Family-Centered Care in Adolescent Intensive Outpatient Mental Health Treatment in the United States: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Collection

3. Isabella’s Case

4. Family-Centered Medication Management

5. Family Engagement in Isabella’s Medication Management and Outpatient Service Connection

6. Individualized Case Management, Parental Education, and Peer Support Program

7. The Impacts of Case Management, Education, and Peer Support for Isabella’s Parents

8. Measurement-Based Care: Family Assessment and Feedback Session

9. MBC Provides Individualized Assessment and Care for Isabella and Her Family

10. DBT with Multi-Family Skill Groups

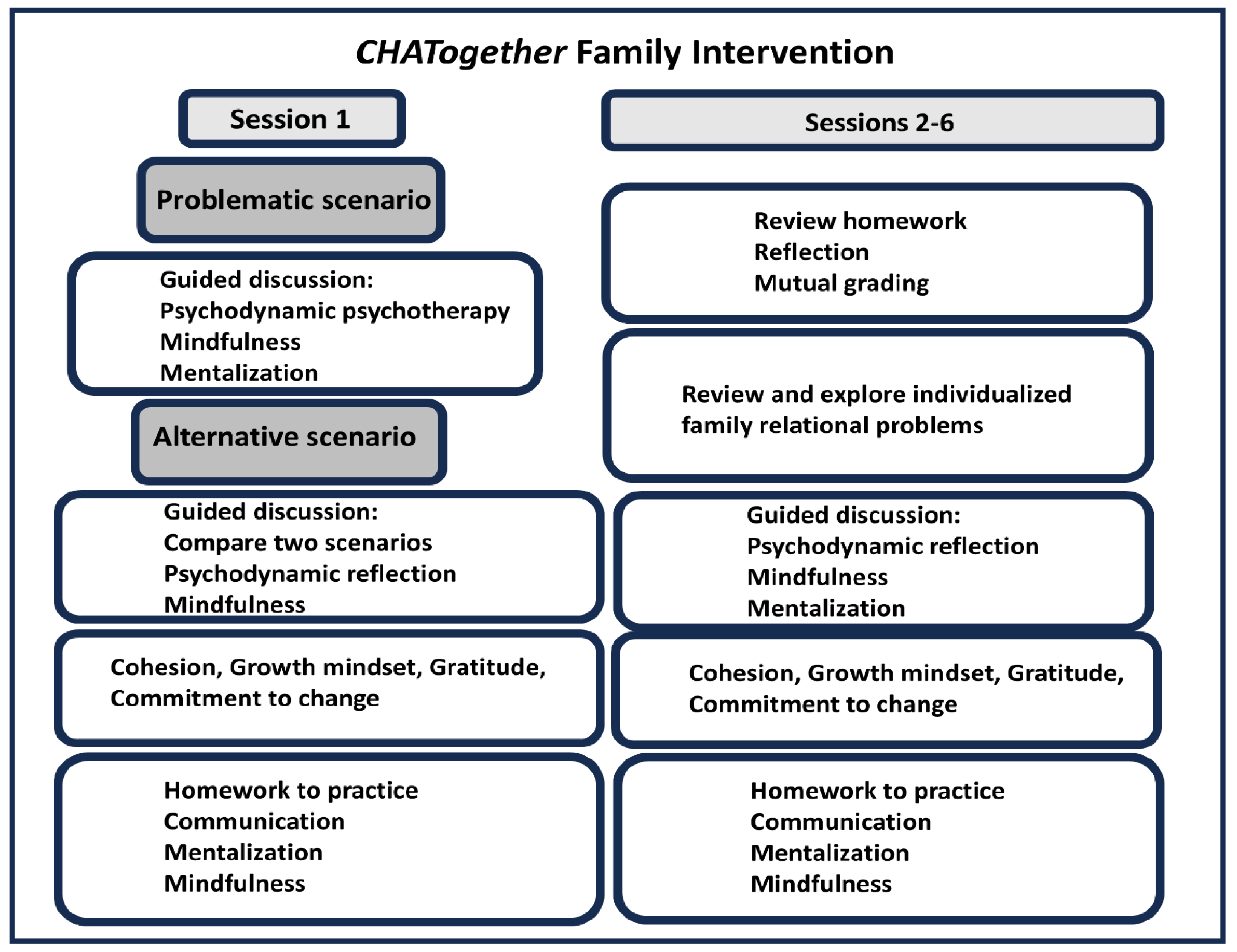

11. Isabella and Family Participate in DBT Multi-Family Skill Groups

12. CHATogether: Individualized Family Intervention

13. CHATogether Teaches Isabella and Her Family to Mentalize

14. Limitations

15. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haine-Schlagel, R.; Walsh, N.E. A review of parent participation engagement in child and family mental health treatment. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 18, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero-Ferreiro, V.; Izquierdo-Izquierdo, M.; Rodríguez, V.; Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Lahera, G.; Santos, J.L.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. Dramatic increase of suicidality in children and adolescents after COVID-19 pandemic start: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 163, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, M.; Zhou, S.J.; Guo, Z.C.; Zhang, L.G.; Min, H.J.; Li, X.M.; Chen, J.X. The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassinat, J.R.; Whiteman, S.D.; Serang, S.; Dotterer, A.M.; Mustillo, S.A.; Maggs, J.L.; Kelly, B.C. Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1597–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yard, E.F.; Radhakrishnan, L.; Ballesteros, M.F.; Sheppard, M.; Gates, A.; Stein, Z.; Hartnett, K.; Kite-Powell, A.; Rodgers, L.; Adjemian, J.; et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, I.H.; Miller, J.G.; Borchers, L.R.; Coury, S.M.; Costello, L.A.; Garcia, J.M.; Ho, T.C. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and brain maturation in adolescents: Implications for analyzing longitudinal data. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2023, 3, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, A.; Martin, G.; de Looze, M.E.; Walsh, S.D.; Paakkari, L.; Bilz, L.; Gobina, I.; Page, N.; Hulbert, S.; Inchley, J. Cross-national trends in adolescents psychological and somatic complaints before and after the onset of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 76, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.D.; Lee, B.R.; Daleiden, E.L.; Lindsey, M.; Brandt, N.E.; Chorpita, B.F. The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickerby, M.L.; DerMarderosian, D.; Nassau, J.; Houck, C. Family-based integrated care (FBIC) in a partial hospital program for complex pediatric illness: Fostering shifts in family illness beliefs and relationships. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2017, 26, 733–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickerby, M.L.; Roesler, T.A. Training Child Psychiatrists in Family-Based Integrated Care. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, J.E.; Reivich, K.J.; Freres, D.R.; Chaplin, T.M.; Shatté, A.J.; Samuels, B.; Elkon, A.G.L.; Litzinger, S.; Lascher, M.; Gallop, R. School-based prevention of depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and specificity of the Penn Resiliency Program. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillham, J.E.; Reivich, K.J.; Freres, D.R.; Lascher, M.; Litzinger, S.; Shatté, A.; Seligman, M.E.P. School-based prevention of depression and anxiety symptoms in early adolescence: A pilot of a parent intervention component. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2006, 21, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, J.M.; D’Angelo, E.J. Implementing Evidence-Based Treatments for Youth in Acute and Intensive Treatment Settings. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2020, 34, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenson, M.P.; Gurtovenko, K.; Simmons, S.W.; Thompson, A.D. Systematic Review: Patient Outcomes in Transdiagnostic Adolescent Partial Hospitalization Programs. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookman, C.; Nunes, J.C.; Ngo, N.T.; Kunstler Twickler, N.; Smith, T.; Lekwauwa, R.; Yuen, E.Y. Novel CHATogether family-centered mental health care in the post-pandemic era: A pilot case and evaluation. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Ngo, N.T.; Vigneron, J.G.; Lee, A.; Sust, S.; Martin, A.; Yuen, E.Y. CHATogether: A novel digital program to promote Asian American Pacific Islander mental health in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selph, S.S.; McDonagh, M.S. Depression in Children and Adolescents: Evaluation and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 609–617. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, R.A.; Reynolds, C.R.; Kamphaus, R.W.; Vannest, K.J. BASC-3. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Kreutzer, J., DeLuca, J., Caplan, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rathus, J.H.; Wagner, D.; Miller, A.L. Psychometric evaluation of the life problems inventory, a measure of borderline personality features in adolescents. J. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.; Rathus, J.H.; Miller, A.L. Reliability and Validity of the Life Problems Inventory, A Self-Report Measure of Borderline Personality Features, in a College Student Sample. J. Psychol. Psychother. 2015, 5, 1000199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E.; Stucky, B.; Langer, M.M.; Thissen, D.; DeWitt, E.M.; Lai, J.-S.; Varni, J.W.; Yeatts, K.; DeWalt, D.A. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, R.J.; Foster, S.; Kent, R.N.; O’Leary, K.D. Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1979, 12, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy, K.; Rush, A.J.; Slater, H.; Mayes, T.L.; Minhajuddin, A.; Jha, M.; Blader, J.C.; Brown, R.; Emslie, G.; Fuselier, M.N.; et al. Psychometric evaluation of the 9-item Concise Health Risk Tracking—Self-Report (CHRT-SR(9)) (a measure of suicidal risk) in adolescent psychiatric outpatients in the Texas Youth Depression and Suicide Research Network (TX-YDSRN). J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 329, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeelk-Cone, K.; Petrova, M.; Wyman, P.A. Three scales assessing high school students’ attitudes and perceived norms about seeking adult help for distress and suicide concerns. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2012, 42, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubb, C.; Foran, H. Online Health Information Seeking by Parents for Their Children: Systematic Review and Agenda for Further Research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaman, C.R.; Ibrahim, N.; Shaker, V.; Cham, C.Q.; Ho, M.C.; Visvalingam, U.; Shahabuddin, F.A.; Abd Rahman, F.N.; A Halim, M.R.; Kaur, M.; et al. Parental Factors Associated with Child or Adolescent Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgcomb, J.B.; Zima, B. Medication Adherence Among Children and Adolescents with Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, A.; Vajda, J.; Llamocca, E.N.; Campo, J.V.; Gorham, T.J.; Lin, S.; Fontanella, C.A. Factors associated with psychiatric readmission of children and adolescents in the U.S.: A systematic review of the literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, E.V.; Fawley-King, K.; Garland, A.F.; Aarons, G.A. Do aftercare mental health services reduce risk of psychiatric rehospitalization for children? Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Crickard, E.; Lee, J.; Holmes, C. Attitudes and experience of youth and their parents with psychiatric medication and relationship to self-reported adherence. Community Ment. Health J. 2013, 49, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, D.; Egedy, M.; Frappier, J.Y. Adherence to treatment in adolescents. Pediatr. Child Health 2008, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, E.; Woods, S.W.; Rosenheck, R.A. Effects of ethnicity on psychotropic medications adherence. Community Ment. Health J. 2005, 41, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancher, T.L.; Lee, D.; Cheng, J.K.Y.; Yang, M.S.; Yang, L. Interventions to improve adherence to psychotropic medication in clients of Asian descent: A systematic review. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2014, 5, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon, G. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. In Parents Under Pressure: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Mental Health & Well-Being of Parents; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Figlie, N.B.; Caverni, J.L.T. The Application of Motivational Interviewing to the Treatment of Substance Use Disorder. In Psychology of Substance Abuse: Psychotherapy, Clinical Management and Social Intervention; Andrade, A.L.M., De Micheli, D., Aparecida da Silva, E., Lopes, F.M., Pinheiro, B.D.O., Reichert., R.