The Association Between Doctor–Patient Conflict and Uncertainty Stress During Clinical Internships Among Medical Students: A Panel Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measurement

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gianaros, P.J.; Wager, T.D. Brain-Body Pathways Linking Psychological Stress and Physical Health. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza-Silva, J.C.; Martins, C.A.; Garciazapata, M.T.A.; Barbosa, M.A. Parental stress around ophthalmological health conditions: A systematic review of literature protocol. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara, J.D.S.; Toya, T.; Ahmad, A.; Clark, M.M.; Gilliam, W.P.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Mental Stress and Its Effects on Vascular Health. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 951–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Dawans, B.; Trueg, A.; Kirschbaum, C.; Fischbacher, U.; Heinrichs, M. Acute social and physical stress interact to influence social behavior: The role of social anxiety. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, R.; Oluwasina, F.; El Gindi, H.; Eboreime, E.; Nwachukwu, I.; Hrabok, M.; Agyapong, B.; Abba-Aji, A.; Agyapong, V. Burnout among physicians: Prevalence and predictors of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion and professional unfulfillment among resident doctors in Canada. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houpy, J.C.; Lee, W.W.; Woodruff, J.N.; Pincavage, A.T. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med. Educ. Online 2017, 22, 1320187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wizner, M.; Kawalec, A.; Rodak, N.; Wilczyński, K.M.; Janas-Kozik, M. Depression, anger and coping strategies of students in polish medical faculties. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S544–S545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, M.R.; Bottrell, M.M. Combining Ethics Inquiry and Clinical Experience in a Premedical Health Care Ethics Internship. Acad. Med. 2022, 97, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, H.M.; Irshad, M.; Al Zunitan, M.A.; Al Sulihem, A.A.; Al Dehaim, M.A.; Al Esefir, W.A.; Al Rabiah, A.M.; Kameshki, R.N.; Alrowais, N.A.; Sebiany, A.; et al. Prevalence of stress in junior doctors during their internship training: A cross-sectional study of three Saudi medical colleges’ hospitals. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. A Study on Perceived Stress among Medical Students from a Private Medical College in North India. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grush, K.A.; Christensen, W.; Lockspeiser, T.; Adams, J.E. Secondary Traumatic Stress in Medical Students During Clinical Clerkships. Acad. Med. 2025, 100, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogesh, M.; Ekka, A.; Gandhi, R.; Damor, N. Trial by fire: The qualitative essence of interns’ baptism into medical responsibility. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2024, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Jin, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Cheng, Y.; You, J.; Deng, G. An investigation of the intention and reasons of senior high school students in China to choose medical school. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Shin, H.S. Exploring barriers facilitators for successful transition in new graduate nurses: Amixed methods study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020, 36, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, G.; Brisson, G. The Sibs Program: A Structured Peer-Mentorship Program to Reduce Burnout for First-Year Medical Students. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnotta, A.; Antonacci, R.; Curiale, L.; Sanzone, L.; Kapoustina, O.; Cervantes, A.; Monaco, E.; Tsimicalis, A. Exploring Novice Nurses’ Experiences During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nurs. Educ. 2023, 62, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Lopez, F.J.; Vervliet, B.; Cobos, P.L. Intolerance of uncertainty as a vulnerability factor for excessive and inflexible avoidance behavior. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 104, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Jiang, S.; Yang, T. Impact of psychological uncertainty stress on academic performance among medical students: A nationwide empirical study of 50 universities. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 12, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, A.; McEwen, B.S.; Friston, K. Uncertainty and stress: Why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 156, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawadi, H.; Shami, R.; El-Awaisi, A.; Al-Moslih, A.; Abdul Rahim, H.; Du, X.; Moawad, J.; Al-Jayyousi, G.F. Exploring the challenges of virtual internships during the COVID-19 pandemic and their potential influence on the professional identity of health professions students: A view from Qatar University. Front Med. 2023, 10, 1107693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Groneberg, D.A. Physicians’ working conditions in hospitals from the students’ perspective (iCEPT-Study)—Results of a web-based survey. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2016, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Yang, M.; Zhu, N.; Yuan, Y. Exploring the cultivation of psychological resilience in medical students from the perspective of doctor-patient relationship. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 1511–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Peng, S.; Yang, T. The influence of doctor-patient conflict on medical students’ psychological stress: An empirical study based on 31 universities in China. J. Social. Sci. 2020, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T. Health Research: Social and Behavioral Theory and Methods; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 72–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Yang, T. Late bedtime, uncertainty stress among Chinese college students: Impact on academic performance and self-rated health. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 2915–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furstenberg, S.; Prediger, S.; Kadmon, M.; Berberat, P.O.; Harendza, S. Perceived strain of undergraduate medical students during a simulated first day of residency. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnicki, D.M. Emotional Distress During Internship: Causes Support Systems. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 3434–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannello, P.; Mottini, A.; Tirelli, S.; Riva, S.; Antonietti, A. Ambiguity and uncertainty tolerance, need for cognition, and their association with stress. A study among Italian practicing physicians. Med. Educ. Online 2017, 22, 1270009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hall, K.; Anakin, M.; Pinnock, R. Medical students’ responses to uncertainty: A cross-sectional study using a new self-efficacy questionnaire in Aotearoa New Zealand. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Ma, W. The effects of clinical learning environment and career adaptability on resilience: A mediating analysis based on a survey of nursing interns. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond-Brown, L. The doctor-patient relationship as a toolkit for uncertain clinical decisions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 159, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.M.; Wang, W.; Zhornitsky, S.; Dhingra, I.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.R. Reward sensitivity and electrodermal responses to actions and outcomes in a go/no-go task. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilgen, J.S.; Eva, K.W.; de Bruin, A.; Cook, D.A.; Regehr, G. Comfort with uncertainty: Reframing our conceptions of how clinicians navigate complex clinical situations. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2019, 24, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.; Moutoussis, M.; Bilek, E. Simulating the computational mechanisms of cognitive and behavioral psychotherapeutic interventions: Insights from active inference. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.; Shah, R.; Shah, S. Medical student perspective on stress: Tackling the problem at the root. Med. Educ. Online 2019, 24, 1633173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, C.K.; Mukhtar, F.; Ibrahim, N.; Keng, S.L.; Sidik, S.M. Effects of a brief mindfulness-based intervention program for stress management among medical students: The Mindful-Gym randomized controlled study. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2015, 20, 1115–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaisaard, C.; Wannarit, K.; Pattanaseri, K. Mindfulness-based interventions reducing and preventing stress and burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2022, 69, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.E.; Lowe, W.A. Well-being and uncertainty in health care practice. Clin. Teach. 2019, 16, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 58 | 47.5 |

