Abstract

Background/Objectives: Emotional intelligence can be understood as the ability to perceive, understand and manage one’s own emotions and those of others, promoting personal and social well-being. In the school context, Physical Education is an ideal setting for developing these skills. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and analyse programmes that integrate emotional intelligence into Physical Education in primary education. Methods: To this end, a systematic review was carried out, based on the PRISMA method, in the Web of Science, ERIC and PsycInfo databases, analysing scientific literature related to Physical Education and Emotional Intelligence. Likewise, the PICO strategy was used to develop the inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in the selection of 11 articles. Results: The results showed that well-planned pedagogical models and active methodologies enable the development of skills such as self-esteem, empathy, emotional self-regulation and motivation. Similarly, integrated approaches that purposefully combine movement and emotion produced more positive and lasting effects than traditional interventions focusing solely on physical aspects. Conclusions: The main conclusion is that pedagogical models in Physical Education can promote the development of emotional variables such as empathy, self-regulation, self-confidence, and motivation in primary school students. These findings highlight the need for further research in this area and for the promotion of structured educational programmes that intentionally incorporate emotional work into Physical Education from the early stages of schooling.

1. Introduction

Currently, Physical Education must not only focus on students’ motor and academic development but also address their social and emotional dimensions [1]. In this context, emotional intelligence has gained importance as a key factor in psychological wellbeing, academic performance and interpersonal relationships [2,3].

Emotional intelligence can be understood as the ability to perceive, understand, regulate, and use one’s own and others’ emotions effectively [4]. One of its main proponents, Goleman [5], proposed an expanded model identifying five key dimensions: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. The accumulation of these skills is essential for effective emotional adaptation in any environment. For his part, Bisquerra [6] emphasises that it should be understood as a personal trait and as a crucial educational skill that must be consciously developed at school.

During primary education, emotions play a significant role and directly influence how children build their personalities, learn to live together and understand the world around them [7]. In this sense, Physical Education, thanks to its experiential, dynamic and playful nature, becomes a perfect setting for working on motor skills and socioemotional competencies such as empathy, self-regulation, self-control and assertiveness [8,9].

In this line, from a neuroscientific perspective, physical activity can promote emotional release and expression. It also considers emotions to be drivers or obstacles to learning. On the other hand, Physical Education understands the body holistically, seeking physical, psychological, and emotional development through motor action. Thus, Physical Education, due to the need to cooperate, compete, develop strategies, or interact with others in an educational context based on physical activity, allows not only for learning related to emotional identification, but also for promoting greater emotional well-being [10,11].

For Physical Education to become a true tool for developing social and personal skills and promoting healthy lifestyles, it must be well structured and planned [12]. To this end, teaching must go beyond physical activity, working on the emotional aspect using the body, with the aim of promoting comprehensive training [13]. In this regard, there are different programmes within Physical Education that have made considerable progress in the emotional intelligence of students. One of them uses the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility model (TPSR), which has shown a clear improvement in the development of socio-emotional skills, thanks to increased participation, autonomy and respect [14].

Mindfulness-based interventions have proven to be an effective way to improve adaptive emotional regulation [15]. In turn, regular physical activity is associated with an increase in social-emotional skills, provided there is an environment of positive peer relationships [16]. Likewise, Corporal Expression has become an especially valuable tool for working on emotional awareness, self-control and empathy through non-verbal communication, encouraging students to develop new ways of connecting with themselves and others [9].

Similarly, cooperative strategies in Physical Education have proven to be an effective way to strengthen emotional intelligence, promoting skills such as self-control, empathy, and emotional awareness [8]. These skills improve coexistence by creating a more positive environment in the classroom, where students feel more motivated and engaged. In fact, this approach directly influences students’ intrinsic motivation and academic performance [3].

However, despite the value that scientific evidence gives to emotional intelligence in Physical Education, its presence in the curriculum is still limited and, in many cases, disorganised. The reason for this absence is probably due to the fact that Physical Education has focused on content such as strength, endurance, and other more traditional topics, and has neglected content related to the more expressive realm or emotional intelligence, probably due to aspects related to the fact that Physical Education has always been closer to the male model and the gender roles associated with that model [17]. As warned by Benítez-Sillero et al. [12], Physical Education teachers need to receive specific training in methodologies that integrate socio-emotional objectives in a practical and contextualised way.

