Abstract

The in-image machine translation task involves translating text embedded within images, with the translated results presented in image format. While this task has numerous applications in various scenarios such as film poster translation and everyday scene image translation, existing methods frequently neglect the aspect of consistency throughout this process. We propose the need to uphold two types of consistency in this task: translation consistency and image generation consistency. The former entails incorporating image information during translation, while the latter involves maintaining consistency between the style of the text image and the original image, ensuring background coherence. To address these consistency requirements, we introduce a novel two-stage framework named HCIIT (High-Consistency In-Image Translation), which involves text image translation using a multimodal multilingual large language model in the first stage and image backfilling with a diffusion model in the second stage. Chain-of-thought learning is employed in the first stage to enhance the model’s ability to effectively leverage visual information during translation. Subsequently, a diffusion model trained for style-consistent text–image generation is adopted. We further modify the structural network of the conventional diffusion model by introducing a style latent module, which ensures uniformity of text style within images while preserving fine-grained background details. The results obtained on both curated test sets and authentic image test sets validate the effectiveness of our framework in ensuring consistency and producing high-quality translated images.

Keywords:

multi-modal machine translation; in-image translation; text image translation; diffusion model MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

With globalization on the rise, the demand for machine translation in our lives is increasing significantly. Beyond conventional text translation, we frequently encounter instances where text embedded within images requires translation, spanning from movie posters and children’s picture books to various everyday situations. Currently, research focused on translating text within images, such as text image translation (TIT) [1,2], aims to precisely convert text from source images into the desired target text, rather than integrating the translated text back onto the source images. However, in practical scenarios, there is an increasing demand for displaying the translated text in image form to offer a more intuitive representation. We refer to this task of rendering text back onto images as in-image translation (IIT) in this work.

Commercial systems such as Google and Aliyun typically present results in image format, focusing primarily on translations for everyday practical scenarios. In these scenarios, the emphasis lies on conveying the placement and significance of the translated text within the image, rather than prioritizing the visual smoothness of the rendered image. Qian [3] has proposed the AnyTrans framework to improve the fluency of translated images. However, all these approaches overlook the consistency assurance in the process of IIT. We emphasize that in conducting IIT, the following consistencies should be ensured to meet the requirements of most scenarios:

- Translation Consistency: Image information should be integrated into the translation process for improving translation accuracy. While previous studies on multimodal machine translation [4,5,6,7,8] have primarily focused on enhancing text translation quality by leveraging image information during the text translation process, text translation accompanied by images is relatively uncommon in real-life scenarios. In IIT, text is always accompanied by an image, making image information particularly crucial during the translation process.

- Image Generation Consistency: Image generation consistency consists of two dimensions. The first is background coherence, which refers to the smoothness and seamless integration between the generated text and its background. AnyTrans has already achieved strong performance in this aspect. However, in certain scenarios—such as film poster translation and children’s picture book translation—it is essential for the visual style of the target text to remain consistent with that of the source text. Therefore, we propose that the generation of target images should also maintain font style consistency. This form of consistency encompasses elements such as font type and color in text-containing images. Existing methods like AnyTrans infer the style of the generated text image from the surrounding context of the rendered scene. A more suitable approach would be to ensure consistency with the style of the original source text image.

