SCGclust: Single-Cell Graph Clustering Using Graph Autoencoders That Integrate SNVs and CNAs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Graph Construction

2.1.1. Edge Weight Adjacency Matrix

2.1.2. Node Features

2.2. Graph Autoencoder (GAT) Architecture

2.2.1. Encoder and Decoder

2.2.2. Attention Mechanism

2.3. Co-Training GAT and GCN

2.4. Gaussian Mixture Model for Clustering

3. Results

3.1. Simulated Dataset

3.1.1. Simulator

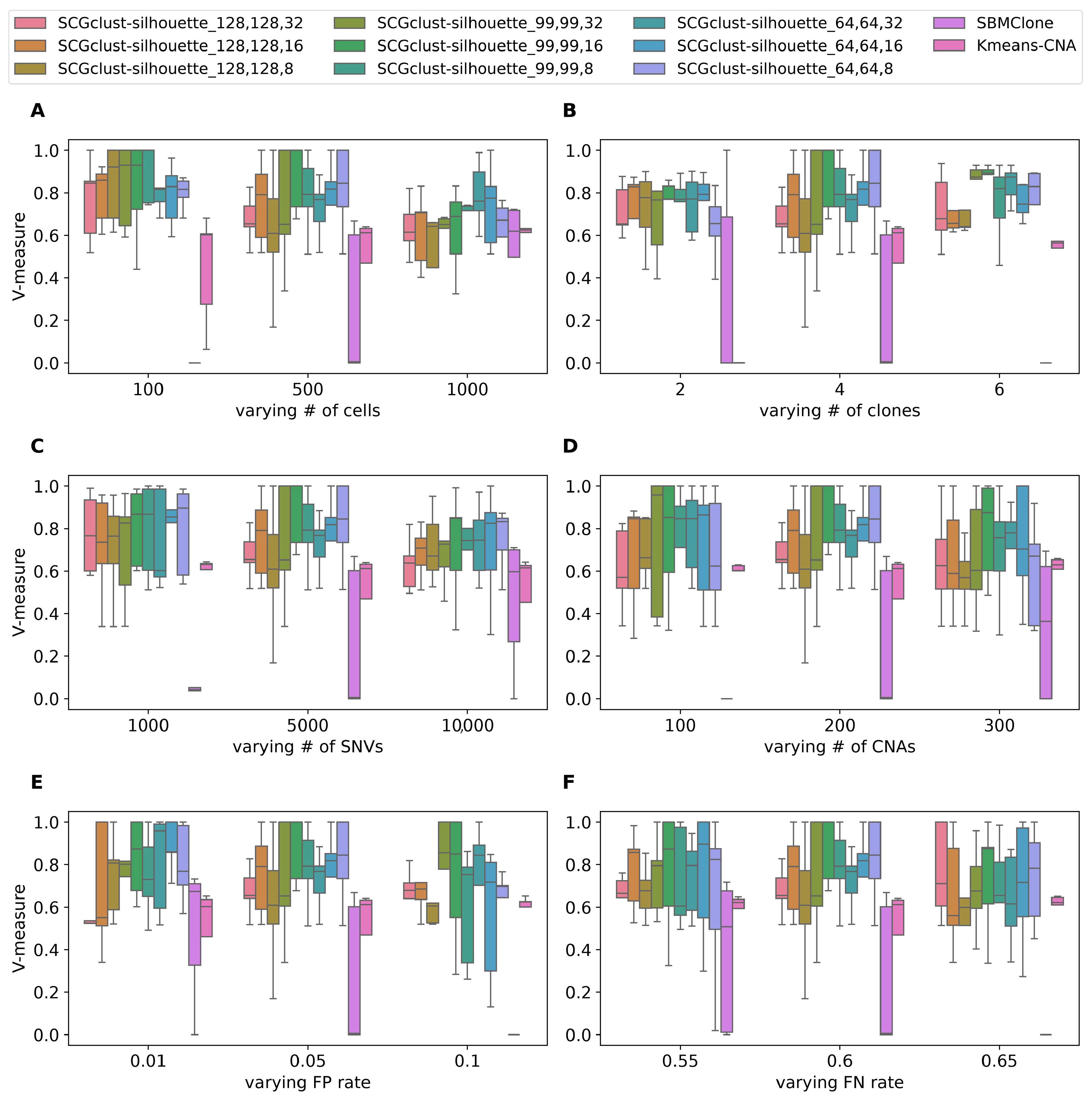

3.1.2. Benchmarking Results

3.1.3. Ablation Test: Comparison Among SCGclust, GCT, and GAT

3.1.4. Research Design and Choice of Hyperparameters

3.1.5. Runtime and Memory Consumption

3.2. Real Dataset

Self-Supervised Selection of the Optimal Number of Clusters in Real Data

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawrence, M.S.; Stojanov, P.; Polak, P.; Kryukov, G.V.; Cibulskis, K.; Sivachenko, A.; Carter, S.L.; Stewart, C.; Mermel, C.H.; Roberts, S.A. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature 2013, 499, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, R.A.; McGranahan, N.; Bartek, J.; Swanton, C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature 2013, 501, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turajlic, S.; Sottoriva, A.; Graham, T.; Swanton, C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, D.A.; Kessenbrock, K.; Davis, R.T.; Pervolarakis, N.; Werb, Z. Tumour heterogeneity and metastasis at single-cell resolution. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusyk, A.; Janiszewska, M.; Polyak, K. Intratumor heterogeneity: The rosetta stone of therapy resistance. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.P.; Bebb, C.E.; Nordenskjo, M.; Ponder, B.A.; Tunnacliffe, A. Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR: General amplification of target DNA by a single degenerate primer. Genomics 1992, 13, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navin, N.; Kendall, J.; Troge, J.; Andrews, P.; Rodgers, L.; McIndoo, J.; Cook, K.; Stepansky, A.; Levy, D.; Esposito, D.; et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature 2011, 472, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslan, T.; Kendall, J.; Rodgers, L.; Cox, H.; Riggs, M.; Stepansky, A.; Troge, J.; Ravi, K.; Esposito, D.; Lakshmi, B. Genome-wide copy number analysis of single cells. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 1024–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, H.; Steif, A.; Laks, E.; Eirew, P.; VanInsberghe, M.; Shah, S.P.; Aparicio, S.; Hansen, C.L. Scalable whole-genome single-cell library preparation without preamplification. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laks, E.; McPherson, A.; Zahn, H.; Lai, D.; Steif, A.; Brimhall, J.; Biele, J.; Wang, B.; Masud, T.; Ting, J.; et al. Clonal decomposition and DNA replication states defined by scaled single-cell genome sequencing. Cell 2019, 179, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Song, L.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, B.; Tao, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, F.; Wu, K.; Liang, J.; Shao, D. Single-cell exome sequencing and monoclonal evolution of a JAK2-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell 2012, 148, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Waters, J.; Leung, M.L.; Unruh, A.; Roh, W.; Shi, X.; Chen, K.; Scheet, P.; Vattathil, S.; Liang, H. Clonal evolution in breast cancer revealed by single nucleus genome sequencing. Nature 2014, 512, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, R.; Olshen, A.B.; Ladanyi, M. Integrative clustering of multiple genomic data types using a joint latent variable model with application to breast and lung cancer subtype analysis. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2906–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Mezlini, A.M.; Demir, F.; Fiume, M.; Tu, Z.; Brudno, M.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Goldenberg, A. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet, R.; Velten, B.; Arnol, D.; Dietrich, S.; Zenz, T.; Marioni, J.C.; Buettner, F.; Huber, W.; Stegle, O. Multi-Omics Factor Analysis—a framework for unsupervised integration of multi-omics data sets. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2018, 14, e8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet, R.; Arnol, D.; Bredikhin, D.; Deloro, Y.; Velten, B.; Marioni, J.C.; Stegle, O. MOFA+: A statistical framework for comprehensive integration of multi-modal single-cell data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakyawar, S.K.; Sajja, B.R.; Patel, J.C.; Guda, C. i CluF: An unsupervised iterative cluster-fusion method for patient stratification using multiomics data. Bioinform. Adv. 2024, 4, vbae015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwar, A.G.; Vembu, S.; Yung, C.K.; Jang, G.H.; Stein, L.; Morris, Q. PhyloWGS: Reconstructing subclonal composition and evolution from whole-genome sequencing of tumors. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, S.; Roth, A. PyClone-VI: Scalable inference of clonal population structures using whole genome data. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; White, B.S.; Dees, N.D.; Griffith, M.; Welch, J.S.; Griffith, O.L.; Vij, R.; Tomasson, M.H.; Graubert, T.A.; Walter, M.J.; et al. SciClone: Inferring clonal architecture and tracking the spatial and temporal patterns of tumor evolution. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satas, G.; Zaccaria, S.; Mon, G.; Raphael, B.J. SCARLET: Single-cell tumor phylogeny inference with copy-number constrained mutation losses. Cell Syst. 2020, 10, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Gong, F.; Wan, L.; Ma, L. BiTSC 2: Bayesian inference of tumor clonal tree by joint analysis of single-cell SNV and CNA data. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Bass, H.W.; Irianto, J.; Mallory, X. Integrating SNVs and CNAs on a phylogenetic tree from single-cell DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2023, 33, 2002–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Rao, M.; Shen, W.; Luo, C.; Qin, H.; Baek, J.; Zhou, X.M. Benchmarking clustering, alignment, and integration methods for spatial transcriptomics. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xie, M.; Yuan, W.; Li, Y.; Rao, M.; Liu, Y.H.; Shen, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.M. MaskGraphene: An advanced framework for interpretable joint representation for multi-slice, multi-condition spatial transcriptomics. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Schunk, C.T.; Ma, Y.; Derr, T.; Zhou, X.M. ADEPT: Autoencoder with differentially expressed genes and imputation for robust spatial transcriptomics clustering. iScience 2023, 26, 106792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; Regier, J.; Cole, M.B.; Jordan, M.I.; Yosef, N. Deep generative modeling for single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Wan, J.; Song, Q.; Wei, Z. Clustering single-cell RNA-seq data with a model-based deep learning approach. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, A.; Chang, Y.; Gong, J.; Jiang, Y.; Qi, R.; Wang, C.; Fu, H.; Ma, Q.; Xu, D. scGNN is a novel graph neural network framework for single-cell RNA-Seq analyses. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, E.; Lin, C.; Lee, S.I. Isolating salient variations of interest in single-cell data with contrastiveVI. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Shah, S.; Bar-Joseph, Z.; Pandya, R. Dhaka: Variational autoencoder for unmasking tumor heterogeneity from single cell genomic data. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Ma, M.; Yu, Z. bmVAE: A variational autoencoder method for clustering single-cell mutation data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Shi, F.; Du, F.; Cao, X.; Yu, Z. CoT: A transformer-based method for inferring tumor clonal copy number substructure from scDNA-seq data. Briefings Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, M.A.; Zaccaria, S.; Raphael, B.J. Identifying tumor clones in sparse single-cell mutation data. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, i186–i193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsulin, A.; Palowitch, J.; Perozzi, B.; Müller, E. Graph clustering with graph neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, X.F.; Edrisi, M.; Navin, N.; Nakhleh, L. Assessing the performance of methods for copy number aberration detection from single-cell DNA sequencing data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.M.; Mallory, X. SCCNAInfer: A robust and accurate tool to infer the absolute copy number on scDNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navin, N.; Krasnitz, A.; Rodgers, L.; Cook, K.; Meth, J.; Kendall, J.; Riggs, M.; Eberling, Y.; Troge, J.; Grubor, V.; et al. Inferring tumor progression from genomic heterogeneity. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Number of subclones | 2, 4 (d), 6 |

