Abstract

This study investigates the nonlinear dynamics that emerge from the interactions between cancer cells and immune cells within a predator–prey model, wherein cancer cell growth obeys the Gompertz law. A bifurcation analysis allows for the identification of states of dormancy, uncontrolled growth, and multistability with and without chemotherapy. In the absence of chemotherapy, a Gompertz model predicts bistability with low (dormant) and high (active) tumor levels. However, unlike models based on the logistic equation, it shows that a stable tumor-free solution does not exist, consistent with the medical understanding about the risk of remaining disease even with successful treatment. Under chemotherapy, the model demonstrates highly complex dynamics with up to four coexisting stable steady states, stable tumor levels, and chemotherapy-induced oscillations. Parameter continuation studies show that the potency of immune recruitment, rate of cell inactivation, and drug saturation are essential in characterizing transitions among these dynamical regions. The analysis indicates that the choice of growth rate plays a significant role in determining the physiological implications for therapy, suggesting a cure for a model with a logistic growth rate, but merely tumor control for a Gompertzian scenario. Moreover, these results provide insights into optimal chemotherapy dosage to prevent problems associated with bistability and to capitalize on stable dormancy.

Keywords:

bifurcation; cancer; chemotherapy; Gompertz model; oscillations; tumor-immune cells; mathematical oncology MSC:

92D25; 92-10; 37N25; 37G35; 65P30

1. Introduction

Cancer still remains a serious global health issue. According to the World Health Organization, there were 10 million deaths and 20 million new cancer cases in 2022 alone [1]. Despite the advances made in early diagnosis and treatment, there remain serious challenges associated with many aspects such as drug resistance and metastases [2,3].

Biological and mathematical complexities are brought together in mathematical oncology as an interdisciplinary field that allows for predictions about tumor growth, response, and the optimization of therapies [4,5]. By combining experimental knowledge with dynamical systems theory, mathematical models can offer understanding about processes that are difficult to analyze directly, like the intricate nonlinear interactions between tumor and immune systems [6,7].

Among various modeling approaches, predator–prey models have been successful at capturing tumor-immune interactions, where tumor cells (prey) grow and are attacked by immune effector cells (predators) [8,9,10]. The pioneering work of Kuznetsov et al. [8] showed that simple two-dimensional models could simulate various biologically observable phenomena, like dormancy and escape. Kirschner and Panetta [9] used nonlinear effector–tumor interaction models and numerical continuation/bifurcation tools to map how equilibria and transitions changed with key parameters. The authors demonstrated how saturating interactions and treatment inputs yielded turning points and Hopf/limit-cycle behavior in an extended model. Subsequent models have included more intricate immune responses [10], more combination therapies [11,12] and compartmentalized responses [13].

A common trait in these analyses is the utilization of logistic growth to describe tumor proliferation, a choice that is often driven by mathematical simplicity rather than empirical evidence.

1.1. Gompertz Growth as a Natural Baseline Model

The choice of tumor growth kinetics is an important modeling decision that significantly affects system dynamics and treatment outcomes. While logistic growth is often favored for its simplicity [8,11], increasing evidence shows that the Gompertz model provides better fits to tumor growth data across various cancer types [14,15]. Comparisons have revealed that Gompertz kinetics more accurately reflect the typical slowdown of tumor growth as the tumor gets larger. This phenomenon has been observed in both lab experiments and clinical studies [16]. Recently, Laleh et al. [17] conducted a thorough evaluation that compared multiple growth models using large human datasets. They found that the Gompertz model struck the best balance between fitting accuracy and parameter simplicity. However, the dynamic effects of using Gompertz growth in tumor-immune competition models have not been thoroughly investigated.

1.2. Recent Advances and Remaining Gaps

Recent modeling attempts have greatly increased the number of tumor-immune frameworks in various aspects (e.g., immune suppression, therapy coupling, and functional responses), revealing richer dynamics than early formulations [6,7]. López et al. [11], for instance, included the effects of chemotherapy and pointed out the regions of bifurcation caused by treatment, which have implications for therapy. Bashkirtseva et al. [12] built on this by taking up the study of combined chemo-radiotherapy and using the analysis of noise-induced transitions as a tool to study the process of shifting from one stable state to another. Fractional-order models are also under consideration for being able to describe memory effects in biological systems [18], but their use in the case of Gompertz-based tumor-immune systems is still limited. However, even after all these advancements, the following three gaps in the literature remain:

- A complete bifurcation analysis (including local and global bifurcations) of tumor-immune systems based on Gompertz growth has not been done, even though it is considered optimal by some empirical studies;

- A comparison of how Gompertz versus logistic growth laws reshape multistability and oscillatory regimes under the same mechanistic assumptions;

- A characterization of how chemotherapy-induced immune suppression can reorganize bifurcation structure and generate clinically relevant transitions such as intermediate stable states and treatment-induced oscillations.

1.3. Existing Gompertz-Based Tumor-Immune Models

While our work focuses on a comprehensive bifurcation-based characterization, several studies have previously incorporated Gompertz tumor growth in tumor-immune models, each emphasizing different mechanisms and analysis goals. Early Gompertz-based formulations explored tumor-immune coexistence and basic stability features [19]. Subsequent extensions added additional immune components or treatment terms and reported more complex dynamical behaviors, including multistability and oscillations [12,18,20,21]. Optimal control and therapy design questions have also been studied in related settings [22]. More recently, Kamran et al. [23] compared logistic, exponential, and Gompertz growth laws under chemotherapy, highlighting how the growth kinetics can qualitatively change stability predictions and immune depletion under treatment. Complementing mechanistic ODE studies, Gompertz kinetics are also increasingly used to quantify tumor growth inhibition in longitudinal immunotherapy data; see, e.g., the mixed-effects Gompertz analyses of Olarte et al. [24]. Nevertheless, a unified picture of the full bifurcation structure—and how it is reorganized by chemotherapy-induced immune suppression—is still lacking, motivating the present work.

1.4. Study Objectives and Contributions

The present study addresses the gaps above by analyzing a tumor-immune interaction model with Gompertz tumor growth, both without and with chemotherapy. Specifically, we aim to:

- Characterize the full bifurcation structure of the Gompertz-based model in the absence and presence of chemotherapy;

- Provide a comparison between Gompertz and logistic growth laws, highlighting implications for therapeutic strategy;

- Identify and interpret dynamical phenomena such as intermediate stable states, multistability windows, and treatment-induced oscillations;

- Map parameter sensitivities in a way that supports mechanistic interpretation and suggests directions for individualized treatment.

1.5. Paper Organization

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the model and its biological interpretation. Section 3 analyzes the baseline (no-chemotherapy) dynamics and bifurcations. Section 4 investigates chemotherapy effects, including immune suppression and the resulting reorganization of the bifurcation structure. Section 5 summarizes the main biological and clinical implications.

2. The Mathematical Model

The model builds upon the established predator–prey framework for tumor-immune interactions [8,12] but incorporates Gompertz kinetics for tumor growth. The system consists of two populations: immune effector cells E (predators) and tumor cells T (prey). The governing equations are given by Equations (1) and (2):

Here, E (cell) and T (cell) represent the populations of immune cells and tumor cells, respectively. The parameter s (cells/day) denotes the constant influx rate of immune cells from primary organs, while d (1/day) represents their natural death rate. The term models the inactivation of effector cells upon interaction with tumor cells at rate m (1/(cell.day)). Immune system stimulation by tumor antigens follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics, represented by , where p (1/day) is the maximum recruitment rate and g (cells) is the half-saturation constant. Tumor cell elimination by immune effectors occurs at rate n (1/(cell.day)) through the term .

Equation (2) describes tumor cell dynamics using the Gompertz growth model, where (1/day) represents the initial exponential growth rate and (1/day) characterizes the growth deceleration as the tumor approaches its carrying capacity. The logarithmic term captures the density-dependent slowing of tumor proliferation, a key feature distinguishing Gompertz from logistic growth. Chemotherapy effects are modeled by the term , where v (cells/day) represents the drug dose intensity and h (1/cell) is a saturation constant accounting for decreased drug efficacy at high tumor burdens [25].

Dimensionless variables are introduced as follows:

where and are reference concentrations. The resulting dimensionless system (with bars omitted for clarity) is given by Equations (3) and (4):

In this work, the nondimensionalization is systematic in execution, as time is rescaled using the immune–tumor interaction rate so that key model terms become order one. On the other hand, the specific characteristic population sizes are taken as fixed reference values

i.e., a representative magnitude commonly used for tumor/immune cell, and therefore, the magnitudes of the resulting dimensionless parameters are based on conventional modeling considerations rather than being uniquely “derived” from a particular equilibrium or asymptotic balance of the model.

Parameter values (Table 1) are selected from the established literature [8,10,11] to ensure biological relevance and facilitate comparison with previous studies.

Table 1.

Baseline parameter set and dimensionless values used in simulations and continuation unless otherwise stated. Nondimensionalization uses cells and time scaling .

3. Bifurcation Analysis Without Chemotherapy

We commence by analyzing the system devoid of chemotherapy () to establish the baseline dynamics. The inactivation rate parameter m is designated as the principal bifurcation parameter, as it represents the immune system’s exposure to tumor-induced suppression—a crucial factor in the advancement of cancer [26]. All bifurcation analyses were executed with the aid of MatCont [27]. MatCont (7p6) is a MATLAB (R2024b) package for numerical continuation and bifurcation analysis of dynamical systems (mainly ODEs). It tracks equilibria and periodic orbits as parameters vary using predictor–corrector (often pseudo-arclength) methods, detects stability changes and bifurcations (e.g., fold, Hopf, period-doubling), and can continue new branches, including unstable solutions that time simulations often miss. MatCont also computes normal-form coefficients (e.g., the first Lyapunov coefficient) that can be used to classify Hopf bifurcations as supercritical or subcritical.

