Abstract

Background/Objectives: Frequent users (FUs) are patients who repeatedly attend Emergency Departments (EDs). This study aims to identify the clinical and social characteristics of FUs in a Local Health Authority in Rome and to quantify and compare the variation in the probability of being FU attributable to General Practitioners (GPs) and Local Health Districts (LHDs). Methods: The Healthcare Emergency Information System and an automated database of Lazio Region residents were used for the collection of data on the patients’ socioeconomic status, GP, LHD and chronic diseases. Different FU thresholds (attendances ≥4, 5, 7 or 10) were used for descriptive analyses. Univariate logistic analysis and a multilevel logistic model were performed for inferential analyses. Results: A total of 89,036 individuals attended at least one of the 13 EDs included in the study. Mental illness was present in 2.6% of non-FUs compared with 7.6% of FUs with ≥4 attendances. The OR of being FU increased with higher clinical complexity. GP appeared to play an important role in determining FU behavior, while no significant effect was found on the LHD level. Conclusions: This study identified potential risk factors predictive of disproportionate ED use and may help policymakers address the FU phenomenon.

1. Introduction

The Italian population, like other OECD countries, has experienced an increase in chronic illnesses over the past few decades, with population aging being one of the primary drivers [1]. Despite significant improvements in the emergency care system, the growing number of frail patients and their care needs have led to a rise in Emergency Department (ED) attendance [2,3]. In hospitals with limited inpatient bed capacity, increasing ED attendances and the number of emergency patients requiring admission may increase the length of stay in the ED, leading to overcrowding and compromised ED performance, as well as to the increase of inappropriate hospitalizations and health care costs. Reducing ED utilization has therefore become a crucial goal for new healthcare delivery models [4,5,6]. However, the predictors of ED attendance are complex and multifactorial [7].

There is no single definition of Frequent Users (FUs), and it depends on the length of observation time. Frequent Users are patients with at least four ED attendances per year, as defined in most of the literature [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Although they account for only 4.5–8% of ED patients, they are responsible for up to 28% of all ED attendances [10,14]. Excessive ED use raises two major concerns: the first is associated with additional ED costs, which often exceed the government’s budgetary limits, particularly since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic [15,16,17]; the second is compromising the quality of services provided to patients with acute conditions requiring appropriate ED attendance. Furthermore, it contributes to overcrowding and increases the likelihood of medical errors [8,9,18].

Previous research has highlighted that FUs are more likely to have chronic conditions (particularly renal failure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic pulmonary disease), mental illness or substance use disorders [19,20]. The prevalence of chronic conditions is higher among FUs than in the general population, and timely interventions in primary care could help prevent ED attendances and hospitalization [21,22]. A growing body of evidence reveals that FUs frequently use other healthcare services (other than the ED), are more often of lower socioeconomic status, and experience health outcomes strongly influenced by their residential context [19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

As in other countries, Italy has recently focused on improving care coordination and reducing ED attendance and hospital admissions by promoting more appropriate use of community-based services [28]. Compared with other European contexts, a relatively high proportion of Italians report that they have unmet medical needs, and access to care is particularly difficult for those of lower socioeconomic status [29].

Analyzing the socioeconomic profile and the geographic variation in ED use may therefore be an essential first step in guiding local policies in reducing avoidable emergency department attendances in Italy [30].

According to the literature, the prevalence of health problems is a key determinant in ED attendance frequency. Nevertheless, other factors have also been associated with high levels of ED attendance [31,32,33,34], especially in urban peripheries and inner-city areas, such as housing and employment problems, loneliness and marginalization, limited social support, proximity to the ED, and poor access to primary care [35,36,37].

Moving from macro-level analyses to more granular units such as census tracts makes it possible to identify local hotspots of high healthcare utilization and to highlight contextual factors affecting specific populations and communities. This approach provides insight into how interventions can be geographically targeted to improve healthcare delivery [38].

The aim of this study is to identify the clinical and social characteristics of FUs and to quantify and compare the variation in the probability of being FU attributable to GPs and Local Health Districts (LHDs), while also assessing socio-economic status and chronic conditions. The findings obtained by this combination of both individual and population level data may support policymakers and healthcare providers in developing care coordination programs and strategies, with the ultimate goal of addressing social and territorial inequalities in healthcare access, reducing avoidable ED usage, and encouraging a more appropriate usage of preventative and primary care opportunities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was carried out in Local Health Authority (LHA) Roma 1 (see Appendix A), one of the three LHAs in the municipality of Rome, in the Lazio Region. It comprises six Local Health Districts (LHD 1, LHD 2, LHD 3, LHD 13, LHD 14, LHD 15) and 805 General Practitioners (GPs), and serves approximately one million residents.

