Abstract

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) is a common autoimmune disease during childhood with a substantial genetic component. Individual genome-wide association studies (GWAS) often have limited power and are predominantly based on European-ancestry populations. To provide a more robust synthesis of genetic associations, we conducted a meta-analysis using summary-level GWAS data from three independent pediatric T1D studies obtained from the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog. Harmonized single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) shared across all datasets were analyzed using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects and random-effects models, with between-study heterogeneity assessed using Cochran’s Q test and the statistic. Of the 4,297,702 million common SNPs analyzed, 3524 reached genome-wide significance (), demonstrating strong and consistent associations with T1D risk. The most prominent signals clustered on chromosome 6, consistent with known immune-related loci, and included both risk-increasing and protective variants, in agreement with prior biological findings. Heterogeneity across studies was minimal, with values near for nearly all SNPs. These findings highlight robust and reproducible SNP-level associations with pediatric T1D, providing an updated foundation for functional follow-up and translational studies.

MSC:

62P10

1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks and destroys the insulin-producing pancreatic -cells, leading to insulin deficiency and lifelong dependence on exogenous insulin therapy [1]. It is the most common form of diabetes in children, accounting for approximately 80% of pediatric diabetes cases in the United States. With incidence rates steadily rising worldwide [1,2], T1D has become a significant pediatric public health concern. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis across 55 countries quantified pediatric T1D incidence from 2000 to 2022 and supports the conclusion that childhood T1D remains a growing global burden [3]. A separate systematic review and meta-analysis reported higher pediatric diabetes incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the pandemic, reinforcing evidence of recent acceleration in new-onset disease [4].

Type 1 diabetes also has a strong genetic component, with approximately half of the overall disease risk attributed to hereditary factors. Variants within the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region account for about 50% of this genetic predisposition [5]. In addition to HLA, several other loci—particularly those involved in immune regulation, such as INS, CTLA4, IL2RA, and PTPN22—have been implicated in T1D susceptibility [5]. While environmental triggers also contribute to disease onset, mapping these genetic risk loci is essential for deepening our understanding of T1D pathogenesis in children and improving early prediction.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have played a pivotal role in identifying genetic risk loci associated with T1D. Early studies uncovered over 60 non-HLA regions linked to the disease, many of which involve genes related to immune regulation [6]. Subsequent large-scale international consortia have expanded this number to more than 90 confirmed loci [5]. Notably, most of these variants are single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located in non-coding regions of the genome, suggesting they may influence gene regulation rather than directly altering protein-coding sequences.

Early meta-analytic efforts combining multiple independent case–control and family-based cohorts confirmed dozens of non-HLA risk regions and identified novel loci such as BACH2, PRKCQ, CTSH, and C1QTNF6, implicating pathways related to immune regulation and T-cell signaling (e.g., meta-analysis of three GWAS datasets; IL2-IL21, BACH2, PRKCQ, CTSH, C1QTNF6) [7]. Other GWAS meta-analyses in T1D demonstrated that pooling cohorts substantially increases locus discovery beyond single-study scans [8]. Similarly, a genome-wide meta-analysis combining six T1D cohorts identified additional associated loci, emphasizing the power gains achievable through meta-analytic designs [9]. In this study, three additional genome-wide significant signals near LMO7, EFR3B, and a region on 6q27 were uncovered, further enriching the catalog of T1D risk loci beyond those identified in individual GWAS.

Despite recent advancements in research, significant gaps remain in the literature of T1D. Most GWAS have largely focused on populations of European ancestry [10], raising concerns about how well the identified genetic loci apply to other ethnic groups. This focus may overlook risk alleles that are specific to certain populations or more prevalent in non-European groups. Additionally, many individual GWAS have modest sample sizes, particularly for T1D pediatric studies, limiting their statistical power to detect variants with small effect sizes [11]. These issues contribute to variability in findings across studies and highlight the urgent need for a comprehensive and integrative analyses of GWAS data in T1D. To address these challenges, we undertook a meta-analysis of GWAS data associated with T1D in children. By pooling results from multiple studies, a meta-analysis increases the effective sample size and thus boosts statistical power to detect risk variants that single cohorts might miss. This approach also enables validation of findings across different populations and can identify consistent associations that hold true beyond any one study or ancestry group. Here, we integrate findings from recent GWAS to provide an up-to-date and a more robust set of T1D susceptibility loci that are reproducible across independent cohorts, mostly of European ancestry. In doing so, this meta-analysis aims to identify robust SNP associations with pediatric T1D, bridging gaps in existing literature and improving our understanding of the disease’s genetic architecture in children.

