Abstract

With the development of heavy-haul trains towards long formation and large axle load, the longitudinal impulse problem of trains is aggravated not only by improving the transport capacity of railway freight cars, but also by the braking characteristics such as the asymmetry in brake release, which has a greater impact on the longitudinal impulse of trains, seriously affecting the operation safety of trains. In this paper, a 20,000-ton heavy-haul train is taken as the research object, a train air brake system model is established by the parallel method, and the train longitudinal dynamics model is co-simulated to study the influence of braking characteristics on the longitudinal force of the train. The results indicate that the train is primarily subjected to compressive coupler forces during braking, with the maximum compressive force occurring at car 109. Compared to the maximum compressive coupler force observed under a 50 kPa reduction in brake pipe pressure, the maximum forces under 70 kPa and 100 kPa reductions increased by 16.8% and 36.8%, respectively. The controllable tail system influences the braking of middle and rear cars by supplying a braking source to the last car. When the delay time of the controllable tail system is set to 3 s, braking synchronization can be improved. Furthermore, compared to scenarios without last-car charging, the installation of a last-car charging device reduces the maximum tensile coupler force from 780 kN to 489 kN, representing a 37% decrease. The findings of this study provide theoretical insights for ensuring the safe operation of heavy-haul trains and contribute to enhancing their operational performance.

Keywords:

heavy haul train; air brake system; parallel method; longitudinal dynamics; rear car air charger MSC:

65P99

1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of the demand for bulk commodities such as coal and ore, railway transportation plays a crucial role in allocating resources across different regions. Heavy-haul railway transportation is recognized by China and the world as the most sustainable land transportation mode and the mainstream direction of the development of railway freight transport. To improve the transportation capacity, the train formation has been increased and the axle load has been raised, which puts forward higher requirements for the train’s braking system. During the braking and releasing processes of heavy-haul trains, due to the delay in the propagation of air along the train pipe, the braking and releasing of each vehicle are out of sync, resulting in huge longitudinal impact forces between carriages. As a result, freight train accidents such as coupler breakage, uncoupling, and derailment occur frequently, seriously affecting the operational safety of trains.

Research on the longitudinal dynamics of heavy-haul trains is the key to solving the above problems. By means of train tests or computer simulations, the longitudinal impulses generated during the train operation are simulated, which has wide applications in analyzing the longitudinal forces of trains and optimizing locomotive operation modes [1]. The braking characteristics such as the asynchronous braking and release of the air braking system are the key factors causing the longitudinal impulse of heavy-haul trains, and also an important part of longitudinal dynamics. The main research methods for them include theoretical analysis and simulation analysis. With advances in technology, through computer simulation, the workload and blindness of experiments can be greatly reduced, and the experimental cost can be significantly cut down. Moreover, it can conveniently simulate dangerous working conditions that are difficult to achieve in experiments. Therefore, both the simulation calculation of the air braking system and the longitudinal dynamics of heavy-haul trains have made great progress [2,3].

In the longitudinal dynamic simulation of trains, the braking characteristics of the braking system model have a significant impact on the calculation results. Wu et al. [4] summarized the development of train longitudinal dynamic simulation and classified the current air braking system models into empirical models, empirical-hydrodynamic models, and hydrodynamic models. Empirical models have the advantages of simple modeling and high simulation efficiency. Shulei Sun [5] constructed a multi-parameter mathematical simplification method for the inflation characteristics of train air brakes based on experimental data. Jiang et al. [6] established an empirical model of the air braking system based on the experimental results, conducted dynamic simulations, and verified its accuracy. The simulation speed was 70 times faster than that of the fluid model of the air braking system. Compared with empirical models, the air brake system model established based on fluid dynamics is more accurate.

With the development of computers, simulation software such as AMESim has been widely used in the field of air brake systems. Can Yang [7] and Zheng Feng [8] used AMEsim software to establish a fluid simulation model of the air braking systems of the 120 valve and the 120-1 valve. Ruizhang Yang [9] studied the working mechanism of the 120 valve. According to the pressure characteristics, components such as variable orifices were used to simulate the functions of the internal parts of the valve. By simplifying the single-valve model, the state variables of the model were reduced, and models of the air brake systems of freight cars with different marshaling units were established. Wenbo Ni et al. [10] addressed the issues of the complexity and slow simulation speed of the traditional simulation model for the EMU air brake system. They constructed a distributed simulation model for the brake system to accelerate the simulation speed. Yanbing Guo [11] established a longitudinal dynamic model of trains through the co-simulation of AMEsim and Simulink, and analyzed the longitudinal dynamic performance of freight trains on the Sichuan-Tibet line. Wei Wei et al. [12] established a simulation model of the train air-braking system and studied the influence of the locomotive air-charging capacity on the longitudinal dynamics of trains. The results show that the locomotive air-charging capacity significantly affects the release wave speed and the magnitude of the coupler force.