While LHA Roma 1 is not fully representative of the entire Italian or Regional setting, it is one of the most populous areas in Italy, with 13 EDs (out of the 22 in the Rome metropolitan area), an aging index (population aged 65+ divided by those aged 0–14, per 100) of 202 in 2024 (compared with a regional mean of 189) and an old-age dependency ratio (population aged 65+ divided by population in the working age 15–64) of 38.1 in 2024 [39]. This retrospective cohort study included all ED attendances from 1 January 2021, to 31 December 2021, in all 13 Emergency Departments within LHA Roma 1. All patients assisted by a GP from the same LHA were enrolled in the cohort. Patients younger than 18 years and those who attended single-specialty EDs (ophthalmology, pediatrics) and attendances for obstetric or gynecological problems were excluded since they represent a population with specific needs that is worthy of specific focus and not comparable with the general population.

FUs were defined as patients with ≥4 ED attendances per year Given the absence of a universal definition, different cut-offs (attendances ≥5, 7 or 10) were also considered in the descriptive analysis.

For each patient in the cohort the following potential risk factors were assessed: gender, age, socioeconomic status (high, middle-high, medium, middle-low, low) and the presence of chronic or multiple-chronic conditions [40,41]. The socioeconomic level was calculated at the census tract level, based on the methodology developed by Nicola Caranci and colleagues [42]. This index integrates multiple socio-economic indicators derived from national census data, including educational attainment, employment status, home ownership versus rental, household overcrowding, and family structure. It provides a composite measure of socio-economic disadvantage within small geographic areas. Among patients with multiple chronic conditions, high clinical complexity was defined as a five-year mortality risk higher than 10%, based on the number and type of chronic diseases [43].

Data related to ED attendances were also compared to identify differences between FUs and non-FUs. In particular, triage score, principal diagnosis group in the ED, and reported symptoms at the time of arrival were considered.

2.2. Data Sources

The cohort was derived from the Healthcare Emergency Information System, which collects all attendances to emergency services, patient demographic data, visit and discharge dates and times, ICD-9-CM diagnosis, reported symptoms on attendance, triage score (from no urgent to emergency), and discharge status (e.g., dead, hospitalized, or discharged at home).

The cohort was linked to the automated databases of Lazio Region residents who receive NHS assistance, thus allowing researchers to obtain information related to chronic or multiple chronic diseases, GP and LHD of each patient, and socioeconomic status based on the residence address [42,44,45]. A deterministic record linkage procedure with anonymous identification codes was used to merge the data from different information systems. To preserve privacy, each individual identification code was subsequently and automatically deidentified, and the conversion table was deleted, leaving only fully anonymized data available to researchers.

2.3. Geographical Analysis

The administrative-territorial division of the LHA Roma 1 was used to examine the association between FU prevalence and urban settings, as previously described [46]. Each of the six LHDs of LHA Roma 1 is divided into Geographical Units (GUs, in Italy called “Zone Urbanistiche”), as defined by the Municipality of Rome. This represent the smallest territorial unit for which population data are available in Italy and many other countries [47,48].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The outcome variable was binary (FU ≥ 4 vs. non-FU). Frequency distributions of FUs (attendances ≥ 4, 5, 7 and 10) by triage, principal diagnosis and presenting symptoms at ED arrival were compared with those of non-FU. A descriptive analysis was performed reporting absolute frequencies of patient groups and ED attendances characteristics. Univariate logistic analysis was used to identify candidate predictor variables among those collected in the dataset. A multilevel logistic model (patient < GP < District) was performed to quantify the variability in ED FU behavior attributable to LHDs and primary care physicians and to identify the role of social and clinical determinants (gender, age, socioeconomic level and chronic conditions).

Age was considered as a continuous variable. The Box-Tidwell test was used to check for linearity between the “predictor” and the logit. The effect of individual variables was expressed as Odds Ratios (OR); variance components estimated by multilevel models were expressed as Median Odds Ratios (MORs). The MOR quantifies between-cluster variation by comparing two patients from two randomly chosen, different clusters. Consider two persons with the same covariates, chosen randomly from two different clusters. The MOR represents the median odds ratio between the person of higher propensity and the person of lower propensity. MOR values are always ≥1.00; if MOR = 1.00, there is no variation between clusters, while larger values indicate greater variation [49]. MORs were estimated for both the “empty” model, which includes a random intercept only, and the full model, which includes all patient risk factors. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software 9.4 version (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

