Abstract

An adaptive control strategy is developed and analyzed for trajectory tracking of mechanical systems subject to simultaneous model uncertainties and full-state constraints. To overcome the significant hurdle of guaranteeing both transient and steady-state performance within a user-defined time, a novel predefined-time adaptive neural network (NN) control scheme is proposed. By integrating predefined-time stability theory with a nonlinear mapping framework, a control scheme is developed to rigorously enforce full-state constraints while achieving predefined-time convergence. Radial basis function neural networks (RBFNNs) are employed to approximate the unknown system dynamics, with adaptive laws designed for online learning. The nonlinear mapping is strategically incorporated to ensure that the full-state constraints are never violated throughout the entire operation. Furthermore, through Lyapunov stability theory, it is proved that all signals of the resulting closed-loop system are uniformly ultimately bounded, and most importantly, the trajectory tracking error converges to a small neighborhood of zero within a predefined time, which can be explicitly set regardless of initial conditions. Comparative simulation results on a representative mechanical system are provided to demonstrate the superiority of the proposed controller, showcasing its faster convergence, higher tracking accuracy, and guaranteed constraint satisfaction compared to conventional finite-time and adaptive NN control methods.

Keywords:

predefined-time control; full-state constraints; mechanical systems; adaptive neural networks MSC:

93C10; 93C40; 37N35

1. Introduction

Mechanical systems in practical applications are often subject to unknown dynamics and external disturbances due to constantly changing operating conditions and unpredictable environments, and they frequently exhibit complex nonlinear behavior [1,2,3]. The precise trajectory tracking control of mechanical systems represents a cornerstone of modern automation [4]. This capability, essential for robotic manipulators, autonomous vehicles, and aerospace platforms, has been a central research challenge in control engineering for decades, remaining a highly active field [5,6,7]. The primary objective is to synthesize a control law that ensures the system’s output accurately tracks a desired trajectory. This is challenging in real-world applications, where model uncertainties and external disturbances are ubiquitous and can degrade performance or destabilize the system [8,9].

Control systems are fundamental to modern mechanical engineering, acting as the core intelligence for achieving precise, efficient, and autonomous machine operation [10,11,12]. Sliding mode control provides robust and precise tracking for mechanical systems despite model uncertainties and external disturbances [13,14,15]. Extremum seeking control automatically and continuously tunes a mechanical system’s parameters to optimize its performance in real-time, without requiring an exact model [16,17]. Given that safe operation requires all key state variables and control inputs to remain within strict bounds, it follows that constraint control is an indispensable component of the control architecture [18].

For nonlinear constrained control, the nonlinear mapping method [19,20] greatly simplifies both controller design and Lyapunov-based stability analysis by transforming the system into a new space where a standard quadratic Lyapunov function suffices, thereby avoiding the complexity and conservatism of direct methods like barrier Lyapunov functions (BLFs) [21,22,23]. However, a central drawback of these methods is that they address full-state constraints by recasting them as bounds on the tracking error, thereby imposing “feasibility conditions” on the virtual control laws. Dynamic Surface Control (DSC) serves as the standard solution to mitigate the “feasibility conditions” encountered in the design of virtual control laws [24,25]. In contrast, the proposed universal composite barrier function is capable of simultaneously enforcing both tracking error and full-state constraints, while circumventing these “feasibility conditions” [26]. The need for such constrained operation further underscores the importance of temporal predictability, making predefined-time control theory a pertinent framework for the overall design. Key lemmas in predefined-time control can be broadly classified into types such as the time-varying scaling lemma [27,28] and the Lyapunov-based lemma [29].

Owing to the universal approximation property, adaptive neural network control (ANNC) has emerged as a powerful data-driven technique for counteracting unknown dynamics and external disturbances, offering a formidable methodology for robust control [30,31,32]. A substantial body of literature on this paradigm provides stability guarantees by deriving adaptive laws that yield uniform ultimate boundedness (UUB) of the closed-loop error dynamics. Traditional linear control yields asymptotic stability, where error vanishes only as time approaches infinity [33,34]. Finite-time control ensures convergence within a finite duration, but this duration is initial-state dependent [35,36,37]. Fixed-time control overcomes this limitation by enforcing a uniform settling-time upper bound [38,39,40]. This progression culminates in predefined-time control, which empowers users to explicitly set this bound as a tunable parameter for the highest convergence-time precision [41,42,43]. The adaptive law serves as the cornerstone of neural network adaptive control architectures [44,45]. It is the foundational component that enables the online learning and adaptation essential for managing highly complex, nonlinear systems with significant uncertainties [46,47,48].

