Abstract

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have achieved remarkable success in graph structure learning, but recent research reveals their vulnerability to carefully designed perturbations. To address this, ProGNN, a GNN model based on graph properties, was proposed to clean perturbed graphs by jointly learning robust GNNs and structural graphs. However, ProGNN’s performance is affected by the quality and distribution of input graph data, making it sensitive to specific types or distributions and underperforming with diverse data. This work introduces EProGNN, a novel GNN model incorporating an evolutionary algorithm, which jointly processes perturbed graph properties and introduces an evolutionary approach during graph structure updates. EProGNN generates diverse graph representations (individuals) through mutation functions and evaluates their quality using a fitness function, retaining high-scoring individuals for optimization and eliminating low-scoring ones. EProGNN overcomes overfitting, effectively handles perturbed graphs, and learns better graph embeddings, offering a novel method for graph structure optimization. Experiments on benchmark datasets and baselines demonstrate EProGNN’s effectiveness and the advantages of evolutionary algorithms in graph optimization. Experiments on benchmark datasets and baselines demonstrate EProGNN’s effectiveness and the advantages of evolutionary algorithms in graph optimization. For example, on the Cora dataset, EProGNN achieved a 1.48% higher accuracy than ProGNN at a 25% perturbation rate and demonstrated greater robustness against targeted attacks.

MSC:

05C85

1. Introduction

Recent research have found that GNNs [1] have achieved breakthrough performance in many popular research fields, such as social network systems [2], financial transactions [3], biomedicine [4], knowledge graphs [5] and so on [6,7,8,9]. GNN combines graph theory with deep learning and can effectively learn relevant information from structured graph data [10,11]. The core task of GNN aims to learn the representation of nodes, that is, to map each node into a low-dimensional vector space. This node representation can reflect the characteristics of the node and its role in the graph. Due to its excellent performance, GNN has also achieved remarkable success in many downstream tasks, such as relationship extraction, graph generation [12], graph classification [13], subgraph matching [14] and so on [15,16,17,18].

Although GNN has achieved remarkable performance in many fields and downstream tasks, recent research shows that GNN is easily disturbed by the perturbation graph and becomes vulnerable [19]. GNN learns the embedding representation of graph nodes through message passing in the graph. This information transfer is accomplished by iteratively updating the node representation of the graph data, with each iteration involving information about neighboring nodes. If there are perturbed nodes, the erroneous information they convey may propagate in subsequent layers, thus affecting the representation of the entire graph. Furthermore, GNN is sensitive to the neighbor nodes of any node in the graph, which means the representation of a node is directly affected by the representation of its neighbor nodes. If a node’s neighbor nodes are modified, the node’s representation may be greatly affected, resulting in increased sensitivity of the model to the input graph. In addition, GNN is also sensitive to graph structure [20], which means that changes in the topology of the graph may lead to significant changes in node representation. If the perturbation adds new edges or removes the original set of edges, the adaptability of GNN to this structural change will decrease.

To solve the above problems, many researchers have provided different solutions. Adding adversarial perturbations to GNN [21] is a common method, in which this model is trained by adding adversarial perturbations to the input graph to make the model better adapt to various inputs. This approach is typically implemented by adding an adversarial loss function to the training objective. In addition, research shows that network distillation can also improve the stability of GNN [22]. For example, in the interaction network between teachers and students, a teacher network is trained to generate soft targets, and then these soft targets are used to train the student network to enhance the generalization performance and robustness of the model. At the same time, introducing regularization terms such as dropout into GNN [23] can also improve the robustness of the model. In addition, some researchers have proven that by processing graph properties, the anti-interference ability of GNN in perturbed graphs can also be solved [24]. Projecting the graph’s adjacency matrix or node representation into a low-rank space in GNN can help the model better adapt to missing information or uncertainty, thereby increasing its resistance to perturbations. For example, by sparsifying the adjacency matrix, the model can focus more on the core structure of the graph. Introducing feature smoothing into node representation, which means averaging or pooling the features of a node by considering its neighbor nodes in the graph structure, can help mitigate the noise or perturbation of node features. By processing the perturbed graph properties, GNN can learn better graph embeddings and provide effective solutions to vulnerabilities.

Although optimizing the properties of the perturbation graph can make the model robust, studies have found that this approach can cause ProGNN to fall into overfitting problems during the training process [25]. In some downstream tasks such as connection prediction, ProGNN needs to capture complex relationships in graph-structured data, and simplification of graph properties will lead to insufficient model capacity and thus cannot fit the graph-structured training data well. Therefore, when dealing with complex downstream tasks, oversimplifying ProGNN structure will cause overfitting problems. In addition, when there is insufficient training data, ProGNN stores a lot of noise and sample information from the training set and cannot generalize to unseen data. Even after graph properties are processed, ProGNN may still overfit on small-scale training data. Crucially, ProGNN relies on alternating optimization to satisfy strict constraints (e.g., low rank and sparsity). This gradient-based approach makes the model highly sensitive to initialization and hyperparameters, often leading to convergence to local optima. Therefore, ProGNN struggles to effectively explore the global graph structure space, limiting its ability to recover the true underlying topology in the presence of significant perturbations. This limitation necessitates a method capable of global search, such as the evolutionary strategy proposed in this paper.

To address this key challenge, this paper proposed the EProGNN model. This model solves the overfitting problem by adding an evolutionary algorithm and improves the model’s robustness and generalization ability. After EProGNN processes the graph properties, it uses three different mutation functions. Each mutation function generates a new graph structure. These three new graph structures are called individuals. Therefore, EProGNN presents a certain degree of diversity in the update process of the graph structure, allowing the model to try different graph structures instead of just relying on a single structure. In other words, the diversity of graph structures that EProGNN can learn has been improved. In addition, the evaluation and elimination mechanism is the core idea of the evolutionary algorithm. EProGNN uses this mechanism to evaluate and select graph structures. Different individuals will have different adaptability scores. Individuals with high scores will be retained, while individuals with low scores will be eliminated. By selecting individuals with better adaptability, the model can learn graph representation embeddings with greater generalization capabilities. This evaluation and elimination strategy effectively prevents overfitting because it prevents the model from simply overfitting the noise in the training data. At the same time, evolutionary algorithms continuously generate, evaluate, select, and eliminate individuals in multiple iterations. Through multiple iterations, EProGNN can find better solutions in the search space of the graph structure and continuously optimize the performance of the model during the update process of the graph structure. This approach helps this model generalize better across the entire graph structure space.

To sum up, the contributions of this paper are summarized in three aspects:

- (1)

- The model proposed in this paper uses an evolutionary algorithm to learn GNN parameters from the perturbation graphs. The goal of this model aims to utilize the graph properties in the perturbed graph to learn better graph node representation embeddings through the mechanism of evolutionary algorithm. The core principle of an evolutionary algorithm is to retain the optimal graph learning embedding parameters.