A total of 89,036 patients accessed at least one of the 13 EDs in LHA Roma 1 during 2021. Patients and ED attendances characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. A total of 72,781 patients were registered with a GP in LHA Roma 1. Overall, patients accounted for 99.811 attendances. FUs represented a small fraction of the overall population (2.7%) but were responsible for a large share of attendance (11.3%). Among non-FUs, females accounted for 51.9%, while males were more frequent among FUs (ranging from 51.9% in FU ≥ 5 to 57.7% in FU ≥ 10) than among non-FUs (48.1%). The 50–59 age group was the most frequent among non-FUs (18.4%) and FU ≥ 4 (17.5%), and its proportion increased with the number of FU attendances. Low socioeconomic status was prevalent among most FUs (from 25.3% of FU ≥ 4 to 24.6% of FU ≥ 10), whereas high and medium-high levels were more frequent among non-FUs. Multiple chronic conditions were present in 29.4% of FU ≥ 4 patients, whereas 47.6% of FU ≥ 4 patients had no chronic disorders recorded.

Table 1.

Characteristics of FU and non-FU patients in 2021.

Table 2.

Characteristics of ED attendances of FU and non-FU patients in 2021.

Table 2 was constructed after classifying patients according to the number of ED attendances. Emergency and urgent triage codes decreased from 24.9% in the FU ≥ 4 group to 20.9% in the FU ≥ 10 group. Conversely, non-urgent codes increased from 8.1% in the FU ≥ 4 group to 14.4% in the FU ≥ 10 group. The most frequent diagnoses among all patients fell into the category of “Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions”. Mental disorders were recorded in 2.6% of the non-FU group but increased from 7.6% in the FU ≥ 4 group to 15.9% in the FU ≥ 10 group. Cardiovascular diseases were similar in the non-FU and FU ≥ 4 groups (8.6% and 8.2%, respectively). Excluding nonspecific and missing diagnoses, many acute conditions (e.g., trauma, abdominal and chest pain, dyspnea) decreased in frequency from the non-FU group to the FU ≥ 10 group. In contrast, psychomotor agitation increased from 5.1% in the FU ≥ 4 group to 11.2% in the FU ≥ 10 group. Social issues were reported in 0.4% of diagnoses in the FU ≥ 4 group and 0.9% in the FU ≥ 10 group, whereas none were reported in the non-FU group.

3.2. Geographical Distribution

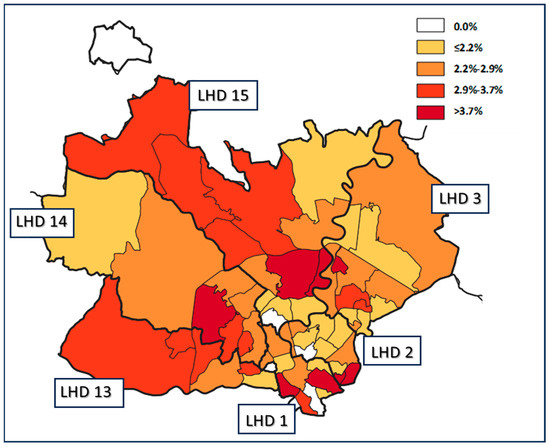

The geographical classification included two levels: GUs and LHDs. For each level, five classes were defined based on the relative percentage of FUs in the area. The geographical distribution shown in Figure 1 indicates that some areas of LHA Roma 1 had a significantly higher percentage of FUs, particularly in LHD 1, LHD 14 and LHD 15.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of FUs. Colors represent the five percentage cut-off groups of FUs at the Geographical Unit population level. The bold black line delineates the six LHDs, while the thin black line delineates the Geographical Units.

3.3. Inferential Analysis

Results of the multilevel analysis are reported in Table 3. Among candidate predictor variables identified in the descriptive and geographical analyses, the strongest effect was associated with the presence of multiple chronic conditions: the greater the patient’s clinical complexity, the higher the OR of being a FU. OR increased with decreasing socioeconomic status, with a more pronounced effect for low and medium-low levels and a less consistent effect for higher levels. The role of GP did not show a consistent influence on FU behavior (MOR 1.18, Wald p = 0.061), and no significant effect was observed at the LHD level (MOR 1.05, Wald p = 0.127).

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression model predicting ED frequent usage.