3.1. Dynamical Regimes and Comparison with Logistic Growth

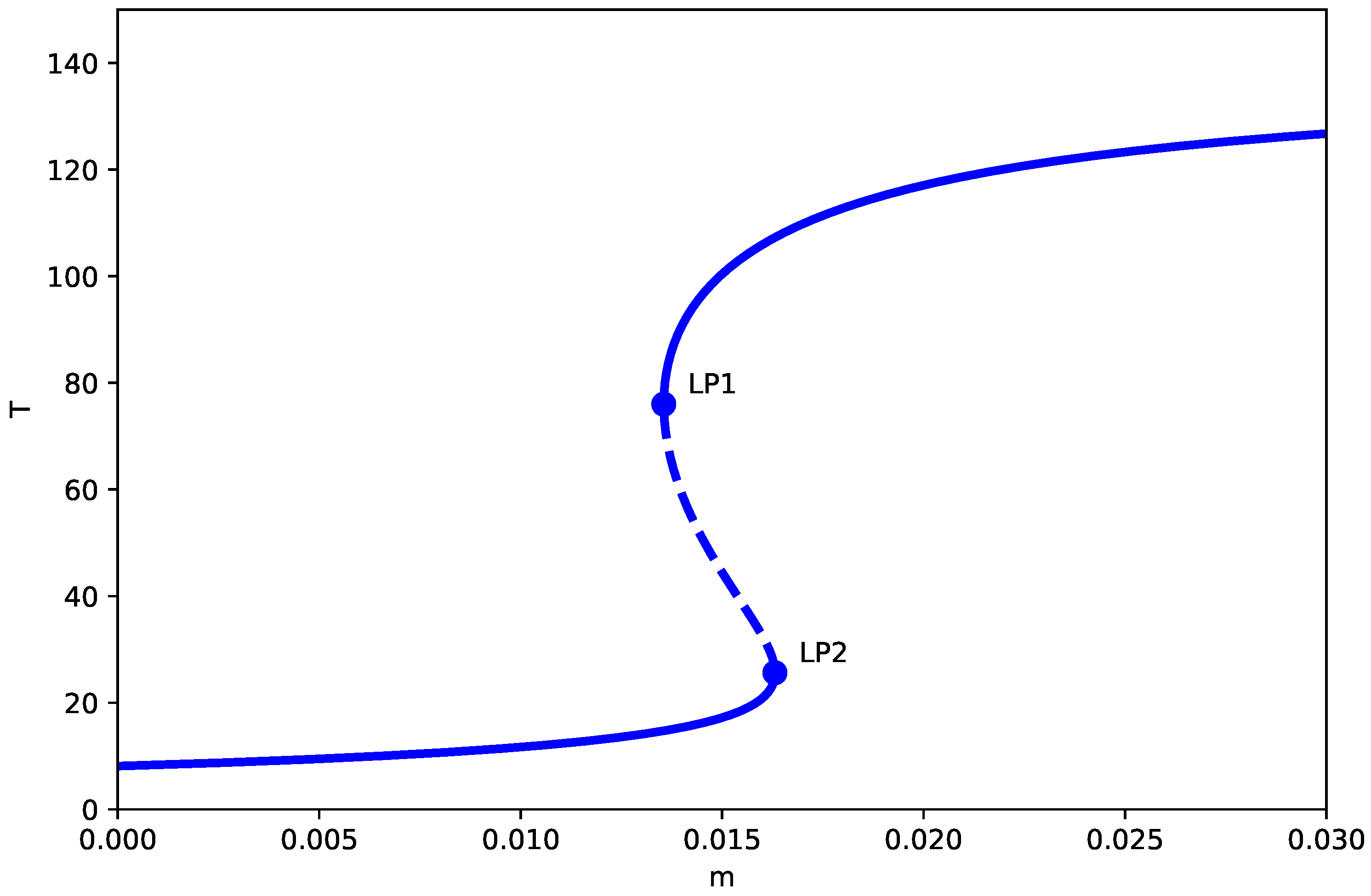

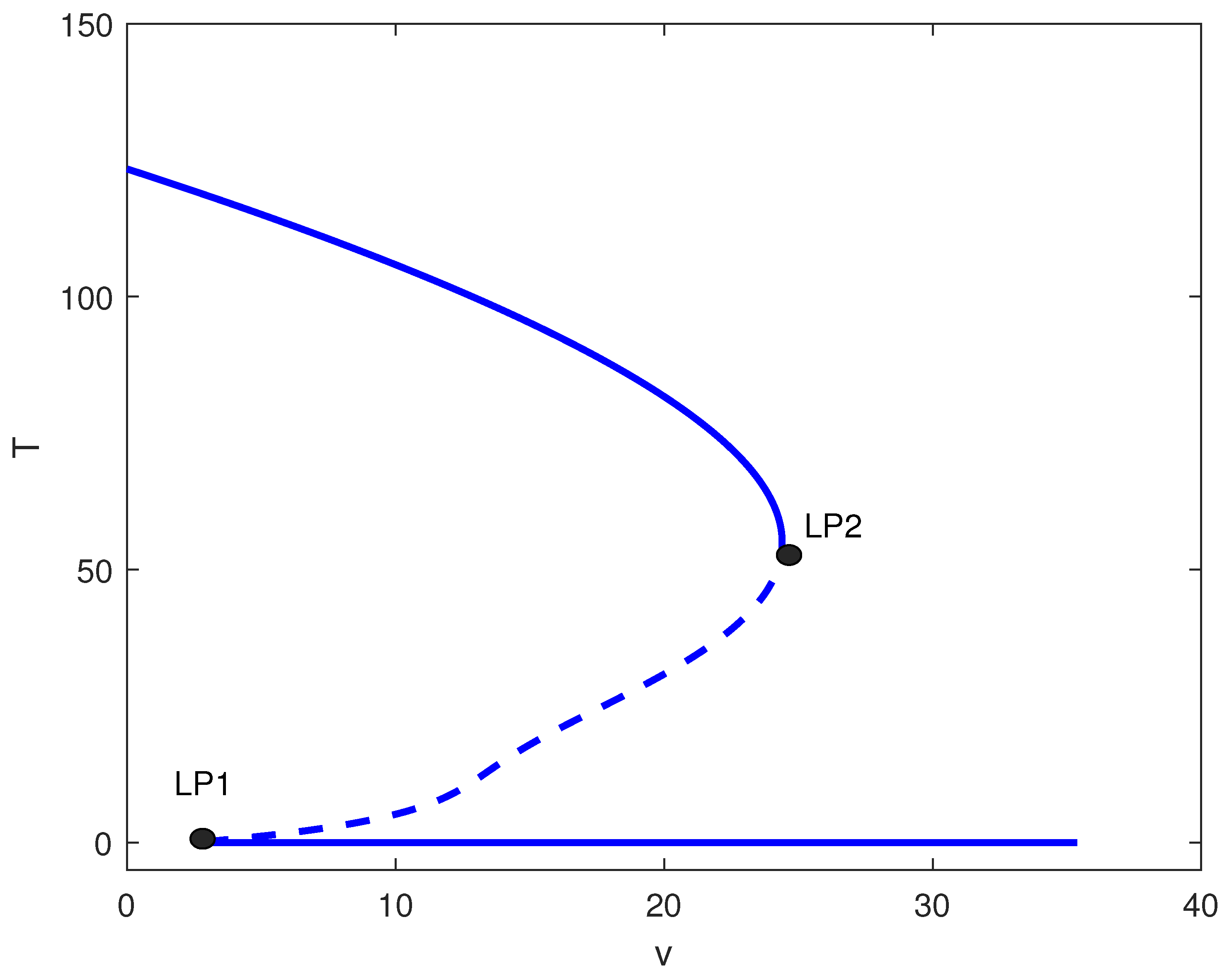

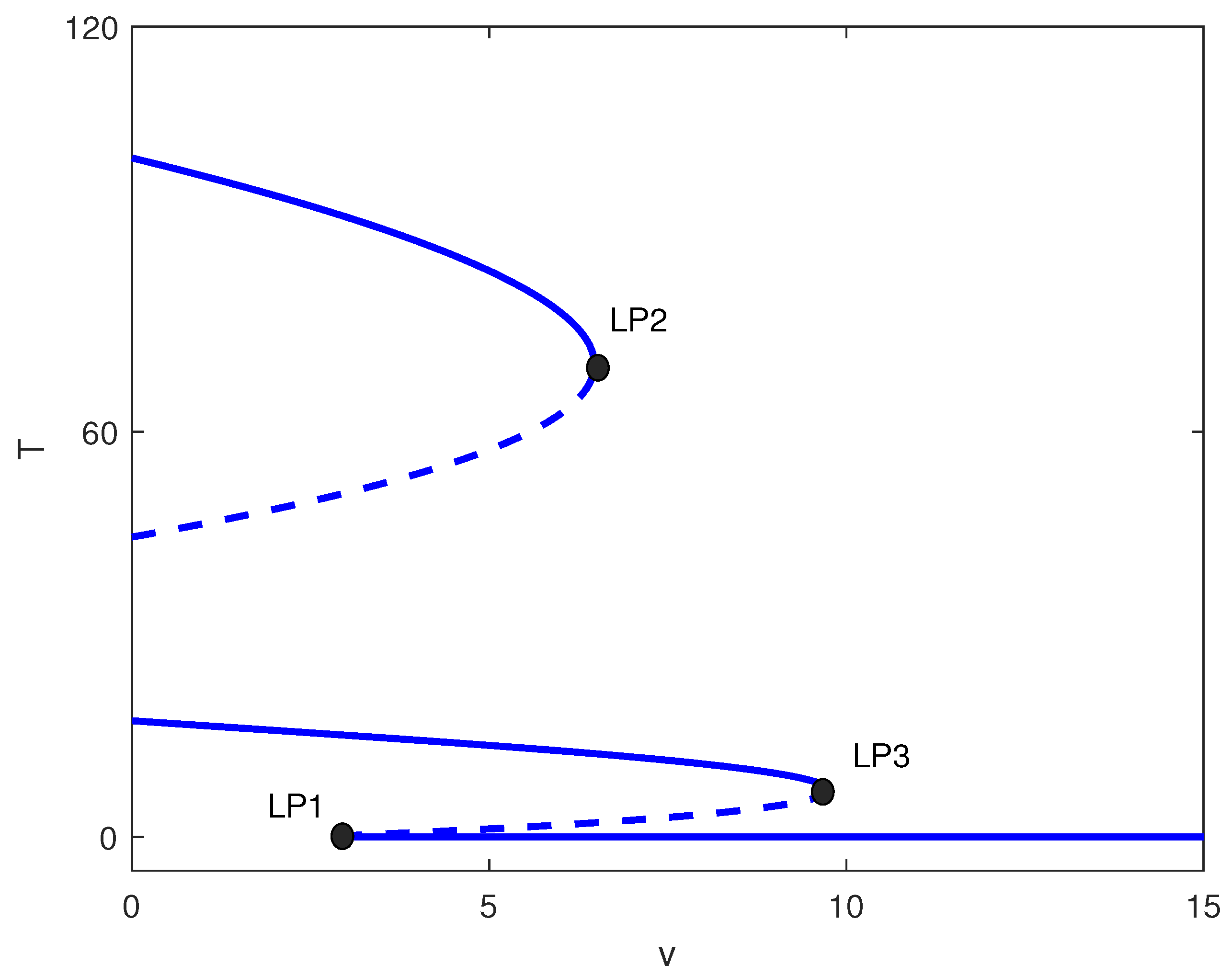

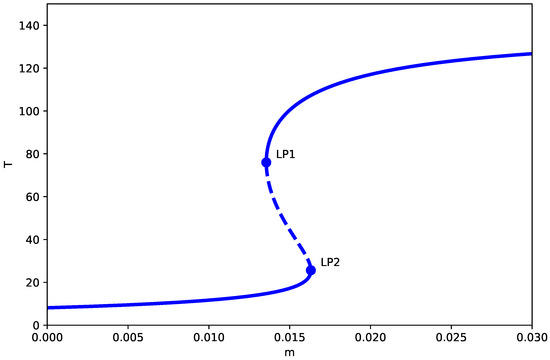

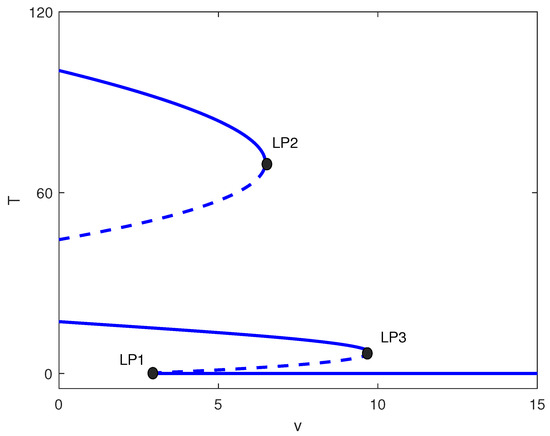

Figure 1 demonstrates the bifurcation diagram for the dimensionless system with baseline parameters. The bifurcation diagrams presented assume the generic non-degeneracy conditions detailed in Appendix B (Assumptions A2–A4), which hold for the parameter values studied. Under the generic conditions of Appendix B, the model anticipates two limit points (LP) at and , enclosing three distinct regimes:

Figure 1.

One-parameter bifurcation diagram (no chemotherapy, ) showing the tumor equilibrium level T (dimensionless) as a function of the immune inactivation rate m (dimensionless), with all other parameters fixed at the baseline values in Table 1. Solid (dashed) curves denote stable (unstable) equilibrium branches. and mark saddle-node (limit point) bifurcations separating monostable dormancy, bistability, and monostable high-tumor regimes.

- 1.

- Low tumor state (): The system converges to a spiral equilibrium with a very low concentration of tumor cells, the so-called “dormant state,” irrespective of the initial conditions. Biologically, this represents a state of immune surveillance where the immune system is able to effectively control tumor growth.

- 2.

- Bistable region (): A hysteresis zone appears where low and high tumor states coexist, separated by a saddle branch. Small noise or parameter variation may induce transitions between these states, thus depicting the clinical scenario of tumor escape from immune surveillance.

- 3.

- Elevated tumor level (): The system moves to a stable node with a large tumor load (“active state”), thus indicating the failure of the immune response and tumor progression without any restriction.

3.1.1. Key Comparison with Logistic Growth Model

A critical difference can be detected when these results are compared to the logistic growth model by Kuznetsov et al. [8]. Within our Gompertz model, the tumor-free equilibrium () is always unstable because of the singularity at . On the other hand, the tumor-free equilibrium in the logistic model changes its nature depending on parameter values: it is stable when and unstable otherwise (see Appendix A).

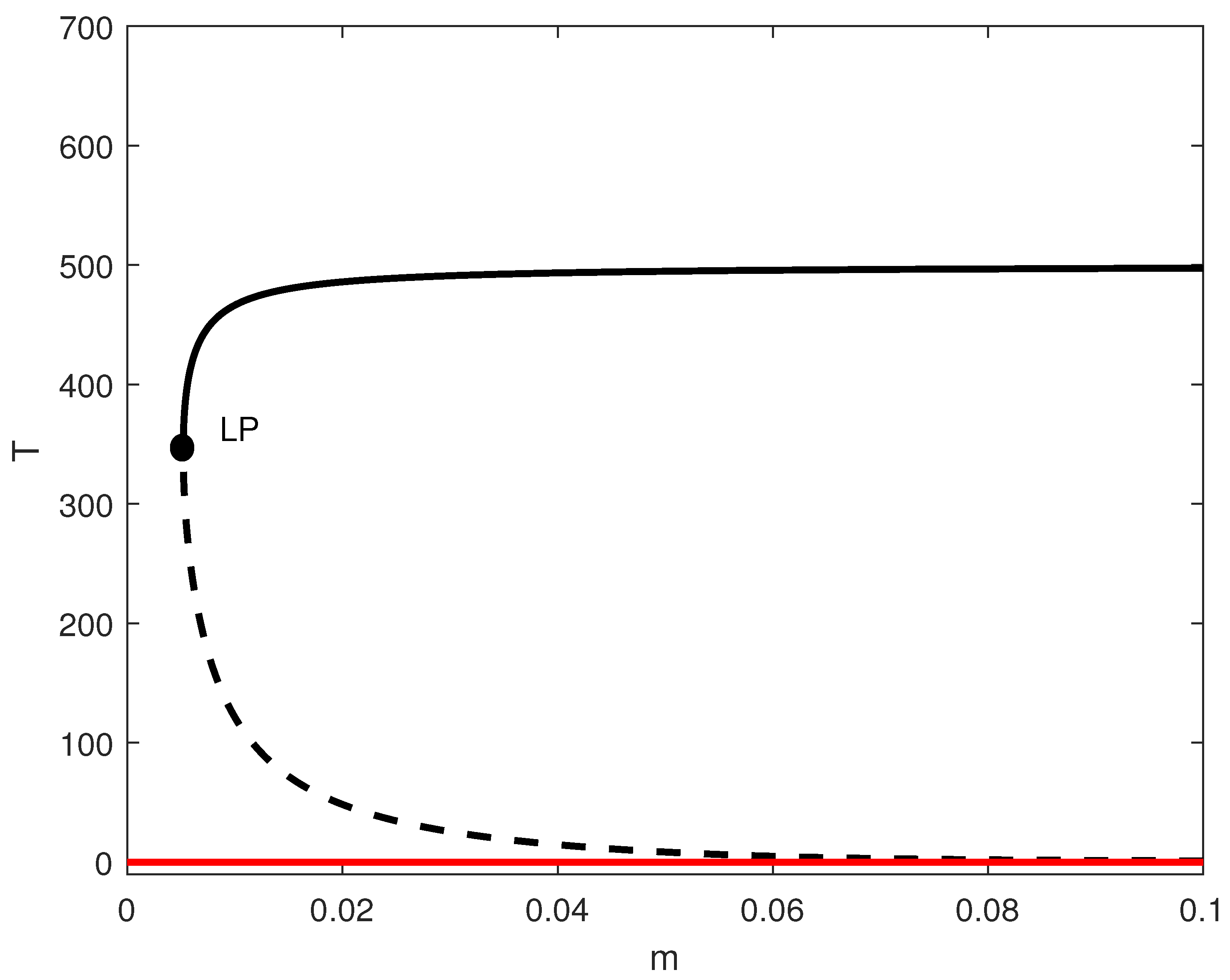

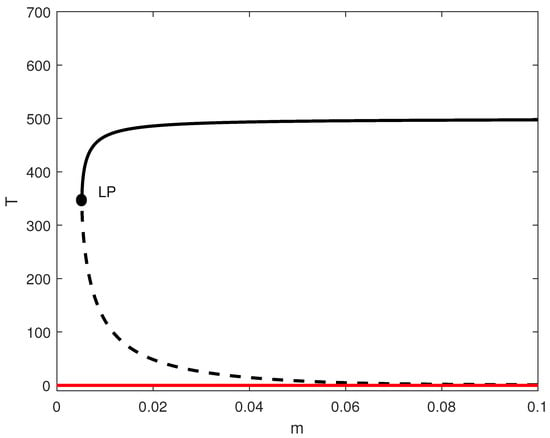

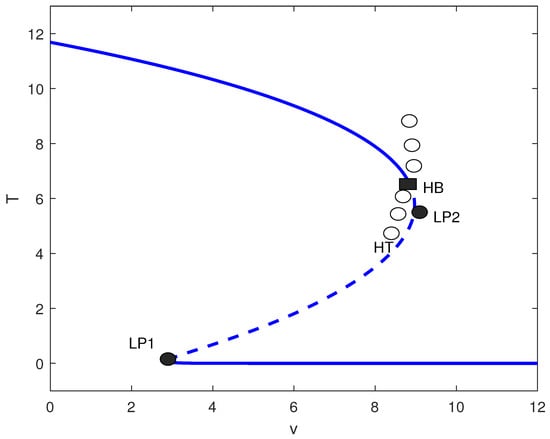

In order to highlight this difference, we conducted a logistic model simulation using parameters from [8] (, ). By setting and , we calculated ; thus, the tumor-free state became stable (Figure 2). Below the limit point, the system achieved a tumor-free equilibrium—a scenario that cannot be reached in the case of the Gompertz model. This pivotal distinction demonstrates how the selection of growth laws determines the therapeutic goal: eradication vs. containment.

Figure 2.

One-parameter bifurcation diagram for the model with no chemotherapy and logistic growth rate with and the rest of the parameters of Table 1. Solid (dashed) curves denote stable (unstable) equilibria; the solid red branch indicates a stable tumor-free equilibrium when it exists. LP denotes the saddle-node (limit point) bifurcation.

