Abstract

This paper puts forward an innovative theory and method to calculate the canonical labelings of graphs that are distinct to ’s. It shows the correlation between the canonical labeling of a graph and the canonical labeling of its complement graph. It regularly examines the link between computing the canonical labeling of a graph and the canonical labeling of its k- . It defines and . For each node of a graph G, it designs a characteristic to improve the precision for calculating canonical labeling. Two theorems established here display how to compute the first nodes of . Another theorem presents how to determine the second nodes of . When computing , if already holds the first i nodes , Diffusion and Nearest Node theorems provide skill on how to pick the succeeding node of . Further, it also establishes two theorems to determine the of disconnected graphs. Four algorithms implemented here demonstrate how to compute of a graph. From the results of the software experiment, the accuracy of our algorithms is preliminarily confirmed. Our method can be employed to mine the frequent subgraph. We also conjecture that if there is a node meeting conditions ⩽ for each , then for .

1. Introduction

This paper is the close companion to Reference [1], in which a novel theory and method are presented for calculating the canonical labelings of digraphs. The center subgraph [2] can also be used to determine the first vertex added into of undirected graphs.

This article concentrates on the construction of a universal system and a way of calculating the of undirected graphs [3,4,5], which is also called an [6], a [7] or a canonical form [8] and is the single string corresponding one-to-one to a graph such that two graphs are isomorphic if and only if both have the accurate same canonical labelings. Currently, the calculation of the as the graph isomorphism problem is an unsolved challenge in computational complexity theory such that no polynomial-time algorithm appears for calculating the of an undirected graph. The study of canonical labeling has contributed to the studies of problems in many fields, including quantum chemistry [9], biochemistry [10,11] and so on.

Many exponential algorithms have emerged to deal with the problem. However, different researchers like to define different canonical labeling. Given a graph of n vertices, Kuramochi and Karypis build the canonical labeling by concatenating the columns of the upper-triangular part of its adjacency matrix [12,13]. Huan et al. concatenate the lower triangular elements (including the diagonal elements) of its adjacency matrix to create its canonical labeling [14]. Kashani et al. determine the canonical labeling by concatenating the rows of its adjacency matrix to form an binary number [15,16]. Each of these canonical labelings correspondings one-to-one to a lexicographically smallest graph whose adjacency matrix is seen as a linear string, which is lexicographically smallest. Nevertheless, the computation of the lexicographically least graph is -hard [8,17].

Throughout the paper, the of a graph G is the lexicographically largest string constructed by concatenating the rows of the upper triangular portion of the adjacency matrix associated with G (see Definition 5). The computational complexity that determines the of G is also -hard.

Babai and Luks used a general group-theoretic method to calculate canonical labeling [8]. Nevertheless, combinatorial approaches have operated well in numerous particular situations. For stochastic graphs, Babai et al. generate canonical labeling with high possibility [8,18]. Arvind et al. introduce two similar logspace algorithms for partial 2- and 3-Trees [17,19].

Currently, is the most prevalent and pragmatic means for determining the automorphism group and the of graphs [3,20,21,22]. It appears to have shifted the industry norm for determining the also the automorphism group. For calculating the and automorphism group, and Yan and Han [23] use the depth-first search to traverse the latent intermediary vertices in the search tree. The vertices of the search tree produced by are equitable ordered partitions of vertices in G. iteratively refines partitioning vertices until places the vertices that have the exact equivalent features into an automorphism orbit. As the partition refinement becomes finer and finer, it automatically makes the . Nonetheless, also needs exponential time to calculate the canonical labeling for a given Miyazaki graph [24]. Tener and Deo earned advances for processing the problem [25].

Besides , [4], [5,26] and Conauto [27] are all state-of-the-art tools for graphs isomorphism testing. Based on the individualization of nodes, backtracking and partition refinement, [5,26] is powerful canonical labeling means for dealing with large and sparse graphs. Katebi et al. combine with and show that it is faster for computing the automorphism group of a graph with and then calculating its canonical labeling with than for alone calculating its canonical labeling with [28]. To fix the vulnerability of , uses the policy of breadth-first search to decide the automorphism group and the canonical labeling [4]. also utilizes the fundamental individualization/refinement method and is quite quick for random graphs and several classes of hard graphs.

For the advancement of performance, current algorithms usually employ backtracking and orbit partitioning way to circumvent frequently visiting the same nodes and contrive to decrease the accessed nodes in the search tree. For the canonical labeling issue, McKay et al. present a full examination of the problem [22,23].

governed the area for several decades. Therefore, in-depth research for canonical labeling has been limited to the theoretical skeleton of . This implies that people are only like to support the study trajectory of to extend and build further research.

Since there are several different definitions of canonical labeling, there is no uniform standard such that each researcher works on oneself standard. Besides the lack of a unified standard, the research on the connection between the distinct canonical labeling is also quite lacking. It is a hard task that one wants to confirm the accuracy of canonical labeling achieved by executing an algorithm. Up to now, the criterion by which one can decide which definition is better does not appear.

In this paper, the definition of is completely distinct that of . Unless by chance, the canonical labeling produced by will be not a according to the definition presented by the paper. It is sometimes difficult to confirm the accuracy of the canonical labeling achieved by executing according to the criterion of . Since the insides of many graphs contain a large number of automorphisms, the calculation of canonical labeling becomes extremely arduous in certain situations.

A graph invariant is called complete if the equality of the invariants and implies the isomorphism of the graphs G and H. However, even polynomial-valued invariants such as the chromatic polynomial are not usually complete. A path graph is a graph consisting of exactly its maximal path. For example, the path graph with 4 vertices and the claw graph both have the same chromatic polynomial.

Many algorithms also use the identical definition of as adopted in the paper. However, their main goal is not to consider how to calculate but for other purposes such as mining the frequent subgraphs. Therefore, these algorithms can only run for some limited graph classes. Until now, based on current knowledge and Definition 5 present in this paper, a universal algorithm for calculating the of graphs does not appear.

Jianqiang Hao et al. also provide Propositions 5–6, Lemmas 1–3 and Theorems 10–13 in Reference [2] by which one can compute the proper vertices added into . However, they do not give any proof. In this article, we prove Theorems 3–6 that are one-to-one corresponding to Theorems 10–13 in Reference [2]. We also present the reasons for Lemmas 8–9, which are one-to-one corresponding to Lemmas 2–3 in Reference [2].

In the rest of this paper, Section 2 presents some fundamental vocabulary and preparatory knowledge. Section 3 represents the results followed by some analysis. Section 4 gives our algorithms for calculating the . Section 5 demonstrates the implementation of our algorithms and evaluates our way through many examples. Finally, Section 6 remarks on our conclusions and future work.

2. Preliminaries

This paper only handles limited undirected graphs with neither loops nor multiple edges. A graph consists of a set of nodes and a collection of edges. For a graph , , assume that and represent the set of vertices of G and the collection of edges of G. Any an edge joins two vertices and . For this article to be self-contained, the relevant concepts and definitions are given below.

Definition 1.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. A vertex-induced subdigraph on of G is a subgraph with the vertices set together with any side whose endpoints are both in , expressed by .

Definition 2.

Given two undirected graphs , and , of n vertices. If there is a bijection such that if and only if . We call f an isomorphic projection of . Furthermore, we state that the graph G and H are isomorphic, signified by . An isomorphic map f of G onto itself is declared to be an automorphism of G.

Let , in and , , ⋯ in be two vectors, the issue emerges as to how to determine which one is larger. When comparing two vectors, the following rules must be satisfied.

Definition 3.

Given two vectors , and in N (the collection of natural numbers) satisfying and . Then, the lexicographic order of the two vectors is defined as follows:

- 1.

- , if and for all .

- 2.

- if and only if either of the following is true.

- (a)

- for , .

- (b)

- for and .

Definition 4.

Given two vectors , and satisfying and , where each , denotes a vector in N (the collection of natural numbers). Then, the lexicographic order of the two vectors is defined as follows:

- 1.

- , if and for all .

- 2.

- if and only if either of the following is true.

- (a)

- for , .

- (b)

- for and .

Definition 5.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices with adjacency matrix . To concatenate the rows of the upper triangular part of in the following order , , ⋯, , , , ⋯, , ⋯, , , ⋯, , ⋯, makes a corresponding binary number , which is aof G, signified by (see (1)).

The first row of the upper triangular portion of is the 1 of , signified by . Likewise, the second row of the upper triangular portion is the 2 of , signified by . ⋯. The th row of the upper triangular portion is the of , signified by . It is true that .

A permutation of the nodes of G is an order of the n nodes without repeating. The number of shifts of the nodes of G is . Further, each distinct permutation of the n nodes of determines a single adjacency matrix. Therefore, given a permutation , one can get a corresponding to by Definition 5. The collection of all of G is represented by .

For every , , Suppose that , with , or 1. Given and . By Definition 3, if , then we set . Otherwise, if , then we set . Otherwise, if , then we set .

Definitely, , is a well-ordered set, where ≤ signifies the less-than-or-equal-to binary relationship on the collection stated as above. By the well-ordering theorem, it follows that has a minimum and maximum element, signifies by and and called of G and of G respectively. We also call of G.

The two shifts of the n nodes of G associated with and are the , signifies by and . Furthermore, the two adjacency matrices of G associated with and are the , signifies by and .

corresponding to are of canonical labeling , signified by , , ⋯, , respectively. Conversely, , , ⋯, corresponding to are of canonical labeling , signified by , , ⋯, , respectively.

Based on the above definitions, the following equations are established.

Theorem 1.

Given two undirected graphs , and , of n vertices with adjacency matrices and respectively. Then if and only if = or =.

Lemma 1.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices whose complement graph is , . Then and hold.

Proof.

The adjacency matrices of G and meet the following condition.

where J is an matrix of zeros and ones whose main diagonal entries are 0 and all other entries are 1. By the complement graph and , it can be seen that . Furthermore, by , it follows that for the complement graph of G. □

Theorem 2.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices whose complement graph is , . It follows that

Proof.

By Lemma 1, it holds that . Definitely, the k-bit of is 0 if and only if the k-bit of is 1. Therefore, one can make the of G by executing a complement operation on . Likewise, by Lemma 1, the identity holds. Definitely, the k-bit of is 0 if and only if the k-bit of is 1. Hence, one can make the of by executing a complement operation on .

Since is a constant binary number, one must maximize to minimize . On the opposite, one must minimize to maximize . Likewise, one must maximize to minimize . Contrariwise, one must minimize to maximize . From the above examination, the following results hold.

□

By Theorem 2, it can be seen that if one has computed the , one can simply make . Moreover, the computation means of and are precisely the same.

Theorem 2 shows the mutual relations between and . Because of the existence of the relations, the paper only concentrates on the construction of effective ways to determine . The of G is a graph whose is lexicographically largest.

We signify by the degree of a node u in G, by , the of G, by the degree series of a subset with , and by , the of a subgraph with , and drop the symbol G when no vagueness can occur. We signify by the minimum degree and by the maximum degree of all vertices of a graph G. Throughout this article, suppose . In the following text, when simultaneously involving two graphs, we always assume that their degree sequences are the same except specified.

For each , the quantity of vertices with degree is the of u, signified by . Unless otherwise specified, throughout this article, the degree sequence is decreasing. The distance between any two nodes u and v is the number of edges on the shortest path from u to v.

