Abstract

Using an exhaustive computer search, we prove that the number of inequivalent -arcs in PG is exactly 22. This generalizes a result of Barlotti (see Barlotti, A. Some Topics in Finite Geometrical Structures, 1965), who constructed the first such arc from a conic. Our classification result is based on the fact that arcs and linear codes are related, which enables us to apply an algorithm for classifying the associated linear codes instead. Related to this result, several infinite families of arcs and multiple blocking sets are constructed. Lastly, the relationship between these arcs and the Barlotti arc is explored using a construction that we call transitioning.

MSC:

94B27; 94B05; 51E20; 05B25

1. Introduction

Let be the finite field with q elements, q a prime power. We denote by the projective plane over . Two subsets and in are projectively equivalent (denoted by ) if there exists a projectivity such that . An -arcK in is an n-set in such that each line contains at most r points of K and some lines contain exactly r points of K. An -arc in is simply called an n-arc. A fundamental problem of -arcs in is the following.

Problem.

Let r be an integer with .

- (1)

- Find , the maximum value of n for which an -arc exists in .

- (2)

- Classify -arcs in for up to projective equivalence.

In the cases , the values of are known as given in Table 1, see [1,2]. It is also known that every -arc is projectively equivalent to a conic when q is odd, and that every -arc is projectively equivalent to a conic plus a point (called the nucleus) when or 8 [3]. Marcugini et al. [4,5] proved with the aid of a computer that -arcs in are unique, and Hill and Love [6] showed that there are three -arcs in up to projective equivalence, see Table 2 (see also [7,8] for ). In unpublished work, the authors of [7] have classified the -arcs in .

Table 1.

The known values and bounds on , .

Table 2.

The number of inequivalent -arcs.

For 5-arcs in , it has been known that the maximal size is [9,10], but it was not known how many inequivalent arcs of maximal size exist. In [11], the second author presented 13 inequivalent -arcs in . Subsequently, Professor M. Grassl, attending the same conference, found in total 22 inequivalent linear codes corresponding to -arcs with the help of the computer algebra system Magma [12]. Those results have been presented in [13]. Finally, using the package Q-Extension developed by the first author [14] (see Section 2), the following extended result has been confirmed.

Theorem 1.

There are exactly 22 inequivalent -arcs in as listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

The -arcs in .

In Section 2, we explain the algorithms in the package Q-Extension, which is used for classification of linear codes with many different parameters over different fields including codes with given restrictions (self-orthogonal, self-complementary, etc.). Many published results are based on calculations with Q-Extension and most of them are verified with other software, programs and theoretical proofs (for example [16]).

An code is a linear code over of length n and dimension k. is called an code if it has minimum weight d. A matrix over whose rows form a basis of is called a generator matrix of . A code is projective if any two columns of G are linearly independent. Consequently, G has no all-zero column if is projective. Two q-ary codes are equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by a sequence of the following transformations: (1) a permutation of the coordinate positions of all codewords; (2) a multiplication of a coordinate of all codewords with a nonzero element of ; (3) a field automorphism. The set of all automorphisms of forms the automorphism group of , denoted by . Two codes are monomially equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by a sequence of the transformations (1) and (2). The equivalent codes over a prime field are monomially equivalent. For , let be a generator matrix of a projective code and let be the n-set in corresponding to the n columns of . Then and are monomially equivalent if and only if .

For a projective code with a generator matrix G, the n columns of G can be considered as an -arc in and vice versa. For more details about the equivalence between sets in projective spaces over a finite field and linear codes, see Chapter 16 in [17].

An -blocking set B in is an f-set such that each line contains at least m points of B and some lines contain exactly m points of B. If and , then the complement of an -arc K in PG is an -blocking set. Thus, -arcs and -blocking sets are equivalent objects.

Lemma 1

([17,18]). Let be a projective code with a generator matrix G and let K be the n-set in PG given by the n columns of G. Then, has minimum weight d if and only if K is an -arc (equivalently, is a -blocking set) in .

For an code, we have , which is called the Griesmer bound. A linear code attaining the Griesmer bound is called a Griesmer code. Since Griesmer codes with are projective [18], the -arcs in PG and the codes are equivalent objects. For a set K in , a line is called an i-line if it meets K in exactly i points. We denote (or simply when no confusion arises) the number of i-lines of K. The list is called the spectrum of K. Let be the automorphism group of K, that is, the set of projectivities in with . The spectra, together with the order of the automorphism group for the 22 projectively inequivalent -arcs in are given in Table 3.