While significant progress has been made in each of these areas independently, the integration of all three aspects—predefined-time convergence, full-state constraint satisfaction, and adaptation to uncertainties via NNs—for mechanical systems presents a complex and non-trivial control problem. Therefore, there remains a clear gap for a control methodology that delivers the precision of predefined-time convergence while simultaneously guaranteeing safety through constraint enforcement and robustness through online adaptation.

Motivated by the above discussion, a novel predefined-time adaptive neural network control scheme for mechanical systems with full-state constraints is proposed. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- 1.

- An integrated control scheme is developed in this work, which incorporates an adaptive neural network controller. This design unifies the principles of predefined-time stability theory with the framework of nonlinear mapping techniques, thereby ensuring strict adherence to all full-state constraints and achieving convergence within a user-specified time.

- 2.

- Lyapunov stability analysis confirms that both the tracking error and the neural network approximation error are uniformly bounded and converge to a compact set around zero within a predefined time. This predefined time, which serves as an explicitly settable upper bound for the system convergence, is independent of the initial conditions.

- 3.

- The design of a bounded controller by modulating its rate enhances both the stability and rapidity of the system response. This strategy improves dynamic performance and ensures the generation of smooth control signals, thereby reducing mechanical stress on the actuator. Ultimately, it upholds control accuracy and strengthens the overall reliability and robustness of the system.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the problem formulation and necessary preliminaries on predefined-time stability and neural networks. The main controller design and stability analysis are detailed in Section 3. Section 4 presents comparative simulation results to validate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

Notation: The following notation throughout this paper. indicate ideal weight, estimation weight and error of neural networks, and .

2. Preliminaries

A class of uncertain mechanical systems is considered as following:

where vector , and denote the generalized position, velocity and acceleration vectors, respectively. () is the generalized inertia matrix, is the generalized centripetal-Coriolis matrix, is the generalized gravity vector, is the generalized disturbance vector, including the unmodeled effect and external disturbance; represents the generalized control input. The reference trajectory and its derivatives are bounded.

The inertia matrix is symmetric and positive definite, and for all and satisfies

where are positive scalars.

The NN is used to approximate on a compact set as following:

and

where and are the ideal weight vector and the radial basis function, respectively, and is a bounded approximation error. According to the universal approximation theorem, for any continuous function under certain conditions, ε can be made arbitrarily small provided that the number of radial basis neurons is sufficiently large.

Definition 1

([43]). For the origin of the system

with a predefined time , the system (5) is said to be predefined time stable, if the solution hold when .

Definition 2

([43]). The system (5) is said to be practical predefined time stable with a predefined time , if there is a positive constant , such that the solution satisfies for any .

Lemma 1

([43]). Consider the nonlinear system (5), if there exists a unbounded positive definite function such that the solution satisfies

where , , and is the circumference ratio, then, the system (5) is predefined time stable with predefined time .

Lemma 2

([43]). Consider the nonlinear system (5), if there exists a unbounded positive definite function such that the solution satisfies

where , , is the circumference ratio and is a nonnegative constant. Then, the system (5) is practical predefined time stable with predefined time , and remain in a bounded set for .

Lemma 3

([44]). For vector , where real numbers is positive numbers and satisfied , , , the following inequations hold:

Lemma 4

([45]). For , let , then the following inequality holds:

where .

