Abstract

This paper presents a superpixel segmentation algorithm that integrates anisotropic total variation regularization within a fuzzy clustering framework. While isotropic total variation is well-known for its edge-preserving properties, its non-adaptive nature often leads to over-regularization. In contrast, the anisotropic model formulates superpixel regularity in relation to image contours, thereby preventing the loss of image details in areas of high contour density during optimization. Compared to classical segmentation algorithms that employ non-adaptive regularization, the proposed content-adaptive approach enhances superpixel regularity while maintaining boundary adherence to image contours. Furthermore, to optimize the functional effectively, an alternating direction method of multipliers along with the enhanced Chambolle’s fast duality projection algorithm are employed. Competitive experiments against existing regular segmentation algorithms demonstrate that our proposed methodology achieves superior performance in terms of boundary recall, compactness, and shape regularity criteria, outperforming these methods by an average of at least 3%, 5%, and 3%, respectively. Furthermore, when compared with irregular segmentation algorithms, our approach achieves the best results in terms of compactness, contour density, and shape regularity criteria, with average improvements of at least 56%, 22%, and 45%, respectively.

MSC:

68T10; 62H30

1. Introduction

Superpixel segmentation is a crucial pre-processing step in image processing, with applications spanning image classification [1] and 3D reconstruction [2]. It works by over-segmenting an image into atomic regions that ideally correspond to individual objects. By grouping pixels into superpixels, this method reduces computational complexity—transforming millions of pixels into a few hundred meaningful regions, regardless of resolution. This compact representation eliminates redundant pixel-level processing, enabling more efficient algorithms compared to traditional pixel-based approaches.

Unlike pixel representation, which is essentially a regular grid, superpixels often exhibit irregular shapes and varying sizes. These irregularities are unavoidable as the algorithms strive to classify pixels into superpixels while aligning boundaries with object contours as precisely as possible. Consequently, subsequent processes that utilize superpixels must be specifically designed to accommodate their diverse shapes. These procedures typically involve analyzing the statistics of each superpixel and establishing relationships between neighboring superpixels. Irregular superpixel segmentation can significantly impede these processes; for example, tiny superpixels may result in poor feature estimations, while snake-shaped superpixels may incorrectly connect with spatially distinct neighbors. Therefore, regularity is a key metric of superpixel segmentation quality [3,4] and strongly influences their utility as pre-processing tools. However, a survey [5] shows that some superpixel algorithms perform poorly at maintaining the regularity of the generated superpixels. Furthermore, the benchmark in [6] indicates that many algorithms fail to produce regular superpixels on noisy images, limiting their applicability to noise-free, controlled environments. Nonetheless, many methods incorporate specific mechanisms to improve superpixel regularity. For instance, ERS [7] incorporates a balance term in its energy functional to promote superpixels of similar size. The SEEDS algorithm [8] introduces a boundary term that discourages image patches from containing multiple superpixel labels, thereby enhancing regularity by reducing the number of pixels near superpixel boundaries. Similarly, SLIC [9] and CAS [10] include a regularization term that favors compact superpixels. Additionally, ETPS [11] incorporates energy terms that encourage compactness, shorter boundary lengths, and enforce both connectedness and a minimum size for the superpixels.

The regularities mentioned above are non-adaptive, meaning that they do not take into account the actual content of the images or the locations of the superpixels. Most existing algorithms combine these regularity measures with fidelity terms to capture object boundaries while enforcing superpixel regularity. While this approach yields good overall performance in terms of generating regular superpixels, it inevitably results in the loss of finer image details, such as sharp corners, non-convex regions, and elongated segments. The accuracy loss stems from the fact that these non-adaptive regularities are evaluated solely based on the shapes of the superpixels. Without prior knowledge of the image, it becomes challenging to differentiate between irregular image objects and artifacts introduced by the fidelity terms, leading to both being suppressed by the regularization process. In many cases, the necessary over-smoothing of irregular geometries is required to achieve an overall smoothness of the superpixels under these non-adaptive regularity measures.

While the issue of non-adaptive superpixel regularity is seldom addressed, the related challenge of non-adaptive image regularity has been extensively studied in the field of image denoising. Recognizing that non-adaptive denoising filters often lead to over-smoothing, many image denoising techniques have been developed with various strategies to adapt to the local content of images. One such approach involves modifying the weight coefficients of mean filters adaptively for each pixel. For instance, bilateral filtering computes weights based on both spatial distances and color similarities between pixels, whereas the weights in non-local means filtering depend on the similarities between image patches. Another common strategy is to restrict regularization isotropically in areas where edges and other details are likely to be present. An example of this is the Perona–Malik diffusion [12], which employs a diffusion coefficient that is inversely related to the magnitude of the gradient.

Motivation and Contribution

To overcome the limitations of non-adaptive regularities employed by current algorithms and the inadequate performance of existing superpixel segmentation methods in capturing objects with irregular geometries mentioned above, an anisotropic approach is proposed to address these challenges. The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A content-adaptive superpixel regularity measure, based on an anisotropic total variation model, is introduced to enhance the preservation of image details and is integrated into a fuzzy clustering-based segmentation framework.

- An anisotropic variational fuzzy superpixel segmentation algorithm is developed based on the alternating direction method of multipliers and an enhanced version of Chambolle’s fast duality projection algorithm.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, existing superpixel segmentation algorithms are reviewed. Section 3 presents our proposed anisotropic variational fuzzy superpixel segmentation model with content-adaptive regularity. The optimization procedure and implementation details of our proposed algorithm are discussed in Section 4. Finally, experiments and competitive results are reported in Section 5 and Section 6, concluding the paper.

2. Related Works

Since the introduction of superpixels in [13], which demonstrated their effectiveness in image segmentation, numerous superpixel algorithms have been developed over the past few decades. Most of these algorithms focus on enhancing performance in capturing object boundaries, while only a few address the regularity of superpixels. Existing superpixel algorithms can be classified into three main categories: clustering-based, boundary-based, and graph-based algorithms. Additionally, two special types of algorithms deserve a separate mention: hierarchical algorithms and deep-learning-based algorithms.

2.1. Clustering-Based Algorithms

Clustering-based algorithms classify pixels into superpixels using techniques that involve alternating updates of centroids and pixel reassignment. Notable examples include SLIC, LSC [14], and CAS, which utilize k-means clustering based on various feature representations. By incorporating spatial features like xy-coordinates, these algorithms create compact superpixels at low computational costs and can be accelerated with GPU computation. However, the Euclidean distances used in standard k-means may not effectively capture the differences between individual pixels and centroids, leading to the poor adherence of superpixel boundaries to image contours. Alternatively, some algorithms adopt non-Euclidean distances to enhance performance. For instance, SCALP [15] employs a robust distance metric that considers color features and contour intensity along linear paths between pixels and superpixel barycenters, resulting in superpixels that align well with image contours when advanced contour detectors are used. Additionally, a multi-scale version of SLIC is proposed in [16], which employs a “Difference Image” to determine local scales for finer segmentation in areas with significant changes. Recently, another modification of SLIC is presented in [17], which utilizes non-uniform seed initialization and a constrained distance measure to improve the connectivity and regularity of the superpixels.

