Abstract

Background/Objectives: Alopecia areata (AA) is a common, noncicatricial autoimmune hair loss disorder characterized by relapsing inflammation and breakdown of hair follicle immune privilege. Increasing amounts of evidence suggest that pyroptosis, a lytic and inflammatory form of programmed cell death mediated by gasdermins and inflammasome activation, may play a role in AA pathogenesis. This review aims to synthesize current data on the molecular mechanisms linking inflammasome-driven pyroptosis with AA and to highlight emerging therapeutic opportunities. Methods: A comprehensive literature review was conducted focusing on mechanistic studies, ex vivo human scalp models, murine AA models, and interventional clinical data. A structured system of Levels of Evidence (LoE) and standardized nomenclature for experimental models was applied to ensure transparency in evaluating the role of pyroptosis and treatment strategies in AA. Results: Available evidence indicates that outer root sheath keratinocytes express functional inflammasome components, including NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3), adaptor-apoptosis-associated-speck-like protein (ASC), and caspase-1, and contribute to interleukin (IL)-1β release and pyroptotic cell death. Mitochondrial dysfunction, mediated by regulators such as PTEN and PINK1, amplifies NLRP3 activation and cytokine secretion, linking mitophagy impairment with follicular damage. Animal and human biopsy studies confirm increased inflammasome activity in AA lesions. Therapeutic approaches targeting pyroptosis include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, biologics, Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors, mesenchymal stem cell therapy, natural compounds, and inflammasome inhibitors such as MCC950. While some agents demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials, most strategies remain at preclinical or early clinical stages. Conclusions: Pyroptosis represents a critical mechanism driving hair follicle structural and functional disruption and immune dysregulation in AA. By integrating evidence from molecular studies, disease models, and early clinical data, this review underscores the potential of targeting inflammasome-driven pyroptosis as a novel therapeutic strategy.

1. Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a noncicatricial autoimmune hair loss disorder. The degradation of the hair follicle’s immune privilege results in chronic lymphocytic inflammation [1]. It can be clinically distinguished by sharply demarcated patches of alopecia on the scalp; however, sometimes it can progress to extensive or even complete hair loss. The prevalence of AA is around 2% [2,3,4]. The illness is characterized by relapsing course and is associated with an increased risk of other comorbidities such as vitiligo, autoimmune hypothyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus, and psoriasis [5,6,7]. Although the pathogenesis of AA is not fully understood, psychological stress is considered as a potential environmental trigger. However, stress alone cannot explain all the cases, as AA sometimes affects newborns and infants [8,9]. Some additional factors such as infections or toxic exposures can also be involved in the autoimmune dysregulation and be involved in the pathogenesis of AA [10].

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of programmed cell death mediated by proteins called gasdermins, which are involved in pore formation, and are stimulated by inflammasome activation [11]. Unlike apoptosis, which is not associated with immunological events, in pyroptosis, proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 are released [11]. Increasing evidence suggests that pyroptosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including AA, becoming an interesting therapeutic target [12,13].

Despite numerous studies on the topic, the pathophysiology of AA remains only partially understood. Current therapies are often nonspecific, with variable efficacy and risk of relapse. Pyroptosis has emerged as a potential mechanism, which underlies the follicular functional disruption and provokes the inflammation in AA [13]. However, this aspect of the disease has received little attention in the literature and, at present, it remains mainly a hypothesis-generating concept. To date, no comprehensive review has analyzed the available evidence on the role of pyroptosis in AA. This review aims to fill this gap by examining the molecular links between inflammasome activation, pyroptotic cell death, and the immunopathogenesis of AA, and tries to open new possibilities in the therapy for treating AA. Nevertheless, it should be noted that this review serves more as a theoretical model, which provides a conceptual framework for future studies.

2. Pyroptosis—A Lytic and Inflammatory Type of Programmed Cell Death

The balance between cellular proliferation and death is fundamental for maintaining tissue homeostasis in multicellular organisms [12]. There are two types of cell death: non-programmed or programmed cell death (PCD) [12]. Pyroptosis is a form of programmed cell death which initially was regarded as a subtype of apoptosis. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that pyroptosis is mechanistically different [14,15]. While apoptosis is characterized by nuclear condensation, membrane integrity, and controlled breakdown of cellular components, pyroptosis involves pore formation in the plasma membrane, cellular swelling, rupture, and the release of cytoplasmic content [16,17]. This uncontrolled discharge of molecules, particularly IL-1β and IL-18, enhances inflammation and activates innate and adaptive immune pathways [18,19].

The discovery of gasdermin D (GSDMD) was a milestone in understanding the molecular basis of pyroptosis [20]. Cleavage of GSDMD by caspase-1 releases its N-terminal fragment, which inserts into membranes and generates pores, which drives cell lysis [20,21]. The human gasdermin family includes six members (GSDMA, GSDMB, GSDMC, GSDMD, GSDME/DFNA5, and PJVK/DFNB59) [12]. After activation by microbial signals or immune proteases such as caspases and granzymes, the inhibitory interaction is relieved, enabling the N-terminal fragment to perforate membranes [22,23]. Pyroptosis is closely associated with the innate immune system. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) detect microbial products (PAMPs), host-derived danger signals (DAMPs), or stress-induced alterations, initiating signaling cascades that upregulate cytokines and mobilize protective responses, such as autophagy, to eliminate damaged organelles [24]. One of the best-studied signaling complexes is the inflammasome, a multiprotein structure typically composed of a sensor (i.e., NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3)), the adaptor apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruiting domain (ASC), and the effector protease caspase-1 [11,12]. Upon activation by infection or cellular stress, caspase-1 undergoes autoproteolysis, leading to the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, as well as the cleavage of GSDMD, which results in pore formation and finally pyroptosis [11].

Physiologically, pyroptosis serves as a host defense mechanism by eliminating infected cells and alarming the immune system. However, when dysregulated or excessive, it causes uncontrolled inflammation, extensive cell loss, and tissue damage, contributing to the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

3. Signaling Pathways in Pyroptosis

Currently, four distinct signaling pathways are described to trigger pyroptosis: the canonical inflammasome pathway, the non-canonical inflammasome pathway, pathways driven by granzymes and caspase-dependent apoptotic signaling [12]. The second and the last pathway appears to have minimal relevance to the pathogenesis of AA and will therefore not be discussed in this review. Regardless of the upstream trigger, the execution phase is carried out by gasdermin proteins, which must undergo proteolytic cleavage by caspases or granzymes to form membrane pores [12]. Caspases can be broadly grouped into two functional categories: inflammatory and apoptotic [25]. The inflammatory subgroup (caspase-1, -4, -5, and -11) is central to the innate immune response, since it not only initiates pyroptotic cell death to limit intracellular pathogen survival but also processes precursor cytokines into their active forms [26]. Within the canonical pathway, caspase-1 is recruited and activated by inflammasome complexes. In contrast, caspases-4, -5, and -11 omit such complexes, because they are directly activated through binding to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [12]. Apoptotic caspases are known for coordinating the controlled degradation of cells during apoptosis [27]. However, they also have been found to cleave gasdermins, which links apoptosis machinery to pyroptotic responses [27].

