Perceived Bullying in Physical Education Classes, School Burnout, and Satisfaction: A Contribution to Understanding Children’s School Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Instruments

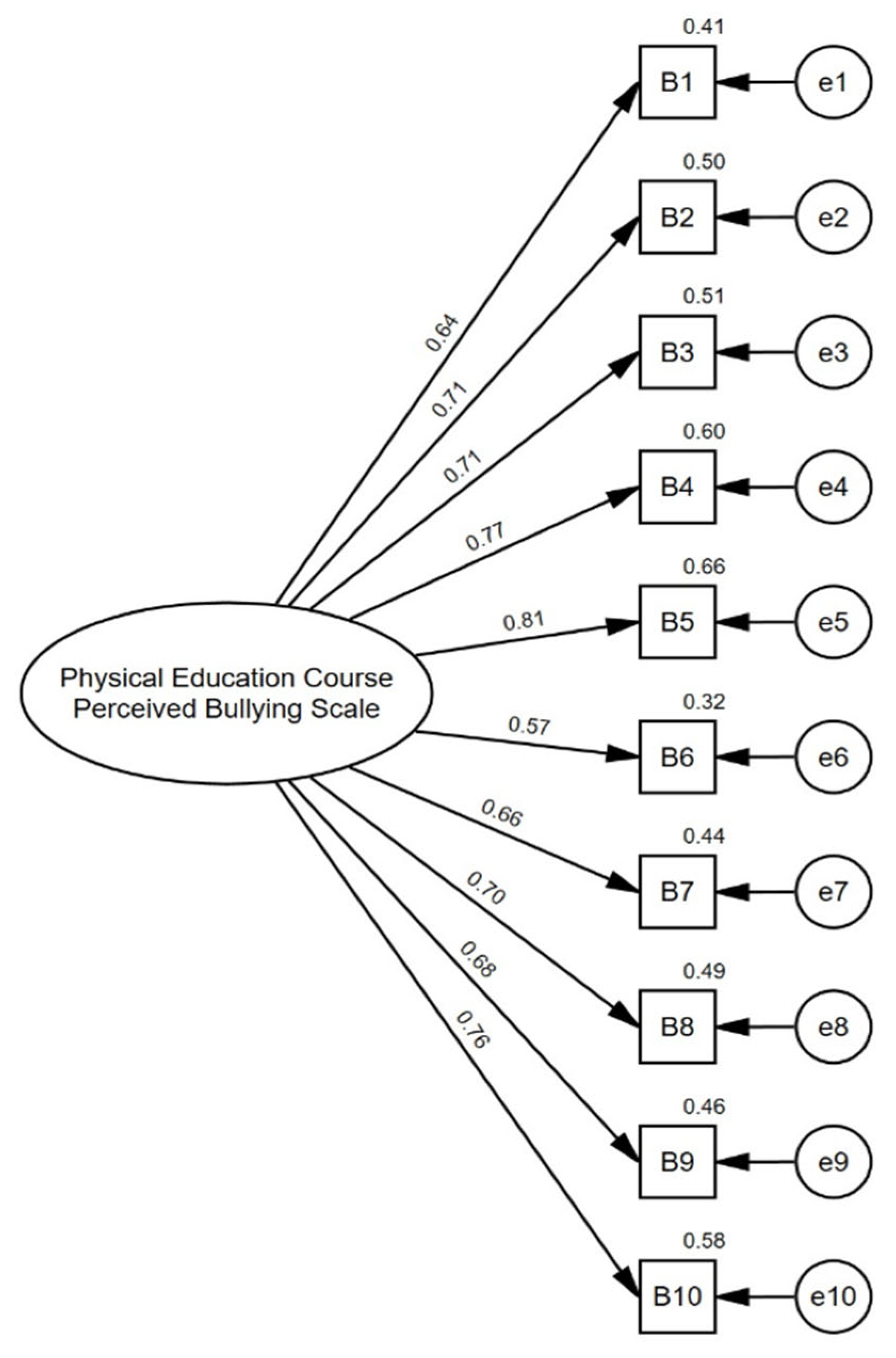

2.3.1. Physical Education Class Perceived Bullying Scale (PECPB)

2.3.2. School Burnout Scale (SB)

2.3.3. Overall School Satisfaction Scale for Children (SS)

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PE | Physical Education |

| PECPB | Physical Education Class Perceived Bullying Scale |

| SS | Overall School Satisfaction Scale for Children |

| SB | School Burnout Scale |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| PES | Physical Education and Sport |

