Abstract

Background: Physical restraints are known to violate human rights, yet their use persists in long-term care facilities. This study aimed to explore the prevalence, methods, and interventions related to physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes. Methods: The method described by Joanna Briggs was followed to conduct a scoping review without a quality assessment of the selected studies. An electronic search was conducted to find eligible empirical articles using MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, CINAHL, and grey literature. The database search was performed using EndNote software (version X9, Clarivate Analytics), and the data were imported into Excel for analysis. Results: The prevalence of physical restraint use was found to be highest in Spain (84.9%) and lowest in the USA (1.9%). The most common device reported was bed rails, with the highest prevalence in Singapore (98%) and the lowest (4.7%) in Germany, followed by chair restraint (57%). The largest number of studies reported the prevention and/or risk of falls to be the main reason for using physical restraints, followed by behavioral problems such as wandering, verbal or physical agitation, and cognitive impairment. Most studies reported guideline- and/or theory-based multicomponent interventions consisting of the training and education of nursing home staff. Conclusions: This review provides valuable insights into the use of physical restraints among elderly residents in nursing homes. Despite efforts to minimize their use, physical restraints continue to be employed, particularly with elderly individuals who have cognitive impairments. Patient-related factors such as wandering, agitation, and cognitive impairment were identified as the second most common reasons for using physical restraints in this population. To address this issue, it is crucial to enhance the skills of nursing home staff, especially nurses, in providing safe and ethical care for elderly residents with cognitive and functional impairments, aggressive behaviors, and fall risks.

1. Introduction

The increasing number of elderly persons around the world represents a significant public health challenge for many countries. Recent data show that the ageing population is growing much faster than in the past [1]. By 2050, there may be 2.1 billion people aged 60+ and 426 million aged 80 and over [2]. Individuals aged 85 years and older are one of the fastest-growing segments of the population and their numbers are expected to increase to 19.4 million in the United States and 2.7 million in Canada by 2050 [3,4]. Indeed, the population aged 85 and older living in nursing homes has grown by 23.0% since 2011 in Canada [4]. Age-related impairment in physical, cognitive, and functional abilities leads to an increase in dependency among the elderly, primarily due to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. According to a recent study, the number of people living with dementia is estimated to grow to 152.8 million by 2050 [1], and the number of people worldwide with Alzheimer’s disease will be 106.8 million by 2050 [5]. As a result, nursing home use is expected to increase, which will require public health planning and policies that address the long-term care needs of the elderly [5].

With greater numbers of elderly persons in nursing homes, restraint use is a frequently encountered challenge, affecting more than 50% of nursing home residents with five or six activities of daily living (ADL) limitations [6]. The term “restraint” is defined as “a device or medication that is used for the purpose of restricting the movement and/or behavior of a person” [7]. It is also frequently defined as restricting freedom of movement [8]. When considered this way, freedom-restraining devices can be seen as a form of violence [9]. Physical activity is essential for the functioning of older people [10,11]. A decrease in physical activity reduces functional abilities [12]. It increases reliance on caregivers, leading to the increased use of restrictive practices. Among these restrictive practices, physical restraint is often used to address responsive behaviors and prevent falls in places where residents are aged 65 and over and may have cognitive impairment [13,14]. Physical restraint is usually defined as “the use of physical force to prevent, restrict or subdue movement of a care recipient’s body, or part of a care recipient’s body, for the primary purpose of influencing the care recipient’s behavior” [15]. An accepted definition of physical restraint is “any action or procedure that prevents a person’s free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person’s body that he/she cannot control or remove easily” [13]. Examples of physical restraint devices include vests, straps, limb ties, wheelchair bars and brakes, chairs that tip backwards, tightly tucked sheets, bed rails, belts in a chair, belts in bed, hand mitts, wrist restraints, table trays, and sleeping suits [13,16].

The prevalence of physical restraint use in nursing homes was reported to be 37% in Europe, 22% in North America (Robins et al., 2021), 31% in Canada [17], and 20% in Hong Kong. A recent scoping review reported that the physical restraint rate varied between 7.7% and 60.5% in European nursing homes [18]. Such a wide use of physical restraint needs to be reconsidered as it is associated with life-threatening clinical consequences, including head trauma, asphyxiation, and death, as well as legal and ethical concerns such as violating a person’s right to freedom and dignity [16,19,20]. Physically restrained residents had worse outcomes for behavioral issues, cognitive performance, falls, dependency on walking, daily living activities, contractures, urinary and fecal incontinence, deep vein thrombosis, and skin injuries [21,22,23]. Nursing home residents with a history of physical restraint were found to be at higher risk of experiencing cognitive decline [12,24,25], muscular atrophy, increased disorientation [25], decreased mobility, increased mortality [26] and of antipsychotic use [24]. Luo et al. (2020) found that trunk use increased the risk of fractures by almost three times among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease/dementia [27]. Thus, elderly people should be protected from the excessive use of physical restraint [28].