3.1. Canonical and Non-Canonical Inflammasome Pathway

The first described signaling pathway of pyroptosis was the canonical inflammasome pathway. In this mechanism, microbial components, PAMPs, are recognized by PRRs, such as toll-like receptors and members of the NOD-like receptor family (NLRP, including NLRP1, NLRP3, and NLRC4) [24,28,29]. Besides PAMPs, cells under stress or damage release endogenous molecules called DAMPs, which are also detected by PRRs. These receptors are integral components of the inflammasome complex [24]. Their role is to sense danger signals and initiate inflammation. Well-characterized inflammasome sensors responds to different triggers such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, uric acid crystals, reactive oxygen species, ATP, or double-stranded DNA of microbial or viral origin [30]. Once a receptor is engaged, pro-caspase-1 is recruited and activated through a process of autoproteolysis. Caspase-1 then converts pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature forms and cleaves gasdermin D, whose N-terminal fragment forms membrane pores in the cell [31].

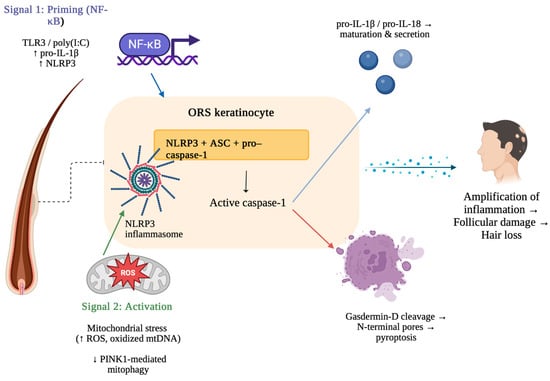

The Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway represents a central regulatory mechanism in pyroptosis, because it controls the transcriptional priming of inflammasome components [32]. Following the recognition of PAMPs or DAMPs by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), intracellular signaling cascades are initiated through adapter proteins [6,33]. This leads to the activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which drives the expression of key inflammasome components, including NLRP3, pro-IL-1β, and pro-IL-18 (Figure 1). This “priming step” (signal 1) prepares the cell for inflammasome structure by elevating protein levels and inducing post-translational modifications of NLRP3 (Figure 1) [34,35,36,37]. The following “activation step” (signal 2), triggered by additional PAMPs or DAMPs, then promotes the structure of the inflammasome complex, caspase-1 activation, and finally leads to pyroptotic cell death (Figure 1) [32].

Figure 1.

Mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in alopecia areata. Created in BioRender. Krajewski, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/3cl1t7i (accessed on 10 August 2025).

The process begins with Signal 1 (priming), in which NF-κB activation induced by TLR3 or poly (I:C) upregulates pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 expression in outer root sheath (ORS) keratinocytes. Signal 2 (activation) is triggered by mitochondrial stress, characterized by increased ROS and oxidized mtDNA together with impaired PINK1-mediated mitophagy, resulting in the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The inflammasome complex (NLRP3, ASC, pro–caspase-1) activates caspase-1, which promotes cleavage and secretion of IL-1β/IL-18 and cleavage of gasdermin D. Gasdermin D forms membrane pores, resulting in pyroptosis [38,39].

The non-canonical pathway acts independently of classical inflammasome formation. It is activated mostly by intracellular LPS from Gram-negative bacteria. This pathway has minimal relevance to pyroptosis in AA and therefore will not be discussed in this review.

3.2. Pyroptosis Triggered by Granzymes

Natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells release granzymes that enter target cells through pores formed by perforin [40,41,42]. Once inside, these proteases can cleave members of the gasdermin family and initiate pyroptosis, particularly in cancer cells. Granzyme A (GZMA), the most frequently occurring serine protease in this group, has long been associated with programmed cell death. However, now this protease is also known to regulate inflammatory responses by promoting the release of cytokines, thereby favoring pyroptosis [43]. For example, GZMA secreted by cytotoxic T cells has been shown to cleave GSDMB, enabling pore formation in the plasma membrane and triggering pyroptotic death in GSDMB-positive tumor cells [44]. Similarly, granzyme B (GZMB) from NK cells targets GSDME, cleaving it at the same site recognized by caspase-3 [45]. This cleavage release the N-terminal effector fragment of GSDME, which inserts into the membrane and drives cell lysis [40].

4. The Role of Pyroptosis in Alopecia Areata

In AA, loss of hair follicle immune privilege triggers a chronic, lymphocytic inflammation resulting in autoimmune disorder [1]. At the molecular level, hair follicles (HFs) are normally protected as immune-privileged sites. This state is maintained by the low expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules in the anagen bulb, which reduces recognition by CD8+ T cells. In addition, the local release of immunosuppressive mediators, i.e., transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), or IL-10 creates a specific environment, which can protect this privilege [4,46]. When this protection breaks down, hair follicles instead show upregulation of MHC class I and II molecules, induction of Natural Killer Group 2 Member D (NKG2D) ligands, and a decline in regulatory mediators such as TGF-β1, and IL-10 which all contribute to autoimmune inflammation [4,46,47].

In AA, there is widespread cytokine dysregulation involving Th1 (IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF), Th2 (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-17E, IL-31, IL-33), and Th17 (IL-17, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23) pathways. Elevated levels of IL-2, IL-12, IL-17, IL-17E, and TNF correlate with disease severity and duration, supporting the concept that inflammation associated with inflammasomes can be a central mechanism of follicular structural and functional disruption [48]. Additionally, excessive production of proinflammatory mediators, including IFN-I and IFN-II, IL-15, and interferon-inducible chemokines (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11), plays a key role by recruiting CXCR3+ effector T cells to the peribulbar region, where autoreactive lymphocytes attack follicular epithelial cells [4,47]. CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells further intensify this process by producing IFN-γ via the JAK1-STAT1 and JAK2-STAT2 pathways. IFN-γ, in turn, stimulates IL-15 secretion in follicular epithelial cells. Then, IL-15 signals back to CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells through JAK1 and JAK3, strengthening IFN-γ production and creating a positive feedback loop [4,49,50].

