Abstract

In the theory of mixed-type equations, there are many works in bounded domains with smooth boundaries bounded by a normal curve for first- and second-kind mixed-type equations. In this paper, for a second-kind mixed-type equation in an unbounded domain whose elliptic part is a horizontal half-strip, a Bitsadze–Samarskii-type problem is investigated. The uniqueness of the solution is proved using the extremum principle, and the existence of the solution is proved by the Green’s function method and the integral equations method. When constructing the Green’s function, the properties of Bessel functions of the second kind with imaginary argument and the properties of the Gauss hypergeometric function are widely used. Visualization of the solution to the Bitsadze–Samarskii-type problem is performed, confirming its correctness from both mathematical and physical points of view.

Keywords:

Bitsadze–Samarskii problem; second-kind mixed-type equation; extremum principle; Green’s function method; integral equations method; horizontal half-strip MSC:

35M10; 35R11; 35R10; 33C10; 35A08

1. Introduction

A new stage in the development of the theory of boundary value problems for mixed-type equations are the works of M.A. Lavrentiev [1], L. Bers [2], F.I. Frankl [3] and Chen Gui-Qiang G. [4], where the importance of the problem, in particular, the Tricomi problem, is indicated in connection with transonic gas dynamics, magnetohydrodynamic flows with transition through the speed of sound and the Alfvén speed, the theory of infinitesimal bendings of surfaces, and many other issues of mechanics.

It should be noted that the overwhelming majority of works on mixed-type equations in unbounded domains relate to the study of boundary value problems for the Lavrentiev–Bitsadze model equation [5,6,7,8,9]:

It is known that Tricomi problems arise in various applications, including aerodynamics (for example, when studying gas flows at supersonic speeds) and other areas where it is necessary to take into account the change in the type of equation in different domains. A number of simplest typical problems of transonic aerodynamics lead to the Tricomi boundary value problem, for which the domain lying in the elliptic part of the plane is a half-strip [10,11].

It should be noted that most of the studies on mixed-type equations relate to the study of boundary value problems for mixed-type equations of the first kind with power degeneration

that is, only equations were considered for which the tangent to the parabolic line does not coincide at any point with the characteristic direction of the equation at that point.

As is well known, problems with nonlocal boundary conditions, the general definition and classification of which are given in [12], became a new stage in the development of the theory of boundary value problems for equations of elliptic, hyperbolic, and mixed types. First of all, such problems include problems of the Bitsadze–Samarskii type, first proposed in 1969 by A. V. Bitsadze and A. A. Samarskii [13], and A. M. Nakhushev [14], where problems with a shift are considered when a nonlocal condition is specified on the hyperbolic part of the boundary that pointwise connects the value of the desired solution or its derivative, generally fractional, of a certain order, and a Dirichlet condition is specified on the elliptic part.

Many works with problems containing nonlocal conditions have been studied for mixed-type equations of the first kind with integer-order derivatives in bounded domains [15,16,17,18,19]. Problems containing nonlocal conditions for mixed-type equations of the first and second kind with integer-order derivatives in unbounded domains have been little studied [20,21,22,23,24].

A new direction in the theory of mixed-type equations are problems with nonlocal conditions for mixed-type equations containing fractional derivatives [25,26,27].

The Tricomi problem for a second-kind mixed-type equation in a bounded domain

was first considered in the work of I.L. Karol [28]. In this paper, the elliptic part of the mixed domain is bounded by the normal curve , and the hyperbolic part by the characteristics of Equation (1), for which the degeneracy line is simultaneously a characteristic. Following Tricomi’s idea, the N problem in the elliptic part and the Cauchy problem in the hyperbolic part of the mixed domain are first solved by the Green’s function method, considering the function to be known. Then, both obtained solutions, together with their first derivatives, are continuously “glued” together on a segment of a parabolic line. Thus, the proof of the existence of a solution to the Tricomi problem is reduced to solving an integral equation for , the solvability of which follows from the uniqueness theorem. All other works related to Equation (1) are considered only in the limited area where the representation of the solution to the N problem obtained in [28] is used, for example, in [29].

In the case where the elliptical part of the mixed domain is a vertical half-strip, the problem with a shift on the characteristic of one family was investigated in our paper [21], where the N problem in the elliptical part of the mixed domain was solved using the Green’s function method.

As is well known, interest in the Dirichlet problem for mixed-type equations increased sharply after the well-known works of F. I. Frankl [3], who first drew attention to the fact that many problems in transonic gas dynamics and hydrodynamics can be reduced to the Dirichlet problem. Thus, if we consider the problem of breaking the sound barrier for steady-state two-dimensional irrotational flows of an ideal gas in nozzles, when supersonic zones adjoin the nozzle walls near the minimum cross-section, then for linear second-order partial differential equations of mixed type in a simplified formulation, it reduces to the Dirichlet problem.

In the work we examined, firstly, the ellipticity region is a horizontal strip, and secondly, the Dirichlet problem is solved using the Green’s function method. As is well known, for degenerate elliptic equations, a separate Green’s function is constructed for each problem and ellipticity region.

The research plan in the present work is as follows. Section 1 provides introductory information on the research topic and a literature review. Section 2 gives preliminary information on fractional calculus. Section 3 presents the problem statement. Section 4 discusses the existence and uniqueness of the solution. Section 5 visualizes the solution. Section 6 draws conclusions based on the results of the conducted research.

2. Preliminaries

We give definitions of the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral and derivative, and also present some of their properties. The properties of these operators can be studied in more detail in the monographs [14,30].

Definition 1.