4. Discussion

FUs represented 2.7% of the overall population but were accounted for 11.3% of attendances in 2021, in line with the literature [46], most frequently in the 50–59 age group. The risk of being FU increased with the patient’s clinical complexity and with low and medium-low socioeconomic status. Generally, patients with higher socioeconomic status were less likely to attend the ED. This is consistent with a study conducted in Milan, where the odds of avoidable hospital admissions were higher among patients with lower socioeconomic status compared with other groups [50]. Prior studies suggest that patients with low socioeconomic level perceive ED assistance to be cheaper and more accessible than ambulatory care and are often more likely to use EDs for nonurgent conditions [33,49,51].

In this study, non-urgent triage codes were more frequent among FUs (from 8.1% in the FU ≥ 4 group to 14.4% in the FU ≥ 10 group), and mental disorders were common in a substantial proportion of FUs (to 15.9% in the FU ≥ 10 group). Psychomotor agitation and social issues were important diagnoses associated with FUs, but the results of “symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions” and “external causes of injury and supplemental classification” diagnosis groups, as well as the main issues on admission, such as fever, chest pain or dyspnea, may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. This may also have affected time-dependent conditions such as stroke or cardiac complaints, possibly due to concerns about acquiring COVID-19 in hospital [52,53]. However, all patients included in the analysis (those with at least one ED visit in 2021) were equally exposed to the pandemic waves, and no systematic differences were expected between subgroups that could have introduced bias. Furthermore, other studies in the Lazio Region comparing ED attendances during the COVID-19 waves found a sharp reduction in ED attendances, except for pneumonia [54]. The increase of physical and mental morbidities was associated with higher ED attendance rates, supporting previous evidence that individuals with chronic diseases and psychiatric disorders are more likely to attend EDs [19,55]. This also applies to individuals with socioeconomic deprivation [31,56]. Across the EU, admissions related to chronic and psychiatric disorders are estimated to be potentially avoidable through improved prevention and disease management, which could reduce reliance on EDs [57,58]. Some authors have investigated the importance of social support for older adults in the ED, although in a systematic review there was no significant association between ED attendance and social support [59].

Regarding the geographical analysis shown in Figure 1, this study characterized variation using more granular geographic unit of analysis. This may be considered a first step toward developing specific public health strategies aimed at improving appropriate healthcare utilization for specific populations and communities, as implemented in Paris by the Île-de-France Regional Health Agency [46]. In other studies on geographic variation in healthcare, utilization and outcomes were quantified by using geographic macro-areas, but it was impossible to distinguish a single neighborhood characterized by different socioeconomic and demographic characteristics [30,50,60,61]. Further studies are needed to analyze the association among FUs, population density, income and medical services or GP offices in the same area.

The multilevel analysis indicated that GPs did not play a consistent role in avoiding FU behaviors (MOR 1.18, Wald p = 0.061), similar to findings at the territorial level (LHDs). It is possible that FUs bypass GPs to obtain quicker treatment. In some studies, reductions in ED demand were associated with the availability of at-home GP visits or improved public transportation [62]. Other authors have reported that frequent ED users also have high rates of GP consultations and outpatient care in addition to ED use. Therefore, efforts to simply increase access to primary care or extend GP opening hours (weekdays and weekends) may not necessarily reduce ED utilization [63].

Primary prevention of the FU phenomenon has been little discussed in the literature. These FU subpopulations may represent distinct targets for interventions, such as tailored individual action plans [64]. Individual care plans for FUs are often based on secondary prevention, initiated after an ED attendance and followed by intervention or case management [65]. Policies should focus on comprehensive patient and family care, considering hospital and territorial services, consistently combining medical and social dimensions [66].

Coordinated, team-based approaches integrating medical, behavioral, and care management services have been recognized as a cost-effective model to reduce ED attendances and combined ED and inpatient hospital costs among patients with complex care needs, even those who report access to traditional primary care. The case management approach is a tool that can be applied in different ways and contexts [66,67].

Two systematic reviews showed that compared with standardized methods, a customized case management approach helps FUs find appropriate responses to their needs. The main tool used is the individual care plan with phone contact, supportive group therapy and electronic systems for rapid patient identification. Teams are heterogeneous, although nurses are often the most frequently involved professionals [68].

High rates of FU-related ED attendances may also reflect poverty in metropolitan areas and highlight social inequalities in healthcare access. As emphasized in the New Urban Agenda, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals promote health through several interconnected health-related targets, achievable via multisectoral approaches [69]. Thus, reducing FU rates and improving the health status of the general population may be achieved through joint policies with other partners, such as schools or transportation agencies [70,71,72].