It is worth underlining that IL-15 is considered to be one of the most important interleukins in the pathogenesis of AA [51,52]. Higher serum levels of IL-15 have been found in AA patients compared to healthy controls and are correlated with a more severe course of the disease and worse prognosis [52]. Additionally, IL-15 activates key immune cells involved in the pathogenesis of AA, and its recombinant form can promote human scalp hair follicle growth and reduce apoptosis in hair matrix keratinocytes ex vivo [53]. Moreover, it was found that supplementation with the recombinant form of IL-15 can prevent IFN-γ-induced collapse of hair follicle immune privilege, supporting the potential therapeutic role of IL-15 [53].

Previous studies demonstrated that IL-1β is notably elevated in AA lesions, which may disrupt the normal hair cycle and thereby contribute to hair follicle degeneration [4]. Of note, keratinocytes, which are not professional immune cells, represent a significant source of IL-1 in the skin [46,54,55]. These cells, particularly those within the outer root sheath (ORS) of hair follicles, appear to function as immunocompetent cells that actively participate in the autoinflammatory processes characteristic of AA [56].

The study by Shin et al. [56] provided the first direct evidence that ORS cells constantly express inflammasome components, including NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, and were capable of forming fully functional inflammasomes. In scalp biopsies from AA patients, immunohistochemistry revealed strong expression of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 in the ORS of hair follicles as well as in infiltrating immune cells [56]. Yet, these proteins were only weakly expressed in normal scalp skin [56]. Similarly, in a C3H/HeJ mouse model of AA, inflammasome proteins were highly upregulated in ORS cells and inflammatory infiltrates of affected skin [57]. These findings demonstrated that ORS cells themselves, rather than immune infiltrates alone, can act as sources of cytokines associated with pyroptosis. This expands the concept of AA from being purely a T cell-driven autoimmune disease to also autoinflammatory mechanisms driven by the innate immune system [57].

Furthermore, stimulation of ORS cells with poly(I:C)—a synthetic RNA analog and TLR3 ligand—significantly increased mRNA and protein levels of inflammasome components (NLRP3, ASC, CASP1, IL1B) [56]. Additionally, it increased secretion of active caspase-1 and IL-1β and promoted co-localization of NLRP3 with ASC [56]. Importantly, silencing caspase-1 or NLRP3 using microRNA notably reduced poly(I:C)-induced IL-1β release, confirming that cytokine secretion depended on inflammasome activation [56]. Of note, the NF-κB pathway was identified as a key mediator of poly(I:C)-induced IL-1β production in cultured ORS cells [32].

Moreover, recent work has revealed that mitochondrial quality control mechanisms are also linked to inflammasome activity in AA. Specifically, PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) and PINK1 (PTEN-induced kinase 1), a key regulator of mitophagy, have been shown to influence pyroptosis through their effects on mitochondrial function [58]. In AA scalp tissue and IFN-γ/poly(I:C)-stimulated ORS cells, mitochondrial DNA damage and elevated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) were observed [58]. Both of them promote NLRP3 activation [58]. Activating PINK1-driven mitophagy reduced inflammasome activity, while silencing PINK1 increased NLRP3 signaling and cytokine release [58]. These findings highlight PTEN/PINK1-driven mitophagy as a key negative regulator of pyroptosis in ORS cells and show that mitochondrial dysfunction can be a potential therapeutic target in AA [58]. The comparison of classical and pyroptosis-driven mechanism in AA is given in Table 1 and key cytokines and pathways are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of the classical immune mechanism and pyroptosis-driven mechanism in alopecia areata.

Table 2.

Summary of key cytokines and pathways involved in AA.

Although these findings provide valuable insights into the potential role of pyroptosis in AA, the current evidence remains limited and, largely hypothetical. Not all proposed mechanisms are proven by strong experimental and clinical data, and still the precise mechanism of pyroptosis is not fully understood. Therefore, these concepts should be viewed as early, hypothesis-generating ideas rather than established pathomechanisms. Clarifying these facts can be crucial in developing new therapies.

5. New Therapies of AA Based on Pyroptosis and Future Directions

Pyroptosis seems to be one of the mechanisms inducing hair follicle damage and maintaining the autoimmune response in AA, which opens up new perspectives for treatment strategies. Current research is focused on targeting pyroptosis and related inflammatory pathways, with the aim of reducing cytokine release and limiting inflammation.

To ensure a transparent evaluation of the strength of available data, we applied a custom, structured nomenclature of Levels of Evidence (LoE). The following categories were used:

- -

- LoE-H2: Interventional clinical data in humans, including randomized and non-randomized clinical trials. The study phase (e.g., phase II or III) is specified where applicable.

- -

- LoE-H1: Observational human data, such as analyses of patient biopsies, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), proteomics/serology, or immunohistochemistry (IHC).

- -

- LoE-A2: In vivo animal studies using AA-specific models (e.g., C3H/HeJ mice with spontaneous or graft-induced AA, humanized or xenograft AA models).

- -

- LoE-A1: In vivo animal studies using non-AA-specific hair growth or hair cycle models (e.g., C57BL/6 telogen-to-anagen induction), which assess follicular biology without autoimmune context.

- -

- LoE-X: Ex vivo human models, including organotypic skin cultures, isolated hair follicles, or other patient-derived tissue explants.

- -

- LoE-C: In vitro cellular studies, including cultured human outer root sheath (ORS) keratinocytes, keratinocyte lines, or co-culture systems.

The standardized nomenclature for experimental models was also applied. The following labels were used throughout the manuscript:

- -

- Model-AA-C3H, murine alopecia areata model (C3H/HeJ, spontaneous or graft-induced AA)

- -

- Model-HG-C57, murine hair growth model (C57BL/6, telogen-to-anagen induction, non-autoimmune)

- -

- Model-ORS-polyIC, cultured human outer root sheath keratinocytes stimulated with poly(I:C) ± IFN-γ/TNF

- -

- Model-Skin-ExVivo, human scalp skin organotypic cultures or biopsies maintained ex vivo

- -

- Model-Human-Biopsy, in vivo human scalp biopsy material

- -

- Model-Trial-AA, interventional clinical trial in patients with alopecia areata.

