Trained Immunity in Bladder ILC3s Enhances Mucosal Defense Against Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Samples

2.2. Bacterial Strains

2.3. Bacterial Lysate Preparation

2.4. MNK3 Cell Culture

2.5. Mouse Model of UTI and Experimental Design

2.6. Determination of Bacterial Burden

2.7. Isolation of Leukocytes from Bladders and Kidneys

2.8. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.9. Detection of Cytokines in ILCs

2.10. Adoptive Transfer of ILC3s

2.11. In Vivo Neutralization of IL-17A and IL-22

2.12. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

2.13. Immunofluorescence Staining (IF) and Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.14. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

2.15. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. ILC3s Increase Systematically During UPEC-Induced Urinary Tract Infection

3.2. ILC3s Contribute to Protection Against UTI

3.3. ILC3s Orchestrate Epithelial Barrier Repair and Restrain Inflammatory Infiltration During UTI

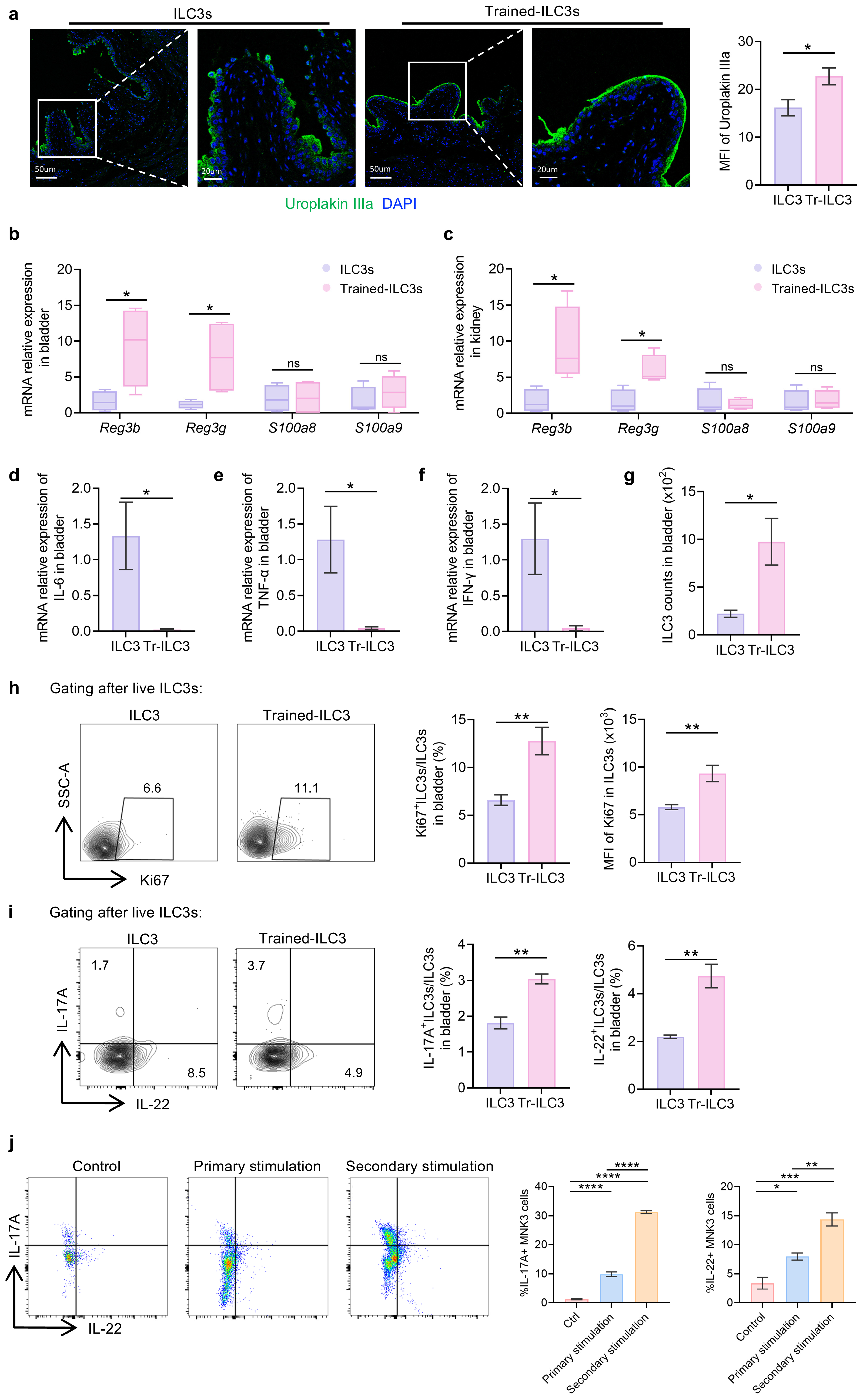

3.4. UPEC-Trained ILC3s Confer Enhanced Protection Against Recurrent UTI Through Pathogen Clearance and Tissue Preservation

3.5. Tr-ILC3s Acquire Cell-Intrinsic Functional and Proliferative Advantages

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| ILC | Innate lymphoid cell |

| ILC3 | Group 3 innate lymphoid cell |

| UPEC | Uropathogenic Escherichia coli |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| BCG | Bacille Calmette-Guérin |

| IL-17A | Interleukin-17A |

| IL-22 | Interleukin-22 |

| Upk3a | Uroplakin IIIa |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| AMP | Antibacterial peptides |

