Abstract

This paper develops profile score confidence intervals (i.e., z-standard intervals) by inverting orthogonalized score estimators for comparing two independent binomial proportions in rate difference, rate ratio, or odds ratio and utilizes a generalized estimation framework of Vos and Wu (Inf. Geom. 8: 99–123, 2025) to evaluate different confidence interval methods. The orthogonalized score estimators dominate other generalized estimators in -efficiency for distinguishing parameter values around the truth, so the z-standard intervals become more efficient and acquire coverage closer to the nominal level than other types of confidence intervals. In addition, the degrees of freedom and small-sample corrections (applied to the profile nuisance parameter estimates) are expected to improve the coverage of the z-standard intervals and help maintain them above the nominal level. Computational algorithms are developed to find the z-standard intervals using R’s polyroot function. Numerical studies are conducted to compare both coverage and endpoints of different types of confidence intervals.

MSC:

62B10; 62B11

1. Introduction

Building on extensive work in the comparative analysis of two independent binomial proportions (see, e.g., [1,2,3]), this paper presents a novel framework for assessing different confidence interval methods. Three parameters of interest—the rate difference (RD), rate ratio (RR), and odds ratio (OR)—are commonly used for inference in two-by-two comparative trials and the relative performance of their corresponding confidence intervals requires a careful evaluation. Our proposed approach uses a generalized estimation and information assessment developed by Vos and Wu [4] to provide a new perspective, specifically on the properties of the profile score confidence intervals. The analysis considers the classic setting where data are represented in a two-by-two contingency table (e.g., Table 1) with fixed group sample sizes and .

Table 1.

2 × 2 contingency table.

Due to the discrete nature of the data, existing methods, such as the classic Wald confidence interval, often generate wide intervals to ensure coverage. Sometimes, corrections for small samples, such as the well-known plus-four (or Wilson) confidence interval covered in most introductory statistics textbooks, are implemented and further exacerbate the over-coverage issue. In this paper, we propose the profile score confidence intervals by inverting the orthogonalized score estimators and demonstrate their superior information and coverage properties.

1.1. Generalized Estimation and Information Framework

Following the generalized estimation framework of Vos and Wu [4], we consider a two-parameter model defined on a manifold of distributions. For the Bernoulli distribution with success parameter , the sample space for the number of successes in trials is and the sampling measure is . Thus, for the data in Table 1, the sample space is and the two-parameter manifold of the joint distributions of the numbers of successes from the two samples is

In general, let M be a two-dimensional manifold of distributions on a common support , and let be a global parameterization of the distributions such that . For example, can be any reparameterization of in the Bernoulli example (1). For any distribution , and are regular submanifolds, where and . The parameter space for the submanifold is and similarly, the parameter space for is .

In statistical applications, the two parameters and are usually assigned distinct inferential roles. The parameter of interest represents the attribute relevant to the research question, while the nuisance parameter is necessary to specify the full distribution but is not of direct inferential concern. A key objective is to ensure that inferences about both parameters are invariant to reparameterization. For example, if represents the log odds ratio, inferences should be invariant to a change in parameterization to the odds ratio or any reparameterization that are diffeomorphisms. This principle of parameter invariance is equally important for both the parameter of interest and the nuisance parameter. The inference for must also not change if a different nuisance parameterization is considered. Parameter invariance allows us to choose parameterizations that are convenient for computations.

A generalized estimator for is a real-valued function g with domain having the following properties. For any fixed value of the nuisance parameter and almost every , is a smooth function on the parameter space . To achieve nuisance parameterization invariance, we use the residual of g after projecting it onto the score function for the nuisance parameter, . This projection yields the invariant estimator , defined as:

where E and V denote the expectation and variance operators, respectively. This invariant estimator is then standardized to create . For each distribution m, the function represents a standardized distribution with mean of zero and variance of one.

According to Vos and Wu [4], the generalized estimator possesses both distributional and geometric properties. For a given distribution , the distribution of has a mean of zero and a variance of one, and is uncorrelated with the nuisance parameter score, . Geometrically, within the submanifold (defined by a fixed nuisance parameter ), and are orthogonal vector fields. This implies that for any point m on the one-dimensional submanifold , is a direction vector that is orthogonal to the tangent space of the nuisance parameter submanifold at that point.

When the generalized estimator g is the score for the parameter of interest, , we use the notation for . To compare K estimates, we can plot the functions for on the parameter space for a fixed nuisance parameter value . This approach is particularly feasible in the binomial setting, where the finite number of sample outcomes allows for an exhaustive comparison. While the choice of may depend on the observed data, it must be held constant across all estimates during a given comparison.

