Abstract

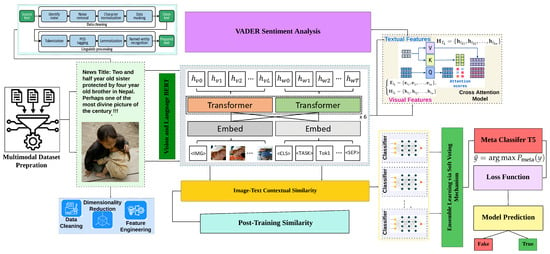

Detecting fake news is essential in natural language processing to verify news authenticity and prevent misinformation-driven social, political, and economic disruptions targeting specific groups. A major challenge in multimodal fake news detection is effectively integrating textual and visual modalities, as semantic gaps and contextual variations between images and text complicate alignment, interpretation, and the detection of subtle or blatant inconsistencies. To enhance accuracy in fake news detection, this article introduces an ensemble-based framework that integrates textual and visual data using ViLBERT’s two-stream architecture, incorporates VADER sentiment analysis to detect emotional language, and uses Image–Text Contextual Similarity to identify mismatches between visual and textual elements. These features are processed through the Bi-GRU classifier, Transformer-XL, DistilBERT, and XLNet, combined via a stacked ensemble method with soft voting, culminating in a T5 metaclassifier that predicts the outcome for robustness. Results on the Fakeddit and Weibo benchmarking datasets show that our method outperforms state-of-the-art models, achieving up to 96% and 94% accuracy in fake news detection, respectively. This study highlights the necessity for advanced multimodal fake news detection systems to address the increasing complexity of misinformation and offers a promising solution.

MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

The dissemination of misinformation through fake news to mislead or deceive the public has historical roots and is increasingly exploited in modern times via internet-based channels. Fake news has been extensively used in various contexts and types of content, including satire, conspiracy, news manipulation, and clickbait [1]. Consequently, this term has become increasingly prevalent and is strongly associated with events that pose significant social concerns, such as misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines, which likely led to more illness and deaths by discouraging vaccinations [2], and its potential influence on public opinion during the 2016 US presidential election [3].

Using social media for news updates has both advantages and disadvantages, as it allows for the free expression of personal views but also facilitates the spreading of false news [4]. Modern devices have amplified the use of social media and enabled users to create and share information, posts, and news more quickly. The wide adoption of the internet has impacted information quality [5] and enabled false claims to spread about technical and complex subjects that are usually harder to verify [6]. Fake news is often perceived as credible and spreads rapidly on social media, making disinformation a major concern. Thus, creating an automated system for effective fake news detection is crucial.

Multimodal fake news detection, which adopts various data types or modalities like text and images, integrates information from these diverse sources to provide a more comprehensive understanding and improve the accuracy of identifying and classifying fake news [7,8]. Detecting false content with such systems is difficult due to the complex relationship between language patterns and the underlying data. Language is deeply contextual, with meaning often depending on subtle nuances, such as tone, syntax, and cultural references. When combined with the massive scale of data—spanning various platforms, formats, and contexts—this complexity makes it hard for detection systems to distinguish between true and false information accurately [4]. Researchers have proposed solutions based on deep neural networks, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [9], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [10], and linguistic features such as sentiment analysis. This method uses vector embeddings, including stylometric and domain name analysis, and news source history [11] to differentiate real from fake news through text and visuals [12]. Most sentiment analysis models generate context-free or static embeddings and do not consider the varying meanings of words that may have different contexts. Thus, we focus on ensemble approaches that blend linguistic and deep learning models, effectively addressing these challenges [13].

Figure 1 illustrates multimodal data manipulation of visual and textual information. The first row compares real news with an image of Robert Joel Halderman during his trial for extortion against David Letterman, against fake news showing Barack Obama falsely accused of illegal activities. The second row features an image of Bill Gates and factual reporting on his 2018 discussion about population control through health initiatives. The fake news distorts this into a conspiracy theory, falsely suggesting that Gates is using deceptive tactics to reduce the population, further exaggerating this narrative by adding an ’Illuminati’ symbol. These examples underscore how real images and text can be manipulated to spread disinformation, lending false credibility to misrepresented stories.

Figure 1.

Examples of multimodal data manipulation contrasting real and fake news to mislead the audience [14].

Developing a model that cohesively, efficiently, and scalably combines the strengths of natural language processing and image analysis technologies is primarily challenged by the contextual variations between images and text, which complicate the alignment and interpretation of multimodal content [15], and by the complexity and substantial computational resources required for feature extraction from text and images [16]. Furthermore, semantic gaps between textual and visual content often complicate detection, especially when information that is true at one point becomes false later, or vice versa. For example, health recommendations or policies may change as new information becomes available. Models need to account for this temporal sensitivity. Another significant issue in multimodal fake news detection is the struggle of previous models to align visual elements, such as images, with textual claims due to subtle or blatant inconsistencies between these modalities.

In this light, there is a need for an advanced detection model that can effectively analyse and integrate multiple data types to identify fake news. Such a model must not only process textual and visual content with high accuracy but also adapt to the evolving tactics used in misinformation. This study aims to address these issues. The rest of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the state of the art in fake news detection. Section 3 motivates our approach and outlines its unique contribution to the field. Section 4 describes the dataset and methodology used in this study. Section 5 describes the proposed ensemble model. Section 6 provides a description of the experimental setup. Section 7 reports and comments on the results. Section 8 discusses the results and identifies the limits of the proposed model. Section 9 concludes this work.

2. Related Work

The transition from classical machine learning approaches to advanced deep learning (DL) techniques has marked an indicative evolution in the fight against fake news [17]. Initial efforts to detect fake news used conventional machine learning algorithms, including Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Naive Bayes, focussing on the extraction of features and the classification of textual content [18]. These algorithms generally emphasise generic textual features, analysing the text through linguistic dimensions such as lexicon, syntax, discourse, and semantics. In contrast, latent textual features generate embeddings from text data from news articles, at the word, sentence, or document level. These embeddings are transformed into latent vectors and then used as inputs for classification tools such as SVMs.

Despite the success of these techniques, they often fail to handle the complexity of modern news content, which can span multiple domains. To address this, advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and computational intelligence techniques have led to more sophisticated hybrid systems capable of dealing with this problem [19]. In [7], a heuristic algorithm for optimisation is used to tune the hyperparameters of the used NLP model for multi-label news classification, demonstrating superior performance to traditional CNNs and validated across four public news datasets. Furthermore, they proposed the HyproBert model in [20], which adds extra fake news detection capabilities by integrating CNN, DistilBERT, BiGRU, and CapsNet layers. Similarly, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), which can effectively capture temporal information [10], and CNNs are used together to extrapolate semantic and syntactic aspects of the text in [21]. Models such as BerConvoNet and CAME-BiLSTM showed significant improvements in multilabel classification but are difficult to tune [5,22].

Challenges emerge when addressing multimodal information, as existing models for multi-label classification have proven inadequate in simultaneously processing textual and visual data as required. Due to the proliferation of fake news in multimedia formats, such as images, audio, and video, there has recently been a growing demand for developing models for multimodal fake news detection. In [23], an interesting text- and image-based multimodal model is proposed as an alternative to sequence-independent classification. Further innovations include the use of the Attention-Residual Network for long-range data dependencies [24], the introduction of feature fusion systems based on multimodal factorised bilinear pooling [25], and additional event classification as a supplementary task [26]. The latter method has proven to improve generalisability by identifying event-invariant features in multiple media formats [27]. A different approach in [28] integrates text-based and image-based features using pre-trained models like BERT [29] for text and XLNet for images. It is worth mentioning the Feature Gradient Method with Feature Regularisation Adversarial Training (FGM-FRAT), which employs adversarial training to enhance the model’s robustness against unseen data [30].

The approach involving a visual and textual shared feature space, as detailed in [31], paves the way for an innovative similarity-based methodology within this domain. However, it currently encounters challenges in effectively capturing multimodal inconsistencies attributable to semantic gaps. Meanwhile, the Fake-News-Revealer (FNR) method introduced in [32] suggests using Vision Transformer and BERT to extract image and text features separately and then determining their similarities through loss functions. These methods show innovation and reflect the current efforts made by researchers to improve multimodal fake news detection by linking media features, but they struggle to capture complex cross-modal correlations.

