Healthcare Providers’ Perspectives on the Involvement of Mental Health Providers in Chronic Pain Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

2.3. Questionnaire Preparation

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Ethical Statement

2.6. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.7. Data Screening and Assumption Checks

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Correlation Between Key Domains

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

3.4. Regression Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications and Recommendations

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

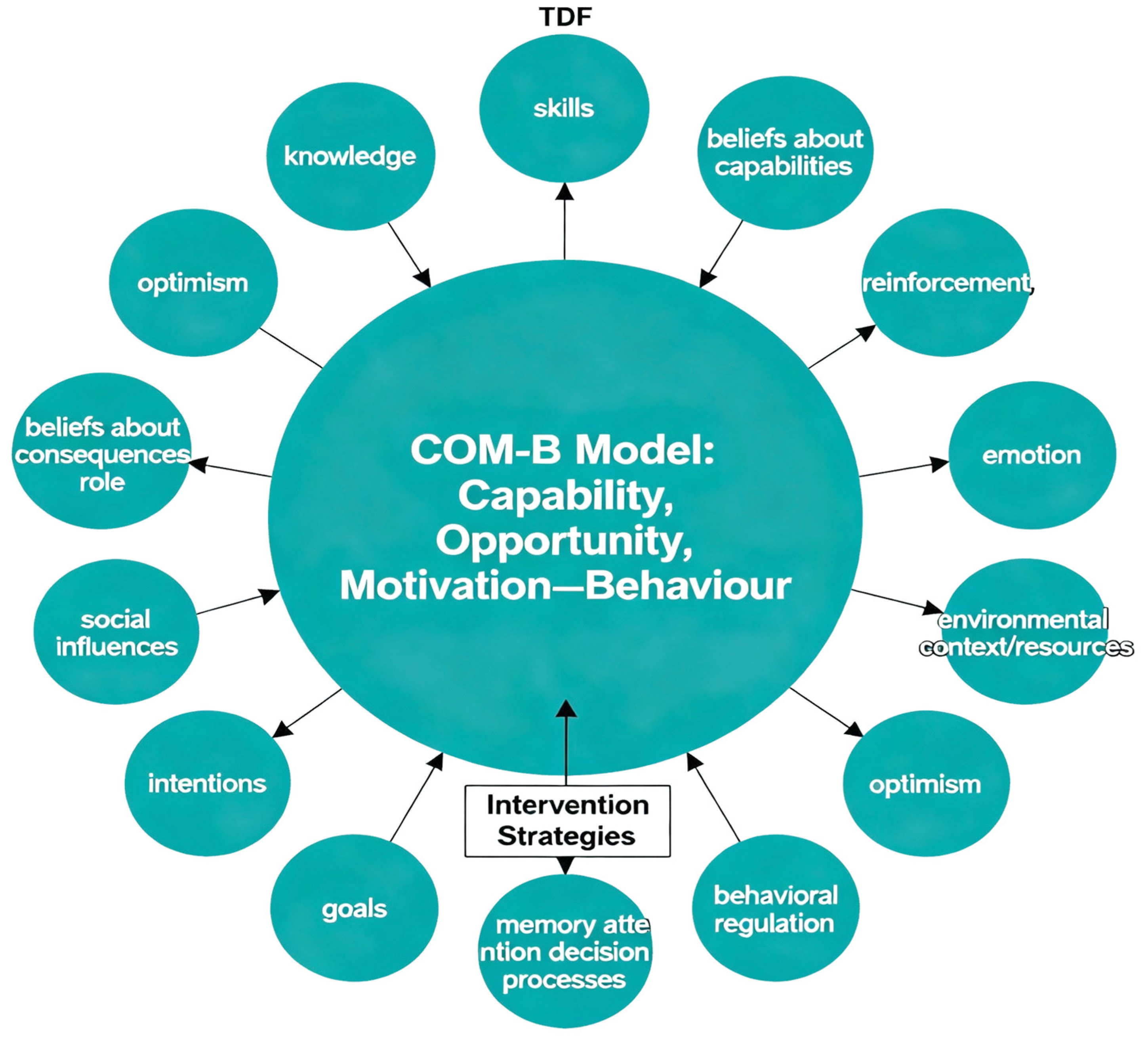

| BCW | Behaviour Change Wheel |

| CNMP | Chronic non-malignant pain |

| CCM | Collaborative Care Management |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour |

| TDF | Theoretical Domains Framework |

References

- Guven Kose, S.; Kose, H.C.; Celikel, F.; Tulgar, S.; De Cassai, A.; Akkaya, O.T.; Hernandez, N. Chronic Pain: An Update of Clinical Practices and Advances in Chronic Pain Management. Eurasian J. Med. 2022, 54, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, J.S.; Brady, B.R.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Herder, K.E.; Wallace, J.S.; Padilla, A.R.; Vanderah, T.W. Co-occurrence of chronic pain and anxiety/depression symptoms in U.S. adults: Prevalence, functional impacts, and opportunities. PAIN 2024, 165, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, M.T.; BinBaz, S.S.; Alamri, S.S.; Alghamdi, H.H.; El-Kabbani, A.O.; Al Mulhem, A.A.; Alzubaidi, S.A.; Altowairqi, A.T.; Alrbeeai, H.A.; Alharthi, W.M.; et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharbi, S.; Abolkhair, A.; Ghamdi, H.; Haddara, M.; Valtysson, B.; Tolba, Y.; Alaujan, R.; Abu-Khait, S. Prevalence of opioid misuse, abuse and dependence among chronic pain patients on opioids followed in chronic pain clinic in a tertiary care hospital Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Hamdan Med. J. 2018, 12, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.M.; Kraft-Todd, G.; Schapira, L.; Kossowsky, J.; Riess, H. The Influence of the Patient-Clinician Relationship on Healthcare Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, N.B.; Prathivadi, P.; Lorenz, K.A.; Zupanc, S.N.; Singer, S.J.; Krebs, E.E.; Yano, E.M.; Wong, H.N.; Giannitrapani, K.F. Teaming in Interdisciplinary Chronic Pain Management Interventions in Primary Care: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.S.; Weaver, K.; Kim, B.; Miller, C.; Lew, R.; Stolzmann, K.; Sullivan, J.L.; Riendeau, R.; Connolly, S.; Pitcock, J.; et al. The Collaborative Chronic Care Model for Mental Health Conditions: From Evidence Synthesis to Policy Impact to Scale-up and Spread. Med. Care 2019, 57, S221–S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, N.; Zamora, K.; Gibson, C.; Tighe, J.; Chang, J.; Grasso, J.; Seal, K.H. Patient Experiences with Integrated Pain Care: A Qualitative Evaluation of One VA’s Biopsychosocial Approach to Chronic Pain Treatment and Opioid Safety. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2019, 8, 2164956119838845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ee, C.; Lake, J.; Firth, J.; Hargraves, F.; de Manincor, M.; Meade, T.; Marx, W.; Sarris, J. An integrative collaborative care model for people with mental illness and physical comorbidities. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Carey, R.N.; Johnston, M.; Rothman, A.J.; de Bruin, M.; Kelly, M.P.; Connell, L.E. From Theory-Inspired to Theory-Based Interventions: A Protocol for Developing and Testing a Methodology for Linking Behaviour Change Techniques to Theoretical Mechanisms of Action. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. IS 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijg, J.M.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Dusseldorp, E.; Verheijden, M.W.; van der Zouwe, N.; Middelkoop, B.J.; Crone, M.R. Measuring determinants of implementation behavior: Psychometric properties of a questionnaire based on the theoretical domains framework. Implement. Sci. IS 2014, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.K.; Krystia, O.; Waugh, E.J.; MacKay, C.; Stanaitis, I.; Stretton, J.; Weisman, A.; Ivers, N.M.; Parsons, J.A.; Lipscombe, L.; et al. Understanding the behavioural determinants of seeking and engaging in care for knee osteoarthritis in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 2022, 4, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yu, Z.; Gu, Y. Theoretical Domains Framework: A Bibliometric and Visualization Analysis from 2005–2023. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 4055–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, J.H.; Bryson, K.; Barsauskaite, L.; Bullo, S. A COM-B and Theoretical Domains Framework Mapping of the Barriers and Facilitators to Effective Communication and Help-Seeking Among People with, or Seeking a Diagnosis of, Endometriosis. J. Health Commun. 2024, 29, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, B.; Kirke, C.; Pate, M.; McHugh, S.; Bennett, K.; Cahir, C. Mapping the Theoretical Domain Framework to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Do multiple frameworks add value? Implement. Sci. Commun. 2023, 4, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.; Barrera, I.; Maytorena-Gutiérrez, R.; Higuera-Díaz, R. #35647 Alternative pharmacological approaches to chronic pain management. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2023, 48, A211.3–A212. [Google Scholar]