While generalized estimators can serve as estimating functions in the sense of Liang and Zeger [5], they are fundamentally distinct. Generalized estimators offer direct means for constructing confidence intervals and conducting hypothesis tests, but more importantly, they provide a meaningful summary of the information captured by the data regarding different parameter values. The (nuisance orthogonalized Fisher) information for the parameter of interest, , utilized by an estimator g is quantified by its standardized version, , as (or in the presence of nuisance parameters). When comparing generalized estimators using -information, the Cramer-Rao lower bound for the variance of point estimators becomes the -information upper bound. This upper bound is the orthogonalized Fisher information, which the orthogonalized score attains . There is a simple relationship between the -information of g and the orthogonalized score

where is the correlation between and . The -efficiency of any g is the ratio of its -information to the upper bound

where the last equation follows from (2). We leverage this generalized estimation framework to develop profile score estimators for the RD, RR, and OR, and demonstrate their optimality in terms of -information.

1.2. Existing Confidence Interval Methods

In the two-by-two comparative trials, let for . The maximum likelihood estimators (MLEs) for the probabilities are and . The classic Wald confidence intervals rely on the asymptotic normality of the MLEs. For RR and OR, the Wald confidence intervals are given in the logarithm of these parameters.

- Rate Difference (RD) For the rate difference, , the MLE is and the

Wald confidence interval is found by solving

where the estimated variance is , and is the upper

quantile of the standard normal distribution.

- Log Rate Ratio (RR) For the log rate ratio, , the MLE is

and the Wald confidence interval is found by solving

where the estimated variance is .

- Log Odds Ratio (OR) For the log odds ratio, , the MLE is

and the Wald confidence interval is found by solving

where the estimated variance is .

Wald confidence intervals are known to perform well for large samples but are often unreliable for small or moderate sample sizes [6]. Issues also arise with boundary conditions when the MLEs or are close to 0 or 1. Common approaches to address these issues include adding a small constant, such as 0.5 or 1, to each cell of the contingency table, as suggested by Agresti and Caffo [6]. For the RD, a continuity correction is sometimes applied by subtracting and adding to the interval endpoints (See, for example, [3], p. 60), while Hauck and Anderson [7] used as the continuity correction factor.

To improve small-sample performance, Miettinen and Nurminen [8] proposed a score-based method that inverts a chi-squared test for the null hypothesis (e.g., ). For the RD, the confidence interval is found by solving

for , where the variance estimate is based on the restricted MLEs that satisfy the null hypothesis . Similarly, for the RR, their approach involves solving

for (or for ), where the variance estimate is based on the restricted MLEs such that . Because the variance terms depend on the unknown parameter values, these solutions typically require an iterative algorithm. Miettinen and Nurminen [8] did not develop a similar interval for the OR due to the complexity of the variance term, instead favoring a likelihood-based approach. Other related methods include Mee [9]’s confidence interval, which omits the degrees of freedom (DF) correction factor from the variance term, and Beal [10]’s RD interval, which is similar to Miettinen and Nurminen [8]’s approach.

For the RD, Newcombe [11] proposed a hybrid score confidence interval based on the one-sample Wilson score confidence limits, which was later discussed by Barker et al. [12]. An exact unconditional confidence interval for the RD was proposed by Santner and Snell [13] and further discussed by Agresti [14], Chan and Zhang [15], Agresti and Min [16], and Santner et al. [17]. Other confidence interval methods for the RR include the likelihood ratio confidence interval [8,18] and the exact unconditional confidence interval [13,14,16,17,19], while other confidence interval methods for the OR include the likelihood ratio confidence interval [20], the median unbiased (Midp) conditional confidence interval [21], and the well-known Fisher’s exact (conditional) confidence interval. All these confidence interval methods have been implemented in SAS version 9.4 and later through its Proc Freq procedure (SAS Institute Inc. 2023, Cary, NC, USA).

The methods of Miettinen and Nurminen [8], Mee [9], and Beal [10] for the RD share the same generalized estimator format, , and thus have the same -efficiency as the Wald estimator. The difference among these methods lies mainly in how the nuisance parameter in the variance term is estimated. However, the small-sample correction, such as adding 0.5 or 1 to each cell count, introduces a new estimator with a lower -efficiency but potentially higher small-sample coverage.

