Abstract

Black crust and spalling are common deterioration phenomena affecting marble relics, yet their correlation remains inadequately understood. Hyperspectral imaging, reflectance spectroscopy, portable X-ray Fluorescence (p-XRF), infrared thermography, Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), and microbiological analysis was employed to connect these two types of deterioration on the Danbi stone carving of the Confucian Temple in Beijing. Spectral and thermal analyses reveal that black crust significantly reduces reflectance and increase solar absorption by 27%, resulting in thermal stress. p-XRF and SEM-EDS analyses indicated that black crust is enriched in Fe, Ti, Zn, Pb, As and clay minerals, while spalling areas display increase Ca, reflecting substrate exposure. Microscopy reveals microcracks at the layer–substrate interface. Microbiological analyses identify Cladosporium anthropophilum and Alternaria alternata as contributors to surface-darkening. These multi-scale datasets collectively demonstrate that alterations in surface chemistry and bio-mediated darkening promoting the formation of black crusts, which subsequently induce marble spalling due to solar absorption and thermal stress. These findings clarify the coupled physical–chemical–biological pathways through which black crust accelerates stone spalling.

1. Introduction

Marble stone relics represent the achievements of art, culture, and architecture of the past. Currently, various types of deterioration phenomenon have appeared on the surfaces of marble stone relics, particularly black crust and spalling. Researchers have investigated extensively.

Regarding the formation mechanism of black crust, researchers assert that the contributing factors to the formation of black crust include physical, chemical, and biological processes [1,2,3]. Atmospheric pollution and the deposition of carbonaceous particles are primary physical factors. Saiz-Jimenez et al. [4] suggested that soot and carbon particles generated from the burning of fossil fuel are the primary contributors to the blackening of marble buildings. Scanning electron microscopy and thermal pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry can determine whether the black pollutants are microbial melanins or carbon deposits. Wang et al. [5] studied the formation mechanism of black pollutants using p-XRF, SEM-EDS, Raman, X-ray diffraction (XRD), inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS) on marble stone relics from the Beijing area. The results showed that black pollutants mainly consist of gypsum and carbon particles. Vehicle exhaust, coal combustion, biomass burning and incense burning are predominant factors. Macchia et al. [6] used a marble bust of Queen Margherita di Savoia from the collection of the U.S. Embassy in Rome as their subject. Through multispectral imaging, spectrophotometry, Raman spectroscopy, and reflectance spectroscopy, they confirmed that the main source of discoloration was particulate matter deposition within marble porosity rather than intrinsic weathering or mineralogical alteration.

Gypsification is fundamentally significant from a chemical perspective [7]. Frank-Kamenetskaya et al. [8] conducted comprehensive investigations of marble monuments in St. Petersburg, Russia, and found that sulfation is the primary mechanism responsible for stone degradation. The development of black crusts is collaboratively influenced by atmospheric pollutants, rock properties, and microbial mechanisms.

Microbial colonization biologically promotes darkening via melanin and acid generation [9]. Dakal et al. [10] noted that sulfur-oxidizing and nitrifying bacteria convert atmospheric pollutants (SO2, NO2) into sulfuric acid and nitric acid, which dissolve marble to form gypsum and produce black crusts. Berti et al. [11] investigated the formation mechanism of black pollutants using white marble from Florence Cathedral as their subject. Through eight weeks of cultivation, they isolated 24 strains from different black areas. Knufia and Lithohypha were the predominant groupings and may be the primary contributors to the formation of black crust.

In terms of spalling phenomena, researchers assert that temperature recycling significantly influences spalling phenomena [12,13]. Malaga-Starzec et al. [14] found, through heat treatment experiments, that temperatures ranging from 40 °C to 50 °C can induce crystal spalling in marble. Calcite marble is more sensitive to temperature compared to dolomite marble, with thermal expansion being the principal mechanism responsible for the formation of microcracks at mineral grain boundaries. Malaga-Starzec K et al. [15] used fluorescence microscopy, nitrogen adsorption, capillary water absorption, ultrasonic velocity measurements, and thermal expansion testing to discover that 50 cycles between −15 °C (12 h) and +80 °C (6 h) would cause marble crystal particles to spalling off, and calcite marble would produce higher residual expansion due to crystal anisotropy. Marini Paola et al. [16] studied the synergistic mechanism of temperature and water on marble through natural exposure experiments and artificial accelerated aging experiments. They found that bowing is accelerated in exposed orientations and linked to higher water absorption, reduced UPV, and microcracking, confirming it as a progressive weathering mechanism that requires systematic monitoring.