- (2)

- This is the first time that a novel framework model is proposed using an evolutionary algorithm in graph structure optimization tasks based on graph properties. This model continuously evolves and selects the optimal graph structure through the mutation, evaluation and selection of evolutionary algorithm. By evolving the graph structure, the model can adapt to different graph structures during the learning process and better capture the common features between graphs, thereby improving the generalization ability on graphs.

- (3)

- Experiments and tests on multiple challenging datasets demonstrated that EProGNN achieved convincing performance. In addition, EProGNN can adjust parameters more flexibly, making the learned graph embedding more adaptable to the requirements of the task.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, related work on graph neural networks and properties of graph neural networks are introduced. In Section 3, the problem statement is introduced. In Section 4, the methodological part of the model proposed in this paper is introduced. In Section 5, the performance of the model is analyzed and evaluated through experiments. In Section 6, this paper summarizes the contributions of EProGNN and future work.

2. Related Work

According to the research focus of this paper, the following briefly introduces the related work of GNNs and research on perturbation graphs.

2.1. Graph Neural Networks

Many real-world data are presented as graphs, such as social networks, knowledge graphs, bioinformatics and so on. Unlike text and image data, the data structure of graphs represents edges through the connection relationships between nodes. In addition, graph characteristics are related to nodes and edges and can include node properties, edge properties, and global properties. However, text and images are often characterized by word embeddings or pixel values. Therefore, traditional CNN [26] and LSTM [27] network models cannot handle graph data well. Recently, the introduction of GNN has solved this problem well and has become the most effective and outstanding tool for processing graph-structured data. GNN can adaptively learn the representation of nodes, is not limited by the input feature dimension, and can better adapt to the properties and connection relationships of different nodes. At the same time, GNN can simultaneously consider the relationship between a node and its neighbors, and has strong locality and globality. GNN updates the representation of each node by aggregating information from neighboring nodes to better capture the complex relationships in the entire graph structure. Naturally, many researchers have conducted extensive research on GNN and proposed more solutions based on it. To capture structural information more easily, SeHGNN [28] pre-computes neighbor aggregation using a lightweight mean aggregator, which reduces the complexity by removing the overused neighbor attention mechanism and avoiding repeated neighbor aggregation in each training cycle. To address the problem that the predicted categories of some nodes oscillate during GNN training, GRN [29] aims to reduce the prediction variance by iteratively optimizing the predictions of unstable nodes. In the prediction phase, GRN trains a graph dense encoder to predict node categories. In the relearning phase, GRN focuses on unstable nodes to optimize predictions. GraphPrompt [30] not only unifies pre-training tasks and downstream tasks into a common task template, but also adopts learnable prompts to help downstream tasks locate the most relevant knowledge from the pre-training model in a task-specific manner. IGNet [31] first applies a multi-scale extractor to obtain shallow features and uses them as the necessary input for building a graph structure. Then, the graph interaction module constructs the extracted intermediate features into a graph structure. At the same time, the graph structures of the two branches interact for cross-modal and semantic learning to improve the performance of downstream tasks. The proposal of these improved models further improves the robustness and applicability of GNN.

Some researchers have thought and studied the properties of graphs and proposed ProGNN [32]. This model works by decomposing the adjacency matrix representation of the original graph structure input into low-rank and sparse parts. The low-rank representation captures some global structural information of the graph, while the sparse representation contains some local perturbations or noise. By decomposing the adjacency matrix into low-rank and sparse parts, the structural information of the graph can be better captured. In addition, ProGNN smoothes node features to reduce feature noise or instability. The goal of feature smoothing aims to make the representations of adjacent nodes closer in the feature space to reduce the difference between representations. This can be achieved by taking into account the representation of neighbor nodes during the node update process. This helps improve the ProGNN model’s representation learning of nodes in the graph.

Generally, graph neural networks can be divided into spectral-based methods and spatial-based methods. Spectral-based methods use the graph Laplacian operator to define graph convolution in the spectral domain, while spatial-based methods perform convolution directly on the graph by aggregating neighbor information. This paper employs a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) as the backbone encoder for the node classification task. This choice allows us to focus on optimizing the graph structure itself, which is consistent with the architecture of the baseline model ProGNN.

2.2. Research on Perturbation Graphs

Perturbed graphs refer to generating a changed graph structure by modifying or disturbing the original graph to a certain extent. If the perturbation introduces noise or destroys the structural information of the graph, it may cause the model performance to degrade [33]. For example, if key nodes or connections are removed, the model cannot properly capture the topology of the graph, affecting the accuracy of node classification or connection predictions. In recent years, researchers have conducted extensive research on how to better mitigate the negative impact of perturbation graphs on models. Some research works focus on how to design robust graph pooling operations to mitigate the effects of noise and perturbation [34]. This includes using robust graph pooling strategies, such as median pooling, to improve the model’s robustness to perturbed graphs. In addition, some researchers have proposed a normalization method based on the adjacency matrix, which improves the robustness of the GCN model to changes in the graph structure by considering implicit influence information [35]. This method shows better performance on graph structure perturbations. Self-supervised learning, meanwhile, is an unsupervised learning method in which a model is trained by solving tasks of its own creation. Research shows that self-supervised learning can help improve the model’s robustness to perturbation graphs [36]. In addition, GMNN [37] introduces the idea of Markov chain, which makes the model more robust to small changes in the graph structure by designing the transition probability on the graph. ARMA-GCN [38] combines the ideas of autoregression and sliding average, and designs an adaptive adjacency matrix smoothing strategy to alleviate the disturbance impact of the graph structure. Through adaptive smoothing operations, the ARMA-GCN model performs more robustly when processing disturbance graphs. Similarly, R-GAE [39] uses adversarial training to generate adversarial adjacency matrices and combines reconstruction error and adversarial loss for training. This method improves the model’s robustness to perturbed graphs through adversarial training, while maintaining good reconstruction capabilities for the graph structure. Naturally, GraphCL [40] utilizes contrastive learning of graphs to generate meaningful node representations and trains the model through self-supervised learning tasks. Through comparative learning, the GraphCL model can learn a more robust graph representation, which helps improve the model’s adaptability to disturbances.

3. Problem Statement

Graph data contains both features and structure. Once the structure is attacked, GNNs based on neighbor aggregation can experience a chain reaction of error propagation, leading to security vulnerabilities (such as failure in financial fraud detection). This is not just a matter of decreased model performance, but a significant security vulnerability in practical applications.

Before presenting the problem statement of the model in this paper, it is necessary to introduce some basic concepts and formula expression symbols. The Frobenius norm of the matrix M is defined as . In the same way, the norm of matrix M is . The nuclear norm of matrix M is , where represents the i-th singular value in matrix M. represents the positive value in matrix M. In the same way, represents the 0 value in the matrix M. represents the sign matrix of matrix M, where . represents the element-wise product of two or more matrices. This paper uses to calculate the trace of matrix M.