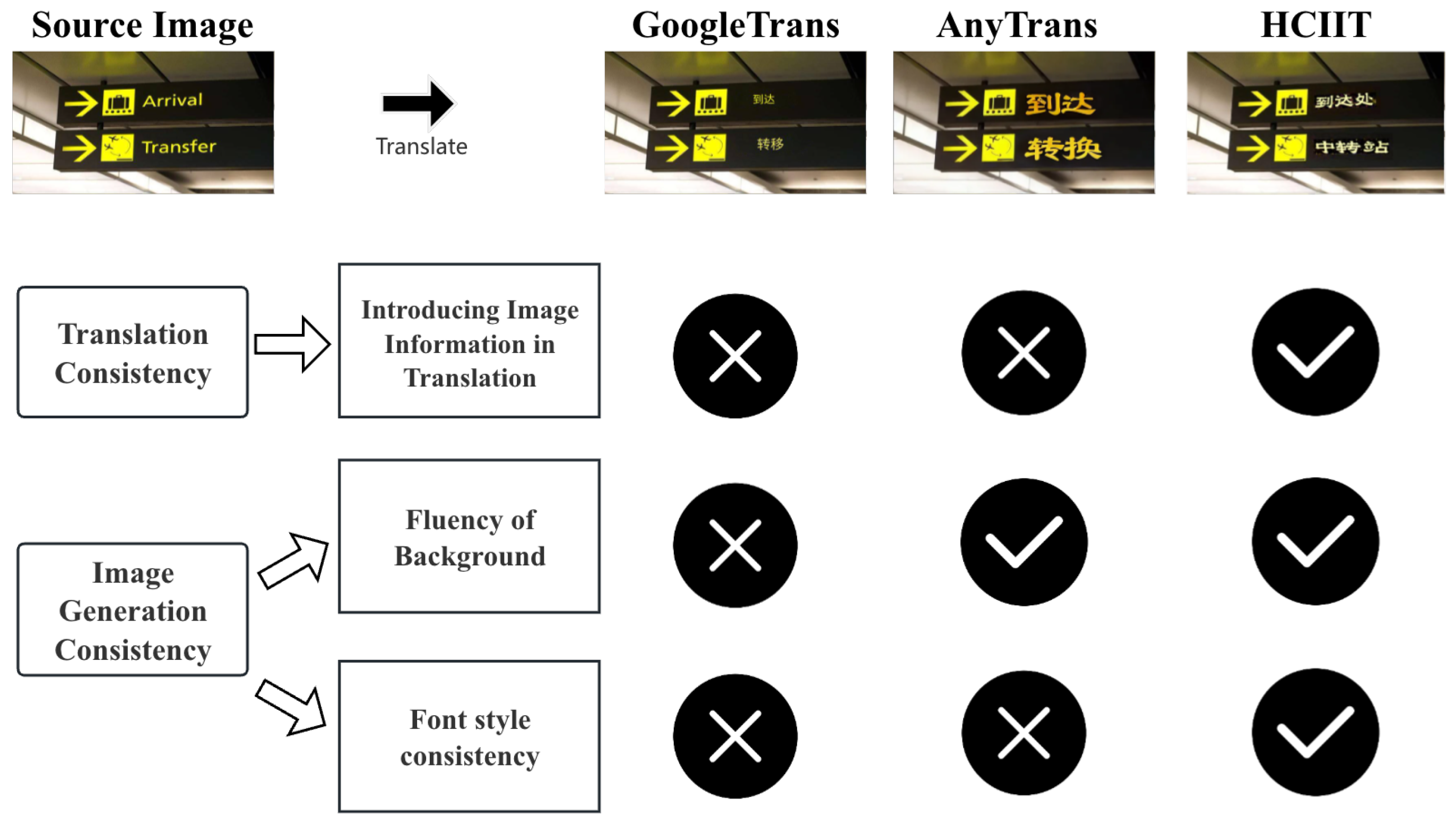

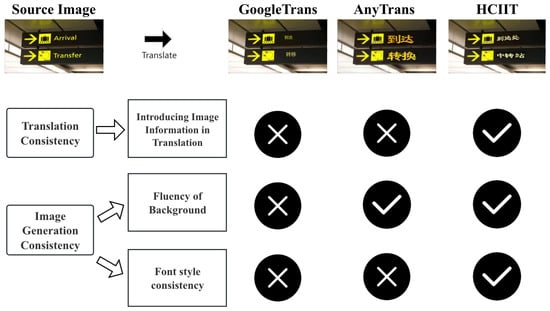

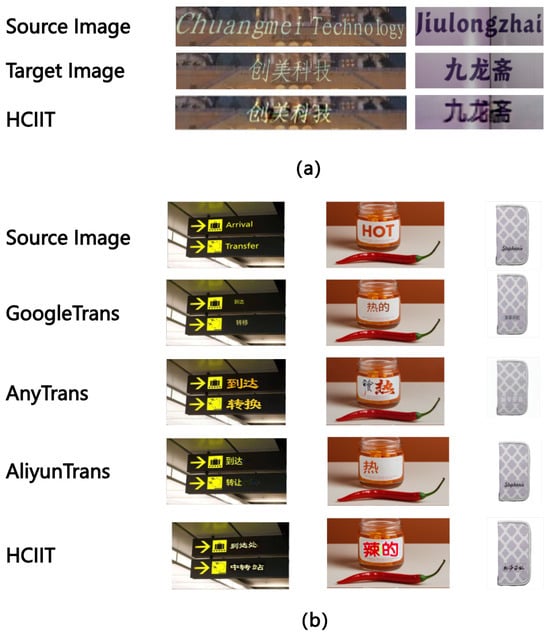

As shown in Figure 1, the existing methods are unable to fully meet these consistency rules, so we further propose a two-stage framework for IIT called HCIIT: (1) TIT based on a multimodal multilingual large language model (MMLLM): In this stage, we leverage simple chain-of-thought (CoT) learning to ensure effective utilization of image information during the translation process, thereby enhancing translation accuracy. (2) Image backfilling based on diffusion model: In this stage, we use a diffusion model to generate images. This method can produce high-quality images, ensuring background coherence. However, existing diffusion models still have certain issues in text image generation and struggle to generate stylistically consistent text images. Therefore, we introduce a style latent module into the structural network of the existing text-controlled diffusion model to enhance the quality of generated text images and enable more effective style learning. Additionally, since real translation image pairs are scarce in real-life settings, we generate synthetic data with different styles (including various fonts, text sizes, colors, and italicization) for style consistency learning. By evaluating our method on both synthetic test sets and real image test sets, we observed superior translation performance and improved style consistency compared to previous commercial systems and methods. In essence, our work presents three key contributions:

Figure 1.

Comparison of the performance of our method, AnyTrans, and online systems in terms of translation consistency and image generation consistency. “Transfer” in the image should be translated as transfer station/transit not convert/shift. The style of the target image should be consistent with the source image.

- We underline current inadequacies in maintaining consistency in in-image translation tasks, with a specific emphasis on ensuring consistency in translation and image generation.

- We introduce a simple two-stage framework that effectively addresses prevalent issues in existing tasks of text translation on images, such as inaccuracies in translation, inconsistency in style, and blurriness in backgrounds.

- We modify the existing structural network of diffusion model to enhance its ability to generate image-with-text content in a consistent style. In addition, we curate a few style-consistent pseudo-parallel image pairs for training. Our framework yields satisfactory and reliable results in ensuring consistent style preservation.

2. Related Work

2.1. Text Image Translation

Text image translation (TIT) [1,2,9,10], which is a subtask of IIT, aims to translate text on images into the target language, primarily returning the translation in textual form. However, textual outputs are evidently less intuitive than image-based outputs, which can provide users with a clear understanding of the text’s position and meaning. AnyTrans returns translation results in image form, utilizing a multimodal multilingual large model for translation and then employing Anytext to render the text onto images. However, it does not focus on integrating image information during translation, and it also does not maintain consistent text styles. Our framework addresses these limitations. Current methods for IIT still rely on cascaded approaches, while some have proposed a method like Translatotron-V [11] to achieve end-to-end translation, primarily for text images with solid backgrounds. A crucial future challenge is achieving high-quality end-to-end translation for complex text images in natural scenes with intricate backgrounds.

2.2. Text Image Generation

In recent years, research in the field of computer vision has not only continued to advance in tasks such as image understanding, decomposition, and denoising [12,13,14,15,16] but has also gradually expanded from traditional image processing toward a deeper exploration of generative image techniques. In our framework, we utilize text-to-image diffusion models to generate target images. However, existing methods often struggle to produce high-quality text images. Several efforts have been made to enhance the text generation capabilities of diffusion models: GlyphDraw [17] introduces glyph images as conditions to improve text image generation. GlyphControl [18] further incorporates text position and size information. TextDiffuser [19] constructs a layout network to extract character layout information from the text prompt, generating a character-level segmentation mask as a control condition. TextDiffuser-2 [20] builds upon TextDiffuser by unleashing the power of language models for text rendering. Anytext [21] transforms the text encoder through the integration of semantic and glyph information. Additionally, it incorporates an OCR encoder to supervise text generation at a more granular level. All of these methods mentioned so far struggle to generate stylistically consistent images. Building upon Anytext, we further modified the framework by incorporating a style auxiliary module to ensure the consistency of text styles in the generated images.

3. Methodology

In this section, we will initially present our two-stage framework, designed to ensure consistency in IIT. Subsequently, we will provide detailed explanations of the methods employed in each of the two stages.