This study utilized GWAS summary statistics obtained from the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/ (accessed on 10 April 2025)). Specifically, we extracted datasets from three independent studies that investigated genetic associations with T1D [10,12,13]. The summary-level datasets include key variables such as SNP identifiers, chromosome number, base pair location, effect and other alleles, beta coefficients, standard errors, p-values, and effect allele frequencies. All three datasets share a common phenotype (T1D) and contain overlapping SNPs, allowing for harmonization across studies and overall SNPs-combined-effect associations with T1D across diverse populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Selection

Summary-level GWAS data, defined as SNP-level association statistics for each variant, included effect sizes (), standard errors, p-values, effect alleles, non-effect alleles, chromosomal positions, base-pair locations, and effect allele frequencies, and were obtained from the NHGRI–EBI GWAS Catalog. No individual-level genotype data were used in this study. The approximately 4.3 million SNPs reported represent variants shared across the three studies after harmonization and quality control, rather than raw genotype data.

SNPs with extremely low p-values (<5 × ) were excluded to ensure data integrity and reduce the risk of including potential artifacts arising from allele mismatches, strand ambiguity, or inflated test statistics due to genotyping or imputation errors, which have been reported to cause false-positive associations in GWAS meta-analyses and distort the results of the meta-analysis [14]. While this threshold may exclude some true strong associations particularly within the HLA region known for dense LD and complex genetic architecture, this conservative filter was applied to enhance data reliability. To support this decision, previous studies have emphasized the importance of excluding SNPs with unreliable or unstable summary statistics to maintain the robustness of the findings and ensure consistency across datasets [15]. While we recognize the potential significance of these variants, especially in critical regions like the HLA, they were excluded to safeguard the overall quality and validity of the meta-analysis.