This article uses to represent a graph structure, Where is the set of all nodes N in the graph . represents the set of all edges in a graph . The set of edges between all nodes in the graph can also be expressed as an adjacency matrix . The adjacency matrix A can not only describe the connection between various nodes in the graph, but can also be used to analyze various properties of the graph. Usually the adjacency matrix represents the connection status between node and node . If there is a connection between the two, otherwise . In addition, the characteristic properties of all nodes in the graph can be represented by the characteristic matrix , Where N represents the number of nodes, and m represents the number of characteristic properties present in each node. That is, each node has its own characteristic property representation. The characteristic matrix is defined as . The feature matrix X enables the attribute information and connection relationships of each node to be disseminated and its message passed in GNN. In addition, the feature matrix X can also learn node embeddings in the feature space. Therefore, a graph can also be represented by . In the node classification task, only a part of the nodes in a graph are unlabeled nodes, while the remaining nodes are labeled nodes. In supervised learning tasks, labeled nodes are used to train the model, while unlabeled nodes are used for prediction. Assuming that there are e labeled nodes among N nodes, then the label set can be defined as . where represents the label of .

Given a graph structure and a marked node set , the goal of this model in the training phase aims to learn a function . Once is trained, it can be used for downstream tasks such as node classification. EProGNN can utilize the information of these label sets to predict the labels of unlabeled nodes. This paper uses softmax and other activation functions to output the probability distribution that each node belongs to different labels. For the labeled node set , EProGNN calculates the gap between the real label and the predicted label by using a loss function such as the cross-entropy loss function. After this process is calculated, the parameters of the model are continuously updated through the backpropagation algorithm to minimize the loss. The loss function of EProGNN is defined as follows:

where is the predicted value of graph node . where is the parameter of the EProGNN objective function . is used to calculate the difference between the learned embedding and the real label. During the EProGNN training process, selects the cross-entropy loss function.

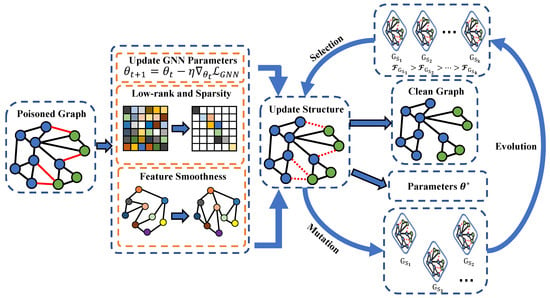

4. The Proposed Framework

The original graph is easily affected by carefully designed perturbations. This paper calls the graph structure affected by such perturbations a poisoned graph. Research has found that poisoned graphs will significantly affect the original performance of ProGNN. The main reason for this phenomenon is that the poisoned graphs may have changed the original structure of the feature matrix, causing ProGNN’s feature smoothing processing to not be implemented well. In order to effectively resist graph perturbation, this article uses an evolutionary algorithm to solve the problem that matrix processing in ProGNN cannot be performed correctly. The framework diagram of the model proposed in this article is shown in Figure 1. The black edges are the original edges of the graph and the edges marked by red lines are perturbation edges maliciously added by graph perturbation. The significance of the existence of perturbation edges aims to greatly reduce the performance of downstream tasks. After the perturbed original graphs are input, the model will sequentially perform low-rank, sparse, and feature smoothing processing. The graphs after feature smoothing will enter the mutation operation. Each processed graph will obtain a different subgraph through three different mutation functions, and each subgraph will be regarded as a new individual. The model proposed in this paper will learn different objective functions based on new model parameters. The three objective functions obtained in each round are evaluated through the fitness function. The adaptability score refers to the degree of adaptation of an individual to the environment. The higher the score, the better the adaptability of the individual to the environment. In this paper, the individual refers to the objective function, and the objective function with a high adaptability score will be retained. On the contrary, the objective function with a low fitness score will be regarded as an individual with poor quality and will be eliminated. The entire evolution process will be iterated repeatedly until all clean graphs are updated.

Figure 1.

The frame structure diagram of properties of GNNs with evolutionary algorithms.

4.1. Low Rank and Sparsity

Many real-world graphs are low-rank and sparse. For example, in a social network, there are certain rules in the connections between different users. Some users are only connected to a small number of users, but have no connection with the vast majority of users. This pattern is not special, but is common in the entire social network. In other words, graphs can be represented with less information. Some graph perturbations directly add connections at nodes where two feature properties are different. This will greatly increase the rank of the adjacency matrix, increase the noise sensitivity of the graph, and affect the performance of updating the graph structure. Low-rank and sparse processed graphs allow them to be represented in a more compact form, which reduces storage and structural complexity. Low-rank graphs can reduce the dimensionality of data while retaining the main structural features of the graph, thereby learning embedding vectors with low-rank structures. The way this paper handles low-rank and sparse graphs aims to use singular value decomposition. With a perturbed adjacency matrix , the calculation formula of its singular value is as follows:

where is all k column elements of the right singular vector matrix . In the same way, represents all k row elements of the left singular vector matrix . It should be noted that both V and are unitary matrices, that is, their elements are composed of orthonormal bases. V and U are obtained by calculating the eigenvalues of and , respectively. Because the calculation process of eigenvalues and eigenvectors is very complex, specific function libraries such as Numpy and Scipy need to be used. Here is a simple formula to use the eigenvalue equation of : , where is the eigenvalue of the left singular vector matrix , and I is the identity matrix. The formula for constructing a new adjacency matrix is as follows:

where is the new right singular vector matrix after retaining the first i singular values, and similarly is the new left singular vector matrix after retaining the first i singular values. is a new singular value matrix retaining the first i singular values. is a diagonal matrix, and the elements on the diagonal are composed of the first i singular values in descending order. The matrix M contains two regular terms, norm and nuclear norm, and both regular terms are non-differentiable. The process of finding the optimal objective function of matrix M requires optimizing these two regular terms. The model proposed in this paper first uses the gradient strategy at each step, and then uses proximal operators to deal with non-differentiable regular terms. The formula for this process is as follows:

where is the learning rate and is the proximal operator function. The specific calculation method of this function is as follows:

The calculation formulas of l1 norm and nuclear norm are as follows:

In order to simultaneously optimize the objective function containing two non-differentiable regular terms, this model uses the incremental proximal descent algorithm. By utilizing this looping method, the matrix M is updated layer by layer. The specific formula is as follows:

4.2. Feature Smoothness

Some studies have proven that the characteristics of adjacent nodes in the graph have a certain degree of similarity. Through feature smoothing, the information of neighbor nodes can be integrated into the node’s own representation. The nodes after fusing feature information have smaller feature information differences, which helps better embedding learning. In addition, the feature smoothing of neighbor nodes helps to transfer and propagate node information in the graph. When nodes in the graph lack noise or labels, feature smoothing can better help nodes adapt to the local structure of the graph. Recent research shows that graph perturbation tends to connect nodes with different characteristic property information. This perturbation method will increase the dimension of the original feature matrix and destroy the feature property information of the original nodes. The method used in the model proposed in this paper is average features. Calculate the feature mean of all neighbor nodes of each node in the feature matrix X, and then combine the feature mean with the node itself. From this, the new feature matrix after smooth feature processing is obtained. The above process is shown in the following formula:

where refers to the relationship weight between the selected node i and its neighbor node k. The relationship weight aims to further measure the importance of different neighbor nodes to the current node. Each element in the new feature matrix is the weighted average of the features in the corresponding i-th row of the original feature matrix . Such a weighted average can more finely control the influence of neighbor nodes on the current node representation to adapt to the relationship between different nodes.