| 2 | Number of cells | 100, 500 (d), 1000 |

| 3 | Number of SNVs | 0, 1000, 5000 (d), 10000 |

| 4 | Number of CNAs | 100, 200 (d), 300 |

| 5 | False positive rate | 0.01, 0.05 (d), 0.1 |

| 6 | False negative rate | 0.55, 0.6 (d), 0.65 |

| 7 | Missing rate | 0.95, 0.98 (d), 0.99 |

| 8 | CNA noise | 0.3, 0.5 (d), 1 |

| # Cells | Model Size | Memory (Mb) | Runtime (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 41,284 | 0.16127 | 12.34 |

| 1000 | 219,484 | 0.85736 | 49.61 |

| 2000 | 417,484 | 1.59 | 147.49 |

| 5000 | 1,011,484 | 3.86 | 928.88 |

| 10,000 | 2,001,484 | 7.64 | 4455.22 |

| # Clusters | SCGclust-Silhouette | SCGclust-GT | Silhouette Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.6097 | 0.5157 | 0.1277 |

| 4 | 0.9715 | 0.9870 | 0.1578 |

| 5 | 0.5404 | 0.5404 | 0.0983 |

| 6 | 0.8859 | 0.9229 | 0.1381 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Potu, T.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chi, H.; Khan, R.; Dharani, S.; Ni, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.M.; Mallory, X. SCGclust: Single-Cell Graph Clustering Using Graph Autoencoders That Integrate SNVs and CNAs. Mathematics 2026, 14, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010046

Potu T, Hu Y, Wang J, Chi H, Khan R, Dharani S, Ni J, Zhang L, Zhou XM, Mallory X. SCGclust: Single-Cell Graph Clustering Using Graph Autoencoders That Integrate SNVs and CNAs. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010046

Chicago/Turabian StylePotu, Teja, Yunfei Hu, Judy Wang, Hongmei Chi, Rituparna Khan, Srinija Dharani, Jingchao Ni, Liting Zhang, Xin Maizie Zhou, and Xian Mallory. 2026. "SCGclust: Single-Cell Graph Clustering Using Graph Autoencoders That Integrate SNVs and CNAs" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010046

APA StylePotu, T., Hu, Y., Wang, J., Chi, H., Khan, R., Dharani, S., Ni, J., Zhang, L., Zhou, X. M., & Mallory, X. (2026). SCGclust: Single-Cell Graph Clustering Using Graph Autoencoders That Integrate SNVs and CNAs. Mathematics, 14(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010046