Let the function be integrable on the interval , and (a real number). Then, the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of order α is defined as:

where is the Euler gamma function.

Definition 2.

Let m be the smallest integer such that (i.e., ), and . Then, the Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative of order μ is defined as:

where is the ordinary derivative of integer order m.

- 1.

- Linearity. Let the functions and be integrable on the interval , and and real numbers, then:

- 2.

- Consistency with classical operations:

- 3.

- Semigroup property (index rule):

- 4.

- Composition of integral and derivative:

Remark 1.

Note that, in general, . For example, for , we obtain

3. Problem Statement

In this work, a nonlocal problem is investigated for the second-kind mixed-type Equation (1), where the parabolic line of this equation—the axis —is the envelope of the families of its characteristics

emanating from the point , i.e., the degeneration line of the equation is also a characteristic.

For Equation (1) in the unbounded mixed domain , where , , is the domain of the half-plane , bounded by the segment of the axis, as well as the characteristics and of Equation (1).

We introduce the notation

Here, is the affix of the intersection point of the characteristic of Equation (1) emanating from the point with the characteristic .

Problem 1

(). Find a function with the following properties:

- (1)

- and satisfies Equation (1) in the domain ;

- (2)

- In the domain , it is a generalized solution of Equation (1) belonging to class R [28];

- (3)

- The partial derivative satisfies the gluing condition , , which arises when solving the direct problem of Laval nozzle theory [2,11], and can have a singularity of order less than one at the ends of the interval (0,1);

- (4)

- satisfies the conditionsand the nonlocal Bitsadze–Samarskii-type conditionwhere is a given function, with , .

The Bitsadze–Samarskii-type nonlocal condition (8) models processes where the value of the solution at one point is related to its value at another point, which is typical for problems with internal connections or shifted boundary conditions.

In the half-plane , the equation takes the form

In the characteristic coordinates

It is known that the solution of the Cauchy problem for Equation (10) with initial conditions

where , and the functions and are continuous in the interval and integrable on the segment , the operator where is a fractional integral of order according to definition (2), has the form [15,28,29]:

where , and there exists ; vanishes to an order not less than , and is integrable on .

4. Existence and Uniqueness of the Solution

As is known, the unique solvability of boundary value problems for equations of mixed type is proved by the Tricomi method [15]. First, the uniqueness of the solution to the problem under study is proved using the extremum principle. In proving the uniqueness of the solution to the problem under study, we use the representation of the solution to the Cauchy problem in the hyperbolic part of the mixed domain and, taking into account the nonlocal condition (13), we obtain the first functional relationship between and . To prove the existence of a solution to the problem using the Green’s function method, the Dirichlet problem is solved in the elliptic part and, from the formula for representing the solution, we obtain the second functional relationship between and from the elliptic part of the mixed domain. Eliminating the function from these relations, we obtain a Fredholm integral equation of the second kind with respect to the unknown function , equivalent (in the sense of solvability) to the problem , that is, the proof of the existence of a solution to the problem is reduced to solving this integral equation with respect to , the solvability of which follows from the uniqueness theorem.

Theorem 1.

If , then the solution of the problem is unique and exists.

Proof.

First, we prove the uniqueness of the solution of the posed problem. Let be a solution of the homogeneous problem . In this case, we have . Therefore, relation (14) takes the form

Let us prove that in . Assume the contrary. Then, there exists a domain in which . Consequently, and this value is attained at some point .

We introduce the notation , where , , , , .

According to the extremum principle for elliptic equations [31], it follows that . By virtue of conditions (6), we have . Then, .

Let , i.e., . Then, if , i.e., is a point of positive maximum (negative minimum) of the function , we show that . To do this, we determine the sign of the function at the point , where is a point of positive maximum of the function . For this, we transform the expressions and and determine their sign at the point . Since vanishes to an order not less than , then according to (3),

If the function satisfies the Hölder condition with exponent for , then

Take an arbitrary point lying between 0 and x and write the integral entering (16) as the sum of two integrals; then, using integration by parts for , we obtain:

As , the sign of (17) is determined by the signs of the following two terms

since , because the point is a point of positive maximum of the function .

Taking into account the last inequalities obtained from (17) and (18), and assuming , relation (17) between and for has the form:

Now, we prove that for , the sign of the function is non-positive. Consider the system of inequalities:

Using the known reflection formula [32]

we transform the first inequality of the system

Performing similar calculations, the second inequality of the system transforms as follows:

Considering that the function is increasing, hence its smallest value is , we have:

Then, from Formula (19), taking into account the condition and the gluing condition, we obtain . On the other hand, by the Zaremba–Giraud principle [31], , . The obtained contradiction implies that . Consequently, , i.e., .

Taking an arbitrary number by the same method, we obtain . Since , then , i.e., . It follows that , which contradicts condition (7).

Consequently, , for any . Since , it follows from (15) that . Then, according to Formula (11), in . Consequently, in , whence the assertion of the theorem follows.

Now, we turn to the proof of the existence of a solution. First, using the theory of special functions [32] and well-known methods of separation of variables [33,34], the Green’s function of the Dirichlet problem for Equation (1) in the domain is constructed. Then, using the methodology of work [15], a solution to the Dirichlet problem for Equation (1) in the domain is obtained, satisfying conditions (11) and (12), as well as the condition , in the following form:

where is the Green’s function of the Dirichlet problem and

Here, are Bessel functions of imaginary argument [32], , , and is the gamma function [32].