The most common reasons given by nursing home staff for using physical restraint are safety, such as preventing falls or self-injury or harm to others, residents’ inappropriate behavior, such as agitation and wandering, the convenience of the staff, shortages of nurses, the complexity of care, high workloads, lack of knowledge about physical restraint, absence of person-centered care, and lack of legislation/guidelines [7,29,30,31,32,33]. However, empirical studies do not support the use of physical restraint. The evidence shows that a decrease in physical restraint use does not result in more falls or fall-related injuries [34,35,36]. Staff shortages was not a good excuse either: increasing the number of nursing staff did not lead to a reduction in physical restraint [37,38]. In addition, the number of nurses and doctors per patient, the adequacy of staff, and institutional features showed no correlation with physical restraint use [39].

Physical restraint use is recognized as a violation of human rights. Nurses are expected to respect and protect an individual’s autonomy, dignity, and rights [31]. Furthermore, international guidelines and recent studies suggest that a restraint-free nursing home and model of care with reasonable levels of safety is possible, and that physical restraint should not be used unless there is an immediate danger, such as severe imbalance [15,16,25,40]. Yet, physical restraints are still being used in long-term care facilities [8,13,29,41]. There is an increasing amount of research being conducted on the use of restraints in hospitals and intensive care units [42], and on nurses’ knowledge about alternatives to confining residents [28,42]. However, there is little information on the prevalence of and methods used in physical restraint, reasons for using restraints among elderly persons in nursing homes, and interventions to reduce restraint use. Thus, this review is significant in that it contributes to the current literature on physical restraint use in nursing homes by examining the prevalence, types of predictors associated with physical restraint use, and effective interventions used to reduce restraint among elderly nursing home residents. As the population ages, there is a growing need to understand restraint use in long-term care.

1.1. Objectives

This review aimed to map the methods and prevalence of physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes, systematically describe the reasons for using physical restraint, and map interventions and their effectiveness in obviating physical restraint use in nursing homes.

1.2. Research Questions

- What are the prevalence rates and methods of physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes?

- What are the reasons for using physical restraint on the elderly in nursing homes?

- What are the critical gaps in the literature regarding interventions to obviate physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes?

2. Method

2.1. Design

This review mapped the relevant literature on physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes and identified key concepts, research gaps, and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and research. This review employed the following five steps developed by Arksey and O’Malley [43]:

- Identify the research question;

- Identify relevant studies;

- Select studies;

- Extract the data;

- Collate, summarize, and report the results.

2.2. Search Methods

The method described by Joanna Briggs was followed to conduct a scoping review without a quality assessment of the selected studies [44]. Keywords and MeSH terms were identified through an initial exploration of Web of Science and PubMed. The terms were reviewed and agreed upon by the research team and the librarian from Izmir Tinaztepe University. After agreeing on the search terms, an electronic search was conducted to find eligible empirical articles using MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, CINAHL, and grey literature by the librarian. The term “physical restraint” covered all restraints and was not differentiated as with or without a bed rail (bilateral/unilateral). The search strategy included the following search terms: “elderly” OR “old*” OR “resident*” OR “aged” OR “nursing home residents” OR “restraint*” OR “restrictive practices” OR “physical restraint*”, “nursing home*” OR “long-term care*” OR “long-term care facilities” OR “type” OR “reason” OR predictors, OR “risks” OR “intervention”.

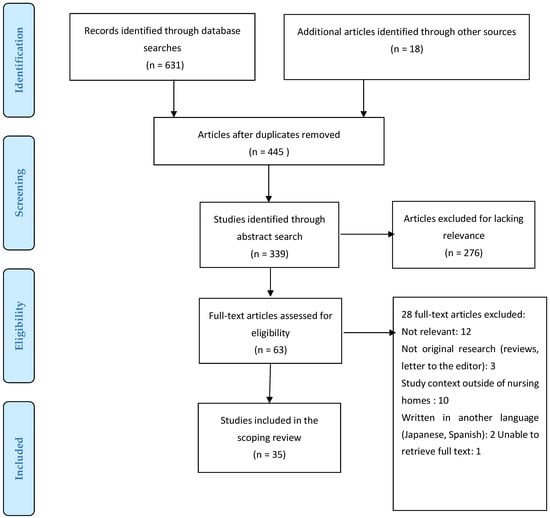

The database search was performed using EndNote software (version X9, Clarivate Analytics). As a result of the search, 871 studies were identified, of which 63 remained after all the titles and abstracts were assessed and duplicates were removed. PRISMA (Figure 1) shows the study selection process for inclusion in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In the literature, restraint methods are classified as physical, mechanical, chemical, environmental, and seclusion [15]. In this review, physical restraint is defined as anything attached to a person’s body to restrict or control movement/behavior, or other physical barriers such as bed rails [45]. Therefore, those studies that define a physical restraint as something attached to a person’s body or as a physical barrier restricting movement or behavior were included in this scoping review. It is essential to understand that the criteria for determining “old age” can vary across nations, influenced by age-related demographics and cultural views. Different nations might define this age benchmark based on elements like life expectancy, societal roles, retirement norms, or health indicators. In this study, we did not specifically classify the age constituting older adults. The review sought to identify peer-reviewed primary studies concerning the prevalence and type of physical restraint used among elderly people living in nursing homes, factors affecting the use of physical restraint, and interventions employed to reduce physical restraint use. The scoping review searched for primary research studies published during 2000–2021 with a title and/or keywords that included “physical restraint” and/or “elderly in nursing homes”. Articles published in English were included. The excluded items were studies that did not sample elderly residents in nursing homes, were published in languages other than English, were published as review articles, were letters to the editor, conference papers, editorials, protocols, commentaries, or expert opinions, or that were impossible to retrieve as complete articles or book chapters.