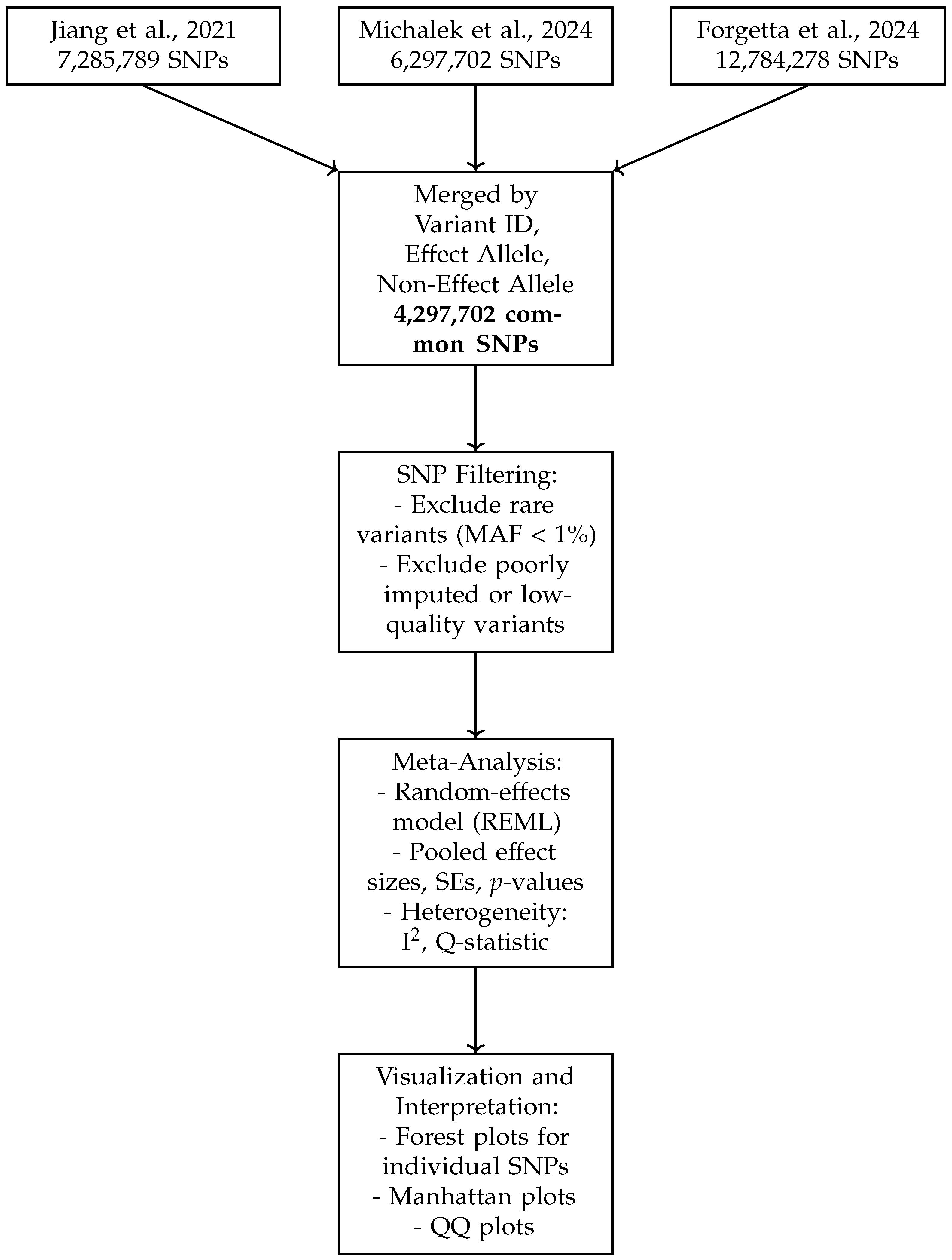

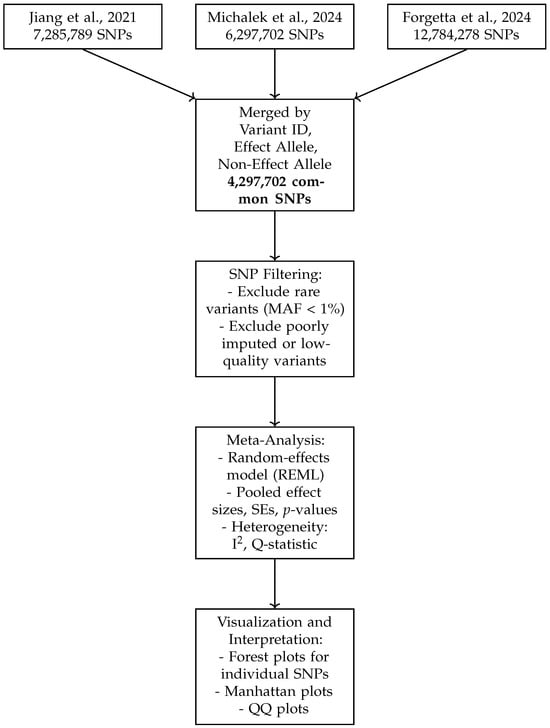

Figure 1 presents a schematic overview of the data harmonization and meta-analysis workflow. It illustrates the integration of three GWAS datasets, the harmonization steps including allele alignment and quality control, SNP filtering criteria such as minor allele frequency thresholds, and the application of random-effects meta-analysis models. This pipeline ensures robust merging of SNPs by variant ID, effect allele, and non-effect allele, resulting in a high-confidence set of 4,297,702 common SNPs for downstream analysis and visualization. The schematic highlights the systematic approach taken to maximize data consistency, reduce bias, and enhance the interpretability of meta-analytic results.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the data harmonization and meta-analysis workflow. The top boxes represent the source GWAS datasets. SNPs were merged across studies based on variant ID and allele matching. Filtering steps excluded rare or low-quality variants. Meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model (REML), and the results were visualized using forest plots, Manhattan plots, and QQ plots [10,12,13].

The ancestry composition of each GWAS dataset was approximated based on cohort descriptions in the original publications (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Population ancestry and generalizability.

Cohort characteristics and recruitment procedures were carefully reviewed for each GWAS to assess the potential for participant overlap. To minimize bias, we conducted our analysis using summary-level GWAS data rather than individual-level genotypes. Study-specific recruitment strategies were cross-referenced to ensure that the included cohorts represented independent samples. Together, these steps were taken to reduce the risk of overlap-related bias and to maintain the accuracy of pooled effect estimates.

2.2. Meta-Analysis Methods

Meta-analysis was performed using both fixed-effects and random-effects inverse-variance weighted models to estimate pooled effect sizes for each unique SNP.

Fixed-effects models assumed a common true effect size across all studies, whereas random-effects models allowed for between-study heterogeneity. A random-effects meta-analysis model assumes that the true SNP effect sizes may vary across studies, with the observed effects modeled as , where is the within-study error. Between-study variance () was estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method. REML is considered robust because it provides unbiased estimates of variance components even in small samples and avoids underestimation that can occur with standard maximum likelihood [16,17]. Confidence intervals for and its standard deviation () were derived using the Q-profile method, which inverts the Q-statistic distribution to produce accurate bounds around the heterogeneity estimates.

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q test, with significance indicating evidence of heterogeneity, and the statistic, which quantifies the percentage of total variability in effect estimates attributable to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. was calculated from the Q statistic and its degrees of freedom.

For improved statistical inference in the random-effects framework, the Hartung–Knapp adjustment was applied, using a t-distribution with two degrees of freedom, to generate more reliable confidence intervals, particularly under small-sample conditions. SNPs reaching genome-wide significance () were reported. Visualization of results included Manhattan plots to display genome-wide association signals and forest plots to illustrate study-specific and pooled effect estimates.

Genomic control correction and inflation factor assessment () were applied within each original GWAS dataset prior to the release of summary statistics. To ensure no residual inflation, we inspected QQ plots of the meta-analyzed results and found no evidence warranting further genomic control correction during meta-analysis. To reduce potential bias and heterogeneity, our meta-analysis focused on SNPs common to all three datasets. While ref. [13] included rare variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) , refs. [10,12] excluded variants with MAF . Consequently, the final SNP set predominantly comprised variants with MAF , improving statistical power and minimizing false positives associated with rare variants. This harmonized SNP selection contributed to more consistent and robust effect estimates across studies.

