Abstract

Background: Satisfaction with care is an important outcome measure in end-of-life care. Validated instruments are necessary to evaluate and disseminate interventions that improve satisfaction with care at the end of life, contributing to improving the quality of care offered at the end of life to the Portuguese population. The purpose of this study was to perform a cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric analysis of the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire. Methods: Methodological research with an analytical approach that includes translation, semantic, and cultural adaptation. Results: The Portuguese version comprised 24 items. A panel of experts and bereaved family members found it acceptable and that it had face and content validity. A total of 269 caregivers across several care settings in the northern region of Portugal were recruited for further testing. The internal consistency analysis of the adapted instrument resulted in a global alpha value of 0.950. The correlation between the adapted CANHELP questionnaire and a global rating of satisfaction was of 0.886 (p < 0.001). Conclusions: The instrument has good psychometric properties. It was reliable and valid in assessing caregivers’ satisfaction with end-of-life care and can be used in both clinical and research settings.

1. Introduction

The quality of care provided to individuals at the end of life, and to their family members, has become an important health and social issue across the world [1]. Quality end-of-life care is considered a right for all citizens and the responsibility of every government [2]. Thus, improving care at the end of life is an international priority [3,4,5] and it is key to improving the quality of life for patients and their families [2].

Understanding how care is perceived by family members across care settings is essential to identify specific domains of care that need to be improved [1] and that influence how end-of-life care is delivered and experienced [6].

Although satisfaction with care has its limitations as an endpoint and does not equate to the overall quality of care, it is considered an important domain within the overall quality of end-of-life care [6].

The comprehension of families’ levels of satisfaction with end-of-life care is important to improve individual care and to introduce quality improvement initiatives to the health system. The use of these instruments will also allow families, policymakers, and the public to hold individuals and organizations accountable for the quality of care provided to patients at the end of life [6,7,8].

Care provided at the end of life is receiving growing attention across the world, particularly in Portugal. Although Portugal is considered to have a generalized provision of palliative care [9], it has one of the highest rates of adults in need of palliative care [10] and there are still inequities in the distribution of, and access to, palliative care [11].

Nevertheless, knowledge about the care provided at the end of life in Portugal across care settings is still limited [12]. Thus, there is also little evidence regarding the quality of care at the end of life. To evaluate the quality of care at the end of life, it is necessary to use standardized and validated measurement tools, including those that measure families’ satisfaction as an important indicator of the quality of care [6,13,14].

Recent research has been conducted aiming to identify basic quality indicators for palliative care services [8,15,16]. This evidence shows that family satisfaction regarding different aspects of palliative care is considered to be an important outcome measure in three different palliative care quality domains, namely the structure and process of care, psychological and psychiatric aspects of care, and care of the imminently dying patient [8].

A recent bibliometric study regarding the postgraduate academic publications in Portugal in the field of palliative care over the past few years showed that few methodological studies were conducted in Portugal [17]. Methodological studies are important for the development of adequate measurement instruments to assess palliative care-related quality indicators [18]. Evidence shows that the lack of reliable instruments is a factor hindering the assessment of quality indicators in palliative care [19,20].

Currently, there are some tools available worldwide to specifically assess families’ satisfaction of end-of-life care [21]. However, in Portugal, there is only one validated tool that specifically measures families’ satisfaction with end-of-life care: FAMCARE [22]. A few studies using small samples have been conducted in Portugal to examine the effectiveness of the FAMCARE tool [23,24].

Although FAMCARE was initially developed to measure family satisfaction with advanced cancer care [25], it is often used in palliative care research. However, it has considerable limitations as it was designed to measure the satisfaction levels of family members who received home-based palliative care, it does not always include all the aspects of the care provided, and the psychometric properties have not yet been sufficiently well-established because of the small sample size in the validation testing [26]. Also, the use of FAMCARE with bereaved family members is not well-established. Although FAMCARE has been used in bereaved family members in international studies [27], this has not been done or tested in Portugal. For the reasons, it was necessary to validate an instrument that could be used across care settings and applied to bereaved family members.

The CANHELP (Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project) instruments were developed to measure satisfaction with end-of-life care [6,28]. CANHELP is a self-reporting instrument that was developed and validated for patients at the end of life and their family members to assess satisfaction with a variety of actionable items. The CANHELP Bereavement Questionnaire is a 43-item instrument with two items about overall satisfaction with care and 41 items that fall into one of six quality of care subscales: doctor and nurse characteristics; illness management; health service characteristics; communication and decision-making; you and your relationships with others; and spirituality and meaning. Although the instrument showed good internal consistency reliability, the length of the interview may limit its uptake and clinical utility.