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, J.; Dean, J.; Ward, J.; Komashie, A.; Bashford, T. A systems approach to healthcare: From thinking to practice. Future Health J. 2018, 5, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, E.S.; Laird, R.D. Family support programs and adolescent mental health: Review of evidence. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2014, 5, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, A.W.; Connors, E.H. A roadmap for measurement-based care implementation in intensive outpatient treatment settings for children and adolescents. Evid. Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 7, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, S.G.; Hoff, R.A. Observations from the national implementation of Measurement Based Care in Mental Health in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Psychol. Serv. 2020, 17, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Doss, A.; Douglas, S.; Phillips, D.A.; Gencdur, O.; Zalman, A.; Gomez, N.E. Measurement-based care as a practice improvement tool: Clinical and organizational applications in youth mental health. Evid. Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 5, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, H.E.; Ronan, K. The application of a feedback-informed approach in psychological service with youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 55, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.; Fristad, M.A.; Axelson, D.; Krishna, R. Evidence base for measurement-based care in child and adolescent psychiatry. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2020, 29, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; Lewis, C.C. Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2015, 22, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; Pullmann, M.D.; Dorsey, S.; Martin, P.; Grigore, A.A.; Becker, E.M.; Jensen-Doss, A. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Current Assessment Practice Evaluation-Revised (CAPER) in a national sample. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 46, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmyre, E.D.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; López, R.; Goldberg, D.G.; Liu, F.; Defayette, A.B. Implementation of Measurement-Based Care in Mental Health Service Settings for Youth: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 27, 909–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M.M. DBT® Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.L.; Rathus, J.H.; Linehan, M.M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Suicidal Adolescents; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti, A.E.; Shenk, C. Fostering validating responses infamilies. Soc. Work. Ment. Health 2008, 6, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, R.; Houghton, S.; O’Driscoll Lawrie, C.; Dowling, C.; O’Hanrahan, K.; Devoy, S. A multifamily group for adolescents with emotion regulation difficulties: Adolescent, parent and clinician experiences. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2024, 24, 982–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Hunt, K.; Parker, S.; Camp, J.; Stewart, C.; Morris, A. Parent and Carer Skills Groups in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for High-Risk Adolescents with Severe Emotion Dysregulation: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Participants’ Outcomes and Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, D.; Gillespie, C.; Joyce, M.; Spillane, A. An evaluation of the skills group component of DBT-A for parent/guardians: A mixed methods study. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 40, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hoq, R.; Shaligram, D.; Kramer, D.A. Family Psychiatry: A potential solution to the workforce problem. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry News 2023, 54, 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzmann, L.; Target, M.; Hewison, D.; Casey, P.; Fearon, P.; Lassri, D. Mentalization-based therapy for parents in entrenched conflict: A random allocation feasibility study. Psychotherapy 2016, 53, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzmann, L.; Abse, S.; Target, M.; Glausius, K.; Nyberg, V.; Lassri, D. Mentalisation-based therapy for parental conflict—Parenting together; an intervention for parents in entrenched post-separation disputes. Psychoanal. Psychother. 