4.3. Mutation

The entire evolutionary algorithm is mainly divided into three parts: mutation, evaluation, and selection. Since the selection step is relatively simple, this paper will not describe it in too much detail. This paper describes in detail the two more important parts of mutation and evaluation. The framework of the entire evolutionary algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1. The mutation step will allow the model proposed in this paper to learn three different mutation functions in order to continuously generate individuals. As mentioned above, this model performs low-rank sparse processing on the adjacency matrix, and the obtained after processing will learn the variation function to generate a new sub-matrix set . will improve the diversity of graph structure learning and increase the robustness of the model, allowing the model to adapt to different graph structures. In the process of resisting graph perturbation, this process can change the nature of the original perturbation, allowing the graph structure to learn better embedding representations. That is, the original adjacency matrix may have been learned during the mutation process and the perturbed matrix has been learned during the training process. During each iteration, each original graph undergoes the same mutation steps to generate three different individuals. The following parts introduce these three different variograms in detail.

Random Walks Mutation: Assume that an adjacency matrix is input and is waiting for mutation. represents whether there is an edge between node i and node j. Initialize a probability matrix , represents the transition probability from node i to node j. For each node i in the graph, perform a random walk process starting from i. At each step, the probability distribution of reaching neighbor nodes from the current node i is calculated through the probability matrix . Construct a transition matrix based on the recorded walking path, where represents the transition probability from node i to node j. Since the uncertainty of the transfer between nodes and the weight of the edges need to be considered, a random matrix and a probability matrix need to be added to modify the transfer matrix. This process is represented by the following formula:

where is the parameter that controls randomness, is the activation function, R is the random matrix. The random matrix R is introduced to add controlled randomness to the transition probabilities, enhancing the algorithm’s exploration capabilities while preventing overfitting to the existing graph structure. The formula for constructing a new adjacency matrix is as follows:

| Algorithm 1 Evolutionary Algorithm | |

| Input: GNNs population P, total training epochs , parameters used in the evolution process | |

| Output: evolved population | |

| 1: | Initialization: graph structures |

| 2: | Mutate population into individuals according to Equations (11), (14) and (17) |

| 3: | Evaluate various individuals according to Equation (18) |

| 4: | while individuals cannot adapt to the environment do |

| 5: | Input attacked graphs |

| 6: | Mutate population into individuals according to Equations (11), (14) and (17) |

| 7: | Evaluate various individuals according to Equation (18) |

| 8: | Select the best individual |

| 9: | end while |

| 10: | evolved population |

In the process of calculating , its directionality needs to be considered, so the transfer matrix needs to be calculated to obtain the modified transposed form. The first matrix after the mutation operation can be obtained through the random walk method.

Betweenness Centrality Mutation: Betweenness centrality mutation generates a new matrix by calculating the influence of node i on other nodes j in the same graph structure. First, the betweenness centrality of a node is calculated, which is based on the number of shortest paths between the node and other nodes. The calculation formula of betweenness centrality is as follows:

where is the number of shortest paths from node s to node t in the adjacency matrix . is the number of paths passing through node v in the shortest path. The purpose of the restriction of the inequality sign aims to ensure that node v is neither node s nor t. Next, the betweenness centrality needs to be normalized. Assume that among N nodes, all nodes are directly connected to all other nodes. The calculation formula of normalized betweenness centrality is as follows:

Through normalization processing, the value of is limited to . This makes it easier to compare the betweenness centrality values of different networks. This can more clearly determine which nodes in the graph play a more important connecting role in the shortest paths to other nodes. Finally, the matrix weight needs to be set, and the node update is determined through the threshold . The weight calculation formula is as follows:

The range of is , and the specific numerical selection of this value in different downstream tasks is also different. The original matrix can be updated through the threshold , and finally is obtained.

Stochastic Block Mutation: Random block mutation is a method that uses a probabilistic graph model to reconstruct the connection relationship between pairs of adjacency matrix nodes. The nodes in the original graph will be divided into several different blocks using community detection algorithms, which group nodes based on their connection density. Nodes within each block are connected with a certain probability, while the connection probabilities between different blocks may be different. Random block mutation is divided into two steps: defining probability parameters and generating adjacency matrices. Assume that there are K node blocks, represents the number of nodes in each node block. The calculation of the connection probability matrix and the probability matrix within the node block is as follows:

where represents the number of connections between nodes in node block k and nodes in node block l. represents the number of node connections in node block k. For the new adjacency matrix , the existence of edges can be judged through the following probability distribution:

Through the above formula, we can get the probability of an edge between any two nodes i and j in , and then update the adjacency matrix. The advantage of using the connection probability matrix and the node intra-block probability matrix , respectively, is that the generated graph conforms to a predetermined probability distribution in the connection patterns between blocks and within blocks.

4.4. Evaluation

In the entire process of processing graph data by the model proposed in this paper, the evaluation section aims to evaluate the quality of different individuals through the fitness function. Only individuals with high fitness scores will be considered to be of high quality and thus selected and retained. After inputting a perturbation graph, this model will first perform low-rank feature smoothing processing, and then perform mutation operations. However, this two-stage approach may result in suboptimal performance of the GNN model on a given downstream task. Therefore, this paper proposes a new joint learning method to learn better GNN parameters. Therefore the fitness function F in the evaluation section is as follows:

The fitness function consists of four key components: (1) a reconstruction error term that ensures the processed graph maintains similarity with the original structure, (2) a nuclear norm term that promotes low-rank properties and captures essential graph features, (3) an L1 regularization term that maintains graph sparsity, and (4) a task-specific loss term that measures the performance of the GNN model on downstream tasks. These components work together to balance structure preservation, feature extraction, and task performance.

Where is a predefined hyperparameter that controls the GNN model loss function. Since adversarial attacks will maximize , preprocessing functions such as low-rank sparse are needed to optimize the objective function. In the training stage, graph structures with higher accuracy in downstream tasks such as node classification will get higher . The graph structure with high indicates that it will have better classification performance, and the graph structure will be regarded as the optimal individual and thus retained. On the contrary, graph structures with low will be regarded as low-quality individuals and then eliminated.

4.5. Overview of EProGNN

Existing methods (such as ProGNN) are typically based on gradient-based optimization, which can easily get stuck in local optima. EProGNN’s innovation lies in introducing population-based search, utilizing evolutionary mechanisms to explore a wider range of graph structures.

