Abstract

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) interconnects medical devices, software applications, and healthcare services through the internet to enable the transmission and analysis of health data. IoMT facilitates seamless patient care and supports real-time clinical decision-making. The IoMT faces substantial security threats due to limited device resources, high device interconnectivity, and a lack of standardization. In this paper, we present an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) called An Empirical Distribution Ranking-Based Fuzzy J48 Classifier for Multiclass Intrusion Detection in IoMT Networks (EDR-FJ48) to distinguish between regular traffic and multiple types of security threats. The proposed IDS is built upon the J48 decision tree algorithm and is designed to detect a wide range of attacks. To ensure the protection of medical devices and patient data, the system incorporates a fuzzy IF-THEN rule inference module. In our approach, fuzzy rules are formulated based on the fuzzified values of selected features, which capture the statistical behavior of the input observations. These rules enable interpretable and transparent decision-making and are applied before the final classification step. We thoroughly evaluated our methodology through extensive simulations using three publicly available datasets, such as WUSTL-EHMS-2020, CICIoMT2024, and ECU-IoHT. The results exhibit exceptional accuracy rates of 99.68%, 98.71%, and 99.43%, respectively. A comparative analysis against state-of-the-art models in the existing literature, based on metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and time complexity, reveals that our proposed method achieves superior results. This evidence suggests that our method constitutes a robust solution for mitigating security threats in IoMT networks.

Keywords:

Internet of Medical Things; Intrusion Detection System; Empirical Distribution Ranking; fuzzy rules; decision trees MSC:

68T01; 68M18

1. Introduction

The adoption of the Internet of Things (IoT) in the healthcare sector has led to the formation of the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) [1]. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into healthcare systems has brought significant advancement in IoMT [2]. The primary breakthrough of the IoMT system is to improve the quality of life of patients, which also enables real-time health monitoring, remote patient care, and improved treatment accuracy [3]. However, the integration of various communication protocols and different healthcare devices in the IoMT is always vulnerable to various security threats and cyberattacks, allowing adversaries to exploit sensitive information [4]. Attackers often exploit Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks to leak information from the IoMT system [5]. In an MitM attack, an adversary secretly intercepts and potentially alters communication between medical devices (e.g., wearable sensors) and healthcare servers or applications. Therefore, security monitoring becomes an utmost priority in IoMT systems.

Numerous attacks, ranging from network-based and device-specific to data-centric and authentication-related, are employed to infiltrate the network and compromise the integrity of the IoMT system. Various prevention methods, such as attack detection, standards and protocol compliance, and authentication and access control, are used to protect the robustness of the network [6]. In contrast, legacy security techniques are complex and require more resources, which cannot be afforded by IoMT devices due to their resource-constrained nature, characterized by low processing power, limited storage capacity, and short battery life [2]. The IoMT devices are connected using lightweight communication protocols, and the standardization is suboptimal. Therefore, innovative protection strategies must be engineered to address the urgent safety dilemmas of IoMT infrastructures, taking into account their limited-resource design [7]. Nowadays, a wide range of innovative ideas are emerging to protect the IoMT network, which consists of firmware validation, patch management, log analysis and auditing, and intrusion detection. Intrusion detection is the most frequently implemented attack detection and reduction methodology in IoMT, leveraging nascent Machine Learning (ML) methods. ML can streamline the IDS and easily deploy and control it even in resource-constrained devices and highly dynamic networks [8,9,10].

Traditional security strategies encounter significant limitations in IoMT environments. They lack the capability to detect unknown or zero-day attacks in real-time due to their static, rule-based nature, which prevents them from adapting to evolving threats. Additionally, they struggle to scale across diverse, heterogeneous networks of medical devices commonly found in IoMT systems [11,12].

New generation IDS are specifically designed to address the limitations of conventional security mechanisms in heterogeneous and resource-constrained IoMT environments. These IDS models are increasingly leveraging lightweight machine learning, deep learning, and adaptive ensemble techniques to operate effectively across a wide range of device types, communication protocols, and data formats [13]. By minimizing memory and computation requirements, they enable real-time detection even on low-power sensors and embedded medical devices. Moreover, the integration of anomaly-based and hybrid detection techniques allows these systems to identify novel attack patterns and zero-day threats that signature-based systems often miss. The ability to learn from streaming data, adapt to dynamic network conditions, and provide interpretable security decisions marks a significant advancement in securing sensitive healthcare infrastructures against modern cyber threats [14].

To overcome the challenges faced by traditional security systems, there is a strong motivation to develop a new IDS that can adapt to the highly dynamic and heterogeneous nature of IoMT. Our work addresses the limitations of existing IDS by developing a solution capable of detecting novel threats and adapting to dynamic intrusions within the diverse IoMT landscape. This framework prioritizes real-world deployment by ensuring minimal execution time and efficient resource utilization, ultimately enhancing detection accuracy and improving security in the ever-evolving IoMT environment.

This work is an extended version of our prior conference paper [1]. In contrast to [1], this article contributes:

- We propose a novel hybrid IDS that integrates Empirical Distribution Ranking (EDR) for feature selection with a fuzzy rule-based inference system and a J48 decision tree classifier to detect and categorize various cyberattacks in IoMT environments.

- The system introduces a fuzzification mechanism that translates numerical features into linguistic variables (e.g., Low, Medium, High), enabling the extraction of interpretable fuzzy IF-THEN rules that enhance explainability and reduce classification ambiguity.

- By employing the J48 algorithm in conjunction with fuzzy logic, the proposed system maintains low computational overhead while offering human-understandable reasoning paths, crucial for trust and transparency in medical settings.

- The model is extensively validated using three benchmark IoMT datasets: WUSTL-EHMS-2020, CICIoMT2024, and ECU-IoHT. It achieves superior accuracy (up to 99.68%) and robust performance in terms of precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC analysis.

- A detailed performance comparison demonstrates that the proposed method consistently outperforms state-of-the-art IDS approaches, particularly in attack interpretability, accuracy, and scalability to resource-constrained IoMT networks.

The structure of this manuscript is as follows: Section 2 provides a review of related work, Section 3 presents our novel intrusion detection methodology for IoMT networks, Section 4 introduces the dataset, Section 5 details the experiments and performance evaluations, and Section 6 concludes with a reflection on the contributions of this research.

2. Related Work

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) refers to the interconnected network of medical devices, software, and healthcare systems that enable real-time patient monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment through data transmission over the internet. This emerging technology significantly enhances the quality of healthcare services by enabling remote care, facilitating timely interventions, and allowing for continuous monitoring. However, the IoMT ecosystem faces substantial security challenges due to the resource-constrained nature of devices, the heterogeneous communication protocols used, and the absence of standardized frameworks. These limitations make IoMT systems vulnerable to a wide range of cyber threats, including data breaches, unauthorized access, and denial-of-service attacks. Therefore, implementing robust and adaptive security mechanisms is critical to safeguarding sensitive medical data and ensuring the integrity and reliability of healthcare services.