Accelerated aging tests highlight the influence of petrographic and microstructural parameters [17,18,19,20,21]. Eppes and Griffing reported the phenomenon of grain spalling of coarse-grained marble in the San Bernardino Mountains of California, USA, under natural environmental conditions. Evidence from microstructural analyses and long-term temperature monitoring indicates that grain boundary detachment occurs within the upper few centimeters of outcrops, driven by solar heating and cooling cycles, confirming that marble is highly susceptible to thermal stress-induced physical weathering [22]. Sassoni Enrico et al. [23] studied the effect of porosity on marble degradation through simulated aging tests. The results showed that the initial porosity significantly regulates the degree of heating degradation. Low-porosity stone produces significant grain boundary microcracks, while high-porosity stone absorb thermal deformation stress within original pores, resulting in reduced damage.

Thermal comparative experiments on different marbles confirm these mechanisms [24,25]. Zhang Z et al. [26] investigated the thermal degradation of Beijing dolomitic marbles subjected to 1000 heating–cooling cycles (−20 °C to 60 °C), simulating seasonal fluctuations. Both Qingbaishi and Hanbaiyu exhibited progressive weight loss and mechanical weakening, with Hanbaiyu experiencing more severe degradation owing to its higher quartz content and greater thermal expansion anisotropy. Vagnon F et al. simulated the interaction of thermal and chemical weathering on Carrara marble, revealing that thermal cycling resulted in an exponential decline in physical and mechanical properties due to microcracks. Furthermore, the addition of sulfuric acid solution at 90 °C significantly accelerated deterioration, highlighting the strong synergy between temperature and pollutants [27].

The characterization techniques primary focus non-destructive and minimally invasive methods that provide in situ diagnosis while preserving the integrity of heritage materials [28,29]. Ultrasonic methods have been widely applied to evaluate marble degradation, Mahmutoğlu Yılmaz et al. [30] proposed using ultrasonic pulse velocity to assess the weathering degree of Turkish Mula marble. Tests on thermally and freeze–thaw aged Muğla marble showed that P-wave velocity correlates well with porosity, capillary absorption, and strength loss, enabling effective assessment of deterioration in coarse-grained marbles. Suzuki Amelia et al. [31] studied the hyperspectral response of gypsum formation on marble surfaces. The results showed that the gypsum layer exhibited distinct absorption in the 1630–2500 nm range, notably at 1944 nm and 2220 nm, which could be distinguished from the calcite spectral peaks. Korkanç Mustafa et al. [32] employed non-destructive testing methods to analyze the distribution of sulfate crusts on the marble of the Karatay Madrasa in Turkey. A p-XRF was employed to map sulfur element contour lines and integrated with infrared thermal imaging technology to reveal the spatial differentiation patterns of the crust.

Minimally invasive methods remain essential for analyzing crust composition and identifying pollutant sources. Yi Yu et al. [33] investigated a calcareous stone tomb in Xianling, China, and found through SEM-EDS and XRF analysis that the main components of black stains on the surface were carbonaceous particles, metallic elements, and sulfur. PM2.5, PM10, and O3 have been recognized as the main threats, showing pronounced seasonal fluctuations, multiscale variability, and complex pollutant interactions. Comite et al. [34] used XRD, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM), SEM-EDX, LA-ICP-MS, and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to study the black crust on the facade of the Monza Cathedral in Italy. The analysis of the black crust on marble surfaces from different periods found that the older black crust contained higher concentrations of calcium oxalate, quartz, and heavy metals. The crust’s composition was highly influenced by vehicular emissions, industrial processes, and biological activities, while its layered structure corresponded to its age and geographical location. Santo et al. [35] found that the blackening of marble in Florence Cathedral was mainly caused by microbial growth. Melanin released by Cladosporium and Alternaria considerably darkened the marble.

Based on the above research findings, it can be inferred that black crust and spalling are not isolated phenomena in the deterioration of marble artifacts, but are closely coupled through temperature, a key physical factor. Currently, there is a lack of in situ, multi-scale, and multi-parameter methods to reveal the spatiotemporal associations and synergistic mechanisms between black crust and spalling. A Danbi stone carvings currently exists in front of the Dacheng Gate of the Confucian Temple and Imperial College Museum. Over nearly 400 years, it has been subjected to the coupled effects of environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, rainfall, and biological activity, resulting in the appearance of black crust and spalling damage on its surface, making it an excellent research subject. Therefore, this study aims to utilize non-destructive and minimally invasive methods to elucidate the physical-chemical-biological coupling mechanisms by which black crust exacerbates spalling damage, providing scientific basis for precise diagnosis, risk prediction, and protective strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Danbi Stone Carving