In Section 3, we construct the arcs in Table 3 without computer. We show how to construct these arcs from the well-known arc found by Barlotti [10] by exchanging some points, an operation called transition. From the geometrical point of view, we show how to distinguish and (also and ), which can not be distinguished from their spectra and automorphism group orders.

In Section 4, we generalize some of the -arcs given in Section 3 to -arcs (equivalently, -blocking sets) in .

Remark 1.

We have also confirmed that there are exactly 194 inequivalent -arcs in by exhaustive search using the package Q-Extension as in Table 2. For the 194 inequivalent -arcs in , see http://mars39.lomo.jp/opu/36_3_30.txt.

Remark 2.

A similar interesting problem in the real projective plane is so called the real configuration problem. A configuration of lines and points is called an configuration if it consists of n lines and n points, each of which is incident to exactly k of the other type. It is called geometric if these are points and lines in the real projective plane. Especially, the problem concerning the existence of geometric configurations remains open only for the case , see [19].

2. Algorithms in the Package Q-Extension

We have proved that there are exactly 22 inequivalent -arcs (and also 194 inequivalent -arcs) in PG by exhaustive computer search using the package Q-Extension [14]. It is available on the web page http://www.moi.math.bas.bg/~iliya/Q_ext.htm of the first author for fields with elements (for larger fields write to Iliya Bouyukliev). In this section we briefly describe the algorithms in the package. We present the explanation in terms of linear codes because Q-Extension is a software for construction and investigations of linear codes. We discuss the background and give the main ideas.

Each linear code is completely determined by its generator matrix. The main problem we solve is how to construct generator matrices of all inequivalent linear codes with length n, dimension k, and minimum distance d over the field , where p is a prime. If we know a part of the generator matrix, the problem will be much easier. This previously given part (submatrix) can be a generator matrix of a residual code or the identity matrix of size k, since any code has a generator matrix in systematic form.

Let G be a generator matrix of an code . Then the residual code of with respect to a codeword c is the code generated by the restriction of G to the columns where c has zero entries.

Lemma 2

([21]). Let be an code over and let be a codeword of weight . Then is an code with .

Let be an code with generator matrix G and let be a matrix with rows such that . The main idea of our approach is to construct all inequivalent codes with given parameters on the current step and to use these codes (their generator matrices) in the next step of the extension.

Let be the set consisting of the codes generated by a matrix in the form

where O is the zero matrix, and is such a vector that the first row of G has weight . We can assume that and . The codes from form the root of our search tree. We define to be the set of all codes which have a generator matrix of the form

such that the first s rows of generate an code whose minimum weight is at least d.

We use the equivalence of codes in terms of group action on a proper set. We consider the action of the group of all monomial matrices of size n on the set of linear codes with length n over the field . This action induces an equivalence relation in as two codes are equivalent if and only if they belong to the same orbit. Hence the equivalence classes for the defined relation are the orbits with respect to this action. The set of matrices such that form the automorphism group of the linear code .

The nodes in our search tree are objects from the search space . From a linear code corresponding to the node , we obtain linear codes from which are children of the code A. We denote the set of inequivalent children by . The elements of correspond to the nodes of the next level which are connected to by edges. To find only the inequivalent children in , , we use a special type of equivalence which we call equivalence up to extension. This type of equivalence is defined considering the action of the subgroup of consisting of the monomial matrices of block-diagonal form with two blocks of sizes and m, respectively. Obviously, such a matrix acts on the first coordinates and the last m coordinates of the given linear code separately.

It is easy to see that two equivalent codes up to extension have equivalent children. Practically, the rule , which connects all children to a code, defines our search tree. The execution of the algorithm can be considered as traversing the search tree and visiting all nodes through the edges. This can be done by a depth first search.

We use the algorithm only in the case when the search tree is not so big. That is why our isomorph rejection approach is very natural, and it is known as isomorph rejection with recorded objects [22]. The basic idea of this technique is to keep a global record R of the objects seen so far during traversal of a search tree. Whenever an object is constructed, it is checked for equivalence against the recorded objects in R. If is equivalent to an object in R, then the subtree rooted at is pruned. This approach is fast enough for us because of concepts of canonical form. The use of canonical form reduces the problem of equivalence test of codes to comparison of codes (for more details see [22]).