After introducing the detailed steps of each part of EProGNN, Algorithm 2 presents the entire EProGNN training process. In line 1, the adjacency matrix, feature matrix and parameters of the perturbation graph input to EProGNN are first initialized. In lines 3 to 5, EProGNN will perform low-rank sparse and feature smoothing processing on the adjacency matrix and feature matrix, respectively. In line 7, the classifier of EProGNN is trained. In line 9, the graph structure after attribute processing will generate different new graph structures based on three different mutation functions. These new graph structures are called individuals. In line 10, different individuals are evaluated for individual quality by the fitness function. In lines 13 to 14, EProGNN will sort according to the fitness score, and finally filter out the individuals with the highest score in each epoch. Through this mechanism of evolutionary algorithm, EProGNN can find an optimal graph structure in each iterative training for subsequent downstream task training.

4.6. Complexity Analysis

This section provides a detailed analysis of the time complexity of EProGNN and the baseline ProGNN. First, let represent the number of nodes, represent the number of edges, d represent the feature dimension, and L represent the number of GNN layers. The time complexity of ProGNN mainly depends on the singular value decomposition (SVD) required for the low-rank constraints, which is approximately in the worst case and in most cases. This makes ProGNN computationally expensive when processing large graph data. For EProGNN, its time complexity is determined by the evolutionary process. Let G be the number of model iterations and P be the population size. Its cost mainly consists of two parts: (1) fitness evaluation (GCN training) and (2) mutation operations. The complexity of one GCN training iteration is . Therefore, the total time complexity of EProGNN is approximately . Although introducing a population size P increases the total computational cost compared to training a single model, this cost is justified for two reasons:

- Parallelism: Unlike the gradient-based sequential updates in traditional ProGNN, the fitness evaluation of individuals in EProGNN is independent. Therefore, the complexity caused by the factor P can be effectively offset by parallel computation across multiple GPUs.

- Performance trade-offs: The additional computational overhead enables EProGNN to overcome the limitations of traditional ProGNN gradient descent, thereby escaping local optima and achieving greater robustness against targeted attacks, a primary goal for security-critical applications.

| Algorithm 2 Properties GNNs with Evolutionary Algorithm | |

| Input: Adjacency matrix of perturbation graph A, Attribute matrix of perturbation graph X, Label set of the perturbation graph, Hyperparameters , , , , Probability matrix . | |

| Output: EProGNN model parameters sets . | |

| 1: | Initialization: initialize basic perturbation graphs , initialize basic perturbation attribute matrices , initialize model parameters ; |

| 2: | while Stopping condition is not met do |

| 3: | % Perform low-rank, sparse and feature smoothing processing on the perturbation graphs |

| 4: | Low-rank and sparsify the input adjacency matrix according to Equations (3) and (8); |

| 5: | Smooth the input feature matrix features according to Equation (9); |

| 6: | for to i do |

| 7: | % Training model classifier |

| 8: | for to do |

| 9: | The graphs after attribute processing are mutated through Equations (11), (14) and (17); |

| 10: | Different individuals perform quality evaluation through Equation (18); |

| 11: | end for |

| 12: | end for |

| 13: | ; |

| 14: | |

| 15: | end while |

| 16: | return |

5. Experiments

In this section, this paper evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility of EProGNN against complex graph adversarial attacks. This section discusses the performance capabilities of EProGNN under different modes of adversarial attacks and a large amount of advanced experimental data through a large number of convincing experimental data. In addition, the performance changes of EProGNN under different attribute modes are further discussed. Before presenting the experimental results and comparative analysis in this paper, this paper first introduces the experimental setup.

5.1. Experimental Settings

5.1.1. Datasets

To evaluate the effectiveness of EProGNN, we conducted experiments on five benchmark datasets, including two social networks and three citation networks. The detailed statistics of these datasets are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistics of the five benchmark datasets used in the experiments.

- Social Networks: We utilize BlogCatalog [41] and Orkut [42]. BlogCatalog represents social relationships among bloggers, where node labels denote user interests derived from metadata. Orkut is a large-scale social network dataset where edges indicate friendships between users and groups.

- Citation Networks: We employ three standard citation graphs: Cora [43], Citeseer [44], and Pubmed [45]. In these graphs, nodes represent scientific publications, and edges denote citation links. For Cora and Citeseer, node features are binary word vectors indicating the presence of specific words. Pubmed involves diabetes-related publications, utilizing TF-IDF weighted word vectors as node features.

5.1.2. Baselines

In order to analyze the effectiveness and feasibility of EProGNN, this paper uses the adversarial attack repository DeepRobust [46] to compare and analyze it with the most representative and convincing GNN model and defense model, respectively. The relevant information of the baseline model used in this experiment is as follows:

- (1)

- GCN [47] is a method for learning and representing sets of vertices and edges in GNNs, which truly implements the mapping from words to graphs. Image inputs are successfully used as latent image outputs through node embedding and random walk strategies.

- (2)

- GAT processes graph-structured data. It aggregates neighbor nodes through the attention mechanism, realizes adaptive allocation of weights for different neighbors, and greatly improves the expressiveness of GNNs.

- (3)

- GraphSAGE is a popular graph neural network architecture for inductive node embeddings. The model exploits node features (e.g., text attributes, node configuration information, node degree) to learn an embedding function that generalizes to unseen nodes. By adding node features into the learning algorithm, the model simultaneously learns the topology structure of each node neighborhood and the distribution of node features in the neighborhood.

- (4)

- ProGNN is a model that can learn graph structure and GNN parameters at the same time. The goal of this model aims to defend against the most common adversarial attack setting on graph data, namely poisoning adversarial attacks on graph structures. In this setting, modifying the edges before training the GNN already disturbs the graph structure, while the node features of the model itself are not changed.

5.1.3. Parameter Settings

In this experiment, a small number of walk nodes are randomly selected for training on the input graph dataset. In this experiment, the number of nodes used for verification is consistent with the number of nodes used for training. The remaining nodes in each round of experiments are used for staged testing of the experiment. The data results of each experiment are analyzed and compared based on the completion of 50 iterations of training. For the input dimension of each layer of the GCN model, a series of parameter settings, such as the number of nodes, are all experimented with according to the scheme provided by the original author. In the verification experiment of the GAT model, under the premise of following the standard experiment mentioned by the original author, the preset values of the structure and loss or evaluation function are set to and , respectively. Conducting the experimental verification of GraphSAGE, this experiment sets of the nodes as training and of the nodes as unsupervised training for sufficient experiments. For the experimental verification part of RGCN, this experiment sets the range of the number of hidden nodes and non-hidden nodes from and respectively. For the GCN additional algorithm experiment part, this experiment sets the equivalent edge set threshold range and perturbation graph value range according to the relevant literature. The value range of the former is set to , and the value range of the latter is set to . Since the main task of this paper is node classification, and the samples in each category are relatively balanced, accuracy (%) is used as the main evaluation metric to measure the model’s resilience against adversarial attacks.

5.2. Defense Performance

In the experimental part of this paper, we prove the excellent performance of EProGNN in node classification from multiple perspectives. ‘-’ in Table 2 shows that insufficient memory is available for experimental comparison. The following three aspects will be elaborated next:

Table 2.

Node classification performance (accuracy (%)) under non-targeted perturbation. The bolded text in the table indicates the optimal experimental results.

