Interconnected Challenges: Examining the Impact of Poverty, Disability, and Mental Health on Refugees and Host Communities in Northern Mozambique

Abstract

1. Introduction

Poverty and Displacement in Mozambique

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Aims

2.2. Survey Data

2.3. Enumerator Training and Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Demographics

3.2. Anxiety

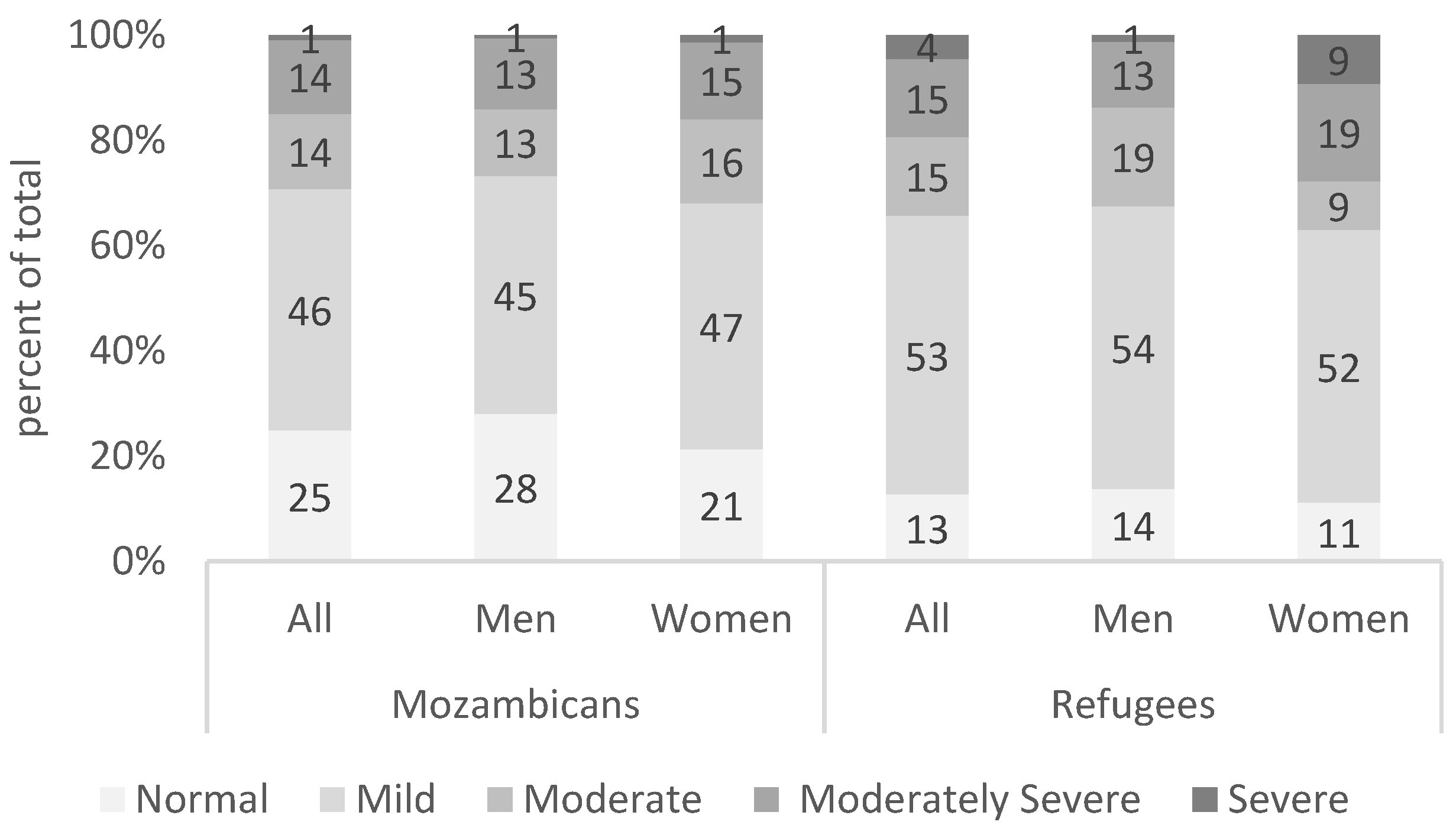

3.3. Depression

3.4. Self-Esteem

3.5. Loneliness

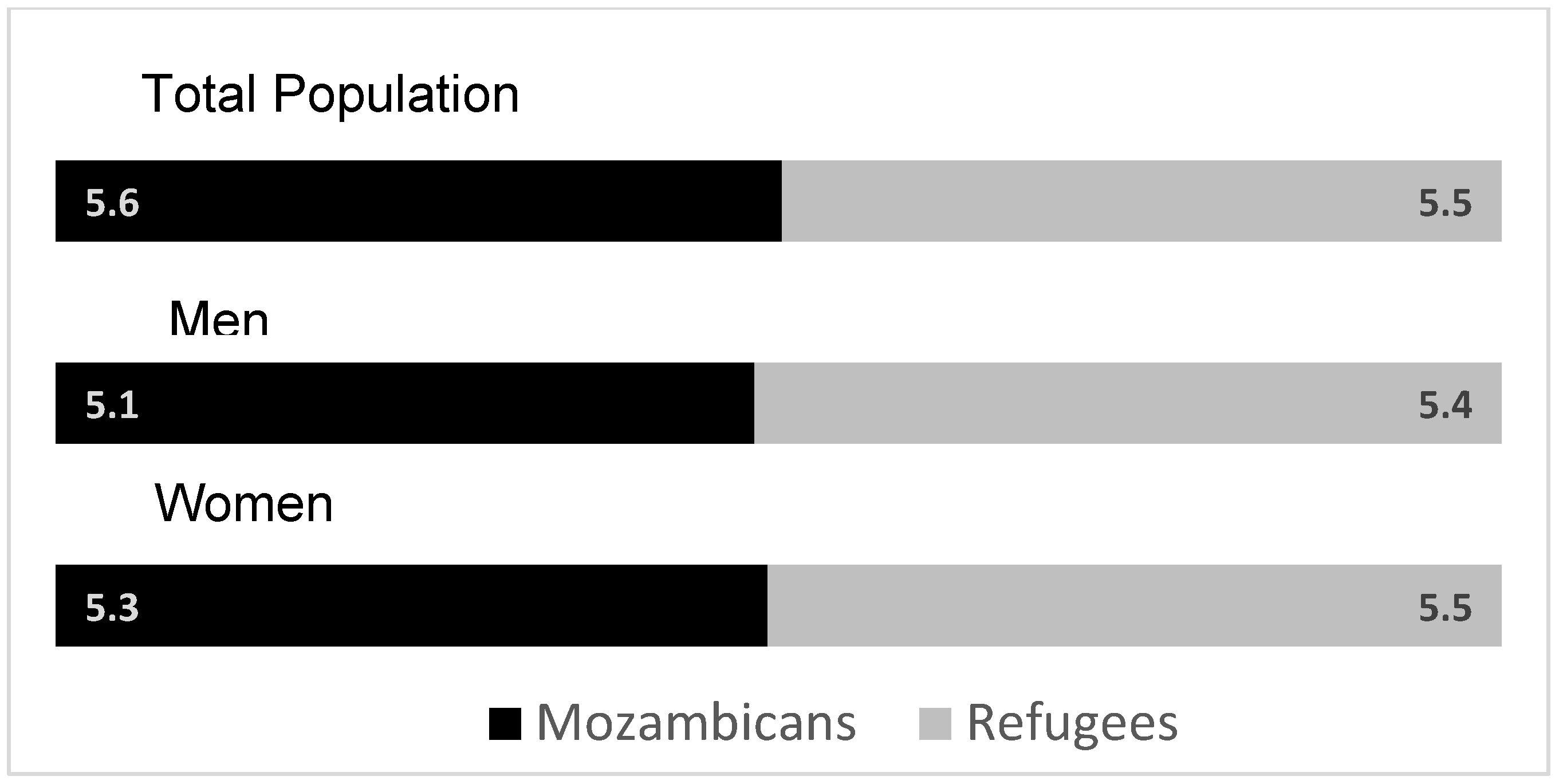

3.6. Pessimism Bias

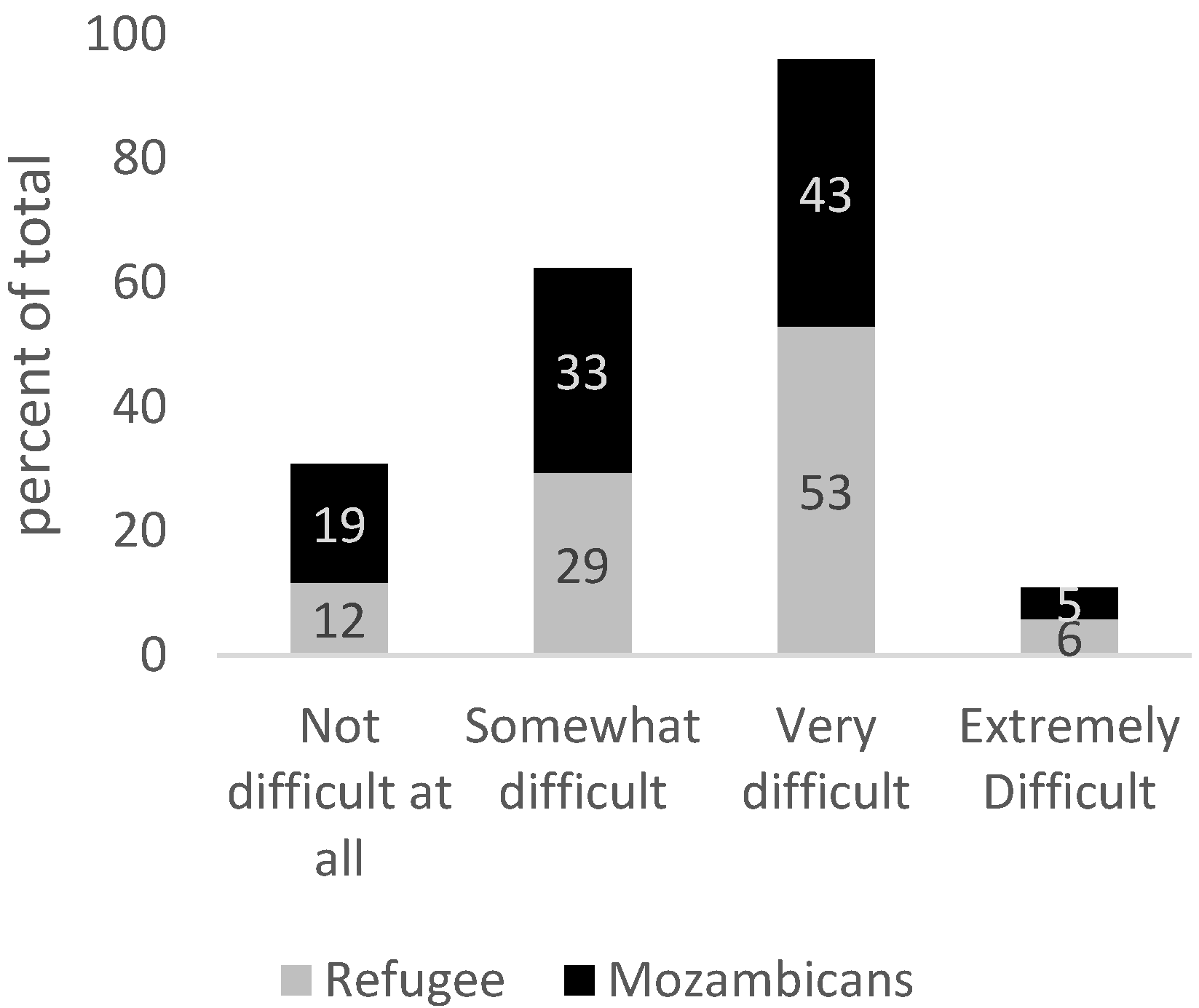

3.7. Financial Security

3.8. Disability

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Lund, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Baingana, F.; Bolton, P.; Chisholm, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Cooper, J.L.; Eaton, J.; et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 2018, 392, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.; Bombana, M.; Heinzel-Gutenbrenner, M.; Kleindienst, N.; Bohus, M.; Lyssenko, L.; Vonderlin, R. Socio-economic consequences of mental distress: Quantifying the impact of self-reported mental distress on the days of incapacity to work and medical costs in a two-year period: A longitudinal study in Germany. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettner, S.L.; Frank, R.G.; Kessler, R.C. The Impact of Psychiatric Disorders on Labor Market Outcomes. Ind. Labor. Relat. Rev. 1997, 51, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, N.; Akhtar, A.; Barth, J.; Schnyder, U. Psychiatric Disorders in Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons After Forced Displacement: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.A.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Harris, N.B.; Danese, A.; Samara, M. Toxic Stress and PTSD in Children: Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ 2020, 371, m3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, F.; van Ommeren, M.; Flaxman, A.; Cornett, J.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 2019, 394, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atamanov, A.; Beltramo, T.; Reese, B.C.; Rios Rivera, L.A.; Waita, P. One Year in the Pandemic: Results from the High-Frequency Phone Surveys for Refugees in Uganda; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Silove, D.; Ventevogel, P.; Rees, S. The contemporary