Abstract

A novel chemosensor has been developed for the accurate and sensitive detection of Hg2+ ions in industrial wastewater. This sensor uses a stick-like nanocellulose architecture synthesized via a green method. The unique morphology and surface area of nanocellulose make it an ideal mesoporous substrate for immobilizing the chromophore 1-(benzothiophenyl)-3-(benzooxazolyl)-2-((4-bromophenyl)diazenyl)propane-1,3-dione (azo-dione ligand, ADOL). Comprehensive characterization of the fabricated chemosensor and its nanocellulose base was carried out using FTIR, SEM, TEM, BET surface area, and XRD to evaluate their structural and morphological properties. Spectrophotometric parameters, including pH, response time, selectivity, and sensitivity, were extensively optimized to ensure optimal sensing performance, enabling detection of Hg2+ at very low concentrations. Method validation was performed in accordance with ICH (International Council for Harmonisation) guidelines, confirming the reliability of the sensor in terms of limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), linearity, and precision. The spectrophotometric method achieved a highly sensitive LOD of 9.07 µg L−1. Moreover, the ADOL chemosensor demonstrated excellent reusability, maintaining performance over five cycles following regeneration with 0.1 M thiourea, underscoring its sustainability. Finally, the sensor exhibited outstanding performance in detecting Hg2+ across various industrial wastewater samples, highlighting its practical applicability, exceptional selectivity, and high sensitivity for real-world environmental monitoring.

1. Introduction

The increasing industrialization and urbanization of society have led to a significant rise in environmental pollution, particularly in the form of heavy metals as mercury in wastewater [1]. Heavy metals such as mercury (Hg) are not only toxic but also persistent in the environment, posing serious health risks to both humans and wildlife [2]. Mercury can accumulate in the food chain, leading to bioaccumulation and biomagnification, which can result in severe ecological and health consequences [3]. Consequently, the detection and removal of mercury from industrial effluents have become pressing concerns for environmental scientists and engineers alike [4].

Traditional methods for mercury detection, including atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), while highly accurate, often require expensive equipment, skilled personnel, and extensive sample preparation, making them less suitable for on-site monitoring [5]. In response to these challenges, there has been growing interest in developing novel sensing technologies that are not only efficient and cost-effective but also environmentally friendly. Among these technologies, optical nanosensors have emerged as a promising solution due to their high sensitivity, rapid response time, and potential for miniaturization [6,7]. Optical nanosensors use light-based detection to identify and quantify analytes, including heavy metals [8]. These sensors incorporate nanomaterials with unique optical properties, such as absorbance, fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance, or colorimetric changes, in response to target analytes. The integration of nanomaterials enhances detection sensitivity and selectivity, making them suitable for real-time monitoring applications [9].

Nanocellulose is a biopolymer that has gained attention in various fields, including biomedical applications, packaging, and environmental remediation. Its properties of high surface area, biocompatibility, and mechanical strength make it ideal for developing optical nanosensors [10,11]. The preparation of nanocellulose from purified cellulose sources, such as commercial cellulose powder, ensures reproducibility, purity, and control over structural properties, which is essential for advanced applications in sensing and nanotechnology [12]. Cellulose powder provides a consistent, contamination-free source for nanocellulose production compared to heterogeneous biomass [13]. This controlled material enables precise tailoring of nanocellulose characteristics, such as crystallinity, particle size, and surface functionality, which enhance sensor performance. Various methods, including mechanical disintegration, enzymatic hydrolysis, and chemical treatments, can be used to obtain nanocellulose with properties suitable for sensor fabrication [14]. The development of an optical nanosensor using eco-friendly nanocellulose particles with organic ligands offers an approach to detect heavy metals in wastewater. This innovative design leverages nanocellulose properties while emphasizing sustainability in sensor technology. Additionally, the immobilization of organic ligands onto nanocellulose particles is critical for enhancing the selectivity of optical nanosensors [15]. Organic ligands selectively bind to heavy metal ions, enabling recognition of target analytes [16]. The choice of ligand determines sensor efficiency and specificity. Various ligands, including thiols, amines, and chelating agents, form stable complexes with heavy metals. Successful ligand immobilization onto nanocellulose surfaces improves sensor performance, enabling detection of trace heavy metals in complex matrices like industrial wastewater [17].

Several analytical methods have been developed for sensitive and selective detection of Hg2+. Colorimetric sensors based on functionalized nanoparticles, such as silver nanoparticles with graphene oxide or metal-oxo clusters, allow rapid visual or spectrophotometric detection. Fluorescent probes, including carbon- and silicon-based quantum dots or doped nanodots, enable low-level detection in water, food, soil, and cellular samples. Natural polymer-stabilized nanoparticles, such as carboxymethyl cellulose-supported silver nanoparticles, further provide biocompatible platforms for Hg2+ sensing. These approaches combine sensitivity, selectivity, and versatility, forming the basis for novel optical sensors [15]. In addition to detection, various methods have been developed for the removal of heavy metals from water, including functionalized solid materials, biochar, and polymer-supported nanoparticles, demonstrating high efficiency for mercury and other toxic metals. These strategies highlight the importance of combining sensitive detection with effective remediation [15].

In this study, we aim to explore the preparation of optical nanosensors utilizing nanocellulose derived from cellulose powder, focusing on the immobilization of organic ligands for the detection of mercury in industrial wastewater. We will investigate the optimal conditions for nanocellulose extraction, ligand immobilization techniques, and the optical characterization of the resulting nanosensors. Furthermore, the sensor’s performance will be evaluated in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, and response time when exposed to various heavy metals commonly present in industrial effluents. The significance of this research lies not only in the development of a novel sensing platform but also in its contribution to the broader field of environmental monitoring and remediation. By providing an effective and sustainable approach for mercury detection, this work supports improved wastewater management practices and the protection of public health. The outcomes of this study could pave the way for practical, cost-effective, and reliable solutions for heavy metal detection and management.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ligand Synthesis Protocol

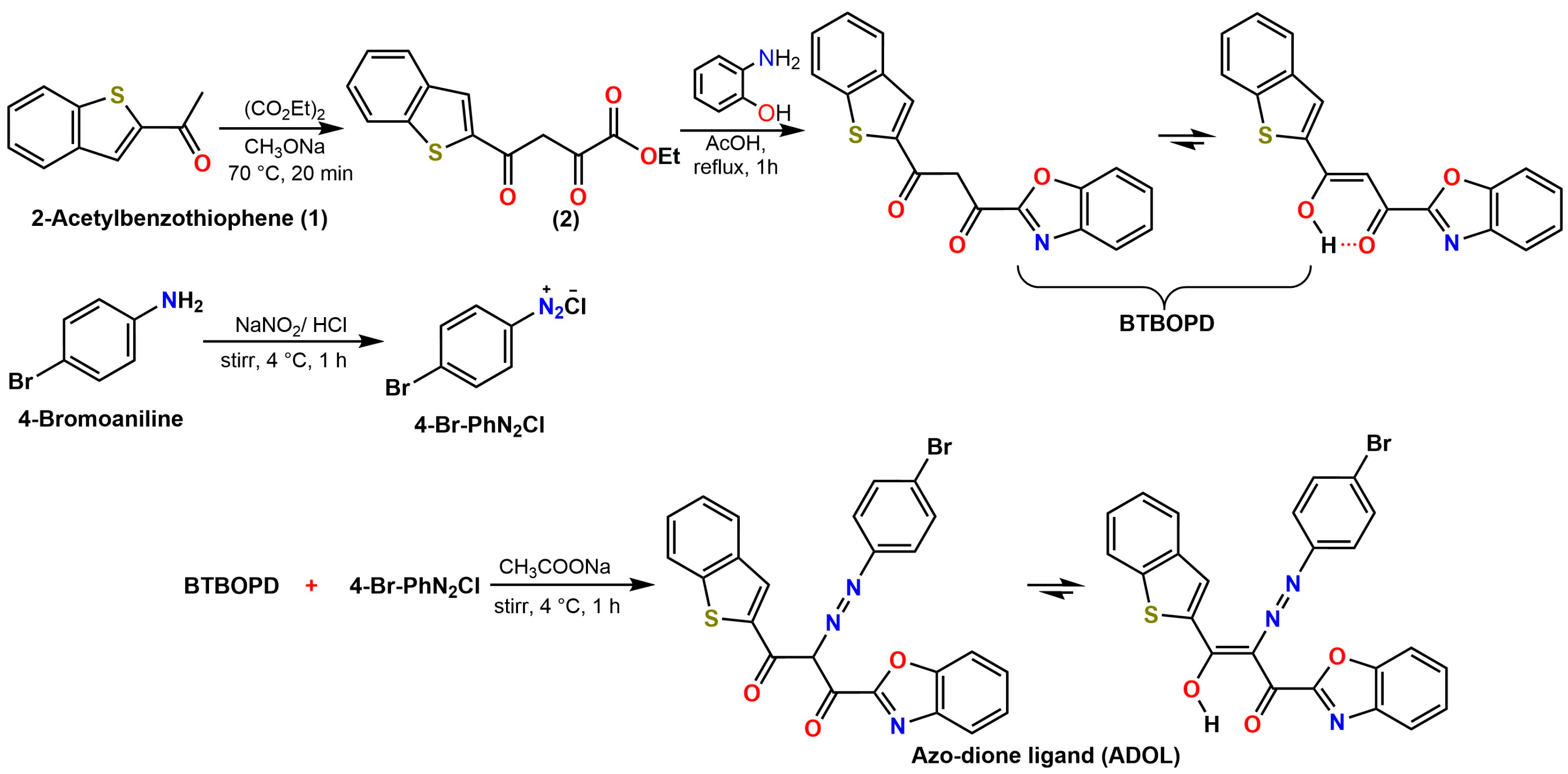

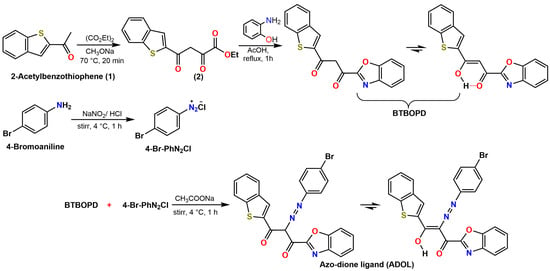

The azo-functionalized diketone ligand ADOL has been synthesized through a concise synthetic route (Scheme 1) involving the integration of a benzothiophene core with a benzo[d]oxazole moiety. The reaction sequence is initiated with the synthesis of Ethyl-4-(benzo[b]thiophene-2-carbonyl)-pyruvate (compound 2) via a Claisen condensation between 2-acetylbenzothiophene and diethyl oxalate, wherein sodium methoxide catalyzes the reaction at a temperature of 70 °C. The subsequent reaction of compound 2 with 2-aminophenol in acetic acid yields 1-(benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl)-3-(benzo[d]oxazol-2-yl) propane-1,3-dione (BTBOPD), a β-diketone displaying intramolecular hydrogen bonding. This equilibrium is in fact quite characteristic of 1,3-diketones in general. Simultaneously, 4-bromoaniline is diazotized with NaNO2/HCl at a chilly 4 °C, producing the diazonium salt (4-Br-PhN2+Cl−). This reactive intermediate is then coupled with BTBOPD under mildly alkaline conditions, achieved by adding CH3COONa at 4 °C, to yield the desired azo-dione ligand (ADOL). This coupling reaction selectively targets the active methylene site in BTBOPD, forging a robust azo N=N bond with the aromatic diazonium partner. The end product (ADOL) boasts a diverse range of donating sites, including azo, carbonyl, and heteroaromatic units, rendering it an appealing ligand scaffold, particularly for coordination chemistry and materials applications. This synthesis features an efficient and modular design that operates under mild conditions, fundamental characteristics of a more sustainable approach.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Ethyl 4-(benzo[b]thiophene-2-carbonyl)-pyruvate (2), BTBOPD, and azo-dione ligand (ADOL).

2.2. Structural Characterization of New Ligand

2.2.1. Microanalytical Analysis and Mass Spectrometry

The newly synthesized compounds were obtained in satisfactory yields. The elemental analyses of these compounds, as detailed in the Experimental section, confirmed their purity and corroborated the proposed molecular formulas.