3. Main Results

The objective is to achieve predefined-time trajectory tracking control for a mechanical system with full-state constraints using neural networks. Accordingly, the tracking errors are defined , then system (1) can be change as:

To address the state constraints, the nonlinear mapping method is proposed as

thus, by applying the nonlinear mapping technique, the controller trajectory is converted into a new state that satisfies the constraints

where parameters are positive constant to satisfied states and input constrain as . The reference trajectory is converted into a new state that satisfies the constraints

Therefore, the system can be change as

where

For system (15), the backstepping control method is designed, definite the tracking error

from (15), differentiate error state as

The virtual control input chosen for this step is defined as

then the dynamics of is gotten as

where are positive parameters, the parameters are satisfied , and determined later, and define the error state as

Choose a Lyapunov function candidate as

Taking derivative of (24) yields the following:

From (15) and (23), differentiate error state as

For the unknown nonlinear term , RBF NNs are employed to approximate the nonlinear function over a compact set , such that

where stands for RBFNNs weight vector, denotes the RBFNNs vector, is the approximation error satisfying

Choose the control as

where are positive parameters, then the dynamics of is gotten as

where define the error state as

Choose a Lyapunov function candidate as

taking derivative of (32) yields the following:

Because

then we have

The adaptive law of is designed as

where are positive parameters, then we have

From (15) and (31), differentiate error state as

For the unknown nonlinear term , RBF NNs are employed to approximate the nonlinear function over a compact set , such that

where stands for RBFNNs weight vector, denotes the RBFNNs vector, is the approximation error satisfying .

Design the control as

then we have

Choose a Lyapunov function candidate as

taking derivative of (42) yields the following:

because

then we have

the adaptive law of is designed as

where are positive parameters, then we have

Theorem 1.

Consider the uncertain mechanical systems (1), based on systems transformation (11) and nonlinear mapping (12), (13), then design the virtual control inputs (21), (29), (40) and neural networks (26), (39) with adaptive laws (36), (46), the close-loop error system (15) is practical predefined time stable, and the tracking error converges to a neighborhood of zero within the predefined time .

Proof.

Based on (24), (32), (42), choose a Lyapunov function candidate as

Taking derivative of (48) yields the following:

Based on (25), (37), (47) and Lemma 4, we have

based on Lemma 3, we have

and

then, based on (50), (51) and (52)

where

then, choose

then, based on Lemma 3

then, based on Lemma 2, the system is practical predefined time stable with predefined time , and remain in a bounded set for . □

Remark 1.

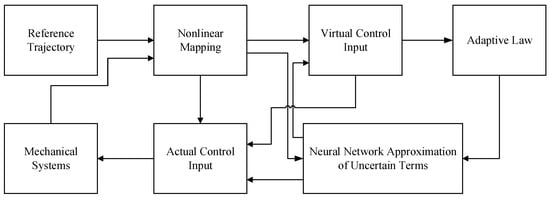

A schematic control flow diagram of the proposed PT NNs control process is presented in Figure 1. This diagram systematically illustrates the mechanical systems neural networks control process designed to achieve PT trajectory tracking. The process begins with nonlinear mapping of mechanical systems and reference trajectory, which are the processed by a bounded system to generate an unbounded system. In this framework, the uncertain terms are approximated by neural networks. A critical feedback path, which leverages these neural networks with an adaptive law, is then designed to connect the virtual control input to the actual control input. This visual representation serves a dual purpose: it clarifies the interdependencies among all components and establishes a foundational reference for the detailed algorithmic discussions and stability analysis that follow.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the PT NNs control process.

Remark 2.

The nonlinear mapping framework proposed in this study provides a fundamental approach to addressing the core control challenges outlined. Unlike traditional methods based on bounded Lyapunov functionals, this framework employs a coordinate transformation at the initial stage to map the original system into an unconstrained virtual design space. Within this space, well-established unconstrained control design theories can be fully utilized for controller synthesis. The design results are then naturally translated back into the actual control law in the original constrained space via the inverse mapping. This process establishes a systematic design paradigm for handling complex hard constraints.

The method inherently provides an analytic, feedforward pathway for constraint handling. The mapping function is computed in closed form and is fully analytical, eliminating the need for online iterative optimization and thereby avoiding associated computational burdens and real-time feasibility issues. Notably, the framework integrates neural network-based adaptive control, which enhances the system’s learning and adaptation capabilities without introducing additional complexity to the overall control algorithm. This characteristic is particularly crucial for fast dynamic systems requiring high-frequency updates, enabling reliable and high-performance constrained control even on embedded platforms with limited computational resources. Consequently, the framework offers a coherent path to solving constrained control problems that combines theoretical rigor with practical applicability.