Therefore, this study is a systematic review whose objective is to identify and analyse the programmes implemented in primary education that address emotional intelligence from the perspective of Physical Education and their impact and improvement on students’ emotional development.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to conduct a systematic review to identify and analyse existing research on emotional intelligence and Physical Education, especially in primary education. To carry out this review, the guidelines established by the PRISMA statement [18] and the practical guide for systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis [19] were followed. The PICO strategy was used to establish the inclusion and exclusion criteria [20]. Likewise, the procedures were defined prior to the start of the study and subsequently modified, registering the review in PROSPERO (Prospective International Register of Systematic Reviews) with the identification number CRD420251089165, accessible at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251089165 (30 September 2025).

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria established in this research were: (a) that the study was scientific in nature and addressed the analysis of emotional intelligence, or aspects related to it, from the perspective of Physical Education; (b) that it was a research study; (c) that it focused on primary school students; and (d) that it was written in one of the following languages: Spanish, English or Portuguese (Due to availability and cultural proximity). Likewise, a time frame limited to the last five years (The linguistic and temporal restrictions correspond to the exclusion criteria applied and those works excluded for these reasons have not been considered less relevant) was established with the aim of highlighting the latest research combining aspects related to Emotional Intelligence in Physical Education and presenting a review of the most recent advances, with the aim of presenting and updating the latest research on this topic. The selected articles were the result of a screening process based on these eligibility criteria. In addition, the bibliographic references of the included studies were reviewed to broaden the search. In this regard, to present information with a marked scientific character that meets quality standards, all documents reviewed corresponded to scientific literature, omitting grey literature or non-indexed publications. The time limit set for the search, together with the omission of grey literature, ensured that the publications selected are of high quality, as they were published in high-impact journals. It also ensured that all these studies contain a theoretical basis that corresponds with the literature already available to date.

2.2. Search Strategy

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines established by the PRISMA statement [18]. To begin the process, a search phrase was defined: (primary education OR primary school OR elementary school OR basic education) AND (Physical education) AND (Emotional intelligence OR Emotional Education OR Emotional skills OR Socio-emotional skills OR Socio-affective skills OR emotional competence OR emotional competency OR emotional competencies OR emotional competencies OR emotional intelligence model OR Emotional learning OR Socio-emotional learning OR Socio-affective learning OR SEL) AND (intervention OR experimental OR quasi-experimental OR randomised controlled trial). Subsequently, articles were searched for in different databases (Web of Science, Psycinfo, and Eric) from 11 April to 16 May 2025. This search was structured into three fundamental areas: (1) Physical Education; (2) emotional intelligence; and (3) intervention, experimental, quasi-experimental, randomised controlled trial. After completing the process, duplicate records were removed.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Processing

Once the search process was complete, the titles and abstracts were examined to identify those that adequately met the inclusion criteria, excluding those that did not. As a result, 11 articles were selected and subjected to a detailed analysis, focusing specifically on emotional intelligence as the main topic. The bibliographic references of these works were then reviewed to locate any additional relevant studies; however, no new articles were included. The process was carried out independently by two experts, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. In cases where doubts arose regarding the inclusion or exclusion of a study, a third expert acted to decide on the matter. All three researchers are specialists in the development of systematic reviews and have experience in the field of Physical Education due to their academic training.

