Abstract

Introduction. Singapore had previously embraced at least two types of pre-participation questionnaires for those intending to take up or enhance their level of physical activity (PA). Concern over the usefulness of and difficulty in understanding these questions led to the design of a Singapore Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (SPARQ). The primary objective of this study was to review the level of difficulty in understanding the seven SPARQ questions. Secondary objectives included the rate of identifying individuals as unfit for PA and to seek public feedback on this tool. Method. A public, cross-sectional survey on the SPARQ was carried out, obtaining participants’ bio-characteristics, having them completing the SPARQ and then providing feedback on the individual questions. Results. Of the 1136 who completed the survey, 35.7% would have required referral to a medical practitioner for further evaluation before the intended PA. Significant difficulty was experienced with one question, moderate difficulty with four and only slight difficulty with the remaining two. The length of the questions and use of technical terms were matters of concern. Suggestions were provided by the participants on possible amendments to the questions. Conclusions. The very high acceptance rate of the SPARQ will need to be tempered with modifications to the questions to enhance ease of understanding and use by members of the public.

1. Introduction

Sports injuries can occur during competitive or recreational physical activity (PA), usually through falls or cardiovascular collapse. Regular PA also has many benefits, such as lower rates of obesity, heart disease and a better quality of life. Adults are usually encouraged to be physically active on most days of the week to better achieve the expected health benefits of regular exercise [1]. The United Kingdom Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity guidelines and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommend 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and 2 or more days per week of strengthening activity for adults and the elderly and 60 min of moderate/vigorous activity a day for children [2,3]. For Asian populations, modifications of such PA requirements have been proposed [4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity PA weekly [5].

To promote early identification of persons prone to injuries, pre-participation screening systems have been suggested for use by those wishing to participate in moderate or intense exercise or increase their level of PA [6,7]. These are intended to identify individuals with a likely risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD) or other major injury. Such at-risk individuals should require medical evaluation before being cleared for a PA program. One such system, when applied to adults over 40 years old, resulted in nearly 95 percent of those in that age group being referred to a physician before engaging in any form of exercise [8,9]. Refinement of preparticipation screening procedures in 2015 resulted in an approximately 41% decrease in the proportion of such referrals [10].

In Singapore, over the years, different pre-participation questionnaires have been suggested by the Sports Safety Committee, beginning in 2007 with the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) followed by the Get Active Questionnaire (GAQ) in 2019 [6,7,11,12,13]. However, concern has been expressed about the complexity and difficulty in self-administering these tools and that they did not address the occurrence of heat-related injuries for those exercising in hot and humid environments [14,15,16].

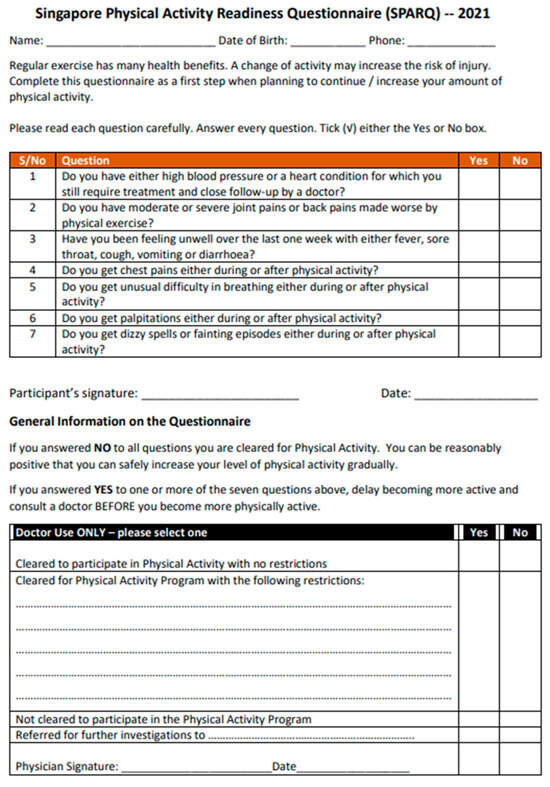

To address these concerns, the authors drafted a fresh pre-participation questionnaire for members of the public. Provisionally named as the Singapore Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire 2021 (SPARQ—Figure 1), this document had seven questions, each needing either a Yes or No answer. A Yes answer to any of the seven questions would suggest the participant is unfit for PA and require further medical evaluation. The readability test scores for this questionnaire were Flesch–Kincade Readability Grade Level = 9 and Flesch Readability Ease score 45.2.

Figure 1.

Singapore Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire—2021.

The first question was “Do you have either high blood pressure or a heart condition for which you still require treatment and close follow-up by a doctor?”. This was intended to address those whose high blood pressure or heart conditions were not well controlled, potentially increasing the risk of cardiac arrest if they were to increase their exercise intensity.

The second question, “Do you have moderate or severe joint pains made worse by physical exercise?”, was to identify those with disabling symptoms that were likely aggravated by increasing PA or made one prone to injury.

The third question, “Have you been feeling unwell over the last one week with either fever, sore throat, cough, vomiting or diarrhoea?”, was to address those acutely unwell and more prone to heat-related injuries.

The fourth question, “Do you get chest pains either during or after physical activity?”, was to identify those with anginal symptoms requiring further evaluation and stabilization before being advised on PA. This was to facilitate early identification of sudden cardiac arrest-prone individuals.

