Abstract

The processing of ginger-processed Pinellia ternata (Zhejiang) has long relied on empirical judgment, lacking objective and real-time monitoring methods. This study introduces an intelligent framework that combines a multi-frequency electronic tongue with chemometric modeling—including principal component analysis–discrimination index (PCA–DI) and wrapper-based support vector machine (SVM) classification—for dynamic process monitoring. Taste-response signals were systematically collected from key processing, water-leaching, and pickling stages. PCA–DI analysis demonstrated clear separability among seven key processing nodes (DI = 93.77%). Notably, samples from days 2 and 3 of water-leaching showed high similarity, suggesting an optimal soaking duration, while a marked transition on pickling day 6 indicated a critical transformation point. The wrapper–SVM models achieved high classification accuracies of 95.51% for key nodes, 100% for water-leaching, and 89.32% for pickling. These findings demonstrate that integrating electronic tongue sensing with machine learning effectively captures dynamic quality variations, offering a robust and objective strategy for the standardization and optimization of traditional medicine processing.

1. Introduction

In recent years, traditional Chinese medicinal materials have gained widespread international recognition due to their demonstrated clinical efficacy and unique cultural value. Pinellia ternata, the dried tuber of a plant from the Araceae family, has been widely used in clinical practice in China [1]. According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2025 edition), it exhibits antitussive, expectorant, antiemetic, and phlegm-alleviating properties [2]. Modern pharmacological studies have also confirmed its roles in anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and gastrointestinal regulation [3]. However, raw P. ternata showed significant toxicity, characterized by intense pungency, tongue numbness, and throat irritation. To mitigate these effects, processed forms have been widely adopted in clinical practice [4].

Ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang), a regionally specific processed product included in the Zhejiang Standards for Chinese Medicinal Material Processing (2015 edition), is widely adopted in Zhejiang Province. Its processing involves water-leaching the raw tubers for 1–2 days until the interior is fully moistened with no dry core remaining, followed by air-drying to a semi-dry state and slicing into thick pieces. These slices are then mixed with alum powder and pickled for 6–10 days until a slight tingling sensation is detected when tasted. Finally, the slices are rinsed, dried, and mixed with ginger juice for final drying. This procedure employs water-leaching, alum pickling, and ginger-juice mixing to achieve detoxification while enhancing efficacy [5,6,7,8].

A critical step in this process—alum marination—relied on the empirical criterion of inducing a “slight tongue-numbing sensation” to determine completion. This method heavily depended on individual sensory evaluation, leading to high subjectivity, poor reproducibility, and a lack of quantifiable standards. Such limitations resulted in batch-to-batch quality inconsistencies, potentially compromising clinical safety and efficacy. Therefore, establishing an objective and accurate quality control method was essential for standardizing the production of ginger-processed Pinellia ternata.

In response to these needs, several research teams have employed instrumental analytical techniques to monitor chemical changes during the processing of P. ternata. Li et al. analyzed nucleoside variations using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and found that processing significantly altered their contents [9]. Yang et al. established characteristic HPLC fingerprints to compare different processed products, revealing distinct compositional patterns among processing methods [10]. Zhang et al. further profiled the chemical constituents before and after ginger processing using HPLC–Q–TOF–MS/MS and demonstrated that ginger processing reduces toxic lysophosphatidylcholine compounds while generating new gingerol derivatives [11]. Collectively, these studies have elucidated the compositional transformation of P. ternata during processing and provided a theoretical basis for the standardization of decoction piece quality. However, such instrumental analyses are time-consuming, technically demanding, and costly, making them unsuitable for rapid or real-time process monitoring.

Considering these limitations, recent advances in artificial intelligence and bionic sensing have facilitated the widespread application of the electronic tongue—a detection tool capable of digitizing and objectively quantifying taste signals—in food quality control [12,13]. This technology has been gradually extended to quality evaluation of traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) [14,15]. Its application was also explored in the processing of P. ternata. Kang et al. [16] integrated the electronic tongue with pattern recognition algorithms and achieved effective classification of various processed products, including ginger-processed and alum-processed P. ternata. Yang et al. [17] combined electronic tongue data with chemometrics and chromatographic fingerprints to establish a chemical quality evaluation system for P. ternata and its processed forms. These studies collectively demonstrated the potential of the electronic tongue for discriminating and evaluating processed TCM products. However, existing research primarily focused on differentiating finished products, while dynamic monitoring of processing procedures within the same specification was rarely reported. Consequently, real-time assessment and precise control of processing remained challenging, limiting broader application in process optimization and quality control.