We obtain the automorphism group and a canonical form of a given code using a modification of the algorithm presented in [23]. This algorithm gives the order of the group, a set of generating elements, and a canonical permutation. One of the advantages of the algorithm is the effective construction of child codes. We give an example.

Example 1.

Let us try to construct all codes taking their generator matrices in a systematic form:

Any row in the unknown matrix X must have at least eight nonzero coordinates. For a row a in X, consider the triple , where is the number of coordinates in a equal to i, . We are looking for all triples with and . The number of nonnegative triples which satisfy these constrains is 30. They form the set of possible solutions.

Without loss of generality we can take the first row of X to be , or . This means that the root consists of three codes with generator matrices

Consider in detail the first node. We can divide the matrix X into two parts, where and have 2 and 8 columns respectively. Using the possible solutions from , the algorithm finds by exhaustive search all possible solutions for the next rows as tuples of triples such that , , where is the second or third row of X. The constrains for are

We denote by the set of all possible solutions in this step. Furthermore, the code generated by the vectors and must have minimum distance at least 9 which reduces the possibilities and the algorithm obtains

This gives us the information that the first two coordinates of b are not zeros, but two of the other 8 coordinates are zeros, three of them are 1 and three are equal to 2. It turns out that, up to a permutation, the second row of X must be , or . The codes which correspond to these solutions have generator matrices

Obviously, these three codes are equivalent, therefore there is only one node in the second level of the tree connected with the considered root node.

Now we divide the matrix X into four parts (cells), where , and have 2, 3 and 3 columns respectively. One possible solution for the matrix G is

This solution turns out to be unique up to equivalence. The solution for the third row comes from . The algorithm also provides that the code must be projective. It is easy to prove that the matrix G in systematic form cannot have rows with weights 9 and 10 (the algorithm proves this by exhaustive search).

The same code can be constructed using as a prescribed part its residual code with respect to a codeword of weight 9. The residual code has parameters . There is a unique ternary code with these parameters, so we are looking for a generator matrix of in the form

The algorithm in this case works in a similar way and it is even more effective, but it is a little bit more complicated to explain.

Consider now the construction of the codes. If is a code with these parameters, then its residual code with respect to a codeword of weight 24 is a code. It is easy to prove (even by hand) that the code with a generator matrix is, up to equivalence, the only code. Therefore we are looking for a generator matrix of of the form

The program finds all inequivalent solutions in about 23 hours on a computer with Intel Xeon E5-2640 processor. The constructed tree consists of 8 nodes on the second level and 22 nodes on the third level. In this case the tree is not big, but finding solutions for the last level is computationally expensive. Since this search is exhaustive, we can conclude that there are exactly 22 codes up to equivalence, which proves Theorem 1.

Remark 4.

Many problems for classification of combinatorial objects are solved using computer programs. But there are only a few more general software packages for such classification, for example “Split” by David Jaffe [24] and “Orbiter” by Anton Betten [25]. Q-Extension is convenient for our purposes, we have experience with it and therefore we use exactly this package in our classification.

3. Construction of -Arcs in

We start with the conic

A line ℓ in is called external, tangent or secant to C if , 1 or 2, respectively. For odd q, a point in is called internal or external if the number of tangent lines on P is 0 or 2, respectively. Let (resp. ) be the set of all internal (resp. external) points of C. Then, , , see ([3] Chapter 8). The following construction of a -arc in is due to [10].

Theorem 2.

For q odd, let . Then

- (1)

- K forms a -arc in with spectrum

- (2)

- and .

Proof.

The tangents, the secants and the external lines of C are 1-lines, -lines and -lines for the arc K, respectively. Recall that [3]. Since any automorphism of K satisfies , maps any tangent line of C to a tangent line. Then, and . Hence, we get the assertion. □

Let be the above arc K for . We denote the line by or . There is another simple construction of a -arc in .

Lemma 3

(Example 2.3 in [15]). Let be the set of points on the lines , , , together with the points , . Then, the complement of forms a -arc if q is even and a -arc if q is odd.

The arc given below is such an arc obtained by the above lemma for . We give another construction for later. See Section 4 for the spectra of the arcs in Lemma 3.