The fifth question, “Do you get unusual difficulty in breathing either during or after physical activity?”, was to identify those with either critical lung or coronary artery disease with likelihood of collapse during PA.

The sixth question, “Do you get palpitations either during or after physical activity?”, was for those who felt their heart beating faster than with similar previous PA. Palpitations had previously been identified as one of the symptoms felt by some who collapsed during PA [15].

The seventh question, “Do you get dizzy spells or fainting episodes either during or after physical activity?”, was owing to similar previous reports [17].

The primary objective of this study was to determine the level of difficulty in understanding of the SPARQ questions by members of the public. Secondary objectives were to determine the rate of persons declared unfit, if using the tool, and hence identify adults requiring further medical evaluation prior to participating in moderate or intensive PA, and obtain feedback on these questions.

2. Methods

This was a cross-sectional study on the use of the SPARQ. It was conducted as an anonymized public survey over a three-month period via an online platform, SoGo Survey, marketed by qualtricsTM, Seattle, WA, USA. Participation was voluntary and open to any member of the public 21 years of age and above. Randomness in volunteer participation could not be avoided in this survey. However, to minimize volunteer bias we reached out through various channels like governmental agencies, community grassroot and national sports agencies, professional societies and institutes of higher learning to help broaden the participation pool. In addition, to better ensure anonymity and confidentiality we reassured potential participants that their identities and data would be kept confidential.

Prior to survey participation, respondents were provided with basic information regarding the need for a self-administered pre-participation screening tool to identify persons at greater risk of adverse events during PA. Once formal consent was obtained, participants completed the three sections of the survey.

One section collected demographic information (age, sex, height, weight, ethnic group, smoking history and frequency of PA). The second was the SPARQ itself. The third was a survey on the difficulty of understanding each of the seven questions, the use of technical terms and the length of the questionnaire. Feedback was on a 5-point Likert scale. Participants were also asked for comments and suggestions on information included in the questionnaire, and their preferred frequency for completing the SPARQ. All survey responses were anonymized. Only study team members were given authorization to access the data.

Three participant sub-groups were created based on age. This study was powered to show a 10% difference in mean values between these sub-groups with a standard deviation of 25% using α = 0.50 and p = 0.05. This required a minimum number of 293 participants for each age-group in this study. Additionally, an incomplete survey response of at least 10% was expected. Hence, the minimum number was multiplied by 3 (for a total of 879) and raised to 1000.

This study was approved by the Institution Review Board of the Singapore Sports Institute (Approval Number SSG-EXP-002).

3. Data Analysis

The collected data were anonymized and automatically compiled into a Microsoft Excel database. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM Corp. (Released 2012). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

To conduct comparative analyses, respondents were categorized into three age groups (21–39.9 years, 40–59.9 years and ≥60 years). Respondents’ BMI and weekly PA were also grouped into five BMI categories (according to the WHO-proposed Asian BMI scale) and four PA groups (<150 min, 150–299 min, 300–449 min and ≥450 min per week) [18].

Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize nominal and ordinal data. Non-parametric comparisons of independent samples were conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis test, Mann–Whitney U test, and Chi-square tests, as appropriate. Parametric data comparisons were performed using t-tests and ANOVA. Reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha) was performed for the performance of the Likert scale in assessing ease of understanding of the questions.

Feedback on SPARQ Data

In reviewing the responses from study participants, the authors considered satisficing in potentially influencing feedback results. Five types of satisficing behaviors were looked for amongst the survey respondents, viz. primary bias, acquiescence bias, early termination, non-response and straight-lining. Satisficing analysis was performed using methods suggested by Barge, Vriesema and Gehlbach [19,20]. The apparently satisficed data were removed from the feedback analysis and, owing to lack of universally-agreed definitions of difficulty in understanding when attempting such questions, the means of the Likert scores were arbitrarily divided into four groups of levels of difficulty as shown below:

| Difficulty Likert Index * | Level of Difficulty |

| ≥4.51 | No Difficulty |

| 4.01–4.50 | Slight Difficulty |

| 3.51–4.00 | Moderate Difficulty |

| ≤3.50 | Significant Difficulty |

| * Assuming a 90% Likert 5 rate for no difficulty, 70% for slight difficulty, 50% for moderate difficulty and 30% for significant difficulty and the other responses equally distributed amongst the lower Likert numbers, the mean Likert scores derived were 4.75 (no difficulty), 4.25 (slight difficulty), 3.75 (moderate difficulty) and 3.25 (slight difficulty). Using these mean values, a scale of ≥4.51 to 5.00 to signify no difficulty, 4.01 to 4.50 to signify slight difficulty, 3.51 to 4.00 to signify moderate difficulty and ≤3.50 to signify significant difficulty was created. | |

Likert scale reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha) was determined for this survey. Free-text comments were also collected and grouped for possible feedback on future refinements of the questions.

4. Results

A total of 1137 persons participated in this study. One was under 21 years of age. No participants needed to be excluded from analysis for extensively incomplete data. Analysis was based on the remaining 1136 respondents.