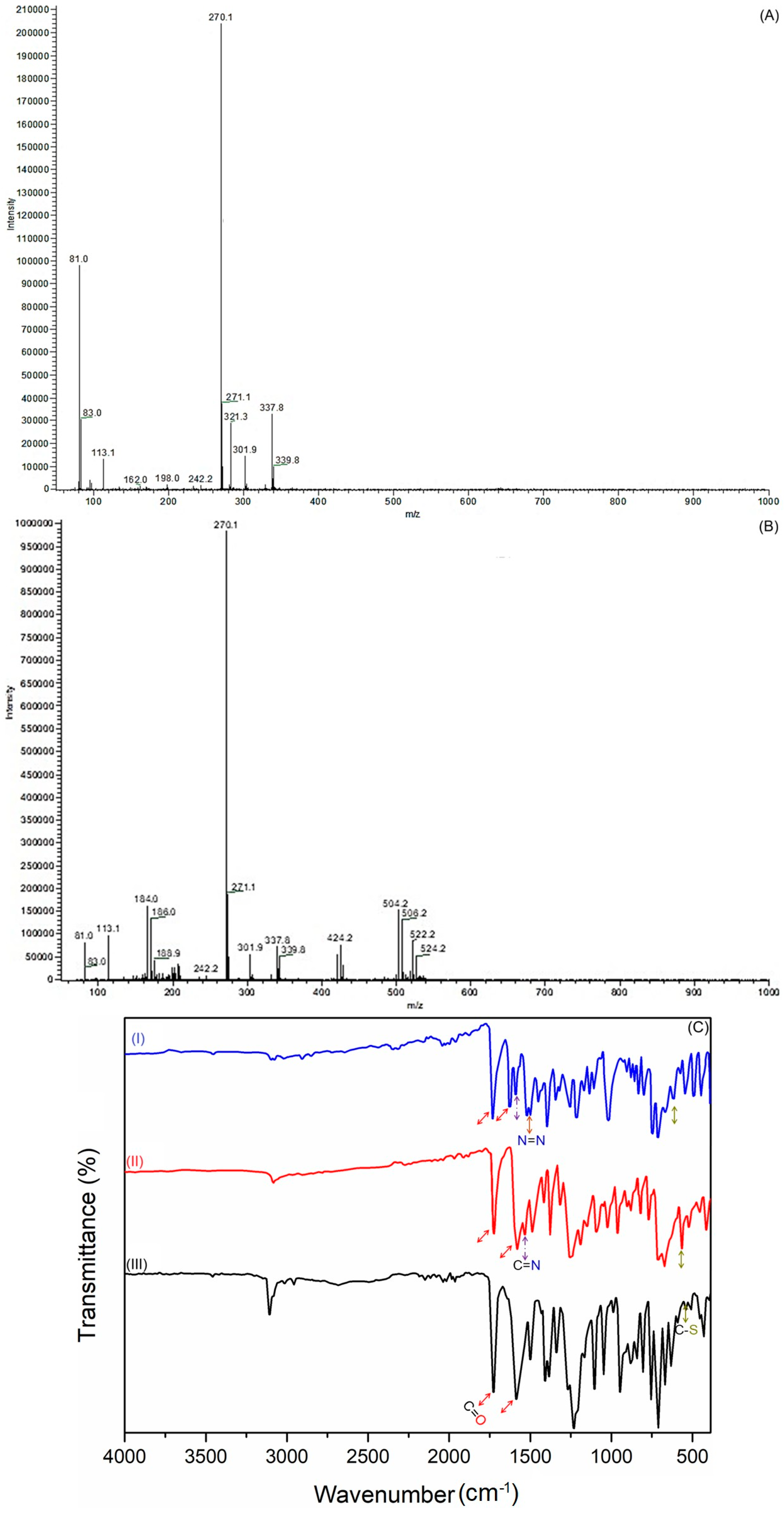

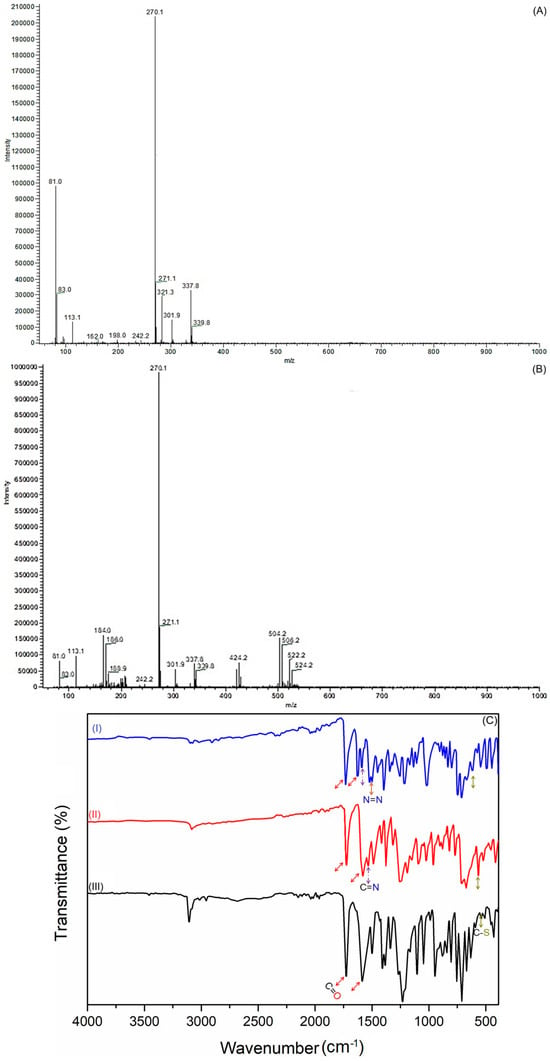

To further verify the structures of the intermediate ligand BTBOPD and the final azo-dione ligand ADOL, chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CI-MS) was employed with ammonia as the ionizing reagent. The resulting spectra (Figure 1) provided additional evidence that helped confirm their molecular structures. The CI-MS spectrum for BTBOPD (Figure 1A) shows a molecular ion peak at m/z 339.8, corresponding to the [M + NH4]+ adduct, while a prominent quasimolecular ion peak [M + H]+ emerges at m/z 321.3, confirming the molecular weight of the neutral compound. Interestingly, a distinctive fragment ion emerges at m/z 271.1, resulting from the loss of a C4H3 moiety for the benzothiophene (or benzoxazole) skeleton. On the other hand, the CI-MS spectrum of the azo-functionalized derivative (ADOL) (Figure 1B) shows molecular ion peaks at m/z 522.2 and 524.2, corresponding to the ammonium adducts [M (79Br) + NH4]+ and [M (81Br) + NH4]+, a clear indication that the species contains bromine, as evidenced by the characteristic isotopic pattern of this element. Meanwhile, the protonated molecular ions [M + H]+ are detected at m/z 504.2 and 506.2, which mirrors the natural isotopic distribution of bromine. This isotopic pattern confirms the presence of a bromine-containing species. Moreover, a prominent fragment appears at m/z 424.2 due to the loss of a bromine atom, further supporting the proposed molecular structure for ADOL. These MS data provide a robust analytical foundation, confirming that both ligands were successfully synthesized.

Figure 1.

(A,B) Chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CI-MS) (NH3) of (A) BTBOPD and (B) ADOL. (C) FTIR spectra of (I) Ethyl 4-(benzo[b]thiophene-2-carbonyl)-pyruvate (2); (II) BTBOPD; and (III) ADOL.

2.2.2. Infrared Spectroscopy

The sequential conversion of Ethyl 4-(benzo[b]thiophene-2-carbonyl)-pyruvate (2) to BTBOPD and ultimately to the azo-dione ligand ADOL can be traced using FTIR spectroscopy (Figure 1C). The data reveal distinct changes consistent with the proposed transformations, as indicated by the notable shifts in the vibrations of functional groups alongside their intensities. The FTIR spectrum of compound 2 revealed a pronounced ester stretching band ν(C=O) at 1734 cm−1, accompanied by a ketone band ν(C=O) at 1719 cm−1, confirming the presence of ester and β-keto functionalities. Moreover, the characteristic out-of-plane C-H bending vibrations of substituted aromatic rings were observed in the 1600–1450 cm−1 range. Heterocyclic skeletal vibrations stemming from the benzothiophene core were also evident between 800 and 700 cm−1 [18,19].

Upon cyclocondensation with 2-aminophenol to form BTBOPD, the ester ν(C=O) band at 1734 cm−1 vanishes, and a new ν(C=N) band emerges at 1605 cm−1, providing strong evidence for benzo[d]oxazole formation. Meanwhile, the benzothiophene ring’s C–S stretching vibration stays put at 717 cm−1, signifying that the thiophene core is preserved; this implies the reaction is remarkably selective. Furthermore, the distinct ν(C=O) absorption, a high-intensity band at 1723 cm−1, verifies the presence of the β-diketone moiety. Moreover, the oxazole’s C–O–C stretching vibration is distinctly visible at 1120 cm−1 and the benzothiophene ring’s C–S stretching vibration persists at 747 cm−1, suggesting that the thiophene core remains unaltered throughout the process [20,21].

Upon azo coupling to yield ADOL, notable spectral changes included the appearance of a medium-intensity ν(O–H) band at 3462 cm−1 (enolic hydroxyl), a shift in the ν(C=O) band to 1738 cm−1, and the emergence of a distinct ν(N=N) azo stretch at 1460 cm−1, confirming azo group formation [22]. The retention of oxazole (1121 cm−1, 867 cm−1) and thiophene (715 cm−1) signatures across the spectra indicated preservation of the heteroaromatic cores during both reaction steps. Collectively, these spectral evolutions validated the successful synthesis and structural integrity of BTBOPD and ADOL, in agreement with the proposed reaction mechanism.

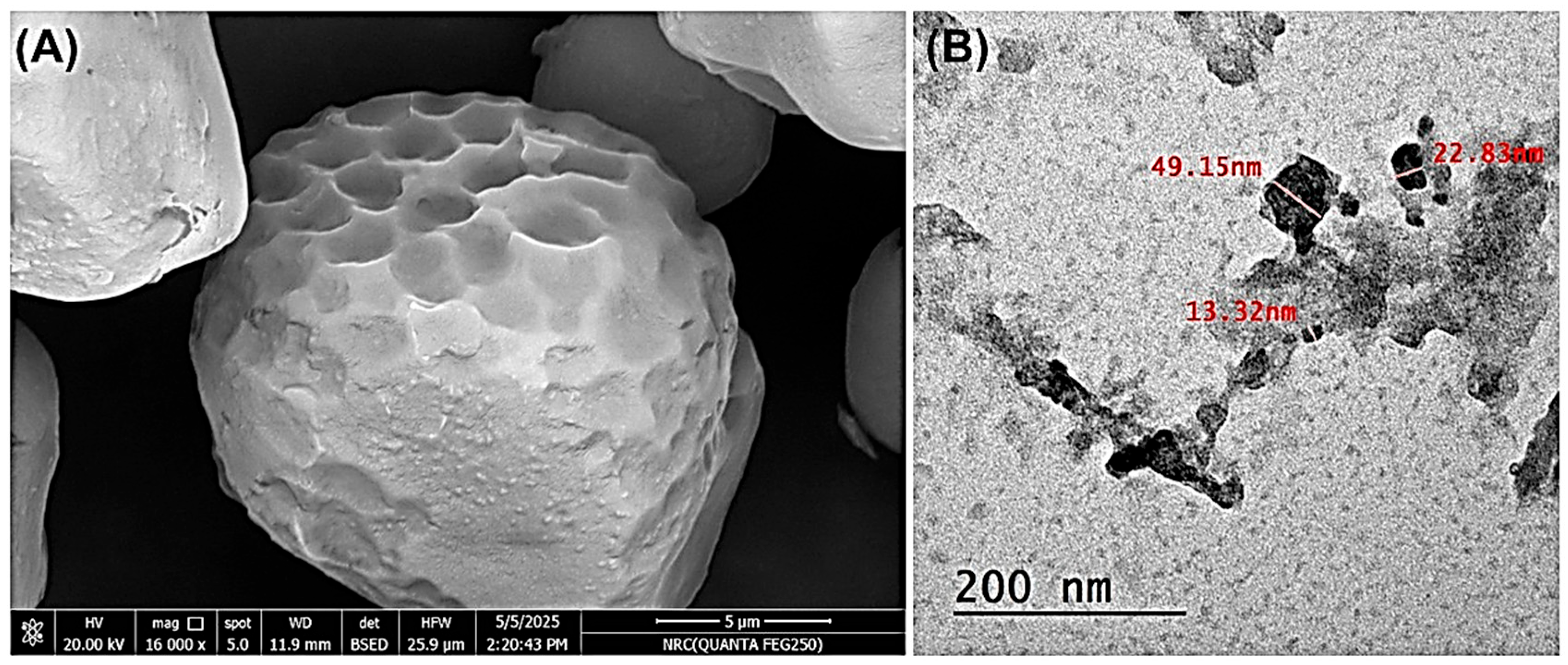

2.2.3. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

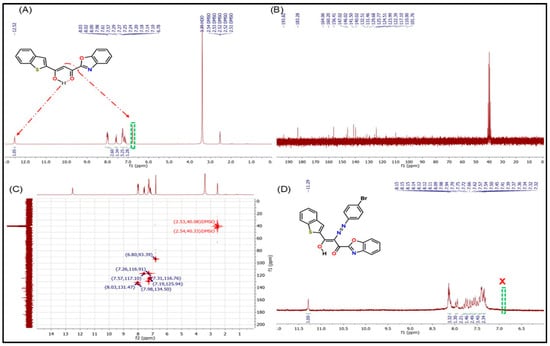

Through a thorough analysis of the 1H NMR (Figure 2A) and 13C NMR (Figure 2B) spectra, the structural configuration of BTBOPD in deuterated solution has been elucidated, confirming the predominance of enol tautomerism. The 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 2A) features a strongly deshielded singlet at δ 12.52 mg L−1, a clear indicator of the enol form which corresponds to the intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded enolic –OH proton. This is reinforced by a singlet at δ 6.78 mg L−1, attributed to the olefinic proton of the C=C–OH unit, providing further corroboration of the enolic structure. The aromatic protons of the benzothiophene and benzo[d]oxazole rings resonate between δ 8.01 and 7.05 mg L−1, exhibiting splitting patterns that are consistent with the condensed heteroaromatic framework, effectively validating the molecule’s overall architecture.

Figure 2.

(A) 1H NMR, (B) 13C NMR, and (C) 1H–13C COSY NMR spectra of BTBOPD. (D) 1H NMR spectrum of ADOL.