3.1.2. Conceptual Implications of the Tumor-Free Equilibrium Singularity

This disparity has profound biological consequences, that is, the Gompertz model exhibits a singularity at the tumor-free state, a mathematical feature that has two important conceptual interpretations ([20,28]):

- Model limitation at low densities: The singularity reflects a known limitation of continuum models at extremely low population densities. As , the continuum approximation breaks down, and stochastic effects (not captured by deterministic ODEs) become dominant. In this interpretation, the model cannot accurately represent dynamics near complete eradication, suggesting that alternative modeling approaches (e.g., stochastic models or agent-based models) would be needed to study tumor extinction events. This aligns with Eftimie et al.’s [28] review noting that ODE models have limitations at low population sizes where stochastic effects dominate. The best possible outcome in this deterministic framework is tumor dormancy rather than total elimination, consistent with d’Onofrio’s [20] observation that Gompertzian growth prevents complete immune-mediated eradication.

- Inherent biological property: Alternatively, this singularity may represent a genuine biological feature, i.e., Gompertz kinetics inherently prevent mathematical eradication because the per-capita growth rate diverges to infinity as . This could reflect biological realities such as:

- Enhanced proliferative capacity of residual cells in sparse environments.

- Non-linear density-dependent effects that violate the continuum assumption.

- The existence of a “minimal residual disease” threshold below which different biological mechanisms operate.

Clinical Interpretation: From a therapeutic perspective, the mathematical instability of the tumor-free equilibrium aligns with clinical observations of recurrence risk even after apparent complete response. Rather than suggesting that eradication is impossible, our model indicates that the deterministic Gompertz framework cannot capture the transition to true extinction. This distinction is crucial: the model predicts that tumors can be driven to arbitrarily low levels (dormancy) but cannot mathematically represent the stochastic extinction event that would correspond to clinical cure. This perspective is consistent with d’Onofrio’s [20] analysis of tumor evasion and immunotherapy, which emphasized the difficulty of achieving complete eradication.

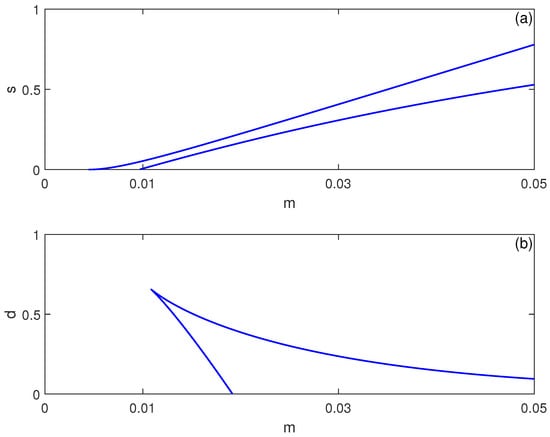

3.2. Parameter Sensitivity and Hysteresis Mapping

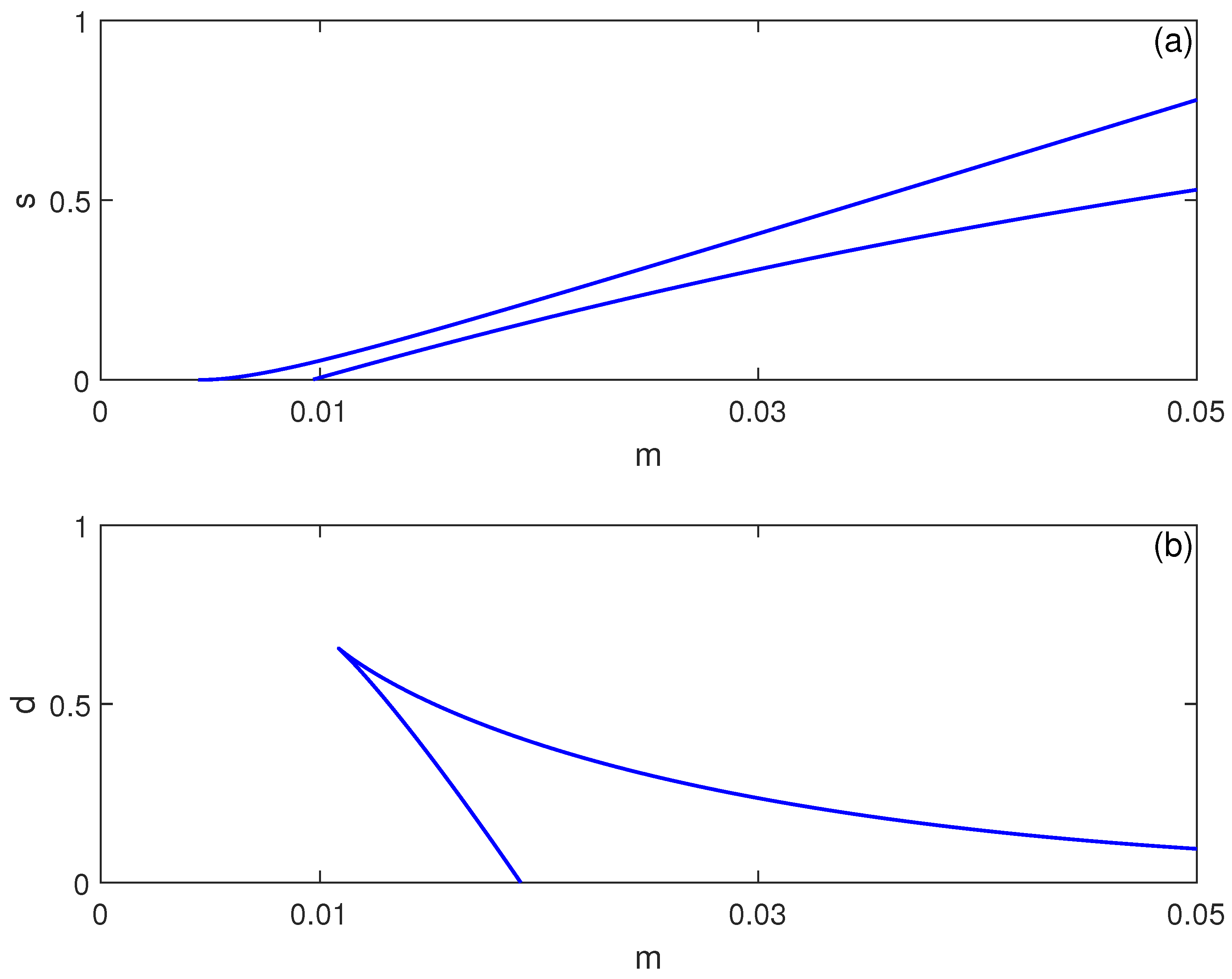

The bistability region’s extent depends critically on system parameters. Figure 3 shows two-parameter continuations in and spaces. Increasing immune cell influx expands the bistability region in terms of , suggesting that stronger baseline immunity paradoxically increases susceptibility to abrupt tumor escape—a phenomenon observed in clinical settings where robust immune responses sometimes precede rapid progression [26]. Conversely, decreasing immune cell death rate d widens the hysteresis region, indicating that enhancing immune cell longevity may stabilize dormancy but also enlarge the parameter range where sudden progression is possible.

Figure 3.

Two-parameter continuation of saddle-node (limit point) bifurcations for the no-chemotherapy case (), showing the locus of limit points from Figure 1 in (a) the plane and (b) the plane (dimensionless parameters). These curves delimit regions where multiple equilibria coexist (bistability) versus regions with a single stable equilibrium.

3.3. Hopf Bifurcation Points

In order to investigate the existence of Hopf bifurcation points in the model, we make use of the Dulac–Bendixson criterion [29].

Consider the function () and let us evaluate:

We have:

yielding

We also have:

yielding

Therefore

It can be seen that L is always negative. We conclude that the model cannot predict Hopf bifurcations for any (positive) model parameters. This conclusion holds for the chemotherapy-free model ().

4. Bifurcation Analysis with Chemotherapy Treatment

The introduction of chemotherapy () significantly enhances the dynamical repertoire of the system. We examine the system with drug intensity v serving as the main bifurcation parameter, since the treatment dose is a crucial clinical control variable.

4.1. Existence of Oscillatory Regimes

In this section we analyze the chemotherapy-included model (). The two conditions for Hopf bifurcation are derived from the Jacobian matrix J:

The Jacobian elements are obtained by taking the partial derivatives of the right-hand terms of Equations (3) and (4) with respect to :

Thus, one may also write

Let be a positive equilibrium; then, we have:

and

Substituting this into (10) yields

The remaining entries are

The first Hopf condition becomes:

while the second condition yields

It can be seen that the first Hopf condition (Equation (15)) is never satisfied when , so Hopf bifurcations do not occur in that case.