Ensemble learning has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the detection of multimodal fake news by leveraging the strengths of multiple models and integrating diverse sources of information [28]. These methods combine predictions from multiple classifiers trained with different modalities (such as text, images, and videos), improving both accuracy and robustness [33]. The ensemble approach is grounded in key principles such as combining weak learners to create a stronger learner. This is based on the bias–variance tradeoff, where an ensemble reduces both bias and variance compared to individual models, leading to more accurate and robust predictions. A notable example is the SEMI-FND framework, which combines NasNet Mobile for image analysis with an ensemble of BERT and ELECTRA for text analysis, offering a minimal-parameter solution for fake news detection [34,35]. The model benefits from the ensemble principle of stacking, where multiple base models are trained separately, and their predictions are then combined through a meta-learner. The effectiveness of stacking lies in its ability to combine diverse model strengths, improving generalisability and predictive performance. Similarly, the Ensemble Learning-based Framework (ELD-FN) uses V-BERT to generate embeddings from both text and images, followed by a deep learning ensemble model for training and evaluation [13]. This framework integrates text and image features into a unified space, emphasising feature fusion, which enhances the model’s ability to detect fake news by combining complementary information from both modalities.

The A BERT-Based Multimodal Framework for Enhanced Fake News Detection Using Text and Image Data Fusion integrates text from images using Optical Character Recognition (OCR), demonstrating the potential of multimodal approaches to boost detection accuracy [36]. It employs the feature fusion principle, merging multiple data sources (text and image) into a shared space, which helps the model capture richer, more complementary information. In the context of improving machine learning models for lithofacies identification, How to Improve Machine Learning Models for Lithofacies Identification by Practical and Novel Ensemble Strategy and Principles introduces a strategy to make machine learning models more accessible for non-experts while improving performance [37]. The paper employs ensemble pruning, optimising the ensemble size by removing less useful models to improve computational efficiency without sacrificing performance.

The Truth Be Told: A Multimodal Ensemble Approach for Enhanced Fake News Detection uses a stacked ensemble model that integrates textual and visual data, improving efficiency in distinguishing fake news [38]. By applying a boosting strategy, the model focuses on correcting misclassifications in weak learners, which increases overall predictive accuracy. Finally, the EnsembleNet model combines GANBERT and BiLSTM for fake news detection, enhancing accuracy across multiple datasets [39]. This model follows the bagging principle, where multiple base models are trained on different subsets of the data and their predictions are aggregated. Bagging reduces variance and prevents overfitting, leading to more robust performance, particularly in noisy or imbalanced datasets.

These innovations reflect the theoretical grounding of ensemble learning principles such as stacking, boosting, bagging, and feature fusion, which contribute to the strength and robustness of multimodal fake news detection models. By combining predictions from multiple models, these techniques enhance accuracy, generalisability, and resilience, making ensemble learning a powerful tool in this domain. Detecting fake news on social platforms is made even more challenging by the vast amount of data and the time-sensitive nature of the task. The model [40], which processes image and textual features via a Quantum Convolutional Neural Network, and the ensemble approach combining pre-trained BERT with DL models (Bi-LSTM and/or Bi-GRU architectures on GloVe and FastText embeddings) for multi-aspect hate speech detection [41] are promising research directions to address these issues. Also worth mentioning are the Hierarchical Multi-modal Contextual Attention Network [42,43] and the Multi-modal Co-Attention Network [44], which extract spatial and frequency features from images and text, and the BERT-based multimodal models which encode and enhance interactions between text and images using ensemble learning [45,46].

In summary, recent studies highlight three key biases in multimodal fake news detection: image enhancement of text, text–image discrepancies signalling fake news, and improved detection through their integration. These findings underscore the value of combining text and visual cues for accuracy. Challenges include integrating NLP with image analysis, handling contextual variability, computational demands, and bridging semantic gaps. Table 1 summarises this review.

Table 1.

Advances on multimodal fake news detection.

3. Rationale and Contributions of the Proposed Approach

We propose an Ensemble Learning-based Multimodal Fake News Detection (EMFND) model that leverages stacked ensemble methods to improve fake news detection by integrating text and visual data. This approach combines multiple DL and transformer-based models, followed by soft voting, drawing on insights from our literature review to leverage the strengths of proven methods. EMFND uses sophisticated models like Bi-GRU [47], Transformer-XL [48], DistilBERT [49], and XLNet [50] to process features and ensure accurate predictions despite contextual variations between text and images. Designed for scalability, accuracy, and robustness across media formats, it reduces bias and overfitting. Parameter sharing is used to minimise training time, memory use, and model complexity.

We summarise the contributions of this study below.

- The proposed EMFND framework leverages ViLBERT’s two-stream architecture with cross-modality transformers [51] to process text and visual data simultaneously, capturing complex relationships and bridging the semantic gap for improved multimodal fake news detection.

- The model addresses the challenge of visual–text inconsistencies in multimodal fake news detection by using transformers to align cross-modal information and detect misinformation.

- We combine XLNet and Transformer-XL to capture long-term dependencies, improving the detection of evolving fake news with incremental modifications.

- We address the limitations of relying solely on text or image with our method, using Bi-GRU to process extracted features and manage sequential dependencies, and DistilBERT to capture bidirectional text context. Our stacked ensemble method with soft voting and a meta-classifier combines predictions from baseline models for the final result.

4. Materials and Methods

A graphical outline of the entire methodology is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research methodology work-flow chart.

Details on the dataset, problems, and preprocessing phases are reported in the remainder of this section.

4.1. Problem Formulation

The task of detecting fake news consists of analysing a dataset containing a set of m multimedia news posts, represented as . Each post () consists of a textual component , a corresponding set of images , and a label indicating whether the news is real () or fake (). Textual features transform text into a vector of characteristics in space . Image features map the images to a feature space . These features are integrated using a fusion function F, where represents the unified feature vector for the k-th post: . A classifier C uses this fused feature vector to assess the authenticity of the news post with a predicted label . The label classifies the post as real () or fake (): This prediction takes advantage of the combined strengths of text and image analysis to accurately determine the integrity of each news post in the dataset.

4.2. Datasets

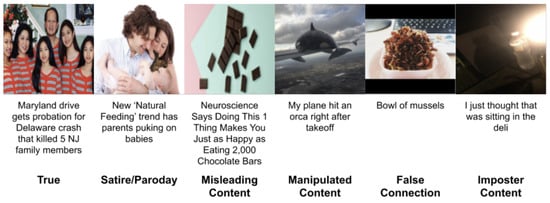

We conduct experiments on established benchmark datasets, namely Fakeddit and Weibo. Fakeddit [14] is an extensive multimodal fake news dataset featuring text and images (Figure 3). It comprises 1,063,106 samples across various fake news categories. The primary textual features include post titles, captions, or content, while the visual features comprise images associated with the posts.

Figure 3.

Fakeddit dataset overview [14].

The Weibo dataset [52,53] is a collection of 49,713 posts and 25,513 images from nine different domains, providing a comprehensive resource for detecting fake news. It includes rich data comprising texts, images, and social context information that are integral for multimodal analysis.

For both datasets, the focus in this study is on multimodal posts—those that contain both text and image—which are most commonly used in multimodal fake news detection research. In alignment with standard practices in multimodal fake news detection, the primary features exploited for model training are text (typically the cleaned post title or content) and visual content (the images). This approach ensures that the models are trained using the most informative and commonly utilised features in the field.

Statistics for these datasets are shown in Table 2. To perform experiments, we split them into three subsets: 70% of the data is randomly selected for training, 15% for testing, and 15% for validation.

Table 2.

Datasets summary.

