Family-Based Tag Rugby: Acute Effects on Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Disease and Cognition and Factors Affecting Family Enjoyment and Feasibility

Highlights

- An acute bout of family tag rugby can improve postprandial insulin concentration in parents and cognitive function in both children and their parents.

- Families from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds deem family-based tag rugby an appropriate exercise modality, which can be adapted to overcome the barriers associated with the cost of and access to local facilities for low socioeconomic status families.

- Family-based tag rugby elicits certain health (parents only) and cognitive benefits (children and parents) whilst being an enjoyable form of activity with potential for long-term implementation.

- Family-based tag rugby may be an avenue for reducing the barriers that low socioec-onomic status families face with the cost of, access to, and provision of local physical activity facilities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Characteristics

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Socioeconomic Status Classification

2.4. Experimental Procedures

2.4.1. Standardised Breakfast and Lunch

2.4.2. Capillary Blood Samples

2.4.3. Cognitive Function Tests

2.4.4. Exercise

2.5. Focus Groups and Interviews

2.5.1. Whole-Family Focus Groups

2.5.2. Parent Interviews

2.5.3. Child Interviews

2.6. Qualitative Content Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exercise Characteristics

3.2. Cardiometabolic Health Responses

3.2.1. Blood Glucose Concentrations

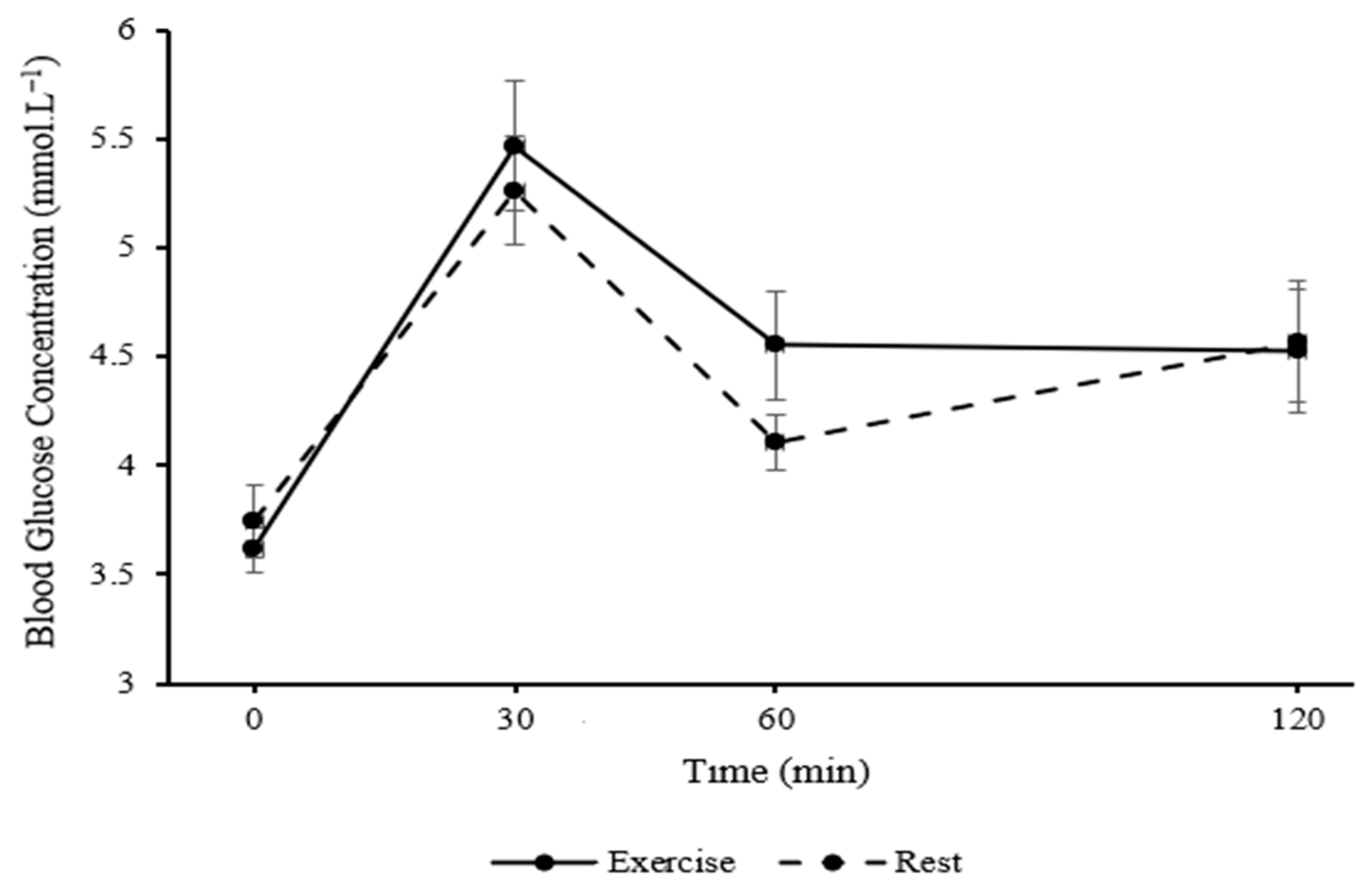

- Postprandial Blood Glucose, Glucose iAUC, and Glucose Peak in Children

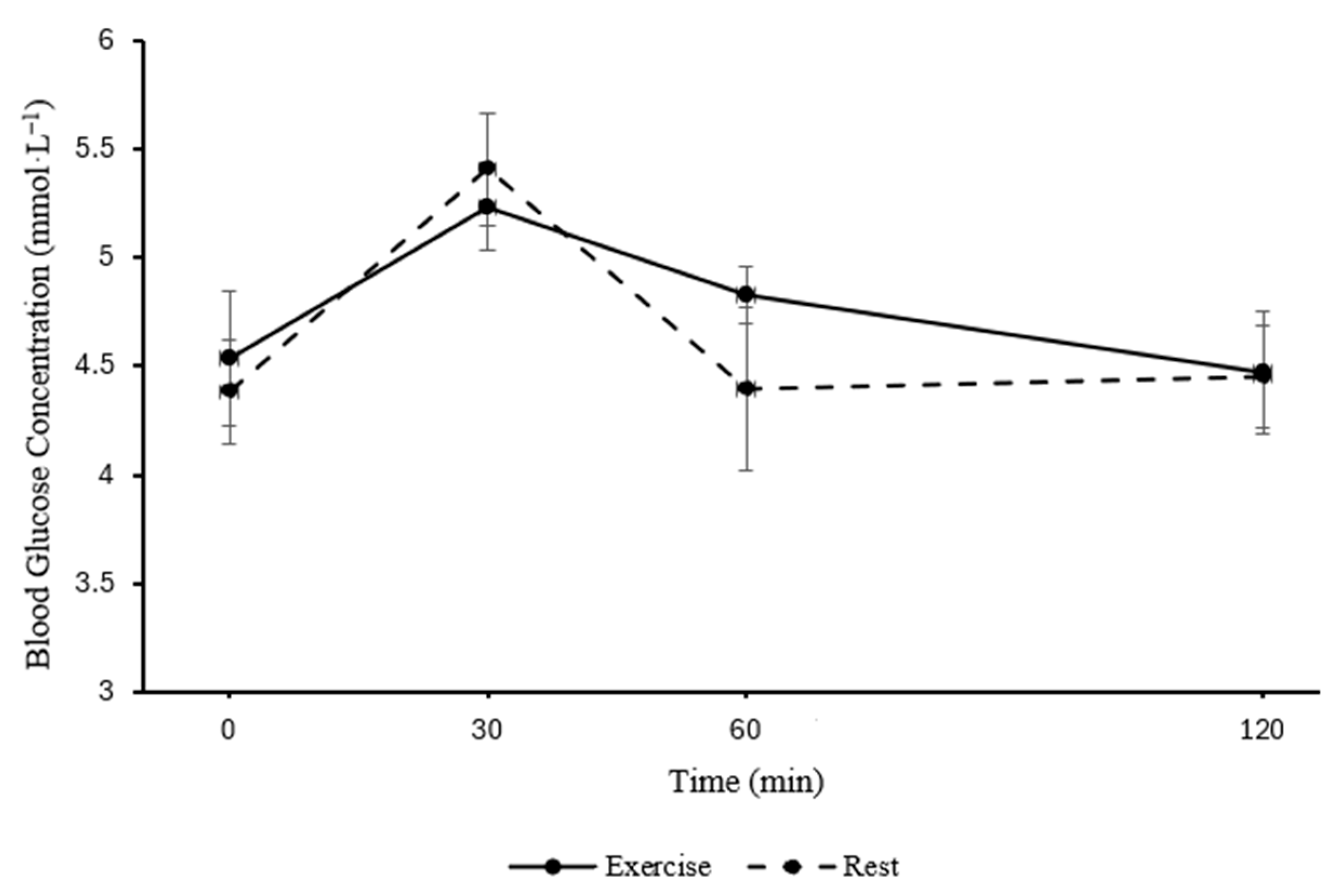

- Postprandial Blood Glucose, Glucose iAUC, and Glucose Peak in Parents

- Family Analysis

3.2.2. Plasma Insulin Concentrations

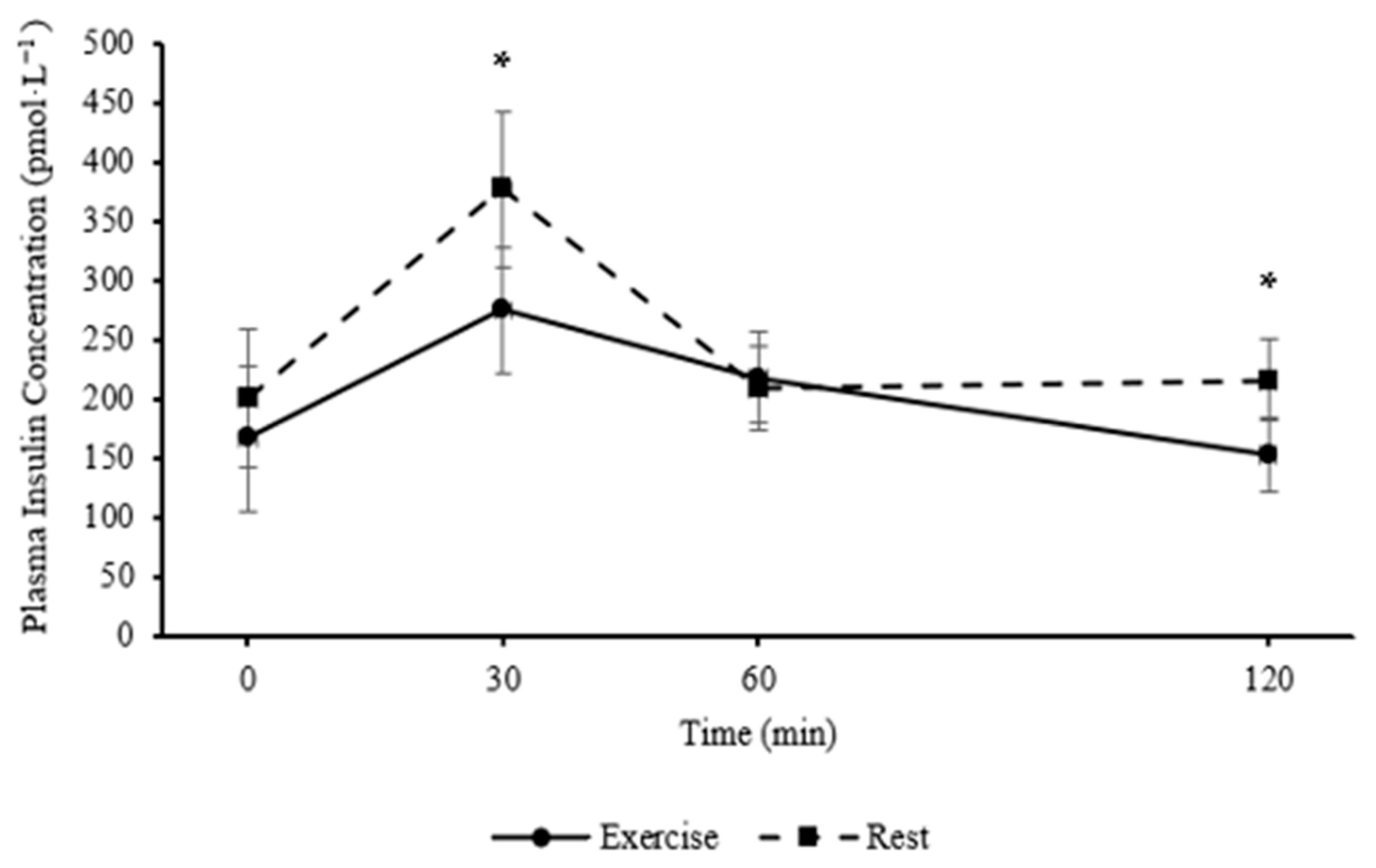

- Postprandial Plasma Insulin, Insulin iAUC, and Insulin Peak in Children

- Postprandial Plasma Insulin, Insulin iAUC, and Insulin Peak in Parents

- Family Analysis

3.2.3. Plasma Triglyceride Concentrations

- Postprandial Triglycerides, Triglyceride iAUC, and Triglyceride Peak in Children

- Postprandial Triglycerides, Triglyceride iAUC, and Triglyceride Peak in Parents