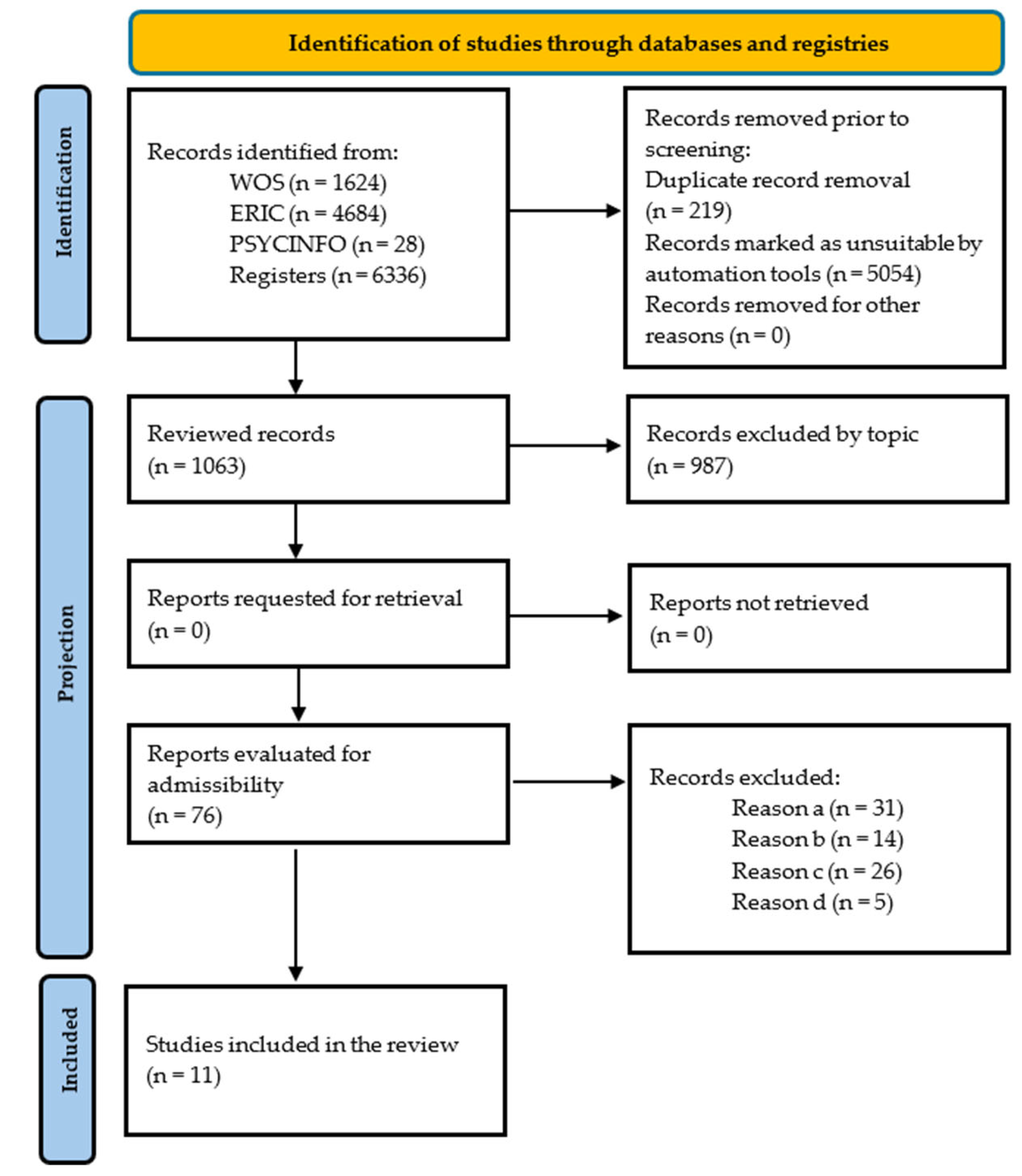

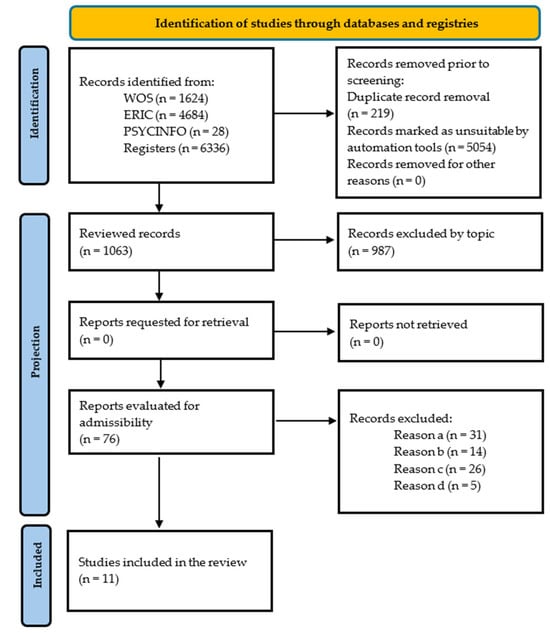

Figure 1 shows a flow chart that visually illustrates the procedure followed for selecting the studies included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart (PRISMA, 2020) [18].

2.4. Quality Assessment

After selecting the articles included in the review, their quality was assessed using the tool known as “Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Research Papers from a Variety of Fields” [21], designed for quantitative and qualitative studies. Each study was assessed according to the criteria corresponding to each type, considering aspects such as methodological design, sample characteristics, methodological approach, data analysis, and presentation of results and conclusions. The items were rated according to the level of compliance observed: 2 points if it complied satisfactorily, 1 if it complied partially, 0 if it did not comply, and NA if it did not apply (the latter only in quantitative studies). The overall score for quantitative studies was calculated as follows: [(“satisfactory items” × 2) + (“partially satisfactory items” × 1)/28 − (“not applicable items × 2)]. For qualitative studies, the following formula was used: [(“satisfactory items” × 2) + (“unsatisfactory items” × 1)/20]. The results were expressed as a percentage, within a range of 0% to 100%. The evaluation was carried out independently by two researchers (Table S1: Observer assessment 1. Table S2: Observer assessment 2), with the aim of ensuring the greatest possible impartiality. Regarding the assessment of risk of bias, aspects such as selection (studies with non-randomized samples or participant recruitment), performance bias (blinding of informants not clearly identified), and publication bias (omissions of secondary outcomes or protocols not accessible in some cases) can be considered.