- Munneke, W.; Demoulin, C.; Nijs, J.; Morin, C.; Kool, E.; Berquin, A.; Meeus, M.; De Kooning, M. Development of an interdisciplinary training program about chronic pain management with a cognitive behavioural approach for healthcare professionals: Part of a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omaki, E.; Fitzgerald, M.; Iyer, D.; Shields, W.; Castillo, R. Shared Decision-Making and Collaborative Care Models for Pain Management: A Scoping Review of Existing Evidence. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2024, 38, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.W.; Yi, T.H.; Khaing, N.E.E. Chronic pain healthcare workers’ challenges in pain management and receptiveness towards VR as an adjunct management tool: A qualitative study. BMC Digit. Health 2024, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, B.; Maldonado-Rengel, R.; Morillo-Puente, S.; Burneo-Sánchez, E. Attitudes toward and perceptions of barriers to research among medical students in the context of an educational and motivational strategy. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Mavondo, F.; Horvat, L.; McKinlay, L.; Fisher, J. Healthcare professionals’ perspective on delivering personalised and holistic care: Using the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S.; Kellett, S.; Simmonds-Buckley, M.; Stockton, D.; Bradbury, A.; Delgadillo, J. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) in the United Kingdom: A systematic review and meta--analysis of 10--years of practice--based evidence. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 60, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Aaron, R.; Attal, N.; Colloca, L. An update on non-pharmacological interventions for pain relief. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankelow, J.; Ryan, C.; Taylor, P.; Atkinson, G.; Martin, D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Biopsychosocial Pain Education upon Health Care Professional Pain Attitudes, Knowledge, Behavior and Patient Outcomes. J. Pain 2022, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, I.; Pavić, J.; Filipović, B.; Ozimec Vulinec, Š.; Ilić, B.; Petek, D. Integrated Approach to Chronic Pain—The Role of Psychosocial Factors and Multidisciplinary Treatment: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themelis, K.; Tang, N.K.Y. The Management of Chronic Pain: Re-Centring Person-Centred Care. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccleston, C. Chronic pain as embodied defence: Implications for current and future psychological treatments. Pain 2018, 159 (Suppl. S1), S17–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, M.A.; Edwards, R.R.; Becker, W.C.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Kerns, R.D. Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Chronic Pain in Adults. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2021, 22, 52–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Cheville, A. Management of Chronic Pain in the Aftermath of the Opioid Backlash. JAMA 2017, 317, 2365–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, E.; Heathcote, L.; Palermo, T.M.; de C Williams, A.C.; Lau, J.; Eccleston, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological therapies for children with chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Song, G.; Ghannam, R. Enhancing Teamwork and Collaboration: A Systematic Review of Algorithm-Supported Pedagogical Methods. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuier, E.A.; Kolko, D.J.; Aarons, G.A.; Schachter, A.; Klem, M.L.; Diabes, M.A.; Weingart, L.R.; Salas, E.; Wolk, C.B. Teamwork and implementation of innovations in healthcare and human service settings: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. IS 2024, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, N.A.; Al-Habeeb, A.A.; Koenig, H.G. Mental health system in Saudi Arabia: An overview. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2013, 9, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlas, S.; Chami, Z.; Amir, A.; Khader, S.; Bakir, M.; Arifeen, S. A Semi-systematic Review of Patient Journey for Chronic Pain in Saudi Arabia to Improve Patient Care. Saudi J. Med. 2021, 6, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, V.; Esterlis, M.M.; Lorello, R.G.; Sud, A.; Englesakis, F.M.; Bhatia, A. A Scoping Review of Gaps Identified by Primary Care Providers in Caring for Patients with Chronic Noncancer Pain. Can. J. Pain 2023, 7, 2145940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, S.M.; Edwards, R.R. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 87, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadabayev, A.R.; Coy, B.; Bailey, T.; Grzesiak, A.J.; Franchina, L.; Hausman, M.S.; Krein, S. Addressing the Needs of Patients with Chronic Pain. Fed. Pract. 2018, 35, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boring, B.L.; Walsh, K.T.; Ng, B.W.; Schlegel, R.J.; Mathur, V.A. Experiencing Pain Invalidation is Associated with Under-Reporting of Pain: A Social Psychological Perspective on Acute Pain Communication. J. Pain 2024, 25, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazqar, D. Evaluating Saudi Nursing Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward Cancer Pain Management: Implications for Nursing Education. J. King Abdulaziz Univ.-Sci. 2019, 26, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarkandi, O.A. The factors affecting nurses’ assessments toward pain management in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2021, 15, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielke, S.; Corson, K.; Dobscha, S.K. Collaborative care for pain results in both symptom improvement and sustained reduction of pain and depression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C.J.; Watson MacDonell, K.; Moran, M. Provider self-efficacy in delivering evidence-based psychosocial interventions: A scoping review. Implement. Res. Pract. 2021, 2, 2633489520988258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Mata, Á.N.; de Azevedo, K.P.M.; Braga, L.P.; de Medeiros, G.; de Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Bezerra, I.N.M.; Pimenta, I.; Nicolás, I.M.; Piuvezam, G. Training in communication skills for self-efficacy of health professionals: A systematic review. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalav, S.; Bektas, H.; Ünal, A. Effects of Chronic Care Model-based interventions on self-management, quality of life and patient satisfaction in patients with ischemic stroke: A single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 19, e12441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueroni, L.P.B.; Pompeo, D.A.; Eid, L.P.; Ferreira Júnior, M.A.; Sequeira, C.; Lourenção, L.G. Interventions for Strengthening General Self-Efficacy Beliefs in College Students: An Integrative Review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2023, 77, e20230192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reaume, J. Chronic Pain: A Case Application of a Novel Framework to Guide Interprofessional Assessment and Intervention in Primary Care. Can. J. Pain 2023, 7, 2228851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Definition | Constructs | Application in This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Awareness of the existence of something. |

