Abstract

Background: Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer is an inherited condition caused by pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Population-level sequencing allows for the identification of asymptomatic genotype-positive participants (GPPs) before disease onset. This study assessed the feasibility and impact of returning clinically relevant BRCA results to participants at the Qatar Precision Health Institute (QPHI). Methods: We established a structured framework to identify and refer asymptomatic individuals who were found to carry P/LP variants in BRCA among 6142 QPHI participants. The process integrated genomic analysis, participant recontact, counseling, referral, variants validation, and personalized risk-reducing strategies. Results: Six variants (four BRCA1, two BRCA2) were validated in ten GPPs with a median age of 48 years (IQR: 40.5–56). Eight variants were confirmed through Sanger sequencing in a CAP-accredited laboratory at Hamad Medical Corporation. All eligible participants were referred for counseling and personalized clinical management. Four men initiated breast and prostate cancer surveillance, while four women pursued breast and ovarian surveillance. One asymptomatic GPP underwent prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, revealing early-stage ovarian cancer. Cascade testing identified 20 additional GPPs and, in one asymptomatic relative, facilitated the detection of early-stage uterine cancer. The genetic testing acceptability rate was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.46–0.94), with a 100% adherence to surveillance at 12- and 24-month follow-ups. Conclusions: This pilot demonstrates the feasibility and clinical utility of returning actionable BRCA1/2 findings and represents the first initiative in an Arabic population to implement the return of medically actionable BRCA results from a population-based biobank.

1. Background

Genome sequencing increases the likelihood of detecting secondary findings (SFs), which are results not directly related to the primary indications for genetic testing but that have an established clinical actionability. The approach to reporting these findings has transitioned from initial recommendations to the establishment of well-defined and structured guidelines [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommends the analysis and reporting of pathogenic (P) and likely pathogenic (LP) variants in 81 genes, including BRCA1 and BRCA2, as these genes are deemed to be medically actionable and have available therapeutic and preventive interventions [8]. Given the complexity and potential health impact of returning actionable SFs, the broader utilization of genetic testing into routine clinical care raises several technical, logistical, and ethical challenges [9]. Addressing these challenges requires the integration of multidisciplinary efforts to effectively manage the clinical implications of these findings.

Individuals carrying germline P/LP variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have a cumulative lifetime risk of female breast cancer that is up to 80% and ovarian cancer risk up to 60% by age 80. Moreover, pathogenic variants in these genes can increase the male risk of breast and prostate cancer [10]. However, previous data indicate that BRCA1/2 testing provides significant benefits, particularly when coupled with risk-reducing strategies such as increased surveillance or prophylactic surgeries. For example, a prophylactic mastectomy can reduce breast cancer risk by more than 90% [11]. In Qatar, breast cancer remains the most diagnosed cancer among women, accounting for 39% of all cancer cases recorded in 2022, and has the highest mortality rate (11.4%) compared to other cancer types [12]. To address this, Qatar has implemented a national breast cancer screening program, offering population-wide screenings every three years for average-risk women aged 45 to 69. This initiative has proven effective in detecting early-stage breast cancer within a standard-risk population.

To improve early cancer detection among high-risk individuals, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) established a cancer genetic program in 2013 at the National Center for Cancer Care and Research (NCCCR). This program offers genetic counseling and high-risk surveillance to identify patients with an elevated lifetime risk of developing various cancers, as well as individuals already affected. The program offers genetic assessment, genetic testing, and risk-reducing strategies for high-risk individuals, as well as therapeutic measures and reproductive options based on the identified syndromes. Additionally, the program also offers cascade testing for family members, as well as personalized risk-reducing strategies [13]. Recently, HMC established the Centre of Clinical Precision Medicine and Genomics (CCPMG) in 2023 to serve as a model for multidisciplinary collaboration and to integrate genomic science into clinical workflows for delivering innovative and patient-centered care. The center features a one-stop clinic that combines clinical assessment, molecular laboratory testing, clinical management, and genomics-based lifestyle interventions under one roof, ensuring precise diagnoses, tailored treatments, and improved patient outcomes.