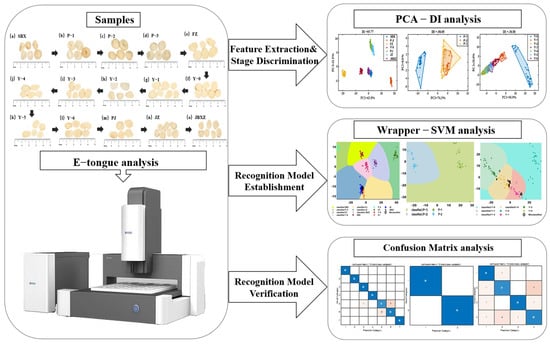

To overcome these limitations in real-time monitoring and precise control, we established an intelligent classification framework by integrating a multi-frequency pulse electronic tongue with a support vector machine (SVM) [18]. Unlike previous studies that focused mainly on discriminating finished products [16,17], the key advancement of this work lies in its ability to capture the dynamic taste evolution within each key processing stage (water-leaching and pickling), thereby enabling precise, objective identification of critical transition points. This intelligent classification framework was specifically applied to dynamically monitor each processing stage in the entire workflow of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang), offering real-time insight into the evolution of taste characteristics. Taste-response data were systematically collected across the key, water-leaching, and pickling processing stages. Principal component analysis (PCA) combined with the discrimination index (DI) was applied to evaluate the separability among these stages. Subsequently, the Wrapper-based feature selection algorithm was employed to identify highly discriminative taste features, upon which SVM-based classification models were constructed for stage recognition and monitoring. The overall experimental workflow is presented in Figure 1. Overall, this work bridges sensory bionics and chemometric modeling for data-driven control of traditional medicine processing, establishing a paradigm for intelligent and standardized control in traditional Chinese medicine processing.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the study protocol for intelligent monitoring and process optimization of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Pinellia ternata was obtained from Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Chinese Herbal Pieces Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). The rhizomes were collected from the authentic production region in Gansu Province, China. All samples were authenticated by Professor Zengxi Guo (Zhejiang Institute for Food and Drug Control). Ginger-processed P. ternata samples were prepared according to the Zhejiang Standards for Chinese Medicinal Material Processing (2015 edition). Processing was conducted in three independent batches.

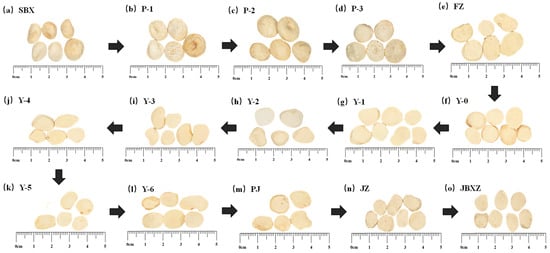

The raw P. ternata (sample code: SBX) totaled 1000 kg, from which samples were collected at different stages. During the water-leaching step, a 1 kg sample was taken on the first day and dried at 60 °C (designated as sample P-1). On the second day, 3 kg was collected; 1 kg was dried and designated as sample P-2, and the remaining 2 kg continued water-leaching until the third day before drying (designated as sample P-3). After two days of leaching, the batch was sliced, mixed with alum, and 1 kg was dried at 60 °C (designated as sample FZ).

In the subsequent pickling stages, 1 kg samples were collected daily from day 0 to day 6, dried at 60 °C, and designated as samples Y-0 to Y-6. After six days of pickling, the material was rinsed with water, and 1 kg was dried as sample PJ.

The batch was then mixed with ginger juice, and 1 kg was collected and dried at 60 °C (designated as sample JZ). The final dried product was designated as sample JBXZ. Samples from all three batches were combined to form a composite sample for electronic tongue analysis.

Detailed information on these processing samples was summarized in Table 1, and the corresponding workflow was illustrated in Figure 2. Ultrapure water was prepared using a Millipore system (Bedford, MA, USA), with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm.

Table 1.

Information on the processing samples of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang).

Figure 2.

Processing workflow of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang).

2.2. Sample Preparation

Raw P. ternata and ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang) samples were ground into homogeneous powder (passed through a 50-mesh sieve). Subsequently, 4 g of each powdered sample was suspended in 100 mL of ultrapure water and extracted by ultrasonication at 25 °C for 60 min (500 W, 40 kHz) to obtain the test solutions. All resulting solutions were stored at 25 °C in the dark before electronic tongue detection.