References

- Olweus, D. Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys; Hemisphere Publ. Corp.: London, UK, 1978; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ejsp.2420100124 (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Kaluarachchi, C.; Warren, M.; Jiang, F. Responsible use of technology to combat cyberbullying among young people. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, C.A.; Cowie, H. Bullying at university: The social and legal contexts of cyberbullying among university students. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2017, 48, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Half of World’s Teens Experience Peer Violence in and Around School; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/turkiye/en/press-releases/half-worlds-teens-experience-peer-violence-and-around-school-unicef (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- UNESCO. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. In Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Pişkin, M. Examination of peer bullying among primary and middle school children in Ankara. Educ. Sci. 2010, 35, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, S.; Gregory, T.; Taylor, A.; Digenis, C.; Turnbull, D. The ımpact of bullying victimization in early adolescence on subsequent psychosocial and academic outcomes across the adolescent period: A systematic review. Sch. Violence 2021, 20, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmilasari, F.D.; Winarni, I.; Windarwati, H.D. The susceptibility to mental health problems in the future as a serious effect of bullying on adolescent: A systematic review. Int. J. Sci. Soc. 2020, 2, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qi, J.; Zhen, R. Bullying victimization and adolescents’ social anxiety: Roles of shame and self-esteem. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S. The influence of bullying behavior on depression in middle school students: A moderated mediating effect. J. Phys. Beh. Res. 2021, 3, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Cricchio, M.G.; Zambuto, V.; Palladino, B.E.; Nocentini, A.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Menesini, E. The association between school burnout, school connectedness, and bullying victimization: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2023, 47, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skues, J.L.; Cunningham, E.G.; Pokharel, T. The influence of bullying behaviours on sense of school connectedness, motivation and self-esteem. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 2005, 15, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, D.S.; Boulton, M.J. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousis, I. The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 31, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Jones, A.; Fursa, S.; Byrket, J.S.; Sly, J.S. Bullying affects more than feelings: The long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 18, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pill, S.; Slee, P.T. Sport in Physical Education for Bullying, Harassment and Violence Prevention. In Handbook of Youth Development; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.; Cosma, A.M.; Stepan, R.; Cosma, G.A. The role and importance of physical exercise on the aggression level of high school students. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. 2023, 16, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, E.; Jiménez, T.I.; Musitu, G. Violence and victimization at school in adolescence. In School Psychology; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 79–115. Available online: https://www.uv.es/~lisis/terebel/tj_libro1.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Sağın, A.E.; Uǧraş, S.; Güllü, M. Bullying in physical education: Awareness of physical education teachers. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 2022, 95, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Fominiene, V.B. Bullying trends ınside sport: When organized sport does not attract but intimidates. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.; Lieberman, L.; Haibach-Beach, P.; Perreault, M.; Tirone, K. Bullying in physical education of children and youth with visual impairments: A systematic review. Brit. J. Visual Impa. 2022, 40, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Peterson, J.L.; Luedicke, J. Weight-based victimization: Bullying experiences of weight loss treatment-seeking youth. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesina, O.; Baloun, L.; Kudlacek, M.; Dolezalova, A.; Badura, P. Relationship of exclusion from physical education and bullying in students with specific developmental disorder of scholastic skills. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejerot, S.; Plenty, S.; Humble, A.; Humble, M.B. Poor motor skills: A risk marker for bully victimization. Aggress. Behav. 2013, 39, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øksendal, E.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Holte, A.; Wang, M.V. Associations between poor gross and fine motor skills in pre-school and peer victimization concurrently and longitudinally with follow-up in school age–results from a population-based study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejerot, S.; Ståtenhag, L.; Glans, M.R. Below average motor skills predict victimization from childhood bullies: A study of adults with ADHD. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 153, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. “Not Fair, Not Fun, Not Safe”: Confronting alienation in physical education class. Strategies 2022, 35, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Xiangjing, R. An exploratory study on the effects of ınvisible violence on students’ mental health in physical education. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 8349916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Kiuru, N.; Leskinen, I.E.; Nurmi, E. School-Burnout Inventory: Reliability and Validity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 25, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Nansel, T.R. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S.M.; Espelage, D.L. Introduction: A social-ecological framework of bullying among youth. In Bullying in American Schools; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportelli, C.; Cicirelli, P.G.; Paciello, M.; Corbelli, G.; D’Errico, F. “Let’s make the difference!” Promoting hate counter-speech in adolescence through empathy and digital intergroup contact. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 35, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Graber, K.C. Bullying and physical education: A scoping review. Kinesiol. Rev. 2023, 12, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Barbero, J.A.; Jiménez-Loaisa, A.; González-Cutre, D.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Llor-Zaragoza, L.; Ruiz-Hernández, J.A. Physical education and school bullying: A systematic review. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, L.R.; Houston, J.E.; Steer, O.L. Development of the Multidimensional Peer Victimization Scale-Revised (MPVS-R) and the Multidimensional Peer Bullying Scale (MPVS-RB). J. Genet. Psychol. 2015, 176, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, T.; Dooley, J.J.; Cross, D.; Zubrick, S.R.; Waters, S. The forms of bullying scale (FBS): Validity and reliability estimates for a measure of bullying victimization and perpetration in adolescence. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. 2023. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. 2013. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1760318 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Lashwe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education, Allyn and Bacon: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Available online: https://hisp.htmi.ch/course/view.php?id=543 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.S.; Evmenenko, A.; Andrade, A.; Bento, T.; Vitorino, A.; Couto, N.; Rodrigues, F. Assessment in sport and exercise psychology: Considerations and recommendations for translation and validation of questionnaires. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 806176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, R.K.; Roberts, J.K. Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://books.google.com.tr/books/about/Multivariate_Data_Analysis.html?id=0R9ZswEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secer, İ.; Halmatoc, S.; Veyis, F.; Ates, B. Adaptation of school burnout scale to Turkish culture: A reliability and validity study. Türk. J. Educ. 2013, 2, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Telef, B. Turkish Adaptation Study of Overall School Satisfaction Scale for Children. Theory Pract. Educ. 2014, 10, 478–490. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Wen, Z.; Hau, K.T. Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/scale-development/book269114 (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Arseneault, L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeler, T.; Duncan, L.; Cecil, C.M.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Pingault, J.B. Quasi-experimental evidence on short- and long-term consequences of bullying victimization: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoferichter, F.; Kulakow, S.; Hufenbach, M.C. Support from parents, peers, and teachers is differently associated with middle school students’ well-being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 758226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D.; Parker, P.D.; Hilland, T.; Cinelli, R.; Owen, K.B.; Kapsal, N.; Lee, J.; Antczak, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; et al. Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Han, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B. School connectedness and academic burnout in middle school students: A multiple serial mediation model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, S.; Hallett, V.; Akkas, E.; Akkas, O.A. Bullying and victimization among Turkish children and adolescents: Examining prevalence and associated health symptoms. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2012, 171, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Evans, C.B.R.; Cotter, K.L. The differential impacts of episodic, chronic, and cumulative physical bullying and cyberbullying: The effects of victimization on the school experiences, social support, and mental health of rural adolescents. Violence Vict. 2014, 29, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L.; Marcionetti, J. Life satisfaction and school experience in adolescence: The impact of school supportiveness, peer belonging and the role of academic self-efficacy and victimization. Cogent. Educ. 2024, 11, 2338016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.H.; Gamble, J.H.; Lin, C.Y. Peer victimization’s impact on adolescent school belonging, truancy, and life satisfaction: A cross-cohort international comparison. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1402–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Peer victimization, teacher unfairness, and adolescent life satisfaction: The mediating roles of sense of belonging to school and schoolwork-related anxiety. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, A. Investigating the relationship between social support and school burnout in Turkish middle school students: The mediating role of hope. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2019, 40, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Upadyaya, K. School burnout and engagement in the context of demands-resources model. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, G.; Mediavilla, M.; Giuliodori, D.; Rusteholz, G.C. Bullying at school and students’ learning outcomes: International perspective and gender analysis. J. Interpers. Violence 2024, 39, 2733–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadukapuram, R.; Trivedi, C.; Mansuri, Z.; Shah, K.; Reddy, A.; Jain, S. Bullying victimization in children and adolescents and its impact on academic outcomes. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menken, M.S.; Isaiah, A.; Liang, H.; Rivera, P.R.; Cloak, C.C.; Reeves, G.; Lever, N.A.; Chang, L. Peer victimization (bullying) on mental health, behavioral problems, cognition, and academic performance in preadolescent children in the ABCD Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusteholz, G.; Mediavilla, M.; Jimenez, L.P. Impact of bullying on academic performance: A case study for the community of Madrid. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 1, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J.; Graham, S. Bullying in schools: The power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Luedicke, J. Weight-based victimization among adolescents in the school setting: Emotional reactions and coping behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Sillero, J.D.D.; Corredor-Corredor, D.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Córdoba-Alcaide, F. Behaviours involved in the role of victim and aggressor in bullying: Relationship with physical fitness in adolescents. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Sillero, J.D.; Corredor-Corredor, D.; Córdoba-Alcaide, F.; Calmaestra, J. Intervention programme to prevent bullying in adolescents in physical education classes (PREBULLPE): A quasi-experimental study. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 26, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denysovets, T.; Denysovets, I.; Khomenko, P.; Khlibkevych, S. Preventıon of bulling in the educational environment by means of physical culture and sports. Sci. J. Natl. Pedagog. Dragomanov Univ. Sci. Pedagog. Probl. Phys. Cult. (Phys. Cult. Sports) 2022, 11, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Craig, W. Bullying in youth sports environments. In The Power of Groups in Youth Sport; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, X.; Ventura, C.; Mateu, P. “I Gave up football and ı had no ıntention of ever going back”: Retrospective experiences of victims of bullying in youth sport. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 819981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, C.C.; Oliveira, M.T. Bullying and self-esteem in adolescents from public schools. J. de Pediatria 2013, 89, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachyra, P. Boys, bodies, and bullying in health and physical education class: Implications for participation and well-being. Asia-Pacific J. Health Sport Physic. Educ. 2016, 7, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaka, J.; Blascovich, J.; Kelsey, R.M.; Leitten, C.L. Subjective, physiological, and behavioral effects of threat and challenge appraisal. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolis, B.; Mazzotta, I.; Novielli, N.; Rossano, V. “Engaged Faces”: Measuring and monitoring student engagement from face and gaze behavior. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence-Companion, Thessaloniki, Greece, 14–17 October 2019; Barnaghi, P., Georg, G., Dimitrios, K., Yannis, M., Rahul, P., Theodoros, T., Athena, V., Eds.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.1145/3358695 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