The train air brake system is a critical component ensuring the safe operation of trains. Its braking characteristics are not only a key factor causing longitudinal impulses in heavy-haul trains but also an important research topic in longitudinal dynamics. Murtaza and Garg [13,14] developed a dual-pipe graduated-release train air brake system model, derived its braking characteristics through simulations, and applied them to parameter studies. Pugi et al. [15] established a model library in Simulink software related to fundamental pneumatic components of the train air brake system, facilitating other researchers in constructing air brake models. Cantone et al. [16] developed an air brake valve based on fundamental pneumatic theory, achieving high consistency between simulation results and experimental data. Piechowiak [17,18] constructed an air brake system model to analyze the influence of various factors on braking performance, with simulation outcomes closely matching experimental results. Wu et al. [19] created a detailed parallel simulation model of the air brake system by designating the locomotive brake valve and boundary conditions of the train pipe considering crossover pressure losses as the master, while freight car brake valves were set as slaves, enabling real-time simulation through parallel computing. Serajian et al. [20] investigated the impact of train length on the dynamic behavior of the brake system. In the same year, Teodoro et al. [21] conducted a comparative analysis of two methods for developing real-time simulation models of the air brake system. Subsequently, Teodoro et al. [22] implemented parallel computation of two air brake system models using OpenMP and compared their performance with traditional simulation methods; the results indicated that parallel computing reduced simulation time by 80%. Alturbeh et al. [23] built a simulation model of the train air brake system in Simulink to study the effect of wheel-rail adhesion on train braking. Wu et al. reviewed the application of parallel computing in railway research. Wu et al. [12,24] summarized the development of train air brake system models, categorizing them into empirical, fluid-empirical dynamic, and fluid dynamic models, and discussed current challenges and future directions. The study also noted that commercial software such as AMESim and Simulink facilitates the construction of complex and accurate air brake system models, though increased complexity often leads to slower simulation speeds. To address this issue, Fan et al. [6] developed an empirical model of the air brake system based on experimental data, validated its accuracy, and demonstrated a simulation speed 70 times faster than that of fluid dynamic models for air brake systems.

Based on a comprehensive study of the air braking system, aiming at the problems of the complex model and difficult simulation of the air braking system of long-marshaling heavy-haul trains, this paper exploratorily proposes a method to accelerate the simulation speed. The AMEsim software (2019.2 version) is used to establish the fluid model of the train air braking system, and a co-simulation of the longitudinal dynamics of a 20,000-ton heavy-haul train is carried out. The influence of braking characteristics on the longitudinal dynamic performance of heavy-haul trains is studied, and a tail-car air-charging device is proposed to improve the longitudinal impact during the release process. The main contributions of this paper are twofold: (1) A parallel co simulation approach is adopted to establish and validate a fluid dynamic model of the air brake system for 20,000 ton heavy haul trains, which addresses the issue of low simulation efficiency—or even computational infeasibility—in modeling the pneumatic braking system of long formation heavy haul trains. (2) Using this model, the influence of braking characteristics on the longitudinal dynamic performance of the train is investigated under both braking and release conditions. A rear car air inflation device is proposed to supply compressed air to the tail of the train during brake release. Simulation results demonstrate that this device can significantly mitigate longitudinal impulse during the release process.

2. Air Braking System Model

2.1. Model Establishment

This paper takes a 20,000-ton heavy-haul train as the research object. The train formation consists of 1 HXD1 locomotive + 108 C80 freight cars + 1 HXD1 locomotive + 108 C80 freight cars + a controllable end-of-train device, with a total of 218 vehicles. The HXD1 locomotive is equipped with the DK-2 air brake, which can achieve basic functions such as independent braking, combined air-electric braking, and emergency braking. The C80 freight car is equipped with a Type 120-1 air brake, and its core component is the 120-1 air brake valve. The upper and lower parts of the main piston of the 120-1 valve are respectively connected to the train pipe and the auxiliary reservoir. According to the pressure difference between the train pipe and the auxiliary reservoir, the relative positions of the main piston rod, the cut-off valve and the slide valve are changed, so as to form the on-off of different air passages and realize different functional effects of the 120-1 valve. The modeling parameters for the 120-1 valve can be found in Table A1.

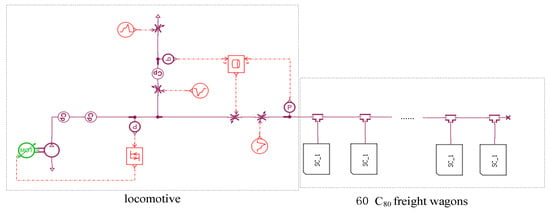

When modeling the train air braking system using traditional methods, generally, the models of the locomotive [12] and the freight car brake [8,9] are compressed into super-elements. Then, according to the actual marshaling mode, each car is connected by the train main pipe, the three-way valve, and the train branch pipe to obtain the simulation model of the train air braking system. Taking a train with a formation of 60 carriages as an example, the simulation model of the air brake system established by traditional methods is shown in Figure 1. The model includes an electro-pneumatic brake of the HXD1 locomotive and 60 120-1 valves of the C80 freight cars. As the formation of heavy-haul trains becomes longer, the model of the train air braking system becomes increasingly complex, which greatly increases the difficulty of simulation calculations. As a result, the air braking system of heavy-haul trains with longer formations cannot be simulated.

Figure 1.

Simulation model of traditional train air brake system.