Limitations and Strengths

This study represents the most comprehensive analysis in a single metropolitan area in Italy including all FU attendances over one year and considering their health status, socioeconomic determinants, and geographical distribution. Although these findings are not generalizable to the entire population, they are relevant to many urban areas with similar levels of social deprivation. Therefore, institutions and healthcare providers may be able to identify territories where residents are at higher risk of developing FU patterns and to suggest primary prevention measures. Access to regional data flows minimized the risk of missing records or information. Moreover, residents living in extremely disadvantaged circumstances were likely captured in our data due to the fictitious address assigned to them by the LHA.

This study has some limitations. The retrospective design allowed investigation of the predictors of ED attendance only at a single point in time and exclusively among LHA residents, thereby excluding homeless individuals without residency, foreigners, and people formally resident in LHA Roma 1 but whose healthcare services were provided by other LHAs in Rome. Only the main diagnosis was considered, and inaccuracies in the clinical dataset may have led to underreporting of some morbidities. The potential influence of proximity to EDs and primary care services on ED attendance was not evaluated. Additional variables would be necessary to quantify COVID-19-specific attendance, to better understand their influence on the results.

5. Conclusions

The results might not be generalizable to the Italian context, but they are extremely relevant to metropolitan areas with similar socio-demographic composition, as is the case for many major Italian and European cities.

Frequent ED use represents a major challenge for healthcare system management. Analysis of ED attendances and the socioeconomic and geographical characteristics of FUs highlights the need for new approaches to address key issues such as socioeconomic inequalities, improvement of housing and employment conditions, and structural factors including the strategic placement of primary care services and improved transportation.

This study enabled the identification of potential risk factors predictive of disproportionate ED use and supports policymakers in anticipating the needs of specific patient groups or categories. Further studies are warranted to examine the prevalence of FUs and the geographical distribution of hospitals, residents’ income and primary care services across the entire Lazio Region. It would also be useful to investigate the effectiveness of territorial interventions, in line with the new directives of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan for chronic disease management at the territorial level.

Author Contributions

G.F., A.V., P.P. and C.D.V. conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. F.M., M.D.M. and M.D. designed the data collection instruments, collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. A.B., P.L. and G.D. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. M.D. and M.M. coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Lazio 1 Ethical Committee (protocol code 238/CE Lazio 1, 9 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ED | Emergency Department |

| FU | Frequent User |

| LHD | Local Health District |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| LHA | Local Health Authority |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| GU | Geographical Unit |

| OR | Odds Ratios |

| MOR | Median Odds Ratios |

Appendix A. Italian National Health Service

The Italian National Health Service (NHS) is structured on three levels: the first includes the Central Government and the Ministry of Health, the second comprises the twenty Regional Governments and the third consists of the Local Health Authorities (LHAs) together with independent hospitals. The NHS is primarily funded through public taxation and is guided by the principles of universal coverage, solidarity, and human dignity. Each LHA includes at least one non-independent hospital and one or more Local Health Districts (LHDs), which provide primary care services (vaccination and screening, specialist consultations, family planning counselling, home care) and coordinates General Practitioners (GPs) and Primary Care Paediatricians (PCPs). Primary care physicians may work individually or in operational and multidisciplinary associations to ensure full access to care, 24 h a day, 7 days a week.

References

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policy. Italy: Country Health Profile 2017; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, G.; Gugiatti, A.; Meda, F.; Petracca, F. La struttura e le attività del SSN. In Rapporto OASI 2020; CERGAS-Bocconi; Egea: Milan, Italy, 2020; pp. 37–115. [Google Scholar]