The hard labeling nature of k-means can yield unsatisfactory results, particularly in degenerated images like radar or medical images. This can negatively affect sequential processing and the classification accuracy. To address this, the authors in [18] identified uncertain pixel labels using fuzzy clustering. The fuzzy-SLIC algorithm presented in [19] allows multiple superpixels to share a single pixel’s membership and utilizes local spatial fuzzy c-means (FCM) clustering to enhance noise robustness, outperforming traditional hard labeling methods. Additionally, a superpixel algorithm based on a Gaussian mixture model (GMMSP) [20] employs the expectation–maximization method to estimate parameters and determine pixel label probabilities, allowing for explicit control over superpixel compactness.

2.2. Boundary-Based Algorithms

Boundary-based algorithms create superpixels by iteratively adjusting their boundaries, allowing for the enforcement of the smoothness and regularity criteria. These algorithms can be divided into two main types.

The first type starts with an initial segmentation, often in the form of a regular grid, and iteratively reassigns boundary pixels to neighboring superpixels. A notable example is ETPS, which, like the TPS algorithm [21], swaps boundary pixels to minimize an energy function related to color and spatial dissimilarity, as well as boundary smoothness. However, ETPS prevents swaps that would disrupt superpixel connectivity and adopts a coarse-to-fine approach similar to SEEDS, enabling real-time optimization and better results. Comparative experiments show that ETPS excels at generating regular superpixels that closely adhere to image contours. Notable examples in this category include VCells [22] and CCS [23].

The second type employs region-growing strategies, where superpixels expand from seed locations until all pixels are classified or a termination condition is met. Many algorithms in this category are based on the watershed transform (WT), a classic region-growing segmentation method. While WT can directly generate superpixels, its original formulation lacks regularity. The compact watershed algorithm [24] addresses this by adding a compactness term to the distance function. The waterpixel [25] regularizes the gradient map of the watershed by considering the spatial distances between pixels and markers. Additionally, the method in [26] enhances image quality through morphological reconstruction before applying the watershed transform. Other notable region-growing algorithms include TurboPixel [27], which uses boundary curvature and local contour intensity to guide flow velocity, and NICE [28], a non-iterative clustering framework with efficient priority queue implementation that can ensure superpixel connectivity when evolving the centroids.

2.3. Graph-Based Algorithms

Graph-based algorithms treat the image as a graph, where each pixel is a vertex and neighboring pixels are connected by edges. Various techniques are then used to partition the graph and create superpixel segmentations. While many graph-based algorithms [29,30] achieve high accuracy in capturing image details, they often produce irregular superpixels due to the lack of spatial features in their representations. One notable exception is the graph-cut-based approach introduced in [31], which partitions the pixel graph based on normalized cut criteria. This method can generate highly regular superpixels with good boundary adherence, but its high computational complexity limits its application to large images. Another exception is the superpixel lattice algorithm [32], which recursively partitions the image using minimum-cost paths between image borders.By controlling the tortuosity of these paths, it regulates how much the superpixels deviate from regular grid structures.

2.4. Hierarchical Algorithms

A special category of algorithms creates a hierarchy of segmentations, consisting of layers of superpixels at different scales, with aligned boundaries across layers. This feature is crucial for many computer vision applications [33] that require multi-scale superpixels to accurately represent image structures. One example of a hierarchical algorithm is presented in [34], which is a hierarchical version of VCells. Another example is a graph-based approach [35], where the hierarchy is derived from the Borůvka’s algorithm. Additionally, some classical graph-based algorithms [29] can produce hierarchical segmentations through top-down or bottom-up processes. However, these hierarchies tend to be unbalanced, as traditional algorithms do not account for this aspect.

2.5. Deep-Learning-Based Algorithms

Recent advancements in deep learning have led to the development of algorithms that integrate superpixels with neural networks. These algorithms can be divided into three categories.

The first category applies traditional methods to image features extracted by neural networks. For example, a deep affinity learning network is used in [36] to aggregate multi-scale features, and then a graph-based algorithm is employed to compute superpixels from the learned affinities. Another example [37] combines a convolutional network with a mean-shift clustering module to compute pixel embeddings, which are then used in a non-iterative clustering framework to generate superpixels. In [38], superpixels with a lattice topology are generated by the coarse-to-fine refinement of superpixels’ boundaries under the guidance of a pretrained network. While these algorithms allow for some control over superpixel regularity, they are not fully end-to-end trainable since traditional methods are not integrated into the neural network architecture.

The second category directly predicts superpixel labels for pixels. These algorithms typically position superpixels on a regular grid and predict pixel associations with neighboring superpixels. The earliest example is the fully convolutional network, which computes predictions using a series of convolutional layers trained with a reconstruction cost function. This inspired further models, such as AINet [39], which includes an association implantation module to compute associations based on pixel and superpixel embeddings. On the other hand, the biological network in [40] supports the computation of an association map with enhanced screening modules, and the network is trained with boundary-aware labels to emulate human visual mechanisms. In a two-stage approach called ESNet [41], an image is first fed into a CNN-based feature extractor, and then a pyramid–gradient network is used to compute the pixel associations from the extracted features. An unsupervised method called LSN-Net [42] uses a non-iterative clustering module for soft pixel assignments to superpixels, along with a gradient rescaling module to prevent overfitting. More recently, a superpixel-based visual transformer [43] has predicted associations through cross-attention updates. While these algorithms effectively utilize neural networks to distinguish between pixel classes and are end-to-end trainable, they often produce superpixels with irregular shapes.

The third category features algorithms that incorporate differentiable modifications of classical superpixel methods, allowing for end-to-end training while maintaining better control over superpixel regularity. A notable example is the superpixel sampling network (SSN) [44], which makes SLIC differentiable and uses a deep network to learn pixel features. The SSN is trained with a combination of reconstruction and compactness loss functions to enhance regularity. An improvement, BP-Net [45], incorporates a boundary detection network to handle depth information in RGB-D images, and is trained with a block regularity loss function, resulting in highly regular superpixels.

3. Anisotropic Variational Fuzzy Superpixel Segmentation

The superpixel segmentation can be regarded as an unsupervised learning problem that divides an image with N pixels to K superpixels. In this paper, the following anisotropic variational fuzzy superpixel segmentation model is studied:

subject to

where is the partition matrix in which represents the association degree of membership of the ith pixel to the kth superpixel, is the collection of the centroids of superpixels, and is the parameter that controls the regularization. In (1), the first term, , represents the objective function of the FCM clustering model, which classifies pixels into fuzzy superpixels. The second term, , measures the total variation energy of the fuzzy membership function, enhancing the regularity of the superpixels. Notably, is an anisotropic version of the total variation energy, where anisotropy is derived from image contours. Unlike isotropic total variation, reduces the penalties for irregularities near contours, allowing the superpixels to better align with image boundaries. It is important to remark that anisotropic total variation regularization is being introduced for the first time in superpixel segmentation to enhance superpixel regularity. In what follows, the two energy terms are discussed in detail.