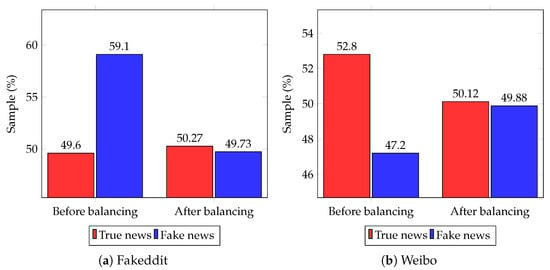

To tackle class imbalance, we use oversampling for Fakeddit and SMOTE [54] for Weibo datasets, plus Class Weight Adjustment [55] to reduce bias in model training. Figure 4 graphically displays the effect of these data balancing techniques.

Figure 4.

Balancing the datasets.

Note that both the Fakeddit (Figure 4a) and Weibo (Figure 4b) datasets are plagued by a significant class imbalance, introducing undesired biases into the models, but with opposite minority classes. In the case of Fakeddit, oversampling is applied to augment true news. This technique is preferred for this dataset over SMOTE because of its large size. Oversampling prevents overfitting, enhances minority class learning, and maintains multimodal data diversity without adding excessive noise. For Weibo, which has a smaller sample size, this approach was unfeasible due to the necessity of generating synthetic data, which motivates the use of SMOTE to increase samples in the fake news class.

Results are satisfactory, with nearly the same amount of samples in the two classes after the balancing process for both datasets. This guarantees a good degree of generalisation and a bias-free training phase.

4.3. Data Preprocessing

Every textual component of a news post undergoes tokenisation, which splits the text into n individual tokens for analysis, i.e., . Subsequently, all characters are normalised to lowercase, stop words and punctuation marks are removed, and words are lemmatised, i.e., . After normalisation, the text is vectorised to create numerical representations as . For the visual component , all images from each news post are uniformly resized to a format using bilinear interpolation and their pixel values are normalised via Min–Max.

5. The Proposed Model

Algorithm 1 describes our model. Each step is detailed in the remainder of this section.

| Algorithm 1: EMFND Pseudocode |

|

5.1. Vision and Language BERT (ViLBERT)

We use ViLBERT [56] to extract and combine text and visual features into a unified representation. This model extends BERT, having two streams that allow for text and image processing. It also employs cross-modal co-attention to learn inter-modal relationships between them.

5.1.1. Textual Stream

The input text is tokenised and fed to BERT’s encoder to generate contextual embeddings for each token . The latter passes through 12 BERT layers with multi-head self-attention (Equation (1)) to capture word relationships, followed by a feed-forward neural network, layer normalisation, and residual connections.

The output is a set of context-aware hidden representations of the text, as shown in Equation (2). These hidden states capture the deeper semantics of the text, such as sentiment, intent, and misleading cues, which are essential for detecting misinformation in news posts.

5.1.2. Sentiment Analysis

Valence Aware Dictionary for sEntiment Reasoning (VADER) [57], a lexicon- and rule-based sentiment analysis tool, computes sentiment scores (positive, negative, neutral, and compound) for the entire news article and captures emotional tone. It is selected for several key reasons: (1) it demonstrates strong performance in processing informal language, slang, emojis, punctuation-based emphasis, and negation—features that are prevalent in social media text and that contemporary transformer architectures may insufficiently weight without explicit guidance; (2) it is lightweight, interpretable, and requires no additional training, thereby ensuring computational efficiency and facilitating seamless integration into large-scale transformer-based pipelines; (3) in contrast to purely contextual embeddings derived from BERT-like models, VADER yields explicit sentiment polarity scores that directly capture emotional exaggeration and polarisation, both of which constitute strong signals for the presence of misinformation; and (4) prior studies [19,58] have demonstrated its effectiveness in fake news detection tasks, particularly when it is used in conjunction with deep learning–based feature representations.

The sentiment scores are concatenated with BERT’s embeddings to create an enriched representation as shown in Equations (3) and (4).

This enriched representation incorporates both contextual text features and sentiment scores, allowing the model to better capture the emotional manipulations that are common in fake news. This sentiment-enhanced text representation is then used in the cross-modal co-attention mechanism with visual features, improving the overall ability of the model to detect fake news.

5.1.3. Visual Stream

CNN models like ResNet are utilised on images for extracting region-based visual features . The embeddings are then passed through transformer layers to model relationships between different regions and result in a set of hidden representations for the image, as shown in the second case of Equation (5).

5.2. Cross-Modal Co-Attention

ViLBERT’s core innovation is its cross-modal co-attention mechanism, which enables interaction between textual and visual streams during processing, enhancing understanding of their relationship. Incorporating sentiment analysis from VADER further enriches this mechanism by offering emotional insights into the text. By combining sentiment scores with ViLBERT’s contextual embeddings, the model effectively detects emotionally charged content commonly present in misleading or fake news. Text and image representations are aligned through a generalised attention mechanism, which is formulated as , where indicates the direction of attention (text relating to the image or image relating to the text). For text relating to image (), , , and . For image relating to text (), , , and . The resulting co-attended hidden states for the text and image are formalised in Equation (6).

These updated hidden states, and , represent integrated information from text and image, allowing the model to capture inconsistencies between these modalities. For example, if an article describes a medical breakthrough, but the accompanying image is irrelevant or misleading, the co-attention mechanism can detect this discrepancy as .

5.3. Image–Text Contextual Similarity

Another component in assessing the alignment between visual and textual content is Image–Text Contextual Similarity. Due to the use of misaligned or irrelevant imagery to manipulate or deceive, this similarity measure becomes particularly useful for detecting fake news. Mathematically, this is simply computed as the cosine similarity between the final co-attended text and image embeddings, as formulated in Equation (7).

where and are the co-attended text and image embeddings, respectively. The cosine similarity score ranges from −1 to 1, where indicates perfect alignment between text and image, while indicates complete dissimilarity, and suggests no discernible relationship. This contextual similarity score helps the model detect contrasting narratives between the image and text, such as when the text in a news article is factual, but the image used is misleading or unrelated.

The notion of image–text similarity is extended by introducing three different types of similarities, namely textual similarity (), which represents the relationship between textual information extracted from both images and news content; semantic similarity (), which measures the semantic alignment between text and image; and contextual similarity (), which evaluates how well the image and text align within the broader context of the article. These similarities are calculated based on information extracted directly from the original image and text or related knowledge using BERT embeddings.

Post-Training Similarity

To improve fake news detection, a novel image–text similarity measure called post-training similarity () is introduced. After training ViLBERT, a state-of-the-art multimodal fake news detection classifier, the hidden representations of both text and image are extracted. The cosine similarity, denoted as , measures how these representations align after the model has learned to differentiate between fake and real news. Specifically, given a news article , image features are extracted using Faster R-CNN with ResNet-101 as the backbone, while text features are processed using ViLBERT’s linguistic tokens. The final image and text representations are captured by the vectors corresponding to the IMG and CLS tokens, respectively. The cosine similarity between these representations is defined through Equation (8).

This similarity captures the relationships between image and text as processed during model training, offering valuable insight into how image–text similarity evolves within the fake news detection model.

5.4. Unified Representation and Classification

The classicifaction output ( fake, real) is obtained by processing final co-attended embeddings and with a classifier {DistilBERT, Transformer-XL, XLNet}. We implement a stacked ensemble approach using the available classifiers to then make the final decision with a T5 meta-classifier with a soft voting mechanism to improve robustness. Formally, . The ensemble classifier prediction is modelled via Equation (9), where indicates whether the news post is classified as fake (0) or real (1).

The key advantages of this unified representation include effective bridging of semantic gaps through cross-modal co-attention, enabling precise detection of text–image inconsistencies common in fake news; enhanced robustness and accuracy by integrating diverse transformer strengths (e.g., bidirectional context from DistilBERT and long-range dependencies from XLNet); and improved generalisation across datasets, as unified embeddings capture complementary multimodal cues more comprehensively than single-modality approaches.