- Carle, F.; Franchino, G.; Bruno, V. Osservatorio della Salute delle Regioni Italiane. Assistenza Ospedaliera. In Rapporto Osservasalute 2021; Com Publishing: Rome, Italy, 2022; pp. 517–581. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.C.; Doran, K.M.; Polsky, D.; Cordova, E.; Carr, B.G. Geographic variation in the demand for emergency care: A local population-level analysis. Healthcare 2016, 4, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, R.J.; Johnson, E.A.; Hsu, C.; Ehrlich, K.; Coleman, K.; Trescott, C.; Erikson, M.; Ross, T.R.; Liss, D.T.; Cromp, D.; et al. Spreading a medical home redesign: Effects on emergency department use and hospital admissions. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulowitz, P.B.; Honigman, L.; Landon, B.E. A novel approach to identifying targets for cost reduction in the emergency department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013, 61, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, I.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Dubuc, N.; Beaudin, J.; Lafontaine, S.; Hudon, C. Factors associated with frequent use of emergency-department services in a geriatric population: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, S.; Gialloreti, L.E.; Riccardi, F.; Scarcella, P.; Liotta, G. Predictors of emergency room access and not urgent emergency room access by the frail older adults. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 721634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.M.; Dufour, I.; Courteau, J.; Vanasse, A.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Dubois, M.-F.; Dubuc, N.; Elazhary, N.; Hudon, C. Profiles of frequent emergency department users with chronic conditions: A latent class analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, J.; Kirkland, S.W.; Rawe, E.; Ospina, M.B.; Vandermeer, B.; Campbell, S.; Rowe, B.H. Effectiveness of interventions to decrease emergency department visits by adult frequent users: A systematic review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2017, 24, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCalle, E.; Rabin, E. Frequent users of emergency departments: The myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010, 56, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legramante, J.M.; Morciano, L.; Lucaroni, F.; Gilardi, F.; Caredda, E.; Pesaresi, A.; Coscia, M.; Orlando, S.; Brandi, A.; Giovagnoli, G.; et al. Frequent use of emergency departments by the elderly population when continuing care is not well established. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furia, G.; Vinci, A.; Colamesta, V.; Papini, P.; Grossi, A.; Cammalleri, V.; Chierchini, P.; Maurici, M.; Damiani, G.; De Vito, C. Appropriateness of frequent use of emergency departments: A retrospective analysis in Rome, Italy. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1150511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrega, J.G.; Hermes, C.; König, V.; Kitz, V.; Möller, S.; Stark, D.; Janssens, U.; Mager, D.; Kochanek, M. Sustainability in intensive and emergency care: A nationwide survey by the German Society of Medical Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Med. Klin. Intensiv. Notfmed. 2023, 119, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Rosiello, F.; Alessi, E.; Pascucci, M.; Rainone, M.; Cipriano, E.; Di Berardino, A.; Vinci, A.; Ruggeri, M.; Ricci, S. Burden of COVID-19 on Italian Internal Medicine Wards: Delphi, SWOT, and performance analysis after two pandemic waves in the Local Health Authority “Roma 6” Hospital structures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armocida, B.; Formenti, B.; Ussai, S.; Palestra, F.; Missoni, E. The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruster, L.; van der Zee, D.-J.; Buskens, E. Identifying frequent health care users and care consumption patterns: Process mining of emergency medical services data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieg, C.; Hudon, C.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Dufour, I. Individual predictors of frequent emergency department use: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Bella, E.; Gandullia, L.; Leporatti, L.; Locatelli, W.; Montefiori, M.; Persico, L.; Zanetti, R. Frequent use of emergency departments and chronic conditions in ageing societies: A retrospective analysis based in Italy. Popul. Health Metr. 2020, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, O.R.; Segal, L.; McDermott, R.A. A systematic review of evidence on the association between hospitalisation for chronic disease related ambulatory care sensitive conditions and primary health care resourcing. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcusky, M.; Singer, D.; Keith, S.W.; Hegarty, S.E.; Lombardi, M.; Saccenti, E.; Maio, V. Evaluation of care processes and health care utilization in newly implemented medical homes in Italy: A population-based cross-sectional study. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2020, 35, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Santana, P.; Dimitroulopoulou, S.; Burström, B.; Borrell, C.; Schweikart, J.; Dzúrová, D.; Zangarini, N.; Katsouyanni, K.; Deboosere, P.; et al. Population Health Inequalities Across and Within European Metropolitan Areas through the Lens of the EURO-HEALTHY Population Health Index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, C.; Pons-Vigués, M.; Morrison, J.; Díez, È. Factors and processes influencing health inequalities in urban areas. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsakou, C.; Dimitroulopoulou, S.; Heaviside, C.; Katsouyanni, K.; Samoli, E.; Rodopoulou, S.; Costa, C.; Almendra, R.; Santana, P.; Dell’OLmo, M.M.; et al. Environmental public health risks in European metropolitan areas within the EURO-HEALTHY project. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, P.; Costa, C.; Cardoso, G.; Loureiro, A.; Ferrão, J. Suicide in Portugal: Spatial determinants in a context of economic crisis. Health Place 2015, 35, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, M.; Giancotti, M. The 2022 primary care reform in Italy: Improving continuity and reducing regional disparities? Health Policy 2023, 135, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matranga, D.; Maniscalco, L. Inequality in Healthcare Utilization in Italy: How Important Are Barriers to Access? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilheimer, L.T. Evaluating metrics to improve population health. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A69. [Google Scholar]