4.1. Participant Characteristics (Table 1)

Males formed 56.5% of respondents and were older than females. The ethnic breakdown of the participants was generally similar to the population of Singapore, though there was slight under-representation of the elderly (19% vs. national 26.4%) and non-Chinese groups (Malays 5.9% vs. 12.8% and Indians 7.0% vs. 8.7%). The BMI was lower in the 21–39.9 and >60 years age-groups compared to those between 40–59.9 years age (24.2 and 23.6 vs. 24.7, p = 0.001). About 23.8% had at least one illness. Of these 18.5% had only one co-morbidity. Overall, 9.0% had hypertension, 4.8% dyslipidemia, 2.2% heart disease, 0.4% cancer, 3.3% diabetes mellitus and 9.7% had other illnesses. Persons with known medical illnesses were, generally older than those without.

Only 52.6% of respondents reported exercising for at least 150 min per week. Those >60 years of age spent more time on PA (318 min) versus 208 min for those between 40–59.9 years and 174 min for those <40 years age (p = 0.0001). There was no difference in the duration of PA per week for those with one or more forms of medical illness versus those without (p = 0.120). There was no decrease in PA duration with increasing numbers of co-morbidities (p = 0.862). Amongst persons with medical conditions, only those with cancer (median 150 vs. 60 min, p = 0.044) and those with other illnesses (median 160 vs. 120 min, p = 0.019) exercised less than those without such comorbidities.

Overall, 0.9% of participants stated that their medical conditions were not under control and 2.4% that the illness affected their ability to do PA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| Participant Characteristic | Data | Singapore Population Data |

|---|---|---|

| (Where Available) | ||

| Gender (%) | ||

| Male | 642 (56.5%) | 54.30% |

| Female | 494 (43.5%) | 45.70% |

| Age (mean ± sd 1) | 48.7 ± 11.6 years | 47.8 years |

| Males | 49.5 ± 11.8 years | |

| Females | 47.6 ± 11.3 years | |

| Age Distribution | ||

| 21–39.9 years | 25.20% | 35.60% |

| 40–59.9 years | 55.80% | 38.00% |

| 60–80.0 years | 19.00% | 26.40% |

| Cigarette Smoker (%) | ||

| Yes | 59 (5.2%) | NA |

| No | 1077 (94.8%) | |

| Basal Metabolic Index | ||

| Very Low (<18.5) | 48 (4.2%) | NA |

| Low (18.5–22.9) | 400 (35.2%) | |

| Moderate (23.0–27.4) | 481 (42.3%) | |

| High (27.5–32.9) | 156 (13.7%) | |

| Very High (>33.0) | 51 (4.5%) | |

| Ethnic Groups | ||

| Chinese | 932 (82.0%) | 75.30% |

| Malay | 67 (5.9%) | 12.80% |

| Indian | 80 (7.0%) | 8.70% |

| Others | 57 (5.0%) | 3.20% |

| Duration of Physical Activity per week (minutes) | NA | |

| 0–149 min | 539 (47.4%) | NA |

| 150–299 min | 288 (25.3%) | |

| 300–449 min | 168 (14.8%) | |

| ≥450 min | 142 (12.5%) | |

| Physical Activity per week (minutes) by age group | ||

| Age Group 21–39.9 years | 174 ± 167 | p < 0.0001 |

| Age Group 40–59.9 years | 208 ± 208 | |

| Age Group > 60 years | 314 ± 268 | |

| Physical Activity per week (minutes) by presence of co-morbidity | ||

| No co-morbidities | 219 ± 205 | p = 0.120 |

| With co-morbidities | 220 ± 253 | |

| Age Group of Respondents with co-morbidities | ||

| No co-morbidities = 866 (76.2%) | 47.5 ± 11.3 years | p = 0.0001 |

| With co-morbidities = 270 (23.8%) | 52.5 ± 11.8 years | |

| Proportion of co-morbidities by age group: | ||

| Age Group 21–39.9 years | 45/286 (15.7%) | NA |

| Age Group 40–59.9 years | 149/633 (23.5%) | |

| Age Group ≥ 60 years | 76/216(35.2%) | |

| By number of co-morbidities | ||

| 1 co-morbidity | 221/1136 (19.5%) | NA |

| 2 co-morbidities | 38/1136 (3.3%) | |

| 3 or more co-morbidities | 11/1136 (1.0%) |

1 sd = standard deviation.

4.2. Participants’ Responses to the Seven SPARQ Questions (Table 2)

The Likert scale reliability analysis performed for this survey showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.738.

- Question 1 (Do you have either high blood pressure or a heart condition for which you still require treatment and close follow-up by a doctor?)

For this first question, 13.2% reported either high blood pressure or heart disease still requiring treatment or close follow-up by a doctor. These were slightly older than those without heart disease or hypertension. There was no difference in their weekly duration of PA. Moderate difficulty in understanding the question was encountered by those answering Yes. Respondents fed-back that the question covered two medical conditions, viz. high blood pressure and heart disease, and was, therefore, double-barreled.

- Question 2 (Do you have moderate or severe joint pains or back pains made worse by physical exercise?)

For this question, 16.9% reported Yes. There was no significant age difference between those with or without such pains. Those with pain exercised less and encountered moderate difficulty with this question. For the 47 (4.1%) who expressed difficulty with this question, the terms moderate and slight were subjective and unsure whether back pain and backache were the same condition.

- Question 3 (Have you been feeling unwell over the last one week with either fever, sore throat, cough, vomiting or diarrhea?)