3.1. Dissimilarity Measurement and Feature Representation

The first energy term is the cost function of the FCM clustering model with the weighted Euclidean distance, defined as follows:

where is a feature vector of the ith pixel and is a dissimilarity measure between and . Since computational complexity is one of the most important issues in the application of superpixel segmentation, the spatial feature and CIELAB color are adopted for feature representation, i.e., . The element represents the spatial coordinates of the ith pixel while the other components correspond to the CIELAB color values of the same pixel. It is important to note that a spatial feature is utilized to enhance superpixel compactness, while the CIELAB color space is chosen for its perceptual uniformity in relation to human color vision, making it effective across various applications. Here, the dissimilarity measure is defined as a weighted Euclidean distance, where the weights assigned to the spatial feature are determined by a compactness parameter M > 0. Furthermore, to expedite the segmentation process, the computation of the dissimilarity measure is restricted to only those pixels that lie within the window centered at the centroid . This ensures that the radius of each superpixel does not exceed the predefined maximum radius . In other words, the dissimilarity measure is defined as follows:

where the first two terms are

while the last term,

penalizes the distance by ∞ if the pixel is too far away from the centroid.

3.2. Anisotropic Total Variation Regularization

The second energy term measures the regularity of the superpixels by considering the anisotropic total variation (ATV) of each superpixel. Here, the kth superpixel is treated as a monochromatic image . Mathematically, this energy term can be expressed as follows:

where denotes the eight neighbors of pixel i and represents the anisotropy at pixel i in the direction toward pixel . Additionally, the denominator in (4) is simply the spatial distance between pixel i and pixel j, which is used for the forward difference approximation of the directional derivatives.

The above is an anisotropic generalization of the well-known Rudin, Osher, and Fatem (ROF) functional [46]:

where is the image domain and is the gradient of u. In fact, our can be written as follows:

where A is the anisotropy tensor. Here, the anisotropy refers to the assignment of varying weights to different components of the gradient operator ∇, based on the specific image locations and the directions of these components.

In addition to anisotropy, another distinction between our and the original ROF functional is noteworthy. In the ROF framework and its discretization [47], the gradient operator ∇ comprises only two components, corresponding to the partial derivatives along the x- and y-axes. To achieve faster convergence and a more effective representation of anisotropy, an eight-directional is employed in this paper. In our formulation, the gradient at pixel i is calculated in eight directions corresponding to the eight neighboring pixels. For each direction , the th component of represents the directional derivative of u along that direction, which is discretized as follows:

where is the neighbor of the pixel i in the direction of .

It is essential to emphasize that anisotropy should not be calculated from the regularized outputs of the previous iteration, as this would add unnecessary overhead to each iteration of the optimization process. Additionally, image details such as edges and corners may be compromised due to over-smoothing during optimization, meaning that anisotropy derived from intermediate outputs may not adequately capture these crucial features. In rare cases, the coupling between anisotropy and intermediate outputs could even result in instabilities. This issue can be circumvented by precomputing the anisotropy from the input. This strategy aligns with our goal of regularizing the fuzzy membership function to enhance edge directions, rather than regularizing the input image itself.

For each neighboring pixel pair , the probability is first calculated so that an edge separates the two pixels by applying an edge detector to the input image.The anisotropy is then set as

to reduce the regularization of the fuzzy membership function across the edges. It is important to note that the anisotropy only needs to be computed once at initialization and is independent of the fuzzy membership function.

4. Optimization Procedure

The minimization of (1) with the energies (3) and (4) and the constraints (2) forms a class of constrained nonlinear optimization problems whose solutions are unknown. To efficiently optimize the energy functional subject to a set of constraints, the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) is applied to decouple the two energy terms in (1), which yields the following augmented Lagrangian:

where Y is the multiplier of the new constraint under the ADMM scheme, is the penalty parameter, and is the Frobenius norm. From , the ADMM scheme is used to iteratively update the following variables:

4.1. Fuzzy Membership Function

The solution to the sub-problem (10) under the constraints (2) can be obtained by solving the following problem for each pixel i:

where . The problem outlined above can be addressed using a similar technique as described in [48]. For each i, let be the reordering of the sequence in descending order. Define

and ; then, the solution to (12) is given by

4.2. Superpixel Centroid Adjustment

The sub-problem (11) can be derived by setting the corresponding partial derivatives of to 0. For each k, the solution is given by

4.3. Anisotropic Total Variation Minimization

Solving the sub-problem (8) is equivalent to addressing the following anisotropic total variation regularization problem for each k:

where . This problem can be solved based on the Chambolle’s fast duality projection algorithm [47]. However, to adapt it for our model, it is necessary to replace the two-directional gradient operator in [47] with our eight-directional anisotropic operator, denoted as . The component in the direction of at pixel i is defined as follows:

In the formula above, ∇ represents the isotropic gradient operator as defined in (6). The term denotes the neighbor of pixel i in the direction of , while refers to the anisotropy defined in (7). When applying Chambolle’s algorithm, the sub-problem (8) is solved as follows: Let be the adjoint of , and for each k, let the sequence be defined such that and

where ; then, the solution to (8) is given by the limit

It is important to note that the condition for convergence requires . This can be proven using techniques similar to those in [49], along with the fact that for all .

4.4. The Overall Implementation

While a larger number of ADMM iterations is usually necessary for algorithm convergence, only a few iterations are often sufficient for effective superpixel segmentation in practice. The required iterations can be significantly reduced if the variables are initialized close to the optimal solution. However, the careful selection of the initialization method is crucial, as it can greatly influence the final outcome. Using regular grids to initialize U may seem straightforward, but it can waste computational resources on unnecessary regularization, especially since centroids may shift significantly in the initial phase. A more effective approach is the coarse-to-fine initialization used by ETPS, which is efficient and typically yields solutions close to the optimum. The ETPS algorithm represents an image with a pyramid structure, approximating it with blocks of decreasing sizes at each level. It optimizes superpixel segmentation by minimizing the following objective function:

where the first two terms measure spatial and color dissimilarities between pixels and their assigned superpixels, the third term accounts for boundary lengths, and the last two terms impose penalties for disconnected and tiny superpixels, respectively. At each level, the algorithm iteratively exchanges boundary blocks between superpixels until a local optimum is reached, and then transitions to the next level to repeat the process with smaller blocks. This continues until the final level is reached, resulting in a refined initialization.

It is important to remark that the original ETPS initialization uses seed locations on a rectangular grid, which can maintain grid structure in homogeneous image regions. However, this approach can lead to instability with TV regularization due to four-corner singularities. To address this, it is proposed that the algorithm be initialized with seed locations on a hex grid, effectively eliminating these singularities. In our implementation, the parameters for the ETPS initialization are set to and , where M is the compactness parameter.

A pseudocode of the proposed algorithm is summarized below:

| Algorithm 1 Anisotropic Variational Fuzzy Superpixel Segmentation (AVFS) Algorithm |

|

The parameter MaxIter mentioned in Algorithm 1 indicates the number of iterations in the experiment. To visualize the segmentation results and compare the proposed method with the existing approaches, as reported in Section 5, the defuzzification process is performed by assigning the ith pixel to the th superpixel that maximizes the optimal fuzzy membership function, where .

5. Experiments

5.1. Experimental Settings

The proposed method is evaluated using the well-known Berkeley Segmentation Dataset 500 (BSDS500) [50], which comprises 200 test images (of size 481 × 321 or 321 × 481) depicting a variety of scenes, including humans, animals, buildings, and landscapes, along with multiple human-labeled ground truths. Unless otherwise specified, the parameters across all our experiments are fixed, as follows: , , , , , and , where represents the initial radius of the superpixel , and . To assess the effectiveness of our methodology, six evaluation metrics are employed: under-segmentation error (UE) [51], achievable segmentation accuracy (ASA) [52], boundary recall (BR) [53], contour density (CD) [25], compactness (CO) [3], and shape regularity criteria (SRC) [4]. The first two metrics evaluate how accurately the superpixels capture image objects in relation to the ground truths, the third metric assesses the alignment of superpixel boundaries with object boundaries, while the latter three metrics measure the regularity of the superpixels according to different criteria.