2017, 31, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, N.; Mortimer, R.; Cirasola, A.; Batra, P.; Kennedy, E. The evidence-base for psychodynamic psychotherapy with children and adolescents: A narrative synthesis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 662671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boal, A. Theatre of the Oppressed; Theatre Communications Group: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rohd, M. Theatre for Community Conflict and Dialogue: The Hope Is Vital Training Manual; Heinemann Press: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meersand, P.; Gilmore, K.J. Play Therapy: A Psychodynamic Primer for the Treatment of Young Children; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Close, N. Diagnostic play interview: Its role in comprehensive psychiatric evaluation. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 8, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.A. History of family psychiatry: From the social reform era to the primate social organ system. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Sargent, J. Overview of the evidence base for family interventions in child psychiatry. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, B.L. The biobehavioral family model and the family relational assessment protocol: Map and GPS for family systems training. Fam Process 2023, 62, 1322–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberg, N.T. Activating mentalization in parents: An integrative framework. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2015, 14, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, G.; Murphy, S.; Connon, G. Mentalization-based treatments with children and families: A systematic review of the literature. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1022–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, A.; Sleed, M. Parental Reflective Functioning on the Parent Development Interview: A narrative review of measurement, association, and future directions. Infant Ment. Health J. 2024, 45, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostad, W.; Whitaker, D. The Association Between Reflective Functioning and Parent–Child Relationship Quality. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2164–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Fleming, S. A Brief History of Aaron T. Beck, MD, and Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2021, 3, e6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilio, F.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Couples and Families: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf, V.; Szabó, M.; Abbott, M.J. The effect of mindfulness interventions for parents on parenting stress and youth psychological outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garro, A.; Janal, M.; Kondroski, K.; Stillo, G.; Vega, V. Mindfulness initiatives for students, teachers, and parents: A review of literature and implications for practice during COVID-19 and beyond. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 27, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Fam. Process. 2020, 59, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadmawaty, A.; Wasludin, W. The effect of the belief system, family organizations and family communication on COVID-19 prevention behavior: The perspective of family resilience. Int. J. Disaster Manag. 2021, 4, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madakasira, S. Psychiatric partial hospitalization programs: What you need to know. Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 21, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Sheikh-Khalil, S. Does Parental Involvement Matter for Student Achievement and Mental Health in High School? Child Dev. 2014, 85, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Raising Kids and Running a Household: How Working Parents Share the Load. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/11/04/raising-kids-and-running-a-household-how-working-parents-share-the-load/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Mikolai, J.; Perelli-Harris, B.; Berrington, A. The role of education in the intersection of partnership transitions and motherhood in Europe and the United States. Demogr. Res. 2018, 39, 753–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.; Burroway, R. Targeting, Universalism, and Single-Mother Poverty: A Multilevel Analysis Across 18 Affluent Democracies. Demography 2012, 49, 719–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isabella | Parents | |