A key contribution of the generalized estimation framework by Vos and Wu [4] is the -efficiency as a local property that quantifies an estimator’s ability to distinguish parameter values around the truth. This framework also reveals that for the RR, the generalized estimator is the score estimator. Thus, this estimator dominates other ones, such as the small-sample corrected Wald estimator, , in terms of -efficiency. The same holds for the OR, where the score estimator developed in this paper dominates other estimators, including the small-sample corrected Wald estimator, .

2. Profile Score Confidence Intervals

This section details the derivation of the profile score confidence intervals for the RD, RR, and OR within the context of a one-parameter exponential family by inverting the orthogonalized score estimators. Utilizing a one-parameter exponential family enables us to provide a unified derivation for all three parameters of interest. Our main focus is on the analysis of 2 × 2 Comparative Trials.

2.1. Analysis of 2 × 2 Comparative Trials

Consider a one-parameter exponential family with probability density or mass function , where is the natural parameter. For this family, the mean of the sufficient statistic is given by and its variance is (see, e.g., [22] (pp. 109–137) for more details). The Bernoulli(p) distribution is a member of this family with , , and .

Assume we have independent samples and , respectively, from two distributions within this exponential family, denoted for . We define the sufficient statistics as the sample means . The log-likelihood function for the sufficient statistics, parameterized by a parameter of interest and a nuisance parameter is given by:

where can be any reparameterization of .

The scores for and are found by differentiating the log-likelihood:

where and are used for notational convenience. The covariance between the two score functions is

and the variance of the nuisance score function is

According to Vos and Wu [4], the orthogonalized score estimator for is

with its standardized version

The generalized score estimator is orthogonal to the nuisance tangent space and achieves the information upper bound. A profile score confidence interval for can then be obtained by solving , using the profile likelihood estimate for the nuisance parameter (by solving the nuisance parameter score equation ). This method is called the z-standard interval.

Theorem 1 (Parameter Invariance).

If the parameter of interest θ and the nuisance parameter τ are two different smooth functions of the parameters and for the two populations, the standardized score estimator (6) for θ when orthogonalized to the nuisance tangent space is parameterization invariant to both θ and τ.

Proof.

The inverse Jacobian rule shows that

and the chain rule shows that

If another nuisance parameter was used, we will write

and this holds true for any parameter of interest . When and are substituted into (6), the part in the numerator and denominator cancels out and the estimator remains unchanged. Thus, (6) is parameterization invariant to the nuisance parameter .

To show (6) is parameterization invariant to the parameter of interest , we just need to rewrite it as

following (7). If another parameter of interest was used, we will write

and this holds true for any nuisance parameter . When and are substituted into (8), the part in the numerator and denominator cancels out and the estimator remains unchanged. □

As shown in Cox and Reid [23], for each parameter of interest, there exists an orthogonal nuisance parameterization. For the mean difference , is an orthogonal nuisance parameterization because it leads to orthogonal scores with . To see this, we just need to use the inverse Jacobian rule (7) and substitute these partial derivatives into (5). Similarly, for the log mean ratio, , is an orthogonal nuisance parameterization, while for the natural parameter difference , is an orthogonal nuisance parameterization. Due to the parameterization invariant properties of (6), these nuisance parameters , , and can be used equivalently for all three parameters of interest , , and . For each parameter of interest, the standardized estimator (6) simplifies to a unique form, regardless of the nuisance parameterization.

- Mean Difference For the mean difference, , the standardized score estimator

simplifies to

The information upper bound achieved by this estimator is

. The nuisance parameter score equation simplifies to

.

- Log Mean Ratio For the log mean ratio, , the standardized score estimator

simplifies to

The information upper bound achieved by this estimator is

. The nuisance parameter score equation simplifies to

.

- Natural Parameter Difference For the natural parameter difference, , the

standardized score estimator simplifies to

The information upper bound achieved by this estimator is

. The nuisance parameter score equation simplifies to

. This equation leads to a simplified profile nuisance parameter estimate

, which is independent of the parameter of interest and greatly

simplifies the computation.

The standardized score estimator is parameter invariant and has -information that achieves the Fisher information bound. As -information is a local property, we consider finite samples in Section 3.2 to assess the extent to which the theoretical optimality of -efficiency translates to superior confidence intervals.

2.2. Analysis of Independence

Although this paper focuses on comparing two independent proportions arising from two-by-two comparative trials, it is worthwhile to consider other related designs, such as the design that samples from a single combined population and inferences for independence between two categorical variables. In this latter design, the analysis is conditioned only on the total sample size, N, but not on the group sample sizes and .