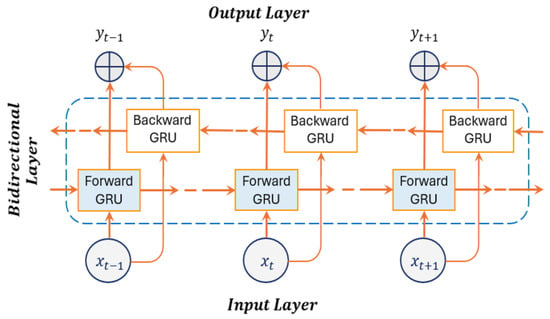

5.5. Bi-GRU Implementation

The Bi-GRU (Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit) network [47] is utlised to capture both forward and backward dependencies within a sequence of tokens. The architecture is shown in Figure 5, providing a high-level overview of the model’s structure and the flow of data through the layers. This makes it highly effective for understanding the full temporal context of a text. The textual embeddings generated from ViLBERT are passed into the Bi-GRU network. These embeddings represent the tokens in the sequence and provide local and global context from the news post, with n being the number of tokens and d the dimensionality of each embedding. Implemented in three bidirectional layers, the Bi-GRU model captures short-term dependencies in the first layer while the second and third layers refine these representations by capturing longer-term dependencies and integrating context from both directions. This means that two GRUs operate in opposite directions, i.e., one forward and one backward.

Figure 5.

High-level view of the Bi-GRU architecture.

The forward GRU processes the sequence from the first token to the last, while the backward GRU processes it in reverse, from the last token to the first. For each token , the forward GRU produces a hidden state , and the backward GRU produces a hidden state . The hidden state updates for each direction are defined with Equations (10) and (11).

At each time step i, the forward and backward hidden states are concatenated to form the final hidden state for that time step as , where and d is the size of the hidden state for each direction. To enhance the network’s focus on important tokens, an attention mechanism is applied on top of the Bi-GRU, assigning a weight to each hidden state to represent the importance of the corresponding token in the final prediction. The attention score for each token is computed through Equation (12),

where v and are learnable parameters, and represents the attention weight for token . The final context vector is then computed as a weighted sum of the hidden states (Equation (13)).

Once all hidden states have been generated, they are aggregated to form a summary of the entire sequence using the Final Time Step method. This means that hidden state of the final token is used as the representation for the entire sequence. By doing , we capture the refined context of the entire sequence, combining information from both directions.

The final hidden state is fed to a connected dense layer to generate the output probabilities as indicated in Equation (14),

Here, W is the weight matrix of the dense layer, b is the bias vector, and y represents the output class (0 for fake news, 1 for real news).

Then, a dense layer applies a linear transformation followed by a softmax activation function to produce the probability distribution over the class labels (real or fake news). This ensures that the output is a valid probability distribution over the classes, summing to 1 (Equation (15)).

With reference to Equation (15), denotes the probability of the news being real, while denotes the probability of it being fake. The final classification decision is made by selecting the class with the highest probability. This is easily done via Equation (16).

where represents the predicted class, with 0 indicating fake news and 1 indicating real news.

5.6. Transformer-XL

The Transformer-XL [48,59] is used to capture long-range dependencies in sequential data by introducing a segment-level recurrence mechanism. This allows the model to maintain a memory of past segments, which is especially useful for long-form text, such as news articles, where information might be distributed across multiple segments. The textual embeddings , generated from ViLBERT, are passed into Transformer-XL. The sequence of embeddings is split into segments, where each segment contains l tokens, and the entire sequence may span multiple segments. where n is the number of tokens in the sequence, and each segment has l tokens. Transformer-XL processes each segment, transferring the hidden state from prior segments to capture long-range dependencies. The hidden state for each token in the current segment is updated with Equation (17),

where is the hidden state from the previous segment.

A relative positional encoder is used to capture the relative distances between tokens and , and their attention score is computed. Once all segments have been processed, the hidden state of the last token in the sequence is taken as the final representation of the entire sequence as . The final hidden state is passed through a dense layer followed by a softmax function to produce the output probabilities for the class labels. This is done through Equation (18),

where W and b are learnable parameters. The final class is determined by selecting the label with the highest probability with .

5.7. DistilBERT

DistilBERT [49,60] is a smaller and faster variant of BERT, retaining 97% of BERT’s performance. It uses 6 transformer layers instead of 12, making it ideal for real-time predictions. Textual embeddings , generated from ViLBERT, are passed into DistilBERT and processed through its transformer layers, where a multi-head self-attention mechanism is applied, allowing each token to attend to every other token in the sequence. After the attention score computation, the representation of each token is passed through a feed-forward network to refine its embedding. The hidden state of the [CLS] token, , is taken as the representation for the entire sequence as . The final hidden state is passed through a dense layer followed by a softmax function to generate the class probabilities as . The final class is determined by selecting the label with the highest probability using Equation (19):

5.8. XLNet

XLNet [50,61] is a permutation-based transformer model that improves on BERT by allowing the model to capture bidirectional context without masking. It does this by training on all possible permutations of the input sequence. The textual embeddings , generated from ViLBERT, are passed into XLNet. Instead of applying self-attention to the original sequence, XLNet processes multiple permutations of the sequence and allows it to capture relationships in all possible orderings. The attention mechanism is applied, and each token’s embedding is passed through a feed-forward network. The hidden state of the final token is used as the representation of the entire sequence as . The final hidden state is passed through a dense layer and softmax function to compute the output probabilities as . The final class is selected by taking the label with the highest probability using Equation (20):

5.9. Ensemble Approach

In this approach, four base classifiers—Bi-GRU, Transformer-XL, DistilBERT, and XLNet—are combined using soft voting and a stacking ensemble method, with the T5 meta-classifier making the final prediction. This ensemble method maximises the strengths of each model, improving the overall accuracy and robustness of fake news detection. Each base classifier , where {Bi-GRU, Transformer-XL, DistilBERT, XLNet}, outputs a probability distribution over the class labels , with representing fake news and representing real news. The output probabilities for each classifier can be represented as

These vectors represent the probabilities that each classifier assigns to the news post being either fake or real. The outputs from these classifiers provide valuable insights into the classification task by focusing on different aspects of the input data, such as short-term dependencies with Bi-GRU, long-range dependencies with Transformer-XL, and contextual representations with DistilBERT and XLNet.

5.10. Soft Voting Mechanism

After obtaining the probability distributions from each base classifier, a soft voting mechanism is applied to aggregate their outputs. The combined probability distribution for class y is calculated by averaging the individual outputs of the four classifiers via Equation (22), where represents the averaged probability for class y (fake or real).

Soft voting averages predicted class probabilities rather than using hard majority votes, thereby utilising richer confidence information from each base classifier. This approach offers several key advantages: (1) it balances the complementary strengths of diverse models (e.g., Bi-GRU’s sequential processing, XLNet’s permutation-based dependencies), reducing individual biases and variance; (2) it mitigates the impact of over-confident but erroneous predictions from any single classifier; and (3) it consistently yields higher accuracy and robustness in ensemble settings, particularly on noisy multimodal data such as social media fake news, as supported by recent ensemble-based detection studies.

The resulting is then concatenated with individual base probabilities and fed to the T5 meta-classifier for the ultimate decision.

5.11. Meta-Classifier T5

Alongside soft voting, we employ a stacking ensemble approach with a T5 meta-classifier, where the T5 model [62] is trained to combine the outputs of the base classifiers and make the final prediction by learning how these outputs relate to each other. The concatenated probability outputs of all base classifiers form the input to the T5 model as indicated in Equation (23).

This 8-dimensional vector contains the probability scores for both class labels from each of the four base classifiers. Because of its transformer-based architecture, the T5 model processes the concatenated vector to learn and optimise the final prediction based on the relationships between the outputs of the base classifiers. Formally, the T5 meta-classifier generates the final probability distribution over the class labels. To make the final classification decision , the class with the highest probability from the T5 meta-classifier’s output is selected (Equation (24)). The final prediction , 0 (fake) or 1 (real), is the optimal decision from the ensemble of classifiers.

5.12. Loss Function

The overall loss function used for training the ensemble model minimises the classification error between the true labels and the predicted labels generated from the ensemble’s output. The total loss accounts for both text and image modalities. For each news post , the total loss is calculated as Equation (25).

where and are weighting factors that balance the contributions of the text and image modalities. and represent the cross-entropy loss for the text and image components, respectively. The cross-entropy loss for each modality is defined as Equation (26).

where C is the number of classes (e.g., fake or real news), and and represent the true and predicted probabilities for each class. To further balance the contributions of the text and image features, we introduce a trade-off parameter , where . The final loss function for training the stacked ensemble with the T5 meta-classifier is optimised by minimising the weighted sum of the losses from the text and image predictions. The updated loss function is shown in Equation (27).