- Family Analysis

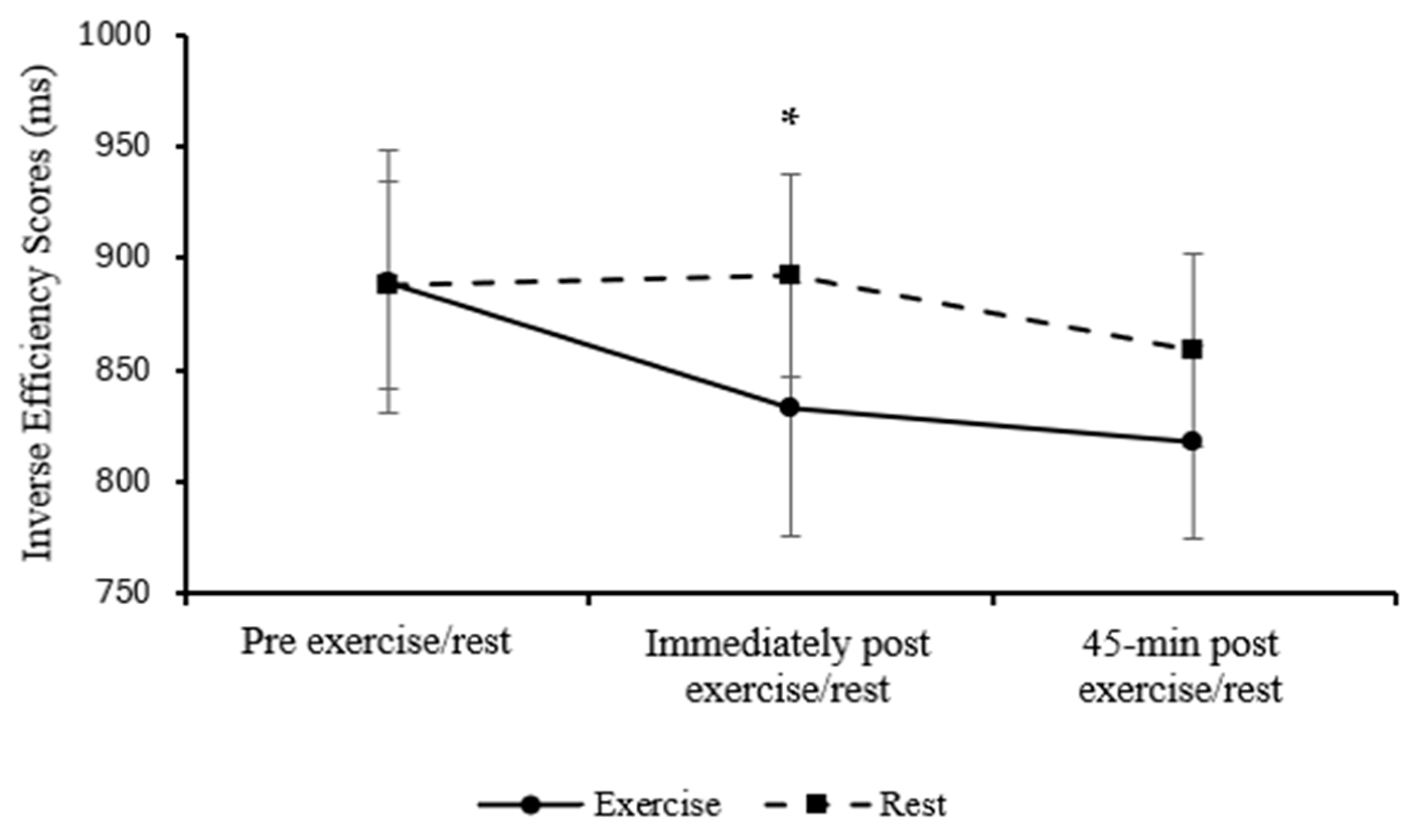

3.3. Cognitive Function Outcomes

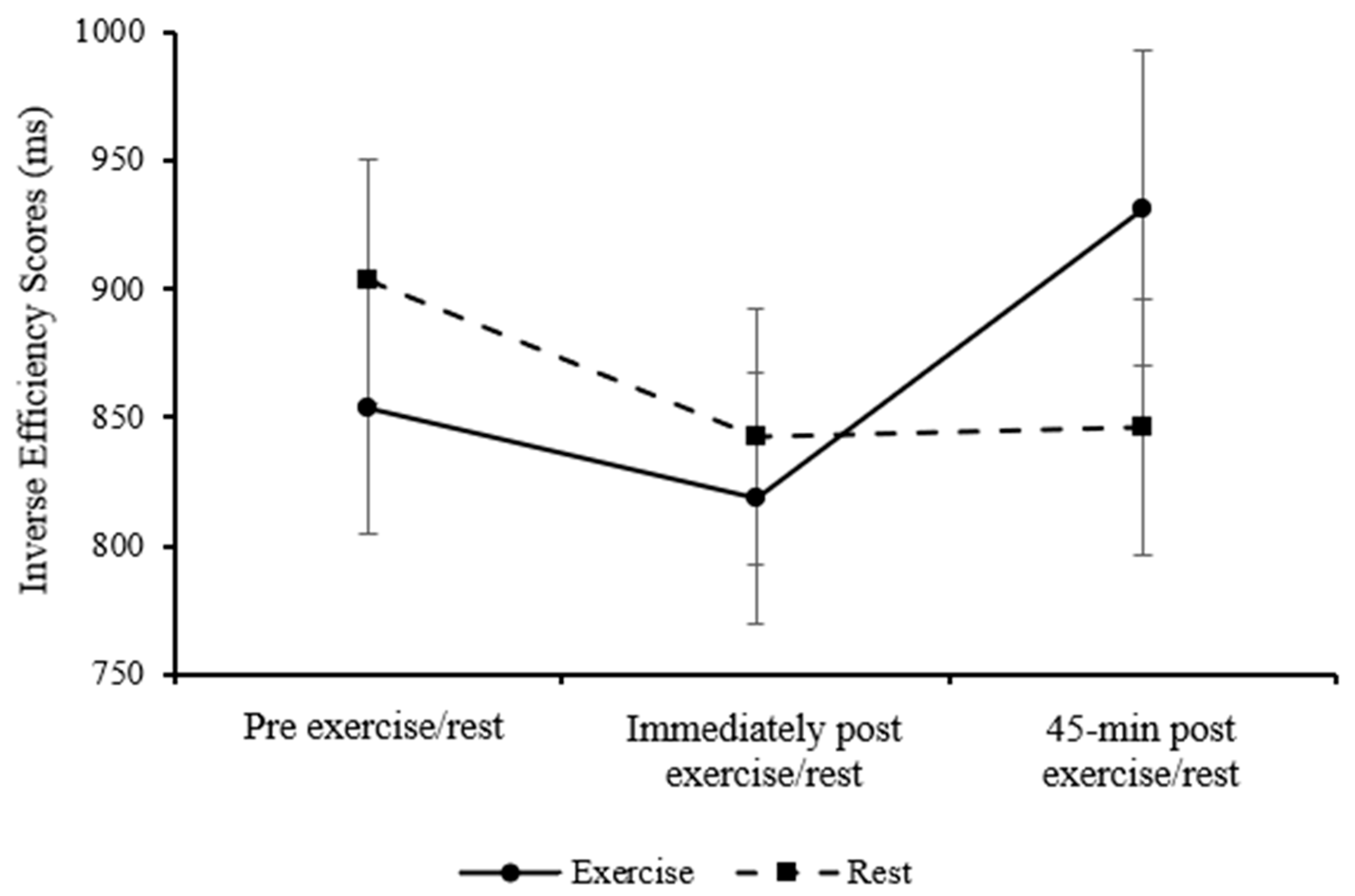

3.3.1. Stroop Test

- Children

- Parents

- Family Analysis

3.3.2. Sternberg Paradigm

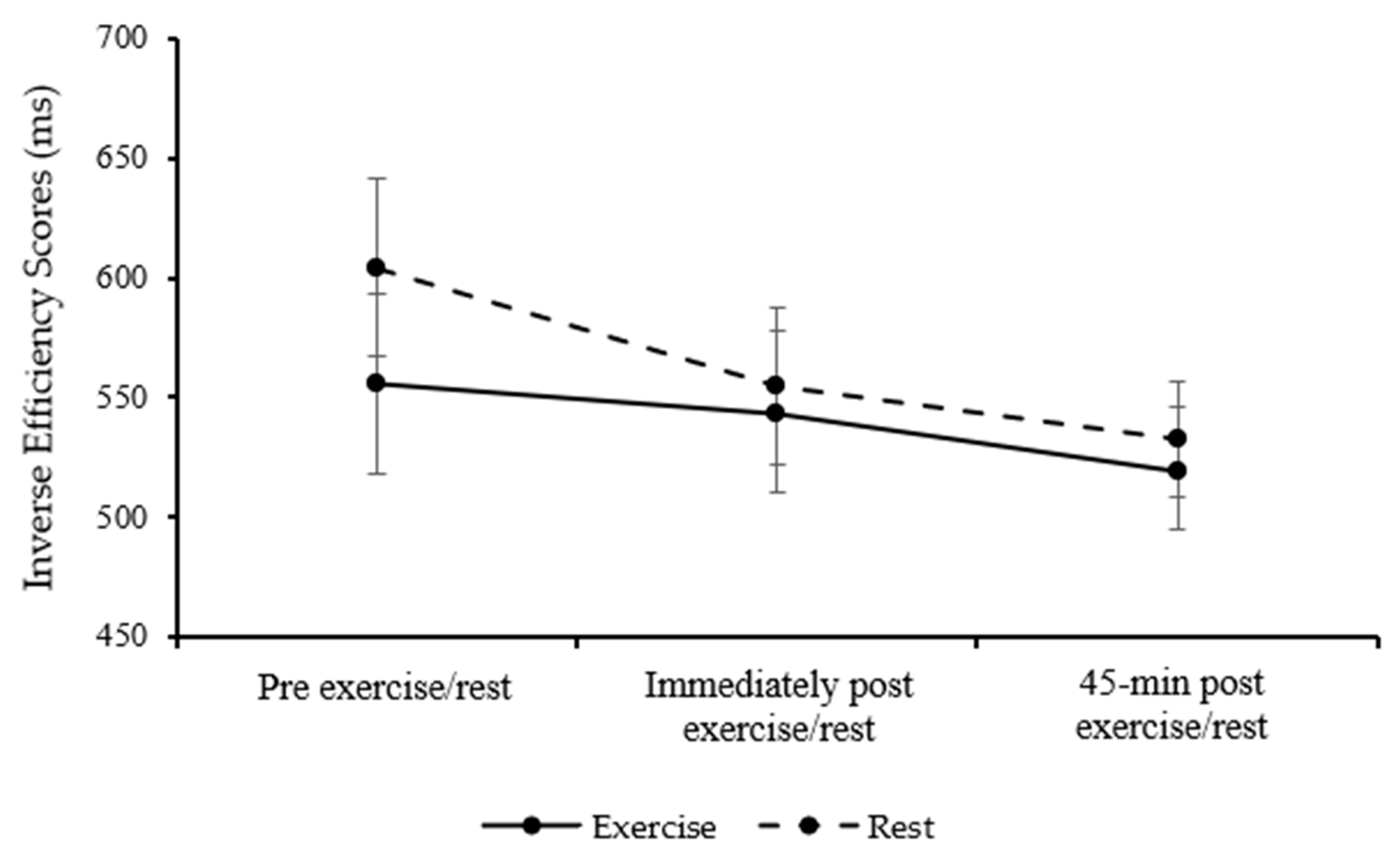

- Children

- Parents

- Family Analysis

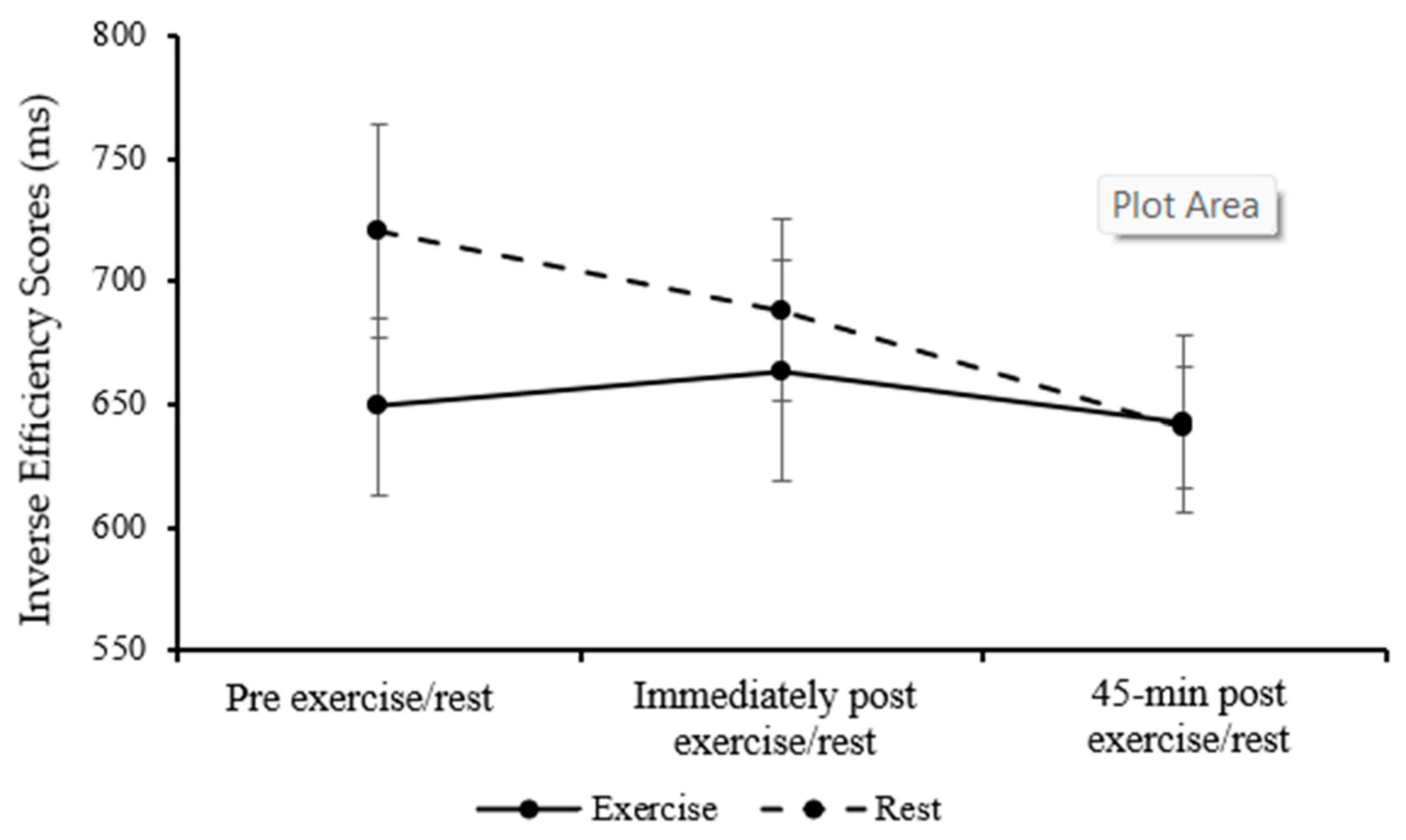

3.3.3. Flanker Task

- Children

- Parents

- Family Analysis

3.4. Focus Groups and Interviews

3.4.1. Families Perceived Enjoyment of Tag Rugby

- Inclusive and Enjoyable for the Whole Family

“But they [daughters] tend to moan a lot, you know, like oh you know, my legs are hurting. When are we there yet? So I think the tag rugby thing brings the fun aspect to it where they don’t actually realise that they’re exercising. Yeah, because they’re enjoying what they’re doing, you know?” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“I think it was nice for me to do that with the children. Yeah, because I guess there are sports that the children do where they’re doing it themselves and you’re watching them, aren’t you? So it’s quite a nice activity to get involved in where yeah, you know you have enjoyed and have fun together. Yeah. So, yeah, I thought it was, it was nice” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“Yeah, I mean the weather was great and there were different tasks and it was interactive with ages and the families as well, so it was good” (Mother, middle socioeconomic status)