In a combined population, the proportions of individuals in the exposure and control groups, respectively, and , are themselves unknown, introducing an additional nuisance parameter, . Assuming that the probability of an individual being sampled is independent of their outcome, the log-likelihood function for this model, parameterized by the parameter of interest (e.g., ) and the two nuisance parameters, and , can be expressed as:

A key assumption of this model is that the parameter of interest, , and the nuisance parameter, , are fundamentally unrelated to the nuisance parameter, . Consequently, the score function s for and the score function for remain unchanged from (3) and (4), respectively. The score for the nuisance parameter is given by the partial derivative

so the covariances among the score functions satisfy .

After orthogonalization to the nuisance scores and standardization, the standardized score estimator for retains the same structural form as (6). The only adjustment required is to replace the variance term in the denominator with its expected value. However, the estimators (9)–(11) are still their profile versions (after substituting the expected variances for their MLEs) to find the z-standard intervals in the same manner as in the two population case.

2.3. Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

In randomized controlled trials, however, a conditional analysis is performed by fixing not only the group sample sizes, and , but also the total number of “successes”, , and “failures”, . This approach yields a conditional probability mass function for the number of successes in the first group, , given the fixed marginal totals.

The conditional probability mass function for is given by

where represents the log odds ratio and is the normalizing constant defined as:

A significant advantage of this approach is that the conditional log-likelihood function depends only on the parameter of interest, , and contains no nuisance parameters. This simplifies inference substantially.

The score function for is derived as the first derivative of the log-likelihood: and the variance of the score function is The z-standard interval for can be found by solving , where .

This conditional likelihood approach is particularly well-suited for the odds ratio. For this design, an alternative and often preferred method for constructing confidence intervals is Fisher’s exact (or Midp) confidence interval for the odds ratio. Using other parameterizations, such as the RD or RR, would reintroduce nuisance parameters, leading to more complex calculations than the odds ratio.

3. Numerical Studies

This section first discusses algorithms in computing the z-standard intervals for the RD, RR, and OR. R’s polyroot function is utilized for polynomial root finding. Special attentions are given to the profile likelihood estimates of the nuisance parameters, and a couple of correction factors are proposed. Second, this section uses numerical studies to establish the superiority of the z-standard intervals, especially with the DF and small-sample corrections, in finite-sample coverage, in the sense of maintaining coverage close to the nominal level.

3.1. Computational Details

For comparative analysis of two independent proportions or analysis of independence in a two-by-two table, the z-standard interval for the log odds ratio (or equivalently the odds ratio ) can be constructed by solving

where is the chosen nuisance parameter. The profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter is simply regardless of . When the observed data correspond to the extreme cases or , nothing can be learned about and thus we always report as the z-standard interval for or (0, ) as the z-standard interval for the OR. In comparison, the SAS Proc Freq procedure does not report any confidence intervals for these extreme cases.

A similar DF correction as that of Miettinen and Nurminen [8] to the z-standard intervals can be achieved by multiplying the critical value with the factor . The DF correction is expected to widen the z-standard intervals and improve their coverage. However, the small-sample correction like those in Agresti and Caffo [6] is only recommended for the profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter via the mean sufficient statistics:

for some small constant . The small-sample correction is not only expected to widen the z-standard intervals but also help with the extreme cases. Although (12) is the same as that of Miettinen and Nurminen [8] for the OR, our treatment of the nuisance parameter and its small-sample correction is unique.

When both and for are nonzero, (12) simplifies to a 6-degree polynomial equation in , where . This equation has six real or complex roots, from which an appropriate interval can be determined by testing . When R’s polyroot function is used, the middle two real roots correspond to the z-standard interval except for the two extreme cases. The z-standard interval for or is then obtained from those of and . The advantage of using R’s polyroot function is that it has no convergence issue and executes very fast compared to other root-finding procedures.

Similarly, the z-standard interval for the rate difference can be found from solving

where the profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter can be obtained from solving

For the convenience of comparison, we adopt the same nuisance parameter but it works equivalently if was chosen instead. But no matter which nuisance parameter is used, its profile likelihood estimate depends on the parameter of interest . Starting from an initial nuisance parameter value, e.g., , we can solve (14) for an initial interval for . After that, an iterative algorithm between (14) and (15) can be carried out until convergence to find the z-standard interval for . In our numeric studies, the iteration often converges within 30 steps when a threshold of is used for changes in successive parameter values. The numerical procedure experiences no issue with extreme cases because the RD is not a ratio. In comparison, the classic Wald confidence interval will report (0, 0) for the two extreme cases, which we do not think provides any practical guidance to the true RD.