The 13C NMR spectrum (Figure 2B) lends further credence to these findings, revealing two distinct low-field resonances at δ 193.82 and δ 101.76 mg L−1, which are assigned to the enol carbon and its β-carbon (i.e., C=C–OH), respectively. The remaining resonances, spanning δ 164.06–110.00 mg L−1, stem from the aromatic carbons of the two heteroaromatic moieties; their chemical shifts align with the electron delocalization arising from intramolecular hydrogen bonding in the enolic tautomer. The presence of only one additional carbonyl resonance at δ 183.28 mg L−1, corresponding to the keto carbonyl, indicates that the second carbonyl exists predominantly in the enolized form rather than as a free C=O. Collectively, the strongly deshielded enolic proton, the characteristic olefinic signal, and the 13C chemical shift pattern provide unambiguous evidence that BTBOPD exists predominantly in its enol form in DMSO-d6, stabilized by conjugation between the β-diketone unit and the heteroaromatic rings, as well as by intramolecular O–H···O hydrogen bonding.

The 1H–13C COSY NMR spectrum (Figure 2C) of BTBOPD provides definitive two-dimensional correlation evidence for the predominance of the enol tautomer in solution. A strong cross-peak between the highly deshielded singlet proton at δ 12.52 mg L−1 and the carbon resonance at δ 193.82 mg L−1 confirms direct coupling of the enolic –OH proton to the enolized carbon (C=C–OH). Additionally, the olefinic proton at δ 6.78 mg L−1 shows a distinct correlation with the β-carbon of the enolized system at δ 101.76 mg L−1, consistent with a C=C–OH fragment stabilized by conjugation and intramolecular hydrogen bonding. The carbonyl resonance at δ 183.28 mg L−1 exhibits no direct proton correlation in the COSY map, as expected for the non-enolized keto carbonyl, supporting a mono-enol configuration. The remaining aromatic protons (δ 8.01–7.05 p mg L−1) display correlations with carbons in the δ 164.06–110.00 mg L−1 range, confirming the integrity of the fused benzothiophene and benzo[d]oxazole systems. The absence of a second distinct keto C=O resonance with associated α-proton correlations, along with the prominent enolic –OH/olefinic C correlations, indicates that the β-diketone moiety exists predominantly in the enolized form rather than the diketo tautomer. Overall, these COSY NMR findings confirm that BTBOPD adopts an intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded enol structure in DMSO-d6, stabilized by extended conjugation across the heteroaromatic framework.

Upon conversion of BTBOPD to ADOL via diazonium coupling, the enolic –OH signal is retained but shifted up-field to δ 11.29 mg L−1, reflecting altered hydrogen bonding and electronic environments induced by the azo linkage and the electron-withdrawing 4-bromophenyl substituent. Notably, the olefinic proton resonance observed in BTBOPD disappears in ADOL, consistent with substitution at the active methylene position during azo coupling. The aromatic region of ADOL (δ 8.16–7.31 mg L−1) displays increased signal complexity compared to BTBOPD, arising from the additional protons of the 4-bromophenyl-azo fragment. The persistence of a single highly deshielded proton signal in the δ 11–12 mg L−1 range, in the absence of resonances attributable to a fully diketo form, supports the conclusion that ADOL, like its precursor, predominantly exists in the intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded enol tautomer in DMSO-d6. This tautomeric preference is likely stabilized by extended π-conjugation involving the azo group, β-diketone moiety, and heteroaromatic rings.

2.3. Characterization of Cellulose Nanoparticles

2.3.1. Morphological Characterization

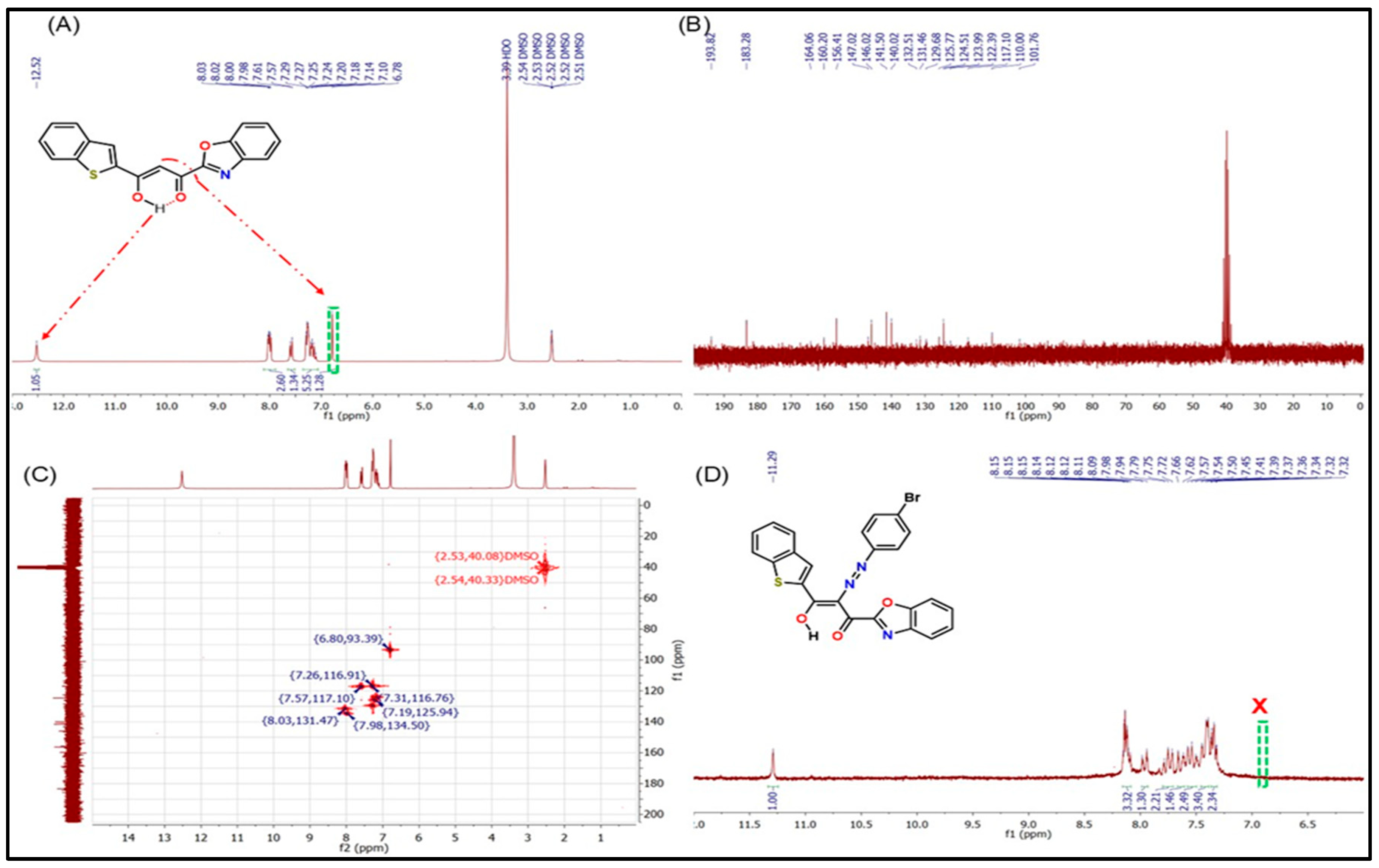

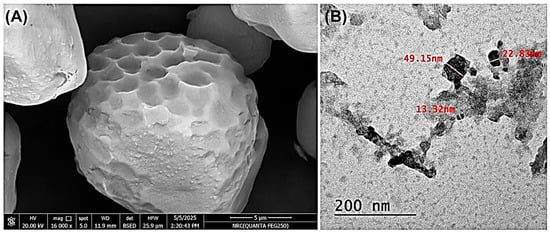

The morphological characteristics of the synthesized nanocellulose were investigated using both scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), as presented in Figure 3. The SEM image (Figure 3A) reveals irregular, micrometer-sized aggregates with relatively smooth surfaces and varied geometric forms. These aggregates suggest the formation of clustered nanostructures rather than individual fibrils, a common occurrence due to the inherent tendency of nanoparticles to agglomerate.

Figure 3.

(A) SEM and (B) TEM images of the cellulose nanoparticles.

To confirm the nanoscale nature of the material, high-resolution TEM analysis was conducted. The TEM image (Figure 3B) clearly illustrates the presence of discrete nanocellulose particles with sizes ranging from approximately 13 to 49 nm. These nanoparticles appear interconnected or slightly aggregated, supporting the observations from SEM and confirming successful nanoscale synthesis. The combination of both imaging techniques indicates that the nanocellulose exhibits a particle-based morphology with a strong tendency toward aggregation, which may be advantageous in certain applications, such as immobilization matrices or composite reinforcement.

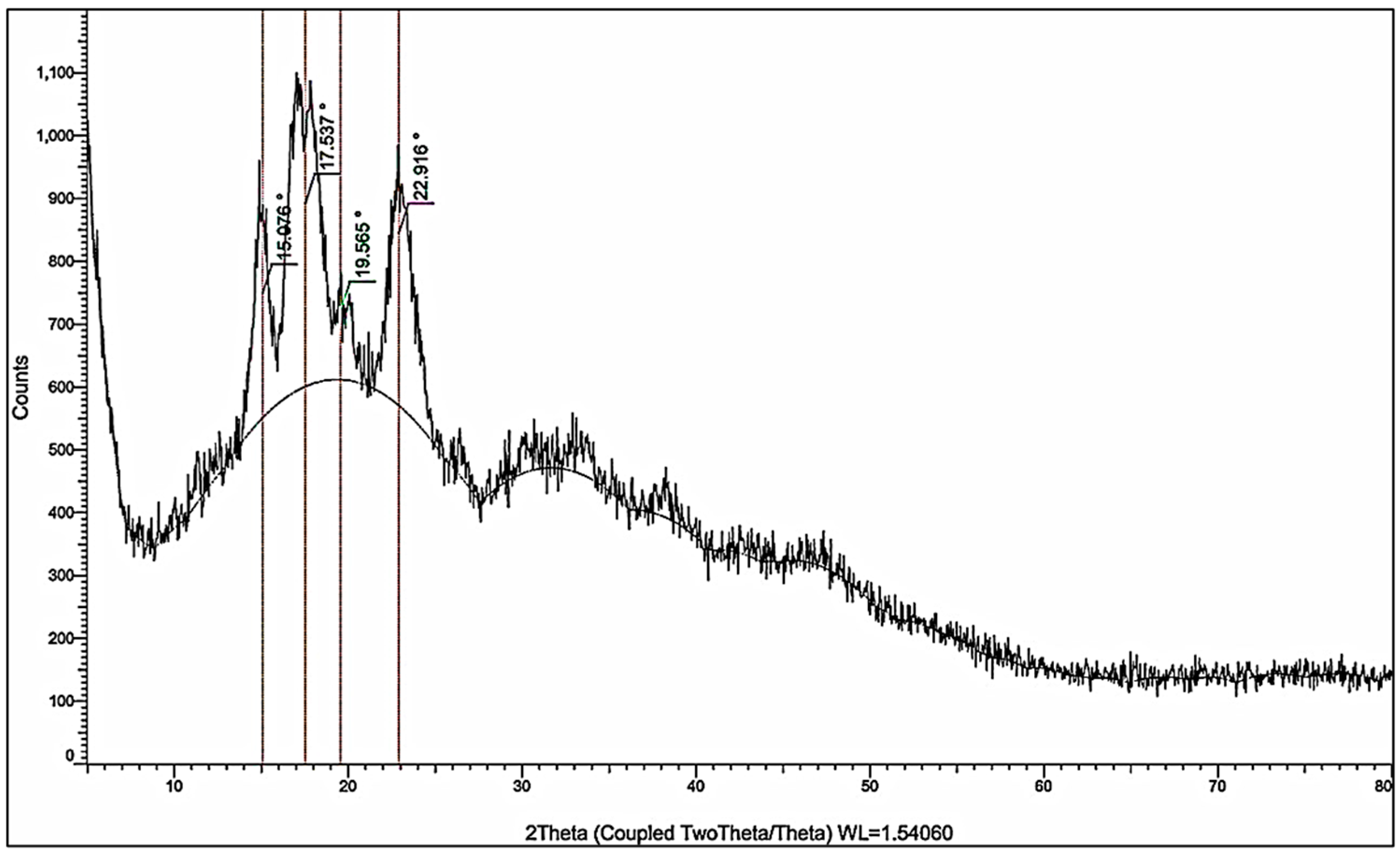

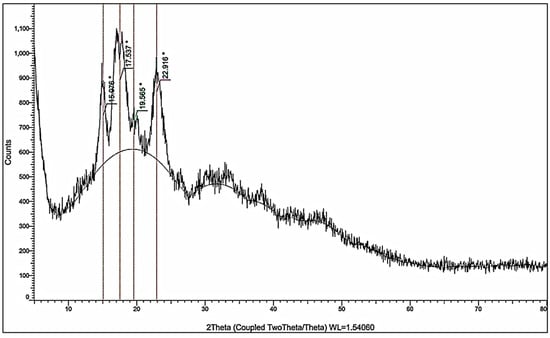

2.3.2. Crystallinity

The crystallographic structure of the prepared nanocellulose was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD). The diffraction pattern showed characteristic peaks at 2θ = 15.08°, 17.54°, 19.57°, and 22.92°, as shown in Figure 4, corresponding to interplanar spacings (d-values) of 5.87 Å, 5.05 Å, 4.53 Å, and 3.88 Å, respectively. These reflections are consistent with the crystalline lattice of cellulose I, specifically the cellulose Iβ allomorph, which is predominant in plant-derived nanocellulose. The most intense peak observed at 22.92° corresponds to the (200) plane of cellulose I, which indicates a high degree of orientation of the crystalline domains. The presence of minor peaks at lower angles, such as those at 15.08° and 17.54°, further confirms the identity of the cellulose crystalline phase.

