Abstract

In this paper, we introduce generalized quadratic forms and hyperconics over quotient hyperfields as a generalization of the notion of conics on fields. Conic curves utilized in cryptosystems; in fact the public key cryptosystem is based on the digital signature schemes (DLP) in conic curve groups. We associate some hyperoperations to hyperconics and investigate their properties. At the end, a collection of canonical hypergroups connected to hyperconics is proposed.

MSC:

20N20; 14H52; 11G05

1. Introduction

In 1934, Marty initiated the notion of hypergroups as a generalization of groups and referred to its utility in solving some problems of groups, algebraic functions and rational fractions [1]. To review this theory one can study the books of Corsini [2], Davvaz and Leoreanu-Fotea [3], Corsini and Leoreanu [4], Vougiouklis [5] and in papers of Hoskova and Chvalina [6] and Hoskova-Mayerova and Antampoufis [7]. In recent years, the connection of hyperstructures theory with various fields has been entered into a new phase. For this we advise the researchers to see the following papers. (i) For connecting it to number theory, incidence geometry, and geometry in characteristic one [8,9,10]. (ii) For connecting it to tropical geometry, quadratic forms [11,12] and real algebraic geometry [13,14]. (iii) For relating it to some other objects see [15,16,17,18,19]. M. Krasner introduced the concept of the hyperfield and hyperring in Algebra [20,21]. The theory which was developed for the hyperrings is generalizing and extending the ring theory [22,23,24,25]. There are different types of hyperrings [22,25,26]. In the most general case a triplet is a hyperring if is a hypergroup, is a semihypergroup and the multiplication is bilaterally distributive with regards to the addition [3]. If is a semigroup instead of semihypergroup, then the hyperring is called additive. A special type of additive hyperring is the Krasner’s hyperring and hyperfield [20,21,24,27,28]. The construction of different classes of hyperrings can be found in [29,30,31,32,33]. There are different kinds of curves that basically are used in cryptography [34,35]. An elliptical curve is a curve of the form , where is a cubic polynomial with no-repeat roots over the field F. This kind of curves are considered and extended over Krasner’s hyperfields in [13]. Now let and be the quadratic equation of two variables in field of F, if and then the equation is called homographic transformation. In [14] Vahedi et. al extended this particular quadratic equation on Krasner’s quotient hyperfield The motivation of this paper goes in the same direction of [14]. If in the general form of the equation of quadratic form one suppose that and then initiate an important quadratic equation which is called a conic. Notice that the conditions which are considered for the coefficients of the equations of a conic curve and a homographic curve are completely different. Until now the study of conic curves has been on fields. At the recent works the authors have investigated some main classes of curves; elliptic curves and homographics over Krasner’s hyperfields (see [13,14]). In the present work, we study the conic curves over some quotients of Krasner’s hyperfields.

2. Preliminaries

In the following, we recall some basic notions of Pell conics and hyperstructures theory that these topics can be found in the books [2,36,37]. Moreover, we fix here the notations that are used in this paper.

2.1. Conics

According to [36] a conic is a plane affine curve of degree 2. Irreducible conics C come in three types: we say that C is a hyperbola, a parabola, or an ellipse according as the number of points at infinity on (the projective closure of) C equals , or 0. Over an algebraically closed field, every irreducible conic is a hyperbola. Let d be a square free integer nonequal to 1 and put

