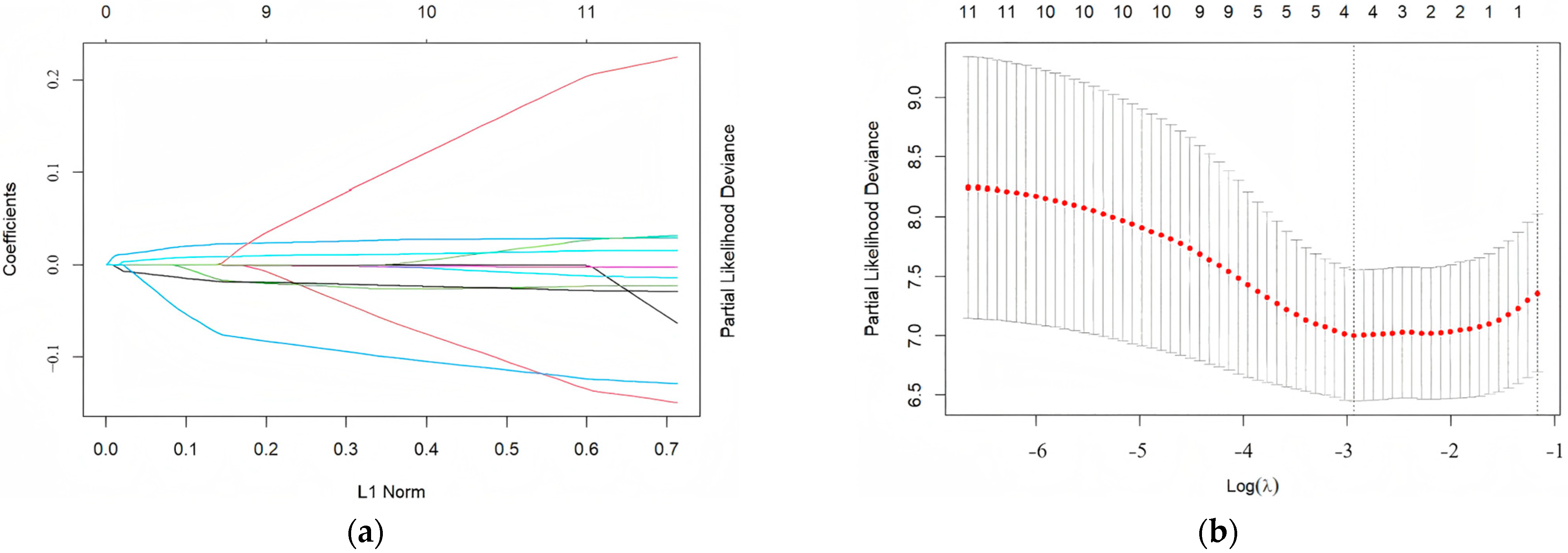

2.5. Establishment of PRS Model

2.6. Evaluation and Validation of PRS Model

2.7. Stratification Based on the PRS Model

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Factors Affecting Long-Term Prognosis of Children with Vasovagal Syncope Treated with Metoprolol and Modeling of Prognostic Risk Score