Figure 4.

XRD pattern of the cellulose nanoparticles.

The Crystallinity Index (CrI) is calculated using the Segal method [23]:

where It is the intensity of the (200) plane at 22.92° (275.11) and Ia is the intensity at 19.57° (109.70), corresponding to the amorphous background which equals 60.1%. This value falls within the accepted range for partially crystalline nanocellulose materials, indicating moderate retention of the native crystalline structure. The average crystallite size is estimated using the Scherrer equation [24]:

D = (K λ)/(β cos θ)

D is the average crystallite size, K is a dimensionless shape factor (0.9), λ is the wavelength of the X-ray radiation used (Cu Ka = 0.154 nm), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak (0.7999° = 0.01396 Rad), and θ is the diffraction angle (22.916°). The calculated crystallite size (D) is 10.15 nm, and this confirms that the cellulose domains exist in the nanometric range, supporting the classification of the material as nanocellulose.

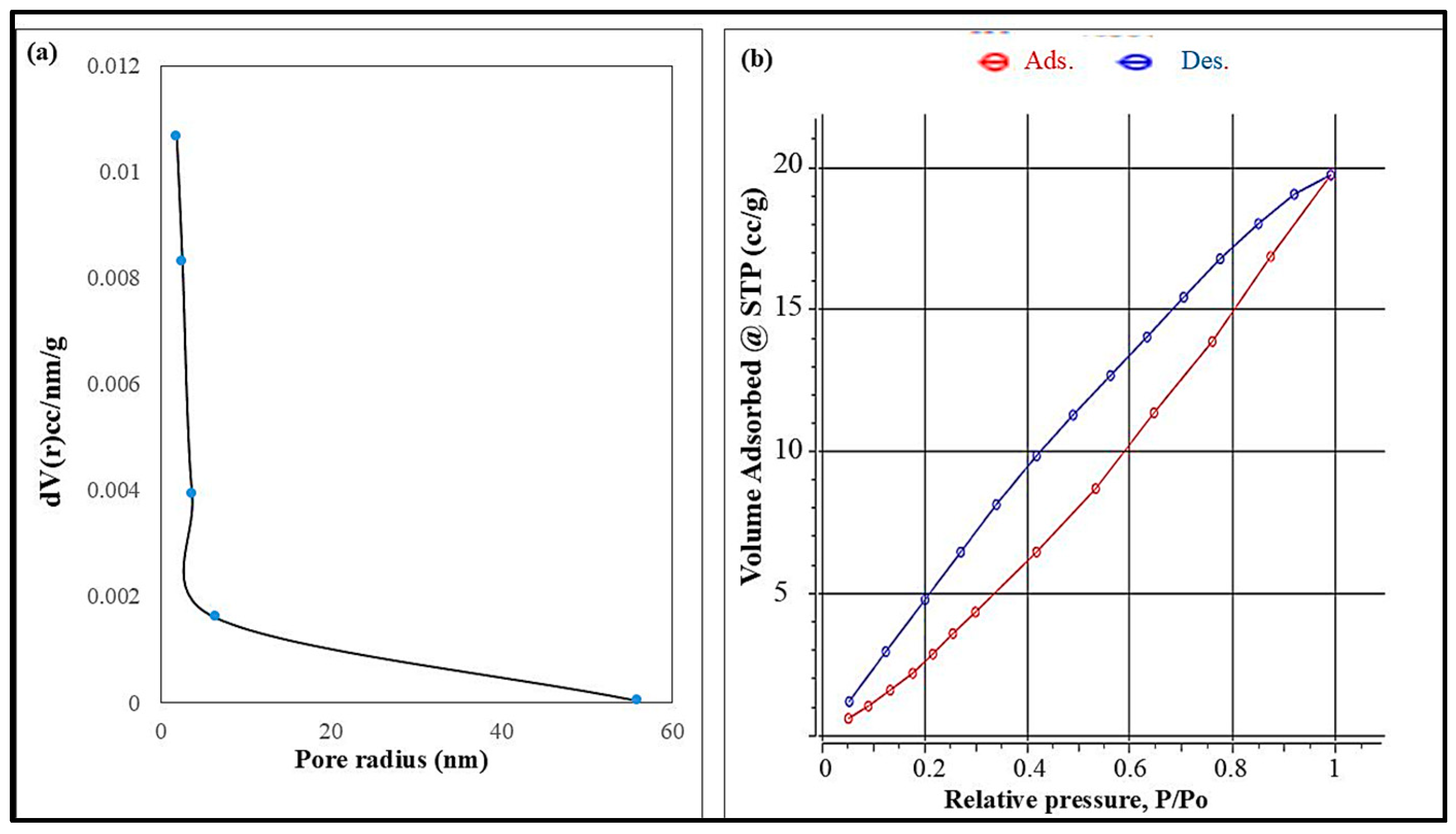

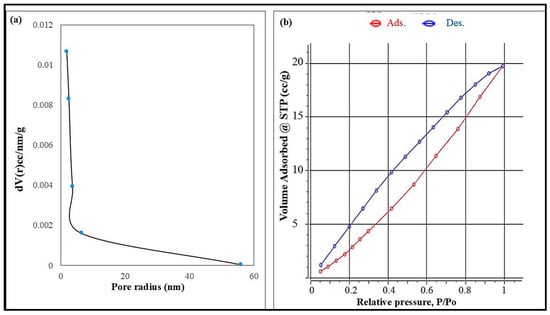

2.3.3. Surface Area and Porosity

The surface area of the produced nanocellulose was evaluated using nitrogen adsorption based on the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The analysis revealed a specific surface area of approximately 40.31 m2/g, reflecting the material’s porous nature and potential for surface interactions. Figure 5a represents the BJH pore diameter and pore volume of synthesized cellulose nanoparticles, which indicate the porous nature of cellulose nanoparticles. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of nanocellulose, as seen in Figure 5b, exhibits a type II profile with a narrow hysteresis loop, indicating multilayer adsorption and the presence of interconnected mesopores within the fibrillar network. The BET plot was derived from the adsorption branch of the isotherm, showing a linear relationship with a correlation coefficient of 0.8086, which confirmed the reliability of the data fit. The BET constant (C = 1.16) suggested moderate affinity between nitrogen molecules and the nanocellulose surface. These results highlight the material’s accessible surface characteristics, which are favorable for applications involving adsorption, surface modification, or interaction with target analytes in environmental or sensor-related fields.

Figure 5.

(a) BJH pore radius and (b) N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of the cellulose nanoparticles.

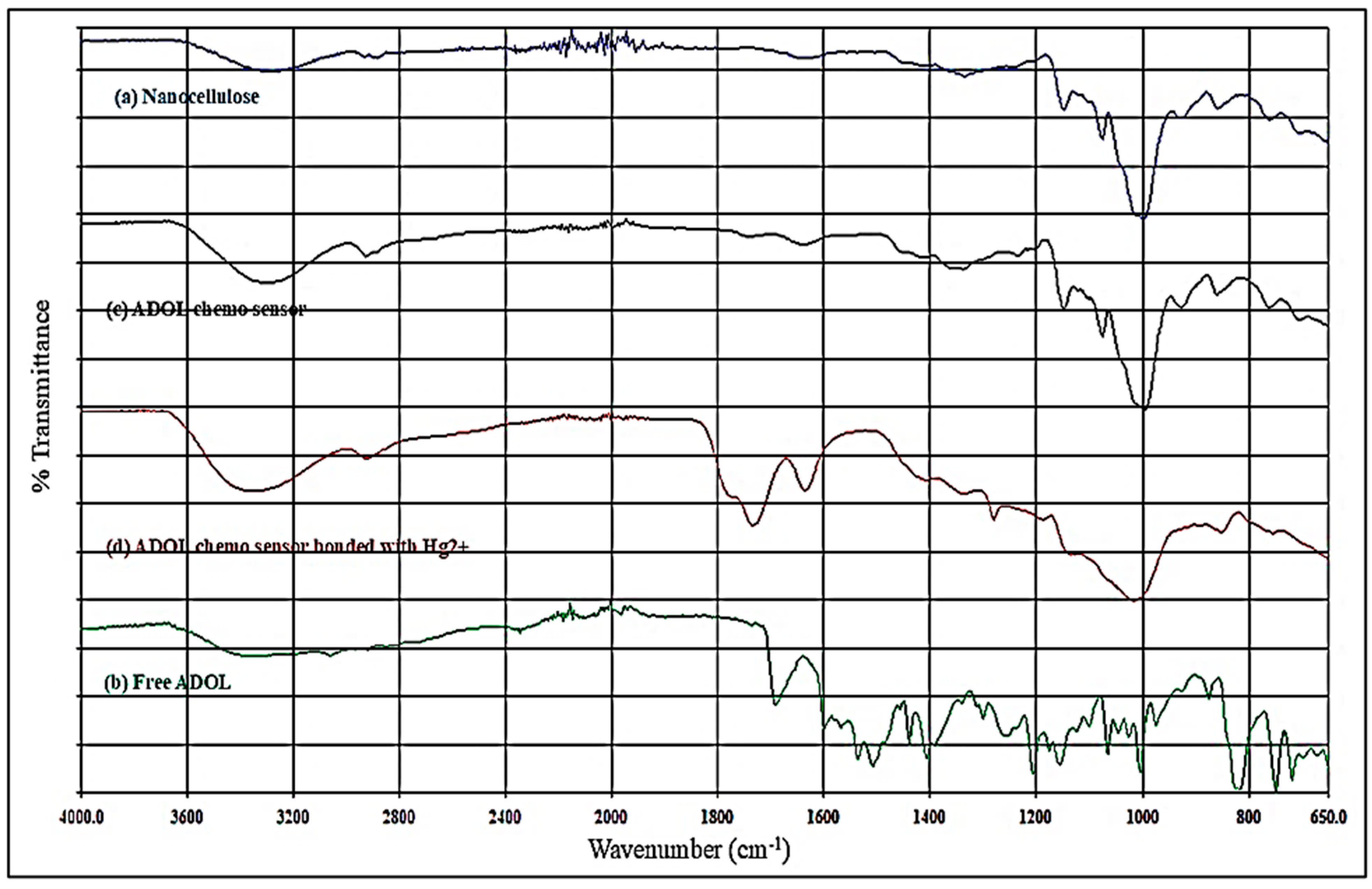

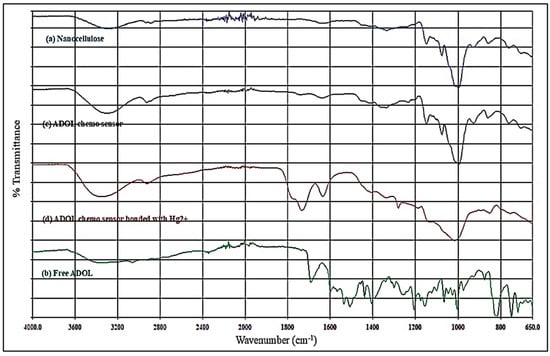

2.4. Structural Characterization of New Chemosensor (ADOL-Loaded Nanocellulose)

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (Figure 6) demonstrates the sequential modification from nanocellulose to the Hg2+-bound sensing material. The pristine nanocellulose spectrum exhibits a broad O–H stretching band at 3330–3400 cm−1, indicating extensive hydrogen bonding between surface hydroxyl groups, and C–H stretching near 2900 cm−1, together with a strong C–O–C vibration at 1030–1050 cm−1 from β-1,4-glycosidic linkages [25]. The free ligand shows a C=N imine stretch at 1600–1640 cm−1 and aromatic C=C bands between 1450 and 1600 cm−1, in agreement with reported Schiff-base IR features [19]. Upon immobilization onto nanocellulose, the O–H stretching band slightly red-shifts and decreases in intensity, implying hydrogen bonding or possible covalent interaction between ligand functional groups and cellulose hydroxyls. Simultaneously, aromatic and C=N absorptions remain prominent, confirming successful ligand attachment. Following Hg2+ binding, the C=N stretching band shifts toward lower wavenumbers, reflecting electron density withdrawal during imine nitrogen–metal coordination [26]. Additional broadening in the O–H region suggests secondary hydrogen bonding contributions to the binding process. Similar FTIR trends have been reported for nanocellulose-based mercury sensors, where metal–ligand complexation is accompanied by shifts in imine and hydroxyl-related vibrations [27].

Figure 6.

FTIR spectrum of (a) nanocellulose particles, (b) free ADOL, (c) ADOL chemosensor, and (d) ADOL chemosensor bonded with Hg2+.