The Qatar Precision Health Institute (QPHI) is a national research center that integrates genome sequencing data from the Qatar Genome Program with comprehensive phenotypic data and biological samples from the Qatar Biobank to advance precision health [14]. In collaboration with the NCCCR program at HMC, we developed a communication and referral plan to evaluate the feasibility and clinical impact of delivering medically actionable BRCA1 and BRCA2 results to QPHI participants. Utilizing whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from 6142 participants, we established a framework for returning medically actionable BRCA1/2 findings and assessed the feasibility of integrating genetic testing with clinical surveillance to translate risk-reducing interventions from research to clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. The Qatar Precision Health Institute Cohort

The Qatar Biobank is a prospective, longitudinal, population-based study designed to generate extensive data from clinical assessments of Qataris and long-term residents of Qatar aged 18 years and older. Participants are followed up with every five years, and the data are integrated with genome sequencing data from the Qatar Genome Program [14,15]. All participants signed a general consent form allowing their data to be used anonymously for research purposes and permitting recontact for follow-up visits. The pilot study was approved by the Qatar Biobank Institutional Review Board (QF-QBB-RES-ACC-0241) and by the ethical committee of Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) (MRC-01-20-1148).

This study utilized genome sequencing data from 6142 participants recruited between December 2012 and August 2017. Detailed information about the QPHI cohort, phenotypic data, and genome sequencing is available in previous publications [14,15,16]. In brief, QPHI recruited participants who then attended an assessment session involving physical measurements and clinical tests. Standardized questionnaires were used to collect phenotypic data, capturing information on lifestyle and medical history. Biological samples (blood, saliva, and urine) were provided and stored at –80 °C in liquid nitrogen. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and sequenced on the HiSeq X Ten (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), with a minimum coverage of 30×. After quality control, the reads were aligned to the GRCh37 reference genome using bwa.kit (version 0.7.12). Variant calling was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit 3.4 best practices.

2.2. Definition of BRCA1/2 Actionable Findings

A medically actionable finding was defined as a P or LP variant in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. These variants had associated phenotypes unrelated to the primary test indication and were recommended for reporting to participants according to ACMG guidelines [8]. In addition to the biobank data, our analysis incorporated the bioinformatic annotation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene results from a publication by the Qatar Genome Program research consortium, authored by Saad and colleagues [16]. The final annotated variant list included any variant classified as P or LP in either ClinVar or CharGer [17], without any conflicting interpretations at a maximum allele frequency of less than 1%.

As the list of P/LP variants in BRCA1/2 genes provided by Saad and the team had been classified in research settings rather than clinics, each variant underwent a secondary review to generate a final list of P/LP variants that followed the ACMG/AMP classification criteria [18]. Participants with variants from this list were identified as potentially eligible for the pilot study.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Return of Results Workflow

In June 2019, the QPHI study protocol was updated to include the return of results, and only participants who opted for recontact were selected. Initially, de-identified codes were used to anonymize all participants in the research study conducted by Saad and the team, ensuring confidentiality. These participants were later re-identified at QPHI to access their electronic medical records (EMRs) and exclude those with a known medical diagnosis of breast and/or ovarian cancer, participants enrolled in the high-risk surveillance program, or participants who had previously received positive genetic test results for BRCA1/2 from other sources.

The potentially eligible participants were subsequently contacted during their follow-up visits to introduce the pilot study. A detailed family history was obtained from all eligible participants and was designated as strongly positive if a direct family member had been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer, or if they exhibited symptoms consistent with these cancers. A fresh blood sample (10 mL) was collected and sent to the clinically certified, CAP-accredited Diagnostics Genomic Division laboratory at HMC to confirm the presence of P/LP variants in BRCA1/2 genes through Sanger sequencing.

2.4. Genetic Counseling and Downstream Surveillance

Two dedicated genetic counselors were assigned to conduct counseling sessions for all eligible participants. In the first session, which occurred before the confirmatory Sanger sequencing test, the implications of BRCA1/2 actionable findings were explained, and any refusals to participate in the pilot study were documented. The second session took place after the presence of P/LP variants in BRCA1/2 was confirmed at the HMC CAP-accredited laboratory. During this session, the results were communicated by a clinical cancer genetic counselor to both the participants and their eligible family members, along with the potential health implications.

Based on the results of the confirmatory genetic test for BRCA1/2 variants, participants were classified into three groups. The first group consisted of participants who tested positive for P/LP variants in BRCA1/2, irrespective of their family history of associated cancers. The second group included those who tested negative but had a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Participants in these two groups were referred to the cancer genetics and high-risk surveillance program at HMC for further assessment. The third group included participants who tested negative in the confirmatory genetic test and had no family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Participants from the third group were referred to a genetic counselor for reassurance, with no further action required.