Lastly, the z-standard interval for the log rate ratio (or equivalently the rate ratio ) can be found from solving

where the profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter can be obtained from solving

We again adopt the same nuisance parameter and use a similar iterative algorithm as previously described to find the z-standard interval for or the RR. This procedure may have convergence issues when , in which case we assign to the upper limit, or when , in which case we report as the z-standard interval for the RR.

The z-standard intervals for the RD and RR should be the same as those of Mee [9], and similar DF and small-sample corrections as those for the OR can be applied (to the profile nuisance parameter estimates via the sufficient statistics).

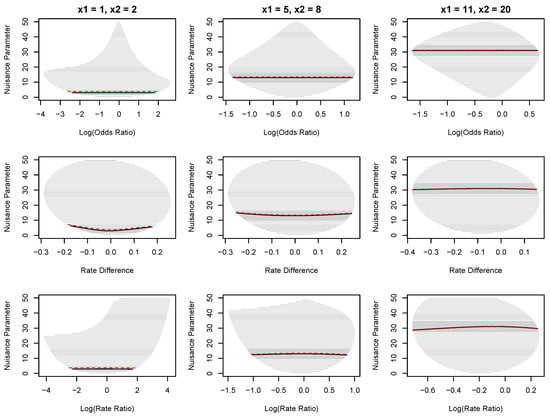

Figure 1 shows three examples for comparing two independent binomial proportions with and , respectively. The numbers of successes are and in the first example, and in the second example, and and in the third example. For the log odds ratio, the profile likelihood estimates of the nuisance parameter are , 13, and 31, respectively, in the three examples and the z-standard intervals are represented by the horizontal bold-faced segments. For the rate difference and log rate ratio, however, the profile likelihood estimates of the nuisance parameter are represented by the bold-faced curves, and the z-standard intervals are the projections of the curves to the horizontal axis. Figure 1 also includes some horizontal grayed segments representing what the z-standard intervals could be if different nuisance parameter values had been specified a priori, where the gray shaded area represents nuisance parameter values that are within one standard deviation of .

Figure 1.

Three examples of z-standard intervals for the log(OR), RD, and log(RR) comparing two independent binomial populations. The sample sizes are for all examples, and the numbers of successes are for the first example, for the second example, and for the third example. For the log(OR), the bold-faced segments represent the z-standard intervals at the profiled nuisance parameter estimates . For the RD and log(RR), the bold-faced curves depict the corresponding profile nuisance parameter estimates at each parameter of interest value. The projection of each curve to the horizontal axis gives the corresponding z-standard interval. Other grayed horizontal segments in the plots represent the potential z-standard intervals at each pre-specified nuisance parameter value, where the gray shaded area represents nuisance parameter values that are within one standard deviation of . The red dashed segments/curves represent z-standard intervals with the small-sample correction ().

In the generalized estimation framework of Vos and Wu [4], the parameter spaces for both and are so the parameter space for the nuisance parameter is . When the data correspond to the extreme cases or , the estimators considered in this paper do not exist without the small-sample correction. In addition, as shown in Figure 1, different nuisance parameter values could greatly impact the z-standard intervals. As a remediation, we could report the widest interval for nuisance parameter values within one standard deviation of . This remediation is often conservative, but it could sometimes report intervals that are too narrow, e.g., in the RD case when and . Our numerical studies in Section 3.2 suggest that the small-sample correction () to the profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter provides a reasonable remediation, as represented by the red dashed segments/curves in Figure 1.

3.2. Coverage and Confidence Interval Width

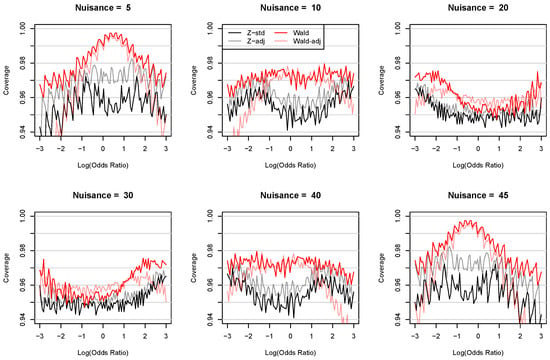

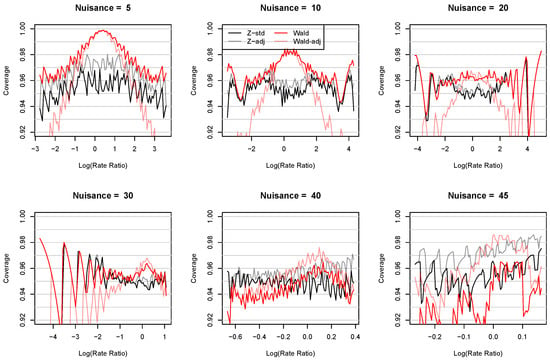

Consider two independent binomial distributions with and at 600 combinations of true log odds ratio and nuisance parameter values. These combinations cover values ranging from −3 to 3 and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45. Figure 2 compares the coverage of the z-standard intervals of the log(OR) with (Z-adj) and without (Z-std) the DF and small-sample corrections () to those of the Wald confidence intervals with (Wald-adj) and without (Wald) the small-sample correction ().