The conic associated to the principal quadratic form of discriminant ,

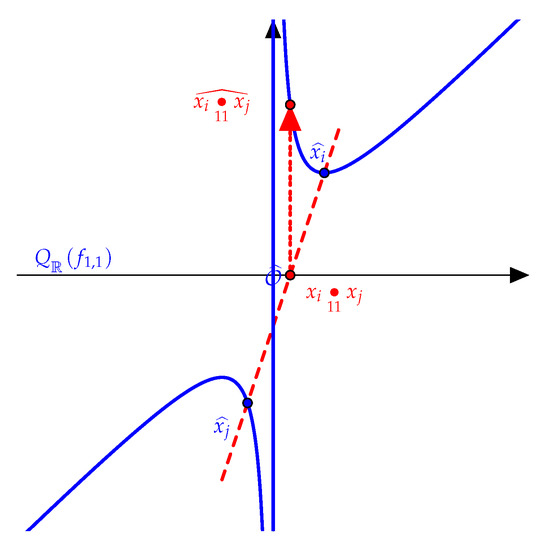

is called the Pell conic of discriminant. Pell conics are irreducible nonsingular affine curves with a distinguished integral point N = (1, 0). The problem corresponding to the determination of E(Q) is finding the integral points on a Pell conic. The idea that certain sets of points on curves can be given a group structure is relatively modern. For elliptic curves, the group structure became well known only in the 1920s; implicitly it can be found in the work of Clebsch, and Juel, in a rarely cited article, wrote down the group law for elliptic curves defined over and at the end of the 19th century. The group law on Pell conics defined over a field F. For two rational points , draw the line through parallel to line , and denote its second point of intersection with which is the sum of two where is an arbitrary point in pell conic perchance in infinity, is identity element of group. In the Figure 1 the operation is picturised on the conic section .

Figure 1.

Conic section .

Example 1.

Consider over finite field . Then we have a Caley table of points (Table 1):

Table 1.

Conic group .

The associativity of the group law is induced from a special case of Pascal’s Theorem. In the following, we recall Pascal’s Theorem which is a very special case of Bezout’s Theorem.

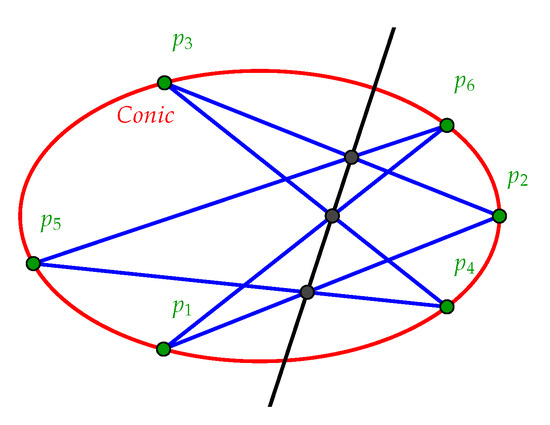

Theorem 1

([38] Pascal’s Theorem). For any conic and any six points on it, the opposite sides of the resulting hexagram, extended if necessary, intersect at points lying on some straight line. More specifically, let denote the line through the points p and q. Then the points , and lie on a straight line, called the Pascal line of the hexagon Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pascal line of the hexagon.

2.2. Krasner’s Hyperrings and Hyperfields

Let H be a non-empty set and denotes the set of all non-empty subsets of H. Any function · from the cartesian product into is called a hyperoperation on H. The image of the pair under the hyperoperation · in is denoted by . The hyperoperation can be extended in a natural way to subsets of H as follows: for non-empty subsets of H, define . The notation is applied for and also for . Generally, we mean (k times), for all and also the singleton is identified with its element a. The hyperstructure is called a semihypergroup if for all , which means that

A semihypergroup is called a hypergroup if the reproduction law holds: , for all .

Definition 1

([2]).Let be a hypergroup and K be a non-empty subset of H. We say that is a subhypergroup of H and it denotes if for all we have .

Let be a hypergroup, an element (resp. ) of H is called a right identity (resp. left identity ) if for all , (resp. ). An element e is called an identity if, for all , A right identity (resp. left identity ) of H is called a scalar right identity (resp. scalar left identity) if for all , (). An element e is called a scalar identity if for all , An element is called a right inverse (resp. left inverse) of a in H if , for some right identities in H (). An element is called an inverse of if for some identities in We denote the set of all right inverses, left inverses and inverses of by and respectively.

Definition 2

([2]).A hypergroup is called reversible, if the following conditions hold:

- (i)

- At least H has one identity e;

- (ii)

- every element x of H has one inverse, that is ;

- (iii)

- implies that and , where and .