2.5. Data Collection

First, data were collected from the selected articles. Next, the information collected was verified, following the PRISMA guidelines [18]. The analysis focused on fundamental aspects such as the characteristics of the participants, the type of intervention applied, the results obtained, and the methodological design of each study, all while respecting the structure.

3. Results

In the initial phase of the database search, a total of 1063 records were identified, of which 987 were excluded after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, also considering the removal of duplicates and those that were not relevant to the topic. As a result, the systematic review finally included a total of 11 articles that met the established requirements (Figure 1). Several manuscripts were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, such as one by Peñalva-Vélez et al. [22].

3.1. Quality of Studies

The quality ratings of the articles are represented as percentages, ranging from 0 to 100%, with values between 0.80 and 0.95 (Table 1). To determine the degree of agreement between the evaluators, the intraclass correlation coefficient was used, obtaining a value of 0.791 (p = 0.010), which reflects a good degree of agreement [23]. Once the degree of agreement had been established, a conservative inclusion criterion was jointly defined, selecting only those studies with a score of 55% or higher. The overall scores ranged from 0.82 to 0.92 for the first evaluator and from 0.82 to 0.90 for the second.

Table 1.

Quality ratings of articles.

3.2. Study Results

The information extracted from the articles was synthesised according to different units of analysis, which included: Author(s); Country; Context; Subjects; Age; Methodology; Type of study; Duration and Protocol. The main characteristics of the selected studies are presented below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main Characteristics of the Study Sample.

Table 3 summarises the methodologies applied, the instruments used, the variables addressed, and the main findings obtained in the studies analysed. The results highlight the complexity inherent in the process of developing emotional intelligence in the school context, especially in primary education, as well as the role of Physical Education as a means of achieving this.

Table 3.

Treatment Variables and Main Results and Relationships of Physical Education with Emotional Intelligence.

Based on the research consulted, clear benefits were identified in aspects related to emotional well-being, behavioural commitment, and perception of social competence. These advances occurred in environments where the active participation of students was promoted and they were given space to make decisions autonomously [25,27,28,34]. Programmes that opted for more expressive and creative approaches not only improved students’ emotional state but also helped to build a more inclusive and cooperative classroom environment [25,26].

In addition, the use of active methodologies in Physical Education, such as cooperative learning [24] or gamification [33], was found to be associated with notable improvements in key emotional competencies, such as self-regulation, empathy, self-awareness, and motivation. Taken together, these findings support the need to integrate emotional objectives into traditional classes and reinforce the importance of training teachers in socio-emotional terms. Thus, Physical Education is presented as an effective pedagogical tool for the comprehensive development of students. Likewise, it has been observed that innovations in Physical Education, especially those related to active methodologies and the incorporation of more expressive content, are more suitable for developing emotional skills in students.

In terms of the duration and effectiveness of the program, it can be observed that longer programs achieve more solid and significant results [24,27] than shorter ones [29,34].

In relation to gender, heterogeneity is observed in terms of differences, with improvements in boys in interventions based on Corporal Expression [26] and an increase in negative emotions in more competitive contexts [29]. In relation to girls, these changes are less intense [26].

In terms of context, those that incorporated variables related to social skills, social responsibility, or cooperation showed positive results in more dimensions related to SEL [24,28,30].

On the other hand, it could be considered that the risk of bias in the reports included could be moderate overall, finding studies that do not have registered or accessible protocols. The results should be considered with caution due to the diversity of thoroughness in the presentation of neutral or negative results. Similarly, the certainty of evidence should be considered with caution due to the heterogeneity in the results, instruments, sample size, or type of design of the studies analysed.

Table 4 below presents the main findings regarding the authors and duration of the programs, the bases for intervention, and the social-emotional dimensions addressed.

Table 4.

Study basis and improved dimensions.

Table 4 defines the extent to which emotional intelligence advances depending on the basis of the intervention. In this sense, expressive methodologies show progress in a greater number of dimensions than the other bases of intervention. Thus, they stand out for presenting dimensions such as emotional expressiveness or the reduction of aggressive behaviour, which do not appear in other cases [25,26].