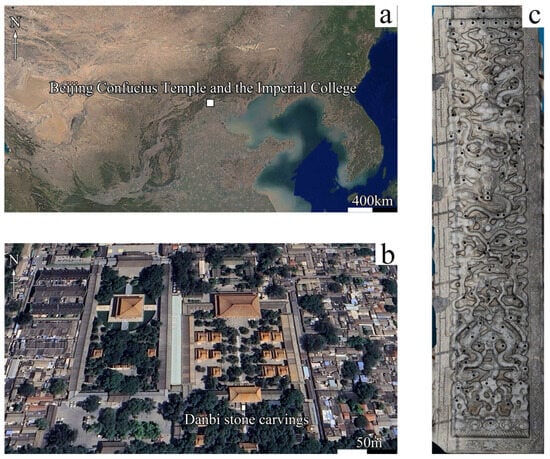

The Danbi stone carvings situated in front of the Dacheng Gate at the Confucian Temple and Imperial College Museum, located in the northeast of Beijing, China, as depicted in Figure 1a. The location is approximately 3.5 km from the Forbidden City, with a central position of 116°41′ east longitude and 39°94′ north latitude. The Danbi stone carves carvings are inlaid at the central steps of the gate (Figure 1b), reaching 6 m in length and 1.5 m in width. It is sculpted in marble with low relief, showcasing a coiling five-clawed dragon at the center, surrounded by grass, cloud and mountains. The proposed measurement and sampling positions selected for this study are marked in Figure 1c.

Figure 1.

General overview map: (a) Position of the Confucian Temple and Imperial College Museum. (b) Distribution of the Danbi stone carvings. (c) Location of the testing points.

2.1.2. Simulated Sample

The simulated samples were obtained from a quarry near Fangshan, Beijing, with lithology that matches the documents for the Danbi. Two types of stone were selected, one with a white surface and another with a black surface. In order to monitor the vertical thermal gradient, holes of different depths were drilled into the sample.

2.2. Analysis Method

2.2.1. P-XRF

In situ elemental characterization was performed using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Niton XL3t 800, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The instrument was equipped with a silver anode X-ray tube and operated under mineral model, with each acquisition lasting 60 s. To reduce environmental and instrumental variability, all measurements were completed within a single day.

2.2.2. Reflectance Spectral Measurement

Reflectance spectra were obtained using a TerraSpec 4 Hi-Res mineral spectrometer (Malvern Panalytical, Boulder, CO, USA), encompassing the spectral range from 350 to 2500 nm. The system offers high spectral resolution in Visible and near-infrared spectral region (VNIR) and Short-wave infrared spectral region (SWIR), enabling detailed identification of optic features. A 10 mm measurement point was adopted, and each spectrum was obtained within a few seconds. Illumination was supplied by a halogen light source, and reflectance calibration was conducted using a standard white reference panel before measurements.

2.2.3. Hyperspectral (HSI)

Hyperspectral imaging was conducted using a portable SPECIM IQ camera (SPECIM, Oulu, Finland), which combines an image spectrograph with a Complementary Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor sensor. The system captures reflectance data within the 400–1000 nm range, generating more than 200 continuous spectral bands for each scene. Image capture conducted under natural sunlight conditions, with a Polytetrafluoroethylene white reference panel used for radiometric calibration.

2.2.4. Infrared Thermography

The thermal properties of the Danbi stone carving were investigated using an infrared thermal imaging camera (InfReC R550, Avio, Tokyo, Japan). Measurements were performed in an outdoor environment to capture natural temperature variations. Thermal images were captured at a rate of one frame per second.

2.2.5. Microscopy

The sample’s microstructural characteristics were analyzed using a digital 3D video microscope (VHX-6000, Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Before observation, samples were embedded in epoxy resin and dried at room temperature. Cross-sectional surfaces were subsequently prepared by grinding and polishing to achieve a flat surface.

2.2.6. SEM-EDS

The micro-morphology and elemental composition of sample cross sections were further analyzed using a cold field-emission scanning electron microscope (Regulus 8100, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an EDS system. SEM imaging was conducted at accelerating voltages ranging from 10 to 15 kV with a working distance of 15 mm.