“I think it depends what it is [mode of physical activity], because if it was like that fun tag rugby then that’s fine. If it was at like a different level, then I’d rather do it myself, yeah” (Daughter, high socioeconomic status)

“I think it was fun because we don’t normally do stuff like that with each other, so it’s like very different” (daughter, high socioeconomic status)

- Engaging Elements that Captivate Children and their Parents

“It was challenging because they’re kids, you know, they’re faster than that. So yeah, they’ve got more energy, though they’re pushing us” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“I thought it was good because it was quite fast moving, and so it kept everyone interested. You were just, before you could get bored anything like that in terms of switching it kept everybody on their toes and kept everybody engaged so that was quite good” (Mother, middle socioeconomic status)

“It [tag rugby game] almost got too, too free, but then some of us wanted to bring it back a little bit whereas the kids just wanted to carry on being silly. Not that it was a bad thing to be silly, we were just thinking more of the game” (mother, high socioeconomic status)

“I liked the drills except when it got repetitive, so for quite a long time it didn’t feel as fun” (Son, high socioeconomic status)

“It [tag rugby game] was very very fun. It didn’t feel that competitive. I felt like I was more having fun than competitive” (Son, high socioeconomic status)

3.4.2. Feasibility of Implementing Family-Based Tag Rugby at Home

- Modality, Intensity, and Duration of the Session

“No, it was ok because, because there was, there was a, there was half time, so there was half time. So, it’s ok when doing it, she gave us a minute. Then we continue” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“Similar to how you might go out and walk the dog, you could be with your kids on the field playing something like that. Couldn’t you, just to break the day up or something? You know, for half an hour or whatever” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“For me, I think it’s nice to do it with multiple families. There’s more interaction and the kids can have friends, and you know, we can make friends as well” (Mother, low socioeconomic status)

“I think it could’ve been a bit more high intensity just for myself because, erm, I didn’t feel like I was going as fast as I could’ve but it was tiring” (Son, high socioeconomic status)

“You could make the pitch a bit bigger so that there was more intensity encouraged and more going on, I think that might help” (Mother, middle SES)

“Yeah, especially in the summer when it’s light and you can go out and enjoy the weather” (Father, high socioeconomic status)

- Integrating Tag Rugby into Family Life

“It depends what world we’re living in, if I could be doing something with him once a day I would, but in the reality we are living in with school, other extracurriculars, we could only fit in once a week” (Mother, high socioeconomic status)

“Ermm, mornings like after I wake up after breakfast. Erm, because I think morning is when I, I feel more energetic, and it works better” (Son, middle socioeconomic status)

- Traditional team sports and low-impact sports as alternatives to tag rugby

“Because I quite like dodgeball and I quite like playing with my parents, so that would be quite fun” (son, high socioeconomic status)

“So going for walks in the countryside would be my top one because they’re really chilled out. And they get on really well, and they laugh a lot when we do go for walks. Yeah, I know they love going swimming into water parks. I really don’t like it, so I wish I liked swimming more. Whenever you say, what do you want to do? They’ll say family swim, which involves me going on slides and stuff. Erm, yeah, which I’m a bit funny about water, I don’t really like the water. Erm, but yeah, that that would if I if I could get around it that would be a good one for us” (Mother, high socioeconomic status)