2.3. Electronic Tongue Detection

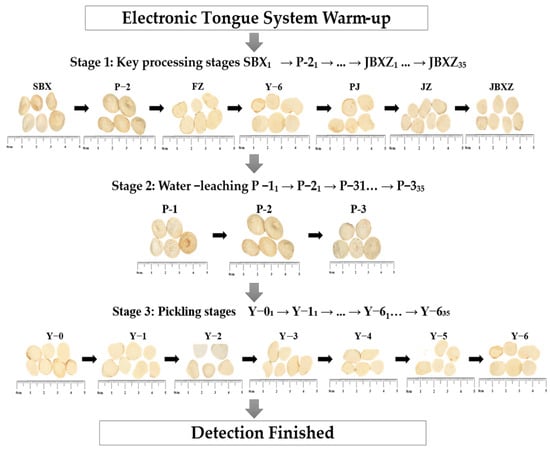

The electronic tongue system, self-developed by our laboratory [19], consisted of six different metallic disk electrodes (platinum, gold, palladium, tungsten, titanium, and silver; diameter 2 mm; purity 99.9%) serving as working electrodes (labeled as S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6), an Ag/AgCl electrode (saturated KCl, diameter 2 mm) as the reference electrode, and a platinum electrode (diameter 2 mm) as the auxiliary electrode for the standard three-electrode system. The six working electrodes and the auxiliary electrode were embedded in a composite material, with the reference electrode positioned nearby. The electrodes were connected to a multi-frequency large-amplitude pulse voltammetry (MLAPV) scanner, which was controlled by a computer. The system applied a pulse waveform ranging from −1.0 V to +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) with a potential step of 0.2 V at discrete frequencies of 1, 10, and 100 Hz. The vertex and inflection currents of the response curve were extracted as characteristic values for subsequent analysis, consistent with previously validated MLAPV-based e-tongue methods [19]. The electronic tongue detection steps were as follows, and the detailed detection workflow is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Electronic tongue detection workflow across three processing stages. The e-tongue was rinsed with ultrapure water between the detection of every two samples.

Step 1. The electronic tongue was preheated with the detection sample for 30 min and then rinsed with ultrapure water.

Step 2. Each sample was analyzed using a cross-test sequence designed to minimize measurement bias:

1. Key processing stages—sample 1 of SBX → sample 1 of P-2 → sample 1 of FZ → sample 1 of Y-6 → sample 1 of PJ → sample 1 of JZ → sample 1 of JBXZ → sample 2 of SBX → sample 2 of P-2 → … → sample 35 of JBXZ.

2. Water-leaching stages—sample 1 of P-1 → sample 1 of P-2 → sample 1 of P-3 → sample 2 of P-1 → sample 2 of P-2 → … → sample 35 of P-3.

3. Pickling stages—sample 1 of Y-0 → sample 1 of Y-1 → … → sample 1 of Y-6 → sample 2 of Y-0 → sample 2 of Y-1 → … → sample 35 of Y-6.

Step 3. Between the detection of two samples, the electronic tongue was rinsed with ultrapure water.

In this study, a predefined cross-test sequence was employed to ensure systematic coverage of all processing stages and to maintain operational manageability, rather than a fully randomized order. This approach was adopted to achieve a balance between methodological rigor and practical efficiency in handling a large number of samples. Crucially, the electronic tongue sensor was thoroughly rinsed with ultrapure water between measurements of every two samples to minimize potential carryover effects and ensure signal independence. Future methodological improvements may involve the implementation of a fully randomized detection sequence to further enhance the robustness of the approach.

To ensure signal stability during MLAPV detection, the electronic tongue was preheated for 30 min before measurement, allowing the baseline current of all electrodes to reach equilibrium. Because the MLAPV system extracts discrete vertex and inflection currents rather than using the entire continuous voltammetric waveform, additional preprocessing procedures such as baseline correction, smoothing, or drift removal were deemed unnecessary. This is because the analysis relies on discrete characteristic points that are inherently robust to baseline fluctuations and high-frequency noise in the raw signal, as previously demonstrated in our laboratory’s studies and in the classical multi-frequency voltammetric e-tongue framework [12,19,20]. After feature extraction, all features were standardized using Z-score normalization, which served as the primary preprocessing step before chemometric modeling.

2.4. PCA–DI Analysis

For each sample, the six metallic electrodes generated pulse-response curves under three independent frequencies (1, 10, and 100 Hz). From each frequency segment, 40 vertex and inflection points were extracted, yielding a total of 720 raw features per sample. These features were concatenated in a fixed order (sensor-wise followed by frequency-wise) to construct a unified high-dimensional multi-frequency feature vector. This constitutes a feature-level fusion strategy that preserves complementary electrochemical information across frequencies prior to dimensionality reduction via PCA, which subsequently extracts the most discriminative integrated features for downstream analysis.

After cross-test detection of samples from the key processing, water-leaching, and pickling stages of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang) using the electronic tongue, feature values were analyzed using a previously established PCA–DI method developed by our laboratory [21] to evaluate the discriminative ability among samples at different processing stages. In this method, the DI quantitatively reflects class separability in PCA space, with higher values indicating stronger discrimination. The PCA–DI analysis procedure was as follows:

Step 1: PCA was performed on all feature values obtained from the six electrode combinations.

Step 2: Based on the PCA results, the discrimination index (DI) was calculated using the following equation:

where Si represents the area occupied by each class in the PCA plot, and S0 represents the total area encompassing all classes (the overall convex hull) in the PCA plot. Higher DI values indicated stronger discriminative ability among the samples, quantitatively reflecting their separability in PCA space. Note that negative DI values indicate substantial overlap among classes, whereas positive values reflect clear separability.

DI = (1 − Σ(Si/S0)) × 100%

2.5. Wrapper-Based Feature Selection

To identify the most discriminative features for subsequent classification, a wrapper-based feature selection strategy was implemented. This procedure employed the Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) algorithm [22], which incrementally constructs an optimal feature subset. Candidate subsets were evaluated using the misclassification error (MCE) criterion [23], defined as the proportion of incorrectly classified samples. The generalization performance of each subset was robustly estimated through 10-fold cross-validation (10-fold CV) following established statistical learning principles [24]. The detailed workflow was as follows:

Step 1: Raw electronic tongue features were standardized and transformed into orthogonal principal components via PCA to form the initial feature pool for selection. These PCA-derived components represent integrated taste features that fuse information from all electrodes and frequencies, forming a compact and noise-reduced feature space for subsequent wrapper-based feature selection.