Section 2.2.1 and Section 2.2.2 describe the statistical methods used and their implementation in R software (Version 4.5.2) [18].

2.2.1. Inverse-Variance Weighting Methods

In fixed-effect meta-analysis, the weight for each study i is

where is the sampling variance of the effect estimate , and denotes the standard error. The combined fixed effect estimate for k number of studies is:

With standard error,

The test statistic is given by:

Cochran’s Q statistic tests whether the observed effects across studies are more variable than expected by chance and was calculated as follows:

The statistic measures the proportion of observed variation that is due to true between-study heterogeneity.

2.2.2. Random-Effects Meta-Analysis Models

For random-effects models,

where is the estimated between-study variance (via REML), and is the within-study variance. We define

and is the variance of the study-specific inverse-variance weights.

represents a scaling term derived from the distribution of inverse-variance weights across studies and is used in the moment-based estimation of between-study heterogeneity. This quantity depends on the number of studies , the mean of the study weights , and their variance (), and serves as a normalization factor in the heterogeneity calculation.

if , else,

where denotes the between-study variance of the true SNP effect sizes, estimated from Cochran’s Q statistic. When , is set to zero, indicating no detectable heterogeneity beyond sampling error; otherwise, quantifies excess variability attributable to genuine differences in SNP effects across studies. This parameter is then incorporated into the construction of adjusted inverse-variance weights used to compute the pooled random-effects estimate.

That is,

2.3. Annotation of SNPs to Nearest Genes

SNPs that reached genome-wide significance () in the meta-analysis were annotated to their nearest genes using the R Bioconductor package biomaRt [19,20] with the Ensembl GRCh38 gene build function. For each SNP, the nearest gene was defined as the gene with the minimal distance between the SNP genomic position and the gene’s start or end positions. SNPs without a nearby gene were excluded from annotation.

For the top 50 significant SNPs with annotated nearest genes, Table 2 was generated including SNP ID, chromosome, base pair location, effect allele, non-effect allele (other), meta-analysis beta coefficients, standard errors, p-values, heterogeneity metric (), nearest gene symbol, and gene biotype. Effect sizes and standard errors were rounded to three decimal places, and p-values were presented in scientific notation.

Table 2.

Top 50 genome-wide significant SNPs associated with T1D and their nearest genes. Beta and SE are from the meta-analysis. p-values are in scientific notation.

A list of top 100 significant GWAS SNPs and their associated variables is provided in Supplementary Table S1 (see Supplementary File).

Data cleaning and management were performed using SAS/STAT software version 9.4 [21] and Stata 19 [22]. Meta-analyses were conducted in the R statistical environment (version 4.5.2) [18] using the meta [23] and metafor [17] packages. All analyses employed random-effects models (REML) to account for between-study heterogeneity. Accordingly, reported effect sizes, p-values, and the forest and Manhattan plots reflect random-effects estimates. For the Manhattan plots, the (p-values) were calculated from pooled effect sizes and standard errors obtained via metafor::rma(), and forest plots for individual SNPs were generated from the random-effects estimates using either metafor::rma() or meta::metagen(random = TRUE).