“And then especially if you can mix it in with going for pub lunch and taking, like, card games. So, that, that would be my favourite thing” (Mother, high socioeconomic status)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sport England. Active Lives Children and Young People Survey Academic Year 2022–2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/research-and-data/data/active-lives (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Fairclough, S.J.; Boddy, L.M.; Mackintosh, K.A.; Valencia-Peris, A.; Ramirez-Rico, E. Weekday and weekend sedentary time and physical activity in differentially active children. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, R.M.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Sharp, S.J.; Landsbaugh, J.R.; Ekelund, U.; Griffin, S.J. An investigation of patterns of children’s sedentary and vigorous physical activity throughout the week. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropper, H.; John, J.M.; Sudeck, G.; Thiel, A. The impact of life events and transitions on physical activity: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternfeld, B.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr. Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Prev. Med. 1999, 28, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, N.W.; Turrell, G. Occupation, hours worked, and leisure-time physical activity. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, T.; Moran, A.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Steffen, L.M.; Sinaiko, A.R.; Zhou, X.; Steinberger, J. Relation of cardiometabolic risk factors between parents and children. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondell, S.J.; Hammersley-Mather, R.; Veerman, J.L. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Wiebe, S.A.; Spence, J.C.; Friedman, A.; Tremblay, M.S.; Slater, L.; Hinkley, T. Systematic review of physical activity and cognitive development in early childhood. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheval, B.; Csajbók, Z.; Formánek, T.; Sieber, S.; Boisgontier, M.P.; Cullati, S.; Cermakova, P. Association between physical-activity trajectories and cognitive decline in adults 50 years of age or older. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, Y.; Höner, O. Physical activity interventions in the school setting: A systematic review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriemler, S.; Meyer, U.; Martin, E.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Andersen, L.B.; Martin, B.W. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: A review of reviews and systematic update. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, P.J.; Nettlefold, L.; Race, D.; Hoy, C.; Ashe, M.C.; Higgins, J.W.; McKay, H.A. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 72, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.J.; Young, M.D.; Barnes, A.T.; Eather, N.; Pollock, E.R.; Lubans, D.R. Engaging fathers to increase physical activity in girls: The “dads and daughters exercising and empowered”(DADEE) randomized controlled trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, R.F.; Hesketh, K.R.; Crozier, S.R.; Baird, J.; Cooper, C.; Godfrey, K.M.; Harvey, N.C.; Westgate, K.; Inskip, H.M.; van Sluijs, E.M. The association between number and ages of children and the physical activity of mothers: Cross-sectional analyses from the Southampton Women’s Survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dring, K.J.; Cooper, S.B.; Morris, J.G.; Sunderland, C.; Foulds, G.A.; Pockley, A.G.; Nevill, M.E. Cytokine, glycemic, and insulinemic responses to an acute bout of games-based activity in adolescents. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.A.; Cooper, S.B.; Dring, K.J.; Hatch, L.; Morris, J.G.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E. Effect of football activity and physical fitness on information processing, inhibitory control and working memory in adolescents. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.A.; Cooper, S.; Dring, K.J.; Hatch, L.; Morris, J.G.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E. Effect of acute football activity and physical fitness on glycaemic and insulinaemic responses in adolescents. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendham, A.E.; Coutts, A.J.; Duffield, R. The acute effects of aerobic exercise and modified rugby on inflammation and glucose homeostasis within Indigenous Australians. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 3787–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendham, A.E.; Duffield, R.; Coutts, A.J.; Marino, F.; Boyko, A.; Bishop, D.J. Rugby-specific small-sided games training is an effective alternative to stationary cycling at reducing clinical risk factors associated with the development of type 2 diabetes: A randomized, controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, H.; Brunelli, A.; Machado, S.; Velasques, B.; Ribeiro, P.; Arias-Carrion, O.; Voelcker-Rehage, C. Intermittent maximal exercise improves attentional performance only in physically active students. Arch. Med. Res. 2012, 43, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-K.; Etnier, J.L. Effects of an acute bout of localized resistance exercise on cognitive performance in middle-aged adults: A randomized controlled trial study. Psychol. Sports Exerc. 2009, 10, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, B.; Mierau, A.; Hulsdunker, T.; Hildebrand, C.; Przyklenk, A.; Hollmann, W.; Struder, H.K. Effects of physical exercise on individual resting state EEG alpha peak frequency. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 717312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.; Quinlan, A.; Naylor, P.J.; Warburton, D.E.; Blanchard, C.M. Predicting family and child physical activity across six-months of a family-based intervention: An application of theory of planned behaviour, planning and habit. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Neely, K.C.; Newton, A.S.; Knight, C.J.; Rasquinha, A.; Ambler, K.A.; Spence, J.C.; Ball, G.D. Families’ perceptions of and experiences related to a pediatric weight management intervention: A qualitative study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Quinlan, A.; Blanchard, C.M.; Naylor, P.J.; Warburton, D.E.; Rhodes, R.E. Benefits and barriers to engaging in a family physical activity intervention: A qualitative analysis of exit interviews. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 1708–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Ng, J.Y.; Lubans, D.R.; Lonsdale, C.; Ng, F.F.; Ha, A.S. A family-based physical activity intervention guided by self-determination theory: Facilitators’ and participants’ perceptions. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 127, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, S.M.; Cooper, S.B.; Williams, R.A.; Sunderland, C.; Bowes, A.; Dring, K.J. Barriers, Facilitators, and Factors Influencing the Perceived Feasibility of Family-based Physical Activity: The Role of Socioeconomic Status. Adv. Exerc. Health Sci. 2025, 2, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; McKay, H.A.; Macdonald, H.; Nettlefold, L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Cameron, N.; Brasher, P.M. Enhancing a somatic maturity prediction model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. English Indices of Deprivation; Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government: London, UK, 2019.