For this question, 3.1% said Yes. There was no significant difference in age or usual duration of exercise with those who felt well. Those with symptoms expressed slight difficulty in understanding this question, while the others expressed no difficulty. Some felt that fever, cough, sore throat, vomiting and diarrhea should have been enquired about separately since persons may not likely have all these conditions at the same time.

- Question 4 (Do you get chest pains either during or after physical activity?)

For this question, 2.5% answered Yes. There was no significant difference in age or numbers of cardiac risk factors from those not experiencing chest pain during PA. Those with symptoms generally exercised less and had moderate difficulty in understanding the question. The others did not encounter such difficulty. Those claiming difficulty were trying to grapple between what constituted chest pain and chest ache and wanted examples for better understanding.

- Question 5 (Do you get unusual difficulty in breathing either during or after physical activity?)

Only 4.1% of participants experienced breathing difficulty that was unusual for that level of exercise. While there was no significant age difference amongst the groups, those with breathing difficulty exercised significantly less and experienced moderate difficulty in understanding the question. They felt that the word “unusual” was subjective and sometimes ambiguous. People who were exercising would always feel more breathless and wanted another word or phrase to better describe the abnormal symptoms.

- Question 6 (Do you get palpitations either during or after physical activity?)

Up to 5.6% answered Yes. There was no significant age difference between those with or without palpitations. The symptomatic participants exercised less. Significant difficulty amongst symptomatic participants in understanding this question and moderate difficulty by others was because the word “palpitations” was considered too technical, and “medical jargon”, requiring simplification for better understanding.

Table 2.

Participants’ responses to the SPARQ.

Table 2.

Participants’ responses to the SPARQ.

| S/No | Answering Yes/No to SPARQ 1 Question | Frequency, n (%) | Age in Years (Mean ± SD 2); p Value | Minutes per Week of PA 3 (Mean ± SD 2); p Value | Level of Understanding Index (Mean ± SD 2) for Non-Satisficing Participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty Index | p Value | Level of Difficulty 4 | |||||||

| 1. | SPARQ 1 Question 1 | ||||||||

| 150 (13.2%) | 55.5 ± 10.8 | p = 0.000 | 219.7 ± 226.1 | p = 0.668 | 3.95 ± 1.11 | p = 0.001 | Moderate Slight | |

| 985 (86.8%) | 47.7 ± 11.4 | 219.2 ± 215.4 | 4.46 ± 0.87 | |||||

| 2. | SPARQ 1 Question 2 | ||||||||

| 192 (16.9%) | 49.3 ± 11.2 | p = 0.442 | 193.7 ± 209.4 | p = 0.007 | 3.72 ± 0.94 | p = 0.0004 | Moderate Slight | |

| 944 (83.1%) | 48.6 ± 11.7 | 224.5 ± 218.0 | 4.17 ± 0.91 | |||||

| 3. | SPARQ 1 Question 3 | ||||||||

| 35 (3.1%) | 47.6 ± 10.2 | p = 0.582 | 188.9 ± 168.0 | p = 0.491 | 4.19 ± 1.06 | p = 0.003 | Slight Nil | |

| 1102 (96.9%) | 48.7 ± 11.7 | 220.2 ± 218.1 | 4.70 ± 0.91 | |||||

| 4. | SPARQ 1 Question 4 | ||||||||

| 28 (2.5%) | 45.5 ± 12.7 | p = 0.143 | 158.4 ± 236.5 | p = 0.011 | 3.69 ± 1.08 | p = 0.0003 | Moderate Nil | |

| 1109 (97.5%) | 48.8 ± 11.6 | 220.8 ± 216.2 | 4.57 ± 0.78 | |||||

| 5. | SPARQ 1 Question 5 | ||||||||

| 47 (4.1%) | 45.9 ± 11.8 | p = 0.088 | 148.8 ± 193.9 | p = 0.0002 | 3.65 ± 1.23 | p = 0.018 | Moderate Slight | |

| 1089 (95.9%) | 48.8 ± 11.6 | 222.1 ± 217.3 | 4.17 ± 1.08 | |||||

| 6 | SPARQ 1 Question 6 | ||||||||

| 64 (5.6%) | 46.2 ± 12.3 | p = 0.072 | 142.7 ± 174.1 | p = 0.0001 | 3.08 ± 1.36 | p = 0.033 | Significant Moderate | |

| 1073 (94.4%) | 48.9 ± 11.6 | 223.8 ± 218.3 | 3.54 ± 1.20 | |||||

| 7. | SPARQ 1 Question 7 | ||||||||

| 69 (6.1%) | 43.1 ± 10.1 | p = 0.0004 | 141.7 ± 168.2 | p = 0.0001 | 4.26 ± 1.06 | p = 0.341 | Slight Nil | |

| 1067 (93.9%) | 49.1 ± 11.7 | 224.4 ± 218.8 | 4.50 ± 0.81 | |||||

1 SPARQ = Singapore Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire, 2 SD = Standard Deviation, 3 PA = Physical Activity, 4 Level of difficulty is defined as mean Likert scale index ≥ 4.51 (No Difficulty), 4.01–4.50 (Slight Difficulty), 3.51–4.00 (Moderate Difficulty), ≤3.50 (Significant Difficulty).

- Question 7 (Do you get dizzy spells or fainting episodes either during or after physical activity?)