Figure 2.

Coverage of the z-standard intervals of the log(OR) with (Z-adj) and without (Z-std) the DF and small-sample corrections () compared to those of the Wald confidence intervals with (Wald-adj) and without (Wald) the small-sample correction () under a nominal level of 0.95. Two independent binomial distributions are used with and at 600 combinations of true log odds ratio and nuisance parameter values. These combinations cover values ranging from −3 to 3 and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45. When or or when or , the Wald confidence intervals for the log(OR) are (, ).

Figure 2 shows the coverage of each type of confidence intervals at a nominal level of 0.95. The discrete nature of the problem makes a zig-zag pattern in the coverage as the true parameter value crosses the interval limits. For maintaining coverage, the Wald methods tend to report wide confidence intervals, especially when the observed data are near the extremes. The DF and small-sample corrections in (13) are expected to widen the z-standard intervals and improve their coverage. Using more aggressive small-sample corrections, e.g., for some , will lead to more aggressive coverage corrections, but we may need to consider the trade-off because coverage varies with the underlying true parameter values as shown in the figure.

Observations from Figure 2 include (1) the coverage of the Wald confidence intervals are always higher than those of the z-standard intervals, (2) the DF and small-sample corrections improve the coverage of the z-standard intervals as expected, and (3) the small-sample correction to the Wald confidence intervals may significantly lower their coverage when is far away from zero. But the most important takeaway is that the z-standard intervals are the best in maintaining the coverage close to the nominal level of 0.95 and the DF and small-sample corrections can help them stay above the nominal level. Note that the small-sample correction to the z-standard intervals is only applied to the profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter . For this reason, it acquires the predictable effect of producing wider intervals. In comparison, the small-sample correction to the Wald intervals is applied to the confidence intervals themselves and has varying effects.

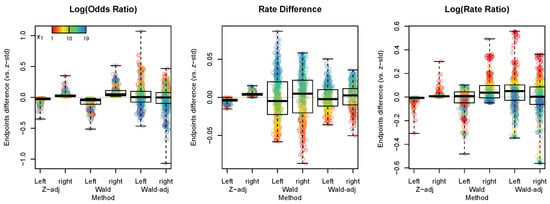

To better understand these confidence intervals, their endpoints are compared in the left plot of Figure 3 with the endpoints of the z-standard intervals serving as the references. Because of the difficulties with the Wald intervals, Figure 3 only includes the confidence intervals for and . The plot shows that (1) the DF and small-sample corrections widen the z-standard intervals as expected, (2) the Wald confidence intervals are always wider than and contain the z-standard intervals, and (3) the small-sample corrected Wald intervals are shifted relative to the z-standard intervals. In fact, for small values, they tend to shift to the right, while for large values, they tend to shift to the left. These findings echo those from the coverage.

Figure 3.

A comparison of confidence interval endpoints generated in the coverage studies with and as presented in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 using those of the z-standard intervals (Z-std) as references. The color scale corresponds to the values so that the red color represents small values, while the blue color represents large values. When both endpoints of a particular confidence interval are higher than those of the corresponding z-standard interval (i.e., showing positive differences), the interval is shifted to the right relative to the z-standard interval. When both endpoints show negative differences, the interval is shifted to the left relative to the z-standard interval. When the right endpoint shows a positive difference and the left endpoint shows a negative difference, the interval contains the z-standard interval.

