The Socio-Ecological Factors of Physical Activity Participation in Preschool-Aged Children with Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2.2. Intrapersonal Level

2.2.3. Interpersonal Level

2.2.4. Organizational Level

2.2.5. Environmental Level

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. PA Participation

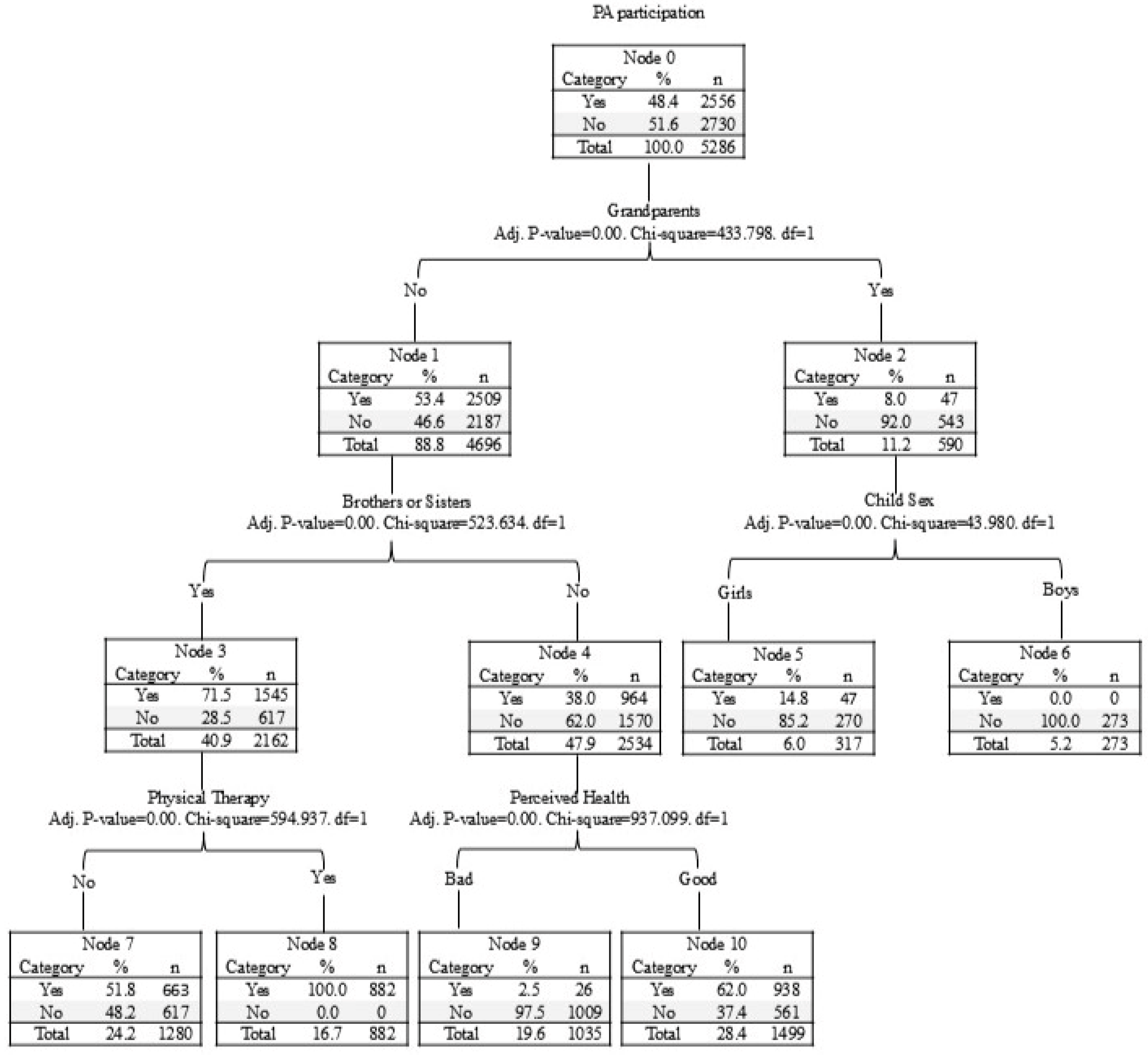

3.2. Decision Tree Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A Systematic Review of the Psychological and Social Benefits of Participation in Sport for Children and Adolescents: Informing Development of a Conceptual Model of Health through Sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.-C.; Ku, B.; Leung, W.; MacDonald, M. The Effect of Physical Activity Interventions on Executive Function Among People with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 52, 1030–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.-Y.; Hewitt, L.; Jennings, C.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Stearns, J.A.; Unrau, S.P.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Physical Activity and Health Indicators in the Early Years (0–4 Years). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner-Seitz, N.; Pate, R.R.; Paul, I.M. Physical Activity in Infancy and Early Childhood: A Narrative Review of Interventions for Prevention of Obesity and Associated Health Outcomes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1155925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service. 2022. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/physical-activity-guidelines-children-under-five-years/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Bruijns, B.A.; Truelove, S.; Johnson, A.M.; Gilliland, J.; Tucker, P. Infants’ and Toddlers’ Physical Activity and Sedentary Time as Measured by Accelerometry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, J.M.; Pierce, S.; Mohan, M.; Skorup, J.; Paremski, A.; Bochnak, M.; Prosser, L.A. Physical Activity in Non-Ambulatory Toddlers with Cerebral Palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 90, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketcheson, L.; Hauck, J.L.; Ulrich, D. The Levels of Physical Activity and Motor Skills in Young Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder, Aged 2–5 Years. Autism 2018, 22, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S.W.; Schreiber, M.; Lobo, M.; Pritchard, B.; George, L.; Galloway, J.C. Real-World Performance: Physical Activity, Play, and Object-Related Behaviors of Toddlers With and Without Disabilities. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Foster, C.; Lai, B.; McBride, C.B.; Ng, K.; Pratt, M.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Smith, B.; Vásquez, P.M.; et al. Participation of People Living with Disabilities in Physical Activity: A Global Perspective. Lancet 2021, 398, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Riley, B.; Wang, E.; Rauworth, A.; Jurkowski, J. Physical Activity Participation among Persons with Disabilities: Barriers and Facilitators. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounassalo, I.; Salin, K.; Kankaanpää, A.; Hirvensalo, M.; Palomäki, S.; Tolvanen, A.; Yang, X.; Tammelin, T.H. Distinct Trajectories of Physical Activity and Related Factors during the Life Course in the General Population: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. chpsy0114. ISBN 978-0-470-14765-8. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, P.G.; Bullock, C.C.; Gibb, Z.G.; Himler, H. Social-Ecological Influences on Interpersonal Support in People with Physical Disability. Disabil. Health J. 2015, 8, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Úbeda-Colomer, J.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Monforte, J.; Pérez-Samaniego, V.; Devís-Devís, J. Predicting Physical Activity in University Students with Disabilities: The Role of Social Ecological Barriers in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Healy, S.; Haegele, J.A. Environmental and Social Determinants of Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.; McGarty, A.M.; Melville, C.A.; Hughes-McCormack, L.A. Correlates of Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Caldwell, L.L.; Loy, S.; Robledo, M. A Qualitative Study of Latino Grandparents’ Involvement in and Support for Grandchildren’s Leisure Time Physical Activity. Health Educ. Behav. 2018, 45, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, S.; Lavis, A.; Potter, C.M.; Ulijaszek, S.; Nowicka, P.; Eli, K. How Active Can Preschoolers Be at Home? Parents’ and Grandparents’ Perceptions of Children’s Day-to-Day Activity, with Implications for Physical Activity Policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Besnilian, A.; Boyns, D. Latinx Mothers’ Perception of Grandparents’ Involvement in Children’s Physical Activity. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2022, 20, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, H. Grandparental Care and Childhood Obesity in China. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 17, 101003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulgaron, E.R.; Marchante, A.N.; Agosto, Y.; Lebron, C.N.; Delamater, A.M. Grandparent Involvement and Children’s Health Outcomes: The Current State of the Literature. Fam. Syst. Health 2016, 34, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ainsworth, A.; Caldwell, L. Grandparent(s) Coresidence and Physical Activity/Screen Time among Latino Children in the United States. Fam. Syst. Health 2021, 39, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duflos, M.; Lane, J.; Brussoni, M. Motivations and Challenges for Grandparent–Grandchild Outdoor Play in Early Childhood: Perception of Canadian Grandparents. Fam. Relat. 2024, 73, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M.I.; Crowley, K. Parent Beliefs about Teaching and Learning in a Children’s Museum. Visit. Stud. Today 2004, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.J.; Jago, R.; Sebire, S.J.; Kesten, J.M.; Pool, L.; Thompson, J.L. The Influence of Friends and Siblings on the Physical Activity and Screen Viewing Behaviours of Children Aged 5–6 Years: A Qualitative Analysis of Parent Interviews. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kracht, C.L.; Sisson, S.B. Sibling Influence on Children’s Objectively Measured Physical Activity: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontinck, C.; Warreyn, P.; Van der Paelt, S.; Demurie, E.; Roeyers, H. The Early Development of Infant Siblings of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Characteristics of Sibling Interactions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuskelly, M.; Gunn, P. Sibling Relationships of Children with Down Syndrome: Perspectives of Mothers, Fathers, and Siblings. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2003, 108, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazo, J.A.; Smith, A.L. A Systematic Review of Siblings and Physical Activity Experiences. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 122–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsdahl, A.B.; Moe-Nilssen, R.; Kaale, H.K.; Rieber, J.; Strand, L.I. Change in Basic Motor Abilities, Quality of Movement and Everyday Activities Following Intensive, Goal-Directed, Activity-Focused Physiotherapy in a Group Setting for Children with Cerebral Palsy. BMC Pediatr. 2010, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, C.V.A.; Ferreira, J.P.; Quinaud, R.T.; Silva, K.M.N.; Carvalho, H.M.; Gaspar, J.M. Exercise Improves the Social and Behavioral Skills of Children and Adolescent with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1027799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bania, T.; Dodd, K.J.; Taylor, N. Habitual Physical Activity Can Be Increased in People with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillo-Navarro, C.; Medina-Mirapeix, F.; Escolar-Reina, P.; Montilla-Herrador, J.; Gomez-Arnaldos, F.; Oliveira-Sousa, S.L. Parents of Children with Physical Disabilities Perceive That Characteristics of Home Exercise Programs and Physiotherapists’ Teaching Styles Influence Adherence: A Qualitative Study. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginis, K.A.M.; Ma, J.K.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Rimmer, J.H. A Systematic Review of Review Articles Addressing Factors Related to Physical Activity Participation among Children and Adults with Physical Disabilities. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-Y.; Turnbull, H.R. Taiwan’s National Policies for Children in Special Education: Comparison with UNCRPD, Core Concepts, and the American IDEA: Taiwan Special Education. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 11, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.-Y.; Witten, K.; Carroll, P.; Romeo, J.S.; Donnellan, N.; Smith, M. The Relationship between Children’s Third-Place Play, Parental Neighbourhood Perceptions, and Children’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Child. Geogr. 2023, 21, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (n = 5286) | PAP (n = 2556) | No PAP (n = 2730) | χ2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (%) | 3 years (n = 625) | 11.83 | 23.96 | 76.04 | 1431.63 | <0.001 |