For this question 6.1% answered “Yes”. Those with symptoms were generally younger, exercised much less and experienced slight difficulty in understanding. Those without symptoms had no difficulty. A few requested that the word “immediately” be added just before the words “after physical activity”. Some wanted the terms dizzy spells and fainting to be separate questions.

4.3. Participants Requiring Further Referral

Even though only 23.7% of the participants had a known prior medical condition, 35.7% of participants answered “Yes” to one or more of the seven questions posed in the SPARQ. For patients without known medical illnesses, 27.0% said Yes to one or more of the questions and would have been initially declared unfit for PA requiring further evaluation by a doctor versus 62.2% for those with a known medical illness (p = 0.000). When distributed by age this would be 32.0% of those from age 21–39.9 years, 36.0% of those from 40–59.9 years, and 38.0% of those aged 60 years and above (p = 0.277).

4.4. Participants Feedback on the SPARQ

Level of Difficulty in Understanding the SPARQ Questions

Generally, 90.0% of survey participants felt the quality of the advice provided in the SPARQ was adequate and 93.1% would be happy to follow it. The length of the questionnaire and the use of technical terms were felt to be adequate by 93.4% of the participants, regardless of presence of symptoms or co-morbidities. While overall satisfaction was high, targeted feedback revealed specific terminology concerns. Comments were received from 26.6% of survey participants. This included 28.8% from those with and 25.3% without symptoms.

A high rate of satisficing was observed (688 or 60.6%). The practice of satisficing was greater amongst those without symptoms (64.8%) versus 52.8% amongst those with symptoms (p = 0.000). The level of difficulty in understanding the questions was greater amongst those with co-morbidities for the first six questions. For Question 7 on dizzy spells and fainting no significant difference in level of understanding between those with or without symptoms was noted.

Many participants commented that the questions were well drafted and simple to understand. The suggestions and comments by the participants on these questions are summarized in Table 3. These comments and suggestions are to be utilized when considering refinements of the questions.

Table 3.

Comments, queries and suggestions by participants on each of the SPARQ questions.

4.5. Suggested Frequency of SPARQ Usage

While only 40.6% of participants preferred the SPARQ to be used by exercise participants once annually, 36.6% preferred it be performed once every six months and the remaining 22.8% as frequently as needed. Those in older age groups preferred a once yearly schedule compared to those in younger age groups (p = 0.038).

5. Discussion

This study’s objectives were to determine the level of difficulty in understanding the questions in the SPARQ, the likelihood of potential exercise participants being declared unfit and requiring further medical evaluation, and to obtain feedback from the public on the document. The participants came from a broad age-spectrum and different walks of life. This is the first pre-participation tool co-designed with public feedback and also meant to address the need for those exercising in heat-prone environments that pose a higher risk of injury. Such feedback should be relevant for adult populations working and living in similar environments. This study was able to determine such difficulty in understanding the SPARQ questions. Thus, even though the level of satisfaction of the questionnaire exceeded 90%, 26.6% of participants provided comments. Most of these comments were not criticisms but provided for consideration of further improvements in the wording of the questionnaire.

Though the proportion of co-morbidities were expectedly higher in the older age groups with more of them requiring medical referral prior to actively engaging in PA, this, generally, did not result in less time spent by them on PA. This could have been because respondents in the younger age groups may have been actively employed with less time to spend on physical activities. This also suggests that the older age groups, though more prone to disease, may be more likely to engage in PA and therefore having a greater need for pre-participation screening. That those with co-morbidities had greater difficulty in understanding the questions also suggests that the construct of the questions needs to be addressed adequately to better ensure that those more prone to illnesses have less issues with using such questionnaires. This can be due to various factors including the complexity of the information, the patient’s cognitive or physical state, and their level of health literacy.

With the draft SPARQ, approximately one-third would have been declared unfit to engage in moderate or intense PA and be referred to a doctor for further evaluation. This was similar to the what would have occurred in a similar population using the Canadian GAQ, but less than would have been seen with the PAR-Q+ [15,17]. The majority of referrals were from questions 1 and 2, which may have been phrased in general terms, without adequate differentiation to the degree of active symptom control. There would be a need to review these two questions to determine whether further refinement of these may help decrease unnecessary referrals. After all, only 0.9% of participants stated that their medical conditions were not under control and only 2.4% that their illness affected the ability to do PA. Such refinement may also be considered for questions 4, 5 and 6. Naturally, there is concern as to whether the large numbers of potential referrals may unduly stress health resources. If one-third of all adults undergoing pre-participation screening need medical referral for further evaluation and testing, the numbers of doctors required to conduct such evaluations and the cost of these can be staggering [3]. For those whose symptoms or illnesses are well controlled, there should not be a need for further medical referral before continuing PA or gradually increasing their level of PA. Further referral may become a major disincentive to engage in PA, especially for the elderly. For reference, the use of the PARQ+ in the USA had seen much higher rates of referral in excess of 55%, even after appropriate modifications made [21]. That there was no significant difference in referral rates across age groups suggests that careful refining of the questions to identify those whose conditions are poorly controlled may better help determine the relationship between age and need for further medical referral. Just going by the duration of PA in the different age groups, it would not be far-fetched to consider whether the younger cohort may more likely also have poorly controlled disease that contributes to their lesser PA duration and therefore requiring medical referral. Therefore, careful wording of the questions may better help identify those requiring such referral.