A shorter version of the instrument was developed [29,30]. The CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire is a 24-item instrument with two items about overall satisfaction with care and 22 items that fall into one of five quality of care subscales: relationship with the doctors; characteristics of doctors and nurses; illness management; communication and decision making; and your involvement. Responses to each item are scored on a five-point scale ranging from ‘not at all satisfied’ (1) to ‘completely satisfied’ (5) [31].

The aim of this study was to perform the cultural adaptation and validation of the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a methodological study including translation, semantic, and cultural adaptation, and the evaluation of the psychometric properties, according to the guidelines proposed by Beaton et al. [32].

2.2. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation Processes

The process of cultural adaptation looks at both language (translation) and cultural adaptation issues, while preparing a questionnaire for use in another setting. The following stages composed the translation and semantic and cultural adaptation of the instrument [32]:

- Linguistic translation of the instrument into European Portuguese by three translators, native in Portugal and fluent in American English. Two translators were unaware of the concept under study, but the third was an expert in the palliative care field.

- Synthesis and review of the first translation.

- Back-translation of the reviewed version by two other translators, natives of the USA and fluent in Portuguese. They did the semantic analysis and had an agreement result of 100.0%.

- Review of all translations by a panel of experts (one expert in research and methodological studies, two experts in palliative care, and one expert in bereavement, in addition to all translators and back-translators). The original developers of the questionnaire were in close contact with the panel of experts during this part of the process.

- Assessment of face and content validity through a pre-test on a sample of 20 bereaved family members, which aimed to verify the understanding of the items, evaluate the ease of using the response set, and estimate the response time. The instrument was easily understood, and the bereaved family members answered when requested. The average answer time was 10 min for the entire questionnaire. After the face validity of the instrument was analyzed, its psychometric properties were examined. The literature proposes the inclusion of 5–10 participants per item for the sample [33]. The inclusion of 10 participants per item was estimated and the final sample was composed of 269 bereaved family members.

2.3. Participants, Setting and Procedure

The participants were bereaved family members knowledgeable about the healthcare provided during the last three months of life to an adult decedent (aged 18 years and older). To identify potential participants, the death certificates of all adults (aged 18 years and older) that were available in the national electronic death certificate registration were analyzed. Records of decedents where the cause of death codes were associated with external or accidental causes, suicides, pregnancy complications, or medical and surgical complications, as well as death certificates that had an uncertain cause of death were excluded.

In Portugal, death certificates do not have information regarding family members and thus, it was necessary to cross information and to search for a phone number on the health system national registration using the health national registration number provided on the death certificate. A first phone call was made to inform the participants about the study’s aims and the voluntary nature of their participation. They were also given guarantees of data confidentiality and anonymity. Informed consent was obtained from each bereaved family member. After that, a phone interview was scheduled at a date of the bereaved family member’s preference. Subsequently, the instrument was applied through a phone interview conducted by trained interviewers. All interviews were conducted three to 12 months after death. As the period of bereavement is recognized as a sensitive time, this interval was decided to respect the family bereavement period but also to guarantee that the memory of the experience was recent enough to be considered reliable.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed through means and standard deviation, or numbers and percentages of the demographic and clinical variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to check the distribution of the variables enrolled. A bivariate correlation by Pearson was used.

The assumptions used in the original version were followed and the internal consistency of the scale was obtained using Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted and corrected item-total correlation were also obtained. According to the literature, alpha values under 0.50 are unacceptable, from 0.50 to 0.60 are questionable, from 0.60 to 0.70 are acceptable, from 0.70 to 0.80 are good, from 0.80 to 0.90 are very good, and over 0.90 are considered excellent [34,35].

Criterion-related validity was determined through the concurrent use of a single-item, global rating of caregivers’ general satisfaction with the care received in the last three months of life (scored between 1 and 5, meaning that 1 was the worst level of satisfaction possible and 5 the best level of satisfaction possible). This option is justified by the fact that there isn’t a validated tool in Portugal to assess bereaved family members’ satisfaction with the care received in the last months of life regardless of the existing pathology or setting of care. This was performed using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Convergent–discriminant validity was performed using an exploratory factorial analysis considering the principal components method with orthogonal rotation (varimax method with Kaiser normalization).