- Targeted Perturbation: The scheme aims to conduct a targeted single edge set perturbation on a specific node on the canonical graph structure in order to deceive the graph model on the original target node. This paper uses two targeted perturbation methods, poisoning perturbation and evasion perturbation, and this is currently the most advanced purposeful perturbation on graph structure model data. Under this perturbation scheme, the attacker may not be able to directly modify the target node, and may only be able to access some nodes other than the target node or access incomplete data. In doing so, the experimenter can clearly distinguish between the perturbation node and the target node.

- Targetless Indiscriminate Perturbation: This perturbation scheme is different from the former one. The indiscriminate perturbation is an attempt to reduce the overall performance of the experimental model on the entire graph so as to examine the ability of the model to resist comprehensive perturbations. Under the indiscriminate perturbation, the attacker tries to reduce the generalization ability of the model and reduce the performance on unlabeled nodes. The core idea of this perturbation scheme aims to use the adjacency matrix of the experimental graph structure as a hyperparameter. It is worth noting that the objective function of the total scheme is a bi-level problem, and each element in the adjacency matrix of the graph can only be 0 or 1, so this is also a discrete optimization problem.

- Randomization Perturbation: This perturbation scheme is different from the previous two. After the randomization perturbation selects a fixed perturbation graph, it is assumed that the selected graph structure is empty, and then the graph structure to be tested is randomly selected and randomly assigned. In other words, the perturbation scheme deletes random edges in any clean graph structure and fills in wrong edge sets. This kind of wrong filling can be completely regarded as a source of poisoning noise to some extent, and several such sources of poisoning noise will be added to each graph structure. According to the experimental data, the perturbation scheme is quite convincing and provable.

This paper first used various different kinds of perturbation methods to make canonical graphs under perturbation. This paper used the five most representative datasets to train EProGNN and various convincing baseline models on the graph models affected by the perturbation and analyzed the node classification performance obtained under these methods and datasets in detail.

5.2.1. Against with Targetless Indiscriminate Perturbation

This paper first used the canonical graph structure under different modes to conduct different degrees of benchmark experiments against non-target perturbations through different models and datasets. The perturbation method of perturbation aims to use the meta-gradient. This perturbation method directly regards the graph structure matrix under different paradigms as non-fixed hyperparameters, and then follows the special pattern of the graph structure to derive. This paper randomly uses a NIPA method to directly inject a large number of simulated nodes into the graph structure of different modes. In order to make the disturbance more invisible, this paper implements a non-targeted graph-level perturbation. This perturbation method aims to directly replan the edges on the graph instead of directly deleting or reducing edges, so that the disturbance is more invisible. For example, there are three nodes , and , researchers can remove the connection between and , and add a connection between and . In this case, the number of nodes on the graph is not modified, nor is the number of edges. Therefore, there are multiple ways of perturbation under this module. For Citeseer, Polblogs and Cora datasets, this paper used the Meta-self perturbation method. This perturbation method is two-stage. First, the training model parameters are used to enable the model to learn common parameters in different tasks, and then the fine-tuning stage is used to fine-tune downstream tasks. For the two datasets of Pubmed and Orkut, this paper used the more time-saving A-Meta-Self method for experiments. Specifically, the method designs a meta-self-paced training model consisting of graphical model training patterns to fit the weighting function. This method takes the similarity scores of edge sets as input, and outputs the experimental change perturbation rate. In other words, this paper changes the proportion of the attacking edge from 0% to 25%, and the step size of each increase is 5%. According to the above expression, the experiments in each section of this paper were carried out 20 times, and then the experimental data were analyzed and compared, and the accuracy table of the experiment is reported in Table 2. In the accuracy table, the best data for each individual experimental subsection are indicated by bold annotations in this paper. The following is a full discussion and analysis of the experimental data in the table.

Through the experimental accuracy table in this paper, it can be clearly concluded that under different perturbation rates and multiple rounds of tests on different datasets, the performance indicators of EProGNN are almost the best among all baseline models. Even under some specific scenarios, the performance of EProGNN is extraordinary. For example, in the Cora dataset, when the disturbance rate is 25%, the correct rate of the GCN model has dropped to , but the correct rate of EProGNN can still maintain a high correct rate of . In this case, EProGNN is still more accurate than the original model ProGNN. The stability of EProGNN is not only reflected in the high perturbation rate, but also shows excellent performance indicators under the low perturbation rate. For example, in the Pubmed dataset, when the perturbation rate is maintained at , the rate of decrease in the correct rate of ProGNN has reached , but the rate of change in the correct rate of EProGNN is only . Under the same circumstances, the correct decline rates of the GCN and GAT models are and , respectively.

By observing the correct rate table, it can be concluded that in some datasets such as Cora and Citeseer, the rate of decrease in the correct rate of some models is very alarming. Although their model architectures are excellent, such as GCN, GCN-SVD, and GraphSAGE. Because GCN-SVD is specially designed for pointing perturbations, the performance will naturally be greatly reduced for the unspecified attacks used in the experiments in this section. Excellent baseline models such as GraphSAGE under similar circumstances, although their own models have very good quality, but in this specific environment with increasing perturbation rate, their performance is not as good as EProGNN. For example, in the pubmed dataset, under the condition of increasing perturbation rate, the average decrease in the correct rate of EProGNN is only . Under the same circumstances, the GCN-Jaccard model reached . The reason for this is that EProGNN uses evolutionary evolution to perform multiple rounds of preprocessing on perturbed graph structure paradigms of different perturbation levels, and can well restore the original canonical graph structure model in complex undifferentiated adversarial noise. Therefore, the EProGNN model under the blessing of the evolutionary algorithm uses a preprocessing learning strategy to defend against adversarial perturbations on irregular graph edge sets, and then realizes multiple rounds of schema updates. The model can effectively remove adversarial edges with different perturbation rates through low-rank and sparse constraints, and then exclude normal edges. It is precisely because of the above reasons that EProGNN can perform better than ProGNN and ProGNN-fs, no matter at a low or high perturbation rate. EProGNN has confirmed through a series of experimental data that the model can fully use evolutionary algorithms and feature smoothing and is reliable and stable in removing large-scale random confrontation disturbance edges.