| Female | 64 | 52.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Han | 121 | 99.2 |

| Minority | 1 | 0.8 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 46 | 37.7 |

| Township | 18 | 14.8 |

| County | 24 | 19.7 |

| Urban | 34 | 27.9 |

| Year | ||

| Grade Four | 63 | 51.6 |

| Grade Five | 59 | 48.4 |

| Grades | ||

| Upper-third | 36 | 29.5 |

| Middle-third | 51 | 41.8 |

| Lower-third | 35 | 28.7 |

| Father’s educational level | ||

| Elementary school and below | 11 | 9.0 |

| Junior high school | 41 | 33.6 |

| High school | 29 | 23.8 |

| College diploma | 23 | 18.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 18 | 14.8 |

| Mother’s educational level | ||

| Elementary school and below | 15 | 12.3 |

| Junior high school | 46 | 37.7 |

| High school | 28 | 23.0 |

| College diploma | 21 | 17.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 12 | 9.8 |

| Group | N | Uncertainty Stress | Doctor–Patient Conflict | Reference Norm from Family or Relatives | Reference Norm from Friends | Reference Norm from Classmates | Reference Norm from Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

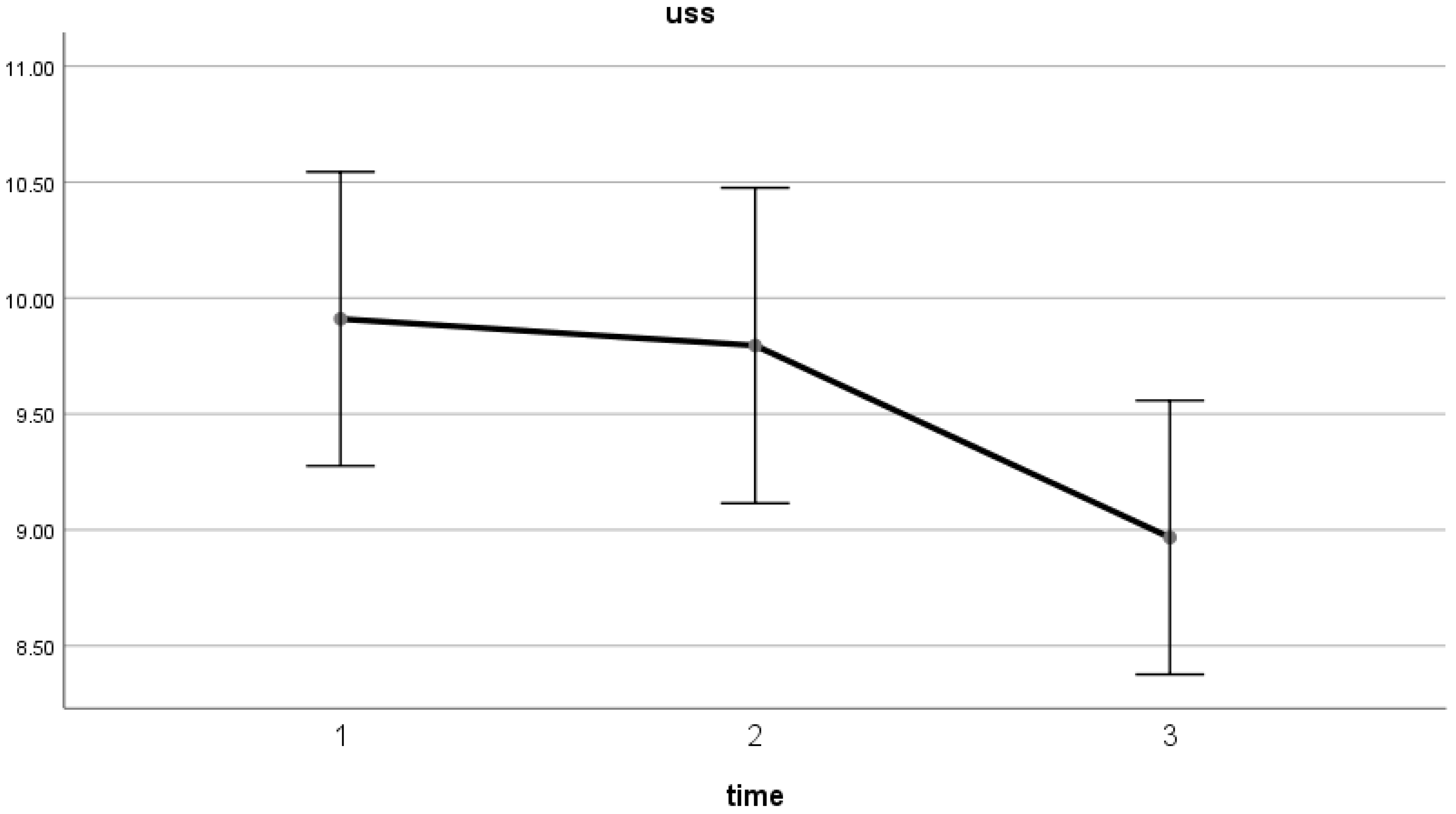

| Time1 | 122 | 9.91 (0.32) a | a | 1.78 (0.07) | 1.80 (0.06) | 1.89 (0.07) | 1.81 (0.07) a |

| Time2 | 122 | 9.80 (0.34) a | b | 1.88 (0.06) | 1.90 (0.06) | 2.02 (0.07) | 1.99 (0.07) b |

| Time3 | 122 | 8.97 (0.30) b | b | 1.73 (0.06) | 1.80 (0.06) | 1.93 (0.07) | 2.01 (0.07) b |

| Wald (p) | 7.25 (0.03) | 6.65 (0.04) | 2.25 (0.10) | 3.29 (0.19) | 3.33 (0.19) | 7.06 (0.03) |