2.2.7. Microbiological Analysis

The samples were collected mainly by carbon conductive glue and sterile cotton swabs, which were then coated on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates containing 1.2% potato infusion powder, 2% glucose, and 2% agar. The plates were brought back to the laboratory and incubated in an incubator at 28 °C, and the target cultures were isolated and purified for 2–4 generations. 0.1% Tween-80 was used to collect the mycelium and spores of the fungi, extract the DNA, and then Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification was carried out, and the amplified products were sent to Jinwei Zhi company (Suzhou, China) for sequencing, and the results of the sequencing were compared with those of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to determine the species.

2.2.8. On-Site Monitoring

An on-site experimental setup was developed to assess the heat response of the Danbi stone (Figure 2). Temperature sensors were put in directly on the marble surface adjacent to the carved decorative area, with cables connected to a laptop-based data collecting system for real-time monitoring. Thermal conductivity was assessed with a thermal conductivity analyzer (CT08A, SMRF Technology, Beijing, China), using eight thermocouple sensors positioned at multiple depths within the simulated marble sample to record the vertical thermal gradient. The test was conducted in natural sunlight, beginning when direct radiation impacted the sample and concluding until it stopped, with data collected at one-second intervals.

Figure 2.

Simulated samples for field experiments.

2.3. Data Processing

2.3.1. Solar Absorption

The spectral reflectance R(λ) of the stone surface was quantified within the wavelength range of 350–2500 nm using reflectance spectral. The spectral absorptance A(λ) was calculated as Equation (1).

The absorptance was weighted according to the standard solar spectral irradiance E(λ) as specified in ISO 9845-1 [36], resulting in the effective absorptance Aeff. This parameter represents the integrated solar energy absorbed by the stone surface.

The relative increase in solar absorption due to surface darkening was quantified using ΔA, which compares the effective absorptance of blackened and spalling areas.

2.3.2. Thermal Stress

The net absorbed solar energy flux (Δq) was defined as the difference in effective absorptance between the blackened area and the spalling area.

Under steady-state heat transfer conditions, the temperature difference (ΔT) resulting from the variation in absorbed solar energy was estimated by dividing Δq by the overall heat transfer coefficient htot.

The thermally induced stress (σth) resulting from the temperature difference was calculated using the thermoelastic equation.

3. Results

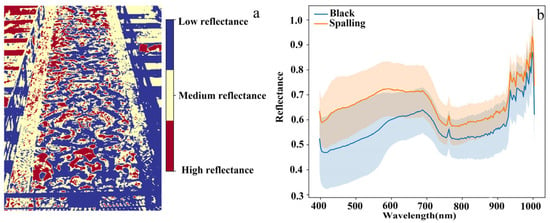

Previous studies have often considered black crust formation and marble spalling as independent deterioration processes, with black crust mainly attributed to atmospheric pollution and microbial colonization, and spalling associated with anisotropic thermal expansion of minerals [4,14]. However, their potential coupling under natural environmental conditions remains insufficiently explored. Figure 3 shows the spectral results capture from Hyperspectral. The HSI-based reflectance clustering maps show a clear spatial correspondence with visual deterioration features. Low-reflectance pixels are concentrated in zones affected by black crust, whereas high-reflectance pixels coincide with spalled areas. This indicates that surface darkening (black crust) and matrix exposure (spalling) form a continuous optical gradient on the Danbi surface. The average reflectance spectral curves of Figure 3b represent the mean values calculated from 50 spatial point measurements for Black and Spalling area, with shaded areas indicating standard deviation. The results demonstrate that the overall reflectance of the black crust areas in the wavelength range of 400–1000 nm is significantly lower than that of the spalling areas, with the most pronounced difference occurring within 400–700 nm, which corresponds to the main energy region of the solar spectrum.

Figure 3.

The Hyperspectral results of Danbi stone carvings: (a) reflectance clustering image; (b) average reflectance spectra, with shaded areas indicating the standard deviation calculated from 50 spatial point measurements.

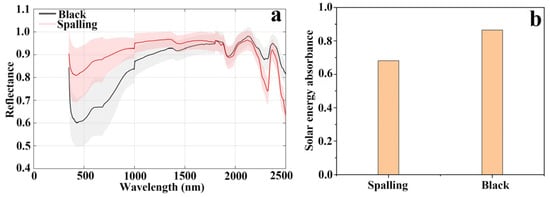

Figure 4 shows the reflectance spectral measurement results. The average reflectance spectral curves of Figure 4a represent the mean values calculated from 50 spatial point measurements for Black and Spalling area, with shaded areas indicating standard deviation. The results of the reflectance spectrum show that black crust reduces the average reflectance compared to spalling. With a decrease of 24% in the visible light region, a reduction of 8.5% in the near-infrared region, an increase of 2.1% in the SWIR. According to Equations (1)–(3), overall increase in solar energy absorption of approximately 27% (Figure 4b). The significant decrease in surface reflectance caused by black crust indicates a considerable rise in solar energy absorption. In contrast to laboratory tests with consistent temperature conditions [13], optically induced heterogeneity under natural sunshine can produce highly localized radiative heating, creating a condition for thermal stress concentration at the stone surface.