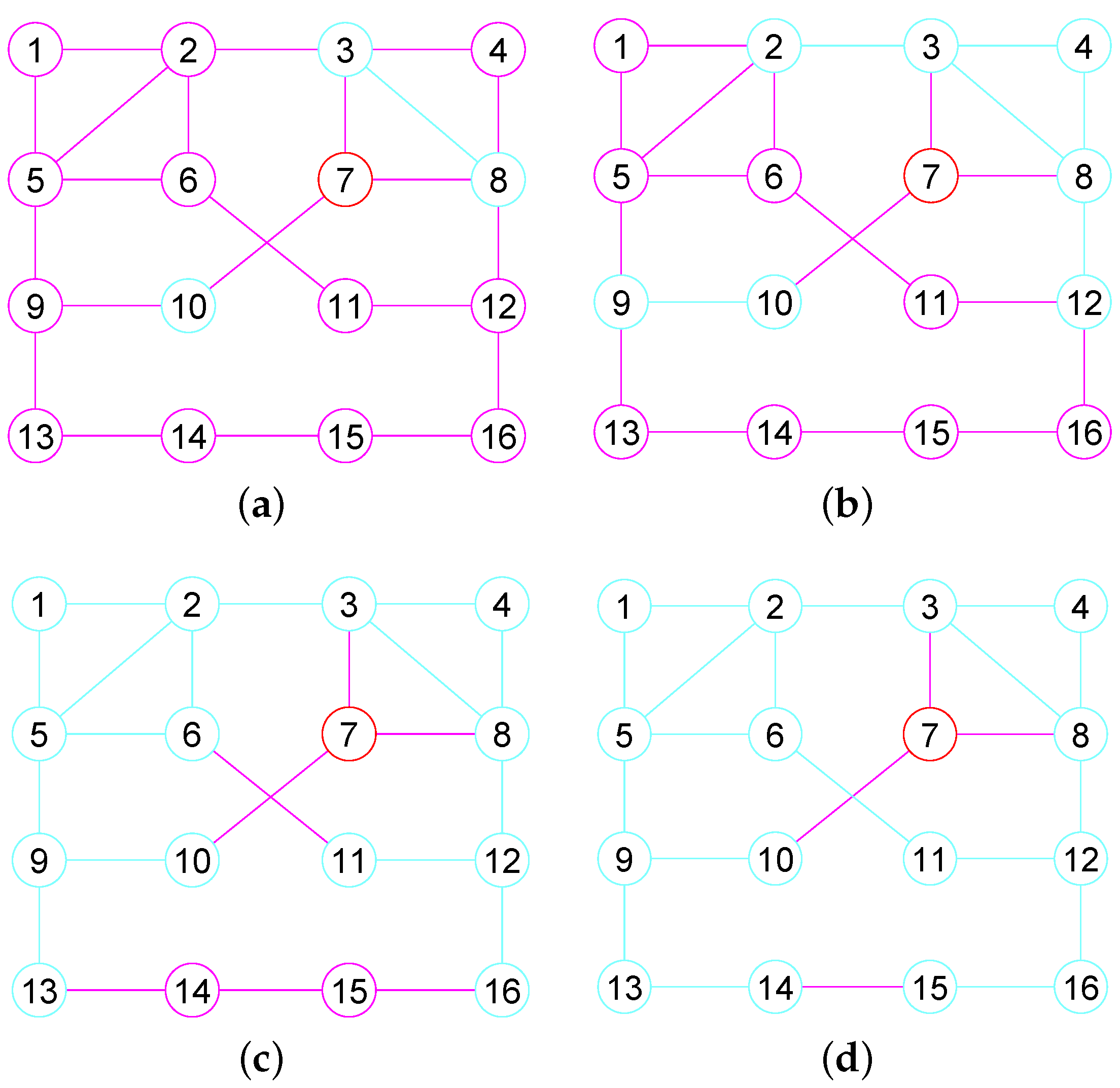

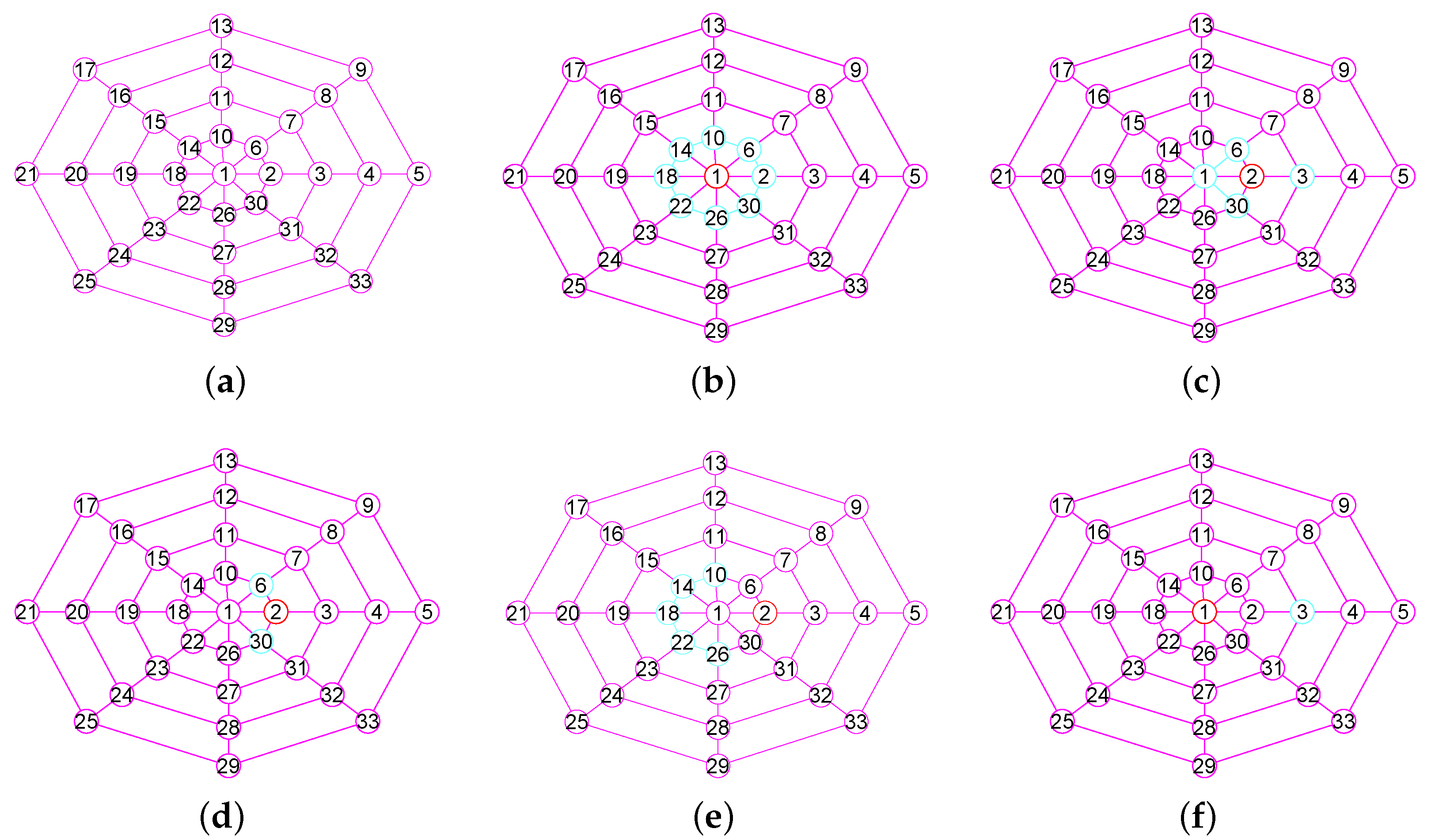

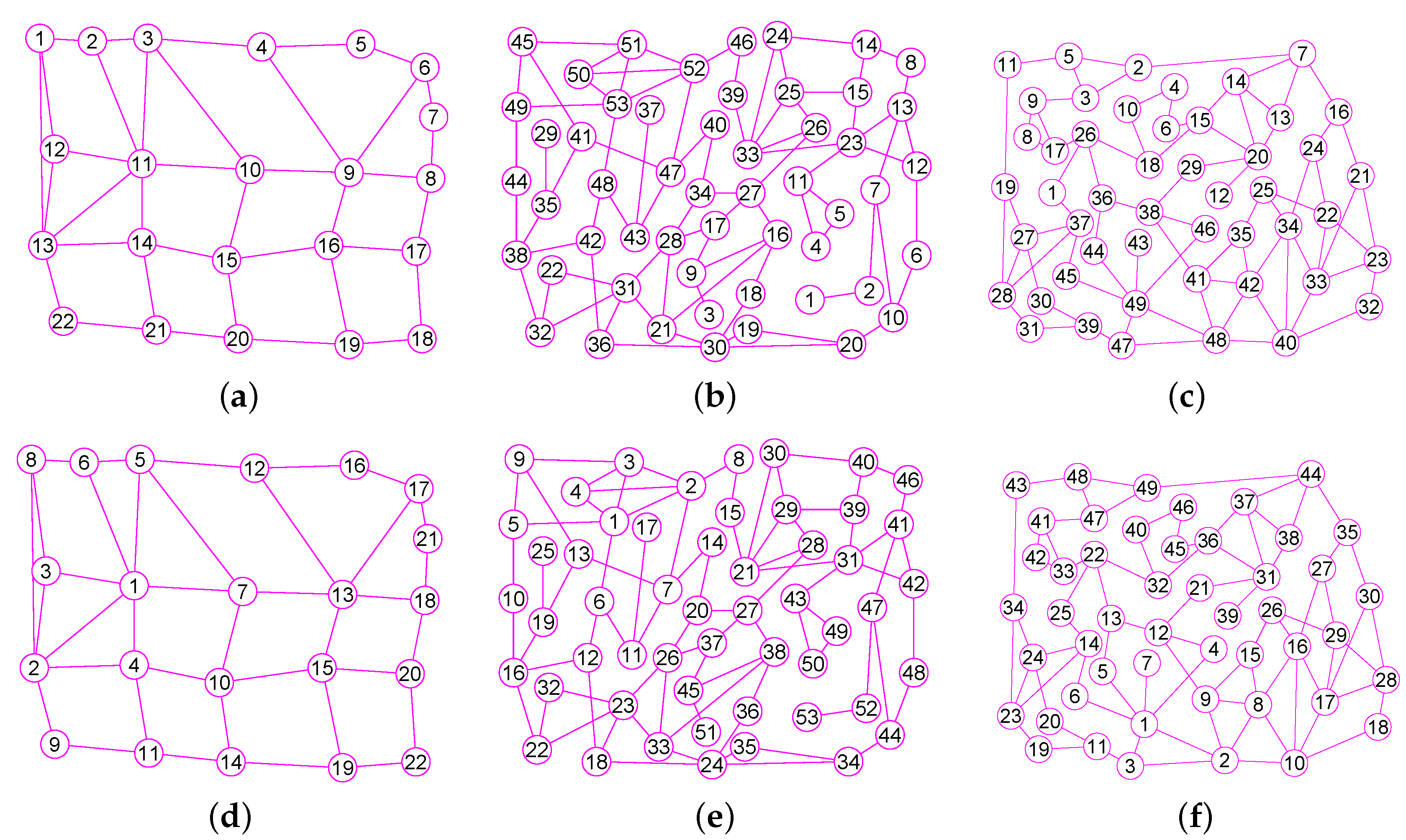

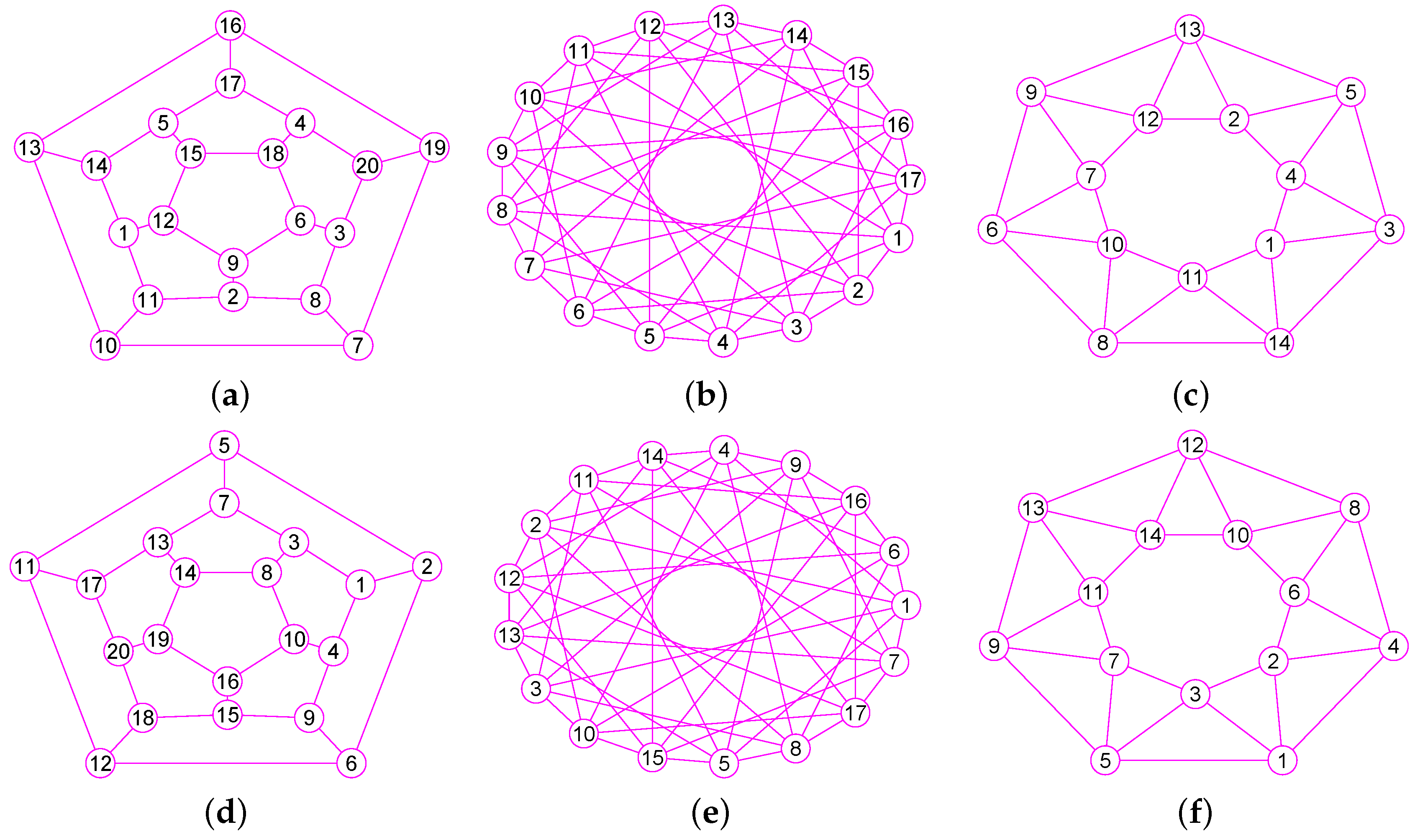

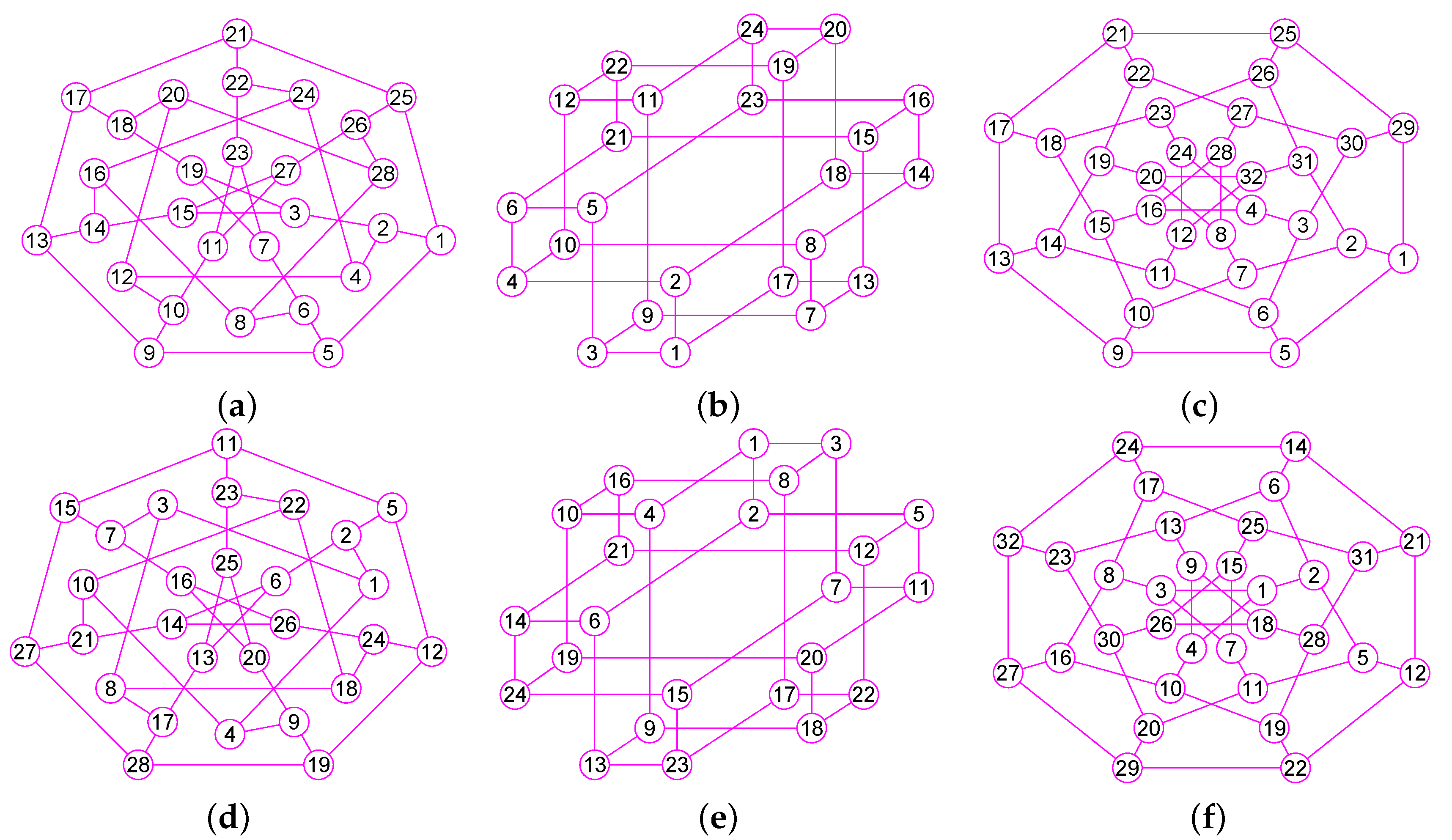

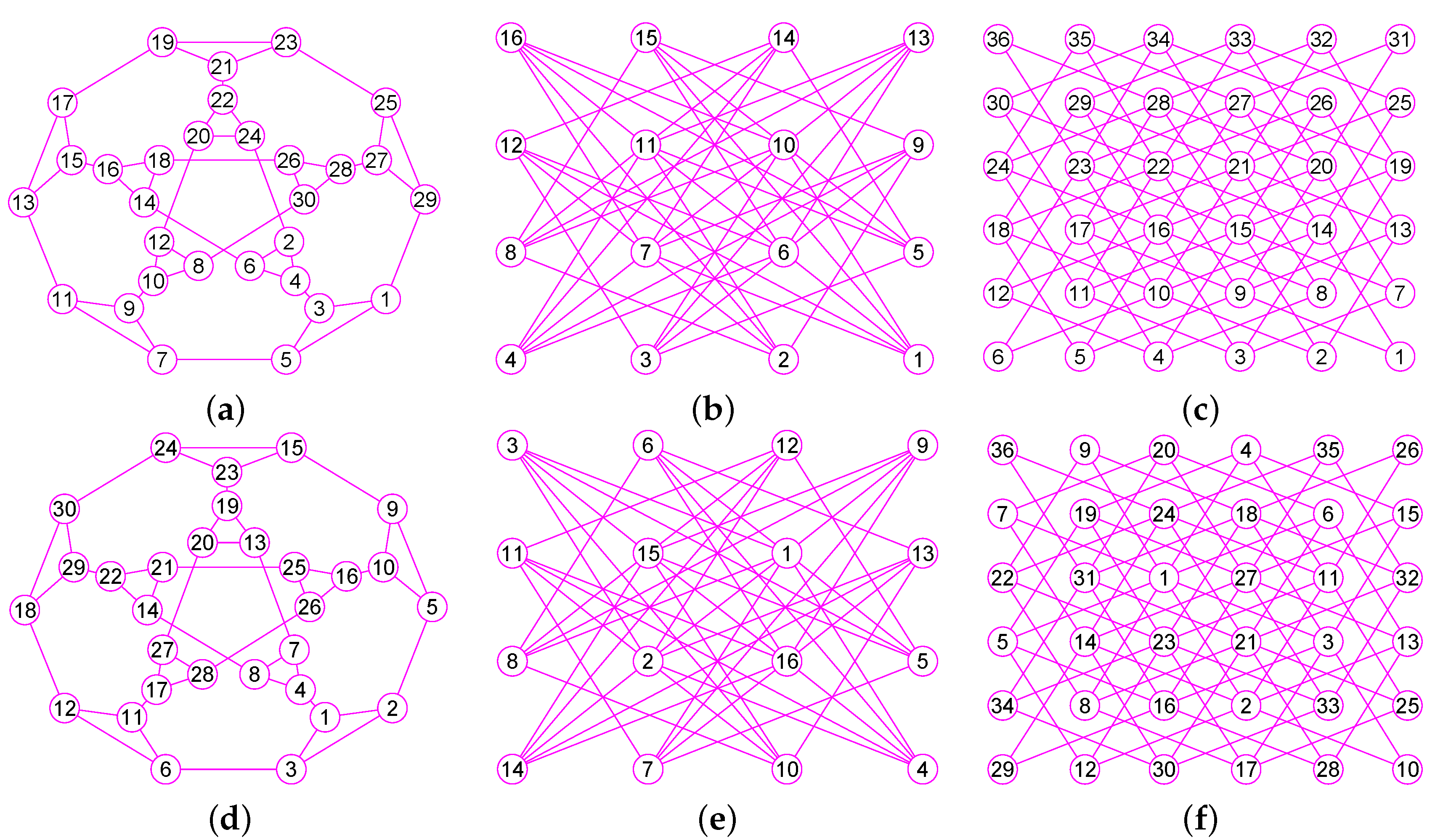

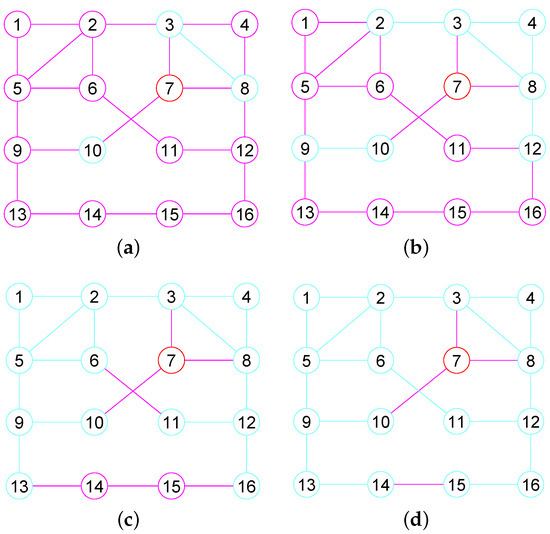

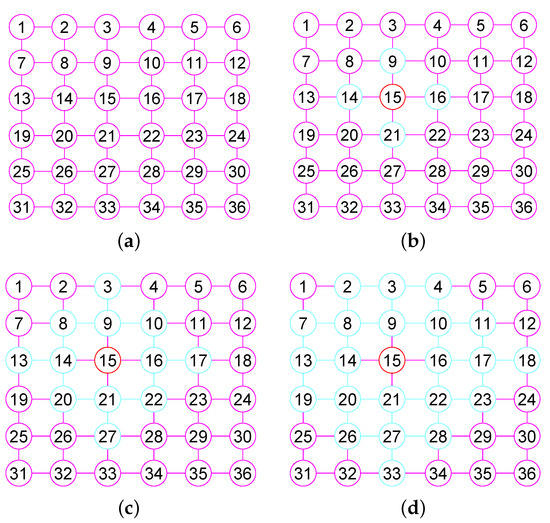

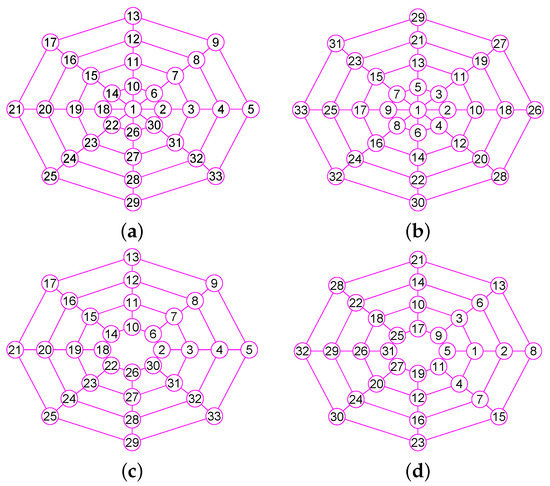

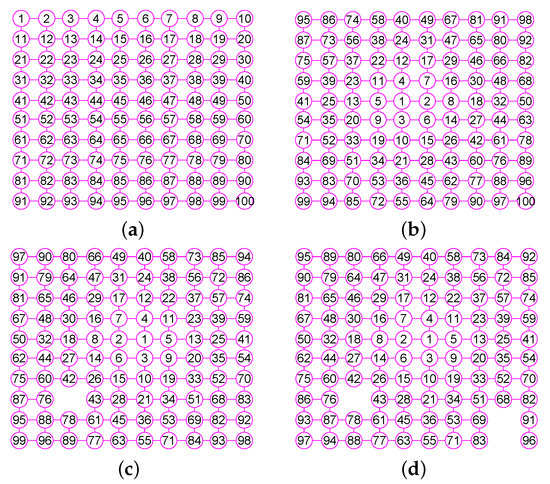

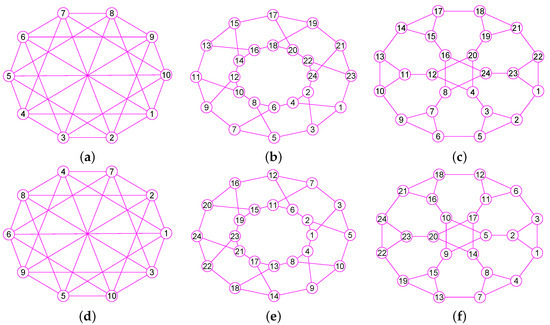

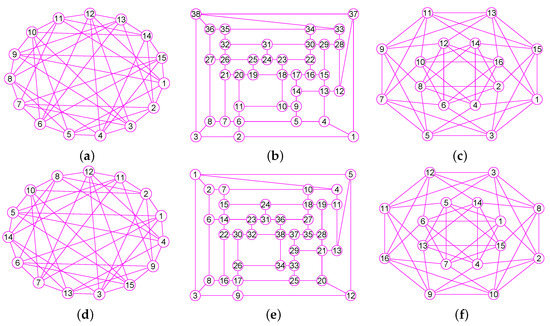

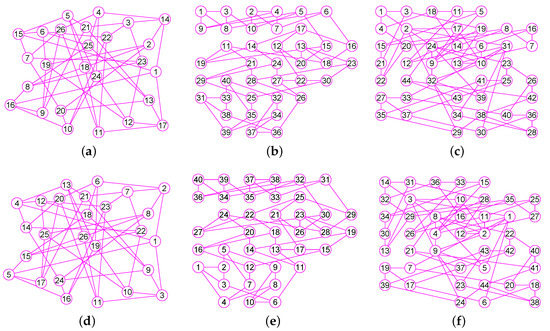

For every , an edge connecting two adjacent vertices of u is a of u and an edge connecting u and its an adjacent vertex is an of u. Given a set S of vertices in G, let signify the of all nodes in S and signify the of all vertices in S. Such as in the graph G shown in Figure 1, the edge is a of the vertex 7 and each of the edges , and are its . and .