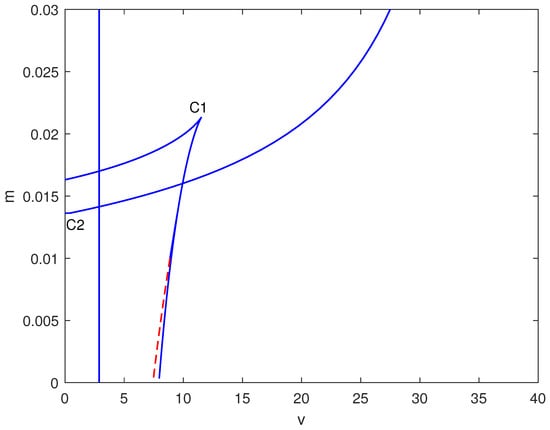

4.2. Comprehensive Bifurcation Structure

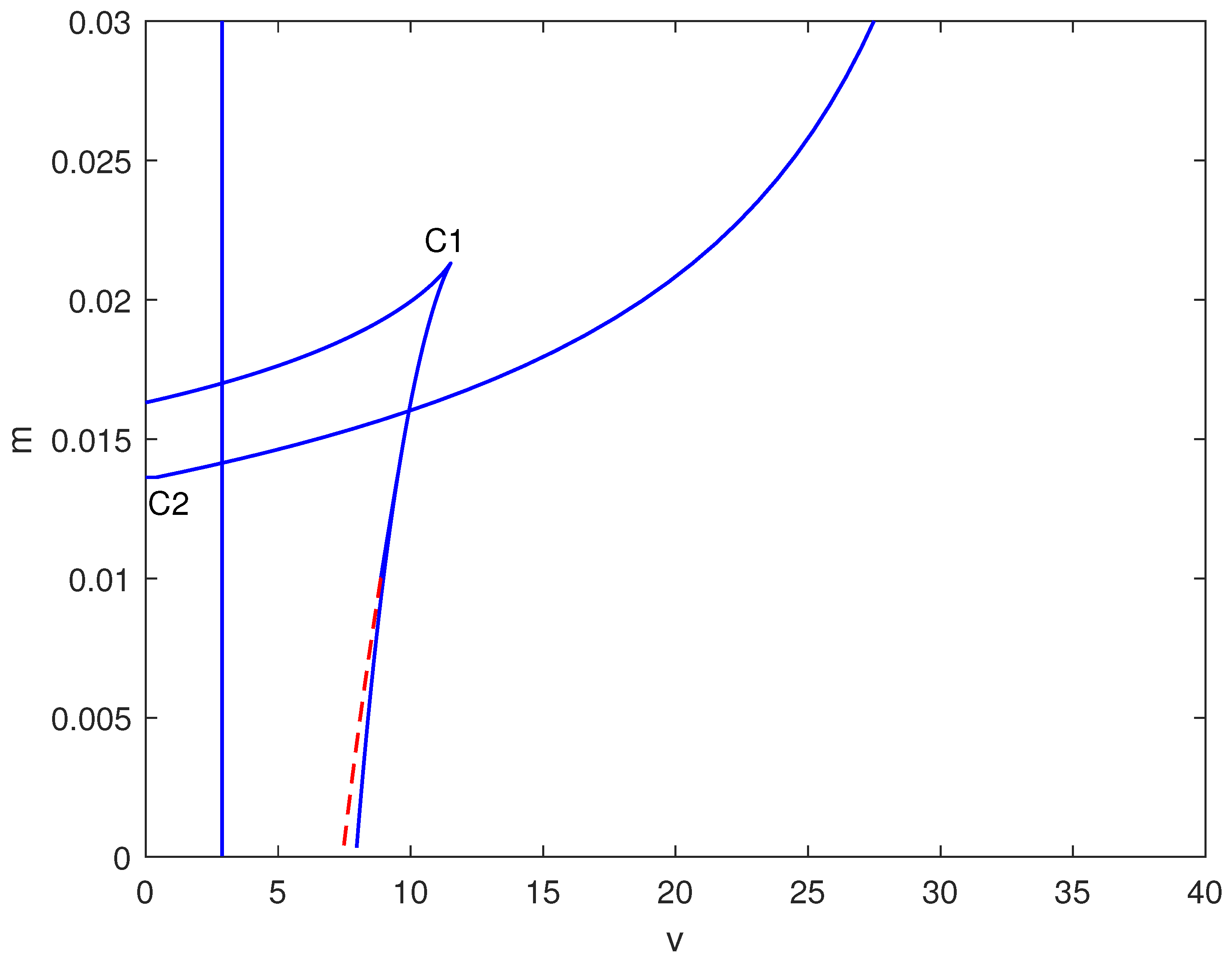

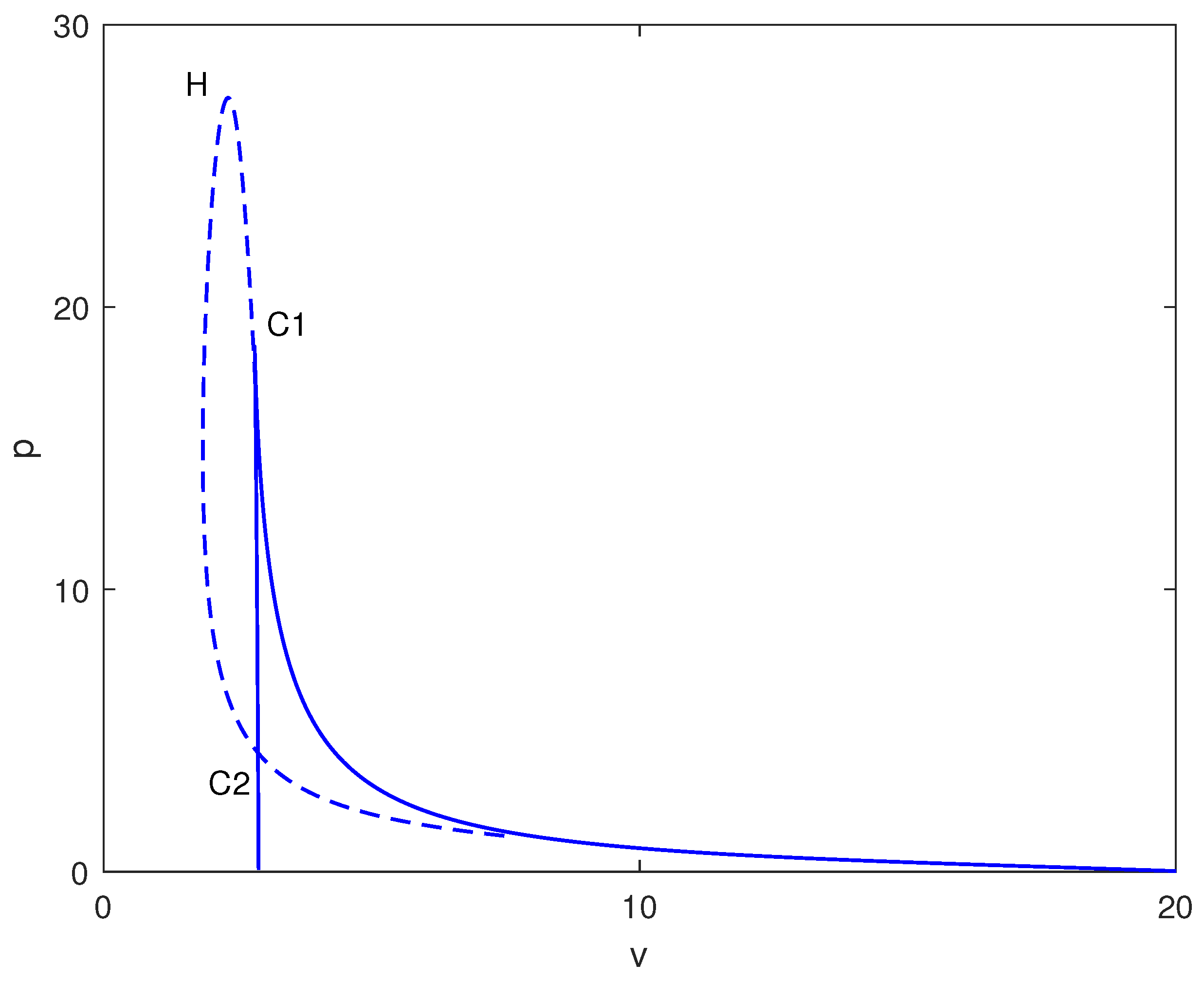

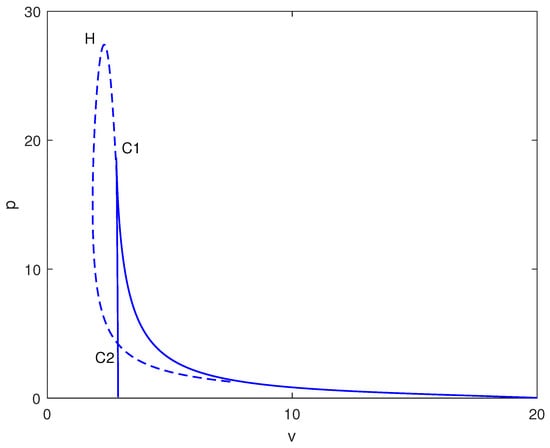

In Figure 4, a two-parameter continuation diagram is displayed in the space, highlighting the complex interactions between limit points (solid) and Hopf points (dashed). Significant features consist of a cusp at (C1) and a degenerate point at (C2). The relative positioning of these bifurcation curves generates several distinct dynamical regimes.

Figure 4.

Two-parameter bifurcation map in the plane (dimensionless chemotherapy intensity v vs. immune inactivation rate m) at baseline parameters (Table 1). Solid curves indicate loci of saddle-node (limit point) bifurcations; dashed curves indicate loci of Hopf bifurcations. Special points (e.g., cusp/degenerate points) are labeled and mark qualitative changes in the bifurcation structure that organize the observed multistability and oscillatory regimes.

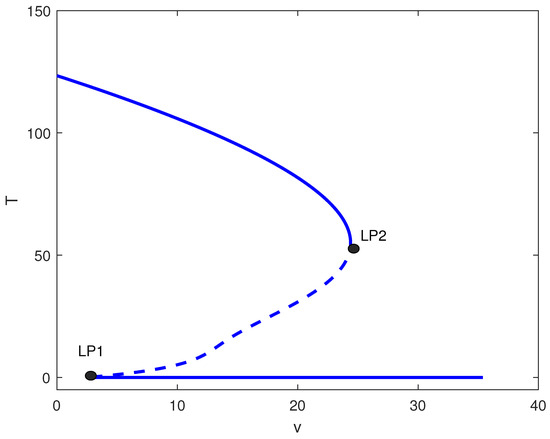

4.2.1. Case 1: Strong Immune Suppression ()

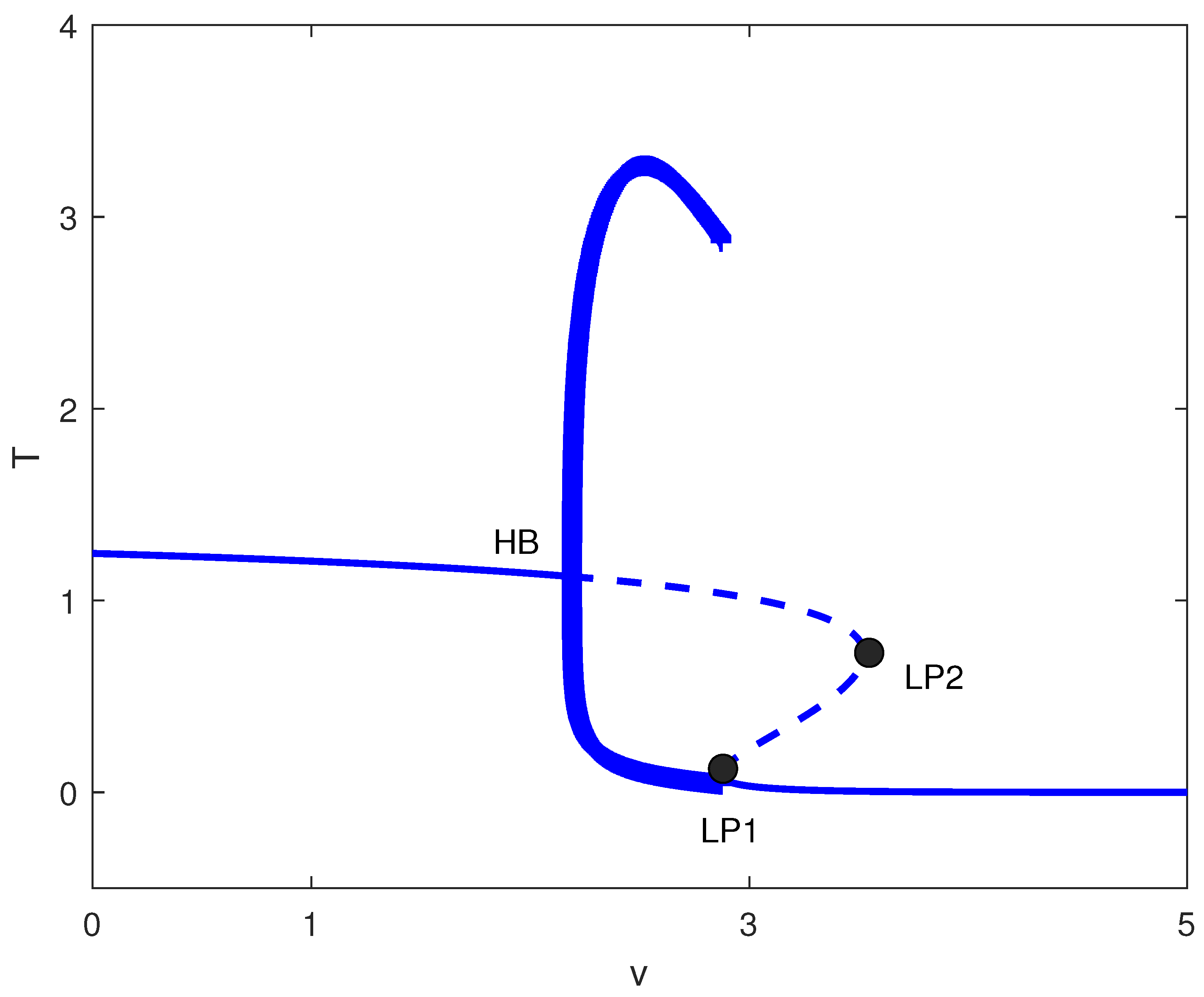

For large m values (strong tumor-induced immune suppression), the chemotherapy-free system exhibits only high tumor states. Figure 5 shows that introducing chemotherapy creates two limit points. For , high tumor burden persists. In , bistability emerges between low and high tumor states. Only for does chemotherapy consistently suppress tumors to low levels. Clinically, this suggests that for highly immunosuppressive tumors, chemotherapy must exceed a threshold dose to be effective, and subtherapeutic dosing may create windows of bistability where treatment failure becomes possible.

Figure 5.

One-parameter bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy showing tumor equilibrium level T (dimensionless) versus chemotherapy intensity v (dimensionless) at baseline parameters (Table 1) and fixed immune inactivation in Figure 4 (strong immune response). Solid (dashed) curves denote stable (unstable) equilibria. LP1 and LP2 are saddle-node bifurcations delimiting a bistable window between low- and high-tumor steady states.

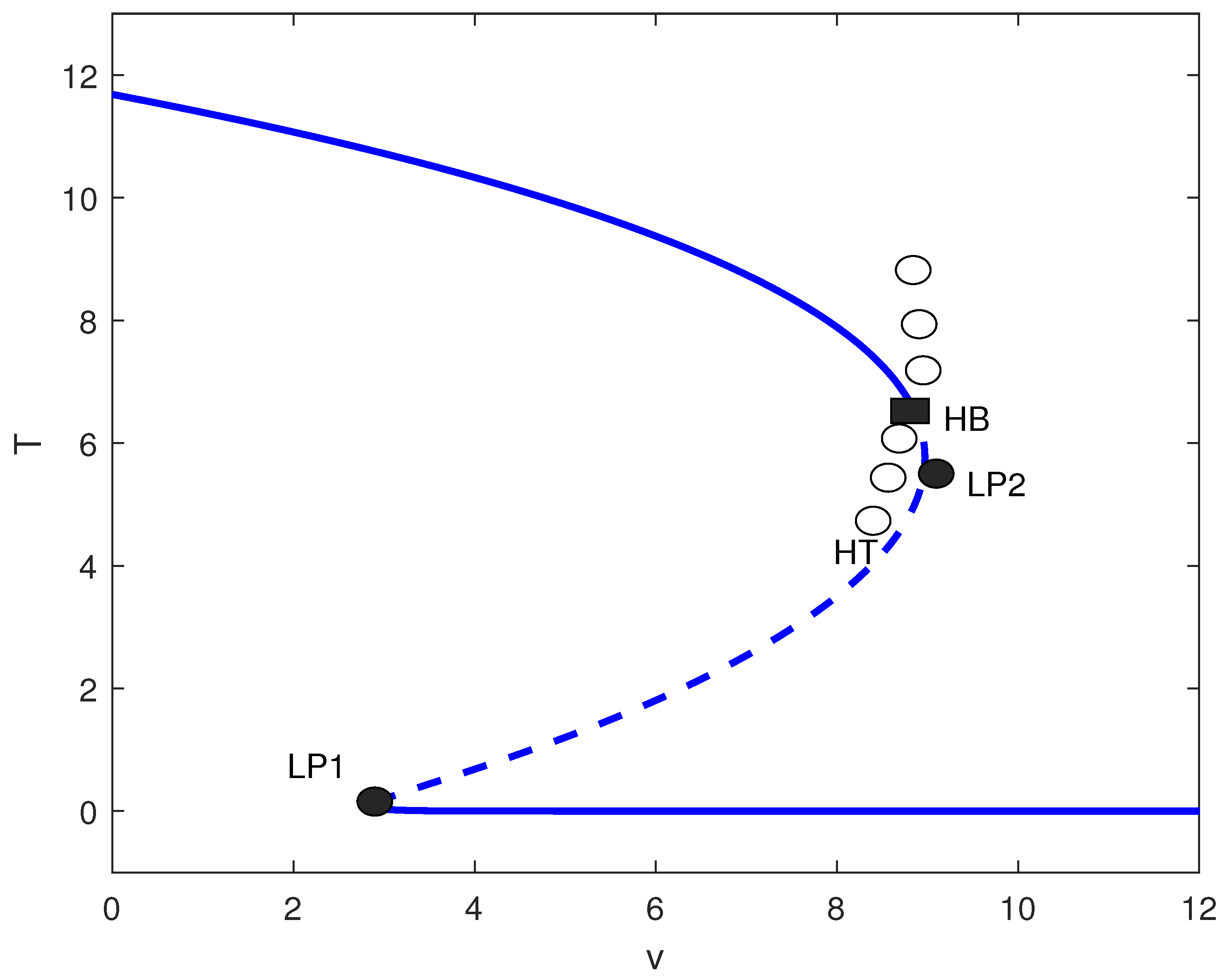

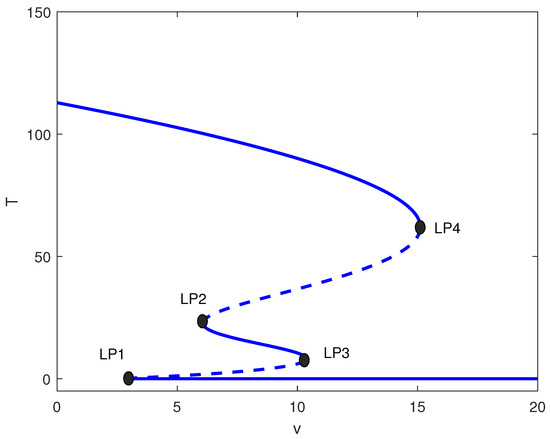

4.2.2. Case 2: Moderate Immune Suppression ()

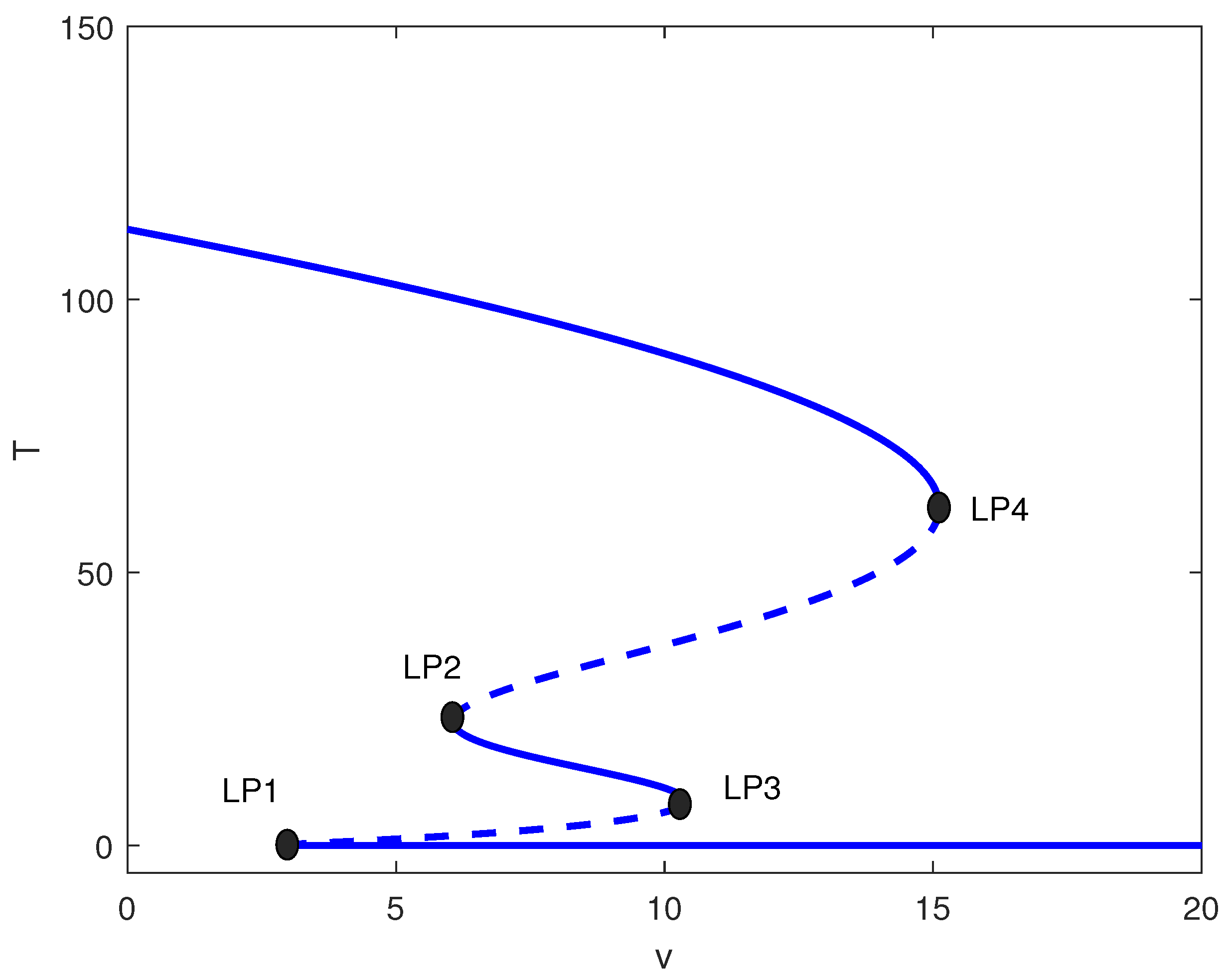

This intermediate range yields the richest dynamics. Figure 6 shows four limit points for . The system exhibits:

Figure 6.