Active ischemic heart disease, whether known or unknown, increases the risk of cardiovascular collapse during acutely stressful events such as unaccustomed PA, especially if not well controlled [1,14,22]. Therefore, the question on heart disease needs to be retained and refined by language that highlights lack of adequate control. A suggested revised question would be “Do you have heart disease that is not well controlled (i.e., chest pain, chest ache, chest tightness, chest discomfort and shortness of breath, in spite of medication) over the last six months?”

The role of hypertension vis-à-vis PA needs careful evaluation. Though hypertension is a known risk factor for coronary artery disease, adverse events had not been reported if the baseline blood pressure was 140–180 mm Hg systolic and ≤90 mm Hg diastolic [1]. The European Society of Cardiology 2020 guidelines recommend withholding maximal exercise stress testing if the BP exceeds 160/90 mm Hg [22]. Otherwise, if medically stable and with BP < 160/90 mm Hg further medical referral may not be required. The ACSM recommends that asymptomatic individuals with cardiovascular, metabolic or renal disease can continue exercising with progressive intensity unless new symptoms develop and that only patients with known uncontrolled BP (resting BP ≥ 140/90 mm Hg), stage 2 hypertension (BP ≥ 160/100 mm Hg) or target organ disease need undergo medical clearance before PA [3,23,24]. Therefore, only symptomatic, hypertensive patients or those with known uncontrolled high blood pressure may require medical evaluation before engaging in PA [25]. The question on hypertension may, thus, be revised to “Do you have difficulty in controlling your high blood pressure (having headaches with dizziness and blurring of vision) with medicines over the last six months?”

For question 2 on joint pains, a relatively common complaint, regular low-impact PA can maintain physical function and reduce pain levels in patients with osteoarthritis [26]. Understanding the International Olympic Committee’s concerns for musculoskeletal screening and increased risks of reinjury and contralateral side injury with recent ankle sprains, the language of this question needs refinement to minimise misunderstanding and reduce unnecessary referrals [27,28]. A possible revised question may be as follows: “Do you have aches and pains in your bones, joints and muscles that severely limits ability to perform physical exercise?”

Short, acute illnesses can predispose to heat injuries [29]. Heat disorders can occur with strenuous PA, especially when performed shortly after recent mild illnesses such as viral infections and gastroenteritis [30]. Many jurisdictions advise rest and avoidance of PA if recent such illnesses occur. Heat stroke can also result in cardiac complications including sudden cardiac death [31]. The very high understanding of this question suggests its retention. A slightly revised version of this question to ensure consistency in style with the other questions could be “Do you feel unwell over the last one week with either fever, sore throat, cough, vomiting or diarrhea?”

The small number of participants experiencing chest pains had moderate difficulty with this question. Chest pain during exertion suggests acute ischemic heart disease. Chest pain during exertion contributes to a high proportion of prodromal symptoms prior to collapse during PA [32,33,34]. Modifications to this question may allow better understanding. The need to avoid duplication with Question 1 that concerns ischemic heart disease should also be considered.

Unusual difficulty in breathing is a well-recognized prodromal symptom in previous studies on cardiac arrest during PA [21,35,36]. Unusual breathlessness may also portend a worsening respiratory condition [37]. The words, “unusual breathlessness” may require review. Such symptoms are relevant to the questionnaire. A suggested revised version may be “Do you feel more breathless when doing physical exercise than you usually would for that level of activity?”

The question on palpitations needs review. While palpitations may be a prodromal symptom in cardiac arrest patients, it has been equally prevalent in non-cardiac arrest patients in another study [38,39]. With significant misunderstanding issues and conflicting evidence of its value, one would need to review including this question in any pre-participation questionnaire.

There was only slight difficulty for the seventh question on dizzy spells or fainting episodes during or after PA. Dizziness is a prodromal symptom amongst cardiac arrest patients, including among athletes [17,39]. While the causes of dizziness may not be obvious initially it merits careful evaluation. The suggestion on adding the word “immediately” before “after physical activity” appears reasonable. The suggested revised version of this question would be “Have you felt dizzy or fainted either during or shortly after physical exercise over the last six months?”

Adopting and adapting the SPARQ as a primary pre-participation screening tool for PA may be considered with suitable modifications to the questions and after considering participants’ feedback. When applying such questionnaires across communities, large numbers of medical referrals may unduly strain existing medical resources [10]. While refinements may reduce referrals, this requires empirical verification.

6. Limitations of the Study

Even though Singapore has one of the highest digital literacy rates in the world and most homes have internet access, we recognize the challenges in accessing the survey for those without these. Our use of the online survey platform may have excluded a small segment of the population with low digital literacy or without internet access which may have resulted in some selection bias. We acknowledge the potential for randomness in volunteer participation and volunteer bias and its possible influence on this study’s findings. To minimize this, we reached out through various channels like governmental agencies, community grassroot and national sports agencies, professional societies and institutes of higher learning to help broaden the participation pool. In addition, to better ensure anonymity and confidentiality we re-assured potential participants that their identities and data will be kept confidential.

The ethnic composition of the study participants differed slightly from that of the country. This could be addressed in future such studies by use of stratified sampling.