Figure 1.

The 1, 2, 3, 4-neighborhood subgraph of vertex 7 in a graph G. (a) The 1-neighbor subgraph; (b) The 2-neighbor subgraph; (c) The 3-neighbor subgraph; (d) The 4-neighbor subgraph.

Definition 6.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. The open neighborhood subgraph of a node u in G is a subgraph of G, signified by , where is the set of all nodes adjacent to u () and is the collection of all edges, each of which connects two vertices of .

The k- of u with is a subgraph, signified by , with , .

Definition 7.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. The open neighborhood subgraph of a vertices set is a subgraph of G, signified by where is the set of all nodes each of which is adjacent to at least one node in Q with and is the collection of all edges each of which joins two vertices of .

The k- of Q with is a subgraph, signified by with , .

Remark 1.

For some graphs, there may be some edges whose two end vertices lie in but do not belong to by Definition 6. For example, consider the graph G given in Figure 1. Although the vertex 6 and 11 belong to , . In addition, the vertex 14 and 15 belong to . However, .

Definition 8.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. For each , the open kth neighborhood subgraph of u with is a subgraph, signified by with , . For , let and .

Definition 9.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. Assume that and . We signify by thek-of u in H and bythe of u in H. For , we drop the superscript 1 for clarity and write and , instead.

Definition 10.

Suppose , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices. For each , there is a positive integer k meeting conditions and . The value of k is defined as the of u, signified by and we drop the symbol G when no vagueness can occur.

By Definition 10, it is explicit that for each u in G. For notational convenience, we sometimes use as a shorthand for .

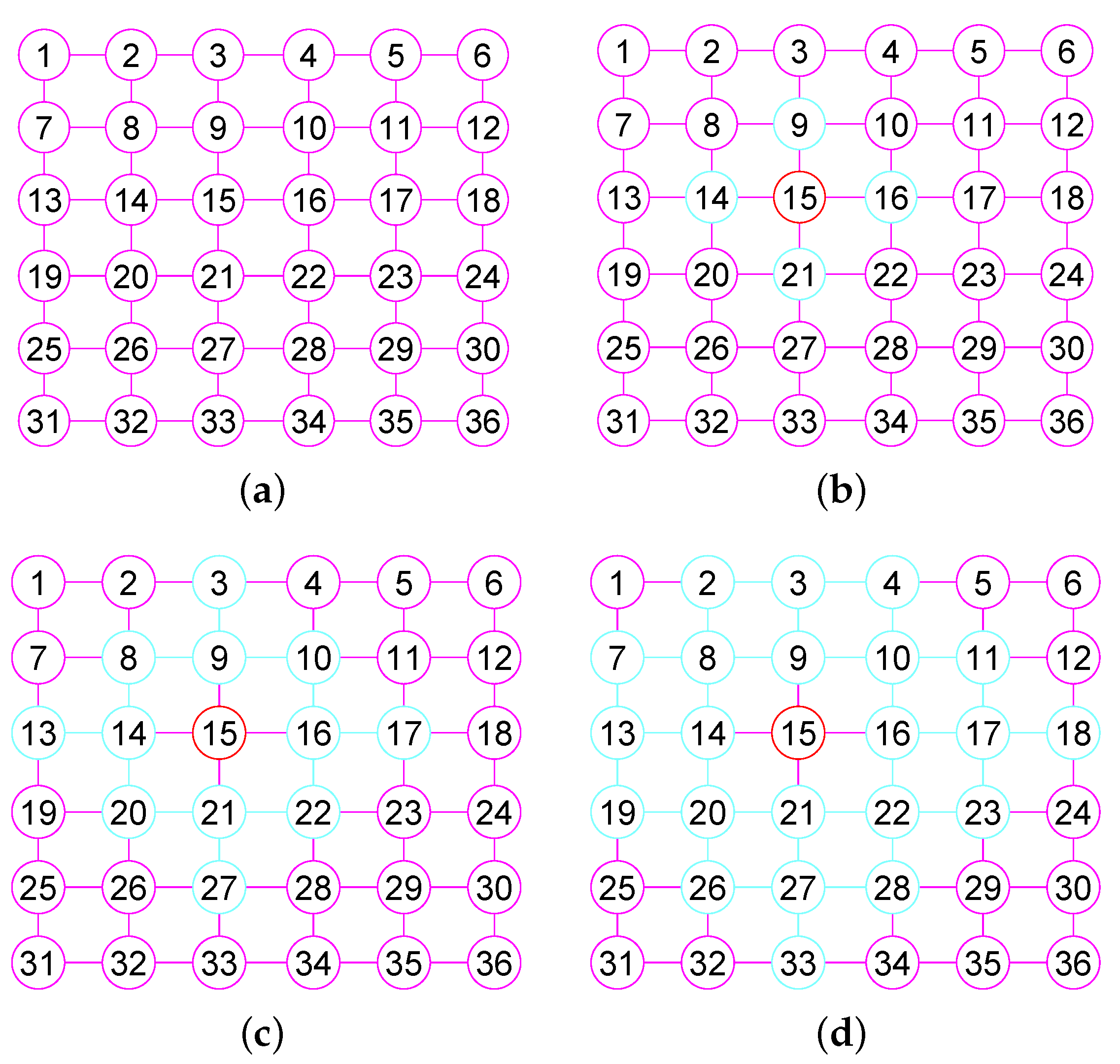

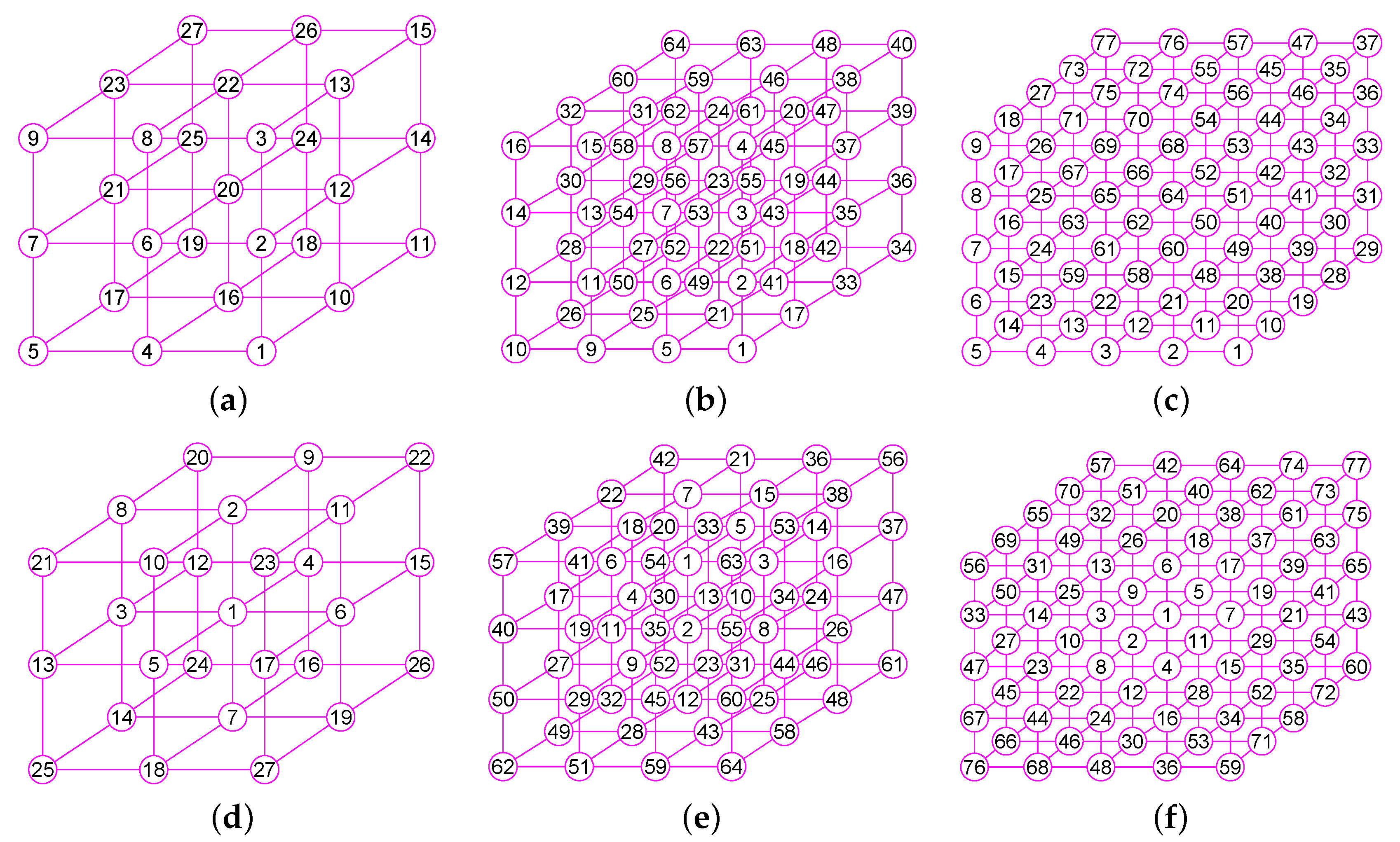

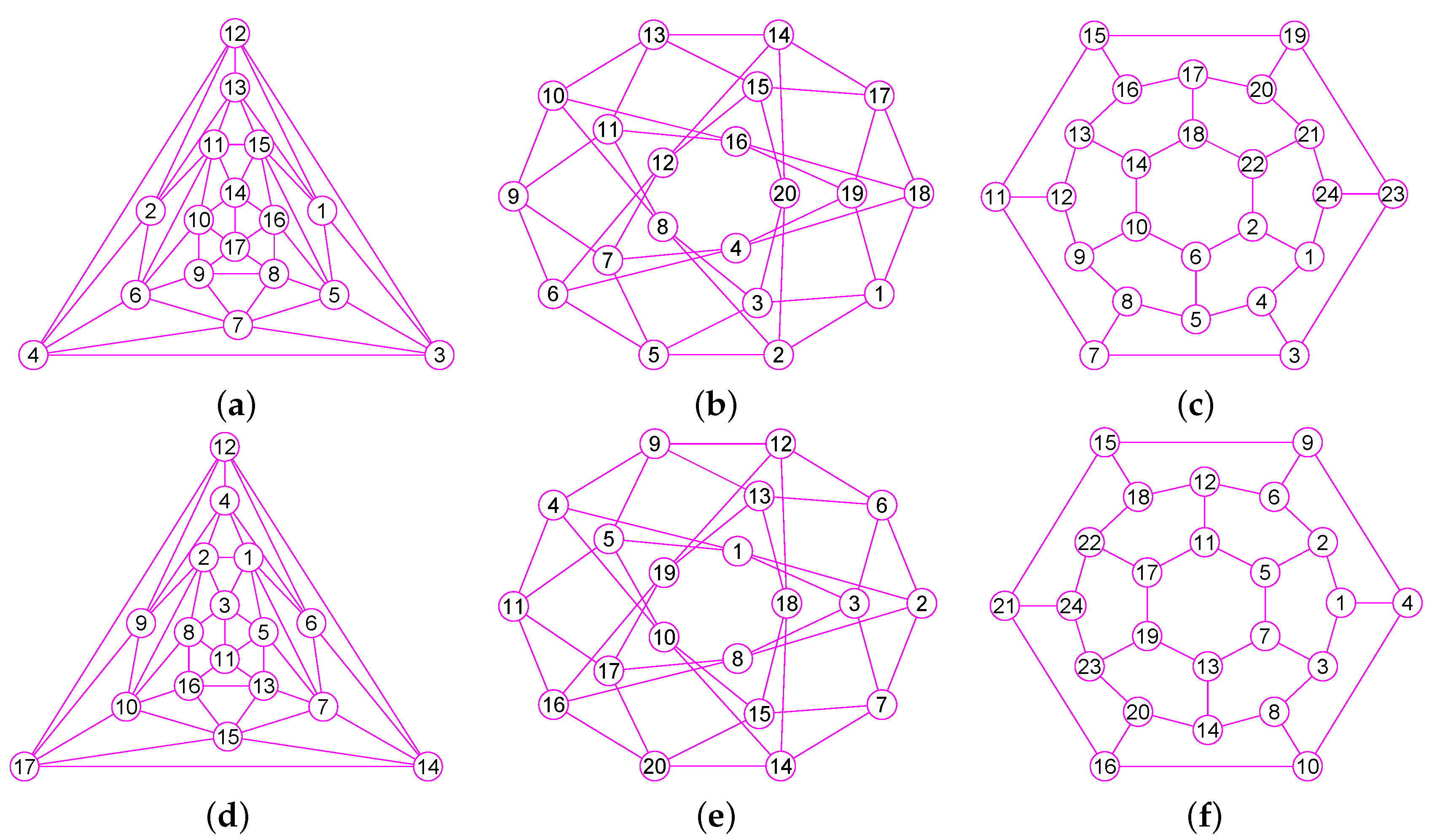

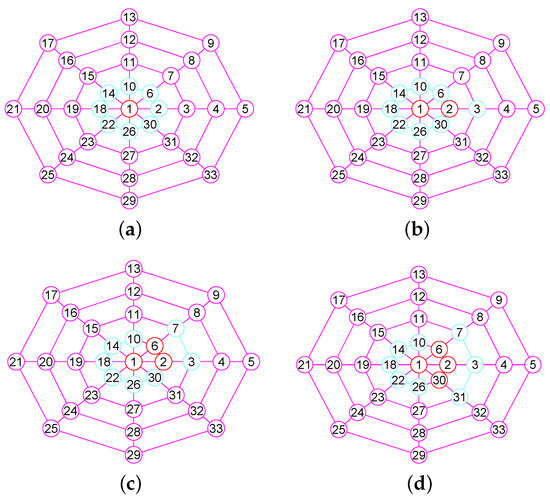

Here, we discuss the connection between the k- and with (see Figure 2). We present some basic properties of the k- by the following Lemma 2.

Figure 2.

The 1, 2, 3-neighborhood subgraph of vertex 15 in the grid graph . (a) The grid graph ; (b) The 1-neighbor subgraph of 15; (c) The 2-neighbor subgraph of 15; (d) The 3-neighbor subgraph of 15.

Lemma 2.

Let , , ⋯, , ⋯, be the -neighborhood subgraph of a vertex u in a graph G. If there exists a node , then

Likewise, if there exists a node with , then

By Lemma 2, it is clear that for every , satisfies or . According to whether v belongs to or not, can be partitioned into two disjoint sets and . Observe that and hold by Definitions 6 and 7 (see Figure 1). Therefore . and are the and of referred to as the and . Correspondingly, a vertex is a referred to as a and a vertex is a referred to as an .

Further note that with . Therefore, . The following Lemma 3 sums up the above discussion.

Lemma 3.

Suppose is the- of vertex u in a graph G. Then there exist two disjoint sets, the and the , meeting conditions

with , . Further, it follows that

Let and , then and hold for the neighborhood subgraph.

For the -neighborhood subgraph, holds with .

By Lemma 3, it can be seen that the calculation of the - can be simplified by means of the k- for every node v in G.

Definition 11.

Assume that , is an undirected graph and u is a vertex in G whose k- is with . A vertex in is a of u. For , a node v in meeting condition is a

k of u.

Definition 12.

Assume that , is an undirected graph and u is a node in G whose k- is with . Suppose H is a connected component of with . Suppose that with , where is in ascending order of attribute with

for every and , contain the of u respectively, meeting conditions and for .

Let , ⋯, , ⋯, be defined as the of H where with are the degree sequences in non-increasing order induced by all nodes in respectively.

Definition 13.

Assume that , is an undirected graph and u is a node in G whose k- k is with . Assume that has p connected components , , ⋯, with , , ⋯, respectively, meeting conditions .

We define , , ⋯, to be the of about u in G and drop the symbol G when no vagueness can occur.

We define to be the of about u in G and drop the symbol G when no vagueness can occur.

Remark 2.

To define , , ⋯, and , , ⋯, , we pay a great deal of efforts into software testing and theoretical studies. We used more than 20 different kinds of degree sequences in the software experiments and compared the results of distinct degree sequences. Built on the preceding works, it is not difficult to find that performance of the two degree sequences specified by Definitions 12 and 13 is optimal. With the adoption of the two definitions, the accuracy of our algorithm significantly enhances.

Given a graph G, the , , ⋯, can be used in the literature of finance for the jump-diffusion models [29,30].

Definition 14.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. For each with and, let , , ⋯, be the 1, 2, ⋯, neighborhood subgraph of u with , , ⋯, , respectively. Let , , ⋯, be the 1, 2, ⋯, neighborhood subgraph of v with , , ⋯, , respectively. Let , , ⋯, and , , ⋯, . If , we callconcerning G. Otherwise, if , we callconcerning G. Otherwise, if , we callconcerning G and ignore the sign G when no vagueness can occur. Signify or byand or by.

Observe that ≻, ≺, ≍, ⪰ are all binary relations on the collection of vertices . By Definition 14, for each with , one of the following assertions is true: (1) . (2) . (3) .