Here, controls the contribution of the text-based predictions , and controls the contribution of the image-based predictions . C represents the number of classes, and is the true label. This final ensemble loss ensures both text and image features contribute effectively to improving fake news detection accuracy during training.

6. Experimental Phase

The ensemble learning methodology for detecting fake news, using a soft voting strategy combined with a T5 meta-classifier, is outlined in Algorithm 1, with detailed steps explained in the following subsections. The approach begins by extracting both textual and visual features from a news post using ViLBERT. Four classifiers—Bi-GRU, Transformer-XL, DistilBERT, and XLNet—are then used to process the input independently, each producing a probability distribution for the news being fake or real. These distributions are averaged through soft voting to produce a final probability. The outputs of all classifiers are concatenated and fed into a T5 meta-classifier, which refines the prediction by generating a final probability distribution. The class with the highest probability is selected as the predicted label, providing a robust approach to fake news detection by combining the strengths of multiple classifiers with a meta-classifier.

6.1. Hyperparameter Tuning

The hyperparameters of the EMFND model are optimised through a combination of grid search and manual tuning. It is important to note that the concept of memory length applies only to models like Transformer-XL, which utilise segment-level recurrence to manage long-range dependencies. In contrast, models such as Bi-GRU, DistilBERT, and XLNet do not require a memory length parameter, as they rely on mechanisms such as gated units and bidirectional attention to handle sequential information.

Both Bi-GRU and DistilBERT implement dropout rates to prevent overfitting during training. Transformer-XL omits standard dropout to better capture long-term dependencies. Meanwhile, XLNet employs a dropout rate of 0.1 for effective regularisation. All models are trained for 40 epochs, which is sufficient to achieve convergence without overfitting, thus balancing performance with training time. The AdamW optimiser is selected for all models because it effectively decouples weight decay from gradient optimisation, improving generalisation and reducing overfitting.

The hyperparameters listed in Table 3 are designed to optimise the ensemble’s performance by striking a balance between complexity, efficiency, and generalisation.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters for the classifiers used in the EMFND Model.

6.2. Evaluation Metrics

Established metrics are used to assess the performance of the EMFND mode, such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC. For details, see [63].

7. Results and Analysis

We report confusion matrices for the classification results and compare the models in the ensemble. The performance of EMFND for each dataset is summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Performance of the EMFND framework on Fakeddit and Weibo datasets.

The model achieved an accuracy of 96% for detecting fake news and 97% for true news on the Fakeddit dataset. Precision values are 96% for fake news on Fakeddit and 93% on Weibo. These values demonstrate the model’s strength in identifying fake news. Recall scores are 95% for fake news and 96% for true news on Fakeddit. On Weibo, recall is 94% for both fake news and true news. F1-scores are 97% for fake news and 95% for true news on Fakeddit, and 95% for fake news and 94% for true news on Weibo. These metrics highlight the model’s ability to balance precision and recall. AUC-ROC values of 0.94 on Fakeddit and 0.91 on Weibo demonstrate the model’s discriminative power in distinguishing between fake and true news. These results confirm the model’s effectiveness across both datasets.

7.1. Performance Analysis

The model performs slightly better on the Fakeddit dataset due to its larger size and more diverse set of examples compared to Weibo. The F1-score and AUC-ROC metrics further confirm the reliability of the model in detecting fake news and distinguishing it from real news.

Table 5 presents the classifier-wise performance of the proposed ensemble framework on the Fakeddit and Weibo datasets. The results clearly show how each classifier performs in detecting fake and real news, highlighting the strengths and limitations of individual models compared to the ensemble approach.

Table 5.

Classifier-wise performance on Fakeddit and Weibo datasets (%).

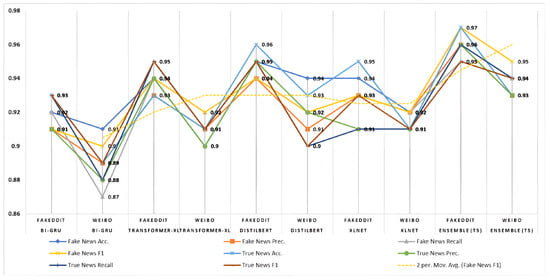

Bi-GRU performs reasonably well but falls short compared to the other models, especially on the Weibo dataset, where it exhibits lower accuracy and precision due to its focus on short-term patterns. In contrast, Transformer-XL captures long-range dependencies, thereby achieving up to 94% accuracy for fake news on Fakeddit and clearly outperforming Bi-GRU. DistilBERT achieves 96% accuracy for true news on Fakeddit, making it a reliable choice across both datasets. XLNet also performs well, maintaining precision and recall above 92% on both datasets. Note that EMFND (i.e., the output of the T5 meta-classifier) significantly outperforms the individual models, especially on Fakeddit, with 97% accuracy for true news and 96% for fake news, as shown in Figure 6. This demonstrates that better overall performance is obtained by integrating the strengths of all models.

Figure 6.

Classifier-wise model performance analysis.

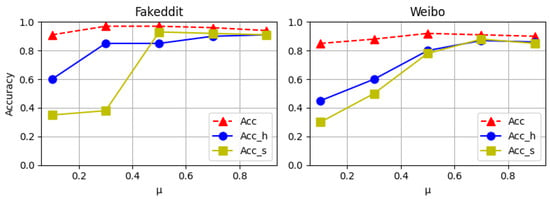

To improve our model, we incorporate logical constraints to guide the learning process of the latent variables z. By varying the trade-off parameter in the loss function, we investigate how different levels of logical supervision impact the quality of z and the overall performance of the model.

As shown in Figure 7, low (0.1) results in low hard and soft logic accuracies ( and ), indicating poor detection of deceptive patterns. Increasing improves performance, reaching a peak at , after which performance stabilises or slightly declines, suggesting the need for balanced logical supervision. Notably, overall accuracy remains stable across different values, demonstrating the robustness of our approach.

Figure 7.

EMFND evaluation at varying loss function weights.

7.2. Impact of Sentiment Analysis

The sentiment scores are classified into two categories: real and fake. Table 6 presents the aggregated emotion scores, highlighting the differences in performance when sentiment analysis is enabled or disabled in the textual features for fake news detection.

Table 6.

Influence of sentiment analysis on Fakeddit and Weibo Datasets (%).

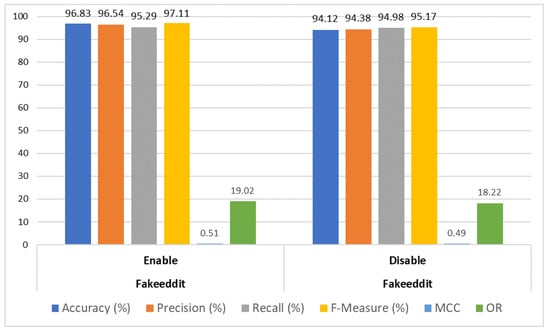

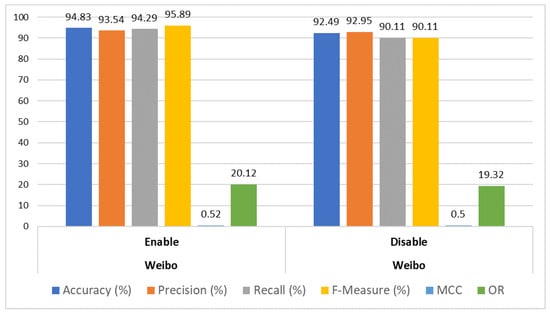

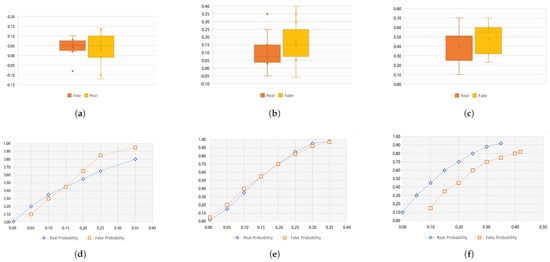

In the Fakeddit dataset, the model achieves higher accuracy (96.83% instead of 94.12%) and a higher F1-score (97.11% instead of 95.17%) when sentiment analysis is enabled, as visualised in Figure 8. Similarly, for Weibo, it achieved an accuracy of 94.83% instead of 92.49% and an F1-score of 95.89% instead of 90.11%, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Impact of sentiment analysis on EMFND evaluation with Fakeddit dataset.