One-parameter bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy showing tumor equilibrium level T versus chemotherapy intensity v at baseline parameters (Table 1) and fixed of Figure 4 (moderate immune suppression). Solid (dashed) curves denote stable (unstable) equilibria. Four labeled limit points (LP1–LP4) partition dose ranges exhibiting monostability, bistability, and multistability, including an intermediate stable tumor level.

- : High tumor state only;

- : Bistability (high/low);

- : Multistability (high/medium/low);

- : Bistability (high/low);

- : Low tumor state only.

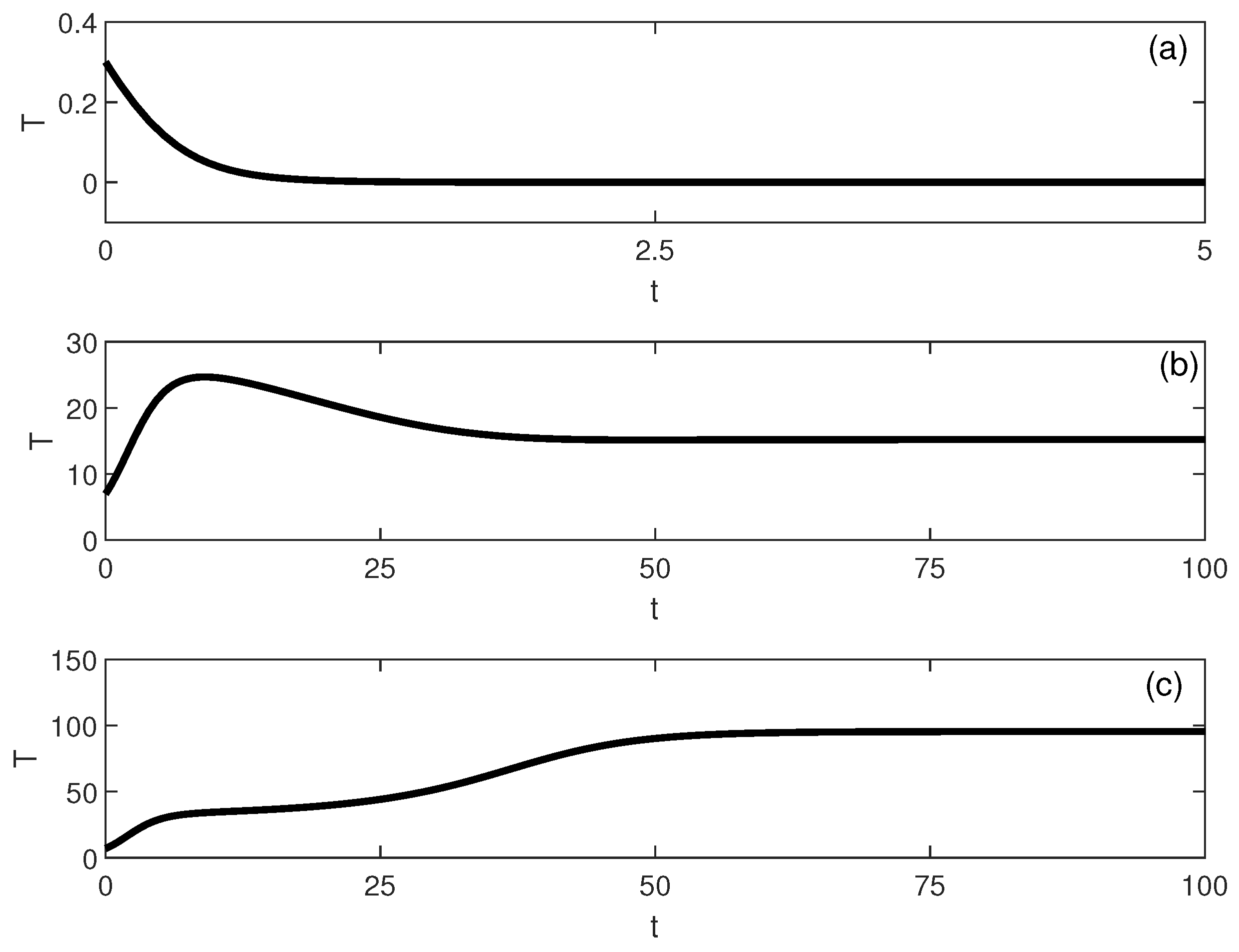

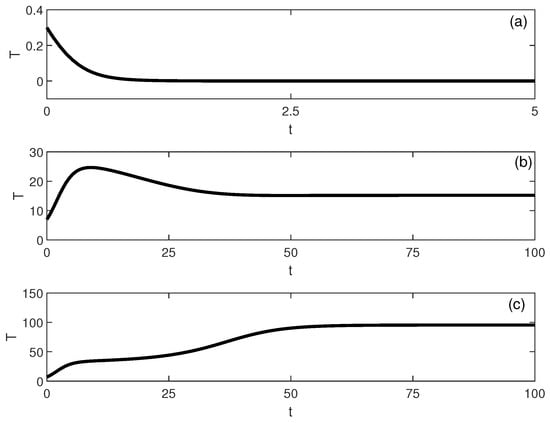

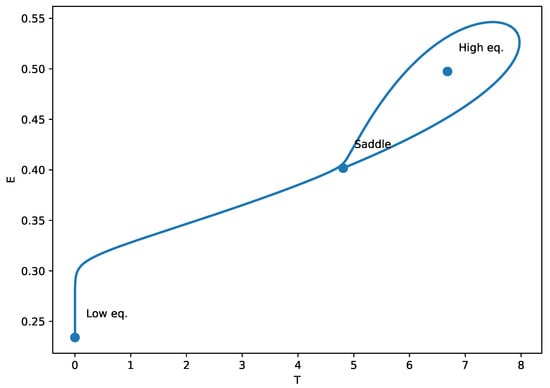

The emergence of a stable intermediate tumor state (Figure 6) represents a novel prediction not found in logistic-based models. This intermediate state may correspond to clinical scenarios of partial response or stable disease, where tumors persist at reduced but detectable levels. Simulations, shown in Figure 7, illustrate multistability at of Figure 6. Start-up conditions lead to low tumor levels, lead to intermediate tumor levels and a decrease in the effector cells, and push the system to high tumor levels.

Figure 7.

Time-domain simulations illustrating multistability for the parameter set of Figure 6 at (with baseline parameters and ). The tumor trajectory (dimensionless) converges to different long-term steady states depending on the initial condition: (a) low-tumor attractor for , (b) intermediate-tumor attractor for , and (c) high-tumor attractor for .

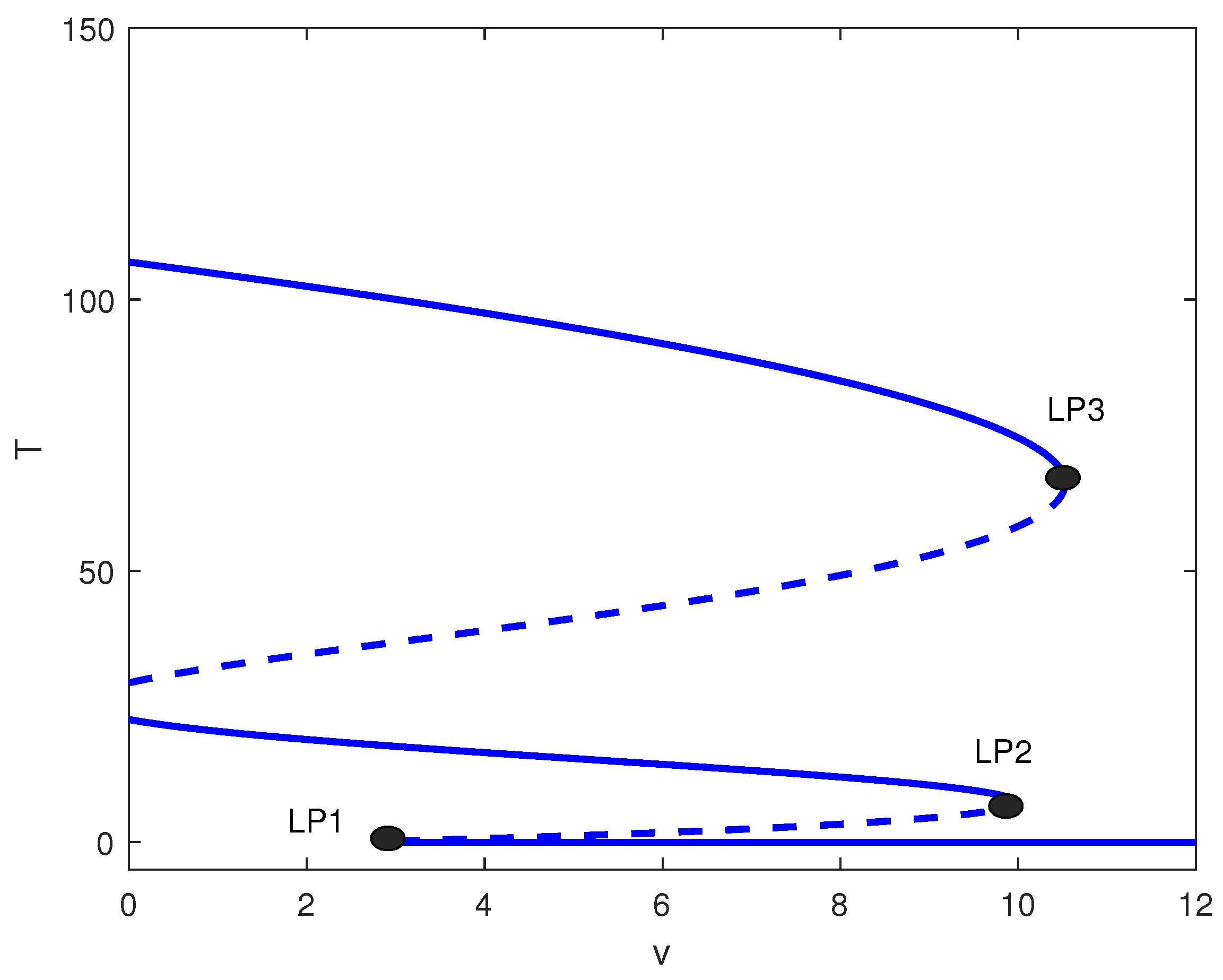

The relative position of the different limit points in Figure 6 can give rise to other alternative behavior. Figure 8 shows the bifurcation diagram for . Recall that with no treatment, the case corresponds to bistability between the dormant and active tumor cells (Figure 1). Figure 8 shows that, since one limit point is negative, the system exhibits bistability between a middle and high tumor cell state for values of v less than . The range of v between and is characterized by multistability, which encompasses low, medium, and high tumor cell regimes. In the interval from to , the system shows bistability, limited to low and high cell concentrations. For values of v that surpass , the tumor cell concentration remains low for any given initial conditions.

Figure 8.

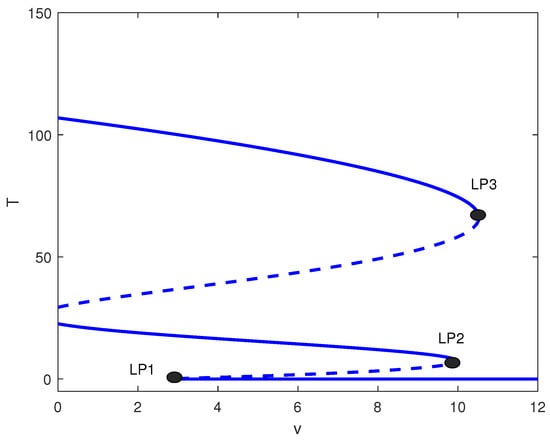

One-parameter bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy showing tumor equilibrium level T versus chemotherapy intensity v at baseline parameters (Table 1) and fixed in Figure 4. Solid (dashed) curves denote stable (unstable) equilibria. The labeled limit points (LP1–LP3) bound dose intervals with bistability and/or multistability among low-, intermediate-, and high-tumor steady states.

A distinct situation is presented in Figure 9 for the value of . Here, for values of v that fall below , bistability is observed between the intermediate and high cell populations. For values of v that lie between and , there exists multistability between low, intermediate, and high cellular regimes. In contrast, for values of v situated between and , bistability is observed between low and medium cellular states. Values of v larger than lead to low tumor cell concentration.

Figure 9.

One-parameter bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy showing tumor equilibrium level T versus chemotherapy intensity v at baseline parameters (Table 1) and fixed of Figure 4. Solid (dashed) curves denote stable (unstable) equilibria. The labeled limit points (LP1–LP3) partition dose ranges exhibiting bistability and multistability among low-, intermediate-, and high-tumor regimes.