Step 2: The SFS algorithm [22], operating as a wrapper-type method, was applied to the PCA-derived feature pool. At each iteration, a candidate feature was added to the subset, and the resulting subset was evaluated using a SVM classifier. Subset quality was quantified by the MCE, with MCE estimates obtained through 10-fold CV to ensure reliable assessment of predictive performance. The iterative search terminated when further reductions in MCE were no longer observed. In this procedure, a linear-kernel SVM with Z-score standardized inputs was used as the base classifier, and the mean 10-fold cross-validation misclassification error served as the feature selection criterion.

Step 3: After the SFS procedure converged, the indices and number of selected principal component features were recorded.

Step 4: The final SVM classifier was trained using the optimal feature subset obtained in Step 3. Its generalization capability was rigorously evaluated again using 10-fold CV to provide an unbiased estimation of classification accuracy.

2.6. SVM Modeling

To effectively classify samples from different processing stages of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang), the SVM algorithm was employed to construct discriminative models tailored to the requirements of each processing stage. Multiclass and binary SVM models were constructed to characterize the key processing, water-leaching, and pickling stages, respectively. All models were trained using the optimal feature subsets selected through the wrapper-based feature selection method. This modeling framework enabled intelligent stage discrimination and dynamic quality monitoring throughout the entire processing workflow. All SVM models were implemented with a linear kernel and standardized features; multiclass problems were handled by an error-correcting output codes (one-vs-all) scheme, and model performance was consistently evaluated by 10-fold cross-validation.

3. Results and Discussion

The results presented in this study demonstrate the successful application of an intelligent framework that integrates a multi-frequency pulse electronic tongue with chemometric modeling for dynamic monitoring of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang). This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods. The key novelty of this work lies in its ability to translate subtle, time-dependent variations in taste profiles during traditional processing into objective, quantifiable data. This method effectively addresses the critical limitation of subjective sensory evaluation, which has hindered standardization in medicinal material processing. Furthermore, the use of multi-frequency signals, as opposed to conventional single-frequency analysis, enables a more comprehensive capture of the complex taste profile by probing different electrochemical properties, thereby enhancing model robustness and discriminative power.

3.1. Feature Extraction and PCA–DI Analysis

To objectively evaluate the discriminative capability of the electronic tongue during processing of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang), the PCA–DI method was applied to the response data obtained from the key processing, water-leaching, and pickling stages. Each working electrode of the electronic tongue provided 40 feature values at each frequency. With six electrodes operating at three frequencies (1, 10, and 100 Hz), a total of 720 features were extracted, sequentially labeled from Feature 1 to Feature 720, forming the dataset for subsequent analysis.

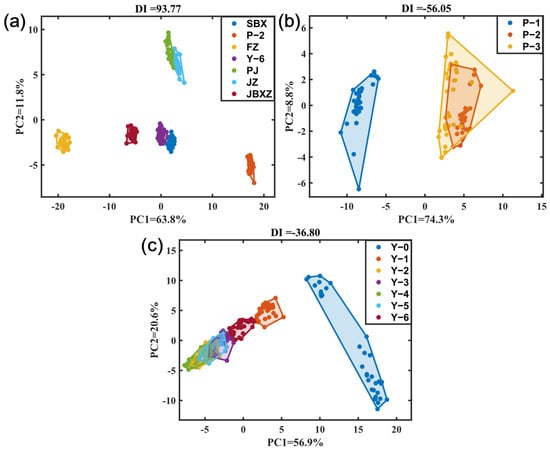

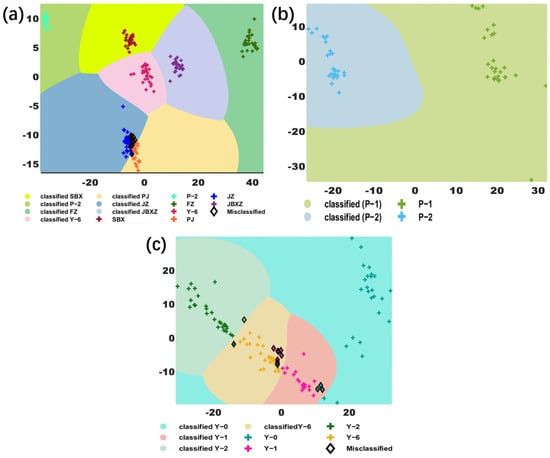

For the seven key processing stages (SBX, P-2, FZ, Y-6, PJ, JZ, and JBXZ), PCA–DI analysis yielded a discrimination index (DI) of 93.77%, indicating excellent separability. As shown in Figure 4a, the samples formed distinct, non-overlapping clusters in the PCA score plot, validating the efficacy of the electronic tongue in discriminating key stages throughout the processing workflow.