Taking into account the obvious identity

Further applying integration by parts and taking into account that , and also passing to the limit as , we obtain the second functional relation between and from the elliptic part of the mixed domain

where

Eliminating from the functional relations (14) and (24) by virtue of the gluing condition , we obtain a Fredholm integral equation of the second kind with respect to in the following form

By virtue of the well-known formulas [15]:

The kernel has a logarithmic singularity at , and since , it can become infinite of order less than one at . The solvability of Equation (25) follows from the uniqueness theorem for the problem . Having determined from Equation (25), we find from (14), and then, using Formulas (13) and (23), we obtain the solution in the domains and , respectively. □

5. Visualization of the Solution to the BS∞ Problem

In order to check the correctness of the solution to the Bitsadze–Samarskii-type problem, we perform its visualization using the Python programming language [35]. As an example, we take the following values and functions of the problem: .

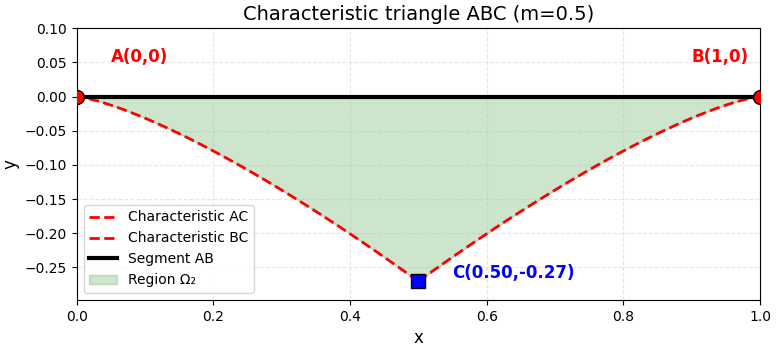

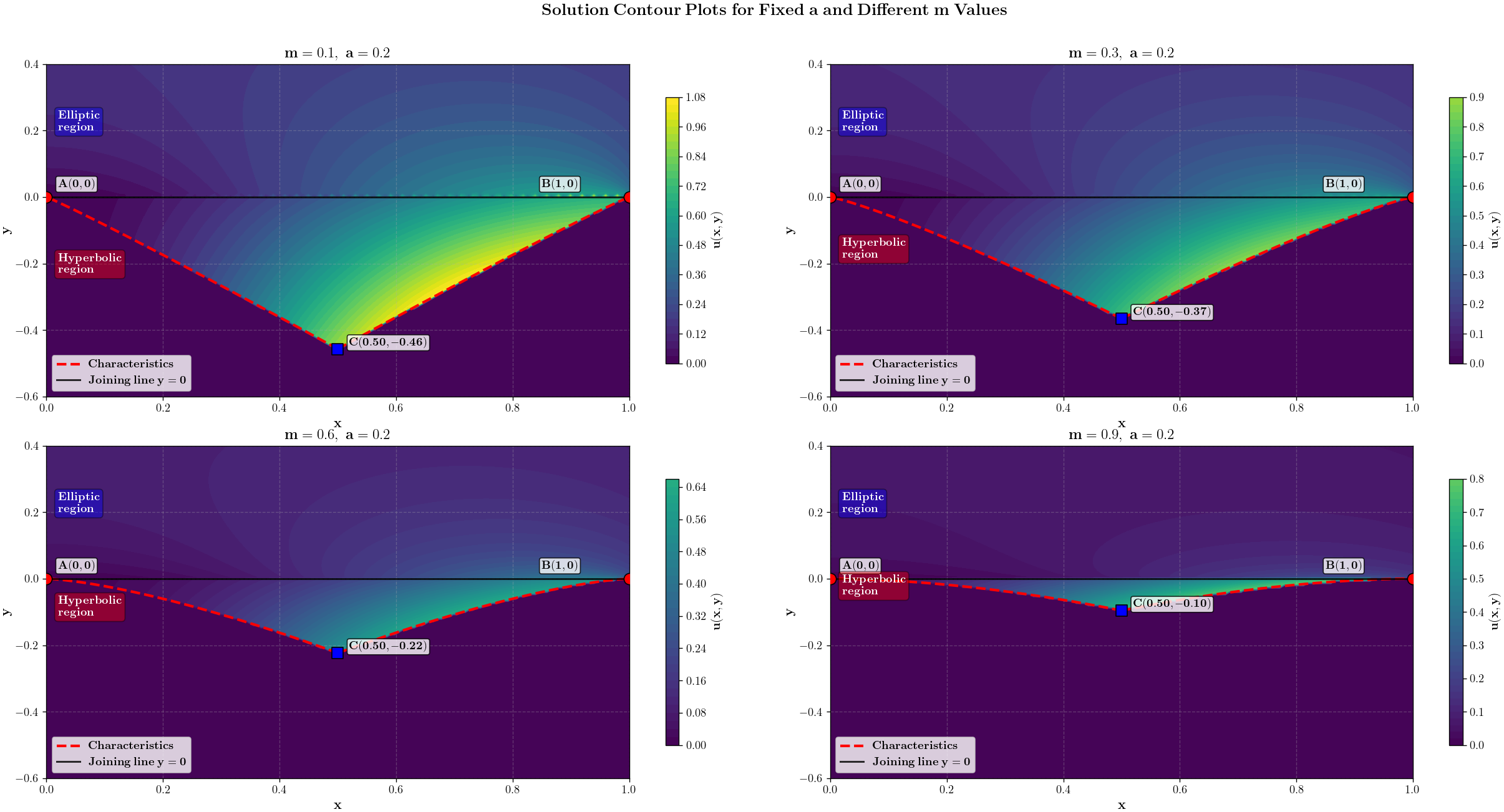

Figure 1 shows the domain of definition of the solution in the hyperbolic part (characteristic triangle) for .