refugee crisis: An overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klabbers, R.E.; Ashaba, S.; Stern, J.; Faustin, Z.; Tsai, A.C.; Kasozi, J.; Kambugu, A.; Ventevogel, P.; Bassett, I.V.; O’Laughlin, K.N. Mental disorders and lack of social support among refugees and Ugandan nationals screening for HIV at health centers in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in southwestern Uganda. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2022, 6, e2022053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.; Mugera, H.; Tabasso, D.; Lazić, M.; Gillsäter, B. Answering the Call: Forcibly Displaced During the Pandemic; Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2024; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2024 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Ridley, M.; Rao, G.; Schilbach, F.; Patel, V. Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms. Science 2020, 370, eaay0214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.; Breen, A.; Flisher, A.J.; Kakuma, R.; Corrigall, J.; Joska, J.A.; Swartz, L.; Patel, V. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, J.; Afifi, T.O.; McMillan, K.A.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Relationship Between Household Income and Mental Disorders: Findings from a Population-Based Longitudinal Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, E.J.; Wetherell, J.L. A lifespan view of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasquilho, D.; Matos, M.G.; Salonna, F.; Guerreiro, D.; Storti, C.C.; Gaspar, T.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: A systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Due, C.; Ziersch, A. The relationship between employment and health for people from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds: A systematic review of quantitative studies. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 18, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. UNHCR 2023 Global Compact on Refugees Indicator Report; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/reports-and-publications/data-and-statistics/indicator-report-2023 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Hoogevan, J.; Obi, C. A Triple Win: Fiscal and Welfare Benefits of Economic Participation by Syrian Refugees in Jordan; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/41574 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Beltramo, T.P.; Calvi, R.; De