| Healthcare providers’ understanding of CNMP, its psychological aspects, and the role of mental health professionals in its management. |

| Skills | Ability or proficiency acquired through practice. |

| Providers’ proficiency in collaborating with mental health professionals and implementing integrated care strategies for CNMP patients. |

| Social/Professional Role and Identity | A coherent set of behaviors and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting. |

| Providers’ perception of their role in CNMP management and their identity as collaborators with mental health professionals. |

| Beliefs about Capabilities | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about an ability, talent, or facility that a person can put to constructive use. |

| Providers’ confidence in their ability to effectively collaborate with mental health professionals in CNMP management. |

| Beliefs about Consequences | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity of outcomes of a behavior in a given situation. |

| Providers’ beliefs regarding the outcomes of collaborating with mental health professionals, such as improved patient outcomes or workflow efficiency. |

| Reinforcement | Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus. |

| External factors that encourage or discourage providers from engaging in collaborative practices, such as institutional rewards or penalties. |

| Intentions | A conscious decision to perform a behavior or a resolve to act in a certain way. |

| Providers’ commitment and readiness to engage in collaborative care with mental health professionals. |

| Goals | Mental representations of outcomes or end states that an individual wants to achieve. |

| Specific objectives providers aim to achieve through collaboration, such as enhanced patient care or professional development. |

| Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes | The ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment, and choose between two or more alternatives. |

| Cognitive factors affecting providers’ ability to engage in and sustain collaborative practices. |

| Environmental Context and Resources | Any circumstance of a person’s situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence, and adaptive behavior. |

| Organizational and systemic factors that influence collaboration include the availability of mental health professionals, institutional policies, and the allocation of resources. |

| Social Influences | Those interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. |

| Influence of colleagues, supervisors, and the broader medical community on providers’ attitudes and behaviors toward collaboration. |

| Emotion | A complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements, by which the individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event. |

| Emotional responses that may affect providers’ willingness or ability to collaborate, such as stress, anxiety, or job satisfaction. |

| Behavioral Regulation | Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions. |

| Strategies providers use to initiate and maintain collaborative behaviors, including self-monitoring and planning. |

| Optimism | The confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained. |

| Providers’ outlook on the potential success and benefits of integrating mental health services into CNMP management. |

| Variable | * Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female Male | 60 (52.6%) 54 (47.4%) |

| Years of Experience | <1 year 1–3 years 3–5 years 5–10 years 10–15 years 15–20 years >20 years | 29 (25.4%) 25 (21.9%) 14 (12.3%) 16 (14.0%) 19 (16.7%) 4 (3.5%) 7 (6.1%) |

| Hospital Type | General Specialty Primary Care | 98 (86.0%) 13 (11.4%) 3 (2.6%) |

| Region | Western Northern Border Riyadh | 77 (67.5%) 35 (30.7%) 2 (1.8%) |

| Education | Baccalaureate Master’s Doctorate | 100 (87.7%) 6 (5.3%) 8 (7.0%) |

| Profession | Medicine Nursing Pharmacy Physical Therapy Others | 53 (46.5%) 34 (29.8%) 11 (9.6%) 9 (7.9%) 7 (6.1% |

| Perception | Reinforcement | Motivation and Goals | Belief About Capabilities | Belief About Consequences | Skills | Knowledge | Intentions | Social Influence | Environmental Context/Resources | Emotions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception | Person correlation | 1 | 0.264 ** | 0.071 | 0.309 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.099 | 0.046 | −0.123 | 0.154 | 0.293 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.005 | 0.458 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.299 | 0.626 | 0.194 | 0.103 | 0.002 | ||

| Reinforcement | Person correlation | 0.264 ** | 1 | 0.509 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.289 ** | 0.374 ** | −0.163 | 0.292 ** | 0.713 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.002 | 0.000 | ||

| Motivation and goals | Person correlation | 0.071 | 0.509 ** | 1 | 0.148 | 0.197 * | 0.246 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.054 | 0.172 | 0.533 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.458 | 0.000 | 0.118 | 0.037 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.570 | 0.068 | 0.000 | ||

| Belief about capabilities | Person correlation | 0.309 ** | 0.223 * | 0.148 | 1 | 0.083 | 0.210 | 0.426 ** | 0.185 * | 0.142 | 0.267 ** | 0.232 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.118 | 0.380 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.134 | 0.004 | 0.013 | ||

| Belief about consequences | Person correlation | 0.396 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.197 * | 0.083 | 1 | 0.189 * | 0.291 ** | 0.217 * | −0.059 | 0.055 | 0.362 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.380 | 0.045 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.538 | 0.564 | 0.000 | ||

| Skills | Person correlation | 0.298 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.246 ** | 0.210 * | 0.189 * | 1 | 0.180 | 0.382 ** | −0.053 | 0.617 ** | 0.592 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.025 | 0.045 | 0.057 | 0.000 | 0.579 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Knowledge | Person correlation | 0.099 | 0.289 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.426 | 0.291 ** | 0.180 | 1 | 0.251 ** | 0.251 ** | 0.114 | 0.331 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.299 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.057 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.229 | 0.000 | ||