Figure 1.

Characteristic triangle in the hyperbolic part.

Figure 1 depicts the domain of definition for the solution in the hyperbolic part () of Equation (1) for the parameter . This domain is the finite triangle , bounded by the segment of the axis () and the two characteristics and of the mixed-type equation emanating from point C. The vertex coordinates are: , , and . This characteristic domain is fundamental for imposing the nonlocal Bitsadze–Samarskii-type condition on the characteristic A. The plot clearly demonstrates how the geometry of the hyperbolic region depends on the parameter m: as m increases, the triangle narrows, and as it decreases, the triangle expands.

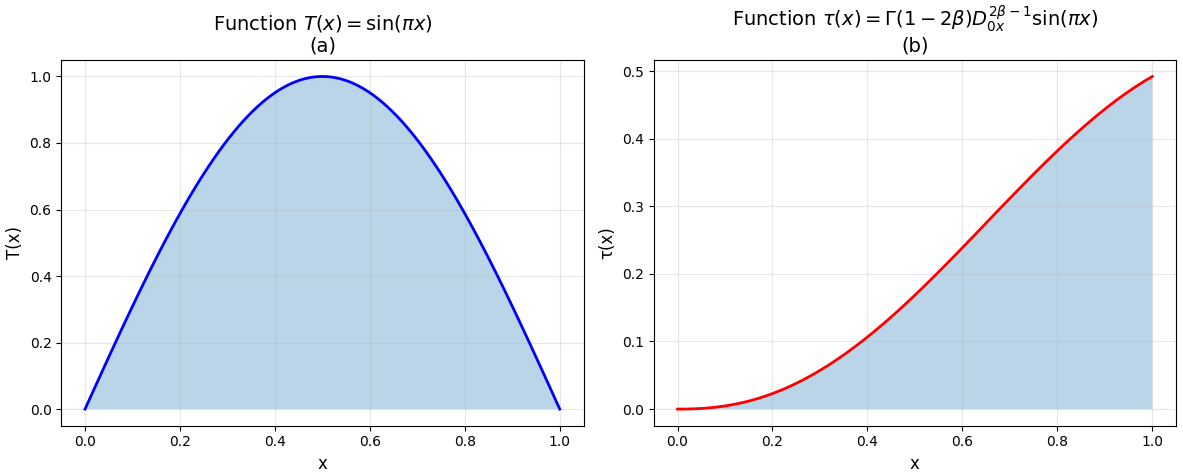

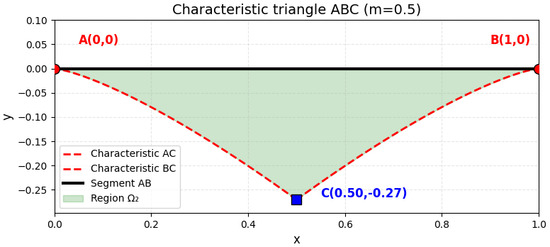

Figure 2 illustrates the transformation of a boundary function during the solution construction process.

Figure 2.

Graphs: (a)—; (b)—.

Figure 2a shows the graph of the given function , used as input in the example under consideration. This function models, for example, the stationary amplitude distribution in an elliptic domain.

Figure 2b shows the graph of the function , which is the result of applying the fractional Riemann–Liouville integral operator of order (where ) to , as defined by Formula (12). The function represents the value of the sought solution on the gluing interval of the axis () and plays a key role in the functional relationships between the elliptic and hyperbolic parts.

Comparison of Figure 2a,b clearly demonstrates the effect of fractional conversion, which changes the amplitude and shape of the original signal.