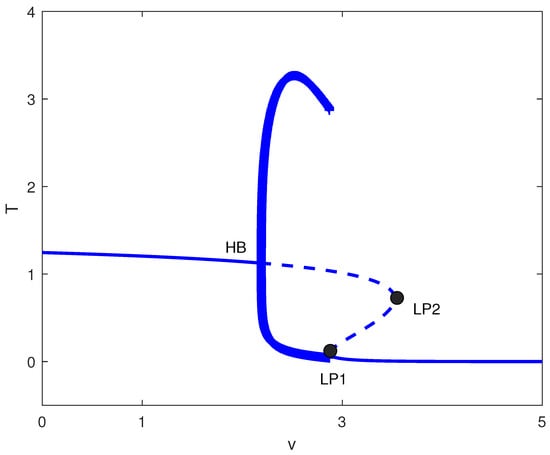

4.2.3. Case 3: Weak Immune Suppression ()

For small m (effective immune surveillance), the chemotherapy-free system exhibits low tumor states. Figure 10 shows that adding chemotherapy induces a Hopf bifurcation () and homoclinic termination (). For the baseline parameter set with , MatCont located the Hopf point at with equilibrium and first Lyapunov coefficient . Since , this Hopf bifurcation is supercritical, giving rise to stable limit cycles for . For , low tumor states persist. In , bistability occurs between low and high states. Between and , unstable oscillations exist, while for , very low tumor levels are achieved. This suggests that for immunocompetent hosts, chemotherapy must be carefully dosed: excessive treatment may destabilize the system without improving outcomes.

Figure 10.

Tumor bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy: equilibrium/periodic tumor levels T versus drug intensity v (dimensionless), at baseline parameters (Table 1) with fixed immune inactivation of Figure 4. Solid (dashed) curves are stable (unstable) equilibria; LP1 and LP2 are saddle-node (limit point) bifurcations; HB is a Hopf bifurcation, and HT marks homoclinic termination. Open circles indicate an unstable periodic-orbit branch.

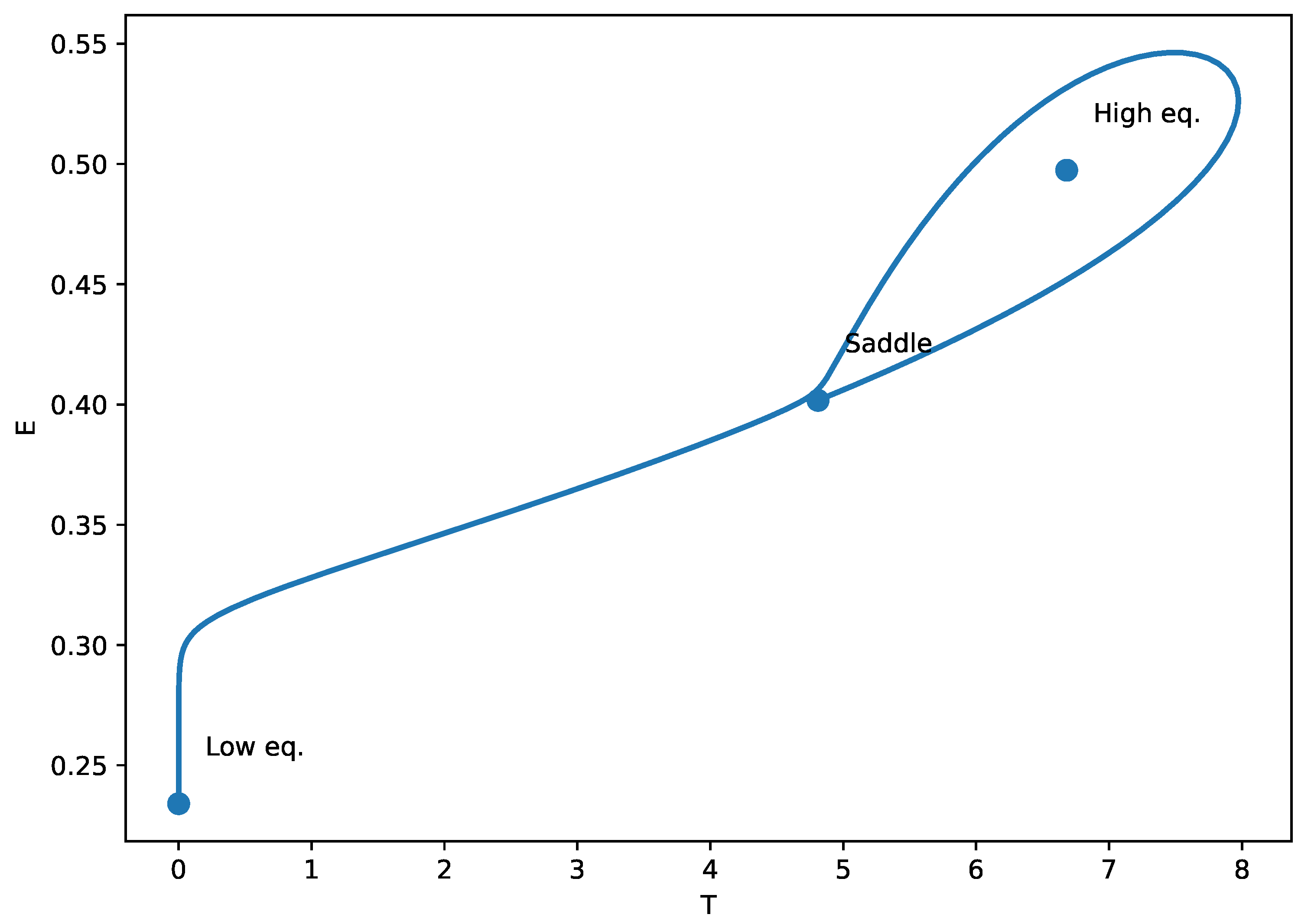

4.2.4. Global Bifurcations and Homoclinic Orbits

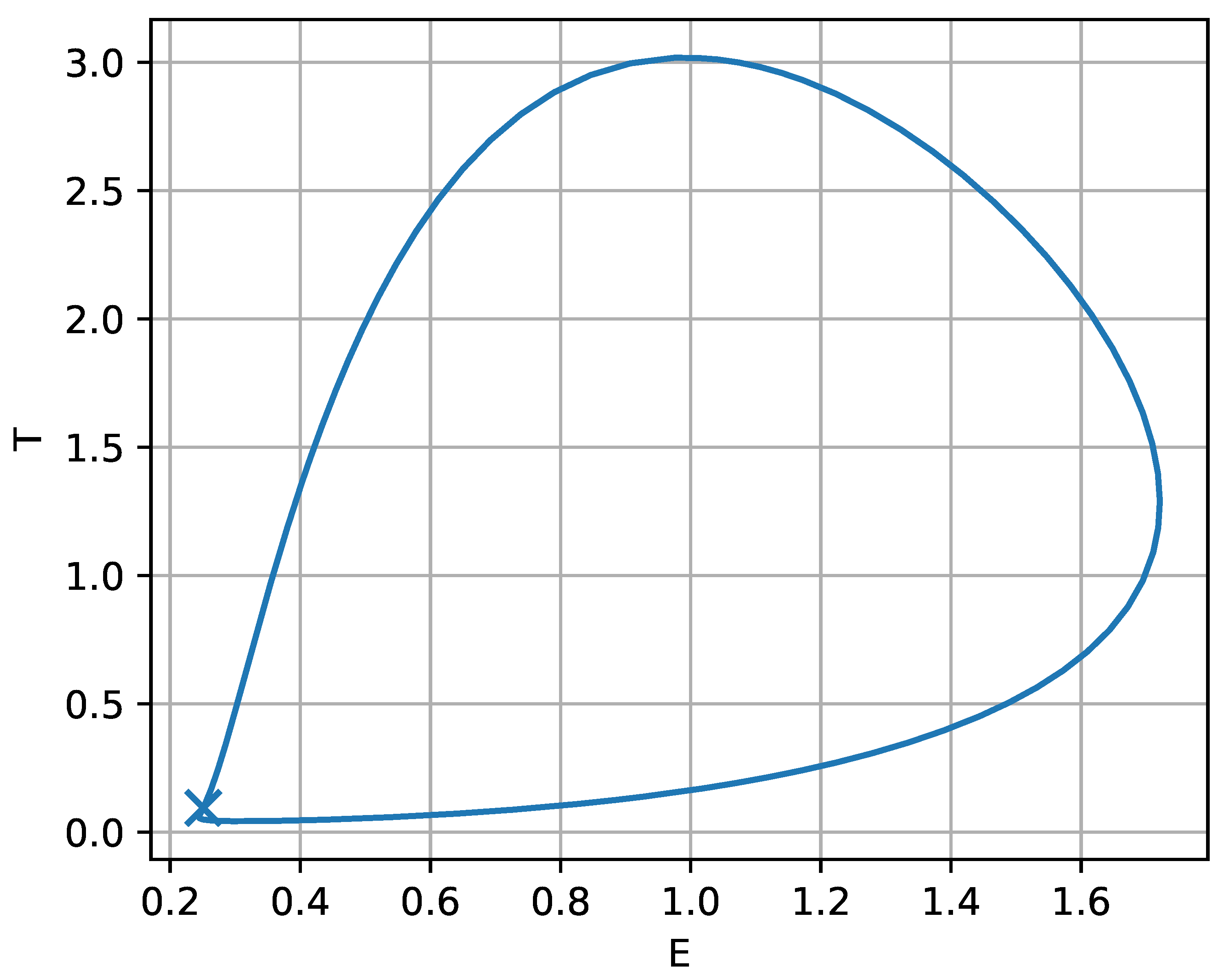

The identification of homoclinic termination (HT) points in Figure 10 indicates the presence of a global bifurcation mechanism, arising from a Bogdanov Takens (BT) codimension-two point in parameter space. The phase-plane plot (Figure 11) illustrates the homoclinic termination looks: the trajectory forms a large loop that returns very near the saddle equilibrium. At an exact homoclinic termination (HT), the periodic orbit collides with the saddle, so the loop is a true homoclinic connection (the oscillation period grows without bound as the orbit approaches the saddle). In the context of our tumor-immune chemotherapy model, the emergence of these homoclinic orbits signifies a critical dynamical transition where small changes in treatment dose (v) or immune suppression (m) can cause the system to abruptly shift from oscillatory behavior (periodic tumor-immune fluctuations) to a multistable regime or a high-tumor steady state. Biologically, this corresponds to a tipping point in treatment response: near the homoclinic bifurcation, minimal variations in drug efficacy or immune function may lead to sudden loss of tumor control or the cessation of cyclical regression–progression patterns. Recognizing such global bifurcations is therefore essential for anticipating nonlinear therapeutic thresholds and for designing treatment schedules that avoid destabilizing, irreversible transitions in tumor burden.

Figure 11.

Phase-plane portrait at the homoclinic threshold (HT) of Figure 10. The trajectory forms a homoclinic loop. This global bifurcation signals the disappearance/termination of a periodic orbit, and the oscillation period becomes very large close to HT.