This study could not examine the reliability of the SPARQ in minimizing the likelihood of adverse events during moderate to intense PA. While reliability of any pre-participation tool is important, predictive validity of such a questionnaire would have required a prospective long-term follow-up effort involving large numbers of community participants using this tool and monitoring of adverse outcomes after PA, which was beyond the scope of this study. In addition, none of the existing pre-participation questions that are commonly used have been known to have undergone a predictive reliability-testing process.

The presence of satisficing in this study was also a limitation as would be in similar questionnaires. However, efforts in identifying this helped to better understand the feedback from study participants. A high proportion of data were, unexpectedly, noted to be likely satisficed and removed from feedback analysis. This must be recognized as a likely limitation in surveys of this nature. Prior expectation of high satisficing rates would have resulted in the need to appropriately increase sample size. Measures were also applied to decrease satisficing behavior by trying to make the task of undertaking the survey easier and engaging through simplifying the task, trying to use clear and concise language and avoiding overly technical terms. In addition, a five-point, rather than a 7, 9 or 10-point Likert scale was used to minimize the number of choices and avoid complex question formats. The participant instructions were made fairly detailed so as to give respondents a clear understanding of the tasks and their purpose. The instructions had stated that their in-puts were valuable and can contribute to a larger goal. The survey was also kept relatively short so that it may be completed within ten minutes. In this anonymized public survey, we could not have clinically verified the presence/absence of actual conditions amongst those apparently unfit for PA. However, with actual individual use of the SPARQ, and further evaluation by a medical practitioner, if applicable, such verification and validation may have been performed.

In this study, the intensity of PA could not be defined owing to this being a survey-based study. Lay persons were not expected to be able to define the intensity of their PA in objective terms. Instead, duration of PA has been used, though this may not always equate to exercise intensity.

Finally, this questionnaire survey was not pilot-tested. Future studies on this should consider inclusion of such testing with cognitive interviews during tool development.

7. Conclusions

PA readiness questionnaires, such as the SPARQ, should be implemented community-wide, after due consultation with potential users, viz. members of the public, and also, perhaps, the sports community. Such an approach will more likely ensure that public safety is better served without having to send large sections of the community for medical evaluation and disincentivizing PA. All communities around the world may use the lessons from this study to consider validating their own such pre-participation tools. Of course, following such revision, there will be a need for significant efforts to implement and encourage use of the tool, even with digital and social media technology. These should allow and facilitate follow-up to assess the usefulness of such tools and empirically verify and validate their use for a safer sports environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.; Data curation, A.V. and T.L.T.; Formal analysis, T.L.T., I.Z.H., L.C.H., S.H.C.A. and A.V.; Methodology, T.L.T., I.Z.H., L.C.H., S.H.C.A. and A.V.; Resources, S.H.C.A.; Software, S.H.C.A.; Supervision, A.V.; Validation, S.H.C.A.; Writing—original draft, T.L.T. and A.V.; Writing—review and editing, T.L.T., I.Z.H., L.C.H., S.H.C.A. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institution Review Board of the Singapore Sport Institute (Approval No. SSG-EXP-002, 21 September 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data which form the basis for the Tables in this manuscript are available on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thomas, S.G.; Goodman, J.M.; Burr, J.F. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: Established cardiovascular disease. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36 (Suppl. 1), S190–S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S.C.; Atherton, F.; McBride, M.; Calderwood, C. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines UK 2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Riebe, D.; Franklin, B.A.; Thompson, P.D.; Garber, C.E.; Whitfield, G.P.; Magal, M.; Pescatello, L.S. Updating ACSM’s Recommendations for Exercise Preparticipation Health Screening. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliodromiti, S.; Ghouri, N.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Sattar, N.; Lumsden, M.A.; Gill, J.M.R. Should Physical Activity Recommendations for South Asian Adults Be Ethnicity-Specific? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study of South Asian and White European Men and Women. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- PAR = Q+. The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone. PAR-Q+ Collaboration. Available online: https://eparmedx.com/?page_id=75 (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology. Get Active Questionnaire. Available online: https://csep.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/GETACTIVEQUESTIONNAIRE_ENG.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Whitfield, G.P.; Pettee Gabriel, K.K.; Rahbar, M.H.; Kohl, H.W., III. Application of the American Heart Association/American College of Sports Medicine Adult Preparticipation Screening Checklist to a nationally representative sample of US adults aged >= 40 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 to 2004. Circulation 2014, 129, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maranhão Neto G de, A.; Santos, T.M.; Pedreiro, R.C.D.M.; Carmo, H.A.D.; Jardim, R.T.C.; Lorenzo, A.D. Diagnostic Validity of Screening Questionnaire American College of Sports Medicine/American Heart Association. J. Phys. Educ. 2019, 30, e3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, G.P.; Riebe, D.; Magal, M.; Liguori, G. Applying the ACSM Preparticipation Screening Algorithm to U.S. Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 2056–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sports Safety Committee. Overview and Recommendations for Sports Safety in Singapore—A Report by the Sports Safety Committee. 2007. Available online: https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/46/d0ec8ec6-5bd8-470f-97a5-3e534916ecd9/Sports_Safety_Committee_26SEPO7.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Warburton, D.; Jamnik, V.; Bredin, S.; Shephard, R.; Gledhill, N. The 2022 Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) and electronic Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination (ePARmed-X+): 2022 PAR-Q+. Health Fit. J. Can. 2022, 15, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Get Active Questionnaire—Reference Document. Available online: https://csep.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/GAQREFDOC_ENG.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Venkataraman, A.; Hong, I.Z.; Ho, L.C.; Teo, T.L.; Ang, S.H. Public Perceptions on the Use of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ho, C.L.; Anantharaman, V. Relevance of the Get Active Questionnaire for Pre-Participation Exercise Screening in the General Population in a Tropical Environment. Healthcare 2024, 12, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ho, L.C.; Hong, I.Z.; Teo, T.L.; Ang, S.H.C.; Venkataraman, A. Public Perceptions of the Get Active Questionnaire. Int. J. Orthop. Sports Med. 2015, 6, 1015. [Google Scholar]