In the following, we show how to construct the arcs in Table 3 from . For two -arcs and , we define the distance between them as

We also define the transition number of as

Then, one can obtain some arc from by exchanging or points, denoted by , that is, for some disjoint t-sets and with or , see Table 4. In what follows, we discuss how to find the set D to be deleted from the arc and the set A to be added to get in Table 4. Here by we denote the point in . For two points P and Q, denotes the line through P and Q. Table 4 follows from the following lemmas.

Table 4.

Transition , together with the values and .

Lemma 4.

and .

Proof.

Since every external point Q of the conic C is on the three 5-lines (the secants through Q), we have . We construct from by three point exchanges, which implies . Note that the tangents of C are the 1-lines for . Take three points on the conic C. Since is 3-transitive, we may assume that , , . Let be the tangent of C at for , i.e., , , , and let for . For , the line is a secant meeting C in and say. Then, , , , , , , , , . Taking and , one obtains the transition . Actually, the tangents at are the 0-lines and the tangents at and are the 1-lines for , where . □

We confirmed that (and similar for the other values of in Table 3 by computer. In what follows, let , , , , , , , be as in the proof of Lemma 4 and let be the tangent at to C for and for . Then, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , . Note that are the secants through . Let apart from , , . For any point R and for a given arc , we state that R is of type if there exist -lines and -lines and so on through R for .

Lemma 5.

and .

Proof.

Let for . Then, , , . Taking and , one can get the transition . The tangents at are 3-lines for , while the other five tangents remain 1-lines. The three external lines () to C form the 2-lines for . Now, take . Then the possible types of R are: , , , , , , . So, . Now, by the transition , we get by exchanging three points. Hence, we determine . □

For a point , the possible types of R are: , , , , , , . Since every point out of is on at least two 5-lines, we get . By exhaustive computer search, we get the following.

Lemma 6.

for .

Lemma 7.

and .

Proof.

Let , and . Then, , , . Taking and , one can get the transition . Since the two tangents and contain the points and , respectively, the two tangents at , are 1-lines for , while the tangent at remains a 0-line. The two 1-lines for remain 1-lines for . Now, the transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 8.

and .

Proof.

Take . Setting and , we get the transition . As for the 0-lines , , for , two lines and are also 0-lines for , but is a 1-line for . Two 1-lines and for are a 0-line and a 2-line for , respectively. The other 2-lines for are and . The transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 9.

and .

Proof.

Let , . Then, , . Taking and , one can get the transition . Since the tangent contains , it is a 1-line for , while the tangents and remain 0-lines. The other 1-lines for are the tangents and . The transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 10.

.

Proof.

Take and . Setting and , we get the transition . The tangent is a 0-line for , but a 2-line for , while the tangents and remain 0-lines. The tangents and are 1-lines for , but 0-lines for . □

Lemma 11.

and .

Proof.

Let , , , . Then, , , , . Taking and , one can get the transition . The 0-lines for are also 0-lines for . The tangent remains a 1-line, but the other 1-lines for are 2-lines for . The transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 12.

and .

Proof.

Take , , , . Setting and , we get the transition . The tangents , are 0-lines for and the tangents , are 1-lines for . We note that three of the four 2-lines , , and are concurrent at the point . The transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 13.

and .

Proof.

Take the two points and for the set A to be deleted from . Setting , we get the transition . The 0-lines for are also 0-lines for . The tangents and are 2-lines for and the unique 1-line for is . The transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 14.

, , , , .

Proof.

Take the point and let , and . Then, has spectrum and L is the unique 6-line for . The 1-points of L other than U are , , , , . Then, for and . As can be seen in Table 3, , and have the same spectrum. Nevertheless, one can distinguish them as follows. The 3-lines for are , , , , , . And there are two points on three 3-lines; the point 106 on , , and the point on , , . As for , the 3-lines are , , , , , and there is only one point on three 3-lines; the point on the three lines , , . Meanwhile, the 3-lines for : , , , , , form a 6-arc of lines (no three of which are concurrent). Thus, , and are projectively inequivalent. and can be also distinguished similarly as follows. Let and be the sets of 3-lines for and , respectively. Then, is a 6-arc of lines, but is not, for and . Hence, and are projectively inequivalent. □

Lemma 15.

.

Proof.

Taking and , we get the transition . The tangents , , , , no three of which are concurrent, remain 0-lines. The two 0-points out of the 0-lines are and . It turns out that is projectively equivalent to the arc constructed in Lemma 3. The tangent is the 2-line for , but a 3-line for . □

Lemma 16.