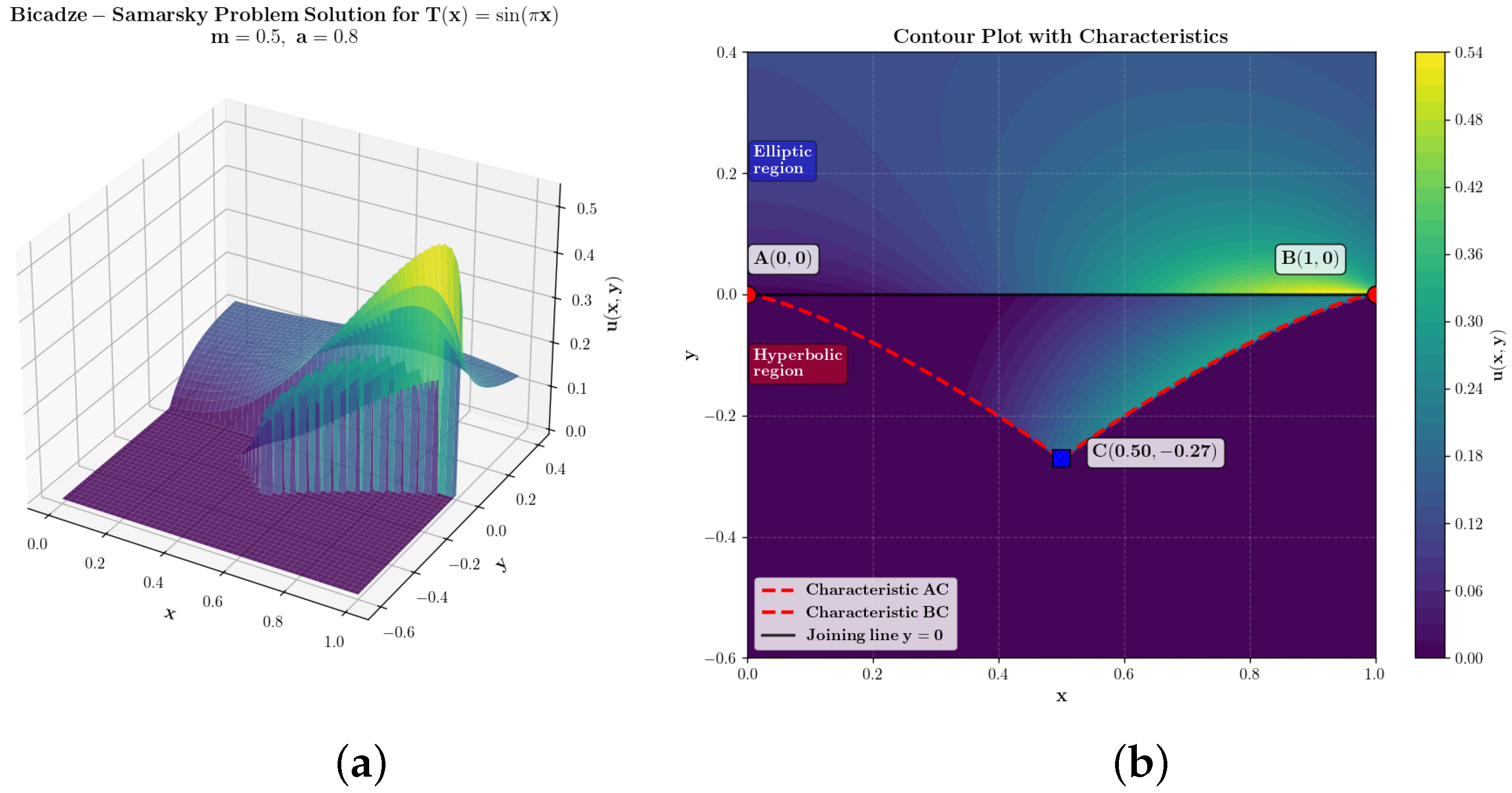

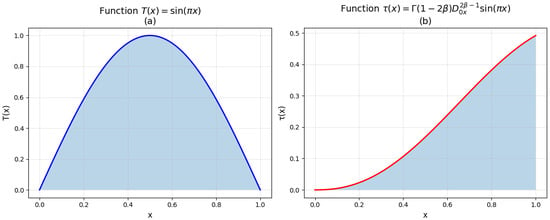

Figure 3 shows the wave pattern, which consists of a 3D surface (Figure 3a) and a contour plot (Figure 3b). They reflect the solution of the Bitsadze–Samarskii-type problem. It can be seen that the solution is continuous and the gluing condition is fully satisfied—the contour lines (Figure 3b) from the hyperbolic part smoothly transition into the contour lines of the elliptic part. The mathematical component of the problem is correctly fulfilled.

Figure 3.

Wave pattern: (a)—3D plot of the solution to the BS∞ problem; (b)—contour plot of the solution to the BS∞ problem.