3.1. High-Consistency In-Image Translation Framework

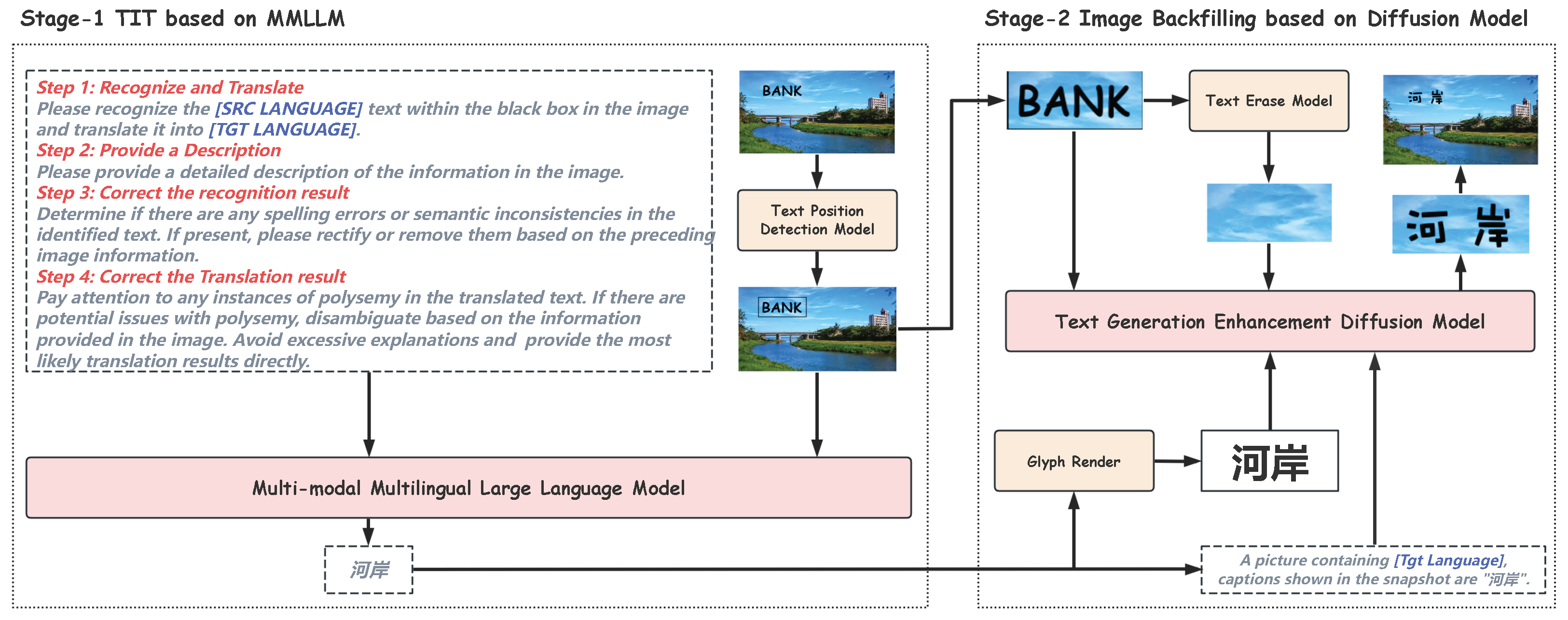

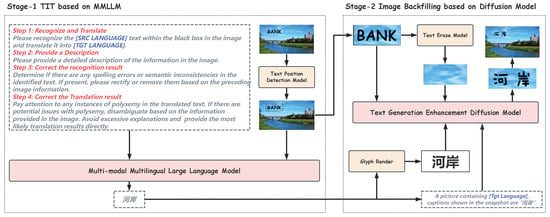

We propose a two-stage methodology to ensure high consistency in IIT, as depicted in Figure 2: (1) Text image translation based on a multimodal multilingual large language model. For a source image S, the initial step involves text position recognition, which yields N pieces of information regarding the locations of text elements. These details are presented in the form of text boxes and denoted as . Next, we individually feed source image S and the position of each text element into a multimodal multilingual large language model to accomplish text recognition and translation, resulting in the translated output . This large language model must support the source and target languages involved in our translation process. (2) Image backfilling using a stable diffusion model. In this stage, we utilize a diffusion model to generate an image T containing the translated text Y while maintaining the style consistent with S. We transition the outputs from the first stage to the four inputs of the second stage: (1) For each translated text in Y, we create an image rendered in a standard font. (2) Simultaneously, based on , we generate a COT prompt through rules to guide the diffusion model in generating the corresponding image. (3) Using the positional information , we extract text from the image to obtain image bounding box . (4) Additionally, we remove the text in to derive the background image and then utilize this information to generate images corresponding to and . Finally, we fill in these using position to obtain the ultimate translated target image T.

Figure 2.

The process of two-stage in-image translation. Our framework consists of two stages, comprising an MMLLM-based TIT and a diffusion-model-based image backfilling. In Stage 1, the Chinese text shown at the bottom represents the translated Chinese output. In Stage 2, the enlarged Chinese text at the bottom corresponds to the glyph image of the translated Chinese text.

3.2. Stage 1: TIT Based on MMLLM

The first stage focuses on text recognition and translation on images using MMLLMs. We employ this model to accomplish the task, leveraging its advanced image understanding capabilities. However, we observe that when applied to image translation, these models tend to produce literal translations. For instance, when confronted with the word “Bank” in the image in Figure 2, a direct translation would yield “financial institution”. However, a more accurate translation in the context of the image would be “riverbank”. Therefore, while MMLLMs excel at image comprehension, they struggle to effectively incorporate image information for accurate translation. Huang et al. [22] also noted the misalignment between the general comprehension abilities and translation comprehension abilities of LLMs. To address this limitation in our framework, we adopt a COT learning approach, which compels the model to generate the most probable translation results based on its comprehension of the image. The prompt shown in the image is a condensed illustration, yet the overall workflow remains complete. It consists of four primary steps: First, detection and translation, which extract the text from the image and render it into the target language. Second, a comprehensive and detailed description of the image. Third, refinement of the recognized text based on the description provided in the second step. Fourth, refinement of the translated text using the same description, taking into account lexical ambiguity and resolving it using information from the image whenever possible, with only the final translated result presented. All these steps together constitute our instruction set, denoted as . For each pieces in P, we feed , along with the image S and the corresponding text location information , into the large language model, yielding the final output :