Figure 4.

The ASD spectral results of Danbi stone carvings: (a) average reflectance spectrum, with shaded areas indicating the standard deviation calculated from 50 spatial point measurements. (b) solar energy absorbance results.

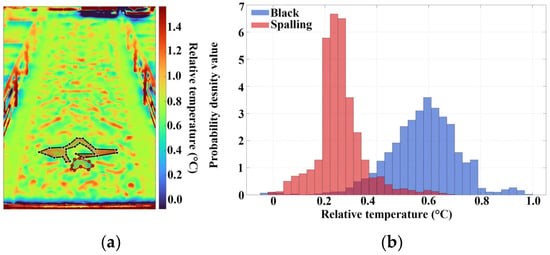

Figure 5 clearly shows the differences in surface temperature behavior between black and spalling areas. Figure 5a depicts the selected comparison area. Figure 5b illustrates the average relative temperature of the black areas exceeds the spalling areas by 0.3 °C. The proportion of high-temperature points in the selected black areas is 28.0%, whereas in the spalling areas, it is 0.2%. Thermal non-uniformity can lead to significant thermal stress gradients, thereby accelerating the spalling of the stone surface.

Figure 5.

The infrared thermography results of Danbi stone carvings: (a) Infrared thermal imaging. (b) Temperature distribution of the black area and the spalling area.

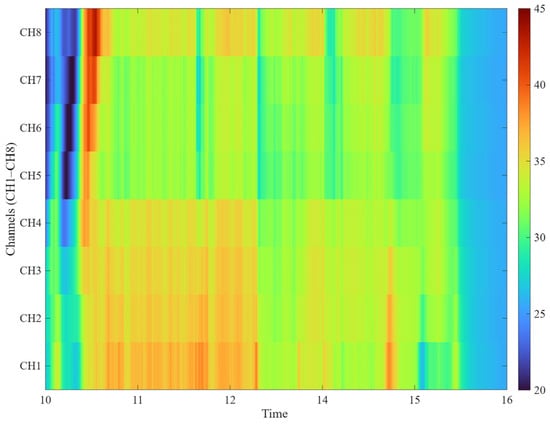

Figure 6 displays the thermal map of the in situ monitoring results. The black samples (CH5–CH8) exhibited rapid increase in temperature during the first hour of the experiment, reaching surface temperatures of 42 °C. The duration of peak temperature was significantly prolonged for the surface layer of CH8. The phenomenon indicates that the black crust markedly improves solar radiation absorption and accelerates heat conduction to deeper place. Moreover, it should be noted that the intermittent shading from surrounding buildings and trees resulted in temporal fluctuations in solar irradiation. Consequently, instantaneous temperature values varied among individual channels. Nevertheless, during periods of direct solar exposure, the black-crust-covered samples generally exhibited a stronger thermal response. In contrast, the white marble samples (CH1–CH4) showed more moderate temperature increases during the same period and maintained a comparatively uniform internal temperature distribution.

Figure 6.

The in situ monitoring results of simulated samples.

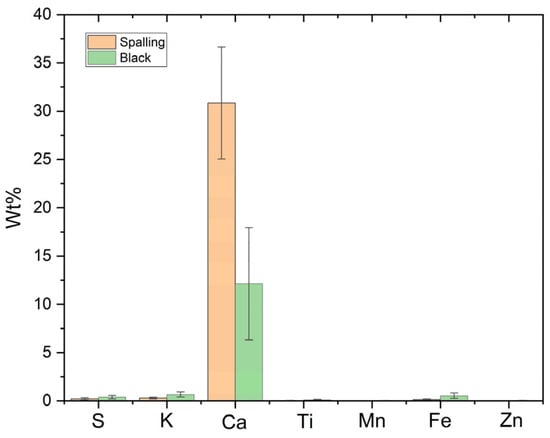

Figure 7 presents the p-XRF results. reveal unique elemental patterns between black areas and spalling areas, with the most pronounced variations found in black areas elements such as Fe, K, and S, alongside spalling areas like Ca. Ca reflects the exposure of the marble. The chemical compounds contain Fe, Ti, Zn, K, S may enhance the absorption of visible light and near-infrared light at the marble surface, hence increase surface temperature.