The surveillance strategies at the cancer genetics program were guided by local protocols and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines [19]. The program offered two breast risk-reduction strategies. The first strategy involved high-risk surveillance for women, including clinical breast examinations and alternating MRI and mammogram radiological imaging every six months. The second option included risk-reducing bilateral mastectomies with immediate breast oncoplastic surgeries. For men, high-risk surveillance included clinical breast examinations, regular prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing at defined intervals, digital rectal examinations, and imaging as needed.

For ovarian cancer, participants were offered either surveillance with pelvic or transvaginal ultrasounds and CA125 tumor marker testing or risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies, based on patient preference and after the completion of family planning.

2.5. Assessment of Acceptability and Adherence Rates

To evaluate the acceptability and adherence to the cancer surveillance and clinical intervention for BRCA1/2 carriers, clinical and radiological data were collected from participants’ medical records at three time points: at the uptake of surveillance (defined as the first surveillance following the genetic confirmatory test), and then at 12 and 24 months after enrollment in the pilot study. In this study, surveillance data referred to HMC-EMRs for breast, ovarian, or prostate cancer, including clinical, radiological, and tumor marker tests, which were recorded in real time (or near real time).

Acceptability for surveillance was defined as the proportion of eligible participants who were invited to the study and underwent clinical assessment or testing at the uptake of surveillance. Adherence was assessed by measuring the prevalence of participants who remained current with radiological testing at both 12 and 24 months after enrolling in the pilot study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.2). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Continuous variables were reported using the median with interquartile range (IQR). To analyze acceptability and adherence, proportions and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a one-proportion Z-test.

3. Results

3.1. Recontact and Return of BRCA1/2 Results

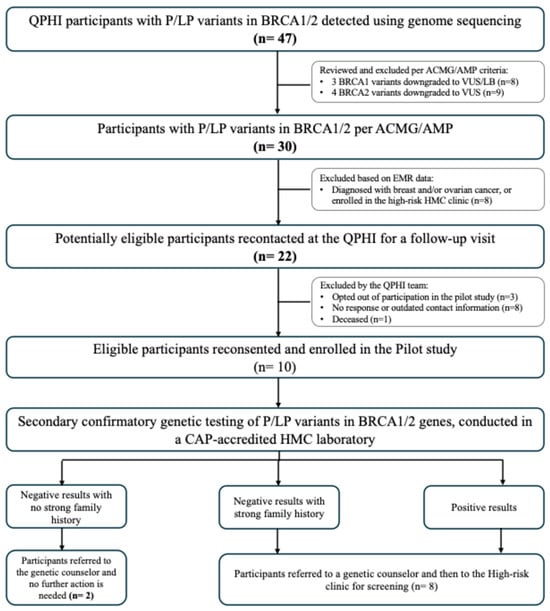

A description of the workflow design and the number of participants at each stage is illustrated in Figure 1. Initially, we identified 47 genotype-positive participants (GPPs) carrying 22 P/LP variants in the BRCA1/2 genes. These included 10 variants found in BRCA1 (carried by 24 GPPs) and 12 variants in BRCA2 (carried by 23 GPPs) (Supplementary Table S1). All 47 participants opted for recontact as part of their informed consent process. Saad and colleagues initially classified three BRCA1 variants (in eight GPPs) and four BRCA2 variants (in nine GPPs) as P/LP. However, a subsequent review, based on ACMG/AMP guidelines, downgraded these variants to variants of uncertain significance (VUS) or likely benign. As a result, 17 participants carrying these variants were excluded from the list of potentially eligible participants.

Figure 1.

Results from piloting the return of BRCA1/2 actionable findings workflow.

The review of EMR data led to the exclusion of eight more participants due to a prior diagnosis of breast or ovarian cancer, or enrollment in the high-risk medical oncology clinic. Of the 22 potentially eligible participants, 12 were further excluded for the following reasons: opting out of the pilot study (n = 3), failure to respond or outdated contact information (n = 8), and confirmation of death at the time of recontact (n = 1). The remaining 10 eligible participants reconsented and enrolled in the pilot study.