Recent advancements in intrusion detection for the IoMT have explored a variety of machine learning and deep learning paradigms. Sohail et al. [10] proposed an explainable IDS based on ensemble boosting algorithms such as XGBoost, AdaBoost, and CatBoost, with XGBoost demonstrating superior performance due to its robustness against class imbalance and effective regularization. Feature importance analysis highlighted indicators such as the FIN flag and the ICMP protocol, although class imbalance remained a limiting factor in detecting minority attacks. Similarly, the L2D2 model introduced in [15] employed a dual-layer LSTM and dense architecture optimized via the AdamW algorithm to capture temporal dependencies in IoMT traffic. Despite outperforming conventional methods in multi-class classification, its computational demands make it impractical for binary detection on constrained devices. In [16], a hybrid UNet++–LSTM architecture was proposed to extract network traffic features, achieving 99.92% anomaly detection and 87.96% attack categorization accuracy. However, difficulties in classifying specific attacks, such as ARP spoofing and reconnaissance, highlighted the model’s sensitivity to complex intrusion patterns. Addressing dataset limitations, Dadkhah et al. [17] curated a realistic IoMT dataset comprising 40 devices and 18 diverse attack types across various protocols. Their evaluation using five ML techniques demonstrated improved generalizability, although challenges such as class imbalance, limited device scalability, and potential overfitting persist. The study in [13] explored fine-tuned Transformer models for anomaly detection under data scarcity. While these models showed promising detection accuracy, their computational complexity and memory overhead limit their applicability in real-time IoMT deployments.

In [18], the authors proposed an enhanced deep learning-based intrusion detection framework tailored for IoMT environments, combining embedded Ensemble Learning (EL) for feature selection with a One-Dimensional Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (1D-CLSTM) neural network for cyberthreat classification. To address class imbalance, a random undersampling boosting strategy was employed. Although the model demonstrated promising results, its accuracy in detecting specific attacks, such as DoS (88%) and Nmap Port Scan (81%), remained suboptimal on the ECU-IoHT dataset, indicating a need for further refinement in handling complex and stealthy threat types. Similarly, the authors in [14] proposed time-series classification models for detecting potential cyberattacks in IoHT networks by first applying a modified Neighborhood Component Analysis (NCA) for feature selection. They introduced two LSTM-based architectures, the Directed Acyclic Graph LSTM (DAG-LSTM) and the Projected Layer LSTM (PL-LSTM), and compared them against existing models, including GRU, traditional LSTM, and Bi-LSTM, using real-world IoHT traffic data. Despite demonstrating improved performance, tuning the regularization parameter and computing feature weights remains computationally intensive, suggesting that ensemble learning could be a potential enhancement.

In [19], the authors proposed a hybrid IDS that integrates Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) with deep learning techniques to detect cyberattacks in IoMT networks. The approach leverages BERT’s contextual understanding to enhance detection performance in complex medical traffic environments. However, the study highlights key limitations, including limited generalizability due to evaluation on small datasets and the model’s computational complexity, which may hinder deployment on resource-constrained IoMT devices. Kumar et al. [20] proposed a novel cyberattack detection framework for Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHT) environments that integrates Federated Learning (FL) with LSTM networks. The FL paradigm preserves patient privacy by enabling decentralized training of a global model without data sharing, while the LSTM network effectively captures temporal attack patterns in time-series data. Although the system demonstrates robustness and reduced computational complexity through embedded feature selection, the authors acknowledge the need for improvement in detecting specific attacks, such as DoS and Nmap port scans, in future iterations. Complementing these efforts, the authors in [21] introduced SECIoHTFL, a federated learning-based IDS that incorporates -differential privacy to identify cyberattacks in Internet of Healthcare Things networks securely. Their approach leverages Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to analyze network traffic while preserving user privacy. Although the system demonstrates promise, this work highlights vulnerabilities in the aggregation server to adversarial model poisoning attacks. It suggests future enhancements such as adaptive noise addition and more robust aggregation techniques to improve security and scalability.

In [22], the authors proposed a novel cyberattack detection framework tailored for healthcare systems using IoMT datasets. The integrated model combines LSTM for extracting temporal features, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) for classification, achieving high accuracy across multiple datasets. However, the combination of LSTM and PCA introduces increased computational overhead, potentially necessitating high-performance systems or cloud-based deployment solutions to ensure scalability in real-world environments. Similarly, the work done in [23] presents a comparative analysis of intrusion detection models in healthcare systems, highlighting the effectiveness of the Maximum Information Coefficient (MIC) for feature selection in capturing nonlinear relationships. However, the approach’s reliance on biometric features may raise privacy concerns, and its effectiveness may diminish on datasets lacking strong nonlinear correlations. Moreover, the study [24] proposes Light Feature Engineering based on Mean Decrease in Accuracy (LEMDA). This feature engineering method enhances IDS performance in IoT systems by improving F1 scores by 34% and reducing detection time. However, its effectiveness depends on parameter tuning and may vary in dynamic IoT environments.

In [25], the authors proposed the Memory Feedback Transformer (MF-Transformer), which integrates Memory Feedback LSTM (MF-LSTM) modules throughout the Transformer architecture to capture and propagate temporal dependencies across all layers. The model initially captures spatial-to-spatial relationships within individual time steps and subsequently fuses spatial-to-temporal dynamics through MF-LSTM’s feedback mechanism, allowing for robust tracking of both short-term anomalies and long-term trends. While the approach demonstrates superior performance in anomaly detection by preserving long-range dependencies, the integration of LSTM feedback loops throughout the Transformer increases model complexity. It may pose scalability challenges in resource-constrained IoMT environments.

In [26], the authors proposed a novel human-centric framework for cyberattack detection in IoMT environments, combining Quantum Random Forest (QRF) with local differential privacy to ensure patient data protection while enhancing detection accuracy. The framework further integrates active learning, threat intelligence feeds, and generative AI tools such as ChatGPT (GPT-5) to augment human decision-making and strengthen threat response. Although the framework demonstrates strong performance in terms of accuracy, detection rate, and resource efficiency, the use of quantum-enhanced techniques and generative tools introduces complexity. It requires advanced hardware and careful tuning for real-world deployment.

In [27], the authors introduced FedIoMT, a federated learning framework designed for the IoMT ecosystem that incorporates meta-learning and an advanced clustering strategy to enable robust model aggregation. The system employs the Kolmogorov-Arnold Convolutional Network (KANConvNet) as a local classifier, enhancing scalability, interpretability, and adaptability within the federated learning environment. Despite these strengths, the framework faces challenges related to computational efficiency on low-power devices, maintaining privacy protections, mitigating overfitting, and ensuring seamless deployment across heterogeneous IoMT infrastructures.

In [28], the authors proposed MF-CGAN, a multi-feature Conditional Generative Adversarial Network designed to generate realistic synthetic data using the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset, which includes both network traffic and health metrics. The architecture integrates conditional features, such as attack type, traffic direction, and status flags, to preserve complex interdependencies. It comprises a generator composed of dense layers and a discriminator that jointly evaluates data authenticity. While MF-CGAN enhances data diversity and realism for training intrusion detection systems, potential drawbacks include the risk of mode collapse and computational overhead associated with generating high-dimensional, feature-rich synthetic samples.

Fuzzy IF-THEN rule-based systems offer significant advantages for IDS in the IoMT environment, primarily due to their ability to handle uncertainty, vagueness, and imprecision inherent in medical and network data. These systems enable interpretable decision-making by formulating human-readable rules, making them highly suitable for critical domains like healthcare, where explainability and trust are paramount. Unlike crisp classification models that require precise thresholds, fuzzy rule-based systems offer soft boundaries for attack detection, enabling nuanced classification of ambiguous patterns commonly found in resource-constrained and heterogeneous IoMT networks.