- Under-segmentation Error (UE)

The UE concerns how each superpixel is divided by a ground truth segmentation . It is defined as as follows:

- Achievable Segmentation Accuracy (ASA)

The ASA calculates the average of the largest overlaps between each superpixel and the corresponding ground truth segment, as follows:

- Boundary Recall (BR)

The BR measures the proportion of ground truth boundaries that are captured by superpixel boundaries. A ground truth boundary pixel p is classified as a true positive (TP) if any superpixel boundary falls within a window of size centered at p. Conversely, if no superpixel boundary is found within this window, the pixel p is classified as a false negative (FN) boundary pixel. For all experiments, is used. The calculation of BR is performed as follows:

where and represent the number of true positive and false negative ground truth boundary pixels, respectively.

- Contour Density (CD)

The BR metric might overestimate the performance of irregular superpixel algorithms due to the increased number of boundary pixels in such segmentations. To assess the credibility of the BR measure, the CD is also reported, defined as the ratio of the total number of superpixel boundary pixels B to the total number of image pixels N:

- Compactness (CO)

The CO calculates the average isoperimetric quotients of the superpixels throughout the image, as shown below:

where and represent the area and the perimeter of s, respectively. The CO favors superpixels that have circular shapes and smooth boundaries. Note that the perimeter is computed using the distance, meaning that the distance between two diagonally adjacent pixels is instead of 2, which is more favorable to superpixels with diagonal boundaries.

- Shape Regularity Criteria (SRC)

The study in [4] revealed that the CO measure is overly sensitive to boundary smoothness, making it difficult to differentiate regular shapes (like circles) with noisy boundaries from less regular shapes (such as ellipses). This limitation is addressed by the SRC metric, which compares a superpixel s to its convex hull . The SRC is computed, as follows:

where and , with being the two eigenvalues of the covariance matrix of the x, y-coordinates in s. Note that the ratio is computed differently from [4] to ensure rotation invariance.

5.2. Effectiveness of Anisotropy

The effectiveness of anisotropy is first examined on the performance of AVFS. For comparison, four contour detectors are selected: (i) the Prewitt detector, (ii) the Canny edge detector, (iii) the ultrametric contour map (UCM), and (iv) the structured edge (SE) detector [54]. Additionally, two special anisotropy cases are used as the baselines. The first is the trivial anisotropic (i.e., isotropic), where for any neighboring pixels i and j. The second is “perfect” anisotropy, where if and only if there is a ground truth (GT) edge between pixels i and j.