2.4. Study Selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to select the studies selected. The selected abstracts were screened and read mainly by the two authors (GH, SK). The same authors independently reviewed the full text of the articles for inclusion, and any disagreements (eight full-text articles) were resolved through discussion until a consensus was achieved by all three researchers (GH, SK, DMP). It was decided that 28 of the 63 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria should not be included. On completion of the review process, 35 articles were identified for charting. The selected articles were analyzed according to year, country, setting, sample, method, and three outcomes (methods and prevalence of physical restraint, reasons for using physical restraint, and interventions), as determined using previous literature.

2.5. Charting the Data

A data charting form was developed to facilitate the extraction of the author/year, title, research location, aim/purpose, method, prevalence, type of physical restraint used among the elderly residents of nursing homes, risk factors, and interventions to reduce physical restraint use. All the data from the charting form was imported into Excel for analysis. This review’s final stage consisted of a results summary and thematic analysis. The data in this scoping review were charted, analyzed and summarized by using the PAGER framework suggested by Bradburry-Jones et al. (2021) [46]. The PAGER framework was suggested to improve the quality of the review and guide future research about the advances and gaps related to the topic of the review. We specifically focused on the “Gap”, “Evidence”, and “Research” steps in this study. To visually enhance our presentation, we created a table detailing the gaps, evidence, and future research areas in our review.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

This review retrieved 631 articles on physical restraint use among elderly nursing home residents via databases, together with 18 articles identified via a web search and a search of grey literature. Of the 649 retrieved articles, 35 met the inclusion criteria. Of those, the majority (11) had a cross-sectional design. Thirty of the articles were published between 2010 and 2022. The largest number of articles, 12, originated from Germany and the Netherlands, followed by the United States (4), Australia (2), Canada (3), China (3), and Norway (4). Two studies sampled residents from nursing homes in multiple countries. Sample sizes ranged from 264,068 to 5 residents, depending on the study’s design. Of the 35 included articles, 26 reported on the prevalence of physical restraint use, 26 studied methods of physical restraint, and 10 were studies on interventions to reduce physical restraints among elderly residents in nursing homes.

3.2. Prevalence and Types of Physical Restraint Use

The 26 studies providing data about the type and prevalence of physical restraint use originated from 22 countries. Two studies were multi-country, and the rest were single studies from Australia, Canada, China, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. The prevalence of physical restraint use was found to be highest in Spain (84.9%) and lowest in the USA (1.9%). A variety of restraint devices were reported in nursing homes, including bed rails, belts, trunk and chair restraints, pelvic straps in an armchair, tight bed sheets, side rails, fixed tables, vest restraints, sleep suits, bed belts, and many others. The most common device reported was bed rails, which appeared in 11 articles, with the highest prevalence in Singapore (98%) and the lowest (4.7%) in Germany. The second most commonly used method was chair restraint; the highest prevalence was reported to be 57%. Trunk use was reported in 5 studies, with the highest prevalence being 45%. Daily limb and/or trunk restraint use was reported to be 12% in Italy, 8% in Belgium, 4% in Finland, 1% in England, 0.4% in Poland, and 0% in the Netherlands. Limb restraints were the least popular; their use was reported to be 1.2% in Spain and 0.3% in China. The highest prevalence values of fixed table, belt restraint, belt in bed, sleeping suit and sheet in bed, and vest were 36%, 27%, 9.9%, 4%, and 6.1%, respectively. In one study, a pelvic strap in an armchair was reported to have been employed against elderly nursing home residents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Type and prevalence of physical restraints used against elderly residents of nursing homes.

3.3. Reasons for Physical Restraint Use

Of the 35 included articles, the 18 published between 2007 and 2020 reported the reasons for using physical restraint in Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Finland, Israel, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. The following reasons were given for restraining the patients: age, care dependency, level of disablement, impaired activities of daily living, cognitive status, dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, negative mood, hallucinations, delusions, disorientation/confusion, depression, preventing dislodgement of feeding tubes, safe use of medical devices, workload, staff culture, location and availability of human resources, negative experiences of nurses, concerns and uncertainties of relatives and legal guardians, and organizational problems such as staff fluctuations and shortages of physicians. The largest number of studies (13) reported the prevention and/or risk of falls to be the main reason for using physical restraints, followed by behavioral problems such as wandering (7), verbal or physical agitation (6), being verbally or physically abusive (1), injury to others (1), shouting, restlessness, aggressiveness, disrobing in public, and resisting care (1), functional impairment (1), urinary or fecal incontinence (3), hip fracture/fall-related fractures (2), history of falls (1), bedfast (1), and being untidy (1). The risk of self-injury was reported in three studies (Finland, Israel, and Singapore) as being the reason for using restraints. One study in Germany reported on the necessity of restraining a patient due to polypharmacy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reasons given for using physical restraint.