Figure 4.

PCA results of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang) at different processing stages: (a) key processing stages; (b) water-leaching stages; (c) pickling stages.

This finding aligns with reports of substantial chemical transformations during processing. Li et al. [9] documented significant alterations in nucleoside components between raw and processed P. ternata, while Zhang et al. [11] used HPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS to reveal distinct compositional profiles before and after ginger processing. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the electronic tongue, as a bioinspired taste-sensing system, sensitively captures taste signal variations induced by these chemical changes, thereby enabling reliable discrimination of processing nodes and providing a solid foundation for developing high-accuracy recognition models.

The PCA results for the water-leaching stages are presented in Figure 4b. Samples from day 1 of water-leaching (P-1) were clearly separated from those from day 2 (P-2) and 3 (P-3), whereas samples from P-2 and P-3 exhibited substantial overlap. These results indicate that major taste variations occur within the first two days of water-leaching, with no further significant changes upon extending the process to the third day. This finding suggests that limiting the water-leaching duration to two days may balance processing efficacy with production efficiency, while providing objective, quantitative evidence supporting the traditional practice of “leaching until no dry core remains.” Therefore, designating a two-day duration as the potential optimal period for the water-leaching process appears reasonable and warrants further validation in subsequent studies. This observation is consistent with previous reports showing that toxic constituents in P. ternata markedly decline during the first day of processing, with slower changes thereafter [25]. Collectively, these findings confirm that the early phase of processing constitutes a critical window for toxicity reduction and quality optimization.

The PCA results for the pickling stages are presented in Figure 4c. Samples from day 0 and 1 were relatively dispersed, whereas samples from day 2–5 exhibited substantial overlap and formed a compact cluster, indicating a relatively stable period. Samples from day 6 were distinctly separated, suggesting a critical transformation at this stage of processing. This finding is consistent with previous reports indicating that Pinellia ternata treated with lime water and licorice juice exhibits the most pronounced reduction in toxic components during the early soaking stages, with diminishing returns upon prolonged processing [26]. This pattern is consistent with the dynamics observed during days 0–5 of pickling in this study. In contrast, the marked separation on day 6 could result from further constituent degradation or transformation induced by prolonged pickling—a hypothesis requiring experimental verification. Therefore, day 6 of pickling can be identified as a critical process-monitoring point to determine whether the processing has reached the expected transformation or requires procedural adjustment.

Taken together, these findings establish that the electronic tongue technique coupled with PCA–DI analysis not only enables objective differentiation of key processing stages and sub-stages such as water-leaching and pickling throughout the processing of Pinellia ternata (Zhejiang), but also pinpoints critical process transition points—specifically, water-leaching day 2 and pickling day 6—thereby furnishing a scientific basis for the refined control and optimization of the processing protocol.

3.2. Construction of Wrapper–SVM-Based Processing Stage Recognition Models

After verifying the capability of the electronic tongue to discriminate among the processing stages of ginger-processed Pinellia ternata (Zhejiang), an intelligent recognition model based on the Wrapper–SVM algorithm was established (Figure 5) to enable automated discrimination of key processing nodes and the water-leaching and pickling stages. The modeling process was designed to account for the discriminability among different processing stages, as detailed below.

Figure 5.

Recognition results of ginger-processed P. ternata (Zhejiang) at different processing stages: (a) key processing stages; (b) water-leaching stages; (c) pickling stages.

Key Processing Stages Recognition Model: PCA–DI analysis revealed that the seven key processing nodes (SBX, P-2, FZ, Y-6, PJ, JZ, and JBXZ) exhibited clear separation in the PCA space, demonstrating good discriminability. Consequently, all nodes were incorporated into the stage-recognition model. After SFS-based feature selection, PC1, PC2, and PC3 were ultimately selected as the optimal principal components and used to build the final multi-class SVM model. As shown in Figure 5a, the constructed SVM model achieved an identification accuracy of 95.51%, indicating that the model effectively distinguished the seven key processing nodes and enabled accurate recognition of the critical processing stages throughout the entire manufacturing process.

Water-Leaching Stages Recognition Model: Given the high similarity in sensory profiles between samples from days 2 and 3 of water-leaching, the recognition objective was simplified to a binary classification between day 1 and day 2 samples, thereby enhancing the model’s discriminatory power and practical applicability. After feature selection, PC1 was identified as the optimal feature and subsequently used to construct a binary SVM model. As shown in Figure 5b, the model achieved 100% accuracy, demonstrating complete discrimination between P-1 and P-2 samples and thereby establishing a reliable basis for dynamic monitoring of the water-leaching process.

Pickling Stages Recognition Model: PCA revealed that samples from day 2–5 of pickling formed a tight and stable cluster in the PCA space, whereas those from days 0–1 were more dispersed, suggesting significant early-stage transformations. Accordingly, four representative time points were selected for modeling: day 0 (the starting point of pickling), day 1 (the early-change stage), day 2 (the stable phase), and day 6 (the critical transformation point). Following SFS-based feature selection, PC1, PC2, PC3, and PC13 were selected as the optimal feature set and used to construct a multiclass SVM model. As displayed in Figure 5c, the model discriminated between samples from Y-0, Y-1, Y-2, and Y-6 with an accuracy of 89.32%.