It was not possible to perform test–retest reliability, as the purpose of the instrument was to assess the bereaved families’ satisfaction with the care received in the last three months of life. As this might be considered a sensitive matter, we believe that respecting human dignity should have priority over the interests of the research.

The data were analyzed using SPSS, version 23, for Windows. A level of significance of 0.05 was assumed.

2.5. Ethical Procedures

First, a research protocol was designed. It was then submitted, analyzed, and approved by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority (number 9607/2016), ethics committee (number P361/09-2016), and the assistant secretary of state and health. A collaboration protocol was also signed between the research team and the Directorate General of Health.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

All 269 participants were bereaved Portuguese family members from the north region recruited through the identification provided in the health system national registration after analysis of the death certificates. The majority of the participants were female (78.4%) and married (59.5%), and were most often daughters of the deceased (47.6%). The average age was 58.2 years (sd = 13.3 years; minimum = 18 years and maximum = 91 years). The interview was conducted, on average, 295.93 days after the death of the relative (sd = 76.6 days; minimum = 93 days and maximum = 364 days).

3.2. Reliability

Considering the 24 items of the scale, the analysis of internal consistency reliability revealed an alpha of 0.950. The global alpha when removing items were also analyzed (Table 1). Although Cronbach’s alpha would increase if items 14, 16, and 23 were deleted, it was decided to retain them, as the alpha obtained is already considered excellent.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency for the items.

The English and Portuguese item description of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire is available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Item description of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire

3.3. Construct Validity

During the translation and cultural adaptation phase, it was observed that the scale was answered quickly and that there were no suggestions for alterations in items or terms considered inadequate or unnecessary, which shows a good understanding and acceptance of the items by the participants.

Concurrent validity was determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient, and a value of 0.886 (p < 0.001) was obtained.

Regarding convergent–discriminant validity, an exploratory factorial analysis considering the principal components method with orthogonal rotation (varimax method with Kaiser normalization) was performed. The initial exploratory factor analysis of our study proposed four factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Exploratory factorial analysis considering the principal components method with orthogonal rotation (varimax method with Kaiser normalization).

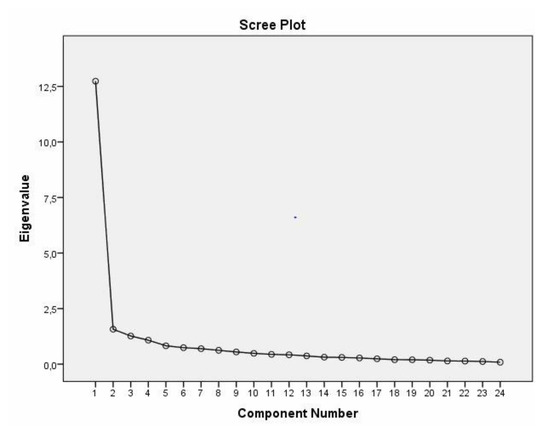

The CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire proposes the evaluation of five quality subscales, namely relationship with the doctors, characteristics of doctors and nurses, illness management, communication and decision making, and your involvement. Despite these considerations, the instrument remains unidimensional as the first factor explains 53.061% of the total variance of the items and the second factor explains 6.545%, indicating unidimensional adequacy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scree plot extracted from the exploratory factor analysis of the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire.

4. Discussion

The current study provides evidence for the reliability and validity of the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric analysis of this instrument in Portugal. A rigorous methodology for the translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation processes following the recommended guidelines has been used in this study.

The cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric testing of this instrument were achieved satisfactorily following the recommendations of the international guidelines [36,37]. Regarding this, the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire showed satisfactory psychometric properties. The face and content validity of the instrument was acceptable, which indicates that all items are relevant for the construct measurement. The internal consistency analysis was satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.950), suggesting excellent homogeneity of the items. These values are in line with those reported in the original studies [29,30].

In terms of concurrent criterion-related validity, there was adequate correlation with the single-item global rating of caregiver satisfaction with the care received in the last three months of life, which might indicate that the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire is adequate to measure satisfaction with the care received in the last months of life.