| Demographic | ||

| Age | 15 | |

| Gender | Female | |

| Living arrangement | Both parents | |

| Program participation | Both parents | |

| Parental status | Married | |

| Program attendance format | In-person | In-person and virtual |

| Diagnosis | Major Depressive Disorder PHQ-9: 16 | N/A |

| Referral sources | Psychiatric inpatient | N/A |

| Admission medications | Abilify 2 mg daily Intuniv 2 mg daily | N/A |

| Admission psychological measures | ||

| BASC-3 | Clinical Scales: | Clinical Scales: |

| Social Stress (76) | * None when compared to a clinical population. | |

| Depression (72) | ||

| Locus of Control (71) | ||

| Hyperactivity (71) | ||

| Attitude to School (69) | ||

| Attitude to Teachers (69) | ||

| Sense of Inadequacy (68) | ||

| Somatization (64) | ||

| Attention Problems (64) | ||

| Atypicality (62) | ||

| Anxiety (61) | ||

| Adaptive Scales: | Adaptive Scales: | |

| Relations with Parents (31) | * None when compared to a clinical population. | |

| Interpersonal Relations (32) | ||

| LPI | 51 | N/A |

| Week | Session Topic | Goals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CHATogether parenting session | Promote parents’ understanding of communication skills and introduce a mentalization-based approach |

| 2 | Psychiatric Crisis Management | Educating parents on identifying and responding to psychiatric crises, especially regarding ensuring child safety; reducing isolation and shame among parents to demonstrate commonality of youth who experience mental health crises |

| 3 | Talk with a Doc: Q&A on Psychiatric medication and diagnosis | Psychoeducation on psychiatric medications and mental health diagnosis; normalization of physician-parent conversations regarding mental health; encouraging trust in medical providers among parents of children with psychiatric concerns |

| 4 | Motivational Interviewing for Parents: Using OARS for success | Skills training for parents on responding effectively to their child’s needs using motivational interviewing techniques of Open-Ended Questions, Affirmations, Reflections, and Summaries |

| 5 | Anger Management | Psychoeducation on anger and anger management techniques with accompanying skills demonstrations to assist parents in maintaining emotional regulation and model skills that they may demonstrate to encourage in their child |

| 6 | Mindfulness Meditation and Grounding Techniques | Psychoeducation on mindfulness and grounding techniques with accompanying skills demonstrations to assist parents in maintaining emotional regulation and model skills that they may demonstrate to encourage in their child |

| Measures (n = 26) | % of Strongly Agree or Agree |

|---|---|

| 1. Overall, I find this parent peers support group helpful for my needs | 100% |

| 2. The parent support group fits well with the existing adolescent IOP | 100% |

| 3. The parent peer support group is convenient for me as a parent to participate. | 96% |

| 4. I support the future development of parent peer support groups and recommend this service to others who may benefit from this. | 100% |

| 5. What are some other topics you would like to include in the future? | Communication with teens about substance use Teen’s self-diagnosis on internet Skills for parents to navigate limit setting Discuss safety plan in psychiatric crisis |

| Measures (n = 1 from Isabella’s Case) | Isabella | Mother | Father | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| PROMIS-depression (Raw/T-score) | 40/61.1 | 23/47.6 | 28/60.3 | 22/53.5 | 27/59.2 | 11/32.1 |

| PROMIS-anxiety (Raw/T-score) | 38/63.1 | 19/45.7 | 25/60.4 | 16/45.1 | 29/64.8 | 13/38.6 |

| CBQ (sum/max) | 11/20 | 1/20 | 13/20 | 4/20 | 13/20 | 4/20 |

CHRT-SR9 (sum/max)

| 18/36 6/8 6/8 6/8 0/12 | 0/36 0/8 0/8 0/8 0/12 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Help-seeking attitude from adults in distress and suicide concerns (sum/max) 1. Help-seeking acceptability from parents 2. Adult help for suicidal youth 3. Reject codes of silence | 23/36 4/12 9/12 10/12 | 36/36 12/12 12/12 12/12 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kietzman, H.W.; Styles, W.L.; Franklin-Zitzkat, L.; Del Vecchio Valerian, M.; Yuen, E.Y. Family-Centered Care in Adolescent Intensive Outpatient Mental Health Treatment in the United States: A Case Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091079

Kietzman HW, Styles WL, Franklin-Zitzkat L, Del Vecchio Valerian M, Yuen EY. Family-Centered Care in Adolescent Intensive Outpatient Mental Health Treatment in the United States: A Case Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091079

Chicago/Turabian StyleKietzman, Henry W., Willem L. Styles, Liese Franklin-Zitzkat, Maria Del Vecchio Valerian, and Eunice Y. Yuen. 2025. "Family-Centered Care in Adolescent Intensive Outpatient Mental Health Treatment in the United States: A Case Study" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091079

APA StyleKietzman, H. W., Styles, W. L., Franklin-Zitzkat, L., Del Vecchio Valerian, M., & Yuen, E. Y. (2025). Family-Centered Care in Adolescent Intensive Outpatient Mental Health Treatment in the United States: A Case Study. Healthcare, 13(9), 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091079