Definition 3

([2,23]).A hypergroup is called canonical, if the following conditions hold:

- (i)

- for every

- (ii)

- for every

- (iii)

- there exists such that for every ,

- (iv)

- for every there exists a unique element such that ; (we shall write for and we call it the opposite of x.)

- (v)

- implies and ;

Definition 4

([2]).Suppose that and are two hypergroups. A function is called a homomorphism if for all x and y in H. We say that f is a good homomorphism if for all x and y in H, .

The more general hyperstructure that satisfies the ring-like conditions is the hyperring. The notion of the hyperring and hyperfield was introduced in Algebra by M. Krasner in 1956 [21]. According to the current terminology, these initial hypercompositional structures are additive hyperrings and hyperfields whose additive part is a canonical hypergroup. Nowadays such hypercompositional structures are called Krasner’s hyperrings and hyperfields.

Definition 5

([20]).A Krasner’s hyperring is an algebraic structure which satisfies the following axioms:

- (1)

- is a canonical hypergroup,

- (2)

- is a semigroup having zero as a bilaterally absorbing element, i.e., .

- (3)

- The multiplication is distributive with respect to the hyperoperation +.

A Krasner’s hyperring is called commutative if the multiplicative semigroup is a commutative monoid. A Krasner’s hyperring is called a Krasner’s hyperfield, if is a commutative group. In [20] Krasner presented a class of hyperrings which is constructed from rings. He proved that if R is a ring and G is a normal subgroup of s multiplicative semigroup, then the multiplicative classes , form a partition of R. He also proved that the product of two such classes, as subsets of R, is a class G as well, while their sum is a union of such classes. Next, he proved that the set of these classes becomes a hyperring, when:

- (i)

- and

- (ii)

Moreover, he observed that if R is a field, then is a hyperfield. Krasner named these hypercompositional structures quotient hyperring and quotient hyperfield, respectively. At the same time, he raised the question if there exist non-quotient hyperrings and hyperfields [20]. Massouros in [27] generalized Krasner’s construction using not normal multiplicative subgroups, and proved the existence of non-quotient hyperrings and hyperfields. Since the paper deals only with Krasner’s hyperfields we will write simply quotient hyperfields instead of Krasner’s quotient hyperfields.

3. Hyperconic

The notion of hyperconics on a quotient hyperfield will be studied in this section. By the use of hyperconic we present some hyperoperations as a generalization group operations on fields. We investigate some attributes of the associated hypergroups from the hyperconics and the associated -groups on the hyperconics.

Let and be the quadratic equation of two variables in field of F. If and equation still stay in quadratic and two variables or the other word and , then it can be calculated as an explicit function y in terms of x, also with a change of variables, can be expressed in the form of or where

For this purpose if set and then where If set and then where If set and that

then where and . Reduced quadratic equation of two variables in field of F can be generalized in quotient hyperfield .

Definition 6.

Let be the quotient hyperfield and and be equal to or . Then the relation , is called generalized reduced two variable quadratic equation in Moreover the set is called conic hypersection, and if , is named non-degenerate conic hypersection. For all and , is conic section and for is non-degenerate conic section, in which or corresponding to . It is also said to conic hypersection, as a subset of and where for all

Theorem 2.

Using the above notions we have

Proof.

Let and without losing of generality . Then

Consequently, □

Example 2.

Let be the field of order 5, and . Then we have where

and In this case is a non-degenerate conic hypersection because .

Definition 7.

Let F be a field, and G be a subgroup in We take

Obviously, is an element outside of F. We denote by where , and . Suppose that , , , for all , also where and . Moreover, , and , for all x in field of .

Remark 1.

It should be noted that associativity by adding to field of for two operations of "+" and "·" remains preserved.

Definition 8.

Let be a non-degenerate conic hypersection, and

where For all

and

and is meant by formal derivative .

We denote by and by also take and, . Moreover, and also, for all in hyperfield of , and agree to if In addition say to the line passing from Intuitively each line passing from is called vertical line, and every vertical line pass through . is playing an asymptotic extension role for function

Remark 2.