4. Simulation

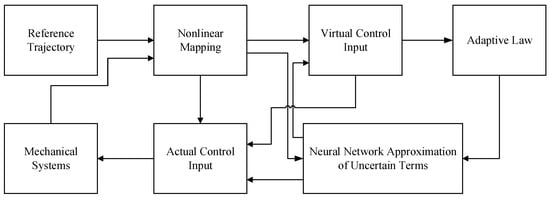

Consider mechanical system the vehicle with an inverted pendulum hinged to the center [46] as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mechanical vehicle with inverted pendulum.

The equation of motion can be written in matrix as

where

and the parameters .

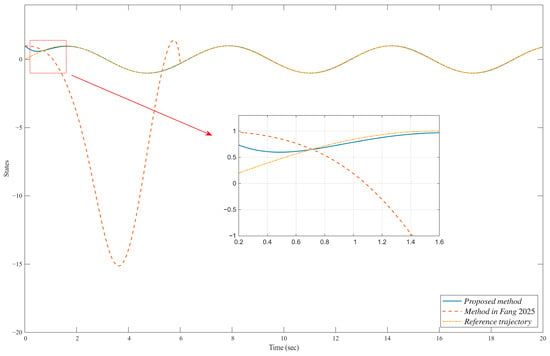

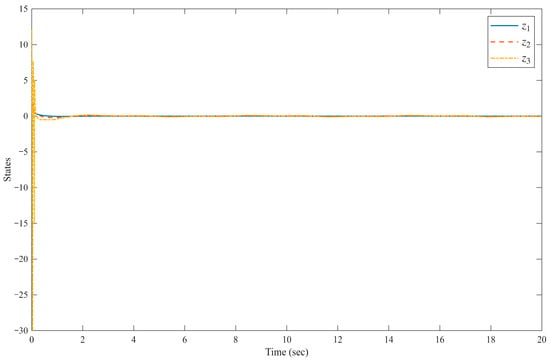

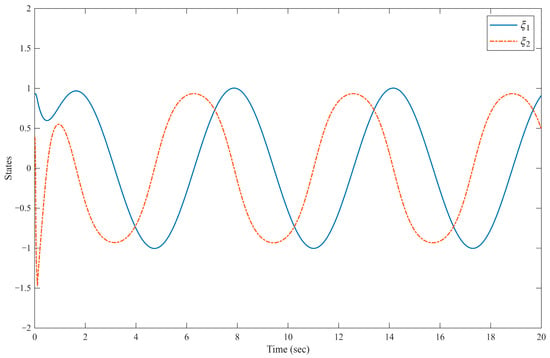

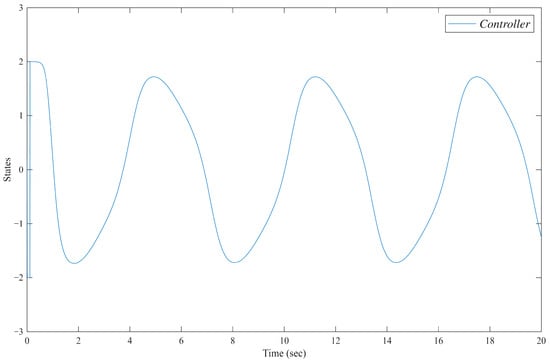

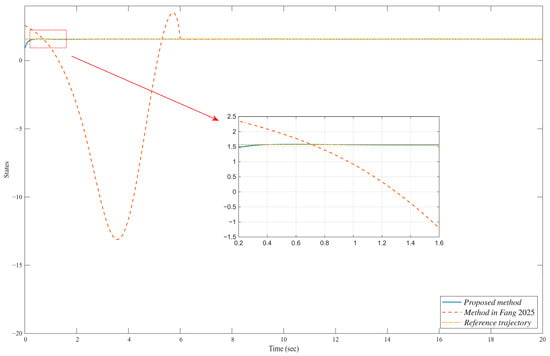

Compared to the approach in [47], the simulation results demonstrate a clear advantage and validate the feasibility of our algorithm in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 3.