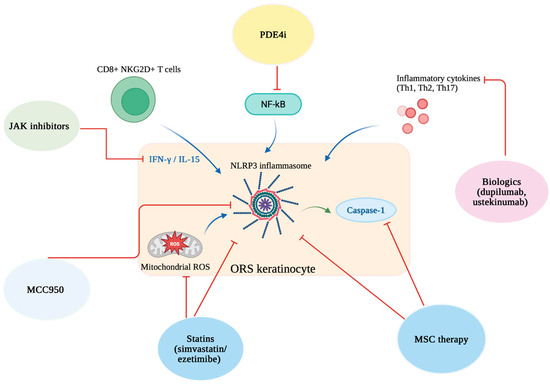

By using these two systems, we wanted to ensure that the review would be transparent, precise and reliable based on the available literature. The schematic effects of drugs on the different stages of pyroptosis are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of therapeutic strategies targeting different stages of pyroptosis in alopecia areata. Created in BioRender. Krajewski, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/gh3jl05 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

JAK inhibitors reduce IFN-γ/IL-15 signaling from CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells; PDE4 inhibitors block NF-κB activation; biologics (e.g., dupilumab, ustekinumab) suppress inflammatory cytokines; MCC950 inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome; statins (simvastatin/ezetimibe) reduce mitochondrial ROS; mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy limits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and caspase-1 activity in ORS keratinocytes.

5.1. AA-Specific Interventions

5.1.1. JAK Inhibitors (LoE-H2; Model-Trial-AA/LoE-A2; Model-AA-C3H)

Advances in the molecular understanding of AA have highlighted the importance of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in disease progression [4,59]. The JAK family includes JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, which transmit signals from cytokine receptors and lead to the phosphorylation of STAT. Then, STAT moves into the nucleus and activates the transcription of proinflammatory genes [60,61]. Cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-15, which are crucial to AA pathogenesis, depend on this pathway, which makes JAK inhibitors (JAKi) reliable therapeutic agents (Figure 2) [60,61]. Preclinical studies using the C3H/HeJ mouse model demonstrated that oral JAKi, including ruxolitinib and tofacitinib, could prevent and reverse AA, supporting their clinical potential [62,63,64].

Importantly, since IFN-γ-driven JAK-STAT activation prepares inflammasome components and induces IL-1β production, JAK inhibition may indirectly block pyroptotic pathways in hair follicle cells [65]. By reducing upstream cytokine signaling, JAKi lower the inflammatory environment required for inflammasome building and caspase-1 activation, which can potentially limit follicular damage induced by pyroptosis [65]. Although topical JAKi seem to reduce systemic adverse effects, their efficacy remains variable, and further studies are needed to clarify their role not only in immune modulation but also in the control of inflammasome-driven pyroptosis in AA [66,67].

The anti-inflammatory action of JAK inhibitors is relatively non-specific, as the targeted signaling pathways are shared by numerous cytokines [4,68]. Baricitinib is a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, and its efficacy and safety were confirmed in clinical trials: BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 [69,70]. Similarly, deuruxolitinib, which is also a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, achieved significant improvements in hair regrowth, as demonstrated in the THRIVE-AA1 trial [71]. The newest generation of JAK inhibitors, such as brepocitinib (JAK1/TYK2 inhibitor) and ritlecitinib (JAK3/TEC inhibitor), have improved selectivity and are under clinical investigation in AA [72,73]. Currently, the only two medications approved by the European Medicines Agency for alopecia areata are baricitinib for adults and ritlecitinib for individuals aged 12 years and older. In addition, in the United States, deuruxolitinib was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in July 2024 for adults.

Evidence for JAK inhibitors in AA ranges from AA-specific murine models to phase II and III clinical trials. This evidence positions JAKi as the most advanced pyroptosis-modulating strategy to date, and one of the most effective treatments for AA.

5.1.2. Biologics (LoE-H2/H1; Model-Trial-AA/Model-Human-Biopsy)

Biologic agents targeting the Th1, Th2, and Th17 axes may influence pathways leading to pyroptosis in AA (Figure 2) [4,74,75]. Cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-23 are known to strengthen JAK-STAT signaling and promote inflammasome activation. By blocking these cytokines, indirectly the level of IL-1β and IL-18 can be reduced and so can the pyroptotic cell death within hair follicles [74,75].

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4Rα and thereby blocks IL-4/IL-13 signaling, has demonstrated therapeutic activity in AA [76]. In a clinical trial, dupilumab stimulated hair regrowth, with higher prediction in patients with elevated IgE [76]. On the other side, dupilumab was also described to induce AA in some case reports [23]. Additionally, numerous case reports suggest that ustekinumab, an antibody targeting IL-12/23, can also promote hair regrowth in AA [77,78]. However, these observations are rather limited to case reports and often involve patients with comorbidities such as psoriasis [79].

Hypothetically, as IL-1β remains a central cytokine generated during inflammasome activation, the potential use of IL-1 inhibitors such as anakinra or canakinumab should be evaluated in the future. For example, anakinra demonstrated a significant reduction in inflammatory lesions and pain scores in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, a condition whose pathogenesis is also partially driven by pyroptosis [79].

Currently, the evidence for biologics in AA is heterogeneous, ranging from controlled trials to case series. Biopsy studies suggest that targeting Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines could be useful, but clinical results are inconsistent, showing the need for larger trials to define their real role in the AA.

5.1.3. Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors (LoE-H2; Model-Trial-AA)

Apremilast and crisaborole belong to a group of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors. They modulate the innate immune system by increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, which in turn suppress NF-κB signaling [4,80]. NF-κB is involved in pyroptosis, so it suggests that PDE4 can limit inflammasome-driven inflammation in hair follicle cells (Figure 2) [80]. However, the clinical efficacy of PDE4 inhibitors in AA remains variable [81,82,83] and is limited to pilot clinical trials and case reports, with mixed outcomes.

5.1.4. Other AA-Linked Modulators (LoE-H2/H1)

Some therapeutic agents used in AA may influence pyroptosis indirectly by modulating upstream inflammatory pathways. For example, abatacept, which was evaluated in an open-label clinical study, blocks T-cell costimulation and reduces the release of IFN-γ and TNF-α [84]. That in the end, limits signals which drive inflammasome activation [84]. Further, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been assessed in a randomized controlled trial in patchy AA [85,86]. Anti-inflammatory effect of PRP was assigned to suppression of MCP-1 and induction of TGF-β, which are mechanisms that may reduce the inflammation promoting pyroptosis [85,86]. Statins, particularly simvastatin, have been investigated in small clinical series and appear to inhibit NF-κB and JAK/STAT signaling (Figure 2) [87,88,89]. Additionally, they reduce ROS generation. All of these are key triggers of NLRP3 activation [87,88,89]. Similarly, antihistamines such as fexofenadine and ebastine, supported mainly by retrospective clinical data, decrease Th2 cytokines, IFN-γ, and substance P, thereby lowering T-cell infiltration around hair follicles [90]. The above mechanisms suggest possible indirect effects, however direct evidence linking these agents to pyroptosis in AA remains limited.