In [29], the authors proposed a fuzzy-based self-tuning LSTM Intrusion Detection System that dynamically adjusts training epochs using early stopping, thereby improving adaptability and detection performance over conventional models. Complementing this, ref. [30] introduced a hybrid risk assessment framework that combines fuzzy logic with the Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) to evaluate and prioritize vulnerabilities in heterogeneous IoMT devices. This approach, demonstrated through a BLE attack case study, provides structured risk quantification but may be subject to the subjectivity of linguistic inputs and dependence on expert-defined parameters. To address trust and identity threats, Ref. [31] presented FTM-IoMT, a fuzzy logic-based Trust Management mechanism capable of detecting Sybil attacks by evaluating trustworthiness through integrity, receptivity, and compatibility. Despite its effectiveness in isolating malicious nodes, its reliance on static fuzzy rules may hinder responsiveness to rapidly evolving attack strategies. Furthermore, Ref. [32] proposed a Federated Learning-based Deep Neural Network (DNN-FL) anomaly detection system that preserves data privacy while ensuring robust cyberthreat identification across IoHT networks; however, this approach faces challenges such as communication overhead and handling non-IID data distributions across clients.

In [33], the authors introduced FLSec-RPL, a fuzzy logic-based intrusion detection scheme targeting DIO neighbor suppression attacks in RPL-based IoT networks. Their three-phase detection strategy, comprising activity monitoring, fuzzy logic-based identification, and malicious node validation, demonstrated superior performance across multiple metrics, including detection accuracy, F1-score, energy efficiency, and network reliability, in both static and mobile RPL scenarios. Similarly, the work done in [34] proposed a collaborative framework that integrates fuzzy logic-based feature selection with CNN-based classification, addressing challenges such as attack diversity and scalability in large-scale IoT systems. By employing network clustering and observer nodes with localized detection models that collaborate via majority voting, the system achieved remarkable detection accuracies of 99.72% and 98.36% on the NSLKDD and NSW-NB15 datasets, respectively. However, despite these advancements, existing IDS frameworks often underutilize the interpretability advantages of fuzzy inference systems, leaning instead on black-box models that entail high computational complexity and limited explainability. This gap motivates our proposed work to develop an efficient, lightweight, and interpretable IDS that combines fuzzy inference with ensemble decision-tree classifiers, notably the J48 algorithm, to address the evolving security demands of IoMT environments. Our approach aims to deliver robust, transparent, and resource-aware intrusion detection tailored to the heterogeneous and constrained nature of medical networks.

Table 1 provides a comparison of studies based on ML/DL for IoMT network attack detection and mitigation.

Table 1.

A comparative evaluation of current research trends in IDS for IoMT networks.

3. Proposed Method

This section presents the proposed Empirical Distribution Ranking-Based Fuzzy J48 Classifier for Multiclass Intrusion Detection (EDR-FJ48) in IoMT networks. The method integrates Empirical Distribution Ranking (EDR) for effective feature selection with a fuzzy rule-based inference mechanism and a J48 decision tree classifier. This hybrid approach is designed to accurately detect and classify a wide range of cyberattacks within Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) environments.

3.1. System Architecture

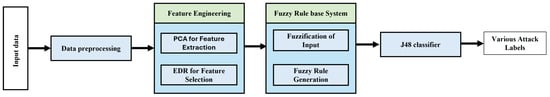

Figure 1 shows the overall system architecture of the proposed Empirical Distribution Ranking-Based Fuzzy J48 Intrusion Detection System for the IoMT. The process begins with a feature extraction stage using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which reduces the dimensionality of raw IoMT traffic data by capturing the most significant variance components. This is followed by a feature selection phase employing the EDR technique to identify the most informative and non-redundant features. The selected features are then transformed through fuzzification using Gaussian membership functions, converting numeric inputs into linguistic terms such as Low, Medium, and High. Based on these fuzzified values, fuzzy IF-THEN rules are generated to encode domain-specific knowledge and provide interpretable inference. Finally, the J48 decision tree classifier uses these fuzzy rules to perform multiclass intrusion detection. Table 2 shows the important mathematical notations used in this paper.

Figure 1.

Overall system architecture.

Table 2.

Mathematical Symbols and Notations.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

In the data preprocessing step, we remove missing values that can cause skewness in the model and convert categorical values to numerical values using a label encoder. Subsequently, we use Min-Max normalization techniques to normalize the data. This helps mitigate biases in the model. Let be a dataset with N samples, where is a d-dimensional feature vector and is the class label. For each feature dimension , Min-Max normalization is applied to scale the feature values into the range , which improves convergence.

The normalization formula is given by:

where: is the original value of the f-th feature in the i-th sample, denotes all values of the f-th feature across the dataset, and are the minimum and maximum values of the f-th feature across all samples, and is the normalized value.

3.3. Feature Engineering

After data preprocessing, a high-quality dataset is generated. However, further refinement is crucial for accurate feature selection. Feature engineering, which involves extracting relevant features from the dataset, is performed prior to training the detection models. In this work, we employ PCA for feature extraction and EDR for feature selection.

3.3.1. Feature Extraction

After normalizing the dataset , where are normalized feature vectors, We applied PCA to reduce dimensionality and extract informative features.

Let denote the normalized data matrix. PCA projects onto a lower-dimensional subspace , where , by solving the eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix:

where is the mean vector of the dataset.

Then, compute the eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors of :

The top-k eigenvectors corresponding to the largest k eigenvalues are selected to form the projection matrix . The reduced representation of each sample is then given by:

The resulting feature matrix captures the most significant variance in the data.

3.3.2. Feature Selection

Following PCA-based feature extraction, Empirical Distribution Ranking (EDR) is applied to further refine the set of informative features by assessing their discriminative ability across different classes.

Let be the PCA-transformed feature matrix. For each feature dimension , we compute the empirical probability distribution for each class :

where is the set of samples belonging to class c, and is the kernel density function estimating the empirical probability of in class c.

Then, the EDR score for feature is calculated based on the variance of the empirical distributions across all classes:

where is the mean empirical distribution of feature across all classes.

Features with higher EDR scores exhibit greater variation between class-specific distributions and are thus more informative for classification. We rank features based on their EDR scores and retain the top-m features to form the reduced feature matrix , where .

This reduced matrix is subsequently used for the fuzzification process.

3.4. Fuzzy Rule-Based System

We employed a fuzzy rule-based system to create fuzzy IF-THEN rules, which serve as input for a J48 decision tree used for detecting various attacks. The fuzzy system operates in two stages: first, the selected features undergo fuzzification; second, fuzzy rules are derived from the fuzzified data.

3.4.1. Fuzzification

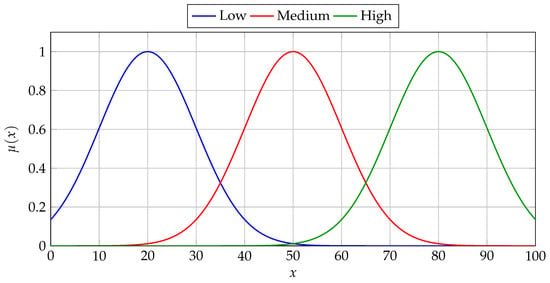

Fuzzification is the process of transforming crisp numerical input values into fuzzy linguistic variables using predefined membership functions. It is a foundational step in fuzzy inference systems, allowing real-valued data to be represented as degrees of membership in linguistic categories such as “Low,” “Medium,” or “High.” This approach is particularly beneficial when dealing with uncertain, imprecise, or noisy data, which is commonly found in IoMT environments. Fuzzification enhances interpretability and decision-making by enabling systems to reason in a way that resembles human logic. To fuzzify an input, each numerical feature is mapped to one or more fuzzy sets through membership functions, often Gaussian, triangular, or trapezoidal, which assign a degree of belonging to each fuzzy category. For instance, a feature like packet size may simultaneously belong partially to both “Medium” and “High” sets, with associated membership values guiding downstream fuzzy rule inference.