An after-death assessment of the caregivers’ satisfaction with the care received in the last months of life would allow us to identify, evaluate, and disseminate interventions that improve satisfaction with care at the end of life, which would also, indirectly, improve the quality of care at the end of life. For that, it is necessary to have valid and reliable instruments. Thus, we believe that the translation and validation of the Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire will contribute to improving care at the end of life in the Portuguese population.

This study followed a rigorous methodology and was developed across care settings, which allow us to be confident regarding the generalizability of the results produced here. Nevertheless, there are some limitations. Effects related to memory might be considered a limitation of this study, as it is a retrospective evaluation by caregivers. In this context, the evaluation of satisfaction with care could be affected by the amount of time between the death and the evaluation. Proxy reports after end-of-life care can be obtained at varying time intervals post-death. Regarding this, it was decided to conduct the interview three to 12 months after the patient’s death. This is a conventional time frame for evaluating this construct, as similar periods of time were used in other studies [38,39,40]. However, we recognize that other intervals may provide more accurate data. Future research should explore the optimal timing for the collection of data from bereaved caregivers. Also, the test–retest reliability was not performed, which is the reason why the instruments’ sensitivity to change was not evaluated.

5. Conclusions

The Portuguese version of the CANHELP Lite Bereavement Questionnaire is a valid and reliable instrument for the assessment of satisfaction with end-of-life care and can be used in both clinical and research settings.

This is the first instrument available in Portugal to assess bereaved family members’ satisfaction with end-of-life care and it could be very important as it might be a valuable contribution to improve the Portuguese health system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., A.F. and J.M.; Data curation, A.P., A.F., A.R.A., C.G. and J.S.; Formal analysis, A.P. and A.F.; Investigation, A.P., A.F. and J.M.; Methodology, A.P., A.F. and L.T.; Project administration, A.P. and A.F.; Supervision, J.M., S.P. and O.F.; Validation, L.T. and D.K.H.; Writing—original draft, A.P. and A.F.; Writing—review & editing, A.R.A., C.G., J.S., L.T., D.K.H., S.P. and O.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding has been received to facilitate the completion of this work.

Acknowledgments

To Jessica Oliveira and Laura Davies for the careful revision of this paper. To the Epidemiological Division of the Directorate-General of Health for all the help provided during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stajduhar, K.; Sawatzky, R.; Cohen, S.R.; Heyland, D.K.; Allan, D.; Bidgood, D.; Norgrove, L.; Gadermann, A.M. Bereaved family members’ perceptions of the quality of end-of-life care across four types of inpatient care settings. BMC Palliat. Care. 2017, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index Ranking palliative care across the world. Available online: https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/2015%20EIU%20Quality%20of%20Death%20Index%20Oct%2029%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Carstairs, S.; Beaudoin, G.A. Quality End of Lifecare: The Right of Every Canadian; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000.

- NHS. Actions for End of Life Care: 2014-16. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/actions-eolc.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- Comissão Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos. Plano Estratégico para o Desenvolvimento dos Cuidados Paliativos Biénio 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.sns.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/PEDCP-2019-2020-versao-final-10.02.2019.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- Heyland, D.K.; Cook, D.J.; Rocker, G.M.; Dodek, P.M.; Kutsogiannis, D.J.; Skrobik, Y.; Jiang, X.; Day, A.G.; Cohen, S.R. The development and validation of a novel questionnaire to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care: The Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project (CANHELP) Questionnaire. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, D.L.; Curtis, R.; Engelberg, R.A.; McCown, E. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 139, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capelas, M.L. Indicadores de Qualidade para os Serviços de Cuidados Paliativos; Universidade Católica Editora: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, T.; Connor, D.; Clark, D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 45, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance; World Health Organization. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life; Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Observatório Português do Sistema de Saúde. Relatório Primavera 2017. Available online: http://opss.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Relatorio_Primavera_2017.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Pereira, A.; Ferreira, A.; Martins, J. Healthcare received in the last months of life in Portugal: A systematic review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dy, S.; Shugarman, L.; Lorenz, K.; Mularski, R.; Lynn, J. A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularski, R.; Dy, S.; Shugarman, L.; Wilkinson, A.M.; Lynn, J.; Shekelle, P.G.; Morton, S.C.; Sun, V.C.; Hughes, R.G.; Hilton, L.K.; et al. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health. Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 1848–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelas, M.L.; Nabal, M.; Rosa, F.C. Basic quality indicators for palliative care services in Portugal: 1st step—A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2012, 26, 385–452. [Google Scholar]