It can be noted that , is a well-ordered set, where ⪰ signifies the binary relation on the set . By the well-ordering theorem, it holds that there is a maximum and minimum element in , signified by and respectively with and . The superscript ⪰ can be ignored if no vagueness can occur. The following Lemmas 4–6 immediately hold from Definition 14.

Lemma 4.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. For each with , if the sign ⪰ signifies the binary relation on the collection , then, all of the vertices in G build a sole linkage L on G: with , , .

Lemma 5.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. Suppose u ∈ . For each with , if the sign ⪰ signifies the binary relation on the set , then, all of the vertices in build a sole linkage L on G: with .

Lemma 6.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. For each , Let be the k- of u in G. Suppose v ∈ .

For each with , if the sign ⪰ signifies the binary relation on the collection , then, all of the vertices in build a single linkage L on : with .

By Definitions 3, 4 and 14, the outcomes in the following Propositions 1 and 2 are uncomplicated.

Proposition 1.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. For each with , let , , ⋯, be the 1, 2, ⋯, neighborhood subgraph of u with , , ⋯, , respectively. Let , , ⋯, be the 1, 2, ⋯, neighborhood subgraph of v with , , ⋯, , respectively. Let , , ⋯, with , , ⋯, and , , ⋯, . Let , , ⋯, with , , ⋯, and , , ⋯, . If , then leads to . Otherwise, leads to . Otherwise, leads to . Accordingly, it follows that if , then leads to . Otherwise, leads to . Otherwise, leads to .

Proposition 2.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. For each with , let , , ⋯, be the 1, 2, ⋯, neighborhood subgraph of u with , , ⋯, , respectively. Let , , ⋯, be the 1, 2, ⋯, neighborhood subgraph of v with , , ⋯, , respectively. If , , ⋯, , , then concerning G (see Definition 14).

3. Results and Discussion

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. In the section, we will examine how to determine the of the graph G. The permutations of G associated with are the . Without loss of generality, let , . Throughout the article, all algorithms presented use an adjacency list to save the graph G.

3.1. Calculate for a Connected Graph

In this subsection, we consider how to determine the of a connected graph. What method should one take to calculate the ? From the relationship between and , a way for computing must first get the permutation associated with the adjacency matrix .

3.1.1. Calculate the First Node of

In this sub-subsection, we study how to calculate the first vertex of . Jianqiang Hao et al. employ the to determine the first node of for simple nonregular graphs [2]. This means that this method is invalid for regular graphs. Suppose that G is a connected graph with order . It can be seen that one must let maximize (see (1)). can always be taken because G is connected with order . Besides, to get , one must choose from . Only by so doing, can there be more “1” s in the high bits of such that guarantees maximum . Otherwise, cannot attain the maximum value. From the previous analysis, the following Proposition 3 and Lemma 7 hold.

Proposition 3.

Assume that , is an undirected graph of n vertices and ∈ }. Then the choice of of is from for getting .

Lemma 7.

Assume that , be an undirected graph of n vertices and ∈ }. If with . Then for .

For , the following Theorem 3 holds.

Theorem 3.

Assume that , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices and with . Let with and . For every with and =, if condition holds, then for .

Proof.

From (1), it follows that ⋯ and . Since , it can be shown that for .

By the conditions of Theorem 3, it is clearly that and . For clarity, let us suppose that , .

If conditions are satisfied for every and make the , then at most = with and (see (1). Otherwise, if let the , then = with and (see (1)).

Because , Theorem 3 follows by contrasting the above two outcomes of got. □

Theorem 4.

Assume that , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices and with . Let with and . For each with and , if conditions and hold, then for .

Proof.

From (1), it follows that ⋯ and . Since , it can be shown that for .

By the conditions of Theorem 4, it is clear that . For clarity, let us suppose that and .

If conditions are satisfied for every and make the , then at most = with , , =, = (see (1)). Otherwise, if let the , then = with , , =, = (see (1)).

Because , then the binary number ⋯ the binary number ⋯. Hence, Theorem 4 is established. □

Conjecture 1.

Assume that , is an undirected graph of n vertices and with . If there is a node meeting conditions for each , then for .

3.1.2. Calculate the Intermediate Nodes of

If our algorithm has calculated the first vertex of , how it determines the subsequent vertices for computing ? Observe that a side of G corresponds to 1 bit of the upper triangular part of the adjacency matrix . To maximize by maximizing , one must make belong to such that makes (see (1)). Otherwise, if , then (see (1)) and . The subsequent Proposition 4 captures the essence of the previous discussion.

Proposition 4.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. Given the first vertex of , then the choice of is from for getting .

Lemma 8.

Suppose , is an undirected graph of n vertices. Given the first vertex of , if there is a single vertex ∈ }, then for .

Proof.

By Proposition 4, it can be seen that the choice of is from for obtaining . By the condition of Lemma 8, we have that v is the only node of . Therefore Lemma 8 holds. □

Theorem 5.

Assume that , be an undirected connected graph of n vertices and u ∈ . For calculating , if already includes the first vertex with meeting condition and one of the following conditions is satisfied, then for .

- 1.

- for .

- 2.

- hold for with .

Proof.

(1). To maximize by maximizing (see (1)), it follows that must satisfy condition . By and the condition (1) of Theorem 5, hold for . Assume that . If , it can be seen that , by properly arranging nodes of (see (1)). Otherwise, if with , regardless of how the nodes in are arranged such that there exists at least one 0 among the t elements , since for (see (1)). Hence, the result (1) of Theorem 5 follows. (2). To maximize by maximizing (see (1)), it follows that must satisfy condition . By and the condition (2) of Theorem 5, we have that if , then is the largest canonical labeling 2. Otherwise, if with , regardless of how the nodes in are arranged such that the corresponding is not largest (see (1)). Hence, the result (2) of Theorem 5 follows. □

Our algorithm uses an adjacency list to store a graph G. To facilitate the calculation of the k- of a node v in G, it in advance saves all the adjacent nodes, and of v into an array, respectively. Moreover v contains three stand alone pointer to point to the start position of each array.

If our algorithm has calculated the first i nodes , of , how does it decide the following nodes , for computing ? From the previous discussion for getting , it can be noted that the choices of the subsequent nodes , of are from with .

Each vertex v of G is attached a characteristic . Once the ith vertex is added into , it records the index data i of in the property field of every vertex , , ⋯, with . If , then let for every with .

Lemma 9.

Assume that , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices and with . If with neighborhood subgraph , , , ⋯, , then , , ⋯, , ∈ , , ⋯, .

Proof.

Definition 15.

Assume that A and B are two matrices with , for . Then, the lexicographic order of the two matrix is defined as follows:

- 1.

- , if for all .

- 2.

- , if meeting conditions for all , and with or with .

Suppose X is a matrix. If there exists at least one positive entry and the remaining entries are 0, we say . Otherwise, if all entries of X are 0, we say .

Theorem 6

(Diffusion Theorem). Suppose , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices. If already includes the first m nodes for calculating , then the following two results follow.

- 1.

- the selection of the th vertex for computing is from the open neighborhood subgraph of the vertices set .

- 2.

- the vertex-induced subgraph of the first m nodes is connected.

Proof.

(1). We prove by contradiction. If , without loss of generality let us assume that , , is a permutation of , meeting conditions with .

Further, assume that if condition is satisfied, the associated with is the largest. Assume that the vertex is the vertex whose index i in is the smallest index in than the indexes of any other vertices belonging to in . This indicates that no vertex belonging to is between and of such that for each node , is met.

Let be the matrix associated with the arrangement . Let , , and be the block submatrices of including the first m rows and the th column, the th to th columns, the ith column and the th to nth columns, respectively.

Since , then is satisfied. Alike the above consequence acquired, for each vertex , , , is true such that . Clearly for .

By merely swapping and of , one can obtain another permutation , , , with .

Alike , let be the matrix associated with the permutation . Let , , and be the block submatrices of containing the first m rows and the th column, the th to th columns, the ith column and the th to nth columns, respectively.

Definitely, follows for . For each node , , as is true, then . Since , then holds.

Observe that since and are both the block submatrices associated with the same vertices sequence .

It follows from the results discussed above that , and , .

Hence, the new defined by is larger than the defined by such that makes a contradiction with the former hypothesis that . This contradiction proves that conclusion (1) is correct.

(2). Conclusion (1) immediately leads to the result. □

Theorem 7

(Nearest Node Theorem). Suppose , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices. If already includes the first m nodes for calculating . Assume vertices set .

If there exists a vertex , for every , meeting conditions <, then the node in is v.

Proof.

By Diffusion Theorem 6, we know that the th vertex in is from . We prove by contradiction. If the th vertex in is , satisfying condition <.

Let and . Without loss of generality, let us assume that , is a permutation of corresponding to v with . Let us assume that is a permutation of corresponding to w with .

This means that the corresponding to is less than the corresponding to .

Let , then .

By <, there are , , ⋯, , .

Let be the matrix associated with the permutation . Let and be the block submatrices of defined by the first i row and the th column and the th to nth columns, respectively.

Let be the matrix associated with the permutation . Let and be the block submatrices of defined by the first i row and the th column and the th to nth columns, respectively.

Since , then holds. Clearly holds due to . Therefore, . Again let .

For , , there must be . Then <. Therefore .

For , , there must be .

If , then <. The elements of the column vector corresponding to x in are all 0.

Otherwise, if , the elements of the column vector corresponding to x in are not all 0.

Thus, for , the matrix is such a matrix with only one column vector whose elements are not all 0 and the remaining column vectors are zero.

Hence, no matter how ; is taken, it can be seen that .

Let be a new matrix by combining and .

Let be a new matrix by combining and .

From the previous analysis, it follows that where is block submatrix.

Further, it follows that where is a column vector of i rows. The block submatrix is such a matrix whose only one column vector, denoted by Z, is not 0 and whose remaining column vectors are all 0. It can be seen that .

By the comparison of the matrix W and Y, it holds that .

Hence, the defined by is larger than the defined by . This contradicts the previous hypothesis that the corresponding to is less than the corresponding to . Therefore, the conclusion of Theorem 7 holds. □

Suppose , is an undirected connected graph of n vertices. For calculating , assume that already includes the first m nodes . Let with open neighborhood subgraph (see Definition 7). Let with vertex-induced subgraph .

3.2. Calculate for a Disconnected Graph

Suppose , is a disconnected undirected graph of n vertices with p connected components , , ⋯, . In this subsection, we consider how to determine the of G.

If , how does our algorithm proceed to determine the of G? It can be seen that to get one had to order all nodes of every connected component with together when building the adjacency matrix . The outcome also holds from the proving of Diffusion Theorem 6.

First, we examine the characteristics of the adjacency matrix . When building the adjacency matrix , we order all nodes of every connected component with together. Observe that the adjacency matrix is a symmetric block matrix, every block of which is associated with a connected component. Next, we examine the link between and . Besides, we present how to determine the associated with the adjacency matrix .

Lemma 10.

Suppose , is a disconnected undirected graph that have two disjoint connected components , and , with k and l vertices respectively. Assume that

If , then meets the following equation:

where

Proof.

If is satisfied, then . By Proposition 3, it can be seen that to get , one must pick the node with the maximum degree from as the first node of .

Observe that to guarantee the maximization of , one has to add l 0 after , , ⋯, respectively, so that make be equal l 0.

Theorem 8.

Suppose , is a disconnected undirected graph of n vertices with p connected components , , ⋯, satisfying , , ⋯, . If > , then meets the following equation:

Proof.

We prove (13) by induction on the number p of branches. By the previous definition, it follows that for . Hence, (13) in Theorem 8 follows for . By Lemma 10, (13) is correct for .

By induction, assume that (13) is true for . In the following, let us prove that Equation (13) is also correct for . We can now think of the front k branch graphs as graph H. Therefore, (13) is also true for graph H.

where

By Lemma 10, we have

Thus, we have

Therefore, Equation (13) is correct for . □

By Theorem 8, it can be observed that for getting , one has to first calculate of every branch for , respectively. Besides, one must substitute into (13) sequentially to obtain of a disconnected undirected G.

If the above conditions are not met, how does one determine of a disconnected undirected G? Based on an examination of the previous outcomes, the following Theorem 9 that is more useful than Lemma 10 is established.

Theorem 9.

Suppose , is a disconnected undirected graph that have two disjoint connected components , and , with k and l vertices respectively. Let ∈ } and ∈ } meeting condition for and . Assume that

If , then satisfies the following equation:

where

Proof.

By the condition of Theorem 9, it follows that for and inequality holds. By Theorem 3, one has to pick the first node of from so that get .

By Diffusion Theorem 6, one must choose into from to get . Besides, by Diffusion Theorem 6, one has to pick the following l nodes into from . By (18) and (19), it can be seen that (21) is correct.

where

It can be observed that to guarantee the maximization of , one has to add l 0 after , , ⋯, respectively and make be equal l 0. □