3. Results

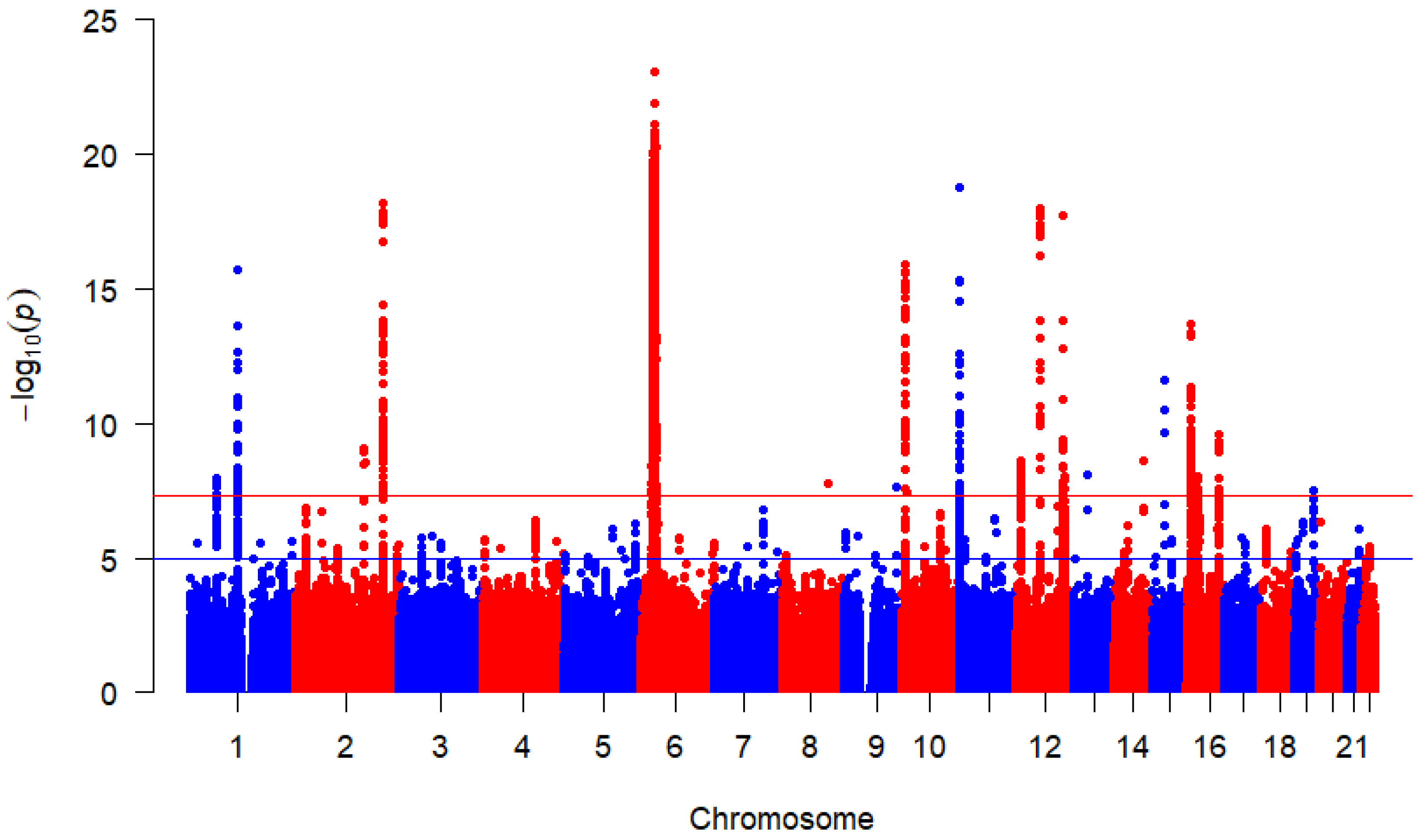

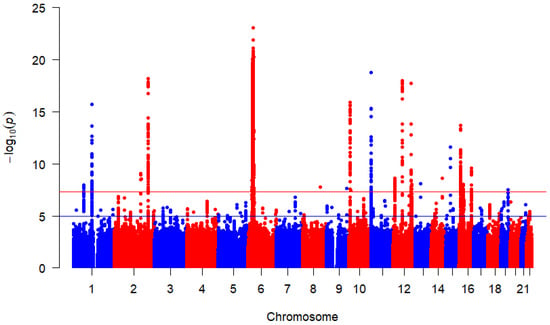

Based on 4,297,702 million SNPs from each of the three studies, the combined overall effects are displayed by Figure 2 using Manhattan plot. This study found 3524 SNPs above the redline that met the genome-wide significance threshold with p-value indicating that they are strongly associated with the T1D outcome after correcting for multiple testing. This figure highlights multiple peaks surpassing the genome-wide significance threshold. Chromosome position 6 has more significant SNPs indicated by the dense clustering higher points above the threshold, suggesting robust associations between these SNPs and T1D. These findings provide valuable insights and warrant further investigation into the identified loci.

Figure 2.

Manhattan plot for SNP associations with T1D. p-values were derived from random-effects meta-analysis using REML. The red horizontal line indicates the genome-wide significance threshold () and the blue horizontal line represents a suggesting significance threshold ().

In the Manhattan plot (Figure 2), the red horizontal line represents the widely accepted genome-wide significance threshold of above which SNPs are considered significantly associated with T1D [24,25], correcting for multiple hypothesis testing across the genome. The blue horizontal line indicates a suggestive association threshold of [26,27], highlighting SNPs that may warrant further investigation despite not reaching genome-wide significance.