3.2. Validated BRCA1/2 Actionable Findings

We included ten participants in the pilot study, carrying six variants. Four variants were identified in BRCA1 and two in the BRCA2 gene (Table 1). In BRCA1, two participants were found to carry the c.4787C>A (p.Ser1596Ter) variant, which was validated through confirmatory Sanger sequencing at the HMC laboratory. Additionally, two participants (siblings, #4 and #10) were confirmed to carry the c.1365dup (p.Ile456fs), classified as likely pathogenic, while another participant carried the c.4065_4068del (p.Asn1355fs) variant, classified as pathogenic, in the BRCA1 gene. Additionally, Sanger sequencing confirmed the pathogenic variant c.4211_4215del (p.Ser1404Ter) in two BRCA2 participants, and the likely pathogenic variant c.-39-1G>C in one participant.

Table 1.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 validated genetic findings.

The Sanger sequencing test confirmed the presence of the c.4096+1G>C variant in BRCA1 carried by two GPPs (participants #6 and #7). However, the clinical scientist team reclassified this variant as VUS because computational analysis predicted that c.4096+1G>C would likely disrupt the natural splice donor site of intron 11 in BRCA1, but this prediction was not supported by published functional studies. Therefore, its clinical significance remained uncertain at the time of analysis.

3.3. Clinical Implications of BRCA1/2 Genetic Findings

The ten pilot study participants (six females and four males) had a median age of 48 years (IQR: 40.5–56) (Table 2). Only four participants (including two siblings, #4 and #10) reported a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer at the time of enrollment. Detailed information on family history and participant pedigrees is provided in Supplementary Figure S1. All ten participants underwent clinical-grade Sanger sequencing, and their results were returned by the genetic counselor. None of the participants requested a referral to the HMC psychiatric department for anxiety management.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the pilot cohort.

Among the ten eligible participants in the pilot study, two female participants (#6 and #7) had their results validated through Sanger sequencing and reclassified as VUS. Consequently, the genetic counselor addressed their general risk for breast and ovarian cancer and educated them on breast cancer screening through the national program. The remaining eight participants had their P/LP variants validated at the HMC laboratory (five GPPs in BRCA1 and three GPPs in BRCA2) and were referred to the cancer genetics and high-risk surveillance program. None of the pilot study participants had a negative confirmatory genetic test alongside a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

At the cancer genetics and high-risk surveillance program, risk-reducing strategies were offered. Among the eight participants with confirmed BRCA1/2 P/LP variants, four males (participants #1, 2, 3, and #8) were offered surveillance that included breast examination and imaging, as well as follow-ups for prostate cancer at the urology–oncology department, which involved blood tests and clinical assessments. Three female participants (# 4, #9, and #10) were offered breast cancer surveillance, which included alternating breast MRI and mammography or ultrasound, in addition to ovarian cancer surveillance, which involved pelvic ultrasound and CA-125 blood tests. Participant #5 underwent breast cancer surveillance; however, she opted for prophylactic BSO, which revealed an early-stage ovarian cancer (high-grade invasive serous carcinoma of the fallopian tube with serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, FIGO stage IA). This was followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with excellent clinical outcomes, and the patient has remained disease-free post-surgery, with no recurrence reported at her last follow-up.

Genetic counseling was offered to all first-degree relatives of the index cases at HMC. Twenty family members agreed to undergo cascade genetic testing via Sanger sequencing and were found to carry P/LP variants in the BRCA1/2 genes. They were subsequently offered personalized risk-reducing strategies. All 13 female family members underwent breast cancer surveillance, which included imaging every six months (mammography and MRI), in addition to ovarian cancer surveillance through pelvic or transvaginal ultrasounds with CA125 testing, based on factors such as age, patient preference, and family planning status. One family member (sister of index case #5) chose to undergo a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and was found to have early-stage uterine cancer (serous endometrioid carcinoma). All seven male carriers underwent breast cancer surveillance through clinical examination and prostate cancer surveillance, which included PSA testing and clinical examinations, with imaging performed as indicated.