3.4. Interventions to Reduce Physical Restraint Use

Interventions to reduce physical restraint use in nursing homes were identified in 10 studies: Germany (3), the Netherlands (4), Norway (1), Spain (1), and Sweden (1). Most studies reported guideline- and/or theory-based multicomponent interventions consisting of the training and education of nursing home staff, including nurses, licensed practical nurses, nurses’ aides, physicians, etc. Other interventions included institutional policy changes to discourage the use of physical restraints, consultation, surveillance technology, and small-scale living facilities. Some of the educational intervention studies showed that it is possible to eliminate or reduce physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes [35,40,54,55,58,60], while others reported just the opposite [47,52]. A study from Germany used an intervention to prevent behavioral symptoms and fall injuries by educating nursing home staff using a 6-h training course and technical aids, such as hip protectors and sensor mats [54]. A study from the Netherlands suggested the positive effects of small-scale, home-like facilities [63]. Another study suggested that surveillance technology would give residents with dementia more freedom of movement and should be considered before physical restraint [62] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of interventions to reduce physical restraints, their effectiveness and challenges.

3.5. The PAGER Analysis

The patterns, advances, gaps, evidence for practice and research recommendations are shown in Table 4. The results were summarized under four patterns. These included the prevalence, types of physical restraint, factors affecting physical restraint use, and interventions to reduce physical restraint use in elderly residents in nursing homes. This review showed that there is strong evidence supporting the substantial use of PR with a variety of physical restraint devices in nursing homes, particularly from studies in countries with large elderly populations. Studies on interventions focused on training and education programs for nursing home staff.

Table 4.

Summary of the review according to the PAGER framework.

4. Discussion

This review study aimed to examine the prevalence and methods of physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes. It systematically describes the reasons for using physical restraint, and maps interventions and their effectiveness in avoiding its use in nursing homes.

This review revealed the diversity of devices used to restrain the elderly in nursing homes. The prevalence of physical restraint varied widely across countries, ranging from 1.9% in the USA to 84.5% in Spain. Our findings aligned with the literature [42,66]. The Nursing Home Reform Act (1987), which gave nursing home residents the right to be free from restraints employed for disciplinary purposes or for the convenience of staff, helped reduce the rate of restraint use. This explains the low level of restraint use in the USA. It is well established in the literature that physical restraint remains common in nursing homes despite their lack of effectiveness or safety, and should be used only if there are no alternatives [19,35,52,67,68,69]. The most common arguments against restraint-free elderly care were debunked in the Editorial, “Zero tolerance for physical restraints: Difficult but not impossible”. The article argued that unrestrained care is possible and should be part of standard care for all older people [70]. Sadly, this scoping review revealed the continuing popularity of physical restraint. According to Marques and colleagues, the prevention of falls is often considered an indicator of quality of care [71]. Therefore, physical restraint may be used to decrease falls and thus make the nursing home staff look good.

This study found that bed rails are physical restraint device used most frequently among the elderly. Bed rails were more common in the Netherlands [29,35,52] and Spain [48] than in Germany [47] and Switzerland [41]. These findings are consistent with previous studies focusing on physical restraint use in nursing homes [20,28,45,66,71]. Although bed rails may seem harmless, and even help one to sleep better by eliminating the fear of falling out of bed, injuries can still occur, such as getting caught between the rails [19,72]. Recent studies have revealed that the use of bed rails is contraindicated because there is no scientific evidence supporting their effectiveness in preventing injuries among older adults [45,69,71,73]. Side rails are suggested only if the patient has freedom of movement and can exit the bed by removing the rails or if patients use them to reposition themselves [74]. The use of bed rails may also impair the dignity and autonomy of the elderly. Although the decision to impose bed rails is made by physicians, nurses, who are part of the decision-making process, are responsible for the implementation and control of physical restraint and protecting the rights of the elderly residents. Bed rails should only be used as a last resort, and even then with a doctor’s order; this is to avoid the loss of dignity, self-respect, self-confidence and self-esteem [71]. Bed rails should not be used for people with impaired cognitive function or dementia/Alzheimer’s disease without first considering alternative strategies, such as lowering the bed height [19,74].