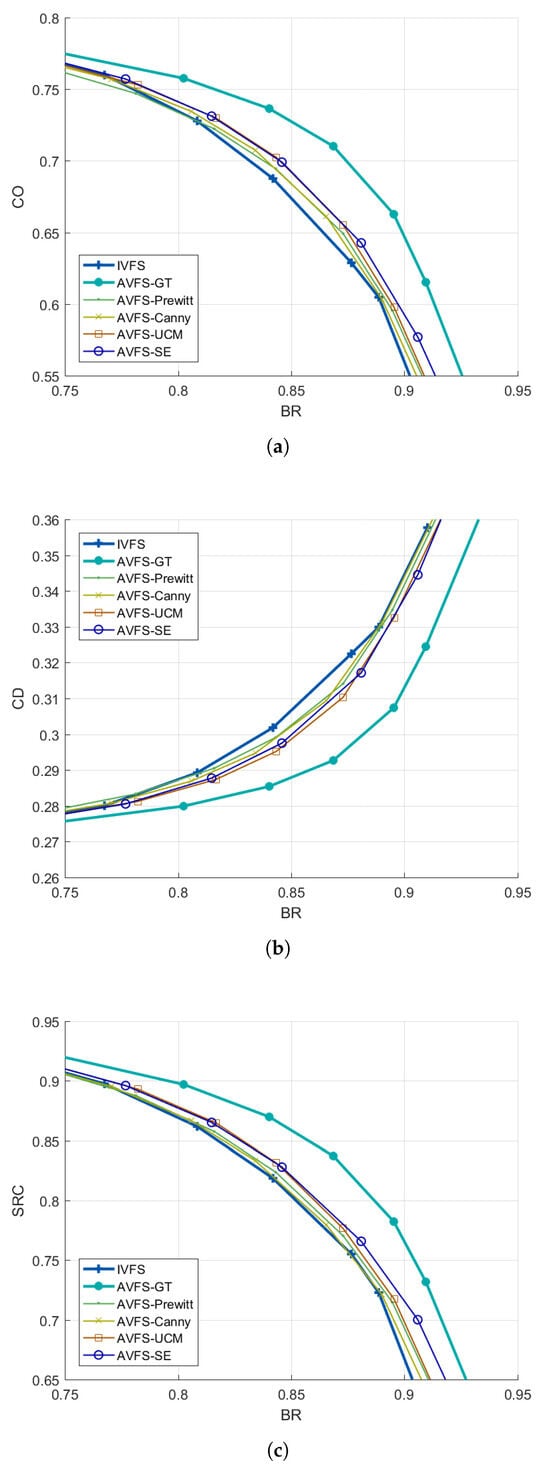

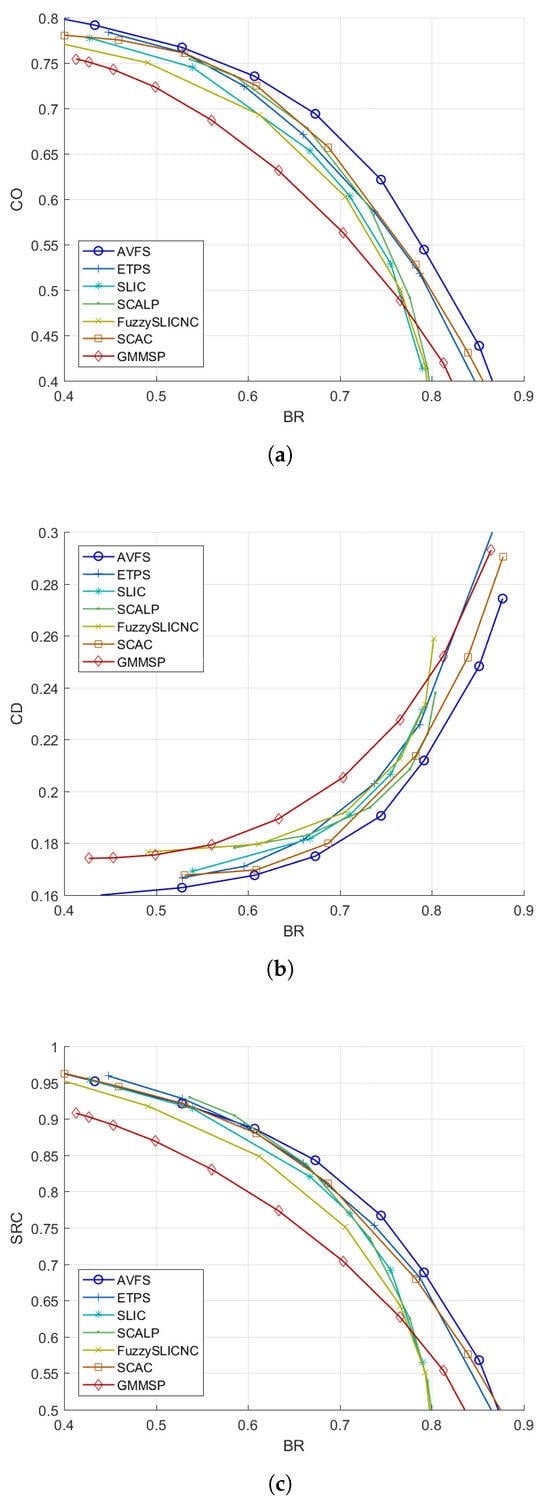

To illustrate the trade-off between boundary adherence and regularity, multiple superpixel segmentations are generated by varying the compactness parameter with and setting . Figure 1 displays the results, plotting the regularity metrics against boundary recall. Notably, the perfect anisotropy (AVFS-GT) significantly outperforms the isotropic model (IVFS), achieving better regularity at the same BR values. This suggests that the proposed AVFS algorithm can effectively balance boundary adherence and regularity when appropriate anisotropy is applied. Additionally, even basic contour detectors like Prewitt and Canny improve results compared to IVFS, while more advanced detectors like UCM and SE yield even better performance. This indicates that although the performance of AVFS is influenced by the quality of contour detectors, simple detectors are sufficient for improvement over the IVFS model, highlighting the value of anisotropy in our approach.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the trade-off between boundary adherence and regularity for the AVFS algorithm using different contour detectors: (a) BR-CO, (b) BR-CD, and (c) BR-SRC.

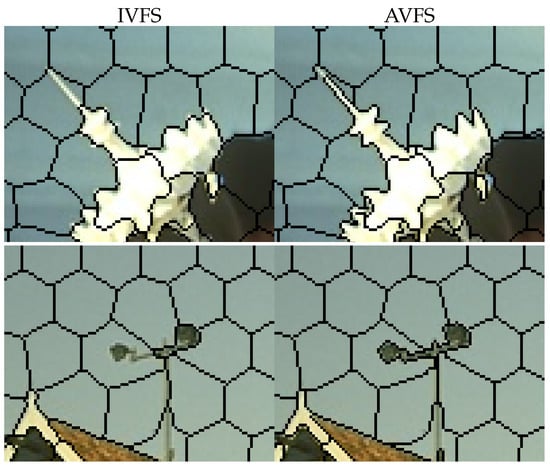

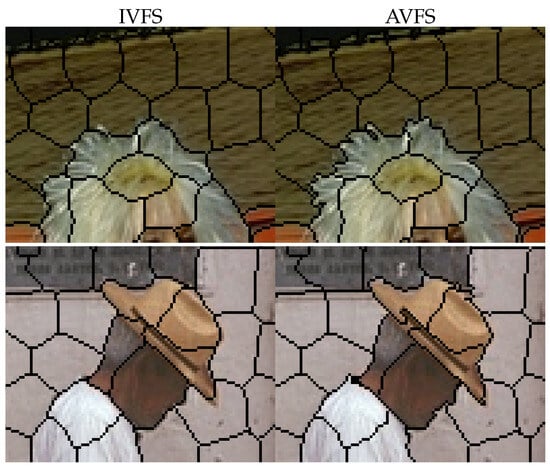

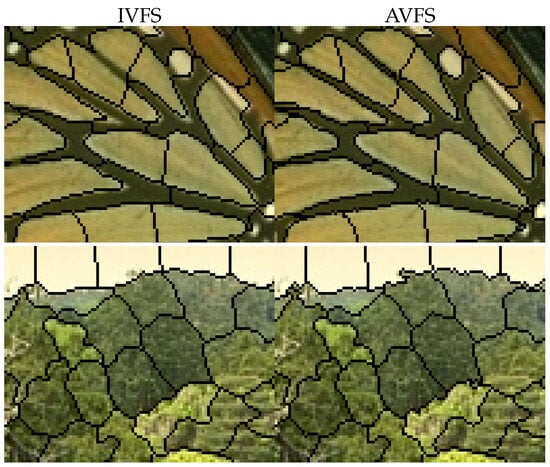

Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 present zoomed-in comparisons of IVFS and AVFS. In Figure 2, AVFS successfully captures small image objects, while IVFS misses parts of these objects due to over-regularization. Figure 3 demonstrates that AVFS effectively captures irregular shapes, such as the face in the second row, whereas IVFS struggles with over-smoothed boundaries. Additionally, Figure 4 highlights that AVFS adheres better to image edges, particularly at superpixel corners, which are overly smoothed in IVFS. Overall, AVFS preserves image details more effectively than IVFS without compromising regularity, underscoring the effectiveness of ATV in our model.

Figure 2.

Visual comparison of IVFS and AVFS algorithms in capturing small objects.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of the IVFS and AVFS algorithms in capturing irregular shapes.

Figure 4.

Visual comparison of boundary adherence between the IVFS and AVFS algorithms.

5.3. Comparative Results

In this subsection, the proposed AVFS algorithm is compared with the state-of-the-art regular superpixel methods, including hard-clustering-based SLIC and SCALP, soft-clustering-based GMMSP and fuzzy-SLICNC [19]. Boundary-based ETPS and SCAC [55] are also included. Note that the SE detector is used to calculate anisotropy.

Table 1 presents the average performance metrics of all algorithms for and . The proposed AVFS outperforms all other algorithms in SRC and CO, and ranks second in CD, highlighting the effectiveness of ATV in enhancing superpixel regularity. Additionally, AVFS achieves the highest BR, demonstrating its ability to maintain boundary adherence to image edges while improving superpixel regularity. In terms of segmentation accuracy, AVFS performs well on UE and ASA metrics, being only slightly behind the recently developed SCAC. Overall, these results indicate that our method effectively distinguishes between different image components, with ATV causing only a minor reduction in the segmentation accuracy.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of the proposed AVFS and regular superpixel algorithms.