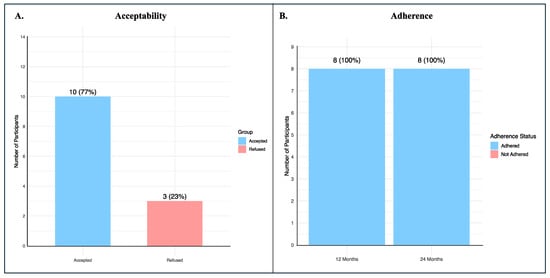

3.4. Participants’ Acceptability and Adherence Rates

A total of 13 potential participants were seen at QPHI, where the pilot study was introduced, and consent for variant validation through Sanger sequencing was requested. Only three participants refused to participate in the pilot study. The acceptability rate at the uptake surveillance was 0.77 (95% CIs: 0.54–0.998) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Acceptability and adherence of BRCA1/2 participants. (A) The proportion of individuals who agreed to participate in the pilot study following introduction at QPHI, with the calculated acceptability rate; (B) The proportion of enrolled participants who remained on surveillance at 12 and 24 months after uptake, demonstrating full adherence at both time points.

We calculated the proportion of participants who were currently on surveillance 12 and 24 months after the uptake surveillance, and the adherence rate was 100% at both time points (Figure 2B).

4. Discussion

Genome sequencing can offer a wide range of health benefits to participants in research studies by returning medically actionable results and offering the early identification of at-risk individuals, therefore allowing for personalized risk-reducing strategies and reducing morbidity and mortality for high-risk groups [20,21]. Limited resources and capacity represent challenges for effective clinical management, highlighting the need for structured workflows to maximize the health benefits of identifying medically actionable findings [16,22,23]. A growing number of national genomics programs, especially from underrepresented populations, are providing opportunities to guide the system-wide changes required for the clinical implementation of genomics research [24].

A previous study in Qatar evaluated the impact of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic mutations on breast cancer aggressiveness in carriers versus non-carriers, involving 82 women diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 50 or younger [25]. The results suggested that BRCA1/2 mutations were associated with breast cancer that exhibited more aggressive behavior, particularly in younger age groups. Additionally, patients with these mutations tended to present with more advanced stages of disease compared to those without pathogenic mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes, who exhibited a less aggressive cancer. These findings emphasized the importance of establishing a tailored workflow for participants in the population-based Qatar biobank to bridge the gap between research and clinical care for participants carrying P/LP variants in BRCA1/2 genes and to ensure appropriate support and disclosure of these findings to participants.

In this pilot study, we established a return of results workflow for BRCA1/2 medically actionable genetic findings emerging from the research-grade whole-genome sequencing of 6142 participants. This workflow was developed sequentially to assess the feasibility of integrating genetic testing into routine clinical high-risk surveillance for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer, and to address potential challenges. Using this designed workflow, which integrates multidisciplinary approaches, including genomic data analysis, variant classification and validation, participant recontact, and proper counseling, we were able to return medically actionable BRCA1/2 findings to ten participants and to observe how these findings can influence their management plans and future risk.

A key contributor to the success of the pilot was the inclusion of structured pre- and post-test genetic counseling. The pre-test sessions ensured that participants received clear and accessible explanations about the purpose, scope, benefits, and limitations of the genetic testing, enabling informed decision-making and reducing uncertainty. Post-test counseling provided individualized interpretation of results, answered participants’ questions, and guided appropriate clinical follow-ups. Importantly, the post-test counseling also included counseling on cascade genetic testing for at-risk relatives. This led to the testing and identification of 20 family members carrying BRCA1/2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, demonstrating the program’s meaningful clinical impact at both the patient and family levels.

The acceptability rate for returning BRCA1/2 genetic information and referring to a high-risk genetic clinic among pilot study participants was 77% (95% CIs: 0.46–0.94). Although all participants initially consented to recontact, our results highlighted the importance of tailored consent procedures that clearly inform participants about the possibility of receiving actionable SFs and allow them to opt in or out of such disclosure [26]. This is especially crucial in research settings, where participants may not anticipate receiving clinical information. Furthermore, the integration of genomic-based programs into healthcare systems in Middle Eastern populations requires a careful consideration of various ethical and social issues [27].

In this pilot study, 10 high-risk participants were identified (6 females, 4 males); 2 female participants had their variants reclassified as VUS. The remaining eight participants had P/LP BRCA1/2 variants confirmed and were referred to the cancer genetics and high-risk surveillance program. Most of the participants opted for increased surveillance rather than prophylactic surgeries due to several factors, including age, gender, and marital status. One female participant opted for prophylactic BSO and was found to have early-stage ovarian cancer (high-grade invasive serous carcinoma of the fallopian tube with serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, FIGO stage IA), which is a common ovarian cancer subtype associated with the BRCA1 gene [28]; this was followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with excellent clinical outcomes, and the patient has remained disease-free post-surgery, with no recurrence reported at her last follow-up.