2.5. Recognition Process of Hg2+ Using the ADOL Chemosensor

2.5.1. Chemosensing Optimization

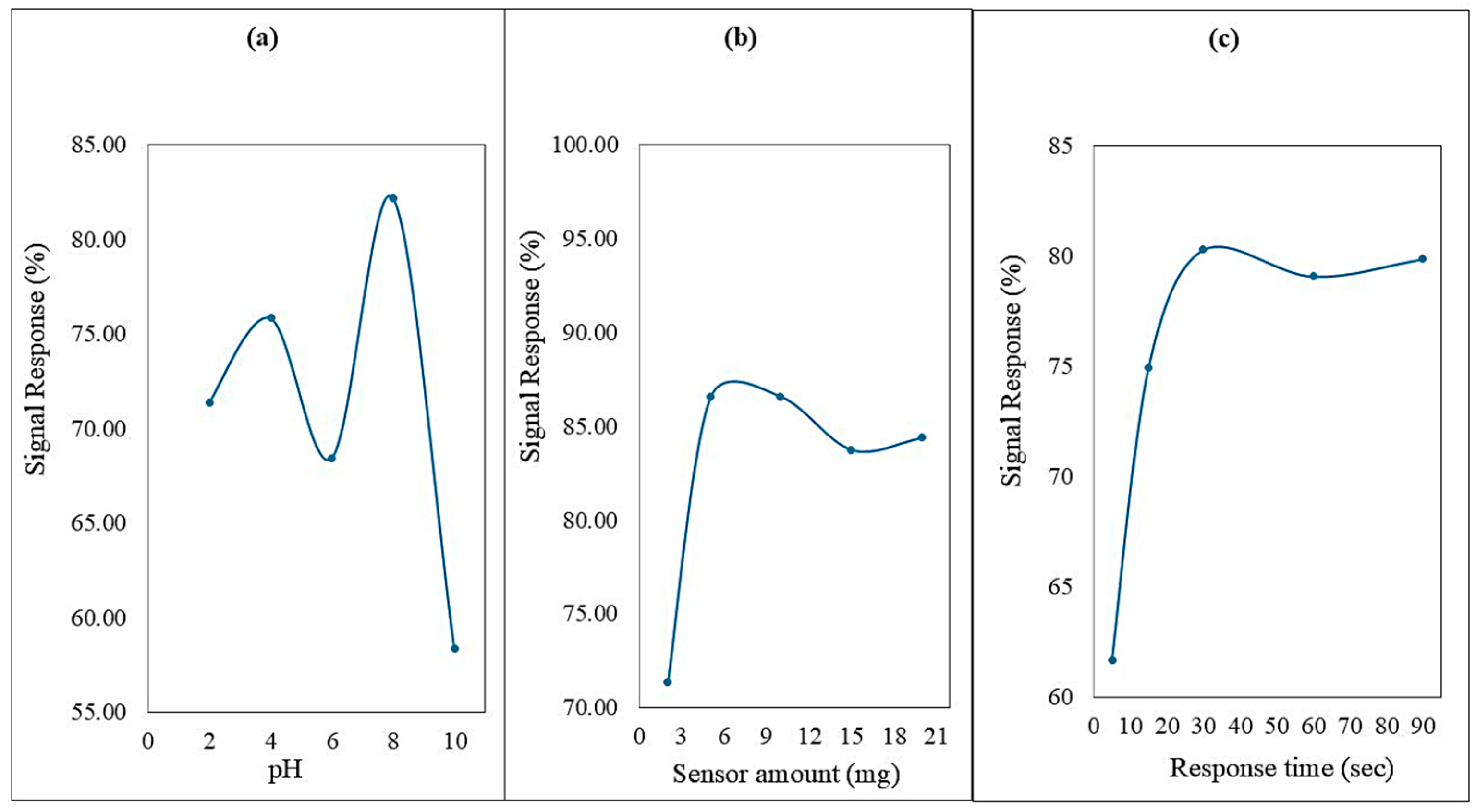

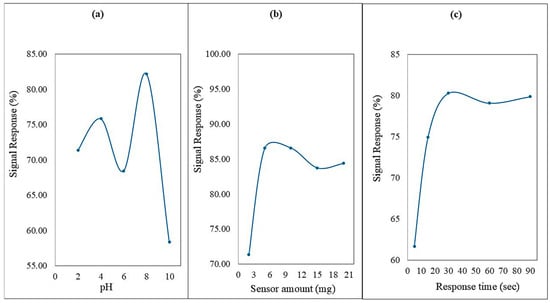

The performance of the ADOL chemosensor is influenced by multiple critical parameters, including the nature of the sensor support, operational temperature, pH levels, and contact time [28,29]. These factors significantly impact the absorbance signals, even when detecting trace amounts of metal ions through optical methods. Alterations in these variables affect the energy and charge-transfer mechanisms between the ADOL probe molecules and the sensor’s porous surface, ultimately influencing the sensitivity and performance of the detection system [30].

To determine the optimal pH for Hg2+ ion detection, solutions with varying pH levels were prepared, and their absorbance responses were measured at a fixed concentration of Hg2+ (Figure 7a). The highest absorbance signal was observed at pH 8, which was therefore selected as the optimum pH condition for further experiments.

Figure 7.

(a) The signal response for detecting Hg2+ ions using the ADOL chemosensor varies with pH. (b) The amount of ADOL chemosensor used affects the signal response for detecting Hg2+ ions. (c) The response time of the ADOL chemosensor for detecting Hg2+ ions.

To identify the ideal dosage of the ADOL chemosensor, different amounts ranging from 2 mg to 20 mg were tested at the selected pH. As depicted in Figure 7b, the absorbance intensity peaked at a sensor dose of 5 mg, which was then used in subsequent trials.

To evaluate the sensor’s response time, 50.0 µg L−1 of Hg2+ was introduced to a solution containing 5 mg of the ADOL chemosensor at pH 8. A rapid colorimetric response was observed within 5 s. Therefore, all absorbance measurements were consistently recorded after 90 s (Figure 7c).

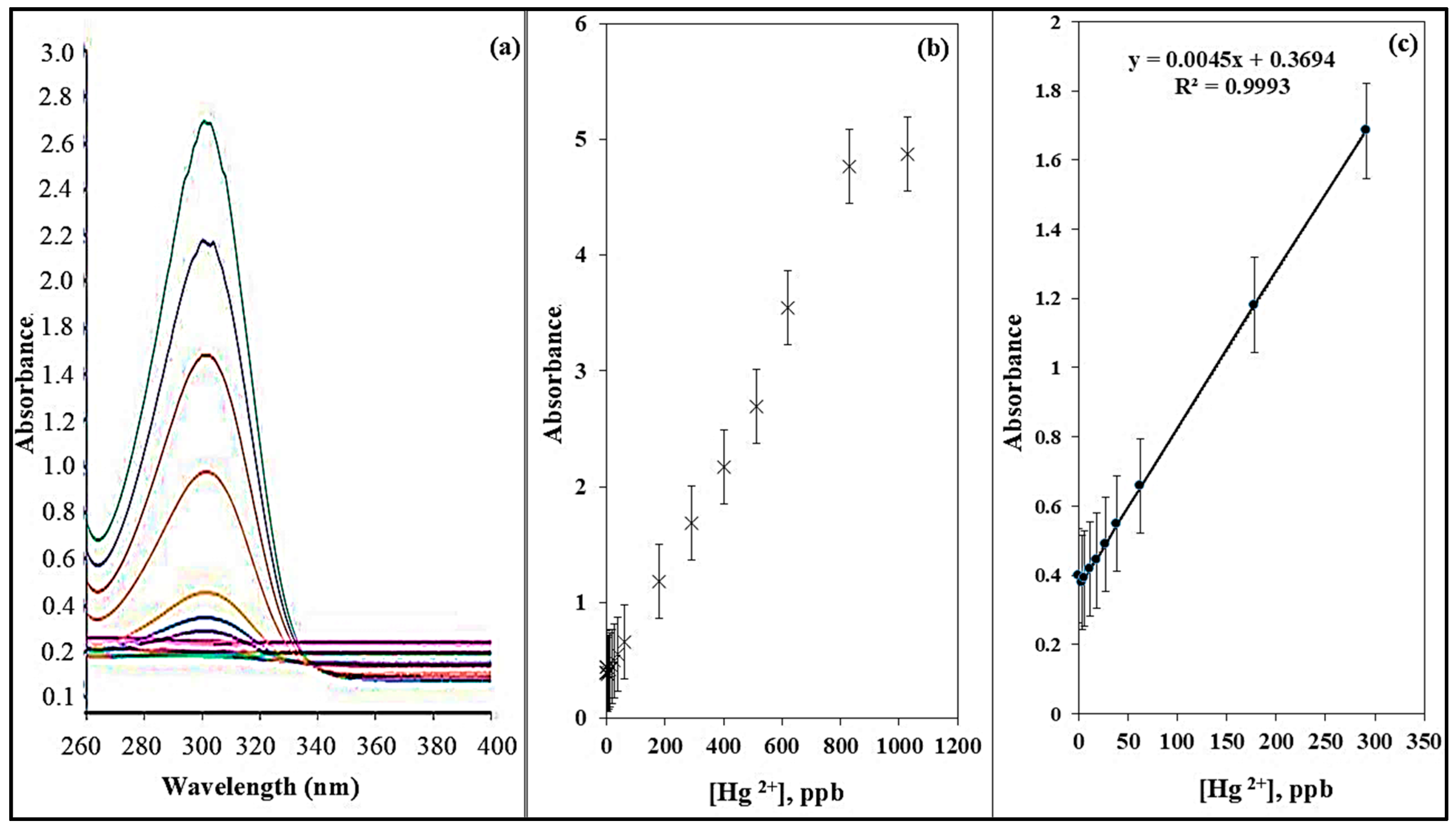

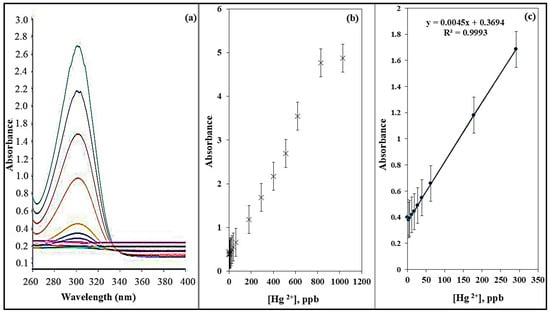

Figure 8a presents the absorbance spectra of the ADOL chemosensor under optimized conditions. A calibration curve was established (Figure 8b) by varying Hg2+ concentrations from 0 to 1.1 mg L−1 while maintaining a constant sensor dose of 5 mg at pH 8. The absorbance intensity at 301 nm was increased with rising Hg2+ concentrations. Figure 8c shows that at lower concentrations, a strong linear relationship was maintained, confirming the sensor’s high sensitivity for trace detection of Hg2+ ions. The limit of detection (LOD) and the limit of quantification (LOQ) for Hg2+ using this sensor were estimated to be 9.07 µg L−1 and 27.5 µg L−1, respectively. These were calculated using the formula LOD or LOQ = kSb/m, where Sb represents the standard deviation and m represents the slope of the linear calibration graph. The comparison of the Hg2+ detection limit with those reported for previously developed chemosensors is summarized in Table 1, showing that the ADOL chemosensor exhibits a lower detection limit than many sensors reported in the literature.

Figure 8.

(a) Absorption spectra, (b) calibration plot, (c) calibration curve of the ADOL chemosensor with various concentrations of Hg2+ ions.

Table 1.

Comparison between the ADOL chemosensor and previously reported sensors in terms of the sensitivity of Hg2+ ions.