We used a Gaussian membership function [35] for fuzzification due to its smoothness, flexibility, and ability to model uncertainty effectively. Unlike triangular or trapezoidal functions, Gaussian functions provide continuous and differentiable curves, allowing for more natural and gradual transitions between fuzzy sets. This smooth behavior is especially beneficial in real-world domains, such as the IoMT, where data is often noisy and imprecise. The parameters of the Gaussian function, namely the mean (center) and standard deviation (spread), can be easily adjusted to fit the statistical distribution of feature values, many of which resemble normal distributions.

denotes the reduced dataset after applying PCA and selecting important components via EDR. Each is the value of the f-th selected PCA feature for the i-th sample. For each feature , we define three fuzzy sets: Low, Medium, and High, each with a membership function , , and .

Fuzzification Using Gaussian Membership Functions:

where:

, , and are the centers for the fuzzy sets Low, Medium, and High, respectively. , , and are the corresponding standard deviations.

The Figure 2 illustrates the process of fuzzification using Gaussian membership functions for a single feature in a fuzzy inference system. It displays three Gaussian curves representing fuzzy sets Low, Medium, and High each defined by a center () and a spread (). These functions map a crisp input value to a degree of membership between 0 and 1, enabling soft boundaries and overlapping classifications.

Figure 2.

Gaussian membership functions (Low, Medium, High) used in fuzzification of feature .

3.4.2. Fuzzy Rule Generation

Fuzzy rule generation is a crucial step in designing a fuzzy inference system. It involves formulating a set of interpretable rules that describe the relationship between input features and output classes using linguistic terms (e.g., Low, Medium, High). These rules are generated based on the combinations of fuzzified input values derived through membership functions.

Let be the fuzzified feature vector of the i-th sample. Each feature is associated with one of the three fuzzy sets: Low, Medium, or High. We defined the fuzzy rule in the standard IF-THEN form:

where are fuzzy labels for the f-th feature in the j-th rule, and is the class label associated with the rule.

The strength (firing strength) of a rule for a given fuzzified input is computed using the minimum t-norm:

where is the membership degree of the input value in fuzzy set .

The generated rules are organized within a fuzzy rule base, , which is then served as the input to the J48 decision tree.

3.5. Training the J48 Decision Tree on Fuzzified Input

The J48 decision tree in the proposed IDS framework is trained on fuzzified input features, where each numerical attribute is converted into a linguistic value such as Low, Medium, or High using Gaussian membership functions. To train the J48 tree, these linguistic values extracted from the rules serve as feature labels. The J48 algorithm calculates the Information Gain (IG) for each feature based on the entropy reduction it provides:

where T is the training set, and is the subset of samples where feature f takes the value v. The J48 algorithm constructs the decision tree by selecting features that yield the highest information gain, which is calculated based on the reduction in entropy after each split. During training, each node in the tree represents a decision based on one fuzzified feature, and branches correspond to the fuzzy labels assigned to that feature. To improve generalization and probabilistic accuracy, the decision tree is further optimized using Log Loss, allowing soft classification decisions based on class probabilities at the leaf nodes.

where, is a binary indicator function that equals 1 if sample i belongs to class c, and 0 otherwise, and is the predicted probability that sample i belongs to class c derived from normalized firing strength .

The log loss increases as the predicted probability diverges from the actual label. A perfect classifier would have a log loss of 0, while larger values indicate more uncertainty or incorrect predictions. The final predicted class is determined by selecting the rule with the maximum firing strength:

Algorithm 1 outlines the proposed EDR-FJ48 classification method designed for intrusion detection in IoMT environments. The process begins with data preprocessing, including normalization and encoding, followed by feature extraction using PCA. Next, EDR is applied to select the most discriminative features. These selected features are then fuzzified using Gaussian membership functions, generating linguistic categories such as Low, Medium, and High. Finally, a fuzzy rule base is constructed and utilized to train a J48 decision tree, thereby enhancing both classification accuracy and interpretability.

| Algorithm 1 EDR-FJ48 Intrusion Detection Algorithm |

|

4. Dataset Description

We evaluated our proposed intrusion detection system using three widely recognized IoMT datasets: WUSTL-EHMS-2020 [36], CICIoMT2024 [37], and ECU-IoHT [38]. These datasets offer comprehensive coverage of network traffic from medical devices, encompassing various attack types, which enables rigorous testing of our model’s detection and classification capabilities.

4.1. WUSTL-EHMS-2020 Dataset

The WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset is a publicly available IoMT dataset designed for intrusion detection research in healthcare environments. It was generated using a real-time Enhanced Healthcare Monitoring System (EHMS) testbed, which integrates medical sensors, a gateway, network infrastructure, and a control unit for data visualization and analysis. The dataset comprises both network traffic metrics (35 features) and patient biometric data (8 features), totaling 44 features with corresponding class labels. It contains benign and malicious traffic, capturing attacks such as spoofing, data injection, and man-in-the-middle attacks that target data confidentiality and integrity. This dataset provides a realistic testbed for evaluating cybersecurity solutions by combining sensor and network traffic data from live health monitoring scenarios. An overview of the dataset is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset.

4.2. CICIoMT2024 Dataset

The dataset was generated from an IoMT testbed comprising 40 devices (25 real and 15 simulated) operating over standard healthcare communication protocols, including Wi-Fi, MQTT, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). A total of 18 attacks were executed and categorized into five classes: DDoS, DoS, Recon, MQTT-based, and spoofing. Traffic data were collected using a network tap to duplicate packets in real time between the switch and IoMT devices, ensuring a comprehensive capture of both benign and malicious traffic. The dataset includes 45 features alongside a label column, offering a rich resource to support machine learning-based intrusion detection research in healthcare networks. A detailed summary of the dataset is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Description of CICIoMT2024 Dataset.

4.3. ECU-IoHT Dataset

The ECU-IoHT dataset was developed to address the lack of publicly available data on healthcare cyberattacks, which is often constrained by privacy concerns. Created in a controlled experimental environment, it simulates various attacks, including ARP spoofing, DoS, Nmap port scans, and Smurf attacks, to expose vulnerabilities in IoMT systems. The dataset comprises 87,754 normal instances and 23,453 attack instances, with seven network-related features (e.g., source, destination, protocol). Table 5 provides a comprehensive summary of the dataset.

Table 5.

Description of ECU IoHT dataset.

5. Experiment and Performance Evaluation

This section presents the experimental design and performance metrics employed for the evaluation. Subsequently, a detailed analysis of the results is provided, followed by a comparative analysis with existing literature to assess the efficacy of the proposed approach.

5.1. Experimental Setup

We implemented our proposed algorithm in Python (3.9.25), utilizing libraries such as NumPy, Pandas, Scikit-learn, and SciPy. Experiments were conducted on a system equipped with a 12th-generation Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12600K processor (3.69 GHz) and 48 GB of RAM, running Ubuntu 20.04.4 with Linux kernel version 5.13.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of our proposed framework, we employed standard evaluation metrics commonly used in machine learning. Specifically, we computed accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score to assess the correctness of classifying network traffic into specific categories.

The number of correctly classified instances for a given class is recorded as True Positives (TP). In contrast, the number of correctly classified instances that do not belong to that class is recorded as True Negatives (TN). Conversely, instances that were incorrectly classified are recorded as False Positives (FP) and False Negatives (FN).