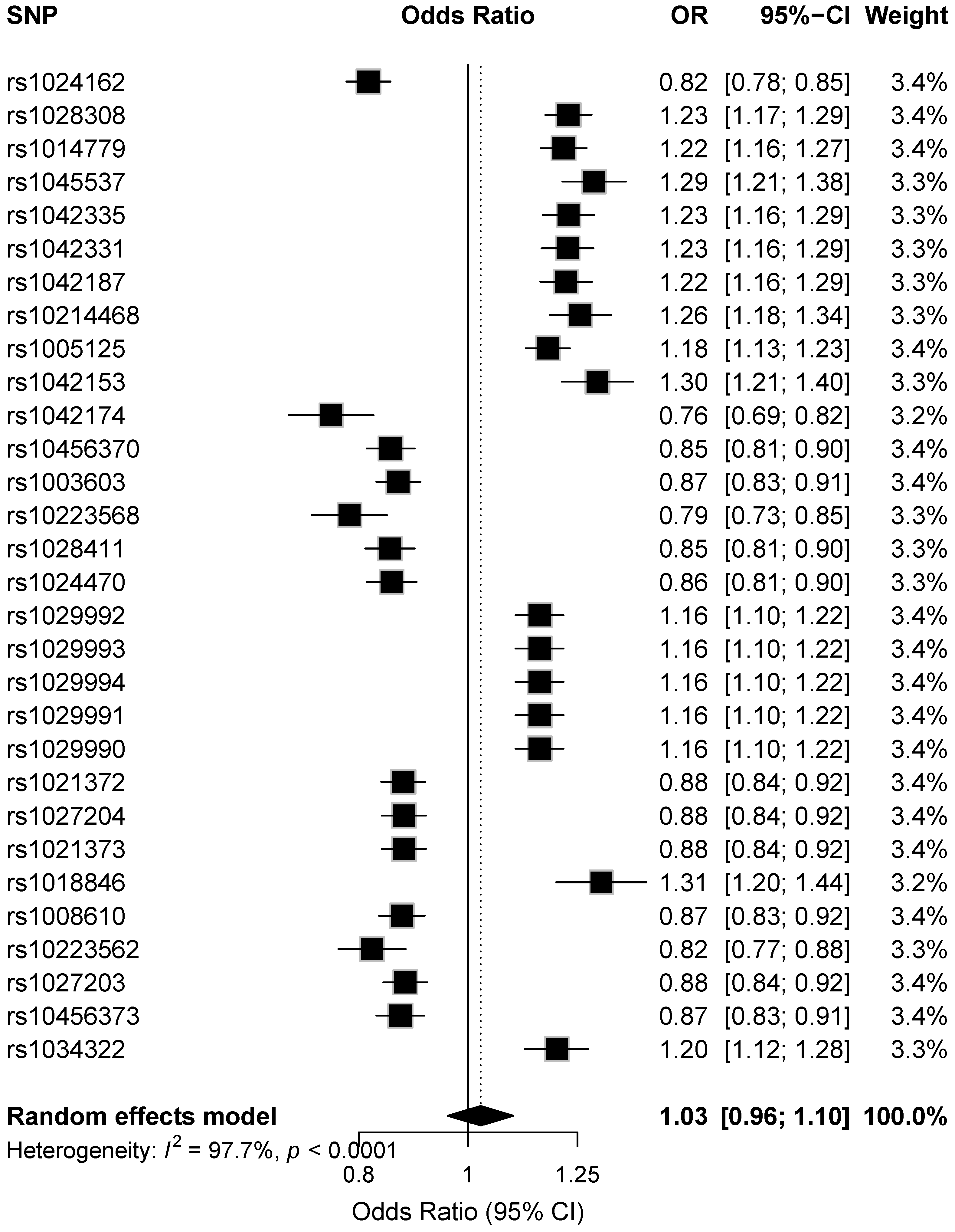

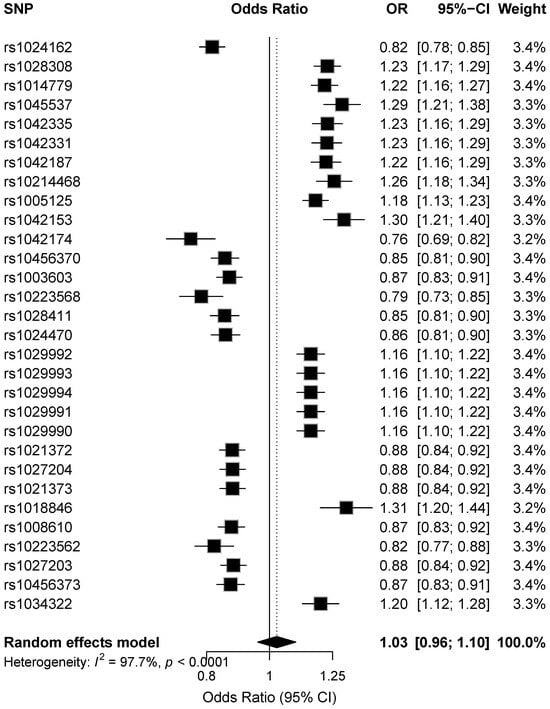

Figure 3 shows forest plots for the top 30 GWAS SNPs, displaying the meta-analysis effect estimates as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) per effect allele. Variants with OR < 1 are associated with reduced risk, whereas variants with OR > 1 are associated with increased risk of type 1 diabetes.

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing random-effects odds ratios (95% CI) for the top 30 genome-wide significant SNPs, sorted by meta-analysis p-value.