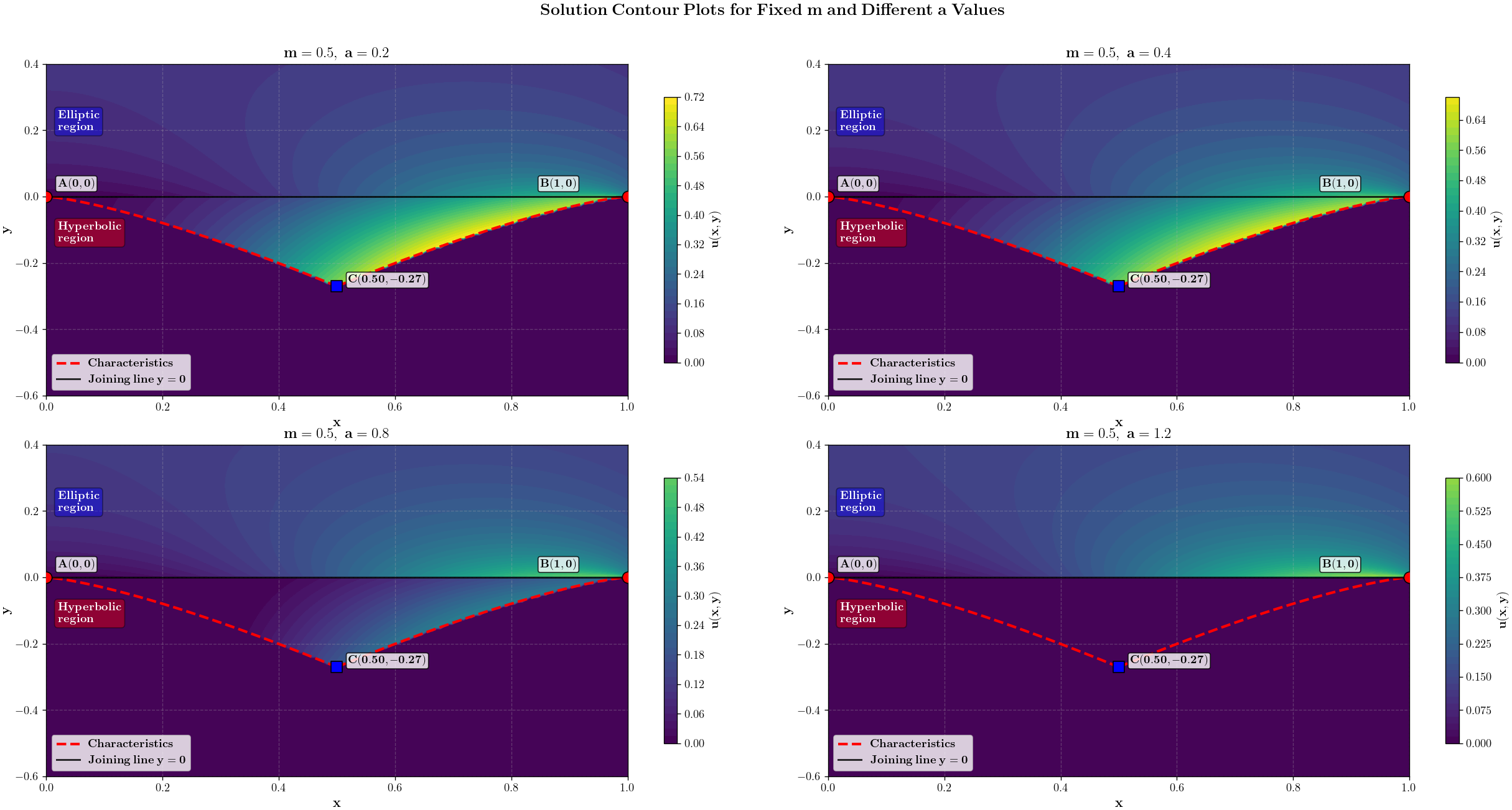

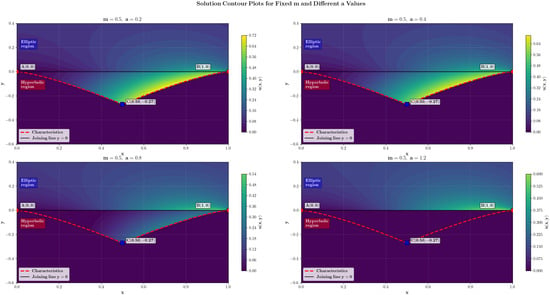

Let us consider the influence of the parameters m () and a on the solution of the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem.

Figure 4 shows contour plots of the solution to the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem for a fixed parameter value of and various values of a. These plots show that as the value of increases, the solution in the hyperbolic part tends toward a minimum value (practically zero). Furthermore, for , the solution in the hyperbolic part becomes trivial, confirming the condition of the existence and uniqueness theorem.

Figure 4.

Contour graph of the solution to the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem, constructed with a fixed value of and different values of a.

Physically, a can be viewed as a feedback coefficient between wave processes in the hyperbolic region and the steady state in the elliptic region. The condition , under which the uniqueness of the solution is proven, means that the feedback must not exceed a certain critical value; otherwise, the model loses its physical validity (for example, instability or non-uniqueness of the solution may occur).

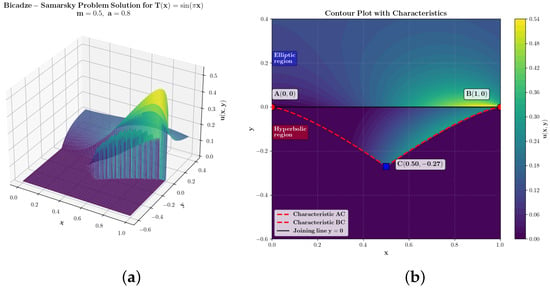

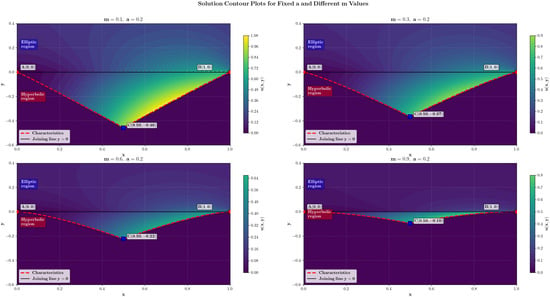

Figure 5 shows other contour plots of the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem, constructed for a fixed value of and various values of m. Figure 5 shows other contour plots of the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem, constructed for a fixed value of and various values of . This leads to a change in the pattern of wave propagation: at large m, the energy of the wave process in the hyperbolic part is concentrated near the axis , and the amplitude of the solution far from the interface decreases. On the contrary, for small m (close to 0), the hyperbolic region expands, the waves propagate to greater depths, and the picture becomes smoother. Thus, the parameter m significantly affects the geometry of the definition domain and the distribution of wave energy in the hyperbolic part.

Figure 5.

Contour graph of the solution to the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem, constructed with a fixed value of and different values of m.

The parameter and is a derivative of m and is included in the explicit form of the solution through the Riemann–Liouville fractional derivatives. It determines the rate of change of the solution near the degeneracy line: the closer is to zero, the smoother the solution is at the boundary . Physically, can be interpreted as an indicator that determines the degree of connection between the stationary (elliptic) and wave (hyperbolic) parts of the process.

We demonstrated that the parameters , and a play a key role in shaping the solution to the Bitsadze–Samarskii problem:

- (1)

- m determines the geometry of the region and the degree of inhomogeneity of the medium;

- (2)

- characterizes the smoothness of the solution near the type-change line;

- (3)

- a specifies the strength of the nonlocal coupling between the elliptic and hyperbolic parts, ensuring consistency of the wave processes.

Let us give a physical interpretation of the Bitsadze–Samarskii-type problem. It can be interpreted as a model of wave propagation in an inhomogeneous medium with an abrupt change in properties.

- 1.