By adding to hyperfield of associativity for two hyperoperations of "⊕" and "⊙" remains preserved.

Suppose that and Hence, we the following proposition

Proposition 1.

if then .

Proof.

Let , and . Then

Hence , as we expected. □

Definition 9.

Let be a non-degenerate conic hypersection then it is named hyperconic and denoted to if the following implication for all and holds:

Proposition 2.

Let and belong to , then

Proof.

The proof is straightforward for the first two cases. If then

Suppose that by regarding Definition 8 if then

if then proof is similar to previous manner, ultimately if then

□

Remark 3.

is a conic group, for all . Notice that is the group operation on the conic

Example 3.

Let the field of order 5, and . Then we have , where and , and , in this case is a hyperconic because .

Definition 10.

We introduce hyperoperation “∘” on as follows:

Let . If and for some and .

Theorem 3.

is a hypergroup.

Proof.

Suppose that , by Bezout’s Theorem Now let , where . If and then and Because and we have thus

and that is , consequently "∘" is well defined. If or or associativity is evident. If this property is not met, the following cases may occur:

Case 1. If . In this case we have .

Similarly

On the other hand we have

Therefore by Pascal’s Theorem we have

and in addition

On the other word

So

Case 2. If . (i) If . We have

Otherwise

(ii) If . This case similar to (i).

(iii) If . We have

On the other hand

Case 3. If . In this case we have

On the other hand

To prove the validity of reproduction axiom for ”∘” let us consider two cases:

Case 1. If then and where also is a conic group, hence there is nothing to prove.

Case 2. If consider arbitrary element then

Similarly, and reproduction axiom is established. Thus, is a hypergroup. □

Remark 4.

The hyperconic and the associated hypergroup are conic and conic group, respectively, if .

Example 4.

Let be the field of order 5 and . We have In addition, if we go back to Example 3 then is hyperconic, where

, Now let and Then H and K are reversible subhypergroups of , which are defined by the Caley Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Cayle table .

Table 3.

Caley table .

Proposition 3.

H is subhypergroup of if and only if or , for some .

Proof.

. Let us assume that for every in . Then in exist such that . Now let , thus we have . Accordingly, .

. It is obvious. □

Proposition 4.

Let H be a subhypergroup of . Then H is reversible hypergroup if and only if , for some .

Proof.

. First we prove that is a regular reversible hypergroup for all . Let and are elements in .

Case 1. If , then

Case 2. If , then and , where then and .

Case 3. If , then and . Notice that , for all (i.e., every element is one of its inverses).

. Assume that and , in which , and . Then , where . Hence and this means reversibility conditions do not hold. □

The class of - groups is more general than the class of hypergroups which is introduced by Th. Vougiouklis [39]. The hyperstructure is called an group if and also the weak associativity condition holds, that is for all . In [13,14] the authors have investigated some hyperoperations denoted by and ⋄ on some main classes of curves; elliptic curves and homographics over Krasner’s hyperfields. In the following, we study them on hyperconic. Consider the following hyperoperation on the hyperconic; :

for all , in

Proposition 5.

is an -group.

Proof.

The proof is straightforward. □

Proposition 6.

If , , then is an epimorphism of -groups.

Proof.

The base of the proof is similar to the proof of Proposition 3 in [14]. □

Example 5.

Let be a subgroup of , where Consider on . Consequently is a hyperconic, a calculation gives us the Table 4 of -group.

Table 4.

Conic -group, .

Let A be a finite set called alphabet and let K be a non-empty subset of called key-set and also let “·” be a hyperoperation on In [40] Berardi et.al. utilized the hyperoperations with the following condition for all and Let the subhypergroup of and where Notice that is the set of all inverses of for all . We define the hyperoperation ⋄ on A as bellow:

Theorem 4.

is a canonical hypergroup which satisfies Berardi’s condition.

Proof.