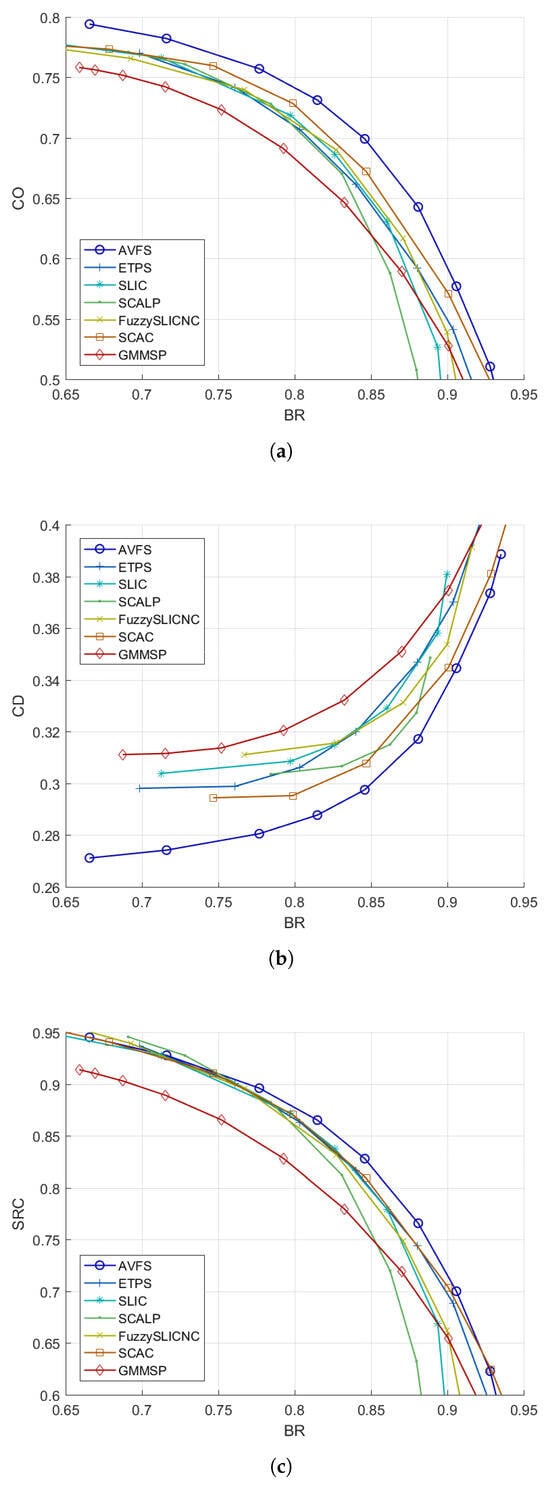

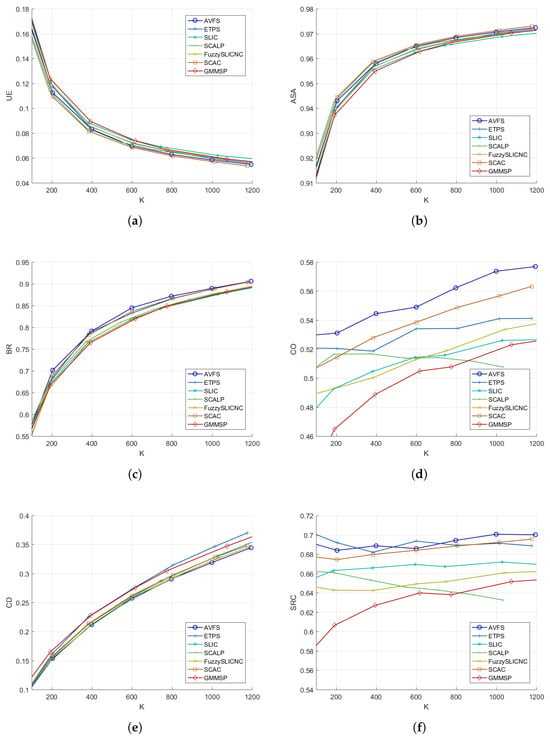

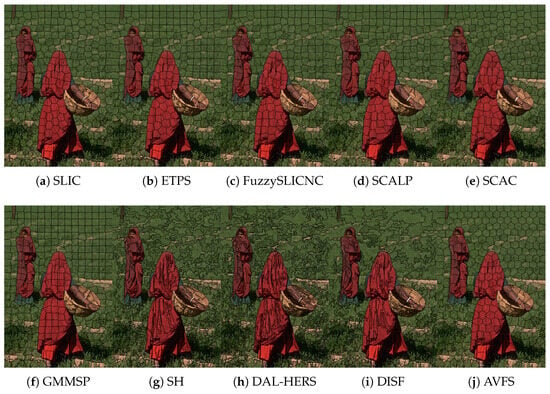

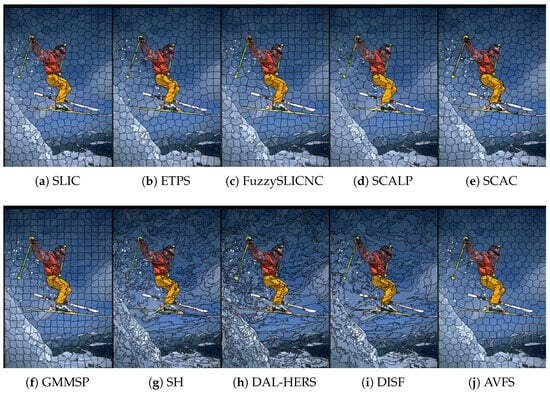

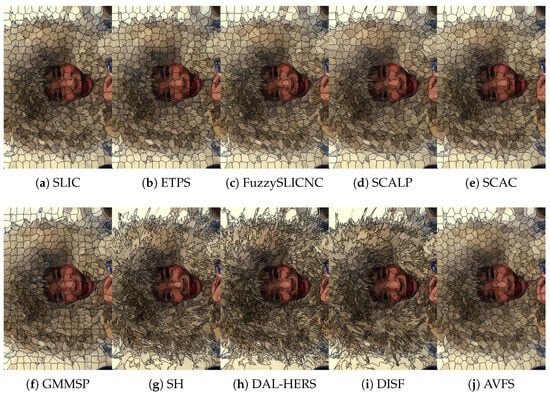

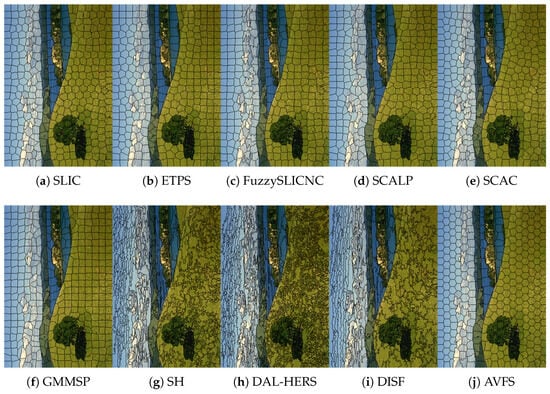

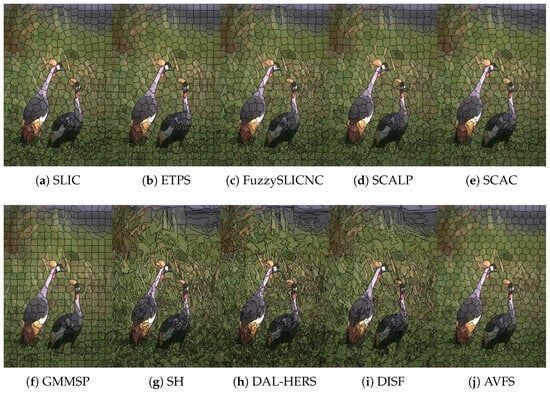

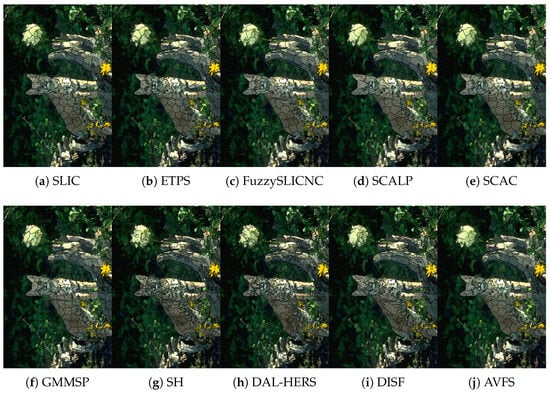

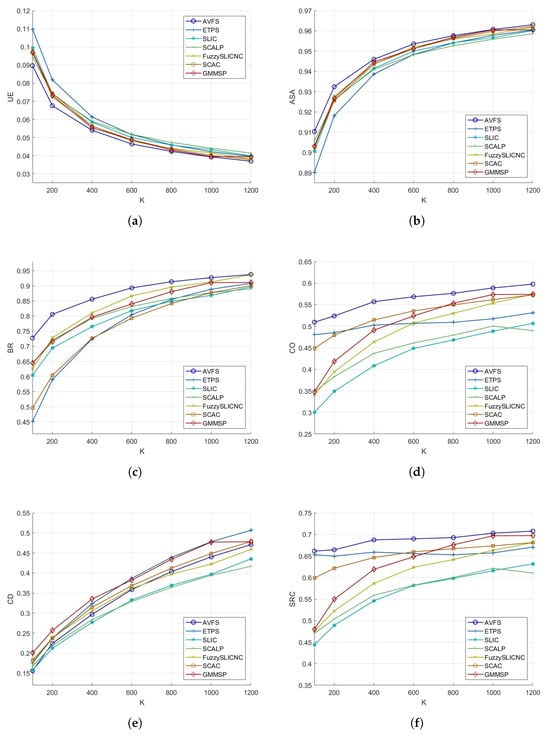

To further investigate the performance of regular superpixel algorithms in balancing boundary adherence and regularity, the parameters for each algorithm are fine-tuned and only the best results are reported. These findings are displayed in Figure 5 for and Figure 6 for . The figures clearly demonstrate that our AVFS significantly outperforms other algorithms in both CO and CD as the BR–CO and BR–CD curves for AVFS consistently surpass those of the competing algorithms. Additionally, AVFS achieves the highest SRC across a broad range of BR ( for and for ), though SCALP and SCAC perform slightly better at lower and higher BR values. Figure 7 illustrates the average performance metrics across varying numbers of superpixels K, from 100 to 1200, revealing that AVFS excels in BR and all regularity metrics while maintaining competitive in accuracy metrics. In Table 2, AVFS is compared with other superpixel algorithms that have limited regularity control, including graph-based SH [35], DISF [30], and the deep-learning-based DAL-HERS [36]. Although the irregular algorithms may yield slightly better accuracy metrics than AVFS, the regularity metrics clearly indicate that AVFS produces significantly more regular superpixels. Finally, the visual examples in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 demonstrate that AVFS effectively generates regular superpixels that adhere well to object boundaries.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the trade-off between boundary adherence and regularity for different algorithms with : (a) BR-CO, (b) BR-CD, and (c) BR-SRC.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the trade-off between boundary adherence and regularity for different algorithms with : (a) BR-CO, (b) BR-CD, and (c) BR-SRC.

Figure 7.

Average performance metrics for different algorithms across various number of superpixels: (a) UE, (b) ASA, (c) BR, (d) CO, (e) CD, and (f) SRC.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of the proposed AVFS and irregular superpixel algorithms.

Figure 8.

Visual example one of various algorithms for .

Figure 9.

Visual example two of various algorithms for .

Figure 10.

Visual example three of various algorithms for .

Figure 11.

Visual example four of various algorithms for .

Figure 12.

Visual example five of various algorithms for .

Figure 13.

Visual example six of various algorithms for .

To further validate our proposed algorithm, experiments were conducted using the Stanford Background Dataset (SBD dataset) [56], which consists of 715 images (approximately 320 × 240 pixels) depicting urban and rural scenes from various public image collections. The results, presented in Table 3, demonstrate the superior performance of our algorithm across multiple evaluation metrics, including UE, ASA, BR, CO, and SRC. These findings highlight our algorithm’s exceptional ability to adhere to image edges while improving superpixel regularity. In terms of accuracy metrics, AVFS also outperforms other algorithms. Additionally, Figure 14 shows the average performance metrics for varying numbers of superpixels (from 100 to 1200). Overall, these results consistently illustrate AVFS’s superior segmentation accuracy, boundary adherence, and superpixel regularity compared to competing algorithms.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison of the proposed AVFS and regular superpixel algorithms (SBD dataset).

Figure 14.

Average performance metrics for different algorithms across various number of superpixels (SBD dataset): (a) UE, (b) ASA, (c) BR, (d) CO, (e) CD, and (f) SRC.

5.4. Computational Cost