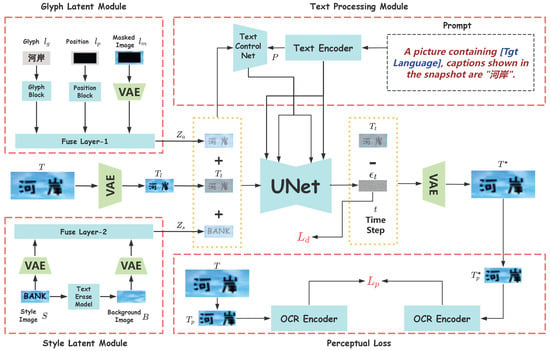

3.3. Stage 2: Back-Filling Based on Diffusion Model

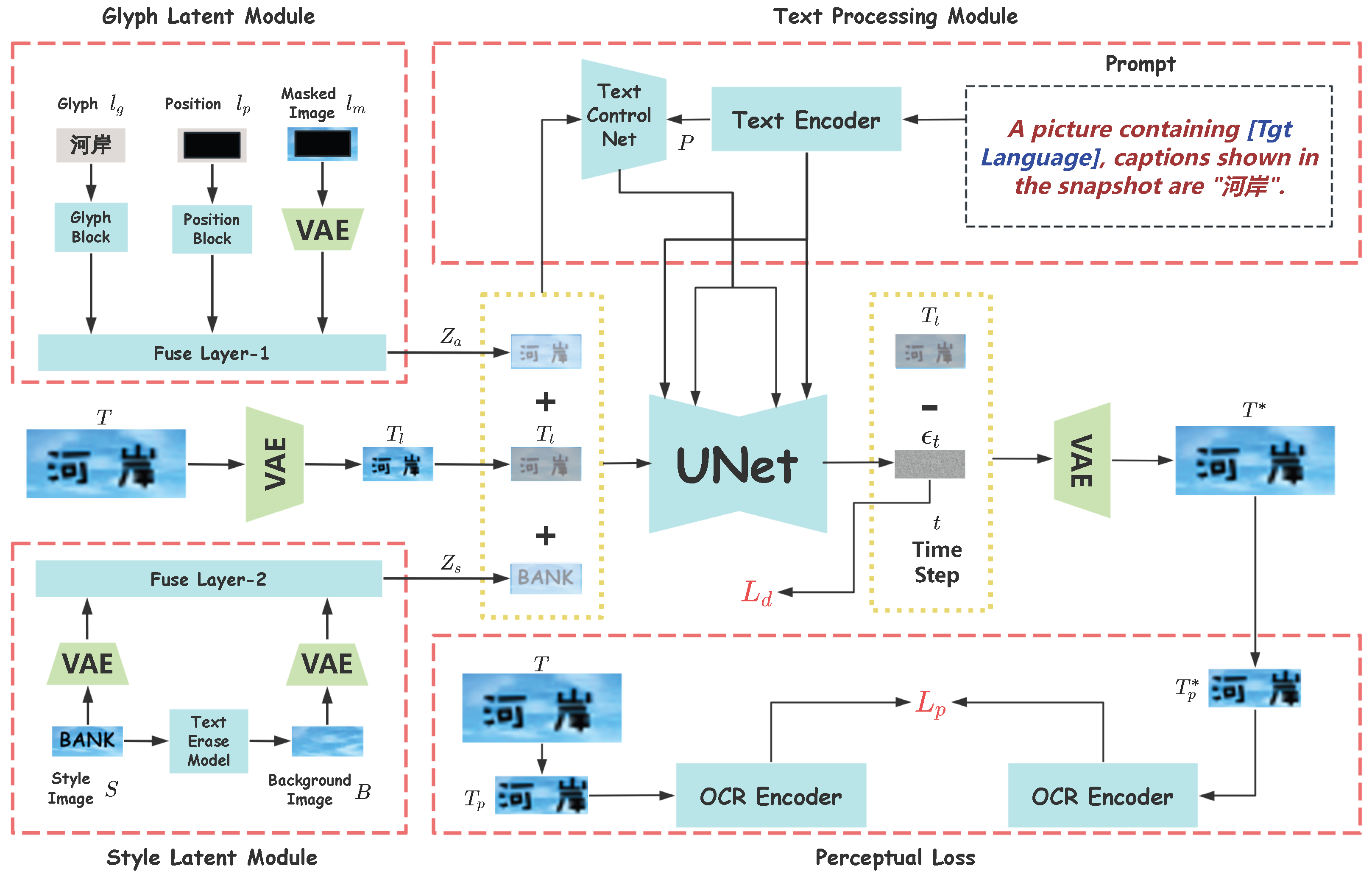

In the second stage, we employ a diffusion model with text generation enhancement to complete the translation results as shown in Figure 3. Diffusion models can generate high-quality images based on descriptions in their current state, but their performance in images with text generation is not satisfactory. Some research has focused on improving the quality of images with text generation, but in the context of IIT, these efforts still do not fully meet the requirements, which include maintaining style consistency and background coherence. Therefore, in this section, we modify the structural architecture of the diffusion model to generate images with consistent stylistic characteristics while preserving the background as faithfully as possible.

Figure 3.

An overview of stage 2. We incorporated a style latent module as a constraint for the Text ControlNet. All Chinese text appearing in the figures corresponds to the Chinese translation of “bank river.”

3.3.1. Style Latent Module

If we have pairs of stylistically consistent images, we can input the target image T along with its corresponding style image S as conditions into the text-controlled diffusion process, enabling the model to reference the style of the text in the style image while generating the image. However, in real-life scenarios, it is rare to have such pairs of images that are both stylistically and background-consistent, making the collection of genuine images a costly endeavor. Therefore, we resort to fabricating pairs of style-consistent images to facilitate training, a method we will elaborate on in the experimental section. Additionally, to maintain background consistency as much as possible, we eliminate text from the style image S to obtain pure background information B, which is then fed into the model. We employ a VAE decoder D for downsampling both the style image S and the background image B, followed by a convolutional fusion layer g to merge these representations and obtain :

3.3.2. Glyph Latent Module

In order to enable the model to generate text with precise positioning and higher quality, current methods typically incorporate additional information to enhance the model’s capabilities. Consistent with Anytext, and tailored to the characteristics of translation tasks, we adopted three auxiliary conditions: glyph , position , and masked image . Glyph represents a text image rendered with a standard font, position information denotes the location of the text on the image indicated by a solid black rectangle, and the masked image signifies the background information excluding the text, indicating the area in the image that should be retained during the diffusion process. During the inference stage, both the position information and the masked image are derived from the source image (style image) S. We employ several stacked convolutional layers to construct mapping layers G and P for downsampling glyph and position , utilize a VAE decoder D for downsampling masked image , and then integrate this information using a convolutional fusion layer f to obtain :

3.3.3. Text-Controlled Diffusion Pipeline

Upon completing the preparation of the style-background information auxiliary module and the text generation auxiliary module, we integrate them as conditions into the text-controlled diffusion pipeline. For an image , we encode it using a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to obtain latent space feature . Consistent with the diffusion model, we incrementally add randomly generated Gaussian noise to at each time step t, creating a noisy latent image . By using the representations of the style-background auxiliary module and the text generation auxiliary module as conditions, along with the prompt M and time step t, text-controlled diffusion models use a network to predict the noise. The text-controlled diffusion loss is

We also use a text perceptual loss used in Anytext to further improve the accuracy of text generation. We employ the VAE decoder to reconstruct , yielding . Subsequently, we utilize character position information to crop T and , resulting in and . These cropped images are then encoded using the encoder of the PP-OCRv3 (https://github.com/yinjiuzui/PaddleOCR (accessed on 12 January 2025)). model, producing their respective representations m and . The corresponding loss function is defined as

where represents the coefficient of the diffusion process. By incorporating the , the model can place greater emphasis on the accurate generation of characters. The final loss is expressed as:

is used to adjust the weight between two loss functions.