Since 1979, dithranol (anthralin) has been used as a topical therapy for AA [91]. With the recent advances in understanding pyroptosis, its mechanism of action can now be viewed from a new perspective. Topical dithranol induces localized inflammation and disrupts the skin barrier, leading to epidermal hyperproliferation [92]. This irritation promotes the release of antimicrobial peptides (S100a8/a9) and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, both closely associated with pyroptosis pathways [92]. Understanding how dithranol modulates IL-1β secretion and inflammasome activity may open new perspectives for treatment strategies that specifically target pyroptosis in AA.

5.1.5. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy (LoE-X; Model-Skin-ExVivo/LoE-A2; Model-AA-C3H)

Human outer root sheath cells (hORSCs), which are integral to hair follicle structure and immune regulation, were shown to constantly express NLRP3 inflammasome components [93]. When stimulated with IFN-γ, hORSCs exhibited marked upregulation of NLRP3 and related inflammasome markers, showing a higher tendency for pyroptosis. Importantly, treatment with mesenchymal stem cell therapy (MSCT) effectively suppressed this response, reducing inflammasome activation and caspase-1–mediated pyroptotic signaling [93]. Notably, these effects were comparable to, or stronger than, those observed with ruxolitinib, highlighting the potential of hMSCs to limit follicular damage [94].

Although promising results have been observed in vitro, their effectiveness in vivo remains limited. Another study evaluated the efficacy of locally administered MSCT in an AA mouse model induced by IFN-γ [95]. Compared to controls, mice treated with MSC exhibited enhanced hair regrowth. MSCT significantly reduced local inflammatory cytokines, including JAK1, JAK2, STAT1, STAT3, IFN-γR, IL-1β, IL-16, IL-17α, and IL-18, while systemic cytokine levels remained unaffected (Figure 2) [95]. Additionally, MSC treatment normalized the expression of Wnt/β-catenin pathway genes and fibroblasts growth factors (FGF7, FGF2), which are essential for hair cycle regulation [95]. The available evidence on MSCT in AA is based on a combination of ex vivo human outer root sheath cell experiments and disease-relevant murine models (C3H/HeJ AA). Together, these levels of evidence suggest promising but still preliminary therapeutic potential, and further controlled human trials are needed to prove their efficacy.

5.1.6. Natural Compounds in AA (LoE-A2; Model-AA-C3H)

Currently, there are many different substances and compounds whose therapeutic effects are being studied in AA. In a mouse model (C3H/HeJ strain), researchers showed that pharmacological inhibition of the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway with MCC950 led to a marked improvement of disease manifestations (Figure 2) [96]. Oral administration of the MCC950 inhibitor not only suppressed inflammasome components (NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1 p10, GSDMD) and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18), but also resulted in visible healing of skin lesions and regrowth of hair [96]. The severity of follicular structural and functional disruption was significantly reduced, and histological analysis confirmed a lower infiltration of immune cells and a higher number of regenerated hair follicles in the group treated with MCC950 [96]. Further, a natural anti-inflammatory agent, called total glucosides of paeony (TGP), provided comparable results in a concentration-dependent manner, decreasing both caspase-1 activity and pyroptotic cell death in skin tissue in AA mice [13]. Subsequent compounds called water-soluble Ginkgo biloba leaf polysaccharides (WGBPs) were shown to reduce inflammation and pyroptosis in an AA mouse model [97]. The acidic fraction WGBP-A2 increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in skin, while the purified polysaccharide WGBP-A2b suppressed NF-κB–mediated inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α or IL-1β [97]. Additionally, Xuefu Zhuyu decoction (XZD) has been shown to induce hair regeneration in both AA patients and C3H/HeJ mice, accompanied by a marked reduction in proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α [98]. Since IL-1β and IL-18 are key mediators of inflammasome-driven pyroptosis, the suppression of upstream inflammatory signals by XZD suggests it may inhibit pyroptotic cell death in hair follicles [98]. To sum up, evidence in this category derives from AA-specific murine models, which are considered the gold standard for preclinical mechanistic and therapeutic studies in AA. Despite the fact that findings at this level provide strong experimental support, they remain preclinical, requiring validation in human studies.

5.2. Non-AA-Specific/General Hair-Growth Interventions (LoE-A1; Model-HG-C57/LoE-C; Model-ORS-polyIC)

SCD-153, a lipophilic prodrug of 4-methyl itaconate (4-MI), was designed to enter the skin and cells more easily, which can be used in alopecia areata therapy [99]. After topical application, SCD-153 is converted to 4-MI within the skin, minimizing systemic exposure [99]. In vitro studies on human keratinocytes stimulated with poly I:C or IFN-γ demonstrated that SCD-153 significantly reduced the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TLR3, and IFNβ. In C57BL/6 mice, topical SCD-153 promoted hair growth more effectively than 4-MI, dimethyl itaconate, vehicle, or even the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, showing promising indication in AA [99]. However, the evidence for this compound remains restricted to single in vitro and non-AA-specific murine studies, with no clinical trials conducted to date.

The overview of all therapies targeting pyroptosis in AA can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of therapies targeting inflammasomes and pyroptosis in AA.

6. Conclusions

Pyroptosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of AA, which provides new insights into the disease beyond classical T cell-driven models. Evidence suggests that outer root sheath cells act as active participants in inflammasome signaling and cytokine release, while mitochondrial dysfunction acts differently and can intensify pyroptosis. These discoveries not only deepen our understanding of AA’s pathophysiology but also open novel therapeutic strategies. Preclinical clinical data support the potential of inflammasome inhibitors, natural anti-inflammatory compounds, mesenchymal stem cell therapy, JAK inhibitors, biologics, and PDE4 modulators to reduce pyroptosis and restore immune tolerance within the hair follicle; however, most of these strategies remain experimental. Moreover, current data on the involvement of pyroptosis in AA remain hypothetical, being based mainly on preclinical studies, with no interventional clinical studies available. Eventually, targeting pyroptosis could be a new way to reduce disease relapse, protect hair follicles, and support lasting hair regrowth in AA patients in the future.