To solve the problem of slow simulation speed of the traditional train air brake system model, this paper uses a parallel method to split a complete train air brake system model into multiple sub-models and assigns them to different CPUs of the computer for parallel computation. By leveraging the multi-core function of the computer, the simulation speed is improved. Compared with the complete model established by traditional methods, the number of state variables in a single sub-model established by the parallel splitting method is significantly reduced, which reduces the difficulty of simulation. Based on the TCP/IP data transmission protocol, data transfer between the split sub-models is achieved through co-simulation components. When splitting the overall train air brake system model, comprehensively consider the length of the train formation and the number of model state variables, and evenly split it into several sub-models with the same number of vehicle formations and similar numbers of state variables. Taking the air braking system model of a 60 marshaling trains established by the traditional method in the above text as an example, the train air braking system model containing 3 sub-models is established by the parallel method. Several pressure sensors and temperature sensors are added to each sub-model, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Parallel simulation model. (a) The first sub-model; (b) The second sub-model; (c) The third sub-model.

When simulating the train air braking system model established by traditional methods, when the locomotive brake applies braking or release, the air pressure change is transmitted to each freight car through the train main pipe, T-shaped tee pipe, and train branch pipe. As a result, the brake of each car responds to the pressure change in the train pipe to achieve train braking or release.

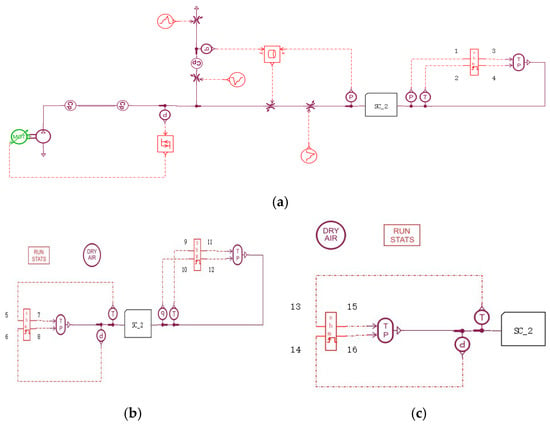

For the parallel simulation model, each sub-model is independent of each other. The changes in the train pipe pressure of each car in the sub-model need to be transmitted through the co-simulation elements. The pressure transmission process is as follows: the train pipe pressure at the end of the first sub-model → pressure sensor → port 2 of the host → port 8 of the slave → pressure conversion element → the second sub-model. In this way, the second sub-model can receive the pressure signal from the first sub-model.

Meanwhile, considering that in the train air braking system, during braking, the train pipes of the freight cars at the front near the locomotive are depressurized first, and there is a delay in the transmission of the braking wave along the train pipes. Part of the compressed air in the train pipes of the rear freight cars is transmitted forward and is discharged into the atmosphere through the train pipes of the front cars to the depressurization port of the locomotive. Therefore, an additional section of the train pipe should be added at the end of the first sub-model as the simulation boundary condition. The pressure of this section of the train pipe is consistent with the air pressure in the train pipe at the beginning of the second sub-model. At each simulation step, the simulation result of the first sub-model is transmitted to the second sub-model as its boundary condition. The simulation result of the second sub-model is not only transmitted to the third sub-model but also fed back to the first sub-model as the boundary condition for the next simulation step of the first sub-model. The simulation process is shown in Figure 3. The pressure transmission is as follows: the pressure of the second sub-model → port 6 of the slave machine → port 4 of the master machine → pressure conversion element → the first sub-model. In this way, the compressed air in the rear vehicle model can also be transmitted forward and discharged into the atmosphere through the train pipes of the front vehicles. The temperature value transmission process of the train pipe is the same as the pressure transmission process.

Figure 3.

Bidirectional transmission flow of parallel simulation data.

2.2. Model Validation

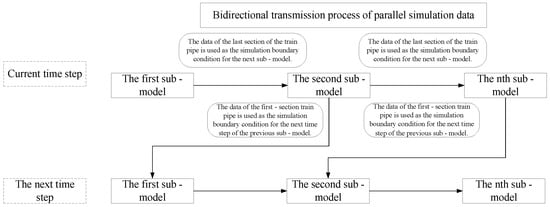

A simulation model of the air braking system for a 20,000-ton heavy-haul train with 8 sub-models was established using the parallel method. The first and fifth sub-models each contain one 8-axle double-unit HXD1 locomotive and 27 C80 freight cars. The eighth sub-model contains a controllable end-of-train device and 27 C80 freight cars, and the other sub-models each contain 27 C80 freight cars.

The constant pressure of the train pipe is set at 600 kPa, the temperature is set at 293.15 K. The lag time of the middle slave locomotive is set at 2 s, and the controllable end-of-train device controls the last car to start pressure reduction after 4 s. The train pipe pressure is reduced by 50 kPa, and the simulation results are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen from the figures that the pressure of the train pipe of Car 1 starts to decrease first, the pressure of the train pipe of Car 108 starts to decrease after 2 s, and the pressure of the train pipe of Car 216 starts to decrease after 4 s. When reaching equilibrium, the pressures of the train pipes of Car 1, Car 108, and Car 216 are stabilized at 550 kPa, and the pressures of the brake cylinders at equilibrium are 152 kPa, 155 kPa, and 158 kPa, respectively.

Figure 4.

Pressure change curve of train pipe and brake cylinder at reduced pressure of 50 kPa.