| Variables | PECPB | SS | SB | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PECPB | - | 1.78 | 0.906 | 1.55 | 2.09 | ||

| SS | −0.099 ** | - | 4.00 | 1.08 | −1.09 | 0.548 | |

| SB | 0.359 ** | −0.446 ** | - | 2.22 | 1.05 | 0.824 | −0.0648 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uğraş, S.; Sağın, A.E.; Yücekaya, M.A.; Temel, C.; Mergan, B.; Couto, N.; Duarte-Mendes, P. Perceived Bullying in Physical Education Classes, School Burnout, and Satisfaction: A Contribution to Understanding Children’s School Well-Being. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111285

Uğraş S, Sağın AE, Yücekaya MA, Temel C, Mergan B, Couto N, Duarte-Mendes P. Perceived Bullying in Physical Education Classes, School Burnout, and Satisfaction: A Contribution to Understanding Children’s School Well-Being. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111285

Chicago/Turabian StyleUğraş, Sinan, Ahmet Enes Sağın, Mehmet Akif Yücekaya, Cenk Temel, Barış Mergan, Nuno Couto, and Pedro Duarte-Mendes. 2025. "Perceived Bullying in Physical Education Classes, School Burnout, and Satisfaction: A Contribution to Understanding Children’s School Well-Being" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111285

APA StyleUğraş, S., Sağın, A. E., Yücekaya, M. A., Temel, C., Mergan, B., Couto, N., & Duarte-Mendes, P. (2025). Perceived Bullying in Physical Education Classes, School Burnout, and Satisfaction: A Contribution to Understanding Children’s School Well-Being. Healthcare, 13(11), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111285