Figure 7.

The p-XRF of Danbi stone carvings.

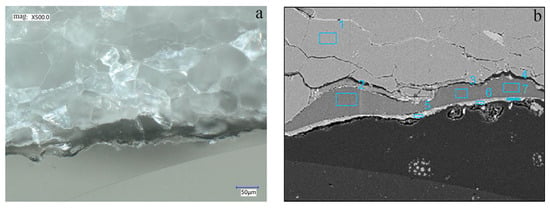

Figure 8 shows the microstructure and element analysis results of the marble. A dense and continuous black layer is observed on the surface of the stone (Figure 8a), forming a clear interface with the underlying marble substrate. Microcracks and spalling traces are evident between the black layer and the marble substrate (Figure 8b). Table 1 EDS analysis shows that the marble substrate is composed of 41% Ca, and 23% Mg, consistent with a carbonate-based lithology. The intermediate layer is dominated by 77% Si, suggesting the presence of a localized siliceous phase, such as quartz or silicate-rich deposits, rather than reflecting the overall composition of the marble. At the black sample surface, 1–2% Mg, 7–8% Al, 45–47% Si, 2–4.0% Ca, and 4–8% Fe was detected, likely related to atmospheric pollution and biological activity.

Figure 8.

The microstructure of the black area: (a) Microscope. (b) SEM.

Table 1.

EDS analysis results (wt %).

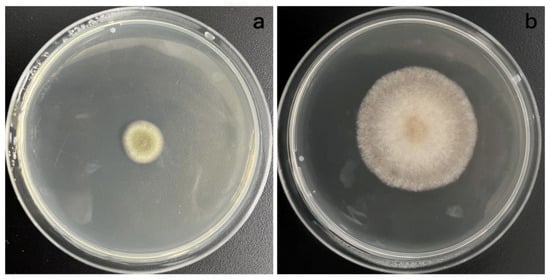

The results of microbial identification and detailed strain information are shown in Table 2, revealing that the contaminated area is colonized by multiple fungi and bacteria. Two melanin-producing fungi of particular concern are Cladosporium anthropophilum and Alternaria alternata. Figure 9 displays the single colony morphology observations of these two fungi. Their metabolic products, such as melanin, will change the stone’s color. The presence of melanin-producing fungi, such Cladosporium anthropophilum and Alternaria alternata, indicates that biological activity contributes to surface darkening [11]. Microbial pigmentation diminishes surface reflectivity and amplifies solar absorption, so creating a positive feedback loop that biological colonization increases heat loading and accelerates thermo-mechanical degradation. No visible biofilm was detected in spalling regions, signifying a distinct spatial correlation between microbial activity and the development of black crusts.

Table 2.

Microbial identification results and strain information for black areas.

Figure 9.

Morphological observation of single colonies of melanogenic fungi identified in black areas: (a) Cladosporium anthropophilum. (b) Alternaria alternata.

To further verify the plausibility of this coupling mechanism, we performed an estimation based on the observed reflectance difference. Under the highest annual mean solar irradiance in Beijing (498.99 W·m−2), the 27% solar energy absorption increase induced by black crust introduces an additional surface heat flux of 135 W·m−2.

According to Equation (5), the surface temperature differences of 2.2 K, corresponding to thermoelastic stresses of 4.7 MPa (Equation (6)). Within the range capable of initiating grain-boundary debonding and layer-parallel spalling observed in marble [37].

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that black crust accelerates the spalling of marble artifacts by increasing thermal stress. Reflectance and hyperspectral results indicate a 24% decrease in VIS reflectance and a 27% increase in solar absorption, resulting in an additional 135 W·m−2 heat flux. Infrared thermography and in situ monitoring indicate higher surface temperatures in black crust (0.3 °C on average) and peak temperatures reaching 42 °C, generating thermal gradients that can induce microcrack formation. XRF and SEM-EDS analyses reveal significant enrichment of Fe, Zn, Pb, Ti, As, and clay minerals in the black crust, whereas spalling areas exhibit increased Ca suggestive substrate exposure. Melanin-producing fungus (Cladosporium anthropophilum, Alternaria alternata) promote surface darkening and thermal absorption. Thermoelastic estimates indicate that the recorded increase inf absorption can generate 2.2 K temperature differences and 4.7 MPa stresses, which are within the threshold for grain-boundary debonding. The data collectively demonstrate that black crust serve as a significant catalyst for marble deterioration by increasing thermal stress, diminishing interfacial cohesion, and facilitating spalling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, J.C.; validation, B.S., J.Z. and W.H.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, W.H. and J.Z.; resources, B.S. and J.Z.; data curation, W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Interdisciplinary Research Project for Young Teachers of USTB (Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities), grant number FRF-IDRY-23-002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Confucian Temple and Imperial College Museum for the supply of material support in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations and Nomenclature