4. Experiments

In this section, we will progressively introduce the experimental dataset, settings, baselines, and the experimental results and analysis.

4.1. Datasets

To test the effectiveness of our first stage in integrating image information during translation, we chose the CoMMuTE [23] dataset and MTIT6 [3] for evaluation. CoMMuTE is specifically designed to address ambiguity in text translation by incorporating images. We also extracted a few real images from the OCRMT30K dataset and generated a few images utilizing by text-to-image tools for testing. MTIT6 [3] is a comprehensive multilingual text image translation test dataset, assembled from ICDAR 2019-MLT [24] and OCRMT30K [2]. This dataset encompasses six language pairs: English-to-Chinese, Japanese-to-Chinese, Korean-to-Chinese, Chinese-to-English, Chinese-to-Japanese, and Chinese-to-Korean. Each language pair features approximately 200 images.

In the second stage, we needed to construct pseudo image pairs to complete the experiment. Building upon text synthesis technology, we created stylistically consistent cross-lingual text. To ensure style diversity, we incorporated more than 20 font styles and randomly selected text colors, sizes, deformations, and other attributes during text generation. For backgrounds, we randomly cropped images to use as backgrounds. As for text content, to ensure closer resemblance of real images, we chose parallel corpora from the dataset of the TIT task. Some examples can be found in Figure 4. We conducted experiments on French–English (Fr-En) and English–Chinese (En-Zh and Zh-En) directions. We generated 100,000 pairs of parallel images for training and 200 pairs for testing in each of the directions.

Figure 4.

A few examples of the constructed pseudo-parallel En-Zh image pairs. To ensure stylistic diversity, we randomly selected various fonts, colors, and degrees of slant variation.

4.2. Baselines

We compared our method with existing online systems and AnyTrans. AnyTrans is a two-stage framework for text translation on images that does not require training. It utilizes large language models for translation and employs AnyText for backfilling. For online systems, we selected industry-leading Google Image Translate (GoogleTrans) (https://translate.google.com (accessed on 30 January 2025)), Alibaba Cloud Image Translate (AliyunTrans) (https://mt.console.aliyun.com (accessed on 28 January 2025)), and Youdao Image Translation (YoudaoTrans) (https://fanyi.youdao.com (accessed on 26 January 2025)) for comparison.

For the translation baselines, we selected the M2M100 [25] 1.2b model, the NLLB [26] 3.3b model, and pure text-based large language models for comparison.

4.3. Settings

We utilized the Qwen2.5-VL [27] model, a multimodal multilingual large model known for its strong capabilities in Chinese, English, French, and other languages, as well as its robust multimodal abilities. This model ranks highly on multiple multimodal large model testing leaderboards. All experiments were conducted on 4 V100 GPUs. In the second stage, our experimental setup involved a learning rate of , a batch size of 6, and training for 15 epochs. We set the parameter in the loss function to 0.01, consistent with Anytext.

As for the Text Erase Model, we employed artificially constructed images that inherently possessed backgrounds devoid of text from the outset. Thus, during training, we directly utilized preexisting background images. In real image testing scenarios, we employed AnyText to carry out the text removal process. In cases where the removal efficacy was subpar, we resorted to employing image editing software for further refinement.

For evaluation metrics, we used the BLEU metric [28] and the COMET metric [29] to evaluate the results of machine translation. On the constructed test set with target images, we utilized image similarity metrics such as SSIM [30] and L1 distance. We also employed evaluation methods involving multimodal large models and human assessments.

4.4. Results and Analysis

4.4.1. Translation Results

We present the results of TIT in Table 1 and Table 2, juxtaposing them with the performance of traditional machine translation models, NLLB200 and M2M-100, as well as large language models. The latter includes Qwen1.5 [31], which serves as the primary model in AnyTrans, the most effective method for the current TIT task.

Table 1.

Translation results on En-Zh, Zh-Ja, Zh-Ko directions of the MTIT6 dataset. The numbers in bold in the table indicate the best results.

Table 2.

Translation results on En-Fr, En-De, and En-Zh directions of CoMMuTE datasets. The numbers shown in bold in the table indicate the best results.

All these methods employ traditional OCR techniques that separate text recognition from the translation process, potentially neglecting image information during translation. In addition, we include the results of direct recognition and translation using Qwen2.5-VL, as well as those enhanced by our COT method.

In Table 1, we present the COMET score of translation results for Chinese, English, Japanese, and Korean on the MTIT6 dataset. The results demonstrate that translations generated by multimodal large models outperform those by traditional models and pure text-based large models. This improvement can be attributed to the integration of image information.

However, the performance gains from our COT method over direct recognition and translation with Qwen2.5-VL are relatively small, with some language directions even showing a decline on the MTIT6 dataset. This might be due to the limited occurrence of ambiguous terms in the MTIT6 dataset, where standard instructions suffice for effective translation.

To further validate our approach, we conducted comparisons on the CoMMuTE dataset in Table 2. The CoMMuTE dataset is specifically designed to address the phenomenon of lexical ambiguity in image-based translation. Here, our COT method achieved significant improvements that demonstrated superior translation efficacy. These results underscore our method’s ability to leverage image data to effectively resolve ambiguities.