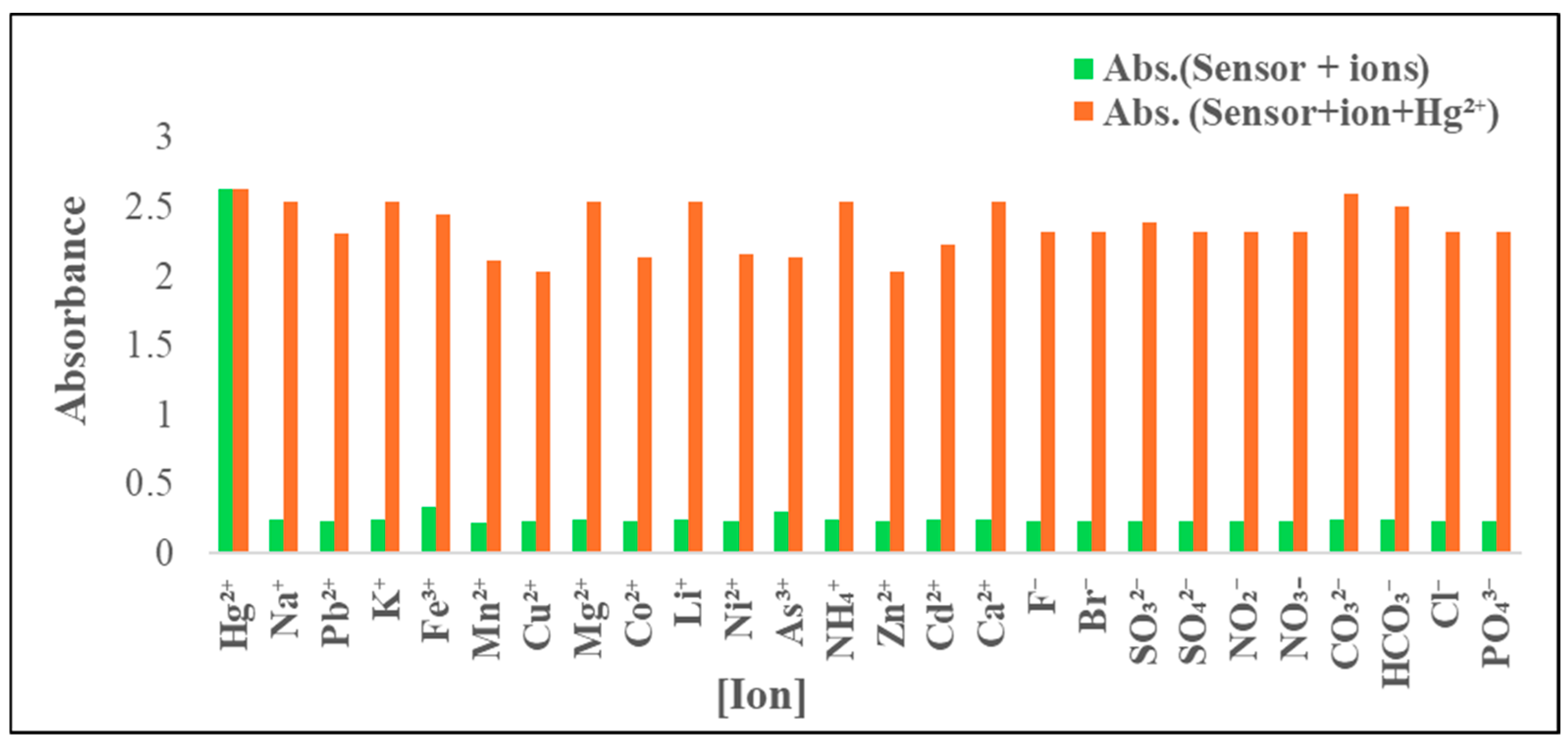

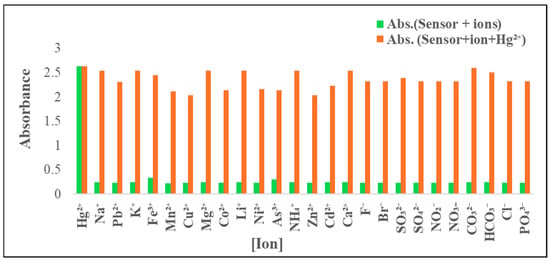

2.5.2. Interference

It was essential to evaluate how selectively the ADOL chemosensor detected the target ion (Hg2+) in the presence of other ions typically found in environmental samples. Competing ions may have either interacted with the ionophore component of the sensor or with Hg2+ itself, potentially reducing the diffusion efficiency and interfering with the detection process. The tolerance threshold was defined as the concentration at which an error of more than ±5.00% in absorbance was observed [42]. To assess this, absorbance measurements were taken before and after the addition of various potentially interfering cations (Na+, K+, Mg2+, NH4+, Ca2+, Pb2+, Fe3+, Mn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Li+, Ni2+, As3+, Zn2+, and Cd2+) and anions (F−, Br−, SO32−, SO42−, NO−, NO3−, CO32−, HCO3−, Cl−, and PO43−) to a test solution containing 0.5 mg L−1 Hg2+ and 5.0 mg of the ADOL chemosensor at pH 8. The spectral data indicated negligible interference from most ions, with only slight absorbance variations observed in the presence of Fe3+ and As3+ which were masked through 2 mL of ascorbic acid (10%). The absorbance responses of the chemosensor in the presence of all tested interfering ions are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Selectivity of ADOL chemosensor towards Hg2+ ions and other metal ions in absence (green bars) and presence of 0.5 mg L−1 (orange bars) at λabs. = 301 nm and pH = 8.

Table 2’s results clearly highlight the sensor’s outstanding selectivity for Hg2+, with minimal influence from competing ions. This high selectivity is attributed to the sensor’s strong binding affinity and specificity toward Hg2+, supported by the structural and resonance properties of the ionophore moiety. These results demonstrate the sensor’s strong potential for practical application in environmental monitoring of mercury ions.

Table 2.

The tolerance limit for interfering ions when detecting 0.5 mg L−1 Hg2+ ions with the ADOL chemosensor.

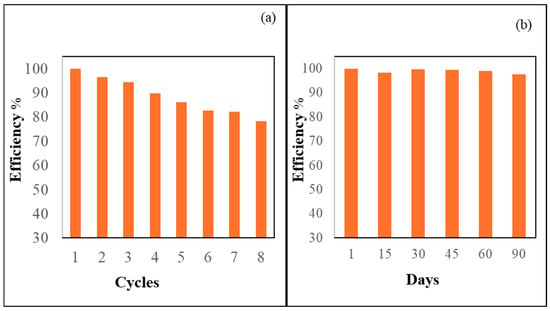

2.5.3. Reusability

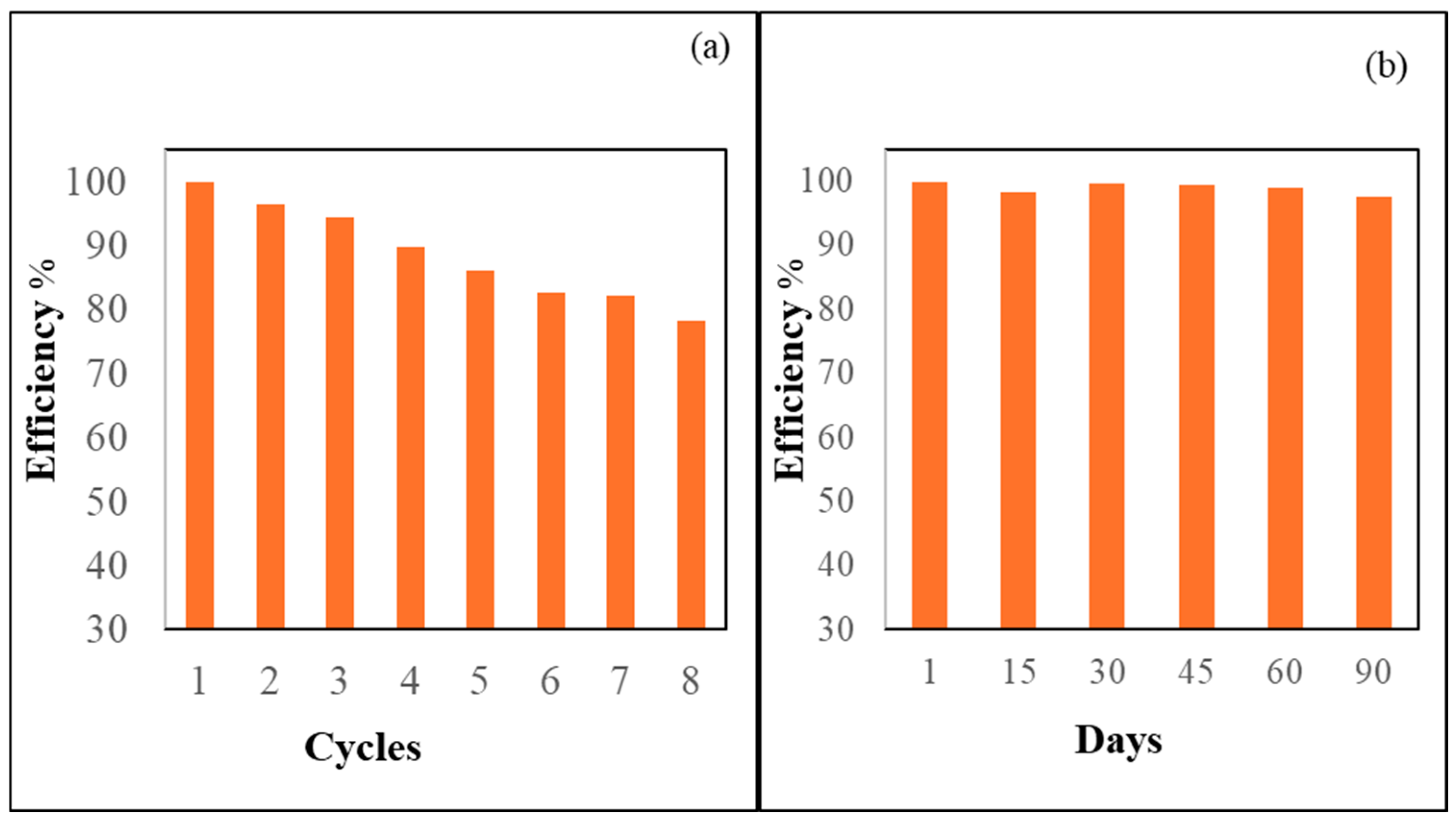

Evaluating the reusability of adsorbent material is essential to assess its economic feasibility and suitability for large-scale applications. For advanced functionalized materials to be viable, they must allow for efficient recycling and regeneration processes. Following the detection of Hg2+, the regeneration potential of the ADOL chemosensor was investigated. To restore its sensing capability, the spent ADOL material was treated with 0.1 M thiourea under acidic conditions for 5 h [43]. This treatment facilitated the removal of bound metal ions, effectively regenerating a “metal-free” probe surface. The regeneration process was repeated multiple times, after which the chemosensor was exposed again to a Hg2+ solution. This cycle was conducted eight times in total.

The sensor’s efficiency in each reuse cycle was quantified using the formula (A/Ao) % when recognizing the Hg2+ ions in each recycling. The difference between the original absorbance, Ao, and the absorbance of Hg2+ ions after being reused was examined. As illustrated in Figure 10a, the ADOL chemosensor retained approximately 86% of its original sensing performance even after five regeneration cycles. This result indicates that the material maintained substantial functionality and adsorption efficiency upon reuse, supporting its application in repeated real-sample analyses.

Figure 10.

(a) The recycling of the ADOL chemosensor. (b) The stability of the ADOL chemosensor over 90 days.

Moreover, the preparation method employed for the ADOL chemosensor demonstrated superior stability and reliability compared to other immobilization techniques, reinforcing the practicality of this sensing platform.

2.6. Stability of the ADOL Chemosensor

One of the primary challenges in designing optical chemosensors lies in achieving high long-term stability. The ADOL chemosensor demonstrated exceptional durability, positioning it as a highly promising candidate for practical applications. To assess its shelf-life performance, the sensor was stored for several months and periodically evaluated. Over a 90-day period, the absorbance spectra exhibited minimal variation, as shown in Figure 10b, indicating excellent preservation of its optical properties. Notably, this stability was achieved without the use of any surface-modifying agents, and no detectable leaching of the chromophore was observed during storage. These results underscored the suitability of the ADOL chemosensor for prolonged use. The incorporation of nanocellulose, with its biocompatible organic structure, combined with the embedding of ADOL probe molecules within the porous matrix, contributed significantly to the sensor’s storage stability. Unlike conventional sensor systems that rely on electrostatic interactions and external surface modifications to retain sensing elements, the ADOL sensor’s design—based on the direct physical integration of the probe—offers superior robustness. This structure enhances not only the sensor’s reliability and lifespan but also its sensitivity, selectivity, and overall analytical performance. This innovative approach presents a practical and efficient sensing platform suitable for extended analytical applications [44].

2.7. Application to a Real Wastewater Sample

The performance of the developed ADOL chemosensor for mercury detection was evaluated using real wastewater samples collected from four industrial sources representing diverse matrices—surfactants (Galaxy Chemicals, Suez, Egypt), a food oil manufacturer, a fertilizer manufacturer, and a petrochemical manufacturer, all located in Suez, Egypt. This study aimed to validate the ADOL chemosensor’s recovery, precision, and matrix tolerance, benchmarked against inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) with vapor generation.

As presented in Table 3, unspiked effluent samples from all sites yielded values below the limit of quantification (BLQ), confirming minimal or non-detectable background levels of mercury. This highlights the applicability of the ADOL chemosensor for trace-level screening and confirms the absence of pre-existing contamination in the tested matrices.

Table 3.

Determining Hg2+ in four different effluent wastewaters using ADOL chemosensor.

Across the spiked concentration levels (65, 130, and 260 µg L−1), the ADOL chemosensor exhibited strong performance with recovery percentages ranging from 97.31% to 102.74%, in close agreement with those obtained by ICP-OES (98.66% to 103.10%). At the lowest concentration (65 µg L−1), recoveries remained within acceptable analytical ranges for all samples, despite being near the ADOL chemosensor’s quantification limit (27.5 µg L−1). At higher concentrations (130 and 260 µg L−1), the proposed ADOL chemosensor maintained its reliability, with recoveries closely tracking those of the ICP-OES system, with a range of 97.82–102.65% and 98.66–103.1% for the ADOL chemosensor and ICP-OES system, respectively.

The precision of the ADOL chemosensor was consistently high, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) across all tests remaining below 2%, attesting to the method’s repeatability. This level of precision is comparable to that of ICP-OES, supporting the reproducibility of the optical platform.

The results validate that the ADOL chemosensor is not only capable of detecting mercury with high accuracy but also demonstrates robustness in handling complex industrial effluents. The sensor’s high correlation with ICP-OES outcomes, despite the simplicity and cost-effectiveness of the platform, indicates that it could be implemented for routine mercury monitoring, particularly in resource-limited settings or for rapid field deployment. This work underlines the potential for optical nanotechnology to complement, and in some contexts replace, conventional instrumentation in environmental surveillance programs.

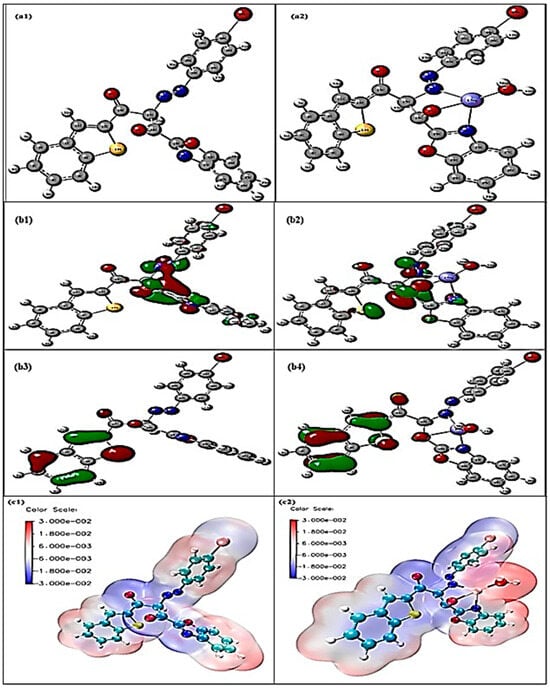

2.8. DFT Support for the Proposed Sensing Mechanism

Density Functional Theory (DFT) computational investigations provide crucial molecular-level insights into the electronic structure, binding mechanisms, and spectroscopic properties of the ADOL chemosensor and its mercury complex. These theoretical studies complement experimental findings and offer predictive capabilities for sensor optimization and performance enhancement.