The following abbreviations and Symbol definitions are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| p-XRF | Portable X-ray Fluorescence |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| LA-ICP-MS | Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| ICP-OES | Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry |

| Py-GC-MS | Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| PLM | Polarized Light Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| HSI | Hyperspectral |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| Symbolic | Definition |

| R(λ) | reflectance at different wavelength |

| A(λ) | absorption at different wavelength |

| E(λ) | energy weighting of solar spectral power density at different wavelength (ISO 9845-1 reference spectrum) |

| λ | wavelength |

| λ1 | 350 nm |

| λ2 | 2500 nm |

| Aeff | absorption at 350–2500 nm |

| Aeff,black | absorption of the black area |

| Aeff,spalling | absorption of the spalling area |

| ΔA(%) | absorption enhancement |

| Δq | reflectance at different wavelength |

| hₜₒₜ | 60 W/m2K |

| ΔT | temperature Difference |

| E | 60 GPa |

| α | 26 × 10−6 /K |

| ν | 0.27 |

References

- Vidorni, G.; Sardella, A.; De Nuntiis, P.; Volpi, F.; Dinoi, A.; Contini, D.; Comite, V.; Vaccaro, C.; Fermo, P.; Bonazza, A. Air pollution impact on carbonate building stones in Italian urban sites. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2019, 134, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrizek, M.; Gregorič, A.; Ivančič, M.; Contini, D.; Skube, U.; Vidović, K.; Bele, M.; Šala, M.; Klanjšek, G.M.; Rigler, M.; et al. Characterization of fresh PM deposits on calcareous stone surfaces: Seasonality, source apportionment and soiling potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, M.; Pironti, C.; Comite, V.; Bergomi, A.; Fermo, P.; Bontempo, L.; Camin, F.; Proto, A.; Motta, O. A multi-analytical approach for the identification of pollutant sources on black crust samples: Stable isotope ratio of carbon, sulphur, and oxygen. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiz-Jimenez, C. Microbial melanins in stone monuments. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 167, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fu, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, Y.; Wei, S. Study on the mechanism of the black crust formation on the ancient marble sculptures and the effect of pollution in Beijing area. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchia, A.; Cerafogli, E.; Rivaroli, L.; Colasanti, I.A.; Aureli, H.; Biribicchi, C.; Brunori, V. Marble chromatic alteration study using non-invasive analytical techniques and evaluation of the most suitable cleaning treatment: The case of a bust representing queen Margherita di Savoia at the US Embassy in Rome. Analytica 2022, 3, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsos, D.; Kantarelou, V.; Palamara, E.; Karydas, A.G.; Zacharias, N.; Gerasopoulos, E. Characterization of black crust on archaeological marble from the Library of Hadrian in Athens and inferences about contributing pollution sources. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 53, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Kamenetskaya, O.V.; Vlasov, D.Y.; Zelenskaya, M.S.; Knauf, I.V.; Timasheva, M.A. Decaying of the marble and limestone monuments in the urban environment. Case studies from Saint Petersburg, Russia. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Geol. 2009, 54, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kosel, J.; Tomšič, N.; Mlakar, M.; Žbona, N.; Ropret, P. Mycological evaluation of the visible deterioration symptoms on the Spectatius family marble tomb (Slovenia). Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakal, T.C.; Cameotra, S.S. Microbially induced deterioration of architectural heritages: Routes and mechanisms involved. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2012, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, L.; Marvasi, M.; Perito, B. Characterization of the community of black meristematic fungi inhabiting the external white marble of the florence cathedral. J. Fungi. 2023, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuz, A.B.; Topal, T. Thermal and salt crystallization effects on marble deterioration: Examples from Western Anatolia, Turkey. Eng. Geol. 2007, 90, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonazza, A.; Sabbioni, C.; Messina, P.; Guaraldi, C.; De Nuntiis, P. Climate change impact: Mapping thermal stress on Carrara marble in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 4506–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaga-Starzec, K.; Lindqvist, J.E.; Schouenborg, B. Experimental study on the variation in porosity of marble as a function of temperature. In Natural Stone Weathering Phenomena, Conservation Strategies and Case Studies, 2nd ed.; Siegesmund, S., Weiss, T., Vollbrecht, A., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2002; Volume 205, pp. 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaga-Starzec, K.; Åkesson, U.; Lindqvist, J.E.; Schouenborg, B. Microscopic and macroscopic characterization of the porosity of marble as a function of temperature and impregnation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, P.; Bellopede, R. The influence of the climatic factors on the decay of marbles: An experimental study. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 3, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantisani, E.; Pecchioni, E.; Fratini, F.; Garzonio, C.A.; Malesani, P.; Molli, G. Thermal stress in the Apuan marbles: Relationship between microstructure and petrophysical characteristics. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2009, 46, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, A.; Ruiz-Agudo, E.; Cultrone, G.; Sebastián, E.; Siegesmund, S. Direct observation of microcrack development in marble caused by thermal weathering. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 62, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, A.; Leiss, B.; Alvarez-Lloret, P.; Cultrone, G.; Siegesmund, S.; Sebastian, E.; Cardell, C. Potential thermal expansion of calcitic and dolomitic marbles from Andalusia (Spain). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushakova, V.; Fuller, E.R., Jr.; Siegesmund, S. Microcracking in calcite and dolomite marble: Microstructural influences and effects on properties. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushakova, V.; Fuller, E.R., Jr.; Heidelbach, F.; Mainprice, D.; Siegesmund, S. Marble decay induced by thermal strains: Simulations and experiments. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 1281–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppes, M.C.; Griffing, D. Granular spalling of marble in nature: A thermal-mechanical origin for a grus and corestone landscape. Geomorphology 2010, 117, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassoni, E.; Franzoni, E. Influence of porosity on artificial deterioration of marble and limestone by heating. Appl. Phys. A 2014, 115, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. Investigation of marble deterioration and development of a classification system for condition assessment using non-destructive ultrasonic technique. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2020, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, A.; Pagnotta, S.; Lezzerini, M. Artificial Thermal Decay: Influence of Mineralogy and Microstructure of Sandstone, Calcarenite and Marble. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Yang, X.G. Thermally induced deterioration behaviour of two dolomitic marbles under heating–cooling cycles. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagnon, F.; Costanzo, D.; Ferrero, A.M.; Migliazza, M.R.; Pastero, L.; Umili, G. Simulation of temperature and chemical weathering effect on marble rocks. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Pérez, M.P.; Durán-Suárez, J.A.; Castro-Gomes, J. Study of the correlation of the mechanical resistance properties of Macael white marble using destructive and non-destructive techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavazas, M.L.; Bromblet, P.; Berthonneau, J.; Hénin, J.; Payan, C. Progressive thermal decohesion in Carrara marble monitored with nonlinear resonant ultrasound spectroscopy. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmutoğlu, Y. Prediction of weathering by thermal degradation of a coarse-grained marble using ultrasonic pulse velocity. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Vettori, S.; Giorgi, S.; Carretti, E.; Benedetto, F.D.; Dei, L.; Benvenuti, M.; Moretti, S.; Pecchioni, E.; Costagliola, P. Laboratory study of the sulfation of carbonate stones through SWIR hyperspectral investigation. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 32, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkanç, M.; Hüseyinca, M.Y.; Hatır, M.E.; Tosunlar, M.B.; Bozdağ, A.; Özen, L.; İnce, İ. Interpreting sulfated crusts on natural building stones using sulfur contour maps and infrared thermography. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Jia, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. Revealing Black Stains on the Surface of Stone Artifacts from Material Properties to Environmental Sustainability: The Case of Xianling Tomb, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, V.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Cardell, C.; Randazzo, L.; La Russa, M.F.; Fermo, P. A multi-analytical approach for the characterization of black crusts on the facade of an historical cathedral. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, A.P.; Cuzman, O.A.; Petrocchi, D.; Pinna, D.; Salvatici, T.; Perito, B. Black on white: Microbial growth darkens the external marble of Florence cathedral. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9845-1; Solar Energy—Reference Solar Spectral Irradiance at the Ground at Different Receiving Conditions—Part 1: Direct Normal and Hemispherical Solar Irradiance. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1992.

- Weiss, T.; Siegesmund, S.; Fuller, E.R. Thermal stresses and microcracking in calcite and dolomite marbles via finite element modelling. In Natural Stone Weathering Phenomena, Conservation Strategies and Case Studies, 2nd ed.; Siegesmund, S., Weiss, T., Vollbrecht, A., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2002; Volume 205, pp. 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.