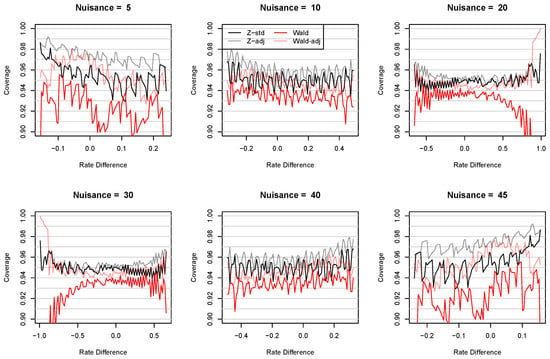

Next, consider a similar setting consisting of two independent binomial distributions with and at 600 combinations of true rate difference and nuisance parameter values. These combinations cover values ranging from −0.9833 to 0.9833 and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45. Under this setting, not all values are permissible for a given value. For example, when , only are permissible. Figure 4 shows a comparison of the coverage of the four types of confidence intervals for the RD over the permissible ranges of . The z-standard intervals are still the best in maintaining the coverage close to the nominal level, and the DF and small-sample corrections can help them stay above the nominal level. The coverage of the Wald intervals can change drastically, while those of the small-sample corrected Wald intervals are relatively more stable.

Figure 4.

Coverage of the z-standard intervals of the RD with (Z-adj) and without (Z-std) the DF and small-sample corrections () compared to those of the Wald confidence intervals with (Wald-adj) and without (Wald) the small-sample correction () under a nominal level of 0.95. Two independent binomial distributions were used with and at 600 combinations of true rate difference and nuisance parameter values. These combinations cover values ranging from −0.9833 to 0.9833 and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45.

The endpoint comparisons in the middle plot of Figure 3 show that the DF and small-sample corrections still, as expected, widen the z-standard intervals. However, both Wald confidence intervals with and without the small-sample correction are shifted relative to the z-standard intervals. Particularly, for small values, they tend to shift to the left, while for large values, they tend to shift to the right.

Next, Figure 5 shows the coverage of the four types of confidence intervals for the log(RR) at 600 combinations of true log rate ratio and nuisance parameter values and the right plot in Figure 3 shows a comparison of their endpoints. These combinations cover values ranging from −4.5985 to 5.0006 and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45. This setting also faces an issue that not all values are permissible. Figure 5 shows that the coverage of all confidence intervals may change drastically when is far away from 0. In these cases, the small-sample corrected Wald confidence intervals performed even worse than their original counterparts, and even the z-standard intervals with or without the corrections may fail. These results suggest that inference for the RR may not be the best choice in certain situations where extreme parameter values are expected. This may be because of the asymmetrical nature of RR and the effect of small denominators.

Figure 5.

Coverage of the z-standard intervals of the log(RR) with (Z-adj) and without (Z-std) the DF and small-sample corrections () compared to those of the Wald confidence intervals with (Wald-adj) and without (Wald) the small sample correction () under a nominal level of 0.95. Two independent binomial distributions were used with and at 600 combinations of true log rate ratio and nuisance parameter values. These combinations cover values ranging from −4.5985 to 5.0006 and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45. When or , Wald confidence intervals for the log(RR) are (, ).

The right plot in Figure 3 shows that the Wald confidence intervals tend to be wider than the z-standard intervals for small values and narrower for large values. On the other hand, the small-sample corrected Wald confidence intervals are shifted relative to the z-standard intervals so that they tend to shift to the right for small values and to the left for large values.

Finally, Table 2 contains a more comprehensive comparison of coverage probabilities between the z-standard intervals with (Z-adj) and without (Z-std) the DF and small-sample corrections () and many existing ones. The existing methods under comparison include Wald confidence interval with (Wald-adj) and without (Wald) the small-sample correction () and all confidence interval methods implemented by the Proc Freq procedure in SAS 9.4. For the RD, these include Agresti and Caffo [6], which is a Wald interval with a small-sample correction of , the exact unconditional confidence interval, the Hauck and Anderson [7] confidence interval with a continuity correction factor of , and the Newcombe [11] hybrid score confidence interval. For the RR, these include the likelihood ratio and the exact unconditional confidence interval, while for the OR, these include Fisher’s exact (conditional), likelihood ratio, and Midp (conditional) confidence intervals.

Table 2.

A comparison of coverage probabilities among different confidence interval methods for the RD, RR, and OR for three sample size settings where = (20, 30), (30, 30), or (30, 20). Coverage probabilities are calculated at 600 combinations of the true parameter of interest and nuisance parameter values. These combinations cover values ranging from −3 to 3, values ranging from about −0.98 to 0.98, values ranging from about −4.6 to 5.0, and values at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 45. The z-standard intervals (Z-adj and Z-std) and the Wald confidence intervals (Wald-adj and Wald) with and without the corrections are generated using R code, while the other confidence intervals are generated using the SAS Proc Freq procedure applied to the entire sample space. The SAS Proc Freq procedure does not provide any confidence intervals for the two extreme cases where or . In these cases, either the widest possible intervals are reported or an R package (R 4.5.1) (if available for a particular method) is implemented, such as the contingencytables package for the Newcombe hybrid score method.