Giorgi, G.; Sarr, I. Child poverty among refugees. World Dev. 2023, 171, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunes, A.; Flanders, W.D.; Augestad, L.B. Physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults with and without visual impairments: The HUNT Study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 13, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinals, D.A.; Hovermale, L.; Mauch, D.; Anacker, L. Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in the Mental Health System: Part 1. Clinical Considerations. Psychiatr. Serv. 2022, 73, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Di Gessa, G. Mental health and social interactions of older people with physical disabilities in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e365–e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.-W.; Kwon, Y.D.; Park, J.; Oh, I.-H.; Kim, J. Relationship between Physical Disability and Depression by Gender: A Panel Regression Model. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, R.A. Frequent Mental Distress Among Adults, by Disability Status, Disability Type, and Selected Characteristics—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Kamalyan, L.; Abubaker, D.; Alheresh, R.; Al-Rousan, T. Self-reported Disability Among Recently Resettled Refugees in the United States: Results from the National Annual Survey of Refugees. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2024, 26, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. Thematic Note–Vision Challenges for Refugees and Host Communities in Kenya. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/thematic-note-vision-challenges-refugees-and-host-communities-kenya (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Jeste, D.V.; Lee, E.E.; Cacioppo, S. Battling the Modern Behavioral Epidemic of Loneliness: Suggestions for Research and Interventions. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 553–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L.A. Personal Relationships in Disorder. In Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness; Duck, S.W., Gilmour, R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Eglit, G.M.L.; Palmer, B.W.; Martin, A.S.; Tu, X.; Jeste, D.V. Loneliness in schizophrenia: Construct clarification, measurement, and clinical relevance. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.A.; Carey, B.E.; McBride, C.; Bagby, R.M.; DeYoung, C.G.; Quilty, L.C. Big Five aspects of personality interact to predict depression. J. Personal. 2018, 86, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, C.; Elovainio, M.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Jokela, M. Personality and Depressive Symptoms: Individual Participant Meta-Analysis of 10 Cohort Studies. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, F.; Feizi, A.; Afshar, H.; Hassanzadeh Keshteli, A.; Adibi, P. How Five-Factor Personality Traits Affect Psychological Distress and Depression? Results from a Large Population-Based Study. Psychol. Stud. 2019, 64, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, D.; Pieper, L.; Klotsche, J.; Hoyer, J. Predictions get tougher in older individuals: A longitudinal study of optimism, pessimism and depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhu, J.; Veijola, J.; Hintsanen, M. The bidirectional relationships of optimism and pessimism with depressive symptoms in adulthood–A 15-year follow-up study from Northern Finland Birth Cohorts. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H.; Kronström, K.; Nabi, H.; Oksanen, T.; Salo, P.; Virtanen, M.; Suominen, S.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Low Level of Optimism Predicts Initiation of Psychotherapy for Depression: Results from the Finnish Public Sector Study. Psychother. Psychosom. 2011, 80, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, F.A.R.; de Oliveira, S.B.; Junior, A.G.; da Silva Pedroso, J. Association between the dispositional optimism and depression in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psicol. Reflexão E Crítica 2021, 34, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, S.E.; Rius-Ottenheim, N.; Schulte-van Maaren, Y.W.M.; Carlier, I.V.E.; Middelkoop, V.D.; Zitman, F.G.; Spinhoven, P.; Holmes, E.A.; Giltay, E.J. Optimism and mental imagery: A possible cognitive marker to promote well-being? Psychiatry Res. 2013, 206, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiovelli, G.; Michalopulos, S.; Papaioannou, E.; Sequeira, S. Forced Displacement and Human Capital: Evidence from Separated Siblings; Discussion Papers; CEPR, Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR Country–Mozambique. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/moz (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Goldberg, N.; Karlan, D.; Osei, R.; Parienté, W.; Shapiro, J.; Thuysbaert, B.; Udry, C. A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries. Science 2015, 348, 1260799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequiera, S.; Beltramo, T.; Nimoh, F.; O’Brien, M. Financial Security, Climate Shock and Social Cohesion. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19296. 2024. Available online: https://cepr.org/publications/dp19296 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Schreiner, M. Simple Poverty Scorecard® Poverty-Assessment Tool Mozambique. 2017. Available online: https://www.simplepovertyscorecard.com/MOZ_2014_ENG.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbe, V.F.J.; Muanido, A.; Manaca, M.N.; Fumo, H.; Chiruca, P.; Hicks, L.; De Jesus Mari, J.; Wagenaar, B.H. Validity and item response theory properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for primary care depression screening in Mozambique (PHQ-9-MZ). BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Marotta, C.; Ramirez, L.; Cardoso, H.; Alamo, C.; Cinturao, V.; Bavaro, D.F.; Mahotas, D.C.; Lazzari, M.; Fernando, C.; et al. High Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders in Adolescents and Youth Living with HIV: An Observational Study from Eight Health Services in Sofala Province, Mozambique. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2022, 36, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K.; Efraime, B. Suicidal behaviour, depression and generalized anxiety and associated factors among female and male adolescents in Mozambique in 2022–2023. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovero, K.L.; Dos Santos, P.F.; Adam, S.; Bila, C.; Fernandes, M.E.; Kann, B.; Rodrigues, T.; Jumbe, A.M.; Duarte, C.S.; Beidas, R.S.; et al. Leveraging Stakeholder Engagement and Virtual Environments to Develop a Strategy for Implementation of Adolescent Depression Services Integrated Within Primary Care Clinics of Mozambique. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 876062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyongesa, M.K.; Nasambu, C.; Mapenzi, R.; Koot, H.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Newton, C.R.J.C.; Abubakar, A. Psychosocial and mental health challenges faced by emerging adults living with HIV and support systems aiding their positive coping: A qualitative study from the Kenyan coast. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwita, M.; Shemdoe, E.; Mwampashe, E.; Gunda, D.; Mmbaga, B. Generalized anxiety symptoms among women attending antenatal clinic in Mwanza Tanzania; a cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Oxford, UK, 1965; ISBN 978-0-691-09335-2. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Sloman, A.; Margaretha, M. The Washington Group Short Set of Questions on Disability in Disaster Risk Reduction and humanitarian action: Lessons from practice. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, I.T.; Henneh, I.T.; Aluko, O.M.; Yawson, E.O.; Fokoua, A.R.; Koomson, A.; Torbi, J.; Olorunnado, S.E.; Lewu, F.S.; Yusha’u, Y.; et al. Depression in Sub-Saharan Africa. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 12, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antabe, R.; Antabe, G.; Sano, Y.; Batung, E. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of probable depression and anxiety symptoms in Mozambique: A secondary data analysis. PLoS Ment. Health 2025, 2, e0000169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, C.; Wainberg, M.; Oquendo, M.; Yu, Q.; Blevins Peratikos, M.; Duarte, C.; Martinho, S.; Green, A.; González-Calvo, L.; Moon, T. Depression among female heads-of-household in rural Mozambique: A cross-sectional population-based survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, C.W.; Sharot, T.; Walter, H.; Heekeren, H.R.; Dolan, R.J. Depression is related to an absence of optimistically biased belief updating about future life events. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynie, M. The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowislo, J.; Orth, U. Does Low Self-Esteem Predict Depression and Anxiety? A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Pyschological Bull. 2012, 139, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, K.L.; Jovic, M.; Vo-Phuoc, J.L.; Thorpe, J.G.; Doolan, B.L. The global cost of eliminating avoidable blindness. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 60, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.; Orkin, K.; Witte, M.; Walker, J.; Davies, T.; Haushofer, J.; Murray, S.; Bass, J.; Murray, L.; Tol, W.; et al. The Effects of Mental Health Interventions on Labor Market Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Refugees | Mozambicans | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Male headed households | 60% | 52% | 8% |