- Elliptic region (), a region where the process is stationary or oscillatory without energy transfer over distance. This can be: a cross-section of a waveguide (resonator), where describes the amplitude of a standing wave (for example, mode); a steady-state field (temperature, potential) in a medium where diffusion processes dominate. The solution here oscillates or decays exponentially from the boundary. There are no characteristics—no preferred directions of disturbance propagation. The wave is “trapped” in this region. On the graph, the contour pattern in the upper part (elliptic region) shows the isolines of this stationary field.

- 2.

- Hyperbolic region (), a region where the process is wave-like, and the equation describes the propagation of disturbances with finite speed. This can be: a region where the medium allows the wave to propagate (for example, open space behind the throat of a waveguide); a model of a dynamic process in time (if y is interpreted as time).There are characteristics along which the wave propagates. In Figure 3b, lines AC and BC are precisely these characteristics. They form the “cone of dependence” of point C. The wave from the elliptic region, penetrating through the boundary , generates in the hyperbolic region two diverging waves traveling along these characteristics.

- 3.

- Gluing line () is a sharp interface between two media with radically different properties: on one side, ()—a “medium without transfer” (waveguide, diffusive medium); on the other side, ()—a “medium with transfer” (free space, wave propagation medium). The stationary oscillation in the region () serves as a source for traveling waves in the region . The gluing conditions at are the laws connecting the source field with the radiation generated by it. They ensure that the energy and phase of the wave transition consistently through the boundary.

- 4.

- Note the importance of the nonlocal Bitsadze–Samarskii condition. It not only is an additional condition guaranteeing the uniqueness of the solution but also ensures complete coordination of the solutions in the elliptic and hyperbolic regions. Without this condition, the problem would be underdetermined. This condition also has a physical interpretation—it describes the feedback between standing waves in the elliptic region and traveling waves in the hyperbolic region, and the parameter a plays the role of a feedback coefficient. The nonlocal Bitsadze–Samarskii condition given on the characteristic AC can limit the amplitude of the wave, i.e., the feedback can dampen oscillations. We can see this effect on the contour plot (Figure 3b). Near the characteristic BC, we see that the solution has larger values than near the characteristic AC. This is because BC models free wave propagation and therefore can accumulate energy, leading to higher amplitudes (the contour lines on the contour plot near characteristic BC are denser).

The resulting physical picture (using the example ): In the upper elliptic part of Figure 3b (), there exists a stationary pattern—a sinusoidal “mode” , fixed at the boundary AB. This mode excites oscillations at the interface . Each point of this boundary becomes a point source for the lower medium (hyperbolic part). Radiation from these sources propagates in the lower region () along the characteristics. As a result, a wave field is formed, shown on the contour plot (Figure 3b) in the lower part: interference of these secondary waves creates a complex pattern, which, however, is completely determined by the original mode and the geometry of the characteristics (AC, BC).

Thus, the Bitsadze–Samarskii-type problem mathematically models a complex process of transformation of a standing wave (or stationary field) into a traveling wave upon transition through a critical boundary with feedback, on which the type of the governing differential equation changes.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates a nonlocal boundary value problem of Bitsadze–Samarskii type for a second-kind mixed-type equation in an unbounded domain whose elliptic part is a horizontal half-strip. The main results of the work can be summarized as follows:

A second-kind mixed-type equation with degeneration along the parabolic line, which is the envelope of characteristics, is considered. A problem with a nonlocal condition on the characteristic relating the solution values at different boundary points is studied, generalizing the classical Bitsadze–Samarskii formulation to the case of an unbounded domain and second-kind equations.

Under the condition , the uniqueness of the solution is proved using the extremum principle for the elliptic part and an analysis of the solution behavior at infinity. The existence of the solution is established by the Green’s function method and reduction to a Fredholm integral equation of the second kind. The kernel of the obtained integral equation has a weak singularity, which ensures its solvability within the framework of the Fredholm alternative.

Methods of fractional calculus (Riemann–Liouville derivatives and integrals) are systematically applied, which made it possible to correctly account for the behavior of the solution near the degeneration line. In constructing the Green’s function, properties of special functions—Bessel functions with imaginary argument and the Gauss hypergeometric function—are used, providing an explicit integral representation of the solution.

Numerical visualization of the solution is performed using Python 3.13, which confirmed the continuity of the solution, fulfillment of the gluing condition on the line of type change, and consistency between the elliptic and hyperbolic parts. The resulting wave pattern is interpreted as a model of wave propagation in an inhomogeneous medium with an abrupt change in properties at the interface. The elliptic region corresponds to a stationary or oscillatory regime without energy transfer, while the hyperbolic region corresponds to a wave process with finite propagation speed. The nonlocal Bitsadze–Samarskii condition acts as feedback between these regimes, ensuring the physical consistency of the model.

The developed approach can be applied to more general classes of mixed-type equations with fractional derivatives, as well as to problems in domains with more complex geometries. It is of interest to study problems with nonlocal conditions on multiple characteristics, as well as to investigate the asymptotic behavior of solutions as parameters approach critical values. The numerical methods used for visualization can be adapted for solving applied problems in gas dynamics, acoustics, and waveguide theory.