Author Contributions

M.Ł., J.P., B.J.-M., J.C.S. and P.K.K. methodology, M.Ł. and J.P.; software, M.Ł.; validation, M.Ł., J.P. and B.J.-M.; formal analysis, M.Ł. and J.P.; investigation, M.Ł. and J.P.; resources, B.J.-M.; data curation, M.Ł., J.P., B.J.-M., J.C.S. and P.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Ł., J.P., B.J.-M., J.C.S. and P.K.K.; writing—review and editing, B.J.-M., J.C.S. and P.K.K.; visualization, J.C.S. and P.K.K.; supervision, J.C.S. and P.K.K.; project administration, P.K.K.; funding acquisition, J.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Alopecia Areata |

| IL | Interleukin (np. IL-1β, IL-10, IL-12 itd.) |

| PCD | Programmed cell death |

| GSDMD | Gasdermin D |

| ASM | Acid sphingomyelinase |

| PRR | Pattern recognition receptor |

| PAMP | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| NLRP | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing protein |

| ASC | Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| AIM2 | Absent in melanoma 2 |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| TRIF | TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β |

| IRAK | Interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase |

| IFN | Interferon |

| NK | Natural Killer cell |

| GZMA/GZMB | Granzyme A/Granzyme B |

| HF | Hair follicle |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| α-MSH | Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| VIP | Vasoactive intestinal peptide |

| NKG2D | Natural Killer Group 2 Member D |

| Th | T helper (Th1, Th2, Th17) |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| CXCL | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11) |

| CXCR3 | C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| ORS | Outer root sheath |

| C3H/HeJ | C3H substrain of inbred mice carrying the Lps^d mutation (defective Toll-like receptor 4, TLR4) |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PDE4 | Phosphodiesterase 4 |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| hORSCs | Human outer root sheath cells |

| MSCT/MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell therapy/Mesenchymal stem cells |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor (FGF2, FGF7) |

| TGP | Total glucosides of paeony |

| WGBP | Water-soluble Ginkgo biloba leaf polysaccharides |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| XZD | Xuefu Zhuyu decoction |