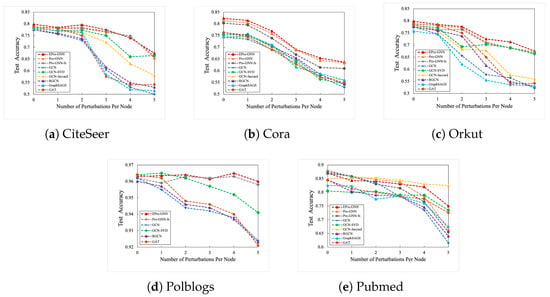

5.2.2. Against with Targeted Adversarial Perturbation

In this section, this paper used a network perturbation method to verify the performance of EProGNN and its various baseline models from the perspective of multiple datasets. The core idea of Nettack aims to only modify the graph during prediction [48], that is, to let the experimental benchmark model parameters be trained only on the training data. The perturbation occurs after the model is trained or during the experimental verification test phase. Since the experimental benchmark model has been fixed, perturbation cannot affect various parameters or structures of the canonical graph structure model. In the experiments in this section, this paper sets the target perturbation number of each graph structure node in detail, ranging from 0 to 5. In the part of the test set, the principle followed in this paper is that when the degree of the graph node of the normative graph structure exceeds 15, it is defined as the target test node. The correct rate of each benchmark model in the node classification experiment in this link is shown in Figure 2. It can be clearly seen from the above figure that with the increase of the number of disturbances, EProGNN has a high accuracy rate and excellent stability. Whether in the Pubmed dataset or in other datasets such as Cora, the EProGNN model proposed in this paper is basically ahead of other excellent baseline representative models. For example, in the Polbolgs dataset, when the number of perturbed target nodes is 5, the performance of EProGNN is higher than that of the GCN-SVD model, reaching an astonishing . In this case, the performance of EProGNN was even ahead of the original ProGNN model. In addition, the correct rate of EProGNN in this mode is higher than that of GAT, GCN, and other models. The demonstration of the experimental line chart fully proves that the model proposed in this paper is successful against targeted adversarial attacks.

Figure 2.

Correctness indicators of different baseline models under nettack perturbation mode.

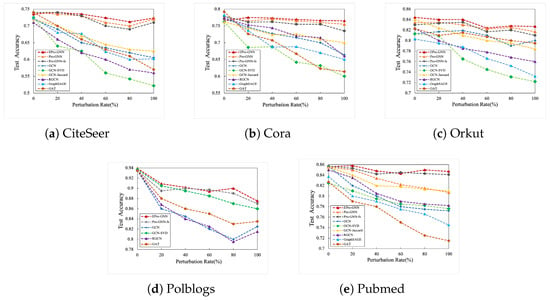

5.2.3. Against with Randomization Adversarial Perturbation

In this section, this paper set the step size to , and conducted experiments from to of the random perturbation noise ratio. In this section, the five most representative datasets and multiple baseline models are still set up for accuracy analysis and comparison. All the experimental data results have been shown in Figure 3. From the various experimental data and graphs in the figure, it can be clearly seen that EProGNN has shown excellent resistance to randomized adversarial perturbations under multiple datasets and basically all of them are higher than other baseline models. For example, in the Polblogs dataset, when the disturbance rate is as high as , the EProGNN model can still maintain a correct rate. In contrast, the correct rate of the classic baseline model GAT is reduced to , and the GCN model supported by the SVD framework is also reduced to . Through the analysis of the experimental results combining three different perturbation modes, it can be said with certainty that EProGNN can fully cope with different complex perturbation modes. Under a variety of perturbation modes, the EProGNN model showed extremely high stability and even surpassed the original model ProGNN for a time. In practical applications, the model is also very practical. The reason is that when faced with different patterns of perturbations, EProGNN can perfectly integrate the evolutionary algorithm and the ProGNN model to resist perturbations.

Figure 3.

Correctness indicators of different baseline models under random perturbation mode.

5.3. Effectiveness Analysis of Graph Structure Learning

This model is based on the adversary adding poisoned edges instead of removing normal edges in a clean canonical graph. It is worth noting that the model tends to use evolutionary algorithms combined with traditional methods to learn and strengthen clean canonical graph structures, so as to mitigate the impact of perturbation edges in graphs affected by poisoned edge sets. Therefore, while conducting the above three adversarial experiments, this paper also examined the influence of the weight ratio of adversarial edges and regular edges. Through the analysis of Citeseer and Orkut datasets, this paper finds that the weight of the adversarial edge in the EProGNN model proposed in this paper is much smaller than the edge set of the canonical graph structure during the entire iterative process. In addition, the bilateral weight difference of EProGNN is slightly larger than that of the original model ProGNN. Therefore, this paper can conclude that EProGNN can also successfully suppress the influence of adversarial edges, and then obtain robust and optimal GNN parameters and evolutionary hyperparameters through training.

Through the analysis of the performance in severe perturbation mode, the core idea solved by this model aims to weaken the edge set of the canonical graph structure perturbation by brute force. Specifically, when removing the edge set of the canonical perturbation graph structure, the adjacency matrix of this model will be all zeros. Which means change all the elements in the row and column of the adjacency matrix to 0, but this operation needs to be completed on the original matrix. In this model, the zero-sum matrix is normalized into a unit regular matrix through a specific function, and the purpose is to facilitate edge set prediction. The goal of the edge set prediction module aims to predict whether there is an edge between two nodes of the model. For any of the five datasets, there are node attributes. The positive samples are stored at the edge and endpoints of these datasets. When the prediction task occurs, this model will generate some negative samples, that is, sample some node pairs without edges as negative sample edges, so that the number of positive and negative samples is balanced. Through the experimental data results, it can be observed that when the graph structure is severely impacted, EProGNN can still obtain considerable data by weakening the graph structure. Therefore, EProGNN can also learn rich graph structure information even when the regular graph is seriously impacted randomly or with a target.

5.4. Ablation Experiment

To verify the necessity of the mutation operator and feature smoothing mechanism proposed in EProGNN, ablation experiments were conducted on the Cora and Citeseer datasets. The complete EProGNN model was compared with the following four variants:

- EProGNN w/o RW: The variant removing the Random Walk Mutation.

- EProGNN w/o BT: The variant removing the Betweenness Mutation.

- EProGNN w/o SB: The variant removing the Stochastic Block Mutation.

- EProGNN w/o FS: The variant removing the Feature Smoothing module.

Detailed experimental results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Table showing the results of the ablation study of EProGNN on the Cora and Citeseer datasets. The results shown in bold are the best experimental results.

As shown in Table 3, the complete EProGNN model consistently achieves the best performance compared to all variant models. Specifically, it achieves the following:

- Impact of Mutations: Removing any of the mutation operators from the complete model (e.g., not using RW, not using BT, or not using SB) leads to a decrease in performance. This indicates that the different mutation strategies complement each other in exploring the graph structure space and preventing the population from converging prematurely to local optima.

- Impact of feature smoothing: EProGNN’s performance degrades without feature smoothing, indicating that feature smoothing is crucial for filtering high-frequency noise in the feature matrix, especially when the graph structure is perturbed.

In summary, each component plays a unique and indispensable role in enhancing the robustness of EProGNN.

6. Conclusions

The graph neural network series models are extremely vulnerable to cyber perturbations, which can significantly negatively affect the effectiveness of the models. In order to be able to effectively defend against compound types and high complexity adversarial network model perturbations, this paper proposes a new network adversarial perturbation defense method EProGNN. While learning the canonical graph structure paradigm model with high precision and high efficiency and refining GNN training parameters, the model can also effectively analyze and read evolutionary hyperparameters. A large number of extensive experimental data prove that the model proposed in this paper is excellent in resisting perturbations and high robustness, and is obviously better than all other baseline models and original models. Experimental results show that EProGNN achieved an average accuracy improvement of 1.48% compared to the strongest baseline model under high-intensity perturbations (e.g., 25% perturbation rate), validating the effectiveness of the evolutionary strategy in graph structure optimization.