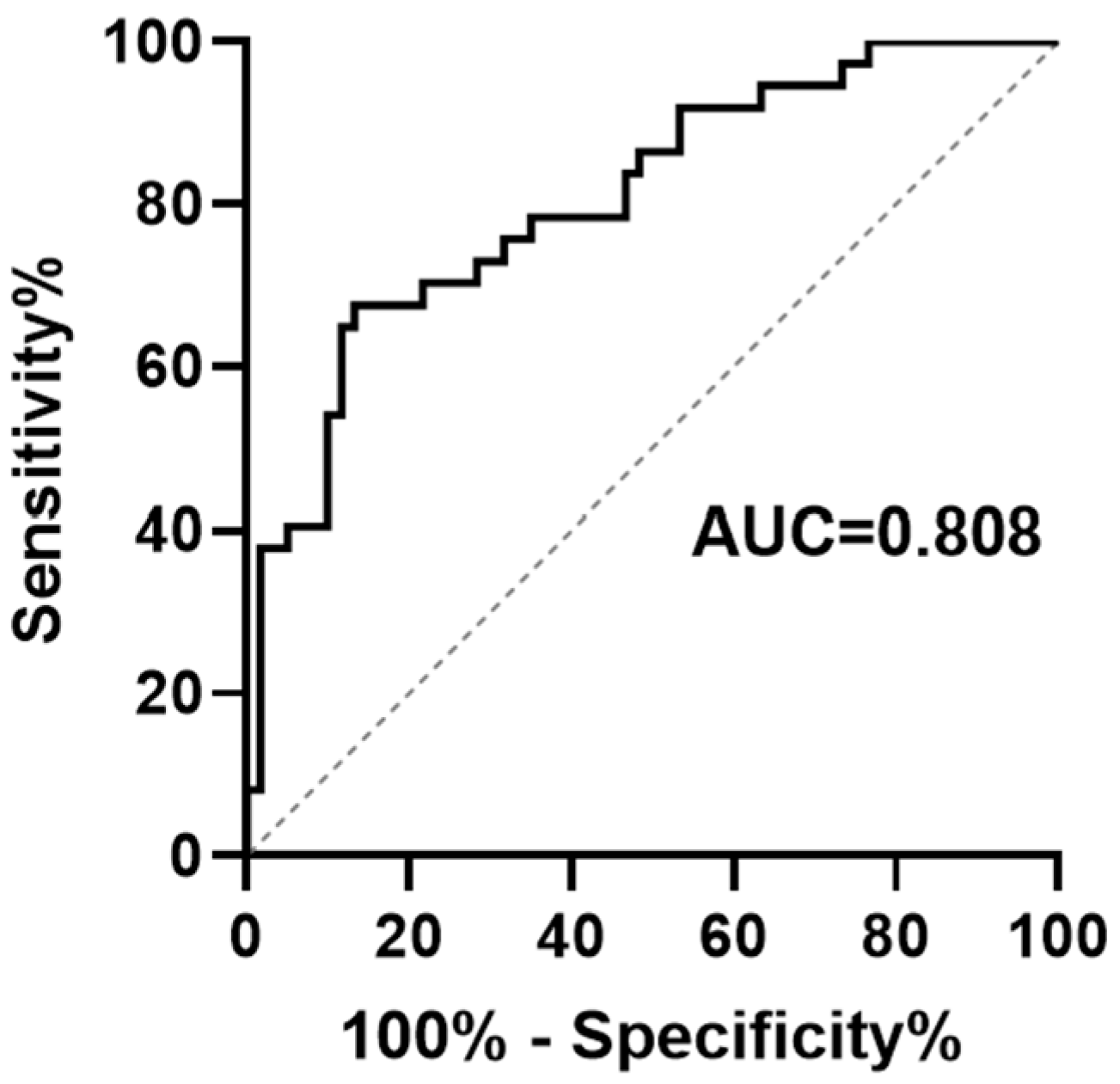

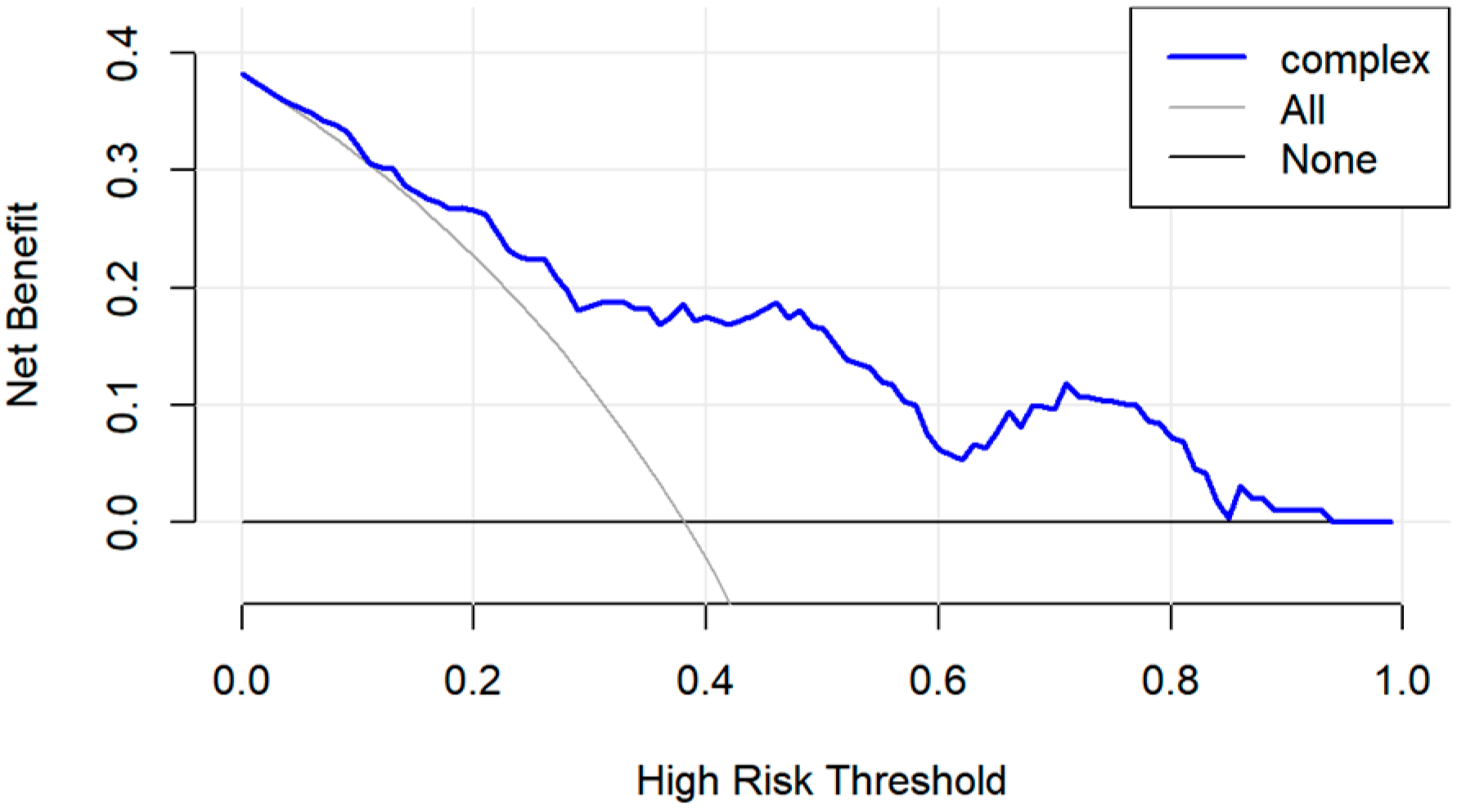

3.3. Evaluation and Validation of Prognostic Risk Score Model

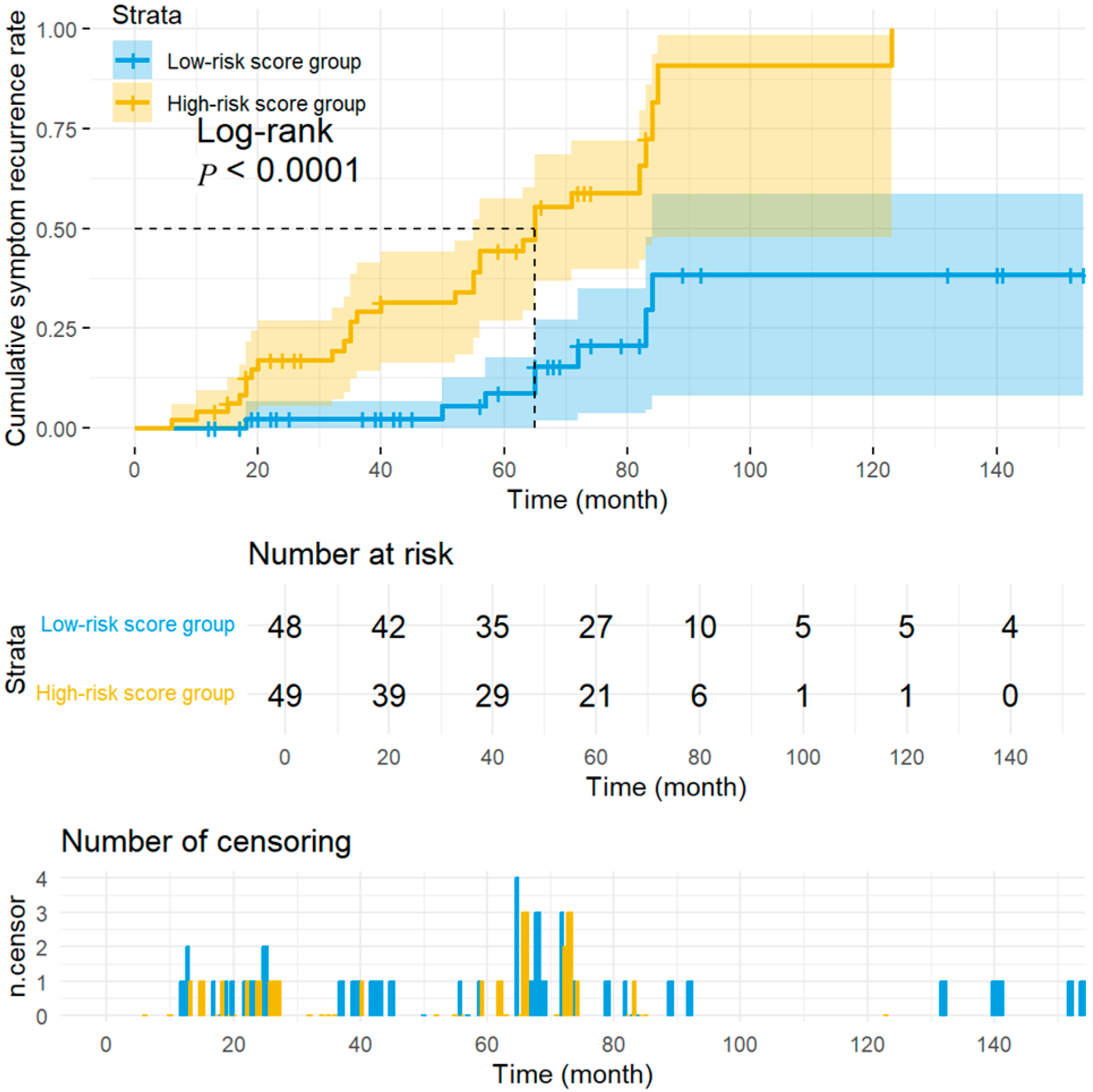

3.4. Stratified Analysis of Long-Term Prognosis of Children with Vasovagal Syncope Treated with Metoprolol Based on Prognostic Risk Score Modeling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASDNN | mean of the standard deviation of NN intervals for each 5 min segment |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| Bca | Bias-corrected and accelerated |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CS | Cardiogenic syncope |

| DCA | Decision curve analysis |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| HF | High frequency |

| HR | Hazard ratios |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| HUTT | Head-up tilt test |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| LF | Low frequency |

| MPV | Mean platelet volume |

| NMS | Neurally mediated syncope |

| pNN50 | Adjacent NN intervals > 50 ms |

| PRS | Prognostic Risk Score |

| QTcd | Corrected QT dispersion |

| rMSSD | Root mean square of the successful NN interval differences |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristics |

| SDANN | Standard deviation of the averages of NN intervals in all 5 min segments of the entire recording |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of all NN intervals |