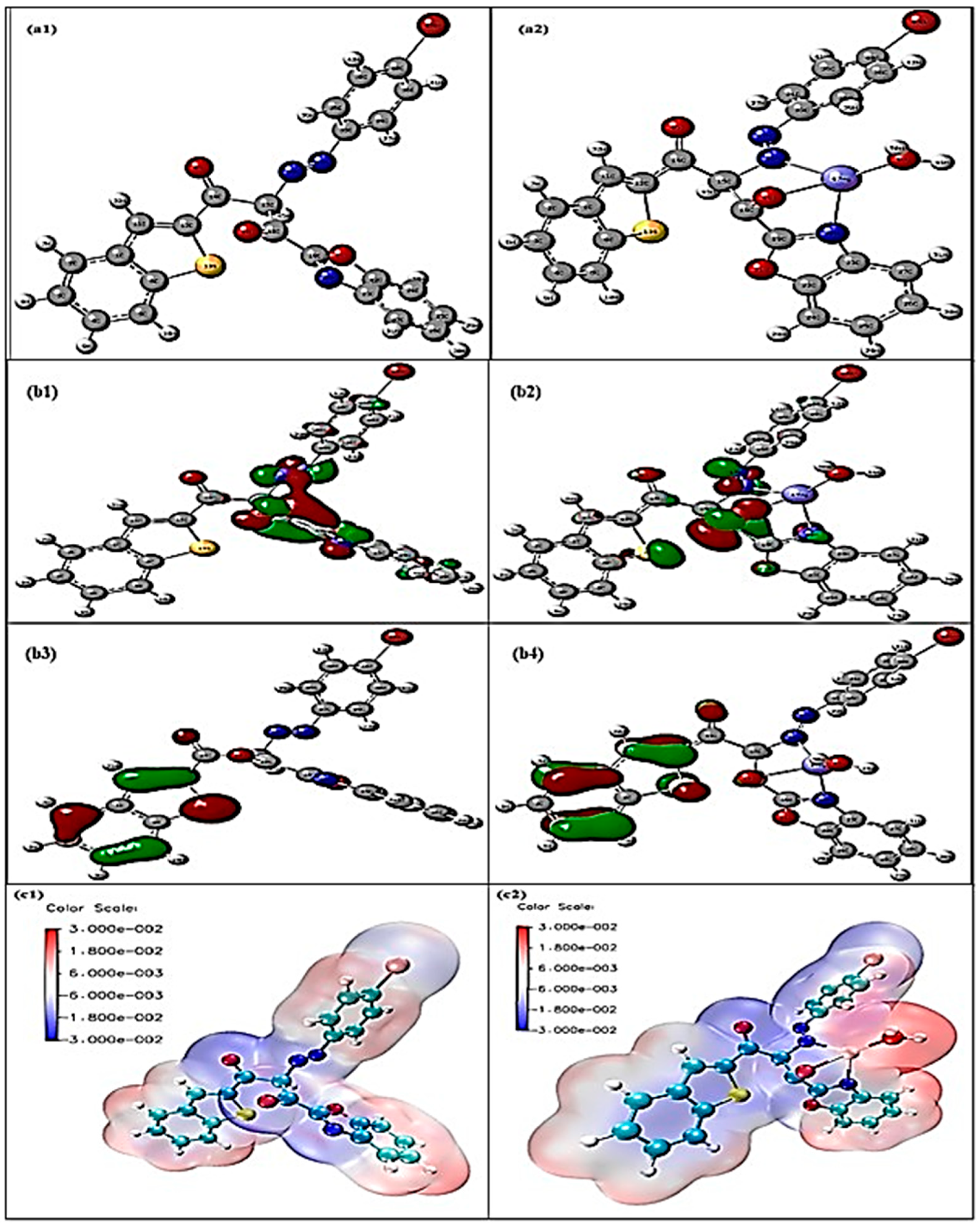

2.8.1. Optimized Molecular Geometries

Computational geometry optimization is performed using the Gaussian 09 package for the free Schiff base at the B3LYP/6-311G (d, p) level and B3LYP/ECP78MWB for the mercury (II) complex, as shown in Figure 11a1,a2. The free ligand displays a nearly planar conformation with extended π-conjugation through the aromatic rings and azomethine group. The C=N bond length (1.29309 Å) lies within the typical imine range, while aromatic C–C (1.382–1.417 Å), O–H (0.975 Å), and benzothiazole parameters (C–S = 1.752 Å, C–N = 1.386 Å, N-N = 1.244Å, AND C-O = 1.204 Å) agree with reported values, confirming the reliability of the model. Upon complexation, Hg (II) binds via two azomethine nitrogens and two deprotonated phenolic oxygens, generating a distorted tetrahedral geometry. The Hg–N (2.192–2.198 Å) and Hg–O (2.049–2.202 Å) bond lengths are consistent with experimental data. Coordination leads to elongation of the C=N bonds (to 1.333 Å, N-N = 1.272 Å) and C–O bonds (to ~1.294 Å), reflecting electron donation to the metal. The ligand backbone twists significantly, with a dihedral angle of ~77° between the phenolic planes. Bond angles around Hg deviate from ideal. Both the free ligand and complex converge to true minima without imaginary frequencies, confirming structural stability. The geometric parameters and distortions observed are in excellent agreement with reported mercury–Schiff base complexes.

Figure 11.

(a1) Optimized structure of ADOL, (a2) Hg-ADOL structure. (b1). LUMO of ADOL, (b2) LUMO of Hg-ADOL, (b3) HOMO of ADOL, (b4) HOMO of Hg-ADOL. (c1) MESP map for ADOL, (c2) MESP map for Hg-ADOL.

2.8.2. Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) Analysis

Frontier molecular orbital analysis provides important insights into the electronic changes, as shown in Figure 11b1,b2, that occur upon mercury coordination in nanocellulose-immobilized sensors. For the free ligand, the HOMO is primarily localized on aromatic rings and donor atoms (N and O), while the LUMO extends across the conjugated framework, supporting charge-transfer processes essential for sensing. The calculated HOMO–LUMO gap of the free ligand is about 3.65 eV, indicating moderate stability with sufficient reactivity for coordination. Upon binding with mercury (II), the HOMO acquires mixed ligand–metal character while the LUMO remains largely ligand-centered but with enhanced electron-accepting ability. This coordination reduces the HOMO–LUMO gap to 2.60 eV, reflecting stronger orbital interactions, increased polarizability, and improved charge-transfer capacity. These electronic modifications explain the enhanced sensitivity and selectivity of the ligand toward mercury ions. The orbital overlap confirms coordination through nitrogen and oxygen donor atoms, consistent with the HOMO distribution of the free ligand, while the reversibility of these changes highlights the potential for sensor reusability. Overall, the observed gap reduction provides a reliable theoretical basis for the design and optimization of nanocellulose-based mercury sensors for environmental monitoring applications.

2.8.3. Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MESP) Maps

Electrostatic potential analysis as per Figure 11c1,c2 of the ligand immobilized in nanocellulose shows highly negative regions at the oxygen and nitrogen atoms, identifying them as the principal donor centers responsible for metal coordination. Upon binding with Hg2+, these negative potentials diminish significantly as electron density is transferred to the metal, while a distinct positive region develops around the Hg center, reflecting its electrophilic nature within the complex. This clear redistribution of charge provides direct evidence of metal–ligand interaction and confirms that the sensor matrix, based on nanocellulose-immobilized ligand, effectively binds mercury ions. The comparative ESP surfaces thus support the proposed sensing mechanism, where the electronic reorganization accompanying Hg2+ coordination underpins the sensitivity and selectivity of the optical sensor for mercury determination in industrial water. Importantly, this electronic shift is consistent with the observed optical response, where coordination-induced changes in the ligand’s electronic environment translate into a measurable signal, validating the sensor’s practical performance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Materials

All reagents and chemicals used throughout this work were of pure analytical grade. Demineralized (DM) water was used to prepare all solutions. Cellulose powder (CAS NO 9004-34-6) was obtained from Central Drug House (P) LTD (New Delhi, India). Sodium hydroxide pellets, potassium chloride, sodium acetate, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, mercuric nitrate standard, sodium sulfite, and acetone were obtained from Scharlab (Barcelona, Spain). Sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, acetic acid, sodium hypochlorite solution 10%, iron nitrate standard, arsenic nitrate standard, and lead nitrate standard were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK). Sodium bicarbonate and sodium carbonate were obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Dionex Combined Seven Anion Standard II, (fluoride 20 mg/L; chloride 100 mg/L; nitrite 100 mg/L; bromide 100 mg/L; nitrate 100 mg/L; phosphate 200 mg/L; sulfate 100 mg/L), and Dionex™ Combined Six Cation Standard (lithium chloride, sodium chloride, ammonium chloride, potassium chloride, magnesium chloride, calcium chloride) were obtained from Thermo Scientific (USA). All chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich and used without further purification for preparation of 1-(benzothiophenyl)-3-(benzooxazolyl)-2-((4- bromophenyl)diazenyl) propane-1,3-dione (azo-dione ligand, ADOL).

3.2. Apparatus

DM water was generated from a water purification system from Merck model Milli-Q SQ 2Series. The absorbance measurements were carried out by PerkinElmer UV-Vis spectrophotometer model LAMBDA 365+ (Waltham, MA, USA)). The IR spectrum was carried out by PerkinElmer FTIR spectrophotometer model Spectrum100 with universal attenuated total reflectance accessory (UATR). Metal analyses were carried out using PerkinElmer flame atomic absorption spectrometer, model PinAAcle 500. Surface area characterization was carried out through BET analysis, or Brunauer–Emmett–Teller analysis by Quantachrome surface area analyzer model NOVA Touch LX4 (Boynton Beach, FL, USA)) at National Research Center, Giza, Egypt. Morphology characterization was carried out through SEM analysis by Thermo Fischer Scientific SEM model Quanta FEG 250 and TEM analysis by JEOL TEM model JEM-2100 HRT (JEOL, Japan) at National Research Center, Giza. Structural characterization was carried out through XRD analysis by Bruker XRD model D8 Advance (Karlsruhe, Germany)) at National Research Center, Giza. Sample measurement was conducted using Agilent 5100 Synchronous Vertical Dual View (SVDV) ICP-OES (Mulgrave, Australia) with Agilent Vapor Generation Accessory VGA 7 at National Research Center, Giza, Egypt.

3.3. Preparation of Nanocellulose

Nanocellulose was obtained by acid hydrolysis adding 35% sulfuric acid to the cellulose powder with a ratio of 1: 7 (Wt./Wt.) for 1 h at 45 °C then conducting sonication for 30 min to hydrolyze cellulose to nanocellulose. Following sulfuric acid hydrolysis, the nanocellulose suspension was diluted with DM water and purified using a stirred ultrafiltration cell (Amicon®, Millipore) (Bedford, MA, USA) equipped with a polysulfone membrane. The suspension was subjected to repeated washing/diafiltration cycles with DM water under compressed air pressure (≈4 bar.). Washing continued until the permeate reached neutral pH and gave a negative test for sulfate ions with barium chloride solution, confirming the complete removal of residual sulfuric acid and soluble by-products. The purified nanocellulose was then collected and dried in oven at 80 °C for 4 h and stored for further analysis [45].

3.4. Preparation of ADOL

3.4.1. Overview

The key starting materials used in this study including Ethyl-2-((Benzo[b]thiophenyl)) pyruvate (2) and 1-(Benzo[b]thiophenyl)-3-(benzo[d] oxazolyl) propane-1,3-dione (BTBOPD) were obtained from our previous work [19].

3.4.2. Synthesis of 1-(Benzothiophenyl)-3-(benzooxazolyl)-2-((4-bromophenyl)diazenyl) Propane-1,3-dione (Azo-Dione Ligand, ADOL)

A solution of 4-bromoaniline (1.72 g, 0.01 mol) was prepared by dissolving it in a combination of concentrated hydrochloric acid plus water (10 mL, 1:1). It was cooled to room temperature and then, while stirring, a cold aqueous solution of NaNO2 (0.69 g, 0.01 mol in 5 mL water) was gradually added, making sure to keep the temperature below 5 °C. Simultaneously, a solution of BTBOPD was prepared by dissolving 0.01 mol (5.4 g) of the compound in 50 mL of ethanol, followed by the addition of 5 g of sodium acetate with stirring for 30 min. The chilled diazotized solution was gradually introduced into a cooled mixture containing BTBOPD. The mixture was stirred continuously for an hour, after which the resulting solid was separated by filtration, rinsed with water, dried, and then recrystallized from ethanol to yield the desired product. It was obtained as a dark orange powder (1.39 g, 73%): m.p. 267–269 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3462 (m, br, O-H), 3097 (m, br, aromatic C-H), 1738 (s, sh, C=O), 1603 (w, sh, oxazole C=N), 1533 (m, sh, aromatic C=C), 1460 (m, sh, Azo N=N), 1353 (w, sh, thiophen C-S-C), 1121 (m, sh, oxazole C-O-C), 867 (m, sh, oxazole ring), 750 (s, sh, thiophen C-S). 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.29 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.09 (m, 3H), 7.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.46–7.39 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.31 (m, 2H). CI(NH3)-MS, m/z (Fragment): 522.2 (M (Br79) + NH4+), 524.2 (M (Br81) + NH4+), 504.2 (M (Br79) + H+), 506.2 (M (Br81) + H+), and 424.2 (M+ ─ Br). Anal. Calcd. for C24H14BrN3O3S (503.36 g/mol): C, 57.15; H, 2.80; N, 8.33; S, 6.36%. Found: C, 56.97; H, 2.82; N, 8.26; S, 6.27%.