5.3. Feature Engineering Results

To ensure the robustness and generalizability of the proposed EDR-based fuzzy J48 IDS, we employed a 10-fold cross-validation strategy during model evaluation. Specifically, the dataset was initially partitioned into three subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. Within the training set, k-fold cross-validation with was applied, where in each iteration, one fold was reserved as an internal validation set and the remaining folds were used to train the model. This internal cross-validation was repeated ten times, and the performance metrics were averaged to reduce the impact of data bias and overfitting.

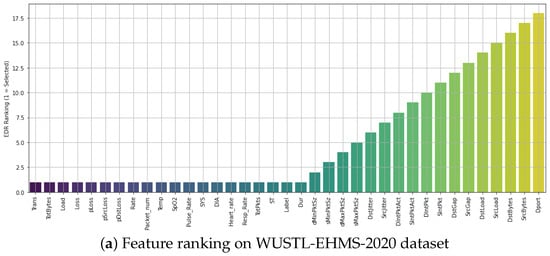

The Figure 3 presents EDR-based feature rankings across three IoMT datasets: WUSTL-EHMS-2020 (top), CICIoMT2024 (middle), and ECU-IoHT (bottom). For the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset (top), which includes 44 features (35 network and 8 biometric), the EDR analysis identified the top 20 most discriminative features, which were selected for model training. The EDR values exhibit a broad range, reflecting high inter-class variability. The CICIoMT2024 dataset (middle), containing 49 flow-based features, showed a similar EDR distribution. The top 20 features with the highest EDR scores were retained to optimize model accuracy while reducing dimensionality. The ECU-IoHT dataset (bottom) is more compact with only 7 network features. Due to the limited dimensionality, the top 3 features, Length, Protocol, and Time, were selected based on their consistently high EDR values, indicating that these few features are uniformly informative for classification.

Figure 3.

Feature rankings using EDR on three IoMT datasets: (a) WUSTL-EHMS-2020, (b) CICIoMT2024, and (c) ECU-IoHT.

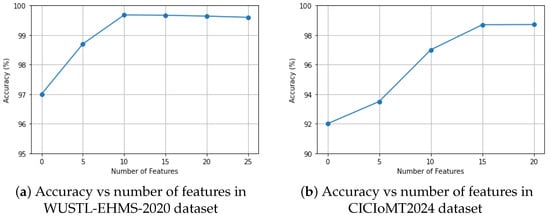

Figure 4 presents the experimental comparison of classification accuracy using varying numbers of EDR-selected features across the two IoMT datasets, such as WUSTL-EHMS-2020 and CICIoMT2024 datasets. For WUSTL-EHMS-2020, accuracy consistently improved up to 10 selected features, beyond which performance slightly declined, indicating the introduction of redundant information. Similarly, the CICIoMT2024 dataset achieved its highest accuracy with 16 features, confirming that a compact and informative subset yields optimal results. In contrast, the ECU-IoHT dataset, with only seven original features, achieved its peak accuracy using the top three features: Length, Protocol, and Time, which highlighted their discriminative strength. These respective optimal feature counts are used for all subsequent performance analysis.

Figure 4.

Accuracy vs number of features in different datasets.

5.4. Evaluation of EDR-FJ48 Performance

The proposed EDR-FJ48 method is evaluated across three benchmark IoMT datasets, such as WUSTL-EHMS-2020, CICIoMT2024, and ECU-IoHT, in comparison with several state-of-the-art approaches. The results are summarized in Table 6. On the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset, the proposed EDR-FJ48 method outperforms baseline models such as SECIoHT IDS [21], FST-LSTM [23,29], LEMDA [24] and DNN-FL [32], achieving superior accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Our method achieved an impressive classification accuracy of 99.68%, demonstrating a strong capability in accurately distinguishing between normal and attack traffic patterns. Notably, our earlier approach, EDR-J48 [1], also exhibited competitive performance on this dataset. In the case of the CICIoMT2024 and ECU-IoHT datasets, both of which include diverse attack patterns, our proposed method achieves high classification accuracies of 98.71% and 99.43%, respectively. While EDR-J48 [1] performs well in distinguishing between normal and attack patterns in binary classification settings, its effectiveness declines in multiclass scenarios. This limitation arises from the J48 decision tree’s reliance on static, axis-aligned decision boundaries, which are suitable for separating two distinct classes but struggle when multiple class regions overlap in feature space. As the number of classes increases, the likelihood of feature similarity and class overlap grows, making it challenging for J48 to generate clear and generalized decision partitions. Leveraging the fuzzy inference rule, which is well-suited for defining flexible and overlapping class boundaries, the proposed EDR-FJ48 method offers enhanced classification performance in complex, multiclass attack scenarios.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of different algorithms across datasets.

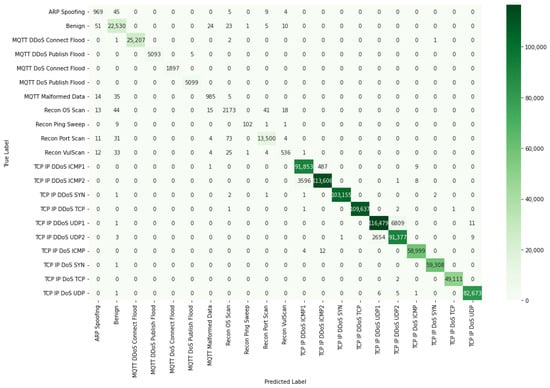

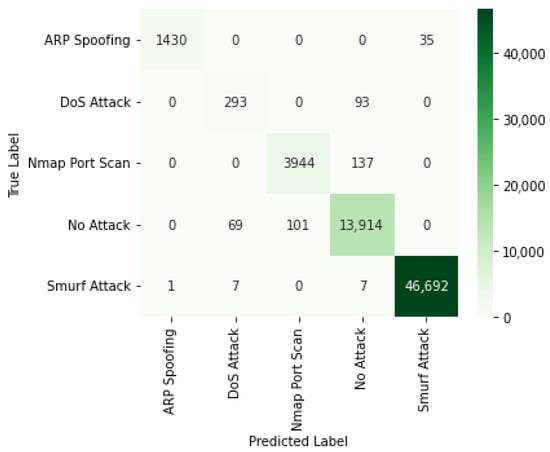

Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 present the class-wise performance metrics of the proposed EDR-FJ48 model, highlighting its consistent and high detection accuracy across all three datasets. On the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset (Table 7), the model achieves near-perfect scores for both Spoofing and Normal classes, demonstrating its strong capability in detecting normal and attack patterns. In the CICIoMT2024 dataset (Table 8), despite the challenges posed by multiple and diverse attack types, the model maintains excellent performance with precision, recall, and F1-scores exceeding 0.90 for most classes, including perfect scores for MQTT and TCP-based DDoS attacks. The ECU-IoHT dataset (Table 9) also reflects strong results, with perfect classification for Smurf Attack and No Attack classes, and only marginal decreases in performance for ARP Spoofing and Nmap Port Scan. These findings confirm the robustness and generalizability of the EDR-FJ48 model in effectively handling both simple and complex intrusion detection tasks in varied IoMT environments.

Table 7.

Class-wise performance metrics WUSTL-EHMS-2020.

Table 8.

Class-wise performance metrics CICIoMT2024.

Table 9.

Class-wise performance metrics ECU-IoHT dataset.