| 4-MI | 4-methyl itaconate |

References

- Simakou, T.; Butcher, J.P.; Reid, S.; Henriquez, F.L. Alopecia areata: A multifactorial autoimmune condition. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 98, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, M.; Ito, T.; Ohyama, M. Alopecia areata: Current understanding of the pathophysiology and update on therapeutic approaches, featuring the Japanese Dermatological Association guidelines. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai, A.; Wang, E.H.C.; Lee, E.Y.; Aoki, V.; Christiano, A.M. Pathomechanisms of immune-mediated alopecia. Int. Immunol. 2019, 31, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Alopecia Areata: An Update on Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 61, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.; Harries, M.; Macbeth, A.E.; Chiu, W.S.; de Lusignan, S.; Messenger, A.G.; Tziotzios, C. Alopecia areata and risk of atopic and autoimmune conditions: Population-based cohort study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 48, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 2114–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajewski, P.K.; Jastrząb, B.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Jankowska-Konsur, A.; Saceda Corralo, D. Immune-Mediated Disorders in Patients with Alopecia Areata: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajac, I.; Tkalcic, M.; Dragojević, D.M.; Gruber, F. Roles of stress, stress perception and trait-anxiety in the onset and course of alopecia areata. J. Dermatol. 2003, 30, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowder, J.A.; Frieden, I.J.; Price, V.H. Alopecia areata in infants and newborns. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2002, 19, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minokawa, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Nakamura, M. Lifestyle Factors Involved in the Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudevan, S.O.; Behl, B.; Rathinam, V.A. Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 69, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, P.; Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Qiao, C.; Liu, W.; Deng, H.; Li, J.; Ning, P.; et al. Pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4310–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, K.; Du, X.; Yao, T.; Ye, J. Total glucosides of paeony inhibit NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated inflammation and pyroptosis in C3H/HeJ mice with alopecia areata. Biomol. Biomed. 2025, 25, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, D.; Monack, D.M.; Smith, M.R.; Ghori, N.; Falkow, S.; Zychlinsky, A. The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2396–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbi, H.; Chen, Y.; Thirumalai, K.; Zychlinsky, A. The interleukin 1beta-converting enzyme, caspase 1, is activated during Shigella flexneri-induced apoptosis in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 5165–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boise, L.H.; Collins, C.M. Salmonella-induced cell death: Apoptosis, necrosis or programmed cell death? Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, B.T.; Brennan, M.A. Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.L.; Cookson, B.T. Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 1812–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.L.; Cookson, B.T. Pyroptosis and host cell death responses during Salmonella infection. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 2562–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Cai, T.; Wang, F.; Shao, F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 2015, 526, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; She, Y.; Sun, Q.; Shi, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, D.C.; Shao, F. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 2016, 535, 111–116, Erratum in Nature 2016, 540, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aglietti, R.A.; Dueber, E.C. Recent Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Pyroptosis and Gasdermin Family Functions. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Wei, L.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, T.; Bai, J.; Dong, L.; Zhi, L. Dupilumab for alopecia areata treatment: A double-edged sword? J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5546–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Inflammasome activation and regulation: Toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavardhana, S.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Fernández, D.; Lamkanfi, M. Inflammatory caspases: Key regulators of inflammation and cell death. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Mayes, L.; Alnemri, D.; Cingolani, G.; Alnemri, E.S. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, J.; Gao, W.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Y.N.; Peng, X.; Xi, J.J.; Chen, S.; et al. Innate immune sensing of bacterial modifications of Rho GTPases by the Pyrin inflammasome. Nature 2014, 513, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, J.; Gong, Y.N.; Lu, Q.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Shao, F. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature 2011, 477, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, E.I.; Sutterwala, F.S. Initiation and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 265, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, E.A.; Leaf, I.A.; Treuting, P.M.; Mao, D.P.; Dors, M.; Sarkar, A.; Warren, S.E.; Wewers, M.D.; Aderem, A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Ismail, N. Non-Canonical Inflammasome Pathway: The Role of Cell Death and Inflammation in Ehrlichiosis. Cells 2023, 12, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayagaki, N.; Warming, S.; Lamkanfi, M.; Vande Walle, L.; Louie, S.; Dong, J.; Newton, K.; Qu, Y.; Liu, J.; Heldens, S.; et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 2011, 479, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.M.; Kanneganti, T.D. Regulation of inflammasome activation. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 265, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayagaki, N.; Stowe, I.B.; Lee, B.L.; O’Rourke, K.; Anderson, K.; Warming, S.; Cuellar, T.; Haley, B.; Roose-Girma, M.; Phung, Q.T.; et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 2015, 526, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W.; Ding, J.; Li, P.; Hu, L.; Shao, F. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 2014, 514, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühl, S.; Broz, P. Caspase-11 activates a canonical NLRP3 inflammasome by promoting K(+) efflux. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015, 45, 2927–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, J.; Liu, B.C.; Muendlein, H.I.; Li, P.; Nilson, R.; Tang, A.Y.; Rongvaux, A.; Bunnell, S.C.; Shao, F.; Green, D.R.; et al. Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10888–E10897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orning, P.; Weng, D.; Starheim, K.; Ratner, D.; Best, Z.; Lee, B.; Brooks, A.; Xia, S.; Wu, H.; Kelliher, M.A.; et al. Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science 2018, 362, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhao, R.; Xia, W.; Chang, C.W.; You, Y.; Hsu, J.M.; Nie, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Liu, C.; et al. PD-L1-mediated gasdermin C expression switches apoptosis to pyroptosis in cancer cells and facilitates tumour necrosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 1264–1275, Erratum in Nat Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, K.L.; Kulakova, L.; Herzberg, O. Gene polymorphism linked to increased asthma and IBD risk alters gasdermin-B structure, a sulfatide and phosphoinositide binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E1128–E1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; He, H.; Wang, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Granzyme A from cytotoxic lymphocytes cleaves GSDMB to trigger pyroptosis in target cells. Science 2020, 368, eaaz7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Daalen, K.R.; Reijneveld, J.F.; Bovenschen, N. Modulation of Inflammation by Extracellular Granzyme A. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, S.; Kong, Q.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Junqueira, C.; Meza-Sosa, K.F.; Mok, T.M.Y.; Ansara, J.; et al. Gasdermin E suppresses tumour growth by activating anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2020, 579, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, F.; Drake, L.A.; Senna, M.M.; Rezaei, N. Alopecia areata: A review of disease pathogenesis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetter, T.; de Graaf, D.M.; Claus, I.; Wenzel, J. Aberrant inflammasome activation as a driving force of human autoimmune skin disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1190388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśkiel-Burnat, A.; Osińska, M.; Salińska, A.; Blicharz, L.; Goldust, M.; Olszewska, M.; Rudnicka, L. The Role of Serum Th1, Th2, and Th17 Cytokines in Patients with Alopecia Areata: Clinical Implications. Cells 2021, 10, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divito, S.J.; Kupper, T.S. Inhibiting Janus kinases to treat alopecia areata. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 989–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzulla, L.C.; Wang, E.H.C.; Avila, L.; Lo Sicco, K.; Brinster, N.; Christiano, A.M.; Shapiro, J. Alopecia areata: Disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.; Cho, S.D.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, S.H.; Jeong, S.; Jeon, M.; Lee, H.; et al. A virtual memory CD8(+) T cell-originated subset causes alopecia areata through innate-like cytotoxicity. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Aziz Ragab, M.A.; Hassan, E.M.; El Niely, D.; Mohamed, M.M. Serum level of interleukin-15 in active alopecia areata patients and its relation to age, sex, and disease severity. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2020, 37, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Chéret, J.; Scala, F.D.; Rajabi-Estarabadi, A.; Akhundlu, A.; Demetrius, D.L.; Gherardini, J.; Keren, A.; Harries, M.; Rodriguez-Feliz, J.; et al. Interleukin-15 is a hair follicle immune privilege guardian. J. Autoimmun. 2024, 145, 103217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K.A.; McDonald, E.; Moffat, F.; Tutino, M.; Castelino, M.; Barton, A.; Cavanagh, J.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Siebert, S.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Alopecia areata is characterized by dysregulation in systemic type 17 and type 2 cytokines, which may contribute to disease-associated psychological morbidity. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, K.; Kozłowska, M.; Kaszuba, A.; Lesiak, A.; Narbutt, J.; Zalewska-Janowska, A. Increased Serum Levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β, and IL-6 in Patients with Alopecia Areata and Nonsegmental Vitiligo. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5693572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.M.; Choi, D.K.; Sohn, K.C.; Kim, S.Y.; Min Ha, J.; Ho Lee, Y.; Im, M.; Seo, Y.J.; Deok Kim, C.