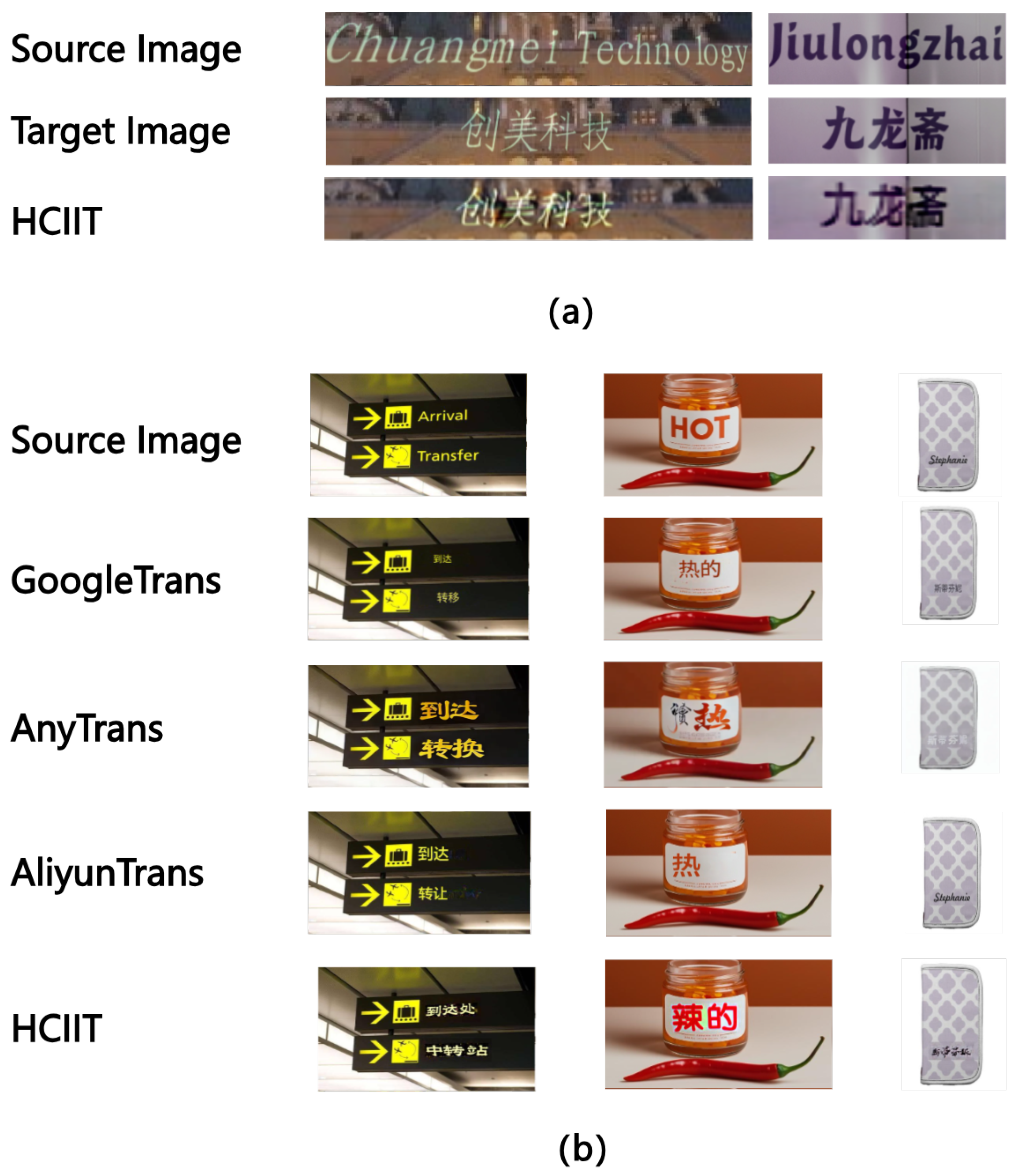

4.4.2. Results on Image Generation

To assess the style consistency of generated images, we constructed a pseudo test set for evaluation. We conduct tests in three directions across two language pairs: English–French and English–Chinese. We tested the effectiveness of our method and existing methods on this dataset, comparing it with online systems such as AliyunTrans and YoudaoTrans and recent methods like AnyTrans. (We did not compare our method with GoogleTrans as they do not offer an official image translation API. GoogleTrans also falls short in terms of consistency, as demonstrated in the case study.) Within the fabricated dataset, due to the presence of our curated reference images, we can gauge the textual style consistency to some extent by evaluating the image similarity between the generated images and the designated reference images. As shown in Table 3, it is observed that the performance of AnyTrans is subpar, possibly due to AnyTrans predominantly relying on Anytext, which may not perform well when generating text images with large text regions in our synthesis datasets. Our model is trained specifically on this type of data, resulting in superior performance. In comparison to online systems, our method also yields favorable results. This is because these systems do not consider style consistency during translation, leading to lower image similarity. Some examples can be found in Figure 5a.

Table 3.

Our approach, AnyTrans, and several online systems’ results on the synthesis parallel corpus dataset. AliyunTrans does not support the Fr-En translation direction. The numbers shown in bold in the table indicate the best results.

Figure 5.

Case study on En-Zh in-image translation on (a) constructed images and (b) real images with our method, AnyTrans, GoogleTrans, and AliyunTrans.

In the style latent module, we incorporate not only a style image but also a background image, with the goal of enabling the model to better preserve the original background information. To validate the effectiveness of this design, we conducted a simple ablation study in which the background image was removed. The corresponding results are reported in Table 4. As shown, performance consistently degrades in both the En → Zh and Zh → En directions when background information is excluded, indicating that incorporating background cues contributes positively to the overall performance.

Table 4.

Comparison of results without background Information on En-Zh and Zh-En directions. The numbers shown in bold in the table indicate the best results.

Both our method and AnyTrans are based on diffusion models. While diffusion models generally achieve better performance in image generation and style consistency, their inference latency has long been recognized as a limitation. Commercial systems are typically more efficient than our approach and AnyText, as they do not rely on stable diffusion models. Therefore, for applications that only require basic image translation without strict stylistic constraints, these faster commercial solutions may be more suitable. We also compared the inference time of our method with AnyTrans by measuring the average time required to generate 75 images. Our approach exhibits slightly higher latency than AnyTrans, which we attribute primarily to the additional computation introduced by the style latent module.

4.4.3. Case Study

We also applied our method to real datasets. As shown in Figure 5b, we present the results of En-Zh translation, comparing them with Google Translate, AnyTrans, and Aliyun Translate. In terms of translation consistency, it was observed that other methods exhibit some discrepancies, for instance, translating “Hot” as “scorching” instead of the correct “spicy”. AnyTrans shows improvements compared to online systems as it uses text features during translation but does not emphasize the integration of image information. In contrast, our method demonstrates stronger integration of image context during translation.

Regarding text image generation consistency, it is apparent that commercial online systems tend to remove the original text from the image and render the new text in a standard font, leading to incoherence between the text and the background. AliyunTrans sometimes does not translate the text, possibly due to failed OCR. Although AnyTrans generally maintains relatively consistent backgrounds, its performance in text style consistency can sometimes be poor. This is because it fills text based on image background information, which can sometimes introduce additional elements. Our method demonstrates superior performance in text image style consistency, while the coherence of the background may sometimes be compromised.