| Intentions | Person correlation | 0.046 | 0.374 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.185 * | 0.217 * | 0.382 ** | 0.251 ** | 1 | 0.151 | 0.327 ** | 0.98 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.626 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.109 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Social Influence | Person correlation | −0.123 | −0.163 | 0.054 | 0.142 | −0.059 | −0.053 | 0.251 ** | 0.151 | 1 | 0.175 | −0.143 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.194 | 0.085 | 0.570 | 0.134 | 0.538 | 0.579 | 0.007 | 0.109 | 0.064 | 0.131 | ||

| Environmental Context/Resources | Person correlation | 0.154 | 0.292 ** | 0.172 | 0.267 ** | 0.055 | 0.617 ** | 0.114 | 0.317 ** | 0.175 | 1 | 0.317 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.103 | 0.002 | 0.068 | 0.004 | 0.564 | 0.000 | 0.229 | 0.000 | 0.0674 | 0.001 | ||

| Emotions | Person correlation | −0.293 ** | 0.713 ** | 0.533 ** | 0.232 * | 0.362 ** | 0.592 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.498 ** | −0.143 | 0.317 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.001 | ||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 14.270 | 10 | 1.427 | 4.771 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 30.508 | 102 | 0.299 | |||

| Total | 44.779 | 112 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients B | St. Error | Unstandardized Coefficients Beta | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.106 | 0.448 | 4.706 | 0.000 | |

| Reinforcement | −0.019 | 0.088 | −0.027 | −0.213 | 0.832 |

| Motivation and goals | 0.017 | 0.076 | 0.027 | 0.227 | 0.821 |

| Belief about capabilities | 0.208 | 0.059 | 0.329 | 3.499 | 0.001 |

| Belief about consequences | 0.237 | 0.057 | 0.382 | 4.129 | 0.000 |

| skills | 0.220 | 0.128 | 0.216 | 1.726 | 0.087 |

| Knowledge | −0.090 | 0.056 | −0.165 | −1.599 | 0.113 |

| Intentions | −0.109 | 0.070 | −0.176 | −1.564 | 0.121 |

| Social influence | −0.044 | 0.075 | −0.054 | −0.582 | 0.562 |

| Environmental context/resources | −0.024 | 0.090 | −0.030 | −0.270 | 0.788 |

| Emotions | 0.089 | 0.126 | 0.100 | 0.706 | 0.482 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alenezi, A.A.; Makhdoom, A.K.; Alanazi, R.A.; Alanazi, F.S.Z.; Alenezi, Y.M.; Alanazi, Z.A.; Bayomy, N.A.; Fawzy, M.S. Healthcare Providers’ Perspectives on the Involvement of Mental Health Providers in Chronic Pain Management. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202604

Alenezi AA, Makhdoom AK, Alanazi RA, Alanazi FSZ, Alenezi YM, Alanazi ZA, Bayomy NA, Fawzy MS. Healthcare Providers’ Perspectives on the Involvement of Mental Health Providers in Chronic Pain Management. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202604

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlenezi, Aziza Ali, Amin K. Makhdoom, Rehab Abdullah Alanazi, Fahad Saad Z. Alanazi, Yusef Muhana Alenezi, Zaid Alkhalfi Alanazi, Naglaa A. Bayomy, and Manal S. Fawzy. 2025. "Healthcare Providers’ Perspectives on the Involvement of Mental Health Providers in Chronic Pain Management" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202604

APA StyleAlenezi, A. A., Makhdoom, A. K., Alanazi, R. A., Alanazi, F. S. Z., Alenezi, Y. M., Alanazi, Z. A., Bayomy, N. A., & Fawzy, M. S. (2025). Healthcare Providers’ Perspectives on the Involvement of Mental Health Providers in Chronic Pain Management. Healthcare, 13(20), 2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202604