Active methodologies stand out for presenting dimensions such as autonomy, cooperation, conflict resolution, and participation [24,28,32,33,34]. They also coincide with expressive methodologies in dimensions such as respect, motivation, and self-esteem [25,26]. In this line, gamification is presented as more effective and closer to emotional intelligence models [33].

Extracurricular physical activity promotes improvements in motivation and social skills [30], coinciding with expressive [25,26] and active methodologies [24,28,32,33,34], as well as improvements in SEL. Improvements are also seen in aspects related to mental health, in this case through methodologies that seek relaxation and body awareness [27]. In this sense, the results point to differences in the improvement of dimensions depending on the methodologies implemented.

4. Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to identify and analyse programmes implemented in primary education that address emotional intelligence from the perspective of Physical Education and their impact and improvement on students’ emotional development.

After analysing the results obtained, the value of emotional intelligence in the comprehensive development of students becomes evident, as does how Physical Education can become an ideal educational space to work on it. Theoretical approaches [4,5,6] had already highlighted that emotional intelligence directly influences well-being, coexistence and academic performance. With the aim of reinforcing this idea, there are diverse types of methodology that, when applied in Physical Education, positively and lastingly enhance the dimensions of emotional intelligence.

Specifically, improvements can be observed in skills such as self-control, self-esteem and emotional awareness in interventions that used expressive methodologies, such as dramatisation or body language [25,26]. Aguilar-Herrero [49] demonstrates through the application of the “Move Against Bullying” programme that skills such as empathy, self-regulation and group cohesion can be promoted through the use of Corporal Expression, supporting the idea that Physical Education can influence emotional competence and help prevent school violence. According to Armada-Crespo [35], Corporal Expression is a component of Physical Education that acts to channel emotions, reinforce personal identity and build more harmonious coexistence, clearly influencing the comprehensive education of students.

For their part, programmes that incorporated active methodologies, such as cooperative learning [24] or the TPSR model [28,34], achieved clear improvements in such key areas as empathy, leadership skills, responsibility and cooperation. These advances coincide with the findings of Rivera-Pérez et al. [8] and Gil-Moreno & Rico-González [3] who emphasise that collaboration and group work strengthen socio-emotional skills that, in addition to being useful in school, are essential for positive coexistence and a more balanced environment.

Furthermore, the emotional benefits were particularly evident in well-designed sessions. Kliziene et al. [27] observed a significant reduction in anxiety among Physical Education students when classes were structured with intention and care. This finding underscores the importance of planning with a clear purpose, seeking to promote emotional well-being and physical performance.

From another perspective, recent research such as that by Carcelén-Fraile [33] and Fenalampir et al. [32], who advocate the use of innovative methodologies such as gamification or the HPC approach, demonstrates benefits in dimensions of children’s socio-emotional development such as motivation, self-confidence, empathy, and emotional self-regulation. These conclusions are in line with studies such as that by Wright et al. [50] who argue that meaningful and motivating methodologies have the power to engage students and enhance their emotional growth in the classroom.

Similarly, the results of Goh et al. [30] and Melguizo-Ibañez et al. [31] support the idea that systematic physical activity, both inside and outside school hours, is associated with an increase in socio-emotional skills. Specifically, improvements were observed in self-esteem, self-concept and emotional repair, which coincides with the contributions of Wang et al. [16] highlighting the relationship between regular exercise and socio-emotional skills, especially in contexts where interpersonal relationships between peers are positive. These effects reinforce the view of Gordon et al. [13] who defend the comprehensive educational value of Physical Education when it is oriented towards goals beyond physical performance.

In this regard, it can be observed that studies that develop interventions based on expressive techniques such as Corporal Expression or Dramatization [25,26] show significant improvements in a greater number of dimensions of personal and social development than interventions that focus on methodological aspects [24,33], suggesting that expressive content may be relevant in the development of emotional intelligence. Likewise, in terms of duration and effectiveness, those interventions with a longer duration presented more significant results than those with fewer hours.

In this sense, expressive methodologies and active methodologies show more significant improvements than interventions based on relaxation and body awareness or extracurricular physical activity. Thus, expressive methodologies seem to enhance aspects related to the individual (emotional expressiveness, self-esteem, self-control, motivation) and in relation to others (social skills, respect, or reduction of aggressive behaviour) [25,26]. This connects with active methodologies such as cooperative learning, gamification, or TPSR. In this way, gamification coincides with expressive methodologies in aspects related to the individual (self-esteem and self-concept) and in relation to peers (social skills) [33]. On the other hand, cooperative learning refers to improvements in dimensions that connect with others (empathy, respect, and cooperation) [24]. This is repeated in an equivalent way with TPSR (participation and conflict resolution), showing some improvements in the personal sphere (autonomy and responsibility) [24,28,32,33,34].