- Wolever, T.M.; Jenkins, D.J. The use of the glycémie index in predicting the blood glucose response to mixed meals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 43, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, J.T.; Ashby, F.G. Stochastic Modeling of Elementary Psychological Processes; CUP Archive: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Snelgrove, S. Theme in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research; Institut fur Klinische Sychologie and Gemeindesychologie: Dresden, Germany, 2019; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, L.M.; Dring, K.J.; Williams, R.A.; Sunderland, C.; Nevill, M.E.; Cooper, S.B. Effect of differing durations of high-intensity intermittent activity on cognitive function in adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, P.; Pahkala, K.; Heinonen, O.J.; Tammelin, T.H.; Pälve, K.; Hirvensalo, M.; Juonala, M.; Loo, B.-M.; Magnussen, C.G.; Rovio, S.; et al. Physical inactivity from youth to adulthood and adult cardiometabolic risk profile. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, C.W.; Egan, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-related changes in glucose metabolism, hyperglycemia, and cardiovascular risk. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 886–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdz, D.; Alvarez-Pitti, J.; Wójcik, M.; Borghi, C.; Gabbianelli, R.; Mazur, A.; Herceg-Čavrak, V.; Lopez-Valcarcel, B.G.; Brzeziński, M.; Lurbe, E.; et al. Obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors: From childhood to adulthood. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Abdelhafiz, A.H. Cardiometabolic disease in the older person: Prediction and prevention for the generalist physician. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, F.; Ermolao, A.; van Baak, M.A.; Beaulieu, K.; Blundell, J.E.; Busetto, L.; Carraça, E.V.; Encantado, J.; Dicker, D.; Farpour-Lambert, N.; et al. Effect of exercise on cardiometabolic health of adults with overweight or obesity: Focus on blood pressure, insulin resistance, and intrahepatic fat—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, I.d.C.; Barros, N.F.D.; Caramelli, B. Lifestyle, inadequate environments in childhood and their effects on adult cardiovascular health. J. De Pediatr. 2022, 98 (Suppl. 1), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guagliano, J.M.; Armitage, S.M.; Brown, H.E.; Coombes, E.; Fusco, F.; Hughes, C.; Jones, A.P.; Morton, K.L.; van Sluijs, E.M. A whole family-based physical activity promotion intervention: Findings from the families reporting every step to health (FRESH) pilot randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, S.J.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Pittas, A.G.; Roberts, S.B.; Fuss, P.J.; Greenberg, A.S.; McCrory, M.A.; Bouchard, T.J., Jr.; Saltzman, E.; Neale, M.C. Genetic and environmental influences on factors associated with cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1917–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, A.E.; Beyl, R.A.; Hsia, D.S.; Jarrell, A.R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Mantzor, S.; Newton, R.L.; Tyson, P. Step tracking with goals increases children’s weight loss in behavioral intervention. Child. Obes. 2017, 13, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.G.; Zhu, L.N.; Yan, J.; Yin, H.C. Neural basis of working memory enhancement after acute aerobic exercise: fMRI study of preadolescent children. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludyga, S.; Gerber, M.; Kamijo, K.; Brand, S.; Pühse, U. The effects of a school-based exercise program on neurophysiological indices of working memory operations in adolescents. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, D.; Chou, E. The acute effect of high-intensity exercise on executive function: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 734–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, H.K.M.; De Mello, M.T.; de Aquino Lemos, V.; Santos-Galduróz, R.F.; Camargo Galdieri, L.; Amodeo Bueno, O.F.; Tufik, S.; D’Almeida, V. Aerobic physical exercise improved the cognitive function of elderly males but did not modify their blood homocysteine levels. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2015, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, S.; Wallis, M.; Polit, D.; Steele, M.; Shum, D.; Morris, N. The effects of multimodal exercise on cognitive and physical functioning and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in older women: A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzan-Bluma, I.; Lipowska, M. Physical activity and cognitive functioning of children: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C.R.; Cooper, R.; Craig, L.; Elliott, J.; Kuh, D.; Richards, M.; Starr, J.M.; Whalley, L.J.; Deary, I.J. Cognitive function in childhood and lifetime cognitive change in relation to mental wellbeing in four cohorts of older people. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosco, W.D.; Hawk, L.W., Jr.; Colder, C.R.; Meisel, S.N.; Lengua, L.J. The development of inhibitory control in adolescence and prospective relations with delinquency. J. Adolesc. 2019, 76, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyer, R.S.; Elshafei, H.; Hemmerlin, J.; Bouet, R.; Bidet-Caulet, A. Why are children so distractible? Development of attention and motor control from childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 2021, 92, e716–e737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.P.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Keller, C.; Dodgson, J.E. Barriers to physical activity among African American women: An integrative review of the literature. Women Health 2015, 55, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailey, E.L.; Huberty, J.; Dinkel, D.; McAuley, E. Physical activity barriers and facilitators among working mothers and fathers. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Socioeconomic Status Group | Number of Families | Number of Children | Number of Parents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Socioeconomic Status (Deciles 1–3) | 6 | 8 | 6 |

| Middle Socioeconomic Status (Deciles 4–7) | 5 | 11 | 8 |

| High Socioeconomic Status (Deciles 8–10) | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Characteristic | Children | Parents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N = 27 | Girls n = 11 | Boys n = 16 | Overall N = 20 | Mothers n = 14 | Fathers n = 6 | |

| Age (y) | 11.73 ± 1.93 | 11.91 ± 2.13 | 11.60 ± 1.85 | 45.50 ± 9.02 | 44.08 ± 8.84 | 48.83 ± 9.33 |

| Height (m) | 1.50 ± 0.13 | 1.51 ± 0.14 | 1.50 ± 0.13 | 1.69 ± 0.06 | 1.67 ± 0.04 | 1.75 ± 0.05 |

| Body mass (kg) | 44.67 ± 14.36 | 42.93 ± 16.44 | 45.87 ± 13.16 | 86.51 ± 20.39 | 82.88 ± 22.30 | 94.98 ± 12.83 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.58 ± 5.05 | 18.40 ± 4.70 | 20.40 ± 5.26 | 30.22 ± 6.89 | 29.78 ± 7.79 | 31.24 ± 4.58 |

| BMI Percentile | 45.26 ± 35.57 | 29.91 ± 29.61 | 55.81 ± 36.30 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Maturity Offset (y) | −1.10 ± 1.95 | −0.03 ± 2.03 | −1.84 ± 1.55 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fountain, S.M.; Walters, G.W.M.; Williams, R.A.; Sunderland, C.; Cooper, S.B.; Dring, K.J. Family-Based Tag Rugby: Acute Effects on Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Disease and Cognition and Factors Affecting Family Enjoyment and Feasibility. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243186

Fountain SM, Walters GWM, Williams RA, Sunderland C, Cooper SB, Dring KJ. Family-Based Tag Rugby: Acute Effects on Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Disease and Cognition and Factors Affecting Family Enjoyment and Feasibility. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243186

Chicago/Turabian StyleFountain, Scarlett M., Grace W. M. Walters, Ryan A. Williams, Caroline Sunderland, Simon B. Cooper, and Karah J. Dring. 2025. "Family-Based Tag Rugby: Acute Effects on Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Disease and Cognition and Factors Affecting Family Enjoyment and Feasibility" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243186

APA StyleFountain, S. M., Walters, G. W. M., Williams, R. A., Sunderland, C., Cooper, S. B., & Dring, K. J. (2025). Family-Based Tag Rugby: Acute Effects on Risk Factors for Cardiometabolic Disease and Cognition and Factors Affecting Family Enjoyment and Feasibility. Healthcare, 13(24), 3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243186