System output and reference trajectory.

Figure 4.

System errors states .

Figure 5.

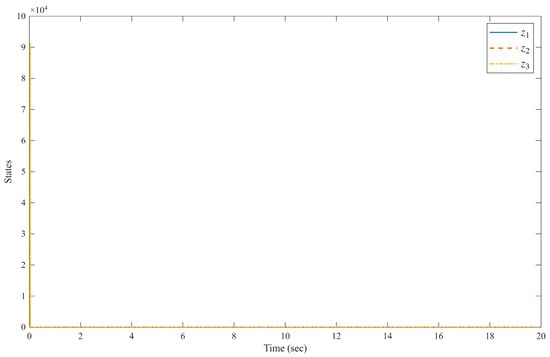

System states .

Figure 6.

System controller.

Figure 7.

System output and reference trajectory.

Figure 8.

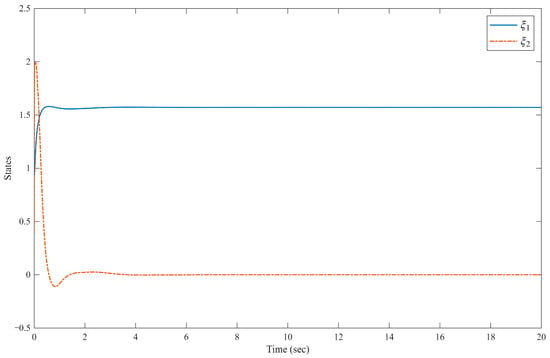

System errors states .

Figure 9.

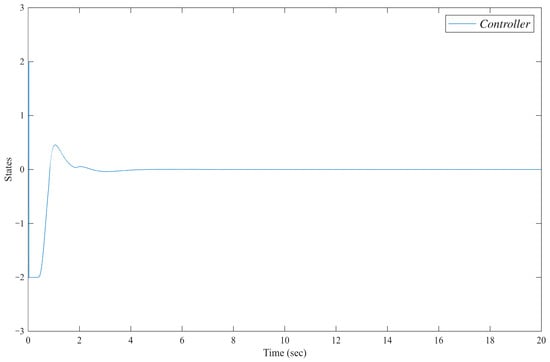

System states .

Figure 10.

System controller.

The system is divided into two parts; the evolution of state is illustrated in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, and that of state is depicted in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. The system output and its reference trajectory are presented in Figure 3, which also includes a comparative analysis with the control output from the method described in [47]. Based on controller parameters, the , therefore, the predefined-time convergence with . To explicitly prevent violations of the system constraints, a constraint control strategy is proposed in this work. The superior performance of our method in adhering to these limits is evident when compared to the baseline approach in [47]. Furthermore, the corresponding tracking errors of the closed-loop system are detailed in Figure 4, quantifying the convergence accuracy. Figure 5 and Figure 6 provide further insight into the system internal behavior, illustrating the state variables and the generated control inputs of the mechanical system, respectively. Simile results are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 for state .

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of performance metrics between the proposed control method and the approach reported in [37]. The evaluated metrics include convergence time, tracking error (both RMS and maximum), steady-state error, and control effort.

Table 1.

Comparison and Discussion with Existing Methods.

5. Conclusions

This paper has addressed the problem of predefined-time trajectory tracking for mechanical systems subject to both model uncertainties and full-state constraints. A novel adaptive neural network control scheme has been developed and rigorously analyzed. The core of the proposed design lies in the synergistic integration of predefined-time stability theory with a nonlinear mapping framework, where the controller is systematically derived by designing the rate of change of the mapped variables. A radial basis function neural network (RBFNN) is employed to effectively approximate and compensate for unknown system dynamics online. The proposed controller guarantees that all system states strictly remain within their predefined constraints at all times, thereby ensuring operational safety. Comparative numerical simulations on a representative mechanical system have been conducted, validating the theoretical results. The findings unequivocally demonstrate the superiority of the proposed controller over conventional finite-time and adaptive NNs control schemes, highlighting its exceptional performance in terms of faster convergence, higher tracking accuracy, and strict constraint adherence. Additionally, the tracking error is proven to converge to a small neighborhood of zero within a user-defined predefined time, which serves as the upper bound for system convergence and is independent of initial conditions.