In contrast, more traditional approaches tend to leave the emotional component in the background. As a result, they generate competitive dynamics that can provoke negative emotions such as frustration, anxiety, or demotivation, especially among students with lower motor skills or fragile self-esteem [29]. In this line, the use of different methodologies has an impact on the dimensions of emotional intelligence that improve.

The findings obtained in this systematic review demonstrate that Physical Education interventions could positively influence the five dimensions of emotional intelligence [5], thus reinforcing the value of the emotional approach in Physical Education as a vehicle for achieving comprehensive education [4,6,10,11]. The connection between the results and the theoretical frameworks reviewed suggests that Physical Education, when designed from an emotional perspective, could act as a privileged educational space for SEL. In line with previous findings and literature, it is necessary to specifically incorporate emotional intelligence into education laws and curricula for the training of future Physical Education teachers. This would involve improving this subject based on existing premises and aligned with the true nature of the activity proposed by fields such as neuroscience. Building the subject on scientific evidence will improve the quality of Physical Education, in line with the 4th sustainable development goal (Quality Education).

However, despite the positive results, some limitations found in the reviewed studies must also be addressed. These limitations could be differentiated between methodological and review limitations. First, some of them have methodological shortcomings, such as the use of small samples or the absence of control groups, which complicates the possibility of applying these findings to other educational contexts with confidence. Furthermore, most studies follow quantitative approaches, leaving aside the more experiential part of the students’ experience. This limits the ability to understand how students live, feel, or interpret these interventions. Therefore, incorporating mixed methods could enrich the research and generate a more comprehensive and closer approach. There is also variability between the methodologies used, making it difficult to compare results directly and draw generalisable conclusions. On the other hand, and taking into account the limitations related to the review itself, all the studies focus solely on primary education, without considering the effects that these interventions could have at other stages of education. There is also a language bias, as most of the studies are written in Spanish, which can make it difficult to access relevant research published in other languages. On the other hand, several challenges can be observed in teaching planning, since certain methodologies, such as those focused on competition, could induce negative emotions such as frustration, anger or sadness. Therefore, for good teaching practice, it is necessary to provide teachers with continuous training in content related to emotional intelligence [12].

Given these limitations, future lines of research should focus on designing studies with more rigorous and systematic methodologies and larger and more diverse samples that examine the dose–response effect more systematically. Similarly, it would be advisable to develop mixed-method research that analyses students’ experiences of the programmes implemented. It is also considered essential to broaden the focus to other educational stages to evaluate the impact of the proposals in contexts other than primary education. In turn, it would be interesting to review studies published in other languages, thereby broadening the theoretical and empirical framework. Another fundamental aspect is to investigate how teachers’ knowledge of emotional intelligence influences the planning of sessions and the creation of positive affective climates within the classroom. Finally, technology could be key to opening a wide range of possibilities for working on emotional intelligence in a more motivating and accessible way that is adapted to the needs of students.

5. Conclusions

The results of this systematic review allow us to conclude that Physical Education can be an ideal space for both the development of motor skills and the promotion of emotional intelligence in primary school. The evidence collected shows that, thanks to active and well-planned methodologies, emotional variables such as empathy, self-regulation, self-confidence and motivation can be significantly improved. Furthermore, by intentionally incorporating socio-emotional content into this subject, teaching practice could be enriched, and the psychosocial well-being of students could be affected. Likewise, expressive content promotes the improvement of emotional intelligence in primary school students. For all these reasons, research in Physical Education in relation to Emotional Intelligence in Primary Education should take into account the use of Active Methodologies, the use of Corporal Expression and, above all, rigorous and exhaustive planning that allows for the implementation of programs that positively influence students’ social-emotional skills. Likewise, the use of mixed methods should be considered, as they allow for more complete information to be gathered on the students’ experience, as well as broader and more diverse samples. Considering the scientific evidence and findings, Physical Education should include a curriculum, training and practical application in schools that addresses not only motor skills, but also psychological and emotional aspects. Thus, one of the main innovations presented in this systematic review is the review of Physical Education from a perspective that goes beyond the physical aspect alone. This allows the subject to be understood as holistic content that enables the comprehensive development of students. For all these reasons, future research should overcome the methodological limitations presented above and develop actions that combine methodologies to have a significant impact on a greater number of dimensions. This would mean focusing Physical Education on progress in relation to motor skills, but without neglecting psychological and emotional development.