All experiments were conducted on a laptop equipped with an Intel Core i7-6700HQ (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 960 M (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The proposed algorithm has a computational complexity of , with the factor arising from sorting N queues of pixels when calculating the fuzzy membership function. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 present the average computation times for all algorithms at and . As can be seen, SH and SLIC are the fastest, as the former uses a region-merging technique that grows regions in a Borůvka fashion, while the latter employs a standard k-means clustering with simple image features. Other algorithms typically generate superpixels with computation times of around or less than 1.0 s per image. The computational cost of our proposed method is primarily influenced by the optimization process, resulting in a total superpixel generation time of approximately 0.6 s, which is deemed satisfactory.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a fuzzy superpixel segmentation algorithm based on content-adaptive anisotropic total variation regularization. By aligning superpixels with image contours, the model enhances regularity while preserving fine details in regions with high contour density. Unlike conventional methods that use non-adaptive regularization, our approach maintains strong adherence to image edges without sacrificing regularity. As a result, the geometry of the generated superpixels can serve as informative features for downstream tasks. In contrast, many existing models produce superpixels that are either overly irregular or oversmoothed, limiting the usefulness of their geometry. Consequently, our algorithm provides a more informative image representation that can improve the performance of a wide range of superpixel-based applications.

To optimize the proposed functional effectively, an efficient alternating direction method of multipliers in conjunction with an enhanced Chambolle’s fast duality projection algorithm are adopted. The experimental results show that our method outperforms state-of-the-art approaches, producing more regular superpixels with better boundary adherence and higher segmentation accuracy.

Nevertheless, our algorithm has several limitations. First, it must solve the total variation regularization sub-problem (8), which can be computationally expensive. The fuzzy membership sub-problem (13) requires the local sorting of the sequence , which can become a bottleneck in practice. In addition, the anisotropy term depends on the chosen edge detector and can be degraded by image noise. To improve computational efficiency, fast approximate solvers for each sub-problem are worth exploring. Moreover, an improved anisotropy design via coupled optimization could enhance the adaptability to the image contents. Finally, integrating the algorithm into a deep learning framework may enable richer feature representations and more sophisticated superpixel modeling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C.N., S.K.C., M.L.T., V.R. and S.Y.L.; methodology, T.C.N., S.K.C., M.L.T., V.R. and S.Y.L.; software, T.C.N.; formal analysis, T.C.N.; investigation, T.C.N.; data curation, T.C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.N.; writing—review and editing, T.C.N., S.K.C., M.L.T., V.R. and S.Y.L.; visualization, T.C.N.; supervision, S.K.C., M.L.T., V.R. and S.Y.L.; and funding acquisition, S.K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work described in this paper was partially supported by the Research Matching Grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administration Region, China (Project: 700006 Applications of SAS Viya in Big Data Analytics).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Berkeley Segmentation Dataset 500 at https://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Research/Projects/CS/vision/bsds (accessed on 19 January 2026). These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: Stanford Background Dataset; http://dags.stanford.edu/projects/scenedataset.html (accessed on 19 January 2026).