3.5. Preparation of ADOL Chemsensor

For the fabrication of the ADOL chemosensor, a direct immobilization approach was employed. Initially, 50 mg of 1-(benzothiophenyl)-3-(benzooxazolyl)-2-((4-bromophenyl) diazenyl) propane-1,3-dione (ADOL) was mixed with 1.0 g of cellulose nanorods in acetone and vigorously stirred for 24 h. The resulting mixture was then filtered to remove excess solvent. Upon filtration, the platform assumed a faint pink hue, indicating successful attachment of the ADOL chromophore onto the surface of the nanocellulose scaffold. This step was iterated multiple times to ensure comprehensive filling of all pores on the carrier. Finally, the ADOL chemosensor underwent a drying period of 12 h at 60 °C to achieve optimal performance [45].

3.6. Construction of Calibration Curve

The ADOL chemosensor was employed to determine Hg2+ under an optimum pH value (pH 8). Different concentrations of Hg2+ were mixed with aqueous solutions, resulting in a total volume of 10 mL. ADOL chemosensor was present in every single solution, each containing 5 mg. Thorough mixing was ensured by sonication of the solutions for 10 s. UV–vis spectrometry analysis was used to determine the absorbance of the solutions after allowing sufficient time for equilibration.

3.7. Determination of Hg2+ in Industrial Wastewater

Hg+2 was analyzed in samples collected from the effluent treatment plants of 4 different industries (surfactants, fertilizers, oils, and petrochemicals industries) by direct spectrophotometric method and by standard addition method. A comparison was conducted between the results obtained from each determination using the ICP-optical emission spectroscopy (OES) method and the ADOL chemosensor.

4. Conclusions

A novel chemosensor was successfully synthesized through a green approach for the detection of trace levels of Hg2+ ions in aqueous solutions using the specialized ADOL chromophore. The sensor demonstrated a clear and linear relationship between absorbance intensity and Hg2+ concentration under optimized conditions. This method showed exceptional sensitivity and high selectivity for Hg2+ detection. When applied to industrial wastewater samples, the ADOL chemosensor achieved high recovery rates and low relative standard deviation values, confirming its accuracy, precision, and reliability in real-world analytical applications. Additionally, the sensor exhibited excellent reusability, maintaining 86% efficiency after five regeneration cycles using 0.1 M thiourea. Overall, this green, efficient, and cost-effective sensing platform presents a promising tool for monitoring mercury contamination in various industrial wastewater samples with high sensitivity and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Y.E., R.M.K., R.F.M.E., and A.S.; methodology, M.A.-E.B., N.Y.E., R.F.M.E., and A.S.; software, M.R.E. and S.S.A.; validation, N.Y.E., R.M.K., and A.S.; formal analysis, M.R.E. and S.S.A.; investigation, M.A.-E.B., N.Y.E., R.F.M.E., and R.M.K.; resources, N.Y.E.; data curation, R.M.K., R.F.M.E., and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-E.B., N.Y.E., M.R.E., S.S.A., R.M.K., R.F.M.E., and A.S.; writing—review and editing, N.Y.E., R.M.K., R.F.M.E., and A.S.; visualization, M.R.E. and S.S.A.; supervision, N.Y.E., R.M.K., and A.S.; project administration, N.Y.E.; funding acquisition, N.Y.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2602).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mohamed Abd-El Baset was employed by the company Galaxy Chemicals Egypt (S.A.E). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kotnala, S.; Tiwari, S.; Nayak, A.; Bhushan, B.; Chandra, S.; Medeiros, C.R.; Coutinho, H.D.M. Impact of heavy metal toxicity on the human health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 987, 179785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kabir, E.; Jahan, S.A. A review on the distribution of Hg in the environment and its human health impacts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 306, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, B.R.; Jagadeesha, P.B.; Salmataj, S.A. Heavy metal contamination and its impact on the food chain: Exposure, bioaccumulation, and risk assessment. CyTA-J. Food 2025, 23, 2438726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P.; Saravanan, V.; Rajeshkannan, R.; Arnica, G.; Rajasimman, M.; Baskar, G.; Pugazhendhi, A. Comprehensive review on toxic heavy metals in the aquatic system: Sources, identification, treatment strategies, and health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, H.; Sadeek, S.; Mahmoud, A.R.; Zaky, D. Comparison of AAS, EDXRF, ICP-MS and INAA performance for determination of selected heavy metals in HFO ashes. Microchem. J. 2016, 128, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Wu, W. Emerging nanosensor technologies for the rapid detection of heavy metal contaminants in agricultural soils. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 7846–7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakayode, S.O.; Walgama, C.; Fernand Narcisse, V.E.; Grant, C. Electrochemical and colorimetric nanosensors for detection of heavy metal ions: A review. Sensors 2023, 23, 9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rai, S.; Khan, H.; Shakeel, M.; Vimal, A.; Vishvakarma, R.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Nanosensors for Heavy Metal Pollution Detection in Agricultural System. In Nanobiosensors for Agricultural and Other Related Sectors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bari, A.; Aslam, S.; Khan, H.U.; Shakil, S.; Yaseen, M.; Shahid, S.; Yusaf, A.; Afshan, N.; Shafqat, S.S.; Zafar, M.N. Next-Generation Optical Biosensors: Cutting-Edge Advances in Optical Detection Methods. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 8319–8345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R.J.; Martini, A.; Nairn, J.; Simonsen, J.; Youngblood, J. Cellulose nanomaterials review: Structure, properties and nanocomposites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3941–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misenan, M.S.M.; Akhlisah, Z.N.; Shaffie, A.H.; Saad, M.A.M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F. 8—Nanocellulose in sensors. In Industrial Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Nanocomposites; Sapuan, S.M., Norrrahim, M.N.F., Ilyas, R.A., Soutis, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 213–243. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, M.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Asim, M. Nanocellulose: Preparation methods and applications. In Cellulose-Reinforced Nanofibre Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, S.; Peinado, S.; Morillas-Gutiérrez, F.; La Rubia, M.D.; Moya, A.J. Nanocellulose from Agricultural Wastes: Products and Applications—A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendicho, C.; Lavilla, I.; Pena-Pereira, F.; de la Calle, I.; Romero, V. Nanomaterial-integrated cellulose platforms for optical sensing of trace metals and anionic species in the environment. Sensors 2021, 21, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Iglesias, Y.; Bermejo-Barrera, P.; García-Deibe, A.M.; Fondo, M.; Sanmartín-Matalobos, J. Immobilization on Cellulose Paper of a Chemosensor for CdSe-Cys QDs. Chem. Proc. 2022, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritu; Narang, U.; Kumar, V. Heavy Metal Detection with Organic Moiety-Based Sensors: Recent Advances and Future Directions. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Knight, V.F.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Jenol, M.A.; Misenan, M.S.M.; Janudin, N.; Kasim, N.A.M.; Shukor, M.F.A.; Ilyas, R.A.; Asyraf, M.R.M. The frontiers of functionalized nanocellulose-based composites and their application as chemical sensors. Polymers 2022, 14, 4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaarawy, R.F.M.; Janiak, C. Antibacterial susceptibility of new copper (II) N-pyruvoyl anthranilate complexes against marine bacterial strains–In search of new antibiofouling candidate. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.K.; El-Tamany, S.H.; El-Shaarawy, R.F.; El-Deen, I.M. Synthesis and investigation of mass spectra of some novel benzimidazole derivatives. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2008, 27, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, N.S.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M. Novel aminothiazolyl-functionalized phosphonium ionic liquid as a scavenger for toxic metal ions from aqueous media; mining to useful antibiotic candidates. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 281, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaarawy, R.F.M.; Tadros, H.R.Z.; Abd El-Aal, R.M.; Mustafa, F.H.A.; Soliman, Y.A.; Hamed, M.A. Hybrid molecules comprising 1,2,4-triazole or diaminothiadiazole Schiff-bases and ionic liquid moieties as potent antibacterial and marine antibiofouling nominees. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2754–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.R.E.; Ali, O.A.A.; Serag, W.M.; Fayad, E.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M.; Gad, E.M. Synthesis, characterization, and biological activity of Co (II) and Zn (II) complexes of imidazoles-based azo-functionalized Schiff bases. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1259, 132726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J., Jr.; Martin, A.E., Jr.; Conrad, C.M. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-ray diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1959, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, U.; Gibson, N. The Scherrer equation versus the ‘Debye-Scherrer equation’. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, N.Y.; Elamin, M.R.; Alqarni, L.S.; Yahya, R.O.; Shahat, A.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M. Sustainable nanocellulose recovery from newspaper waste to fabricate a composite for sensing and scavenging copper and iron in aqueous effluents and mining wastes. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 216, 106423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M.T.; El-Fattah, W.A.; Alluhaybi, A.A.; Subaihi, A.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M.; Shahat, A. Eco-Friendly Nanocellulose-Based Fluorometric Sensor for Ultra-Sensitive Detection and Removal of Mercury Ions from Water. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 39, e70331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibotaru, S.; Ailincai, D.; Andreica, B.-I.; Cheng, X.; Marin, L. TEGylated phenothiazine-imine-chitosan materials as a promising framework for mercury recovery. Gels 2022, 8, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Safty, S.A.; Shenashen, M.A.; Shahat, A. Tailor-made micro-object optical sensor based on mesoporous pellets for visual monitoring and removal of toxic metal ions from aqueous media. Small 2013, 9, 2288–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahat, A.; Hassan, H.M.A.; Azzazy, H.M.E.; Hosni, M.; Awual, M.R. Novel nano-conjugate materials for effective arsenic(V) and phosphate capturing in aqueous media. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 331, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluhaybi, A.A.; Elamin, N.Y.; Elamin, M.R.; Abdalla, S.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M.; Shahat, A.; Radwan, A. Sustainable nanocellulose-Schiff base nanocomposite for dual-mode UV–Vis detection of Fe (III) and Hg (II) ions: Green synthesis from paper tissue waste and computational insights. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 80, 109103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.a.M.; Rameshkumar, P.; Huang, N.M.; Wei, L.S. Visual and spectrophotometric determination of mercury (II) using silver nanoparticles modified with graphene oxide. Microchim. Acta 2016, 183, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; She, S.; Zhang, J.; Bayaguud, A.; Wei, Y. Label-free colorimetric detection of mercury via Hg2+ ions-accelerated structural transformation of nanoscale metal-oxo clusters. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguz, M.; Aydin, D.; Malkondu, S.; Erdemir, S. Specific and low-level detection of Hg2+ and CN− in aqueous solution by a new fluorescent probe: Its real sample applications including cell, soil, water, and food. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 433, 137527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepwat, P.; Saenchoopa, A.; Onnet, W.; Namcharee, P.; Sanmanee, C.; Plaeyao, K.; Kulchat, S.; Kosolwattana, S. The synthesis and study of carboxymethyl cellulose from water hyacinth biomass stabilized silver nanoparticles for a colorimetric detection sensor of Hg (ii) ions. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 41241–41252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, W. Nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots: Facile synthesis and application as a “turn-off” fluorescent probe for detection of Hg2+ ions. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 55, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Feng, M.; Chen, X.; Tang, X. N-dots as a photoluminescent probe for the rapid and selective detection of Hg2+ and Ag+ in aqueous solution. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 2086–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ren, G.; Tang, M.; Chai, F.; Qu, F.; Wang, C.; Su, Z. Fluorescent silicon nanoparticles for sensing Hg2+ and Ag+ as well visualization of latent fingerprints. Dye. Pigment. 2018, 149, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Peng, K.; Lu, Y.; Li, A.; Che, F.; Liu, Y.; Xi, X.; Chu, Q.; Lan, T.; Wei, Y. Synthesis of fluorescent ionic liquid-functionalized silicon nanoparticles with tunable amphiphilicity and selective determination of Hg2+. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 8214–8220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Tong, C. Nitrogen-and sulfur-codoped carbon dots for highly selective and sensitive fluorescent detection of Hg2+ ions and sulfide in environmental water samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2794–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Chu, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y. Fluorescent probe based nitrogen doped carbon quantum dots with solid-state fluorescence for the detection of Hg2+ and Fe3+ in aqueous solution. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, F.; Anbia, M. Nitrogen-rich silicon quantum dots: Facile synthesis and application as a fluorescent ‘on–off–on’ probe for sensitive detection of Hg2+ and cyanide ions. Luminescence 2022, 37, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallali, H.; Yazdandoust, M. Design and Evaluation of a Mercury (II) Optode Based on Immobilization of 1-(2-Pyridylazo)-2-naphthol on a Triacetylcellulose Membrane and Determination in Various Samples. Eurasian J. Anal. Chem. 2008, 3, 284–297. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, A.; Shahat, A. A novel approach for green synthesis of cellulose nanorods as optical sensor support for ultra-detection and recovery of precious metals from electronic wastes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Safty, S.A.; Awual, M.R.; Shenashen, M.A.; Shahat, A. Simultaneous optical detection and extraction of cobalt (II) from lithium ion batteries using nanocollector monoliths. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 176, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhani, E.; Al Zbedy, A.S.; Alqarni, S.A.; Alzahrani, S.O.; Alharbi, A.; Alfi, A.A.; Al-Bonayan, A.M.; Shahat, A. Eco-friendly nanocellulose-based sensor for sensitive and selective detection of mercury and iron ions in water samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2025, 105, 9104–9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.