| TR | Triangular index |

| VLF | Very low frequency |

| VVS | Vasovagal syncope |

References

- Wang, C.; Liao, Y.; Wang, S.; Tian, H.; Huang, M.; Dong, X.-Y.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.-Q.; Sun, J.-H.; Du, J.-B.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neurally mediated syncope in children and adolescents (revised 2024). World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco-Pascual, J.; Medina Maguiña, J.; Rivas-Gándara, N. Autonomic syncope. Med. Clin. 2025, 165, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Doğan, M. The psychopathology, depression, and anxiety levels of children and adolescents with vasovagal syncope: A case-control study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, J.; Raj, S.; Teixeira, P.; Sheldon, R.S. Likelihood of injury due to vasovagal syncope: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2021, 23, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Pachon Maetos, J.; Kichloo, A.; Masudi, S.; Grubb, B.P.; Kanjwal, K. Management strategies for vasovagal syncope. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2021, 44, 2100–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Wang, C. How I treat vasovagal syncope in children. Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2025, 27, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Karemaker, J.M. The multibranched nerve: Vagal function beyond heart rate variability. Biol. Psychol. 2022, 172, 108378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D. Vasovagal syncope and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in adolescents: Transcranial doppler versus autonomic function test results. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2025, 68, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucci, V.; Protheroe, C.; Albaro, C.; Lloyd, M.; Armstrong, K.; Franciosi, S.; Sanatani, S.; Claydon, V. Autonomic responses in children and adolescents with orthostatic syncope and presyncope: Children are not small adults. Auton. Neurosci. 2025, 262, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Yang, X.; Cai, Z.; Pan, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Zhao, C. Twenty-four-hour urine NE level as a predictor of the therapeutic response to metoprolol in children with recurrent vasovagal syncope. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 188, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, X.; Tang, C.; Jin, H.; Du, J. Left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening are useful for the prediction of the therapeutic response to metoprolol in children with vasovagal syncope. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2018, 39, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, C.; Li, X.; Tang, C.; Jin, H.; Du, J. Baroreflex sensitivity predicts response to metoprolol in children with vasovagal syncope: A pilot study. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Wang, J.; Lin, J. Biomarkers and hemodynamic parameters in the diagnosis and treatment of children with postural tachycardia syndrome and vasovagal syncope. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncı, S.; Çoner, A.; Balcıoğlu, A.S.; Akbay, E.; Müderrisoğlu, İ.H. Heart rate variability and heart rate turbulence in patients with vasovagal syncope. Kardiologiia 2021, 61, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviele, A.; Giada, F.; Menozzi, C.; Speca, G.; Orazi, S.; Gasparini, G.; Sutton, R.; Brignole, M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of permanent cardiac pacing for the treatment of recurrent tilt-induced vasovagal syncope. The vasovagal syncope and pacing trial (SYNPACE). Eur. Heart J. 2004, 25, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, R.; Zalewski, P.; Newton, J.; Speca, G.; Orazi, S.; Gasparini, G.; Sutton, R.; Brignole, M. An assessment of heart rate and blood pressure asymmetry in the diagnosis of vasovagal syncope in females. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1087837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, S.; Park, S.; Moon, S.; Oh, J.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.H.; Han, J.W.; Lee, S.J. Baseline heart rate variability in children and adolescents with vasovagal syncope. Korean J. Pediatr. 2014, 57, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zou, R.; Wang, C. Research progress on the predictive value of electrocardiographic indicators in the diagnosis and prognosis of children with vasovagal syncope. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 916770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, P.; Zen, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Zou, R.; Wang, C. Differential diagnostic value of P wave dispersion and QT interval dispersion between psychogenic pseudosyncope and vasovagal syncope in children and adolescents. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2025, 51, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, V.; Parente, E.; Tomaino, M.; Comune, A.; Sabatini, A.; Laezza, N.; Carretta, D.; Nigro, G.; Rago, A.; Golino, P.; et al. Short-duration head-up tilt test potentiated with sublingual nitroglycerin in suspected vasovagal syncope: The fast Italian protocol. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilian, M.; Nasehi, M.; Farahmandi, F.; Tahouri, T.; Parhizgar, P. Association of supine and upright blood pressure differences with head-up tilt test outcomes in children with vasovagal syncope. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1438400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Gao, L.; Yuan, Y. Advance in the understanding of vasovagal syncope in children and adolescents. World J. Pediatr. 2021, 17, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahanonda, N.; Bhuipanyo, K.; Kangkagate, C.; Wansanit, K.; Kulchot, B.-O.; Nademanee, K.; Chaithiraphan, S. Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral atenolol in patients with unexplained syncope and positive upright tilt able test results. Am. Heart J. 1995, 130, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Ren, Z.; Ding, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhou, J.; Dong, L. Oral atenolol and enalapril in the treatment of vasovagal syncope: A therapeutic efficacy observation. Chin. J. Int. Cardiol. 2000, 8, 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Huang, X. A comparative study of drug therapy for vasovagal syncope. Chin. J. Pract. Intern. Med. 1999, 19, 678–679. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R. Therapeutic efficacy observation of atenolol and scopolamine in the treatment of vasovagal syncope. Cent. Plains Med. J. 2004, 31, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, R.; Maas, R.; Zeidler, D.; Schoder, V.; Nienaber, C.; Schuchert, A.; Meinertz, T. A randomized and controlled pilot trial of β-blockers for the treatment of recurrent syncope in patients with a positive or negative response to head-up tilt test. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2002, 25, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Yu, X.; Tang, Y.; Ai, Q. Therapeutic effect of oral metoprolol in the treatment of vasovagal syncope. J. Univ. South China (Med. Ed.). 2003, 31, 424–425. [Google Scholar]