4.2.5. Alternative Bifurcation Structures

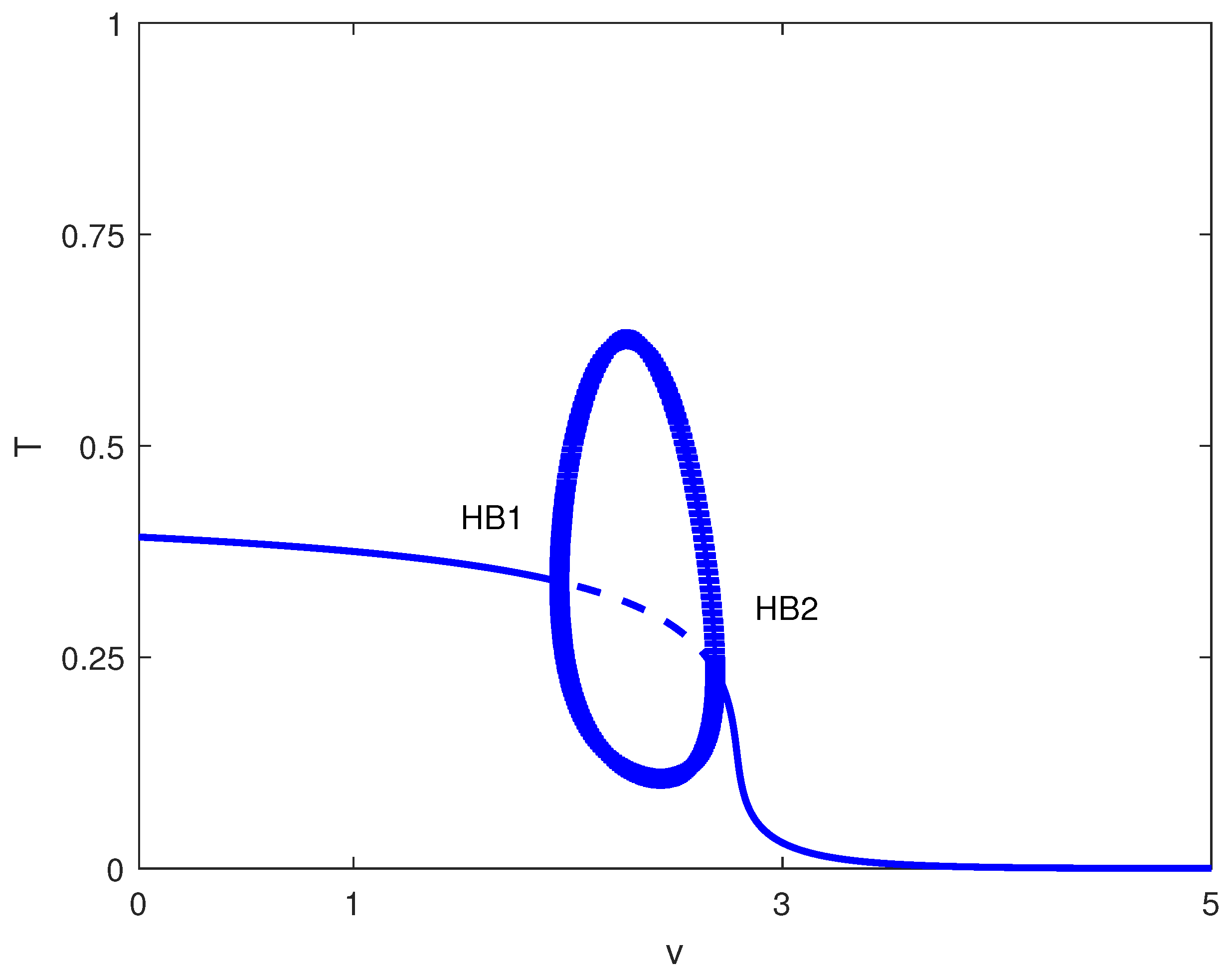

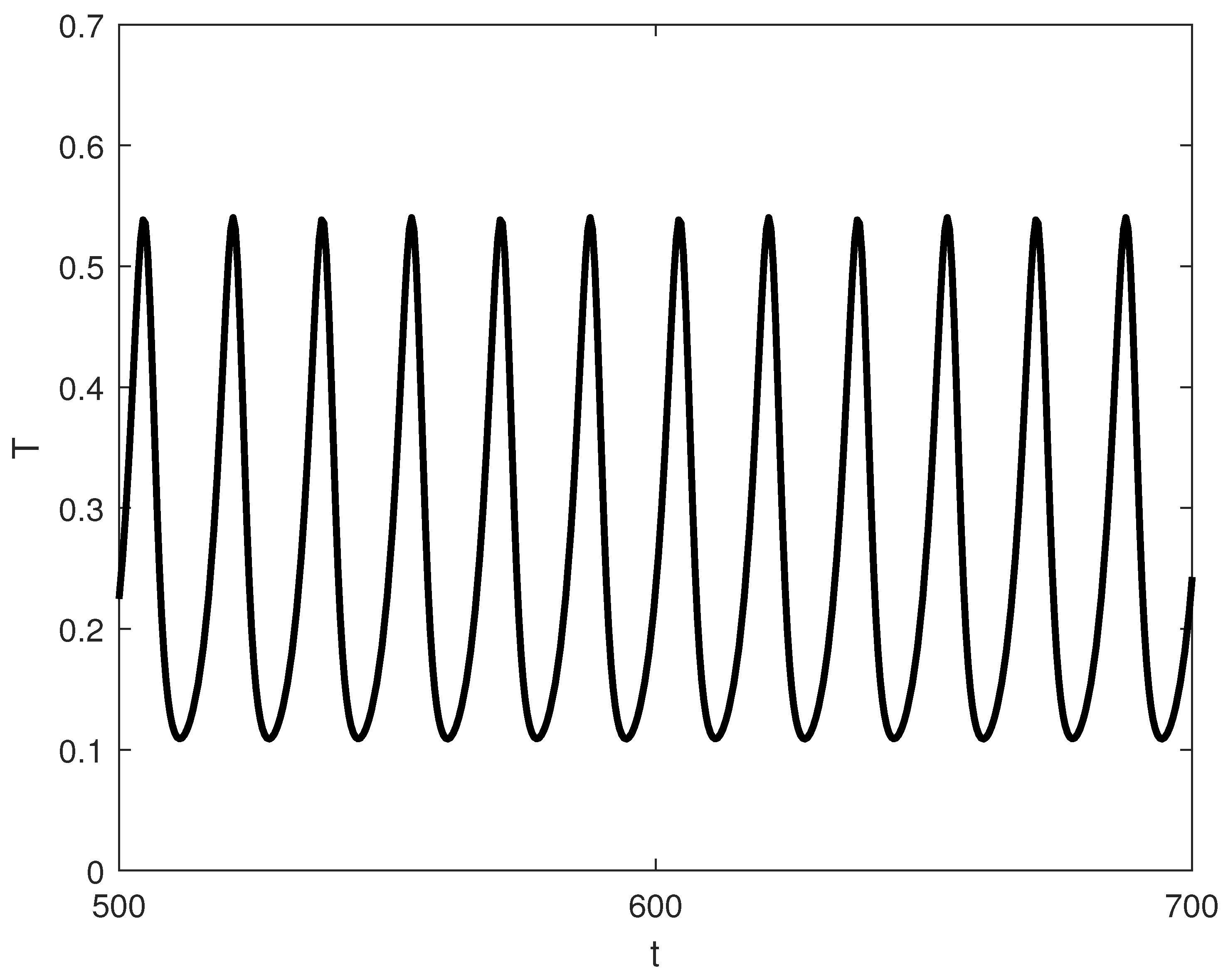

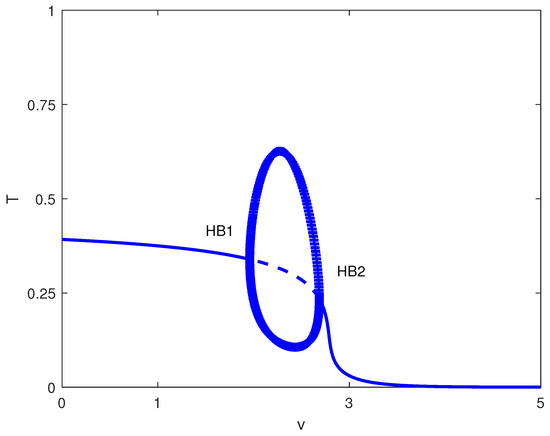

Exploring other parameter spaces reveals additional dynamical phenomena. Figure 12 shows continuations. For large values of p (strong immune recruitment, e.g., ), the system exhibits two Hopf points without limit points (Figure 13), yielding stable oscillations as the sole attractor within a dose range. MatCont yielded at with , and at with . These two Hopf points delimit the oscillatory regime shown in Figure 13. Figure 14 shows oscillations at of Figure 13, for arbitrary initial conditions. This represents periodic tumor-immune fluctuations potentially corresponding to clinical cycles of progression and regression.

Figure 12.

Two-parameter continuation with chemotherapy in the plane (drug intensity v vs. immune recruitment p, dimensionless) at baseline parameters (Table 1). Solid curves: loci of limit points (saddle-nodes); dashed curves: loci of Hopf bifurcations, separating steady-state and oscillatory regimes.

Figure 13.

Bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy at baseline parameters (Table 1) and fixed immune recruitment : tumor level T versus drug intensity v (dimensionless). Solid (dashed) curves are stable (unstable) equilibria; HB1 and HB2 are Hopf bifurcations. Filled circles denote stable periodic (limit-cycle) solutions in the projection.

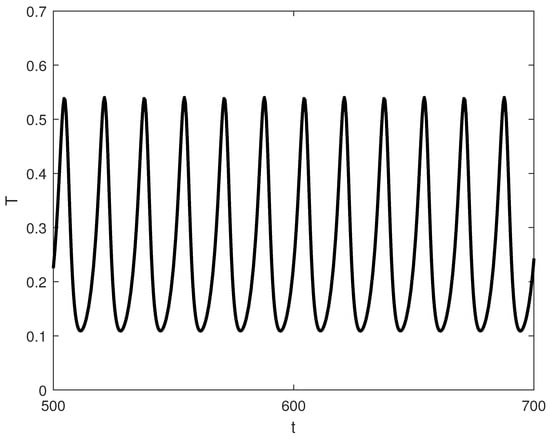

Figure 14.

Representative time-series at for the oscillatory regime in Figure 13 (, baseline parameters), showing convergence of to a stable limit cycle for typical initial conditions.

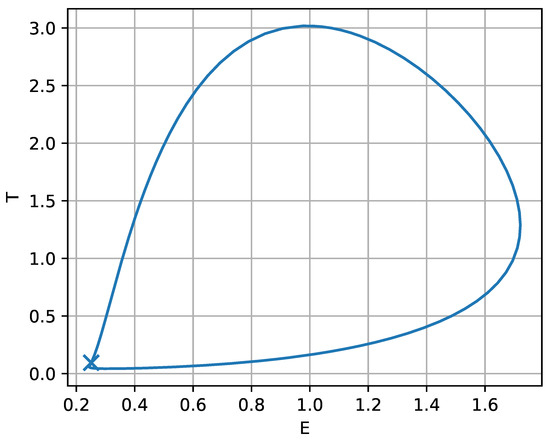

For intermediate values of p (i.e., ), the sequence emerges (Figure 15), where oscillatory and steady-state regimes coexist. For weak chemotherapy (), trajectories converge to a stable equilibrium with relatively high T, corresponding biologically to tumor persistence despite an ongoing immune response. At the Hopf point , the equilibrium loses stability and a stable periodic orbit (limit cycle) is created; thus, in the intermediate range , the system is attracted to sustained oscillations in rather than to a constant tumor size. Biologically, this oscillatory regime represents recurrent tumor-immune cycles: phases of tumor expansion are followed by an enhanced effector response that suppresses the tumor, after which immune activity wanes and the tumor can regrow, producing repeated flare-ups and remissions. The limit points and are folds of equilibria that structure the return to steady outcomes as v increases: between these folds, multiple equilibria can coexist (with different stability), implying the potential for threshold effects and sensitivity to initial conditions or transient perturbations, whereas for sufficiently strong chemotherapy (), only a single equilibrium remains at very low T, corresponding biologically to sustained tumor suppression (and, in this simplified model, a robust treatment outcome).

Figure 15.

Bifurcation diagram with chemotherapy at baseline parameters (Table 1) and fixed immune recruitment : tumor level T versus drug intensity v (dimensionless). Solid (dashed) curves are stable (unstable) equilibria; HB is a Hopf bifurcation, and LP1 and LP2 are saddle-node (limit point) bifurcations. Filled circles denote stable periodic solutions coexisting with equilibria over a finite dose range.

To complement Figure 15, the phase–space portrait in the plane (Figure 16) shows a representative orbit for v chosen just below . The closed loop is the stable limit cycle associated with the oscillatory window in Figure 15 and provides a geometric picture of the tumor-immune cycling described above. The marked point at indicates the nearby equilibrium around which the trajectory slows markedly; as v gets closer to the orbit lingers near this threshold state, producing long-period oscillations. From a biological standpoint, this suggests that treatment levels close to the boundary may yield prolonged intervals of low tumor burden punctuated by occasional rebounds, whereas increasing v beyond the fold-organized transition can eliminate cycling and drive the system toward a stable low-tumor state. In clinical terms, Figure 15 therefore highlights three qualitatively distinct response regimes with increasing chemotherapy intensity: persistently high tumor load (undertreatment), cyclic relapse–remission dynamics (intermediate treatment), and sustained suppression at low tumor burden (strong treatment), with the fold points indicating sharp transitions between these regimes.

Figure 16.

Phase–plane portrait corresponding to the oscillatory regime in Figure 15, for drug intensity v chosen just below the lower limit point . The closed orbit is a stable limit cycle (persistent tumor-immune oscillations) surrounding the nearby equilibrium (marked).

5. Biological Interpretation and Clinical Implications

The bifurcation analysis highlights the discrepancies between the Gompertz and logistic growth equations, which have significant implications for our understanding of tumor-immune interactions and therapeutic design.

5.1. Cancer Immunoediting Framework

The dynamical behaviors predicted by our model, dormancy, multistability, and oscillations, fit naturally within the cancer immunoediting framework (elimination, equilibrium, escape) discussed in tumor-immune modeling [20,28].

Elimination: While immune-mediated clearance is possible in principle, our Gompertz-based model yields an always-unstable tumor-free equilibrium, reflecting the clinical rarity of complete eradication and the persistence of residual cells that can drive relapse. This is consistent with the observation that Gompertzian growth can prevent deterministic immune eradication [20].

Equilibrium: Bistability and multistability correspond to immune control without elimination, capturing dormancy, stable disease, and partial responses through coexisting low-, intermediate-, and high-tumor stable states that are commonly reported in ODE tumor-immune models [28].

Escape: Shifts to a high-tumor state represent immune evasion, promoted by increased immune inactivation (m), reduced recruitment (p), or insufficient chemotherapy. Importantly, escape can be reversible in the model: stronger dosing or immune stimulation can return the system to equilibrium or induce oscillatory dynamics, consistent with tumor evasion mechanisms studied in [20].

Overall, the lack of stable tumor-free equilibria under Gompertz growth highlights persistent recurrence risk, while chemotherapy-induced oscillations suggest ongoing, non-resolved tumor-immune competition that may resemble clinical cycles of regression and progression.

5.2. Multistability and Treatment Resistance

The discovery of up to four coexisting steady states under chemotherapy provides a mathematical basis for the heterogeneity observed in patient responses during the equilibrium phase of immunoediting. Multistability explains why patients with similar clinical profiles may experience different outcomes—such as complete response, stable disease, or progression—depending on initial immune-tumor conditions, stochastic events, or treatment history. This complexity aligns with d’Onofrio’s [20] metamodeling approach, which emphasized the polymorphic nature of cancer and the need for models that capture diverse dynamical behaviors.

The intermediate stable state is of particular interest because it most closely resembles the clinical condition of stable disease or partial response. In these cases, the tumors do not completely disappear; they persist at a lower, still measurable, level, thus highlighting the variety of treatment responses seen in practice.

This multistability mirrors the dynamic flexibility of the equilibrium phase, where immune surveillance and tumor adaptation coexist. The intermediate stable state, in particular, represents a clinically relevant scenario of controlled but persistent disease, highlighting the need for personalized and adaptive treatment strategies. Eftimie et al. [28] noted that such complex dynamics emerged naturally from simple ODE models, underscoring their utility in understanding treatment heterogeneity.

5.3. Oscillatory Dynamics and Treatment Scheduling

One of the most exciting features of our model is how it handles oscillatory dynamics. The model never produces periodic behavior across all parameter combinations if no chemotherapy is given. This is consistent with the real world, where oscillations between tumor and immune cell populations are not observed. The likely explanation for this absence is the natural suppression of such fluctuations in biological systems due to the inherent risk of triggering autoimmune responses. While oscillatory dynamics could theoretically be a factor in tumor growth by temporarily weakening the immune system, such dynamics have not been reported in tumor-immune interactions. This again affirms the biological credibility of our model even in its most simplified version.

But the introduction of chemotherapy completely changes the scenario. The oscillations emerge only after the saturation of the drug’s effects, which is a very realistic pharmacodynamic behavior. These cycles imply that certain dosing schedules could result in rhythmic interactions between tumors and the immune system. Such dynamics could explain the periodic fluctuations in tumor markers that clinicians frequently observe during therapy.

The most important point here is that the absence of oscillations in cases without treatment gives further support to clinical evidence: untreated tumors usually progress steadily, rather than exhibiting cyclical patterns.

Chemotherapy-induced oscillations, on the other hand, may reflect intermittent periods of immune activation and tumor suppression, akin to dynamic fluctuations within the equilibrium phase. These cycles could explain observed periodic variations in tumor markers and clinical symptoms, suggesting that timing therapies to coincide with immune-active phases may improve outcomes.

5.4. Parameter Sensitivities and Personalized Therapy

The detailed bifurcation maps (see Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 11) highlight a few key parameters that significantly shape the system behavior. The immune recruitment rate (p) and inactivation rate (m) stand out as especially sensitive. Therefore, immunophenotyping tumors for these traits could help predict treatment response. Here is something interesting: boosting the baseline immune influx (s) actually makes the bistability regions bigger. In other words, stronger basic immunity raises the odds of sudden disease progression—a phenomenon observed in certain cancers where robust immune infiltration is linked to a poor prognosis.

Parameters such as immune recruitment (p) and inactivation (m) directly influence the stability of the equilibrium phase. Immunophenotyping these traits could help identify patients likely to experience prolonged dormancy versus those at risk of escape, enabling more tailored interventions. This parameter sensitivity analysis extends the work reviewed by Eftimie et al. [28], who emphasized the importance of parameter estimation in tumor-immune models.

5.5. Comparison with Original Models

Our findings not only support the previous work but also, in some cases, modify the conclusions of earlier major research works: in the context of [8], we reconfirm the existence of the two tumor states, dormant and active, but at the same time we point out that the crucial difference is the Gompertz growth law, which wipes out the stable tumor-free equilibrium, thus altering therapeutic expectations.

In comparison to the work of [10], we assert that both models demonstrate multistability, yet the Gompertz formulation gives rise to intermediate stable states that are absent in the logistic-based approach.

As for [11], both models include chemotherapy; however, our investigation reveals a more intricate bifurcation structure, which includes multistability and treatment-induced oscillations that are exclusive to Gompertz kinetics, thus creating more complexity.

Ultimately, in comparison to [12], their focus on combination therapy contrasts with our analysis, which is confined to chemotherapy. Yet, both studies accentuate the crucial role of nonlinear drug effects in the emergence of complex dynamics.

The mathematical robustness of the bifurcation results is underpinned by the explicit non-degeneracy checks detailed in Appendix B (Assumptions A2–A4 and Remarks A2 and A3), ensuring that the reported limit points, Hopf bifurcations, and cusp singularities correspond to generic codimension-one and codimension-two phenomena in the studied parameter ranges.