- Marijon, E.; Uy-Evanado, A.; Dumas, F.; Karam, N.; Reinier, K.; Teodorescu, C.; Narayanan, K.; Gunson, K.; Jui, J.; Jouven, X.; et al. Warning Symptoms Are Associated with Survival from Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 164, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163, Erratum in: Lancet 2004, 363, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, B.; Gehlbach, H. Using the Theory of Satisficing to Evaluate the Quality of Survey Data. Res. High. Educ. 2012, 53, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriesema, C.C.; Gehlbach, H. Assessing survey satisficing: The impact of unmotivated questionnaire responding on data quality. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, B.J.; Cardinal, M.K. Screening Efficiency of the Revised Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire in Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 1995, 3, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; Bäck, M.; Börjesson, M.; Caselli, S.; Collet, J.-P.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; Halle, M.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 17–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, O.J.; Tsakirides, C.; Gray, M.; Stavropoulos, K.A. ACSM Preparticipation Health Screening Guidelines: A UK University Cohort Perspective. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, G.; Feito, Y.; Foutaine, C.; Roy, B. (Eds.) ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 Surprising Facts About High Blood Pressure. National Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention. Available online: https://www.cchwyo.org/news/2023/april/5-surprising-facts-about-high-blood-pressure/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, A.; Jenoure, P.J.; Engebretsen, L.; Alonso, J.M.; Bahr, R.; Clough, A.F.; de Bondt, G.; Dvorak, J.; Maloley, R.; Matheson, G.; et al. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on periodic health evaluation of elite athletes. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2009, 19, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J.; Wright, K.; Kelly, M.; Zebrosky, B.; Zanis, M.; Drvol, C.; Butler, R. Injury risk is altered by previous injury: A systematic review of the literature and presentation of causative neuromuscular factors. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 9, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leyk, D.; Hoitz, J.; Becker, C.; Glitz, K.J.; Nestler, K.; Piekarski, C. Health Risks and Interventions in Exertional Heat Stress. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harris, K.M.; Mackey-Bojack, S.; Bennett, M.; Nwaudo, D.; Duncanson, E.; Maron, B.J. Sudden Unexpected Death Due to Myocarditis in Young People, Including Athletes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 143, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, M.; Gin, K. The Cardiovascular System in Heat Stroke. CJC Open 2021, 4, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D’Silva, A.; Papadakis, M. Sudden cardiac death in athletes. Eur. Cardiol. 2015, 10, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risgaard, B.; Winkel, B.G.; Jabbari, R.; Glinge, C.; Ingemann-Hansen, O.; Thomsen, J.L.; Ottesen, G.L.; Haunsø, S.; Holst, A.G.; Tfelt-Hansen, J. Sports-related sudden cardiac death in a competitive and a noncompetitive athlete population aged 12 to 49 years: Data from an unselected nationwide study in Denmark. Heart Rhythm. 2014, 11, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanous, Y.; Dorian, P. The prevention and management of sudden cardiac arrest in athletes. CMAJ 2019, 191, E787–E791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herlitz, J.; Karlson, B.W.; Sjöland, H.; Albertsson, P.; Brandrup-Wognsen, G.; Hartford, M.; Haglid, M.; Karlsson, T.; Lindelöw, B.; Caidahl, K. Physical activity, symptoms of chest pain and dyspnoea in patients with ischemic heart disease in relation to age before and two years after coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001, 42, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.B.; Blom-Hanssen, E.; Gnesin, F.; Kragholm, K.H.; Klitgaard, T.L.; Christensen, H.C.; Lippert, F.; Folke, F.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Ringgren, K.B. Prodromal complaints and 30-day survival after emergency medical services-witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2024, 197, 110155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoliga, J.M.; Mohseni, Z.S.; Berwager, J.D.; Hegedus, E.J. Common causes of dyspnoea in athletes: A practical approach for diagnosis and management. Breathe 2016, 12, e22–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sohail, H.; Ram, J.; Hulio, A.A.; Ali, S.; Khan, M.N.; Soomro, N.A.; Asif, M.; Agha, S.; Saghir, T.; Sial, J.A. Prodromal Symptoms in Patients Presenting with Myocardial Infarction. Cureus 2023, 15, e43732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reinier, K.; Dizon, B.; Chugh, H.; Bhanji, Z.; Seifer, M.; Sargsyan, A.; Uy-Evanado, A.; Norby, F.L.; Nakamura, K.; Hadduck, K.; et al. Warning symptoms associated with imminent sudden cardiac arrest: A population-based case-control study with external validation. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e763–e773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).