- De Roo, M.L.; Leemans, K.; Claessen, S.J.; Cohen, J.; Pasman, H.R.; Deliens, L.; Francke, A.L.; EURO IMPACT. Quality indicator for palliative care: Update of a systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2013, 46, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Ferreira, A.; Martins, J. Academic palliative care research in Portugal: Are we on the right track? Healthcare 2018, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelas, M.; Vicuna, M.; Rosa, F. Quality assessment in palliative care—An overview. Eur. J. Palliat. Care. 2013, 20, 196–198. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, M. Outcome evaluation in palliative care. Med. Clin. 2004, 123, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Assessment Tools for Palliative Care. Available online: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/palliative-care-tools/research-protocol (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Loney, E.; Lawson, B. An Ongoing, Province-Wide Patient-Focused, Family Centred Quality Measurement Strategy for the Experience of End-of-Life Care from the Perspective of the bereaved Family Member Caregiver; Network for End of Life Studies Dalhousie University: Nova Scotia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.C. A Família em Cuidados Paliativos—Valiação da Satisfação dos Familiares dos Doentes em Cuidados Paliativos: Contributo para a validação da escala FAMCARE. Master’s Thesis, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, A.R. Aferição do grau de satisfação dos familiares de doentes internados no Serviço de Medicina Paliativa do Centro Hospitalar Cova da Beira. Master’s Thesis, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bica, I.; Cunha, M.; Andrade, A.; Dias, A.; Ribeiro, O. O Doente em Situação Paliativa: Implicações da Funcionalidade Familiar na Satisfação dos Familiares face aos Cuidados de Saúde. Servir 2016, 59, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanon, L.J. Validity and reliability of the FAMCARE Scale: Measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 36, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Chihara, S.; Kashiwagi, T.; Quality Audit Committee of the Japanese Association of Hospice and Palliative Care Units. A scale to measure satisfaction of bereaved family receiving inpatient palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, M.; Aoyama, M.; Nakahata, M.; Yamada, Y.; Abe, M.; Yanagihara, K.; Shirado, A.; Shutoh, M.; Okamoto, Y.; Hamano, J.; et al. Development the Care Evaluation Scale Version 2.0: A modified version of a measure for bereaved family members to evaluate the structure and process of palliative care for cancer patient. BMC Palliat. Care. 2017, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, D.K.; Dodek, P.; Rocker, G.; Groll, D.; Gafni, A.; Pichora, D.; Shortt, S.; Tranmer, J.; Lazar, N.; Kutsogiannis, J.; et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: Perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006, 174, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, D.K.; Jiang, X.; Day, A.G.; Cohen, S.R. The development and validation of a shorter version of the Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project Questionnaire (CANHELP Lite): A novel tool to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2013, 46, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadin, S.; Ali Miandad, M.; Kelley, M.L.; Marcella, J.; Heyland, D.K. Measuring family members’ satisfaction with end-of-life care in long-term care: Adaptation of the CANHELP Lite Questionnaire. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 4621592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARENET. Resource Centre. Available online: https://www.thecarenet.ca/docs/CANHELP_Lite/CANHELP%20Lite%20Bereavement%2011%20Nov%202014.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Beaton, D.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, D.; Ferraz, M.B. Recommendations for the cross-cultural adaptation of the DASH & QuickDASH outcome measures; Institute for Work & Health. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surgeons. 2007, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L. Metodologia de Investigação em Psicologia e Saúde; Livpsic Editoria: Oliveira de Azeméis, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C.T. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Hongkong, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, L.; Freire, T. Metodologia da investigação em psicologia e educação; Psiquilibrios: Braga, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Test Commission. The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (Second edition). Available online: https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation_2ed.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Teno, J.M.; Clarridge, B.R.; Casey, V.; Welch, L.C.; Wetle, T.; Shield, R.; Mor, V. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2014, 291, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, R.; Krawczyk, M. Family members’ perceptions of end-of-life care across diverse locations of care. BMC Palliat. Care. 2013, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, F.; Lawson, B.; Johnston, G.; Asada, Y.; McIntyre, P.F.; Grunfeld, E.; Flowerdew, G. Bereaved family member perception of patient-focused family centred care during the last 30 days of life using a mortality follow-back survey: Does location matter? BMC Palliat. Care. 2014, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).