In future work, this paper will further explore more working experiments in the scope of graph structure learning by combining evolutionary algorithms. This paper will explore more graph attribute characteristics to further improve the stability, efficiency and robustness of the graph structure under the given circumstances based on the evolutionary algorithm. Future work of this paper will not only be limited to the GNN series of models, but will also deepen the scope of work to more topology structures and attribute models of node features. In addition, this paper will conduct more detailed research and exploration on the analysis of evolutionary parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and Z.L. (Zhaowei Liu); methodology, Z.L. (Zhifei Lu); software, Z.L. (Zhaowei Liu); validation, J.C., D.C. and S.W.; formal analysis, A.J.; investigation, R.G.; resources, Z.L. (Zhaowei Liu); data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. (Zhifei Lu), R.G. and Z.L. (Zhaowei Liu); writing—review and editing, A.J.; visualization, D.C.; supervision, S.W.; project administration, A.J.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project was financed by Yantai Smart City Innovation Lab.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Scarselli, F.; Gori, M.; Tsoi, A.C.; Hagenbuchner, M.; Monfardini, G. The graph neural network model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008, 20, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, H. A deep graph neural network-based mechanism for social recommendations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 2776–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; King, I. Towards fair financial services for all: A temporal GNN approach for individual fairness on transaction networks. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 2331–2341. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.M.; Huang, K.; Zitnik, M. Graph representation learning in biomedicine. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.04883. [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga, M.; Ren, H.; Bosselut, A.; Liang, P.; Leskovec, J. QA-GNN: Reasoning with language models and knowledge graphs for question answering. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.06378. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, K.; Chang, K.W.; Sun, Y. Gpt-gnn: Generative pre-training of graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, CA, USA, 23–27 August 2020; pp. 1857–1867. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Rajkumar, R. Point-gnn: Graph neural network for 3d object detection in a point cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1711–1719. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Tang, Y.; Wu, E. Vision gnn: An image is worth graph of nodes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 8291–8303. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, T.; Yu, M. DAG-GNN: DAG structure learning with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 7154–7163. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Gong, M.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, J. Neural gaussian similarity modeling for differential graph structure learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, British Columbia, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 11919–11926. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Ruan, X.; Fan, X.; Gong, M.; Zhang, H. HGRL-S: Towards Heterogeneous Graph Representation Learning with Optimized Structures. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2025, 9, 2359–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, S.; Hamilton, W.; Duvenaud, D.K.; Urtasun, R.; Zemel, R. Efficient graph generation with graph recurrent attention networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32–42. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/file/d0921d442ee91b896ad95059d13df618-Paper.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Errica, F.; Podda, M.; Bacciu, D.; Micheli, A. A fair comparison of graph neural networks for graph classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.09893. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z.; Yu, L.; Yuan, L.; Wu, Z.; Niu, Q.; Ma, F. Sub-gmn: The subgraph matching network model. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.00186. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Piao, J.; Quan, Y.; Chang, J.; Jin, D.; He, X.; et al. A survey of graph neural networks for recommender systems: Challenges, methods, and directions. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst. 2023, 1, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xiao, J.; Jiao, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, Y. Affinity attention graph neural network for weakly supervised semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 8082–8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Ji, H.; Liu, B. Deep learning on graphs for natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 2651–2653. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; Li, R. EGNN: Graph structure learning based on evolutionary computation helps more in graph neural networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 135, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ma, G.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, W.; Zeng, B.; Zhan, L. Adversarial attack on hierarchical graph pooling neural networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Mou, S.; Wang, X.; Xiao, W.; Ju, Q.; Shi, C.; Xie, X. Graph structure estimation neural networks. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 342–353. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, K.; Lai, K.H.; Hu, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, H. Adversarial graph perturbations for recommendations at scale. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 1854–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Lin, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.Z. Knowledge distillation improves graph structure augmentation for graph neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 11815–11827. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, J.; Xi, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, F.; Kamhoua, C.; Ma, J. Understanding Dropout for Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 1128–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Dou, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Philip, S.Y.; He, L.; Li, B. Adversarial attack and defense on graph data: A survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 7693–7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Zhou, K.; Chen, T.; Guo, K.; Hu, X.; Chang, Y.; Wang, X. CAP: Co-Adversarial Perturbation on Weights and Features for Improving Generalization of Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, M.; Pan, S.; Ye, X.; Fan, D. Simple and efficient heterogeneous graph neural network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 10816–10824. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Li, K.; Jiang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Lv, L.; Ma, Y. Graph Relearn Network: Reducing performance variance and improving prediction accuracy of graph neural networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 301, 112311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X. Graphprompt: Unifying pre-training and downstream tasks for graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Ma, H. Learning a graph neural network with cross modality interaction for image fusion. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 4471–4479. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Tang, J. Graph structure learning for robust graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bacciu, D.; Numeroso, D. Explaining deep graph networks via input perturbation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 10334–10345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, C.; Guo, R.; Yang, X.; Qian, X. A Causality-Aware Graph Convolutional Network Framework for Rigidity Assessment in Parkinsonians. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 43, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Miao, Q.; Liu, R.; Xin, W.; Tang, L.; Zhong, S.; Gao, X. Attention adjacency matrix based graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. Neurocomputing 2021, 440, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ji, S. Self-supervised learning of graph neural networks: A unified review. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 2412–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Bengio, Y.; Tang, J. Gmnn: Graph markov neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 5241–5250. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Sun, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, S.; Ding, S.; Hu, J. GACP: Graph neural networks with ARMA filters and a parallel CNN for hyperspectral image classification. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 1770–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.Y.; Frederking, R. Rwr-gae: Random walk regularization for graph auto encoders. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Chen, T.; Sui, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y. Graph contrastive learning with augmentations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 5812–5823. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Yu, J.X.; Zhang, J. Community detection in social networks: An in-depth benchmarking study with a procedure-oriented framework. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2015, 8, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskovec, J.; Lang, K.J.; Dasgupta, A.; Mahoney, M.W. Statistical properties of community structure in large social and information networks. In Proceedings of the 17th international conference on World Wide Web, Beijing, China, 21–25 April 2008; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, A.; Nigam, K.; Ungar, L.H. Efficient clustering of high-dimensional data sets with application to reference matching. In Proceedings of the Sixth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Boston, MA, USA, 20–23 August 2000; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, P.; Ruiz, M.; Aloise, D. A VNS heuristic for escaping local extrema entrapment in normalized cut clustering. Pattern Recognit. 2012, 45, 4337–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauthammer, M.; Nenadic, G. Term identification in the biomedical literature. J. Biomed. Inform. 2004, 37, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, W.; Xu, H.; Tang, J. Deeprobust: A platform for adversarial attacks and defenses. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 16078–16080. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Zügner, D.; Akbarnejad, A.; Günnemann, S. Adversarial attacks on neural networks for graph data. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 2847–2856. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.