4. Our Algorithms for Calculating the Canonical Labeling

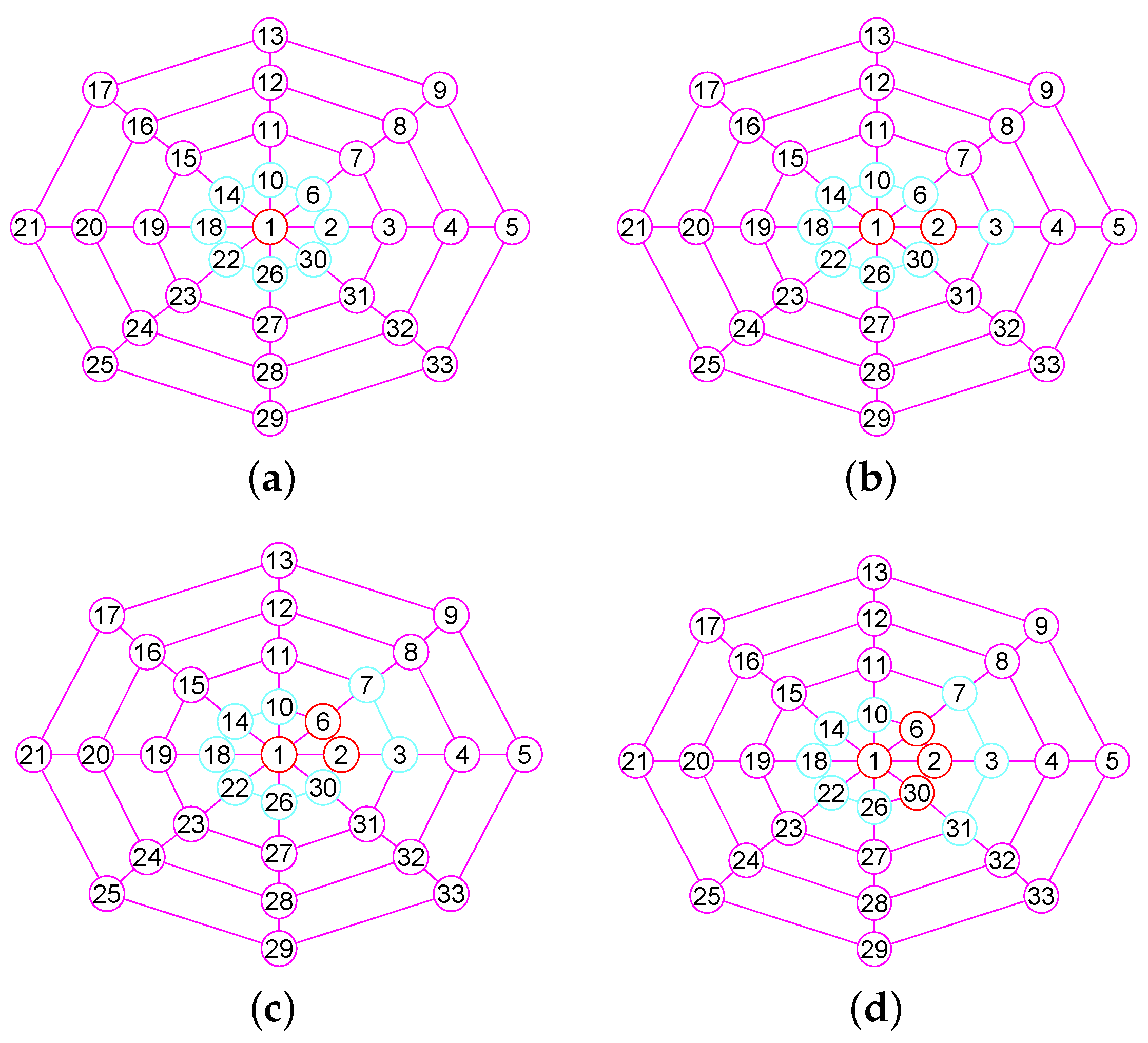

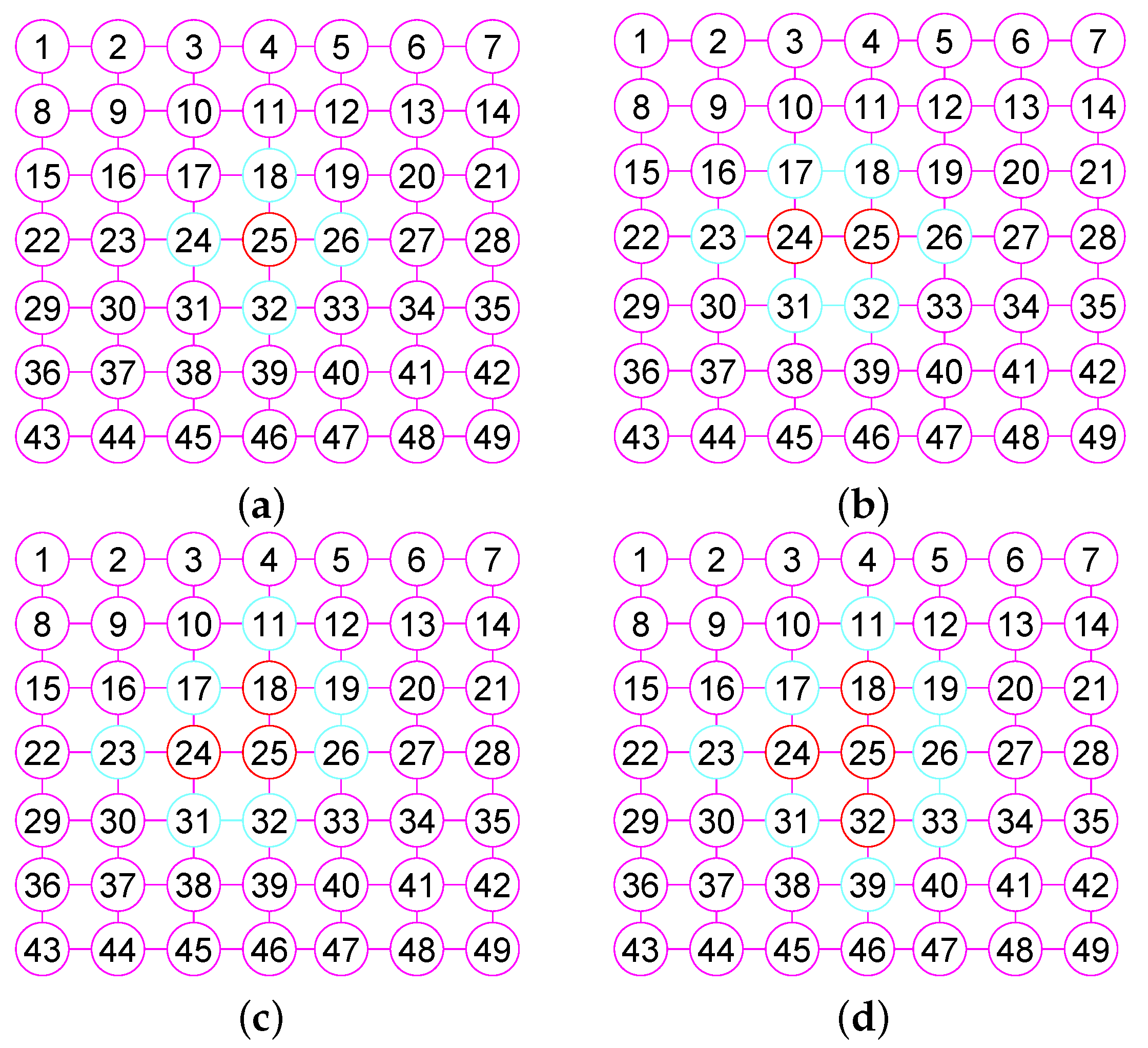

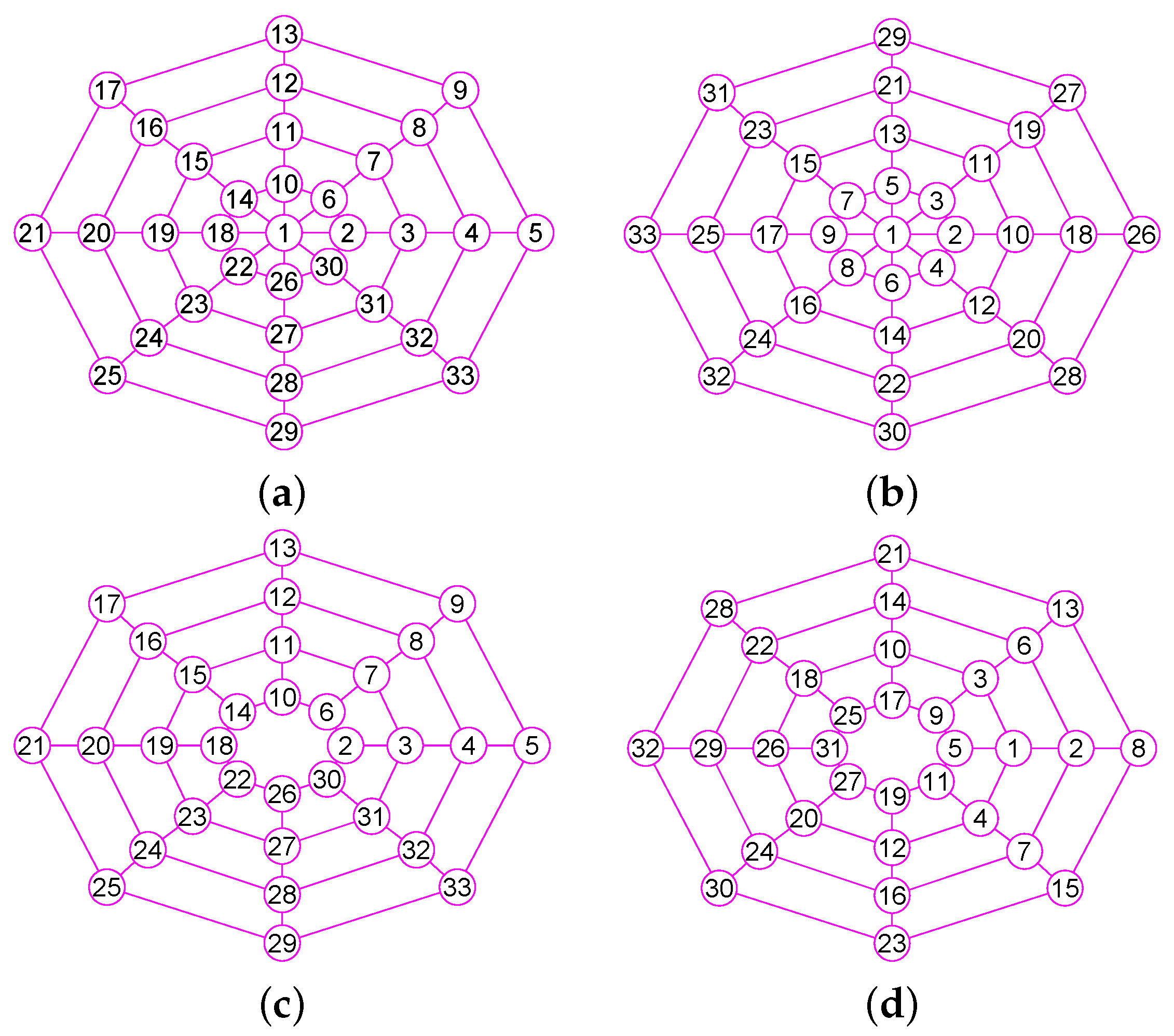

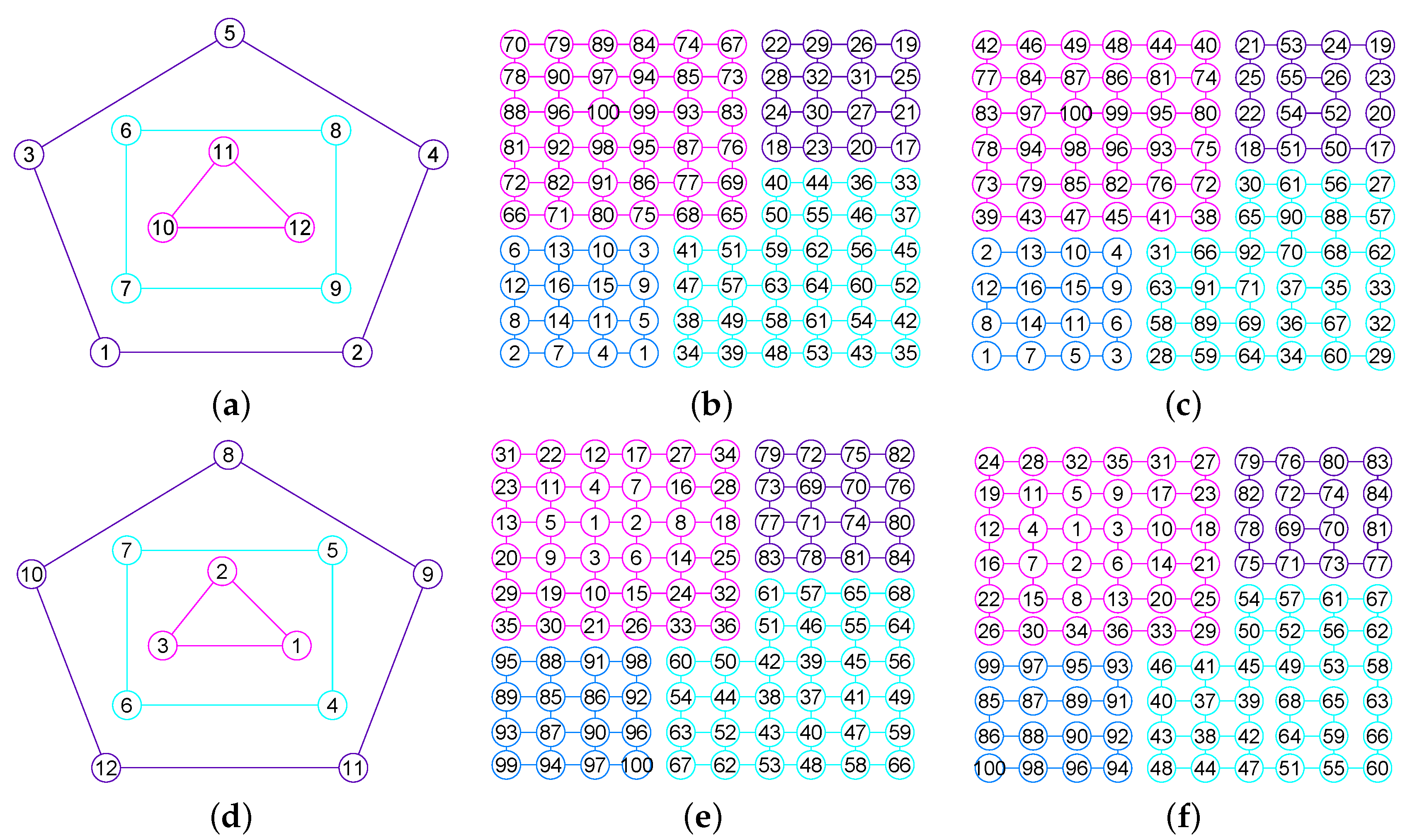

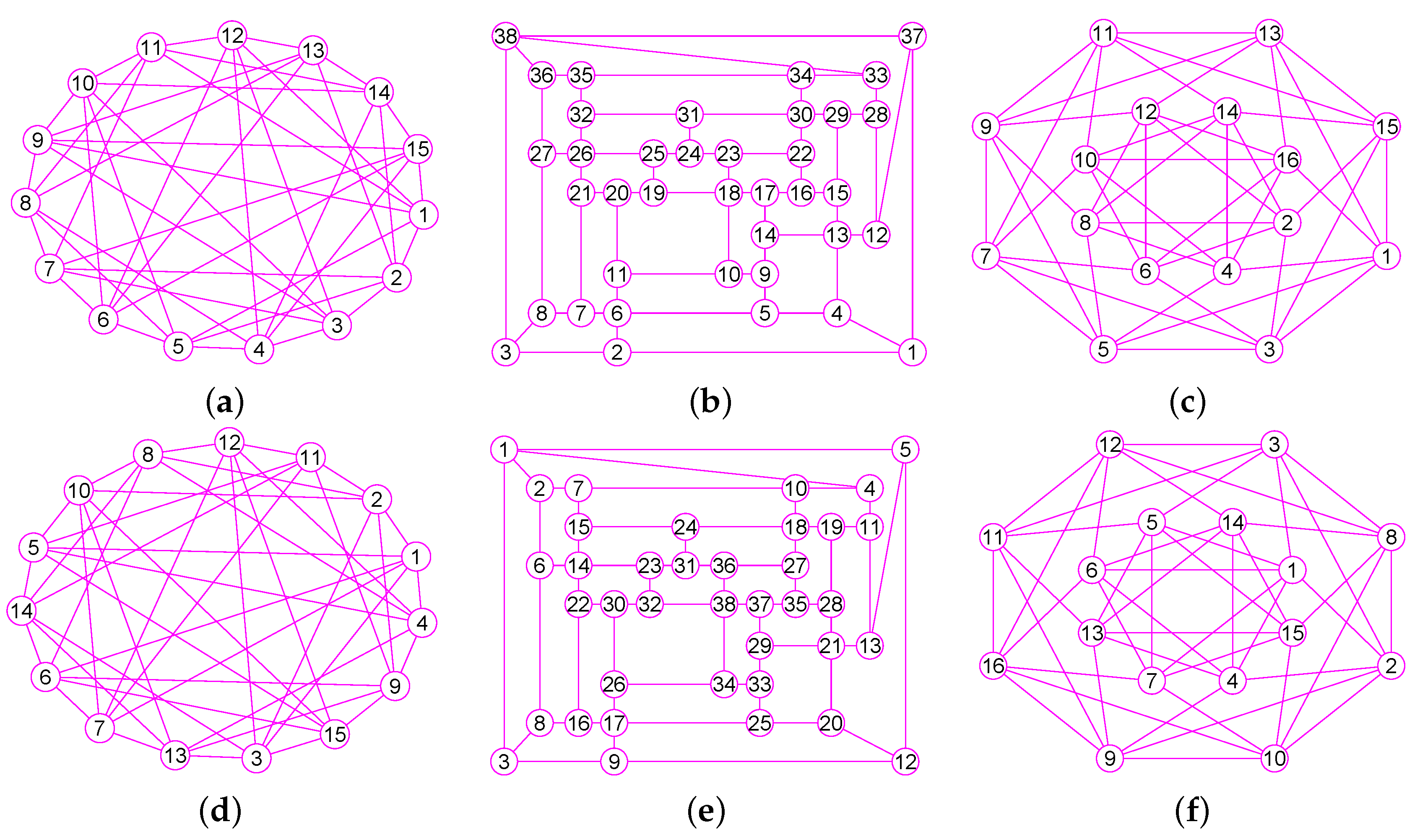

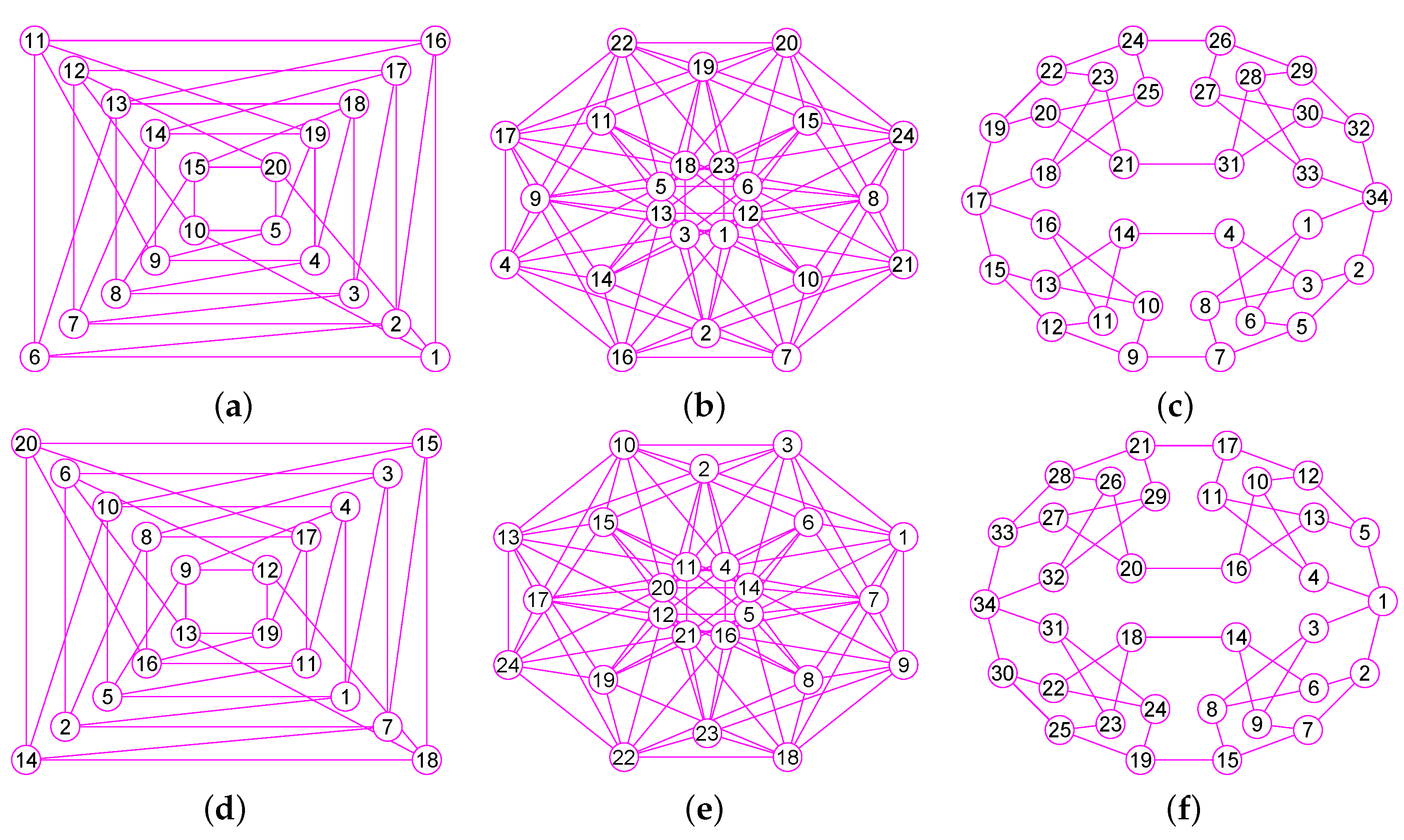

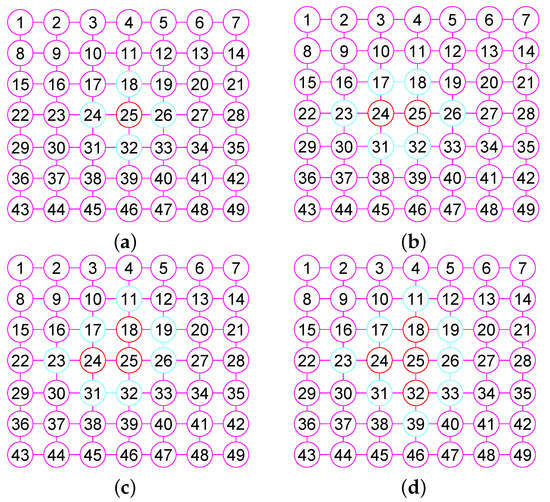

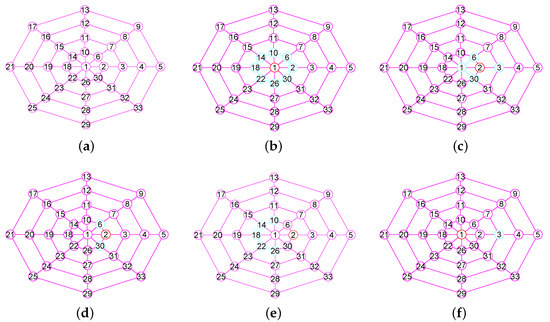

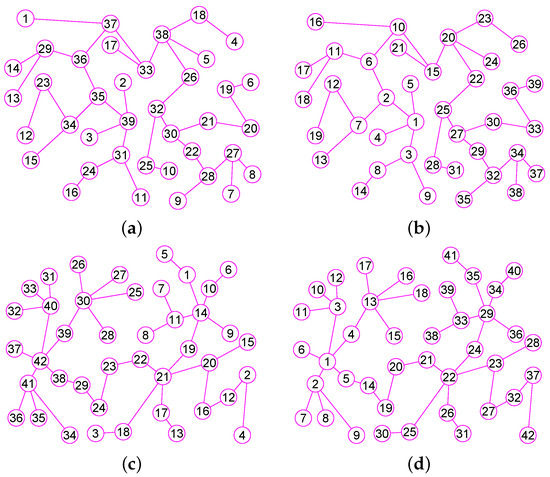

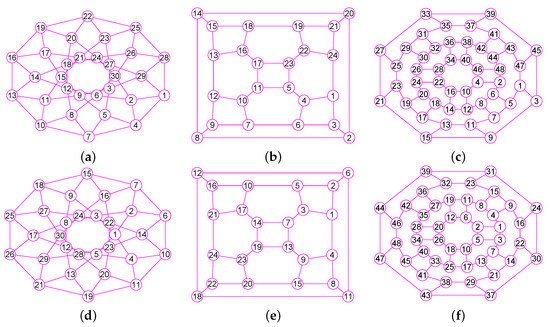

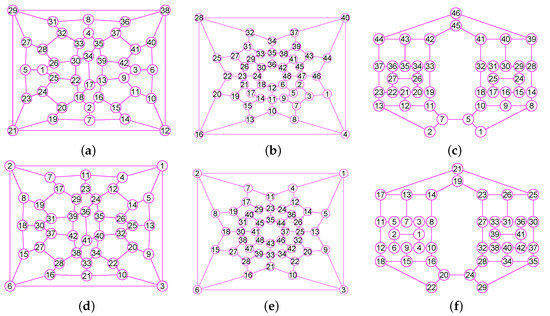

In the Section, based on the outcomes of the previous sections, we offer our algorithms for calculating of graphs. We describe the main steps required for calculating the of G. When our algorithm has computed the vertex of , then, it builds the neighborhood subgraph of the vertex (see Figure 3a and Figure 4a), from which it chooses a few nodes into . For the convenience of description, we name this process 1. Then once more, it constructs the neighborhood subgraph of the vertices set (see Figure 3b and Figure 4b), from which it chooses a few nodes into . We name this process 2. ⋯. Then once more, it constructs the neighborhood subgraph of the vertices set (see Figure 3c and Figure 4c), from which it chooses a few nodes into . We name this process r. ⋯. This process lasts until it places all nodes in G into (see Figure 3d and Figure 4d).