| HC | Healthy controls |

References

- Ambite, I.; Butler, D.; Wan, M.L.Y.; Rosenblad, T.; Tran, T.H.; Chao, S.M.; Svanborg, C. Molecular Determinants of Disease Severity in Urinary Tract Infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 468–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihta, K.-D.; Stoesser, N.; Llewelyn, M.J.; Quan, T.P.; Davies, T.; Fawcett, N.J.; Dunn, L.; Jeffery, K.; Butler, C.C.; Hayward, G.; et al. Trends over Time in Escherichia coli Bloodstream Infections, Urinary Tract Infections, and Antibiotic Susceptibilities in Oxfordshire, UK, 1998-2016: A Study of Electronic Health Records. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hout, D.; Verschuuren, T.D.; Bruijning-Verhagen, P.C.J.; Bosch, T.; Schürch, A.C.; Willems, R.J.L.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing and Non-ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates Causing Bacteremia in the Netherlands (2014–2016) Differ in Clonal Distribution, Antimicrobial Resistance Gene and Virulence Gene Content. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, M.R.; Russell, S.K.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary Tract Infections: Pathogenesis, Host Susceptibility and Emerging Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenlehner, F.M.E.; Bjerklund Johansen, T.E.; Cai, T.; Koves, B.; Kranz, J.; Pilatz, A.; Tandogdu, Z. Epidemiology, Definition and Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020, 17, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghoraibi, H.; Asidan, A.; Aljawaied, R.; Almukhayzim, R.; Alsaydan, A.; Alamer, E.; Baharoon, W.; Masuadi, E.; Al Shukairi, A.; Layqah, L.; et al. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection in Adult Patients, Risk Factors, and Efficacy of Low Dose Prophylactic Antibiotics Therapy. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, S.D.; Thaden, J.T.; Perez, R.; Stair, S.L.; Lee, U.J.; Siddiqui, N.Y. State-of-the-Art Review: Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 80, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lv, Z.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, A.; Niu, H. The Immune Mechanisms of the Urinary Tract against Infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1540149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, G.F.; Artis, D. Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Initiation, Regulation and Resolution of Inflammation. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, Y.; Obata, T.; Kunisawa, J.; Sato, S.; Ivanov, I.I.; Lamichhane, A.; Takeyama, N.; Kamioka, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Matsuki, T.; et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells Regulate Intestinal Epithelial Cell Glycosylation. Science 2014, 345, 1254009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Guo, X.; Chen, Z.-M.E.; He, L.; Sonnenberg, G.F.; Artis, D.; Fu, Y.-X.; Zhou, L. Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells Inhibit T-Cell-Mediated Intestinal Inflammation through Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling and Regulation of Microflora. Immunity 2013, 39, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, G.F.; Monticelli, L.A.; Alenghat, T.; Fung, T.C.; Hutnick, N.A.; Kunisawa, J.; Shibata, N.; Grunberg, S.; Sinha, R.; Zahm, A.M.; et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells Promote Anatomical Containment of Lymphoid-Resident Commensal Bacteria. Science 2012, 336, 1321–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.I.; Li, Y.; Lopez-Lastra, S.; Stadhouders, R.; Paul, F.; Casrouge, A.; Serafini, N.; Puel, A.; Bustamante, J.; Surace, L.; et al. Systemic Human ILC Precursors Provide a Substrate for Tissue ILC Differentiation. Cell 2017, 168, 1086–1100.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivier, E.; Artis, D.; Colonna, M.; Diefenbach, A.; Di Santo, J.P.; Eberl, G.; Koyasu, S.; Locksley, R.M.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Mebius, R.E.; et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Cell 2018, 174, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gury-BenAri, M.; Thaiss, C.A.; Serafini, N.; Winter, D.R.; Giladi, A.; Lara-Astiaso, D.; Levy, M.; Salame, T.M.; Weiner, A.; David, E.; et al. The Spectrum and Regulatory Landscape of Intestinal Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Shaped by the Microbiome. Cell 2016, 166, 1231–1246.