Figure 9.

Impact of sentiment analysis on EMFND evaluation with Weibo dataset.

True news typically has neutral sentiment, while false news uses extreme sentiment to evoke extreme emotions. Enabling sentiment analysis helps the model distinguish between true and false news by detecting these emotional cues, improving accuracy and F1-scores, especially in political or sensitive topics.

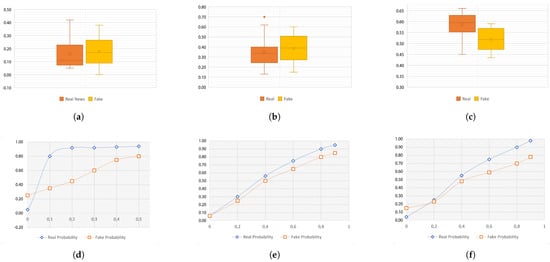

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show that semantic similarity () is consistently higher than textual similarity () across real and fake news in both the Fakeddit and Weibo datasets. This can be attributed to BERT, whose embeddings capture richer contextual information and lead to a higher semantic alignment between text and image. Interestingly, both and tend to be higher for fake news compared to real news. This is likely because fake news often uses emotionally or semantically aligned language and imagery to mislead readers. In the Fakeddit dataset, e.g., many fake news items show high semantic similarity scores in the range . This reflects the model’s sensitivity to semantic manipulation in fake news. No clear pattern for post-training similarity () is observed across datasets, which could suggest that the learnt representations of fake and real news vary depending on how the modalities interact during training. However, the cumulative distribution functions (Figure 10 and Figure 11) confirm that image–text similarity tends to be higher for fake news across most cases.

Figure 10.

Statistical evaluation of the Fakeddit dataset shows significant differences between real and fake news in terms of (a) textual, (b) semantic, and (c) post similarities, (d–f) both real and fake news probability ratio with Mann–Whitney test (p-values are 3.62 × 10−7, 1.69 × 10−9, and 2.61 × 10−8), respectively.

Figure 11.

Statistical evaluation of the Weibo dataset shows significant differences between real and fake news based on (a) textual, (b) semantic, and (c) post similarities, (d–f) both real and fake news probability ratio with Mann–Whitney test (p-values of 1.70 × 10−10, 1.57 × 10−9, and 1.81 × 10−11), respectively.

The evolution of image–text similarity from pre-training (using and ) to post-training () further demonstrates the model’s ability to distinguish between real and fake news more effectively after training. Initially, real and fake news have similar scores, but after training, fake news shows greater divergence, especially in Fakeddit, where higher image–text similarity improves detection performance.

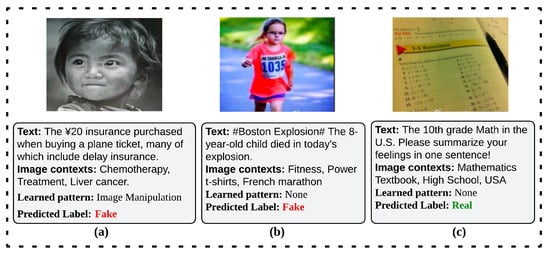

Figure 12a–c illustrates several fake news examples from the Fakeddit and Weibo datasets. It highlights retrieved image contexts, deceptive patterns, and predicted authenticity labels. In Figure 12a, the text mentions a CNY 20 insurance purchase alongside references to chemotherapy and liver cancer. The model retrieves image contexts related to chemotherapy and treatment, identifies ‘Image Manipulation’, and predicts the label as fake due to inconsistencies between the text and image. In Figure 12b, the text describes the Boston Explosion involving an 8-year-old child, while the retrieved images relate to fitness, power t-shirts, and a marathon. The model predicts Fake, detecting inconsistency between the tragic event and the unrelated image contexts. In Figure 12c, the text discusses a 10th-grade math exercise in a U.S. textbook, with retrieved images aligning with a mathematics textbook and high school context. The model predicts Real, as the image and text are consistent and authentic.

Figure 12.

Fake (a,b) and Real (c) news examples from Fakeddit and Weibo dataset with EMFND prediction.

7.3. Ablation Study

Ablation studies are vital for assessing component contributions in complex models and revealing the most crucial features influencing model performance. We do this on both the Fakeddit and Weibo datasets and report results in Table 7. Fake News Detection Without Social Context () is performed where the social context feature is removed. The model relies solely on knowledge extraction from text and image data for fake news detection. Fake News Detection Without Image () is excluded in this variant. The binary classifier processes knowledge derived from the combination of shared text and social context features across all classifiers, without the inclusion of image data. Fake News Detection Without Image and Social Context () is performed as image and social context features are removed in this model. The model relies only on the knowledge extracted from the text as input for training. Fake News Detection Without Knowledge Extraction () is executed without the knowledge extraction (KE) component. The other components operate without additional external knowledge integration. Fake News Detection Without Social Context + Knowledge Extraction () removes the knowledge extraction and social context features. It leaves only image and text data as input for the model’s training. In Fake News Detection Without Image + Knowledge Extraction (), the model is trained without the image feature and the knowledge extraction module, utilising only text and social context data. Fake News Detection Without Image, Social Context, and Knowledge Extraction () is the final variation. The model is trained without image, social context, or knowledge extraction. It only uses the text data for training, and the averaged outputs are passed into a binary classifier for fake news detection.

Table 7.

Ablation study performance analysis for Fakeddit and Weibo datasets.

Removing individual components like social context () or images () causes a noticeable performance drop. The absence of both social context and images () results in an even greater decrease in accuracy, precision, and recall. It highlights their importance in multimodal fake news detection. The sharp decline in models like shows that combining textual, visual, and contextual features is essential for effective fake news detection. This reinforces the conclusion that the ensemble model, by using all features, provides the most accurate performance on both datasets.

Removing individual components such as social context () or images () causes a performance drop. This is expected, as both social context and image features provide supplementary information that is essential for accurate fake news detection. Social context provides metadata or external cues that help in interpreting the news content, such as user engagement or trends, which are not always captured by text or images alone. Likewise, image data plays a vital role in identifying manipulative or misleading visuals that often accompany fake news. The absence of both social context and image features () results in an even greater decrease in accuracy, precision, and recall. This highlights the importance of both visual and contextual features in multimodal fake news detection. The sharp decline in performance when removing social context, image, and knowledge extraction () demonstrates that combining textual, visual, and contextual features is essential for effective fake news detection. Without these multiple sources of information, the model is unable to capture the full context and nuances, leading to a significant performance drop.

This ablation study reinforces the conclusion that the EMFND model, which uses all features (text, image, social context, and knowledge extraction), provides the most accurate performance across both datasets. It confirms that multimodal learning, which combines different sources of information, is the key to achieving the best results in fake news detection.

7.4. Baseline Models

The baseline models selected for comparison are carefully chosen to cover a range of approaches, from simple traditional machine learning techniques to advanced deep learning architectures. Each baseline model offers insights into how different methods handle multimodal fake news detection by focusing on text, images, or both. These choices provide a well-rounded comparison and are consistent with the multimodal ensemble approach used in the EMFND model. To ensure a fair comparison, hyperparameter tuning was conducted for all baseline models, following the same methodology as for the EMFND model. Grid search was used to optimise key hyperparameters for each model, such as learning rate, batch size, dropout rate, and number of layers. This optimisation process ensured that each baseline model was trained under optimal conditions for a fair evaluation of performance. Hyperparameters were selected based on performance in a validation set, and we ensured that the models were trained for a sufficient number of epochs to achieve convergence without overfitting.