, .

Proof.

Take the points and , where , and let . Then, the arc has spectrum and the unique 6-line for is . The 1-points of other than X are , , , , . Then, and . , , are projectively equivalent to , , , respectively. We can distinguish and as follows. The 2-lines for are , , , , which form a 4-arc of lines. On the other hand, the 2-lines for are , , , , the first three of which are concurrent at the point . □

Lemma 17.

, .

Proof.

Let , and , where . Then, has spectrum and the unique 6-line for is . The 1-points of other than Y are , , , , . Then, and . , , are projectively equivalent to , , , respectively. □

Lemma 18.

and .

Proof.

Take the two points and for the 2-set D to be deleted and take . Then, we get the transition . The 0-line for becomes a 2-line for , while the tangents , , remain 0-lines. The arcs and are projectively inequivalent since their automorphism group orders are different. In addition, we can distinguish and as follows. The 2-lines for are , , , having no common point. On the other hand, the 2-lines for are , , , which are concurrent at the point 010. The transition yields by Lemma 6. □

Lemma 19.

and .

Proof.

Take the points , , , , , . Setting and , we get the transition . The 0-lines , for are 1-lines for , while the remains a 0-line. The 1-lines and for are a 1-line and a 2-line for , respectively. Now, there are only two points out of , namely 122 and 165, which are on at most two 5-lines. The types of 122 and 165 are and , respectively. Hence . Suppose . Then, we have a transition for some points . Since the five lines , , , , are 6-lines for , the points Z and must be on the five lines, which is impossible. Thus, . Now, by the transition , we determine .

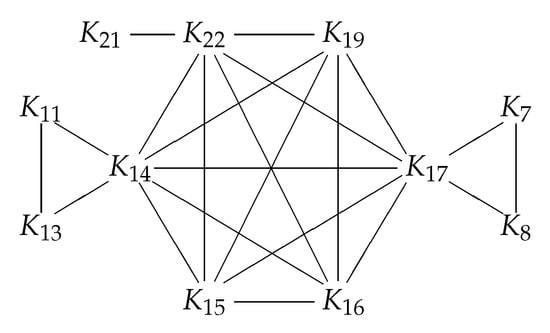

In summary, we have determined the transition numbers of each as in Table 4. Considering the graph with vertex set , where two vertices are joined if , we get Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graph of -arcs with distance 1.

4. Construction of Some Generalized Arcs in

Recall from Lemma 1 that the complement of a -blocking set B is a -arc in . When q is odd, for a -blocking set B is known that if B contains a line [26]. The set for odd q in Lemma 3 is such a -blocking set.

In this section, we generalize some construction results in Section 3 by constructing some -blocking sets in for odd q. Obviously, we have , where is the complement of K in .

Theorem 3.

For odd , let C be a conic in . For any three points , , in C, let be the tangent of C through and be the secant of C through and , and let for . Take any two points P and Q from the three points , , , and let . Then is a -arc with spectrum

for and

for .

Proof.

Let be a conic in and let ℓ be a line. If ℓ contains none of , then ℓ meets at three points. Thus, . If ℓ contains exactly one of , , , say , ℓ meets at two points. Then, ℓ is a secant or a tangent of C. If ℓ is a secant of C, ℓ meets C at and another point. So, . If ℓ is a tangent of C, ℓ is , or , and ℓ contains at least one of the points P and Q. So, . If ℓ contains two of , and , then ℓ is , or . Thus, B is a -blocking set. Without loss of generality, we may take and . Assume . The -lines for B are , , . So, . The 6-lines are the secants through P or Q except and . Hence . For , the above -lines are also 6-lines for B, and . Now, assume . The 5-lines are the secants of C passing through none of , , except the 6-lines. So, . The 4-lines are the external lines of C through P or Q, the secants , , the tangents at and . Hence, . Finally, . □

By some transitions from B in Theorem 3, we get the following.

Theorem 4.

Under the conditions of Theorem 3 with , take , and a point in with . Let and . Then forms a -arc with spectrum

- (1)

- if ℓ is a tangent,

- (2)

- if ℓ is a secant,

- (3)

- if ℓ is an external line.

Proof.

Since ℓ is a tangent of C if and only if , we get the spectrum (1) from Theorem 3 if ℓ is a tangent. As we have already seen in the proof of Theorem 3, the tangent and the secant are 4-lines, the other secants through Q are 6-lines and the external lines through Q are 4-lines for B. Note that , for .