| Average age | 39 years | 36 years | 2.7 ** |

| Average household size | 4.9 | 5.3 | −0.4 |

| Education Level | |||

| No education | 5% | 25% | 20% *** |

| Primary | 27% | 64% | −38% *** |

| Secondary | 59% | 10% | 49% *** |

| Higher | 7% | 0% | 7% *** |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/Domestic Partnership | 47% | 76% | −29% *** |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 25% | 13% | 12% ** |

| Single/Never married | 27% | 8% | 19% *** |

| Prevalence Rate | GAD | Depression |

|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 25% | 31% |

| High Self Esteem (top quartile) | 3% | 4% |

| Low Self-Esteem (bottom quartile) | 65% | 66% |

| Prevalence Rate | GAD | Depression |

|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 25% | 31% |

| Low Loneliness Score (bottom quartile) | 32% | 27% |

| High Loneliness Score (top quartile) | 25% | 29% |

| Individual Is Likely to Suffer from Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | Individual Is Likely to Suffer from Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled Sample | Refugees | Mozambicans | Pooled Sample | Refugees | Mozambicans | |

| b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | b/se | |

| Financial Security Index | −0.069 ** | 0.017 | −0.114 *** | −0.069 *** | −0.038 | −0.088 ** |

| (0.030) | (0.049) | (0.037) | (0.026) | (0.036) | (0.034) | |

| Age | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Gender (1 = Women) | −0.061 | −0.084 | −0.040 | −0.075 * | −0.180 ** | −0.046 |

| (0.050) | (0.097) | (0.058) | (0.043) | (0.071) | (0.053) | |

| Years of education | −0.005 | −0.021 | 0.014 | −0.019 ** | −0.004 | −0.034 ** |

| (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.017) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.015) | |

| HH size | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.005 | −0.003 | 0.009 | −0.018 |

| (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.012) | |

| Housing | −0.017 | −0.000 | −0.028 | 0.037 * | −0.001 | 0.071 ** |

| (0.022) | (0.033) | (0.031) | (0.019) | (0.024) | (0.029) | |

| Speaks Portuguese | −0.034 | −0.125 | −0.032 | 0.050 | 0.195 *** | 0.022 |

| (0.049) | (0.092) | (0.060) | (0.043) | (0.067) | (0.055) | |

| Refugee (1 = Yes/0 = No) | 0.037 | 0.168 *** | ||||

| (0.072) | (0.062) | |||||

| Years in Mozambique (Refugees only) | −0.010 | −0.001 | ||||

| (0.009) | (0.007) | |||||

| Distance to the centre of Maratane Settlement | −0.053 *** | 0.005 | ||||

| (0.019) | (0.017) | |||||

| Constant | 0.460 *** | 0.734 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.765 *** | 0.786 *** | 0.904 *** |

| (0.096) | (0.196) | (0.122) | (0.083) | (0.143) | (0.112) | |

| r2 | 0.024 | 0.071 | 0.059 | 0.062 | 0.134 | 0.069 |

| N | 448 | 134 | 297 | 448 | 134 | 297 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beltramo, T.; Nimoh, F.; Sequeira, S.; Ventevogel, P. Interconnected Challenges: Examining the Impact of Poverty, Disability, and Mental Health on Refugees and Host Communities in Northern Mozambique. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243187

Beltramo T, Nimoh F, Sequeira S, Ventevogel P. Interconnected Challenges: Examining the Impact of Poverty, Disability, and Mental Health on Refugees and Host Communities in Northern Mozambique. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243187

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeltramo, Theresa, Florence Nimoh, Sandra Sequeira, and Peter Ventevogel. 2025. "Interconnected Challenges: Examining the Impact of Poverty, Disability, and Mental Health on Refugees and Host Communities in Northern Mozambique" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243187

APA StyleBeltramo, T., Nimoh, F., Sequeira, S., & Ventevogel, P. (2025). Interconnected Challenges: Examining the Impact of Poverty, Disability, and Mental Health on Refugees and Host Communities in Northern Mozambique. Healthcare, 13(24), 3187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243187