- BERT + ResNet (Late Fusion) [64] combines BERT for text analysis and ResNet [65] for image analysis. Text and image data are processed separately and then fused at a later stage for final classification.

- VGG-16 + LSTM [66] uses VGG-16 for image feature extraction and LSTM for text analysis. The extracted features are concatenated and passed through a fully connected layer for classification.

- CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining) [67] is a multimodal model by OpenAI that processes text and images by projecting them into a shared latent space, trained via contrastive learning to match images with their text descriptions.

- Logistic Regression (LR) + Handcrafted Features (HF) [68] serves as a baseline, using TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) for text and colour histograms and pixel-based features for images.

- Random Forest [69] is an ensemble algorithm that builds multiple decision trees and averages their predictions. In this baseline, text features from BERT embeddings and image features from ResNet are concatenated and classified using Random Forest.

The comparative analysis using the selected baseline models provides a comprehensive understanding of how different techniques handle multimodal fake news detection on Fakeddit and Weibo datasets (Table 8: Each baseline model contributes differently in terms of evaluation metrics.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis with baseline models on Weibo and Fakeddit datasets (%).

The comparative analysis shows that advanced deep learning models like BERT + ResNet (Late Fusion) and CLIP outperform traditional machine learning methods such as Logistic Regression and Random Forest across both datasets. BERT + ResNet achieves an accuracy of 0.89 for fake news and 0.90 for true news on Fakeddit, while on Weibo, it reaches 0.90 and 0.91, respectively. CLIP demonstrates even higher performance, achieving 0.93 accuracy for fake news and 0.92 for true news on Fakeddit, and 0.91 for both on Weibo, due to its contrastive learning technique that aligns text and image features effectively. VGG-16 + LSTM, with 0.85 accuracy for fake news and 0.84 for true news on Fakeddit, performs moderately well but struggles with more complex data relationships compared to deeper models. Logistic Regression with Handcrafted Features and Random Forest show the limitations of traditional techniques, with Logistic Regression reaching only 0.75 accuracy for fake news and 0.74 for true news on Fakeddit, while Random Forest fares slightly better with 0.82 for fake news and 0.83 for true news. Ultimately, our proposed EMFND model outperforms all baselines, achieving the highest accuracy and F1-scores across both Fakeddit and Weibo, confirming the effectiveness of our multimodal ensemble approach in fake news detection.

7.5. Comparitive Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, it is compared against other state-of-the-art multimodal fake news detection models using the same dataset in Table 9 and Table 10. The key models used for comparison are as follows:

- CLIP [70] introduced a multimodal framework for fake news detection by integrating text and visual data. It employs NLP for text preprocessing, the DeepL translator for language consistency, and LSTM networks for analysing text sequences. For image analysis, it uses the CLIP model, and the combined features are classified as real or fake in the decision-making layer.

- FakeNED [13] presented an ensemble learning-based method for detecting multimodal fake news. It utilised Visual BERT (V-BERT) to generate embeddings for text and Faster-RCNN for images. These embeddings are input into a deep-learning ensemble model for training and testing.

- Ref. [32] extracted textual and visual features to improve detection accuracy. Textual features are obtained using pre-trained BERT, GRU, and CNN models, while image features are extracted with ResNet-CBAM. These features are fused, and dimensionality is reduced by using an auto-encoder. The features are classified using an FLN classifier to detect fake news.

- CLIP-GCN [71] proposed a Clip-GCN multimodal fake news detection model that uses the Clip pre-training model for joint semantic feature extraction from image–text data. The model employed adversarial training to extract inter-domain invariant features and graph convolutional networks (GCNs) to utilise intra-domain knowledge.

- FND-Clip [27] detects fake news by using CLIP to extract and combine deep text and image features. It weights these features based on similarity and uses a modality-wise attention module to improve feature aggregation for accurate detection.

- Event-Radar [72] performed event-level multimodal analysis and credibility-based multi-view fusion for detecting fake news effectively.

- MACCN [73] improved fake news detection by fusing textual and visual features through distinct encoders and an Adaptive Co-attention Fusion Network. It strengthened correlations between the modalities for better representation.

- NSLM [74] Neuro-Symbolic Latent Model detected news accuracy and deceptive patterns using two-valued latent variables learned through variational inference and symbolic logic rules.

- TMGWO [75] uses the TMGWO genetic algorithm to extract optimal features from text, metadata, and author embedding data. Fusion methods combine these multimodal features, and a two-layer MLP is used for fake news detection.

- Multimodal CNN [76] performed a fine-grained classification of fake news using unimodal and multimodal approaches. The best results were achieved using a multimodal approach based on a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) that combines text and image data.

- HiPo [77] is a multimodal method that combines features from graphical and textual content. It assesses the truthfulness of a social media post by constructing its historical context from previous similar, off-label posts, enabling online detection without the need for a context or knowledge database.

- SDSA [78] refers to the Semantic Distillation and Structural Alignment (SDSA) network. It includes a semantic distillation module that retains task-relevant information and removes redundancies from modality-specific features. A triple similarity alignment module is proposed to maintain structural information by aligning intra-modal, inter-modal, and fused feature similarities.

- Fakefind [79] is a hybrid model that combines CNN and RNN to integrate multimodal features for efficient rumour detection. It uses a CNN-based knowledge extractor to extract stance from post–reply pairs and incorporates stance representations for fake news detection.

Table 9.

A comparative analysis of the proposed EMFND model with existing studies on the fakeddit dataset.

Table 9.

A comparative analysis of the proposed EMFND model with existing studies on the fakeddit dataset.

| Reference | Model | Fake News | Real News | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | Prec. | Recall | Accuracy | F1 | Prec. | Recall | ||

| [76] | CNN | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| [74] | HiPo | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.85 |

| [79] | Fakefind | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| [70] | LSTM CLIP | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| [13] | V-BERT CNN LSTM | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| [73] | MACCN | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| [74] | NSLM | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.93 |

| [75] | TMGWO | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| [78] | SDSA | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| Proposed | EMFND | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

Table 10.

Comparison of models by accuracy, F1, precision, and recall on Weibo dataset.

Table 10.

Comparison of models by accuracy, F1, precision, and recall on Weibo dataset.

| Reference | Model | Fake News | Real News | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | Prec. | Recall | Accuracy | F1 | Prec. | Recall | ||

| [27] | FND-CLIP | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| [74] | HiPo | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| [79] | Fakefind | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| [32] | LSTM CLIP | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| [71] | CLIP GCN | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| [72] | Event-Radar | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| [73] | MACCN | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.90 |

| [74] | NSLM | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| [78] | SDSA | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Proposed | EMFND | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.94 |

The comparative analysis for the Fakeddit dataset shows that the proposed EMFND model outperforms all others in both fake and real news detection. With 0.96 accuracy for fake news and 0.97 for real news, and F1-scores of 0.97 and 0.95, it demonstrates superior performance by leveraging multimodal features. SDSA and LSTM-CLIP perform well, but their results are close but not as consistent. EMFND’s combination of text, image, and social context offers a clear advantage. HiPo, MACCN, and NSLM also perform respectably, but their F1-scores are lower. This reinforces the effectiveness of the ensemble approach in EMFND. It confirms the importance of multimodal feature integration and ensemble learning for accurate fake news detection.

For the Weibo dataset, The EMFND model shows the best performance, with 0.94 accuracy and an F1-score of 0.95 for fake news, and 0.93 accuracy and 0.94 F1 for real news. This highlights the efficiency of the model, especially in text-heavy datasets. Although models like FND-CLIP, Event-Radar, and MACCN perform well, they fall short of EMFND’s consistency across all metrics. The strong results of SDSA, Event-Radar, and HiPo show that multimodal approaches work well for Weibo. However, integration of EMFND features into an ensemble framework proves to be the most effective for multimodal and text-centric data.