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Double-stranded RNA induces inflammation via the NF-κB pathway and inflammasome activation in the outer root sheath cells of hair follicles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.M.; Choi, D.K.; Sohn, K.C.; Koh, J.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Seo, Y.J.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, Y. Induction of alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice using polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly[I:C]) and interferon-gamma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.M.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, M.S.; Park, S.; Hong, D.; Jung, K.E.; Seo, Y.J.; Kim, C.D.; Yang, H.; Lee, Y. The crosstalk between PTEN-induced kinase 1-mediated mitophagy and the inflammasome in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e14844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Guo, Z.; Pan, W.; Wang, X.; Tong, Q. Advances in the mechanism and new therapies of alopecia areata. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 26, 1893–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, M.D.; Kuo, F.I.; Smith, P.A. Targeting the Janus Kinase Family in Autoimmune Skin Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.M.; Bonelli, M.; Gadina, M.; O’Shea, J.J. Type I/II cytokines, JAKs, and new strategies for treating autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, R.C.; Petukhova, L.; Ripke, S.; Huang, H.; Menelaou, A.; Redler, S.; Becker, T.; Heilmann, S.; Yamany, T.; Duvic, M.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis in alopecia areata resolves HLA associations and reveals two new susceptibility loci. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhar, A.; Schrum, A.G.; Etzioni, A.; Waldmann, H.; Paus, R. Alopecia areata: Animal models illuminate autoimmune pathogenesis and novel immunotherapeutic strategies. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Dai, Z.; Jabbari, A.; Cerise, J.E.; Higgins, C.A.; Gong, W.; de Jong, A.; Harel, S.; DeStefano, G.M.; Rothman, L.; et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, H.R.; Lee, D.G.; Jeong, K.H.; Kang, H. The Effect of JAK Inhibitor on the Survival, Anagen Re-Entry, and Hair Follicle Immune Privilege Restoration in Human Dermal Papilla Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.F.; Sinclair, R. JAK inhibition in the treatment of alopecia areata—A promising new dawn? Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, K.; Sebaratnam, D.F. JAK inhibitors for alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solimani, F.; Meier, K.; Ghoreschi, K. Emerging Topical and Systemic JAK Inhibitors in Dermatology. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSweeney, S.M.; Rayinda, T.; McGrath, J.A.; Tziotzios, C. Two phase III trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata: A critically appraised research paper. Br. J. Dermatol. 2023, 188, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senna, M.; Mostaghimi, A.; Ohyama, M.; Sinclair, R.; Dutronc, Y.; Wu, W.S.; Yu, G.; Chiasserini, C.; Somani, N.; Holzwarth, K.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of baricitinib in patients with severe alopecia areata: 104-week results from BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Senna, M.M.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Lynde, C.; Zirwas, M.; Maari, C.; Prajapati, V.H.; Sapra, S.; Brzewski, P.; Osman, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of deuruxolitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase inhibitor, in adults with alopecia areata: Results from the Phase 3 randomized, controlled trial (THRIVE-AA1). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziotzios, C.; Sinclair, R.; Lesiak, A.; Mehlis, S.; Kinoshita-Ise, M.; Tsianakas, A.; Luo, X.; Law, E.H.; Ishowo-Adejumo, R.; Wolk, R.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata and at least 25% scalp hair loss: Results from the ALLEGRO-LT phase 3, open-label study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 1152–1162, Erratum in J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 1687–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnette, R.; Banerjee, A.; Sikirica, V.; Peeva, E.; Wyrwich, K. Characterizing the relationships between patient-reported outcomes and clinician assessments of alopecia areata in a phase 2a randomized trial of ritlecitinib and brepocitinib. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Nia, J.K.; Hashim, P.W.; Mansouri, Y.; Alia, E.; Taliercio, M.; Desai, P.N.; Lebwohl, M.G. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab treatment in adults with extensive alopecia areata. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2018, 310, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Ungar, B.; Noda, S.; Shroff, A.; Mansouri, Y.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Czernik, A.; Zheng, X.; Estrada, Y.D.; Xu, H.; et al. Alopecia areata profiling shows TH1, TH2, and IL-23 cytokine activation without parallel TH17/TH22 skewing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Bares, J.; Chima, M.; Hawkes, J.E.; Gilleaudeau, P.; Sullivan-Whalen, M.; Singer, G.K.; Garcet, S.; Pavel, A.B.; et al. Phase 2a randomized clinical trial of dupilumab (anti-IL-4Rα) for alopecia areata patients. Allergy 2022, 77, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleisa, A.; Lim, Y.; Gordon, S.; Her, M.J.; Zancanaro, P.; Abudu, M.; Deverapalli, S.C.; Madani, A.; Rosmarin, D. Response to ustekinumab in three pediatric patients with alopecia areata. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, e44–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Ungar, B.; Noda, S.; Suprun, M.; Shroff, A.; Dutt, R.; Khattri, S.; Min, M.; Mansouri, Y.; Zheng, X.; et al. Extensive alopecia areata is reversed by IL-12/IL-23p40 cytokine antagonism. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnanelli, G.; Cavani, A.; Canzona, F.; Mazzanti, C. Mild therapeutic response of alopecia areata during treatment of psoriasis with secukinumab. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2020, 30, 602–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, N.; Gupta, S. Apremilast is efficacious in refractory alopecia areata. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Nijhawan, M.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, A. Comparing the efficacy of oral apremilast, intralesional corticosteroids, and their combination in patients with patchy alopecia areata: A randomized clinical controlled trial. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 317, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, D.; Pavel, A.; Yao, C.; Kimmel, G.; Nia, J.; Hashim, P.; Vekaria, A.S.; Taliercio, M.; Singer, G.; Karalekas, R.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled single-center pilot study of the safety and efficacy of apremilast in subjects with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, M.; Shimoyama, H.; Nomura, M.; Nakashima, C.; Hirabayashi, M.; Sei, Y.; Kuwano, Y. Efficacy of the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, apremilast, in a patient with severe alopecia areata. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2019, 29, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay-Wiggan, J.; Sallee, B.N.; Wang, E.H.C.; Sansaricq, F.; Nguyen, N.; Kim, C.; Chen, J.C.; Christiano, A.M.; Clynes, R. An open-label study evaluating the efficacy of abatacept in alopecia areata. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohanna, H.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Griggs, J.W.; Tosti, A. Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Alopecia Areata: A Review. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2020, 20, S45–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trink, A.; Sorbellini, E.; Bezzola, P.; Rodella, L.; Rezzani, R.; Ramot, Y.; Rinaldi, F. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, half-head study to evaluate the effects of platelet-rich plasma on alopecia areata. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Suh, D.W.; Lew, B.L.; Sim, W.Y. Simvastatin/Ezetimibe Therapy for Recalcitrant Alopecia Areata: An Open Prospective Study of 14 Patients. Ann. Dermatol. 2017, 29, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattouf, C.; Jimenez, J.J.; Tosti, A.; Miteva, M.; Wikramanayake, T.C.; Kittles, C.; Herskovitz, I.; Handler, M.Z.; Fabbrocini, G.; Schachner, L.A. Treatment of alopecia areata with simvastatin/ezetimibe. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.M.; Jung, K.E.; Yim, S.H.; Rao, B.; Hong, D.; Seo, Y.J.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, Y. Putative therapeutic mechanisms of simvastatin in the treatment of alopecia areata. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, S.; Nakajima, T.; Toda, N.; Itami, S. Fexofenadine hydrochloride enhances the efficacy of contact immunotherapy for extensive alopecia areata: Retrospective analysis of 121 cases. J. Dermatol. 2009, 36, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benezeder, T.; Gehad, A.; Patra, V.; Clark, R.; Wolf, P. Induction of IL-1β and antimicrobial peptides as a potential mechanism for topical dithranol. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoeckel, C.; Weissmann, I.; Plewig, G.; Braun-Falco, O. Treatment of alopecia areata by anthralin-induced dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. 1979, 115, 1254–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Park, S.H.; Park, H.R.; Lee, Y.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.E. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Antagonize IFN-Induced Proinflammatory Changes and Growth Inhibition Effects via Wnt/β-Catenin and JAK/STAT Pathway in Human Outer Root Sheath Cells and Hair Follicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, K.J.; Park, S.H.; Kang, H. Ex Vivo Treatment with Allogenic Mesenchymal Stem Cells of a Healthy Donor on Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Patients with Severe Alopecia Areata: Targeting Dysregulated T Cells and the Acquisition of Immunotolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Song, S.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.E. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Alopecia Areata: Visual and Molecular Evidence from a Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; Yamada, Y.; Sekiguchi, K.; Mori, S.; Matsumoto, T. NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to development of alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, G.; Yu, W.; Cui, Q.; Lu, X.; Du, P.; An, L. Hair-growth promoting effect and anti-inflammatory mechanism of Ginkgo biloba polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, 118811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Duan, X.; Liu, J.; Sha, X.; Gong, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z. The antiinflammatory effects of Xuefu Zhuyu decoction on C3H/HeJ mice with alopecia areata. Phytomedicine 2021, 81, 153423, Erratum in Phytomedicine 2021, 83, 153510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Gori, S.; Alt, J.; Tiwari, S.; Iyer, J.; Talwar, R.; Hinsu, D.; Ahirwar, K.; Mohanty, S.; Khunt, C.; et al. Topical SCD-153, a 4-methyl itaconate prodrug, for the treatment of alopecia areata. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgac297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).