- Giebel, C.; McIntyre, J.C.; Daras, K.; Gabbay, M.; Downing, J.; Pirmohamed, M.; Walker, F.; Sawicki, W.; Alfirevic, A.; Barr, B. What are the social predictors of accident and emergency attendance in disadvantaged neighbourhoods? Results from a cross-sectional household health survey in the north west of England. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scantlebury, R.; Rowlands, G.; Durbaba, S.; Schofield, P.; Sidhu, K.; Ashworth, M. Socioeconomic deprivation and accident and emergency attendances: Cross-sectional analysis of general practices in England. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e649–e654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.A.; Jones, I.R.; Moser, K. Factors influencing the attendance rate at accident and emergency departments in East London: The contributions of practice organization, population characteristics and distance. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 1997, 2, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudge, G.M.; Mohammed, M.A.; Fillingham, S.C.; Girling, A.; Sidhu, K.; Stevens, A.J. The combined influence of distance and neighbourhood deprivation on Emergency Department attendance in a large English population: A retrospective database study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, P.Y.; Ryu, E.; Hathcock, M.A.; Olson, J.E.; Bielinski, S.J.; Cerhan, J.R.; Rand-Weaver, J.; Juhn, Y.J. A novel housing-based socioeconomic measure predicts hospitalisation and multiple chronic conditions in a community population. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.; Costa, C.; Almendra, R.; Freitas, Â.; Santana, P. The socio-spatial context as a risk factor for hospitalization due to mental illness in the metropolitan areas of Portugal. Cad. Saude Publica 2015, 31 (Suppl. S1), 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Borsboom, G.; Saez, M.; Dell’olmo, M.M.; Burström, B.; Corman, D.; Costa, C.; Deboosere, P.; Domínguez-Berjón, M.F.; Dzúrová, D.; et al. Social differences in avoidable mortality between small areas of 15 European cities: An ecological study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsens, M.; Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Pérez, K.; Palència, L.; Martinez-Beneito, M.-A.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Burström, B.; Costa, G.; Deboosere, P.; Domínguez-Berjón, F.; et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in injury mortality in small areas of 15 European cities. Health Place 2013, 24, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolasco, A.; Moncho, J.; Quesada, J.A.; Melchor, I.; Pereyra-Zamora, P.; Tamayo-Fonseca, N.; Martínez-Beneito, M.A.; Zurriaga, O.; Ballesta, M.; Daponte, A.; et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in preventable mortality in urban areas of 33 Spanish cities, 1996–2007 (MEDEA project). Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Salute Lazio. Dati sullo Stato di Salute della Popolazione Residente nella Regione Lazio. 2023. Available online: https://www.opensalutelazio.it/salute/stato_salute.php?stato_salute (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Pines, J.M.; Asplin, B.R.; Kaji, A.H.; Lowe, R.A.; Magid, D.J.; Raven, M.; Weber, E.J.; Yealy, D.M. Frequent users of emergency department services: Gaps in knowledge and a proposed research agenda. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011, 18, e64–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, L.E.; Cochran, T.; Frey, J.A.; Stiffler, K.A.; Wilber, S.T. Emergency department use and barriers to wellness: A survey of emergency department frequent users. BMC Emerg. Med. 2017, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosano, A.; Pacelli, B.; Zengarini, N.; Costa, G.; Cislaghi, C.; Caranci, N. Update and review of the 2011 Italian deprivation index calculated at the census section level. Epidemiol. Prev. 2020, 44, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrao, G.; Rea, F.; Di Martino, M.; De Palma, R.; Scondotto, S.; Fusco, D.; Lallo, A.; Belotti, L.M.B.; Ferrante, M.; Addario, S.P.; et al. Developing and validating a novel multisource comorbidity score from administrative data: A large population-based cohort study from Italy. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e019503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Martino, M.; Furfaro, S.; Mulas, M.F.; Mataloni, F.; Santurri, M.; Paris, A.; Maritati, A. Population segmentation as a tool for planning community healthcare networks: The key role of social and health information systems. Recenti Prog. Med. 2022, 113, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataloni, F.; Bauleo, L.; Badaloni, C.; Nobile, F.; Savastano, J.; Noccioli, F.; Salatino, C.G.; Balducci, M.; Cappai, G.; Rosa, A.C.; et al. Geocoding one million of addresses using API: A semiautomatic multistep procedure. Epidemiol. Prev. 2022, 46, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, R.; Feral-Pierssens, A.-L.; Michault, A.; Casalino, E.; Ricard-Hibon, A.; Adnet, F.; Brun-Ney, D.; Bouzid, D.; Menu, A.; Wargon, M. The analysis of the geographical distribution of emergency departments’ frequent users: A tool to prioritize public health policies? BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma Capitale-Territorio. Zone Urbanistiche. 2023. Available online: https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/Territorio_RomaCapitale.