The results in Table 2 confirm that the z-standard interval is the best in maintaining the coverage close to the nominal level, and the DF and small-sample corrections can help its coverage stay above the nominal level. For the RD, the Wald confidence interval undercovers and the small-sample correction helps improve their coverage, while the method of Agresti and Caffo [6] performs reasonably well. For the RR, all confidence intervals may undercover except the exact unconditional method, which overcovers. For the OR, the Wald and Fisher’s exact confidence intervals may overcover, and the likelihood ratio confidence interval may undercover, while the Midp interval performs reasonably well.

4. Discussion

This paper develops the z-standard confidence intervals for the rate difference, rate ratio, and odds ratio using the generalized estimation framework of Vos and Wu [4]. The orthogonalized score estimator dominates other estimators in -efficiency for distinguishing parameter values around a neighborhood of their truth. As a result, the z-standard intervals are typically narrower than others and better at maintaining coverage close to the nominal level. Moreover, the DF and small-sample corrections are expected to help them maintain coverage above and closely around the nominal level. Numerical studies in this paper suggest that the less aggressive small-sample correction, i.e., , applied only to the profile likelihood estimate of the nuisance parameter via the mean sufficient statistics, may suffice. The computation of the z-standard intervals can be conveniently and efficiently achieved using R’s polyroot function. Thus, the z-standard interval developed in this paper represents a superior choice for inference practice in two-way contingency tables.

While this paper covers the three most frequently used study designs, i.e., the 2 × 2 comparative design, the analysis of independence design, and the randomized controlled design. The proposed method via the generalized estimation framework of Vos and Wu [4] may be applicable to other designs, such as the longitudinal design, which generates correlated proportions. Such more complicated designs may be of great future research interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.W. and P.V.; methodology, Q.W. and P.V.; software, Q.W.; validation, Q.W.; formal analysis, Q.W.; investigation, Q.W. and P.V.; resources, Q.W. and P.V.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W.; writing—review and editing, Q.W. and P.V.; visualization, Q.W.; project administration, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the review and editing of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini AI 2.5 for the purpose of grammar checking. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We also thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barnard, G.A. Significance Tests for 2 × 2 Tables. Biometrika 1947, 34, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hokoken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, J.L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. Statistical Methods forRates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hokoken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, P.W.; Wu, Q. Generalized estimation and information. Inf. Geom. 2025, 8, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.Y.; Zeger, S.L. Inference based on estimating functions in the presence of nuisance parameters. Stat. Sci. 1995, 10, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A.; Caffo, B. Simple and Effective Confidence Intervals for Proportions and Differences of ProportionsResult from Adding Two Successes and Two Failures. Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, W.W.; Anderson, S. A Comparison of Large-Sample Confidence Interval Methods for the Difference of Two Binomial Probabilities. Am. Stat. 1986, 40, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, O.; Nurminen, M. Comparative analysis of two rates. Stat. Med. 1985, 4, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mee, R.W. Confidence bounds for the difference between two probabilities. Biometrics 1984, 40, 1175–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, S.L. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for the Difference between Two Binomial Parametersfor Use with Small Samples. Biometrics 1987, 43, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcombe, R.G. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: Comparison of eleven methods. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, L.; Rolka, H.; Rolka, D.; Brown, C. Equivalence Testing for Binomial Random Variables. Am. Stat. 2001, 55, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santner, T.J.; Snell, M.K. Small-Sample Confidence Intervals for p1–p2 and p1/p2 in 2 × 2 Contingency Tables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1980, 75, 386–394. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. A Survey of Exact Inference for Contingency Tables. Stat. Sci. 1992, 7, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I.S.; Zhang, Z. Test-based exact confidence intervals for the difference of two binomial proportions. Biometrics 1999, 55, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresti, A.; Min, Y. On small-sample confidence intervals for parameters in discrete distributions. Biometrics 2001, 57, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santner, T.J.; Pradhan, V.; Senchaudhuri, P.; Mehta, C.R.; Tamhane, A. Small-sample comparisons of confidence intervals for the difference of two independent binomial proportions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 51, 5791–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, O. Theoretical Epidemiology: Principles of Occurrence in Research Medicine; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gart, J.J.; Nam, J. Approximate interval estimation of the ratio of binomial parameters: A review and corrections for skewness. Biometrics 1988, 44, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K.J.; Greenland, S. Modern Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O. Information and Exponential Families in Statistical Theory; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.R.; Reid, N. Parameter Orthogonality and Approximate Conditional Inference. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1987, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.