After the train pipe pressure is reduced by 50 kPa and reaches equilibrium, the simulation results of the brake cylinder pressures at each position of the train are compared with the experimental results. The experimental data were obtained from Ref. [8], where the 120-1 valve simulation model underwent an initial charging test and a brake release test in accordance with the Chinese National Railway Standard TB/T 1492-2017 [25]. The comparison results verify the accuracy of the air braking system model of the 20,000-ton heavy-haul train established by the parallel method. From the comparison data in Table 1, it can be seen that the maximum error between the simulation and the actual measurement is 16 kPa, which occurs at Car 27, and the minimum error is 0 kPa, which occurs at Car 81. Under the normal braking condition, the average values of the brake cylinder pressures in the simulation and the actual measurement are 146.2 kPa and 148.9 kPa, respectively, and the overall fluctuations are consistent. This level of error is acceptable for practical engineering applications, demonstrating that the simulation model is reliable.

Table 1.

Comparison of simulation and test results of brake cylinder after decompression of 50 kPa.

3. Longitudinal Dynamic Model

3.1. Model Establishment

A heavy-haul train is a complex nonlinear multi-particle vibration system composed of locomotives and vehicles. Taking the i-th car as the research object, the longitudinal dynamic equation is obtained through force analysis.

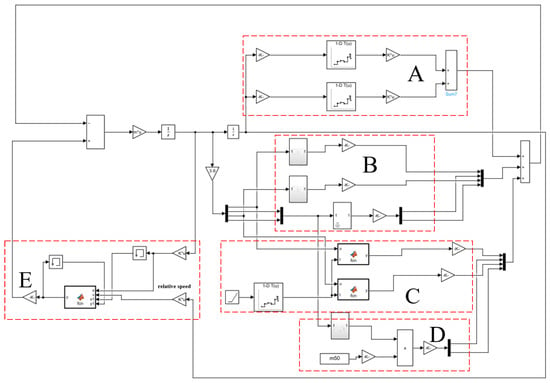

In the formula, is the mass of the i-th car, with the unit of t; are the displacement, velocity, and acceleration of the i-th car, respectively, with the units of m, m/s, m/s2; and are the traction force and electric braking force of the i-th locomotive, respectively, with the unit of kN; and are the front coupler force and rear coupler force of the i-th car, respectively, with the unit of kN; is the air braking force of the i-th car, with the unit of kN; is the running resistance of the i-th car, including basic resistance and additional resistance, with the unit of kN. This paper employs Simulink simulation software (2019 version) to establish a longitudinal dynamics simulation model. Based on the initial conditions of external forces acting on the train, this computational model calculates the acceleration of each vehicle. Through integration operations performed by the Integrator module, the velocity and displacement of each vehicle are derived. Subsequently, parameters such as running resistance, air braking force, locomotive traction force/electric braking force, and coupler force for each vehicle are determined. The acceleration of each vehicle at the next time step is then computed according to the forces acting upon it. As shown in Figure 5. The dotted-line box A represents the train additional resistance module, B represents the basic running resistance module, C represents the locomotive traction force and electric braking force module, D represents the air braking force module, and E represents the coupler force module. We employed the AMESim-Simulink interface with Simulink as the Master. The numerical integration was handled via a fixed-step (1 ms) ode4 solver in Simulink, and a variable-step BDF solver in AMESim. The co-simulation maintained a strict 1 ms communication interval using a lock-step synchronization strategy. Key tolerances in AMESim were set to 1.0 × 10−4 (relative) and 1.0 × 10−6 (absolute).

Figure 5.

Longitudinal dynamics simulation model.

Based on the speed of the running train, the basic running resistance of each locomotive and freight car is calculated, respectively. According to the line position during operation, the additional resistance of each car at each position is calculated, and finally the total running resistance is obtained. The relative speed and relative displacement of adjacent vehicles are calculated based on the speed and displacement of the train, and then the coupler force between adjacent vehicles is obtained through the coupler force calculation module. Finally, the front and rear coupler forces of each vehicle are output. The traction force and electric braking force of the locomotive are obtained through the locomotive control signals and vehicle speed. During normal braking, since the train preferentially uses electric braking force, the locomotive will generate the maximum electric braking force without generating air braking force. The brake cylinder pressure of the freight car is obtained through AMESim software, and the air braking force is obtained through calculation. The outputs of the coupler force and running resistance calculation modules are both arrays with a length of 218. The output of the locomotive traction/electric braking force module is an array with a length of 2, and the output of the air braking force module is an array with a length of 216. Then, these two arrays are merged into an array with a length of 218 through the Mux module. The resultant force acting on the train during operation is obtained by adding the three arrays together.

3.2. Model Validation

According to the basic working conditions in the international benchmark simulation test of the train longitudinal dynamics model initiated by Spiryagin et al. [26], the model in this paper is verified. The comparison between the simulation results of the model in this paper and those in Ref. [27] is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simulation data of the benchmark problem [14].