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, C.S.N.; Artis, D. Innate Lymphoid Cells as Regulators of Immunity, Inflammation and Tissue Homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, V.S.; Viragova, S.; Koga, S.; Liu, M.; O’Leary, C.E.; Ricardo-Gonzalez, R.R.; Schroeder, A.W.; Kochhar, N.; Vaka, D.; Boffelli, D.; et al. IL-25-Induced Memory Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Enforce Mucosal Immunity. Cell 2025, 188, 6220–6235.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jacobse, J.; Pilat, J.M.; Kaur, H.; Gu, W.; Kang, S.W.; Rusznak, M.; Huang, H.-I.; Barrera, J.; Oloo, P.A.; et al. Interleukin-10 Production by Innate Lymphoid Cells Restricts Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2025, 18, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.-Y.; Shui, J.-W.; Takahashi, D.; Song, C.; Wang, Q.; Kim, K.; Mikulski, Z.; Chandra, S.; Giles, D.A.; Zahner, S.; et al. LIGHT-HVEM Signaling in Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets Protects Against Enteric Bacterial Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 249–260.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ji, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Li, Q. Lentinan Mitigates Ulcerative Colitis via the IL-22 Pathway to Repair the Compromised Mucosal Barrier and Enhance Antimicrobial Defense. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabil, A.K.; Liu, L.T.; Xu, C.; Nayyar, N.; González, L.; Chopra, S.; Brassard, J.; Beaulieu, M.-J.; Li, Y.; Damji, A.; et al. Microbial Dysbiosis Sculpts a Systemic ILC3/IL-17 Axis Governing Lung Inflammatory Responses and Central Hematopoiesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2025, 18, 1139–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Fu, L.; Huang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B.; Qiu, J.; Hu, X.; et al. Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells Protect the Host from the Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Infection in the Bladder. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Domínguez-Andrés, J.; Barreiro, L.B.; Chavakis, T.; Divangahi, M.; Fuchs, E.; Joosten, L.A.B.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; Mhlanga, M.M.; Mulder, W.J.M.; et al. Defining Trained Immunity and Its Role in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Latz, E.; Mills, K.H.G.; Natoli, G.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; O’Neill, L.A.J.; Xavier, R.J. Trained Immunity: A Program of Innate Immune Memory in Health and Disease. Science 2016, 352, aaf1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, E.; Khan, N.; Tran, K.A.; Ulndreaj, A.; Pernet, E.; Fontes, G.; Lupien, A.; Desmeules, P.; McIntosh, F.; Abow, A.; et al. BCG Vaccination Provides Protection against IAV but Not SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintin, J.; Saeed, S.; Martens, J.H.A.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Ifrim, D.C.; Logie, C.; Jacobs, L.; Jansen, T.; Kullberg, B.-J.; Wijmenga, C.; et al. Candida Albicans Infection Affords Protection against Reinfection via Functional Reprogramming of Monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Zhou, J.; Mei, J.; Gao, C.; Ding, P.; Li, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Gao, J. Trained Immunity in Health and Disease. MedComm 2025, 6, e70461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minute, L.; Montalbán-Hernández, K.; Bravo-Robles, L.; Conejero, L.; Iborra, S.; Del Fresno, C. Trained Immunity-Based Mucosal Immunotherapies for the Prevention of Respiratory Infections. Trends Immunol. 2025, 46, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, T.; van Elsas, Y.; Priem, B.; Ziogas, A.; Netea, M.G. Trained Immunity: Induction of an Inflammatory Memory in Disease. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, N.; Jarade, A.; Surace, L.; Goncalves, P.; Sismeiro, O.; Varet, H.; Legendre, R.; Coppee, J.