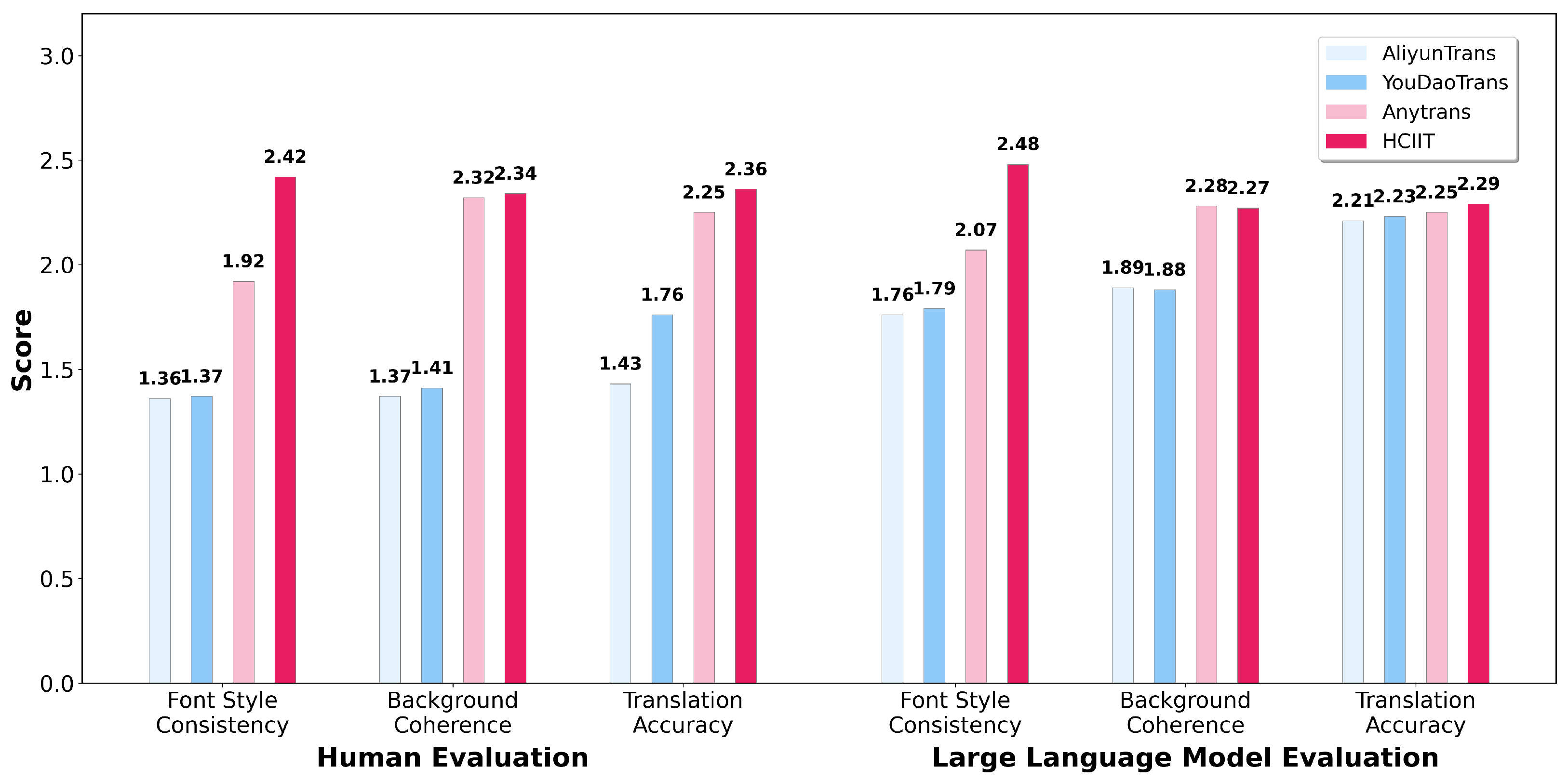

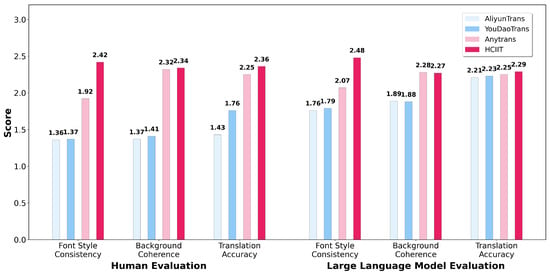

4.4.4. Human Evaluation and Large Language Model Evaluation

We also randomly selected 75 images from real and fabricated datasets for manual assessment and evaluation using GPT-4o. Our evaluation metrics comprised three components: translation accuracy, background coherence, and font style consistency. Each metric has three levels, with higher scores indicating better performance in that aspect:

- (1)

- Translation Consistency:

- Point 1: Failure to recognize the text, or the text is recognized but the translation contains significant inaccuracies and is completely irrelevant.

- Point 2: The text can be recognized and the translation is generally relevant; however, partial errors exist, or insufficient integration of image information leads to ambiguous translations.

- Point 3: The text is correctly recognized and the translation is completely accurate, effectively integrating image information. All text is displayed correctly without any issues.

- (2)

- Text Style Consistency:

- Point 1: Low text style consistency. The text style is highly inconsistent, with noticeable variations in color, font, thickness, and other visual attributes.

- Point 2: Medium text style consistency. Partial consistency is observed, where some elements such as color, font, or thickness remain consistent.

- Point 3: High text style consistency. The text style is nearly entirely consistent; color, font, and thickness match well, and relevant text details are highly uniform.

- (3)

- Background Coherence:

- Point 1: Low coherence. Clear boundaries exist between the text and the background, resulting in a strong sense of layering.

- Point 2: Medium coherence. The text blends reasonably well into the background without distinct boundaries.

- Point 3: High coherence. The text and background are seamlessly integrated; the background appears clear and natural with no visible boundaries.

We selected five graduate students with strong proficiency in both English and Chinese to conduct the annotations. As depicted in Figure 6, diffusion-based methods exhibit good background coherence, yet they still encounter some instances of generation failures. However, commercial systems demonstrate weak background coherence but maintain a level of stability. Manual and large language model evaluations consistently demonstrate favorable results for our method, showcasing higher translation accuracy and better style consistency. In addition, we find that the LLM scores are generally higher than those given by human annotators, indicating that the alignment of the values of the LLM-based evaluators remains an important direction for future exploration.

Figure 6.

Results of human evaluation and large language model evaluation.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we highlight the existing deficiencies in addressing consistency within in-image translation tasks, specifically focusing on translation consistency and image generation consistency. To enhance these aspects of consistency, we propose a two-stage framework comprising text image translation based on MMLLMs and image backfilling based on a diffusion model. In the first stage, we incorporate chain-of-thought learning to improve translation consistency. In the second stage, we modify the architecture of the existing diffusion model by introducing a style latent module, and we curate a dataset of parallel corpus pairs to train a diffusion model capable of generating text images with consistent stylistic properties. This approach enhances the style consistency and background coherence when generating image texts. Ultimately, our framework yields promising results on both constructed and real image test sets, underscoring its efficacy.