8. Discussion

The experimental results show that the proposed EMFND framework significantly outperforms individual baseline models and recent state-of-the-art multimodal approaches. This advantage mainly stems from its stacked ensemble strategy, which captures complementary textual and visual features and integrates them via soft voting and a T5 meta-classifier. The use of transformer-based models (DistilBERT, XLNet, Transformer-XL) provides strong contextual understanding of complex linguistic patterns, while ViLBERT’s two-stream cross-modality attention mechanism enables precise alignment between images and text. The inclusion of VADER sentiment analysis and Image–Text Contextual Similarity further enhances the model’s sensitivity to emotional manipulation and cross-modal inconsistencies—common hallmarks of sophisticated fake news.

One of the key observations is that the ensemble model performs better in cases where fake news exhibits multimodal inconsistencies, such as when the accompanying text and image do not align (e.g., a misleading headline paired with an unrelated image). For instance, in scenarios where the text discusses a serious event like a terrorist attack, but the retrieved image represents an unrelated context, such as fitness or fashion, the ensemble model can effectively identify these inconsistencies and classify the news as fake. This suggests that the combination of models allows for a more nuanced understanding of multimodal content, which is critical for detecting image-heavy fake news. Moreover, the stacked ensemble approach leverages the complementary strengths of individual models. Transformer-based models excel at handling nuanced linguistic features, such as sarcasm, misinformation cues, and sentiment shifts, which are common in text-heavy fake news. ViLBERT’s image–text alignment capabilities play a crucial role in identifying inconsistencies in image-heavy fake news where visual deception is prevalent. By combining the outputs of these specialised models, the ensemble approach achieves more accurate results across both text-heavy and image-heavy fake news cases.

The findings also highlight broader implications for misinformation countermeasures. By achieving 96% accuracy on the large-scale Fakeddit dataset and 94% on the culturally distinct Weibo dataset, the proposed approach demonstrates strong generalisation across different languages, platforms, and misinformation styles. This suggests that ensemble-based multimodal architectures can mitigate dataset-specific biases more effectively than single-model solutions. Furthermore, the framework’s ability to detect evolving fake news tactics—such as incremental modifications to existing true stories—offers promise for combating emerging threats, including AI-generated deepfakes and synthetic media, where visual authenticity is increasingly difficult to assess manually.

From a societal perspective, improving automated fake news detection at this level can support platform moderation, fact-checking organisations, and public awareness initiatives, potentially reducing the spread of harmful misinformation during critical events (e.g., elections, public health crises). However, deployment must be accompanied by careful consideration of ethical issues, including potential biases in training data and the risk of over-reliance on automated systems for content moderation.

Despite their differences—Fakeddit’s informal, satirical content and Weibo’s culturally specific, domain-specific news—the EMFND framework generalises well and performs strongly on both datasets. These datasets contain potential biases that may limit generalisation to real-world misinformation. Fakeddit shows lexical biases, such as over-reliance on entities (e.g., proper nouns) and a Reddit-specific satire style, which can push the model toward surface cues instead of deeper context, especially for text-heavy fake news. Weibo has time-related, domain-specific (daily-life news), and cultural biases, affecting performance on other platforms or languages. Moreover, platforms differ in linguistic structures, posting styles, user interactions, language formality, and content types (image- vs. text-heavy), further constraining transferability. These platform-specific biases may limit the model’s ability to generalise across domains. To address this, we used Image–Text Contextual Similarity analysis to detect misalignments between text and images in news posts, such as misleading headlines paired with unrelated images. This is key to improving robustness to text–image discrepancies. Although oversampling and SMOTE addressed class imbalance, further work is needed to strengthen robustness against evolving misinformation tactics (e.g., AI-generated content and deepfakes) and to enhance generalisation across platforms, languages, and posting styles in real-world settings.

Although the EMFND framework integrates several large pre-trained models, this design choice is justified by the clear performance advantages over baselines, as the ensemble leverages complementary architectural strengths to address multimodal challenges that individual models cannot adequately handle. Each component adds distinct, complementary capabilities: ViLBERT aligns modalities, Bi-GRU captures bidirectional sequences, Transformer-XL models long-range dependencies, DistilBERT encodes context efficiently, XLNet improves robustness via permutation training, and T5 fuses ensemble predictions. Computational cost is reduced through lightweight variants and parameter sharing, enabling training and inference on standard GPUs. Future work includes quantisation and knowledge distillation to further speed up inference and improve real-time scalability. Ongoing work on quantisation and knowledge distillation will further reduce resource requirements, enhancing real-time applicability and deployment on edge devices while preserving the detection accuracy that justifies the current design.

Limitations

Although the ensemble model is successful, it has limitations. The ensemble approach requires balanced textual and visual information. Predominantly text-based articles or those lacking meaningful images hinder the model’s multimodal capabilities. This results in lower accuracy for detecting text-only or image-scarce fake news. Additionally, fake news using advanced image manipulation closely matching the text might elude detection, as the model depends on clear image–text inconsistencies.

9. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed the Ensemble-based Multimodal Fake News Detection framework, which integrates ViLBERT’s cross-modal architecture with VADER sentiment analysis and Image–Text Contextual Similarity features. By leveraging a stacked ensemble of Bi-GRU, Transformer-XL, DistilBERT, and XLNet classifiers—combined via soft voting and a T5 meta-classifier—the model effectively captures textual nuances, visual cues, and cross-modal inconsistencies. Experimental results show that the proposed model outperforms the current state of the art on the Fakeddit and Weibo multimodal datasets, showing robust performance across domains with strong generalisation across diverse domains and languages. Ablation studies further validate the contributions of individual components, confirming the framework’s efficiency and robustness in detecting sophisticated misinformation. Its efficient design, confirmed by an ablation study, still allows for enhancements, particularly in handling complex fake news cases with video or audio. We plan to incorporate multimedia sources to improve accuracy and integrate domain-specific features to address challenges and broaden its platform applications in the future. Moreover, we will work towards minimising the computational complexity of the proposed framework, which is currently reliant on large pre-trained models (ViLBERT and XLNet), necessitating considerable memory and processing resources. This poses scalability challenges, particularly in the context of real-time applications or when handling extensive datasets. This limitation will be addressed in future work through the implementation of quantisation and knowledge distillation. Our objective is to reduce the size and memory demands of the model without significantly affecting its performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z., H.E. and F.C.; Methodology, M.A., H.Z., A.J. and M.S.; Software, M.A. and O.M.; Investigation, O.M.; Resources, O.M.; Data curation, M.S.; Writing—original draft, M.A., A.J., Z.T. and F.C.; Writing—review and editing, O.M., H.E. and F.C.; Visualization, A.J., Z.T. and F.C.; Supervision, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Fakedit at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1911.03854, reference number [14], as well as in Weibo at https://doi.org/10.21227/hjmr-kr22, reference [47].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Biradar, S.; Saumya, S.; Chauhan, A. Combating the infodemic: COVID-19 induced fake news recognition in social media networks. Complex Intell. Syst. 2023, 9, 2879–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Almazroi, A.A. Effectiveness of fine-tuned BERT model in classification of helpful and unhelpful online customer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 2737–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angizeh, L.B.; Keyvanpour, M.R. Detecting Fake News using Advanced Language Models: BERT and RoBERTa. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Web Research (ICWR), Tehran, Iran, 24–25 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mende, M.; Ubal, V.O.; Cozac, M.; Vallen, B.; Berry, C. Fighting Infodemics: Labels as Antidotes to Mis- and Disinformation?! J. Public Policy Mark. 2024, 43, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Arora, A. Assessment of bidirectional transformer encoder model and attention based bidirectional LSTM language models for fake news detection. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asudani, D.S.; Nagwani, N.K.; Singh, P. Impact of word embedding models on text analytics in deep learning environment: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 10345–10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.I.; Ahmed, K.; Li, D.; Zheng, Z.; Naheed, H.; Muaad, A.Y.; Alqarafi, A.; Abdel Hameed, H. SHO-CNN: A metaheuristic optimization of a convolutional neural network for multi-label news classification. Electronics 2022, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, W.; Hoi, S.C. Knowledge Enhanced Vision and Language Model for Multi-Modal Fake News Detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 8312–8322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ab Ghani, N.; Ahmed, M. A review on recent advances in Deep learning for Sentiment Analysis: Performances, Challenges and Limitations. Compusoft 2020, 9, 3775–3783. [Google Scholar]