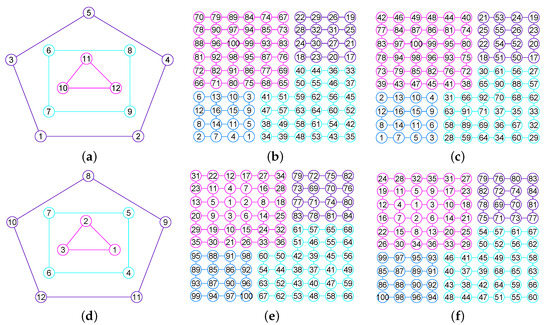

Figure 3.

The 1-neighborhood subgraphs for the different nodes sets of a wheel graph G. (a) A wheel graph G and the 1-neighborhood subgraph of the node 1; (b) The 1-neighborhood subgraph of the nodes set ; (c) The 1-neighborhood subgraph of the nodes set ; (d) The 1-neighborhood subgraph of the nodes set .

Figure 4.

The 1-neighborhood subgraphs for the different nodes sets of the grid graph . (a) A graph G and the 1-neighborhood subgraph of the node 25; (b) The 1-neighborhood subgraph of the nodes set ; (c) The 1-neighborhood subgraph of the nodes set ; (d) The 1-neighborhood subgraph of the nodes set .

For 1, after computing , by Lemma 4, our algorithm orders all vertices of into a sole linkage (observe Algorithm 1). For clarify, make . If there are two vertices meeting condition concerning , then it proceeds to decide whether or concerning G. If , it repositions in front of the in . Otherwise, it repositions in back of the in .

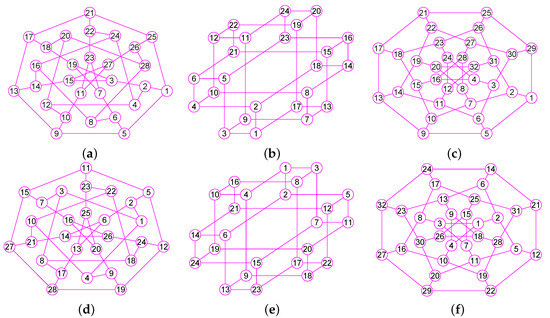

For every r, , when computing , our algorithm successively calculates (see Figure 5d), (see Figure 5e), (see Figure 5f) and the degree sequences , , in decreasing order respectively, where , . It can be shown that and for . By Lemma 4, it orders all vertices of into a sole linkage (observe Algorithm 1) for the neighborhood subgraph with , respectively.

Figure 5.

A wheel graph G, the 1-neighborhood subgraphs and and the three related vertices sets produced by the boolean operations of and . (a) A wheel graph G; (b) The neighborhood subgraph ; (c) The neighborhood subgraph ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) .

Next, our algorithm successively executes the following processing paces for the vertices of with :

- Beginning from the front of , it, in turn, decides whether every vertex meets the condition . If the number of nodes meeting condition is less than 2 in , it places u into . If there are two vertices meeting condition concerning , then it proceeds to decide whether or concerning G. If , it repositions the in front of the in (observe Algorithm 1). Otherwise, it repositions the in back of the in (view Algorithm 1).

- Excluding the vertices added into , it utilizes a queue Q to save the middle vertices of . After executing Step 1, it consecutively decides whether or not each node is in Q. If u is in Q and the number of vertices added into is less than 2 in the previous process, it inserts u on the tail of and concurrently deletes u from the head of Q. Otherwise, it places u on the back of Q.

- For , if the number of nodes of , added into , is 0 and the number of nodes meeting condition with is less than 2, it inserts u on the back of . The remaining procedure steps are the same as for .

- For , if the number of nodes of and , added into , is 0 and the number of nodes meeting the condition with is less than 2, it places u on the back of . The remaining procedure steps are the same as for .

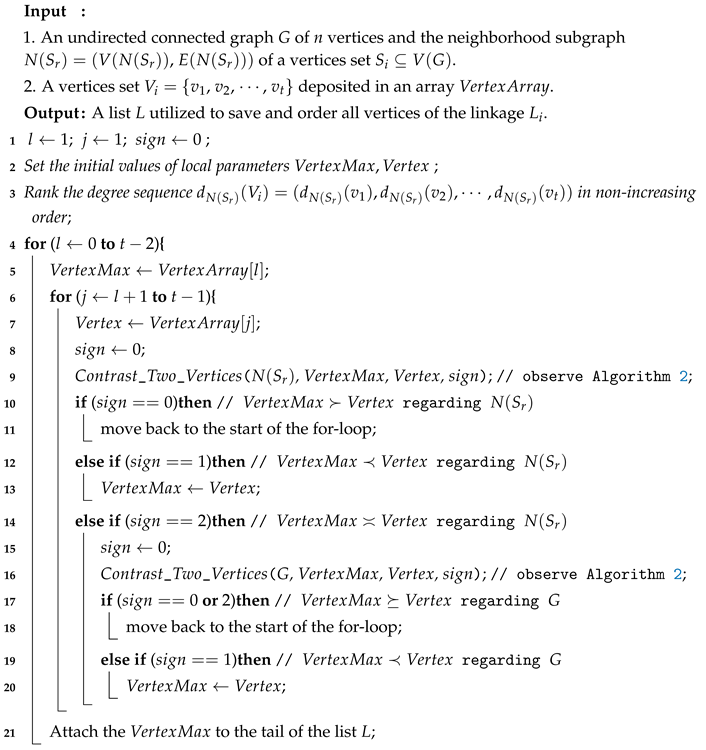

| Algorithm 1: Order all vertices of into a sole linkage for a neighborhood subgraph with , respectively where . |

|

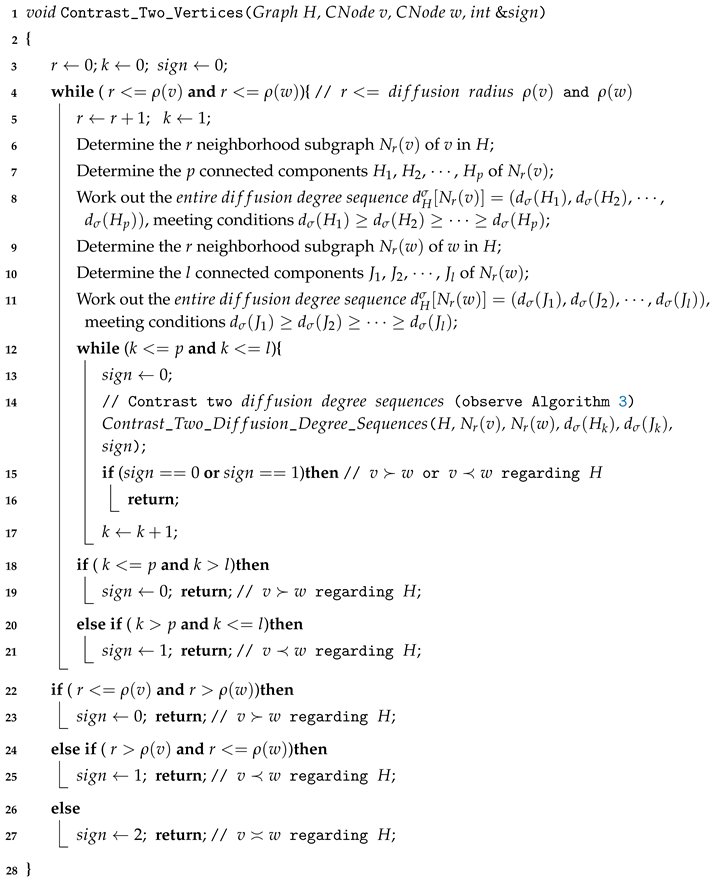

| Algorithm 2: Contrast the , , ⋯, and , , ⋯, of two vertices v and w in H. |

|

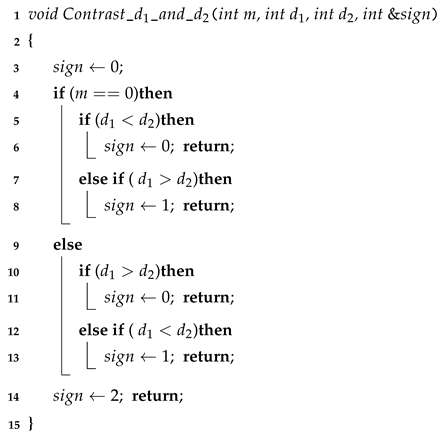

| Algorithm 3: Contrast two and of two vertices v and w in H. |

|

| Algorithm 4: Contrast and . |

|

Our algorithm utilizes an array to save the vertices of and an array Q to store the vertices to be added to briefly. Our algorithm has been optimized by Lemmas 2 and 3.