Results presented in Table 2 and the external Supplementary Table S1 (see Supplementary File) include nearest-gene annotations, HGNC gene symbols, Ensembl gene identifiers, gene coordinates, distances from each SNP, and gene biotypes. These annotations provide insight into potential functional mechanisms underlying the observed genetic associations with T1D and may inform the design of future functional studies.

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we identified 3524 SNPs significantly associated with type 1 diabetes (T1D) at the genome-wide threshold (), with consistent effect directions in both fixed- and random-effects models. Low values and nonsignificant Q-statistic p-values indicate minimal observed heterogeneity, reinforcing the robustness of the pooled effect estimates.

The identification of 3524 genome-wide significant SNPs provides a detailed view of the genetic architecture underlying pediatric T1D susceptibility. The predominance of statistically significant associations observed in this meta-analysis is consistent with previous large-scale GWAS meta-analyses of T1D, which have reported extensive association signals driven largely by linkage disequilibrium within established risk loci, particularly in the HLA region on chromosome 6. Accordingly, the genome-wide significant SNPs identified here may reflect correlated variants within known and previously reported loci, as well as additional signals emerging from increased SNP density and harmonization across studies.

These findings can enhance polygenic risk score (PRS) models, potentially enabling early identification of high-risk children and informing personalized prevention strategies. Additionally, many of the associated loci are involved in immune regulation, offering potential targets for therapeutic intervention and drug development aimed at modulating autoimmune processes. Translating these genetic insights into clinical practice will require integration with environmental, epigenetic, and clinical data, highlighting the importance of multi-omics approaches and longitudinal studies to capture the dynamic interplay of factors influencing disease onset and progression.

The direction of effects, encompassing both risk-increasing and protective variants, aligns with prior GWAS and meta-analyses [8,11,27], particularly within the HLA region on chromosome 6, which harbors alleles conferring either susceptibility or protection. Additional associations were observed in well-established non-HLA loci, including INS, PTPN22, and IL2RA, highlighting the immunogenetic basis of T1D and identifying candidates for future functional studies.

Many identified variants reside in non-coding regions, underscoring the importance of functional follow-up to elucidate biological mechanisms. Integrative approaches combining GWAS results with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL), chromatin accessibility, and epigenomic annotations can prioritize causal variants and target genes [28,29]. Experimental strategies, including CRISPR-based genome editing and high-throughput functional assays, provide opportunities to validate regulatory variants and uncover mechanistic pathways [30]. Such integrative multi-omics analyses will be critical for translating statistical associations into biological insights and therapeutic targets.

A key limitation of this study is its reliance on summary-level GWAS data. Without access to individual-level genotypes, we were unable to adjust for covariates, explore gene–environment interactions, perform stratified analyses, or conduct comprehensive genotype imputation across cohorts. Differences in study design, genotyping platforms, phenotyping criteria, and quality control thresholds may introduce residual heterogeneity. While random-effects models account for some between-study variation, minor participant overlap across studies cannot be completely excluded, although the expected impact on effect estimates is minimal.

Another limitation of this study is the limited ancestral diversity of the included cohorts. Two of the three GWAS were predominantly of European ancestry, while the third included only modest representation from Hispanic and African populations. As a result, variants that are common in African, Hispanic, or Asian populations were largely underrepresented, which may have led to missed associations or biased effect estimates. This underscores the need for larger, multi-ancestry studies to improve the generalizability of findings and enhance the accuracy of polygenic risk scores across diverse populations.

Mapping the top SNPs to their nearest genes provided insights into potential biological mechanisms, particularly genes involved in immune regulation and pancreatic function. These annotations can guide future functional studies and inform refinement of polygenic risk prediction models.

Future research should focus on integrating GWAS with multi-omics and functional data, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics, to provide mechanistic insights. Resources such as GTEx, ENCODE, and single-cell RNA-seq datasets from pancreatic islets and immune cells can help map disease-associated SNPs to regulatory elements and target genes. Functional validation through genome editing or model systems will further bridge statistical associations and biological mechanisms, ultimately informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies for pediatric T1D.

5. Conclusions

This GWAS meta-analysis identified robust and highly reproducible genetic associations with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Of the 4,297,702 SNPs shared across studies, 3524 reached genome-wide significance (), implicating both established and potentially novel loci in T1D susceptibility. The absence of detectable between-study heterogeneity (, non-significant Cochran’s Q) indicates remarkably consistent effect estimates across cohorts, reinforcing the reliability of these associations and their relevance to the genetic architecture of T1D.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math14030514/s1, Table S1: Genome-wide significant SNPs and associated gene annotations from the top 100 GWAS loci.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.K.M.; methodology, L.K.M., V.I.A. and A.J.; software, L.K.M.; validation, L.K.M., V.I.A. and A.J.; formal analysis, L.K.M.; investigation, A.J. and V.I.A.; resources, L.K.M., V.I.A. and A.J.; data curation, L.K.M., V.I.A. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, V.I.A. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, L.K.M., V.I.A. and A.J.; visualization, L.K.M., V.I.A. and A.J.; supervision, L.K.M.; project administration, L.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