In the future, we will continue to advance in-image translation from the following perspectives to further enhance its capabilities:

- While our method makes clear progress in preserving text style, it still fails in some more complex style transfer scenarios, such as cases where a single sentence contains multiple distinct text styles. This limitation is likely due to the constraints of our pseudo-data construction process, which cannot fully cover the wide range of style transfer requirements encountered in real-world images. We leave addressing these more complex style variations as an important direction for future work.

- Improving the detailed content of IIT: IIT is a complex task encompassing multiple modalities and diverse scenarios. While our method has proposed a general framework, there are still intricacies that require resolution within this framework. These include translating vertical text images, translating multi-line text images, collaborative translation of multiple texts, translation of lengthy text images, and optimizing text positioning during translation. Our forthcoming research endeavors will concentrate on refining these aspects.

- End-to-end IIT frameworks: Presently, models that exhibit superior performance are often designed in a cascaded manner. Cascaded approaches may encounter issues such as error accumulation and high latency. Therefore, our upcoming research will investigate end-to-end methods for IIT to overcome these challenges and improve efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.; Methodology, C.F. and Y.H.; Software, C.F.; Validation, C.F. and W.H.; Formal analysis, C.F.; Investigation, C.F., W.H., and B.L.; Resources, Y.X. and H.W.; Data curation, C.F. and Y.X.; Writing—original draft, C.F. and Y.H.; Writing—review and editing, C.F., X.F., Y.H., B.L., H.W., and T.L.; Visualization, C.F.; Supervision, X.F. and T.L.; Funding acquisition, X.F., Y.X., and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grants 6252200908, 62276078, and U22B2059), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (XNJKKGYDJ2024013), the State Key Laboratory of Micro-Spacecraft Rapid Design and Intelligent Cluster (MS01240122), the Major Key Project of PCL (Grant No. PCL2025A12 and PCL2025A03), and the National Science and Technology Major Program (Grant No. 2024ZD01NL00101).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, M.; Han, X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Improving end-to-end text image translation from the auxiliary text translation task. In Proceedings of the 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–25 August 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1664–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z.; Yu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Luan, J.; Wang, B.; Huang, D.; Su, J. Exploring Better Text Image Translation with Multimodal Codebook. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 3479–3491. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.; Zhang, P.; Yang, B.; Fan, K.; Ma, Y.; Wong, D.F.; Sun, X.; Ji, R. AnyTrans: Translate AnyText in the Image with Large Scale Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.11432. [Google Scholar]

- Caglayan, O.; Barrault, L.; Bougares, F. Multimodal attention for neural machine translation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.03976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Wan, X. Multimodal transformer for multimodal machine translation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Virtual, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 4346–4350. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Meng, F.; Su, J.; Zhou, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Luo, J. A Novel Graph-based Multi-modal Fusion Encoder for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Virtual, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 3025–3035. [Google Scholar]

- Caglayan, O.; Kuyu, M.; Amac, M.S.; Madhyastha, P.S.; Erdem, E.; Erdem, A.; Specia, L. Cross-lingual Visual Pre-training for Multimodal Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, Virtual, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 1317–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Lv, C.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, T.; Xiao, T.; Ma, A.; Zhu, J. On Vision Features in Multimodal Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 6327–6337. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y.; Okada, Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Takeda, T. Translation camera. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Pattern Recognition (Cat. No. 98EX170), Brisbane, Australia, 16–20 August 1998; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 613–617. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Cao, H.; Natarajan, P. Integrating natural language processing with image document analysis: What we learned from two real-world applications. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recognit. (IJDAR) 2015, 18, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Niu, L.; Meng, F.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, M.; Su, J. Translatotron-V (ison): An End-to-End Model for In-Image Machine Translation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.02894. [Google Scholar]

- Vinyals, O.; Toshev, A.; Bengio, S.; Erhan, D. Show and tell: A neural image caption generator. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3156–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Krishna, R.; Bernstein, M.; Li, F.-F. Visual relationship detection with language priors. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 852–869. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Li, F.-F. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Cheng, T.; Peng, Z.; Zuo, W.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, F.Y.; Zhang, D. A survey on deep learning fundamentals. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Song, M.; Zuo, W.; Du, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Application of convolutional neural networks in image super-resolution. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.02604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, M.; Chen, C.; Wang, R.; Niu, D.; Lu, H.; Lin, X. Glyphdraw: Learning to draw chinese characters in image synthesis models coherently. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.17870. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Gui, D.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, W.; Ding, H.; Hu, H.; Chen, K. Glyphcontrol: Glyph conditional control for visual text generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 44050–44066. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Lv, T.; Cui, L.; Chen, Q.; Wei, F. Textdiffuser: Diffusion models as text painters. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 9353–9387. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Lv, T.; Cui, L.; Chen, Q.; Wei, F. Textdiffuser-2: Unleashing the power of language models for text rendering. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.16465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.; Xiang, W.; He, J.Y.; Geng, Y.; Xie, X. AnyText: Multilingual Visual Text Generation and Editing. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Pensacola, FL, USA, 5–7 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Feng, X.; Li, B.; Fu, C.; Huo, W.; Liu, T.; Qin, B. Aligning translation-specific understanding to general understanding in large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.05072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futeral, M.; Schmid, C.; Laptev, I.; Sagot, B.; Bawden, R. Tackling Ambiguity with Images: Improved Multimodal Machine Translation and Contrastive Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 5394–5413. [Google Scholar]

- Nayef, N.; Patel, Y.; Busta, M.; Chowdhury, P.N.; Karatzas, D.; Khlif, W.; Matas, J.; Pal, U.; Burie, J.C.; Liu, C.L. ICDAR2019 Robust Reading Challenge on Multi-lingual Scene Text Detection and Recognition—RRC-MLT-2019. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, A.; Bhosale, S.; Schwenk, H.; Ma, Z.; El-Kishky, A.; Goyal, S.; Baines, M.; Celebi, O.; Wenzek, G.; Chaudhary, V.; et al. Beyond English-Centric Multilingual Machine Translation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Jussà, M.R.; Cross, J.; Çelebi, O.; Elbayad, M.; Heafield, K.; Heffernan, K.; Kalbassi, E.; Lam, J.; Licht, D.; Maillard, J.; et al. No language left behind: Scaling human-centered machine translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-VL Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rei, R.; Stewart, C.; Farinha, A.C.; Lavie, A. COMET: A Neural Framework for MT Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Virtual, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 2685–2702. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Yang, X.; Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Q.; Lau, R.W. Spatial attentive single-image deraining with a high quality real rain dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 12270–12279. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.