3.3. Validation of Wrapper–SVM–Based Processing Stage Recognition Models

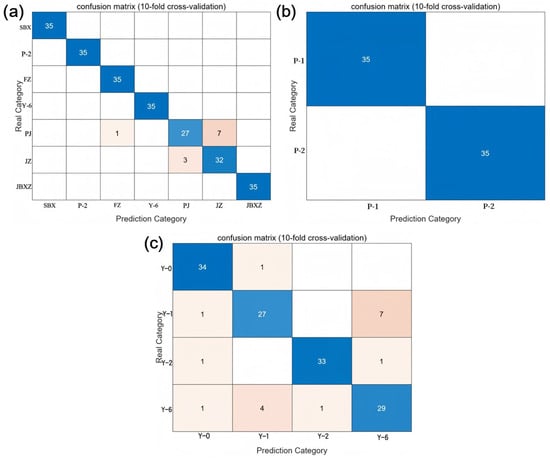

To systematically evaluate the generalization capability and reliability of the Wrapper–SVM recognition models, 10-fold cross-validation was employed. The dataset was randomly divided into ten equally sized folds; in each iteration, nine folds were used for training and the remaining fold for testing, and the mean classification accuracy across all folds was taken as the primary performance metric. Crucially, the confusion matrices in Figure 6 were generated from the 10-fold cross-validated prediction results (k-fold predictions), rather than from the training data, thereby providing an unbiased assessment of classification reliability across processing stages. The detailed performance metrics for each model are summarized in Table 2, and a detailed analysis follows.

Figure 6.

Classification reliability demonstrated by 10-fold cross-validated confusion matrices: (a) key processing stages; (b) water-leaching stages; (c) pickling stages.

Table 2.

Performance of Wrapper–SVM recognition models at different processing stages.

The key processing stages recognition model achieved a 10-fold cross-validation accuracy of 94.42%, which was in close agreement with the high discrimination index (DI = 93.77) obtained from the PCA–DI analysis. This consistency demonstrates that the electronic tongue combined with machine learning enables the reliable identification of critical nodes throughout the entire processing workflow. According to the confusion matrix (Figure 6a), some mutual misclassification occurred between the “post-washing” (PJ) and “ginger-mixing” (JZ) nodes, suggesting that this likely stems from their close procedural connection and the similarity of their solution taste profiles. Despite this observation, the remaining key nodes (e.g., SBX, P-2, and FZ) were clearly distinguished, demonstrating robust recognition of most key processing nodes by the model.

The water-leaching stages model performed exceptionally well, as its confusion matrix (Figure 6b) showed that samples from P-1 and P-2 were classified with perfect accuracy. Furthermore, the model achieved 100% accuracy in both training and cross-validation, demonstrating complete discrimination between the two sample types. Together, these results demonstrate the high reliability of the electronic tongue technology in dynamically monitoring the water-leaching process and provide an objective basis for optimizing the leaching duration.

For the pickling stages, the recognition model revealed the complex dynamics of this process. The four-class SVM model constructed using Y-0, Y-1, Y-2, and Y-6 achieved an average 10-fold cross-validation accuracy of 87.86%. The confusion matrix (Figure 6c) revealed pronounced misclassification between Y-1 and Y-2 samples, with additional cross-misclassifications observed between Y-0 and Y-1 as well as between Y-2 and Y-6. This misclassification pattern was highly consistent with the continuity of sample distribution observed in the PCA, which reflects the gradual transition of taste characteristics during the pickling process.

Overall analysis revealed that although partial overlap among processing nodes was caused by feature continuity, the stage recognition models still maintained high accuracy and robustness. This study systematically validated the feasibility and consistency of combining electronic tongue technology with the Wrapper–SVM approach for dynamic monitoring of the processing of Pinellia ternata (Zhejiang), thereby providing an objective and quantitative technical basis for process evaluation that has traditionally relied on sensory experience.

3.4. Phytochemical Basis of Taste Transitions During Ginger Processing

The dynamic taste evolution captured by the electronic tongue across different processing stages can be interpreted in the context of well-documented phytochemical transformations occurring during the processing of P. ternata. Raw P. ternata contains several recognized irritant components, including needle-shaped calcium oxalate raphides and water-soluble lectins, which constitute the primary chemical basis of its characteristic tingling and numbing sensations [27]. During the first two days of water-leaching, these water-soluble and diffusible irritants are substantially reduced in the tuber matrix, which explains the observed convergence of taste profiles between day-2 and day-3 samples, as shown in the PCA score plot (Figure 4b). Previous studies have demonstrated that soluble oxalates, free organic acids, and low–molecular-weight irritant components markedly decrease after 24–48 h of soaking, aligning with the trends observed in this work [25].