- Klingenheben, T.; Kalusche, D.; Li, Y.; SCHÖPPERL, M.; Hohnloser, S.H. Changes in plasma epinephrine concentration and in heart rate during head-up tilt testing in patients with neurocardiogenic syncope: Correlation with successful therapy with beta-receptor antagonists. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1996, 7, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Du, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Du, Z.-D.; Wang, H.-W.; Tian, H.; Chen, J.-J.; Wang, Y.-L.; Hu, X.-F.; et al. A multicenter study on treatment of autonomous nerve-mediated syncope in children with beta-receptor blocker. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2007, 45, 885–888. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, C.; Xu, B.; Liao, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, H.; Du, J. Predictor of syncopal recurrence in children with vasovagal syncope treated with metoprolol. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 870939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladage, D.; Schwinger, R.H.; Brixius, K. Cardio-selective beta-blocker: Pharmacological evidence and their influence on exercise capacity. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2013, 31, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Jin, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Tang, C.; Du, J. Randomized comparison of metoprolol versus conventional treatment in preventing recurrence of vasovagal syncope in children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Monit. 2008, 14, CR199-203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kouakam, C.; Vaksmann, G.; Pachy, E.; Lacroix, D.; Rey, C.; Kacet, S. Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with syncope; predictor of syncope recurrence. Eur. Heart J. 2001, 22, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xie, L. Research status of cardiac autonomic nervous system regulation in vasovagal syncope in children. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2022, 40, 494–499. [Google Scholar]

- Braunisch, M.C.; Mayer, C.C.; Werfel, S.; Bauer, A.; Haller, B.; Lorenz, G.; Günthner, R.; Matschkal, J.; Bachmann, Q.; Thunich, S.; et al. U-shaped association of the heart rate variability triangular index and mortality in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 751052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.; Vanoli, E.; Stramba-Badiale, M.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Billman, G.E.; Foreman, R.D. Autonomic mechanisms and sudden death. New insights from analysis of baroreceptor reflexes in conscious dogs with and without a myocardial infarction. Circulation 1988, 78, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmerle, P.; Eick, C.; Blum, S.; Schlageter, V.; Bauer, A.; Rizas, K.D.; Eken, C.; Coslovsky, M.; Aeschbacher, S.; Krisai, P.; et al. Heart rate variability triangular index as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longin, E.; Reinhard, J.; Vonbuch, C.; Gerstner, T.; Lenz, T.; König, S. Autonomic function in children and adolescents with neurocardiogenic syncope. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2008, 29, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainuma, M.; Furusyo, N.; Ando, S.; Mukae, H.; Ogawa, E.; Toyoda, K.; Murata, M.; Hayashi, J. Nocturnal difference in the ultra low frequency band of heart rate variability in patients stratified by kampo medicine prescription. Circ. J. 2014, 78, 1924–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orini, M.; Bailón, R.; Laguna, P.; Mainardi, L.T. Modeling and estimation of time-varying heart rate variability during stress test by parametric and non parametric analysis. Comput. Cardiol. 2007, 34, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, R.; Malik, S.; Raj, T.; Kumar, P. Analysis of heart rate variability and implication of different factors on heart rate variability. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 17, e160721189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liu, K.; Xu, W.; Du, J. Multivariate predictive model of the therapeutic effects of metoprolol in paediatric vasovagal syncope: A multi-centre study. EBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Liao, Y.; Jin, H.-F.; Du, J.-B. Age and mean platelet volume-based nomogram for predicting the therapeutic efficacy of metoprolol in Chinese pediatric patients with vasovagal syncope. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Jin, H. Prognostic analysis of orthostatic intolerance using survival model in children. Chin. Med. J. 2014, 127, 3690–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Baseline Value | |