The proof is similar to the one of Theorem 4.1 in [13]. □

4. Conclusions

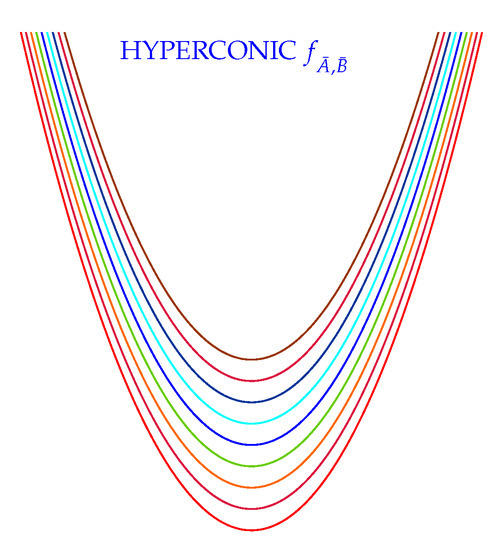

Conic curve cryptography (CCC) is rendering efficient digital signature schemes (CCDLP). They have a high level of security with small keys size. Let and be the quadratic equation of two variables in field of F, if and then the equation is called homographic transformation. In [14] Vahedi et. al extended this particular quadratic equation on the quotient hyperfield Now suppose that and in . Then the curve is called a conic. The motivation of this paper goes in the same direction of [14]. In fact, by a similar way the notion of conic on a field extended to hyperconic over a quotient hyperfield hyperfield, as picturized in Figure 3. Notice that as one can see the group structures of these two classes of curves have different applications, the associated hyperstructures can be different in applications. In the last part of the paper a canonical hypergroup which is assigned by is investigated.

Figure 3.

Hyperconic, .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, all authors worked on equally; project administration and funding acquisition, S.H.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Sarka Hoskova-Mayerova was supported within the project for development of basic and applied research developed in the long term by the departments of theoretical and applied bases FMT (Project code: DZRO K-217) supported by the Ministry of Defence in the Czech Republic.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Marty, F. Sur Une Generalization de Group. In Proceedings of the 8th Congres Des Mathematiciens Scandinaves, Stockholm, Sweden, 14–18 August 1934; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, P. Prolegomena of Hypergroup Theory; Aviani Editore: Tricesimo, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Davvaz, B.; Leoreanu-Fotea, V. Hyperring Theory and Applications; International Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, P.; Leoreanu-Fotea, V. Applications of Hyperstructure Theory; Kluwer Academical Publications: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vougiouklis, T. Hyperstructures and Their Representations; Hadronic Press: Palm Harbor, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskova, S.; Chvalina, J. A survey of investigations of the Brno research group in the hyperstructure theory since the last AHA Congress. In Proceedings of the AHA 2008: 10th International Congress-Algebraic Hyperstructures and Applications, University of Defence, Brno, Czech Republic, 3–9 September 2008; pp. 71–83, ISBN 78-80-7231-688-5. [Google Scholar]

- Antampoufis, N.; Hoskova-Mayerova, S. A Brief Survey on the two Different Approaches of Fundamental Equivalence Relations on Hyperstructures. Ratio Math. 2017, 33, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A.; Consani, C. From monoids to hyperstructures: In search of an absolute arithmetic. In Casimir Force, Casimir Operators and the Riemann Hypothesis: Mathematics for Innovation in Industry and Science; van Dijk, G., Wakayama, M., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 147–198. [Google Scholar]

- Connes, A.; Consani, C. The hyperring of adele classes. J. Number Theory 2011, 131, 159–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A.; Consani, C. The universal thickening of the field of real numbers. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Conference of the Canadian Number Theory Association, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 16–20 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Viro, O. On basic concepts of tropical geometry. Proc. Steklov Inst. Math. 2011, 273, 252–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladki, P.; Marshall, M. Orderings and signatures of higher level on multirings and hyperfields. J.-Theory-Theory Appl. Algebr. Geom. Topol. 2012, 10, 489–518. [Google Scholar]