Acknowledgments

The worked described in the paper was supported by the Big Data Intelligence Centre of The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Huang, S.; Liu, Z.; Jin, W.; Mu, Y. Superpixel-based multi-scale multi-instance learning for hyperspectral image classification. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 149, 110257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Cao, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z. TSAR-MVS: Textureless-aware segmentation and correlative refinement guided multi-view stereo. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 154, 110565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, A.; Fischer, M.; Stiefelhagen, R. Measuring and evaluating the compactness of superpixels. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR2012), Tsukuba, Japan, 11–15 November 2012; pp. 930–934. [Google Scholar]

- Giraud, R.; Ta, V.T.; Papadakis, N. Robust shape regularity criteria for superpixel evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3455–3459. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos, I.B.; Belém, F.D.C.; João, L.D.M.; Patrocínio, Z.K.G.D.; Falcão, A.X.; Guimarães, S.J.F. A Comprehensive Review and New Taxonomy on Superpixel Segmentation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yan, H. A survey of superpixel methods and their applications. TechRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Tuzel, O.; Ramalingam, S.; Chellappa, R. Entropy-Rate Clustering: Cluster Analysis via Maximizing a Submodular Function Subject to a Matroid Constraint. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 36, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bergh, M.; Boix, X.; Roig, G.; Van Gool, L. Seeds: Superpixels extracted via energy-driven sampling. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 111, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, R.; Shaji, A.; Smith, K.; Lucchi, A.; Fua, P.; Süsstrunk, S. SLIC Superpixels Compared to State-of-the-Art Superpixel Methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 34, 2274–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, Y.J. Content-adaptive superpixel segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 2883–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Boben, M.; Fidler, S.; Urtasun, R. Real-time coarse-to-fine topologically preserving segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2947–2955. [Google Scholar]

- Perona, P.; Malik, J. Scale-space and edge detection using anisotropic diffusion. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1990, 12, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Malik, J. Learning a classification model for segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Ninth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Nice, France, 13–16 October 2003; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, B. Linear Spectral Clustering Superpixel. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3317–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, R.; Ta, V.T.; Papadakis, N. Robust superpixels using color and contour features along linear path. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2018, 170, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Lei, C.; Wang, J. Multiscale Superpixel Segmentation With Deep Features for Change Detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 36600–36616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Fan, J.; Xu, X.; Xie, G. Adaptive Superpixel Segmentation With Non-Uniform Seed Initialization. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2025, 11, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiao, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, F.; Hua, W. Fuzzy Superpixels for Polarimetric SAR Images Classification. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 26, 2846–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zheng, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Yan, H. Fuzzy SLIC: Fuzzy Simple Linear Iterative Clustering. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Z.; Liu, J.; Cao, L. Superpixel Segmentation Using Gaussian Mixture Model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 4105–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; McAllester, D.; Urtasun, R. Efficient Joint Segmentation, Occlusion Labeling, Stereo and Flow Estimation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 756–771. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. VCells: Simple and Efficient Superpixels Using Edge-Weighted Centroidal Voronoi Tessellations. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 34, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasli, H.E.; Cigla, C.; Alatan, A.A. Convexity constrained efficient superpixel and supervoxel extraction. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2015, 33, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, P.; Protzel, P. Compact Watershed and Preemptive SLIC: On Improving Trade-offs of Superpixel Segmentation Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2014 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Stockholm, Sweden, 24–28 August 2014; pp. 996–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Machairas, V.; Faessel, M.; Cárdenas-Peña, D.; Chabardes, T.; Walter, T.; Decencière, E. Waterpixels. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 3707–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Meng, H.; Nandi, A.K. Superpixel-Based Fast Fuzzy C-Means Clustering for Color Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 27, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinshtein, A.; Stere, A.; Kutulakos, K.N.; Fleet, D.J.; Dickinson, S.J.; Siddiqi, K. TurboPixels: Fast Superpixels Using Geometric Flows. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2009, 31, 2290–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Guo, B.; Wang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, W. NICE: Superpixel Segmentation Using Non-Iterative Clustering with Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzenszwalb, P.F.; Huttenlocher, D.P. Efficient Graph-Based Image Segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 59, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belém, F.C.; Guimarães, S.J.F.; Falcão, A.X. Superpixel Segmentation Using Dynamic and Iterative Spanning Forest. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2020, 27, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Malik, J. Normalized cuts and image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 888–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.P.; Prince, S.J.D.; Warrell, J.; Mohammed, U.; Jones, G. Superpixel lattices. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23–28 June 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pont-Tuset, J.; Arbeláez, P.; T. Barron, J.; Marques, F.; Malik, J. Multiscale Combinatorial Grouping for Image Segmentation and Object Proposal Generation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ju, L.; Wang, S. Multiscale Superpixels and Supervoxels Based on Hierarchical Edge-Weighted Centroidal Voronoi Tessellation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yang, Q.; Gong, Y.; Ahuja, N.; Yang, M.H. Superpixel Hierarchy. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 4838–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Rivero, A.I.A.; Schonlieb, C.B. HERS Superpixels: Deep Affinity Learning for Hierarchical Entropy Rate Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.03755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, U.; Manjunath, B.S. Superpixel Embedding Network. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 3199–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Fast Generation of Superpixels With Lattice Topology. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 4828–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Qian, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Y. AINet: Association Implantation for Superpixel Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 7058–7067. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Peng, B.; Sun, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X. Rethinking superpixel segmentation from biologically inspired mechanisms. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 156, 111467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wei, S.; Ruan, T.; Zhao, Y. ESNet: An Efficient Framework for Superpixel Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 5389–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; She, Q.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, D.; Hu, J. Learning the Superpixel in a Non-iterative and Lifelong Manner. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1225–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.Z.; Mei, J.; Qiao, S.; Yan, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, L.C.; Kretzschmar, H. Superpixel Transformers for Efficient Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; pp. 7651–7658. [Google Scholar]

- Jampani, V.; Sun, D.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Kautz, J. Superpixel Sampling Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, X.; Ming, A. BP-net: Deep learning-based superpixel segmentation for RGB-D image. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 7433–7438. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, L.I.; Osher, S.; Fatemi, E. Nonlinear total variation based noise removal algorithms. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1992, 60, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambolle, A. An algorithm for total variation minimization and applications. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2004, 20, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Carreira-Perpiñán, M. Projection onto the probability simplex: An efficient algorithm with a simple proof, and an application. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1309.1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, M.; Kiriyama, S.; Goto, T.; Hirano, S. Fast algorithm for total variation minimization. In Proceedings of the 2011 18th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 11–14 September 2011; pp. 1461–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Arbelaez, P.; Maire, M.; Fowlkes, C.; Malik, J. Contour Detection and Hierarchical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubert, P.; Protzel, P. Superpixel benchmark and comparison. In Proceedings of the Forum Bildverarbeitung; KIT Scientific Publishing: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2012; Volume 6, pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Tuzel, O.; Ramalingam, S.; Chellappa, R. Entropy rate superpixel segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2011, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 2011; pp. 2097–2104. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.R.; Fowlkes, C.C.; Malik, J. Learning to detect natural image boundaries using local brightness, color, and texture cues. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2004, 26, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Structured Forests for Fast Edge Detection. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 1841–1848. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Zhu, Z. Superpixels With Content-Adaptive Criteria. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 7702–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.; Fulton, R.; Koller, D. Decomposing a scene into geometric and semantically consistent regions. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 29 September–2 October 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.