|---|---|---|

| number (n) | 97 | |

| sex (female/male, n) | 49/48 | |

| age (year) | 12.0 (11.0, 14.0) | |

| diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 67.0 (60.0, 75.5) | |

| systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 111.0 (106.0, 121.0) | |

| heart rate (bpm) | 81.0 ± 9.0 | |

| SDNN (ms) | 139.9 ± 33.5 | |

| SDANN (ms) | 131.0 (102.5, 162.5) | |

| ASDNN (ms) | 69.1 ± 19.4 | |

| rMSSD (ms) | 43.0 (32.5, 60.5) | |

| pNN50 (%) | 17.0 (9.8, 26.8) | |

| TR | 29.0 (27.0, 31.0) | |

| HF (ms) | 23.0 (17.3, 32.7) | |

| LF (ms) | 29.0 (23.4, 34.6) | |

| VLF (ms) | 43.1 (35.8, 50.8) | |

| LF/HF (ms) | 1.34 (1.1, 1.6) | |

| hemodynamic types of VVS (n) | vasopressor | 84 |

| cardioinhibitory | 7 | |

| mixed | 6 | |

| syncope triggers (n) | postural changes | 28 |

| standing for a long time | 26 | |

| stifling environment | 7 | |

| emotional condition | 5 | |

| exercise (walking/running or jumping/stairs/higher leg lifts) | 10 (5/2/2/1) | |

| other situations (turning/blood draws/intramuscular injections/combing hair) | 4 (1/1/1/1) | |

| no triggers | 17 | |

| precursor symptoms of syncope (n) | blackouts and blurred vision | 38 |

| dizziness, tinnitus | 43 | |

| pale and weak | 25 | |

| without precursor symptoms | 8 | |

| total number of syncopal episodes before treatment | 4 (2, 6) | |

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| number [n (%)] | - | - |

| diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.65 |

| systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.93 |

| heart rate (bpm) | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) | 0.02 |

| age (years) | 1.00 (0.98–1.00) | 0.96 |

| HF (ms) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.65 |

| SDNN (ms) | 1.00 (1.01–1.03) | 0.01 |

| rMSSD (ms) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.01 |

| SDANN (ms) | 1.01 (0.99–1.01) | 0.03 |

| VLF (ms) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.17 |

| LF (ms) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.54 |

| LF/HF | 0.61 (0.32–1.10) | 0.12 |

| pNN50 (%) | 1.00 (0.99–1.05) | 0.01 |

| TR | 1.00 (0.99–1.10) | 0.01 |

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDNN (ms) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.001 | 0.03 |

| VLF (ms) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.049 | −0.02 |

| TR | 0.90 (0.84–0.97) | 0.003 | −0.10 |

| ASDNN (ms) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.297 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Liao, Y.; Jin, H. Long-Term Prognosis and Impact Factors of Metoprolol Treatment in Children with Vasovagal Syncope. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010075

Wang J, Liu P, Wang Y, Du J, Liao Y, Jin H. Long-Term Prognosis and Impact Factors of Metoprolol Treatment in Children with Vasovagal Syncope. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Ping Liu, Yuli Wang, Junbao Du, Ying Liao, and Hongfang Jin. 2026. "Long-Term Prognosis and Impact Factors of Metoprolol Treatment in Children with Vasovagal Syncope" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010075

APA StyleWang, J., Liu, P., Wang, Y., Du, J., Liao, Y., & Jin, H. (2026). Long-Term Prognosis and Impact Factors of Metoprolol Treatment in Children with Vasovagal Syncope. Biomedicines, 14(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010075