- Vahedi, V.; Jafarpour, M.; Aghabozorgi, H.; Cristea, I. Extension of elliptic curves on Krasner hyperfields. Comm. Algebra 2019, 47, 4806–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, V.; Jafarpour, M.; Cristea, I. Hyperhomographies on Krasner Hyperfields. Symmetry Class. Fuzzy Algebr. Hypercompos. Struct. 2019, 11, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freni, D. Strongly Transitive Geometric Spaces: Applications to Hypergroups and Semigroups Theory. Comm. Algebra 2004, 32, 969–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhakian, Z.; Knebusch, M.; Rowen, L. Layered tropical mathematics. J. Algebra 2014, 416, 200–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhakian, Z.; Rowen, L. Supertropical algebra. Adv. Math. 2010, 225, 2222–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorscheid, O. The geometry of blueprints: Part i: Algebraic background and scheme theory. Adv. Math. 2012, 229, 1804–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorscheid, O. Scheme theoretic tropicalization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.07949. [Google Scholar]

- Krasner, M. A class of hyperrings and hyperfields. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 1983, 6, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, M. Approximation des corps value complets de caracteristique p10 par ceux de caracteristique 0. In Colloque d Algebre Superieure, Tenu a Bruxelles du 19 au 22 Decembre 1956; Centre Belge de Recherches Mathematiques Etablissements Ceuterick: Louvain, Belgium; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1957; pp. 129–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ameri, R.; Eyvazi, M.; Hoskova-Mayerova, S. Superring of Polynomials over a Hyperring. Mathematics 2019, 7, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittas, J.D. Hypergroupes canoniques. Math. Balk. 1972, 2, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Massouros, C.G. A field theory problem relating to questions in hyperfield theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics, Halkidiki, Greece, 19–25 September 2011; Volume 1389, pp. 1852–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Dakic, J.; Jancic-Rasovic, S.; Cristea, I. Weak Embeddable Hypernear-Rings. Symmetry 2019, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massouros, C.G.; Massouros, G.G. On Join Hyperrings. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on Algebraic Hyperstructures and Applications, University of Defence, Brno, Czech Republic, 3–9 September 2008; pp. 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Massouros, C.G. On the theory of hyperrings and hyperfields. Algebra Log. 1985, 24, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massouros, G.G.; Massouros, C.G. Homomorphic Relations on Hyperringoids and Join Hyperrings. Ratio Math. 1999, 13, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ameri, R.; Kordi, A.; Sarka-Mayerova, S. Multiplicative hyperring of fractions and coprime hyperideals. An. Stiintifice Univ. Ovidius Constanta Ser. Mat. 2017, 25, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancic-Rasovic, S. About the hyperring of polynomials. Ital. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2007, 21, 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Cristea, I.; Jancic-Rasovic, S. Operations on fuzzy relations: A tool to construct new hyperrings. J. Mult-Val. Logic Soft Comput. 2013, 21, 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Jancic-Rasovic, S.; Dasic, V. Some new classes of (m,n)-hyperrings. Filomat 2012, 26, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, I.; Jancic-Rasovic, S. Composition Hyperrings. An. Stiintifice Univ. Ovidius Constanta Ser. Mat. 2013, 21, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaut, C.; Flaut, D.; Hoskova-Mayerova, S.; Vasile, R. From Old Ciphers to Modern Communications. Adv. Mil. Technol. 2019, 14, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saeid, A.B.; Flaut, C.; Hoskova-Mayerova, S. Some connections between BCK-algebras and n-ary block codes. Soft Comput. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankerson, D.; Menezes, A.; Vanstone, S.A. Guide to Elliptic Curve Cryptography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koblitz, N. Introduction to elliptic curves and modular forms. In Volume 97 of Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, J.H.; Tate, I.T. Rational Points on Elliptic Curves; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- Vougiouklis, T. The fundamental relation in hyperrings, The general hyperfield. In Proceedings of the 4th International Congress on AHA, Xanthi, Greece, 27–30 June 1990; World Scientific: Singapore, 1991; pp. 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, L.; Eugeni, F.; Innamorati, S. Remarks on Hypergroupoids and Cryptography. J. Combin. Inform. Syst Sci. 1992, 17, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).