If ℓ is a secant, then for B, the tangent () through is a 4-line, the secant ℓ is a 6-line, the secants , are 3-lines, other secants on are 5-lines and the external lines on are 3-lines. Hence, , , , , .

If ℓ is an external line, then for B, the tangent () through is a 4-line, the secants , are 3-lines, other secants on are 5-lines, the external line ℓ is a 4-line and the external lines on are 3-lines. Hence, , , , . □

We note that the construction of a -blocking set with spectrum (1) or (3) in Theorem 4 is also valid for , but not for the spectrum (2) since ℓ is a secant if and only if when .

For , the -arcs of Theorem 4 (1), (2) and (3) are equivalent to , and , respectively. The next lemma is given in [3, Corollary 7.5].

Lemma 20

([3]). In with , there is a unique conic through a 5-arc.

We can get one more -blocking set in from the set B in Theorem 3 by exchanging two points.

Theorem 5.

Let for an odd prime . Under the conditions of Theorem 3, let C be the conic and take , , , , , and . Let . Then is a -arc, which is not projectively equivalent to any arc in Theorems 3 and 4.

Proof.

Note that if and that , . Since and , the lines and are passing through and , respectively. Let . Then, the 2-lines for are , , and . Hence, adding and to , forms a -blocking set. It can be checked using computer that has spectrum for , for and for . Hence, is not projectively equivalent to any blocking set in Theorems 3 and 4. Assume and suppose contains a conic . Since , it follows from Lemma 20 that could contain at most 4 points from C, 6 points from and the other 4 points, in total at most 14 points from , a contradiction. Thus, contains no conic for . On the other hand, the blocking sets in Theorem 3 and 4 contain a conic. Hence, the arc is not projectively equivalent to any of the arcs in the previous theorems. □

For , the -arc of Theorem 5 is equivalent to .

Remark 5.

(1) Assume in Theorem 5. From Table 2 in Section 1, there exist two inequivalent -arcs (equivalently, -blocking sets) in , see also ([3], Table 12.5). The -arcs have spectrum

- (a)

- or

- (b)

- .

There are four 6-lines , , and for the arc in Theorem 5 when . So, has spectrum (b) and hence is projectively equivalent to the arc in Theorem 4 (3).

(2) When , the line in the proof of Theorem 5 is a secant of C. On the other hand, when , is an external line of C. Thus, depending on the value of q, the line can form a tangent, a secant or an external line of C. That is why we could not determine the spectrum of the -arc in Theorem 5.

Next, we determine the spectrum of the arc in Lemma 3 for odd q to find one more inequivalent arc.

Theorem 6.

For odd , let , consisting of the lines , , , and the points , . Then, forms a -arc with spectrum .

Proof.

Note that no three of the lines are concurrent. Let , , and . Then, and are equal to and , respectively. Hence, is a 4-line. Let ℓ be a line. Then ℓ meets at two, three or four points. When , ℓ is , or . So, ℓ contains or . Thus, is a -arc. Now, the -lines for B are , and . The 5-lines for B are the lines containing one of , but none of . Hence, . The 3-lines for B are the lines through one of two points , containing no other point of , the lines through one point of containing none of , and two more lines . Thus, . Finally, . □

Theorem 7.

Under the conditions of Theorem 6, let . Take and let . Then, is a -arc with spectrum for and for .

Proof.

Since the 3-line for B through is only, forms a -blocking set. The lines through for K except are three 4-lines , , and 5-lines. On the other hand, the lines through for K other than are four 3-lines with , one 5-line and 4-lines. Hence, , , , (or for ). Now, our assertion follows from Theorem 6. □

From the above theorems we get the following.

Corollary 1.

There exist at least six projectively inequivalent -arcs in for with odd prime .

Finally, we consider the case q is even. Assume . Then, it is known that a -blocking set B containing a line satisfies [27]. The set for even q in Lemma 3 is such a -blocking set with spectrum

When , the complement of a -blocking set is a 6-arc (a hyperoval). So, assume . We can construct two more -blocking sets as follows.

Theorem 8.

For even , let C be a conic in with nucleus N. For any three points , , in with , let for . Then,

- (1)

- is a -blocking set with spectrumwith if ,

- (2)

- is a -blocking set with spectrumwith if .

The -blocking sets in Theorem 8 were first found for , see [7].