It can be seen from the data in the table that the train speed varies with the locomotive control gear and line conditions. During the entire operation process, the maximum speed of the train is between 84.99 (CARS) and 88.19 (UM) km/h, and the average speed is between 63.91 (VOCO) and 65.73 (UM) km/h. The maximum speed and average speed of the train in the simulation model of this paper are 85.36 km/h and 64.27 km/h, respectively, both of which are within the range of the data results of the nine simulators. The maximum buffing forces during the train operation in the table all occur at the 2nd car number, and the maximum values range from 549 (TABLDSS/TDEAS) to 734 (BODYSIM) kN. Except for the VOCO and BODYSIM simulators, the maximum drawbar forces of other simulators all occur at the 2nd car number, ranging from 339 (TABLDSS/TDEAS/ PoliTo) to 355 (UM) kN. The maximum buffing force and the maximum drawbar force simulated by the model in this paper both occur at the 2nd car number, with the values of 600.31 kN and 339.71 kN, respectively. The comparison results show that the train speed obtained by the simulation of the model in this paper is correct.

The efficiency analysis of the air brake system simulation model for a 30-car train formation is presented in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, for the 30-car formation, the parallel simulation model contains only half the number of state variables per sub-model compared to the conventional simulation model. In the initial charging simulation test, the parallel simulation model reduced the computation time by more than half and improved simulation efficiency by 56% compared to the conventional model. In the service braking simulation test, the parallel model saved 18 min of computational time and achieved a 72% improvement in simulation efficiency. These results demonstrate that reducing the number of model state variables contributes to reduced simulation time across different testing scenarios.

Table 3.

Simulation Efficiency Analysis.

4. Research on Longitudinal Dynamics of 20,000-Ton Heavy-Haul Trains Considering Braking Characteristics 20,000

4.1. Longitudinal Dynamic Performance Under Different Pressure Reduction Amounts

To analyze the influence of the pressure reduction in the train pipe on the longitudinal force of the heavy-haul train during braking, under the condition of a constant pressure of 600 kPa, the train pipe was depressurized by 50, 70 and 100 kPa, respectively, and the longitudinal force during the train braking process was analyzed. To ensure that the train’s complete braking processes were fully captured, the longitudinal dynamics simulation was conducted with a total duration set to 100 s.

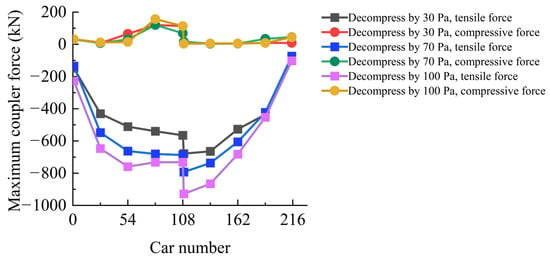

The distribution of the maximum coupler force of the train under different decompression amounts is shown in Figure 6. Table 4 shows the maximum coupler force (car number), the occurrence time under different decompression amounts of the train pipe, and the percentage increase in the maximum coupler force of the other two decompression amounts compared with that of a 50 kPa decompression. Figure 7 shows the maximum coupler force among the train under different decompression amounts.

Figure 6.

Maximum coupler force distribution along the length of the car.

Table 4.

Location and time of maximum coupler force for different decompression amounts of train pipes.

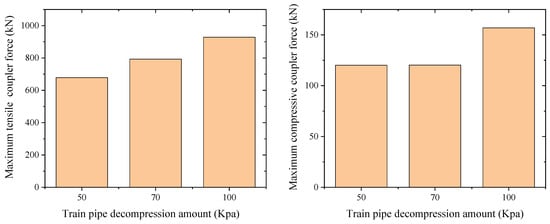

Figure 7.

Maximum coupler force under different decompression amounts of train pipes.

Combining Figure 7 and Table 4, it can be seen that the train is mainly affected by compressive coupler force during the braking process. Under different decompression amounts of the train pipe, the maximum compressive coupler force and the maximum tensile coupler force appear at car 109 and car 81, respectively. Compared with the maximum compressive coupler force of a 50 kPa decompression, the maximum compressive coupler forces of 70 kPa and 100 kPa decompressions increase by 16.8% and 36.8%, respectively. Compared with the maximum tensile coupler force of a 50 kPa decompression, the maximum tensile coupler forces of the other two decompression amounts also increase, by 0.1% and 30.6%, respectively. During the braking of the train, the front cars start to decelerate first, the relative distance between cars decreases, and the whole train is in a compressed state. Therefore, it is mainly affected by the compressive coupler force. The maximum compressive coupler force and the maximum tensile coupler force that appear during the braking process both increase with the increase in the decompression amount of the train pipe. This is because the higher the brake-cylinder pressure generated by a large decompression amount of the train pipe, the greater the air braking force applied to the wheels during the braking process, the faster the speed change in the train, and the more intense the resulting longitudinal impact.

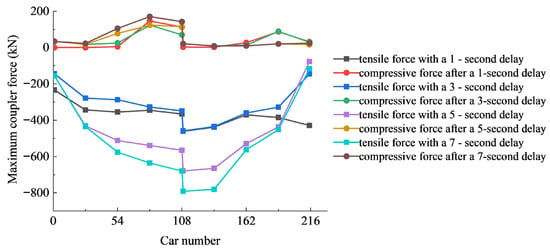

4.2. Longitudinal Dynamic Performance of Controllable End-of-Train Device Under Different Braking Time Delays

Under the condition of a constant pressure of 600 kPa, the front locomotive controls the train pipe to reduce the pressure by 50 kPa. The controllable end-of-train device starts to operate 1, 3, 5, and 7 s after the action of the front locomotive, respectively.