| 4 years (n = 4659) | 88.17 | 51.64 | 48.36 | |||

| Child sex (%) | Boys (n = 3335) | 63.11 | 58.18 | 41.82 | 140.42 | <0.001 |

| Girls (n = 1949) | 36.89 | 31.55 | 68.45 | |||

| Disability level (%) | Severe (n = 3839) | 72.63 | 42.54 | 57.46 | 117.34 | <0.001 |

| Mild (n = 1446) | 27.37 | 63.83 | 36.17 | |||

| Disability type (%) | ASD (n = 421) | 7.96 | 62.23 | 37.77 | 1641.98 | <0.001 |

| Cerebral palsy (n = 1865) | 35.28 | 47.29 | 52.71 | |||

| ID (n = 814) | 15.40 | 100 | 0 | |||

| Language Disorder (n = 1315) | 24.88 | 43.50 | 56.50 | |||

| Hearing impairment (n = 646) | 12.22 | 0 | 100.00 | |||

| Others (n = 225) | 4.26 | 11.56 | 88.44 | |||

| Monthly income (KRW 10,000; %) | 150–299 (n = 1641) | 27.44 | 64.96 | 35.04 | 2017.66 | <0.001 |

| 300–400 (n = 2269) | 42.94 | 23.62 | 76.38 | |||

| 401–600 (n = 1090) | 20.62 | 87.43 | 12.57 | |||

| >601 (n = 285) | 9.00 | 0 | 100.00 | |||

| PA frequency (%) | Two times/week | More than three times/week | Almost everyday | |||||

| 33.0 | 43.60 | 22.60 | ||||||

| PA minutes | Mean | Median | ||||||

| 34.78 | 30.00 | |||||||

| PA places (%) | Home | Outside | Private PA center | Public PA center | Disability PA center | Others | ||

| 38.99 | 14.26 | 10.80 | 15.58 | 18.54 | 1.83 | |||

| PA types (%) | Walking | Stretching | Balance activity | Bicycling or tricycling | Swimming | Others | ||

| 14.26 | 25.94 | 32.55 | 15.58 | 6.76 | 4.92 | |||

| Economic Issue | No Time | Lack of Disability Programs | Lack of Professionals Knowledgeable About Disabilities | Lack of Information | No Community-Based PA Center | PA Is Not Priority | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.97 | 3.83 | 24.46 | 28.78 | 9.91 | 5.00 | 19.75 | 6.31 |

| All (n = 5286; %) | PAP (n = 2556; %) | No PAP (n = 2730; %) | χ2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal level | ||||||

| Brothers and sisters | Yes | 46.06 | 63.48 | 35.46 | 414.19 | <0.001 |

| No | 53.94 | 36.52 | 64.54 | |||

| Grandparents | Yes | 11.17 | 7.97 | 92.03 | 3728.21 | <0.001 |

| No | 88.83 | 46.56 | 53.44 | |||

| Organizational level | ||||||

| Physical therapy | Yes | 35.28 | 47.29 | 52.71 | 15.24 | <0.001 |

| No | 64.72 | 48.95 | 51.05 | |||

| Pre-kindergarten | Yes | 37.36 | 56.94 | 43.06 | 100.71 | <0.001 |

| No | 62.64 | 43.25 | 56.75 | |||

| Environmental level | ||||||

| Living area | Rural | 51.57 | 52.90 | 47.10 | 17.46 | <0.001 |

| Urban | 48.43 | 43.53 | 56.47 | |||

| Government support | High | 42.64 | 54.33 | 45.67 | 39.30 | <0.001 |

| Low | 57.36 | 43.91 | 56.09 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sung, M.-C.; Mahmoudkhani, M.; Ku, B. The Socio-Ecological Factors of Physical Activity Participation in Preschool-Aged Children with Disabilities. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091081

Sung M-C, Mahmoudkhani M, Ku B. The Socio-Ecological Factors of Physical Activity Participation in Preschool-Aged Children with Disabilities. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091081

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Ming-Chih, Mohammadreza Mahmoudkhani, and Byungmo Ku. 2025. "The Socio-Ecological Factors of Physical Activity Participation in Preschool-Aged Children with Disabilities" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091081

APA StyleSung, M.-C., Mahmoudkhani, M., & Ku, B. (2025). The Socio-Ecological Factors of Physical Activity Participation in Preschool-Aged Children with Disabilities. Healthcare, 13(9), 1081. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091081