Corollary 2.

There exist at least three projectively inequivalent -arcs (equivalently, -blocking sets) in for every even .

Remark 6.

From Table 1, -arcs are optimal for and give the known lower bound on for .

Author Contributions

Writing–original draft, I.B., E.J.C., T.M. and T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author was partially supported by the Bulgarian Science Fund under Contract DN-02-2/13.12.2016. The second author was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korean Government(NRF-2018R1D1A1B07044992). The third author was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16K05256.

Acknowledgments

The second author thanks to M. Grassl for his helpful discussion and computer search with Magma in the earlier version of this paper. The authors are very grateful to the reviewers for their comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ball, S. Table of Bounds on Three-Dimensional Linear Codes or (n, r)-Arcs in PG(2, q). Available online: https://mat-web.upc.edu/people/simeon.michael.ball/codebounds.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Ball, S.; Hirschfeld, J.W.P. Bounds on (n, r)-arcs and their application to linear codes. Finite Fields Appl. 2005, 3, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, J.W.P. Projective Geometries over Finite Fields, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marcugini, S.; Milani, A.; Pambianco, F. Classification of the [n, 3, n − 3]q NMDS codes over GF(7), GF(8) and GF(9). Ars Comb. 2001, 61, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Marcugini, S.; Milani, A.; Pambianco, F. Classification of the (n, 3)-arcs in PG(2, 7). J. Geom. 2004, 80, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Love, C.P. On the (22, 4)-arcs in PG(2, 7) and related codes. Discrete Math. 2003, 266, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betten, A.; Cheon, E.J.; Kim, S.J.; Maruta, T. The classification of (42, 6)8-arcs. Adv. Math. Commun. 2011, 5, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, T.; Kikui, A.; Yoshida, Y. On the uniqueness of (48, 6)-arcs in PG(2, 9). Adv. Math. Commun. 2009, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S. On the size of a triple blocking set in PG(2, q). Eur. J. Combin. 1996, 17, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlotti, A. Some Topics in Finite Geometrical Structures; Institute of Statistics Mimeo Series 439; Univ. of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, E.J.; Jung, S.O.; Kim, S.J. On the (29, 5)-arcs in PG(2, 7) and linear codes. In Proceedings of the 2012 KIAS International Conference on Coding Theory and Application, Seoul, Korea, 15–17 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, W.; Cannon, J.J.; Playoust, C. The Magma algebra system I: The user language. J. Symb. Comput. 1997, 24, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, E.J.; Grassl, M.; Jung, S.O.; Kim, S.J. On the (29, 5)-arcs in PG(2, 7). In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Finite Fields and Their Applications, Magdeburg, Germany, 22–26 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyukliev, I.G. What is Q-Extension? Serdica J. Comput. 2007, 1, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R.; Mason, J.R.M. On (k, n)-Arcs and the Falsity of the Lunelli-Sce Conjecture; London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Series 49; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981; pp. 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyukliev, I.; Bouyuklieva, S.; Aaron, T. Gulliver and Patric Östergård, Classification of optimal binary self-orthogonal codes. J. Combin. Math. Combin. Comput. 2006, 59, 33–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bierbrauer, J. Introduction to Coding Theory; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R. Optimal linear codes. In Cryptography and Coding II; Mitchell, C., Ed.; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cuntz, M.J. (224) and (264) configurations of lines. Ars Math. Contemp. 2018, 14, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünbaum, B.; Rigby, J.F. The real configuration (214). J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1990, 41, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodunekov, S. Minimal block length of a linear q-ary code with specified dimension and code distance. Probl. Inform. Transm. 1984, 20, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kaski, P.; Östergård, P.R. Classification Algorithms for Codes and Designs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyukliev, I. About the code equivalence. In Advances in Coding Theory and Cryptology; Shaska, T., Huffman, W.C., Joyner, D., Ustimenko, V., Eds.; Series on Coding Theory and Cryptology; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2007; pp. 126–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, D.B. Optimal binary linear codes of length ≤30. Discrete Math. 2000, 223, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betten, A. Classifying Discrete Objects with Orbiter. ACM Commun. Comput. Algebra 2014, 47, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhuis, A. On multiple nuclei and a conjecture of Lunelli and Sce. Bull. Belg. Math. Soc. 1994, 3, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruen, A.A. Polynomial multiplicities over finite fields and intersection sets. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 1992, 60, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).