This study presents a variety of practical applications in the field of education, specifically aimed at primary school teachers. On the one hand, it provides a systematic and up-to-date review of emotional intelligence in Physical Education. On the other hand, it includes specific teaching strategies for working on these skills in the classroom. For emotionally competent planning, the resources collected in the review can serve as a guide for teacher training, contributing to the construction of a more affective, inclusive and motivating environment. In short, this research aims to provide a solid foundation that enriches teaching from an emotional point of view, with clear proposals for which practices yield results in real contexts and how to adapt them to the needs of the classroom.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13233166/s1, Table S1: Observer assessment 1. Table S2: Observer assessment 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.M.-P. and J.M.A.-C.; methodology, J.L.M.-P. and J.M.A.-C.; software, J.L.M.-P., F.E.A.-C. and M.D.A.-H.; validation, J.L.M.-P., M.D.A.-H. and J.M.A.-C.; formal analysis, J.L.M.-P., M.D.A.-H. and J.M.A.-C.; investigation, J.L.M.-P., F.E.A.-C., A.R.-C. and J.M.A.-C.; resources, J.L.M.-P., M.D.A.-H. and F.E.A.-C.; data curation, J.L.M.-P., F.E.A.-C. and J.M.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.M.-P., F.E.A.-C., A.R.-C., M.D.A.-H. and J.M.A.-C.; writing—review and editing, A.R.-C., M.D.A.-H. and J.M.A.-C.; visualization, A.R.-C., M.D.A.-H. and J.M.A.-C.; supervision, J.L.M.-P., M.D.A.-H. and J.M.A.-C.; project administration, J.M.A.-C.; funding acquisition, J.M.A.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All information relating to the results can be found in the article or in Supplementary Materials. For further information, please consult the bibliographical references of the articles selected for the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors of this volume and the journal for the opportunity to publish in this Special Issue.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PROSPERO | Prospective International Register of Systematic Reviews |

| TPSR | Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility |

| SEL | Social-emotional learning |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HPC | Homogeneity Psycho Cognition |