-Y.; Disson, O.; Durum, S.K.; et al. Trained ILC3 Responses Promote Intestinal Defense. Science 2022, 375, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizman, O.-E.; Song, E.; Adams, N.M.; Hildreth, A.D.; Riggan, L.; Krishna, C.; Aguilar, O.A.; Leslie, C.S.; Carlyle, J.R.; Sun, J.C.; et al. Mouse Cytomegalovirus-Experienced ILC1s Acquire a Memory Response Dependent on the Viral Glycoprotein M12. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, I.; Mathä, L.; Steer, C.A.; Ghaedi, M.; Poon, G.F.T.; Takei, F. Allergen-Experienced Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Acquire Memory-like Properties and Enhance Allergic Lung Inflammation. Immunity 2016, 45, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Liu, B.; Wu, L.; Bao, H.; García, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. A Broad-Spectrum Phage Endolysin (LysCP28) Able to Remove Biofilms and Inactivate Clostridium Perfringens Strains. Foods 2023, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, N.; Ferrara, F.; Rial, A.; Dee, V.; Chabalgoity, J.A. Bacterial Lysates as Immunotherapies for Respiratory Infections: Methods of Preparation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, D.S.J.; Kirkham, C.L.; Aguilar, O.A.; Qu, L.C.; Chen, P.; Fine, J.H.; Serra, P.; Awong, G.; Gommerman, J.L.; Zúñiga-Pflücker, J.C.; et al. An in Vitro Model of Innate Lymphoid Cell Function and Differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michieletto, M.F.; Tello-Cajiao, J.J.; Mowel, W.K.; Chandra, A.; Yoon, S.; Joannas, L.; Clark, M.L.; Jimenez, M.T.; Wright, J.M.; Lundgren, P.; et al. Multiscale 3D Genome Organization Underlies ILC2 Ontogenesis and Allergic Airway Inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-S.; Dodson, K.W.; Hultgren, S.J. A Murine Model of Urinary Tract Infection. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1230–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iribarnegaray, V.; González, M.; Caetano, A.; Platero, R.; Zunino, P.; Scavone, P. Relevance of Iron Metabolic Genes in Biofilm and Infection in Uropathogenic Proteus Mirabilis. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, N.; Ding, X.; Peng, L.; Deng, X. The Molybdate-Binding Protein ModA Is Required for Proteus Mirabilis-Induced UTI. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1156273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, M.; Lacerda Mariano, L.; Canton, T.; Ingersoll, M.A. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Mediate Mucosal Immunity to Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eabn4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, E.Y.H.; Kwek, G.; An, X.; Sun, C.; Liu, S.; Qing, N.S.; Lingesh, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, G.; Xing, B. Enzymes in Synergy: Bacteria Specific Molecular Probe for Locoregional Imaging of Urinary Tract Infection in Vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202406843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Jin, C.; Liu, L.; Sun, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, R.; Zheng, X.; et al. Nucleoside-Diphosphate Kinase of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Inhibits Caspase-1-Dependent Pyroptosis Facilitating Urinary Tract Infection. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.-Y.; Cao, B.; Chen, W.-B.; Wu, W.; Zhao, S.; Min, X.-Y.; Yang, J.; Han, J.; Dong, X.; Wang, N.; et al. Collectin 11 Has a Pivotal Role in Host Defense against Kidney and Bladder Infection in Mice. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segueni, N.; Tritto, E.; Bourigault, M.L.; Rose, S.; Erard, F.; Le Bert, M.; Jacobs, M.; Di Padova, F.; Stiehl, D.P.; Moulin, P.; et al. Controlled Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection in Mice under Treatment with Anti-IL-17A or IL-17F Antibodies, in Contrast to TNFα Neutralization. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; Guo, H.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, N.; Chai, T.C.; et al. Pyroptosis Engagement and Bladder Urothelial Cell-Derived Exosomes Recruit Mast Cells and Induce Barrier Dysfunction of Bladder Urothelium after Uropathogenic E. coli Infection. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C544–C555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda Mariano, L.; Rousseau, M.; Varet, H.; Legendre, R.; Gentek, R.; Saenz Coronilla, J.; Bajenoff, M.; Gomez Perdiguero, E.; Ingersoll, M.A. Functionally Distinct Resident Macrophage Subsets Differentially Shape Responses to Infection in the Bladder. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.W.; Bowen, S.E.; Miao, Y.; Chan, C.Y.; Miao, E.A.; Abrink, M.; Moeser, A.J.; Abraham, S.N. Loss of Bladder Epithelium Induced by Cytolytic Mast Cell Granules. Immunity 2016, 45, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.J.; Gendron-Fitzpatrick, A.; Balish, E.; Uehling, D.T. Time Course and Host Responses to Escherichia coli Urinary Tract Infection in Genetically Distinct Mouse Strains. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 2798–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, F.; Flutter, B.; Tosi, I.; Grys, K.; Sreeneebus, H.; Perera, G.K.; Chapman, A.; Smith, C.H.; Di Meglio, P.; Nestle, F.O. Characterization of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Human Skin and Blood Demonstrates Increase of NKp44+ ILC3 in Psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, V.; Cao, S.; Trsan, T.; Bando, J.K.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Cleveland, J.L.; Clish, C.; Xavier, R.J.; Colonna, M. Ornithine Decarboxylase Supports ILC3 Responses in Infectious and Autoimmune Colitis through Positive Regulation of IL-22 Transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2214900119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, Z.; De la Cruz, M.A.; Carrillo-Casas, E.M.; Durán, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Puente, J.L.; Daaka, Y.; Girón, J.A. Production of the Escherichia coli Common Pilus by Uropathogenic E. coli Is Associated with Adherence to HeLa and HTB-4 Cells and Invasion of Mouse Bladder Urothelium. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Chen, J.-W.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Zhang, C.; Shen, S.-H.; Liu, M.-Z.; Fan, Y.; Yang, S.-Q.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Wang, W.; et al. UPK3A+ Umbrella Cell Damage Mediated by TLR3-NR2F6 Triggers Programmed Destruction of Urothelium in Hunner-Type Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. J. Pathol. 2024, 263, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izgi, K.; Altuntas, C.Z.; Bicer, F.; Ozer, A.; Sakalar, C.; Li, X.; Tuohy, V.K.; Daneshgari, F. Uroplakin Peptide-Specific Autoimmunity Initiates Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome in Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, T.J.; Mysorekar, I.U.; Hung, C.S.; Isaacson-Schmid, M.L.; Hultgren, S.J. Early Severe Inflammatory Responses to Uropathogenic E. coli Predispose to Chronic and Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blango, M.G.; Ott, E.M.; Erman, A.; Veranic, P.; Mulvey, M.A. Forced Resurgence and Targeting of Intracellular Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Reservoirs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divangahi, M.; Aaby, P.; Khader, S.A.; Barreiro, L.B.; Bekkering, S.; Chavakis, T.; van Crevel, R.; Curtis, N.; DiNardo, A.R.; Dominguez-Andres, J.; et al. Trained Immunity, Tolerance, Priming and Differentiation: Distinct Immunological Processes. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 2–6, Erratum in Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 928. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-00960-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, M.; Baranda, J.; Pérez-Rodríguez, L.; Conde, P.; de la Calle-Fabregat, C.; Berges-Buxeda, M.J.; Dimitrov, A.; Arranz, J.; Rius-Rocabert, S.; Zotta, A.; et al. In Vitro Protocol Demonstrating Five Functional Steps of Trained Immunity in Mice: Implications on Biomarker Discovery and Translational Research. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.D.; Alder, M.N. The Evolution of Adaptive Immune Systems. Cell 2006, 124, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochando, J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Madsen, J.C.; Netea, M.G.; Duivenvoorden, R. Trained Immunity—Basic Concepts and Contributions to Immunopathology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.B. Trained Innate Immunity: Concept, Nomenclature, and Future Perspectives. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Quintin, J.; van der Meer, J.W.M. Trained Immunity: A Memory for Innate Host Defense. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, L.; Alvarez, S.; Allam, A.; Reinhard, M.; Brown, M.B. Complicated Urinary Tract Infection Is Associated with Uroepithelial Expression of Proinflammatory Protein S100A8. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 4265–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, E.K.; Džidić-Krivić, A.; Sesar, A.; Farhat, E.K.; Čeliković, A.; Beća-Zećo, M.; Pinjic, E.; Sher, F. Current State and Novel Outlook on Prevention and Treatment of Rising Antibiotic Resistance in Urinary Tract Infections. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 261, 108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, D.C.; Juelke, K.; Müller, N.C.; Durek, P.; Ugursu, B.; Mashreghi, M.-F.; Rückert, T.; Romagnani, C. An in Vitro Platform Supports Generation of Human Innate Lymphoid Cells from CD34+ Hematopoietic Progenitors That Recapitulate Ex Vivo Identity. Immunity 2021, 54, 2417–2432.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennstein, S.B.; Weinhold, S.; Degistirici, Ö.; Oostendorp, R.A.J.; Raba, K.; Kögler, G.; Meisel, R.; Walter, L.; Uhrberg, M. Efficient In Vitro Generation of IL-22-Secreting ILC3 From CD34+ Hematopoietic Progenitors in a Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Niche. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 797432, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1292209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1292209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.Z.; Haverkate, N.J.E.; van Hoeven, V.; Blom, B.; Hazenberg, M.D. Drug Exporter Expression Correlates with Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cell Resistance to Immunosuppressive Agents. Front. Hematol. 2023, 2, 1144418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, J.E.; Di Venanzio, G.; Hultgren, S.J.; Feldman, M.F. Catheterization Triggers Resurgent Infection Seeded by Host Acinetobacter Baumannii Reservoirs. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabn8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, T.; Jiang, M.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.; et al. Glutamine Promotes Antibiotic Uptake to Kill Multidrug-Resistant Uropathogenic Bacteria. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabj0716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, L.; Bochter, M.S.; Simoni, A.; Bender, K.; de Dios Ruiz Rosado, J.; Cotzomi-Ortega, I.; Sanchez-Zamora, Y.I.; Becknell, B.; Linn, S.; Li, B.; et al. Repurposing HDAC Inhibitors to Enhance Ribonuclease 4 and 7 Expression and Reduce Urinary Tract Infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2213363120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pei, Q.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Tan, J.; Han, X.; Hu, X.; Liang, Z.; Li, F.; Zhu, C.; Lin, R.; et al. Trained Immunity in Bladder ILC3s Enhances Mucosal Defense Against Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010078

Pei Q, Liu J, Tang Z, Tan J, Han X, Hu X, Liang Z, Li F, Zhu C, Lin R, et al. Trained Immunity in Bladder ILC3s Enhances Mucosal Defense Against Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010078

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Qiaoqiao, Jiaqi Liu, Ziwen Tang, Jiaqing Tan, Xu Han, Xinrong Hu, Zhou Liang, Feng Li, Changjian Zhu, Ruoni Lin, and et al. 2026. "Trained Immunity in Bladder ILC3s Enhances Mucosal Defense Against Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010078

APA StylePei, Q., Liu, J., Tang, Z., Tan, J., Han, X., Hu, X., Liang, Z., Li, F., Zhu, C., Lin, R., Zheng, R., Shen, J., Liu, Q., Mao, H., Wu, K., Chen, W., & Zhou, Y. (2026). Trained Immunity in Bladder ILC3s Enhances Mucosal Defense Against Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Biomedicines, 14(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010078