Despite these promising results, several directions warrant further investigation. While the current study assumes full-state feedback, extending the framework to output-feedback scenarios, where velocities are not directly measurable, would significantly enhance its practical applicability. Furthermore, experimental validation of the proposed controller on a physical testbed, such as a multi-degree-of-freedom robotic manipulator, represents a critical next step to assess its robustness in the presence of unmodeled dynamics, sensor noise, and communication delays.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and J.Z.; Methodology, X.Y. and C.S.C.; Software, J.Z. and Y.J.; Validation, N.L. and X.Y.; Formal analysis, N.L.; Investigation, J.Z. and C.S.C.; Resources, Y.J.; Data curation, X.Y.; Writing—original draft, X.Y.; Writing—review & editing, Y.J.; Visualization, J.Z. and C.S.C.; Supervision, C.S.C.; Project administration, Y.J.; Funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62203247.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, D.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. Adaptive Neural Control with Guaranteed Performance for Mechanical Systems under Uncertain Initial Conditions: A Time-Varying Neuron Approach. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 6194–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Mei, J.; Zhang, X.; Lee, C.H.T. Simultaneous Identification of Multiple Mechanical Parameters in a Servo Drive System Using Only One Speed. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baspinar, C. Generalized Swing-Up Control of Underactuated Mechanical Systems. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2022, 6, 2144–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Nam, K.; Wei, C.; Yin, C. Trajectory Prediction of Preceding Target Vehicles Based on Lane Crossing and Final Points Generation Model Considering Driving Styles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 8720–8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, W.S.; Oetomo, D.; Manzie, C.; Choong, P. Control Barrier Functions for Mechanical Systems: Theory and Application to Robotic Grasping. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 29, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.H. Designing Robust Control for Mechanical Systems: Constraint Following and Multivariable Optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 5267–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Wu, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, H.; Shi, Y. Event-Based Adaptive Sliding-Mode Containment Control for Multiple Networked Mechanical Systems with Parameter Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Shi, P.; Lim, C.P. Fuzzy Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Stability Control Against Novel Actuator Faults and Its Application to Mechanical Systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 32, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.d.S.; Bessa, W.M. Sliding Mode Control with Gaussian Process Regression for Underactuated Mechanical Systems. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2022, 20, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Ding, Q.; Cheng, S.S. Global Coordinated Stabilization of Multiple Simple Mechanical Control Systems on a Class of Lie Groups. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fang, Y. Online Trajectory Planning Control for a Class of Underactuated Mechanical Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, M.; Respondek, W. Mechanical Feedback Linearization of Single-Input Mechanical Control Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2023, 68, 7966–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, N.; Fujimoto, K.; Maruta, I. Passivity-Based Sliding Mode Control for Mechanical Port-Hamiltonian Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 5605–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espindola, E.; Tang, Y. Geometric sliding mode control of mechanical systems on Lie groups. Automatica 2025, 177, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Yin, S.; Gao, H. Reconfigurable Tolerant Control of Uncertain Mechanical Systems with Actuator Faults: A Sliding Mode Observer-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 26, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttner, R. Extremum-Seeking Control for a Class of Mechanical Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2023, 68, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttner, R.; Krstić, M. Extremum seeking control for fully actuated mechanical systems on Lie groups in the absence of dissipation. Automatica 2023, 152, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jiang, J. Adaptive State-Feedback Shared Control for Constrained Uncertain Mechanical Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Sun, W. Adaptive Predefined-Time Bipartite Consensus Tracking Control of Constrained Nonlinear MASs: An Improved Nonlinear Mapping Function Method. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 6017–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Niu, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Duan, P.; Zong, G. Adaptive Neural Control of Nonlinear Nonstrict Feedback Systems with Full-State Constraints: A Novel Nonlinear Mapping Method. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wen, S.; Yan, Z.; Wen, G.; Huang, T. A Survey on the Control Lyapunov Function and Control Barrier Function for Nonlinear-Affine Control Systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Li, H. Stabilization of Delayed Boolean Control Networks with State Constraints: A Barrier Lyapunov Function Method. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2021, 68, 2553–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Converse Barrier Functions via Lyapunov Functions. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Chen, C.L.P.; Tong, S. A Novel Full Errors Fixed-Time Control for Constraint Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2023, 68, 2568–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xia, M.; Yi, Y. Adaptive neural dynamic surface control of strict-feedback nonlinear systems with full state constraints and unmodeled dynamics. Automatica 2017, 81, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pang, K.; Chen, J.; Li, K.; Hua, C. Adaptive Control for Nonlinear Systems with Both Tracking Error Constraints and Full-State Constraints: A Universal Constraint Approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, B. Practical Predefined-Time Fault-Tolerant Optimal Control for Heterogeneous Multiagent Systems Under Directed Graph. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J. Predefined-Time Safe Cooperative Control for Multiagent Systems with Privacy Preservation and Unknown Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2026, 56, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ji, W.; Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; Qiao, J. Predefined-Time Adaptive Neural Control for Nonlinear Systems with Unknown Interconnections. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 2608–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q. Neural network-based adaptive event-triggered control for cyber–physical systems under resource constraints and hybrid cyberattacks. Automatica 2023, 152, 110977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Shen, Q.; Shi, P. Neural-networked adaptive tracking control for switched nonlinear pure-feedback systems under arbitrary switching. Automatica 2015, 61, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, L.; Jin, J. A noise-tolerant fuzzy-type zeroing neural network for robust synchronization of chaotic systems. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e8218. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Gómez, G.I.; Zavala-Río, A.; López-Araujo, D.J.; Cruz-Zavala, E.; Nuño, E. Continuous Control for Fully Damped Mechanical Systems with Input Constraints: Finite-Time and Exponential Tracking. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, R.; Lu, Y.; Chen, W. Nonsingular pliable prescribed performance tracking control for hypersonic flight vehicles in the presence of uncertainties and input saturation. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 165, 106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ma, B. Finite-Time Command Filtered Tracking Control for Time-Varying Full State-Constrained Nonlinear Systems with Unknown Input Delay. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 4954–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, S.; Zhou, C.; Gao, Y.; Zong, Q. Distributed Practical Finite-Time Formation Control of Quadrotor UAVs Based on Finite-Time Event-Triggered Disturbance Observer. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tong, S.; Yang, H.; Hu, Q. Time-Synchronized Control for Spacecraft Reorientation with Time-Varying Constraints. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025, 30, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z. Fixed-Time Control and Estimation of Discontinuous Fuzzy Neural Networks: Novel Lyapunov Method of Fixed-Time Stability. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 16616–16629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyakov, A. Nonlinear Feedback Design for Fixed-Time Stabilization of Linear Control Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 2106–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Jiang, Y.; Jing, L.; Liu, P. Quantized predefined-time control for heavy-lift launch vehicles under actuator faults and rate gyro malfunctions. ISA Trans. 2023, 138, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Shi, L.; Sun, W.; Jahanshahi, H. Predefined-Time Average Consensus Control for Heterogeneous Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 2989–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Liu, X.; Shao, S.; Cao, J. Predefined-Time Bipartite Consensus of Networked Euler-Lagrange Systems via Sliding-Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 4989–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Chen, C.L.P.; Tong, S. Command Filter-Based Predefined Time Adaptive Control for Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 7863–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, B.; Zhao, X.; Duan, P.; Wang, H.; Gao, B. Global Predefined-Time Adaptive Neural Network Control for Disturbed Pure-Feedback Nonlinear Systems with Zero Tracking Error. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 6328–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, B.; Lin, C. Neural Adaptive Fixed-Time Control for Nonlinear Systems with Full-State Constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 3048–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, S.-C.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Huang, K. A New Lyapunov Based Robust Control for Uncertain Mechanical Systems. Acta Autom. Sin. 2014, 40, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Neural networks adaptive predefined-time control for pure-feedback nonlinear systems: A case study on robotic exoskeleton systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Ge, S.; Wang, J.; Guan, X. Time Delay Estimation-based Adaptive Sliding-Mode Control for Nonholonomic Mobile Robots. Int. J. Appl. Math. Control Eng. 2018, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.