At the cancer genetics program, cascade testing of the index family members was offered, with a full acceptance rate in which a total of 20 positive family members were identified. All family members opted for increased surveillance, except for one family member (sister of index case who was found to have early-stage ovarian cancer post-prophylactic BSO) who chose to undergo a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and was found to have early-stage uterine cancer, specifically serous endometroid carcinoma. Interestingly, serous endometroid carcinoma of the uterus has also been reported in relation to pathogenic variants in the BRCA1 gene [29]. These results underscore the critical importance of the early identification of high-risk individuals, enabling timely interventions that can lead to the early detection or even prevention of life-threatening cancers such as ovarian cancer. One of the key challenges addressed in the present workflow was the interpretation and classification of BRCA1/2 variants. In concordance with the ACMG/AMP classification system [18], we downgraded the classification of seven P/LP variants that were identified and classified by Saad and colleagues to VUS or LB, resulting in the exclusion of 17 participants at the initial filtering step. Moreover, the clinical scientist team reclassified the BRCA1 c.4096+1G>C variant to VUS, providing information on its limited pathogenicity. Leveraging standardized guidelines, such as the ACMG/AMP criteria, and incorporating population-specific variant databases helped reduce uncertainty in variant interpretation and enabled focusing on truly actionable findings.

Despite the success of this workflow and its promising outcomes, the challenges associated with implementing such a process must be acknowledged. These include ethical and financial considerations, as well as long-term follow-up and integration with national healthcare systems, which remain key obstacles for future incorporation. Additionally, participant preferences regarding recontact and data sharing must continue to be respected and dynamically managed. From a clinical perspective, implementing risk-reducing strategies for unaffected individuals carrying genetic mutations imposes a substantial burden on clinical services, including radiology, surgery, diagnostic molecular laboratories, and psychological support, not only for participants but also their families. The newly established CCPMG center can facilitate the multidisciplinary coordination of these services, ensuring comprehensive care through tailored interventions, counseling, and follow-ups within an integrated genomic and clinical framework. A limitation of our pilot study is that we did not assess the economic cost-effectiveness of the proposed framework of returning BRCA1/2 actionable findings to biobank participants. All QPHI participants received care at no charge through the biobank and the HMC hospital; therefore, the costs associated with implementing the framework were not evaluated. Further studies should consider the financial implications of such a design, including the potential effect on downstream intervention, feasibility, and sustainability of returning all medically actionable genetic findings. Additionally, in this pilot phase, we intentionally limited our analysis to BRCA1 and BRCA2 to assess the feasibility of returning research-derived, rather than clinically generated, results to biobank participants. Although other genes such as PALB2, PTEN, and TP53 are also associated with hereditary breast cancer, evaluating them was beyond the scope of this initial feasibility assessment. In routine clinical care, individuals with a strong family history typically undergo multigene panel testing that includes these moderate- and high-risk genes; in our study, the two participants (#6 and #7) had already received such clinical testing, and their negative results were part of their clinical evaluation rather than the research return process we aimed to evaluate. We acknowledge the importance of these additional genes and note that future phases of this project will expand the analysis to include the broader set of ACMG-recommended secondary findings genes.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of a structured workflow for the return of BRCA1/2 medically actionable findings represents a robust step toward translating genomic data into clinical intervention in biobank settings. This model lays the groundwork for the broader application of returning medically actionable SFs, facilitating a paradigm shift in translating precision medicine to improve the health outcomes of patients and their families.