6. Conclusions

This investigation presented a comprehensive bifurcation analysis of a tumor-immune competition model that incorporates Gompertz growth kinetics, thus highlighting an important area where the empirical validity of this model for tumor growth is still debated. The major conclusions can be summarized as follows:

- The Gompertz model predicts three distinct regimes (dormant, active, bistable) in the absence of chemotherapy, but it still shows an unstable tumor-free equilibrium, in contrast to logistic models where complete elimination can be obtained mathematically.

- The addition of chemotherapy introduces a high degree of complexity and multistability that can include up to four coexisting steady states together with treatment-induced oscillations. These phenomena are profoundly affected by nonlinear drug saturation effects.

- The parameter mappings reveal that immune recruitment (p) and inactivation (m) rates are highly sensitive, which indicates the existence of possible biomarkers for customizing treatment.

- The model’s dynamical regimes align closely with the three phases of cancer immunoediting: unstable tumor-free equilibria reflect the difficulty of complete elimination; multistability corresponds to the equilibrium phase; and transitions to high-tumor states model escape. This provides a mathematical foundation for immunoediting dynamics and supports the biological plausibility of Gompertz-based tumor-immune modeling, as discussed in reviews of tumor-immune interactions [20,28].

- The singularity at in the standard Gompertz term is both a mathematical artifact and, in practice, a reminder that “zero tumor” is an idealization in the presence of recurrence risk. A smooth regularization, for example replacing by , removes the singularity while retaining Gompertz-like behavior over clinically observable tumor sizes. This also allows a consistent discussion of extinction-type outcomes in deterministic analyses [30,31]. Other authors have introduced a quasi-extinction threshold, e.g., declare clearance when , where represents a clinically undetectable tumor burden; others have adopted a stochastic formulation in which extinction events can occur with nonzero probability.

- While several previous studies have incorporated Gompertz growth into tumor-immune models [19,32,33], our work represents a significant advance through its comprehensive bifurcation analysis, systematic comparison with logistic growth, and detailed investigation of chemotherapy effects including novel phenomena such as intermediate stable states and treatment-induced oscillations.

- Limitations and Future Directions: Although the parameters were extrapolated from laboratory studies, their clinical validation is still required. Future research should consider time delays in drug effects, therapy combinations, and spatial heterogeneity. The fractional-order formulations [18] could be used to describe memory effects in immune responses. Patient data integration would allow for model calibration and validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T.A. and A.A.; Methodology, R.T.A. and A.A.; Software, A.A.; Validation, R.T.A., A.A. and M.Z.S.; Formal Analysis, R.T.A., A.A. and M.Z.S.; Investigation, R.T.A., A.A. and M.Z.S.; Resources, R.T.A. and A.A.; Data Curation, A.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.A. and M.Z.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.A.; Visualization, A.A.; Supervision, A.A.; Project Administration, R.T.A. and A.A.; Funding Acquisition, R.T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2601).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Stability of Tumor-Free Equilibrium in Logistic Model

The dimensionless logistic growth model is:

The Jacobian at the disease-free equilibrium is:

Eigenvalues are and . Thus, the tumor-free state is stable when and unstable otherwise, a stability condition absent in the Gompertz formulation.

Appendix B. Steady-State Analysis and Non-Degeneracy Assumptions

The following appendix provides a rigorous foundation for the bifurcation analysis by stating explicit non-degeneracy conditions (Assumptions A1–A4) that guarantee the scalar reduction is well defined and that the detected bifurcations correspond to standard codimension-one phenomena. These assumptions are satisfied for the parameter ranges considered in the main text, ensuring the validity of the presented bifurcation diagrams and conclusions. Violations of these conditions lead to higher-codimension singularities (e.g., cusps) that are separately identified in two-parameter continuations.

At steady state, . From (A2):

From (4) (for ):

Appendix B.1. Standing Assumptions and Reduction to a Scalar Equation

The steady-state analysis below repeatedly reduces the two equilibrium equations to a single scalar equation in T by writing both nullclines as graphs and and then solving

This reduction is not merely algebraic: it is justified only on a domain where the nullclines are non-degenerate graphs (in the implicit-function-theorem sense). Likewise, identifying limit points (folds) by tangency conditions requires a genericity (second-derivative) non-degeneracy that must be checked or explicitly assumed. Since these assumptions play a central role in the proofs and conclusions, we state them explicitly and delineate the regime in which the arguments apply.

The following analysis relies on several smoothness and non-degeneracy conditions that ensure the bifurcations are generic and the scalar reduction is valid. These are explicitly stated as Assumptions A1–A4 below and are satisfied for the parameter ranges considered in this study. Violations of these conditions correspond to higher-codimension singularities (e.g., cusps) that are separately identified in two-parameter continuations.

Assumption A1

(Admissible state space and parameter signs). We work on the biologically meaningful region and assume

with .

Define

Then, (A2) can be written as .

Assumption A2

(Non-degeneracy of the E-nullcline graph). We restrict attention to the domain

Lemma A1

(Positivity enforces ). If is a positive equilibrium with and , then necessarily . Indeed, from (A2), we have , hence . Consequently, no positive equilibrium can lie on the singular set . Assumption A2 therefore does not exclude any biologically relevant equilibria; it is used only to guarantee that the E-nullcline is a smooth graph in the region where equilibria can occur, so that the scalar reduction is well defined and standard tangency arguments apply.

Remark A1

(How to verify and interpret violations). The function is continuous with and as , so for all sufficiently large T. If crosses zero at some , then has a vertical asymptote at . This does not correspond to an equilibrium (by Lemma A1), but it does mean that global intersection-counting arguments must be restricted to the branch segments where (equivalently ). In computations, this restriction is automatic when we track only positive equilibria.

Lemma A2

(Implicit-function justification of the graph nullclines). Let

- 1.

- For any , the equation has the unique solutionMoreover, on , so the E-nullcline is a smooth graph there.

- 2.

- For any , , hence the T-nullcline is a smooth graph , where

Proposition A1

(Validity of the scalar steady-state reduction). Under Assumptions A1 and A2, the positive equilibria with satisfying (A2) and (A3) are in one-to-one correspondence with roots of

In particular, any argument that counts equilibria by counting intersections of F and G (or zeros of H) is valid only on . If , then blows up and the graph representation (and any conclusions drawn from it) can fail.

Let be the Jacobian of the vector field. We call an equilibrium non-degenerate (hyperbolic) if . This hypothesis is required whenever we invoke linearization to classify stability or robustness of equilibria.

Assumption A3

(Hyperbolicity away from bifurcation). Whenever we claim local uniqueness/stability classification away from bifurcation points, we assume at the equilibrium(s) under consideration.

Also, from (A2):

Appendix B.2. Properties of F(T)

Lemma A3

(Properties of F). The function satisfies:

- 1.

- and .

- 2.

- 3.

- The equation has: (i) no positive solution if ; (ii) one double positive solution if ; (iii) two distinct positive solutions if (a local minimum then a local maximum of F).

Appendix B.3. Properties of G(T)

Recall and from Assumption A2. On , we have .

Lemma A4

(Properties of G). On , the function satisfies:

- 1.

- and .

- 2.

- 3.

- G has at most one critical point in .

- 4.

- If , then for all , so G is (weakly) decreasing on .

- 5.

- If and contains the critical point, then G has exactly one interior maximum at

Appendix B.4. Maximum Number of Intersections F(T)=G(T)

Theorem A1

(Maximum number of positive steady states (correct)). The system (3) and (4) admits at most five positive steady states with .

Proof.

Positive steady states correspond to positive solutions of (A7). By the lemmas above, G has at most one critical point on , while F has at most two critical points on . Hence, the difference

has at most four critical points on , so H can have at most five distinct zeros there. Each zero corresponds to a positive steady state. □

Appendix B.5. Limit Points and Generic Saddle-Node Conditions

Limit points occur when and , i.e., when

Equilibria satisfy the scalar steady-state equation

where and is given by (A9). Since v enters linearly in H, one may solve explicitly for v as a parametric equilibrium branch in the -plane:

A (generic) fold point along this branch is characterized by a vertical tangent; equivalently,

Differentiating (A16) gives

so the fold condition (A17) becomes an explicit scalar equation in T using (A11). This formulation is equivalent to the usual fold conditions and , because for all , and hence the implicit-function transversality with respect to v is automatic.

The conditions and (equivalently and ) identify tangency of the nullclines and hence a degeneracy of the equilibrium curve. To claim a generic (codimension-one) saddle-node bifurcation, one must also exclude higher-order contact.

Assumption A4

(Generic fold (saddle-node) non-degeneracy). At any candidate limit point with and satisfying and , we assume

In our model, the transversality condition is automatic for since

so the only remaining genericity check is the second-order non-degeneracy

If instead , then the tangency has at least cubic contact and the local bifurcation is not a standard fold; one expects a higher-codimension singularity (e.g., cusp) and the fold-based conclusions (local two-branch picture, robustness under perturbation, etc.) to require a separate analysis.

Remark A2

(Normal-form interpretation). Assumption A4 is precisely the non-degeneracy required for a saddle-node bifurcation in the full two-dimensional ODE. When the Jacobian has a simple zero eigenvalue, a one-dimensional center-manifold reduction yields the normal form

where corresponds to and corresponds to . This makes the notion of “non-degenerate fold” transparent and verifiable in terms of derivatives of H.

Concretely, writing and , the equilibrium condition admits the Taylor expansion

since at the fold. After a smooth rescaling of x (and time) this is equivalent to the saddle-node normal form above, with and ; thus, gives a genuine unfolding in v, and guarantees the generic quadratic tangency.

Remark A3

(Degenerate folds and cusps (codimension two)). A fold (limit point) is generic when , , and (Assumption A4). When instead, , the tangency has higher-order contact (cubic or higher), and the equilibrium curve is no longer locally described by the standard saddle-node normal form. In the reduced scalar picture, this corresponds to the cusp condition

which is the codimension-two mechanism organizing the creation/annihilation of pairs of folds. This is consistent with the cusp/degenerate points detected in the two-parameter continuations reported in the main text: away from such codimension-two points, the computed limit points satisfy and are therefore non-degenerate folds.

Appendix B.6. Special Case v = 0 (No Chemotherapy)

When , (A8) becomes , which is strictly decreasing on . Therefore, if , the system has at most two positive steady states.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doostmohammadi, A.; Jooya, H.; Ghorbanian, K.; Gohari, S.; Dadashpour, M. Potentials and future perspectives of multi-target drugs in cancer treatment: The next generation anti-cancer agents. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N. Cancer treatment: New drugs and strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockne, R.C.; Scott, J.G. Introduction to mathematical oncology. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2019, 3, CCI-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.R.; Quaranta, V. Integrative mathematical oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, R.P.; McElwain, D.S. A history of the study of solid tumour growth: The contribution of mathematical modelling. Bull. Math. Biol. 2004, 66, 1039–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, T.O.; Cheng, Y.C.; Graser, C.; Nicol, P.B.; Temko, D.; Michor, F. Computational approaches to modelling and optimizing cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2023, 1, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V.A.; Makalkin, I.A.; Taylor, M.A.; Perelson, A.S. Nonlinear dynamics of immunogenic tumors: Parameter estimation and global bifurcation analysis. Bull. Math. Biol. 1994, 56, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, D.; Panetta, J.C. Modeling immunotherapy of the tumor-immune interaction. J. Math. Biol. 1998, 37, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pillis, L.G.; Radunskaya, A.E.; Wiseman, C.L. A validated mathematical model of cell-mediated immune response to tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 7950–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Á.G.; Seoane, J.M.; Sanjuán, M.A.F. A validated mathematical model of tumor growth including tumor-host interaction, cell-mediated immune response and chemotherapy. Bull. Math. Biol. 2014, 76, 2884–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirtseva, I.; Chukhareva, A.; Ryashko, L. Modeling and analysis of nonlinear tumor-immune interaction under chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022, 45, 7983–7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Tian, T.; Zhang, X. A mathematical model of cell-mediated immune response to tumor. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzekry, S.; Lamont, C.; Beheshti, A.; Tracz, A.; Ebos, J.M.; Hlatky, L.; Hahnfeldt, P. Classical mathematical models for description and prediction of experimental tumor growth. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, L. A Gompertzian model of human breast cancer growth. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 7067–7071. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, H.; Jaafari, H.; Dobrovolny, H.M. Differences in predictions of ODE models of tumor growth: A cautionary example. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari Laleh, N.; Loeffler, C.M.; Grajek, J.; Stanková, K.; Pearson, A.T.; Muti, H.S.; Trautwein, C.; Enderling, H.; Poleszczuk, J.; Kather, J.N. Classical mathematical models for prediction of response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, D. Dynamics and Stability of a Fractional-Order Tumor-Immune Interaction Model with BD Functional Response and Immunotherapy. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Onofrio, A. A general framework for modeling tumor-immune system competition and immunotherapy: Mathematical analysis and biomedical inferences. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2005, 208, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Onofrio, A. Metamodeling tumor-immune system interaction, tumor evasion and immunotherapy. Math. Comput. Model. 2008, 47, 614–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serre, R.; Benzekry, S.; Padovani, L.; Meille, C.; André, N.; Ciccolini, J.; Barlesi, F. Mathematical modeling of cancer immunotherapy and its synergy with radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4931–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledzewicz, U.; Munden, J.; Schättler, H. Scheduling of angiogenic inhibitors for Gompertzian and logistic tumor growth models. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2009, 12, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Abdullah, J.Y.; Ahmad Satmi, A.S.; Genisa, M.; Majeed, A.; Nadeem, T. Mathematical Modeling and Analysis of Tumor Growth Models Integrating Treatment Therapy. Math. Comput. Appl. 2025, 30, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarte, O.; Ertveldt, T.; Meulewaeter, S.; Keyaerts, M.; Dewitte, H.; Verbeke, R.; Lentacker, I.; Breckpot, K.; Barbe, K. Gompertz Model Use in Tumor Growth Curves Analysis. SSRN 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.N. A mechanistic, predictive model of dose-response curves for cell cycle phase-specific and-nonspecific drugs. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Kareva, I.; Luddy, K.A.; O’Farrelly, C.; Gatenby, R.A.; Brown, J.S. Predator-prey in tumor-immune interactions: A wrong model or just an incomplete one? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 668221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhooge, A.; Govaerts, W.; Kuznetsov, Y.A.; Meijer, H.G.; Sautois, B. New features of the software MatCont for bifurcation analysis of dynamical systems. Math. Comput. Model. Dyn. Syst. 2008, 14, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftimie, R.; Bramson, J.L.; Earn, D.J.D. Interactions Between the Immune System and Cancer: A Brief Review of Non-spatial Mathematical Models. Bull. Math. Biol. 2011, 73, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, S. Nonlinear Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Castorina, P.; Zappalà, D. Tumor Gompertzian growth by cellular energetic balance. arXiv 2004, arXiv:q-bio.CB/0407018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheldon, T.E. Mathematical Models in Cancer Research; Hilger Publishing: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- de Vladar, H.P.; González, J.A. Dynamic response of cancer under the influence of immunological activity and therapy. J. Theor. Biol. 2004, 227, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itik, M.; Banks, S.P. Chaos in a three-dimensional cancer model. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2010, 20, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.