| NR | No reported |

| NCG | No control group |

References

- Malinauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V. Training the Social-Emotional Skills of Youth School Students in Physical Education Classes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 741195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrándiz, C.; Hernández, D.; Berjemo, R.; Ferrando, M.; Sáinz, M. Social and Emotional Intelligence in Childhood and Adolescence: Spanish Validation of a Measurement Instrument. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2012, 17, 309–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Moreno, J.; Rico-González, M. The Effects of Physical Education on Preschoolers’ Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Emotional Intelligence: Theory, Findings, and Implications. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ for Character, Health and Lifelong Achievement; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, R. Psicopedagogía de Las Emociones; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. La Inteligencia Emocional En El Contexto Educativo: Hallazgos Científicos de Sus Efectos En El Aula. Rev. Educ. 2003, 97, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Pérez, S.; León-del-Barco, B.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; González-Bernal, J.J.; Iglesias Gallego, D. Linking Cooperative Learning and Emotional Intelligence in Physical Education: Transition across School Stages. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Morente, A.; Farré, M.; Quesada-Pallarès, C.; Filella, G. Evaluation of Happy Sport, an Emotional Education Program for Assertive Conflict Resolution in Sports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, I. Educación Física Emocional. De La Teoría a La Práctica; INDE: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.inde.com/libro/educacion-fisica-emocional/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Pellicer, I. NeuroEF. La Revolución de La Educación Física Desde La Neurociencia; INDE: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://www.inde.com/libro/neuroef/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Benítez-Sillero, J.D.D.; Gea-García, G.M.; Martínez-Aranda, L.M.; Quartiroli, A.; Romera, E.M. Editorial: Social and Personal Skills Related to Physical Education and Physical Activity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1077005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.; Jacobs, J.M.; Wright, P.M. Social and Emotional Learning Through a Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Based After-School Program for Disengaged Middle-School Boys. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2016, 35, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellison, D. Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Through Physical Activity, 3rd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Portele, C.; Jansen, P. The Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Training in an Elementary School in Germany. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gao, X.; Cui, X.; Shi, C. Associations between Physical Exercise and Social-Emotional Competence in Primary School Children. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blández-Ángel, J.; Fernández-García, E.; Sierra-Zamorano, M.A. Gender Stereotypes, Physical Activity and School: The Perspective of the Students. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2007, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating Guidance for Reporting Systematic Reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, C.M.; de Mattos, C.A.; Cuce, M.R. The PICO Strategy for the Research Question Construction and Evidence Search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peñalva-Vélez, A.; Vega-Osés, M.A.; López-Goñi, J.J. Habilidades Sociales En Alumnado de 8 a 12 Años: Perfil Diferencial En Función Del Sexo. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2020, 72, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørke, L.; Mordal Moen, K. Cooperative Learning in Physical Education: A Study of Students’ Learning Journey over 24 Lessons. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Herrero, M.D.; García Fernández, C.M.; Gil del Pino, C. Effectiveness of Educational Program in Physical Education to Promote Socio-Affective Skills and Prevent. Retos 2021, 41, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Viera, E.; Moreno-Sánchez, E.; Tornero-Quiñones, I.; Sáez-Padilla, J. Development of Emotional Intelligence through Dramatisation. Apunt. Educ. Física Deportes 2020, 143, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliziene, I.; Cizauskas, G.; Sipaviciene, S.; Aleksandraviciene, R.; Zaicenkoviene, K. Effects of a Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Emotional Well-Being among Primary School Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, K.L.; Shiver, V.N. Examination of Elementary Students’ Emotions and Personal and Social Responsibility in Physical Education. Eur. Phy Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ibáñez, D.; Fernández-Hawrylak, M. Impacto Emocional de La Actividad Física: Emociones Asociadas a La Actividad Física Competitiva y No Competitiva En Educación Primaria (Emotional Impact of Physical Activity: Emotions Associated with Competitive and Non-Competitive Physical Activity in p. Retos 2022, 45, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, T.L.; Leong, C.H.; Fede, M.; Ciotto, C. Before-School Physical Activity Program’s Impact on Social and Emotional Learning. J. Sch. Health 2022, 92, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; González-Valero, G.; Badicu, G.; Filipa-Silva, A.; Clemente, F.M.; Sarmento, H.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L. Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Body Mass Index and Emotional Intelligence in Primary Education Students—An Explanatory Model as a Function of Weekly Physical Activity. Children 2022, 9, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenanlampir, A.; Rafaty, J.; Divinubun, S.; Leasa, M. Emotional Skills with Homogeneity Psycho Cognition Strategy: A Study of Physical Education in Elementary Schools. Retos 2024, 54, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcelén-Fraile, M. del C. Active Gamification in the Emotional Well-Being and Social Skills of Primary Education Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindiani, M.; Schroeder, H.B.; Dunsky, A. Social-Emotional Learning in Physical Education Classes at Elementary Schools. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1499240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armada-Crespo, J.M. La Expresión Corporal Como Herramienta Para El Desarrollo de Habilidades Socioafectivas En El Alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Porcayo, B. Inteligencia Emocional En Niños; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Facultad de Ciencias de la Conducta: Toluca de Lerdo, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenfeld, S.; Pekrun, R.; Stupnisky, R.H.; Reiss, K.; Murayama, K. Measuring Students’ Emotions in the Early Years: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Elementary School (AEQ-ES). Learn Individ Differ 2012, 22, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; McBride, R.E.; Xiang, P. Reliability and Validity Evidence for the Social Goal Scale-Physical Education (SGS-PE) in High School Settings. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2006, 25, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and Disaffection in the Classroom: Part of a Larger Motivational Dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQLTM 4.0: Reliability and Validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in Healthy and Patient Populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, E.; Arce, C.; De Francisco, C.; Torrado, J.; Garrido, J. Versión Breve En Español Del Cuestionario POMS Para Deportistas Adultos y Poblacióngeneral. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2013, 22, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, T. Análisis de Las Variables Emocionales Enuna Intervención Didáctica de Expresión Corporal Con alumnado de Educación Primaria; Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.L.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T.P. Emotional Attention, Clarity, and Repair: Exploring Emotional Intelligence Using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure and Health; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Cabello, R.; Castillo, R.; Extremera, N. Gender Differences in Emotional Intelligence: The Mediating Effect of Age. Behav. Psychol. 2012, 20, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, T.; Haeussler, I.; Torretti, A. TAE: Batería de Test de Autoestima Escolar; Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile: Santigao, Chile, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Matson, J.L.; Rotatori, A.F.; Helsel, W.J. Development of a Rating Scale to Measure Social Skills in Children: The Matson Evaluation of Social Skills with Youngsters (MESSY). Behav. Res. Ther. 1983, 21, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, F.; Hidalgo, M.; Inglés, C.J. The Matson Evaluation of Social Skills with Youngsters: Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Translation in the Adolescent Population. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2002, 18, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Herrero, M. Práctica de La Expresión Corporal En El Área de Educación Física En La Etapa de Educación Primaria. Repercusiones Positivas Hacia Una Escuela Inclusiva; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; Gray, S.; Richards, K.A.R. Understanding the Interpretation and Implementation of Social and Emotional Learning in Physical Education. Curric. J. 2021, 32, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).