Our initiative bridges the gap between genomic research and clinical application, illustrating the promise of personalized medicine in improving health outcomes. Building on these results, we recommend extending this translational pathway to other actionable gene mutations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines13123047/s1.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: S.B.A.B., S.I., and W.A.-M.; development of methodology: S.B.A.B., W.A.-M., and M.A.; recruitment and follow-up of participants: T.F., M.E., H.F., H.A., M.S., N.A., R.A., and H.H.; analysis and interpretation of results: F.A., S.B.A.B., and W.A.-M.; writing of the manuscript: H.H. and A.E.; critically reviewed the manuscript: R.M.B., L.C., and S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The pilot study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and in accordance with ethical standards and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Hamad Medical Corporation under protocol number MRC-01-20-1148, approval date 19 December 2018, and from the Qatar Biobank Institutional Review Board under protocol number QF-QBB-RES-ACC-0241, approval date 1 January 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the QPHI. However, access to these data is restricted, as they were used under license QF-QBB-RES-ACC-0241 for the purposes of the current research and are not publicly accessible. Data may be made available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the approval of the QBB Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the medical professionals and staff at Hamad Medical Corporation and Qatar Precision Health Institute for their invaluable support in this study. We are especially grateful to Niloofar Allahverdi, Loveshy Sanoj, Heba Rashid Yasin, Mustafa Ali Nasr, Noha Magdy Elkousy, Nadia Hassan Sheikh, Jingxuan Shan, and Sirin Walid Abuaqel for their dedication and commitment to high standards that contributed to the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HBOC | Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome |

| P | Pathogenic |

| LP | Likely Pathogenic |

| VUS | Variants of Uncertain Significance |

| QPHI | Qatar Precision Health Institute |

| GPPs | Genotype-Positive Participants |

| HMC | Hamad Medical Corporation |

| GS | Genome Sequencing |

| SFs | Secondary Findings |

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| NCCCR | National Center for Cancer Care and Research |

| CCPMG | Centre of Clinical Precision Medicine and Genomics |

| EMRs | Electronic Medical Records |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