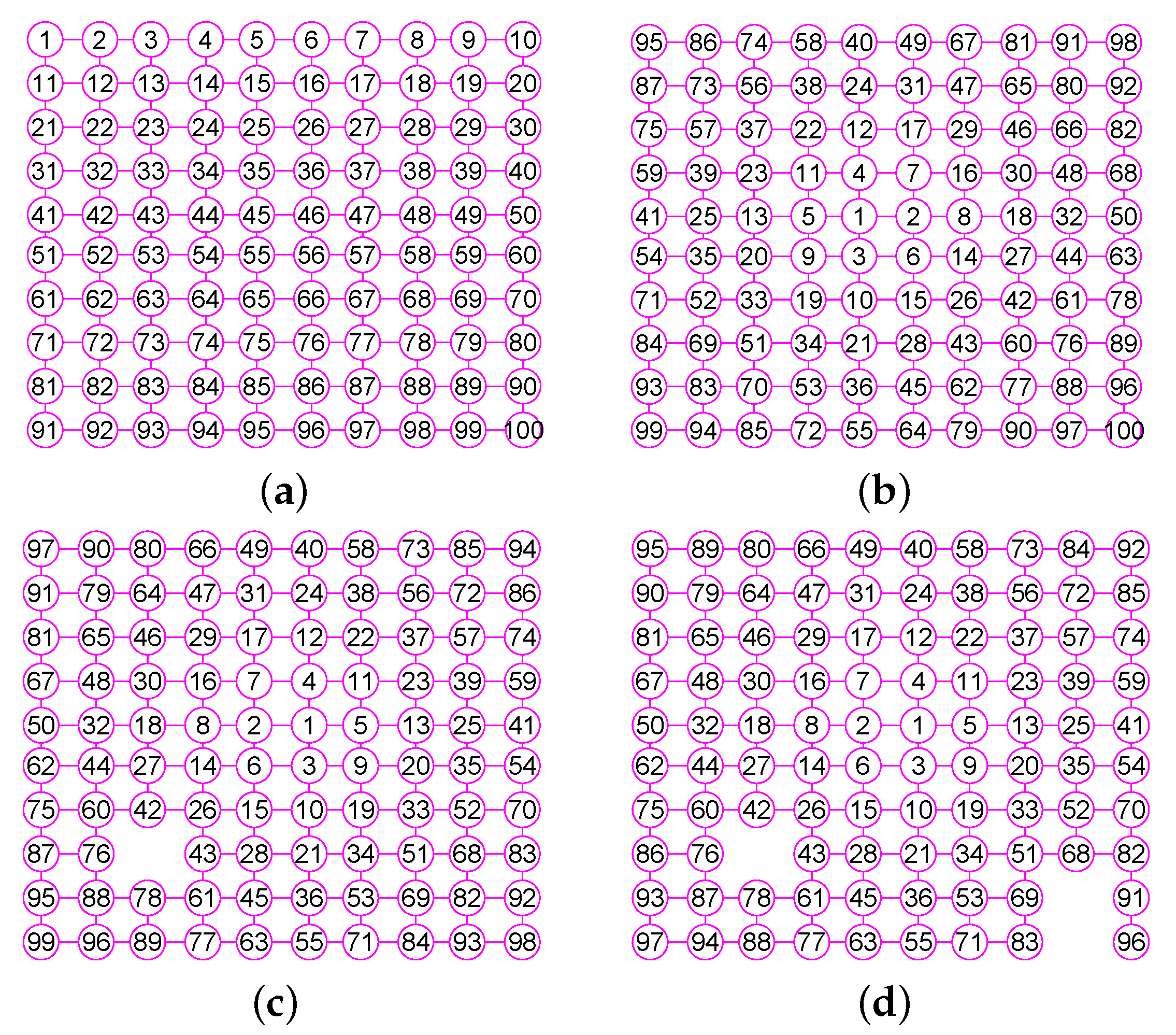

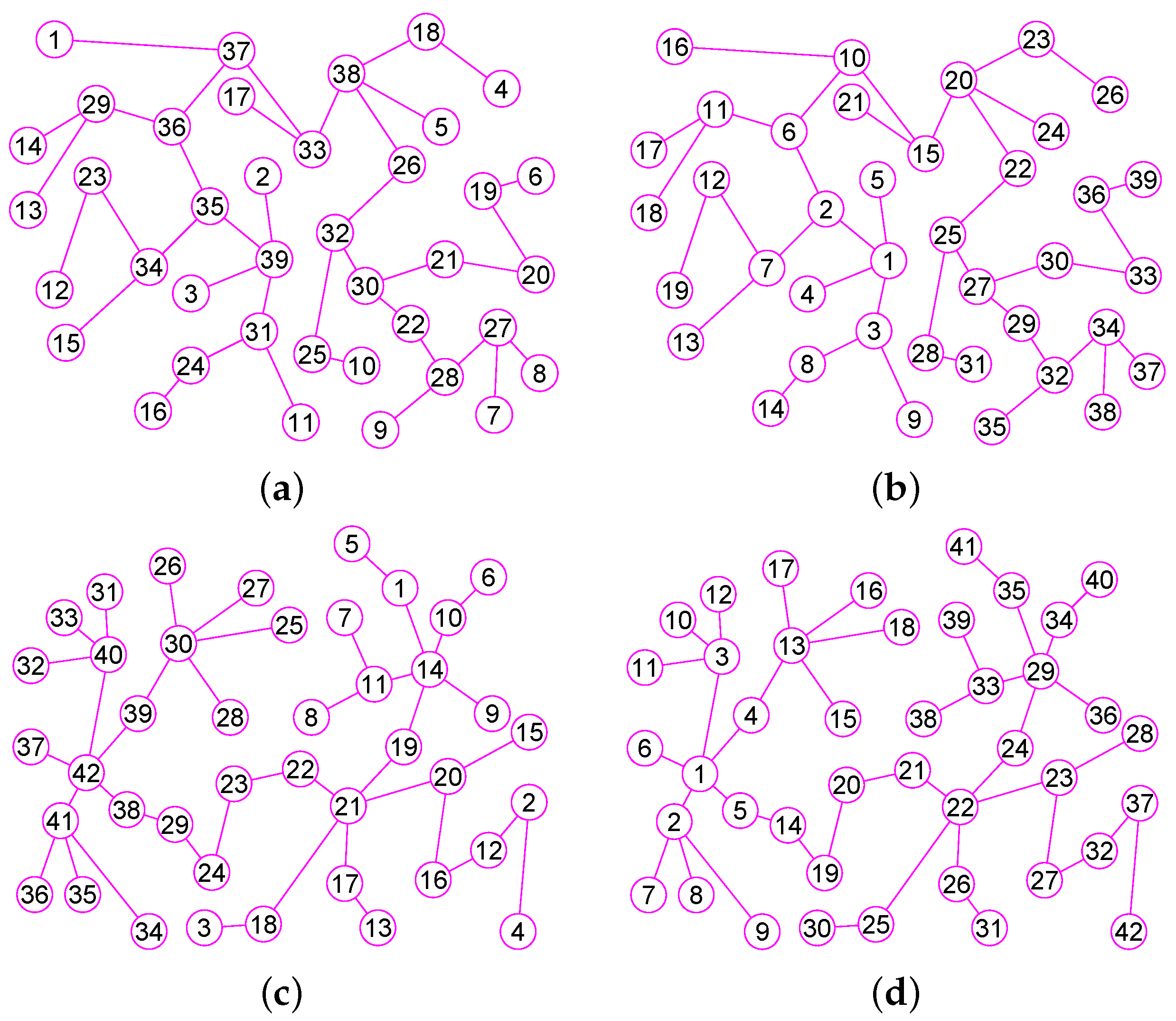

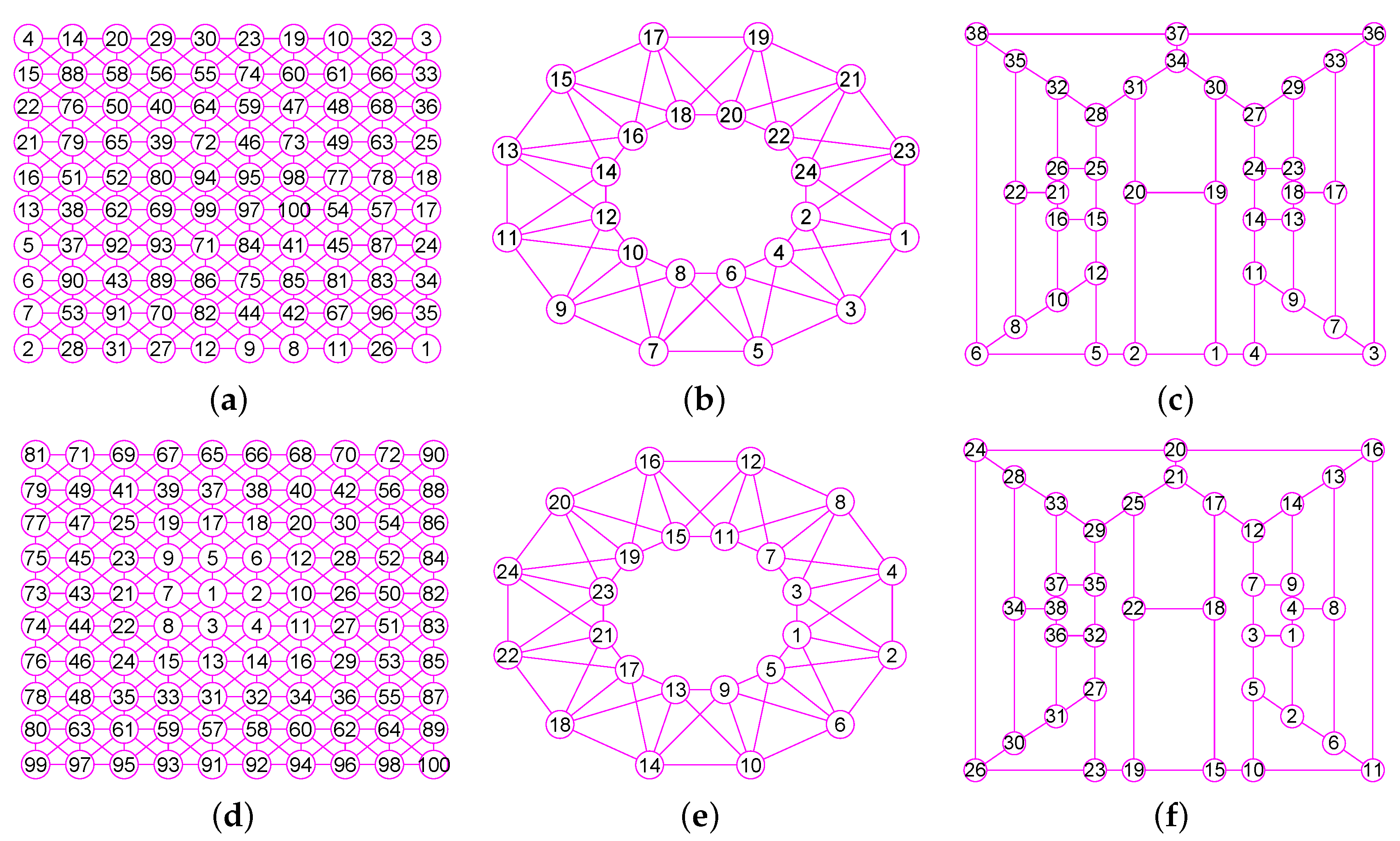

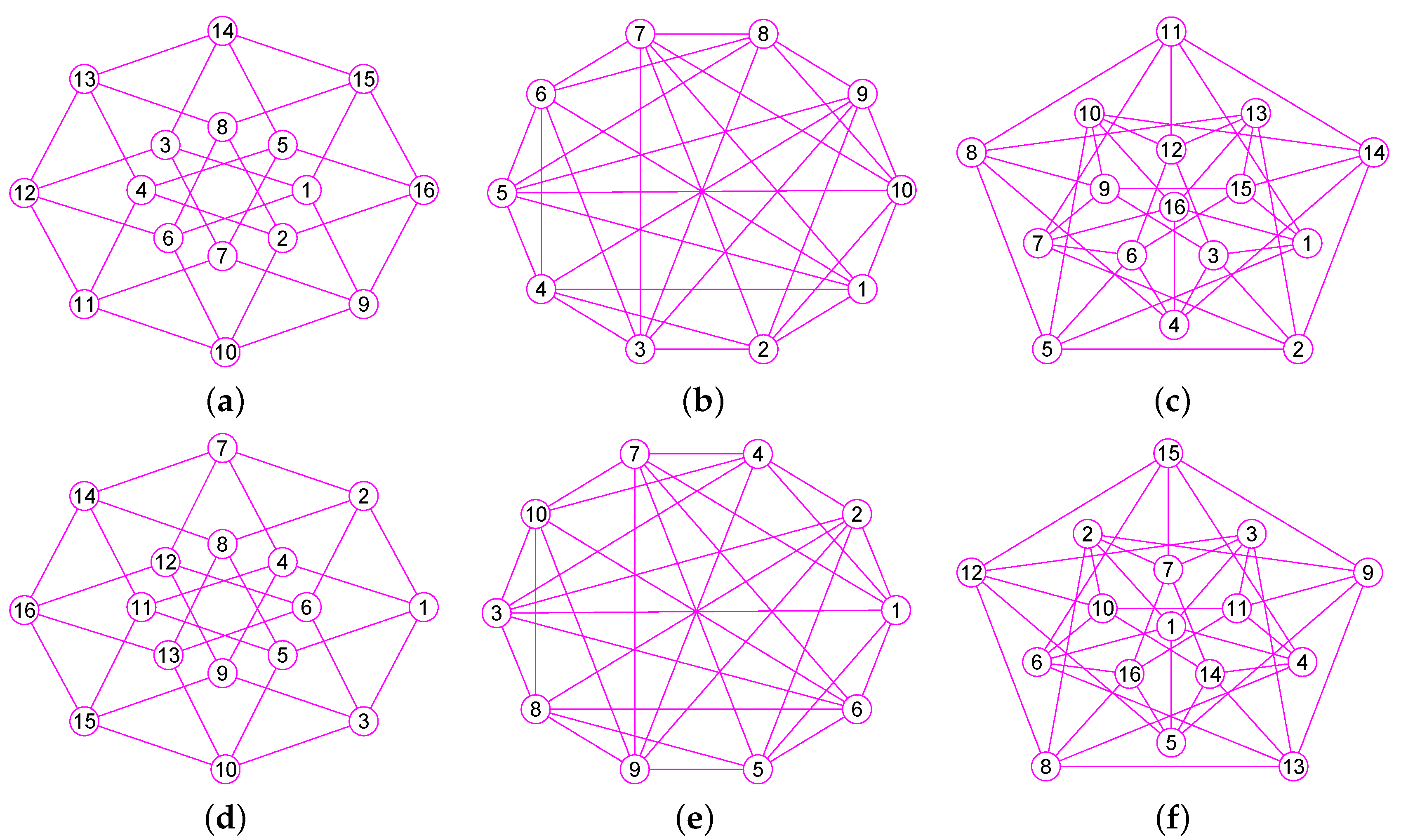

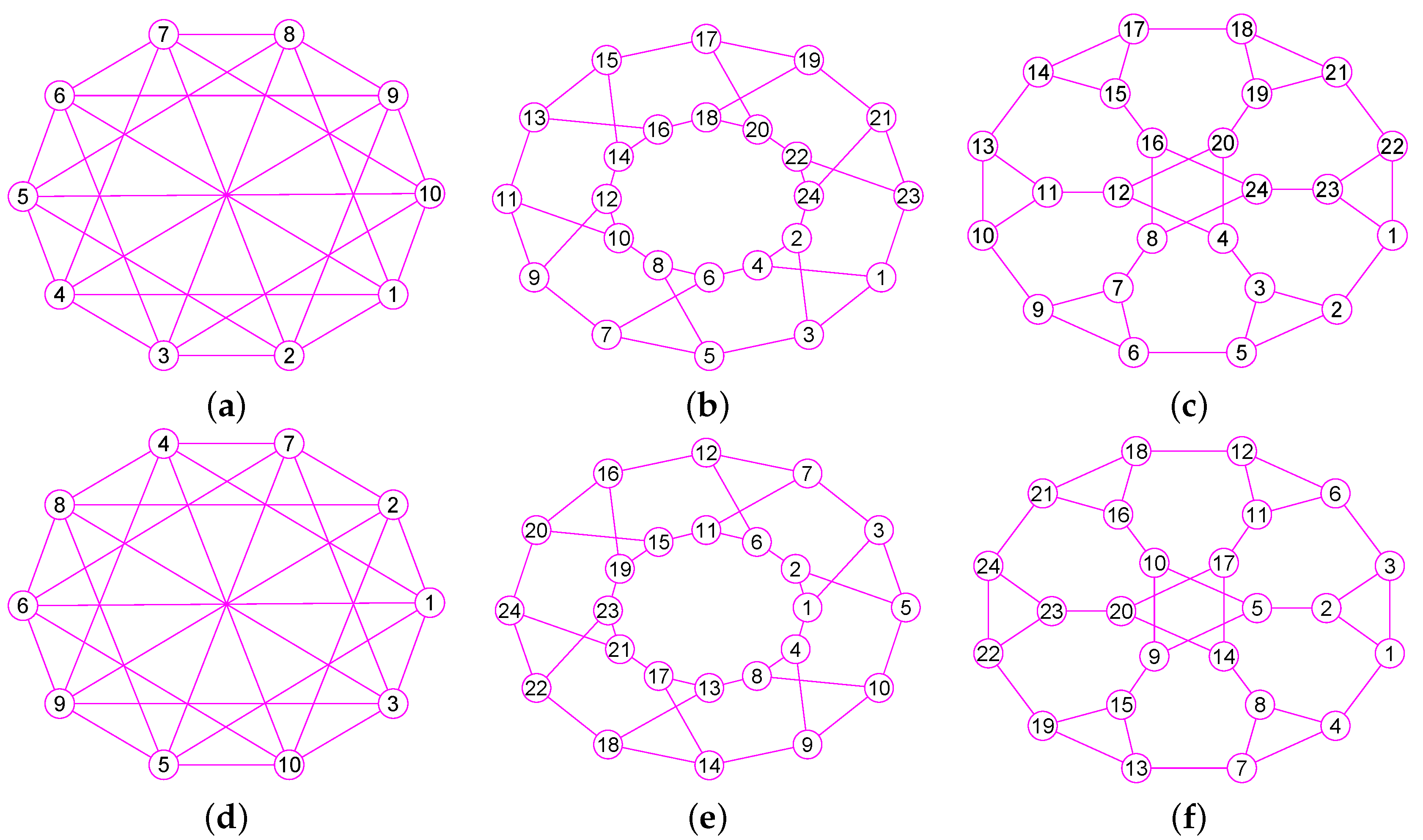

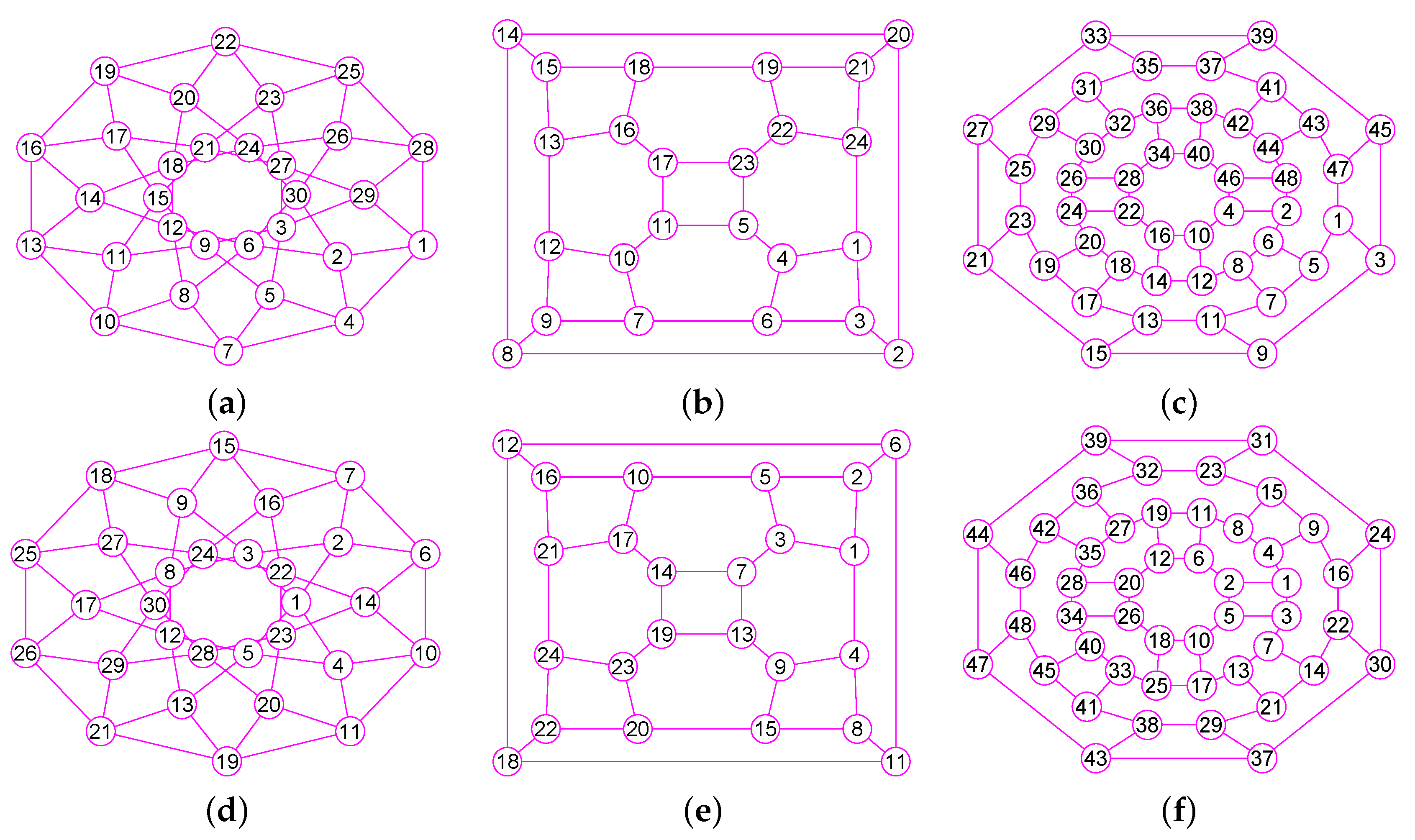

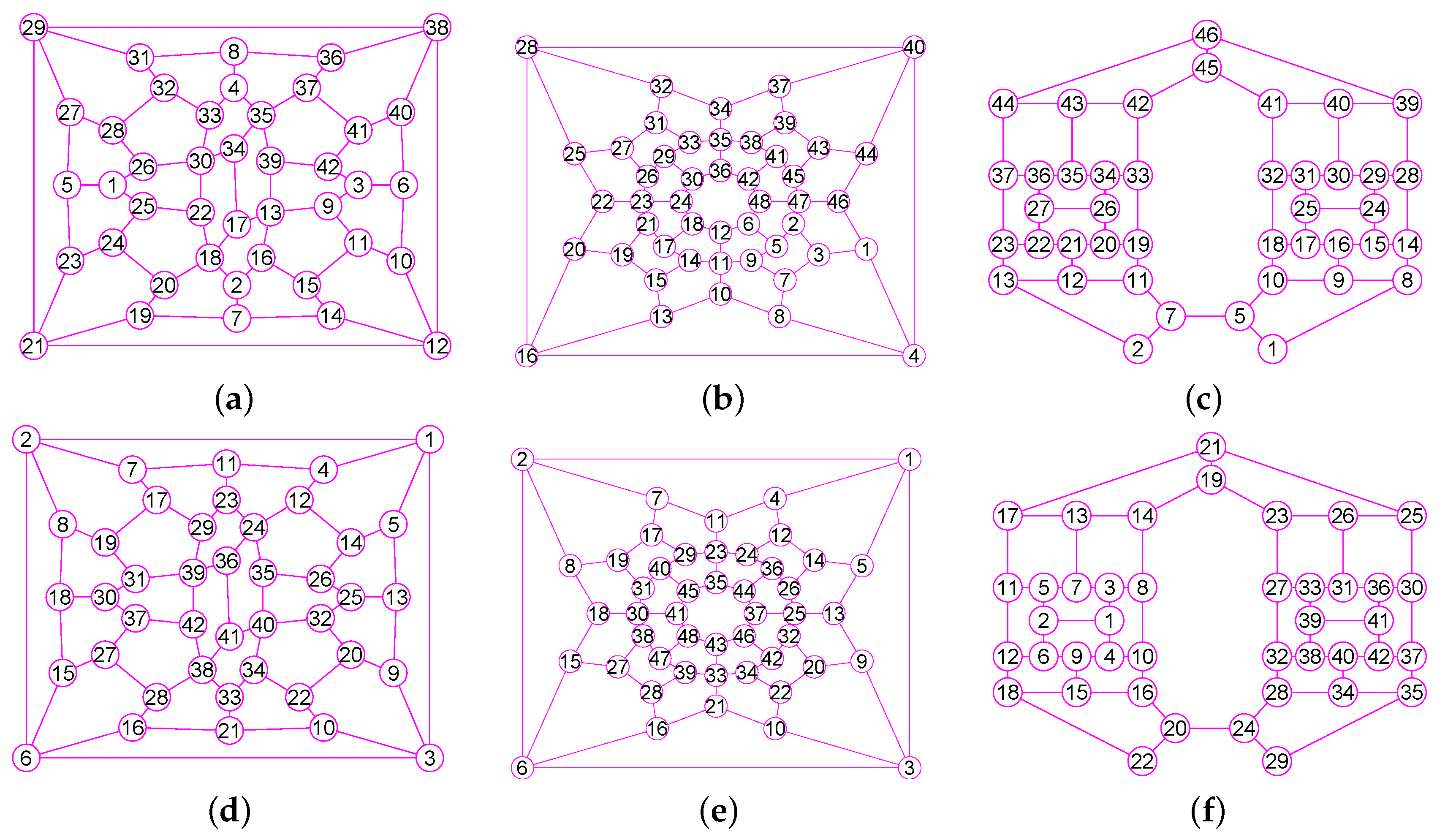

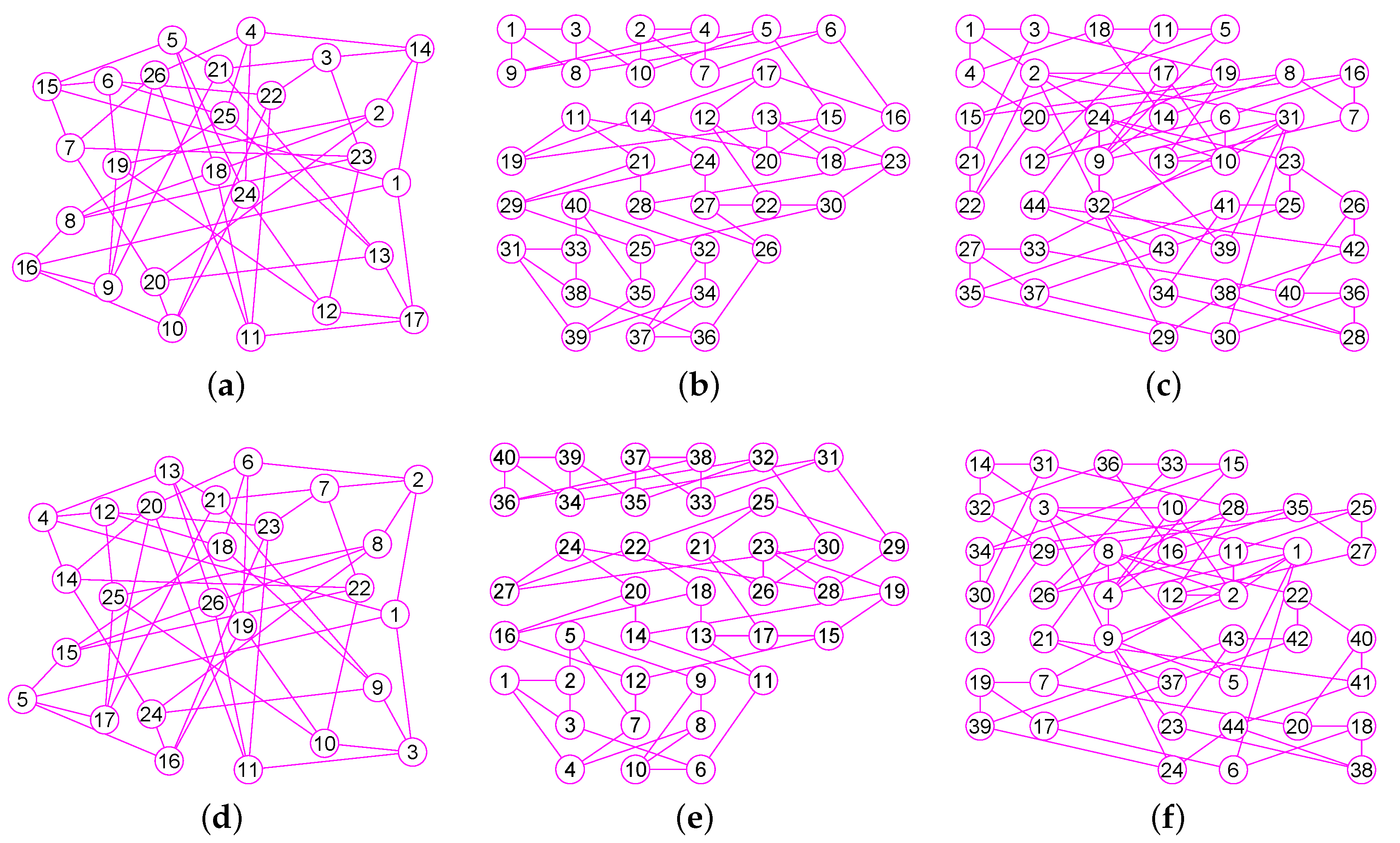

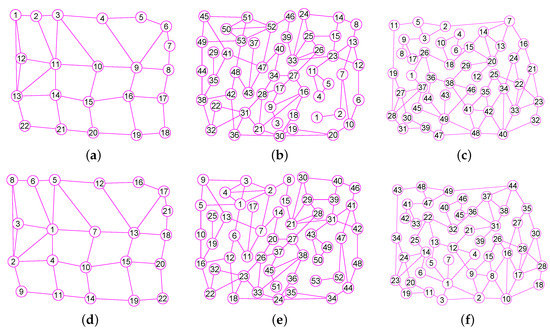

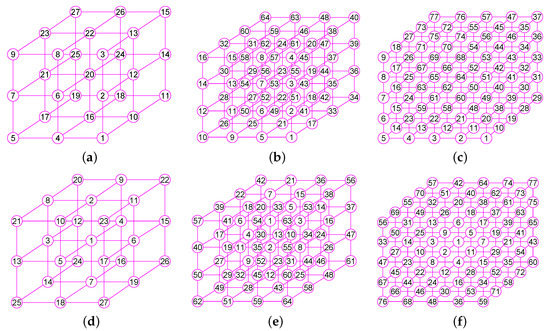

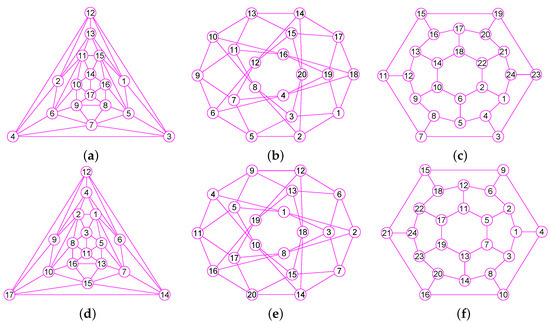

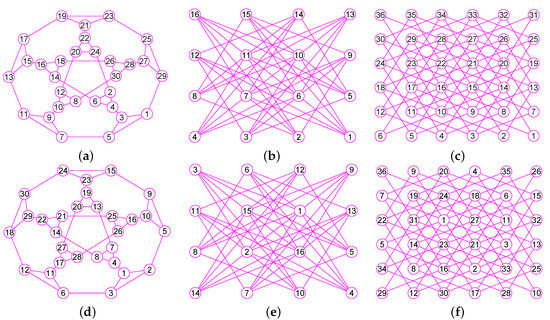

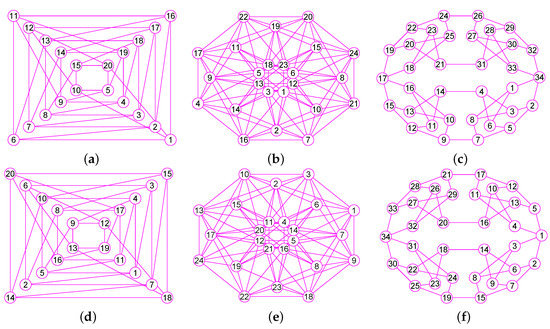

The results of experiments show that our method is a new approach by which one can precisely determine graphs (defined in Section 2) for many classes of graphs, including trees, grid graphs, wheel graphs, hypercube graphs, king graphs, triangular graphs and so on. Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23 given by our software display the accuracy of our software for computing graphs of these graph classes aforesaid.

Figure 6.

The graphs of two graphs, including a wheel graph G and the graph with . (a) A wheel graph G with 33 nodes and 64 edges; (b) The graph of G; (c) The graph of 32 vertices and 56 edges; (d) The graph of .

Figure 7.

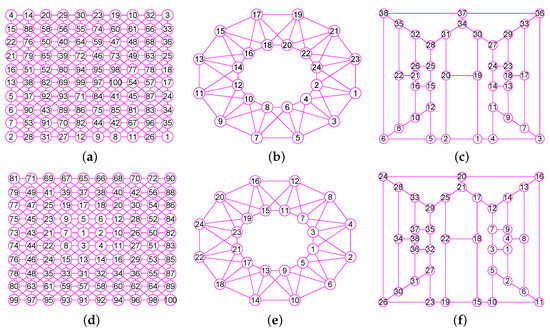

The graphs of three graphs, including the grid graph , , with , , . (a) A grid graph of 100 vertices and 180 edges; (b) The graph of ; (c) The graph of ; (d) The graph of .

Figure 8.

The graphs of two trees and . (a) A tree of 39 vertices and 38 edges; (b) The graph of ; (c) A tree of 42 vertices and 41 edges; (d) The graph of .

Figure 9.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) A graph of 22 vertices and 37 edges; (b) A graph of 53 vertices and 80 edges; (c) A graph of 49 vertices and 78 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 10.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The grid graph of 27 vertices and 54 edges; (b) The grid graph of 64 vertices and 144 edges; (c) A graph of 77 vertices and 196 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 11.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The king graph of 100 vertices and 342 edges; (b) The musical graph of 24 vertices and 60 edges; (c) The Barnette-Bosák-Lederberg graph of 38 vertices and 57 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 12.

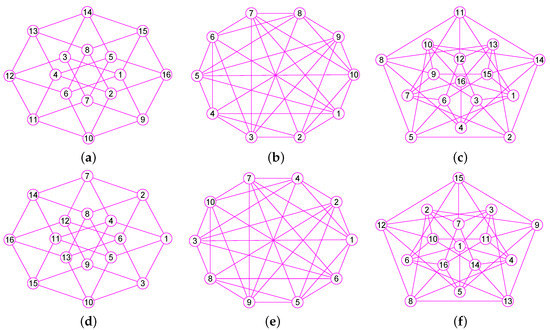

The graphs of three regular graphs , and . (a) The 4-hypercube graph of 16 vertices and 32 edges; (b) The triangular graph of 10 vertices and 30 edges; (c) The Clebsch graph of 16 vertices and 40 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 13.

The graphs of three unconnected graphs , and . (a) A disconnected graph with 12 nodes and 12 edges; (b) A disconnected graph that has four connected components and a total of 100 vertices and 160 edges; (c) A disconnected graph that has four connected components and a total of 100 vertices and 131 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

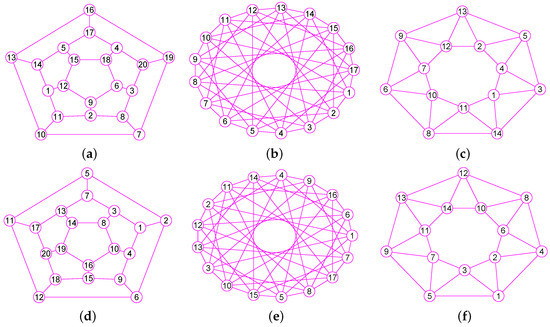

Figure 14.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) A Hamiltonian Graph of 20 vertices and 30 edges; (b) The 6-Andrásfai graph of 17 vertices and 51 edges; (c) The 7-antiprism graph of 14 vertices and 28 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 15.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The complete bipartite graph of 10 vertices and 25 edges; (b) The 12-crossed prism graph of 24 vertices and 36 edges; (c) The 6th order cube-connected cycle graph of 24 nodes and 36 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 16.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The Icosidodecahedral Graph with 30 nodes and 60 edges; (b) The truncated octahedron graph with 24 nodes and 36 edges; (c) The great rhombicuboctahedron graph of 48 nodes and 72 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 17.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The coxeter graph of 28 vertices and 42 edges; (b) The Nauru graph with 24 nodes and 36 edges; (c) The Dyck graph of 32 nodes and 48 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 18.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The Errera graph of 17 vertices and 45 edges; (b) The Folkman graph with 20 nodes and 40 edges; (c) A fullerene graph of 24 nodes and 36 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 19.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) A generalized quadrangle graph with 15 nodes and 45 edges; (b) A pentagonal icositetrahedral graph with 38 nodes and 60 edges; (c) A Shrikhande graph of 16 nodes and 48 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 20.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The Wiener-Araya graph of 42 vertices and 67 edges; (b) The Zamfirescu graph with 48 nodes and 76 edges; (c) The Faulkner-Younger graph of 42 nodes and 62 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 21.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) A triangle-replaced graph with 30 nodes and 45 edges; (b) The 4-dimensional Keller graph of 16 vertices and 46 edges; (c) The knight graph of 36 nodes and 80 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 22.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The Folkman graph of 20 vertices and 40 edges; (b) The 24-cell graph with 24 nodes and 96 edges; (c) The Thomassen graph of 34 nodes and 52 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

Figure 23.

The graphs of three graphs , and . (a) The projective plane graph of 26 vertices and 52 edges; (b) The Miyazaki graph with 40 nodes and 60 edges; (c) The Cubic Hypohamiltonian graph of 44 vertices and 75 edges; (d) The graph of ; (e) The graph of ; (f) The graph of .

5. Software Implementation

Utilizing the theory specified in the previous sections, we made a kit of software means called GraphLabel to calculate of graphs. Our experimental conditions included an Intel(R) Core(TM)2 Quad CPU Q6600 @2.40 GHz with 4.00 GB of RAM. The operating system was Microsoft Windows 8.1 Professional Edition. The graphics card was an NVIDIA GeForce 9800 GT. The display resolution was bits (RGB). The internal hard drive was 500 GB. The programming environment was Microsoft Visual C++ 2012.

The software utilized object-oriented technique to construct many related classes, including , , , , and so on. A complete explanation of the software functions is beyond the range of this paper. We will fully describe it in the other articles. All figures displayed in this article were created by employing our software system.

We chose a graph collection to check the correctness of our algorithms. We used our own software program to generate a large number of graphs randomly as the test cases, including Figure 7c,d, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10c. Besides, for enhancing the depth and breadth of experimentation, we also adopted many test cases from the online library [31] and library of benchmarks [32], including Figure 6, Figure 7a, Figure 10a,b, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23.

We applied our algorithms to as many classes of graphs as potential. These graphs presented here are only a small portion of the check graphs since the length of the paper is restricted. For comparing entirely, we offer both the initial and the resulting graph.

6. Summary and Future Work

In short, we get the following results: by Theorems 2–9, the paper has built a comparatively entire theoretical frame for computing the and graphs of graphs. Algorithms 1–4 are unique and can correctly determine graphs for many classes of graphs, including trees, grid graphs, wheel graphs, hypercube graphs, king graphs, triangular graphs and so on (see Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23). Algorithms 1–4 are also valid for detached undirected graphs. For every vertex in a graph G, the definition of the property enhances the accuracy of computing . By software evaluating, the accuracy of our algorithms is elementarily established. Our approach can be employed to excavate the frequent subgraph. Additionally, it proposes Conjecture 1.