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Domínguez-Berjón, M.F.; Borrell, C.; López, R.; Pastor, V. Mortality and socioeconomic deprivation in census tracts of an urban setting in southern Europe. J. Urban Health 2005, 82, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Kangovi, S.; Barg, F.K.; Carter, T.; Long, J.A.; Shannon, R.; Grande, D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongiglione, B.; Torbica, A.; Gusmano, M.K. Inequalities in avoidable hospitalisation in large urban areas: Retrospective observational study in the metropolitan area of Milan. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Sung, J.H.; Ward, W.B.; Fos, P.J.; Lee, W.J.; Kim, J.C. Utilization of the emergency room: Impact of geographic distance. Geospat. Health 2007, 1, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucero, A.D.; Lee, A.; Hyun, J.; Lee, C.; Kahwaji, C.; Miller, G.; Neeki, M.; Tamayo-Sarver, J.; Pan, L. Underutilization of the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschen, M.E.; Bowen, J.; Novak, A.; Giles, M.; Singh, S.; Lasserson, D.; O’Callaghan, C.A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department attendances and acute medical admissions. BMC Emerg. Med. 2021, 21, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnarelli, L.; Colais, P.; Mataloni, F.; Cascini, S.; Fusco, D.; Farchi, S.; Polo, A.; Lacalamita, M.; Spiga, G.; Ribaldi, S.; et al. Access to the Emergency Department in the time of COVID-19: An analysis of the first three months in the Lazio Region (Central Italy). Epidemiol. Prev. 2020, 44, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.H.; Grinspan, Z.; Shapiro, J.; Rhee, S.Y. Frequent Users of hospital Emergency Departments in Korea characterized by claims data from the National Health Insurance: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Or, Z.; Penneau, A. A multilevel analysis of the determinants of emergency care visits by the elderly in France. Health Policy 2018, 122, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinton, D.T.; Capp, R.; Rooks, S.P.; Abbott, J.T.; Ginde, A.A. Frequent users of US emergency departments: Characteristics and opportunities for intervention. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Moore, D.C.; Barron, L.; Stow, D.; Hanratty, B. Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, G.; Georgescu, V.; Bousquet, J. Geographic variation in potentially avoidable hospitalizations in France. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, Â.; Rodrigues, T.C.; Santana, P. Assessing urban health inequities through a multidimensional and participatory framework: Evidence from the EU-RO-HEALTHY Project. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, S.A.; Homer, K.; Boomla, K.; Robson, J.; Ashworth, M. Population and patient factors affecting emergency department attendance in London: Retrospective cohort analysis of linked primary and secondary care records. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e157–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Heede, K.; Van de Voorde, C. Interventions to reduce emergency department utilisation: A review of reviews. Health Policy 2016, 120, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaria, H.K.; Niedzwiecki, M.J.; Montoy, J.C.; Raven, M.C.; Hsia, R.Y. Persistent frequent emergency department use: Core Group exhibits extreme levels of use for more than a decade. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, F.; Daeppen, J.-B.; Hugli, O.; Iglesias, K.; Stucki, S.; Paroz, S.; Allen, M.C.; Bodenmann, P. Screening of mental health and substance users in frequent users of a general Swiss emergency department. BMC Emerg. Med. 2015, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, S.; Collins, L.; Hall, J.; Rochester, D.; Patch, S. Reducing utilization by uninsured frequent users of the emergency department: Combining case management and drop-in group medical appointments. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2012, 25, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, R.; Di Silvio, V.; Bosco, P.; Laquintana, D.; Galazzi, A. Case management programs in emergency department to reduce frequent user visits: A systematic review. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus, F.; Paroz, S.; Hugli, O.; Ghali, W.A.; Daeppen, J.B.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Bodenmann, P. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: A systematic review. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2011, 58, 41–52.e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Bell, R. The Sustainable Development Goals and Health Equity. Epidemiology 2018, 29, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellena, M.; Ballester, J.; Mercogliano, P.; Ferracin, E.; Barbato, G.; Costa, G.; Ingole, V. Social inequalities in heat-attributable mortality in the city of Turin, northwest of Italy: A time series analysis from 1982 to 2018. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheshire, J. Featured Graphic. Lives on the line: Mapping life expectancy along the London Tube network. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2012, 44, 1525–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsatakis, A.; Ostergren, P.-O.; Webster, P. Tackling the social determinants of inequalities in health during phase V of the Healthy Cities Project in Europe. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, i45–i53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).