Thus, the work contributes to the theory of boundary value problems for mixed-type equations, expanding the class of studied domains and conditions, offers constructive methods for constructing solutions, and demonstrates their applicability in both theoretical and applied aspects. The research results are supported by rigorous analytical proofs and clear numerical visualization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and R.P.; methodology, R.Z.; software, R.P.; validation, A.E., R.Z. and R.P.; formal analysis, A.E.; investigation, A.E., R.Z. and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z. and R.P.; writing—review and editing, R.Z. and R.P.; visualization, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out within the framework of the agreement between IKIR FEB RAS and the Romanovsky Institute of Mathematics (Tashkent, Uzbekistan) No. 1117 dated 28 April 2022 (0469/01/22 NTMI) on mathematical research (problem formulation and study of its unique solvability) and the state assignment of IKIR FEB RAS No. 124012300245-2. Topic “Interaction of physical processes in the system of near space and geospheres” (2024–2028) (numerical calculations of the wave pattern and their visualization).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lavrentiev, M.A.; Bitsadze, A.V. On the problem of equations of mixed type. Rep. USSR Acad. Sci. 1950, 70, 485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bers, L. Mathematical Aspects of Subsonic and Transonic Gas Dynamics; Courier Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 2016; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, F.I. Selected Works on Gas Dynamics; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1973; p. 703. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.-Q.G. Partial differential equations of mixed type—Analysis and applications. N. Am. Math. Soc. 2023, 70, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzhavina, M.V. Tricomi problems for the generalized Tricomi equation in the case of an infinite half-strip. Volzhsky Math. Collect. 1971, 8, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Korzhavina, M.V. Solution of problem T for the Lavrentiev-Bitsadze equation in an unbounded domain. Differ. Equ. Proc. Pedagog. Institutes RSFSR 1974, 4, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sevost’janov, G.D. Two Tricomi boundary value problems in an unbounded region. Izv. Vyssh. Uchebn. Zaved. Mat. 1967, 1, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Flaisher, N.M. On a problem of Frankl’ for the Lavrent’ev equation in the case of an unbounded region. Izv. Vyssh. Uchebn. Zaved. Mat. 1966, 6, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, N.M. Boundary value problems for equations of mixed type in the case of unbounded domains. Rev. Roum. Math. Pures Appl. 1965, 10, 607–613. [Google Scholar]

- Sevostyanov, G.D. Flow of a sonic gas jet around an airfoil. USSR Acad. Sci. Ser. Mech. Liq. Gases 1966, 30, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Falkovich, S.V. On one case of solving the Tricomi problem. Transonic Gas Flows 1964, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nakhushev, A.M. Equations of Mathematical Biology; Vysshaya Shkola: Moscow, Russia, 1995; p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsadze, A.V.; Samarskii, A.A. Some elementary generalizations of linear elliptic boundary value problems. In Doklady Akademii Nauk; Russian Academy of Sciences: Moscow, Russia, 1969; Volume 185, pp. 739–740. [Google Scholar]

- Nakhushev, A.M. Fractional Calculus and Its Applications; FIZMATLIT: Moscow, Russia, 2003; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, M.M. Equations of Mixed Type; American Mathematical Soc.: Providence, RI, USA, 1978; Volume 51, p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsadze, A.V. Equations of the Mixed Type; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sabitov, K. On the Theory of Mixed-Type Equations; LitRes: Moscow, Russia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ezaova, A.G. Unique Solvability of a Bitsadze-Samarskiy Type Problem for Equations with Disontinuous Coefficient. Vladikavkaz Math. J. 2018, 20, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mirsaburov, M.; Makulbay, A.B.; Mirsaburova, G.M. A combined problem with local and nonlocal conditions for a class of mixed-type equations. Bull. Karaganda University. Math. Ser. 2025, 118, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repin, O.A.; Kumykova, S.K. On a boundary value problem with shift for an equation of mixed type in an unbounded domain. Differ. Equ. 2012, 48, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Zunnunov, R.T.; Ergashev, A.A. The problem with shift for an equation of mixed type of the second kind in an unbounded domain. Vestnik KRAUNC. Fiz.-Mat. Nauki 2016, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairullin, R.S. Boundary Value Problems for a Mixed-Type Equation of the Second Kind; Kazan University Publishing House: Kazan, Russia, 2020; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- Muminov, F.M.; Muminov, S.F. About One Nonlocal Boundary Value Problem for a Mixed Type Equation. Cent. Asian J. Math. Theory Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zunnunov, R.T. A Problem with Shiff for Mixed-Type Equation in Domain, the Elliptical Part of Which Is a Horizontal Strip. Lobachevskii J. Math. 2023, 44, 4410–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turmetov, B.K.; Kadirkulov, B.J. On a problem for nonlocal mixed-type fractional order equation with degeneration. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 146, 110835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruziev, M.G.; Zunnunov, R.T. On a nonlocal problem for mixed-type equation with partial Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Ruziev, M.H.; Parovik, R.I.; Zunnunov, R.T.; Yuldasheva, N. Non Local Problems for the Fractional Order Diffusion Equation and the Degenerate Hyperbolic Equation. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karol, I.L. On a certain boundary value problem for an equation of mixed elliptic-parabolictype. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1953, 88, 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ivashkina, G.A. On problems of Bicadze–Samarskii type for the equation uxx + sgny|y|muyy = 0 (0 < m < 1). Differ. Uravn. 1981, 17, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbas, A.A.; Srivastava, H.M.; Trujillo, J.J. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsadze, A.V. Boundary Value Problems for Second Order Elliptic Equations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev, N.N. Special Functions and Their Applications; Prentic-Hall: London, UK, 1965; p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Dolgova, I.M.; Mel’nikov, I.A. Construction of green’s functions and matrices for equations and systems of the elliptic type. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 1978, 42, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, P.M.; Feshbach, H. Methods of Theoretical Physics; Part I; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Z.A. Learn Python the Hard Way; Addison-Wesley Professional: Carrollton, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.