During the alum-pickling stage, the addition of alum induces ion-exchange reactions and protein–metal interactions that alter the microstructure of toxic components. Alum has been shown to corrode or partially dissolve calcium oxalate raphides and to reduce the content or activity of toxic lectins, thereby attenuating irritancy and contributing to detoxification [5]. These alum-associated transformations correspond closely to the distinct taste shift detected on pickling day 6 in both our PCA (Figure 4c) and SVM classification results (Figure 6c), suggesting that this time point represents a critical chemical transition during processing.

Ginger further contributes to both detoxification and flavor modulation. Heating or treatment with dried ginger extract significantly decreases the amount of lectin bound to raphides, with oxalic, tartaric, malic, and citric acids identified as key active contributors responsible for this effect [8]. Additionally, ginger-derived constituents such as gingerols and shogaols have been reported to mitigate lectin-induced irritation and to impart mild pungency to processed P. ternata, consistent with the taste characteristics observed in this study.

Taken together, the leaching of water-soluble irritants, alum-induced modification of raphides and lectins, and the detoxifying and flavor-modulating effects of ginger jointly provide a scientifically grounded phytochemical rationale that supports the dynamic taste evolution detected by the multi-frequency electronic tongue throughout the processing workflow.

4. Conclusions

This study develops an intelligent approach integrating electronic tongue technology with the Wrapper–SVM algorithm for dynamic monitoring and recognition of processing stages in ginger-processed Pinellia ternata (Zhejiang). Based on the systematic analysis of samples from the key processing, water-leaching, and pickling stages—integrated with PCA–DI analysis and feature selection strategies—the developed multi-stage recognition model demonstrated high performance in 10-fold cross-validation. Consequently, the results confirmed that the electronic tongue effectively captured the characteristic taste profile evolution throughout the processing, particularly enabling clear discrimination of temporal variations in the water-leaching stages and pinpointing the critical transformation point on day 6 of pickling.

The Wrapper–SVM model exhibited high recognition accuracy across all processing stages (exceeding 85%), significantly outperforming traditional sensory-based empirical judgments. In contrast to conventional chemical analytical techniques such as HPLC and GC-MS, the electronic tongue coupled with machine learning offers the advantages of being nondestructive, rapid, and highly reproducible, thereby making it better suited for real-time monitoring and dynamic evaluation during processing. Overall, this study provides not only an objective and efficient quantitative tool for the standardized production of ginger-processed Pinellia ternata (Zhejiang) but also a viable technological framework for advancing the application of process analytical technology (PAT) in traditional Chinese medicine processing.

Despite its promising findings, this study has certain limitations. First, the pickling process was monitored for only six days; thus, future studies should extend the observation period to systematically elucidate its dynamic evolution patterns. Second, although the electronic tongue effectively discriminated between different processing stages, its taste-response signals were not directly correlated with changes in chemical composition. Future research should integrate electronic tongue data with metabolomic or chromatographic fingerprinting profiles to bridge the gap between process monitoring and mechanistic understanding. Moreover, the dataset size and batch sources were limited in this study, and although environmental conditions were controlled, minor temperature or humidity fluctuations may still influence electrochemical responses. Future studies incorporating multi-batch validation and environmental compensation will further enhance the robustness and practical applicability of the proposed system. This synergy is anticipated to be pivotal in establishing a smart, data-driven quality control framework within traditional Chinese medicine processing.

Based on the findings of this study, a significant future direction involves correlating the objective taste-response signals of the electronic tongue with systematic sensory analysis. Future work could focus on establishing a trained sensory panel to perform quantitative evaluations (e.g., intensity of tongue-numbing sensation, pungency) on samples from key processing stages, translating these subjective perceptions into reliable numerical data. Through correlation analysis and multimodal data fusion between the e-tongue data and the panel’s quantified judgments, a deeper understanding of the relationship between instrumental measurements and human perception can be achieved. This approach not only validates the reliability of the electronic tongue in simulating human taste but also paves the way for an innovative quality control solution that integrates scientific rigor with practical applicability in traditional medicine processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F., Y.M., and B.C.; methodology, J.G., L.Z., and S.T.; software, J.G., S.T., and S.C.; validation, J.G., Y.W., L.W., and S.C.; formal analysis, J.G., L.Z., and S.C.; investigation, J.G., L.Z., and Y.L.; resources, B.C., C.F., and C.Z.; data curation, J.G. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, C.F., Y.M., B.C., and S.T.; visualization, J.G.; supervision, C.F., Y.M., and B.C.; project administration, C.F. and B.C.; funding acquisition, C.F., Y.M., and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang, grant number 2025C01133; the Zhejiang Provincial Drug Regulatory Science and Technology Plan Projects, grant number 2025002; and the Hangzhou Natural Science Foundation, grant number 2024SZRYBC200001. The APC was funded by the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (grant number 2025C01133).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhejiang Traditional Chinese Medicine Decoction Pieces Co., Ltd. for providing processing samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| DI | Discrimination Index |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| Q-TOF-MS/MS | Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| TCMs | Traditional Chinese Medicines |