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uncertainty stress → doctor–patient conflict | 1.068 | 0.525 | 2.036 | 0.042 * |

| uncertainty stress → reference norm from family or relatives | 0.503 | 0.463 | 1.086 | 0.278 |

| uncertainty stress → reference norm from friends | −0.888 | 0.520 | −1.078 | 0.088 |

| uncertainty stress → reference norm from classmates | 0.229 | 0.408 | 0.561 | 0.575 |

| uncertainty stress → reference norm from teachers | 0.856 | 0.373 | 2.295 | 0.022 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Ying, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W. The Association Between Doctor–Patient Conflict and Uncertainty Stress During Clinical Internships Among Medical Students: A Panel Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091080

Wang H, Ying X, Zhang L, Yang T, Zhang W. The Association Between Doctor–Patient Conflict and Uncertainty Stress During Clinical Internships Among Medical Students: A Panel Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091080

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Huihui, Xinxin Ying, Lujin Zhang, Tingzhong Yang, and Weifang Zhang. 2025. "The Association Between Doctor–Patient Conflict and Uncertainty Stress During Clinical Internships Among Medical Students: A Panel Study" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091080

APA StyleWang, H., Ying, X., Zhang, L., Yang, T., & Zhang, W. (2025). The Association Between Doctor–Patient Conflict and Uncertainty Stress During Clinical Internships Among Medical Students: A Panel Study. Healthcare, 13(9), 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091080