Identifying reasons for using physical restraint among the elderly in nursing homes is crucial before considering interventions to replace them. Most of the studies in this review reported preventing falls as the main reason for using physical restraint. This finding is consistent with the literature [29,67,74]. Falls are common among the elderly due to age-related changes, such as impaired gait and balance, weak muscles, and impaired vision. The risk of falling increases after 60 years of age [75,76,77]. In contrast, studies have reported that fall prevention is not enough to justify physical restraint due to it being ineffective in reducing injuries [29,78,79]. Indeed, falls are one of the consequences of being physically restrained [22,77]. On the other hand, in the case of active older people with cognitive impairment, the risk of falling may increase [78]. Yet, other studies have provided strong evidence that fall rates can be reduced by resistance exercises with balance training and muscle strengthening in the lower extremities [48,80,81].

The second most common rationale for using physical restraints was patient-related factors such as wandering, agitation, and cognitive impairment. Similar results were seen in previous studies [14,42,49]. While the behaviors of the elderly may be a factor, studies have also shown that using physical restraint triggers aggressive behaviors in older people [82,83]. According to a new law in Switzerland, threatening injury to oneself or others is the only acceptable reason to physically restrain older persons [41].

This review revealed a few simple interventions to reduce physical restraint use among the elderly in nursing homes. Most of the interventions involved training and education programs for nursing home staff. Unfortunately, owing to the design and sample of the study, the effectiveness of the interventions was found to be inconclusive. The result was in line with recent studies on the same subject [61,84]. A study assessing the association between surveillance technology and restraint found no significant relationship [68]. A recent review reported that physical restraint-free care is possible by creating environments that meet the needs of older people with mobility and cognitive impairments, and that promote patient safety [85]. This finding is supported by Evans and Cotter [73], who stated that reducing the use of physical restraint depends on a multitude of interventions. Individuals with dementia can be managed without the use of restraints, no matter the environment, by creating a tailored care approach that addresses and anticipates their unique needs and behaviors. This approach can be complemented by organizational reforms. Additionally, tools like video monitoring and electronic alert systems offer added protection to prevent falls among the elderly [58,86]. According to O’Keeffe [69], preventing falls is possible by improving the education and guidance provided to staff. The author also called for further efforts to educate staff, informing them that using bed rails is an uncertain and insecure approach to preventing people from falling out of bed. Thus, there is a continuing need for effective interventions to reduce physical restraint use in elderly nursing home residents [17]. Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, the results of this scoping review were limited to the key search terms used in the research and focused on studies published between 2000 and 2021. Second, this study did not differentiate between studies with or without bed rails, which may have also affected the reporting of physical restraint use in nursing homes. Third, the authors may have missed some crucial evidence due to the limited language criteria. Fourth, we recognize that there is significant variance in the level of evidence across various study designs. However, in this review, we did not analyze the results based on the study design. Lastly, no quality assessment was performed on the articles. In contrast, the main strength of this review lies in its use of the PAGER framework, which guides future researchers regarding the advances and gaps present in the research, offers suggestions for future research regarding the topic of the review, and achieves consensus through discussions among researchers.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review provides valuable insights into the use of physical restraints among elderly residents in nursing homes. Despite efforts to minimize their use, physical restraints continue to be employed, particularly with elderly individuals who have cognitive impairments. Patient-related factors such as wandering, agitation, and cognitive impairment were identified as the second most common reasons for using physical restraints in this population. To address this issue, it is crucial to enhance the skills of nursing home staff, especially nurses, so that they can provide safe and ethical care for elderly residents with cognitive and functional impairments, aggressive behaviors, and fall risks.

The ongoing use of physical restraints for fall prevention, despite lacking scientific evidence, raises ethical concerns. To address this, it is recommended that clear directives are provided to nursing home staff based on the latest evidence-based practices and interventions for fall prevention. These directives should emphasize the safety, rights, and dignity of the residents, ensuring that physical restraints are only considered as a last resort when no alternatives are available. Additionally, implementing mandatory training programs for nursing home staff is essential. This training should focus on recognizing and responding to the individual needs and behaviors of residents with cognitive impairments, emphasizing person-centered care approaches. Understanding and addressing the underlying causes of behaviors that lead to restraint use is crucial. Person-centered interventions and environmental modifications should be adopted to effectively address these causes. By creating an environment that supports individualized care plans and promotes autonomy and well-being, the need for physical restraints can be minimized.

Implementing these policy suggestions will enable nursing homes to create a safe, supportive, and person-centered environment that upholds the rights and dignity of elderly residents. A study by Laurin et al. suggested that interviewing nursing staff is a reliable method of data collection for measuring physical restraint use among residents [66]. Thus, further research is required on the experiences of nurses when managing such residents in order to guide the ethically and clinically challenging decision to use physical restraint.