References

- Saelaert, M.; Mertes, H.; Moerenhout, T.; De Baere, E.; Devisch, I. Criteria for reporting incidental findings in clinical exome sequencing—A focus group study on professional practices and perspectives in Belgian genetic centres. BMC Med. Genom. 2019, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Abul-Husn, N.S.; Amendola, L.M.; Brothers, K.; Chung, W.K.; Gollob, M.H.; Gordon, A.S.; Harrison, S.M.; Hershberger, R.E.; et al. ACMG SF v3.1 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, F.E.; Murray, M.F.; Overton, J.D.; Habegger, L.; Leader, J.B.; Fetterolf, S.N.; O’dUshlaine, C.; Van Hout, C.V.; Staples, J.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, C.; et al. Distribution and clinical impact of functional variants in 50,726 whole-exome sequences from the DiscovEHR study. Science 2016, 354, aaf6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, L.; Sincan, M.; Markello, T.; Adams, D.R.; Gill, F.; Godfrey, R.; Golas, G.; Groden, C.; Landis, D.; Nehrebecky, M.; et al. The implications of familial incidental findings from exome sequencing: The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program experience. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 16, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorschner, M.O.; Amendola, L.M.; Turner, E.H.; Robertson, P.D.; Shirts, B.H.; Gallego, C.J.; Bennett, R.L.; Jones, K.L.; Tokita, M.J.; Bennett, J.T.; et al. Actionable, pathogenic incidental findings in 1,000 participants’ exomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 93, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.M.; Dorschner, M.O.; Robertson, P.D.; Salama, J.S.; Hart, R.; Shirts, B.H.; Murray, M.L.; Tokita, M.J.; Gallego, C.J.; Kim, D.S.; et al. Actionable exomic incidental findings in 6503 participants: Challenges of variant classification. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, E.; Cottrell, C.E.; Davidson, N.O.; Gurnett, C.A.; Heusel, J.W.; Stitziel, N.O.; Chen, L.-S.; Hartz, S.; Nagarajan, R.; Saccone, N.L.; et al. Identification of medically actionable secondary findings in the 1000 genomes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Abul-Husn, N.S.; Amendola, L.M.; Brothers, K.; Chung, W.K.; Gollob, M.H.; Gordon, A.S.; Harrison, S.M.; Hershberger, R.E.; et al. ACMG SF v3.2 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaff, C.L.; Winship, I.M.; Forrest, S.M.; Hansen, D.P.; Clark, J.; Waring, P.M.; South, M.; Sinclair, A.H. Preparing for genomic medicine: A real world demonstration of health system change. npj Genom. Med. 2017, 2, 16, Erratum in npj Genom. Med. 2017, 31, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.-A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.-J.; Jervis, S.; Van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, A.M.; Armstrong, K. The Role of Testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Cancer Prevention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1023–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Cancer Observatory|Globocan 2022 (version 1.1)—08.02.2024. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/634-qatar-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Al-Bader, S.B.; Alsulaiman, R.; Bugrein, H.; Ben Omran, T.; Abbaszadeh, F.; Bakheet, N.; Kusasi, S.A.; Abdou, N.; Solomon, B.D.; Ghazouani, H. Cancer genetics program: Follow-up on clinical genetics and genomic medicine in Qatar. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2018, 6, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbarek, H.; Gandhi, G.D.; Selvaraj, S.; Al-Muftah, W.; Badji, R.; Al-Sarraj, Y.; Saad, C.; Darwish, D.; Alvi, M.; Fadl, T.; et al. Qatar genome: Insights on genomics from the Middle East. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thani, A.; Fthenou, E.; Paparrodopoulos, S.; Al Marri, A.; Shi, Z.; Qafoud, F.; Afifi, N. Qatar Biobank Cohort Study: Study Design and First Results. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Mokrab, Y.; Halabi, N.; Shan, J.; Razali, R.; Kunji, K.; Syed, N.; Temanni, R.; Subramanian, M.; Ceccarelli, M.; et al. Genetic predisposition to cancer across people of different ancestries in Qatar: A population-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.D.; Huang, K.-L.; Weerasinghe, A.; Mashl, R.J.; Gao, Q.; Rodrigues, F.M.; A Wyczalkowski, M.; Ding, L. CharGer: Clinical Characterization of Germline variants. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.B.; Pal, T.; Berry, M.P.; Buys, S.S.; Dickson, P.; Domchek, S.M.; Elkhanany, A.; Friedman, S.; Goggins, M.; Hutton, M.L.; et al. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 2021, 19, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Lester Kirchner, H.; Schwartz, M.L.B.; Kelly, M.A.; Schmidlen, T.; Jones, L.K.; Hallquist, M.L.; Rocha, H.; Betts, M.; Schwiter, R.; et al. Clinical outcomes of a genomic screening program for actionable genetic conditions. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul-Husn, N.S.; Soper, E.R.; Braganza, G.T.; Rodriguez, J.E.; Zeid, N.; Cullina, S.; Bobo, D.; Moscati, A.; Merkelson, A.; Loos, R.J.F.; et al. Implementing genomic screening in diverse populations. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfatih, A.; Saad, C.; The Qatar Genome Program Research Consortium; Mifsud, B.; Mbarek, H. Analysis of 14,392 whole genomes reveals 3.5% of Qataris carry medically actionable variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfatih, A.; Mifsud, B.; Syed, N.; Badii, R.; Mbarek, H.; Abbaszadeh, F.; The Qatar Genome Program Research Consortium; Estivill, X. Actionable genomic variants in 6045 participants from the Qatar Genome Program. Hum. Mutat. 2021, 42, 1584–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, C.; Haas, M.A.; Al Muftah, W.A.; Annan, R.B.; Green, E.D.; Lundgren, B.; Scott, R.H.; Stark, Z.; Tan, P.; North, K.N.; et al. The expanding global genomics landscape: Converging priorities from national genomics programs. Am. J. Human. Genet. 2025, 112, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujassoum, S.M.; Bugrein, H.A.; Sulaiman, R.A. Genotype and Phenotype Correlation of Breast Cancer in BRCA Mutation Carriers and Non-Carriers. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2017, 9, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.E.; Wolf, S.M.; Kuczynski, K.J.; Joffe, S.; Sharp, R.R.; Parsons, D.W.; Knoppers, B.M.; Yu, J.-H.; Appelbaum, P.S. The Challenge of Informed Consent and Return of Results in Translational Genomics: Empirical Analysis and Recommendations. J. Law. Med. Ethics 2014, 42, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Tayoun, A.N.; Fakhro, K.A.; Alsheikh-Ali, A.; Alkuraya, F.S. Genomic medicine in the Middle East. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, M.; Borràs, E.; Castellví, J.; Méndez, O.; Sánchez-Iglesias, J.L.; Pérez-Benavente, A.; Gil-Moreno, A.; Sabidó, E.; Santamaria, A. BRCA1 mutations in high-grade serous ovarian cancer are associated with proteomic changes in DNA repair, splicing, transcription regulation and signaling. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparri, M.L.; Bellaminutti, S.; Farooqi, A.A.; Cuccu, I.; Di Donato, V.; Papadia, A. Endometrial Cancer and BRCA Mutations: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).