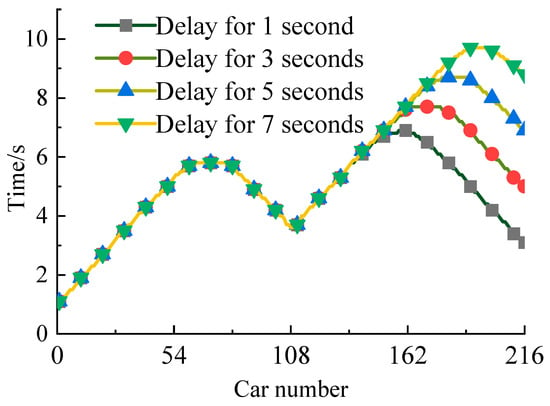

The influence of the controllable end-of-train device action delay on the starting braking time of each car is shown in Figure 8. During the train braking process, the controllable end-of-train device affects the braking of the middle and rear cars by providing a braking source for the last car. Under the condition of a 1 s action delay of the end-of-train device, the 162nd car starts braking the latest, at 6.9 s. Under the condition of a 7 s braking delay of the end-of-train device, the 193rd car starts braking the latest, at 9.7 s. The results show that as the action delay of the end-of-train device increases, the number of cars affected by the controllable end-of-train device during the braking process decreases, the latest starting braking time of the cars increases, and the car numbers are more towards the rear.

Figure 8.

Starting braking time of each car number.

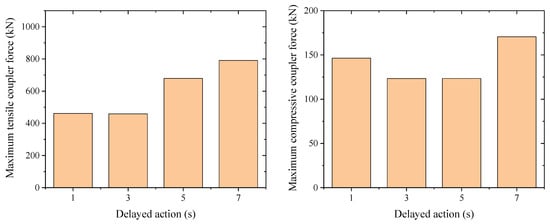

Under different action time delays of the controllable end-of-train device, Figure 9 shows the distribution of the maximum coupler force along the train length. Table 5 shows the maximum compressive coupler force (car number) and the maximum tensile coupler force (car number) under different action time delays, as well as the percentage increase in the maximum coupler force under the other three action time delays compared with the case of no action time delay. Figure 10 shows the maximum coupler force among the train under different time delay. Combining Figure 10 and Table 5, it can be seen that the maximum compressive coupler force under different action time delays is all located at car 109. Among them, the values of the maximum compressive coupler force under the working conditions of 1 s and 3 s action time delay of the end-of-train device are relatively small, both around 460 kN. The maximum tensile coupler force under different action time delays is all located at car 81. Among them, the value of the maximum tensile coupler force under the 3 s action time delay of the end-of-train device is the smallest, which is 123.3 kN. Except for the 1 s action time delay, the distribution laws of the maximum coupler force under the other three action time delays are the same. Both the maximum compressive coupler force and the maximum tensile coupler force increase with the increase in the action time delay. Since the tail cars are mainly affected by the action of the end-of-train device, when the action time delay of the end-of-train device is only 1 s, the range of cars affected by the end-of-train device increases. The tail cars brake earlier than the middle and rear cars, with a greater deceleration trend and more severe longitudinal impact.

Figure 9.

Maximum coupler force distribution along the train.

Table 5.

Maximum coupler force under different time delay.

Figure 10.

Maximum coupler force under different braking time delays.

In summary, since the compressive coupler force generated during the braking process of the train is much greater than the tensile coupler force, and the compressive coupler force increases with the increase in the action delay of the controllable end-of-train device, in order to ensure the safe operation of the 20,000-ton heavy-haul train, a smaller action delay of the controllable end-of-train device, such as 3 s, should be selected to improve the braking synchronism and thus reduce the impact force of the heavy-haul train.

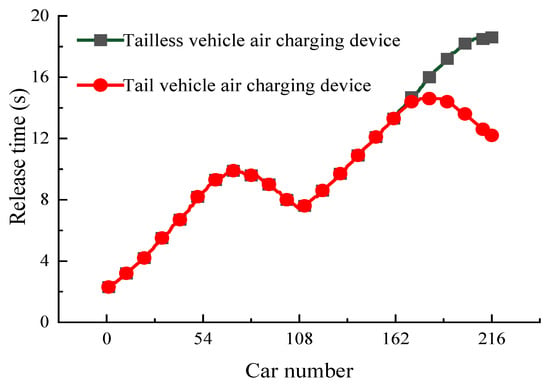

4.3. Tail Car Air Charging Device

In Section 4.2, the influence of the controllable end-of-train device on the longitudinal force of the train was investigated. During the train braking process, the controllable end-of-train device provides a braking source for the tail car, thereby improving the braking synchronization and reducing the longitudinal impact of the train. On this basis, during the train release process, if an air charging source is provided for the tail car to improve the train release synchronization, the longitudinal impact during the train release process can also be reduced.

According to the content of Reference [12], an additional locomotive with only air charging function was added to the tail car to simulate the air charging device for the tail car. During the release process, this device can provide an air charging source for the tail car and improve the longitudinal impact of the train.