Author Contributions

G.H.Y., S.K. and D.M.P.: Conceptualization, design of the study and search strategy development. S.K. and G.H.Y.: Database searching and study selection. G.H.Y., S.K. and D.M.P.: Data extraction, analysis, and data analysis with the PAGER framework. S.K. and D.M.P.: First draft preparation. G.H.Y., S.K. and D.M.P.: Writing original draft, preparation and critical review of the manuscript. D.M.P.: Study supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- GBD. Global, regional, and national burden of diseases and injuries for adults 70 years and older: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068208. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Ageing and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Friedland, R.B. Selected Long-Term Care Statistics. 2005. Available online: https://www.caregiver.org/resource/selected-long-term-care-statistics/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- STATCAN. A Portrait of Canada’s Growing Population Aged 85 and Older from the 2021 Census. 2022. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021004/98-200-x2021004-eng.cfm (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Brookmeyer, R.; Johnson, E.; Ziegler-Graham, K.; Arrighi, H.M. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2007, 3, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, W.J. A perspective on long-term care for the elderly. Health Care Financ. Rev. 1988, 1988, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, J.; Wimmer, B.C.; Smit, C.C.; Courtney-Pratt, H.; Lawler, K.; Salmon, K.; Price, A.; Goldberg, L.R. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Restraint Use in Aged Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkema, N.; Niemeijer, A.; Frederiks, B.; Schipper, C. Exploring restrictive measures using action research: A participative observational study by nursing staff in nursing homes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2785–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzlanovich, A.M.; Schöpfer, J.; Keil, W. Deaths due to physical restraint. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 2012, 109, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, B.; Bergland, A.; Rydwik, E. The Importance of Physical Activity Exercise among Older People. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7856823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, J.S.; French, D.P.; Jackson, D.; Nazroo, J.; Pendleton, N.; Degens, H. Physical activity in older age: Perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, G.A.; Crizzle, A.M.; Chen, J.; Pringsheim, T.; Jette, N.; Kergoat, M.J.; Eckel, L.; Hirdes, J.P. Clinical Complexity and Use of Antipsychotics and Restraints in Long-Term Care Residents with Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleijlevens, M.H.C.; Wagner, L.M.; Capezuti, E.; Hamers, J.P.H. Physical Restraints: Consensus of a Research Definition Using a Modified Delphi Technique. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2307–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Longhini, J.; Businarolo, A.; Piccin, T.; Pitacco, G.; Bicego, L. Between Restrictive and Supportive Devices in the Context of Physical Restraints: Findings from a Large Mixed-Method Study Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Department of Health and Aged Care (ADAHC), Restrictive Practices in Aged Care—A Last Resort. 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/aged-care/providing-aged-care-services/working-in-aged-care/restrictive-practices-in-aged-care-a-last-resort (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Bellenger, E.; Ibrahim, J.E.; Bugeja, L.; Kennedy, B. Physical restraint deaths in a 13-year national cohort of nursing home residents. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Hirdes, J.P.; Smith, T.F.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Chi, I.; Du Pasquier, J.-N.; Gilgen, R.; Ikegami, N.; Mor, V. Use of physical restraints and antipsychotic medications in nursing homes: A cross-national study. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosi, E.; Debiasi, M.; Longhini, J.; Giori, L.; Saiani, L.; Mezzalira, E.; Canzan, F. Variation of the Occurrence of Physical Restraint Use in the Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastmans, C.; Milisen, K. Use of physical restraint in nursing homes: Clinical-ethical considerations. J. Med. Ethics 2006, 32, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzlanovich, A.M.; Kirsch, S.; Schöpfer, J.; Keil, W.; Kohls, N. Freedom-restraining measures as a result of misguided concern? Use of physical restraint in care situations. MMW Fortschr. Med. 2012, 154, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, N.G.; Engberg, J. The health consequences of using physical restraints in nursing homes. Med. Care 2009, 47, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Hahn, S. Characteristics of nursing home residents and physical restraint: A systematic literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 3012–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, K.; Lim, J. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes: Current practice in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2005, 34, 158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Foebel, A.D.; Onder, G.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Lukas, A.; Denkinger, M.D.; Carfi, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Brandi, V.; Bernabei, R.; Liperoti, R. Physical Restraint and Antipsychotic Medication Use Among Nursing Home Residents with Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 184.e9–184.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Spirgiene, L.; Martin-Khan, M.; Hirdes, J.P. Relationship between restraint use, engagement in social activity, and decline in cognitive status among residents newly admitted to long-term care facilities. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, L.M.; Lee, D.-C.A.; Bell, J.S.; Srikanth, V.; Möhler, R.; Hill, K.D.; Haines, T.P. Definition and Measurement of Physical and Chemical Restraint in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Lin, M.; Castle, N. Physical restraint use and falls in nursing homes: A comparison between residents with and without dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2011, 26, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- De Veer, A.J.; Francke, A.L.; Buijse, R.; Friele, R.D. The use of physical restraints in home care in the Netherlands. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 1881–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamers, J.P.; Huizing, A.R. Why do we use physical restraints in the elderly? Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2005, 38, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kor, P.P.K.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; Liu, J.Y.W.; Lai, C. Knowledge, Practice, and Attitude of Nursing Home Staff toward the Use of Physical Restraint: Have They Changed over Time? J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Nurses Association (ANA). The Ethical Use of Restraints: Balancing Dual Nursing Duties of Patient Safety and Personal Safety. 2020. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/48f80d/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/nursing-excellence/ana-position-statements/nursing-practice/restraints-position-statement.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Øye, C.; Jacobsen, F.F. Informal use of restraint in nursing homes: A threat to human rights or necessary care to preserve residents’ dignity? Health 2020, 24, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Gong, D.; Jiang, S.; Li, J.; Xu, H. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Nursing Home Staff Regarding Physical Restraint in China: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 815964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capezuti, E.; Maislin, G.; Strumpf, N.; Evans, L.K. Side rail use and bed-related fall outcomes among nursing home residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulpers, M.J.M.; Bleijlevens, M.H.C.; Ambergen, T.; Capezuti, E.; van Rossum, E.; Hamers, J.P.H. Belt restraint reduction in nursing homes: Effects of a multicomponent intervention program. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinagh, R.; Slevin, E.; McCormack, B. Side rails as physical restraints in the care of older people: A management issue. J. Nurs. Manag. 2002, 10, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizing, A.R.; Hamers, J.P.; de Jonge, J.; Candel, M.; Berger, M.P. Organisational determinants of the use of physical restraints: A multilevel approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinze, C.; Dassen, T.; Grittner, U. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes and hospitals and related factors: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unruh, L.; Joseph, L.; Strickland, M. Nurse absenteeism and workload: Negative effect on restraint use, incident reports and mortality. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, R.; Gómez, S.; Curto, D.; Hernández, R.; Marco, B.; García, P.; Tomás, J.F.; Olazarán, J. Reducing Physical Restraints in Nursing Homes: A Report from Maria Wolff and Sanitas. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, H.; Schorro, E.; Haastert, B.; Meyer, G. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-I.; Jung, H.-K.; Kim, C.O.; Kim, S.-K.; Cho, H.-H.; Kim, D.Y.; Ha, Y.-C.; Hwang, S.-H.; Won, C.W.; Lim, J.-Y.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines for fall prevention in Korea. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.; Lee, O.N.; An, P.M.; Ens, T.A.; Mannion, C.A. Bedrails and Falls in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Aveyard, H.; Herber, O.R.; Isham, L.; Taylor, J.; O’malley, L. Scoping reviews: The PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2022, 25, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Kupfer, R.; Behncke, A.; Berger-Höger, B.; Icks, A.; Haastert, B.; Meyer, G.; Köpke, S.; Möhler, R. Implementation of a multicomponent intervention to prevent physical restraints in nursing homes (IMPRINT): A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 96, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Gallardo, M.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; de Luna-Rodriguez, M.E.; Vazquez-Blanco, M.J.; Morilla-Herrera, J.C.; Rivas-Ruiz, F.; Toribio-Montero, J.C.; Canca-Sanchez, J.C. Characteristics, consequences and prevention of falls institutionalised older adults in the province of Malaga (Spain): A prospective, cohort, multicentre study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvalle, R.; Santana, R.F.; Menezes, A.K.; Cassiano, K.M.; De Carvalho, A.C.S.; Barros, P.D.F.A. Mechanical Restraint in Nursing Homes in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl. S3), e20190509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez-Guerra, G.J.; Fariña-López, E.; Núñez-González, E.; Gandoy-Crego, M.; Calvo-Francés, F.; Capezuti, E.A. The use of physical restraints in long-term care in Spain: A multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, P.; Van de Water, G.; De Paepe, L.; Boonen, S.; Vleugels, A.; Milisen, K. Staffing levels and the use of physical restraints in nursing homes: A multicenter study. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 40, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizing, A.R.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Gulpers, M.J.M.; Berger, M.P.F. A cluster-randomized trial of an educational intervention to reduce the use of physical restraints with psychogeriatric nursing home residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkevold, Ø.; Engedal, K. Prevalence of patients subjected to constraint in Norwegian nursing homes. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczy, P.; Becker, C.; Rapp, K.; Klie, T.; Beische, D.; Büchele, G.; Kleiner, A.; Guerra, V.; Rißmann, U.; Kurrle, S.; et al. Effectiveness of a Multifactorial Intervention to Reduce Physical Restraints in Nursing Home Residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpke, S.; Mühlhauser, I.; Gerlach, A.; Haut, A.; Haastert, B.; Möhler, R.; Meyer, G. Effect of a guideline-based multicomponent intervention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012, 307, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Kwan, J.S.K.; Kwan, C.W.; Chong, A.M.L.; Lai, C.K.Y.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Liu, J.Y.W.; Bai, X.; Chi, I. Factors Associated With the Trend of Physical and Chemical Restraint Use Among Long-Term Care Facility Residents in Hong Kong: Data From an 11-Year Observational Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, G.; Köpke, S.; Haastert, B.; Mühlhauser, I. Restraint use among nursing home residents: Cross-sectional study and prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellfolk, T.J.-E.; Gustafson, Y.; Bucht, G.; Karlsson, S. Effects of a restraint minimization program on staff knowledge, attitudes, and practice: A cluster randomized trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivodic, L.; Smets, T.; Gambassi, G.; Kylänen, M.; Pasman, H.R.; Payne, S.; Szczerbińska, K.; Deliens, L.; Van den Block, L. Physical restraining of nursing home residents in the last week of life: An epidemiological study in six European countries. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 104, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testad, I.; Mekki, T.E.; Førland, O.; Øye, C.; Tveit, E.M.; Jacobsen, F.; Kirkevold, Ø. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)-training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Tong, J.; Zhao, Q.; Xiao, M. Effects and implementation of a minimized physical restraint program for older adults in nursing homes: A pilot study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 959016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Boekhorst, S.; Depla, M.F.I.A.; Francke, A.L.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Zwijsen, S.A.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M. Quality of life of nursing-home residents with dementia subject to surveillance technology versus physical restraints: An explorative study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; van Rossum, E.; Ambergen, T.; Kempen, G.I.; Hamers, J.P. Effects of small-scale, home-like facilities in dementia care on residents’ behavior, and use of physical restraints and psychotropic drugs: A quasi-experimental study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Natan, M.; Akrish, O.; Zaltkina, B.; Noy, R.H. Physically restraining elder residents of long-term care facilities from a nurses’ perspective. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 16, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarnio, R.; Isola, A. Nursing staff perceptions of the use of physical restraint in institutional care of older people in Finland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 3197–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, D.; Voyer, P.; Verreault, R.; Durand, P.J. Physical restraint use among nursing home residents: A comparison of two data collection methods. BMC Nurs. 2004, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.; Wood, J.; Lambert, L. Patient injury and physical restraint devices: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favez, L.; Simon, M.; Bleijlevens, M.H.; Serdaly, C.; Zúñiga, F. Association of surveillance technology and staff opinions with physical restraint use in nursing homes: Cross-sectional study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 2298–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, S.T. Physical restraints and nursing home residents: Dying to be safe? Age Ageing 2017, 46, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, J.H. Zero Tolerance for Physical Restraints: Difficult but Not Impossible. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2004, 59, M919–M920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.; Queirós, C.; Apóstolo, J.; Cardoso, D. Effectiveness of bedrails in preventing falls among hospitalized older adults: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2017, 15, 2527–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallinagh, R.; Nevin, R.; Mc Ilroy, D.; Mitchell, F.; Campbell, L.; Ludwick, R.; McKenna, H. The use of physical restraints as a safety measure in the care of older people in four rehabilitation wards: Findings from an exploratory study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonad, E.; Wahlin, T.-B.R.; Winblad, B.; Emami, A.; Sandmark, H. Falls and fall risk among nursing home residents. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.K.; Cotter, V.T. Avoiding restraints in patients with dementia: Understanding, prevention, and management are the keys. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Marx, E.M.; Strumpf, N.E.; Evans, L.K.; Baumgarten, M.; Maislin, G. Predictors of continued physical restraint use in nursing home residents following restraint reduction efforts. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L.Z. Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. S2), ii37–ii41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoberer, D.; Breimaier, H.E.; Zuschnegg, J.; Findling, T.; Schaffer, S.; Archan, T. Fall prevention in hospitals and nursing homes: Clinical practice guideline. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2022, 19, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, T.W.; Leng, C.Y.; Lin, S.K.S. The effectiveness of physical restraints in reducing falls among adults in acute care hospitals and nursing homes: A systematic review. JBI Libr. Syst. Rev. 2012, 10, 307–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Ibáñez, J.M.; Morales Ballesteros, M.D.C.; Montiel Moreno, M.; Mora Sánchez, E.; Arias Arias, Á.; Redondo González, O. Physical restraint use in relation to falls risk in a nursing home. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2020, 55, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, C.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Fairhall, N.; Paul, S.S.; Tiedemann, A.; Whitney, J.; Cumming, R.G.; Herbert, R.D.; Close, J.C.T.; Lord, S.R. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Izumi, K.; Shirai, S.; Kondo, K.; Kanda, M.; Watanabe, I.; Ishii, K.; Saito, R. Development of a fall prevention program for elderly Japanese people. Nurs. Health Sci. 2008, 10, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, P.; Verreault, R.; Azizah, G.M.; Desrosiers, J.; Champoux, N.; Bédard, A. Prevalence of physical and verbal aggressive behaviours and associated factors among older adults in long-term care facilities. BMC Geriatr. 2005, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryden, M.B.; Feldt, K.S.; Oh, H.L.; Brand, K.; Warne, M.; Weber, E.; Nelson, J.; Gross, C. Relationships between aggressive behavior in cognitively impaired nursing home residents and use of restraints, psychoactive drugs, and secured units. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1999, 13, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, L.K.; Strumpf, N.E.; Allen-Taylor, S.L.; Capezuti, E.; Maislin, G.; Jacobsen, B. A clinical trial to reduce restraints in nursing homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1997, 45, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Hirt, J.; Richter, C.; Köpke, S.; Meyer, G.; Möhler, R. Interventions for preventing and reducing the use of physical restraints of older people in general hospital settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 8, CD012476. [Google Scholar]

- Woltsche, R.; Mullan, L.; Wynter, K.; Rasmussen, B. Preventing Patient Falls Overnight Using Video Monitoring: A Clinical Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).