| PAT | Process Analytical Technology |

References

- Mao, R.; He, Z. Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit: A review of its germplasm resources, genetic diversity, and active components. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; China Medical Science Press: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, T.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhao, C. A review of the research progress on Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit.: Botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and quality control. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, T. Current status of research on toxic components and processing mechanism of Pinellia ternata. Shanghai J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2007, 2, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.B.; Wu, H. Effect of lime-water processing on lectin protein toxicity components in Pinellia ternata. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi (China J. Chin. Mater. Med.) 2023, 48, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.P. Study on the Detoxification Mechanism of Gingerol Components in Zingiber officinale on the Toxicity of Pinellia ternata and Typhonium giganteum. Ph.D. Thesis, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Yang, F.; Hu, J.; Cheng, H.; Shen, C.; Wang, S. Pinellia genus: A systematic review of active ingredients, pharmacological effects and action mechanism, toxicological evaluation, and multi-omics application. Gene 2023, 870, 147426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Nose, I.; Terasaka, K.; Fueki, T.; Makino, T. Heating or ginger extract reduces the content of Pinellia ternata lectin in the raphides of Pinellia tuber. J. Nat. Med. 2023, 77, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Q.; Guo, C.H.; Jin, W.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Liu, J.; Song, P.S.; Ni, L. Study on changes of multiple nucleoside components in Pinellia ternata before and after processing. Zhong Yao Cai (Chin. Med. Mater.) 2023, 46, 1664–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.Y.; Li, M.; Shi, J.; Xia, D.M.; Li, X.X.; Yang, X.Y. Systematic study on HPLC fingerprint of Pinellia ternata and its processed products. Zhong Cao Yao (Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs) 2014, 45, 652–658. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.M.; Zhang, J.H.; Fan, B.; Yuan, F.M.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.F.; Peng, J.; Liang, X.W. Component analysis of Pinellia ternata before and after ginger processing based on HPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS technology. Shi Zhen Guo Yi Guo Yao (J. Tradit. Chin. Med.) 2024, 35, 1899–1903. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.Z.; Cheng, S.W.; Shi, B.L.; Zhao, L.; Tian, S.Y.; Wang, H.Y. An optimized detection method for Chinese red Huajiao geographical origin determination based on electronic tongue and ensemble recognition algorithm. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.Z.; Li, N.; Shi, B.L.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, S.W.; Tian, S.Y.; Wang, H.Y. Geographical origin determination of red Huajiao in China using the electronic nose combined with ensemble recognition algorithm. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 4922–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.J.; Luo, M.; Fei, X.M.; Qiu, R.L.; Wang, M.; Gan, Y.F.; Qian, X.D.; Zhang, D.G.; Gu, W. Electronic senses and UPLC-Q-TOF/MS combined with chemometrics analyses of Cynanchum species (Baishouwu). Phytochem. Anal. 2025, 36, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yang, S.L.; Peng, W.; Liu, Y.J.; Xie, D.S.; Li, X.Y.; Wu, C.J. A novel method for the discrimination of Semen arecae and its processed products using computer vision, electronic nose, and electronic tongue. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 753942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.L.; Wang, J.W.; Chen, X.D.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, D.Q.; Li, Z.Y.; Li, J.; Jia, X.Z.; Qu, L.Y.; Sun, D.M.; et al. An effective strategy for exploring the taste markers in alum-processed Pinellia ternata tuber based on analysis of substance and taste by LC–MS and electronic tongue. Phytomedicine 2025, 139, 156509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H. Study on the Chemical Quality of Pinellia ternata and Its Processed Products Based on Chemometrics Combined with Chromatographic Fingerprinting. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaiarasi, G.; Maheswari, S. Deep proximal support vector machine classifiers for hyperspectral image classification. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 13391–13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.Y.; Xiao, X.; Deng, S.P. Sinusoidal envelope voltammetry as a new readout technique for electronic tongues. Microchim. Acta 2012, 178, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.-Y.; Deng, S.-P.; Chen, Z.-X. Multifrequency large amplitude pulse voltammetry: A novel electrochemical method for electronic tongue. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 123, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gu, J.H.; Zhang, R.; Mao, Y.Z.; Tian, S.Y. Freshness evaluation of three kinds of meats based on the electronic nose. Sensors 2019, 19, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, 45, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlot, S.; Celisse, A. A survey of cross-validation procedures for model selection. Stat. Surv. 2010, 4, 40–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bian, X.; Dong, P.; Zhang, L.; Gao, C.; Zeng, H.; Li, N.; Wu, J.L. Food processing drives toxic lectin reduction and bioactive peptide enhancement in Pinellia ternata. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Yu, H.L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.B.; Wang, W. Effect of Pinelliae Rhizoma processed with lime and licorice on toxic lectin protein. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi (China J. Chin. Mater. Med.) 2020, 45, 2546–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, N.; Jiang, E.C.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.L.; Tan, L.; Chen, R.; Wu, C.; Huang, Q. A review of traditional and current processing methods used to decrease the toxicity of the rhizome of Pinellia ternata in traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 299, 115696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).