The influence of the presence or absence of the tail car air charging device on the initial relief time of each car is shown in Figure 11. The tail car air charging device mainly affects the cars in the tail area, and the initial relief time of the cars in the front and middle parts of the train remains unchanged. When there is no tail car air charging device, the 216th car at the tail starts to relieve at the latest at 18.6 s. After adding the tail car air charging device, the 181st car starts to relieve at the latest at 14.6 s. The tail car air charging device improves the relief synchronization of the train by charging air to the tail cars.

Figure 11.

Release time of each car.

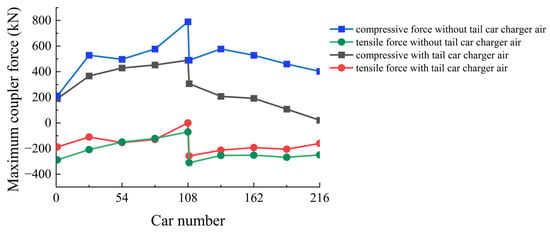

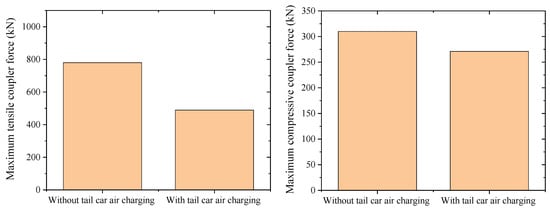

Figure 12 shows the distribution of the maximum coupler force along the train length with and without the tail car air charging device. Table 6 shows the comparison of the relief process with and without the tail car air charging device. Figure 13 shows the maximum coupler force among the train without and with tail car air charging device. Combining Figure 13 and Table 6, it can be seen that after adding the tail car air charging device, the change in the maximum compressive coupler force of the train is small; after adding the tail car air charging device, the maximum tensile coupler force of the train decreases from 780 kN to 489 kN, a reduction of 37%. This is because the train is mainly affected by the tensile coupler force during the relief process. From the simulation results, after adding the tail car air charging device, the relief synchronization of the front and rear cars is improved, the longitudinal impact is reduced, and the coupler force is decreased.

Figure 12.

Maximum coupler force distribution along the length of the car.

Table 6.

Compares the mitigation process of tailless car air charging devices.

Figure 13.

Maximum coupler force without and with tail car air charging device.

5. Conclusions

- A fluid simulation model of the air braking system for a 20,000-ton train was established using the parallel method. Based on the TCP/IP data transmission protocol, data such as pressure and temperature were bidirectionally transmitted between sub-models, which were used as boundary conditions for sub-model simulation. The accuracy of the parallel method was verified through simulation comparison.

- This study developed a longitudinal dynamic model based on fundamental theories and validated its accuracy through Simulink simulations. Subsequently, we integrated this model with a train air braking system model to formulate a comprehensive longitudinal dynamic framework for a 20,000-ton heavy-haul train that explicitly accounts for braking characteristics.

- A simulation study was conducted to investigate the effects of different brake pipe pressure reductions and braking delay times on the longitudinal dynamics of a 20,000-ton heavy-haul train. The results show that under varying levels of brake pipe pressure reduction, the maximum compressive and tensile coupler forces consistently occurred at Car 109 and Car 81, respectively. Compared to the maximum compressive coupler force under a 50 kPa pressure reduction, the values under 70 kPa and 100 kPa reductions increased by 16.8% and 36.8%, respectively. Similarly, compared to the maximum tensile coupler force under a 50 kPa reduction, the corresponding values under the other two pressure reduction levels also increased—by 0.1% and 30.6%, respectively.

- In comparison to longer activation delays of the controllable tail system, shorter delays of 1 s and 3 s resulted in smaller maximum compressive coupler forces. To ensure the safe operation of the 20,000-ton heavy-haul train, it is advisable to adopt relatively short activation delays for the controllable tail system. Doing so enhances braking synchronization and thereby reduces the longitudinal impulse forces experienced by the train.

- After equipping the rear car with an additional air-charging device, Car 181 began to release its brakes within 14.6 s at the latest—4 s earlier than when no such device was installed. This modification also led to a reduction in the maximum tensile coupler force from 780 kN to 489 kN, a decrease of 37%. These improvements significantly mitigate longitudinal impulses during the brake release phase of the heavy-haul train. The significant reduction in coupler forces can effectively and substantially lower the coupler breakage accident rate in heavy-haul trains. The cost of the rear car air inflation device is primarily reflected in its high-tech hardware, specialized installation engineering, and long-term reliability maintenance. Although the direct procurement and installation entail relatively high apparent costs, its core value lies in significantly improving the synchronization of brake release in long heavy-haul trains, effectively mitigating longitudinal impulse, and consequently preventing coupler breakage accidents while ensuring transportation safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z. and G.L.; methodology and software, S.G.; validation, Z.C. and S.H.; supervision, conceptualization and project administration, W.C.; Methodology and project administration, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open project of the National Key Laboratory for Heavy-haul, High-speed and High-power Electric Locomotives, grant number QZKFKT2023-015.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

120-1 valve Modeling Parameters.

Table A1.