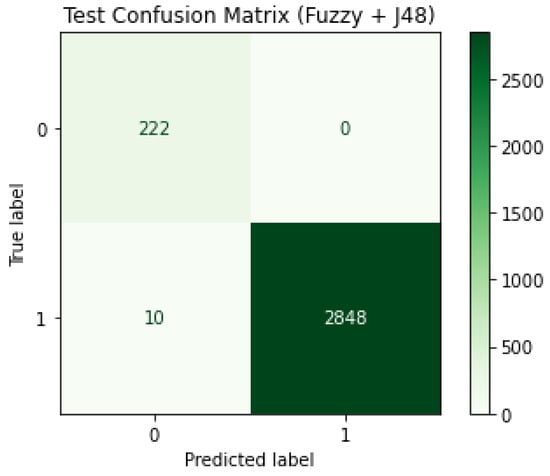

Figure 5 illustrates the confusion matrix of the proposed EDR-FJ48 model on the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset, achieving an accuracy of 99.68% with a minimal misclassification rate of 0.0014%. Figure 6 depicts the confusion matrix results on the CICIoMT2024 dataset, where the model attains a high accuracy of 98.71% and a corresponding misclassification rate of 0.0261%. Figure 7 displays the confusion matrix for the ECU-IoHT dataset, illustrating a robust classification performance with 99.43% accuracy and a low misclassification rate of 0.0174%.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix for EDR-FJ48 on WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for EDR-FJ48 on CICIoMT2024 dataset.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix for EDR-FJ48 on ECU-IoHT dataset.

The ROC curves depicted in Figure 8a–c for the WUSTL-EHMS-2020, CICIoMT2024, and ECU-IoHT datasets, respectively, demonstrate the high discriminative ability of the proposed EDR-FJ48 model across all classes. The AUC values are consistently close to 1, indicating excellent attack detection in the IoMT environment. For the binary WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset, both attack and normal traffic patterns achieve near-perfect AUCs. In the more complex multiclass scenarios of CICIoMT2024 and ECU-IoHT, the model maintains strong separability between classes, with most AUC values exceeding 0.95.

Figure 8.

AUC on the (a) WUSTL-EHMS-2020, (b) CICIoMT2024, and (c) ECU-IoHT dataset.

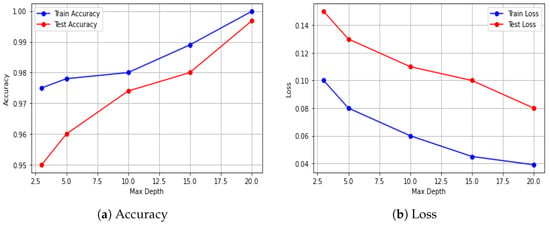

Figure 9 presents the training and testing performance of the EDR-FJ48 model on the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset as the maximum tree depth increases. In Figure 9a, both training and testing accuracies steadily rise with increasing depth. As the tree depth increases, these values rise to 0.999 for training and 0.9968 for testing at a depth of 20, indicating improved learning capability. Figure 9b shows a consistent decline in log loss for both training and testing as tree depth increases. Training loss drops from about 0.08 to 0.03, while test loss decreases from 0.15 to 0.08. The narrowing gap between training and test loss reflects strong generalization, suggesting that deeper trees enhance the model’s performance without significant overfitting.

Figure 9.

Performance evaluation of the EDR-FJ48 model on the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset: Accuracy and loss across varying maximum tree depths.

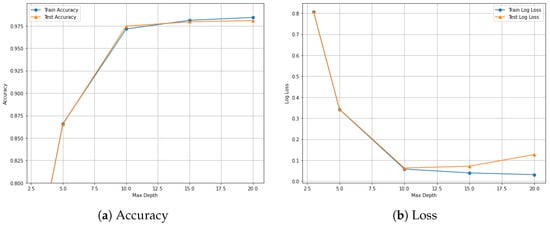

Figure 10 illustrates the training and testing accuracy and log loss of the EDR-FJ48 model on the CICIoMT2024 dataset across varying values of maximum tree depth. As shown in Figure 10a, both training and testing accuracy steadily increase with deeper trees. Initially, at a depth of 3, the training and testing accuracies are relatively low, around 0.80 and 0.82, respectively. However, as the depth increases, the accuracies rise sharply, reaching approximately 0.98 at a depth of 20, indicating significant model improvement and better pattern learning. Conversely, Figure 10b shows that the training and testing log losses decrease consistently with increasing depth. The training loss drops from approximately 0.065 to 0.01, and the test loss decreases from 0.25 to around 0.09. This declining trend confirms that the model is learning effectively, minimizing the prediction error as it grows deeper. Notably, the gap between training and test loss remains minimal, demonstrating that the model maintains good generalization performance without overfitting. The convergence of accuracy and minimization of loss affirms that the chosen depth yields strong performance on both seen and unseen data.

Figure 10.

Performance evaluation of the EDR-FJ48 model on the CICIoMT2024 dataset: Accuracy and loss across varying maximum tree depths.

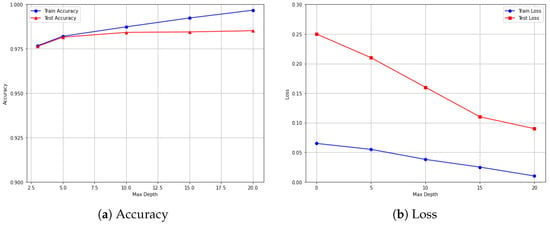

Figure 11 presents the training and testing performance of the EDR-FJ48 model on the ECU-IoHT dataset concerning varying maximum tree depths. As illustrated in Figure 11a, the model’s accuracy improves progressively with increased depth. The training accuracy climbs from approximately 0.978 at depth 3 to nearly perfect at depth 20, indicating that the model learns more complex decision boundaries as depth increases. The test accuracy also improves initially, peaking around depth 10 and then stabilizing close to 0.9943, reflecting strong generalization on unseen data. In Figure 11b, the log loss plots further validate these observations. The training loss steadily decreases from around 0.10 to below 0.02, showing the model’s increasing confidence in its predictions. Similarly, the test loss drops sharply from 0.26 to 0.11, reflecting an improvement in predictive quality. Notably, the consistently decreasing test loss, accompanied by minimal overfitting, suggests that the model generalizes well even at higher depths.

Figure 11.

Performance evaluation of the EDR-FJ48 model on the ECU-IoHT dataset: Accuracy and loss across varying maximum tree depths.

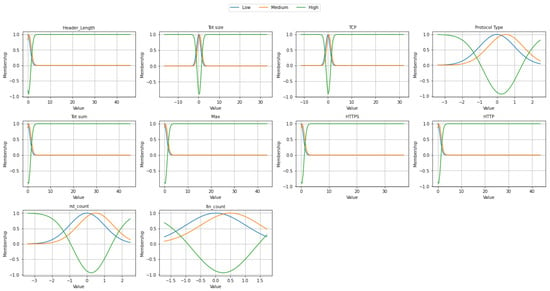

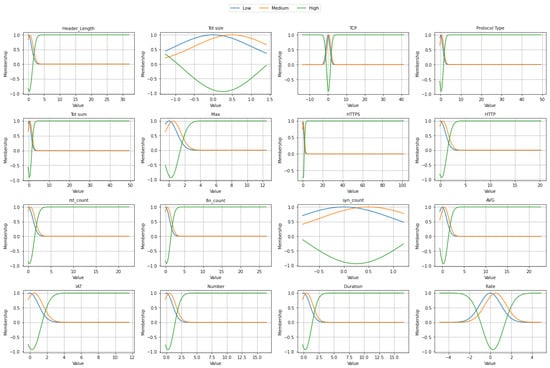

Figure 12 presents the fuzzy membership functions for selected input features of the EDR-FJ48 model on the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset. Each subplot illustrates how a specific feature is transformed into linguistic terms such as Low, Medium, and High using Gaussian membership functions. Features such as Header_Length, Tot_size, Tot_sum, and HTTP exhibit sharp transitions, indicating well-separated data distributions. In contrast, standardized features like Protocol_Type, rst_count, and fin_count span both negative and positive ranges, resulting in smoother and more overlapping transitions. This fuzzification process enables more interpretable and flexible input representations, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to handle uncertainty, establish more precise class boundaries, and generalize effectively across diverse network traffic patterns.