GWAS summary data is available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Redondo, M.J.; Steck, A.K.; Pugliese, A. Genetics of Type 1 Diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 19, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasi, R.; Ravi, K.S. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Pediatric Age Group. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormazábal-Aguayo, I.; Ezzatvar, Y.; Huerta-Uribe, N.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Izquierdo, M.; García-Hermoso, A. Incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents under 20 years of age across 55 countries from 2000 to 2022: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, D.; Empringham, J.; Pechlivanoglou, P.; Uleryk, E.M.; Cohen, E.; Shulman, R. Incidence of diabetes in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2321281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.J.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Gaulton, K.J. Genetics of Type 1 Diabetes. In Diabetes in America; Lawrence, J.M., Casagrande, S.S., Herman, W.H., Wexler, D.J., Cefalu, W.T., Eds.; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaga, D.M.; Vickers, M.H.; Jefferies, C.; Perry, J.K.; O’Sullivan, J.M. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus-Associated Genetic Variants Contribute to Overlapping Immune Regulatory Networks. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.D.; Smyth, D.J.; Smiles, A.M.; Plagnol, V.; Walker, N.M.; Allen, J.E.; Downes, K.; Barrett, J.C.; Healy, B.C.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association study data identifies additional type 1 diabetes risk loci. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1399–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.C.; Clayton, D.G.; Concannon, P.; Akolkar, B.; Cooper, J.D.; Erlich, H.A.; Julier, C.; Morahan, G.; Nerup, J.; Nierras, C.; et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, J.P.; Qu, H.Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Sleiman, P.M.; Kim, C.E.; Mentch, F.D.; Qiu, H.; Glessner, J.T.; Thomas, K.A.; et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of six type 1 diabetes cohorts identifies multiple associated loci. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalek, D.A.; Tern, C.; Zhou, W.; Robertson, C.C.; Farber, E.; Campolieto, P.; Chen, W.M.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Rich, S.S. A Multi-Ancestry Genome-Wide Association Study in Type 1 Diabetes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2024, 33, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inshaw, J.R.J.; Sidore, C.; Cucca, F.; Stefana, M.I.; Crouch, D.J.M.; McCarthy, M.I.; Mahajan, A.; Todd, J.A. Analysis of Overlapping Genetic Association in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Fang, H.; Yang, J. A Generalized Linear Mixed Model Association Tool for Biobank-Scale Data. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgetta, V.; Manousaki, D.; Istomine, R.; Ross, S.; Tessier, M.C.; Marchand, L.; Li, M.; Qu, H.Q.; Bradfield, J.P.; Grant, S.F.A.; et al. Rare Genetic Variants of Large Effect Influence Risk of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2020, 69, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, E.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Meta-analysis methods for genome-wide association studies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, T.W.; Day, F.R.; Croteau-Chonka, D.C.; Wood, A.R.; Locke, A.E.; Mägi, R.; Ferreira, T.; Fall, T.; Graff, M.; Justice, A.E.; et al. Quality control and conduct of genome-wide association meta-analyses. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1192–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, H.D.; Thompson, R. Recovery of inter-block information when block sizes are unequal. Biometrika 1971, 58, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Durinck, S.; Spellman, P.T.; Birney, E.; Huber, W. Mapping identifiers for the integration of genomic datasets with the R/Bioconductor package biomaRt. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durinck, S.; Moreau, Y.; Kasprzyk, A.; Davis, S.; De Moor, B.; Brazma, A.; Huber, W. BioMart and Bioconductor: A powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3439–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 15.3 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 19; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2019, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 2007, 447, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, I.; Yelensky, R.; Altshuler, D.; Daly, M.J. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet. Epidemiol. 2008, 32, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, E.S.; Kruglyak, L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: Guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat. Genet. 1995, 11, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Chen, W.M.; Burren, O.; Cooper, N.J.; Quinlan, A.R.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Farber, E.; Bonnie, J.K.; Szpak, M.; Schofield, E.; et al. Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeira, A.N.; Bonazzola, R.; Gamazon, E.R.; Liang, Y.; Park, Y.; Kim-Hellmuth, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, D.; Vujkovic, M.; Linde, L.; et al. Exploiting the GTEx resources to decipher the mechanisms at GWAS loci. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, H.; Batzoglou, S.; Xie, R.; Lloyd-Jones, L.R.; Marioni, R.E.; Martin, N.G.; Montgomery, G.W.; et al. Integrative analysis of omics summary data reveals putative mechanisms underlying complex traits. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Bauer, D.E. Editing GWAS: Experimental approaches to dissect and exploit disease-associated genetic variation. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.