120-1 valve Modeling Parameters.

| Component | Parameter | Value [7,8] |

|---|---|---|

| Main Piston Body | Mass (kg) | 0.9 |

| Piston Diameter (mm) | 110 | |

| Static Friction Force (N) | 7.5 | |

| Viscous Damping Coefficient (N·s/m) | 2500 | |

| Acceleration Damping Coefficient (N·s2/m2) | 9000 | |

| Slide Valve | Mass (kg) | 0.25 |

| Static Friction Force (N) | 65 | |

| Stabilizing Spring | Preload Force (N) | 110 |

| Stiffness (N/mm) | 5 | |

| Deceleration Spring | Preload Force (N) | 13 |

| Stiffness (N/mm) | 1.5 | |

| Partial Pressure Reduction Chamber | Volume (L) | 0.6 |

| Piston Z3 Chamber of Accelerated Release Valve | Volume (mL) | 65 |

| Orifice II | Diameter (mm) | 2.9 |

| Auxiliary Reservoir | Volume (L) | 40 |

| Accelerated Release Reservoir | Volume (L) | 11 |

| Brake Cylinder Piston | Static Friction Force (N) | 760 |

| Piston Diameter (mm) | 254 | |

| Piston Stroke (mm) | 155 | |

| Release Spring | Spring Stiffness (N/mm) | 5.33 |

| Pre-compression Force (N) | 1013 | |

| Branch Pipe between 120-1 Valve and Auxiliary Reservoir | Diameter (mm) | 25 |

| Length (m) | 1.5 | |

| Branch Pipe between 120-1 Valve and Accelerated Release Reservoir | Diameter (mm) | 25 |

| Length (m) | 0.5 | |

| Branch Pipe between 120-1 Valve and Brake Cylinder | Diameter (mm) | 25 |

| Length (m) | 2.5 |

References

- Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J. Method for building train longitudinal dynamics simulation tool based on Modelica language. Roll. Stock 2023, 61, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Cole, C.; Spiryagin, M.; Chang, C.; Wei, W.; Ursulyak, L.; Shvets, A.; Murtaza, M.A.; Mirza, I.M.; Zhelieznov, K.; et al. Freight train air brake models. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2023, 11, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Simulation Study on Influence of Brake System Characteristics on Longitudinal Dynamics Performance of Heavy-Haul Trains. Ph.D. Dissertation, Dalian Jiaotong University, Dalian, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Spiryadin, M.; Cole, C. Longitudinal train dynamics: An overview. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2016, 54, 1688–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. Research on Longitudinal Impact Dynamics of Heavy-Haul Trains. Ph.D. Dissertation, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Li, K.; Wu, H.; Luo, S. An experiment-based empirical model for heavy-haul train air brake. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2023, 15, 16878132231169618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Modeling and Simulation Research on Freight Train Brake Systems. Ph.D. Dissertation, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z. Modeling and Simulation of Heavy-Haul Freight Train Air Brake System. Ph.D. Dissertation, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R. Modeling and Simulation Study on Brake System of 120-Car Unit Freight Trains. Ph.D. Dissertation, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, W.; Huang, X.; Wang, X. Research on methods for improving simulation speed of train brake systems. Railw. Locomot. Car 2022, 42, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, C.; Ni, W. Longitudinal dynamics simulation of freight trains on Sichuan-Tibet railway descending grades based on AMEsim/Simulink co-simulation. Machinery 2022, 49, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tian, Y. Research on the influence of locomotive air charging capacity on the release performance and coupler force of heavy haul trains. Railw. Stand. Des. 2024, 68, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza, M.; Garg, S. Brake Modelling in train simulation studies. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 1989, 203, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, M.; Garg, S. Parametric study of a railway air brake system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 1992, 206, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugi, L.; Malvezzi, M.; Allotta, B.; Banchi, L.; Presciani, P. A parametric library for the simulation of a Union Internationale des Chemins de Fer (UIC) pneumatic braking system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2004, 218, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantone, L.; Crescentini, E.; Verzicco, R.; Vullo, V. A Numerical model for the analysis of unsteady train braking and releasing maneuvers. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2009, 223, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowiak, T. Pneumatic train brake simulation method. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2009, 47, 1473–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowiak, T. Verification of pneumatic railway brake models. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2010, 48, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cole, C.; Spiryagin, M.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Wei, C. Railway air brake model and parallel computing scheme. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 12, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serajian, R.; Mohammadi, S.; Nasr, A. Influence of train length on in-train longitudinal forces during brake application. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2019, 57, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, Í.P.; Ribeiro, D.F.; Botari, T.; Martins, T.S.; Santos, A.A. Fast simulation of railway pneumatic brake systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2019, 233, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, Í.P.; Eckert, J.J.; Lopes, P.F.; Martins, T.S.; Santos, A.A. Parallel simulation of railway pneumatic brake using openMP. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2020, 8, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturbeh, H.; Stow, J.; Tucker, G.; Lawton, A. Modelling and simulation of the train brake system in low adhesion conditions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2020, 234, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Spiryagin, M.; Cole, C.; McSweeney, T. Parallel computing in railway research. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2020, 8, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TB/T 1492-2017; Single Vehicle Test for Railway Vehicle Brakes. China Railway Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Spiryagin, M.; Wu, Q.; Cole, C. International benchmarking of longitudinal train dynamics simulators: Benchmarking questions. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2017, 55, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Spiryagin, M.; Cole, C.; Chang, C.; Guo, G.; Sakalo, A.; Wei, W.; Zhao, X.; Burgelman, N.; Wiersma, P. International benchmarking of longitudinal train dynamics simulators: Results. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2018, 56, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.