Figure 12.

Fuzzy membership function on WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset.

Figure 13 illustrates the fuzzy membership functions of selected features used in the EDR-FJ48 model trained on the CICIoMT2024 dataset. Each subplot represents the fuzzification of an input variable into three linguistic categories: Low, Medium, and High, using Gaussian membership functions. Features such as Header_Length, Tot_sum, HTTPS, and HTTP show sharply separated distributions, indicating a clear distinction among categories. Standardized features, such as Rate, syn_count, and Duration, exhibit smoother and more overlapping transitions, thereby enhancing the interpretability and adaptability of the fuzzy logic system. The systematic fuzzification of numerical and protocol-related features facilitates better handling of uncertainty, thereby contributing to improved detection accuracy across diverse and imbalanced traffic patterns typical of IoMT environments.

Figure 13.

Fuzzy membership function on CICIoMT2024 dataset.

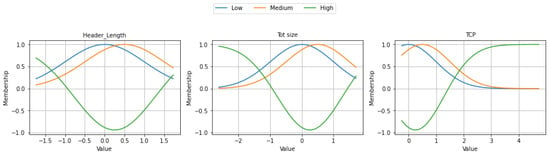

Figure 14 illustrates the fuzzy membership functions of three selected features, such as Header_Length, Tot size, and TCP, from the ECU-IoHT dataset as part of the EDR-FJ48 model. The membership curves demonstrate smooth and balanced transitions, particularly for Header_Length and Tot size, indicating standardized input scaling. The TCP feature exhibits a sharper transition from Low to High, reflecting strong feature polarity. This fuzzy representation facilitates the effective modeling of non-linear behavior and complex patterns within healthcare-related IoT traffic.

Figure 14.

Fuzzy membership function on ECU-IoHT dataset.

The ablation study investigates the contribution of each key component, such as PCA, EDR, fuzzification, and J48 classifier, by systematically disabling them and evaluating the impact on classification accuracy across three benchmark datasets. As shown in Table 10, the complete EDR-FJ48 model consistently delivers the highest accuracy, demonstrating the effectiveness of its integrated architecture. In the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset, which contains both normal and attack patterns, the model achieves an accuracy of 99.68%. The removal of the fuzzification step results in only a minor drop in accuracy, indicating that fuzzification is less critical for binary scenarios. Conversely, in multiclass datasets such as CICIoMT2024 and ECU-IoHT, fuzzification and EDR play a more influential role. Disabling EDR or fuzzification results in noticeable performance degradation, dropping from 98.73% to 77% and from 99.21% to 78.36%, respectively, highlighting their importance in effectively handling class diversity and improving discrimination in multiclass intrusion detection. These results underscore the importance of EDR and fuzzification in achieving robust performance in complex, multiclass IoMT scenarios.

Table 10.

Ablation study on different datasets and results.

Table 11 presents the execution time and memory usage of the proposed algorithm evaluated across three datasets. The results demonstrate that the algorithm maintains a low computational footprint, with execution times ranging from approximately 2.08 to 3.49 s and memory usage between 6.19 and 8.81 MiB. These lightweight resource requirements indicate its suitability for deployment on resource-constrained IoT and edge devices. This framework prioritizes real-world deployment by ensuring minimal execution time and efficient memory utilization, thereby enhancing detection accuracy and overall system responsiveness.

Table 11.

Execution time and Memory usage of EDR-J48 in different datasets.

6. Discussion

The proposed EDR-FJ48 framework combines Empirical Distribution Ranking feature selection with a fuzzy-enhanced J48 decision tree classifier to improve intrusion detection in Internet of Medical Things networks. EDR-FJ48 has several advantages, including its robustness and interpretability. The EDR method emphasizes the statistical differences in feature distributions between classes, enabling the selection of highly discriminatory attributes. This is especially useful in multiclass IoMT traffic environments where small changes in traffic behavior must be identified across multiple attack types. Furthermore, the inclusion of fuzzy logic improves the model’s ability to handle noisy traffic data, which is common in real-world IoT contexts. It delivers interpretable, rule-based conclusions that are practical for security experts. In terms of resource efficiency, experimental results show that EDR-FJ48 requires only modest memory (6–9 MiB) and execution time (2–4 s), which affirms its feasibility for deployment on constrained IoMT devices. This enables real-time detection capabilities at the network edge, minimizing dependency on cloud-based processing and accelerating threat mitigation.

However, despite these strengths, the proposed model exhibits certain limitations. It is sensitive to variations in network environments and heavily dependent on the quality and representativeness of the datasets used for training. Additionally, it may be susceptible to evolving cyber threats, as it has not been explicitly evaluated for its effectiveness in detecting zero-day or adversarial attacks, which limits its demonstrated robustness against unknown threats. The framework also involves resource-intensive training processes and faces challenges in simultaneously optimizing detection accuracy and computational efficiency, which may hinder its deployment in diverse and resource-constrained industrial scenarios. Furthermore, the current reliance on manual feature engineering, even when supported by EDR, limits the model’s adaptability to dynamic and evolving traffic patterns.

7. Conclusions

To address the security challenges of IoMT networks, this work proposes the EDR-FJ48 algorithm for accurate detection of both normal and malicious traffic patterns, enabling the identification of various attack types within IoMT environments. The proposed methodology incorporates feature engineering to reduce data redundancy and enhance feature representation. By utilizing a fuzzy membership function, the model effectively manages uncertainty, improves interpretability, and establishes clear decision boundaries. When tested on the WUSTL-EHMS-2020, CICIoMT2024, and ECU-IoHT datasets, the proposed method achieves high accuracy.