Nevertheless, there are still many aspects we need to progress, including verifying the conjectures suggested by us, improving our software platform and employing more test cases to check our program. Specifically, we need to reinforce our algorithms so that they can determine the for more classes of graphs.

Currently, we are considering how to stretch our method to dig the frequent subgraphs and determine the of weighted graphs. We will present further research in other papers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., Y.G., J.S. and L.T.; Methodology, J.H.; Software, J.H.; Validation, J.H., Y.G., J.S. and L.T.; Writing—original draft, J.H.; and Writing—review and editing, J.H.

Funding

The work described in this paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 61702020); Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grant numbers 4172013); and Beijing Natural Science Foundation-Haidian Primitive Innovation Joint Fund (grant numbers L182007).

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank all anonymous reviewers for their inspiring and constructive comments which helped to improve the presentation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hao, J.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, L.; Sun, J. Using k-Mix-Neighborhood Subdigraphs to Compute Canonical Labelings of Digraphs. Entropy 2017, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Gong, Y.; Tan, L.; Duan, D. Apply Partition Tree to Compute Canonical Labelings of Graphs. Int. J. Grid Distrib. Comput. 2016, 9, 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, B. Computing Automorphisms and Canonical Labellings of Graphs Combinatorial Mathematics; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1978; Volume 686, pp. 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Piperno, A. Search space contraction in canonical labeling of graphs. arxiv 2008, arXiv:0804.4881. [Google Scholar]

- Junttila, T.; Kaski, P. Engineering an Efficient Canonical Labeling Tool for Large and Sparse Graphs. In Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop on Algorithm Engineering and Experiments and the Fourth Workshop on Analytic Algorithmics and Combinatorics, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6 January 2007; Siam: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Y.J.; Davida, G.I.; McCarthy, M.K. Optimum Featurs and Graph Isomorphism. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1974, SMC-4, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanciuc, O. Canonical Numbering and Constitutional Symmetry. In Handbook of Chemoinformatics; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Babai, L.; Luks, E.M. Canonical Labeling of Graphs. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Boston, MA, USA, 25–27 April 1983; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantschi, L.; Bolboaca, S.D. Conformational study of C-24 cyclic polyyne clusters. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2018, 118, e25614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiţa, D.M.; Jäntschi, L. Extending the Characteristic Polynomial for Characterization of C20 Fullerene Congeners. Mathematics 2017, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolboaca, S.; Jantschi, L. How good can the characteristic polynomial be for correlations? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, M.; Karypis, G. Finding Frequent Patterns in a Large Sparse Graph*. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2005, 11, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, M.; Karypis, G. An efficient algorithm for discovering frequent subgraphs. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2004, 16, 1038–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, J.; Wang, W.; Prins, J. Efficient mining of frequent subgraphs in the presence of isomorphism. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Melbourne, FL, USA, 22 November 2003; pp. 549–552. [Google Scholar]

- Kashani, Z.; Ahrabian, H.; Elahi, E.; Nowzari-Dalini, A.; Ansari, E.; Asadi, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Schreiber, F.; Masoudi-Nejad, A. Kavosh: A new algorithm for finding network motifs. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.R.; Zhang, W.J.; Li, Q. Some further development on the eigensystem approach for graph isomorphism detection. J. Frankl. Inst.-Eng. Appl. Math. 2005, 342, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvind, V.; Das, B.; Köbler, J. A Logspace Algorithm for Partial 2-Tree Canonization. In Computer Science-Theory and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5010, pp. 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babai, L.; Kucera, L. Canonical labelling of graphs in linear average time. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 29–31 October 1979; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnborg, S.; Proskurowski, A. Canonical Representations of Partial 2- and 3-Trees. In Proceedings of the 2nd Scandinavian Workshop on Algorithm Theory, Bergen, Norway, 11–14 July 1990; Lecture Notes in Computer Science 477. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990; pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, B. Practical Graph Isomorphism; Department of Computer Science, Vanderbilt University: Nashville, TN, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, B.D. Isomorph-Free Exhaustive Generation. J. Algorithms 1998, 26, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practical graph isomorphism, {II}. J. Symb. Comput. 2014, 60, 94–112. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Han, J. gSpan: Graph-based substructure pattern mining. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, ICDM 2003, Maebashi City, Japan, 9–12 December 2002; pp. 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T. The Complexity of McKay’s Canonical Labeling Algorithm; Citeseer: University Park, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tener, G.; Deo, N. Efficient isomorphism of miyazaki graphs. Algorithms 2008, 5, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Junttila, T.; Kaski, P. Conflict Propagation and Component Recursion for Canonical Labeling Theory and Practice of Algorithms in (Computer) Systems; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6595, pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- López-Presa, J.L.; Anta, A.F.; Chiroque, L.N. Conauto-2.0: Fast Isomorphism Testing and Automorphism Group Computation. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1108.1060. [Google Scholar]

- Katebi, H.; Sakallah, K.; Markov, I. Graph Symmetry Detection and Canonical Labeling: Differences and Synergies. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1208.6271. [Google Scholar]

- Habtemicael, S.; SenGupta, I. Pricing variance and volatility swaps for Barndorff-Nielsen and Shephard process driven financial markets. Int. J. Financ. Eng. 2016, 3, 1650027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.C.; SenGupta, I.; Bezdek, P. Numerical solutions for option pricing models including transaction costs and stochastic volatility. Acta Appl. Math. 2012, 118, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisstein, E.W. Simple Graphs–from Wolfram MathWorld; Wolfram Research: Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ALENEX 2007 Submission: Source Code, Benchmark Instances, and Summary Results. Available online: http://www.tcs.hut.fi/Software/benchmarks/ALENEX-2007/ (accessed on 30 June 2018).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).