To enhance the real-world applicability of EDR-FJ48, future research should focus on expanding its generalization capabilities across a wider array of IoMT environments. This includes validating performance using more diverse, real-world datasets. Improving robustness against zero-day threats is also critical; this can be addressed through the integration of continual learning, zero-shot or few-shot learning techniques, and anomaly detection modules. In addition, exploring model compression, fuzzy rule simplification, and federated learning can optimize the framework for efficient deployment in large-scale, resource-constrained networks. Moreover, incorporating adaptive mechanisms to handle dynamic traffic and evolving threat landscapes will further improve the framework’s resilience and long-term scalability in the ever-changing IoMT ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.; methodology, J.C.; software, J.C.; validation, L.T.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, L.T.; resources, A.C. and Y.-B.K.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, L.T., A.C. and Y.-B.K.; visualization, L.T.; supervision, A.C. and Y.-B.K.; project administration, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI22C0646).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available from the following sources: (i) Washington University in St. Louis—EHMS dataset: https://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/ehms/index.html; (ii) Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity—CIC IoMT 2024 dataset: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/iomt-dataset-2024.html; and (iii) Edith Cowan University—IoHT datasets: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/datasets/48/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tileutay, L.; Chandroth, J.; Lim, K.-W.; Ko, Y.-B.; Roh, B.-H. Empirical distribution ranking based decision tree algorithm for building intrusion detection system in the Internet of Medical Things. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Annual Congress on Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT), Melbourne, Australia, 6–7 August 2024; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaj, T.A.; Abdulla, S.M.; Iderss, M.A.E.; Ali, A.A.A.; Elhaj, F.A.; Remli, M.A.; Gabralla, L.A. A survey: To govern, protect, and detect security principles on Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). IEEE Access 2022, 10, 124777–124791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hireche, R.; Mansouri, H.; Pathan, A.-S.-K. Security and privacy management in Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): A synthesis. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 640–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehabat, I.M.; Al-Hussein, N. Deploying Internet of Things in healthcare: Benefits, requirements, challenges and applications. J. Commun. 2018, 13, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, O.; Alsubhi, K.; Shaafi, A.; Gheryani, M.; Mehaoua, A.; Boutaba, R. Man-in-the-middle attack mitigation in Internet of Medical Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.B.; Stein, S.; Pilgermann, M.; Schrader, T. Attack detection for medical cyber-physical systems—A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41796–41815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, D.; Bennbaia, S.; Catak, F.O. Machine learning for the security of healthcare systems based on Internet of Things and edge computing. In Cybersecurity and Cognitive Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- Si-Ahmed, A.; Al-Garadi, M.A.; Boustia, N. Survey of machine learning based intrusion detection methods for Internet of Medical Things. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 140, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Jaimes, M.L.; Martinez-Cruz, A.; Ramírez-Gutiérrez, K.A.; Feregrino-Uribe, C. Artificial intelligence for IoMT security: A review of intrusion detection systems, attacks, datasets and Cloud–Fog–Edge architectures. Internet Things 2023, 23, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, F.; Bhatti, M.A.M.; Awais, M.; Iqtidar, A. Explainable boosting ensemble methods for intrusion detection in Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Digital Futures and Transformative Technologies (ICoDT2), Islamabad, Pakistan, 15–16 October 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.K. AI vs. traditional IDS: Comparative analysis of real-world detection capabilities. Int. J. Res. Inf. Technol. Comput. Commun. (IJRITCC) 2024, 12, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Dini, P.; Elhanashi, A.; Begni, A.; Saponara, S.; Zheng, Q.; Gasmi, K. Overview on intrusion detection systems design exploiting machine learning for networking cybersecurity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N.; Calvo, A.; Escuder, S.; Escrig, J.; Domenech, J.; Ortiz, N.; Mhiri, S. Towards enhanced IoT security: Advanced anomaly detection using transformer models. In Proceedings of the KDD 4th Workshop on Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Cybersecurity Analytics, Barcelona, Spain, 26 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Kim, C.; Son, Y.; Singh, S.K.; Kim, S. Empowering cyberattack identification in IoHT networks with neighborhood-component-based improvised long short-term memory. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 16638–16646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, G.; Sahmoud, S.; Onat, M.; Cavusoglu, Ü.; Malondo, E. L2D2: A novel LSTM model for multi-class intrusion detection systems in the era of IoMT. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 7002–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezina, A.; Nurmi, J.; Ometov, A. Novel hybrid UNet++ and LSTM model for enhanced attack detection and classification in IoMT traffic. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 57589–57603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, S.; Pinto Neto, E.C.; Ferreira, R.; Molokwu, R.C.; Sadeghi, S.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoMT2024: A benchmark dataset for multi-protocol security assessment in IoMT. Internet Things 2024, 28, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, S.K.; Kim, S. Hybrid deep learning-based cyberthreat detection and IoMT data authentication model in smart healthcare. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2025, 166, 107711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferaidi, A.; Yadav, K.; Alharbi, Y.; Alreshidi, E.J.; Alreshidi, A.; Aboshosha, B.W.; Sharma, R.; Alkhayyat, A.; Aray, D.G. A novel hybrid BERT and deep learning model network intrusion detection system for healthcare electronics. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 71, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kim, S. Securing the Internet of Health Things: Embedded federated learning-driven long short-term memory for cyberattack detection. Electronics 2024, 13, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaiyebzadeh, F.; Pouriyeh, S.; Han, M.; Liu, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, L.; Batista, D.M. Privacy-preserving federated learning-based intrusion detection system for IoHT devices. Electronics 2025, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasayreh, A.; Khalid, H.M.; Alkhateeb, H.K.; Al-Manaseer, J.; Ismail, A.; Gharaibeh, H. Automated detection of cyber attacks in healthcare systems: A novel scheme with advanced feature extraction and classification. Comput. Secur. 2025, 150, 104288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. A comparative study of cyber security intrusion detection in healthcare systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2024, 44, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghubaish, A.; Yang, Z.; Erbad, A.; Jain, R. LEMDA: A novel feature engineering method for intrusion detection in IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 13247–13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, J.A.; Wang, C.; Saifullah, M.W.U.; Sima, M.W.U.; Arshad, M.; Rathore, W.U.A. Memory feedback transformer based intrusion detection system for IoMT healthcare networks. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawawreh, M.; Hossain, M.S. A human-centered quantum machine learning framework for attack detection in IoT-based healthcare Industry 5.0. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 46065–46074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim-Ul-Islam, M.; Chakrabarty, A.; Alam, M.G.R.; Maidin, S.S. A resource-efficient federated learning framework for intrusion detection in IoMT networks. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 4508–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.; Tiwari, V.; Francis, S.A.J.; Pal, V.; Sinha Roy, D. MF-CGAN: Multifeature conditional GAN for synthetic data generation in Internet of Medical Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 13469–13476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalhareth, M.; Hong, S.-C. An adaptive intrusion detection system in the Internet of Medical Things using fuzzy-based learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 9247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritika, P.; Shanmugam, B.; Azam, S. Risk evaluation and attack detection in heterogeneous IoMT devices using hybrid fuzzy logic analytical approach. Sensors 2024, 24, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A.; Mohiuddin, I.; Din, I.U.; Almajed, H.; Guizani, N. FTM-IoMT: Fuzzy-based trust management for preventing Sybil attacks in Internet of Medical Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 4485–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaiyebzadeh, F.; Pouriyeh, S.; Parizi, R.M.; Han, M.; Batista, D.M. Intrusion detection system for IoHT devices using federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2023—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Hoboken, NJ, USA, 20 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; So-In, C.; Kongsorot, Y.; Aimtongkham, P. FLSec-RPL: A fuzzy logic-based intrusion detection scheme for securing RPL-based IoT networks against DIO neighbor suppression attacks. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Shi, L.; Fan, P. A cooperative intrusion detection system for Internet of Things using fuzzy logic and an ensemble of convolutional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.A. Using Gaussian membership functions for improving the reliability and robustness of students’ evaluation systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 7135–7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hady, A.A.; Ghubaish, A.; Salman, T.; Unal, D.; Jain, R. Intrusion detection system for healthcare systems using medical and network data: A comparison study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106576–106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, S.; Pinto Neto, E.C.; Ferreira, R.; Molokwu, R.C.; Sadeghi, S.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoMT2024: Attack vectors in healthcare devices—A multi-protocol dataset for assessing IoMT device security. Internet Things 2024, 28, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Byreddy, S.; Nutakki, A.; Sikos, L.F.; Haskell-Dowland, P. ECU-IoHT; Edith Cowan University: Joondalup, WA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.